Effective Communication with the General Public About Scientific Research That Requires the Care and Use of Animals: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: Openness in Communication: Principles, Experiences, and Considerations

Openness in Communication: Principles, Experiences, and Considerations

Participants explored various facets of openness in communication with the public in a series of sessions on the workshop’s second day. Speakers reflected on lessons from interactions with activists; shared resources that can help scientists discuss their work effectively with the public; and discussed opportunities for scientists to effectively respond to misinformation or attacks, work to build trust, and overcome roadblocks to facilitate greater openness.

U.S. ANIMAL RESEARCH OPENNESS INITIATIVE AND SHARING OUR EXPERIENCES

Nicole Navratil, Sterling Biomedical Resources, discussed the value of openness broadly and highlighted the U.S. Animal Research Openness (USARO) Initiative resources. On the premise that fundamental basic science discoveries will not occur and critical medical needs will go unmet without public understanding and support for research with animals, academic scientists, industry researchers, animal breeders, and other stakeholders created USARO to encourage institutions to engage in meaningful public conversations about the importance of contributions to science from research with animals. Its three principles of openness—building trust, supporting science, and countering misinformation—can empower scientists and institutional leaders to tell stories about research with animals that can improve the public’s understanding of and support for these important contributions, Navratil said.

USARO identifies institutions that are striving to increase openness; provides them with platforms to share their experiences, advise other institutions, and spread the message of openness; tracks the openness landscape; and measures outcomes and impacts of openness. When institutions join USARO, openness becomes a shared responsibility and can take many forms, such as facility tours, presentations, and educational events for nonscientist staff and the public; presence at community events; press releases and articles promoting research with animals; and opening inspection reports and records.

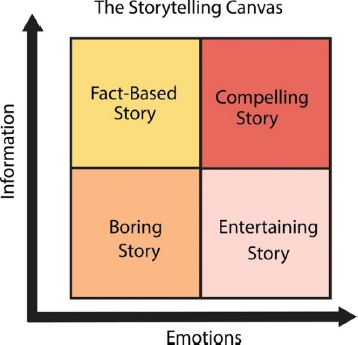

In today’s society, Navratil said, openness has become an expectation—and a competitive advantage—and a lack of it creates distrust. It also enables scientists and research institutions to more effectively contribute to the public narratives around research with animals by communicating the care the animals receive and the important contributions they make, both of which are relevant to how the public views the issue. “We have to pay attention to how we’re viewed, and we have to stop letting somebody else tell that story for us,” said Navratil. However, she cautioned that offering facts alone is not enough. Opinions are often based on emotions, not facts, she said, noting that “we are feeling beings before we are thinking beings,” and it is important to recognize that many people are reticent to engage with ideas that challenge their opinions. To have more effective conversations with the public, she suggested that it can be helpful for scientists to lean into their own emotions, embrace vulnerability, empathy, and compassion; validate the other person’s feelings; and avoid focusing excessively on providing information. Stories that include a balance of information and emotion, rather than facts alone, are generally more compelling and engaging (see Figure 1).

USARO also offers training for conversations with institutional stakeholders. One method, team-building circles, creates a safe environment where staff at all levels—even senior leadership—are invited to share their perspectives and answer pointed questions about their work and areas for improvement. In a discussion following her remarks, Navratil noted that although records-request laws exist to support openness, especially for public institutions, their impact is limited in that they put the onus on the public to seek and request information. By contrast, USARO encourages institutions to be open more proactively, making information and research much easier for the public to access by posting it “front and center” on their

websites and social media channels and facilitating interaction with audiences and communities who are willing to engage. She added that USARO’s website provides information about how different institutions have sought to accomplish this.

Navratil also expanded on the importance of crafting stories that can effectively engage public audiences. Scientists, used to academic writing, tend to present collections of facts, but incorporating creative writing techniques that emphasize emotions and recognize areas of uncertainty can result in a more human, compelling narrative. It is also important to avoid jargon, she added. For example, she suggested avoiding terms, such as “purpose-bred” and “minimizing pain and distress,” that have accepted meanings within scientific communities but may be unfamiliar to or understood differently by the general public. Instead, describing animals as “adjusted to this environment” and “content and happy” is more accessible. In addition, she said that offering information, pausing, and asking the listener whether they have follow-up questions can be an effective technique to ensure that the conversation is a dialogue and not a lecture.

Prompted by a question, Navratil acknowledged that the downside of openness is that it can make information public that, taken out of context, can create negative public perceptions. However, she believes that providing a full, open, and accessible story is the best way to combat misinformation and address controversy.

