Cannabis Policy Impacts Public Health and Health Equity (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

Cannabis1—federally known as “marijuana”—is currently a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA, PL-91-513)—meaning it has high abuse potential and no federally accepted medical use. This categorization has long been controversial because of the drug’s perceived social and medical benefits, as well as the racism and classism common in the broader conversations about drug policy in the United States (Montgomery and Allen, 2023). Now, as a result of sweeping policy changes at the state level and the removal of hemp from the CSA, extensive markets for cannabis products can be found throughout the country, even in states that have not chosen to legalize cannabis (Chapekis and Shah, 2024; Elbein, 2024). The limited federal involvement in state-specific cannabis legalization has allowed the establishment of commercial markets for cannabis that neglect consideration of public health (Jernigan et al., 2021).

Although some states decriminalized cannabis in the 1970s and 1980s, the drug was first legalized by a state in 1996, with California Proposition 215 (MacCoun and Reuter, 2001). California Proposition 215 legalized cannabis for medical use only, but it ushered in a wave of new state medical cannabis programs over the next two decades, which evolved in 2012 to the first successful passage of legal cannabis possession for anyone over

___________________

1 “Cannabis” is a broad term that can be used to describe products (e.g., cannabinoids, marijuana, hemp) derived from the Cannabis sativa plant. These products exist in various forms and are used for various purposes (e.g., medical, industrial, social). The all-encompassing word “cannabis” has been adopted as the standard terminology within scientific and scholarly communities. The committee uses the term “cannabis” rather than “marijuana” throughout this report.

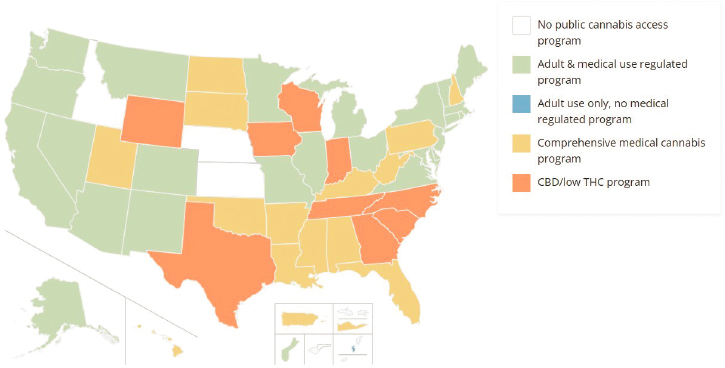

21 in Colorado and Washington state, and the establishment of a regulatory structure for retail sales. As of April 24, 2023, 38 states, three territories, and the District of Columbia allowed the medical use of cannabis products (Figure 1-1). As of November 8, 2023, 24 states had passed legislation legalizing cannabis sales and use by adults over 21 years of age.2 Approved measures in 9 additional states allow the sale of products with low delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) high cannabidiol (CBD) products in limited medical situations (NCSL, 2024a, 2024b). Although not all states have voted to legalize cannabis, cannabis is sold throughout the United States and online, mainly as a result of the definition of “hemp” in the 2018 Agriculture Improvement Act (PL-115-334).

Cannabis policy changes have been influenced by political campaigns that are often financed by wealthy donors (Gunther, 2024; NFIA, 2017). Initially, state medical programs were implemented out of compassion for patients seriously ill with AIDS or cancer for whom cannabis was thought to ease suffering (Goldberg, 1996). This process was furthered by proponents who exaggerated the medical or therapeutic benefits of cannabis and minimized its harms (Jernigan et al., 2021). Greater social acceptance of cannabis use and growing skepticism about the effort and expense involved in enforcing cannabis penalties also contributed (Felson et al., 2019). National survey data suggest a near-total reversal of public

NOTE: CBD = cannabidiol; THC = delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. The map does not include state policies instituted in response to the 2018 Agriculture Improvement Act (PL-115-334).

SOURCE: National Conference of State Legislatures, 2024.

___________________

2 Some state medical cannabis laws allow use among those under 21 years of age.

opinion on cannabis legalization over the last 50 years, with the proportion of survey respondents who support legalization increasing from 12 percent in 1969 to 70 percent in 2023 (Saad, 2023). Ballot initiatives in Colorado and Washington were supported by a broad swath of policy perspectives, including those of civil liberties organizations and drug policy reform groups (Martin, 2012).

More recently, cannabis policy reforms have been associated with strategies designed to adjust for the large racial inequalities in arrests for violations of cannabis prohibition. Although national arrest statistics have gaps in race and ethnicity data, it appears that White people are less likely to be arrested for cannabis use than are members of communities of color (Bunting et al., 2013; Resing, 2019). Cannabis policy reforms are supported by 85 percent of Black people (Edwards, 2022), as well as civil rights groups such as the National Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP, 2019), which have supported cannabis decriminalization and regulation of adult cannabis use.

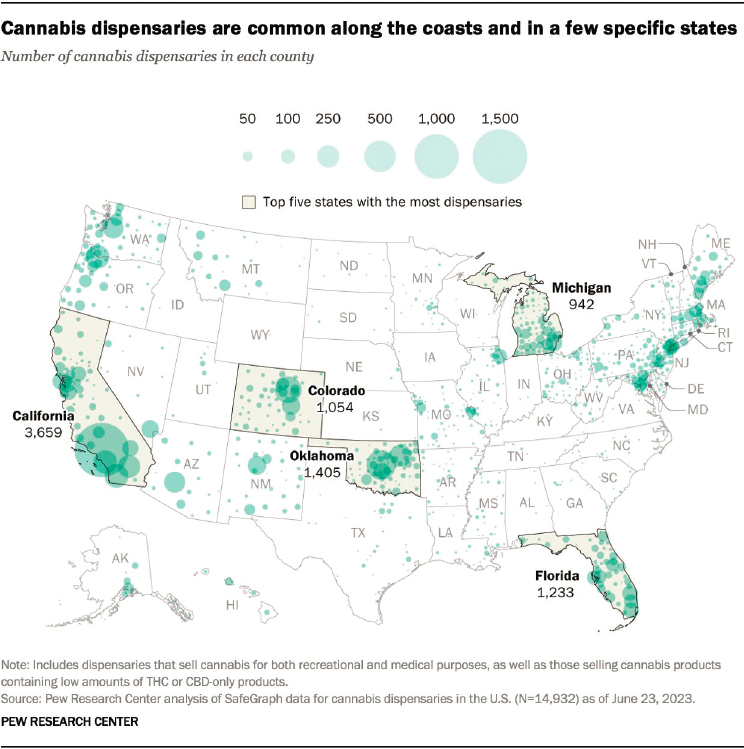

Legalization has led to the widespread availability of cannabis. At least 79 percent of Americans now live in a county with a medical or adult-use cannabis retail outlet; this figure is an underestimate because of the availability of hemp products (Chapekis and Shah, 2024) (Figure 1-2). In many states, cannabis retailers are more concentrated in neighborhoods characterized by historical disadvantage (Amiri et al., 2019; Matthay et al., 2022; Shi et al., 2016). Retail access to cannabis is associated with calls to poison control, cannabis use in pregnancy, cannabis use–related hospitalizations during pregnancy, and increased cannabis use by adults (Cantor et al., 2024). Many people now worry that changes in cannabis policy, which in part have been touted as improving social justice, may be contributing to health inequities (Cantor et al., 2024).

CANNABIS USE AND HEALTH

People use cannabis for many reasons, both recreational and medicinal. Its intoxicating effects can be relaxing, invoke euphoria, and improve sociability and sensory perception. However, it is common for cannabis to impair short-term memory, worsen anxiety, and impair perception and motor skills (Agrawal et al., 2014). Acute outcomes, such as poisoning due to accidental overconsumption or cannabinoid hyperemesis,3 are also associated with cannabis use. Harms from cannabis use may come from the impacts of the drug itself or other constituents. For example, cannabis is often consumed

___________________

3 “Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome” is a condition where a patient experiences cyclical nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain after using cannabis, and it can cause intense pain (Chu and Cascella, 2023).

NOTES: SafeGraph curates information about millions of places of interest around the globe (https://www.safegraph.com [accessed March 24, 2024]). The Pew analysis includes those retail outlets that sell cannabis (including low-THC cannabis products) for medical or adult use but does not include outlets selling cannabis products marketed as “hemp” or “derived from hemp.” CBD = cannabidiol; THC = delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol.

SOURCE: Chapekis and Shah, 2024. Most Americans now live in a legal marijuana state–and most have at least one dispensary in their county. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/02/29/most-americans-now-live-in-a-legal-marijuana-state-and-most-have-at-least-one-dispensary-in-their-county, from SafeGraph (accessed April 1, 2024).

by smoking, and cannabis smoke has a strikingly similar profile to tobacco smoke in terms of its physical and chemical properties (Graves et al., 2020). Much as with tobacco, there are growing public health concerns about

exposure to secondhand cannabis smoke. Toxicological studies have shown that even brief exposure to secondhand cannabis smoke may impact blood vessel linings (Wang et al., 2016). One study in New York City found biomarkers of cannabis exposure in 20 percent of children enrolled in the study (Sangmo et al., 2021).

