Supporting Family Caregivers in STEMM: A Call to Action (2024)

Chapter: 2 Overview of Unpaid Family Caregiving

2

Overview of Unpaid Family Caregiving

There are only four kinds of people in the world—those that have been caregivers, those that are caregivers, those who will be caregivers, and those who will need caregivers.

– Former First Lady Rosalynn Carter (Carter, 2011)

This chapter provides an overview of national-level data on family caregiving and family caregivers to set the stage for the chapters that follow. It begins by addressing two fundamental questions: who are family caregivers and what is family caregiving? It then turns to examine trends over time in family caregiving, the ways in which the prevalence and demographics of family caregiving have shifted in the past decades, and the impact of family caregiving on caregivers, particularly otherwise employed caregivers. This chapter uses research and data beyond the academic science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) environment to identify trends in how caregiving occurs across workplaces and to provide context for later chapters that examine the specifics of caregiving in academic STEMM. This overview provides necessary background to understand the state of family caregivers to drive action more effectively.

WHAT IS FAMILY CAREGIVING? A TYPOLOGY OF CARE

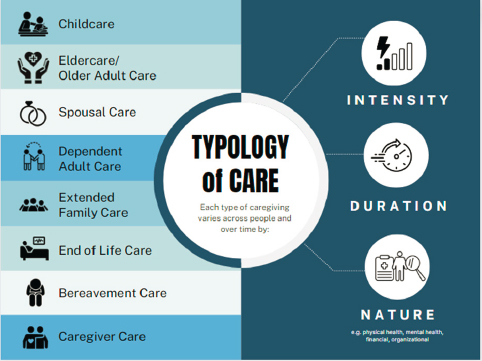

While the term caregiving, encompassing unpaid physical, emotional, organizational, and other support and assistance for loved ones, may be most strongly associated with childcare responsibilities, family caregiving takes many forms. Care for children and young adults is a central aspect of the family caregiving ecosystem, but family caregivers also provide support to aging parents, spouses, and dependent adult children with serious medical conditions, illnesses or disabilities, extended family and kin who may

not be blood relations, those approaching the end of life, or those grieving the loss of a loved one. They also manage their own care needs, such as through the use of sick leave to care for their own illness or injury. Each type of caregiving responsibility requires time, attention, energy, and skills, but the configuration of these responsibilities may vary.

As detailed in Figure 2-1, the committee adopted a broad typology of care to capture the various ways in which people across the U.S. academic STEMM workforce provide care for loved ones. Along with childcare and older adult care, which are more commonly understood, spousal care involves care of a spouse or other long-term partner; dependent adult care covers individuals over 18 with physical, mental, or other needs that require support; extended family care includes people outside the nuclear family unit such as kin and community members in need of care; end-of-life care involves the specific support needed for those with a terminal illness; and bereavement care encompasses tasks for those who have lost a close loved one and need assistance. The committee also included caregiver care in this typology to acknowledge the need for caregivers to engage in efforts to ensure they are personally cared for and supported sufficiently to provide care to others. While all these forms of care are encompassed within family caregiving, specific research and data that the committee cites in this report may only speak to one or two forms of caregiving. Given the variation in data, the committee has worked to specify what types of caregiving the data sources are speaking about and worked to identify information on the full range of caregiving included in Figure 2-1.

Each of these types of family caregiving can vary greatly in terms of intensity, duration, and type of support. For example, caring for an adult is different from caring for a child. Caring for adult dependents or aging family members may last for a shorter duration to help manage the effects of a short-term, acute illness or injury or may last for longer due to ongoing disability or deteriorating physical, mental, or cognitive health (Clancy et al., 2020). Additionally, some forms of adult care, particularly that for aging parents, tend to increase over time, while childcare demands often diminish (Duxbury & Dole, 2015). Studies have reported that adult care often can be more complicated to manage with greater unexpected caregiving needs and situations, which may produce greater stress for the caregiver (Smith, 2004). For caregivers of adults, there is the added consequence that policies and programs are often focused on supporting

childcare responsibilities with less attention to the needs and situations of those caring for older or aging loved ones (Duxbury & Higgins, 2017).

