State of Knowledge Regarding Transmission, Spread, and Management of Chronic Wasting Disease in U.S. Captive and Free-Ranging Cervid Populations (2025)

Chapter: 4 Diagnostics and Surveillance

The sensitive and specific detection of CWD and CWD prions in clinical and environmental specimens is an important component in CWD management across North America and beyond. Extensive research demonstrates that the most accurate marker of any prion infection is the disease-associated prion protein (PrPSc) (Prusiner, 1982; Guiroy et al., 1991). Accumulation of this misfolded protein is most readily observed in the central nervous system—especially in advanced stages of disease—although it may be found at lower levels in a range of tissues, bodily fluids, and excreta during the course of infection (Henderson et al., 2020; Tewari et al., 2022; Henderson et al., 2015a; Hoover et al., 2017). Primary diagnostic approaches commonly used in state and federal diagnostic laboratories include immunohistochemistry (IHC; Guiroy et al., 1991) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA; Hibler et al., 2003). These are mainly used with tissues collected after death, primarily from the obex1 region of the brainstem and the retropharyngeal lymph nodes (RPLN). Because CWD considered a notifiable disease in captive cervids by the USDA, these assays require regulatory approval for their use in diagnostic settings.2 In contrast, experimental as yet unapproved diagnostic approaches have been under continuous development since the early 2000s and have been demonstrated to be sensitive for tissues and bodily fluids collected both antemortem (before death) and postmortem (after death). They can be used for non-cervid biologic samples like insects and plants, and environmental samples ranging from soils to surface swabs. Some of these techniques, including protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA; Kurt et al., 2007; Saá, Castilla, and Soto, 2005) and real-time quaking-induced conversion assay (RT-QuIC; Atarashi et al., 2007), have potential for supplementing conventional approved diagnostic approaches. Lack of regulatory approval is partially the result of a lack of coordinated interlaboratory cross-validation studies. Regardless of the test, diagnostic testing in CWD surveillance requires careful consideration to ensure both cost-efficiency and confidence in detection.

This chapter provides a description of the diagnostic tests currently available for the detection of CWD and their application in surveillance. Discussion is focused on test characteristics (e.g., sensitivity and specificity), advantages and disadvantages, the suitability of each test for different types of samples (biological versus environmental), and how different samples and tests can be used in surveillance. The state of knowledge related to testing of live cervids and new directions in environmental detection and surveillance also are addressed.

SENSITIVITY AND SPECIFICITY

There are distinct ways in which the results of different diagnostic tests may be quantified, although similar terminology applied to the different tests can create confusion. For example, test “sensitivity” may refer either to the lowest quantity of a target that can be confidently detected by an assay (i.e., analytical sensitivity) or to the probability that an assay will accurately characterize an infected animal as positive (i.e., diagnostic or epidemiologic sensitivity) (Saah and Hoover, 1997). The former is critical in fully understanding the lower detection limits of a test, and it is generally assessed before diagnostic or epidemiologic sensitivity is considered. The latter is an important component of test accuracy, which considers an animal’s true disease status. Diagnostic specificity is the second important element of test accuracy and refers to the probability of a test to accurately classify an uninfected or healthy animal as negative. High diagnostic specificity means that an animal infected with another pathogen (e.g., bovine tuberculosis) will not test positive on a test designed to detect CWD.

The goal of any diagnostic test is to achieve the highest sensitivity and specificity possible, although no diagnostic test is perfect and there will always be compromises to optimize results in one way or another. A lower sensitivity means that more animals that have the disease of interest will be misclassified as disease-free. A lower specificity means there will be more false positives (i.e., more uninfected animals will incorrectly test positive), which could have regulatory ramifications depending on jurisdictional policies. In many cases, optimizing for one diagnostic criteria (e.g., sensitivity) comes at the cost of reductions in the other (specificity). Thus, it is not uncommon in disease diagnostic testing to utilize a combination of tests that vary in their sensitivity and specificity. For example, a highly sensitive test may be used to screen animals initially, but where false positives are a concern,

___________________

1 The obex is a region of the brainstem that narrows and joins the spinal column.

2 This sentence was revised after release of the report to clarify that federal regulations currently designate CWD as a notifiable disease only in captive cervids.

a second, highly specific test may be used for confirmation. Beyond understanding the sensitivity and specificity of a test, it is also useful for practitioners to understand the positive and negative predictive values of a test: if an animal tests positive, what is the probability that the animal is truly infected or diseased? Understanding this provides information on how well a test will perform when disease prevalence varies across populations. However, such diagnostic criteria (positive and negative predictive value) are less frequently estimated. Appendix D summarizes information available on the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of different tests for CWD when applied to different biological samples. Box 4.1 provides additional information related to challenges in the estimation of diagnostic sensitivity and specificity.

CURRENT DIAGNOSTIC TESTS FOR CWD

Diagnosis of CWD in cervids has been based on the detection of the misfolded, PrPSc. Tests can be categorized by how the abnormal prion proteins are detected (Haley and Richt, 2017): antigen-antibody (“immunoreactive”) interactions, laboratory-based (“in vitro”) amplification assays, or some combination of the two. Table 4.1 lists these tests and describes their testing costs, laboratories,3 and turnaround times. Historically, the diagnosis of prion disease has relied on the detection of PrPSc in the brain or lymphoid tissues of animals using western blot (WB), IHC, and ELISA (Bolton, McKinley, and Prusiner, 1982; Haley et al., 2017). Amplification assays such as PMCA and RT-QuIC demonstrate greater sensitivity detecting low concentrations of prions in tissues (Table 4.2; McNulty et al., 2019) and allow earlier detection of CWD prions before or after death, including during earlier stages of infection using alternative tissues and bodily fluids. Such tests are useful for rapid screening, but disease diagnosis must still be through IHC or ELISA. Furthermore, enhancements to PMCA (e.g., addition of plastic beads or co-factors; Gonzalez-Montalban et al., 2011; Haley et al., 2013) and RT-QuIC (e.g., sodium phosphotungstic acid

___________________

3 Because humans are not known to serve as hosts to CWD prions, the CDC currently recommends that work with CWD prions be conducted in biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) facilities (CDC and NIH, 2020). There are four biosafety levels, and BSL-2 measures are put in place to protect laboratory workers from “moderate hazards to personnel and the environment” (see https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47695; accessed October 8, 2024).