A prior report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017) comprehensively reviews the literature on the health impacts of cannabis use. It categorizes the evidence reviewed into one of five categories: conclusive, substantial, moderate, limited, and no or insufficient. The report offers more than 100 conclusions on both the harms and the therapeutic effects of cannabis consumption (NASEM, 2017).

The 2017 report cites evidence of therapeutic benefit for a handful of conditions, despite many more purported medical benefits. There was conclusive evidence of therapeutic benefit for the use of oral THC-like cannabinoids (such as nabilone and dronabinol) in treating chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Substantial evidence supported the use of cannabis for managing chronic pain in adults and the effectiveness of oral cannabinoids (nabiximols and nabilone) in improving patient-reported spasticity symptoms in multiple sclerosis (NASEM, 2017).

NASEM (2017) also cites evidence for many harms associated with cannabis use. Substantial evidence linked cannabis use with an increased risk of motor vehicle collisions and the development of schizophrenia or psychosis, with the highest risk seen among frequent users. Furthermore, substantial evidence linked long-term cannabis smoking with respiratory issues, including increased chronic bronchitis, as well as lower birthweight in offspring exposed prenatally (NASEM, 2017). Evidence for many more potential harms was classified as moderate or limited (Annex Table 1-1). The 2017 report also notes many data gaps, although given that the literature searches for that study were completed in June 2016, some of those data gaps may now have been filled.

CHANGES IN CANNABIS PRODUCTS AND USE

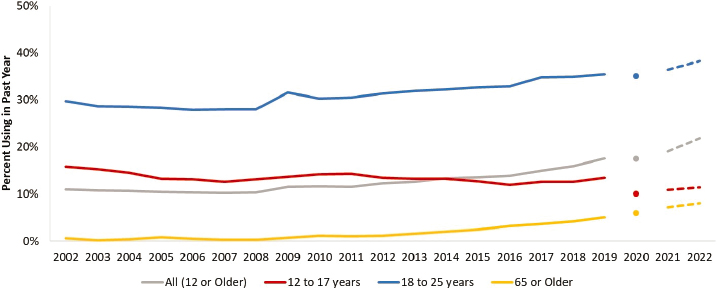

At the same time that cannabis legalization has been occurring within the states, patterns of cannabis use have changed and new cannabis products have emerged, generating public health concerns. New cannabis products include those with high concentrations of delta-9-THC and those with cannabinoids that are less well studied (Box 1-1). According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), in 2002, 11 percent of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population aged 12 years or older reported past-year cannabis use. In 2019, that figure had risen to over 17 percent. The NSDUH began using new methods in 2020 and again in 2021, making comparisons with prior years difficult, but an

BOX 1-1

Cannabis and Cannabinoids: A Primer

The cannabis plant contains more than 100 “phytocannabinoids,” compounds that are unique to the cannabis plant, and hundreds of compounds not unique to the plant, such as terpenes and flavonoids (Hanus et al., 2016). Although sometimes referred to as “hemp” or “marijuana,” all cannabis plants fall within the same genus: Cannabis (McPartland, 2018). U.S. law distinguishes hemp and marijuana based on the concentration of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in industrial hemp, defined in the United States as having ≤0.3% delta-9-THC on a dry-weight basis (2018 Agriculture Improvement Act [PL-115-334]).

Delta-9-THC: Delta-9-THC is the most well-studied cannabinoid. Its therapeutic effects include the ability to reduce nausea, increase appetite, and decrease chronic pain. “Dronabinol,” a synthetic version of delta-9-THC, and “nabilone,” a THC-like drug, are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy, and dronabinol is approved for treating anorexia in AIDS patients. However, delta-9-THC can induce intoxication, affect cognition, impair motor function, and lead to physiological dependence after chronic exposure. The biological effects of delta-9-THC are attributed primarily to the compound’s actions as a cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) agonist (NASEM, 2017).

Cannabidiol (CBD): CBD is not a CB1 receptor agonist and does not engender the constellation of effects of delta-9-THC. Epidiolex®, a purified form of CBD, is approved for oral administration by the FDA for the treatment of specific seizure disorders in patients 1 year of age or older. There is tremendous consumer interest in CBD’s therapeutic benefits. However, its off-label benefits are not well studied, and CBD can elicit side effects such as dry mouth, diarrhea, reduced appetite, drowsiness, and fatigue. CBD can also interact with other medications, such as blood thinners (Huestis et al., 2019).

Cannabinoids can be classified based on how they are derived:

Naturally occurring: Cannabinoids such as delta-9-THC and CBD, as well as cannabigerol (CBG), cannabichromene (CBC), pure hemp seed oil, and pure hemp protein powder, are naturally derived from the cannabis plant.

Semisynthetic: Semisynthetic cannabinoids are derived by chemically altering natural cannabinoids, such as CBD. Some may occur naturally in the plant at very low concentrations, such as delta-8-THC. Examples of semisynthetic cannabinoids include delta-8-THC, delta-10-THC,

tetrahydrocannabiphorol (THCP), THC-O-acetate, tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV), and hexahydrocannabinol (HHC). Some semisynthetic cannabinoids, particularly THC isomers, produce effects similar to those of delta-9-THC, in part because of their actions as CB1 receptor agonists (Cooper and Haney, 2008).

Synthetic: Synthetic cannabinoids are not derived from the cannabis plant. Some of these compounds that are available on the unregulated drug market, like the compounds identified in illicit synthetic cannabinoid products such as K2 or Spice, are highly potent and intoxicating.

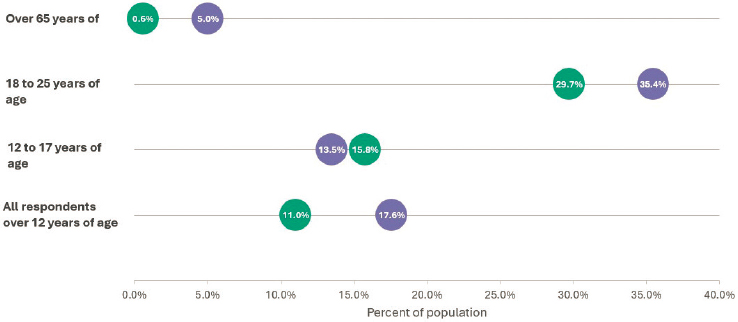

increase in past-year cannabis use for the same population appears to have continued from 2021 (19.1 percent) to 2022 (21.9 percent) (Figure 1-3). One important change is the increased prevalence of use among adults over age 65. In 2002, only 0.6 percent of adults over age 65 reported using cannabis in the past year; by 2019, that figure had risen to 5 percent, although this increase could be due to the aging of the population that uses cannabis. On the other hand, NSDUH estimates of past-year use are relatively constant across time for 12- to-17-year-olds. The percentage of 12- to 17-year-olds who used cannabis in the past year decreased

NOTE: Dot and dashed lines represent changes in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) survey design and method of administration.

SOURCE: Generated by Seema Hemant Choksy Pessar, consultant to the committee using data estimated from the NSDUH.

NOTES: Includes all age groups except 12- to 17-year-olds. Green dots = 2002; purple dots = 2019.

SOURCE: Generated by the committee using data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health analyzed by Seema Hemant Choksy Pessar, consultant to the committee.

slightly from 2002 to 2019 (Figure 1-4) and remained consistent in 2021 (10.8 percent) and 2022 (11.4 percent). It is also important to note that cannabis use is socially stratified. Those with a college education have the lowest prevalence of use; additionally, those at or below the poverty line have a higher prevalence of use than those with two times the federal poverty level (see Chapter 3). It is important to note as well that national estimates of the prevalence of cannabis use may not represent what is occurring within states where cannabis has been legalized.

There are many types of cannabis products, which can be consumed through many routes of administration. The most common approach to using cannabis is by inhalation following either combustion (e.g., smoking cannabis flower or hashish, commonly rolled together with tobacco in European countries) or vaporization (e.g., heating oils, waxes, or plant material) (Figure 1-5).4 Cannabis can also be consumed orally (e.g., pills, capsules, edibles, beverages), while other products are manufactured to be absorbed through the skin (e.g., lotions, oils) or other membranes (e.g., suppositories). Cannabis products differ based on the concentration of delta-9-THC or the other cannabinoids that they contain.

___________________

4 While flower products are typically consumed via smoking, it is also possible to vaporize them.

NOTES: Top left quadrant, right to left: honey butane wax, cannabis flower, hashish, and cannabis concentrate resin. Top right: cannabis vapes. Bottom left: rolled cannabis. Bottom right: Cannabis flowers, tinctures, and edibles.

SOURCES: Drug Enforcement Agency images (top left quadrant), Shutterstock (top right and bottom left quadrants), iStock (bottom right quadrant).

