State of Knowledge Regarding Transmission, Spread, and Management of Chronic Wasting Disease in U.S. Captive and Free-Ranging Cervid Populations (2025)

Chapter: 2 CWD Description, Pathogenesis, and Infectivity

CHRONIC WASTING DISEASE

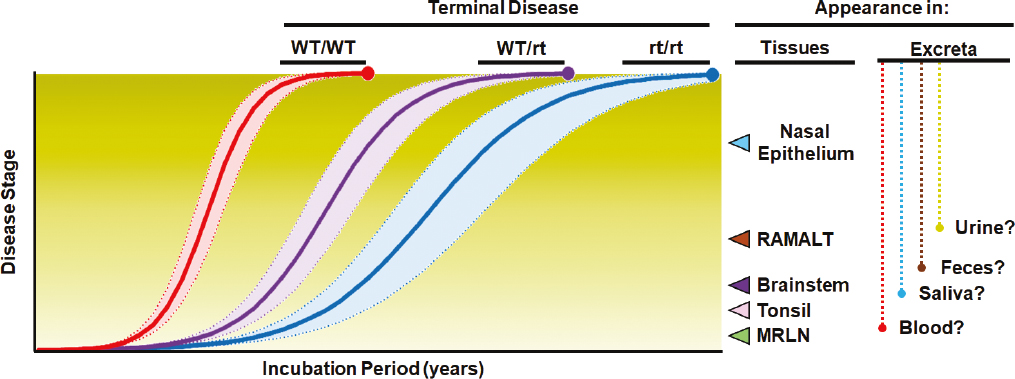

CWD is not caused by bacteria, virus, or other more familiar infectious agents but instead is caused by misfolded versions of prions that are normally found in the bodies of cervids (see Box 1.1). Like other prion disorders, CWD is the result of infection with a misfolded variant of the host’s normal cellular prion protein, PrPC (see Box 2.1 for a list of acronyms related to prion proteins). The gene that encodes the normal prion protein in cervids—PRNP—shares common structural features with both bovine (i.e., cattle) and ovine (i.e., sheep) prion protein genes (see Box 2.2 for a technical description of the structure of the prion protein and Table 2.1 for a comparison of the “classical” forms of prion diseases of hoofed stock in the United States). Although the PRNP gene shows sequence similarities across cervid species, there are several allelic variations (i.e., nucleotide changes in the DNA) that encode prion proteins with different amino acid sequences (Robinson et al., 2012). A subset of these variations is linked to slower CWD progression (Figure 2.1 and Table 2.2) and extended incubation times, although comparatively less is known about disease pathogenesis in cervids with these genotypes than those with more common genotypes. Of the genotypes evaluated to date, none confer complete resistance to prion infection.1 Because susceptibility to CWD is considered polygenic, other genes likely have a role in both susceptibility and pathogenesis. This concept is discussed in Chapter 6.

Prion diseases are the result of an infection with one or more different prion strains, defined as conformational variants of infectious prions, which may be transmitted between hosts or arise spontaneously in an individual host. Multiple CWD strains have been identified (Otero et al., 2023). Although a spontaneous form of CWD is suspected in some Scandinavian cervids (Pirisinu et al., 2018; Ågren et al., 2021), spontaneously occurring CWD cases have not been described in North America to date. Currently, clinical patterns of disease resulting from the varied CWD strains are difficult to differentiate from one another, and disease pathogenesis largely parallels what is seen with sheep scrapie. Both the extent and levels of prion accumulation in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral tissues have been well studied and may allow discrimination between various CWD strains and spontaneously arising forms of the disease.

CWD occurs naturally in some deer (Cervidae) species, in both captive and free-ranging populations. This includes mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus hemionus), black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), North American elk (Cervus canadensis), and moose (Alces alces). The infectious form of CWD also has been observed in both captive2 and experimentally inoculated (Mitchell et al., 2012) reindeer (Rangifer tarandus; sometimes called caribou in North America), and in captive red deer (Cervus elaphus), sika deer (Cervus nippon; Sohn et al., 2020), and sika/red deer hybrids (Prion 2016 Animal

___________________

1 Note: this report uses the term “disease resistance” to imply reduced susceptibility to disease in a manner that is common usage in agricultural settings and related scientific literature.

2 See https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/usaha-annual-cervid-health-report-2018.pdf (accessed August 20, 2024).

Prion Disease Workshop Abstracts, 2016). Two phenotypes of the disease (i.e., the way the disease presents itself in the host) have been described—distinguished by whether abnormal prion protein (PrPCWD) accumulates in the lymphoid tissues of infected cervids (Tranulis et al., 2021; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023). The lymphoid-associated CWD form (“phenotype”) is most common and, to date, is the only phenotype described in North America (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023). Ample experimental and epidemiological data support the notion that the phenotype of CWD occurring in North America behaves as an infectious disease in susceptible cervid hosts.

