State of Knowledge Regarding Transmission, Spread, and Management of Chronic Wasting Disease in U.S. Captive and Free-Ranging Cervid Populations (2025)

Chapter: 6 Effectiveness of Interventions to Control or Reduce the Transmission and Spread of CWD in Captive and Free-Ranging Cervids

6

Effectiveness of Interventions to Control or Reduce the Transmission and Spread of CWD in Captive and Free-Ranging Cervids

___________________

1 See https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cervid/chronic-wasting/herd-certification (accessed October 24, 2024).

As described earlier in this report, CWD was recognized as an animal health problem in affected captive cervid facilities even before its etiology and infectious nature were appreciated (Williams and Young, 1980; Williams and Young, 1992). Attempts to contain and control CWD in captive cervids herds date back to the 1980s, with limited effectiveness (Williams and Young, 1992; Miller, Wild, and Williams, 1998; Dubé et al., 2006). Underestimating prion contamination and persistence in the environment and the unavailability of antemortem diagnostic tools were arguably the two main impediments. Since the late 1990s, the recognition that CWD was more widely distributed in captive and free-ranging cervids has compelled broader and more organized investigation, surveillance, control, and containment efforts (reviewed by Williams et al., 2002; Uehlinger et al., 2016; Thompson et al., 2023; Chronic Wasting Disease Task Force, 2002). The nature of the CWD prion and insidiousness of resulting clinical disease; its slow epidemic dynamics; its presence in both free-ranging and captive host populations; and, importantly, its ability to contaminate and persist in the environment for extended periods present formidable challenges to containing and controlling CWD and to assessing the efficacy of such efforts.

This chapter briefly overviews principles of disease management in domestic and wild animals; summarizes the accessible knowledge about approaches for controlling other transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), the control of CWD, and the apparent effects of control interventions in captive and free-ranging settings; and identifies gaps and limitations in knowledge about CWD control and how those might be remedied moving forward. The committee stresses its reliance on “accessible” knowledge for this summary, knowing there are additional research and data that could inform more broadly if they were made available (e.g., through public databases or reports or via publication in the scientific literature).

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF DISEASE MANAGEMENT IN DOMESTIC AND WILD ANIMALS

Despite the challenges associated with managing CWD, the well-established “rationale, strategies, and concepts of animal disease control” (e.g., Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987) generally apply. Although CWD has some unique characteristics regarding transmission and spread, it generally adheres to the same epidemiological principles as other infectious diseases. The traditional epidemiologic triad model holds that infectious diseases result from the interactions among an agent, a host, and the environment. Transmission occurs when the agent (prion) leaves the host/reservoir (CWD-infected cervids) through a portal of exit, is conveyed by some mode of transmission (direct or indirect), and enters through a portal of entry (e.g., oral) to infect a susceptible host. This sequence is referred to as the chain of infection. The components of the chain regarding CWD have been described in previous chapters. All known infectious diseases—regardless of whether the agent is a virus, a bacterium, a fungus, a parasite, or a prion, or whether the disease involves humans or animals—can be described and explained by this foundational principle (Dicker, 1992).

It follows that knowledge about the portals of exit and entry and the mode of transmission provide a basis for determining appropriate control measures (e.g., Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987; Dicker, 1992; Wobeser, 2007). In general, control measures are usually directed against the segment of the infection chain that is most susceptible to intervention. Efforts to manage diseases in domestic or wild animals are motivated by anthropocentric concerns about the consequences—absent management—for humans and/or animals they care about (Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987; Wobeser, 2007). Several considerations thus underlie animal disease management (Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987; Wobeser, 2007; Stephen, 2022a). As summarized by Wobeser (2007) in the context of attempts to manage a wildlife disease, these considerations include desirability, feasibility, beneficiaries, costs and benefits, availability and viability of approaches or tools, objectives and extent, and measures of “success.”

The objectives for disease management fall under three broad concepts (e.g., Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987; Wobeser, 2007): prevention (i.e., invoking measures to exclude or prevent the introduction of the disease agent of concern), control (i.e., invoking measures to reduce the frequency of an existing disease to levels that are biologically or economically justifiable or tolerable), and eradication (i.e., invoking measures to eliminate the disease agent of concern from a defined geographic area, which may be local, national, or global). Of these, eradication requires the most extreme measures in applications to either domestic or wild animal populations (Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987; Wobeser, 2007). In the context of CWD, it seems noteworthy to consider that the features of potentially eradicable infectious diseases—per Yekutiel’s (1980) critique on the subject—include having detrimental effects sufficient to justify the economic impacts, relative ease of case detection and surveillance, and the availability of at least one effective tool for breaking transmission. The pursuit of a disease eradication campaign also requires careful

consideration of the rationale for its preference over control; whether administrative, operational, and fiscal resources are adequate to support the entire undertaking; and the potential for direct or indirect adverse effects of such efforts (Yekutiel, 1980). As observed by Wobeser (2007, p. 195), choosing among the three basic objectives for disease management “depends upon many factors including the presence or absence of the disease in the area, the length of time the disease has been present, the frequency of occurrence and distribution of the disease, the species affected, the availability of suitable methods for detection, diagnosis and management, the desirability or need for management, and the ability to convince others of this need. Often an overall program may involve aspects of prevention, control and eradication, with different techniques being used at various stages of the program.”

As detailed in later sections of this chapter, the approaches that have been applied in attempts to manage CWD under one or more of the foregoing objectives are common to efforts directed at managing other animal diseases. Specific disease management activities (adapted from Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987) include

- lethal removals via means including slaughter (as well as culling and hunting), applied selectively or nonselectively at scales ranging from individuals to populations (i.e., “depopulation”);

- animal movement restrictions (sometimes termed “quarantine”) for infected/exposed individuals, populations, or regions;

- reduction of contact via physical barriers or other biosecurity measures;

- “chemical” applications (e.g., disinfectants, therapeutics);

- modifications of host resistance (e.g., via vaccines, genetic selection);

- environmental manipulations;

- biological control; and

- education (of humans).

These approaches have been (and are) used in various combinations in attempts to manage animal diseases (see examples and additional references in Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987; Haigh and Hudson, 1993; Wobeser, 2007; Gillin, 2022). Regardless of the approaches adopted, additional key features of attempts to manage disease in either domestic or wild animals include having sufficient time to affect change in the dynamics of the targeted disease agent, a means of assessing responses to intervention (e.g., changes in disease frequency or distribution over time), and the ability (and willingness) to modify or adapt approaches to evolve with changing circumstances (Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987; Wobeser, 2007; Gillin, 2022; Stephen, 2022a).

Several approaches for reducing transmission and spread of CWD have been identified and are reviewed in this chapter. These include restricting the movement of infected, potentially exposed, or untested cervids and cervid carcasses, and reducing or eliminating infected cervid herds and exposure opportunities (i.e., limiting the local abundance, sex-age composition, aggregation, and captive holding of cervids in places where CWD has become established) to help suppress transmission and further geographic spread. Management is underpinned by comprehensive surveillance and monitoring to reliably detect CWD cases and foci in captivity or in the wild during the early stages of an outbreak and to assess responses to control. Although the knowledge and tools to accomplish each of these have been available for some time, their implementation has thus far been limited because they are not practical on a sufficiently large scale, are not palatable to local (or broader) constituents who have a say in adopting policies and enacting management, or are not sustainable because support for them wanes over time (e.g., Holsman, Petchenik, and Cooney, 2010; Miller and Fischer, 2016; Uehlinger et al., 2016; Smolko et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2023). The actions envisioned as necessary and feasible from afar (e.g., from outside a jurisdiction or a local community) often do not enjoy the same level of acceptance in the places where such actions are to be implemented. Experience to date suggests top-down approaches for controlling CWD are less likely to be sustained or to succeed than approaches that have been developed and accepted more locally (Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, 2017).

