State of Knowledge Regarding Transmission, Spread, and Management of Chronic Wasting Disease in U.S. Captive and Free-Ranging Cervid Populations (2025)

Chapter: 5 Epidemiology and Ecology of Chronic Wasting Disease

5

Epidemiology and Ecology of Chronic Wasting Disease

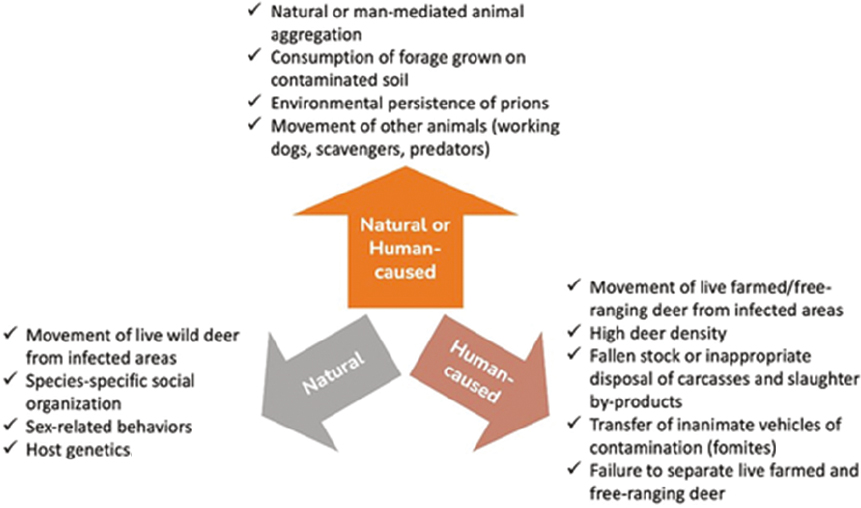

Understanding how chronic wasting disease (CWD) outbreaks progress and how the disease spreads geographically at local and larger spatial scales has informed control strategies, just as diagnostics and surveillance have provided tools for detecting CWD and tracking trends (see Chapter 6 for discussion of surveillance and interventions). The European Food Safety Authority’s (EFSA) report on CWD summarizes decades of U.S. research (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2019; see Figure 5.1). The factors that contribute to CWD spread, both positively and negatively, are complex and not well quantified in the literature. Issues such as climate (e.g., drought, severe winters), migration route interference, human land development, increased predation, and other diseases can affect the geography of CWD.

SOURCE: Mori et al., 2024.

This chapter summarizes knowledge about the patterns and drivers of CWD spread and key features of its epidemiology and ecology. The chapter first discusses patterns of geographic growth and apparent spread at the regional and national scales. Drivers are then discussed, including anthropogenic and natural risk factors. The chapter concludes with a discussion on the impact of CWD on cervid population dynamics.

PATTERNS OF EPIDEMIC GROWTH AND APPARENT GEOGRAPHIC SPREAD

The epidemic behavior of CWD resembles that of other infectious diseases of domestic and wild animals, although outbreaks unfold more slowly than seen in some viral and bacterial diseases (Miller et al., 2000). The number of cases tends to increase over time, and the geographic area where cases occur also expands where infected host populations are not constrained by fencing. Understanding how localized CWD epidemics grow in prevalence and expand naturally across landscapes can aid in the design and assessment of surveillance strategies and inform the interpretation of spatiotemporal trends at a larger geographic scale. Knowledge about expected patterns also can be used to assess prospects for natural stabilization and the effectiveness of control efforts (more fully covered in Chapter 6).

Epidemic Growth

Epidemic growth has been documented in multiple locations where CWD has become established in captivity or in the wild (see Box 5.1; Miller et al., 2000; Miller et al., 2020; Miller and Williams, 2003; Manjerovic et al., 2014; LaCava et al., 2021; Smolko et al., 2021). As reflected in Box 5.1 and the foregoing references, empirical data from multiple locations show sustained increases over time in either disease incidence or apparent infection prevalence—that is, the proportion of infected individuals in a sample and a proxy for incidence in CWD epidemics (Miller and Wolfe, 2021). In individual captive populations, CWD outbreaks can show relatively steep increases in incidence over several years (Williams et al., 2002; Miller and Williams, 2003; Miller, Hobbs, and Tavener, 2006), attributable in part to the smaller and more dense (i.e., concentrated by confinement) host populations but

perhaps also to more (or unnatural) opportunities for prion exposure in confined settings (Williams et al., 2002; Miller, Hobbs, and Tavener, 2006; Schultze et al., 2023; Mori et al., 2024).

Based on available data, outbreaks among free-ranging herds appear to grow more slowly at the host population/geographic scales upon which surveillance tends to be based. Monitoring of CWD foci in multiple states and provinces over time has yielded data on epidemic growth (e.g., Box 5.1), and on natural spatial expansion (e.g., Figure 5.2) where the disease has become established in free-ranging populations (Miller et al., 2000; Manjerovic et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2020; LaCava et al., 2021; Smolko et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2023). As shown in some of the individual curves from outbreaks observed in free-ranging deer (Odocoileus spp.) populations in Figure 5.1.1, apparent prevalence in uncontrolled CWD epidemics increases slowly and perhaps imperceptibly over the first decade or more but eventually reaches an inflection where growth—approximating exponential—becomes more readily measured from field data. As epidemic growth continues, apparent prevalence can exceed 25% (additional examples discussed in later sections). Despite asynchronous starts, CWD outbreaks in free-ranging deer have followed remarkably similar trajectories in multiple locations across the United States.

Geographic Expansion in Free-Ranging Populations

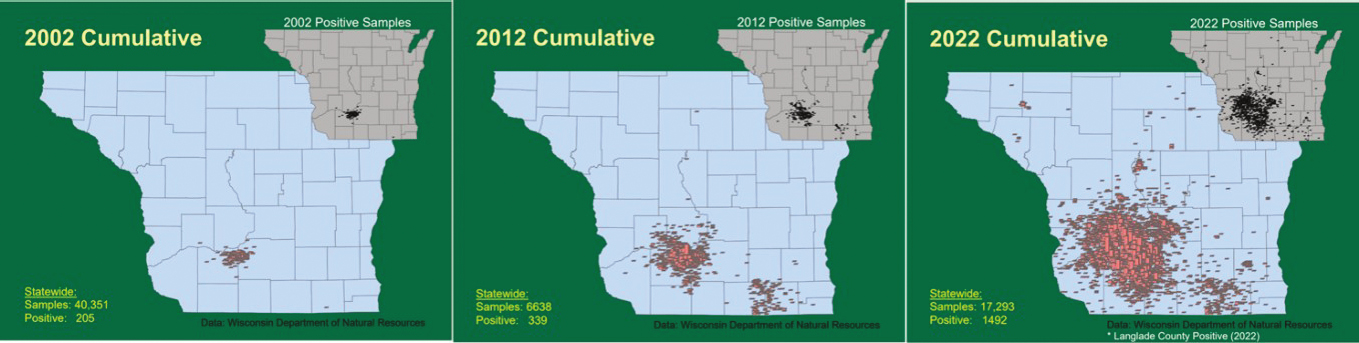

As the apparent prevalence of CWD increases locally in free-ranging populations, natural movements of infected animals and social overlap with neighboring animal groups leads to geographic expansion of the area affected by CWD (Figure 5.2). With epidemic growth, spatial expansion of an outbreak area tends to occur over several decades (e.g., Jennelle et al., 2009; Wasserberg et al., 2009) and can be accelerated by human activities, as discussed in later sections of this chapter. The rate of natural spread across large geographic areas may be relatively slow; for example, Jennelle and others (2009) estimated an average rate of CWD spread of approximately 0.7 miles (1.13 kilometers) per year in the vicinity of the western core of south-central Wisconsin’s largest focus. Seasonal migration or larger host home ranges could drive these rates somewhat higher (Conner and Miller, 2004; Jennelle et al., 2009). Because the state of Wisconsin conducted extensive, systematic statewide surveillance within a few years after first detecting CWD in 2001 (Joly et al., 2009), the observed changes in disease distribution over the ensuing decades are more likely to be real than an artifact of sampling effort.