This chapter provides an overview of CWD in North America, beginning with a brief history of its emergence and geographical expansion across the continent. It examines the various prion strains and their role in infection. The chapter also explores key factors such as infectious dose for disease transmission, incubation period,

TABLE 2.1 Comparison of the “Classical” Forms of Prion Diseases of Hoofed Stock in the United States

| Category | Prion Disease (“classical” form) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect | Epidemiological Feature | Chronic Wasting Disease | Scrapie | Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy |

| Agent | More than one prion strain identified | yes | yes | no |

| Host | Main host species | deer, elk (Family Cervidae) | sheep, goats (Family Bovidae) | cattle (Family Bovidae) |

| Genetic influence on host susceptibility | moderate | strong | none | |

| Naturally transmitted to unrelated species | not reported | not reported | yes | |

| Can be experimentally transmitted to unrelated species via oral route | yes | yes | yes | |

| Can be transmitted to humans | not reported | not reported | yes | |

| Transmission and geographic spread | Transmitted via ingesting infectious tissues | yes (experimental) | yes | yes |

| Infectivity in tissues beyond central nervous system | yes | yes | no | |

| Transmitted via infectious excretions and secretions | yes | yes | no | |

| Main driver(s) of transmission within herd | exposure to infectious animals and environments | exposure to infectious animals and environments | feed contaminated with infectious cattle byproducts | |

| Main (known) source(s) of introduction into a herd | infectious animals | infectious animals | contaminated feed | |

| Other potential source(s) of infection | suspected | none reported | none reported | |

| Persistence of infectivity in the environment | yes (>2 years) | yes (>15 years) | not reported | |

| Control | Examples of successful control (scale) | limited (local) | yes (national) | yes (national) |

| Current (ca. 2020s) distribution in the United States | widespread | limited/absent | absent | |

| Historical distribution in the United States (ca. 1950-2000) | extent uncertain | widespread | rare | |

| Outbreaks in free-ranging hosts | yes | not reported | not reported | |

| Effective vaccines or medical treatments available | no | no | no | |

| Genetic selection as a control tool | some potential | yes | not needed | |

| Likely extent of control feasible in the United States (given current knowledge and tools) | manageable in captive herds, less so in the wild and as cases and spatial extent increase | eradicable | establishment prevented | |

SOURCE: Committee generated.

SOURCE: Figure adapted from Haley and Richt (2017).

and clinical presentation of infected cervids. In addition, the chapter details the pathogenesis of CWD and prion distribution in various host tissues.

BRIEF HISTORY OF CWD IN NORTH AMERICA

As described in Box 1.1, a clinical syndrome consistent with what has come to be known as CWD was documented in the United States in 1967 in Colorado and recognized as a spongiform encephalopathy in 1978 (Williams and Young, 1980, 1992). The cause of the emergence and initial spread of CWD within North America remains obscure, poorly understood, and untraceable to a single point of emergence with any reliability (Williams and Young, 1992; Williams and Miller, 2003; Miller and Wolfe, 2023). Epidemiological models of CWD that incorporate diagnosed cases of the disease in free-ranging and captive cervids indicate that the disease was likely present in some areas of Colorado and Wyoming at least two decades prior to its initial classification as a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) (Miller et al., 2000; Williams and Miller, 2002). Similarly, other disease transmission models suggest CWD may have been present in free-ranging white-tailed deer in Wisconsin at least 30 years before its discovery there in 2001 (Wasserberg et al., 2009), somewhat complicating the general supposition that the disease originated from a singular occurrence in western cervids.

Across its geographical and host range, CWD occurs as several prion strains (discussed in the next section) and two distinct phenotypes (lymph-associated and non-lymph-associated [reviewed by Miller and Wolfe, 2023]). This strain and phenotype diversity, along with the known pathogenesis of other TSEs, lend plausibility to three primary hypotheses of CWD’s origins:

- An event, or events, of spontaneous prion protein misfolding in individual cervids may have led to the development of an infectious prion disease that then spread to other cervid populations and species (Williams and Young, 1980, 1992; Kahn et al., 2004; Tranulis et al., 2021; Williams, 2005; Williams and Miller, 2003).

