Preparing the Future Workforce in Drug Research and Development: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 4 Overcoming Barriers to Progress

4

Overcoming Barriers to Progress

Highlights of Key Points Made by Individual Speakers

- To build a R&D workforce that is representative of the population, it will be necessary to make significant changes in approaches to recruitment, retention, and support. (August)

- The current workforce is fit-for-purpose for 2010, so it will take efforts to expand and build a more diverse workforce that is fit-for-purpose for 2030. (Hernandez)

- It is critical to prepare the “soil”—people, practices, and resources—when growing a more diverse and inclusive workforce. (Schor)

- Diversifying the student body can be accomplished with a concerted effort that includes support from leadership, scholarships and financial aid, efforts to retain and support students, and policies and practices that facilitate progress. (Fancher)

This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

MYTHS IN STEM

Avery August, a professor of immunology and deputy provost at Cornell University, opened the workshop session by exploring the barriers to progress in achieving a more person-centered, culturally aware drug research and development (R&D) workforce. He and other session participants shared lessons learned from current efforts and spoke about practices that could be more broadly applied. The current state of affairs, August said, is that there is “significant bias” with regard to certain approaches used in drug development. For example, if an artificial intelligence tool uses data that are “not diverse and broadly representative,” the results will be biased in the direction of the data. The future workforce, he said, needs to be more diverse, more person-centered, and more culturally aware to ensure that data and decisions reflect the diversity of the population.

August discussed several prevalent myths about diversity in science. First, there is a myth that populations that are underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) are not interested in the STEM field. To the contrary, he said, studies have found that interest in pursuing STEM-related fields is similar among all groups of high school students (Meyers et al., 2018). However, not all students have equal access to the information and resources needed to participate in those careers. Another myth, August said, is that colleges are not producing STEM degrees among those populations that are underrepresented in STEM. To the contrary, data show that significant numbers of Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous students are receiving STEM degrees. Increases in the numbers of STEM degree recipients between 2008 and 2018 were similar between the general population and minority populations (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2023). For example, there was an overall 33 percent increase in STEM doctorate degree recipients; Hispanic recipients increased by 37 percent, and Black recipients by 25 percent (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2023). August added that the Black participation rate is lagging behind Hispanics and that, despite progress, there are still differences among groups.

While interest in STEM is similar among racial and ethnic groups and there has been a proportionate increase in minority STEM degree recipients, August stated that “we need to do more.” To achieve a STEM workforce that is reflective of the population, the participation rate of minority students needs to be significantly increased. August said that “establishing a R&D drug workforce is not going to be achieved using our current workforce model.” There needs to be “significant changes in how we train the biomedical workforce so that we can prepare for a future drug force that is more diverse and that can support a broader diversity of our population,” he said.

Another persistent myth is that the drug discovery process is neutral, so a diverse workforce is not required for equitable outcomes. August told an anecdote to demonstrate the falsity of this view. An electroencephalogram (EEG) is a test that measures brain activity. For the majority of the population, electrodes placed on the scalp work well. However, for Black patients with different hair texture, the traditional way of placing electrodes may not get a proper reading. In response to this challenge, an African American student in the College of Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University has developed an approach to allow accurate EEG readings for individuals with different hair (Etienne et al., 2020). This is an example, August said, of how a workforce that reflects the population is more likely to be able to understand and address the needs of that population.

Recruiting diverse students into the STEM workforce pipeline is important, August said, but attention must also be paid to the experiences that they have throughout the training process. Learners make several decisions throughout the career pathway about which degrees and careers to pursue, and their experiences at each stage affect the decisions they make. August drew an analogy to a bacteria culture on a plate without supportive nutrients. Similar to how the culture will not grow in this environment; students will not grow in an environment that is not supportive (Montgomery, 2020). If institutions fail to retain students who are in the STEM pipeline, progress will not be made on building an equitable workforce. Students who come from underrepresented backgrounds may benefit from multiple types of supports, including instrumental support, psychosocial support, and friends and family support (Estrada et al., 2019). In graduate school, students from underrepresented backgrounds report similar levels of feeling that they belong to an intellectual community but less of a sense of belonging to a social community (Gibbs and Griffin, 2013). August contended that supports help students to persist, continue with training, and eventually become practitioners in STEM. Educational institutions need to consider not just the content that students are learning, but the environment they create and resources for mental health offered, he said.