SOURCE: U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) National Wildlife Health Center, see https://p.widencdn.net/nfe9ku/cwddistribution (accessed May 17, 2024).

Elsewhere, increasing or expanding surveillance on the perimeter of newly detected foci, a common response to CWD detections (Thompson et al., 2023), may have left the impression that CWD expanded over a shorter period, whereas the changing pattern simply reflected the expanded surveillance effort having detected outbreaks in adjacent areas that were already well underway.

Interpreting Geographic Spread at a National Scale

The geographic expansion across 35 states in the United States has occurred over at least six decades, if not longer (Miller et al., 2000; Jennelle et al., 2009; Wasserberg et al., 2009; Miller and Fischer, 2016). Inferring a precise timeline for the arrival of CWD in previously unrecognized areas—for example, based on when CWD was first detected—is problematic (Box 5.1; Miller et al., 2000; Jennelle et al., 2009; Wasserberg et al., 2009; Miller and Fischer, 2016; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2018; Thompson et al., 2023). Impediments to accurately describing the timeline of CWD spread in the United States include

- uncertainty about the epidemiological source(s) of local CWD emergences and incomplete data on movements and distribution of infected animals or other potential infective sources (e.g., scrapie in sheep and goats) over time (see Chapter 2);

- the virtual absence of organized surveillance in either wild or captive cervids prior to the mid-1990s and inconsistency in surveillance efforts (where practiced) since (Evans, Schuler, and Walter, 2014; Thompson et al., 2023; Mori et al., 2024; Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024); and

- the practical difficulties in detecting newly established disease foci at the true onset of an outbreak, especially in the free-ranging populations (see Chapter 4).

Limitations in historical and contemporary surveillance, in outbreak investigations, in reporting, and in records on human-assisted translocation all can contribute to uncertainty surrounding precisely when and how CWD has come to occur in a location where it has been detected (e.g., Williams and Young, 1992; Miller et al., 2000; Williams et al., 2002; Joly et al., 2009; Wasserberg et al., 2009; Evans, Schuler, and Walter, 2014; Miller and Fischer, 2016; Uehlinger et al., 2016; Schultze et al., 2023; Thompson et al., 2023; Mori et al., 2024; Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024). As a result, the precise timing and origin(s) of CWD emergence in the United States and changes in its distribution over time remain uncertain (Williams and Young, 1980; Williams and Young, 1992; Williams et al., 2002; Wasserberg et al., 2009; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2017; Miller and Wolfe, 2023). Most non-adjacent free-ranging CWD foci and some outbreaks in captive facilities have no documented times or points of origin or connections to one another (Miller and Fischer, 2016; Schultze et al., 2023; Mori et al., 2024). Although the first recorded encounters and experience with this disease were in Colorado and Wyoming (Williams and Young, 1980; Williams and Young, 1992), available data

do not preclude the possibility of CWD originating or emerging independently elsewhere in the United States, either before (Wasserberg et al., 2009) or since, as perhaps happened in Europe (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023).

Published records indicate that CWD-infected and exposed animals were moved via trade or commerce involving U.S. zoos and private collectors by the early 1970s, including at least one international instance (Williams and Young, 1992; Williams and Miller, 2002; Dubé et al., 2006). By the late 1990s, commercial movements of elk had been linked to CWD outbreaks on farms in one Canadian province and five western states (Miller and Williams, 2001; Kahn et al., 2004; Argue et al., 2007). Canadian investigations concluded that CWD likely was imported from the United States in the late 1980s (USAHA, 2001; Kahn et al., 2004; Bollinger et al., 2004), indicating the disease had been spreading undetected in commercial trade for a decade or more. Unpublished records suggest a larger footprint of exposed and infected animal movement was likely (USAHA, 1998, 2001). Although some outbreaks occurred in commercial facilities with both elk and white-tailed deer (USAHA, 998), subsequent efforts to investigate and contain CWD in commercial cervid facilities were largely concentrated in the western United States and focused on elk facilities (USAHA, 1998, 2001). The detection of CWD east of the Mississippi River in free-ranging and captive white-tailed deer reported in early 2002 expanded awareness across the United States thereafter (Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024).

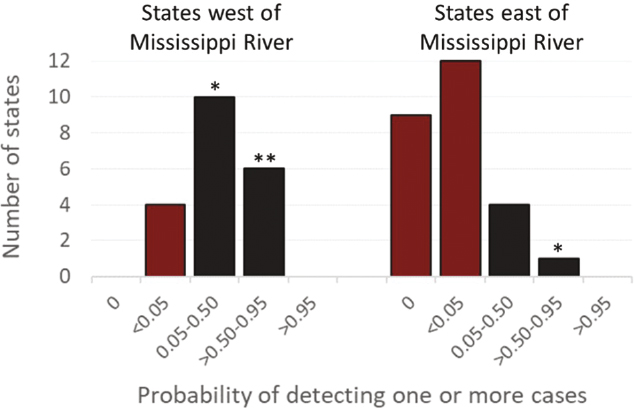

In addition to spread of CWD among captive cervid facilities in the late 1990s, undetected CWD likely was expanding in local free-ranging populations where the disease had been introduced (or had independently emerged). However, organized surveillance for CWD in free-ranging populations did not occur outside of Wyoming and Colorado before the mid-1990s and was minimal in most states located east of the Mississippi River before autumn 2002 (Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024). West of the Mississippi River, the majority of CWD surveillance conducted during 1997-2001 was in states with known free-ranging foci or perceived risk due to detection in cervid facilities or proximity to states where CWD was detected in the free-ranging populations (Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024). Multiple newly detected CWD cases and locations during 1997-2002 stimulated marked expansion of surveillance efforts nationwide beginning in autumn 2002 (Figure 5.3; Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024). Since then, surveillance efforts waxed and waned depending on the availability of federal funds to support sampling and testing, as well as reaction to more new infections (Evans, Schuler, and Walter, 2014; Thompson et al., 2023).

SOURCE: Data from Table S1 by Ruder, Fischer, and Miller (2024).

CWD was documented in one or more commercial cervid facilities in 14 additional states and in the free-ranging populations in one or more locations in 22 additional states during Winter 2003-Spring 2024 (at the time of writing this report). In some cases, the epidemiological connections among infected sites are clear (e.g., USAHA, 1998; Sohn et al., 2002; Argue et al., 2007; Mori et al., 2024). In others, they are not. The greater number of CWD detections since 2002 is sometimes portrayed as evidence of rapid expansion (USGS National Wildlife Health Center, 2024). However, CWD was unlikely to be detected in most states prior to 2002 using the available surveillance data (Figure 5.3; USAHA, 2001; Evans, Schuler, and Walter, 2014; Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024). In essence, surveillance for CWD began in approximately 1997, and surveys had limited detection power in most states prior to 2002; thus, the true rate of CWD expansion in the United States cannot be reliably measured. Nonetheless, the available evidence seems sufficient to regard CWD as a widespread animal health problem in the United States that has worsened over multiple decades.