TABLE 2.2 PRNP Variations Found in North American Cervids

| Species | PRNP Variant | Frequency in Farmed +/− Free-ranging Cervids | Influence On | Notes | Example References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection Odds Ratio | Disease Progression | |||||

| White-tailed deer | 96G | ~70% | Reference baseline | Reference standard | Wildtype (WT) genotype; using extended nomenclature: 95Q/96G/116A/226Q | |

| 96S | ~25%, with higher frequency in e.g., Texas | <0.50 (heterozygous) <0.10 (homozygous) |

Slows | Using extended nomenclature: 95Q/96S/116A/226Q | Johnson et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2006a; O’Rourke et al., 2004; Kelly et al., 2008; Wilson et al., 2009; Keane et al., 2008b; Brandt et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2012; Haley et al., 2019; Seabury et al., 2020 | |

| 95H | <2% | <0.30 (heterozygous) Homozygous unknown |

Slows | Using extended nomenclature: 95H/96G/116A/226Q | Johnson et al., 2011a; Seabury et al., 2020; Haley et al., 2019 | |

| 116G | <3%, primarily in Canadian herds | <0.50 (heterozygous) <0.01 (homozygous) |

Slows | Using extended nomenclature: 95Q/96G/116G/226Q | Haley et al., 2019; Hannaoui et al., 2021 | |

| 226K | <4%, primarily in U.S. herds | <0.60 (heterozygous) Homozygous unknown |

Similar to 96G, or only modestly slows | Using extended nomenclature: 95Q/96G/116A/226K | Seabury et al., 2020; Haley et al., 2019 | |

| Mule deer | 225S | ~85% | Reference baseline | Reference baseline | Amino acid sequence identical to the 96G variant in white-tailed deer | |

| 225F | ~5% | <0.1 | Slows | PrPCWD present but may not stain with monoclonal antibody F99/97.6.1; homozygotes rare in natural populations even where CWD is prevalent | Jewell et al., 2005; Wolfe, K.A. Fox, and Miller, 2014; LaCava et al., 2021 | |

| 20G | ~9% | Similar to 225S | Similar to 225S | Polymorphism in signal sequence, not present in mature protein | Wilson et al., 2009; Jewell et al., 2005 | |

| Elk | 132M | ~75% | Reference baseline | Reference baseline | Amino acid sequence identical to the 96G variant in white-tailed deer except for a Q226E substitution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 132L | ~25% | <0.70 (heterozygous) <0.40 (homozygous) |

Slows | 132L homozygous elk-different PrPCWD profile on WB | O’Rourke et al., 1999; Perucchini et al., 2008; Hamir et al., 2006a; O’Rourke et al., 2007; Haley et al., 2018; Haley et al., 2019 | |

| Moose | 209I | ~55% | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| 209M | ~45% | Unknown | Unknown | Amino acid sequence identical to the 96G variant in white-tailed deer | Huson and Happ, 2006 | |

| Reindeer/Caribou | GSV | ~40% | Reference baseline | Reference baseline | Using extended nomenclature: 129G/138S/169V/225S; amino acid sequence identical to the 96G variant in white-tailed deer | Mitchell et al., 2012; Arifin et al., 2020; Güere et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2016 |

| 138N | ~50% | Variable dependent on zygosity | Variable dependent on zygosity | Using extended nomenclature: 129G (or S)/138N/169V (or M)/225S |

Mitchell et al., 2012; Arifin et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2016 | |

| SSM | <2% | Considered less susceptible | Unknown | Using extended nomenclature: 129S/138S/169M/225S | Mitchell et al., 2012; Arifin et al., 2020; Güere et al., 2020 | |

| 225Y | Unknown; reported only in European reindeer | 0.2 as a heterozygote | Unknown | Using extended nomenclature: 129G/138S/169V/225Y | Güere et al., 2020 |

NOTE: G = glycine; S = serine; H = histidine; K = lysine, F = phenylalanine; M = methionine; L = leucine; I = isoleucine; N = asparagine; V = valine; Y = tyrosine; WB = Western Blot.

SOURCE: Committee generated.

- CWD may have adapted over time in cervids in one or more locations after direct or environmental exposure to a strain of scrapie, a TSE affecting domestic sheep (Williams and Young, 1992; Williams and Miller, 2003). This theory is often favored given that CWD and scrapie are unique among the TSEs in their ability to transmit horizontally via animal-to-animal contact as well as via environmental contamination (Tranulis et al., 2021). Both early (e.g., Colorado/Wyoming) and recent (e.g., Norway) CWD outbreaks have overlapped with domestic sheep travel routes and pastures. Additionally, CWD can be transmitted to domestic sheep via intracerebral inoculation, and white-tailed deer have been successfully inoculated with classical scrapie proximately of U.S. origin via oronasal (mouth and nose) exposure (Greenlee et al., 2023).

- CWD may have developed from an unidentified strain of TSE in an unknown free-ranging or captive mammal species before spreading to other cervid species (Miller and Wolfe, 2023; Williams, 2005).

The ultimate source (or sources) and emergence date(s) of CWD will likely remain unknown given the absence of definitive data.