August told workshop participants about his work chairing the steering committee of a gathering called the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minoritized Scientists1 (ABRCMS). ABRCMS brings together a “vibrant scientific community” to support students and scientists from minoritized groups, he said. There is a wide range of programming focused around the annual meeting, but also year-round activities available to scientists across the country. At its core, August said, ABRCMS is a scientific meeting scaffolded with significant support, mentoring, and

___________________

1 For more information, see https://www.abrcms.org/ (accessed February 26, 2024).

programs to aid scientists in their career journey. Participants come from across the career spectrum, including investigators, leaders, trainees, postdocs, graduate students, and undergraduate students. ABRCMS offers an opportunity to “reach students where they are,” August said, and gives participants exposure to a broad range of scientific careers. ABRCMS is in the process of building a leadership academy to continue to support and provide mentoring and sponsorship for students to become leaders in the R&D workforce.

A DIVERSE MEDICAL STUDENT BODY

Tonya Fancher, the vice chair of workforce diversity and associate dean of workforce innovation and education quality improvement at the University of California (UC), Davis, told workshop participants about her work to recruit, train, and retain a diverse group of medical students to meet the needs of California. She began with some statistics about the diversity of the nation’s medical school students:

- About 30 percent of medical students have a parent who is a physician (NRMP, 2023).

- The percentage of students who are Native American or Alaska Native is about 1 percent (NRMP, 2023).

- Half of medical students come from families in the top quintile of income; 75 percent come from families in the top two quintiles (Youngclaus and Roskovensky, 2018).

- The percentage of medical students who self-identify as having a disability rose from 2.8 percent in 2015 to 5.8 percent in 2021 (NRMP, 2023); in comparison, 18.7 percent of the U.S. population self-identifies as having a disability (Waliany, 2016).

Taken together, Fancher said, these statistics demonstrate the need to diversify the medical student body and to think about diversity broadly to include characteristics such as income, disability, and language. Both recruitment and retention are a challenge for diversifying the student body, and students leave training programs at different rates. For example, one study found that students who are Black, Hispanic, or multiracial were more likely to leave an M.D.-Ph.D. program than were White or Asian students (Nguyen et al., 2023).

UC Davis, Fancher said, is the northernmost UC school and is surrounded by rural communities. The areas around UC Davis have poorer health outcomes, fewer primary care physicians, and lower life expectancy than more affluent areas. This presents an opportunity for UC Davis

to “look outside the window” and get involved, she said. UC Davis has developed a number of medical school pathways to reflect the community’s needs. The school not only works to recruit students from diverse communities, but also has created cohorts within the school for students to find support and build their professional and social identities. Nearly 40 percent of medical students at the school are involved in one of these pathways, she said (Henderson et al., 2023). Fancher provided details on three of the programs:

- The Accelerated 3-year M.D. to Primary Care2 program recruits students from underrepresented communities and trains them in 3 years to enter internal or family medicine. There is a major shortage of primary care physicians, Fancher noted, and this program trims the “fat” from medical training and focuses only on primary care. The students entering this program tend to be older and have lower grades and entrance exam scores than traditional students, she said, but they perform well in the program.

- The Community College to Medical School (Avenue M)3 program creates a clear pathway from community college to a 4-year college to medical school. The diversity of community colleges reflects the diversity of the community, Fancher said, yet medical schools have traditionally looked poorly upon enrollment in community colleges. Avenue M seeks to change this perspective and to create opportunities for these students.

