Exploring Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Health Equity Commitments and Approaches by Health Organization C-Suites: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 4 Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion and Health Equity Implementation and Measuring Success at the C-Suite and Institutional Level

4

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion and Health Equity Implementation and Measuring Success at the C-Suite and Institutional Level

The workshop’s third session featured two panels exploring different aspects of C-suites and institutions that are implementing and measuring their diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and health equity initiatives. The first panel featured two presentations on studies from the field on chief health equity officers. The second panel engaged in a moderated discussion about experiences from the field on DEI and health equity implementation, and how success is measured at the C-suite and institutional level. Perspectives were presented by representatives who directly or indirectly oversee DEI and health equity implementation at a large health system (Mount Sinai Health System), a consulting firm (HealthBegins), and a social justice organization (Race Forward). Panelists were asked to share how DEI and health equity function internally and externally, implementation challenges faced, and how they measure success in translating learnings from the C-suite to the institution and external engagement.

THE EQUITY OFFICERS NATIONAL STUDY: AN EARLY LOOK AT WHAT EQUITY OFFICERS ARE DOING TO ADDRESS HEALTH CARE EQUITY IN U.S. HOSPITALS

Joel Weissman, deputy director and chief scientific officer of the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and professor of surgery in health policy at Harvard Medical School, discussed the background and aims of the Equity Officers National Study (EONS) (Weissman et al., 2023). Many hospitals and health care systems, he said, have created equity officer positions or assigned equity responsi-

bilities to staff, but little is known about the activities and responsibilities of the individuals in these new positions.

The main purpose of EONS, Weissman explained, was to describe the scope of these roles, including the priorities, facilitators, barriers, and skills needed for success. To accomplish the goal, the EONS team surveyed equity officers in U.S. community hospitals, with 340 equity officers completing the survey. The team then followed up with a purposive sub-sample of 26 one-on-one qualitative interviews. Weissman said that he expects the number of health equity officers to grow exponentially in the coming years because of the commitment of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to equity measures1 and the Joint Commission’s new equity standards.2

Findings from the survey include the following:

- Most equity officers have only been in the position a short time, with 35 percent being in the job for less than a year.

- Only a minority of health equity officers are Black, Hispanic, or Latino.

- Nearly 59 percent of the responding health equity officers work at the multi-hospital system level, not at individual hospitals, which has implications for the relationships between individual hospitals and their communities and for new CMS and Joint Commission standards.

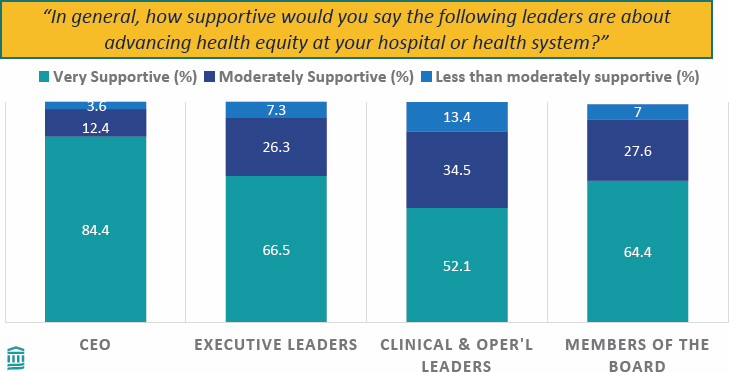

- Health equity officers perceive that their hospital leaders support their work, though this is less true among clinical and operations leaders and board members (Figure 4-1).

- A majority of health equity officers, but far from 100 percent, feel well prepared to carry out key tasks, though it may be unrealistic to expect someone to have expertise across a broad range of topics (Figure 4-2).