DRIVERS OF EPIDEMIC GROWTH AND GEOGRAPHIC SPREAD

The geographic spread of CWD is influenced by both human activities and natural processes. The next sections discuss the anthropogenic and natural risk factors that contribute to the growth and geographic spread of CWD.

Anthropogenic Risk Factors

Humans can move infected cervids—alive or dead—over longer distances and in less predictable ways than cervids are understood to move generally under natural conditions. Inadvertent human transfer of infected live cervids is a well-documented mechanism for introducing CWD into distant locations (e.g., Sohn et al., 2002; Argue et al., 2007; Mori et al., 2024) and is a logical explanation of the discontinuous distribution of the disease as observed in North America. Studies indicate that international live-animal trade from North America also spread CWD to Asia (Sohn et al., 2002), but there is no evidence that the movement of infected live animals (or carcasses) from North America accounts for its emergence in Europe (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023). Once CWD is introduced into cervid herds, the natural day-to-day and seasonal movements of infected hosts within enclosures or on occupied range leads to local disease transmission and spread (Miller and Williams, 2003; Farnsworth et al., 2006; Jennelle et al., 2009; Xu, Merrill, and Lewis, 2022).

Beyond movements involving infected live cervids, the transfer of carcasses or parts thereof from infected cervids has been suggested as another potential mechanism for spreading CWD in the United States (Gillin and Mawdsley, 2018), but to date the supporting epidemiological data are anecdotal and not definitive (e.g., Kincheloe et al., 2021; Schultze et al., 2023). Similarly, transfers of other tissues, excreta, products, materials, or equipment contaminated with CWD prions have been suggested as potential contributors to geographic spread (Kincheloe et al., 2021; Schultze et al., 2023), but to date evidence of their actual role in spreading the disease is lacking (see Box 5.2).

Given that natural disease transmission factors are more difficult to mitigate than anthropogenic drivers, CWD management policies and regulations are biased toward human-related transmission risks (e.g., live cervid and cervid-part transportation restrictions, bans on urine-based cervid products, baiting and feeding regulations), irrespective of their relative importance to any given disease management scenario. It is likely that the movement of infected but healthy-appearing cervids (either intentional or accidental) has been the most significant of anthropogenic contributors to the introduction of CWD to new locations (Sohn et al., 2002; Kahn et al., 2004; Miller and Wolfe, 2023; Mori et al., 2024), but numerous other factors likely have accelerated, and will continue to accelerate, the spread and prevalence of CWD. The role of policymakers and regulatory agencies in addressing human-caused contributors to disease spread across both free-ranging and captive cervid management jurisdictions will remain critically important, even considering the numerous disease transmission modes and potential vectors of CWD that are beyond the influence of existing disease management tools or technologies.

Captive Cervid Populations

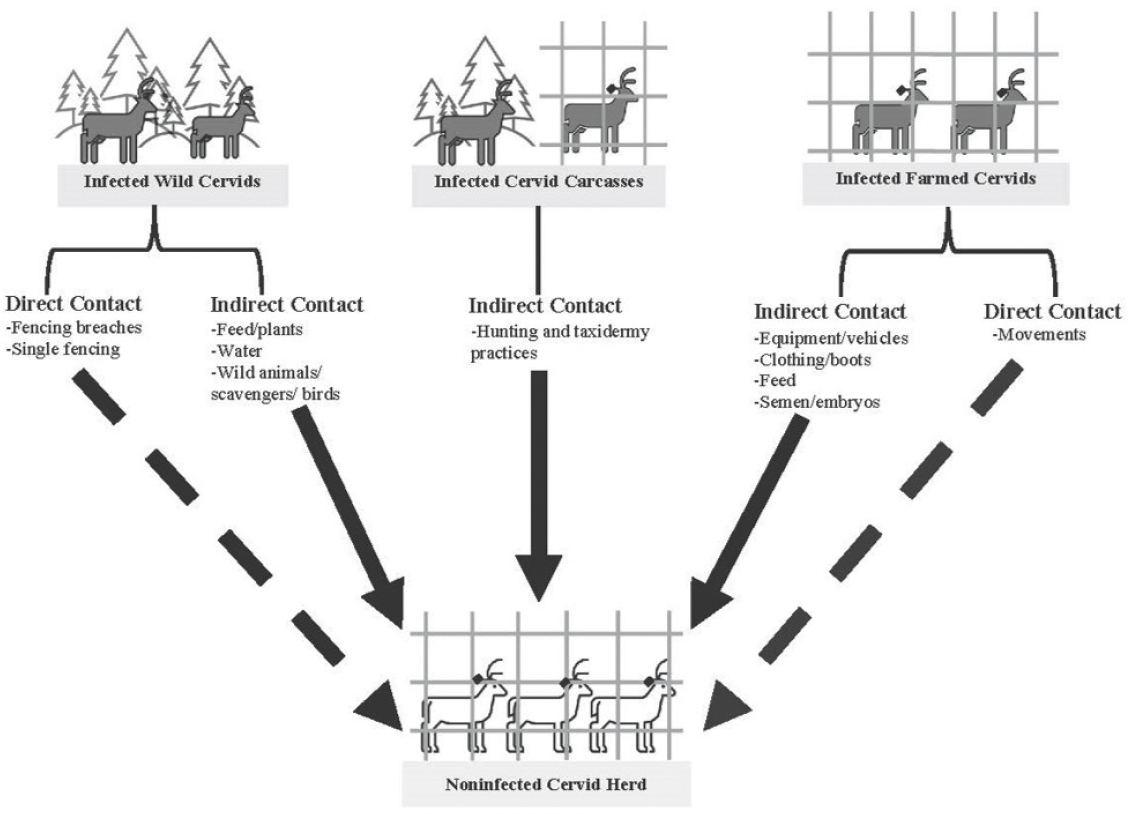

Key risk factors for CWD transmission among captive cervids primarily are related to direct contact with infected captive or local free-ranging cervid populations (Williams and Young, 1992; Kincheloe et al., 2021; Schultze et al., 2023). Well-characterized risks to captive cervids through direct contact include introduction of infected cervids or

infected tissues to facilities via live cervid movements or hunting and taxidermy (Williams and Young, 1992; Miller et al., 2004; Kincheloe et al., 2021; Schultze et al., 2023), as well as interactions with infected free-ranging deer through escapes, introductions, and possibly fence line nose-to-nose contact (Kincheloe et al., 2021). CWD prions have been detected in the semen and reproductive tissues of preclinical bucks (Kramm et al., 2019), although any role of transmission through sexual contact or artificial insemination is unknown.

Risk factors associated with indirect transmission are a growing concern, particularly where CWD has been detected in captive facilities with relatively high levels of biosecurity (Kincheloe et al., 2021; Schultze et al., 2023). Indirect contacts, such as through a contaminated food source or perhaps through prion transport by scavengers or other animals accessing captive cervid facilities, are a potential risk (see Figure 5.4) but have not been documented or verified. Risk factors for indirect CWD transmission can include farm proximity to infected free-ranging deer populations (less than 5 kilometers), presence of other species or scavengers on farm, as well as the presence or location of animal attractants on farm (e.g., location of water source along fence line, forest cover bordering a fence line, or on-premises carcass disposal) (Schultze et al., 2023); however, the roles of these potential risks remain unknown. Given the propensity of a variety of materials, including aluminum, rock, cement, polypropylene, stainless steel, and wood, to bind and retain prions, common pieces of farm equipment may serve as potential reservoirs for CWD (Pritzkow et al., 2018). Thus, equipment shared between farmed cervid operations may pose a risk for transmission via fomites (i.e., objects or utensils that can carry infectious agents) (Soto et al., 2023d), but this route of transmission has yet to be investigated thoroughly. Recent advances in prion detection via swabs of farm equipment that deer contact offer opportunities to investigate fomite transmission on or between cervid facilities (refer to Chapter 4 for more detail).

