Advancing Research on Chronic Conditions in Women (2024)

Chapter: 6 Chronic Conditions That Predominantly Impact or Affect Women Differently

6

Chronic Conditions That Predominantly Impact or Affect Women Differently

This chapter describes the research progress on and advances in understanding chronic conditions present in both women and men that predominantly impact or affect women differently. As mentioned in Chapter 1, the committee selected certain chronic conditions to highlight to provide an overview of the evidence base and research gaps around them. This chapter covers 16 chronic conditions involving mental health, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), cardiometabolic disorders, pain disorder, autoimmune disorders, neurocognitive disorders, and musculoskeletal conditions. Chapter 4 provided data on the impact of select chronic conditions. This chapter highlights the specific role of biological factors, with specific emphasis on estrogens, sex chromosome effects, and influences of the maternal in utero environment, in the development of the disease or condition; emerging differences in how these disorders and conditions present themselves; diagnosis, treatment, and management in women; disparities by racial and ethnic groups and sexual orientation in terms of effects on susceptibility and outcomes; and research gaps.

DEPRESSION

Depression is more common in women, affecting them across the life course and causing significant morbidity and mortality (Bromet et al., 2011; Kessler et al., 1993). This report primarily discusses major depressive disorder (MDD), with some mention of postpartum depression (PPD) and hormonal-associated depression, which includes premenstrual dysphoric

disorder (PMDD)/premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and perimenopausal depression. Differences in the prevalence and effects of depression are likely related to biological, environmental, and societal factors (Yuan et al., 2023). It is also associated with developing other chronic conditions in women, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD); adverse cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and death; and post-stroke depression, including greater severity, poorer neurological outcomes, increased risk of stroke recurrence, and mortality (O’Neal, 2023; Sibolt et al., 2013; Volz et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2019). The co-occurrence of three major chronic diseases—MDD, CVD, and AD—has a significant effect on women (Goldstein et al., 2021).

Biological Factors

Research has yet to fully elucidate the biological mechanisms underlying the susceptibility of women to depression. Several lines of evidence indicate roles for the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin, and dopamine neurotransmitter systems and the stress-responsive hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis in depression. Studies also show that female gonadal hormones, such as estrogens, and sex chromosome effects modulate the function of these neural systems, which may partly explain why women are more likely to experience depression.

Sex Chromosome Effects

In contrast to the plethora of evidence supporting a role for gonadal hormones in modulating mechanisms that lead to depression, limited evidence shows that sex chromosomal genes play a role in women. One study demonstrated that genetic polymorphisms1 on the X chromosome influence the expression levels of three proteins expressed in GABAergic neurons—somatostatin, a hormone that affects neurotransmission, and two enzymes involved in the synthesis of the neurotransmitter glutamate (Seney et al., 2013a). This study also found that women with depression have significantly lower levels of somatostatin in the brain compared to men with depression. With studies showing less GABA-mediated inhibition of neural activity in depression (Luscher et al., 2011; Sanacora et al., 1999; Sequeira et al., 2009), sex chromosome genes can influence GABAergic neural activity by regulating protein expression in GABAergic neurons. Experiments using the Four Core Genotypes (FCG) mouse model, which decouples sex chromosome and gonadal hormone effects (see Chapter 2),

___________________

1 Polymorphisms are two or more variations of the same gene or protein that occur among different individuals or populations.

also support this premise, demonstrating that sex chromosome effects regulate expression of genes related to GABA and the serotonergic and dopaminergic neurotransmitter systems that also modulate depression (Seney et al., 2013b).

The Effects of Estrogens

The menstrual cycle plays an etiological role in depression (Albert, 2015). Fluctuating sex hormone levels are linked to changes in brain morphology, function, and neurochemistry (Kundakovic and Rocks, 2022), with dynamic alterations in the epigenome triggering changes in gene expression that mediate these effects (Kundakovic and Rocks, 2022). Research in mice suggests that hormones and genes interact to change the brain structure in a way that results in an increased risk of depression in women (Kundakovic and Rocks, 2022). Evidence also links depression to a loss of synchronization between estrogens and cortisol phases of the reproductive cycle (Butler, 2018). Some studies demonstrate a genetic association between different estrogen receptor (ER) polymorphisms and depression (Li et al., 2022a).

Animal studies show that the ovarian hormone 17β-estradiol regulates neural activity in key subcortical regions in the stress response circuitry linked to MDD (Jacobs et al., 2015). Furthermore, inflammation has been linked to MDD (Haapakoski et al., 2015), and estrogen deficiency is linked to increases in several inflammatory markers (Klein and Flanagan, 2016). These increases may serve as a viable biomarker for identifying the risk of MDD in women. Perimenopausal depression includes complex relationships between hormonal fluctuations and neurotransmitter activity, brain-derived neurotrophic factors, chronic inflammation, and oxidative stress that warrant further study (Liang et al., 2024).

Other Biological Factors and Mechanisms

Cortisol is an anti-inflammatory hormone whose dysregulation can lead to inflammation, which has been implicated in depression and depressive disorders associated with PMS and PMDD (Bannister, 2019). It is released during stress and modulates activity in distinct brain regions, including the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus. Genetic evidence demonstrates sex differences in cortisol receptor expression and suggests an association between MDD in women and a specific polymorphism in a cortisol receptor (Teo et al., 2023).

Another possible mechanism may involve intestinal dysfunction, such as in inflammatory bowel disease. Experiments have demonstrated that chronic stress in female mice can disrupt the intestinal barrier, which can trigger the release of inflammatory molecules that affect neural circuits in the brain

involved in depression (Doney et al., 2024). A recent scoping review noted sex-specific differences in the composition of the gut microbiome and associations with depression severity in patients (Niemela et al., 2024).

The serotonergic system, the primary target of many antidepressant medications, shows differential expression in women and men of neurotransmitter receptors and some transcription factors. This finding may be related to evidence suggesting that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are more effective in treating depression in women (Seney et al., 2022).

A recent meta-analysis confirmed that PPD involves several genes and is at least partially heritable. This analysis also identified a plausible biological pathway involving GABAergic neurons (Guintivano et al., 2023).

The Maternal in Utero Environment

The maternal in utero environment is an important determinant for susceptibility to depression, especially in female offspring. Clinical studies have linked maternal anxiety (Van den Bergh et al., 2008), higher levels of inflammatory markers (Lipner et al., 2024), and infection during pregnancy (Pallier et al., 2022) to depressive symptoms in adolescent female offspring (Lipner et al., 2024; Van den Bergh et al., 2008). Preclinical rodent models have also demonstrated that exposure to maternal stress-induced inflammation led to an enhanced sensitivity to stresses affecting the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis in female offspring (García-Cáceres et al., 2010).

Low birthweight and preterm birth are also related to the maternal in utero environment and considered to reflect fetal well-being during pregnancy (Kim et al., 2015). Research examining these features and their relationship to depression later in life have yielded mixed results. One study found no association, but another study comparing outcomes by sex found that low-birthweight female babies had a greater risk of depression than male babies by the age of 21 years (Alati et al., 2007). A recent analysis of data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) supports the idea that low birthweight or preterm birth is associated with depression in women later in life (Rahalkar et al., 2023).

Specific Risk Factors in Women

Reproductive Milestones

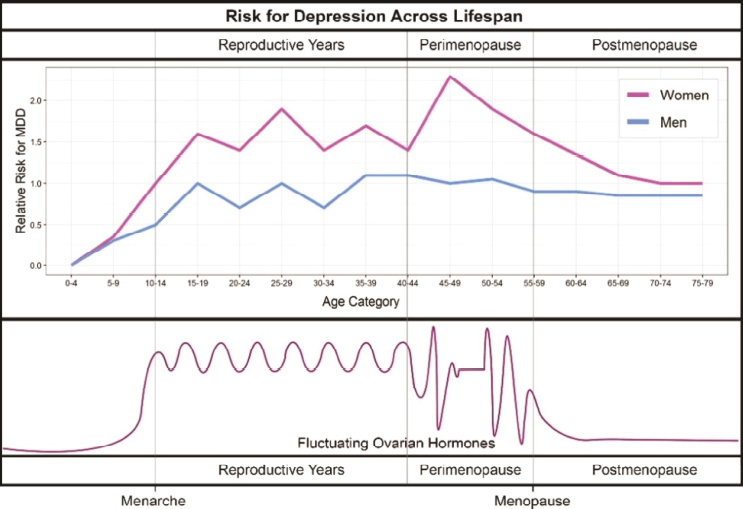

Reproductive milestones serve as windows of vulnerability for depression. Clinical and population-based studies have shown that increased prevalence of depression correlates with hormonal changes in women, particularly during puberty, prior to menstruation, after pregnancy,

at perimenopause, and in menopause, suggesting that changes in hormonal levels may explain the differences in increased prevalence of depression in women (Figure 6-1) (Albert, 2015; Kundakovic and Rocks, 2022). Although girls entering puberty do not necessarily have lower levels of estrogen, fluctuations in those levels may play a role in developing depression at this age (Kundakovic and Rocks, 2022). PMDD is associated with cyclical mood, behavioral, and physical indications that correspond to menstruation, specifically the luteal phase in women. PMDD more commonly affects reproductive aged women but can begin to affect women in teen years (Mishra et al., 2024b). Studies suggest that in PMDD, hormonal patterns are normal but that women may have heightened sensitivity to cyclical variations in estrogen and progesterone levels (Hantsoo and Epperson, 2015; Mishra et al., 2024b).