PHARMACOKINETICS AND METHOD OF ADMINISTRATION

Several factors may impact the effects of cannabis use (Box 1-2), including pharmacological factors such as the route of administration, the dose of THC consumed, and an individual’s tolerance (Brunton and Knollmann, 2022; Pomahacova et al., 2009; Spindle et al., 2018). The ratio of THC to CBD or other cannabinoids also may influence the effects of cannabis (Freeman et al., 2019; Zeyl et al., 2020). Other factors impact a person’s likelihood of developing a harmful relationship with cannabis, such as the person’s mindset or the setting in which the drug is consumed (Becker, 1953; Vakharia, 2024).

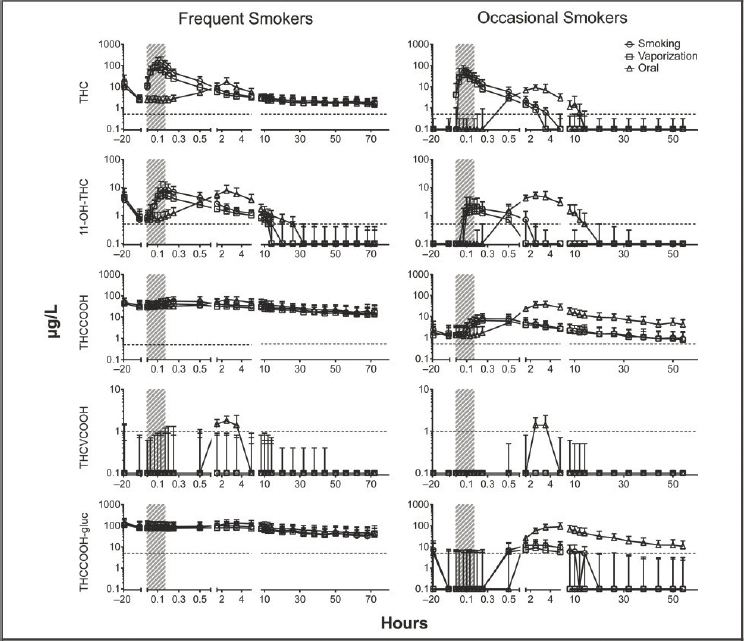

The route of administration impacts the intoxicating effects of cannabis. Inhalation rapidly delivers THC from the lungs to the brain and results in effects being felt in seconds to minutes and intoxicating effects lasting for 1–3 hours. The route of administration influences cannabinoid absorption, metabolism (pharmacokinetics), and effects. Delta-9-THC is rapidly absorbed by the lungs and brain after inhalation, producing near-instantaneous effects that dissipate 2–3 hours after exposure. When smoking cannabis, much of the delta-9-THC is lost to sidestream smoke and pyrolysis (see Box 1-2; NIDA,

BOX 1-2

Pharmacological Terms Important to Understanding Cannabis Intoxication

Concentration or strength: “Concentration” refers to the relative amount (percent) of the active ingredient, typically delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), per weight or volume (Brunton and Knollman, 2022). Potency: Much of the cannabis literature colloquially uses the term “potency” to refer to the concentration of delta-9-THC in a cannabis product. In pharmacology, however, “potency” refers to an inherent pharmacological characteristic of a drug that defines the amount (dose) required to achieve a certain effect (Brunton and Knollmann, 2022). Within the framework of pharmacological principles, the potency of delta-9-THC is constant regardless of the finished product or preparation. Different forms of THC may have different potencies because of different levels of agonism for the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) receptor. For example, tetrahydrocannabiphorol (THCP) is more potent than delta-9-THC.

Dose: Dose is the amount of a cannabinoid administered at a given time. The route of administration can impact the dose consumed. If an entire edible is consumed, the dose is equal to the milligrams of delta-9-THC in the edible. It is more challenging to determine dosing when smoking or vaping cannabis. An estimated 70 percent of the delta-9-THC is lost to sidestream smoke and pyrolysis during cannabis smoking (Pomahacova et al., 2009). Vaporizing cannabis (vaping) is a more efficient delivery method. Still, some THC is lost to sidestream smoke when vaping (Spindle et al., 2018).

Tolerance: Tolerance occurs when people use a drug regularly and it loses its effect over time. Tolerance is observed among those who use cannabis frequently, and they require higher doses of the drug to experience its effects.

1990; Pomahacova et al., 2009), whereas vaping cannabis yields significantly higher delta-9-THC concentrations absorbed into the bloodstream (Budney et al., 2024; Pomahacova et al., 2009; Van der Kooy et al., 2008). These differences result in higher delta-9-THC blood levels and more pronounced intoxicating effects after vaping compared with smoking for the same sample of cannabis (i.e., sample weight and delta-9-THC concentration) (Spindle et al., 2018). Differences in metabolism can also influence the differences in effects of delta-9-THC between inhaled and oral modes of administration.

Oral ingestion results in slower absorption and more delayed peak concentrations. Ingestion can take roughly 30 minutes to 2 hours to induce intoxicating effects, which can be felt for 5–8 hours (Huestis, 2007;

Jernigan et al., 2021; NASEM, 2017). Oral delta-9-THC administration undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver, leading to slower absorption of delta-9-THC and its active metabolites (see Figure 1-6). Effects after oral delta-9-THC administration are delayed and prolonged compared with inhalation, with peak effects occurring about 60 minutes after ingestion and lasting 4–12 hours, depending on a variety of factors, including dose and drug preparation (Karschner et al., 2009; Newmeyer et al., 2016, 2017; Sholler et al., 2021).

NOTES: Shaded area designates 10-minute smoking times. The dotted line is the limit of quantification data presented on a log scale. delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC); 11-hydroxy-THC (11-OH-THC); 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC (THCCOOH); 1-nor-9-carboxy-THCV (THCVCOOH); 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC-glucuronide (THCCOOH-gluc).

SOURCE: Newmeyer et al., 2016, by permission of Oxford University Press.

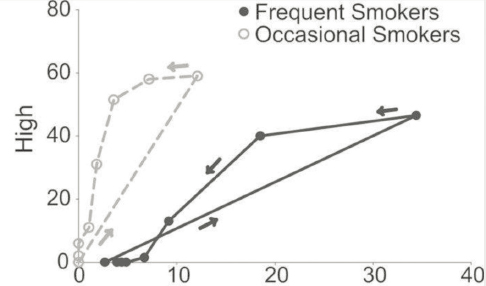

Different pharmacokinetic profiles may contribute to differences in the positive or adverse outcomes of cannabis use across product types and delivery methods. For example, hospital emergency visits due to cannabis-induced intoxication, acute psychiatric symptoms, and cardiovascular incidents occur more often with oral administration relative to inhalation (Monte et al., 2019; Muheriwa-Matemba et al., 2024). Additionally, pharmacokinetics and intoxicating effects of delta-9-THC vary as a function of demographic variables, such as sex, age, and frequency of cannabis use. In people who use cannabis frequently, for example, cannabis consumption results in more significant blood THC levels but less intoxication compared with people who use cannabis occasionally (Figure 1-7). Men and women also metabolize delta-9-THC differently and exhibit varying effects from cannabis on such measures as anxiety and abuse liability (Desrosiers et al., 2015) (Figure 1-7). These differences impact acute and long-term risks associated with cannabis use among these demographic groups (Budney et al., 2024; Chiang and Hawks, 1990; Cooper and Haney, 2014; Lake et al., 2023; Pomahacova et al., 2009; Sholler et al., 2021; Van der Kooy et al., 2008).

Some forms of cannabis contain very high concentrations of delta-9-THC; these forms are often referred to as concentrates and are called dabs, wax, and shatter. Concentrates usually contain 60 percent delta-9-THC but can contain as much as 90 percent delta-9-THC and are of public health concern (Bero et al., 2023; Hasin et al., 2023). No systematic pharmacokinetic comparisons have been made between inhalation of delta-9-THC by

SOURCE: Desrosiers et al., 2015. Copyright © 2015, Published by Oxford University Press 2015. This work is written by (a) U.S. government employee(s) and is in the public domain in the United States.

combustion of plant material (smoking) versus inhalation of concentrates. Nonetheless, the highly concentrated nature of dabs, wax, and shatter makes it possible to consume a higher dose of delta-9-THC because more of the intoxicating compound is delivered in a much smaller volume of product relative to plant material (Loflin and Earleywine, 2014; Raber et al., 2015), although the dose can be titrated. Concentrates are also heated to a very high temperature (Raber et al., 2015), producing highly concentrated vapor or aerosols that can be administered in few inhalations, whereas smoked cannabis requires the combustion of a relatively larger volume of material (Loflin and Earleywine, 2014; Raber et al., 2015).