It would be inaccurate to view the arc of CWD geographical expansion and increase in prevalence as a linear progression of the disease through time and across landscapes. Even prior to its formal documentation, cervids exhibiting clinical signs consistent with possible CWD had been observed in multiple cervid research facilities and zoos in both the United States and Canada (Miller and Wolfe, 2023). As recognition of the disease increased in the late 1990s and early 2000s, so did efforts to implement surveillance programs throughout North America. Early surveillance programs were not well coordinated, often too broad in geographic scope for the limited sample sizes; and inconsistently applied to reliably document the emergence, presence, or spread of CWD in free-ranging or captive herds within a particular area (Miller and Fischer, 2016). CWD surveillance will be discussed further in Chapter 4. Unfortunately, misunderstanding about the limitations of early surveillance data by media outlets and organizations disseminating information about CWD3 has given rise to an impression among the public and even wildlife management professionals that each discovery of CWD was viewed as evidence that the disease was rapidly spreading (Miller and Fischer, 2016; Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024). However, it is likely that many “new” incidences of CWD were simply the first documented cases discovered because of increased surveillance and do not likely represent the first occurrence of CWD on the landscape. Subsequent sampling from some supposed “new” foci typically revealed many more cases, indicating that the disease had been in the local herd or area for many years or even decades (Miller and Wolfe, 2023; Miller and Fischer, 2016).

CWD’s true expansion at local and global scales has been facilitated by both anthropogenic (i.e., originating because of human activities) and natural factors, exacerbated by the long preclinical phase of CWD infection (cervids appear healthy throughout most of the disease course). For example, preclinical (healthy-looking) CWD-infected captive elk from South Dakota were transported to captive cervid facilities in Saskatchewan and then to South Korea, resulting in the first known cases of CWD in elk in Canada and in South Korea (Kahn et al., 2004; Sohn et al., 2002). Extensive and often undocumented anthropogenic movement of captive cervids before and after the disease’s discovery likely has facilitated two-way, horizontal transmission between affected captive and wild populations, as has the escape or release of exposed captive cervids (Miller and Wolfe, 2023; Miller and Fischer, 2016). However, not all distal CWD outbreaks can be attributed to anthropogenic spread of infected cervids or cervid parts. The 2016 discovery of CWD in Norwegian reindeer has no documented or even plausible link to an anthropogenic spillover event from North America, and recent identification of novel strain types in Europe suggest that these strains of CWD may have arisen independently or in parallel to North American variants (Nonno et al., 2020; Tranulis et al., 2021). Though unconfirmed as definitive modes of disease transmission, the movement of CWD-infected cervid parts by hunters; commercial sale of goods containing infected cervid products; and transportation of hay and animal feed contaminated by infectious CWD prions from soil, feces, and cervid parts may have played some role in the disease’s increase in prevalence and geographic footprint (Miller and Fischer, 2016).

Regardless of the initial transmission modality, once established in free-ranging cervids, CWD spreads to new areas and populations adjacent to the initial disease foci and increases in prevalence within infected cervid herds. The natural ability to transmit via shedding of infectious prions into soil and other elements of the environment

___________________

3 See https://e360.yale.edu/features/chronic-wasting-disease-deer (accessed August 20, 2024).

(Miller et al., 2004), including by direct contact between infected and susceptible cervids (Henderson et al., 2015a; Mathiason et al., 2006; Denkers et al., 2024), facilitated spread of CWD within and between cervid herds and species across large areas of North America and, independently, parts of northern Europe. Natural migration, social interactions, mating, and other cervid behaviors (e.g., grooming, maternal interactions, congregation around food and water sources) may have played a significant role in the past and current expansion of CWD in free-ranging cervids in affected populations (Miller and Wolfe, 2023; Miller and Fischer, 2016). Box 2.3 provides a brief history of CWD in Canada.

PRION STRAINS

Like viruses and other pathogens, prions can exist as different strains—traditionally defined as an isolate that produces a unique pattern of neuropathology when passaged under controlled experimental conditions (Fraser and Dickinson, 1967; Fraser and Dickinson, 1968). The concept of strains, as applied to prions, was first suggested in 1961 based on the different clinical manifestations experienced by scrapie-infected sheep (Pattison and Millson, 1961) and later demonstrated through transmission experiments in laboratory rodents (Bruce, 1993). While most pathogen strains are associated with changes in their nucleic acid genomes, prions exist in a range of different conformations (i.e., “shapes” of individual prion strains can be different); it is these variations that drive the differences in observed neuropathology (Bessen and Marsh, 1992; Hill et al., 1997; Safar et al., 2015). Unfortunately, practical laboratory discrimination of prion strains is difficult given that current techniques for strain typing (such as lesion profile analysis, PrP deposition, and transmission properties) do not allow a detailed analysis of PrPSc structure, resulting in an incomplete understanding of both their molecular characteristics and their importance in disease ecology. The precise mechanisms underlying the generation of prion strains are not

yet clear but are affected by both the amino acid sequence of the host PRNP and the prion conformers present in the infected individuals (Bartz, 2016). Because of the potential for novel and diverse strains to appear in a single host, they may independently result in novel pathology or alter the susceptible host range of the original prion (reviewed in Bartz, 2016). The isolation of two distinct strains of hamster-adapted transmissible mink encephalopathy in outbred hamsters provides evidence that host background likely does not play a role in the generation of strains (Bessen and Marsh, 1992). Strains have been identified in numerous animal species, including classical and atypical scrapie in sheep and goats (Pattison and Millson, 1961; Benestad et al., 2003), classical and atypical bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle (Wells et al., 1987; Casalone et al., 2004), sporadic types and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans (Parchi et al., 1996; Parchi et al., 1997; Parchi et al., 2000; Bruce et al., 1997; Hill et al., 1997), and CWD in cervids (Angers et al., 2010; Otero et al., 2023).