Along with variation across types of caregiving, there is also important variation within each type in terms of intensity, duration, and the nature of care provided both across individuals and over time for an individual caregiver. Those providing care for an adult relative or extended family member may be providing short-term support for physical health needs at one point, then find that as an individual’s health declines, there is need for greater-intensity, longer-term support requiring care not only for physical health but also for organizational and financial needs. Caregiving support may address needs related to chronic or acute illness, mental health challenges, and/or physical disabilities. Some research has also distinguished between primary caregivers, those directly responsible for the care of another individual, and secondary caregivers, those who spend less time in direct care, providing instead occasional or less extensive periods of support (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016).

The amount of time dedicated to caregiving varies depending on several factors, such as the needs of the care recipient; the caregiver’s health, work schedule, and professional demands; and the availability of support services. One examination of family caregivers of adults found they spend 23.7 hours per week providing care on average, and the median number of hours spent was 10 hours per week. About 1 in 3 provides care for 21 hours or more each week and 1 in 5 performs 41 or more hours of family care each week,

equivalent to the time spent on a full-time, paid job (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020).1

The caregiving experience is often complex, and family caregivers particularly of adults and children with a serious illness or disability may need to perform a wide range of complex tasks, from medical care to care coordination to technical support. These tasks go beyond the traditional help with activities of daily living, such as bathing and feeding, that have long been the hallmarks of family caregiving (Administration for Community Living, 2022). Of the caregivers of individuals with a chronic illness, disability, or functional limitation, 6 in 10 help with at least one activity of daily living, and 1 in 5 reports difficulty in providing this level of support (Administration for Community Living, 2022). Over time, family caregivers of adults and children with illnesses or disability have reported increasing responsibilities related to activities of daily living, such as preparing meals, managing finances, providing transportation, and administering medications (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020). Approximately 70 percent of these family caregivers help monitor the severity of their care recipients’ health conditions and nearly two-thirds report that they spend time communicating with health care professionals on behalf of their care recipient (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020).

It is challenging for family caregivers to provide this wide array of tasks. Family caregivers may be expected to provide care without a formal assessment of their own needs or the needs of the person they are caring for, and they may be asked to perform tasks that they are not trained in, that they did not expect to have to do, or that they are not comfortable doing. Even when caregivers identify a gap in skills or comfort, they may not be able to easily access training or assistance (Administration for Community Living, 2022). This is not to say that family caregivers provide substandard or inadequate care; on the contrary, much of the research highlights the many benefits of receiving care from a family member or close relation (Callahan et al., 2009; Kokorelias et al., 2019; Samus et al., 2014). Instead, it highlights that this role is complex and can require many different roles

___________________

1 Estimates of the amount of time caregivers spent on care also vary greatly across surveys based on differing definitions of caregiving and what is counted as caregiving labor. In a 2019 report from the AARP Public Policy Institute, the authors found survey estimates of average weekly hours ranging from around 5 to over 19. The report cited here examined hours of care per week and stated that caregiving included helping with personal needs, household chores, managing finances, arranging for outside help, and visits to check on well-being (Reinhard et al., 2019).

and responsibilities drawing on many different areas of expertise that may or may not overlap with skill sets family caregivers have already developed.

Ultimately, this variation and breadth of family caregiver roles illustrate that family caregiving, while universal in many ways, does not represent one universal experience. For academic institutions that are committed to supporting their STEMM students and workforce with family caregiving responsibilities, a singular view of family caregivers would be simplistic and problematic and could lead to the development of policies and practices that do not support all caregivers. Understanding the breadth of family caregiver roles and responsibilities and providing the flexibility to engage this diversity is a key component to successful policy implementation.

WHO ARE FAMILY CAREGIVERS?

In the United States, family caregivers are a large and diverse group. National estimates vary,2 but they indicate that nearly 20 percent of all Americans were engaged in family caregiving for adults 18 and older in 2020 (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020),3 while 40 percent of U.S. families lived with children under 18 in 2022 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022).4 While family caregiving touches nearly everyone in some way, the responsibilities of caregiving are not evenly distributed across the population. Women, and particularly women of color, in the United States experience higher societal and familial expectations related to caregiving and, consequently, spend more time providing care than do men. Additionally, caregiving responsibilities were relatively more common among middle-aged workers and those workers who are less educated and with lower income (Cynkar & Mendes, 2011).