Free-Ranging Cervid Populations

In addition to natural areas where free-ranging cervids gather or visit with higher frequency, human activities that artificially congregate or attract cervids may be risk factors for CWD transmission. These include baiting, supplemental feeding, and mineral supplementation. Supplemental feeding and baiting are well recognized to alter

SOURCE: Schultze et al., 2023.

risks of transmitting bacteria, viruses, and prions (see Sorensen, van Beest, and Brook, 2014 for review; Hines et al., 2007; Thompson, Samuel, and Van Deelen, 2008) via direct and indirect routes of disease transmission. The risks related to CWD are similar. Environments frequented by deer contribute to CWD epidemics, and sites that congregate deer and elk at high densities are likely accelerating CWD transmission (Miller, Hobbs, and Tavener, 2006). Spilled grain associated with agricultural storage bins can be a significant attractant for mule deer (Mejía-Salazar et al., 2018). Supplemental grain feeding through a variety of methods also can artificially increase the concentration and intensity of use by white-tailed deer (Thompson, Samuel, and Van Deelen, 2008), although no method of artificial feeding was less risky for CWD transmission than natural feeding areas. Supplemental feeding via food plots (rather than grain sources) poses a similar risk for CWD transmission compared to natural deer browsing (Courtney, 2023). Deer using food plots had fewer direct and environmental contacts as compared to those using bait sites. Although more research is warranted to investigate food plots relative to CWD transmission, such findings hold some promise as a low-risk strategy for the nutritional supplementation of free-ranging cervid populations when considered necessary.

The use of cervid urine products as an attractant by hunters has raised concerns among certain individuals within the wildlife disease management community for its as yet undocumented but potential role in CWD transmission. The committee is unaware of any scent or urine facilities that have tested positive under the program to date. As discussed in Chapter 3, infected cervids may shed prions in their urine for months before showing clinical signs of the disease and over the course of infection may shed thousands of infectious doses (Henderson et al., 2015a; Plummer et al., 2017), based on a volume of 10 milliliters of urine containing an approximately 50% lethal dose (LD50) for cervidized transgenic mice (Henderson et al., 2015a). Because commercial urine lures often come from captive cervids, urine-derived lures could pose a risk for CWD transmission to free-ranging cervids (Miller and Miller, 2016). The relative extent to which prion-contaminated urine contributes to transmission is unclear, but some jurisdictions ban the use of urine and other scent lures to limit potential risk of transferring CWD. Recent hunter surveys demonstrate mixed responses on whether they were willing to abandon the use of urine/scent lures to reduce CWD transmission (Song, McComas, and Schuler, 2019; Siemer, Lauber, and Stedman, 2020). Expanded and standardized regulations around

urine sourcing and manufacturing is an alternative approach promoted by the Responsible Hunting Scent Association, which manages the Deer Protection Program (DPP). The DPP is a product certification program that requires cervid herd biosecurity measures above and beyond the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) Herd Certification Program (HCP), including the screening of urine for CWD prions by real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC). While this approach might garner greater consumer confidence in product safety, studies have not assessed consumer awareness. There have been no studies to quantify CWD risk reduction through this program.

Carcass Disposal

Miller and others (2004) documented infection of deer maintained in paddocks containing decomposed carcasses of deer that died of CWD. Infection occurred either through direct contact with the carcass remains or exposure to the contaminated environment. The deposition of harvested carcasses via hunting or taxidermy on premises containing captive cervids was associated with CWD detection in a limited number of captive facilities (Kincheloe et al., 2021). The deposition of prions following the decay of CWD-infected carcasses may lead to prion binding and enhanced infectivity in association with certain soil types (Johnson et al., 2007; Kuznetsova et al., 2023). Recent research demonstrates prions associated with carcass tissue decaying on the landscape (Schwabenlander et al., 2024) and even after burial (Soto et al., 2023d), which may serve as local sources of infection based on retention of prions in soil (Jacobson et al., 2010). Cervids and other ruminants naturally ingest and inhale a significant amount of soil, and the binding of prions to soil particles with subsequent transmission of soil-bound PrPCWD is a likely mechanism of CWD transmission (Beyer, Connor, and Gerould, 1994; Saunders, Bartelt-Hunt, and Bartz, 2008, 2012; Smith, Booth, and Pedersen, 2011; see Chapter 3 for more detail). Yet, there is also potential for surface contamination and uptake of prions by plants (Pritzkow et al., 2015) or by translocation and dissemination via scavengers (VerCauteren et al., 2012; Fischer et al., 2013; Nichols et al., 2015). Indeed, the flush of vegetation following carcass decomposition may attract and facilitate transmission to other deer (Towne, 2000; Carter, Yellowlees, and Tibbett, 2007). While their role in actual transmission remains unknown, there is active research into prions in soils and plants at known carcass sites.

Anderson (2023) summarizes the risk of CWD transmission via carcass disposal based on the volume of carcasses generated on an annual basis. Hunter-harvested carcasses generated in the 2021 hunting season alone were estimated to be approximately 5.9 million, a figure considered average by the National Deer Association (NDA).1 Even when hunter-harvested carcasses are removed from the local landscape, gut piles are often left by hunters at the harvest site. Although deer have not been observed consuming such remains, direct interactions with residual tissue have been observed, and those contacts or consumption of vegetation where tissues decomposed are considered risks for CWD transmission (Miller et al., 2004; Jennelle et al., 2009). Despite the evidence that carcasses or carcass sites are potential risk factors for CWD transmission, the precise mechanisms (e.g., prions associated with soil versus plant material versus residual tissue material), the actual prion load, the long-term risks, and the actual role in natural transmission are unclear. Even so, restrictions on carcass movement and proper carcass disposal have been implemented as tools for controlling CWD in captive and free-ranging herds.

Potential Roles of Feeding Practices and Feed Contamination

Multiple presenters and participants of the committee’s November 2023 and December 2023 information-gathering sessions (see Appendix B for meeting agendas) suggested that unidentified sources may contribute to CWD outbreaks in some locations. Some form of feed contamination was among the possibilities raised. Despite those voiced suspicions, no epidemiological investigations directly linking CWD outbreaks in captive or free-ranging cervids to contaminated feed were made available to this committee, nor have any been published. However, a case-control analysis based on epidemiological and questionnaire survey data gathered from captive cervid facilities in three states identified the use of “feed harvested from a known CWD-positive area or unknown location” as one of 37 variables potentially associated with CWD-positive herd status among 71 surveyed herds

___________________

1 See https://deerassociation.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/NDA-DR2023-FINAL.pdf (accessed July 25, 2024).

(Schultze et al., 2023, Appendix A). Committee members also acknowledge additional anecdotal reports or experience along these lines.

The potential role of feeding practices and feed contamination in CWD transmission and geographic spread seems most readily manifested and assessed in captive cervids. Cervids maintained in captivity typically require supplemental feed seasonally or year-round unless enclosures are lightly stocked with animals and sufficiently large to accommodate year-round natural foraging (Haigh and Hudson, 1993). Farming operations tend to employ more pastoral husbandry systems, whereas shooting/hunting operations tend toward less intensive husbandry within more natural landscapes (e.g., Haigh and Hudson, 1993; Kahn et al., 2004). Naturally occurring or cultivated forage plants (e.g., alfalfa, perennial grasses) also may be available depending on cervid species, location, size, and type of operation (e.g., Brooks and Jayarao, 2008). Some husbandry practices have been suggested anecdotally as potentially increasing CWD transmission risk, but none have been quantitatively demonstrated (Argue et al., 2007; Schultze et al., 2023; Mori et al., 2024).