Early transmission studies of CWD isolates into transgenic mice (e.g., “bioassay” using mice genetically modified to replace the mouse prion gene with the prion protein from another species) first suggested a potential for strain variation (Browning et al., 2004; LaFauci et al., 2006). Further bioassays in hosts expressing different PrPC sequences confirmed the existence of multiple CWD strains (Angers et al., 2010; Perrott et al., 2012; Duque Velásquez et al., 2015; Duque Velásquez et al., 2020; Herbst et al., 2017; Hannaoui, Schatzl, and Gilch, 2017; Moore et al., 2020). CWD strains can have different characteristics in experimental hosts, with host range and PRNP sequence variations playing an important role in CWD strain emergence (Duque Velásquez et al., 2015; Duque Velásquez et al., 2020; Hannaoui, Schatzl, and Gilch, 2017; Moore et al., 2020). Complicating the understanding of strain emergence and prevalence is the lack of information in early CWD studies regarding species or genetic makeup of the individuals from which transmitted isolates were prepared. Given the evolutionary potential of CWD strains, specifying the year the sample was collected, as well as additional metadata like the age, sex, species, and location of the animal, is vitally important to enable comparison of data among independent studies.

INFECTIOUS DOSE

Understanding the “minimum infectious dose” of exposure to CWD prions is important for understanding an individual animal’s risk of developing the disease. The minimum infectious dose for some bacterial agents (e.g., Francisella tularensis) may be as low as a single bacterium (Jones et al., 2005), while some viral agents such as norovirus have minimum infectious doses approaching 20 viral particles (Hall, 2012). For many disease agents, determining a minimum infectious dose is done in either natural (e.g., deer) or experimental (e.g., mice) model systems. Given the difficulties of housing and maintaining wild cervids over long periods and given questions regarding the suitability of experimental mouse models for informing the understanding of CWD in natural hosts, determining a minimum dose of CWD prions required for infection of cervids has been challenging. To date, a single study in captive white-tailed deer provides information regarding the minimum infectious dose for CWD via oral inoculation (Denkers et al., 2020; see Box 2.4), although other studies over the past two decades, discussed below, provide additional boundaries on the understanding of infectivity and insights into a correlation between dose and incubation period. A range of factors likely affect minimum infectious dose, including the volume of inoculum and the route of exposure, disease stage of the donor (i.e., the animal from which the infectious prions were collected), amount of infectious prions in the dosing substrate (e.g., brain, blood, or saliva), and other organic or inorganic modifiers (e.g., clay, organic acid), as well as cervid species, age, and genetic background of the target host, including both PRNP genetic makeup and other potential markers of susceptibility, as discussed in Chapter 6 (Natural and Artificial Selection).

Box 2.4 describes an experimentally derived minimum dosage of approximately 300 nanograms (ng) of brain equivalents or 15-25 milliliters (mL) of saliva that successfully infected white-tailed deer, resulting in clinical disease 21-38 months following exposure (e.g., the “incubation period” of the disease). A retrospective review of experimental infections over the past several decades indicates that the doses provided were often significantly higher than this estimated minimum infectious dose. In white-tailed deer and mule deer, for example, oral doses commonly ranged from 5 to 10 grams (g) of brain homogenate (Sigurdson et al., 1999; Fox et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2011b)—equating to perhaps 15-30 million times the predicted minimum infectious dose. Similar dosing protocols were used in other cervid species, including moose (Kreeger et al., 2006), reindeer (Mitchell et al., 2012), and sika deer (Sohn et al., 2020). Interestingly, approximately 5g of CWD-positive brain homogenate administered

via the oral route was sufficient to cause sub-clinical infection (i.e., PrPCWD were replicated in the brains, but there were no clinical signs of disease) in pigs—a species not known to be naturally susceptible to CWD (Moore et al., 2017). Although it is possible that these high doses, compared to more “natural” levels of infectivity, could confound understanding of CWD susceptibility, pathogenesis, and shedding, experimental infections of white-tailed deer with high doses of CWD prions had similar incubation periods to naturally infected deer (Johnson et al., 2006a).