Recently, a population-based cohort study analyzing data from 264,557 women suggested that the use of hormonal contraceptives, particularly in the first 2 years, is associated with a higher risk of depression, and that use during adolescence may elevate depression risk at older ages (Johansson et al., 2023). This is in contrast with a more recent study

SOURCE: Kundakovic and Rocks, 2022.

in a smaller cohort of 6239 women, which indicated that current hormonal contraceptive use was associated with lower odds of depression (Gawronska et al., 2024). Another study indicated that prior depression associated with hormonal contraceptive use may be linked to a higher likelihood of developing PPD (Larsen et al., 2023). Such findings suggest that individual differences in hormonal sensitivity may influence susceptibility to depression across the life course in some women (Larsen et al., 2023).

The incidence of depression during the menopausal transition increases, even among women who have a history of depression (Maki et al., 2019). Longitudinal studies, such as the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), Penn Ovarian Aging Study, and Seattle Midlife Women’s Study, have shown that perimenopause has an increased likelihood of depressive symptoms and disorders, with likelihood increasing in the late stage of perimenopause as levels of estrogen continue to drop (Maki et al., 2019). Studies have shown that removing the ovaries increases the likelihood of depression (Bräuner et al., 2022; Hassan et al., 2024; Hickey et al., 2021).

Vulnerabilities

Researchers have used the affective, biological, cognitive model of depression, based on a vulnerability-stress model from childhood to adolescence, to examine gender differences in the developing depression (Hyde and Mezulis, 2020). Evidence shows that affective factors, such as temperament differences between boys and girls, may explain gender differences in depression incidence. However, this correlation is based mainly on cross-sectional rather than longitudinal studies (Hyde and Mezulis, 2020). Cognitive vulnerabilities for depression specific in women include negative cognitive style and objectified body consciousness, an internalization of cultural measures about ideal body and appearance. This model also explains how trauma, sexual harassment and abuse, and victimization, which are more prevalent in women, affect the development of mental disorders, including MDD (Hyde and Mezulis, 2020; Klein and Martin, 2021; Krahé and Berger, 2017).

Gender Roles

The association between gender inequalities and depression has been well studied. Negative early-life experiences resulting from gender inequalities have been associated with the increased vulnerability of women to depression (Remes et al., 2021). Studies have shown that women are more likely to experience complex and varied adverse childhood experiences

(ACEs)2 (Finkelhor, 1987; Silverman et al., 1996; Weiss et al., 1999). These exposures are associated with an increased risk of depression (Bochicchio et al., 2024; Weiss et al., 1999), with inflammation implicated as a possible underlying biological mechanism (Iob et al., 2020).

Certain events in the reproductive life cycle, including menarche, pregnancy, the postpartum period, and menopause, come with new responsibilities, role transitions, body image considerations, societal pressures, and hormonal changes and are also associated with higher rates of depression (Albert, 2015; Kundakovic and Rocks, 2022). Developmental changes in a woman’s life-span, starting from childhood, can lead to shifts in gender roles, societal pressures, vulnerability, discrimination, and variable social support, all of which can influence risk of depression in women (Sachs-Ericsson and Ciarlo, 2000; Vafaei et al., 2016). Special considerations that increase risk include ideas around sexuality, conception, and pregnancy, including carrying out a pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and infertility (Salari et al., 2024).

Changes in body appearance and function starting during adolescence can be associated with societal pressures and experiences of sexual and physical vulnerability. Life events related to reproduction in women, such as miscarriage, are associated with significant trauma and grief (Quenby et al., 2021). Evidence suggests that infertility is a susceptibility factor for depression (Salari et al., 2024), although the association is likely complex (Bagade et al., 2023). For example, female hormonal fluctuations are associated with sleep disorders, which are associated with infertility, which is associated with a higher rate of mood disorders (Baker and Lee, 2022).

Reproductive function itself is not a solely biological prospect; feelings and expectations surround it, and in societies in which motherhood is perceived as an essential component of a woman’s identity, women who do not achieve motherhood may experience significant stress (Bagade et al., 2023). Efforts to conceive are unsuccessful for one in four couples worldwide, and infertility is associated with emotional, social, relational, and financial burdens (Warne et al., 2023). One study demonstrated an association between assisted reproductive technology and current and past mental disorder diagnoses, with onset during assisted reproductive technology in up to one-third of patients undergoing it (Warne et al., 2023).

In addition to hormonal fluctuations, women may experience pressures and expectations about body appearance, which can be conflicting and

___________________

2 ACEs are defined as “emotional, sexual, or physical abuse, emotional or physical neglect, and five types of household dysfunction including household substance abuse, a violent home environment, family mental disorders, parental incarceration, and parental separation or divorce” and contribute to the development of risk factors related to morbidity and mortality during adulthood (Christensen et al., 2021; Felitti et al., 1998; Nelson et al., 2017).

contradictory at baseline; pregnancy is associated with noticeable changes, including increased abdominal girth, overall weight gain, and other appearance changes that may be at odds with societal and internalized notions of beauty (Crossland et al., 2023). During pregnancy, women in general are at increased risk for intimate partner violence (IPV). One meta-analysis demonstrated an approximately 9 percent rate of physical and sexual IPV for pregnant women in North America and a nearly 30 percent rate of psychological IPV (Román-Gálvez et al., 2021).

Condition Presentation and Diagnosis

Physical symptoms associated with depression are more common in women and may include fatigue, appetite, weight disturbances, and musculoskeletal pain (Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2020). A major depressive episode during the postpartum period and whether to delineate this from a separate diagnosis of MDD is a point of debate, and the literature varies based on how the investigators defined the postpartum period, epidemiological aspects, and etiology and treatment aspects (Batt et al., 2020). The Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale is the most used screening tool for PPD (Sit and Wisner, 2009). Ideally, these tools should incorporate symptoms unique to postpartum experiences that are not captured in MDD. Evidence is mixed that depression with an onset of 8 weeks postpartum might be different than MDD (Batt et al., 2020).

Although sometimes used interchangeably, perinatal depression is different from PPD. Perinatal depression refers to major or minor depression that starts during pregnancy or up to 12 months postpartum (Batt et al., 2020). The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening and identifying women at increased risk of perinatal depression and referring them to interventions involving counseling (Curry et al., 2019).

As with other psychiatric conditions, research has failed to develop consistent and reliable biomarkers for depression. Certain neurotransmitters and inflammatory markers show promise based on physiological findings in persons with depression, but little is known about how sex affects potential biomarkers (Carvalho Silva et al., 2023; Strawbridge et al., 2017).

Treatment and Management

Early and effective treatment of MDD is crucial to achieve positive outcomes, especially in women, but MDD treatments are underutilized (Goodwin et al., 2022). Studies have shown differential responses to certain types of antidepressants and note that many patients do not respond adequately to traditional antidepressants (Dwyer et al., 2020). Several factors, including body composition and hormonal influences, attenuate the

differential response and pharmacokinetics in women. Studies have shown that women respond better to SSRIs, and men to tricyclic antidepressants (Sramek et al., 2016). However, that increased response to SSRIs appears to be age dependent and is not observed in menopause (LeGates et al., 2019). Other studies have shown more rigorous therapeutic benefits of certain medications after hormone therapy (Parry, 2010). Combination therapy has also demonstrated increased benefit in women over men (Parry, 2010). SSRIs in addition to estrogens are usually more beneficial in improving mood than SSRIs or estrogen treatment alone for major depression, whereas the selective norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitors do not require estrogens to exert their antidepressant effects in menopausal depression (Parry, 2010).