- The Tribal Health PRIME4 program works to recruit students from American Indian, Native American, Alaska Native, and Tribal Communities. This program is a collaboration across the West Coast, she said, and reduces barriers to education by creating pathways for students such as conditional acceptance to medical school after completion of a post-baccalaureate program.

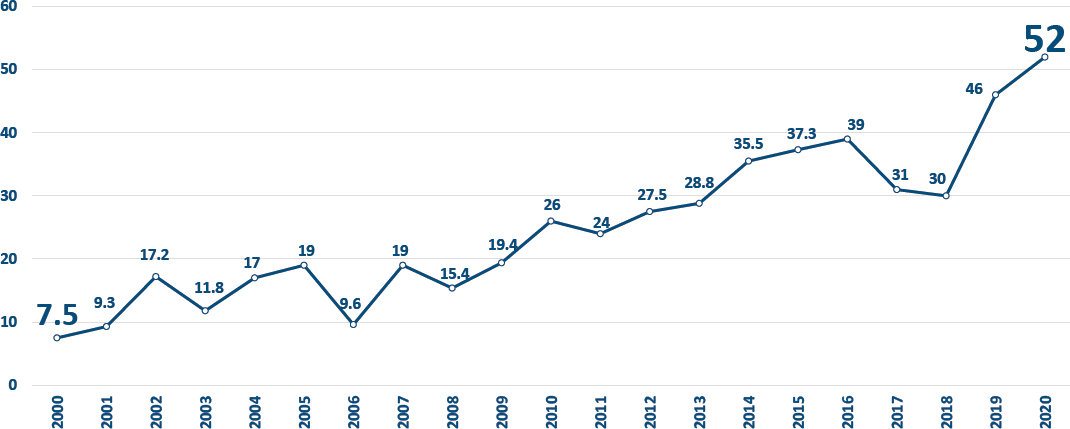

These programs and other efforts by UC Davis have made a significant impact on the diversity of the student body. Students’ families are distributed widely on the income spectrum, and the percentage of students from a community underrepresented in medicine has risen from 7.5 percent in 2000 to 52 percent in 2020 (Figure 4-1). The student body

___________________

2 For more information, see https://health.ucdavis.edu/mdprogram/ACE-PC/about.html (accessed February 26, 2024).

3 For more information, see https://health.ucdavis.edu/news/headlines/uc-davis-creates-snew-pathway-to-medical-school-that-starts-in-community-college/2022/06 (accessed February 26, 2024).

4 For more information, see https://health.ucdavis.edu/mdprogram/tribal-health/index.html (accessed February 26, 2024).

NOTE: Includes students who identify as American Indian/Alaskan Native, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, Native Hawaiian, or Filipino.

SOURCE: As presented by Tonya Fancher on October 16, 2023; Henderson et al. (2021). AMA Journal of Ethics, Copyright 2021, American Medical Association. All rights reserved. The AMA Journal of Ethics® is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

at UC Davis is increasingly starting to look more like the population of California, Fancher said.

Fancher identified several factors that have benefited the efforts to diversify the student body. First, there was a focus on admissions as well as retention. Second, there was support from leaders at the highest levels. Third, scholarships and financial aid made medical school accessible to a more diverse group of students, in particular those enrolled in a federally recognized tribe. Finally, policies, practices, and partnerships helped to facilitate progress such as policies on grade equity and accessible accommodations.

BARRIERS, CHALLENGES, AND POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

Perdita Taylor-Zapata, the program lead for the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act Clinical Program at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, moderated a discussion among panelists and workshop participants.