FEDERAL ROLE IN CANNABIS POLICY

The federal role in cannabis policy is complex. As noted earlier, although now widely available in most states, cannabis has been classified as Schedule I under the CSA (PL-91-513), the primary policy in the United States for control of illicit drugs, from 1970, when the act was first passed, through the time of this writing (June 2024), although the Biden administration has recommended that it be rescheduled to Schedule III. Since cannabis is a Schedule I drug under the CSA, its manufacture, distribution, or possession remains a criminal violation under federal law, enforceable by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and other law enforcement agencies. The ability of states to implement cannabis policies stems from the concept of federalism, or “the division and sharing of power between the national and state governments” (CRS, n.d., para. 1). Other countries where cannabis is legal, such as Canada and Uruguay, have had much more involvement from their federal governments (see Chapter 2 for comparisons with other countries). The end of this chapter provides a more detailed history of cannabis policy in the United States.

Department of Justice Actions Toward State Cannabis Policy

The Ogden Memo was written in 2009 to address uncertainty regarding the federal role in enforcing cannabis policy in states that were early to legalize cannabis for medical use. It emphasized that because federal criminal enforcement typically is concerned with large-scale illicit drug trafficking, federal prosecutors generally should not focus on “individuals whose actions are in clear and unambiguous compliance with existing state laws providing for the medical use of marijuana” (Ogden, 2009, p. 2). The Ogden Memo also noted, however, that federal prosecutors should be concerned with cannabis activity connected to unlawful firearm possession, violence, sales to minors, illegal possession of other drugs, and ties to other criminal activity.

The Ogden Memo was followed by the Cole Memo in 2013, issued in response to the legalization of cannabis for adult use in Colorado and Washington. It stressed that federal prosecutors should “focus . . . efforts on certain enforcement priorities that are particularly important to the federal government” (Cole, 2013, p. 1). The priorities included distributing to minors, funding criminal organizations, crossing state lines, being a cover for other crimes, fueling violence, impairing driving, cultivating public lands, and possessing or using public property; it also emphasized that criminal prosecution should not be prioritized for individuals compliant with state laws (Cole, 2013). Later, Attorney General Sessions (2018) rescinded the Cole Memo, giving federal prosecutors the power to enforce federal cannabis laws in states that had legalized cannabis. This shift created uncertainty for the cannabis industry in those states, although later, Attorney General Barr stated he would not prosecute companies complying with the Cole Memo, and Congress has withheld money from the Department of Justice for cannabis prosecutions (Patton, 2020). Another federal policy action began in 2014 when Congress passed an appropriations rider, which prohibited the Department of Justice from using taxpayer dollars to enforce laws against medical cannabis programs (Lampe, 2024).

2018 Agriculture Improvement Act

The 2018 Agriculture Improvement Act (PL-115-334), often called the 2018 Farm Bill, has created enormous regulatory confusion concerning the legality of cannabinoids. This bill revised the definition of “hemp” so the crop could be sold legally without being subject to the CSA (Gottron et al., 2019). The 2018 Farm Bill defines “hemp” as “the plant Cannabis sativa L. and any part of that plant, including the seeds thereof and all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids, isomers, acids, salts, and salts of isomers, whether growing or not, with a [delta-9-THC] concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis” (PL-115-334, § 297A). This definition has created legal uncertainties that have facilitated the production and sale of cannabinoids derived from hemp, creating a lucrative industry (Skodzinski, 2024) that is largely unregulated and competes with the regulated state-legal cannabis industry (Johnson, 2023; Johnson and Willner, 2023). The inclusion of the terms “all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids, isomers, acids, salts, and salts of isomers” has led to the sale of intoxicating cannabis products, especially in states that have not chosen to legalize cannabis (Demko, 2024).

State legislators and regulatory bodies are grappling with the challenge of regulating the burgeoning market for hemp-derived THC derivatives. Efforts to restrict their sale have been met with legal resistance. Court rulings on the issue have thus far been inconsistent, leaving the extent of

state regulatory authority unclear. A recent example is a preliminary injunction issued by a federal judge in Arkansas, which halted the implementation of a state law banning intoxicating hemp products (Demko, 2024). As of November 2023, 17 states had successfully banned delta-8-THC, and 7 had severely restricted its sale (Johnson and Willner, 2023). Recently, a bipartisan group of state attorneys general wrote to Congress asking it to act regarding what they term intoxicating hemp products and expressing concern that a public health crisis is looming (Demko, 2024; Elbein, 2024). Although the 2025 Agricultural Improvement Act may include an updated definition of “hemp” to encompass only nonintoxicating products, which would help address this confusion, that new Farm Bill had not passed as of July 2024 (Johnson, 2024).

Revised Cannabis Scheduling under the Controlled Substances Act

In 2022, the executive branch announced that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Justice would review the scheduling of botanical cannabis5 under the CSA (White House, 2022). Drug scheduling is a complex science policy process. HHS conducts an evaluation and makes a scheduling recommendation to the DEA in the form of an “eight-factor analysis” in accordance with the CSA (21 USC §§ 811[a–c], 812[b]). The eight-factor analysis weighs a drug’s potential for abuse, scientific backing, public health risks, dependence potential, and history of use. The analysis results inform decisions required for a drug scheduling recommendation, which reflects the drug’s potential for abuse, whether it has a federally accepted medical use in the United States, and its relative safety or ability to produce physical dependence compared with other drugs, as provided under 21 USC § 812(b). The process used by HHS to determine whether cannabis has a currently accepted medical use differed from that used in prior attempts to reschedule cannabis. Typically, currently accepted medical uses are determined using criteria that are most applicable to a drug with ample evidence from clinical trials. The usual approach to evaluation of a currently accepted medical use “left no room for an evaluation of (1) whether there is widespread medical use of a drug under the supervision of licensed health care practitioners under State-authorized programs and, (2) if so, whether there is credible scientific evidence supporting such medical use” (21 CFR Part 1308.2). As a result, HHS used a two-factor analysis to take into account the current widespread medical use of cannabis under

___________________

5 Cannabinoid drugs fall within different areas of the CSA. Cesamet™ (nabilone), synthetically derived delta-9-THC in a powder form, is Schedule II, and Marinol® (dronabinol), synthetically derived delta-9-THC in liquid form, is Schedule III. Epidiolex, highly purified naturally derived cannabidiol, is Schedule V (DOJ/DEA, 2020).

the supervision of clinicians under state-authorized programs (21 CFR Part 1308.2; Budney et al., 2024).

Following its review, in August 2023, HHS recommended that the DEA change the scheduling of cannabis from Schedule I to Schedule III, and on April 30, 2024, the DEA announced that it accepted HHS’s proposal (HHS, 2023; Lampe, 2024; Miller et al., 2024). The change would have significant consequences should the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) approve that recommendation. Businesses in the legal cannabis industry cannot deduct many business expenses from their federal taxes. Rescheduling could change that situation because the limitations on federal tax deductions apply only to Schedule I and II substances. Moreover, cannabis is currently banned from interstate commerce, and a change to federal scheduling could make federal authorities less inclined to target cannabis businesses that transact cross-border sales (Sacirbey, 2023).

The most significant benefit of rescheduling cannabis from Schedule I to Schedule III would be in the reduction of, but not elimination of, the barriers to medical research on the therapeutic impacts of the plant (Wallack and Hudak, 2016). Schedule III drugs do not require separate researcher registration and have less stringent laboratory controls and more limited reporting requirements; therefore, more researchers may be willing to conduct research on the drug (Wallack and Hudak, 2016).

Rescheduling cannabis would create additional policy confusion. First, changing the schedule of cannabis would not make botanical cannabis a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved prescription drug; FDA drug approval entails a different application process. Second, the state medical programs would still operate in violation of the CSA. Schedule III substances have accepted medical uses but have federal requirements for prescription and sale that differ significantly from the methods used in most state medical cannabis programs (Lampe, 2024). Schedule III substances require FDA approval before they can be prescribed by a physician and marketed as a medication. Moreover, if one or more cannabis products obtained FDA approval, manufacturers and distributors would need to register with the DEA and comply with regulatory requirements that apply to Schedule III substances. Cannabis users would need to obtain valid prescriptions for the substance from clinicians and obtain cannabis from a pharmacist (Lampe, 2024).

Exactly how the rescheduling of cannabis to Schedule III would impact state medical programs is unknown and would depend on how the FDA managed the rescheduling and how the courts interpreted the law. Assuming there was no further act by Congress to legalize cannabis, its supply and adult use would remain illegal under federal law, penalties would decrease, and medical access might increase across the states (since the federal government would have determined that cannabis has a currently accepted medical use).

Overall, then, rescheduling of cannabis is a complex issue. Although the DEA had accepted the HHS proposal to reschedule cannabis as of April 2024, reclassification is still in the early stages. The DEA must wait for review of the decision by the OMB, a period of public comment on the decision, and review by an administrative judge before posting the final rule on rescheduling (Lampe, 2024; Miller et al., 2024).