Other prion sources (besides brain) and infection routes have been investigated. For example, when white-tailed deer were intravenously injected with 100-250mL of blood from CWD-positive mule deer, they developed CWD within approximately 2 years (Mathiason et al., 2006). Oral inoculation studies using relatively small volumes (0.1-1.0g) of brain or tonsillar tissue found that incubation periods largely mirrored those of cervids infected through direct intracranial inoculation or larger oral doses (Mathiason et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2012; Wolfe et al., 2012). In contrast, oral inoculation of urine and feces—with volumes ranging from 50-85mL and 50-112g, respectively—failed to induce clinical infection after 18-19 months (within the range of a natural infection), although these animals were later found to be sub-clinically infected (Mathiason et al., 2006, 2009; Haley et al., 2009a). Environmental exposure, although difficult to quantify, commonly resulted in infection within 1-2 years (Mathiason et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2016). Relatively little is known about the true minimum dose for natural routes of exposure. However, estimates derived from experimental studies may suffice as benchmarks for additional in vitro studies to better understand transmissibility. Applicability of future findings would benefit from emphasis on natural routes and sources of infection (i.e., oral exposure, environmental exposure using inocula from infected animals/tissues), as well as use of common and well-characterized assays and reference standards.

Across model systems, both incubation period and attack rates (i.e., the proportion of animals infected when exposed to a certain dose) may be influenced by inoculation dose, including cross-species transmission studies (Mammadova, Cassmann, and Greenlee, 2020; Baier et al., 2003; McLean and Bostock, 2000; Collins et al., 2005; Fryer and McLean, 2011). Although this may also be true in cervids (Denkers et al., 2020; Wolfe et al., 2012), there is currently little data to confirm this observation in all cervid species (Hamir et al., 2006a; Moore et al., 2018). Similarly, disease progression, and in some cases prion tissue distribution, in various animal models may be affected by different dosing protocols (Race, Oldstone, and Chesebro, 2000; Herzog et al., 2004).

As differences in tissue distribution can occur between the various cervid species (possibly dictated by strain or genetics), the timing and intensity of shedding in urine and feces may possibly be affected (Denkers et al., 2024). Without having a more accurate correlation between natural exposure and experimental doses, understanding these features of CWD pathogenesis in both natural and alternate hosts is problematic (Mathiason et al., 2009; Moore et al., 2016).

INCUBATION PERIOD

The incubation period of CWD (i.e., preclinical stage of disease prior to onset of clinical signs) may differ widely across various PRNP genotypic backgrounds—and likely other genetic sites—within and between cervid species (see Figure 2.1). Initial experimental studies focused on animals with the most common PRNP genotypes in captive and free-ranging animals, including the highly susceptible 96G homozygous genotype (i.e., having two identical versions of the same gene—one from each parent) of white-tailed deer, mule deer, and reindeer, and the 132M/132M genotype of elk (see Table 2.2). Time to onset of clinical disease following oral inoculation in these studies was typically 1.5-2.5 years in white-tailed deer, mule deer, and reindeer (Fox et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2011b; Miller et al., 2012; Mitchell et al., 2012), and up to 2 years in elk (Moore et al., 2018), similar to incubation periods reported for scrapie in sheep (Spickler, 2016). At present, there is no indication that the oral exposure dosage affects incubation period. In white-tailed deer, incubation periods following more unnatural routes of exposure, including intracranial, intravenous, and intraperitoneal inoculation, largely paralleled those of oral exposure (Mathiason et al., 2006; Mathiason et al., 2009).

Recently, attention was given to those PRNP genotypes that, based on past studies, suggest differential susceptibility, including the 96S genotype of white-tailed deer, the 225F genotype of mule deer, the 132L genotype of elk, as well as several alternate genotypes in reindeer (O’Rourke et al., 2004; Jewell et al., 2005; Johnson et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2006a; O’Rourke et al., 2007; Mitchell et al., 2012). In those studies, the onset of clinical signs was delayed compared to more common PRNP genotypes; in some cases, incubation periods approached 5 years or more (Johnson et al., 2011a; Miller et al., 2012). Further studies investigating both susceptibility and incubation periods in white-tailed deer with more rare, heterogenous PRNP backgrounds are currently underway.4

In contrast to experimental inoculations where the timing of exposure is known, the incubation periods arising from natural CWD infections cannot be measured with precision, especially in the wild. However, incubation periods in experimental oral inoculation studies largely matched those estimated from field data in free-ranging animals (e.g., Miller et al., 2008; Edmunds et al., 2016; DeVivo et al., 2017). The youngest detected wild deer and elk with clinical CWD were 16 and 21 months, respectively (Spraker et al., 1997; Williams and Miller, 2002), well within the range of data from experimental inoculations. Available evidence thus suggests the incubation after natural exposure is probably not substantively different from what has been produced experimentally, and consequently what has been learned from experimental studies can inform understanding of natural disease processes. In addition to the demonstrated variation explained by PRNP genotypic background discussed above, it seems plausible that other host, agent, or environmental factors also could affect incubation after natural exposure.