TABLE 4.1 Comparison of Diagnostic Testing Options Available or in Development for CWD

| Test | Use | Sample type (PM, AM, EN)a | Sample condition | Cost per sampleb | Turnaround timec | Laboratories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoreactive tests | ||||||

| IHC | Official testing | Generally PM Some AM | Formalin-fixed | $21-42 | 1-2 weeks | National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) |

| ELISA | Official testing | Generally PM | Fresh | $22-25 | 8-24 hours | NAHLN |

| WB | Official testing | PM | Fresh | $0 | 1-2 weeks | National Veterinary Services Laboratory (NVSL) onlyd |

| In vitro amplification assays | ||||||

| PMCA | Research | PM, AM, EN | Fresh or frozen | ~$5 (materials only) | 3-21 days | Research |

| RT-QuIC | Research | PM, AM, EN | Fresh or frozen | ~$7 (materials only) | 24-72 hours | Research |

| Minnesota quaking-induced conversion (MN-QuIC) | Research | PM, AM | Fresh or frozen | ~$12 (materials only) | 24 hours | Research |

NOTE: Experimental assays have not seen general field deployment; true costs have not yet been fully realized.

a PM: postmortem tissues; AM: antemortem tissues; EN: environmental samples.

b Published prices for IHC and ELISA obtained from two NAHLN laboratory websites (accessed January 30, 2024). Does not include prices applied to hunter-submitted samples. All other estimates are non-commercial pricing and do not include labor costs.

c Turnaround times for IHC and ELISA were obtained from two NAHLN laboratory websites (accessed January 30, 2024). These figures include time required for sample preparation, testing, and reporting as a service; other test turnaround times only estimate sample preparation, testing, or pathologist interpretation. ELISA turnaround time may vary based on sample submission volume and availability of commercial reagents.

d Western blot is offered by the NVSL (not other NAHLN laboratories) at no cost as an official confirmatory test following a positive IHC test.

TABLE 4.2 Comparison of Prion Detection in a Dilutional Series of CWD+ Cervid Brain Pool

| Category | Cervid brain pool homogenate dilution | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assay | 10−1 | 10−2 | 10−3 | 10−4 | 10−5 | 10−6 | 10−7 | 10−8 | 10−9 |

| Western Blot | |||||||||

| BioRad ELISA | |||||||||

| Mouse Bioassay | ND | LD50 | ND | ND | |||||

| sPMCA/WB | ND | ND | |||||||

| RT-QuIC | NT | NA | |||||||

| sPMCA/RT-QuIC | NT | ||||||||

NOTES: Shading represents relative prion positivity (lighter shading represents lower relative prion positivity, and darker shading represents higher relative prion positivity). 10−x notates the dilution of brain pool, with larger negative numbers representing higher dilutions (i.e., less brain) used in each assay.

BioRad ELISA: the USDA official enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; sPMCA: protein misfolding cyclic amplification; WB: western blot; RT-QuIC: real-time quaking-induced conversion; ND: dilutions at which bioassays were not done; NT: dilutions not tested by RT-QuIC or PMCA; LD50: the lowest dilution at which 50% of the experimental mice were killed.

MN-QuIC had not been developed when this table was published, but information about its sensitivity and specificity can be found in Appendix D of this report.

SOURCE: McNulty et al., 2019.

precipitation, addition of iron oxide beads or silica nanoparticles, or sample pre-treatments; Christenson et al., 2023; Denkers et al., 2016; Henderson et al., 2015b) improve sensitivity. Newer diagnostic tests using alternate amplification technologies are also emerging (Christenson et al., 2022). Although not used for routine diagnosis and surveillance (because they are not feasible for large numbers of samples considering the costs and time involved), bioassays (e.g., using experimental inoculation in genetically modified mice or other species to detect infectious prions in samples) have also been utilized to confirm prion presence, particularly when infectivity of a sample is in question. Bioassays may be the only definitive method of prion detection, and until amplification-based test results are further validated as accepted reference standards, their use is limited to confirming disease status of conventional test-negative, amplification test-positive samples. None of the above-mentioned tests are designed to evaluate prion infectivity. Finally, several publications have assessed the utility of cell culture systems for prion detection and quantification (e.g., Bian et al., 2010; Thapa et al., 2022). Although this approach may help supplant the need for mouse bioassay, its utility in diagnostics is limited due to a limited number of cervid species and prion strains to which it can be applied.

Immunoreactive Assays

The detection of CWD prions in tissues via IHC relies on the binding of antibodies against the prion protein (Guiroy et al., 1991). This assay has long been the official test, in many respects the “gold standard” (Box 4.1) for postmortem detection of CWD prions in the obex and specific lymph nodes in the neck region (RPLN) for regulatory testing purposes. This approach requires examination and confirmation by a trained pathologist. Because amyloid accumulates in these tissues over time, IHC results have been reported as a binary (positive/negative) or as a qualitative estimate of disease stage (e.g., Miller and Williams, 2002; Spraker et al., 2002b; Spraker et al., 2004; Keane et al., 2008a; Fox et al., 2006; Thomsen et al., 2012; Haley et al., 2016a; Haley et al., 2016b; Spraker et al., 2015; also see Chapter 2). The use of acid treatment or protease digestion techniques to effectively degrade the normal prion protein ensures detection of the disease-associated prions (Guiroy et al., 1991), although these techniques have limited ability to detect forms of PrPSc that are sensitive to protease that may occur in some infections (Safar et al., 2005). As a result, despite its high specificity for detecting PrPCWD, IHC sensitivity is lower than both bioassays and amplification assays (Haley et al., 2012; Haley et al., 2009a), further discussed below.

The commercial Bio-Rad CWD ELISA test kit is an official test for CWD when used according to USDA program standards (USDA APHIS, 2019). ELISA is reasonably fast and can handle many samples at a time. It has equivalent sensitivity and specificity to IHC and can be used for testing lymphoid/neural samples, beyond RPLN and obex, for CWD (e.g., tonsil and rectoanal mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue, RAMALT; Haley and Richt, 2017; Hibler et al., 2003).4 Like IHC, ELISA may not be able to detect low concentrations of PrPSc (McNulty et al., 2019).

Although rarely used, western blotting is another diagnostic method dependent on antibody-antigen interactions, but unlike IHC or ELISA, detection depends on finding CWD PrPSc in partially purified tissues passed through a gel matrix (Guiroy et al., 1993). This technique separates proteins based on mass and allows direct visualization of different sized protein bands, an essential feature required for the identification and discrimination of different prion strains. Because western blotting, like IHC, relies on separating abnormal (PrPSc) from normal (PrPC) prions through enzymatic (protease) digestion, it cannot detect CWD prions that are less resistant to the enzyme; the test may have limited value in detecting low concentrations of prions that may be present in early, nonclinical stages of infection (see Table 4.2).