CONTROL OF OTHER TRANSMISSIBLE SPONGIFORM ENCEPHALOPATHIES

It is tempting to look to how other TSEs, such as classical scrapie and classical bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), were controlled for guidance in the control of CWD, although differences in the epidemiology of each of these TSEs make extrapolation difficult (see Table 2.1). Control programs for scrapie and BSE have

seen many successes. The incidence of classical scrapie has been substantially reduced in the United States because of culling infected flocks and promoting selective breeding of resistant phenotypes. Classical BSE was controlled among cattle in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe through changes in animal feeding practices (Wilesmith et al., 1988; Wilesmith et al., 2000). However, scrapie control has been largely successful in the United States because of the design of a nationwide eradication program where all adult sheep and goats bought, sold, or otherwise moved between flocks and farms are officially identified for implementation of disease control strategies, including a nationwide slaughter surveillance program (USDA National Scrapie Surveillance Plan, 2022). Appendix E of this report provides details about the scrapie eradication program. The national program for CWD focuses on control, not eradication, and enrollment, participation, and surveillance are not consistently mandated (more detail provided in this chapter). Forward strides in scrapie control were also made because sheep and goats have strong genetic links in terms of susceptibility (Goldmann et al., 1994; Hunter, 1997; Baylis and Goldmann, 2004; Nodelijk et al., 2011). Although variations in the cervid PrP genotype confer differences in CWD progression, complete genetically based resistance to infection (and ongoing transmission) has not been observed in cervids.

BSE was controlled because the cause of transmission was identified (i.e., feed containing contaminated animal tissue and bone meal) and effectively eliminated (Wilesmith et al., 1988; Wilesmith et al., 2000). Whole-herd culling was also conducted, but, because there is no evidence of horizontal transmission of BSE between cattle, that intervention may not have been necessary if infected animals could be identified and removed from the human and animal food chains (Detwiler and Rubenstein, 2000). In contrast, CWD transmission among cervids is not limited to the consumption of animal protein but rather involves avenues of both direct (animal to animal) and indirect (environment to animal) transmission (more detail in Chapter 3); thus, CWD control necessitates a multimodal control strategy. BSE is zoonotic (unlike scrapie), which also dictates the control response. Finally, unlike scrapie and BSE, which are TSEs confined to captive livestock, the transmission of CWD among free-ranging cervid populations adds additional complexity. See Appendix E for more information about BSE control.

GAUGING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF CWD INTERVENTIONS

Drawing conclusions about the state of knowledge regarding CWD and the “effectiveness” of interventions to reduce transmission and spread of CWD—as the study committee is directed to do in its statement of task (see Box 1.2)—is not straightforward, particularly if effectiveness is considered at a national scale. As discussed in previous chapters, prion transmission cannot be measured directly in natural exposure settings. Moreover, the continuous and intensive monitoring that would be necessary to detect new cases over time (incidence) is not practicable on a broad scale in free-ranging settings or in some captive settings. Because CWD incidence strongly correlates with apparent prevalence (the proportion of a sample of animals that is infected; Miller and Wolfe, 2021), observed prevalence trends have been used to monitor epidemic dynamics in free-ranging cervids. Surveillance and monitoring are therefore integral to understanding the effects of management strategies for CWD control in the wild, as is true for assessing management of most wildlife diseases (Wobeser, 2007). The main laboratory tests used for CWD detection (e.g., immunohistochemistry [IHC] and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) are considered sufficiently reliable, have been available for over two decades, and were instrumental in controlling other animal TSEs (see Chapter 4 for descriptions, Appendix D for a summary of published diagnostic platforms, and Appendix E for further discussion of scrapie and BSE control programs). Similarly, the principles of CWD surveillance and monitoring are well established (see Chapter 4), although how surveillance and monitoring are conducted has varied over time and across jurisdictions (see Chapters 4 and 5). Reliably comparing CWD prevalence data over time and across jurisdictions requires consistency in data-gathering methods, thus presenting potential challenges to assessing the effect of interventions—or lack thereof—on epidemic trends. Additionally, accurate measurement of CWD’s geographic spread requires reasonable certainty about its spatial distribution over time (see Chapters 4 and 5). Measuring CWD’s population and economic effects and responses to interventions presents even more complex challenges (see Chapter 7). Because jurisdictions may design their surveillance and monitoring programs to meet different objectives, particular care may be required in comparing data derived from different jurisdictions when trying to understand CWD patterns and management responses at a national level.

Beyond the foregoing challenges, no common standards of acceptable response thresholds for CWD prevalence or related disease outcome metrics have been established by animal health and management authorities. Each sets its own disease management targets and approaches, as well as surveillance and monitoring schedules. This is not entirely surprising given that each management jurisdiction (i.e., fish and wildlife management or agricultural agency) operates under unique sets of circumstances based on CWD’s known distribution, prevalence, affected species, and cervid population and movement dynamics, as well as the political climate, legal constraints, and cultural expectations within a jurisdiction (Holsman, Petchenik, and Cooney, 2010; Miller and Wolfe, 2023; Thompson et al., 2023). Consequently, even where effects are measurable, the perceived effectiveness of control efforts directed toward CWD will tend to be situational and will likely be influenced by whether or not interested parties share common management goals.

As will be illustrated in the rest of this chapter, it is not only the management techniques for curbing CWD that merit further assessment and development but also the realistic goals for its control at small and large spatial scales. Effectiveness is relative and has been assessed in that context for this report.

APPROACHES FOR CONTROLLING CWD IN CAPTIVE CERVIDS

Organized investigation, surveillance, control, and containment efforts for CWD in captive cervids have been in place since the late 1990s, first in Canada and subsequently in the United States (USAHA, 1998; USAHA Committee on Wildlife Diseases, 2000; Chronic Wasting Disease Task Force, 2002; National CWD Plan Implementation Committee, 2002; Kahn et al., 2004). Possibly the most important component of CWD management is prevention, which is dependent on measures found across livestock farming and health management including reliable means of both herd and animal identification, current records of animal inventory and movement, appropriate biosecurity, and accurate disease surveillance. With the discovery of CWD on a property, these measures also afford a better understanding of disease epidemiology. Once the disease is discovered, management relies on herd-level quarantine, animal trace-outs, and in many cases depopulation, with further work done to characterize the extent of the outbreak and minimize its impacts on both captive and surrounding free-ranging cervid herds. Indemnity is provided where available to both compensate the herd owner and encourage disease reporting and subsequent control measures.

State-Federal Program to Address CWD Among Captive Cervid Populations

In 2003, the USDA APHIS Veterinary Services began development of what is now the CWD HCP (HCP2; USDA APHIS, 2019). This is a cooperative program involving the APHIS, state animal health and wildlife agencies, and captive cervid owners. The goal is to provide uniform methods to minimize the incidence and spread of the disease. The program is administered by states, with federal oversight to ensure appropriate biosecurity and accurate disease surveillance in application of the program throughout the states.3 Participation in the program is voluntary for both the state and producer; however, interstate movement is restricted to certified herds. The legal requirements for the HCP and interstate movement requirements are outlined in Title 9 of the Code of Federal Regulations parts 55 and 81. The HCP standards outline the minimum requirements to certify captive cervids for interstate movements. At this time, no tribal agencies or captive cervid facilities owned by tribes were known to be participating in this program, although it appears that there is nothing that would preclude their participation. Inclusion of tribal agencies or cervid facilities may necessitate some revision to state-federal program standards where states have no jurisdiction on tribal lands.

The HCP for captive cervids applies well-established principles for animal disease control (e.g., Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987; Wobeser, 2007) and mirrors other USDA-listed notifiable diseases, including bovine brucellosis,4 bovine tuberculosis (USDA APHIS, 2005), and highly pathogenic avian influenza (USDA APHIS, 2020) in several respects. The HCP’s core elements are common to programs enacted in Canada, the states of South

___________________

2 See www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/cervid/cervids-cwd/cervids-voluntary-hcp for links related to the program (accessed May 21, 2024).