In 2019, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved brexanolone, a naturally occurring molecule that modulates GABAergic activity and is associated with significant improvement in depressive symptoms in adult women with PPD (Epperson et al., 2023). It is administered by intravenous infusion in a health care facility over a 60-hour period. In 2023, FDA approved zuranolone as the first oral drug to treat PPD (FDA, 2023).

Other research findings support the benefits of lifestyle-based approaches and alternative therapies in preventing and managing depressive symptoms. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support how exercise improves depressive symptoms and quality of life (Blumenthal and Rozanski, 2023). Numerous studies also indicate that high-quality sleep (Cui et al., 2024), diets low in proinflammatory foods (Choi et al., 2024; Khosravi et al., 2020; Oddy et al., 2018; Tolkien et al., 2019), and the microbiome composition (Burokas et al., 2017; Radjabzadeh et al., 2022) may prevent or reduce risk and symptoms of depression. Interventions such as strong social support, cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, and mindfulness-based therapies have been shown to improve symptoms (Cui et al., 2024; Li et al., 2022b; Witkiewitz and Bowen, 2010; Yang et al., 2023).

Disparities

Racial and Ethnic Disparities

Many studies have shown that hormonal, biological, and psychosocial factors related to depression vulnerability are exacerbated in adolescent girls identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual (LGBTQIA+) and in certain racial and ethnic groups (Patil et al., 2018). The interplay of gender and racial or ethnic socialization contributes to overall identity formation, which in turn informs coping strategies that are also related to the brain structure and function underlying or protecting against depression (Patil et al., 2018).

Although studies have reported that Black and African American and Hispanic/Latina women report lower levels of depression, symptom presentation differs. A recent narrative synthesis explained that Hispanic/Latina women reported more physical symptoms than White women (Phimphasone-Brady et al., 2023). Furthermore, a systematic review showed that African American women were more likely to express physical symptoms than White women (Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2020). Researchers have not examined symptom presentation in PMS or PMDD in girls and women by race and ethnicity (Phimphasone-Brady et al., 2023).

Lack of culturally competent care for depression also contributes to mental health disparities. For example, women identifying as Black, African American, American Indian, Alaska Native, and Hispanic/Latina placed a strong emphasis on having a health care provider of similar racial and cultural background compared to men of the same racial and ethnic backgrounds (Eken et al., 2021). Several studies support that racial and ethnic concordance between the health care provider and patient may lead to better communication, perceptions of care, and health outcomes, although there are issues of heterogeneity and a lack of quality in the extant evidence (Moore et al., 2023; Shen et al., 2018). Women from these racial and ethnic groups may also experience greater stigma in health care settings, which may be linked to lower access of mental health care and services (Misra et al., 2021). More research specifically focused on women is needed in this area.

Research Gaps

Despite immense strides in acknowledging sex differences in depression and gaining insight as to how sex gonadal hormones, particularly estrogens, heighten the risk in women, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the mechanisms that underlie sex differences. As most experimental animals do not have a menstrual cycle, alternative models are needed to better understand the molecular basis of the intrinsic, hormonally driven vulnerability to depression (Kundakovic and Rocks, 2022). More research is also needed to study sex hormone and gene interactions (Kundakovic and Rocks, 2022) and understand how sex chromosome effects play a part in the pathophysiology of depression in women. Findings from such research can be leveraged to develop diagnostics and treatments that are most efficacious in women.

As with other chronic conditions, inflammation appears to play a mediating role between depression inducing factors and MDD. More research is needed to understand inflammatory triggers for depression in women (e.g., trauma, ACEs, stress) to guide the development of future therapies.

In addition, more studies on the bidirectional influences of depression and other chronic conditions (e.g. AD and CVD), would yield insight into how negative affectivity and rumination could lead to physiological alterations that increase the risk of developing other chronic conditions. The understanding of how depression, including PMDD and PPD, manifests throughout reproductive milestones and across the life course, such as during the menopausal transition, need to be further explored.

A better understanding of how environmental influences or extrinsic factors influence depression in women is needed. Research on external factors affecting mood and depressive symptoms have multiplied in recent decades, and it is important to understand the factors underlying why some individuals are more susceptible. Further research on biopsychosocial resilience factors, such as nutrition/nutrients, microbiome, lifestyle (e.g., exercise), and family/community/medical caregiving support, and how these counter risk factors for depression in women, is important.

More research is needed to develop appropriate screening tools (e.g., questionnaires and biomarkers) that discern the diagnostic features of perinatal depression, PPD, and MDD to better identify women at risk during the reproductive stages and initiate timely interventions. Adapting routine screening tools for use in racially and ethnically diverse women remains paramount, as research has demonstrated racial differences in depression expression and presentation (Salihu et al., 2022). Similarly, research needs to incorporate racial, ethnic, and cultural considerations into clinical trials to treat depression in women at all stages of the life cycle, since racial and sex differences exist in screening and treatment practices (Hyeouk et al., 2015). Network-based approaches, involving collaborations across multiple institutions, may help facilitate identifying more effective treatment strategies for women (Flynn et al., 2018).

SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER

Women with substance use disorder (SUD) face complex, multifactorial challenges across the life course. Although more men than women meet diagnostic criteria for SUDs (Fonseca et al., 2021; Koob and Moal, 2006)—a difference that has been shrinking for the last few decades (Fonseca et al., 2021; Keyes et al., 2008)—women progress from initial use to dependence at a faster rate and may exhibit more severe symptoms (Brady and Randall, 1999; Kosten et al., 1993).

The early stages of the United States opioid epidemic had a significant increase in nonmedical use of prescription opioids (Hirschtritt et al., 2018; Mazure and Fiellin, 2018). This trend was primarily driven by the treatment of chronic pain, which was more prevalent in women than men

(Racine et al., 2012; Templeton, 2020). Women were found to develop opioid use disorder (OUD) more rapidly than men (Hernandez-Avila et al., 2004; Mazure and Fiellin, 2018), often because clinicians were more likely to prescribe them to women (Mazure and Fiellin, 2018). Research indicates that it typically takes only 5 days to become physically dependent on opioids (Shah et al., 2017).

Biological Factors

Progress in understanding mechanisms linked to addiction-like behaviors have relied on rodents as experimental models. In general, female rodents, compared to male rodents, will self-administer substances of abuse and alcohol more rapidly, are more motivated to take cocaine (Cummings et al., 2011; Quigley et al., 2021a; Roberts et al., 1989), and show a higher drive to self-administer morphine and heroin (Cicero et al., 2003; Lynch and Carroll, 1999; Roth et al., 2002). They also consume more alcohol, relative to body weight, and engage in higher levels of cue-mediated alcohol-seeking behaviors (Cofresí et al., 2019; Crabbe et al., 2009). After periods of extended access to substances of abuse, female rats tend to exhibit greater symptoms of withdrawal, apart from alcohol and possibly opioids. In an animal model of relapse after forced abstinence, female rats compared to male rats exhibited greater cocaine-induced relapse (Lynch and Carroll, 2000), and greater drug- and cue-induced relapse (Cox et al., 2013).

Sex Chromosome Effects

Research in animal models has demonstrated the influence of sex chromosomes, independent of gonadal sex hormones, on addictive behavior. For example, preclinical studies using the FCG mouse model (see Chapter 2) show that after exposure to alcohol, XY mice developed a pattern of alcohol habit formation, and XX mice exhibited reward-seeking addictive behaviors regardless of gonadal phenotype (Barker et al., 2010). Additional research using this model also distinguished between sex chromosome and sex hormone effects on other aspects of alcohol addictive behaviors, including intake, preference, tendency for relapse, and habit formation. The results showed that the XX chromosome complement was associated with higher consumption initially and at relapse (Sneddon et al., 2022).

Studies analyzing cocaine addiction in the FCG animal model found both independent and interactive effects of sex chromosomes and sex gonadal hormones (Martini et al., 2020). Several addiction-associated genes are on the X chromosome—for example, genes encoding monoamine oxidase, an enzyme that regulates various neurotransmitters and implicated

in addiction mechanisms, and receptors for the neurotransmitters, GABA and glutamate (Krueger et al., 2023)—and leaky gene expression from the inactivated X chromosome in females could potentially explain sex differences in addictive behaviors (Krueger et al., 2023).