STUDY CHARGE AND APPROACH

The need for a comprehensive public health review of cannabis policy prompted the CDC and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to commission the National Academies to convene an ad hoc committee charged with describing cannabis and cannabinoid availability in the United States; assessing regulatory frameworks for the cannabis industry, with an emphasis on equity; and describing strengths and weaknesses of medical and nonmedical surveillance systems for cannabis. The committee was asked to recommend a strategy for minimizing harms associated with cannabis policy and set a policy research agenda for the next 5 years. The committee’s statement of task is provided in Box 1-3. The committee included experts in public health surveillance, drug policy, epidemiology, policy analysis, neuroscience, health equity, pharmacoepidemiology, public policy, economics, psychiatry, psychology, pediatrics, and history (see Appendix A for the full biography of the committee members).

Interpretation of the Statement of Task

Notably, the statement of task does not ask the committee to conduct a comprehensive review of the health effects of cannabis that would update the 2017 National Academies report (NASEM, 2017). Instead, the committee was asked to review the public health impacts of changes in cannabis policy, an area omitted from the charge to the 2017 committee. The National Academies has not reviewed cannabis policy for more than 40 years. The prior report on that topic, An Analysis of Marijuana Policy, was prompted by increases in cannabis use and suggestions for policy reforms (NRC, 1982). The committee that produced that report recommended considering alternative policies, including partial prohibition, as well as further research on the effects of cannabis use and different policy approaches (NRC, 1982). Given the many changes in cannabis policy since the publication of the 1982 report, an update is sorely needed.

This committee did not consider decisions about cannabis legalization, scheduling, or prohibition to be within its purview. Instead, the committee believed its task was to address the question: Now that states have been legalizing cannabis, what public health measures should be undertaken to protect public health?

BOX 1-3

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will review the public health impacts of cannabis and cannabinoid use, both medical and non-medical, among adults in the states and localities where it is legal. Specifically, the committee will:

- Describe the status of cannabis availability and use, including various product types (e.g., concentrates, edibles, dabs, vaping cartridges) and component cannabinoids (e.g., cannabidiol) in the US. Assess how different regulatory models have influenced the makeup of the cannabis industry, as well as product safety, composition and potency, dosage/serving size, availability, quality control, and labeling and marketing.

- Discuss the implications for public health of the various regulatory models. Where relevant, describe how lessons from other countries and from tobacco, alcohol, and other regulated products or industries can inform U.S. regulations and whether they have or have not been applied.

- Assess these regulatory frameworks through a social and equity lens, exploring outcomes such as employment, tax revenues, and other economic indicators; environmental impact of the cannabis and hemp agriculture; encounters with the justice system; impact on the unregulated market; and availability of community prevention and treatment resources for cannabis use disorder. Include, as appropriate social and equity impact of decriminalization and incarceration for cannabis possession.

- Describe strengths and weaknesses of existing state or national surveillance and pharmacovigilance systems for adult and medicinal use and other data sources and identify key public health outcomes that could serve as sentinels for adverse exposure and health consequences. Such outcomes might include, but are not limited to, harmful exposures, adverse cancer outcomes and interactions with cancer treatments, low-birth weight, motor vehicle accidents, worker impairment and injury, poisonings in children, hospitalizations for acute mental health problems or for cardiovascular disease, indoor air quality, and use/co-use of other substances including alcohol and tobacco. Review what is known about whether these outcomes have changed in states and localities that have changed their regulatory approach to cannabis and cannabinoids. Data sources may include information on the medical conditions for which cannabis is prescribed by physicians or recommended by dispensaries, self-reported reasons for cannabis use, and beneficial health outcomes.

- Make comparisons throughout, as appropriate, to the illicit unregulated market.

- Provide recommendations for strengthening a harm reduction approach, which would minimize harms, of various regulatory models, including but not limited to social, employment, education, and health impacts.

- Make recommendations for policy research for the next 5 years.

Although the committee was asked to develop recommendations related to “strengthening a harm reduction approach, which would minimize harms, of various regulatory models, including but not limited to social, employment, education, and health impacts” the committee interpreted that task more broadly. It identified “harm reduction” as a series of approaches that reduce health and safety consequences for individuals and society associated with drug use or other behaviors (Vakharia, 2024). Additionally, while harm reduction services and approaches can have important implications for public health, the committee believed a broader set of recommendations, or a public health approach, was needed to respond to its statement of task.

Finally, although the statement of task refers explicitly to “adults,” the committee determined that any public health approach to cannabis policy would need a significant focus on youth. It is well known that for other substances, experimentation in adolescence may lead to lifelong use, which increases the potential for impacts on health and well-being.

Study Approach

The committee developed its public health approach to cannabis policy based on the published literature and the presentations and discussions during its large public meetings in fall 2023 and winter 2023–2024. In these public sessions, the committee heard from various stakeholders, including the CDC, NIH, and FDA; state cannabis regulators; public health officials; people impacted by adverse outcomes of cannabis use; those who grow cannabis and make cannabis products; and academic researchers studying cannabis policy, health effects, harm reduction, treatment, and primary prevention.

Social equity is central to the committee’s statement of task. This area often focuses on addressing racism and other forms of discrimination, but it is highly intertwined with health equity. Systems of power (which are influenced by social equity), individual factors, and physiological pathways all influence health equity. “Systems of power” are policies, processes,

and practices that determine who gets resources and better opportunities for health. These systems can promote health equity or perpetuate inequities in such areas as access to basic needs, humane housing, meaningful work, and reliable transportation. “Individual factors” concern people’s responses to social, economic, and environmental conditions through their attitudes, skills, and behaviors and the interaction of those factors with biological predisposition. “Physiological pathways” refers to a person’s biological, physical, cognitive, and psychological abilities (Peterson et al., 2021). The committee considers these issues throughout this report.

In carrying out this study, the committee considered the core public health functions (Box 1-4). A public health approach to cannabis policy

BOX 1-4

Public Health Approach to Cannabis Policy

Assessment

- Conduct surveillance of or assess and monitor the health impacts of cannabis.

- Investigate the causes of any identified harms from cannabis use.

Policy Development

- Build and mobilize partnerships between cannabis regulators and public health authorities.

- Inform, educate, and empower communities to develop cannabis-related public health campaigns.

- Develop cannabis policies centered on protecting public health that are not influenced by the regulated industry.

- Equitably enforce cannabis policies designed to ensure compliance.

Assurance

- Protect the public from the potential harms of cannabis (accidental ingestion or poisoning, crashes from impaired driving, secondhand smoke, and environmental impacts).

- Protect those who use cannabis from potential harm and ensure access to treatment.

- Build and support a diverse and skilled cannabis public health workforce.

- Improve and innovate cannabis public health functions through ongoing evaluation, research, and continuous quality improvement.

- Build and maintain a strong organizational infrastructure for cannabis and public health.

SOURCE: Adapted from Ghosh et al., 2016.

differs from other public policy–making approaches. Public health policy aims to improve the health of entire communities, not just individuals, which requires considering factors that influence health outcomes for large groups, such as access to healthy food or safe environments (Castrucci, 2021; Jernigan et al., 2021). Ideally, public health decisions are based on scientific research and data on the most effective interventions for preventing disease and promoting health within communities. Public health policy must often balance individual freedoms with promotion of the greater good. For example, smoking restrictions limit the personal choice of the smoker but reduce unhealthy exposures for everyone. Public health issues often are complex, requiring collaboration among government sectors such as education, transportation, and housing. Public health policy development also requires understanding community needs and wants and considering the economic impact, feasibility, and acceptability of implementing policies and programs. Public health policy is meant to be more preventive than reactive, aiming to prevent health problems before they occur.

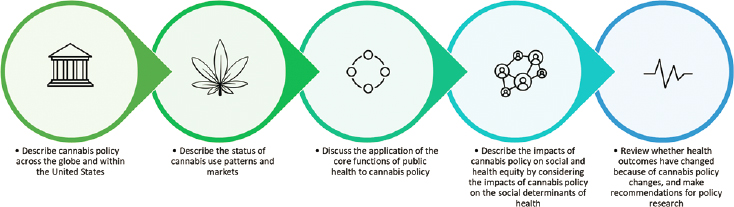

Public health can inform many aspects of cannabis policy, such as policies on how cannabis is cultivated, processed, marketed, or sold, in addition to where it is sold and marketed, to whom, in what type of packaging, and under what circumstances. Public health policies can similarly target consumers, directly regulating how and where products can be consumed and under what circumstances. In intervening in these areas, the goals of public health policy are to mitigate the harms of legal markets while promoting the benefits of cannabis (Figure 1-8).

The committee found it difficult to delineate the differences between medical and adult-use policies and their public health consequences; therefore, this report focuses primarily on policies that legalize possession and some forms of supply to adults. Additionally, the two categories of use overlap across different policy regimes. Some people living in states with legal adult use will purchase cannabis without a recommendation from a medical provider to self-medicate for trouble sleeping or to unwind. On the other hand, some states with medical programs have such relaxed policies for obtaining cannabis for medical use that they do not differ significantly from adult-use states

(Pacula et al., 2014). Another source of confusion in any policy analysis is that the legal uncertainties posed by the 2018 Farm Bill have led to the availability of cannabis in most states (CANNRA, 2023; Elbein, 2024; Gottron et al., 2019; Johnson, 2023; Johnson and Willner, 2023; Rossheim et al., 2024).