Leveraging Early Engagement

Taylor-Zapata began by asking panelists to identify the main barriers related to developing a more person-centered and culturally aware workforce along with potential approaches to address these challenges. Adrian Hernandez, the executive director of the Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI), responded to the question by sharing a “tale of two cities.” DCRI, he said, operates clinical trials across the United States and around the world, allowing for flexibility in both the makeup of the workforce and the work environment. The other “city,” Duke Health, is a health care system that operates within the confines of the local community and has had major challenges with workforce turnover. These two “cities” have different challenges, Hernandez said, and require different solutions. However, Hernandez said that one common challenge is that “sometimes we start too late” in engaging and recruiting people to join the workforce. Hernandez’s colleagues started a program that reaches out to high school students who are interested in science or health but not committed to a specific career. This is a small program but should be expanded, he said.

Nina Schor, the deputy director for intramural research in the Office of the Director at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), highlighted an NIH program that brings high school girls together with working scientists to learn more about STEM careers. The idea for the program—-

called Girls in Navigating Neuroscience5—actually came from the students themselves, Schor said. A group of high school students in Prince Georges County, Maryland, most of whom are from underrepresented communities, asked the NIH for opportunities to learn. The girls travel to NIH to tour laboratories and see demonstrations, and scientists—from investigators to clinicians—come to the students to talk about their work. Schor said that both the students and the scientists enjoy the program immensely and that the scientists have learned “so much” from the young women.

Following up on Schor’s description of Girls Navigating Neuroscience, Taylor-Zapata said that these types of programs designed to expose young people to STEM can be beneficial for both parties. She asked panelists how they have structured their student outreach programs to ensure a mutual exchange of value between scientists and students. August replied that ABRCMS holds a “full-fledged scientific meeting” where high school students are invited to attend. The student presenters—who are largely undergraduate and graduate students—get to experience the excitement of high schoolers who are eager to learn more about their work. It is powerful to see this exchange, August said, and he suggested that all scientific meetings should have sessions in which the local community is invited to attend.

Changing the Existing Culture

Schor contended that to build a workforce fit for 2030, it will be necessary to change the culture of the existing drug development community to one that rapidly brings in new people and makes them feel part of the community. Because humans do not instantly accommodate change, it will be necessary to change the culture through deliberate and thoughtful actions, Schor said. Some of this needed culture change, she continued, is as simple as raising awareness about STEM careers outside of medicine or academia, highlighting opportunities for careers in drug development, and stressing the importance of having a diverse workforce that represents the community. Schor told workshop participants about several efforts at NIH related to building community. First, there are new grant mechanisms directed at cohort hiring and recruitment6—that is, bringing people in as part of a group. It can be “incredibly lonely” to be the only person of a certain type, Schor said, even when fellow students and colleagues are welcoming. Cohort hiring gives individuals from under-

___________________

5 For more information, see https://nihrecord.nih.gov/2019/08/09/ninds-program-helps-stem-students-navigate-neuroscience (accessed February 26, 2024).

6 For more information, see https://diversity.nih.gov/disseminate/blog/2020-12-08-support-inclusive-excellence-through-cohort-hiring-funding (accessed April 4, 2024).

represented groups an opportunity to belong and to support each other. However, simply bringing in people from underrepresented groups will not necessarily change the existing culture, Schor said. The Distinguished Scholars Program7 is directed at this challenge. The program, funded centrally from the Office of the Director, provides funds for individuals who “have a track record of proven interest and passion for welcoming people who would ordinarily not be part of their laboratory or clinic setting,” Schor said. The program defines diversity as broadly as it can be defined. While it is often related to gender or racial and ethnic diversity, there are also funded individuals who have brought together other diverse groups, such as laboratory teams that include people from biology, engineering, philosophy, and ethics, to create an intellectually diverse environment.

August agreed that creating a diverse and inclusive environment requires more than just recruiting diverse individuals to join and said that Cornell has several tools for preparing the community to welcome new faculty. Faculty at Cornell were interviewed about their experiences coming into the institution; this information was turned into a “play” that actors and actresses put on for the department. August reported that this raised awareness among faculty that everyone “comes into this place feeling a little different.” This approach also can prompt faculty to think about what it is like for community members to enter their space and vice versa. Overall, it is a way to have conversations about cultural differences that might prevent people from participating, he said.