In Vitro Amplification Assays

Over the past two decades, two distinct pathways for in vitro prion amplification have been developed. These pathways largely mirror the development of nucleic acid amplification assays for the detection of other infectious agents, beginning with a qualitative assay (PMCA) first described in 2005 that is similar to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of nucleic acids (Saá, Castilla, and Soto, 2005). In 2007, a more quantitative assay (RT-QuIC) with utility comparable to real-time, quantitative PCR was developed (Atarashi et al., 2007).

___________________

4 This sentence was revised after release of the report to note that ELISA is considered to have equivalent sensitivity to IHC.

Although they have been widely used experimentally, in some cases undergoing extensive validation, neither has yet been approved for use in regulatory or conventional diagnostic settings. Their potential utility in disease scoring approaches has not yet been explored. A summary of these tests, including their advantages and disadvantages, is found in Table 4.3.

The PMCA assay involves the cyclical conversion of PrPC, typically derived from transgenic (genetically modified) mouse brain PrPSc. This process results in new protein strands that are then fragmented and promote further conversion from normal to abnormal prion protein (Morales et al., 2012; Soto, Saborio, and Anderes, 2002). As such, PMCA is a highly sensitive assay, as it can amplify the equivalent of a single molecule of PrPSc (Saá, Castilla, and Soto, 2006), and it is well suited to detect prion infection in early, preclinical stages of disease. PMCA has been used for the detection of prions in different sample types, including biological (Castilla, Saá, and Soto, 2005; Chen et al., 2010; Gonzalez-Romero et al., 2008; Haley et al., 2012; Park et al., 2018; Saá, Castilla, and Soto, 2006) and environmental samples (Nagaoka et al., 2010; Ness et al., 2022; Nichols et al., 2009). Relevant to CWD, PMCA has shown the potential for evaluating large numbers of samples and may be superior to both IHC and ELISA for screening RPLN samples (Benavente et al., 2023), although these findings were not confirmed through secondary testing (e.g., mouse bioassay or interlaboratory validation). PMCA has also been used to detect prions in unearthed deer carcasses (Soto et al., 2023d) and at sites where taxidermal processing of infected carcasses was suspected (Soto et al., 2023a). The advantages of PMCA include the amplification of infectious prions from a sample while maintaining strain characteristics and species specificity (Castilla, Saá, and Soto, 2005; Deleault et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010). Because of its dependence on WB as a read out, PMCA offers another advantage through the visualization of PrPSc, allowing for strain typing. Although newer methods using a simplified approach to WB known as “dot blotting” have been described (Benavente et al., 2023), PMCA can take 3-21 days for prion detection, requires both transgenic mice and specialized equipment, and results in an amplified infectious product (Atarashi et al., 2008; Morales et al., 2012).

Like PMCA, RT-QuIC is an in vitro amplification assay that depends on the seeded conversion of normal prion protein, in this case produced by bacteria (i.e., “recombinant” protein), to misfolded PrPSc. Amyloid formation is detected in real time with the insertion of a fluorescent molecule (thioflavin T) in the newly formed protein aggregates (Atarashi et al., 2008; Orrù et al., 2017). RT-QuIC is highly sensitive—capable of detecting approximately 1 femtogram (i.e., 10−15 grams), well below the dose necessary to induce an infection (see Chapter 2) of misfolded

TABLE 4.3 In Vitro Amplification Tests for CWD

| Assay | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| PMCA |

|

|

| RT-QuIC |

|

|

SOURCE: Committee generated.

PrPSc (Atarashi et al., 2011). RT-QuIC has greater sensitivity in the detection of CWD prions than immunoreactive diagnostic tests (i.e., IHC and ELISA), particularly in earlier stages of infection (Haley et al., 2020a; Henderson et al., 2020; Manne et al., 2017; McNulty et al., 2019; Picasso-Risso et al., 2022). Multiple reports suggest that both RT-QuIC and PMCA have similar detection limits when brain extracts from infected animals are used (Hoover et al., 2016; McNulty et al., 2019; Kramm et al., 2017). The advantages of RT-QuIC broadly include its short turnaround time, quantitative abilities, high-throughput potential, high degree of cross-laboratory correlation, and sensitivity using otherwise challenging biological and environmental samples (Table 4.3 and Haley et al., 2020a, 2020b; Burgener et al., 2022; Schwabenlander et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2024).

RT-QuIC, like PMCA, has the potential to provide strain discrimination, although it has not yet been used to differentiate CWD strains specifically (Masujin et al., 2016; Levavasseur et al., 2017; Orrù et al., 2015). A key advantage of RT-QuIC, separating it from both immunoreactive assays and PMCA, is that the procedure does not require an enzyme digestion step, thus allowing for the additional detection of protease-sensitive forms or strains of the CWD prion. The product of the assay is not infectious, which is an important feature in diagnostic settings. Like PMCA, RT-QuIC requires specialized laboratory equipment and trained personnel. Early research suggests a high level of diagnostic agreement between RT-QuIC and ELISA (99.5%) and IHC (99.7%) (Holz et al., 2022). Given that RT-QuIC presently is used almost exclusively in research settings, current protocols differ in specific amplification conditions, reaction thresholds for designating positive or negative results, and data analysis (Rowden et al., 2023). Moving RT-QuIC into a diagnostic realm requires standardization of the protocol for different tissues and sample types to ensure confidence in test performance, reproducibility, and repeatability. Appropriate training, use of standardized positive and negative controls, and the inclusion of multiple replicates for each test sample are important to decrease or eliminate the appearance of false positive or false negative results.