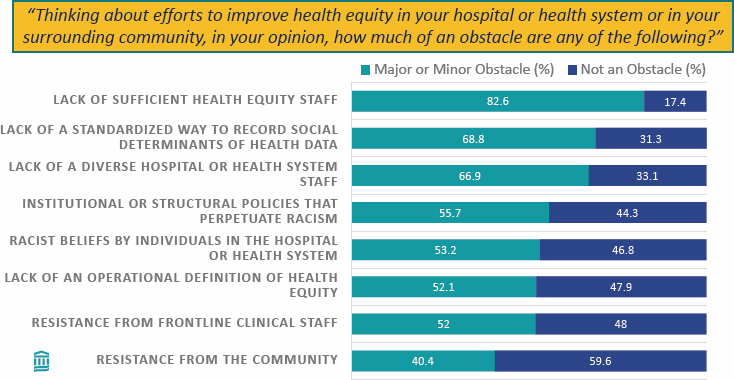

- Equity officers face an array of obstacles (Figure 4-3).

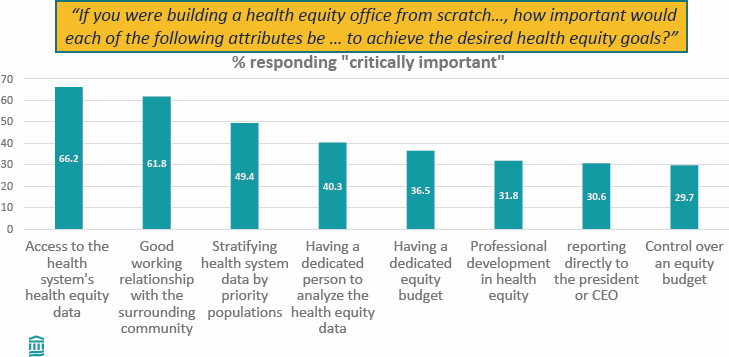

- When building a health equity office from scratch, access to a health system’s data and a good working relationship with the community were the most important attributes of an equity office (Figure 4-4).

In addition to the general survey results, interviews with select respondents identified several challenges they face in their equity work

___________________

1 https://mmshub.cms.gov/about-quality/quality-at-CMS/goals/cms-focus-on-health-equity (accessed November 13, 2023).

2 https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/newsletters/newsletters/joint-commission-online/jan-11-2023/healthcare-equity-standard-now-npsg/ (accessed November 13, 2023).

SOURCE: Presented by Joel Weissman on October 5, 2023, at Exploring Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Health Equity Commitments and Approaches by Health Organization C-Suites: A Workshop (Weissman et al., 2023).

(Table 4-1) and offered advice they would give other equity officers (Table 4-2). Regarding that advice, in the future, Weissman said there should be efforts to evaluate whether equity officers have an impact on disparities; but he cautioned that efforts to reduce inequity should continue due to the inherently moral value of the work.

SOURCE: Presented by Joel Weissman on October 5, 2023, at Exploring Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Health Equity Commitments and Approaches by Health Organization C-Suites: A Workshop (Weissman et al., 2023).

SOURCE: Presented by Joel Weissman on October 5, 2023, at Exploring Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Health Equity Commitments and Approaches by Health Organization C-Suites: A Workshop (Weissman et al., 2023).

SOURCE: Presented by Joel Weissman on October 5, 2023, at Exploring Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Health Equity Commitments and Approaches by Health Organization C-Suites: A Workshop (Weissman et al., 2023).

TABLE 4-1 Challenges Health Equity Officers Face in Their Work

| Challenge | Exemplar Quote |

|---|---|

| Where do we start? | “Our greatest challenge is just... doing this knowing that we’re not going to get it all right the first time.” |

| How do we educate staff and community members? | “We’ve got to get our own house in order before we can boldly be educating the community on these issues.... ” |

| How can we advocate for hospital policies ...that promote health equity? | “I don’t think we’ve done enough to, in a tangible, practical way, say, ‘[The clinical team’s] work ...[needs to] look a little different because you’re [a] health system in the community ... doing health equity work.’” |

| How can we collect data systematically? | “What are the best standards for asking social determinants of health screening? What are the right clinical settings? How do you do that in a secure confidential way so that you get data that you can act on?” |

| How do we know the data we collect is valid and accurate? | “[A challenge is] recognition of data systems that are not where they need to be. And the speed with which accountability for having those has happened is a little bit scary.” |

| How can we use the data in an actionable way? | “[The clinical team needs to understand] ‘I’ve got these community partners. I’ve got these pathways. It’s all baked into my EMR now. I can actually ask about housing insecurity and not go, ‘Well, I don’t know what to do about that so I’m not going to ask’.” |

SOURCE: Presented by Joel Weissman on October 5, 2023, at Exploring Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Health Equity Commitments and Approaches by Health Organization C-Suites: A Workshop (Weissman et al., 2023).