Generally, cervid diets in commercial settings include a forage crop (e.g., grass hay or alfalfa, depending on species) and some form of grain or concentrated supplement (Haigh and Hudson, 1993; Kahn et al., 2004; Brooks and Jayarao, 2008; S. Burgeson, email correspondence with the committee, January 2, 2024; S. Shafer, written communication with the committee, January 8, 2024). The extent of animal-origin protein supplement use in commercial cervid operations—currently or historically—is uncertain. Forage crops (e.g., grass hay, alfalfa) are often sourced locally when available in sufficient quantities. More distant sourcing for forage feed may be used or can become necessary when annual weather conditions (e.g., drought, excess precipitation) or climate limit local availability.

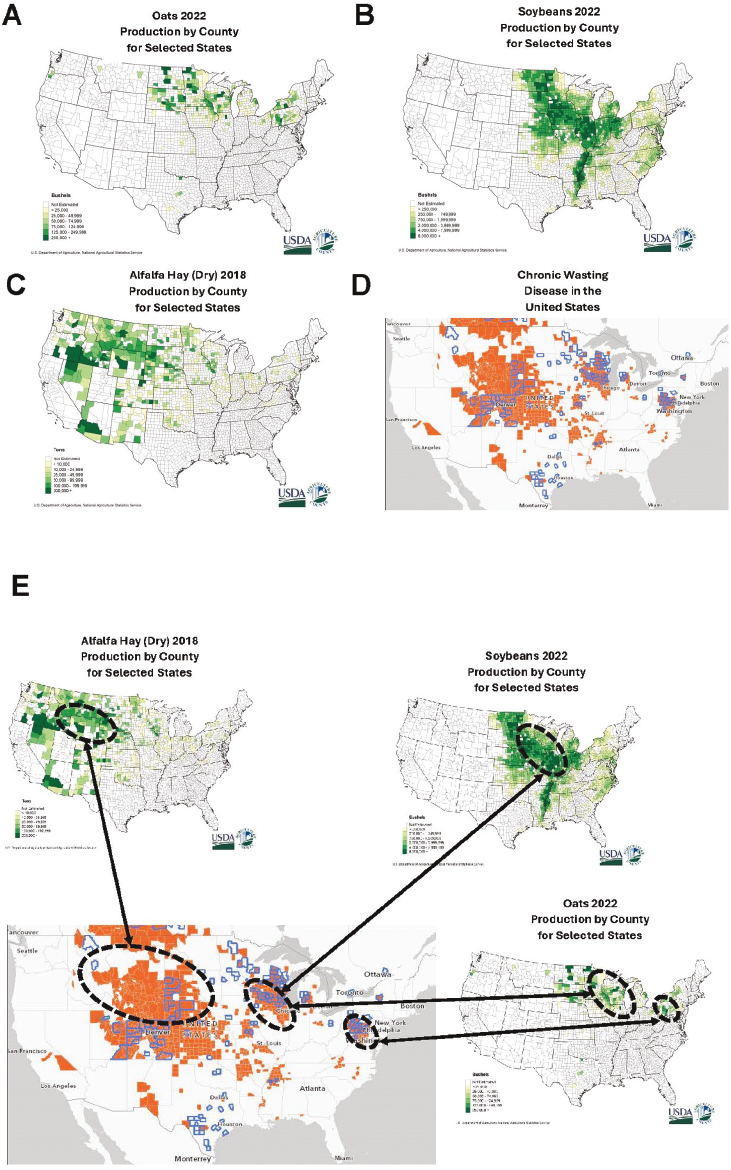

Grain and concentrated feed supplement products tend to come from a wider variety of locations (Brooks and Jayarao, 2008). Oats and soybeans are common ingredients in commercial formulations and recommended for supplementation in captive cervids (e.g., Haigh and Hudson, 1993). Some grain and forage crops made available to cervids in the United States are often grown in areas where CWD occurs (see Figure 5.5). Epidemiological investigation of feed and feeding practices is appropriate in the context of potential contributions to comprehensive control efforts given the potential for overlap between CWD occurrence and production of some crop types, the potential for prion surface contamination and uptake by plants (discussed in Chapter 3), and observations suggesting that feeding and husbandry practices may facilitate prion exposure (Argue et al., 2007; Schultze et al., 2023; Mori et al., 2024).

Natural Risk Factors

In locations where CWD occurs in free-ranging cervid herds, the natural day-to-day and seasonal movements of infected hosts within their occupied range leads to local disease spread across the landscape (Farnsworth et al., 2006; Jennelle et al., 2009; Xu, Merrill, and Lewis, 2022). Interactions within and between neighboring cervid social groups and overlapping home ranges expand the size of affected habitats over time. Exploratory, dispersal, and migratory movements of infected cervids—where they occur—can contribute to somewhat longer-distance spread (e.g., Conner and Miller, 2004; Jennelle et al., 2022), although such distances are still relatively short (e.g., generally tens of miles) in comparison to those achieved with human assistance (e.g., potentially hundreds or thousands of miles; Sohn et al., 2002).

Role of Cervid Population Ecology in Disease Risk

General knowledge about disease transmission indicates that when contact rates increase in association with population density, pathogen transmission is also expected to increase. CWD prion transmission is dependent on direct and indirect interactions among individual cervids (contacts) and thus may increase if contact rates increase. The frequency of infected individuals within a population can influence CWD dynamics (Habib et al., 2011; Storm et al., 2013). However, the density of populations also has an important role in CWD dynamics, and likely a combination of both frequency- and density-dependent transmission forces drives disease occurrence in deer (Almberg et al., 2011; Storm et al., 2013; Ketz, Storm, and Samuel, 2019). In areas of relatively low deer density and limited

SOURCES: (A) USDA NASS, see https://www.nass.usda.gov/Charts_and_Maps/Crops_County/ot-pr.php (accessed July 25, 2024); (B) USDA NASS, see https://www.nass.usda.gov/Charts_and_Maps/Crops_County/sb-pr.php (accessed July 25, 2024); (C) USDA NASS, see https://www.nass.usda.gov/Charts_and_Maps/Crops_County/al-pr.php (accessed July 25, 2024); (D) Chronic Wasting Disease Alliance (CWD Alliance), see https://cwd-info.org/map-chronic-wasting-disease-in-north-america/ (accessed July 25, 2024).

prions in the environment, direct contact among hosts likely has a more significant role than indirect contact with environmental reservoirs (Wasserberg et al., 2009; Almberg et al., 2011; Storm et al., 2013). Therefore, relatively high deer densities increase the probability of contact among deer and thus CWD transmission if CWD prions are present. In addition, cervid demographics such as sex and age composition may further increase the likelihood of contacts among social groups based on season, reproductive period, and associated behavioral characteristics. These factors are often the target of management actions to effectively reduce direct contact among cervids by reducing overall population density.

Attempts to quantify transmission risk through evaluating contact rates of free-ranging cervids revealed the dynamic social and environmental components of density-dependent and frequency-dependent disease transmission, which is often scale dependent (Storm et al., 2013) and has been reviewed by various authors such as Ketz, Storm, and Samuel (2019). Using radio-marked animals and methods such as proximity loggers (contact defined by 3-meter distance between individuals), proximity indices from GPS locations, or specific designations for individual investigations, multiple studies have demonstrated seasonal, demographic, and population density variation in contact rates and CWD risk among cervids.