NEXT-GENERATION DETECTION ASSAYS

A new generation of diagnostic assays has emerged in response to the need for enhanced detection sensitivity in samples with ultra-low prion concentrations—especially in samples collected antemortem—and in response to the need for field-deployable assays for more rapid turnaround of test results. Newer enhancements to the RT-QuIC procedure, including the addition of magnetic beads (Denkers et al., 2016; Henderson et al., 2015b) and silica nanoparticles (Christenson et al., 2023), show promise for increasing detection sensitivity in antemortem sample types. These modifications leverage prion-binding characteristics to overcome assay interference by inhibitors and increase the efficiency of amyloid protein formation, thereby overcoming previous challenges in detection related to low prion concentrations in clinically accessible samples. Field-deployable assays, such as a microfluidic microelectromechanical biosensor, which utilize positive dielectrophoresis and monoclonal antibodies attached to electrodes in a microfluidic chamber to concentrate, trap, and detect prions, have also been developed as low-cost, sensitive diagnostic options (Muhsin et al., 2023). Early experiments demonstrate that this biosensor is 10 times more sensitive than ELISA at detecting PrPSc and does not require pretreatment with proteolytic enzymes to prevent cross-reaction with PrPC (Muhsin et al., 2023). MN-QuIC is also described as a field-deployable diagnostic option, which integrates QuIC methods for prion amplification with the binding characteristics of misfolded prions to gold nanoparticles for prion detection based on color change that can be visually identified or measured by light-absorbance (Christenson et al., 2022). This low-cost and portable option was recently tested in the field and found to have a sensitivity of 95.7% and specificity of 100%, although validation in larger cohorts and in other laboratories is still needed (Christenson et al., 2022).

While these new diagnostic assays show high analytical sensitivity for the detection of PrPSc (see the earlier discussion in this chapter of sensitivity and specificity for an explanation of analytical versus epidemiological sensitivity), further research (e.g., bioassay confirmation) is needed to appreciate whether these extremely low quantities of detected prion are always associated with disease development and transmission. Likewise, additional research is needed to validate these assays for their use in the detection and surveillance of CWD for regulatory purposes, including estimates of test sensitivity and specificity across species, genotypes, and stages of disease, as well as repeatability and reproducibility across laboratories (USDA APHIS, 2019).

POSTMORTEM VERSUS ANTEMORTEM TESTING

As noted above, current official CWD diagnostic protocols rely on conventional or standard methods of testing of tissues collected postmortem (ELISA, IHC), specifically the obex region of the brainstem and RPLN. With the caveat that these assays may not have perfect sensitivity, the utility of these approaches has been primarily to provide an estimate of disease prevalence at the farm, county/hunt unit, regional, or state levels, including the initial detection of disease incursion into new areas. There is limited official approval of these assays for antemortem testing—at least in part because the sensitivity of clinically accessible tissues available for antemortem testing is lower than that of those collected postmortem (Haley et al., 2016a; Thomsen et al., 2012). Provisionally, some agencies have begun using biopsies of RPLN, tonsil, or RAMALT to screen and monitor herds with known exposure histories5 (Monello et al., 2014). Research efforts to validate additional clinically accessible samples for antemortem CWD testing using amplification assays have been underway (see Appendix D); among them are RT-QuIC testing of ear pinna biopsy (Ferreira et al., 2021; Burgener et al., 2022). Box 4.2 describes hypothetical applications of this method for antemortem testing in combination with provisionally approved tissue testing (e.g., RAMALT and tonsil). While these early studies are promising, limited study numbers and small sample sizes justify further research on this front. Because such methodologies can involve the use of non-disposable sampling equipment (e.g., tonsil biopsy), which has the potential to become contaminated with infectious prions (Rutala and Weber, 2010; Secker, Hervé, and Keevil, 2011; Laurenson, Whyte, and Fox, 2001), and the introduction of minor oral lesions can facilitate CWD transmission (Denkers, Telling, and Hoover, 2011), more attention is needed related to the implementation of appropriate biosecurity practices when such techniques are employed.

As it has for other notifiable diseases like tuberculosis and brucellosis, antemortem testing could in theory be used prior to the transport of captive cervids, recognizing that some animals in earlier stages of infection may go undetected. Past studies focused on antemortem testing have also examined the role of test and cull strategies in lowering disease prevalence in free-ranging and semi-free-ranging cervids, with mixed success (Haley et al., 2020a; Wolfe et al., 2018). The utility of antemortem testing, therefore, has primarily been applied to herd-level screening where concerns regarding imperfect test sensitivity may be balanced by high testing rates and not individual animal disease status determination. However, even with these recognized limitations, antemortem testing and surveillance—particularly in the management of CWD in captive herds—are recognized as critical to enhancing CWD control, monitoring the effectiveness of prevention in reducing the risk of CWD spread through animal movement, improving animal welfare, and reducing the economic impacts of CWD on herd owners (Henderson et al., 2013; Boden et al., 2010; Burgener et al., 2022). Despite advantages, antemortem testing use is not expected to supplant ongoing postmortem surveillance or confirmatory testing through the USDA CWD Herd Certification Program (HCP).

EARLY PHASE AND PRECLINICAL FALSE NEGATIVES

Key aspects of CWD pathogenesis likely affect the ability to detect misfolded prions in samples collected either ante- or postmortem and may influence detection through both conventional diagnostic approaches as well as experimental amplification assays. Importantly, the slow accumulation of prions in brain and peripheral tissues and fluids limits test utility to tissues with a sufficient prion burden at that stage of disease. This is highlighted by the absence of detectable prions, through IHC and ELISA, in postmortem obex collections from white-tailed deer in very early stages of disease—in these cases, prions may only be identified in RPLN tissues. The phenomenon may also be seen through the reduced sensitivity of both RAMALT and nasal brushings in earlier disease stages. Although past investigations suggest that experimental amplification assays may improve sensitivity in these cases (Haley et al., 2020a; Haley et al., 2016a), there will inevitably be periods of early infection where prion burden remains below the threshold of detection (Henderson et al., 2020). Future studies may highlight additional tissues (e.g., gut-associated lymphoid tissue [GALT] or enteric nervous system components) involved in the initial stages of pathogenesis, which may enhance test sensitivity in earlier disease stages.

___________________

5 See https://www.tahc.texas.gov/animal_health/elk-deer/PDF/TAHCCertifiedCWDPostmortemSampleCollectionRecertification.pdf (accessed July 25, 2024).

Either alone or in concert with disease progression, test sensitivity may also be reduced in animals with less-susceptible PRNP alleles. Antemortem testing sensitivity, using RAMALT for example, is reduced in deer and elk carrying the 96S or 132L alleles, respectively (Haley et al., 2016a; Haley et al., 2016b; Thomsen et al., 2012). This may be because animals with these alleles are generally in earlier stages of disease than those with wild-type 96G or 132M alleles (Haley et al., 2016a; Haley et al., 2016b). It remains to be shown whether PRNP genotype modulates test sensitivity in the field and whether amplification assays may likewise suffer from this potential limitation.