TABLE 4-2 Advice from Equity Officers

| Advice | Exemplar Quote |

| Identify your values and vision | “Know your area, be innovative, and create your own narrative.” |

| Gain buy-in and support | “Make sure that the CEO and the top leadership are aligned. And if not, how can you manage up to educate and activate and prioritize the work?” |

| Don’t reinvent the wheel | “Look at what other hospitals and health systems are doing. Network, talk to people, talk about how they built, [and think] about setting.” |

| Build relationships and work together | “Take your existing community relationships...and start to share with them what you’re seeing in your data...your bandwidth to tackle this stuff is suddenly so much easier because [you’ve] got an expert in food insecurity...and all [you’re] doing is making sure [you’re] a good partner to that work.” |

| Be the squeaky wheel | “Always speak up. Always recognize injustice and speak up...things don’t change on their own.” |

| Play the long game | “You(’ve) got to stay committed, stay focused because it’s a long journey. It’s not a sprint at all. It [needs] constant attention.” |

SOURCE: Presented by Joel Weissman on October 5, 2023, at Exploring Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Health Equity Commitments and Approaches by Health Organization C-Suites: A Workshop (Weissman et al., 2023).

One example of the challenge of using data in an actionable way involves what the next step is after collecting and using information on the social determinants of health associated with an individual patient. Clinical teams, Weissman said, may not have or know the next step to help patients who screen positive for a social determinants of health need. If the hospital has an existing partnership with community organizations that address social determinants of health, the clinical team can refer the patient to the appropriate community partner. However, this can lead to those community organizations experiencing an increased demand but not having the necessary financing and staffing to meet all the needs of the people they serve.

These findings, Weissman cautioned, should be considered in light of the study’s limitations, including the relatively low response rate to the survey, which may reflect a lack of input from places that are not as comfortable sharing their information. The study also focused on descriptive information, experiences, barriers, and facilitators and did not procure data on the factors that contribute to equity officer successes.

The conclusions Weissman drew from EONS are that a minority of hospitals have equity officer positions, many of which are new and exist only at the system level, raising questions about community ties. Collaboration is key, he said, and equity officers have several requirements to succeed. These include resources appropriate to the task; clear and uniform strategies for collecting, analyzing, and acting on valid patient data; training on best practices for educating staff and patients on health equity; coaching on how to build trust and sustainable relationships with surrounding communities; and tools or strategies for changing the culture of where staff work.

THE INSTITUTE FOR HEALTHCARE IMPROVEMENT’S HEALTH EQUITY LEADERSHIP FRAMEWORK

Keziah Imbeah, senior research associate and innovation and equity and culture lead, and Camille Burnett, vice president for health equity, both at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), discussed the health equity leadership framework that IHI has developed over the past few years. IHI, Imbeah said, has a process it calls the 90-day learning cycle, which involves spending 90 days to focus on a specific project. Here, she and her colleagues were given two tasks. The first was to study the health equity officer role and gain information about the responsibilities, skills, and competencies required to achieve success as a health equity officer. The second was to understand the gap between the current state of this position and a future state that is strategic, grounded in improvement science, and positioned to lead system-wide improvement toward health equity.

The research process, Imbeah said, involved completing a literature scan; conducting expert interviews with individuals serving as health equity officers, those who formerly worked in hospital systems, health equity offices,

and experts who have facilitated learning communities for health equity officers; and organizing focus groups comprising health equity officers to pressure test and further refine theory. Imbeah noted that the themes that arose from the interviews were the variance in titles people have, the resources they have, the sizes of their teams, the scope of their work, and their reporting structure.

Imbeah stated that one notable difference the interviews identified was the distinction between a health equity officer, whose focus was largely external, and an internally focused DEI officer. Some health systems separated these roles, while others combined them into one position. One consistent finding was that organizations had high expectations and that people in these roles were asked to do a great deal in a short period. Imbeah explained that in addition to developing a consolidated job description and highlighting the skills and competencies needed to succeed as a health equity officer, she and her colleagues considered the landscape and externalities that would support health equity officers. When the process ended, IHI published an executive summary that included a health equity officer job description and a theory of change describing the necessary components for success in the health equity officer role.