Dobbin and others (2023) linked locations of contacts to the occurrence of CWD on the landscape, finding that contact probabilities of within- and between-group male paired contacts (dyads) in winter and between-group female dyads in summer were the best predictors of CWD risk. Silbernagel and others (2011) found that close proximity events (e.g., contacts) occurred in cropland and wetlands more often than expected given their availability, suggesting a preference among mule deer for these landscapes when available. Kjær, Schauber, and Nielsen (2008) found that direct contact rates among white-tailed deer during gestation were highest in forest cover, and then switched to agricultural fields and grasslands during the fawning season. Williams, Kreeger, and Schumaker (2014) found that daily indirect contact was three times more likely for white-tailed deer than direct contact, but direct contact rates were highest in winter, decreased in spring, bottomed out in summer, and rose in fall. Schauber, Storm, and Nielsen (2007) found contact rates to be 5-22 times greater for deer in the same social group in spring and fall, which then dropped to an even ratio for within groups and between groups in summer, suggesting the impact of social grouping on contact rates. The likelihood of contact is associated with various factors that differ widely in individual populations. Habitat preferences, social grouping, and seasonal movements may both explain and constrain relationships and, in conjunction with local host densities and the spatial scale, are crucial for understanding risk of transmission. Interestingly, Janousek and others (2021) found that estimated contact rates were 2.6 times greater for elk at supplemental feeding sites compared to baseline data, indicating an influence of anthropogenic factors on contact rates, similar to increased direct contacts and group size of white-tailed deer at bait sites (Courtney, 2023). While these studies are not exhaustive representations of the range of cervid ecology and dynamics, they represent efforts to quantify disease transmission risk and clarify the mechanisms associated with density- or frequency-dependent disease transmission. Increased disease risk associated with higher probabilities of contact is closely tied to cervid seasonal resource preferences and breeding cycles that also differ by region. Ultimately, these localized changes in contact rate are presumed to lead to increased transmission of CWD.

Environmental Hotspots

Areas of natural environmental risk for CWD transmission are investigated through two primary lenses: (1) prion shedding and contamination and (2) exposure leading to transmission. Where shedding and contamination are concerned, locations of high cervid density or use have been a focus; environmental characteristics that might contribute to prion persistence and bioavailability (e.g., soil and vegetation characteristics) are being explored relevant to exposure and transmission. Locations of high cervid density or use are considered natural “hotspots,” recognizing the greater potential for CWD deposition into the environment by infected individuals and further transmission to susceptible cervids due to shared use (see Table 5.1). Habitat preferences by cervids and the spatial configuration of those habitats on the landscape can influence the spatial heterogeneity of CWD detections among cervids across the landscape (Evans et al., 2016; Farnsworth et al., 2006).

Observational studies have focused largely on identifying associations between environmental characteristics and CWD prevalence (mostly estimated through harvest-based surveillance). For example, harvest-based CWD

TABLE 5.1 Summary of Potential Hotspots for CWD Transmission Among Cervids

| Natural cervid hotspots | Study design | Key findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral licks | Prion detection | PrPSC in soils and water from mineral licks in CWD foci using protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA) detection | Plummer et al., 2018 |

| Scrapes | Prion detection | PrPSC by real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) assay from soil and tree branch samples at scrape sites | Huang et al., 2024 |

| Bed sites | Behavioral | Visited by mule deer, particularly females, with greatest frequency during late gestation and fawning | Mejía-Salazar et al., 2018 |

| Wintering areas | Spatial/behavioral epidemiology | Winter site fidelity along with limited local movement and interactions, best explained spatial distribution of CWD prevalence in mule deer | Conner and Miller, 2004; Farnsworth et al., 2006 |

surveillance data from Wisconsin and Illinois revealed that larger and compact forested areas, as well as low elevation areas close to large rivers, were associated with higher CWD prevalence in white-tailed deer (O’Hara Ruiz et al., 2013). In contrast, Evans and others (2016) and Kjær and Schauber (2022) found forested landscapes had a different relationship with CWD infections, where areas with less forest had a greater risk of CWD detection in deer. In the northeastern United States, the likelihood of CWD infection decreased 6.3% for every 1% increase of forested land (Evans et al., 2016). Conversely, open and developed habitats increased the odds of CWD infections. Kjær and Schauber (2022) explored landscape configuration further through spatially explicit simulation modeling and demonstrated that CWD prevalence peaked earlier and at higher levels in areas dominated by agriculture with only forest fragments in comparison to contiguous forest areas. However, these relationships between habitat and CWD risk are likely context-specific given the variability in landscapes in which cervids live and CWD has been detected.

CWD surveillance data also have been used to build empirical evidence supporting the role of soil characteristics in CWD transmission. As mentioned in Chapter 3, prions have been shown experimentally to adsorb strongly to clays or clay soils (Johnson et al., 2006b; Saunders, Bartz, and Bartelt-Hunt, 2009) compared to sandy or other soils, and clay-bound PrPSc demonstrates higher rates of oral infection (Johnson et al., 2007; Wyckoff et al., 2016). CWD surveillance data for empirical evidence of the hypothesized role of clay in CWD transmission indicated a negative association between soil clay content and CWD in the Midwest (O’Hara Ruiz et al., 2013). Dorak and others (2017) examined this further in a follow-up study of the persistence of CWD (defined as the detection of greater than three CWD cases in deer in an area, using harvest-based surveillance) in association with soil characteristics in Illinois and found that less than 18% clay content and greater than 6.6 pH were the most important soil characteristics associated with CWD persistence. However, the association between clay content and CWD risk differs among studies from different regions. In Colorado, there was a positive association between clay content and CWD in deer (Walter et al., 2011). Other studies suggest soil type or CWD strain characteristics (Saunders, Bartz, and Bartelt-Hunt, 2012) or inherent biases in CWD sampling (Conner, McCarty, and Miller, 2000; Osnas et al., 2009) among regions may be associated with observed patterns of CWD.

Cervid behavior and movement or habitat use may help identify more local hotspots of potential CWD transmission on the landscape. Camera-trapped female mule deer in a CWD focus in Saskatchewan, Canada, visited bed sites during late pregnancy and fawning with greatest frequency (as compared to grain sources, salt licks, browse sites, waterholes, trails, rubs, mortality sites, and bed sites used during any other season) (Mejía-Salazar et al., 2018), although neither the deer nor the visitation sites were tested for CWD. At higher spatial scales, the seasonal movement of mule deer populations in Colorado was examined in association with patterns of CWD. Wintering areas best explained the spatial distribution of CWD in mule deer (Conner and Miller, 2004). Additional research suggested that winter site fidelity, combined with limited movement and local interactions in these areas, may increase CWD transmission within a wintering population (Farnsworth et al., 2006). These authors also suggested that anthropogenic land use may influence natural deer use and density, potentially adding to transmission.

With advances in environmental prion detection technologies, there is a growing body of research that tests hypotheses of prion deposition at predicted cervid “hotspots,” such as mineral licks in CWD foci in Wisconsin that contained prions (6-19% prevalence), based on PMCA detection (Plummer et al., 2018). These may be important sites for indirect transmission given their attraction for cervids and other species and the association of prions with clays at such sites (see above). Deer also create scrapes on the landscape for communication during the breeding season. These sites can be visited and used repeatedly by the same or different individuals during each breeding season (Egan et al., 2023). Preliminary results demonstrate that PrPSc can be detected by RT-QuIC in soil and tree branch samples at deer scrape sites (Huang et al., 2024), suggesting scrapes might also contribute to indirect transmission of CWD prions via oral or intranasal routes. Much remains unknown regarding natural transmission of CWD among free-ranging populations deer (e.g., direct versus indirect exposure) and specific characteristics of potential CWD hotspots; however, as the capacity to detect CWD in environmental samples continues to expand and be optimized, there may be greater opportunity to explore these questions under natural conditions.