Evidence that women disproportionately provide family caregiving support relative to men comes from a variety of rigorous studies and surveys. For example, nationally representative data from the American Time

___________________

2 One reason for variation in estimates of family caregivers in the United States is a lack of consistent definitions of caregiving that may included or exclude different activities or differ in the time period over which survey respondents are asked whether they have provided care. In this report, the committee provides what it views as the best current estimates from rigorous reports, but acknowledges estimates are not consistent across the literature.

3 The AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving report considers those who provided unpaid care to a relative or friend 18 or older at any time over the past 12 months as engaged in caregiving.

4 These estimates look at all Americans, not only the population of employed Americans.

Use Survey consistently show women’s deeper engagement than men’s in housework and childcare, although over time, men have increased their involvement in these activities (Bianchi et al., 2006; Sayer, 2005; Wang & Bianchi, 2009). The Health and Retirement Study, another nationally representative sample, reported that gendered patterns in time spent on caregiving continue as people age and extend beyond caring for children (Lee & Tang, 2015). At the same time, even when women do not have caregiving responsibilities, research has found that people may make assumptions that women will become mothers, regardless of their stated intent, and thus will need to take on this responsibility (Thébaud & Taylor, 2021). And even in the paid workplace, women also frequently take on caregiving-type labor, such as mentoring or providing emotional support to colleagues and filling in when others are sick or need to step away due to outside responsibilities (Misra et al., 2021; Moore, 2017; O’Meara, 2016; Writer & Watson, 2019).

While research has shown an increasing move toward greater sharing of childcare responsibilities by men, a similar move in the direction of gender parity has not been observed in older adult care, including care for a woman’s husband’s parents (Grigoryeva, 2017). Women are more likely than men to be the sole caregiver or provide the majority of care for an adult family member and to provide a greater intensity of care than men (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020). Data from the Health and Retirement Study show that women are more likely to provide care for parents and for grandchildren than are men (Lee & Tang, 2015). Daughters are more likely to provide care for older parents than are sons, with sons providing even less care when they have sisters (and therefore daughters providing more care when they have brothers) (Grigoryeva, 2017). Increasingly as well, many women are finding themselves providing what has been termed sandwich care, or care for both young children and adult dependents/aging relatives or kin (Pierret, 2006; Suh, 2016).

Compared with the extent of literature on gender disparities, the literature on racial disparities—and particularly examinations of disparities based on intersecting marginalized identities—is limited.5 While the body of evidence is less robust, the existing data suggest that racial disparities also exist among who is most likely to be providing caregiving, particularly among

___________________

5 The limitations of the current literature on caregiving and race/ethnicity additionally do not allow the committee to tease out further differences within groups based on other intersecting identities, such as immigrant status, socioeconomic status, and sexuality.

those caring for adults. For instance, a recent study found that Black and Hispanic women, on average, perform higher levels of intensity of adult care compared with White caregivers, spending nearly 30 hours more per month than their White counterparts on adult care (Cohen et al., 2019). Estimates on time spent on care by race/ethnicity vary, however. Another study found that Black caregivers spent an additional 13 hours a week on care-related tasks compared with White caregivers (McCann et al., 2000). And a recent report noted that Black caregivers spend around 10 hours more per week and Hispanic caregivers around 5 hours more per week on caregiving than White caregivers (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020). These disparities have also been found to hold in academic STEMM as well. For example, one survey carried out at a research-intensive public institution in the Northeast, which looked at the relationship between working hours and care work outside of the university for all faculty, found that faculty of color spend more time than White faculty on older adult and long-term care (Misra et al., 2012). Black caregivers are also more likely to provide informal care beyond immediate family members to others, such as friends or church members (Cohen et al., 2019; McCann et al., 2000). Historic distrust in caregiving institutions and medical institutions due to histories and continuing experiences of racism and discrimination may contribute to greater reliance on informal care among marginalized groups (Dilworth-Anderson et al., 2020).

Relatedly, Asian American and immigrant caregivers often encounter different cultural expectations for care than do many White Americans. Expectations of filial obligation to care for older adults and aging relatives are particularly strong among many Asian caregivers and influence decisions about providing care personally versus seeking the support of paid caregivers (Guo et al., 2019; Moon et al., 2020). There are also stronger expectations of grandparents providing care to grandchildren, which not only has been shown to have positive effects on mental health but also influences the caregiving burden of many Asian grandparents (Xu et al., 2017). In this way, expectations of providing unpaid caregiving can look different from presumed norms of White caregivers.