The Effects of Estrogens

Research has shown that estradiol, the most potent estrogen produced by the ovaries, modulates activity in the brain’s reward system in females and influences the acquisition, cravings, self-administration, and intake of substances. Female rats show enhanced motivation for cocaine at elevated estradiol levels, suggesting that estradiol facilitates their motivation for drug taking (Becker and Hu, 2008; Hu et al., 2003; Nicolas et al., 2019; Roberts et al., 1989). In gonad-intact female rodents, motivation is greatest during periods of the estrous cycle when estradiol is elevated (Becker and Hu, 2008; Becker and Koob, 2016; Roberts et al., 1989). Females in estrus exhibit greater drug-primed relapse for self-administering cocaine compared with those not in estrus and males, suggesting that estradiol enhances drug cravings that may contribute to the persistence of cocaine-seeking behaviors long into abstinence (Kippin et al., 2005). This notion is supported by studies showing that without estradiol replacement, adult females whose ovaries were removed have lower motivation for cocaine than those with estradiol (Becker and Hu, 2008; Hu et al., 2003; Nicolas et al., 2019). Sex differences in cocaine self-administration are evident, however, even in animals without gonadal hormones, with females without ovaries exhibiting greater intake than males (Hu et al., 2003). Exogenous estradiol is sufficient to enhance cocaine acquisition in females without ovaries (Hu and Becker, 2008; Hu et al., 2003; Lynch et al., 2001) but does not facilitate or enhance it in males (Jackson et al., 2005). Finally, sex differences in cocaine self-administration develop in animals that are not exposed to testosterone during the perinatal period and are exposed to ovarian hormones during puberty (Perry et al., 2013), indicating organizational influences of gonadal hormones on the brain that affect sex differences in this behavior.

Administered estradiol also facilitates the opioid acquisition in female rats without ovaries (Cicero et al., 2003; Lynch and Carroll, 1999) and enhances behavioral responses to and reinforcing effects of amphetamine (Robinson and Becker, 1986). During nicotine withdrawal, female rats with intact ovaries exhibit greater anxiety-like behaviors and stress responses compared with rats without ovaries (Torres and O’Dell, 2016). Intake of ethanol is higher during the stage of the estrous cycle in intact females when they are no longer receptive to the male (Forger and Morin, 1982; Roberts et al., 1998; Witt, 2007).

Other Biological Factors and Mechanisms

The transition from casual use of substances to developing a SUD in either sex is mediated by the brain’s reward system, with neurons responsive to the neurotransmitter dopamine activated in response to stimuli necessary for health and reproductive success, such as food consumption, sexual behavior and social interactions (Everitt et al., 1999; Robinson et al., 2015; Schultz, 1986; Wise and Rompre, 1989). Substances act on the reward pathway to induce dopamine neurotransmission either directly or indirectly, and repeated drug use causes physiological changes in the brain that include enhanced dopamine release (Engel and Jerlhag, 2014; Koob and Le Moal, 2008; Robinson and Becker, 1986). Repeated exposure to the acute rewarding effects of drugs can lead to escalated intake and compulsive drug-taking behaviors (Ahmed and Koob, 1998; Chartoff et al., 2009; Wise and Koob, 2014). Sex-related differences occur in neural responses to external stimuli and internal endocrine and physiological signals. Consequently, even when behaviors are the same in both sexes, sex related differences may be present in the neural circuitry activated and the brain’s response to a given situation (Farrell et al., 2013; Orsini et al., 2022; Quigley et al., 2021b).

The Maternal in Utero Environment

Exposure to addictive substances in utero predisposes offspring to developing SUD later in life. Research using animal models has demonstrated that maternal exposure to addictive substances, such as opioids or a high-sugar diet, increases the vulnerability of offspring to drug-seeking behaviors in adulthood (Abu and Roy, 2021; Gawliński et al., 2020). Human studies have shown that prenatal substance exposure plays a critical role in developing addictive behaviors as offspring get older. Alcohol exposure during pregnancy predicts drug dependence behaviors in adolescent and adult offspring after adjusting for certain confounding factors, including family history, prenatal smoking, current parental drinking habits, the environment, and other sociodemographic factors (Baer et al., 1998, 2003; Dodge et al., 2023). Similarly, prenatal cocaine exposure is associated with developing SUD in adolescent and adult offspring.

Although these studies either found no sex differences (Min et al., 2014) or involved small sample sizes that precluded sex-based analysis (Min et al., 2023), more recent studies have provided evidence of sex bias. In one study, prenatal substance use exposure was directly related to substance use progression in girls but not boys during adolescence (Marceau et al., 2021). In addition, findings from the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study have shown that certain measures of prenatal growth—considered a surrogate marker for exposures in utero—was associated with hospitalization for SUD in female adult offspring, suggesting that the fetal period may

be a critical developmental period during which women could develop sensitivities for SUD (Lahti et al., 2014). Overall, several lines of evidence support the maternal in utero environment as a major determinant in SUD susceptibility. However, as developing an addiction involves multiple factors, further research is needed to understand the sex-related vulnerability of women to SUD.

Specific Risk Factors in Women

Higher alcohol intake is associated with higher premenstrual or menstrual distress and negative affective states in women. This supports the hypothesis that women with PMS have higher levels of alcohol use or abuse (Evans and Levin, 2011; Kiesner, 2012; Mello et al., 1990; Svikis et al., 2006). Furthermore, women who have a history of, or are currently using cocaine, opioids, or alcohol have evidence of menstrual cycle disruptions (Emanuele et al., 2002; Mello et al., 1990, 1997; Schmittner et al., 2005). When the menstrual cycle is disrupted, it is more difficult to discern how, or if, ovarian hormones are influencing drug taking or motivation for it. In women aged 18–35, estradiol enhances the positive subjective effects of stimulant drugs, such as amphetamines, similar to findings from studies using animal models (Justice and de Wit, 1999).

Women often report using drugs initially to cope with negative affective states, such as depression (Kuntsche and Müller, 2011; Müller and Kuntsche, 2011), whereas men usually cite peer influence or sensation-seeking (Kuntsche and Müller, 2011). Other sex-related risk factors for substance use and SUD include IPV, which is more likely to affect women, and other social stressors such as death of child or loved one and divorce (NIDA, 2020). Mental health conditions are also more common among women who use substances of abuse. In particular, posttraumatic stress disorder has a strong relationship with developing a SUD, especially among young girls (NIDA, 2020).

Condition Presentation and Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria for SUD are the same for men and women, despite gender differences in how SUDs manifest. Some research has demonstrated that women entering SUD treatment programs present with a more severe clinical profile and an array of related social, medical, psychological, and multiple mental disorders (Mazure and Fiellin, 2018). Research has shown that depression, which is more prevalent in women, is associated with drug cravings and relapse (Curran et al., 2007; Zilberman et al., 2007), making it important to account for depressive symptoms when women present with concern about an SUD. Furthermore, although women may have used

substances for a shorter duration and in smaller amounts than men, the acceleration of SUD severity and deterioration in functionality occurs more rapidly (Fonseca et al., 2021; Mazure and Fiellin, 2018).

Treatment and Management

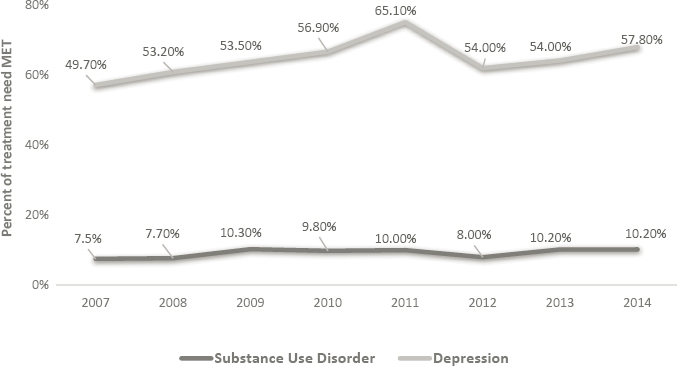

Despite women accounting for one-third of substance users, only one-fifth of the individuals receiving SUD treatment are women (UNODC, 2015). Women face greater barriers than men in accessing SUD treatment and harm reduction programs, such as syringe service programs, opioid overdose services, and drug testing. Based on National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data, less than 10 percent of women of reproductive age in need of SUD treatment were receiving it (Martin et al., 2020). Figure 6-2 shows that from 2007 to 2014, treatment receipt for SUD remained relatively stable, whereas it increased for depression. Systemic, structural, social, and cultural barriers that limit access to SUD treatment include stigma, punitive attitudes, discrimination, rigid admission requirements, and inflexible scheduling (see Chapter 7).