3 This sentence was revised after release of the report to correct that there is no genetic requirement in the Herd Certification Program

4 See https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cattle/bovine-brucellosis (accessed August 6, 2024).

Dakota and Colorado, and elsewhere beginning in the late 1990s (USAHA Committee on Wildlife Diseases, 2000; USAHA, 2001; Kahn et al., 2004; Argue et al., 2007). The aforementioned prevention, detection, investigation, and response practices, enhanced by the federal HCP enacted in 2012, have generally aided in the early discovery and rapid containment of the disease on cervid farms across the United States. For herds not enrolled in the HCP, states may impose specific regulations that aim to limit the risk of herd-to-herd disease transmission within the state and quickly contain any cases identified. Some captive herds, for example those part of the Deer Protection Program, go beyond the requirements of the HCP to avoid prion contamination of their products (see Box 6.1 and Chapter 5).

Although not all cervid farms in all states in the United States are required to participate, the HCP has provided a foundation for CWD management practices for captive cervids at a national scale. The program provides requirements for herd enrollment in the program, including varying aspects of animal- and herd-level identification and inventories, biosecurity, and surveillance. Herd inventories and animal movement records, which must be consistently maintained to remain in the program, provide important data that assist trace-out investigations, where necessary. Interstate movement of captive cervids requires the herd has been certified in the HCP and is regulated by the USDA. The HCP provides some guidance on biosecurity, including recommendations for barriers to reduce contact with outside wildlife—in most cases, a single row of fencing at least 8 feet in height. Additional biosecurity measures—for example, a second row of fencing, farm-specific clothing, limitations on individuals with access to the farm, feed sourcing, and isolation areas for cervids showing signs of disease—are not currently discussed in the HCP and are not consistent practices across the cervid farming industry. Finally, the HCP requires consistent postmortem testing of all cervids, 12 months or older, that die. Accommodations may be made for missed tests on deceased (or escaped) cervids through “replacement” postmortem testing from comparable cervids in the herd, or a reduction or loss of herd certification status. Postmortem samples, collected by certified personnel, are submitted to one of the 32 approved National Animal Health Laboratory Network laboratories (NAHLN)5 across the country, with any positive cervids ultimately confirmed by the National Veterinary Services Laboratory (NVSL).

With the discovery of CWD within any captive herd, HCP-enrolled or otherwise, the herd is initially placed under state-authorized movement restrictions to limit the further spread of disease while investigations into animal movement on (“trace-ins”) and off (“trace-outs”) the farm are performed to identify source and destination herds of CWD-positive and potentially exposed cervids.6 Trace-in/trace-out facilities are likewise placed under quarantine, with similar restrictions on animal movement. Further investigations that focus on potential routes of CWD

___________________

5 See https://www.aphis.usda.gov/labs/nahln/approved-labs/cwd (accessed May 22, 2024).

6 A tutorial on animal disease traceability has been developed by the USDA and is available here: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/slowburn/story_html5.html (accessed August 26, 2024).

introduction may be performed. All facilities placed under quarantine have options that may include (1) complete depopulation and postmortem testing, (2) a 5-year continuance of the quarantine under the guidance of a mutually agreed upon herd plan, or (3) a live-animal testing protocol that considers the range of prion genotypes on the premises and the time since reported positive cases or exposure.7 Trace-in/trace-out facilities that hold potentially exposed cervids are given the option of killing and testing those cervids. Live-animal testing in conjunction with genetic analyses may be performed in some cases in white-tailed deer herds. Quarantined herds may be removed from quarantine if no additional positive cases are identified over a 5-year period, during which time their herd status is listed as “suspended.” Depopulated herds are provided with federal indemnity, when available, with costs of testing and disposal covered by the USDA. Indemnity is provided on a case-by-case basis, with preference given to herds enrolled in the HCP, among other factors.

Following depopulation, further guidance on proper disposal of carcasses, site decontamination, and continued biosecurity is provided under the HCP. Carcass disposal methods are determined prior to depopulation and include incineration, alkaline hydrolysis treatment, or disposal on-site or in an approved landfill. Each method has corresponding strengths and weaknesses with regard to cost and prion inactivation effectiveness. Site decontamination considers farm equipment and infrastructure (e.g., tractors, fencing, barns) as well as animal pastures, and may include approaches like chlorine treatment of exposed equipment and surfaces as well as soil removal or re-tilling. Finally, facilities under quarantine are required to maintain perimeter fencing and otherwise minimize the risk of further exposure to free-ranging cervids outside of the fence. Restocking with CWD-susceptible species is highly discouraged following depopulations, with further cases likely even after a period of perhaps 10 or more years based on data available for classical scrapie (Georgsson, Sigurdarson, and Brown, 2006; Hawkins et al., 2015).

Metrics for evaluating the effectiveness of programs like the HCP typically include considerations of the number of farms enrolling (or reenrolling) in the program each year, the number of positive cases or herds identified each year (for both enrolled/certified and non-enrolled herds), a cost-benefit analysis of the program and its potential impact on case reduction, and satisfaction polling of invested parties. Assessments of disease prevention programs consider data both prior to program initiation and throughout its deployment.8 Data on many aspects of the overall effectiveness of the HCP are either limited or were unavailable to the present study committee. As of December 2023, there were 28 states participating in the HCP. Although the total number of herds nationwide at that time is unknown, over 1,600 herds were enrolled and 85% of these herds were certified (T. Nichols, personal communication, June 20, 2024). The yearly frequency of CWD-positive HCP-certified herds has remained relatively constant at <1% since 2018 (T. Nichols, personal communication, March 12, 2024) (see Table 6.1). Also of note is the steady decline in the number of herds certified through the HCP over the past 5 years (Table 6.1), which may indicate some level of dissatisfaction with the program (S. Schafer, personal communication, December 14, 2023) or other factors. In addition to reporting instances of CWD among HCP-certified herds, the program works continuously with states to monitor and improve compliance.

Other metrics that could provide insights into the effectiveness of the HCP, where such data are available, include the number of captive herds in states that are not participating in the HCP; the timeliness of case identification and herd quarantine or depopulation, when applied; CWD prevalence at time of depopulation; as well as the number of farms traced out from a positive herd and their eventual outcomes. Estimates on the time between disease introduction and identification of a positive case (e.g., through correlation between genetic background and disease stage) and between initial detection and quarantine or depopulation could allow regulatory agencies to assess improvements in these metrics over time. Similarly, herd prevalence estimates at time of depopulation, after controlling for time since first detection, would offer further insights. A continuous reduction in the number of herds traced out and placed under quarantine is an important indicator of curbing the expansion of CWD, and the rapid identification of affected cervids—through live-animal testing within herds and prior to animal movement—could be an important verification tool.

___________________

7 Detailed in the USDA Chronic Wasting Disease Program Standards. See https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/cwd-program-standards.pdf (p. 43; accessed October 24, 2024).

8 See https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/health-promotion/5/measures-for-evaluating (accessed May 22, 2024).

TABLE 6.1 Approximate Numbers of CWD-Positive Captive Cervid Herds Identified in the United Statesa

| Category | Number of CWD-Positive Herds | Category | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal fiscal year | Not enrolled in HCP | HCP enrolled but not yet certified | HCP certified (% of total HCP-certified herds) | Total HCP-certified herds |

| 2018 | 7 | 0 | 6 (0.3%) | 1,875 |

| 2019 | 9 | 1 | 9 (0.5%) | 1,748 |

| 2020 | 17 | 2 | 7 (0.4%) | 1,723 |

| 2021 | 23 | 3 | 8 (0.5%) | 1,520 |

| 2022 | 12 | 2 | 6 (0.4%) | 1,537 |

| 2023 | 15 | 3 | 7 (0.5%) | 1,420 |

a Based on data from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/status-of-captive-herds.pdf (accessed May 22, 2024) and T. Nichols, personal communication (June 20, 2024). Data on the total number of captive herds by state across the United States were not available.