Another approach for expanding and diversifying the workforce, Hernandez said, is to reach into underserved communities to find people who are “mission-oriented and passionate about what they do.” It is important to think outside the traditional models of clinical research and expand the idea of who can do the work, he said. For example, instead of hiring clinical research associates specifically, other professionals such as social workers could be trained and brought into the fold. Expanding the idea of who makes up the workforce is essential because “all of our job descriptions . . . were fit for purpose for 2010, not for 2030,” a structural barrier that needs to be addressed, he said.

Schor said that bringing people into an environment to increase diversity “without getting the soil ready for that seed to take root” is an “enormous mistake.” She told a story about an experience she had as the chair of pediatrics at University of Rochester. The residency program had accepted a student who was deaf, and the student asked Schor how he could help prepare both the faculty and his fellow residents for his arrival. His goals were to make it comfortable for faculty and residents, while also

___________________

7 For more information, see https://diversity.nih.gov/act/NIH-distinguished-scholars-program (accessed February 27, 2024).

carrying out his responsibilities as a resident himself. The faculty held a meeting with the resident where he and a sign language interpreter presented the “rules of the game” that were necessary for him to be on the team. He talked about his disability and made faculty members aware of what they needed to do to communicate (e.g., tap him on the shoulder to get attention). This engagement was critically important to making both the new entrant and the existing members of the community feel comfortable, Schor said. August added that the Rochester Bridges to the Doctorate, a collaboration between the National Technical Institute for the Deaf at the Rochester Institute of Technology and the University of Rochester,8 is developing a handbook for training deaf and hard-of-hearing STEM students. He said that it could be helpful for a convening body to develop and disseminate broad approaches for bringing diverse individuals into an environment as this would have the effect of normalizing the process, while providing institutions with needed resources.

Promoting Team Science

Taylor-Zapata introduced the idea of “team science,” in which people from across the clinical research pathway are communicating and collaborating, from investigators to social workers to patients. Hernandez agreed that this is a critical issue and said that the disciplines considered to be part of the clinical research team have rapidly expanded. There is a risk, he said, that the expertise of super-specialized professionals will not be fully taken advantage of if others are not aware of their work or how to access it. For example, a team can have the greatest data scientists, but if other team members do not know the capabilities or methods of the data scientists, their potential may not be fully realized. The same is true for other specialties such as social science, public health, and others, Hernandez said. Leaders are in an ideal position to ensure that the right people connect, Schor said; in fact, it is their job to “create excuses and venues to bring people together.” As a person with a 30,000-foot view, a leader can see the entire landscape and who should be communicating and collaborating. While the importance of bringing together diverse perspectives and expertise cannot be overstated, Hernandez said, people can be afraid of taking this risk. It is easier to repeat the same process to get the next grant or the next regulatory approval than to reach out to new people who may have different ideas about how things should be done. This inertia has been institutionalized into both academia and industry, he said. Schor agreed that it can be difficult to bring people together and

___________________

8 For more information, see https://www.rit.edu/ntid/deafscientists (accessed February 26, 2024).

said that while incentives can work initially, it is important that the team members eventually buy in to the collaborative process. Without buy-in and motivation from team members, Schor said, ideas and programs “die on the vine.” In order to buy into the collaboration, it is critical that team members feel valued and heard.

Hernandez said that in addition to working with other team members, people in the clinical research workforce need hands-on experience with patients or communities to develop cross-cultural competence. For example, Hernandez said that he used to take statisticians on rounds so that they could see a clinical trial from the perspective of a patient with a health condition who was trying to get better. Direct patient contact establishes an emotional bond and makes it “really visceral,” Hernandez said. Expanding these types of exposures to everyone on the clinical research team could make a big difference in creating a more person-centered workforce and, by extension, person-centered research, he said. For example, researchers who have based their research proposal on experiences and conversations with the community would be well positioned to talk to the institutional review board (IRB) about why they made certain choices and why these are the best choices for this community. Fancher agreed and said that there should be opportunities to bring scientists into clinics to meet the patients where they are and to represent and discuss the research opportunities available to patients.