Disparities

The literature on differences in prevalence and mortality from overdose by race, ethnicity, and sexual identity is sparse (Schuler et al., 2020). A few studies have reviewed factors that may be associated with SUD for different

NOTE: SUD = substance use disorder.

SOURCE: Martin, 2020.

racial and ethnic groups. For example, studies have found that Latinas mainly from urban and metropolitan communities and born in the U.S. had greater odds of SUD, including OUD (Castañeda et al., 2019; Takada et al., 2024). A 2019 study based on data from the NSDUH found that Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander women had a higher prevalence of SUD, whereas Asian American women had higher rates of stimulant use compared to other racial and ethnic groups (Wang et al., 2023a). When comparing the relative risk of heavy episodic drinking and marijuana use, lesbian and bisexual women of color had an increased risk of use (Schuler et al., 2020).

Few studies have considered the role of both gender and race and ethnicity on treatment use (Pinedo et al., 2020). Studies have shown that Black and Hispanic women are less likely to receive treatment for SUD (Martin et al., 2020) and OUD (Iobst et al., 2024; Scheidell et al., 2024). Black, Latina, and other women of color from low-income communities wait longer before entering treatment and have a shorter length of stay in methadone treatment programs compared to men (Marsh et al., 2021).

Research Gaps

Differences in the biology of substance use are evident, influenced by factors such as ovarian hormones, drug type, dose, and exposure history (McHugh et al., 2018). It is also critical to understand how sex chromosome effects differentially influence addiction patterns in male and female individuals, which likely starts early in development via organizational effects on brain anatomy and function. Given the complexity of sex differences across bodily systems, multiple levels of analysis are needed. (McHugh et al., 2018).

Women develop drug dependence faster than men, but most research on risk factors and rates of progression from first use to SUD in women have been retrospective and not yielded a good understanding of the risk and protective factors in women and men. The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, will provide prospective data and analysis, and may begin to fill several of these research gaps (NIDA, 2023).

Despite no differences in how SUDs are diagnosed in men versus women, differences in gender and sex appear related to when they present for diagnosis (Mazure and Fiellin, 2018). Women tend to present symptoms of chronic pain and increased pain sensitivity and are thus more likely prescribed painkillers by physicians to alleviate symptoms (Mazure and Fiellin, 2018).

Diagnostic criteria recognize that SUD may manifest differently in women and men, but research is needed to determine if different diagnostic criteria are needed. Research assessing early interventions in women who

experience negative affective states, such as depression, or are exposed to adversities, such as ACEs, that may make them prone to drug use needs to be a priority. Considering the complexity of SUDs and the opioid epidemic, enhancing surveillance systems to encompass the intersectionality of factors such as gender, race, ethnicity, and geographic location will enhance screening and treatment approaches for diverse groups of women (Barbosa-Leiker et al., 2021).

HIV/AIDS

Chapter 3 noted that the rates of new HIV diagnoses and persons living with diagnosed HIV infection are much lower in women than men (CDC, 2023b). Although women represent a small proportion of new cases in the U.S. population living with HIV/AIDS, they have important and distinct characteristics of infection. To reduce the burden of HIV infection in both men and women, the White House Office of National AIDS Policy developed the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and implementation plan for Ending the HIV Epidemic in the United States (CDC, 2023a; HIV.gov, 2023). The stated goal is to reduce the number of new HIV infections and includes recommendations across four pillars of action: test everyone for HIV or DIAGNOSE infection, TREAT those who test positive with antiretrovirals and ensure viral suppression, PREVENT those who test negative from becoming infected by providing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medication and syringe services for those who inject drugs, and RESPOND by predicting new outbreaks (CDC, 2023a).

Biological Factors

Sex Chromosome Effects

Several important male versus female sex chromosome differences can influence various aspects of HIV infection. Differences in the sex complement can lead to variations in gene expression patterns, including those related to immune response and susceptibility to infections such as HIV (Moran et al., 2022; Scully, 2018). Furthermore, specific X chromosome genes encode proteins that play a crucial role in the innate immune response, including toll-like receptor-7 (TLR-7) and TLR-8, which are involved in detecting viral infections (Moran et al., 2022). As noted in Chapter 2, females undergo X chromosome inactivation to balance gene expression between the sexes. If the second X chromosome escapes inactivation, that leads to differences in gene dosage, which could contribute to variations in HIV susceptibility, immune response, and disease progression (Moran et al., 2022; Scully, 2018).

Epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, can regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Sex-specific epigenetic patterns may influence immune responses to HIV and contribute to differences in disease outcomes (Chlamydas et al., 2022). Understanding these sex chromosome differences and their interactions with hormonal and epigenetic factors is crucial for elucidating sex-specific disparities in HIV infection and developing tailored prevention and treatment strategies for both sexes.

The Effects of Estrogens

Female sex hormones have profound effects on multiple systems throughout the body and over the life-span. Female sex hormone fluctuations, such as during the menstrual cycle, in pregnancy, and from the use of contraceptives, influence the risk for HIV infection directly (Szotek et al., 2013) or indirectly through modulatory effects on the immune response (Swaims-Kohlmeier et al., 2021). During the menstrual cycle, there are changes in the vaginal tissue physiology and microbiome that can increase susceptibility to infection (Boily-Larouche et al., 2019). High levels of estrogens during the menstrual cycle may be protective and are associated with lower HIV acquisition (Asin et al., 2008; Moran et al., 2022; Wira et al., 2015). Progestin-only contraceptives, however, have been associated with an increased risk of acquiring HIV, although the precise mechanism is unknown (Moran et al., 2022; Ralph et al., 2015; Rodriguez-Garcia et al., 2021).

Pregnancy induces notable alterations in immune responsiveness (Akoto et al., 2021). The proinflammatory immune states observed during the first and third trimesters contrast with the anti-inflammatory state in the second trimester, and these changes could influence susceptibility to HIV infection (Rodriguez-Garcia et al., 2021). In addition, the molecular signals involved in mounting an immune response and the antimicrobial environment of the reproductive tract change significantly during pregnancy, which can also influence susceptibility to HIV infection. The cervical plug formed during pregnancy contains immune factors that exhibit potential anti-HIV activity (Mhlekude et al., 2021). Despite these insights, research has yet to definitively discern whether pregnancy heightens or decreases the risk of HIV infection and indicates an important research gap (Rodriguez-Garcia et al., 2021).

Sex hormone levels fall during menopause, affecting many immune biomarkers in the female reproductive tract. Research using models of cervical tissue has provided evidence of immune activation and increased HIV replication in menopausal tissue, indicating that menopausal women may have specific biological risks for acquiring HIV (Rodriguez-Garcia et al., 2021).

Specific Risk Factors in Women

Sexual behaviors and drug use are major risk factors associated with HIV infection among women. Eighty-four percent of new diagnoses among women are attributed to heterosexual contact and 16 percent to intravenous drug use (CDC, 2021b). A recent study of HIV risk behaviors in women found that 7 percent of cisgender women with HIV had had condomless sex in the past 12 months (CDC, 2022), which increases the risk of not only HIV but also other sexually transmitted infections, such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis (NASEM, 2021). It is now well understood that sexually transmitted infections can increase susceptibility to HIV infection and render persons with HIV more infectious (NASEM, 2021).

Intravenous and other drug use has been increasing in the United States, leading to new HIV infections among persons who use drugs (Springer et al., 2020a, 2020b); sharing and reusing needles, syringes, or other injection equipment can increase the risk of getting or transmitting HIV. One study reported that women who share needles had a significantly higher likelihood of contracting HIV compared to men, with the authors attributing that to multiple and overlapping sexual and drug use partners (Riehman et al., 2004; Valente et al., 2001). Substance use can also affect judgment and lead to sexual behaviors that increase the risk of HIV, such as unprotected sex or sex with multiple partners (Riehman et al., 2004; Valente et al., 2001).