Despite the implementation of the national HCP, newly detected CWD-infected herds continue to be discovered (Kincheloe et al., 2021; Schultze et al., 2023). Traditionally, efforts at CWD prevention have focused mainly on precluding direct contact between non-infected captive cervids and infected captive or free-ranging cervids or carcasses thereof. More recently, the potential role of indirect contact with infectious materials originating from, but in the absence of, infected cervids is becoming more apparent, including avenues of indirect contact with infected free-ranging cervids (Schultze et al., 2023) or with other infected cervid facilities (C. Seabury, presentation to the committee, December 14, 2023). Examples of indirect contact that may present a potential risk include exposure to contaminated objects such as feedstuffs (including forage), water, non-susceptible wild or domestic animals acting as mechanical vectors, equipment (e.g., farm, handling, veterinary), vehicles, clothing, and potentially semen and fetal material.

The effectiveness of state-federal programs is dependent on timely detection of CWD infections; however, early detection in a captive herd may be limited because of the following:

- USDA-approved diagnostic tests are implemented primarily postmortem and can only be performed by USDA-approved laboratories.

- Captive cervids may be exposed to other sources of CWD agent in some locations given the local prevalence and distribution of the disease among free-ranging cervids.

- Antemortem cervid tissues need to be submitted for testing in a timely manner by captive cervid owners to preserve the diagnostic quality of the specimens.

- Extremes in ambient temperatures and the size and terrain of cervid enclosures affect if, how, and when dead cervids may be found and specimens collected.

State-federal programs also are limited by gaps in the current understanding of the epidemiology of CWD. The source of exposure in newly infected herds is often undetermined. The long incubation period of the disease, extended periods during which infected animals shed CWD prions, the variable expression of the CWD based on individual animal genetics, and the persistence of the prion in the environment all complicate the ability for captive cervid owners participating in the program to comply vigilantly with program requirements.

State Captive Cervid Programs

The success of the CWD HCP depends on cooperation between state agencies and USDA. However, intrastate movement of captive cervids does not fall under the control of the HCP, and movements of captive cervids within a state may be frequent and over long distances (Makau et al., 2020). The committee determined, through expert elicitation (see Appendix B for meeting agendas) and web resources (e.g., Michigan Department of Natural Resources [DNR]9), that state-based programs range from the complete banning or elimination of captive cervid

___________________

9 See CWD and Cervidae regulations in North America at https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/managing-resources/wildlife/wildlife-disease/disease-monitoring/cwd/cwd-hunting-regulations/cwd-and-cervidae-regulations-in-north-america (accessed August 27, 2024).

farming to nonparticipation in the HCP. Several western states have CWD programs for captive cervid facilities that predate the federal HCP and in some cases have more stringent requirements (e.g., mandatory participation, herd certification required for movements within the state; Michigan DNR10). The present study committee was unable to acquire epidemiological data or summaries of captive cervid facility CWD data collected through either the HCP or state-based programs to assess the influence of those programs on infection patterns. Nor could the committee mount a full review of state programs and regulations or determine if comparable state data were available to evaluate program efficacy in CWD control in those programs. A recent review of CWD in captive cervid herds suggests that such data are lacking (Mori et al., 2024).

Alternative Management Efforts

Alternative management approaches for captive facilities with CWD-positive cases and outside of HCP guidance protocols have not been described or assessed in detail. The approaches have typically involved either (1) live-animal testing and removal of positive cases (i.e., “test-and-cull”) or (2) genetic selection approaches to reduce the herd-level susceptibility to CWD. In an example of a test-and-cull approach, ranched elk were screened yearly by rectoanal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (RAMALT) biopsy, and a subset of CWD-positive animals was euthanized (Haley et al., 2018; Haley et al., 2020a). This was largely unsuccessful, and the herd was ultimately destroyed after the 3-year study. Studies relying on artificial selection, discussed in additional detail in a later section of this chapter, have focused on the PRNP gene alone or in tandem with genome-wide markers and are in the early stages of investigation (Haley et al., 2021a; Seabury, Lockwood, and Nichols, 2022). Future studies may consider combining these two approaches to help improve disease management. Early efforts to control CWD in captive research herds have been summarized (Williams and Young, 1992; Miller, Wild, and Williams, 1998), and updates on those efforts could be useful in understanding long-term prospects for control of CWD in captive herds. It seems plausible to the committee that reports or summaries of other nonfederal herd management plans and practices to limit case occurrence in captive facilities also may be on file in some states. Compilation of unpublished data as well as summary and evaluation of practices to control CWD could benefit national control efforts by providing assessments of intervention effects.

APPROACHES FOR CONTROLLING CWD IN FREE-RANGING CERVID POPULATIONS

With few exceptions, CWD has spread geographically and increased in prevalence over time—albeit to varying degrees—following the detection of a new focus, irrespective of disease control measures implemented by wildlife management authorities (Uehlinger et al., 2016). Multiple reviews of CWD management strategies for free-ranging cervid populations have observed that the tools for controlling CWD are limited, and some that seem promising have generally been too inconsistently applied across time, geographical area, and affected species to reliably determine their ultimate effects in curbing transmission and geographic spread (Miller and Fischer, 2016; Uehlinger et al., 2016; Fischer and Dunfee, 2022; Thompson et al., 2023). Additionally, wildlife managers consistently acknowledge that most of their efforts to control CWD in past decades have been constrained and confounded by a host of challenges that include, but are not limited to, compromised project design and implementation, underestimation of the extent of the disease-affected area or cervid populations and duration of the disease prior to its detection, inadequate duration of application, flawed assumptions of disease emergence drivers, political and socioeconomic conflicts, and regulatory agency jurisdictional limitations (Miller and Fischer, 2016; Uehlinger et al., 2016; Thompson et al., 2023).

The foregoing variables in CWD management implementation have complicated the ability of wildlife managers and decision makers to objectively determine the effects of CWD management strategies through time and across jurisdictions. Changes in the approaches, intervention frameworks, scientific and cultural knowledge, and political influence also have occurred since the discovery of CWD in North America (Williams and Young, 1992; Williams et al., 2002; Miller and Fischer, 2016; Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, 2017; Gillin and Mawdsley, 2018; Thompson et al., 2023). The current recommended strategies, techniques, and procedures are based on established principles for animal disease control (e.g., Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987; Wobeser, 2007; also see Box 6.4 and the section General Principles of Disease Management in Domestic and Wild Animals earlier

___________________

10 See https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/managing-resources/wildlife/wildlife-disease/disease-monitoring/cwd/cwd-hunting-regulations/cwd-and-cervidae-regulations-in-north-america (accessed August 6, 2024).

in this chapter) and incorporate CWD-specific scientific and practical knowledge but do require further application and assessment to fully understand their ultimate utility in long-term CWD management (Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, 2017; Gillin and Mawdsley, 2018; Fischer and Dunfee, 2022).

As noted previously, no common standard of acceptable response thresholds for CWD prevalence or related disease outcome metrics have been established by management authorities. Each wildlife management agency or authority sets its own disease management targets and sampling schedule. This is not surprising given that each U.S. management jurisdiction (i.e., state or federal wildlife management or agricultural agency, or tribal organization) operates under a unique set of circumstances based on the known distribution of CWD, prevalence, affected species, cervid population and movement dynamics, political climate, and cultural expectations within that jurisdiction (Holsman, Petchenik, and Cooney, 2010; Thompson et al., 2023). Consequently, an adaptive approach to CWD management efforts based on sound epidemiological principles (e.g., Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987; Wobeser, 2007) is likely to be effective for wildlife management agencies faced with a fluctuating and complex matrix of biological and social factors that emerge and persist following the discovery of CWD within their jurisdiction (Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, 2017; see Box 6.2 for a brief description of adaptive management). That said, several general management strategies have apparent effects on CWD prevalence and rate of spread (Table 6.2; Miller and Fischer, 2016; Fischer and Dunfee, 2022). These have been reported in formal and informal assessments and, along with other relevant disease management practices (e.g., Martin, Meek, and Willeberg, 1987), have served as a foundation for best practices in CWD management technical guidance (Chronic