Research on caregiving demands among American Indian and Alaska Native populations has especially been lacking; however, one recent survey of 225 participants found that 40 percent of respondents had provided unpaid care over the course of at least 1 month. Respondents provided care for children and adult relatives as well as friends and other loved ones. While the authors noted the role of strong cultural ideologies of community

responsibility played a role in the prevalence of informal caregiving, they also hypothesized that this view of caregiving as a duty and not a burden may provide a buffer against caregiving stress and help to explain the high degree of satisfaction in providing caregiving assistance among respondents (Strachan & Buchwald, 2023). More research, however, is needed on the experiences of both giving and receiving care among American Indian and Alaska Natives.

Overall, research demonstrates that, although there is no one type of person who is a family caregiver, caregiving falls disproportionately to women. Women of color may also face particular challenges given intersecting biases of gender and race/ethnicity, though more work is needed to tease out intersectional differences. Along with variation by race/ethnicity and gender, within the academic STEMM community, caregivers are present at all levels. For instance, caregivers represent a significant portion of the STEMM student and trainee population. More than 1 in 5 undergraduate students are parents (Gault et al., 2020). Whether engaged in the paid labor force, earning a degree, or both, more and more individuals over time are balancing the challenges of caregiving with the challenges of employment in academia and education.

RISING NATIONAL TRENDS IN FAMILY CAREGIVING NEEDS

Over the last several decades in the United States, significant changes have occurred in demographic characteristics of the population, the composition of the professional workforce, and in societal norms and patterns that have far-reaching implications for family caregiving.

Increase in Need for Care

Significant shifts have occurred in the past several decades that have increased the U.S. population in need of care. The U.S. population has aged, particularly between 2010 and 2020, when the country experienced the largest increase in the population 65 and older since the late 1800s (Caplan & Rabe, 2023). According to the Administration for Community Living, the number of Americans aged 65 and older increased 18-fold, from 3.1 million in 1900 to 55.7 million as of 2021, and today’s Americans are living nearly 30 years longer than their 1900 counterparts (Administration for Community Living, 2022). As a result, more of the U.S. population is likely to need care from a family member, friend, or direct care worker

than in previous periods (Administration for Community Living, 2022). Moreover, during the last two decades, the United States waged its longest war, and due to enhanced medical care on or near the battlefield, many veterans survived with life-altering injuries that continue to require long-term or lifetime care, often provided by family members (Bilmes, 2021). Even more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic may further affect societal needs for caregiving related to long COVID and other forms of morbidity (Boyd et al., 2022; Isasi et al., 2021).

Regarding childcare, however, births in the United States have decreased. In 2022, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that there were 63 million parents with children under the age of 18 living in their home, a 5 percent decrease from 2010 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022). Despite this shift, which has happened at the same time as increases in workforce participation among women, the amount of time that parents spent providing active care to their children has risen over several decades (Bianchi et al., 2006; Sayer et al., 2004). This is especially true for highly educated parents, such as many in the academic STEMM workforce. Some research has found that these parents spend more time providing active care to children than those with less education (England & Srivastava, 2013). In addition, nearly 3 million grandparents are primary caregivers to millions of children who cannot remain with their parents (Administration for Community Living, 2022).

The increase, notably in the 1970s, of women, particularly college-educated, White women, entering the paid labor force in record numbers and remaining employed after the birth of their children is also a significant cultural and social factor that explains in part the increased need for caregiving support. This shift in employment dramatically altered women’s past roles as housewives, mothers, and daughters who were available to provide full-time care for children and adult family members (Donnelly et al., 2016; Goldin, 2023).

Increase in People Providing Unpaid Care

A significant increase in the number of people who provide unpaid family care has been occurring for quite some time (Kossek, 2006). For example, in 2020, an estimated 53 million adults provided unpaid care to either an adult or a child with special needs, up from 43.5 million in 2015. Thus, more than 1 in 5 Americans are now caregivers for adults or for children with special needs (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020). In fact, “since the 1990’s (when statistical tracking began), the United States

(US) has seen growth in the number of people engaged in family caregiving, the number of weekly hours they provide assistance, the difficulty of their caregiving tasks, and their labor force participation rate” (Lerner, 2022).