PANEL DISCUSSION ON CONSIDERATIONS ALONG THE SPECTRUM OF OPENNESS

Planning committee members Paula Clifford, Americans for Medical Progress, and Crystal Johnson, Georgetown University, moderated a panel discussion examining a variety of considerations for institutions and scientists when determining how open to be about research with animals. The panelists were Christine Lattin, Louisiana State University; Jim Newman, Americans for Medical Progress; Wendy Jarrett, Understanding Animal Research; and Eva Maciejewski, Foundation for Biomedical Research.

SOURCE: Shutterstock, copyright 2024.

Opening Remarks on Considerations Along the Spectrum of Openness

Panelists were invited to share their experiences and perspectives in opening comments before engaging in a broader panel discussion.

Lattin, Louisiana State University

Lattin shared her experiences with harassment from animal rights activists opposed to her research on birds. The issue began in 2017, when People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals organized a rally against Lattin and her postdoctoral research, conducted at Yale University, on how wild birds react to captivity (Am, 2017; Chukwu, 2017). Upset, Lattin wanted to defend herself, but Yale advised her to ignore the harassment, likely assuming it would end quickly. However, the negative attention continued to increase, and eventually Lattin reached out to other scientists who had been in similar situations. With their encouragement, she broke her silence. She spoke with reporters, posted on social media, and wrote essays defending her work and research with animals in general (Lattin, 2018; Luntz, 2017).

When Lattin moved to a faculty position at Louisiana State University, she took a more proactive approach to communicating about the nature of her work. She carefully worded her professional web page to remove jargon and add more accessible language on how and why she conducts research with animals, including an FAQ that is now one of her most viewed pages.1 Although her work has continued to attract negative attention, including efforts to obtain her unpublished research, she said that the harassment is now much less threatening than it was, which she attributes to her efforts to make herself and her research more open and available to the public.

Newman, Americans for Medical Progress

Newman described an experience from his time as the director of media relations for the Oregon National Primate Research Center, part of Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU). A small group of animal rights activists had occasionally protested the center, but in August 2000, these actions took a different tone when an activist organization infiltrated the center and publicized its observations, leading to a sustained campaign of much larger and more disruptive protests and personal harassment. Initially, OHSU administration stayed quiet, likely hoping the harassment and allegations would stop on their own. However, after extensive records requests, state legislative challenges, targeted billboards, and other attention-grabbing actions, the administration chose to communicate more openly and clearly, to tell the institution’s own story instead of staying quiet and allowing others to dictate its narrative. This included creating a dedicated communications position focused on research with animals to allow the institution to quickly and accurately respond to accusations or information requests. It also began highlighting the work of staff responsible for animal care, improvements to facilities and practices, and scientific breakthroughs, both internally and externally. Finally, it increased tours and engagement events for the press and the public.

These actions gave the public a better understanding of the center’s work, Newman said, and having the administration’s support also helped to improve staff morale. When the center was infiltrated again a few years later, the disclosures landed in an environment that was very different both internally and externally. Media coverage was much more balanced, and the story evaporated quickly because OHSU administration was open and forthcoming with addressing questions, supporting staff, and rebuking false allegations.

Newman highlighted a few lessons from the experience. When reacting to crises like these, it is extremely helpful for communications staff to have a plan and respond to concerns from the public and their own staff quickly and openly. An effective response also includes involvement across all levels of an organization—from communications to legal to institutional animal care and use committees to leadership—who can strive to be open, available, proactive, and responsive to all audiences, from the general public to legislators. Finally, he emphasized the importance of being open and responsive to internal staff, who care deeply about the animals and often are the most effective ambassadors for communicating with the general public.

___________________

1 See Lattin Lab at Louisiana State University, https://thelattinlab.com (accessed March 13, 2024).

Jarrett, Understanding Animal Research

Jarrett described the UK experience with openness about research with animals. A key feature of the public discourse around this issue has been the 2014 Concordat on Openness on Animal Research Understanding Animal Research (n.d.), of which Jarrett led the development. Jarrett said that it emerged as a direct response to a poll showing that approximately 40 percent of the U.K. population wanted more information on research with animals (Ipsos MORI, 2012). Signatories—which include universities, pharmaceutical companies, research funders, and charities—commit to being more open and proactively providing information to the media and the public. Other regions of the world have established or are developing similar efforts, such as USARO.

Since the concordat, Jarrett noted a significant change in the amount and quality of relevant information that is made available publicly in the United Kingdom. More than 120 organizations participate; their webpages use statistics, images, and videos to document research projects involving animals and the nature of their care. The concordat website also offers virtual lab tours and a yearly report on reducing, refining, and replacing animals in research.