TABLE 6.2 Apparent Effects of Strategies Implemented to Manage Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) in Free-Ranging Cervids, Including Measured Effect Sizes (where reported)a

| Management tool | CWD status | Reported apparent effect(s) | Host species | Jurisdiction | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatially targeted culling +/− hunting | recent exposure or introduction from identified source | Removals in the immediate vicinity of a known exposure source and few or no free-ranging cases appeared to prevent local outbreaks from becoming established based on subsequent monitoring. | white-tailed deer | New York Minnesota Québec |

Hildebrand et al., 2013; Evans, Schuler, and Walter, 2014; New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets, and Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine Wildlife Health, 2018; Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2019; Gagnier, Laurion, and DeNicola, 2020; also see state reports in Fischer and Dunfee, 2022 |

| Spatially targeted culling | emerging | Across six core management units, the odds of removing a CWD-positive deer via a spatially targeted herd-reduction program was ~3x higher than via hunting (odds ratio 3.37; 95% CI: 1.96-5.79). | mule deer white-tailed deer |

Alberta | Smolko et al., 2021 |

| Hunting | emerging to well established | Across 32 management units where starting prevalence was ≤5% among male deer, increasing hunter and harvest numbers led to lower prevalence in the following year (range of β values −0.043 to −0.218; P≤0.023); harvesting male deer later in the year also led to lower prevalence in the following year, with a smaller but additive estimated effect. | mule deer | Alberta Colorado Nebraska Utah Wyoming |

Conner et al., 2021 |

| Hunting | emerging to well established | In six of 12 hunt areas, the average number of licenses inversely correlated with prevalence among deer harvested 1-2 yr later; changes in license numbers positively correlated with the chance of adult male deer harvested 1-2 yr later being free from apparent infection (i.e., test-negative), with odds ratios ranging from 1.2 (95% CI: 1.17-1.24) to 17.04 (CI: 5.00-58.10). | mule deer | Colorado | Miller et al., 2020 |

| Spatially targeted culling | well established | When both states were actively culling (2003–2007), there were no statistical differences between state CWD prevalence estimates. Wisconsin government culling concluded in 2007, and average prevalence over the next 5 years was 3.09 ± 1.13% with an average annual increase of 0.63%. During that same 5-year period, Illinois continued government culling, and there was no change in prevalence. | white-tailed deer | Illinois Wisconsin |

Manjerovic et al., 2014 (also see Figure 2 from Thompson et al., 2023) |

| Management tool | CWD status | Reported apparent effect(s) | Host species | Jurisdiction | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatially targeted culling + hunting | well established | Management aimed to reduce CWD transmission between 2000 and 2005 via a combination of focal culling and a broader increase in female harvest, decreasing overall deer abundance by about 25%. Analyses carried out shortly thereafter suggested reductions in deer density had made little impact on CWD prevalence. However, subsequent assessments suggest those management actions may indeed have attenuated the outbreak. Surveillance on four winter ranges conducted during 1997–2002 indicated overall CWD prevalence in female deer >1 year old was 0.08 (95% credible interval 0.06-0.11), whereas prevalence during 2010–2011 was lower (0.04, 0.02-0.07). An independent comparison showed a comparable decline in prevalence among harvested male deer in the same area (2002: 0.15, 95% binomial confidence interval 0.11-0.20; 2017: 0.06, 0.04-0.09). | mule deer | Colorado | Conner et al., 2007; Geremia et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2020 |

| Selective removals via “test & cull” | well established | Over a 5-yr period, 48-68% of the estimated number of adult (≥1 yr old) deer were screened annually via tonsil biopsy IHC, collecting 1,251 samples from >700 individuals and removing IHC-positives. Among males, prevalence during the last 3 yr of selective culling was lower (one-sided Fisher’s exact test P~0.01) than in the period prior. Prevalence among females during the before and after periods was equivalent (P=0.77). Relatively higher annual testing of males (mean 77%) compared to females (mean 51%) may have contributed to differences in responses to management. | mule deer | Colorado | Wolfe et al., 2018 |

a Although the examples do not represent true field experiments, the observations illustrate the potential for some measurable level of CWD control to be achieved and offer a basis for designing management experiments that would allow for more rigorous assessments and comparisons of the apparent effects of various CWD management techniques.

Wasting Disease Task Force, 2002; National CWD Plan Implementation Committee, 2002; Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, 2017; Gillin and Mawdsley, 2018; Fischer and Dunfee, 2022).

Following from the concepts outlined by Thompson and others (2023), the measures implemented by wildlife management agencies to control CWD can be grouped into three broad categories covering those that are (1) preventive and preceding detection, (2) responses following initial detection, or (3) adaptive responses for sustained control. This categorization provides a useful temporal framework with which to review and assess CWD management actions for free-ranging cervids undertaken by wildlife management agencies. The next sections summarize some of these approaches.

Preparing for Rapid Response

Agencies have taken multiple actions intended to prevent or detect CWD introduction and lay a foundation for eventual responses to detection within their jurisdictions. These include regulatory interventions to reduce the potential of introducing CWD to new areas (e.g., live cervid and cervid carcass part movement restrictions, bans on baiting and feeding free-ranging cervid, cervid part disposal restrictions, and mandatory submission of hunter-harvested cervids for CWD surveillance programs), weighted risk-based surveillance strategies to detect early disease occurrences or outbreaks, and development and publication of a CWD response plan. Box 6.3 is only one example of a collaborative effort by tribal nations to, in this case, conduct surveillance, although other concerted efforts of enhanced CWD surveillance have been conducted by tribal agencies across the United States with federal support (Chronic Wasting Disease Task Force, 2002; USDA APHIS, 2021; Schwabenlander et al., 2022).

Sites heavily contaminated with CWD-infected cervid feces, saliva, or decomposing carcasses can become environmental reservoirs for infectious prions (Miller et al., 2004; Plummer et al., 2018) and serve as sources of indirect transmission of infectious prions (Miller et al., 2004). Locations where free-ranging cervids are artificially congregated by anthropogenic lures (e.g., food, mineral licks) thus may exacerbate direct and indirect transmission in areas affected by CWD. For these reasons, bans or restrictions on free-range cervid baiting and feeding and on high-risk carcass and carcass parts movement and disposal are generally considered prudent practices to reduce the risk of CWD transmission and introduction, although their effects remain incompletely understood. Rigorous surveillance strategies implemented prior to CWD detection (e.g., Samuel et al., 2003; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023) have facilitated the apparent eradication of possible CWD outbreaks, at least at local levels (New York State Department of Environmental Conservation11; Fischer and Dunfee, 2022; Thompson et al., 2023). To date, the only examples of CWD management strategies affecting the apparent local eradication of CWD (New York, Minnesota) have reportedly occurred because of rapid management response following the very early detection of a disease outbreak in the wild (Thompson et al., 2023). Over half of the initial detections of CWD in free-ranging cervids in the United States have occurred via state fish and wildlife agencies testing hunter-harvested cervids (Thompson et al., 2023), although this may reflect the wide reliance on this surveillance approach rather than its higher sensitivity (e.g., EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2023).

Fischer and Dunfee (2022) and Gillin and Mawdsley (2018) noted that the establishment of a CWD response plan prior to its detection has proven important in multiple states. Individual states have reported that doing so provided a foundation for establishing rapid and more widely accepted disease management actions and regulations that yielded greater likelihood to mitigate future disease spread and engender more support for long-term strategies (10-20 years) needed to minimize CWD’s impact on affected populations (Fischer and Dunfee, 2022). The critical importance of a publicly and politically supported CWD response plan cannot be overstated given that the values, attitudes, risk acceptance, and perception of loss vary greatly within and among hunters, landowners, wildlife enthusiasts, and other vested segments of the public (Schroeder et al., 2021; Meeks et al., 2022). The rapidity, duration, and resource commitment required to effectively address and manage a CWD occurrence in a free-ranging cervid population are greatly impacted by the public and political support for agency-led CWD management actions (Miller and Fischer, 2016; Thompson et al., 2023). Thus, the creation and publication of a CWD response plan prior to the discovery of CWD in a state allows time to implement methodical and genuine public engagement, education, input, and coalition

___________________

11 See https://dec.ny.gov/nature/animals-fish-plants/wildlife-health/animal-diseases/chronic-wasting-disease (accessed August 12, 2024).

building needed to gain support for strategies regarded as most likely to effectively manage CWD upon its detection (Gillin and Mawdsley, 2018; Fischer and Dunfee, 2022; Thompson et al., 2023). See Chapter 7 for discussion on decision analytical processes for identifying and addressing conflicting priorities in decision-making.