BIASES IN SAMPLING AND TESTING

Limitations in sampling strategy, diagnostic test methodology, and implementation in CWD surveillance can introduce bias and impact understanding of the epidemiology of CWD (see Box 4.3 for some logistical issues associated with postmortem sampling). For example, postmortem surveillance for CWD utilizing the detection of

PrPSc in RPLN has become a standard of practice for many state-level hunter-based surveillance programs because of its sensitivity for early detection in subclinical cases. However, this sampling strategy would likely misdiagnose CWD phenotypes where PrPSc is unlikely to be present in peripheral lymphoid tissues (see Chapter 2; Benestad et al., 2008; Güere et al., 2022). Thus, paired sampling of the obex to distinguish these sporadic phenotypes from the contagious lymphatic phenotypes of CWD is critical to understanding the epidemiology and risk among captive herds as well as in new geographic areas where CWD has been detected in free-ranging populations. However, even among prion strains typically found across North America, the stage of disease (or time since infection) and genetics (that influence progression of disease) can influence prion detection by the well-accepted assays (described earlier in this chapter). Furthermore, CWD pathogenesis in deer and elk is distinct: in deer, PrPSc accumulation occurs earlier in the RPLN than the obex; but in elk, PrPSc accumulation in the obex may occur earlier. Given these species variations, routine sampling and testing of RPLN only could introduce bias when it comes to CWD surveillance among elk, where individuals in earlier stages of disease would likely be under detected. When it comes to testing, the use of protease or acid treatments in some assays to eliminate PrPC would also result in the removal of CWD strains less resistant to protease digestion (Gambetti et al., 2008; Head et al., 2009; Benestad et al., 2003; Orge et al., 2004; Klingeborn et al., 2006; Duque Velásquez et al., 2020). Thus, any cases caused by protease-sensitive strains of CWD would be missed by the routine use of IHC and ELISA in surveillance.

LIMITATIONS AND PROMISING DIRECTIONS IN EARLY CWD PRION DETECTION AND CONTROL

Most CWD testing is conducted with ELISA or IHC methods in 32 NAHLN laboratories6 to screen tissues collected postmortem. The recent advances in prion amplification assays (e.g., PMCA, RT-QuIC) prompt the questions of whether the findings of small-scale studies of assay validation (see Appendix D) truly reflect enhanced sensitivities and, ultimately, whether they may be used by NAHLN laboratories. Conclusively answering questions regarding these issues requires either (1) inter-assay comparisons that rely on a commonly accepted reference standard (e.g., mouse bioassay, which may overlook true positive cases that are either very early in the preclinical stages or where prion burden is below the level of detection), or (2) longitudinal studies using antemortem sampling and eventual postmortem confirmation using conventional testing methods. In the first case, the resources currently required for bioassay confirmation of samples evaluated by both conventional and amplification assays make this approach impractical, at least on the scale necessary to permit reevaluation of the current acceptance of ELISA and IHC as diagnostic reference standards. Small-scale studies have successfully employed bioassay confirmation of infection where postmortem testing has resulted in IHC-negative, PMCA-positive white-tailed deer cases (Haley et al., 2009a). In the second case, the lack of regulatory approval or validation of any antemortem testing approaches in cervids makes longitudinal, live-animal testing approaches problematic. A 3-year longitudinal study in elk, however, found that animals with IHC-negative, RT-QuIC-positive RAMALT biopsies would eventually become IHC-positive either ante- or postmortem, or would be lost to follow-up in the field and presumed dead. Improvements in sensitivity provided by amplification techniques in this case were estimated to be 30% or more over IHC (Haley et al., 2020a). An adjunct approach to these two scenarios is the employment of statistical methods that integrate the uncertainty resulting from the absence of a true gold standard (see Box 4.1) of comparison (Picasso-Risso et al., 2022; Wyckoff et al., 2015). This approach recognizes the inherent imperfection of all diagnostic assays in the discrimination of true disease status (i.e., infection) and, rather than ignoring those limitations, incorporates our current understanding of those limitations into the estimation of more accurate measures of test performance. Although presently available data highly suggest that amplification assays do afford improved sensitivity over conventional approaches, broader studies in the future that incorporate bioassay as a reference standard may provide irrefutable data on the true sensitivity and specificity of both conventional and amplification assays.

A major limitation to the use of antemortem testing in captive herd management is the relative lack of official USDA antemortem sampling and testing as part of the HCP, although some states have implemented their own antemortem testing protocols. Currently, the USDA APHIS only approves the testing of RAMALT or RPLN biopsies by IHC under certain conditions for the antemortem detection of CWD in captive white-tailed deer (i.e., not elk, mule deer, or other cervid species) (USDA APHIS-APHIS, 2019). These conditions are that (1) at least two whole herd serial tests are performed when RAMALT biopsies are screened; (2) a whole herd is tested (rather than an individual tested prior to movement); and (3) the genotype at codon 96 must be known for all individuals in the herd, and more than 50% of the herd must have the 96G/96G genotype (USDA APHIS, 2019). Importantly, this antemortem testing strategy may only be applied in cases where a herd has been identified as CWD-exposed (i.e., through trace-back) or otherwise epidemiologically linked to a CWD-positive herd. The application is not approved for use in routine surveillance.

The requirements described above result in limitations that need to be overcome to manage CWD more effectively. First, because of the natural pathogenesis of CWD in cervids (Henderson et al., 2020; Haley and Richt, 2017; see Chapter 2), the sensitivity of RAMALT, a more accessible tissue sample than RPLN biopsy, is comparably lower (estimated 70-85% sensitivity; e.g., Haley et al., 2016a; Haley et al., 2016b; Tewari et al., 2022). Secondly, the identification of PrPCWD in tonsils, which are more accessible than RPLN, while also requiring specialized, single-use equipment to avoid iatrogenic transmission (see previous section on Postmortem versus Antemortem

___________________

6 See https://www.aphis.usda.gov/labs/nahln/approved-labs/cwd (accessed August 24, 2024).

Testing), allows for earlier identification of CWD in white-tailed deer (Henderson et al., 2020) than RAMALT. Lastly, prion detection by amplification assays like RT-QuIC and PMCA has been shown to improve upon the sensitivity of IHC (Benavente et al., 2023; Haley et al., 2020a), leading to earlier detection capabilities in some cases (Henderson et al., 2020). USDA APHIS has initiated efforts to validate RT-QuIC as an official antemortem test of RAMALT and RPLN, but progress toward validation and approval is uncertain. Assuming that appropriate biosecurity methods are adopted and employed to prevent iatrogenic transmission during sampling, these alternative sampling approaches may provide avenues for validation studies to enhance herd surveillance. Furthermore, because the HCP conditions for antemortem testing restrict its use in routine surveillance, there is limited opportunity to utilize antemortem surveillance for early detection and control (e.g., premovement), resulting in the potential for missed management opportunities.