Condition Presentation and Diagnosis

In the early stage of infection, women have higher CD4+ T cell counts and lower HIV plasma RNA loads, but both men and women progress to AIDS at similar rates. Women, however, have been seen to progress to AIDS at higher rates compared to men of equivalent HIV RNA load. This has implications for screening, testing, and treatment (Farzadegan et al., 1998; Moran et al., 2022; Ziegler and Altfeld, 2016).

Early in the AIDS epidemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) set the case definition of AIDS based primarily on conditions seen in gay men and without fully capturing the experience of women (McGovern, 1994; OTA, 1992). Gynecological conditions, such as cervical dysplasia, pelvic inflammatory disease, and recurrent yeast infections, more common in HIV-infected women were not included. After significant protests by women and others, CDC changed its definition of AIDS; candidiasis and invasive cervical cancer are now among the listed conditions affecting women (CDC, 2021a).

Treatment and Management

PrEP and Treatment

PrEP is the standard approach to HIV prevention for people who are at risk. The regimen consists of three FDA-approved medications that prevent infection by almost 99 percent: two daily oral formulations and one injectable medication administered every 8 weeks. USPSTF released new guidance in August 2023 (Liu et al., 2023; USPSTF et al., 2023) with an “A” recommendation, indicating high certainty of substantial benefit from these medications to prevent HIV. Although the national goal is to increase the estimated people with PrEP indications actually being prescribed PrEP to at least 50 percent by 2025 and remain at 50 percent by 2030, only 10 percent of women who could benefit from PrEP were prescribed it in 2019, indicating major barriers to access for women (CDC, 2021d).

Another goal is to provide life-saving combination antiretroviral therapy3 (ART) to all persons within 7 days of a positive HIV test (Gandhi et al., 2023) and to achieve 100 percent viral suppression. Staying in HIV care is important to achieving and maintaining viral suppression and is improving health and morbidity for the individual and reducing transmission to uninfected individuals (Eisinger et al., 2019). In 2020, 23 percent of cisgender women with HIV reported missing at least one medical appointment in the past 12 months (CDC, 2023c), and approximately 63 percent of them with HIV reported taking all of their doses of ART over the last 30 days (CDC, 2023c). In 2019, only 64 percent of women with diagnosed HIV in 44 states and the District of Columbia were virally suppressed (CDC, 2021d).

Having access to needed ancillary services could reduce barriers to achieving and maintaining viral suppression; the top three services cisgender women with HIV reported needing but not receiving in the past 12 months in 2020 were dental care, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, and shelter and housing services (CDC, 2023c). Six percent of cisgender women with HIV reported homelessness in the past 12 months, and 21 percent reported symptoms of depression or anxiety (CDC, 2023c), both of which research has shown to affect the ability to access health care, HIV care, and ART and maintain viral suppression.

___________________

3 ART is a regimen for treating HIV-positive individuals that reduces the levels of HIV in the body. PrEP is meant to prevent infection and taken before a person thinks they might be exposed.

With appropriate ART, women with HIV can live longer. In fact, life expectancy for people with HIV is approaching that of the general population. Some individuals living with HIV experience multiple comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, renal disease, neurocognitive disease, and cancer. In one study, women with HIV had significantly more ageing-related comorbidities than men with HIV. Women had higher prevalence of diabetes, bone disease, and lung disease than men (Collins et al., 2023). Multiple chronic conditions pose challenges for women, health care providers, and health care systems involved in managing them. These challenges are discussed further in Chapter 8.

Disparities

Disparities in HIV prevention and care for women persist, particularly among sexually, racially, and ethnically minoritized populations. Although these populations are well studied and progress has been made along the HIV care continuum, further work is needed to understand their needs for prevention and treatment, as the majority of research has focused on mother-to-child transmission (Nwangwu-Ike et al., 2023).

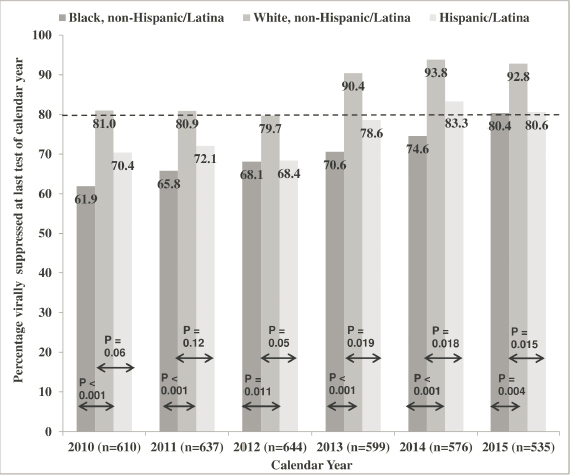

Racial and ethnic differences in HIV incidence in women are well known and captured by national surveillance data (see Chapter 4) (CDC, 2023b). Given that the prevalence and incidence is greatest among Black women, followed by multiracial, and Hispanic/Latina women, this disparity clearly needs to be addressed. One study following a prospective cohort of women from the HIV Outpatient Study (Buchacz et al., 2020) found that the odds of using and adhering to ART was lower among Black women compared to Hispanic/Latina and White women (Geter et al., 2019). Furthermore, the rate of achieving viral load suppression was lower among Black and Hispanic/Latina women (see Figure 6-3).

Qualitative studies have described barriers to care encountered by Black and Hispanic/Latina women living with HIV. Among Hispanic/Latina women, a systematic review cited emergent barriers to seeking HIV services that included lack of social support, insurance coverage, out-of-pocket fees, mental health outcomes, HIV-related stigma, and unique barriers such as language; fear of legal consequences, including deportation; and limited access to documentation (Geter Fugerson et al., 2019). Key features of quality of care for Black and Hispanic/Latina women included care that is integrated and coordinated with other support services, compassionate and nonjudgmental care, and shared decision making (Rice et al., 2020). Thus, HIV health care services require tailoring for these populations.

SOURCE: Geter et al., 2018.

Research Gaps

Significant research gaps exist regarding the safety and efficacy in women of the medications used to prevent and treat HIV, in part because women have been and continue to be underrepresented in research studies of PrEP and ART. A 2016 systematic literature review reported that women represent a median of 19.2, 38.1, and 11.1 percent of participants in ART and PrEP, prophylactic vaccine, and HIV cure strategies studies, respectively (Curno et al., 2016). One reason for this low participation is that most PrEP studies focus on enrolling solely men because they represent 80 percent of people living with HIV (CDC, 2021c). Other reasons include greater stigma affecting women with HIV compared to men (Karim et al., 2022) and the lack of women-specific recruitment strategies to educate and enroll women.

Without adequate representation of women in clinical trials of PrEP and ART, significant gaps remain in understanding gender differences in the virological, immunological, and clinical presentation of HIV. Specifically, studies that consider women-specific biological factors and their potential influence on PrEP are needed. Such studies would seek to better understand the role of sex hormones, genital inflammation, genital microbiome, sexually transmitted infection, and sex differences in immune responses

and mechanisms and how they may influence the safety and effectiveness of PrEP and ART (Karim et al., 2022). Clinical studies are also needed to better understand sex-related issues and PrEP, including for transgender women, and women who use drugs during the reproductive period along with hormonal contraception, during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and during menopause (Karim et al., 2022).

Research on improving HIV prevention and treatment for women is lacking, including research focusing on patient preferences regarding oral versus injectable ART or PrEP. Such studies would inform clinicians’ understanding of patient preferences about the settings in which to start ART and how to link and differentiate care by gender, comorbidity, and setting. Randomized prospective trials and studies powered to detect sex differences in access to treatment and prevention are also lacking.

Trials on HIV prevention and treatment that have an insufficient number of women do not have the power to differentiate medication effects by sex, which leave gaps in clinician knowledge around safety and efficacy (Gandhi et al., 2023). Without rigorous published studies that prospectively evaluate the effect of sex differences on preventing and treating HIV, recommendations specific to the needs of women will remain limited.

MIGRAINES/HEADACHES

Migraine disproportionately affects women in the years when they are most productive and active. Studies have shown that it is a complex, multifactorial disease with genetic factors increasing susceptibility and non-genetic factors regulating clinical presentation (Ferrari et al., 2015). The higher prevalence of migraine in women involves many factors, discussed next.