Responses Following Initial Detection

Response actions following the initial detection of CWD in free-ranging cervids within a management jurisdiction (tribal lands or U.S. states) have included increased risk-based sampling to delineate disease-affected areas (e.g., mandatory submission of hunter-harvested cervids), initiation of CWD control measures in those areas (e.g., modifications to hunter harvest rates, culling to reduce population density or to target localized disease foci), initiation or expansion of CWD-related regulations (e.g., live cervid and cervid carcass part transportation restrictions, cervid baiting and feeding bans, cervid hunter regulations), and communication and engagement with the public and interested and affected parties. Following first discovery, wildlife management agencies may

implement strategies to simultaneously increase sampling of cervids and reduce affected population density within a designated radius of the initial detection by increasing hunter harvest limits or targeted culling (Thompson et al., 2023). The enhanced, targeted, and ongoing sampling and removal of cervids in affected and surrounding areas allow agencies to adapt or modify management strategies in response to additional data on or changes in the patterns of CWD distribution or occurrence or where hunting is not an option.

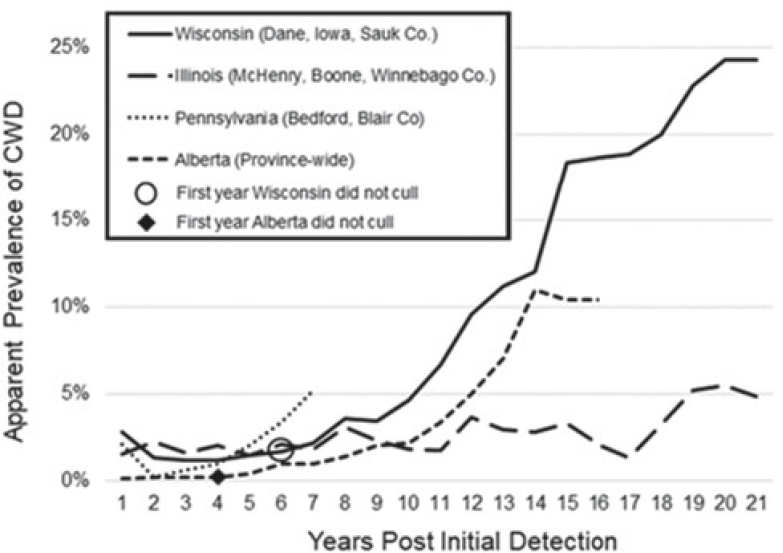

Current best practices (Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, 2017; Gillin and Mawdsley, 2018) advocate for the delineation of a CWD management zone or initial response area under the authority of the state wildlife management agency where a multi-year surveillance effort can be employed to reliably document disease prevalence and distribution with relative precision. This often requires a significant increase in testable samples acquired through hunter-harvested or agency-culled cervids. Establishing initial estimates of CWD prevalence and distribution is considered critical to formulating appropriate disease response measures as well as establishing baselines that can be used to reliably assess future impacts of new management efforts and strategies (Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, 2017). In conjunction with this, CWD management best practices (e.g., Gillin and Mawdsley, 2018) recommend reducing the probability of contact through reduction of local cervid population densities. Uehlinger and others (2016) noted that direct cervid population management (intensive culling, in particular) is the most empirically supported CWD control strategy documented to date. For example, a “test-and-cull” approach analogous to that applied in captive settings was feasible and effective in CWD suppression in males (among which management was more intensive) with limited application to a free-ranging mule deer herd (Wolfe, Miller, and Williams, 2004; Wolfe et al., 2018), although in practice this approach seems best suited to small geographic areas or as an adjunct to other broad-scale control measures like hunting. An approach for achieving such reduction at a larger geographic scale has been to combine targeted removal (i.e., culling) in high-risk or high-prevalence locations and an increase in regulated hunter harvest within a generous border around the primary area of concern (e.g., see state reports in Fischer and Dunfee, 2022). Some field studies have documented that targeted removal can maintain low disease prevalence when implemented consistently over time and focused on the highest-risk demographics (Manjerovic et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2023; Figure 6.1). However, these efforts must be maintained at adequate levels as some states have seen increases in apparent prevalence when targeted removal was abandoned (Thompson et al., 2023; Figure 6.1). As these efforts have not always been consistently applied, or sufficient time has not been afforded to assess outcomes (e.g., see Conner et al., 2007; Geremia et al., 2015), the reported results have been mixed (e.g., Smolko et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2023).

SOURCE: Thompson et al., 2023.

Sustained hunting pressure also has been shown to suppress epidemic growth in affected mule deer populations when adequately applied (Miller et al., 2020; Conner et al., 2021).

Once CWD has been established in a free-ranging cervid population, wildlife management agencies typically impose regulations aimed at reducing the risk of indirect disease transmission caused by human actions (Fischer and Dunfee, 2022; Thompson et al., 2023). Plummer and others (2018) demonstrated that artificial congregation sites (e.g., mineral licks) where cervid saliva, urine, and feces are aggregated create prion reservoirs in local soils and water sources that can facilitate indirect transmission of infectious prions to cervids. Experimental evidence has also documented that CWD can be transmitted indirectly to susceptible animals via environments contaminated by excreta (i.e., urine or feces) and decomposing carcasses of CWD-infected cervids (Miller et al., 2004). Given this, current CWD management best practices (Gillin and Mawdsley, 2018; Fischer and Dunfee, 2022) recommend that cervid baiting and feeding be prohibited following the discovery of CWD to avoid creating foci of contamination to which cervids are drawn, as well as moratoriums on the movement of live, captive cervids and high-risk, hunter-harvested cervid parts from CWD foci. Although logical and supported epidemiologically, specific assessments of the effectiveness of the foregoing measures have not been reported.

In addition to the practices described above, nearly all of the previously cited published reviews of free-ranging cervid CWD management successes, failures, and best practices emphasize the critical importance of integrating well-constructed and long-term efforts to engage and educate interested and affected parties into an agency’s overall CWD management approach. A review of these documents also illustrates that support from interested parties for CWD management tactics, regulations, and policies is much more difficult to secure after the disease is found if that support was not already in place (at least partially) as a product of a pre-detection CWD response plan drafting process (see previous section on pre-detection activities). Given the numerous factors (cultural relevance, political incentives, recreational values, economic impacts) that influence the support of constituents and interested parties for CWD management strategies described in the citations above, long-term viability (and thereby effectiveness) of control efforts appears to benefit from investment in long-term public education and engagement efforts that dovetail with proposed disease control efforts.

Box 6.4 provides a toolbox of sound CWD control strategies that have been or will be described in this chapter, and Table 6.2 presents published examples where the apparent effects of management strategies have been quantified in situ in free-ranging cervids. As noted elsewhere in this report, the ultimate impacts of CWD management strategies can be difficult to measure. However, the observed effects documented in those examples (Table 6.2) illustrate that levels of CWD control can be achieved and that experimental approaches to future CWD management are needed to allow for more rigorous assessments and comparisons of the apparent effects of various CWD management techniques employed by management authorities (Conner et al., 2007; Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, 2017).