With the discovery of a novel form of CWD in Scandinavia characterized by the absence of lymphoid PrPCWD and all cases involving relatively old animals (Pirisinu et al., 2018; Vikøren et al., 2019; Tranulis et al., 2021), it is evident that the causative strain may also be a factor in CWD incubation period.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical progression and presentation of CWD can differ within and between species (Fox et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2011a; Williams and Young, 1980). Clinical features—most apparent in experimentally infected animals—include changes in behavior and progressive deterioration of body condition (i.e., weight loss) (Williams, 2005). Signs of disease progress over weeks to months following disease onset (Williams, 2005). Cervids showing signs may display changes in how they interact with herd mates or their handlers, and may display fixed stares, repetitive movements, periods of somnolence, and hyperexcitability when approached. Their postures may appear altered, with lowered head and ears and arching of the back, and there may be ataxia (Fox et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2011a; Williams and Miller, 2002). Changes in gastrointestinal microbial composition have been suggested in infected white-tailed deer, although further comparisons of affected and unaffected animals are warranted to better understand whether such changes may serve as disease markers (Didier et al., 2024; Minich et al., 2021).

___________________

4 For example, by the USDA Agricultural Research Service. See https://www.ars.usda.gov/research/project/?accnNo=440677 (accessed November 6, 2024).

Advanced clinical disease may involve bruxism (teeth grinding), polydipsia (excess drinking), polyuria (excess urination), difficulty swallowing, regurgitation of rumen contents, and excess salivation with drooling. As is reported for similar protein misfolding disorders, progression of neurologic disease eventually leads to recumbency, aspiration pneumonia, dehydration, or hypothermia during the winter season, which can ultimately result in the death of the infected animal (Williams and Miller, 2002). Compared to deer, captive elk with CWD can display nervousness and hyperesthesia (increased sensitivity), and are more likely to display gait changes and less commonly polydipsia (Williams, 2005). Although these clinical signs are less apparent in free-ranging animals, the subtle progression of early neurologic disease makes infected deer and elk more likely to be hit by cars (Krumm, Conner, and Miller, 2005), killed by predators (Krumm et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2008; DeVivo et al., 2017), or harvested by hunters (Conner, McCarty, and Miller, 2000; Edmunds et al., 2016; DeVivo et al., 2017) than their uninfected counterparts.

PATHOGENESIS OF DISEASE

Figure 2.1 is a timeline model of the pathogenesis of CWD in cervids with different PRNP genotypes over time, with disease stage (discussed in detail later in this section and in Chapter 4) representing the accumulation of prions in different bodily tissues (Spraker et al., 2023, 2004; Keane et al., 2008a; Fox et al., 2006; Haley and Richt, 2017). The distinguishing pathological characteristics of CWD in deer are similar to those of scrapie-infected sheep and other prion diseases acquired through ingestion of infectious material. In orally infected deer, PrPCWD crosses the intestinal epithelial barrier and can be detected in lymphoid tissues associated with the alimentary tract (e.g., within 1-month post-exposure can be detected in lymphoid tissues associated with the alimentary tract such as the gut-associated lymphoid tissue [GALT]), as well as tonsils and retropharyngeal lymph nodes (RPLN) within 1 month of exposure (Fox et al., 2006; Hoover et al., 2017; Sigurdson et al., 2001; Sigurdson et al., 1999). Within these sites, PrPCWD is found to associate with specific intra- and extracellular target proteins (Sigurdson et al., 2002). This cellular targeting during early phases of the disease suggests that prions cross the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract and are transported to Peyer’s patches (clusters of lymphoid follicles in the intestines) and regional lymph nodes (Sigurdson et al., 2002; Sigurdson et al., 1999). Prions can then enter nerve endings of the enteric nervous system (ENS) and leak into the lymphatic and blood systems spreading to other organs (Heggebø et al., 2003; van Keulen, Bossers, and Zijderveld, 2008).

Prion infection of the ENS spreads through sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves to the CNS (van Keulen, Vromans, and Zijderveld, 2002). An early site of PrPCWD accumulation within deer CNS is the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, suggesting this nerve as the major route for PrPCWD from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain (Sigurdson et al., 2001). A second route of prion migration into the brain is through retrograde transport of prions up the spinal cord (Kaatz et al., 2012; McBride et al., 2001). Although this route is important during invasion of the brain by BSE prions in cattle, it does not appear to be a critical route of CWD prions in deer. This suggests that accumulation of PrPCWD in the thoracic spinal cord of orally infected cervids results from the spread of CWD prions produced within the CNS (Sigurdson et al., 2001).

Multiple organs may be infected via transport by lymph and blood (see Table 2.3 for examples of studies). Several blood cell types from CWD-infected deer have demonstrated significant prion infectivity, suggesting that the blood-borne spread of infection is likely an important component of disease progression (Mathiason et al., 2010).