As new antemortem diagnostic testing capabilities emerge, efficient epidemiological validation of sampling and testing of cervids is needed. Cooperation between USDA APHIS and the research community is critical such that requisite study designs for official test validation can be implemented early and by more research teams. This would involve transparency related to the criteria required for official test validation, collaboration, and communication between those reviewing and approving protocol validation data for official purposes and researchers developing these new technologies. Test validation and assessment of performance is an ongoing process, which needs to continue even after approval and implementation. Early validation studies cannot encompass and assess test performance under all conditions that characterize the natural settings in which they will be used. The impact of repeated sampling and tissue regeneration (e.g., RAMALT, tonsil, and ear biopsy; Geremia et al., 2015; Monello et al., 2014) on prion detection also needs to be evaluated in ongoing studies. However, longitudinal studies that support such validation efforts are difficult to perform given timelines of current funding mechanisms (e.g., through the CWD Cooperative Agreement Funding Opportunities through USDA APHIS; USDA APHIS, 2024). Strategies for implementing antemortem testing into routine surveillance for early CWD prion detection would benefit ongoing research efforts into diagnostic test assessment, validation, and robustness. Knowledge could be advanced with the recognition that all tests are imperfect (Dohoo, Martin, and Stryhn, 2014; see Appendix D and Box 4.4), that uncertainty and animal welfare are integrated into response plans, and that interested parties (e.g., herd owners, hunters) could be enlisted to enhance opportunities for sample and data collection.

SURVEILLANCE

Surveillance has been foundational in attempts to detect and contain CWD in the United States and elsewhere (Miller et al., 2000; Samuel et al., 2003; Kahn et al., 2004; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023; Thompson et al., 2023). The general principles of sampling (e.g., Cannon et al., 1982) as applied to CWD surveillance have been described in detail and periodically refined (e.g., Samuel et al., 2003; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023). The few reported examples of apparent containment of CWD in the wild have been associated with outbreaks detected at very early stages, emphasizing the value of surveillance to control efforts (Fischer and Dunfee, 2022). Unfortunately, the effort required to detect foci where CWD has been newly introduced—especially in the wild—may be considerably greater than that required to monitor changes and trends after foci have been detected (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023). Yet from the data reported, it is evident that sampling efforts in many jurisdictions expanded only after CWD had been epidemiologically traced to or detected within or near the jurisdiction’s boundaries, thereby delaying management responses and distorting the true timeline of CWD emergence across the United States (e.g., Thompson et al., 2023; Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024; also see Chapter 5).

Detecting CWD in captive cervid facilities can be relatively straightforward from a technical standpoint but is inconsistently applied (e.g., some states require captive facilities to participate in CWD surveillance; others do not). Because CWD-infected cervids do not recover and are expected to die, screening appropriate postmortem tissue samples (e.g., RPLN ± brainstem at the obex) collected from all cervids that die of any cause in a facility using any of the approved diagnostic tests yields a high probability (greater than or equal to 0.95) of detecting infected cervids, although this approach risks disease establishment during expected incubation periods that may extend to several years after infection (e.g., O’Rourke et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2012). Compromises in the completeness of mortality screening (e.g., capping the number of submissions in the face of a natural disaster or hemorrhagic disease outbreak, allowing for some number of “missed” death losses, or exempting young cervids) may erode detection probability to varying degrees. Surveillance approaches emphasizing high-risk cervids including “fallen stock” (i.e., unexplained illnesses and deaths), natural mortalities, and cervids showing signs of clinical disease suggestive of CWD also offer a high probability of eventual detection (Miller, Wild, and Williams, 1998; Samuel et al., 2003; Walsh, 2012; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2018, 2023) but may miss some individuals in early stages of disease that die but are not considered high-risk (e.g., apparently healthy cervids that are slaughtered or hunted). Whole-herd testing of live cervids has been proposed and occasionally used as an adjunct to mortality-based screening (Texas Animal Health Commission, 2022; M.W. Miller, personal communication, April 26, 2024).

Similar CWD surveillance principles outlined for captive cervids could apply to free-ranging cervids. However, application is considerably more difficult because cervids in the wild range over relatively large areas, and their illnesses and deaths are not observable to the same degree as captive conspecifics (i.e., cervids belonging to the same species). Captive cervids residing in enclosures with features that resemble wildland habitats may present similar challenges for surveillance (e.g., Haley et al., 2020a). Comprehensive screening of all mortalities is rarely feasible in the wild. Instead, surveillance for CWD in free-ranging populations relies on screening a sufficient number of samples to assure a high probability of detecting at least one case given a target prevalence (proportion of infected cervids in the population of interest). Screening of hunter-killed, road-killed, found dead, and “high-risk” cervids in various combinations has been used in efforts to detect CWD foci in the wild since the 1980s (Williams and Young, 1992; Samuel et al., 2003; Walsh, 2012; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2018, 2023). Weighting approaches (e.g., Walsh and Miller, 2010; Walsh, 2012; Jennelle et al., 2018; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023) have been developed to allow use of samples from various combinations of risk and demographic classes in designing CWD surveys and interpreting their results. Weighting samples according to evidenced-based risks of detection (Jennelle et al., 2018; Walsh and Miller, 2010) leverages inherent bias that may occur when testing samples from different deer demographics or sources of mortality, reducing the total number of samples needed to achieve the same detection probability as that needed for randomized sampling.

Data and experience have demonstrated that subdividing large geographic areas (e.g., a state, in the context of this report) into biologically or administratively defined “primary sampling units” will improve the sensitivity and timeliness of detecting emergent CWD foci in the wild (Samuel et al., 2003; Diefenbach, Rosenberry, and

Boyd, 2004; Joly et al., 2009; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2018, 2023; Fischer and Dunfee, 2022). Risk-based assessments (e.g., Russell et al., 2015; Fischer and Dunfee, 2022) may help prioritize the geographic areas of greatest potential importance in statewide surveys, but a systematic surveillance approach ultimately may be needed given the difficulty in obtaining a comprehensive understanding of all potential sources of introduction risk (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023). Combining data from different risk groups and accumulating the needed number of samples over several consecutive years can improve the practicability of CWD surveillance in large jurisdictions or other circumstances where sampling opportunities are limited (e.g., Jennelle et al., 2018; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023).