Adaptive Responses for Sustained Control

Experience to date dictates that initial responses to CWD outbreaks will need to be modified over time as circumstances change, or as new or better information becomes available to responsible resource managers (see Box 6.2 for a description of adaptive management). As CWD and its management progress over time, geographic area, and impacted species, agencies with jurisdiction over free-ranging cervid health will experience a plethora of emerging factors that challenge adaptation. These include, but are not limited to, political opposition to disease management interventions that span multiple administrations, limited sustained funding needed to implement management strategies at time scales required to affect population-level disease control, opposition by interested groups (e.g., hunters, captive cervid facility representatives, and conservation nongovernmental organizations), and limited CWD testing capacity and cervid carcass disposal options (Thompson et al., 2023).

Given the above challenges that represent the complex biological, social, political, and temporal variables that can impact the efficacy of CWD control efforts within free-ranging cervid populations, no standard or uniform management recommendations exist that can be applied to all CWD-affected areas, cervid populations, or disease management timelines. Therefore, an adaptive approach that incorporates the previously referenced known best management practices and constructs current and prospective management strategies as experiments has been suggested as likely the most

effective approach to successful and long-term CWD management (Conner et al., 2007; Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, 2017). Although tailored to western jurisdictions, landscapes, and cervid species, the approach can likely be applied to other regions of the United States. Considering the uneven effectiveness of past actions to control CWD in free-ranging cervid populations, the broader embrace of testable management actions; data collection and evaluation; and coordinated, adaptive disease management planning as proposed in the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (2017) recommendations offers a viable framework for refining future efforts.

NATURAL AND ARTIFICIAL SELECTION

Studies in free-ranging deer and elk herds are beginning to uncover evidence of natural selection for less susceptible PRNP genotypes on a local level in areas of relatively high CWD prevalence (Monello et al., 2017; Chafin et al., 2020; Ketz et al., 2022), although none so far have considered genome-wide associations with susceptibility that have recently been uncovered. As discussed in Chapter 2, prion infections are inextricably linked to the host’s prion protein, encoded by the prion gene—PRNP. Hosts lacking a functional prion gene, either naturally or through various means of genetic manipulation, are inherently resistant to prion infection and incapable of developing disease with even high-dose experimental exposure (Büeler et al., 1993; Richt et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2009; Benestad et al., 2012).

Alternatively, hosts with natural variations in the prion gene (e.g., sheep as described in Chapter 2) are highly resistant to infection following either natural or experimental routes of exposure—a finding that has led to the near-eradication of scrapie from North America and sheep-producing countries through the selective breeding of individuals carrying what are considered conventional scrapie-resistant PRNP genotypes (USDA APHIS, 2023; Melchior et al., 2010). Unlike as observed with sheep, there have not been any naturally occurring variants of the PRNP gene in any cervid species that are, alone, highly protective against CWD infection. Amino acid variations are present in many cervid species, often linked to altered susceptibility or delayed disease progression (see Chapter 2). Current research seeks to determine whether PRNP variations in white-tailed deer are sufficient to prevent infection with natural exposure (Haley et al., 2021a), with a second study highlighting the significant role that genes beyond PRNP have in preventing infection in captive cervids (Seabury, Lockwood, and Nichols, 2022).

Investigating the potential for artificial selection to aid with CWD management in captive cervids has, to date, been challenging as most captive herds with confirmed cases of CWD are immediately placed under quarantine, making it difficult to modulate herd genetics through the addition of new breeding males and females. Box 6.5 provides a description of the role genetic selection might have in the management of CWD in captive herds. Ultimately, most of these herds are depopulated. One ongoing project is assessing the feasibility of CWD management through selective breeding of captive white-tailed deer with less-susceptible PRNP alleles on a

property with historically high disease prevalence. At the onset of the study, the highly susceptible 96G allele (see Chapter 2) made up over 90% of the alleles present on the farm, and CWD prevalence ranged from 20 to 60%; individuals homozygous (i.e., having two identical versions of the same gene) for the 96G allele made up a disproportionate number of positive animals, as reported previously (Haley et al., 2021a; Ketz et al., 2022). Over the first phase of the project, PRNP allele frequencies were shifted such that by the seventh year of selective breeding, the 96G allele made up less than 15% of the alleles present, with the 95H and 96S alleles making up much of the remaining alleles (Haley et al., 2021b; Haley, unpublished data).

Using crude markers of fitness, there have been no observed adverse effects in reproductive rates or the subjective health of offspring born with less-susceptible PRNP genotypes in the study’s initial phase. The project’s second phase will assess the impact of changing PRNP allele frequencies on disease prevalence, with some early evidence of a meaningful reduction in disease occurrence (Haley et al., 2021b).

Although the role that the PRNP gene plays in prion infections is well understood, other genes or loci must have a role throughout disease pathogenesis, from prion uptake in the gastrointestinal tract; to hematogenous, lymphoreticular, and peripheral nervous system trafficking; and ultimately amyloid clearance from the periphery and central nervous system. Recent and ongoing genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in both white-tailed deer and elk have identified a suite of polymorphisms strongly associated with infection status, many of which overlap with those associated with an increased risk of human Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and other diseases (Seabury, Lockwood, and Nichols, 2022; Seabury et al., 2020). Collectively these polymorphisms can be used to assign individual animals with GEBVs, guiding selection of ideal breeding candidates for management through enhanced resistance to disease (Stear et al., 2012). This process has been used in a range of species to advance livestock health—including improved nematode resistance in sheep to viral resistance in captive sea bass (Palaiokostas et al., 2018; Hayward, 2022). With aggressive management, including targeted culling of animals with poor GEBV and intensive breeding with high GEBV animals, significant improvements in herd-level GEBVs were seen in 2-3 years (C. Seabury, communication to the committee, December 14, 2023). Field studies in captive white-tailed deer employing GEBV-guided selective breeding are underway, and though objective data are not yet available, they have the potential to show additional gains in resistance beyond those currently expected from a focus on the PRNP gene alone.

While selective breeding may have the potential for facilitating CWD prevention and management in captive cervids, it may be inconsistent with the current paradigms for management of free-ranging deer and elk species. This paradigm does not preclude, however, the ability to observe natural changes in gene frequencies in CWD-affected free-ranging cervids over time. To date, these studies have focused exclusively on the frequencies of PRNP polymorphisms in high prevalence areas, though future studies employing GWAS in free-ranging cervids where CWD occurs may provide additional support for disease resistance approaches in captive cervids. In white-tailed deer, for example, a retrospective guided modeling study predicted that the frequency of the 96S allele in free-ranging animals, which typically makes 25% or less of the alleles in free-ranging populations (Johnson et al., 2006a; Brandt et al., 2015; Raudabaugh et al., 2022), would become dominant in an evolutionarily short period due to CWD selective pressure (Robinson et al., 2012; Ketz et al., 2022). Two separate modeling studies in elk, using regional PRNP gene frequency data, have also found that polymorphisms in this gene may help stabilize affected populations, with the potential to mitigate risks for local extirpation (Monello et al., 2017; Fameli et al., 2022). Finally, studies in mule deer have reported evidence of selective pressure against the highly susceptible 225S genotype, with an increasing frequency of the less-susceptible 225F allele over just a couple of decades in CWD-affected populations—more so in herds with higher prevalence (Jewell et al., 2005; LaCava et al., 2021; Fisher et al., 2022). However, evidence of subjective behavioral and health abnormalities in 225F homozygous mule deer in captivity (Wolfe, Fox, and Miller, 2014) combined with observed scarcity of 225FF individuals in the wild—even in the face of abundant selective pressure from CWD (LaCava et al., 2021; Fisher et al., 2022)—point to the further potential of a balancing equilibrium between CWD and underlying 225F fitness-based selection pressure. In addition to host fitness, it is important to note that many of these studies do not consider the risks of newly developed strains of CWD, particularly those that might preferentially infect cervids with PRNP genotypes presently considered less susceptible to infection (Velásquez et al., 2015), as well as the downstream effects of infected cervids with extended incubation times shedding infectious prion in the environment for prolonged periods (Cheng et al., 2016).