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

Figure 1-9 provides an overview of the steps taken by the committee to address its charge. The report is organized around this framework. Following the overview of the study’s public health and social context in this chapter, Chapter 2 reviews the U.S. approach to cannabis policy making compared with those of other countries. Chapter 3 examines cannabis use and markets in the United States. Chapter 4 applies core public health concepts to cannabis policy and considers how the harms associated with that policy can be mitigated. Chapter 5 describes the impacts of cannabis policy on social and health equity. Finally, Chapter 6 reviews the literature evaluating the public health impacts of cannabis policy and provides research recommendations.

HISTORY OF CANNABIS POLICY IN THE UNITED STATES

Discussion of public policies related to cannabis use depends on a comprehensive understanding of the drug’s chemistry and physiological effects. As mentioned previously, the plant itself and the products derived from it have evolved over the past few decades. However, because public policy is influenced by historical context as well, a review of the history of cannabis policy is essential for understanding the current U.S. policy landscape.

Early State Cannabis Control Policies, ~1860s to ~1940s

For much of U.S. history, state governments have led the way in cannabis regulatory activity, building on traditions of local control of public health and safety and given constitutional authority under the 10th Amendment. State legislative activity has generally preceded corresponding federal policies.

Consumer protection laws governing the sale of dangerous drugs first emerged in the 1860s, and the earliest of these (New York in 1860 and Wisconsin in 1862) included cannabis in the substances placed under regulatory control (Rathge, 2017). Despite pressure for uniform rules across states, individual legislatures generally retained control, so cannabis legislation varied widely among states. In 1911, Massachusetts became the first state to restrict cannabis possession as states began to move from a consumer protection regulatory framework to a more explicit effort to prohibit all nonmedical sales and possession (Rathge, 2017). Moves by state legislatures and some local governments to effectively ban nonmedical cannabis in the first three decades of the 20th century were rooted in multiple impulses, including anti-immigrant sentiment toward Mexicans, a growing temperance movement intolerant of intoxicants such as cannabis and alcohol, and social elitism (Belenko, 2000; Courtright, 2012; Musto, 1991). Recent detailed historical accounts raise questions regarding the prominently hypothesized role of explicit racism in early legislative enactments of these state laws, concluding that the shift from regulation to prohibition was deeply influenced by anxiety over cannabis use among youth and moralistic concerns regarding the effects of cannabis intoxication, including a perceived link to violence and madness (Campos, 2018; Fisher, 2021). But it is undeniable that racism played a role in the unequal enforcement and implementation of prohibition once it became enacted.

By the time of the federal Marijuana Tax Act in 1937, every state had passed some version of prohibition of nonmedical cannabis (Fisher, 2021). A movement toward more uniform state laws produced a draft narcotic act in 1925, which included cannabis prohibitions that were left to the discretion of the states in later drafts (Bonnie and Whitebread, 1974). Even today, an emphasis on states’ authority is at the root of considerable variation in cannabis policy across the country.

Evolution of Federal Control Policies

For as long as federal drug regulation has existed, cannabis has been part of it. The 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act, for example, required label disclosure of 11 dangerous drugs, including cannabis (Jernigan et al., 2021; Young, 1989). Nine years later, the Treasury Department banned the importation of cannabis for purposes other than medical (Campos, 2018). Both federal actions assumed a medical market for cannabis that was protected by law. Well into the 1930s, U.S. pharmaceutical firms continued to cultivate cannabis and produce cannabis products for medical use. Over time, the need for a reliable supply of a product of uniform quality prompted the transition to domestic cultivation. Historical research suggests that, while this medical market was durable, having started in the 1840s, it was neither large nor growing, as physicians gradually came to favor medicines produced under standardized laboratory conditions that required far less paperwork to prescribe.

The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 imposed a tax on cannabis, most notably on its import and export, but also on its cultivation, sale, and possession (CBP, 2019). As noted above, the 1937 federal law followed, rather than preceded, most state-level cannabis control laws. Recent scholarship grounded in the archival and documentary evidence suggests further that federal legislation was spurred in part by the felt need to protect domestic production of hemp as a strategic material for national defense without its diversion for adult use (McAllister, 2019). In addition, while the promotion of public support for passage of the Marijuana Tax Act played upon racially coded fears of criminality, there appears to have been little initial investment in federal enforcement capacity (Galliher and Walker, 1977; McAllister, 2019).

Although the 1937 act ostensibly protected medical use, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) (the predecessor of the DEA pressed for the demedicalization of cannabis. The removal of cannabis from the U.S. Pharmacopeia in 1942 followed several years of active lobbying against its medical legitimacy by FBN chief Harry Anslinger (Rathge, 2017). U.S. officials also participated in international efforts to demedicalize cannabis, such as the 1952 statement from the World Health Organization (WHO, 1952) Expert Committee on Habit-Forming Drugs that there was “no justification for the medical use of cannabis preparations” (p. 11) and WHO’s 1955 report The Physical and Mental Effects of Cannabis, which concluded, “not only is marihuana [sic] smoking per se a danger but [its] use eventually leads the smoker to turn to intravenous heroin injections” (as quoted in Bewley-Taylor et al., 2014, p. 21).

Controlled Substances Act of 1970

The incorporation of cannabis into a comprehensive system of federal drug regulation occurred relatively late, with the adoption of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 (PL-91-513). The CSA was part of a larger package of federal drug legislation that consolidated the patchwork of existing federal drug laws and created a series of five schedules into which controlled substances would be placed (see Box 1-5). Scheduling assignments were based on a drug’s or chemical’s potential for abuse or dependence, as well as federally accepted medical use, and guided regulation of the manufacturing, distribution, and possession of the scheduled chemicals. Cannabis was classified among the Schedule I drugs, reflecting the decades-long process of its demedicalizing, as well as the judgments of then-president Richard Nixon and Attorney General John Mitchell, both of whom opposed cannabis and saw it as a gateway to use of more dangerous drugs and an unproductive lifestyle, as well as being closely associated with political and social radicalism (Downs, 2016).6

___________________

6 An early version of scheduling, the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961), had also controlled cannabis in the most stringent schedules, reserved for substances with serious risk of abuse and extremely limited medical or therapeutic value.

BOX 1-5

Schedules of Drugs in the Controlled Substances Act

- Schedule I drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Some examples of Schedule I drugs are heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), marijuana (cannabis), 3,4-Methylene-dioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy), methaqualone, and peyote.

- Schedule II drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with a high potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence. These drugs are also considered dangerous. Some examples of Schedule II drugs are combination products with less than 15 milligrams of hydrocodone per dosage unit (Vicodin), cocaine, methamphetamine, methadone, hydromorphone (Dilaudid), meperidine (Demerol), oxycodone (OxyContin), fentanyl, Dexedrine, Adderall, and Ritalin.

- Schedule III drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with a moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence. Schedule III drugs have less potential for abuse than Schedule I and Schedule II drugs, but more than Schedule IV drugs. Some examples of Schedule III drugs are products containing less than 90 milligrams of codeine per dosage unit (Tylenol with codeine), ketamine, anabolic steroids, and testosterone.

- Schedule IV drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with a low potential for abuse and low risk of dependence. Some examples of Schedule IV drugs are Xanax, Soma, Darvon, Darvocet, Valium, Ativan, Talwin, Ambien, and Tramadol.

- Schedule V drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with lower potential for abuse than Schedule IV drugs, and consist of preparations containing limited quantities of certain narcotics. Schedule V drugs are generally used for antidiarrheal, antitussive, and analgesic purposes. Some examples of Schedule V drugs are cough preparations with less than 200 milligrams of codeine or per 100 milliliters (Robitussin AC), Lomotil, Motofen, Lyrica, and Parepectolin.

SOURCE: DEA, 2020.

National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse, 1972

The CSA authorized the creation of a National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse, known popularly as the Shafer Commission. The commission’s final report, released in 1972, strongly recommended state and federal decriminalization of the possession of small amounts of cannabis for personal use (Nahas and Greenwood, 1974). The same report

encouraged the NIH and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to consider supporting cannabis research. In the same year, the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws filed a petition with the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (now the DEA) to reschedule cannabis to Schedule II, enabling legal physician prescription. That petition ultimately failed, as did subsequent petitions to do the same in 1995, 2002, and 2011.

Interest in the therapeutic utility of cannabis reemerged in the 1960s and 1970s, spurred on the laboratory front by the isolation of THC in 1964 and the synthesis of THC in 1967, and more popularly by advocacy from patient groups and a renewed appreciation of plant-based medicine (Dufton, 2017; Taylor, 2008, 2022). In 1978, the Compassionate Investigational New Drug (IND) program allowed access to medical cannabis for a limited number of patients (Clark et al., 2011). Nevertheless, federal policy on medical cannabis saw only modest changes in the later 1970s.