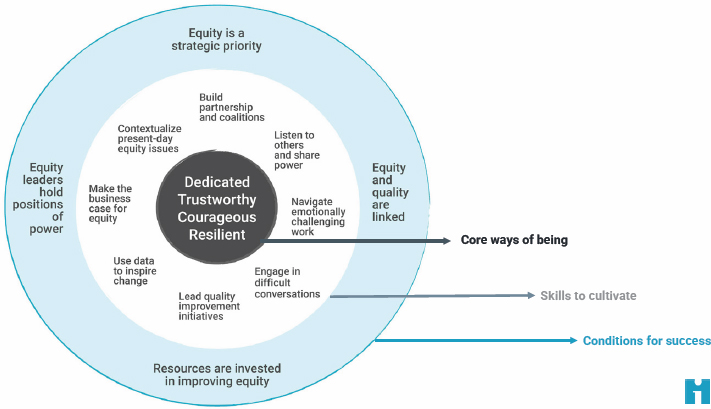

Burnett then discussed the health equity leadership framework developed using the results of this study (Figure 4-5). The framework comprises three core categories: the core ways of being, which speaks to characteristics of the health equity officer; key skills to cultivate; and

SOURCE: Burnett, C., T. Bolender, and K. Imbeah. 2023. IHI Health Equity Leadership Framework. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Presented on October 5, 2023, at Exploring Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Health Equity Commitments and Approaches by Health Organization C-Suites: A Workshop.

conditions for success, which includes the external factors inextricably linked to a leader’s ability to succeed.

Burnett said four elements reflect the traits and values of the equity leader: being dedicated and committed to equity and anti-racism, trustworthy, courageous, and resilient. Burnett noted that leading the change that is necessary and sometimes difficult requires leading with integrity, humility, and love. She added that these traits are also key to building, and often rebuilding, trust with communities and other organizations that can enable the co-creation of an equitable future. Resilience is the trait needed for the endurance and stamina to do this work, and it reflects the need for renewal.

Regarding the skills to cultivate, Burnett said that one fundamental theme the interviews identified was being able to contextualize inequities using a historical perspective, acknowledging that history, and redressing it through a process of quality improvement. Burnett said that other critical skillsets include the ability to use qualitative and quantitative data to inspire change and make the moral, financial, and business case as to why this work is essential; the ability to build partnerships and coalitions; and the ability to be visionary, adaptive, and willing to share power. These skills, Burnett said, require a certain level of emotional intelligence to be able to show up in ways that are engaging and that lean into the problem.

Burnett said that the conditions for success include having an organization that makes equity a strategic priority, especially at the chief executive officer and board levels; links equity and quality; and invests financial and human resources to improve equity. She concluded that putting equity leaders in positions of power is also important for success.

This work, Burnett said, led to the launch of IHI’s 12-week Leadership for Health Equity program, which is built around these core areas. This program is based on the innovation cycle that Imbeah discussed, and it brings together system actors across the health care ecosystem to engage in deep work in health equity and to obtain the knowledge, skills, and tools they need to succeed. Burnett mentioned that experts in the field mentor, coach, and guide the participants in weekly gatherings where they can share ideas and obstacles they face. Burnett concluded that the program also provides an important and safe space for critical reflection.

EXPERIENCES FROM THE FIELD

Workshop planning committee member Reginald Tucker-Seeley, vice president of health equity at ZERO Prostate Cancer, moderated the discussion among Pamela Abner, vice president and chief diversity operations officer at Mount Sinai Health System and an adjunct professor at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health; Rishi Manchanda, chief executive

officer at HealthBegins; and Jane Mantey, director of narrative and culture strategies at Race Forward. Tucker-Seeley started the discussion by asking the panelists for their thoughts on how important it is for C-suite leaders to understand and communicate the distinctions between the efforts of chief DEI officers and chief health equity officers. Abner replied that, to her, DEI is foundational work for an organization that focuses on core elements such as understanding why DEI initiatives are important for an institution and how to engage staff around DEI issues. Health equity requires a separate focus and should not be co-mingled with general DEI work, she said. She also remarked that, in her experience, most leaders do not know what DEI and health equity refer to and what DEI and health equity initiatives are trying to accomplish.