While the greater need for caregiving has played a substantial role in the increase in the number of people engaged in unpaid family caregiving, this increase in unpaid caregiving is likely due to several additional, large-scale cultural and economic factors. These include the increased financial costs of professional caregiving,6 increased recognition of what counts as caregiving, the increase in women’s participation in the paid labor force, and an insufficient labor force of paid professional caregivers.

While the overall population needing care has grown, the rising cost of long-term care has made it difficult for many families to afford professional care (Abelson & Rau, 2023; Administration for Community Living, 2022). Already, caregiving is incredibly costly, as many family caregivers incur large out-of-pocket expenses in the thousands of dollars or more to care for adult loved ones (AARP, 2021) and hundreds of thousands of dollars to raise a child to age 18 (LaPonsie, 2022; Lino et al., 2017). Adding the cost of paid care services can be too great an additional burden and many families instead have chosen to take on the responsibility of care themselves (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020).

We may also attribute some of the noted rise of caregiving in the United States to increases in the number of self-reported family caregivers in national surveys. In recent years, as greater attention has been paid to family caregiving responsibilities in the media, more people recognize that the everyday support they provide to their family and other loved ones is a form of caregiving, which may result in a higher proportion of people self-identifying as caregivers on national surveys (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020).

Within that same period that has seen an increase in family caregivers, there has also been a simultaneous increase in the paid labor force participation of family caregivers. This is in part due to the shift in the 1970s when more women entered the paid labor force and thus were faced with combining their paid work with unpaid caregiving responsibilities. Today, a

___________________

6 Recent estimates suggest the cost of paid childcare increased 86 percent between 1995 and 2016, and the cost for long-term care for older adults has also increased as the demand for such care has risen with an aging population (Hayes & Kurtovic, 2020; Swenson & Simms, 2021).

very large share of individuals combine their family caregiving responsibilities with paid work. According to Current Population Survey data, nearly 73 percent of all mothers with children under age 18 and 93 percent of all fathers with children under age 18 were in the labor force in 2022 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023b). More than 80 percent of employed mothers work full-time, and full-time work is nearly universal among employed fathers (95.6 percent) (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023b). Additionally, according to a 2010–2011 U.S. Gallup Survey of a random sample of nearly 250,000 individuals ages 18 and above, 1 in 6 respondents who reported working a full- or part-time job also reported assisting with care for an older or disabled family member, relative, or friend (Cynkar & Mendes, 2011).

Finally, the increase in reliance on unpaid caregivers, especially of those who also work, is, in part, due to the scarcity of professional caregivers available to hire. For decades, scholars have detailed the gap between the supply of paid caregivers and the demand for their work (Super, 2002). Recent estimates project a national shortage in caregivers for older adults of 151,000 by 2030 and 355,000 by 2040 (Global Coalition on Aging & Home Instead, 2021). Not only does this lack of professional caregivers result in the caregiving needs falling to unpaid family caregivers, but it can also lead to the unpaid caregivers spending significant time working to find and hire a professional caregiver, which on its own is a form of providing care. In 2020, about one-third (31 percent) of family caregivers for adults or children with special needs experienced at least some difficulty in coordinating care for their loved one, up from 23 percent in 2015 (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020). While this report focuses on the experiences and needs of unpaid family caregivers, it should also be acknowledged that greater support for paid caregivers is important to the success and support of unpaid caregivers.

Increase in Intensity of Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The intensity of care, defined as both the number of hours in a week required to provide care to a care recipient and the difficulty and complexity in the types of tasks caregivers are required to perform, was particularly notable during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic played a significant role in shaping caregiving intensity, as many care centers closed and family caregivers worked to balance the unique challenges of work during a

pandemic with caregiving needs. Studies examining the experiences of both those caring for children and those caring for adults reported increases in care intensity and burden of care during the pandemic (Archer et al., 2021; Cohen et al., 2021). This was particularly acute for women who traditionally and still today often take on the greatest share of family caregiving labor (Cohen et al., 2021). The pandemic not only contributed to increased intensity of care, but it also increased risk of health-related socioeconomic vulnerabilities for caregivers more than for non-caregivers. The pandemic contributed to worsened financial strain, food insecurity, housing insecurity, interpersonal violence, and transportation difficulties for family caregivers (Boyd et al., 2022).