Potential Effects of Predators and Scavengers

In contrast to the clear role of human activities and host animal movements reviewed above, the role of predators and scavengers in spreading (i.e., transporting across geographical regions) or dispersing (e.g., scattering radially around a carcass) CWD prions is undetermined. While there is no evidence of CWD infection in predatory and scavenging mammals or birds (Jennelle et al., 2009; Wolfe et al., 2022), individual animals could disseminate infectious prions either directly by moving carcasses of infected cervids, or by depositing prions in their feces some distance away from the original location of an infected cervid carcass. Any such role in transferring CWD in natural ecosystems, or transmitting CWD to uninfected cervids, would be difficult to document; there is currently no evidence that such exists, and no epidemiological investigations directly linking CWD outbreaks in captive cervids to scavengers or predators have been published. If such transfer does occur, patterns of CWD spread or emergence in new areas may correlate with dispersal or movement patterns of common predators or scavengers. One case-control analysis based on questionnaire survey data gathered from captive cervid facilities in three states identified a possible association between scavenger activity and CWD-positive herd status among 71 surveyed herds (Schultze et al., 2023), although in all, 37 variables were potentially associated with CWD-positive herds.

A variety of mammalian and avian species prey upon and consume free-ranging cervids or consume cervid carcasses on the landscape. These species are essential components of functioning ecosystems, and the cervids consumed or removed can be major components of their diet (Newsome et al., 2016; LaBarge et al., 2022). Experimental evidence indicates that some CWD prions remain after passage through the digestive system of coyotes (Canis latrans) (Nichols et al., 2015) and cougars (Baune et al., 2021), and that infectious scrapie prions can pass through the digestive system of crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) (VerCauteren et al., 2012). Feces of wild free-ranging coyotes and cougar in areas where CWD occurs in free-ranging cervids have been collected and found to contain CWD prions (Inzalaco et al., 2024).

On the other hand, selective removal of CWD-infected cervids through natural predation has been hypothesized as a mechanism for suppressing the growth of CWD epidemics (e.g., Wild et al., 2011) and could have a part in changing the population stability of elk (Sargeant, Weber, and Roddy, 2011). Limited field data indicate that mountain lions (Puma concolor) selectively prey upon CWD-infected mule deer (DeVivo et al., 2017; Fisher et al., 2022; Krumm et al., 2010), lending empirical support to modeled mechanisms for local natural control via predation. Experimental studies also suggest the potential for consumption of prion-laden tissue by predators to reduce prion loads associated with cervid carcasses in the environment (Nichols et al., 2015; Baune et al., 2021). Theoretical models using predator/prey dynamics suggest the role of wolves in removing infected deer from the population could significantly reduce or limit the occurrence of CWD in infected populations (Wild et al., 2011), but, to date, there is no evidence to substantiate this effect in the relatively few areas where CWD and wolves overlap. Furthermore, the extent to which predators directly or indirectly affect the distribution or availability of prions in the environment is poorly understood. The amount of prion present in cougar feces was considerably less than in the material ingested, and the relatively rapid passage of food through the gut (1-4 days) limited the

time frame when feces containing prions were deposited (e.g., prions were only present in the first defecation after consumption; Baune et al., 2021). Predators and scavengers may dilute prions on the landscape (Fischer et al., 2013), but whether communal rendezvous, denning, or roosting sites could concentrate prions remains unexplored. Other natural phenomena (e.g., flooding, wind, flowing waters) could theoretically contribute to spread, but there is no empirical evidence of this.

Potential Risk Associated with CWD Strains

As noted in Chapter 2, CWD strains are epidemiologically relevant for CWD as they can manifest with different virulence, recalcitrance in the environment, host ranges, distribution in animal tissues, shedding potentials, and other biological and biochemical attributes (see Box 5.3 and Otero et al., 2023). Although the current number of strains has not yet been delineated due to the complex nature of strain characterization, there are, minimally, three strains in white-tailed deer (Johnson et al., 2011a; Duque Velásquez et al., 2015; Herbst et al., 2017; Hannaoui et al., 2021; Angers et al., 2010; Bian et al., 2019, 2021) and at least one strain in mule deer (perhaps similar to the predominant strain in white-tailed deer). There appear to be several strains in elk, likely due to PRNP allele differences (O’Rourke et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2018, 2020). As these strains have different biochemical properties (i.e., resistance to proteinase digestion) and differences in host range, the increasing number of strains prevents an understanding of transmission properties, thus limiting the design of strategies on how to control their continued spread.

IMPACT OF CWD ON CERVID POPULATION DYNAMICS

Understanding how animal movement and behavior can be associated with CWD transmission risk and disease effects is important for wildlife conservation and disease management. Ultimately, this information is needed to establish if animals are at risk and if detrimental population effects are possible. The mission for many fish and wildlife agencies is the management and conservation of sustainable healthy fish and wildlife populations for the benefit of current and future publics. Populations of cervids are defined as a single species living in the same place at the same time. These definitions may differ based on the wildlife management goal of interest, and they can affect how risks like CWD on a population can be determined. Thus, establishing clear signals of disease impacts on free-ranging populations is challenging but important for understanding the trade-offs between epidemic growth and control efforts that also may affect cervid abundance.

Robust and reliable estimates of population measures (such as abundance, survival, harvest rates, and recruitment [addition of juvenile animals into the breeding population]) are critical components for understanding how CWD affects free-ranging cervid populations but are difficult to assess with confidence in free-ranging populations. CWD can result in significant mortality in free-ranging cervids, based on studies using radio-marked animals and subsequent postmortem examination. For example, white-tailed deer in Arkansas with high prevalence of CWD in all age classes had a significant increase in mortality of CWD-positive deer compared to deer in which CWD was not detected by antemortem testing (J. Ballard, presentation to the committee, December 14, 2023). Reduced survival of prime-aged females and lower recruitment would be expected to result in depressed population growth that could lead to decline. Similarly, overall CWD prevalence in white-tailed deer (n = 161) in Wyoming was 35.4%, and the two leading causes of mortality were hunter harvest and CWD (Edmunds et al., 2016). In contrast to the expected pattern of higher apparent prevalence among adult male deer than among females (Miller et al., 2000; Grear et al., 2006; Miller and Wolfe, 2023), this herd showed a notably higher prevalence in females (42%) than males (28.2%). In total, 17 deer died with clinical CWD (12 females, 5 males). However, bias due to higher harvest of males (76%) and hunter preference for adult males may have occurred. CWD-positive deer had a significantly lower survival rate (0.396) than CWD-negative (0.801) and were 4.5 times more likely to die annually. DeVivo and others (2017) found average CWD prevalence was higher in male mule deer (43%) than females (18%), CWD-positive mule deer were more susceptible to mountain lion predation (n = 20) and harvest (n = 4), and clinical CWD was the second highest cause of mortality (n = 14). CWD-positive mule deer in their study had significantly lower estimated survival rates (0.32) than CWD-negative (0.76), but there was no significant difference (SD) in fawn recruitment rates between CWD-positive (0.56, SD = 0.65, 95%; confidence interval = 0.30-0.82) and CWD-negative mule deer (0.48, SD = 0.65, 95%; confidence interval = 0.33-0.63). Similar patterns of disease-associated mortality and increased vulnerability to predation occurred in a nonhunted mule deer herd in Colorado (Miller et al., 2008; Fisher et al., 2022). Finally, researchers evaluated cause of death and pathology for over 1,000 uniquely marked white-tailed deer over a 5-year period in a Wisconsin CWD focus (Gilbertson et al., 2022). They found that infectious disease was one of the leading causes of death and of 245 mortalities with post mortem CWD tests, 42.4% were positive. Prevalence of CWD increased with age among young and prime-aged deer, and some fawns were positive. Similarly, annual survival probabilities (excluding harvest) for a cohort of free-ranging elk declined from 0.97 (Bayesian confidence interval 0.93-0.99) in 2008 to 0.85 (0.75-0.93) in 2010, with declines in survival attributed almost entirely to CWD (Monello et al., 2014). Another striking example of CWD impacts on survival was observed among ranched elk in a Colorado herd, wherein only 16% (13 of 82) of CWD-infected elk lived for 1 year after a positive biopsy, compared to 60% of the biopsy-negative elk surviving one or more years in this herd (Haley et al., 2020a). Thus, reduced survival in young and otherwise non-food-limited captive elk further demonstrated the demographic implications of CWD.