Biological Factors

During a migraine attack, multiple parts of the central and peripheral nervous systems are activated simultaneously (Charles, 2018). Migraine has several key mechanistic features. One mechanism involves central nervous system (CNS) processing of sensory input from the trigeminocervical complex (Bartsch and Goadsby, 2003) that activates the brain’s pain-processing center and the release of neuropeptides (Charles, 2018; Goadsby and Holland, 2019). The developmental differences in male and female pain-sensing systems and the effect of circulating hormones are the main physiological factors driving the higher prevalence of migraine among women (Pavlovic et al., 2017).

Cortical spreading depression—a slowly propagating wave of altered brain activity that involves changes in neuronal, glial, and vascular function (Charles and Baca, 2013)—is another important mechanism. Animal studies have shown a lower threshold to initiate cortical spreading depression in

female compared to male mice, regardless of the phase of estrous cycle (Brennan et al., 2007). Functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have found structural changes in the specific brain regions involved in pain processing in women and men with migraine compared to healthy women and men (Maleki et al., 2012). Another study found reduced functional connectivity in sensorimotor networks and one of these same brain regions in women during migraine attack (Araújo et al., 2023).

Genetic factors may contribute to the threshold for triggering migraine in women compared to men. Population-based studies identified 38 genomic loci (Gormley et al., 2016) and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified 13 genes (Ferrari et al., 2015) as disease-associated gene variants. However, researchers have not found associations of these genetic variants with sex differences that explain the high prevalence of migraine in women, suggesting that other factors, perhaps hormonal differences, play significant roles in the clinical presentation.

Sex Chromosome Effects

Limited results address sex chromosome effects on the pathobiology of migraine. However, genetic studies have revealed several migraine susceptibility loci on the X chromosome, indicating possible roles of its genes. One study identified such a locus on Xq12, which includes the HEPH gene that encodes an enzyme involved in iron homeostasis, and others have implicated Xp22, Xq27, and Xp28 (Maher et al., 2012a; Maher et al., 2012b; Wieser et al., 2010). A case-control study has shown a link with the X chromosome gene SYN1, which encodes synapsin, a protein involved in neurotransmitter release at neuronal synapses (Quintas et al., 2020).

The Effects of Estrogens

Research has shown that female hormonal changes during puberty, pregnancy, and perimenopause can trigger migraine episodes, suggesting that ovarian hormones, notably estrogens, play an important role (Pavlovic et al., 2017). The “estrogen withdrawal effect” is the most commonly accepted theory for menstrual migraine, and women with histories of migraine exhibit faster declines in estradiol levels during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (Pavlovic et al., 2017). Reductions in circulating estrogens before and during menstruation are associated with migraine episodes, suggesting that estrogens somehow hinder the abnormal neural activity associated with migraine (MacGregor and Hackshaw, 2004; Somerville, 1972).

Estrogens exert multiple effects on neural pathways involved in migraine, including the trigeminovascular pathway and central pain

pathways that traverse the central and peripheral nervous systems. These pathways contain neuronal populations that express ERs (Pavlovic et al., 2017). Animal studies have also identified ERs in trigeminal ganglion neurons (Bereiter et al., 2005; Puri et al., 2006). Estrogens have been reported to affect the excitability of second-order trigeminal sensory neurons involved in craniofacial pain syndromes, which was proposed as a mechanism shared in migraine (Cairns, 2007). In addition, estrogens, as well as progesterone, regulate serotonergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter systems, which are also involved in migraine pathophysiology (Vetvik and MacGregor, 2021).

Research has provided more detailed mechanistic insight into how estrogens are involved in migraine. It is thought to regulate migraine episodes by increasing expression of the oxytocin receptor and levels of the analgesic hormone oxytocin (Amico et al., 1981; Miller et al., 1989; Murata et al., 2014), which has also been implicated in preventing migraine attacks (Krause et al., 2021; Phillips et al., 2006; Tzabazis et al., 2017). Patterns of fluctuating plasma levels of oxytocin and estrogens are similar during the menstrual cycle (Engel et al., 2019), suggesting that reductions in oxytocin may also trigger migraine (Krause et al., 2021). In addition, evidence shows that estrogens modulate levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) (Cetinkaya et al., 2020; Labastida-Ramírez et al., 2019), a known contributor to migraine through its effects on vasodilation and neurogenic inflammation (Karsan and Goadsby, 2015). Research has shown that CGRP release is lower when levels of estrogen are high (Pavlovic et al., 2017), suggesting that estrogen withdrawals during certain phases of the menstrual cycle may increase CGRP and the likelihood of triggering an attack. Estrogens also regulate other analgesic neuropeptides and hormones, such as vasopressin (Lagunas et al., 2019), prolactin (Avona et al., 2021; Franchimont et al., 1976), and orexin (Porkka-Heiskanen et al., 2004), indicating that estrogens may mediate its effects on migraine through multiple mechanisms.

Specific Risk Factors in Women

Reproductive Milestones

The prevalence of migraine changes throughout a woman’s life (Pavlović, 2021). Migraine first appears during puberty, occurs around the time of menstruation, fluctuates through pregnancy, worsens during the perimenopausal stage, and usually improves after menopause (Burch, 2020; Pavlović, 2021). The high prevalence of migraine and severe disability rate that accompanies it during the productive ages can reduce productivity at work and impair family and social functioning (Buse et al., 2019).

Migraine and Oral Contraceptive Use

The risk of stroke is twofold higher in women experiencing migraine with aura as compared to women without migraine and sixfold higher in women using estrogen-containing contraceptives (Lee et al., 2023a). CDC’s U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria of Contraceptive Use states that estrogen-containing contraceptives have an unacceptable health risk for women who experience migraine with aura, but the benefits for women who have migraine without aura outweigh the risks (CDC, 2016). At one time, research tied estrogen-containing contraceptives to a high risk of stroke (Calhoun, 2017), but today’s contraceptives contain much lower levels of estrogens, which appears to eliminate that excess risk. They can help control menstrual-related migraine and painful menstruation by stabilizing levels of estrogen (Nappi et al., 2022).

Gender Roles and Mental Health Factors

The 2010 ACEs study reported a higher prevalence of frequent headaches in individuals with ACEs (Anda et al., 2010). In the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study, a history of emotional abuse was more common in women who experience migraine even after adjusting for depression and other sociodemographic factors (Tietjen et al., 2015), and data from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health showed that migraine was more prevalent in both women and men who experienced violence or sexual or physical abuse as a child (Brennenstuhl and Fuller-Thomson, 2015). Several studies have found that migraine is more prevalent in women who have experienced IPV compared to those who have not (Coker et al., 2000; Cripe et al., 2011; Gelaye et al., 2016; Vives-Cases et al., 2011), although more research is needed.

Despite some studies on the effects of IPV on a woman’s physical and mental health, not enough studies explore its relation to migraine. The known effects of maltreatment on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and stress-mediating homeostatic systems is the presumed mechanism linking childhood maltreatment and migraine (Tietjen et al., 2016).

Condition Presentation and Diagnosis

The International Classification of Headache Disorder third edition (ICHD-3) is the latest system for classifying headache disorders (IHS, 2018; Levin, 2022). The diagnostic criteria in ICHD-3 has been internationally accepted and used in headache-related studies. Migraine is a primary headache disorder with two major types, with and without aura. Migraine without aura for adults is defined as a minimum of 4 hours of headache

with specific symptoms, including nausea and an abnormal sensitivity to light and sound. Migraine with aura is identified with transient neurological symptoms accompanied by or preceding the headache.

Between 18 and 60 percent of women who experience migraine report that they occur most often during menstruation (Vetvik and MacGregor, 2021). Menstrual migraine is included in the appendix of ICHD-3, but the diagnostic criteria still require validation (Cupini et al., 2021). Based on those criteria, menstrual migraine occurs in two forms: pure and menstrual-related (Ceriani and Silberstein, 2023). Women with pure menstrual migraine report having an attack between 2 days before and 3 days after the start of menstruation and none at other times. Women who experience menstrual related migraine report attacks related to their menstruation and also at other times. Menstrual migraine lasts longer, causes more disability, and does not respond as well to acute treatment (Granella et al., 2004; Pinkerman and Holroyd, 2010).

Treatment and Management

“Throughout my life, I have been on and off treatments. Some have been helpful. Some have not. There have been significant side effects with a lot of the treatments and I faced a lot of challenges during graduate school, my working life, particularly during my pregnancies and while breastfeeding my children to find therapies that were safe and hopefully allow[ed] me to function . . . a lot of women delay pregnancy, go without treatments during certain times of life and that can negatively affect our lives and the lives of those around them. I have missed out on moments or times with family and friends.”