Federal Approvals of Cannabinoid Drugs, 1980 to the Present

Federal approval of synthetic cannabinoids for medical use represented the next policy evolution in the remedicalization of cannabis. In 1980, the National Cancer Institute supported the use of dronabinol as an investigational antinausea drug for chemotherapy patients (Sawtelle and Holle, 2021). In 1985, the FDA approved dronabinol to treat nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy (IOM, 1999). FDA approvals since then include other indications and formulations for dronabinol, the THC analog nabilone, and cannabidiol (FDA, 2023; Todaro, 2012).

Cannabis for Research

Research supporting the process of cannabis remedicalization has long been hindered by significant problems in obtaining reliable supplies of raw material for study (Taylor, 2022). In 2020, a change in DEA rulemaking allowed for multiple sources of cannabis supply for researchers, who for more than a half-century had relied solely on a single federally approved source at the University of Mississippi (DEA, 2020). Now, several other cultivation facilities have DEA licenses,7 but they may not yet meet federal research requirements imposed by the FDA. Federal support of medical cannabis research received further attention with the passage of the Medical Marijuana and Cannabidiol Research Expansion Act of 2022, which aims to encourage medical research on cannabis (Purcell et al., 2022).

___________________

7 https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugreg/marihuana.html (accessed August 10, 2024)

State Cannabis Policies Since 1973

Passage of the CSA standardized federal policy around cannabis and other controlled substances. Almost immediately afterward, state-level policy initiatives emerged to challenge the federal government’s presumed policy dominance.

State-Level Decriminalization, 1973–1978

In the 1970s, states began to adopt policies following the Shafer Commission’s recommendation that possession of cannabis for personal use be decriminalized. Although sometimes mistakenly used interchangeably, decriminalization and legalization are different policy options (see Box 1-6). The movement for state-level decriminalization began in Oregon in 1973 with the elimination of criminal penalties for the possession of less than 1 ounce of cannabis, which was instead subject to a $100 civil fine. Ten more states adopted so-called decriminalization laws in the 1970s and early 1980s. However, these laws varied widely in the quantities designated as permissible, terms for punishing repeat offenders, and even the inclusion of possession as a crime (Dufton, 2017; Hillsman, 2017; Pacula et al., 2003). Therefore, some state decriminalization policies failed to meet even the Shafer Commission’s relatively modest standard for decriminalization. It is difficult to determine the consequences of these decriminalization policies, partly because they varied so widely.

State-Level Medical Cannabis (1978–1996)

In 1978, New Mexico adopted the first post-CSA law authorizing cannabis for specific therapeutic uses. Unlike decriminalization laws,

BOX 1-6

Decriminalization and Legalization

Decriminalization: Decriminalization describes policies that remove the criminal status and criminal penalties associated with simple cannabis possession (typically small amounts) and use.

Legalization: Legalization removes criminal and monetary penalties for the supply of cannabis for adult use purposes, in addition to removing these penalties for possession and use.

SOURCE: Pacula and Smart, 2017.

New Mexico’s Controlled Substances Therapeutic Research Act was intended to protect scientific research. The New Mexico model deferred to, rather than challenged, federal policy dominance by essentially creating a state-level version of the federal research program described above. More than 20 states followed New Mexico’s lead, although most never created research programs. In practice, the administrative burden of such programs limited their scope (Randall and O’Leary, 1999). In 1979, Illinois took an alternative approach, passing legislation that gave physicians with a controlled substances license the authority to prescribe cannabis for patients with debilitating conditions (Public Act 098-0122, 2014). A few other states8 adopted similar legislation between 1981 and 1996.

State medical cannabis programs tended to be bureaucratically complicated and costly to run (Randall and O’Leary, 1999). The 1985 FDA approval of dronabinol described above may have dampened enthusiasm for further medical cannabis programs. There was also a growing antidrug sentiment in the 1980s, along with momentum for increased prosecutorial action from the government (Chaiken and McDonald, 1988; Mold, 2021; Pascual, 2021, p. 1760). Taken together, these factors contributed to reducing state interest in medical cannabis programs.

State-Level Medical Cannabis, 1996 to the Present

In 1996, by ballot initiative, California voters passed Proposition 215, the Compassionate Use Act, allowing for medical cannabis use outside of FDA-approved indications and formulations (Uniform Controlled Substances Act, 2017). The ideas behind Proposition 215 were not new. However, the successful use of the ballot initiative broke a political logjam around medical cannabis. Initiative supporters enjoyed a substantial fund-raising advantage and deployed their resources in a politically savvy public campaign. By activating popular support for patients’ rights and creating an exemption from prosecution for patients and caregivers, Proposition 215 challenged federal policy dominance in ways no previous state policy had done. Clinical providers were allowed to recommend cannabis for any illness where it could provide relief, thus access was widely available.

Proposition 215 ushered in the “ballot initiative era” of medical cannabis policy. While the federal government remained explicitly opposed to such actions, voters expressed a different view. Of the states that have authorized medical cannabis use, most did so through a ballot initiative (Orenstein and Glantz, 2020). The resulting medical cannabis policies varied widely. Some were thinly veiled legal adult-use programs, while others had more complex requirements (Pacula and Smart, 2017; Pacula et al., 2015).

___________________

8 Connecticut, New Hampshire, Vermont, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Ballot initiatives on medical cannabis continued into the 2010s (Orenstein and Glantz, 2020). State legislatures gradually established more precise definitions of legal and medical use, with greater attention to state licensing and regulation of a legal supply chain. The Ogden Memorandum gave states considerable cover to build licensed cannabis retailer systems and to bring those who use medical cannabis and prescribers into a regulated system (Kleiner, 2014; Ogden, 2009). With these changes came a remarkable growth in the number of patients enrolled in state medical cannabis programs (Boehnke et al., 2022). Over time, state policies on medical cannabis, while still highly variable, have moved toward greater comprehensiveness and detail (Pacula and Smart, 2017).

State-Level Cannabis Legalization, 2012 to the Present

In 2012, Colorado and Washington state passed first-of-their-kind legislation to legalize cannabis possession for adults and authorize the creation of commercial sources of supply. Alaska and Oregon followed suit with ballot initiatives in 2014, after which the pace of change accelerated; as of April 2024, 24 states had legalized some form of adult-use commercial markets. While state laws vary, they share an emphasis on legal commerce, with attention to cultivation, processing, and retail and wholesale sales. This cannabis market has no historical precedent in the long history of cannabis in the United States. There are, however, similarities with the relegalization of alcohol following passage of the 21st Amendment. Despite differences between these drugs, valuable insights can be gleaned from the historical precedent of alcohol relegalization (Box 1-7).

Historical Patterns of Enforcement of Cannabis Law

The evolution of state and federal cannabis legislation is only one part of the historical story: these laws have been given meaning and real-world significance through their enforcement. Contemporary social equity provisions of cannabis legalization programs make clear the recognition that enforcement of cannabis law has historically had significant harmful impacts on individuals and communities. Furthermore, equity perspectives explicitly recognize that the harms of cannabis law enforcement have been borne disproportionately by communities of color and marginalized people, both socially and economically (Kilmer et al., 2021), which may contribute to health inequalities.

The policing of cannabis is more than a century old, dating back to the earliest state and local prohibitions on nonmedical sale and possession (Rathge, 2017). Arrests and convictions impact only a small portion of the population that has been involved in the illegal sale or possession of cannabis. Long ago, researchers demonstrated that actual patterns of enforcement behavior were subject to significant bias due to organizational priorities,

BOX 1-7

Lessons of Prohibition and Its Repeal

There is only one clear precedent in U.S. history for the commercialization of a formerly prohibited intoxicating substance on the scale of cannabis—the relegalization of alcohol following the repeal of national alcohol prohibition in 1933.

Policy heterogeneity: With both alcohol and cannabis, management of the process of commercialization has been left to the states (more formally, in the case of alcohol, with the 21st Amendment explicitly allowing states to decide whether and how alcohol might still be legally restricted). Both alcohol and cannabis legalization proceeded unevenly across states and yielded highly heterogeneous regulatory structures (Mississippi, for example, did not repeal its statewide alcohol prohibition until 1966). The critical difference, of course, is that state-level regulation of commercial alcohol markets took place with formal federal approval (in the form of a Constitutional amendment and congressional legislation). In contrast, state-level regulation of cannabis commercial markets is being undertaken in the context of continued federal prohibition. Therefore, one can reasonably argue that cannabis legalization remains vastly less stable than alcohol relegalization as a policy proposition. Moreover, supply structures, such as state monopolies, that were legally permissible for alcohol in 1933 have not been deemed a legal option for cannabis under the current federal policy.