Recommended CWD surveillance approaches are well established (e.g., Joly et al., 2009; Samuel et al., 2003; Walsh and Miller, 2010). Key considerations include the sample size targets needed to detect outbreaks at relatively low apparent prevalence (e.g., 1% or less), the appropriate subdivision of large jurisdictions into smaller sampling units so outbreaks are still relatively localized at the time of detection, and temporal considerations needed to assure meaningful inferences can be made from the resulting data (Joly et al., 2009; Samuel et al., 2003; Diefenbach, Rosenberry, and Boyd, 2004; Walsh and Miller, 2010). The recent EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards and others (2023) includes a detailed overview and surveillance “toolkit.” Other detailed reviews of approaches and recommendations for detecting CWD in free-ranging cervids, literature citations, and examples of successful implementation are available (e.g., EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2018, 2023; Fischer and Dunfee, 2022). Nonetheless, individual jurisdictions face a variety of limitations in execution of those approaches (Fischer and Dunfee, 2022; Thompson et al., 2023), and consequently the inferences regarding CWD occurrence that can be gained from surveillance have varied widely over time and among jurisdictions (e.g., Thompson et al., 2023; Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024). See Chapter 6 for further discussion of surveillance in the context of disease prevention and control.

Assessing and Interpreting Surveillance Findings

Surveillance is conducted to inform CWD response and management by state, tribal, and federal agencies. Depending on the current state of CWD in a location (e.g., presumed absent, early introduction, high prevalence), surveillance goals and therefore methodologies may vary (see Chapter 6). Accordingly, there are several criteria by which surveillance systems might be assessed, including their sensitivity of case detection at specified levels of disease in a population (i.e., detection probability given an assumed prevalence value), specificity of detection (i.e., estimated potential for false alarms), cost-effectiveness, and long-term sustainability in meeting agency goals. Ultimately, the veracity of reported “disease absence” (Box 4.5) and inferences about the timing of CWD introduction or emergence based on a “first detection” depend heavily on surveillance design (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023; Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024; also see Chapter 5). As discussed in the previous section, the number of cervids tested (sample size) and the size of the primary sampling or survey unit (i.e., the geographic area associated with the cervid population being sampled) together can influence the survey’s sensitivity (i.e., the probability of detecting one or more cases in a population given an assumed prevalence value) with respect to early CWD detection in a population (Samuel et al., 2003; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023).

Surveillance of Free-Ranging Herds

Detecting CWD outbreaks in free-ranging cervids at an early stage is desirable from a control standpoint (see Chapter 6, “Approaches for Controlling CWD in Free-Ranging Cervid Populations”) but is extremely difficult to achieve even with today’s understanding and tools because early in an outbreak the number of cases and the size of the affected area are small (e.g., less than 10 infected cervids within less than 10 square miles) (Joly et al., 2009; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023). Surveys for CWD are typically designed to detect at least one case in a herd or population with 95% or 99% percent confidence where apparent infection prevalence (proportion of the number sampled testing positive) is greater than or equal to 1% (e.g., Samuel et al., 2003; Joly et al., 2009; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023). Achieving this high likelihood of detection requires screening approximately 300-500 harvested cervids from a herd or population of greater than or equal to 1,000 individuals (Cannon et al., 1982). However, inferences about negative outcomes of surveillance are constrained by the survey design. For example, finding

no cases among 300-500 samples collected from hunter-harvested cervids across an entire state provides reasonable certainty that CWD prevalence in the state’s entire cervid population of perhaps 1 million or more individuals is no higher than 1% (1 in 100) (Cannon et al., 1982; Samuel et al., 2003; Diefenbach, Rosenberry, and Boyd, 2004; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023), but the finding offers little assurance that CWD is not present at lower statewide levels or in a more limited geographic distribution, as commonly encountered in the first several decades after its introduction (e.g., Joly et al., 2009; see below and Chapter 5 for further discussion). Diefenbach, Rosenberry, and Boyd (2004) illustrated an early application of these principles in considering approaches for statewide surveillance in Pennsylvania preceding CWD detection.

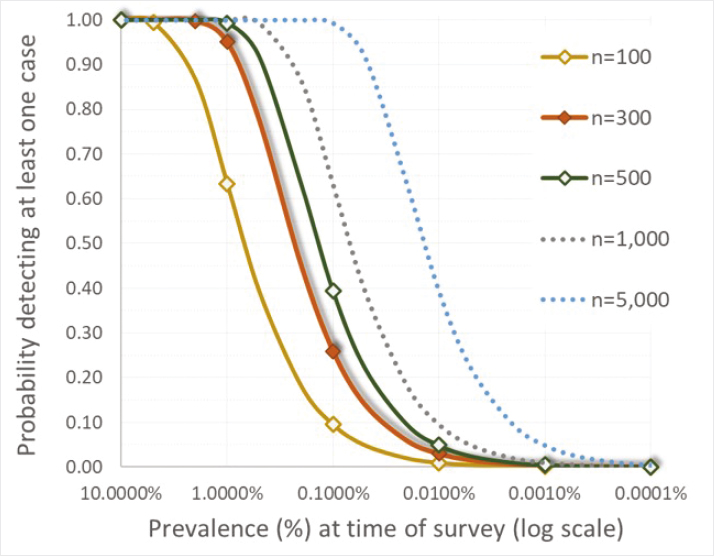

Of note in the context of control, CWD outbreaks that have reached the levels of prevalence routinely targeted for detection at the geographic scales upon which surveys have been based may be well established, thereby complicating prospects for effective control. For example, in a local population of approximately 10,000 cervids (e.g., occupying a county-sized area in a midwestern state), prevalence at greater than or equal to 1% would equate to already having 100 or more infected cervids present at the time of first detection; in a population with approximately 1,000,000 cervids (e.g., the population occupying an entire state), this could equate to having approximately 10,000 or more infected cervids present at the time of first detection. Detecting outbreaks at a lower prevalence (e.g., 1 in 1,000 or 0.1%) with equal confidence requires larger sample sizes (Figure 4.1; Cannon et al., 1982; Diefenbach, Rosenberry, and Boyd, 2004). For this reason, screening a few hundred samples across an entire state has at times failed to detect substantial but geographically localized CWD outbreaks (Joly et al., 2003; Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024). Surveys based on geographic areas the size of an entire state or larger have yielded misinformed assessments of CWD distribution and “absence” historically (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2018; Ruder, Fischer, and Miller, 2024; also see Box 4.5 and Chapter 5). It is for this reason that contemporary

SOURCES: Cannon et al., 1982; Joly et al., 2009.

recommendations for designing CWD surveillance include subdividing large geographic areas (e.g., an entire state) into spatial subunits (“primary sample units”) more equivalent in size to a wildlife management unit or county in order to assure reliable inferences can be drawn (Samuel et al., 2003; Diefenbach, Rosenberry, and Boyd, 2004; Joly et al., 2009; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023).