Navigating Affirmative Action

Given the legal barriers to affirmative action—including Proposition 2099 in California and the 2023 Supreme Court decision that struck down affirmative action in college admissions10—Winn asked panelists how institutions can achieve a diverse student body without running afoul of the law. Fancher replied that when Proposition 209 went into place in 1997, there was a massive reduction in the number of students of color and low-income students of color enrolled in California universities (Bleemer, 2020). The UC medical school system has addressed this issue by focusing on the need to care for specific communities through, for example, its PRIME programs. Students who are interested in serving certain communities tend to be from those communities, so while the program criteria do not include race, they have the effect of producing a more diverse student body.

___________________

9 Affirmative Action Initiative, California Proposition 209. (1996) https://www.ucop.edu/academic-affairs/prop-209/index.html (accessed February 26, 2024).

10 Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College. 600 U.S. 181 (2022). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/20-1199_hgdj.pdf (accessed February 26, 2024).

August cautioned that it is important to not overreach in the interpretation of the Supreme Court’s ruling. The ruling does not prohibit the types of programs that have been discussed at the workshop, such as outreach to specific communities. August said that there are legal and defensible approaches for reaching out to underrepresented communities and diversifying the student population. Schor agreed that there are ways to improve diversity without violating anti-affirmative action rules. At NIH, the focus is put on recruiting not individuals who are members of underrepresented minorities, but individuals who have demonstrated a dedication to diversifying the workforce or bringing diverse perspectives to the science. While some of these individuals are from underrepresented groups, their racial or ethnic identity is not a factor in recruitment or selection. Another valid approach for improving diversity is casting a wide net for applicants. The more broadly you reach out, Schor said, the higher the likelihood that someone from an underrepresented group will be among the finalists.

Partnering with Community Members

Workshop participant Keith Norris, a professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, asked panelists about having community members serve in faculty positions as a way of engaging more deeply with the community. He said that there are many individuals who have a lot of skills but not the formal education normally required for faculty. Norris stressed that bringing these “PhDs of the sidewalk” into a formal, extended relationship with the institution can help change the consciousness of people within the institution and lead to transformative change outside the institution. Hernandez replied that while community members are being brought into institutions as advisors, it is more difficult to give them a formal role. There is institutional resistance, particularly among lawyers, so every step of the process needs to change, Hernandez said. August agreed that the challenge to bringing in community members in a formal way is the risk aversiveness of those responsible for making the arrangements. There is a need to look at the policies and practices that are preventing these partnerships from being realized and make changes where possible, August said.

Supporting Sustainability

A workshop participant noted that some of the programs and efforts described at the workshop are the result of one leader’s work. She asked how these programs can be made sustainable even if the leader moves on and how programs might be scaled up to make a broader impact. Schor

responded that she is motivated in her work by leaving a legacy—creating something that did not exist and ensuring that it remains after she is gone. Because of this perspective, Schor said that she thinks about sustainability from the very beginning of an idea for a program. She relies on a “coalition of the willing” who are inspired by the idea and willing to do the work to implement and sustain it. Sustainability requires mentoring the people who will keep it going and getting buy-in from leaders by “selling it as a value added.” Schor joked that the programs that build opportunities for people “don’t have impact factors” and will not count for much on a cover letter, so the people who do this work are those who are passionate about it. Bryant-Friedrich added that institutions, such as universities, are based in policies, processes, and procedures; if a program is embedded in these policies, processes, and procedures, it will “outlive us.”

This page intentionally left blank.