Mantey agreed that C-suite leaders often do not understand these terms. However, she said, they do not want to appear to lack knowledge, vision, and compassion, so they say the right things and get their teams to do the right things. Mantey’s organization encourages its clients to start by envisioning why it is important to do this work, what the organization’s shared values and goals are, and how to get there. DEI work, she said, is about getting one’s house in order to be able to execute externally. “You have to explain to your staff and colleagues that the best way we can serve people is to ensure that we embody as an organization the principles of health equity through our workflows, through our policies, and [through] our practices,” Mantey said. Jumping into health equity without a plan and an understanding of DEI and health equity often leads to failure, she added.

Manchanda said he sees the tension between internal and external efforts play out in several ways. One way involves the lack of shared understanding and definitions, as Abner and Mantey noted. Another way this tension arises is at the intersection of conversations around value and demonstrating the business case and return on investment from DEI and health equity work. Manchanda’s organization tries to address this tension by first talking about inequities in a manner that health care audiences relate to, which is in the context of harm. Harm is something those involved in health care understand, so discussing DEI and health equity issues as contributing to patient harm strikes home.

Readiness to Change

Tucker-Seeley recounted how, when he was in academia, he developed a framework for measuring and reporting health inequities. However, when he tried to apply this framework within a real organization, he realized that he had not considered the readiness of an organization to successfully implement health equity and DEI initiatives. Tucker-Seeley

asked the panelists to comment on the importance of organizational readiness and the components of organizational readiness that lead to success. Manchanda commented on the need for common standardized readiness assessment tools, which are available. However, gauging readiness risks assessing readiness in a way that constrains the imagination and accountability of institutions to do internal work but not engage in the multilevel interventions that research has shown are important for advancing equity.

Manchanda said that newly minted health equity officers, many who come from public health backgrounds, are often asking how they can balance the need to meet emerging health care equity performance requirements and social need in a manner that enables their institution to address internal drivers of inequity while also addressing social needs. To address this challenge, Manchanda’s organization has developed an assessment tool that allows leaders to evaluate whether their organizations are ready to meet compliance requirements and if they are ready to achieve equity for their patients, the people they employ, and the communities they serve. Failing to gauge readiness across these domains risks reinforcing a narrow health care–centric perspective rather than using the opportunity to embed health care within the broader public health agenda, he said.

Mantey commented that readiness for an organization’s leaders requires some historical grounding about the structural violence that has occurred over decades and creates an organizational culture that can make it difficult to introduce a new way of doing things regarding health equity. She also noted that moving to health equity runs counter to the economic drivers that helped create inequities. “We need a level of honesty and transparency about the kind of political economy that we are dealing with,” she said. “We cannot achieve health equity without actually addressing the underlying causes of that system, which is to extract from people who have the least amount of wealth, least amount of power, and least amount of voice in making decisions.”

Abner agreed that health system leaders do not necessarily have the capacity to engage in equity work correctly, largely because they have not learned how to engage. Her organization uses a collective impact approach that brings together leaders in an organization for learning exercises. Abner said that over the course of more than a year, these exercises provided an understanding of racism and the history of harm that marginalized populations have experienced, along with a roadmap and strategic plan they can follow. She added that this process also helps leaders better understand their own attitudes, identities, and mental models and how those influence the ways in which they leverage the power they wield to make change.

Disseminating Learnings from the C-Suite Throughout an Organization

Tucker-Seeley asked the panelists for their thoughts on how to take the learnings that C-suite leaders are gaining and apply them throughout their organizations, particularly to the people who interact with patients and community members. Mantey replied that there are no easy answers to this challenge, in part because the necessary conversations are hard and can be painful or because staff do not know how to change without affecting their workflow. Her suggestion was for leadership to allow staff to have room to explore, try something new, and propose different ways of going about their work. Embracing disruption, though hard, must happen as part of transforming the nation’s institutions, she said.