Although the early lymphoid replication phase is particularly important for CWD prions (Hoover et al., 2017; Sigurdson et al., 2001), exceptions were noted in North American elk as well as Scandinavian moose and red deer, where PrPCWD may accumulate in the brainstem with minimal or no accumulation of PrPCWD in lymphoid tissues (Pirisinu et al., 2018; Race et al., 2007; Spraker et al., 2004; Vikøren et al., 2019). This could be explained by a predominantly neural route of entering the brain, sporadic misfolding of PrPC (i.e., similar to atypical scrapie or BSE), and differences in the route of exposure or in strain. Differences in route of exposure may also affect prion accumulation in different tissues (Haley et al., 2011). Once in the brain, PrPCWD accumulates in the CNS, producing lesions associated with prion diseases, including intraneuronal vacuolation (large vesicles in the cytoplasm of neurons), spongiosis (spongy appearance of the brain), gliosis (inflammation a nonspecific production or enlargement of glial cells following CNS injuries), and formation of amyloid deposits (Williams and Young, 1993).

In addition to lymphoid tissues, CWD prions can be found in a range of tissues outside the brain, including nasal mucosa, salivary glands, urinary bladder, pancreas, kidney, intestine, and reproductive tract of female and male deer (Fox et al., 2006; Haley et al., 2011; Kramm et al., 2017; Nalls et al., 2017; Otero et al., 2019; Sigurdson et al., 2001) and elk (Spraker et al., 2004, 2010, 2023). CWD prions have also been identified in gestational tissues of pregnant deer and elk (Nalls et al., 2017; Selariu et al., 2015). The accumulation of PrPCWD in some of these tissues is associated with shedding of prions through secretions and excretions (Haley et al., 2011). As described for sheep scrapie (Andréoletti et al., 2000) and as noted above, host PRNP genotype can influence CWD pathogenesis in deer, notably affecting PrPCWD deposition in peripheral tissues (Fox et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2011; Hoover et al., 2017; Maddox et al., 2020; Otero et al., 2019).

Because the natural progression of clinical disease may be variable in susceptible species, disease staging provides a subjective but reproducible approach for quantifying the progressive accumulation of PrPCWD in those central and peripheral tissues described above (Spraker et al., 2004; Keane et al., 2008a). Often, the RPLN and obex region of the brainstem—the primary tissues collected for postmortem testing—are the focus of disease staging efforts, though other tissues, including spinal cord, tonsil, and other lymphoid tissues, and non-neural tissues may be considered as well (Spraker et al., 2023). Little is known about the correlation between disease stage and the onset of shedding. To date, a uniform approach to disease staging has not been developed, although there are significant areas of overlap between those scoring systems described. A more comprehensive understanding of the alignment of disease stage and the shedding, as reported for other infectious neurologic diseases like rabies (Vaughn, Gerhardt, and Newell, 1965), will be important in aiding disease management strategies.

PRION DISTRIBUTION IN HOST TISSUES

In some prion diseases like BSE, the presence of misfolded prions may be limited to nervous tissue and a narrow selection of “specified risk materials” such as the eyes, tonsils, and distal intestinal tract (USDA, 2019). CWD prions, however, are distributed across many tissues beyond the CNS and lymph nodes, including a wide range of peripheral tissues—an important consideration when developing, for example, interstate carcass movement regulations (Gassett, 2019). Table 2.3 is a list of tissues in which CWD has been detected in different cervid species. CWD prion detection in tissues is based primarily on immunohistochemical analysis or in vitro amplification methods (see Chapter 4), which provide insufficient information regarding levels of infectious prion present (e.g., titers). However, few tissues have been bioassayed in transgenic mice. Little is known about the distribution of CWD prions in North American moose, primarily due to the relatively few cases identified to date. CWD prions also are shed in urine, feces, and saliva.

TABLE 2.3 Detection of CWD Prions in Tissues and Excreta of CWD-Infected Cervids

| Category | Tissue | White-Tailed Deer | Mule Deer | Elk | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excreta and Bodily Fluids | Blood | Y | Kramm et al., 2019; Mathiason et al., 2006 | ||

| Cerebrospinal Fluid | Y | Y | Nichols et al., 2012; Haley et al., 2013 | ||

| Feces | Yb | Y | Y | Haley et al., 2011; Tamgüney et al., 2009; Tewari et al., 2022; Plummer et al., 2017; Henderson et al., 2017 | |

| Saliva | Y | Henderson et al., 2015a; Haley et al., 2009b | |||

| Semen | Y | Kramm et al., 2019 | |||

| Urine | Yb | Henderson et al., 2015a; Haley et al., 2009b; Plummer et al., 2017 |

a Y designates the presence of CWD prions.

b Indicates variability depending on PRNP genotype of the species (Spraker et al., 2023; Race et al., 2007; Race et al., 2009a; Sigurdson et al., 2001; Balachandran et al., 2010; Otero et al., 2019; Plummer et al., 2017).

c ND designates that samples were tested, but CWD prions were not detected.