—Presenter at Committee Open Session

Acute Migraine Treatment

Migraine causes more than 1.2 million visits to U.S. emergency departments annually and is the third leading cause of emergency department visits in reproductive-aged women (Burch et al., 2018; Minen et al., 2018). Several families of drug—triptans, such as sumatriptan (Imitrex®), and ditans such as Lasmiditan (Reyvow®) are FDA approved as acute treatments (Yang et al., 2021). In March 2023, FDA approved zavegepant (Zavzpret®), a nasal spray that blocks CGRP activity and can bring relief within 30 minutes, to treat acute migraine with or without aura (Dhillon, 2023).

Guidelines based on high-quality, evidence-based approaches are not available for emergency room acute treatment (Robblee and Grimsrud, 2020). In addition, lack of referral or follow-up plan with a neurologist or headache specialist causes high readmission rates to emergency departments (Giamberardino et al., 2020), with one study finding that more than

a quarter of initial visitors for migraine return within 6 months (Minen et al., 2018). More studies are needed on acute care in emergency rooms to develop nationally accepted treatment protocols.

Management has changed with the approval of CGRP-blocking drugs as preventive agents. These new agents include rimegepant (Nurtec®), ubrogepant (Ubrelvy®) and atogepant (Qulipta®). In addition, monoclonal antibody therapies that block CGRP have recently been developed and hold much promise for preventing migraine: three FDA-approved, self-injectable drugs—galcanezumab (Emgality®), erenumab (Aimovig®) and fremanezumab (Ajovy®)—and andeptinezumab-jjmr (Vyepti®), which is an intravenous infusion every 3 months (Pope, 2023).

Migraine Diagnosis and Treatment During Pregnancy

Even though acute headache during pregnancy should always raise a concern about secondary headache disorders, migraine is the most common cause of these headaches (Burch, 2019). Although migraine is primarily a headache disorder, it increases the risk of preeclampsia, cerebral blot clots, and pregnancy-associated stroke compared to women without a history of migraine (Greige et al., 2023).

Up to 10 percent of pregnant women can start to experience migraine without aura, while the onset of migraine with aura has been reported up to 14 percent (Negro et al., 2017), and approximately 60–80 percent report that their migraine symptoms improve during pregnancy (Allais et al., 2019). Based on the data from American Registry for Migraine Research, 20 percent of women who experience migraine avoid pregnancy for fear of their migraines worsening, of having a difficult pregnancy with migraine disability, and the potential adverse effect of their migraine treatment on the fetus (Ishii et al., 2020).

The recommended first-line treatment for migraine during pregnancy is nonpharmacological therapies, including lifestyle changes, cognitive behavioral therapy, and biofeedback (Verhaak et al., 2023). However, accessing these therapies is not easy for pregnant women. Therefore, pharmacological therapies should be considered for those who either do not have access to nonpharmacologic treatments or did not benefit from them. One study supports that triptans are safe to take during pregnancy; however, a control group was not included for comparison (Ephross and Sinclair, 2014).

Based on the 2022 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists updated guideline, little high-quality data exist on treating migraine during pregnancy, leaving treatment decisions up to the patient and clinician (ACOG, 2022). Lack of data leads clinicians to hesitate when starting treatment for chronic migraine in pregnant patients. On a recent survey with women’s health care providers in Connecticut, 60 percent reported

they did not feel comfortable starting new preventive treatments during pregnancy, and 40 percent reported referring such patients to headache specialists or neurologists rather than starting treatment (Verhaak et al., 2023).

Disparities

Disparities among racial and ethnic groups exist regarding the severity of headaches. African American individuals reported more frequent and intense headaches and were more likely to discontinue treatment for migraine in specialty clinic settings than White individuals (Kiarashi et al., 2021). American Indian and Alaska Native individuals had the highest prevalence of migraine among all U.S. racial and ethnic groups, with the lowest rate among Asian Americans (Burch et al., 2018). A 2021 literature review found that only 46 percent of Black individuals received care for their migraines compared to 72 percent of White individuals and that only 14 percent of Black patients received a prescription for migraine medication compared to 37 percent of White patients (Kiarashi et al., 2021). The same survey found that Hispanic and Latina/Latino individuals were 50 percent less likely to receive a migraine diagnosis and were less likely to receive a prescription for migraine prevention medication than White individuals.

Transgender and gender-diverse individuals are affected significantly by migraine. Some evidence has suggested that transgender women who have received gender-affirming hormone therapy may have a higher risk of migraine resulting from the effect of estrogens on the nervous system/brain (Ahmad and Rosendale, 2022). A study based on National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 2013 to 2018 found that bisexual women had 33 percent greater odds of headache/migraine than did lesbian women. The same study found the risk of migraine was 25 percent higher in sexual minority women compared to heterosexual women (Heslin, 2020).

Research Gaps

Research has long established that more women than men experience migraine, but the pathophysiological mechanisms and genetic influences underlying sex differences in the presentation and frequency of occurrence throughout the life-span are not well understood. This is in part the result of most preclinical research using animal models that only focus on males (Eisenstein, 2020). One of the very common and debilitating forms for women, menstrual migraine, has only been included in the appendix of ICHD-3 and is still waiting to be validated as a diagnosis. The lack of diagnostic certainty leads to exclusion from treatment trials; there are no specific treatment options available.

Based on the data, 60–80 percent of women with migraine report improvement during pregnancy, but no literature addresses why the 20–40 percent do not. Evidence on the treatment options regarding benefits or risks during pregnancy, breastfeeding, or postpartum is insufficient. Specific data are also lacking on dosing or the effect of comorbidities for medications during pregnancy. New studies are also needed to clarify the specific formulations of combined hormonal contraceptives and the risk of stroke associated with them in different subtypes of migraine. Overall, more data are needed to develop treatment guidelines for pregnancy.

Despite evidence supporting an association between migraine and trauma (e.g., ACEs, interpersonal violence), more research is needed to explore how social factors influence susceptibility to migraine. No data exist on the effect of infertility treatment or gender-affirming hormone therapy on migraine and risk of stroke in patients with history of migraine. The effect of migraine on sexual and gender minority groups is challenging to study, and studies have conflated sex and gender when collecting this information. Nationally accepted treatment approaches in emergency room for acute migraine care are needed, as are strategies to reduce the need for emergency care.

CARDIOMETABOLIC CONDITIONS

“There has to be more attention paid to awareness [of CVD symptoms in women] . . . in the medical community and hospital emergency rooms . . . women talk so often of just being dismissed or diagnosed with GERD [gastroesophageal reflux disease] . . . and not taken seriously that they may be having a heart attack.”

—Presenter at Committee Open Session

Cardiometabolic conditions cause significant morbidity and mortality in women. These conditions often occur together, and causes are multifactorial, in which their development can be explained by various factors. This section focuses on two chronic cardiometabolic conditions with high morbidity and mortality in women—CVD and stroke—and highlight sex and gender differences in known risk factors for both. Other cardiometabolic conditions, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, and Type 2 diabetes, are also discussed as risk factors.

Biological Factors

A discussion of cardiometabolic conditions encompasses multiple major clinical heart and circulatory conditions—including stroke, brain health, complications of pregnancy, kidney disease, congenital heart disease,

rhythm disorders, sudden cardiac arrest, subclinical atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, valvular disease, venous thromboembolism, and peripheral artery disease—the associated risk factors, including diabetes and obesity; and outcomes, including quality of care, procedures, and economic costs. Although many cardiometabolic conditions have overlapping biological mechanisms, some mechanisms are specific to a pathology. To summarize potential key factors that regulate the etiology of cardiometabolic conditions in women, this section highlights findings for the consensus on the more general role of key biological factors that affect women.

Sex Chromosome Effects

The contribution of the X chromosome to developing cardiometabolic conditions is not fully understood, largely because the majority of GWAS studies do not include sex chromosomes (Regitz-Zagrosek and Kararigas, 2017). However, studies in the FCG model have identified specific differences related to metabolism, with the XX, compared to the XY chromosome complement promoting fat accumulation related to increased food intake during the inactive phase of the diurnal cycle and metabolic inflexibility to switch between carbohydrate and fat fuels for energy metabolism (Chen et al., 2012, 2015; Link et al., 2020).