THE IMPACT OF CAREGIVING AND THE CHALLENGES FACED BY CAREGIVERS

Caregiving across the life course is an important and rewarding role for many and has a deeply personal effect on all who need care. Research is clear that caregiving experiences in early childhood are formative for later well-being, and that care quality has a substantial influence on the experience of aging and/or disability particularly by allowing adults needing care to remain in their homes (Fernandez et al., 2016; Worthman et al., 2010). Parenting; spending time caring for aging parents; and connecting to other family, friends, and communities through providing care all give individuals opportunities for relationship building and nurturing (Mackenzie & Greenwood, 2012). Nevertheless, research is also clear that family caregivers often experience physical, emotional, and financial challenges, which indicates a growing need for support services for them.

As family caregiving can in many instances involve high intensity and complexity, it has associated effects on the well-being of family caregivers (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020). AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving (2020) define “intensity of care” by the number of hours of care given as well as the number of activities of daily living a caregiver assists with (e.g., bathing, toileting, feeding). Approximately 40 percent of unpaid family caregivers for adults or children with special needs are in high-intensity caregiving situations, with 16 percent experiencing a medium intensity and 43 percent experiencing a low intensity. High-intensity caregiving is often associated with worse self-reported health outcomes and higher rates of financial strain (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated demands for unpaid care across the life course, individuals with caregiving responsibilities experienced negative mental health outcomes at much higher rates than non-caregivers. Approximately 70 percent of those parenting children or caring for adults reported adverse mental health symptoms, including anxiety or depression (Czeisler et al., 2021). The consequences of caring for adults in this challenging environment was more significant than that of caring for children, and those who reported the highest rates of negative mental health effects were those who were caring for both children and adults. This last group was almost four times more likely than non-caregivers to experience adverse mental health symptoms (Czeisler et al., 2021). Research has also shown that particularly for women, a lack of support for caregiving and the increased demands during the pandemic resulted in higher levels of psychological distress, understood as experiences of anxiety, worry, depression, and hopelessness (Prados & Zamarro, 2020; Ruppanner et al., 2019; Zamarro & Prados, 2021). As workplaces deal with the mental health impacts of COVID-19, it is important that institutions attend specifically to caregivers and understand that the negative effects of caregiving on mental health preceded the crisis.

Caregiving also affects labor force participation among caregivers, particularly for mothers of young children (Cortés & Pan, 2020), which has financial consequences. According to surveys conducted by Gallup-Healthways and Pfizer-ReACT, Americans who identify as caregivers working at least 15 hours a week miss an average of 6.6 workdays per year. This absenteeism results in 126 million missed workdays a year, which would be even higher if part-time workers were included in these calculations (Witters, 2011). As a result of hours spent on care, many caregivers leave paid jobs, cut back on work hours, miss days at work, or limit funds put into their retirement savings (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020; Weller & Tolson, 2019; Witters, 2011). These reduced or lost earnings can slow their wage growth over time and ultimately limit their retirement income from Social Security and employer-based retirement plans (Weller & Tolson, 2019). Table 2-1 provides an overview of the causal evidence on the economic impacts of caregiving for employed family caregivers.

Overall, the evidence suggests mothers in particular face greater challenges following the birth of a child, especially a first child, as well as clear penalties in job opportunities and earnings and reductions in productivity. Fathers, instead, do not face these same penalties and challenges to the same

TABLE 2-1 Causal Effects of Caregiving on Key Economic Outcomes

| Outcome | General Findings: Caregivers of Children | General Findings: Caregivers of Adults |

|---|---|---|

| Labor Force Participation | Mothers, but not fathers, are more likely to exit the labor force after becoming parents (Cortés & Pan, 2020). The strongest impact is after the birth of a first child (Doren, 2019). | Most of the research is descriptive, finding largely modest or null, but negative, effects (Aughinbaugh & Woods, 2021; Fahle & McGarry, 2018; Reinhard et al., 2023; Wilcox & Sahni, 2022). The few causal studies present mixed findings with either modest negative effects (Jacobs et al., 2016; Maestas et al., 2023) or null effects (Stern, 1995; Van Houtven et al., 2013). Research also suggests caregivers are more likely to retire, but the effects are small (Jacobs et al., 2016; Miller, 2009; Van Houtven et al., 2013). |