Given current sample testing regimes, which rely on highly specific tests (ELISA or IHC with greater than 99% specificity; see Appendix D for more detail on test performance) for CWD detection, it is unlikely that existing surveillance systems would experience false positive results (i.e., diagnosis of CWD in an uninfected animal). However, there are recognized biases in sampling design that could impact accuracy of the prevalence estimation. For instance, Conner and others (2000) demonstrated temporal trends in CWD prevalence across a harvest season, where a greater number of CWD cases were detected later in the harvest season. Thus, by estimating prevalence across all fall hunting seasons within the year (versus a single harvest season sample), these researchers were able to obtain a more accurate and unbiased CWD prevalence estimate. Differences in CWD risk across demographics can also bias prevalence estimates if sampling is not random and some demographics are under- or over-represented in a sample as compared to their distribution in the population. As noted in the previous section, however, demographic differences in risk can also be leveraged to maximize CWD detection while reducing constraints on resources (Walsh and Miller, 2010; Jennelle et al., 2018). Similarly, it is important to be aware of potential spatial bias in harvest-based surveillance practices, considering both the nonrandom distribution of deer harvest by hunters as well as the nonrandom distribution of CWD-infected individuals across a landscape (Samuel et al., 2003; Diefenbach, Rosenberry, and Boyd, 2004; Farnsworth et al., 2006; Osnas et al., 2009). Finally, recognizing how sampling of vehicle-killed or hunter-harvested deer can over- or underestimate detection probabilities or prevalence estimates is also critical (Nusser et al., 2008).

Agencies conducting CWD surveillance are challenged by the investment of resources needed for ongoing, active CWD surveillance (see Chapter 7). Because CWD surveillance is a resource-intensive and seemingly perpetual endeavor, agencies need to weigh surveillance goals and the choice of sampling framework and sample size with the costs of the program. Most states and many tribes conduct some level of CWD surveillance or monitoring each year through voluntary sample submissions from hunters; fewer require hunters to submit samples from cervids harvested in specific locations or years (e.g., annually or on a rotation) to increase sample sizes and improve data precision.7 Fischer and Dunfee (2022) provide several detailed examples of how state agencies have adapted their surveillance approaches based on changes in CWD epidemiology as well as the need for cost efficiency. An example of a network of midwestern tribal natural resource agencies coordinating CWD surveillance activities across tribal lands is described in Chapter 6.

Surveillance of Captive Herds

Surveillance among captive herds has been led by the USDA HCP at the federal level and various state agencies (e.g., departments of agriculture, natural resource agencies, animal health boards) at the state level. However, implementation of captive herd surveillance through the HCP is inconsistent across states that permit captive cervid possession because it rests on voluntary participation by both states and captive herd owners (see further details in Chapter 6). At the time of writing this report, 28 states had approved HCPs (USDA, 2018). Also, because the federal program focuses surveillance efforts on the interstate movement of cervids, herds that only move cervids within a state may be missed by the federal surveillance program unless state agencies mandate broader participation in some form of herd certification or monitoring. Examining data from states where CWD monitoring has been a requirement of herd ownership may help determine the extent to which such surveillance has been effective in earlier CWD detection (as demonstrated by lower herd prevalence levels at time of detection) and reduced occurrence of multi-herd outbreaks related to captive cervid movements.

EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS—NEW HORIZONS IN SURVEILLANCE

Much surveillance is conducted among free-ranging cervids through sampling and testing of hunter-harvested or vehicle-killed animals or testing of unhealthy cervids that may be found dead or euthanized. In the captive cervid industry, participation in surveillance is voluntary in some states through participation in the USDA HCP; in other states participation in mortality-based CWD surveillance is a condition of cervid ownership.8 There is currently no pre-diagnostic (e.g., syndromic or environmental) surveillance program for either captive or free-ranging cervid herds and populations. However, new surveillance technologies for the detection of prions in the environment or on contaminated surfaces (e.g., feeders; Yuan et al., 2022; Soto et al., 2023d; Huang et al., 2024) are being researched and may offer new opportunities for noninvasive early detection. For example, research is emerging to evaluate the efficacy of detecting CWD prions in environmental samples collected from white-tailed deer scrape sites. These are locations on the landscape where deer scrape away leaves and debris to expose bare soil and where they interact with overhanging branches for communication via scent marking; they can be visited and used by many deer during a breeding season (Egan et al., 2023). Preliminary results demonstrate that PrPSc can be detected by RT-QuIC from soil and tree branch samples from scrape sites (Huang et al., 2024), offering another option for surveillance of CWD (Lichtenberg et al., 2023). Another early-detection approach being evaluated is the use of environmental swab sentinels for the detection of CWD prions at feed troughs and other surfaces on captive cervid facilities using RT-QuIC (Yuan et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2024) or PMCA (Soto et al., 2023d). These methods leverage the binding capacity of PrPSc to certain surfaces and the ability to extract these environmental prion proteins using swabbing technology (Yuan et al., 2022) for detection. Early findings demonstrate that the number of RT-QuIC-positive swabs in a herd pen correlates with CWD pen prevalence as

___________________

7 See https://cwd-info.org/cwd-hunting-regulations-map/ (accessed May 7, 2024).

8 See https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/managing-resources/wildlife/wildlife-disease/disease-monitoring/cwd/cwd-hunting-regulations/cwd-and-cervidae-regulations-in-north-america (accessed July 25, 2024).

determined by IHC (Schwabenlander et al., 2023). The detection of prions in the environment using these methods has also been investigated for surveillance for environmental prion proteins at bait sites used during culling activities of free-ranging deer. Further work is needed, however, to determine how frequency of environmental prion detection on swabs or load in RT-QuIC correlates with the number of CWD-positive deer visiting bait sites (Schwabenlander et al., 2023). Collectively, these unpublished preliminary findings show promise for their application to enhance surveillance for CWD detection in a way that does not compromise animal welfare. Leveraging the capabilities of PMCA and RT-QuIC in pre-diagnostic sample testing and integrating these approaches with existing surveillance systems to confirm early CWD signals could provide a robust and powerful system for CWD detection, for informing management, and for ongoing studies into the ecology and epidemiology of CWD and its control on and off farm.