As a result of these efforts, Jarrett said that positive media stories are now more common and UK public acceptance of research with animals has increased (Mendez et al., 2022). Despite some negative campaigns from people opposed to research with animals, the concordat has changed both how organizations respond and how the public reacts, as organizations now publicly defend their work, the public views them as more open, and members of the public view themselves as more informed about research with animals.

Maciejewski, Foundation for Biomedical Research

Maciejewski discussed the role of openness in increasing public understanding and offered practical strategies that scientists can use to enhance openness in positive ways. She said that public polling has found that the U.S. public has a limited understanding of research with animals and noted that people may be exposed to a wide range of media coverage on the topic, various public educational campaigns in support of it, and negative campaigns that criticize it, often focusing on perceived animal welfare violations (FBR, 2022).

Openness strategies can combat these negative campaigns and increase public trust when the information presented is scientifically and factually accurate, evidence based, and noninflammatory, Maciejewski stated. As other speakers had noted, openness creates a relationship between scientists and the media that is proactive rather than reactive, which can lead to a more balanced tone in stories, help build public confidence in research with animals, and foster collaboration among scientists.

She emphasized that trust is a two-way street: “the openness approach is a way to foster and build trust—you can’t earn trust if you don’t give trust.” When approached by journalists, she suggested that scientists investigate the reporter’s publications and adjust their communication strategy accordingly. To avoid making mistakes and communicate more effectively, it is also helpful for scientists to stay aware of public opinion and media trends; anticipate criticism, misinformation campaigns, and pushback; and collaborate with experts to find their own voice.

Panel Discussion

In an open panel discussion, participants delved deeper into the origins and impacts of the UK concordat, roadblocks to openness, and communicating with passion.

Concordat Origins and Impacts

Jarrett explained that one motivation behind the concordat was that many organizations were hesitant to be the only one willing to speak more openly and thus seek safety in numbers. Signatories’ willingness

to join together was rewarded, as they have not suffered negative impacts as a result of their participation. The agreement was made public only after a sufficient number of informal commitments were in place, and more than 90 percent of UK institutions at which research is conducted with animals have signed on. Jarrett added that nonsignatories are now more likely to be questioned and targeted than signatories are, and the signatories have also benefited from ongoing collective efforts to improve their strategies for facilitating openness.

Asked about funding for the concordat, Jarrett clarified that the agreement was initially established with a grant from the Wellcome Trust and also receives funding from the UK Research and Innovation Council. Organizations cover their own costs of joining and related activities, although Jarrett noted that these costs are kept low to minimize barriers to participation. She said that despite some challenges and protests against research with animals, organizations are now better equipped to tell their side of the story and counter the false imagery and language often put out by opponents.

Navratil stated that USARO hopes to have a similar U.S. impact, although she acknowledged that convincing institutional leadership can be a challenge. Clifford agreed that creating safety in numbers can help institutions feel less vulnerable in taking such steps. Newman noted that when OHSU decided to take a more open approach, it discovered that the public was curious about, and ultimately appreciated, its research. Institutions may believe that they are playing it safe by keeping quiet, he said, but doing so can actually create an atmosphere of secrecy and suspicion, especially when much of the research is already publicly available. “The question,” he said, “is do you want to allow those who are opposed to take all that information and tell their own story, or are you interested in telling the story yourself?”

Overcoming Roadblocks to Openness

The fear of harassment is often one of the biggest roadblocks to openness, Lattin said. However, she said that it is important for scientists to recognize that the public often has access to a great deal of information about their work, whether or not they speak publicly about it. She said that, by welcoming opportunities to talk about their research with animals, scientists can become their own best advocates. “If not you, then who?” she asked. Furthermore, she said that communicating about the benefits of their work is part of a scientist’s obligation to society, especially if the research is publicly funded: “Animal research is a privilege and not a right, and part of our responsibility in doing this work with animals is to communicate about it.”

Newman noted that state and federal open-records laws create a high level of openness, especially for public universities. However, recognizing that openness can also expose individuals to risks of attack, OHSU successfully petitioned the state legislature for an exemption allowing it to redact certain personal information from certain records to protect research staff who work with animals from targeted harassment while still maintaining openness about the treatment of animals and the research process. Maciejewski noted that some institutions may lack the resources to support large openness initiatives, and another participant added that it is also important to be aware of any restrictions on discussing research funding or classified work.

Communicating with Passion

In response to a question about communication strategies, Navratil added that scientists can communicate more effectively with the public if they are able to convey not only their compassion but also their passion for research. Although it takes practice to talk comfortably about a difficult subject, letting passion show can be both contagious and convincing. Removing institutional constraints can help scientists speak more freely, she added, recognizing that scientists who speak with genuine enthusiasm and excitement can connect better with the public.