| Hours of Paid Work | There is limited causal research on the impact of children on paid hours worked among STEMM professionals in the U.S. context. Evidence from other fields, such as law and business, as well as international evidence finds a decline in women’s hours worked following the birth of a first child (Azmat & Ferrer, 2017; Bertrand et al., 2010; Kleven et al., 2019) and an increase in part-time work (Boelmann et al., 2021; Schmitt & Auspurg, 2022). | Caregivers of adults are more likely to work fewer paid hours than non-caregivers, but the effect size is small (He & McHenry, 2015; Johnson & Lo Sasso, 2000; Van Houtven et al., 2013). |

| Job/Career Opportunity | Lab, audit, and quasi-experimental studies find that mothers are discriminated against in hiring (Correll et al., 2007). | There is limited research on the causal connection between how caregiving of adults affects job and career opportunities, and thus no finding about the effect can be identified. |

| Outcome | General Findings: Caregivers of Children | General Findings: Caregivers of Adults |

|---|---|---|

| Earnings/Wage Penalties | Women, particularly married women, younger women, and women of color, face a motherhood wage penalty of around 4–7% (Anderson et al., 2002; Budig & England, 2001; Kahn et al., 2014). Other research has found that these effects may grow over time, with estimates of long-term wage penalties in the United States at 31% (Kleven et al., 2019). | Studies have provided mixed conclusions, ranging from no effect for men or women (Van Houtven et al., 2013) to no effect for men but a small effect for women (Butrica & Karamcheva, 2015) to large effects for women (Nizalova, 2012; Skira, 2015), particularly younger women (Maestas et al., 2023). |

| Productivity | Without adequate support, mothers in particular experience penalties to their productivity given competing demands (Morgan et al., 2021). COVID-19 and the subsequent challenges with childcare coupled with ineffective organizational support also resulted in productivity gaps between men and women (Kossek, Dumas, et al., 2021; Stall et al., 2023). | Only one study was identified on the association between productivity and caregiving for adults. This study found a substantial decrease in work productivity due to caregiving demands (Mazanec et al., 2011). |

NOTE: This table draws substantially from the research paper “The Economic Impacts of Family Caregiving for Women in Academic STEMM: Driving an Evidence-Based Policy Response,” by Courtney Van Houtven, Ph.D., and Ngoc Dao, Ph.D., that was commissioned for this study. The full paper is available at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/27416. More on the methodology for inclusion of studies in this paper can be found in Appendix C.

degree. The findings for caregivers of older adults are less conclusive and generally present mixed, null, or small effects on the outcomes examined.

Importantly, however, all these effects are not simply the inevitable outcome of a need to provide care for another person. Instead, many of them are the result of a lack of support for caregiving and could be mitigated with greater support. For example, access to affordable childcare is one key intervention that has been shown to have an immense effect on not only the likelihood of being employed but also the hours spent in paid

employment among American women (Ruppanner et al., 2019). Greater support from partners also makes a key difference in employment outcomes for mothers. Research conducted during the pandemic found that employed mothers with less support from their partners reported a greater reduction in their working hours than those with more support (Prados & Zamarro, 2020).

For caregivers who are enrolled as students, there are also financial challenges stemming from a lack of support for caregiving. Most of the existing data on the challenges of student caregivers focus on student parents. These students are significantly less likely to graduate within 6 years: while nearly 60 percent of all students graduate in 6 years, under 40 percent of student parents graduate in that time frame (Institute for Women’s Policy Research & Aspen Institute, 2019). Students with children also have higher rates of educational debt than students without children, as they often face greater financial responsibilities as well as insecurity and are more likely to be enrolled in for-profit institutions (Institute for Women’s Policy Research & Aspen Institute, 2019). All of this contributes to greater financial burdens associated with both their caregiver status and educational status for student parents.

Challenges faced by family caregivers are exacerbated in the U.S. context compared with other developed countries because of the lack of strong public policy supporting unpaid caregivers, leaving more of the burden of addressing the needs of caregiver-workers on individual employers (AARP, 2021; Body, 2020). Of the high-income countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the United States is the only one that lacks national statutory paid leave for parents and other unpaid caregivers (Gromada & Richardson, 2021). Combined with its poor investment in paid childcare, this distinction places the childcare system in the United States 40th overall out of the 41 high-income OECD countries (Gromada & Richardson, 2021). In health care, the United States has the highest levels of spending and the worst health outcomes of any wealthy nation (Gunja et al., 2022). The absence of a national health care system that guarantees care to all is particularly notable. Care for those who are aging or disabled is similarly fragmented and inadequate.