Although past studies on CWD-driven selective processes in cervids have almost exclusively focused on the PRNP gene, future studies considering genome-wide polymorphic genes and loci may further inform our understanding of disease susceptibility. Patience should be afforded toward studies investigating either selective process, as increasing disease resistance may take several years to manifest in the case of captive cervids and decades perhaps in free-ranging cervids (e.g., LaCava et al., 2021). It remains to be seen, however, if genetic changes over time—through either selective breeding or natural selection—will affect duration of prion shedding or susceptibility to novel CWD strains. In addition to these concerns, studies should also consider factors such as host fitness (e.g., reproductive rates and offspring health); disease pathogenesis; and, importantly, the effectiveness of current diagnostic protocols in identifying infected individuals.

VACCINES

The development of vaccines for prion diseases like CWD is challenging because the infectious prions are considered “self-proteins” (i.e., produced by the host itself) and thus incapable of eliciting a detectable adaptive immune response (generation of an antibody response)12 (Pilon et al., 2013; Zabel and Avery, 2015; Wood et al., 2018). To overcome this problem, research groups are applying novel approaches to vaccine development. An early vaccine using antibodies generated against a short part of the prion protein (the “YYR epitope”) has, to date, had limited success (Tashuck et al., 2014; Wood et al., 2018). Although trials in mice found the approach both safe and effective at generating an immune response, a field trial of the YYR vaccine in elk kept in CWD-contaminated paddocks found that vaccinated animals had shorter incubation periods than unvaccinated animals (Wood et al., 2018). There were multiple potential explanations for this, including the possibility that the antibodies to the vaccine induced misfolding of PrPC, or antibody binding of PrPSc in the gut resulted in increased uptake of infectious prions, among others (Wood et al., 2018).

Another more promising approach warranting further investigation used constructs composed of paired PrPC molecules (“dimeric PrPC”) expressed in bacteria (i.e., “recombinant” prion proteins, a process similar to components of the RT-QuIC diagnostic assay [Chapter 4]). The antibodies generated were specific for PrPC and provide protection against prion infection in mouse models of CWD (Abdelaziz et al., 2017; Abdelaziz et al., 2018). The PrPC-specific vaccine targeted PrPC outside the brain, using aggregation-prone recombinant prion proteins for overcoming self-tolerance (Abdelaziz et al., 2017; Gilch et al., 2003; Kaiser-Schulz et al., 2007). Proof-of-concept in rodent and reindeer models demonstrated that tolerance to the PrP “self-proteins” can be overcome by this approach, resulting in detectable humoral and cellular immune responses without adverse side effects (such as autoimmune disease) and significant protection in CWD challenge models (Abdelaziz et al., 2018).

A third approach incorporated PrPSc-relevant epitopes onto the surface of fungal proteins (specifically Het-S, which also undergoes fibrillization [Wasmer et al., 2008]). The antibodies generated by this approach are specific to PrPSc and are hypothesized to interfere with PrPSc:PrPC interactions, thereby blocking conversion. A similar approach provided protection in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease (Pesch et al., 2024). Efficacy of the vaccine against cervid PrPSc needs to be evaluated.

A significant amount of research with the various vaccine candidates is needed, including extensive testing in captive cervids followed by pilot studies in some well-studied free-ranging cervid populations, focusing on efficacy, impact on shedding, as well as duration of protection. Ongoing experiments in experimental infected captive white-tailed deer and in naturally infected free-ranging elk will provide objective data on these vaccine candidates. In the short term, these may prove most useful in captive herds. Long-term goals would include the development of oral vaccines, analogous to those used for rabies (Slate et al., 2009), for vaccination of free-ranging populations. In addition, perspectives and acceptance by the broad array of interested parties and groups will affect the success of any potential vaccine applied to free-ranging cervids. Social science/human dimensions investigation prior to the delivery of any vaccine is essential. Barriers to vaccination also exist, especially in free-ranging cervids, notably given the potential need for repeated vaccination in the face of chronic exposure, challenges associated with oral

___________________

12 See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/adaptive-immunity (accessed October 26, 2024).

uptake of a vaccine, and uncertainties about the impact of the vaccines on shedding of CWD prions as well as the potential protection against a range of different CWD strains.

Without better knowledge of deer and prion biology, current vaccine development strategies may not be optimally utilized. While the development of vaccines for CWD is an important endeavor—ultimately helping guide strategies for human protein misfolding disorders (Kwan et al., 2020)—the same complexities concerning the potential effectiveness of genetic selection also apply. For example, while prolonged survival in mouse models following vaccination and subsequent infection with CWD has been observed (Abdelaziz et al., 2018), it is unknown whether vaccination with any of the proposed vaccine candidates would prevent CWD transmission or reduce prion shedding. Current and future vaccination strategies also need to consider their effectiveness following challenge with naturally occurring levels of CWD prions representing multiple CWD strains, and whether vaccination may impact the accuracy of available diagnostic tests (see, e.g., Pasick, 2004).

ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL

Stopping or slowing the spread of CWD will also be dependent on decontamination of the environment. Although it is not known how long CWD prions will persist in soil matrices and other soil components (e.g., nasal bot larvae maturation in soil [see Chapter 3]; Soto et al., 2024), on plants, and on other fomites, a variety of studies suggest CWD prion persistence is variable, depending on environmental conditions and soil types. Several different approaches have been tested or are being developed. In South Korea, a contaminated farm area was extensively treated to attempt to remove all environmental sources of CWD. Topsoil was removed and the landscape treated with hydroxide, and then the area remained unoccupied for several years (Sohn, 2018). The efficacy of this treatment is unknown. The extensive nature of the approach would, however, be all but impossible to reproduce on the scale needed to decontaminate all foci in the United States, and thus it is more practically limited to farmed cervid facilities.

Several groups have suggested that humic acid (HA), a naturally occurring component of some soils, has anti-prion properties (Giachin et al., 2014; Kuznetsova et al., 2018). HA comprises much of the organic matter in the upper horizon of soils in many regions where CWD occurs and is also a component of many fertilizers. HAs are comprised of polymeric mixtures of weak aliphatic and aromatic organic acids, encompassing a wide variety of organic structures. In the research lab, using enriched PrPSc preparations and purified HA, the PrPSc appears to be degraded, and infectivity reduced, when CWD samples are treated with HA at concentrations commonly found in a variety of soils (Kuznetsova et al., 2018). It has not, however, been demonstrated that HA has efficacy against soil-bound prions, as interactions between prions and soil may increase the resistance of CWD prions to degradation.

Numerous studies over the past few decades highlighted the ability of high temperatures to inactivate prions. Most studies involved incineration and very high titers of CWD (greater than 109 infectious units per gram of tissue). Incineration of prion-infected tissues at 600°C did not completely inactivate the infectious prions despite ashing (i.e., removing organics from) the material (Brown et al., 2004). However, at temperatures of 1,000°C, no infectivity remained. Inactivation of prions at high temperatures led to suggestions that wildfires could perhaps decrease the environmental load of CWD, particularly when prion levels in the environment are low. Although it is unlikely that most wildfires would attain temperatures sufficiently high to inactivate high titers of CWD, removal of infected plants and, perhaps, surface soils containing prions could reduce the amount of CWD in the environment (Zabel and Ortega, 2017). Given the practice of prescribed burning for other landscape management purposes, further research on the impact of prescribed or natural wildfires on environmental prion remediation is warranted.

Given the combination of the long preclinical phases of disease, coupled with environmental contamination that may play a role in ongoing transmission, a multi-pronged approach to mitigating disease is requisite. Currently, the efficacy of these potential environmental mitigation strategies has not been fully determined, and at present, none are recommended for use by cervid farmers or wildlife managers (USDA APHIS, 2019; Gillin and Mawdsley, 2018). Like CWD vaccine development, methods for decontamination of the environment are not imminent. This is primarily due to the difficulty of detecting and quantifying CWD prion load in the environment, the knowledge of how much CWD prion must be removed to decrease the likelihood of transmission, and the soil/vegetation-type variation in avidity of prion binding.

EFFECTIVENESS OF PUBLIC MESSAGING IN CWD MANAGEMENT