Few studies successfully characterized population impacts with sufficient time and disease progression to show how population growth patterns in relatively long-lived species are affected by disease mortality. Funding and political support for such studies typically do not last long enough to determine with confidence changes in population growth rate as a direct result of CWD. Despite these challenges, CWD has been associated with detrimental effects on populations of white-tailed deer, mule deer, and elk in several states. A Wyoming population of white-tailed deer with an estimated average annual CWD prevalence of 23.8% declined despite its relatively high reproductive potential (Edmunds et al., 2016). This was evidenced by a reduced annual survival rate, with infected deer being 4.51 times more likely to die and contribute only 0.896 to population growth, which translates to an

overall 10.4% annual projected population decline (Edmunds et al., 2016). In contrast, annual survival for adult female white-tailed deer in many other regions exceeds 90%, and population growth rates are above 1.0 even when female deer are actively harvested. A mule deer population in Wyoming, which typically uses different habitats and occurs at lower densities than white-tailed deer populations, also declined in the presence of CWD (DeVivo et al., 2017). Finite population growth rate was lower than the previously mentioned white-tailed deer populations study at 0.79, or a 21% annual projected population decline, and CWD was a significant contributor through increased mortality of infected animals (DeVivo et al., 2017). Significant decline, in a mule deer population in Saskatchewan, Canada, with high disease prevalence has been attributed—at least in part—to CWD (Saskatchewan Ministry of Environment, 2020; Stasiak, Perry, and Bollinger, 2023). Similar mule deer declines have been observed across the geographic range of mule deer for a myriad of reasons, posing an immediate concern for additive mortality due to CWD (Heffelfinger and Krausman, 2023).

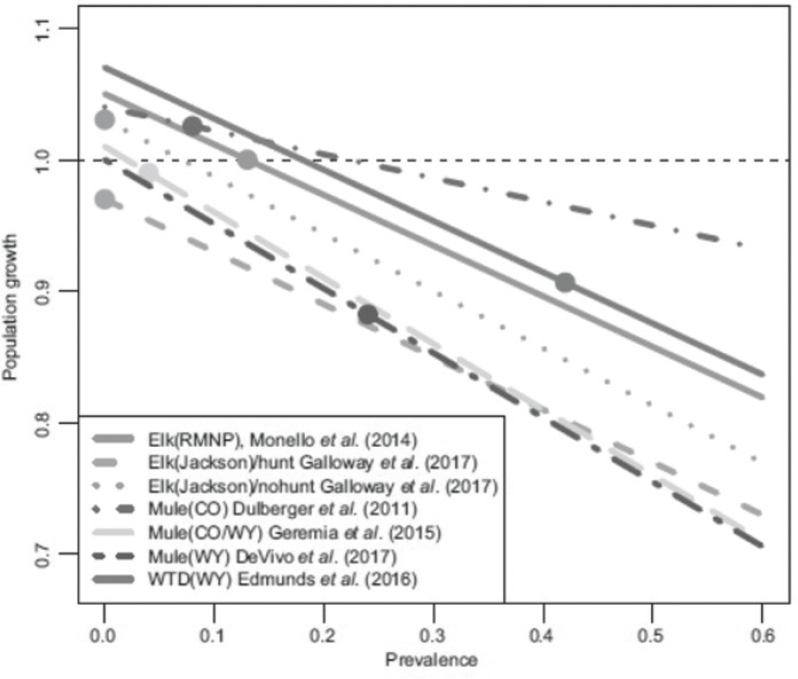

Regardless of deer species, the impact of CWD on the life or death of fawns often is negligible (Dulberger et al., 2010; Blanchong et al., 2012; Edmunds et al., 2016; DeVivo et al., 2017), indicating that the adult mortality accompanying increased prevalence, in concert with other demographic and environmental factors, is likely driving effects on the population growth rate (Ketz, Storm, and Samuel, 2019). In the absence of hunting losses, Rocky Mountain elk had slightly more resilience to CWD at the population scale, with population growth rates near 1.0 (population stability). However, clear negative effects on population parameters would be more likely as prevalence increases in combination with food and resource limitations or with the addition of hunting (e.g., Monello et al., 2014; Sargeant, Weber, and Roddy, 2011). Ketz, Storm, and Samuel (2019; see Figure 5.6) projected population growth trajectories with increasing prevalence based on point estimates

SOURCE: Ketz, Storm, and Samuel, 2019.

of prevalence and population growth reported for cervid populations in Colorado and Wyoming where CWD has existed for several decades. These examples provide a stark one-way projection for other populations that may reach similar prevalence levels.

Simulation-based population models also have projected negative population impacts (see reviews by Ketz, Storm, and Samuel, 2019; Winter and Escobar, 2020; Belsare and Stewart, 2020; Thompson et al., 2024; Kjær and Schauber, 2022). The modeled consequences underscore the potentially significant ramifications of CWD and its risk to wild cervid populations and the systems (both ecological and socioeconomic) that rely on them. Furthermore, efforts to use limited empirical cervid population data in combination with advanced quantitative models have addressed some crucial gaps in existing knowledge. For example, resource use and selection by cervids likely interact with prevalence and demographics on the landscape to affect differences in population impacts (e.g., Evans et al., 2016; Kjaer and Schauber, 2022). The management and regulated harvest of cervid populations is then another factor that influences the trajectory of a cervid population, as demonstrated via modeling (e.g., Foley et al., 2016; Gross and Miller, 2001). For example, the models described by Foley and others (2016) illustrated that a deer population without CWD or harvest was projected to increase 1.42% annually within 25 years, whereas modeled populations with CWD and without harvest showed markedly lower annual growth (0.41, −1.72, or −10.33%, where negative values reflect a population decline) at low, medium, or high CWD prevalence, respectively. Conner and others (2021) and Potapov and others (2016) also highlighted the role of harvest management to affect CWD prevalence. Increasing the number of hunters and the harvest total of male deer led to lower prevalence the next year. Harvesting animals closer to peak breeding times lowered the CWD prevalence, which aligns well with most agency-regulated hunting periods. These studies collectively suggest that CWD prevalence and its impact on deer populations are influenced by a multitude of factors, and comprehensive and long-term approaches to measuring impacts and subsequent management actions are critical.