These challenges were poignantly displayed among interview participants. Interviewees noted expending tremendous intellectual, financial, and physical resources in the attempt to manage the competing demands of their careers and caregiving responsibilities. They described distilling their priorities and triaging their workloads; devising new time-efficiency

strategies; learning to fit in more flexible work and caregiving commitments around inflexible ones; communicating proactively with advisors, teachers, managers, and academic leadership; and developing a host of creative personal and professional arrangements to attempt to fulfill their competing academic and professional responsibilities. Such strategies were often a source of pride, and some success.

Caregivers with access to substantial private resources, such as individuals in academic leadership roles or those in dual-career physician couples, recounted using every resource, unpaid and paid, at their disposal to make their professional situation tenable in the context of substantial caregiving commitments. As one respondent stated:

“The only way I was able to make it work was my husband was a stay-at-home dad at that point…. He’d get up in the middle of the night with changing my parents’ bedclothes if there were accidents and things like that…. The only way we were able to make that work was him being at home. And I think that’s a real problem because not everybody has that flexibility. I probably would’ve had to put my parents in a nursing home if it wasn’t for that [or] I would’ve had to quit my job … the combination of financial resources and partner resources helped me to care for kids and parents at the same time…. I wouldn’t have survived without that.”

Those who had fewer private resources, particularly students and other early-career scholars and those from underrepresented backgrounds, more often recounted being driven out of their professions or scientific careers entirely. Others left academia for jobs in industry. One interviewee discussed her own thoughts on leaving the academy:

“Not everybody comes from a privileged background. So those expectations that you have to work for these high-risk, high-reward projects for many years and put the rest of your life on hold, they are nonsustainable for most of us, right? And especially if you have a young family. I mean, you can decide to sacrifice your time and yourself, but you cannot do that for your family.”

Still, most interviewees—even those occupying positions of relative personal or professional privilege—experienced the conflict between their

careers and their caregiving responsibilities as irreconcilable. As one interviewee noted:

“In a perfect world, I could balance it all. I could just be really efficient at work, get through my calls, get through my notes, then come home and have dedicated time to spend caring for my mom. But the time just doesn’t allow for it. There’s often times where I’m staying late trying to catch up … it just squeezes how much care I can do…. You can’t be great at either [career or caregiving] at the same time.”

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FROM CHAPTER 2

Demands for caregiving have risen simultaneously with demands on the time of family caregivers in paid labor, resulting in greater binds and constraints for today’s family caregivers. Gender and racial disparities in caregiving roles and responsibilities mean that, in general, these challenges are experienced disproportionately by women and may be especially acute for women of color.

- Family caregiving takes many forms, including care for children and young adults (those with and without special needs), aging relatives, spouses, dependent adult children, extended family and kin who may not be blood relations, those approaching the end of life, and/or those grieving the loss of a loved one. Each of these types of caregiving can vary in terms of intensity, duration, and type of care provided both across individuals and over time for an individual caregiver.

- Family caregivers in the United States are diverse, with caregivers coming from all backgrounds and demographics; however, these demands are not evenly distributed across the population. Women are more likely than men to care for children, older parents, and grandchildren, and women of color are more likely than White men or women to provide care for extended family, such as siblings, parents, and care for kin who may not be blood relatives.

- Since the 1990s, the number of people engaged in caregiving, weekly time spent providing care, and the labor force participation rate of caregivers have all increased. These increases are likely due to several factors, including large-scale cultural and economic

- shifts; growing aging, chronically ill, and disabled populations; increased self-reporting of caregiving roles in national surveys; increased costs for professional caregivers; and an insufficient supply of paid professional caregivers.

- Caregiving across the life course is an important and rewarding role for many, and its effect is significant—research is clear that caregiving experiences in early childhood are formative for later well-being and that care quality has a substantial effect on the experience of aging and/or disability. Nevertheless, research also demonstrates that family caregivers often experience physical, emotional, and financial challenges, which were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as by insufficient national- and institutional-level support.

- Individuals across academic STEMM face challenges due to a lack of support for caregiving. Certain populations, particularly students and trainees, who are earlier in their career, less established, and in more precarious positions, may face particular challenges.

This page intentionally left blank.