Manchanda said that institutional change is about reallocating power and resources. He noted that many examples of successful transformation require evolving and understanding what leadership means when having people organize around the power they have. There are many examples, he said, of C-suite leaders successfully navigating formal and informal modes of power and creating spaces for people to organize around DEI and health equity. “New forms of organizing power are necessary to be able to reallocate power and resources,” he said.

Abner said that her organization has embedded specific competencies in job descriptions for senior leadership roles and not just those dealing specifically with DEI and health equity. These requirements include understanding marginalized groups and having the ability to bring teams of people from different backgrounds together and support them. She said that unionized staff often feel that they are treated like a marginalized group within an organization, making it imperative that programs reach these employees. Abner also commented on the importance of holding leaders accountable using specific measures. One promising development she has experienced over the past 10 years is having more leaders from all backgrounds coming to her to ask how they can be equitable leaders.

Tucker-Seeley commented how great a feeling it is to see learnings translated into action throughout an organization, which reduces the burden on the chief health equity officer to be the sole voice for transformation. He then asked the panelists to talk about how important it is to lay out a pathway for people so that they understand the modifiable factors their institution can address to deliver health equity. Manchanda said that the health equity leaders his organization works with are dealing with a patchwork of programs and struggling to create a manageable portfolio with specific goals and several diverse, multilevel interventions they can deploy over different time cycles and value propositions. Moving from a patchwork of programs to a strategic portfolio is a huge step toward

demonstrating value and aligning with business goals in a way that is not defined by a financial return for every single health equity intervention, he added.

Abner said that her organization’s approach is to use data to help advance how its leaders think about inequities. Her team works on and owns patient data from across the eight hospitals in the organization’s system and uses data analytics to examine interventions and steps to take once a disparity is identified. The important factor, she said, is having uniform data across the health system and then teaching staff how to use those data to identify disparities and make changes to address them.

Mantey cautioned against making perfection be the enemy of good. “Knowing where you are starting from, the disparity you are trying to address, the goals you have are important, but you are not alone as a leader,” she said. “You have other stakeholders, rank-and-file staff, and passionate committee members coming with their ideas and strategies,” she added. Mantey said that while what the final result will look like is unknown, charging folks with making change and providing them with the proper resources will produce movement to an equitable state. She also noted the importance of having data to show whether a program is working in the community and improving health equity or how community members feel about the health system.

Manchanda added that combining data with geospatial intelligence can help organizations understand how structural violence and racism are spatialized in the communities they serve and help them connect social determinants and social needs with what is happening in health care. “It is remarkable to me how many health care organizations participating in health equity work do not analyze by place even though we have the information,” Manchanda said.

Working with the Community

When asked by an audience member how to engage community members in a meaningful way but avoid delegating implementation and accountability to them, Abner said it is important to have a focus and a base within the community and to use that to enable the community members to state what their concerns are. Abner added that organizational commitment and ownership are important, too, as is supporting local community organizations. One issue she has encountered is that some workers do not want to go into and engage with the community. She noted that while she loves that part of her health equity work, she is getting others in the organization to help reach the community instead of doing it alone. Her office has developed a system for tracking these activities to show how often the organization is showing up in the com-

munity. Mantey added that community members need to know who in an organization they need to approach to address a health equity issue.

Manchanda wondered if it would be possible to look over the next five years to see if there is a difference in the quality and the effectiveness of health equity work depending on the level of community-centered governance. “There is a unique opportunity to evaluate the extent to which community-centered governance creates the environments and the accountability to be able to drive long-term sustainable impact on health equity,” he said.

One challenge that he sees, Manchanda said, is getting institutions that have had success working on DEI and health equity together to create an ecosystem of health equity and help influence and dismantle the social policies that put people in the community in harm’s way. “We have an opportunity to define the ways our portfolios strengthen ecosystems as we are narrowing equity gaps for certain patient populations,” he said. “We can start to define clear strategies with clear value propositions and clear outcomes that strengthen ecosystems.” His point was that no one organization can move the needle on health equity within a community, let alone the nation. The only way to sustain progress, he said, is by organizing the community. Abner said that for health equity leaders, the key is to show up, be authentic and truthful, and build networks in the community and across institutions to be influencers of this transformative work.

This page intentionally left blank.