Regulatory orientation: The relegalization of alcohol has been studied far less extensively than the experiment with alcohol prohibition itself. Nonetheless, what is known is that commercial markets in alcohol were subject to complex and strict state-level regulatory regimes, many of which were explicitly designed to moderate overall alcohol consumption. For example, most states barred liquor advertising from depicting “subject matter nor illustrations inducing minors or immature persons to drink” (Harrison and Laine, 1936, p. 70). In addition, a number of states adopted full or partial state alcohol monopolies, a practice initially oriented toward promoting consumer health and safety (in addition to state revenue). Consequently, most reliable estimates show that per capita alcohol consumption in the United States did not return to preprohibition levels until around 1970—roughly four decades after repeal. The regulatory conservativism toward alcohol has since been substantially loosened through both legislative and judicial action, and it appears clear

that commercial cannabis markets are being introduced in a legal and policy environment far less favorable to strict regulatory control.

Legalization and market consolidation: The relegalization of alcohol also yielded a remarkable consolidation of the industry, compared not only with the prohibition-era illicit market but also with the preprohibition industry. More than 1,500 preprohibition breweries were replaced by fewer than half that number in the immediate aftermath of repeal. That number eventually dwindled to just 100 by 1980 (with the five largest brewers controlling three-quarters of the market). Production of distilled liquor consolidated even more rapidly, with four corporations controlling four-fifths of the market by the end of the 1930s. Market consolidation reflected broad trends in American industry, to be sure, but a complex regulatory environment tended to further privilege producers that could compete at scale. Consolidation has been persistent, despite periodic efforts to restrain it; a 2022 Treasury Department report laments the continued inability of small alcohol producers to compete successfully (USDT, 2022). To date, the prohibition of interstate commerce in cannabis (owing to ongoing federal prohibition) has limited similar market consolidation; a shift to federal legal status for cannabis would be almost certain to accelerate that process rapidly absent explicit limiting efforts by Congress.

Persistence of illicit markets: The relegalization of alcohol did not eliminate an illicit alcohol market. The strict regulatory orientation of most state governments, together with continuing pockets of “dry” counties, helped sustain illegal market alcohol production and distribution. One reliable 1936 estimate suggested that illicit production equaled about 50 percent of licit production. Not until the 1970s did levels of Treasury enforcement of illicit alcohol production finally decrease to insignificance (McGahan, 1991).

Social equity considerations: The end of alcohol prohibition took place in a sociocultural environment far less attentive to social equity than is the case for the contemporary cannabis policy landscape. Efforts to address the negative impact of the enforcement of alcohol prohibition appear to have included no consideration of the inherent social equity dimensions. However, some state governors did issue blanket pardons to alcohol offenders still in state prisons at the time of repeal.

SOURCES: Hall, 2010; McGahan, 1991; Mikos, 2021; Pennock and Kerr, 2005; Room, 2008, 2020; Stockwell et al., 2020; Title, 2022.

political pressure, cultural attitudes, and public opinion (DeFleur, 1975; Reiss, 1971; Skolnick, 1966).

Patterns of bias in cannabis law enforcement have evolved over time. Cannabis policing in the 1920s and 1930s was highly localized and episodic, reflecting patterns of generally low law enforcement interest, with occasional moments of higher priority. During this period, cannabis arrests appear to have constituted a small proportion of overall drug law enforcement activity. The policing of opiates and cocaine had the highest priority, and cannabis arrests were often incidental to enforcement activity directed at these substances. Moreover, racial disproportion in these early years is not particularly apparent (Campos, 2018; Rathge, 2018).

During the 1940s and 1950s, while cannabis remained a secondary concern for law enforcement, racial disproportion in drug enforcement took on far more significance (Frydl, 2013). Many states classed cannabis as a “narcotic,” and simple possession could be a felony offense. Mandatory minimum drug sentencing laws, adopted in the 1950s by the federal government and many individual states, generally included cannabis (Frydl, 2013). Consequently, while overall levels of cannabis arrests remained low, legal sanctions increased, and racial disproportion emerged as a significant problem.

The first significant prioritization of cannabis law enforcement emerged with the general rise of cannabis use among college- and high school–age populations in the 1960s. Public concern over youth consumption led law enforcement to take a specific interest in cannabis, and the result was a substantial increase in arrests and convictions in that decade. California led the way, with a startling 20-fold increase in the number of cannabis arrests from 1962 to 1972, 95 percent of which were for felony charges and most for possession (Lassiter, 2023; Polson, 2021). In Chicago, officers reported pressure from their superiors to focus arrest activities on white youth and marijuana (DeFleur, 1975). As enforcement priorities shifted toward cannabis, the proportion of drug arrests involving cannabis increased—accounting for more than half of all drug arrests by 1967 (DOJ, 1968; Dufton, 2017; Lassiter, 2023).

This surge of cannabis enforcement activity, with its focus on younger White people from suburban areas, is largely forgotten today but yielded substantial numbers of felony arrests and convictions for simple possession. Drug enforcement was overwhelmingly biased toward racial minorities in this period, but cannabis enforcement represented an interesting exception. Cannabis arrests were a mechanism for targeting “hippie” groups and political activists, and school grounds and college campuses were a convenient enforcement target in the cultural battle over the drug (Dufton, 2017; Lassiter, 2023; Sanders, 1975; Smith, 1969).

The same social trends that encouraged nascent decriminalization efforts in the 1970s also led several states to reclassify cannabis in their criminal statutes, separating it from the general category of “narcotics” and reducing formerly draconian penalties for cannabis possession (Dufton, 2017; Lassiter, 2023). Changes to California law, for example, now allowed

district attorneys to opt into a misdemeanor charge for cannabis; in some jurisdictions, misdemeanor charges became the norm for individuals with no prior convictions or with small amounts in possession. Concerns that cannabis law enforcement could alienate a whole generation of Americans (Hills, 1970), with a particular focus on shielding middle-class White youth from the criminal justice system, gradually led not only to a reduction in criminal penalties but also to a pause in the growth of cannabis arrests nationally (Lassiter, 2023). Arrests peaked in 1973 at 200 per 100,000 residents and stayed roughly level until the mid-1980s, then actually fell through the early 1990s, as did the relative share of cannabis arrests in total drug arrest activity (Beckett and Herbert, 2008).

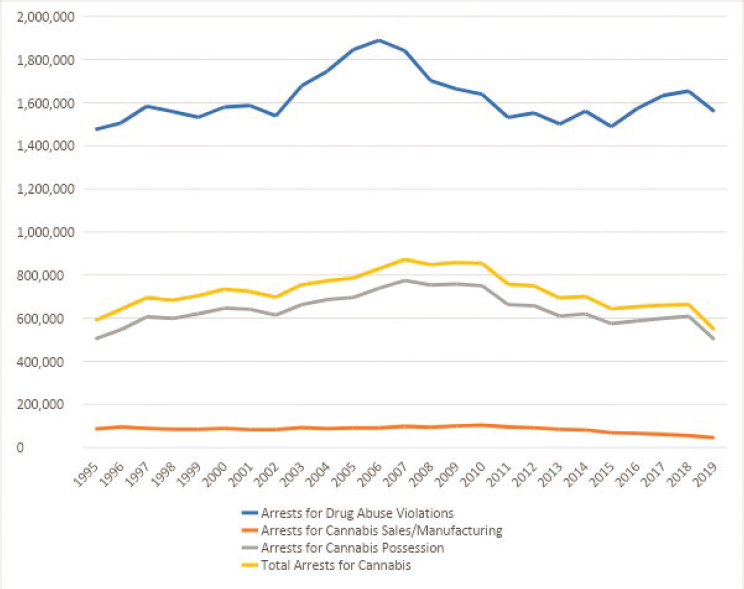

The next historical chapter of cannabis law enforcement emerged in the 1990s, marked by historically unprecedented levels of arrests. Data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Report show that cannabis arrests began rising in 1992 and by 1994 had surpassed previous 1970s-era peaks. This pattern of increase in enforcement activity continued through 2007. A few features of the 1992–2007 enforcement era stand out. First, cannabis possession offenses were the main driver of increased arrest totals; relegated to a lower priority in the past, strict enforcement of possession laws emerged as standard enforcement practice. In New York City, this change in priority sent cannabis possession arrests soaring, from a mere 774 in 1991 to more than 50,000 in the year 2000 (Geller and Fagan, 2010). Cannabis arrests once again rose to more than half of all drug arrests nationally (Golub et al., 2007; King and Mauer, 2006) (Figure 1-10).

Second, the 1992–2007 enforcement period featured significant racial disproportion, as numerous contemporary studies confirmed (Beckett et al., 2005, 2006; Cole, 1999; Tonry, 2011)—the highest levels of racial disproportion in the history of U.S. cannabis law enforcement. Racial disproportion entered every phase of the process, including initial stop, arrest, pretrial detention, charge, and final disposition (Geller and Fagan, 2010; Golub et al., 2007). Whether this disproportion is understood as a reflection of drug markets or enforcement tactics (Coker, 2002; Tonry, 1995) or of explicit racial bias (Alexander, 2010; Beckett et al., 2005, 2006), or as a broader consequence of institutional racism (Cole, 1999; Lynch and Campbell, 2011), it remains true that because of these enforcement patterns, the impact of cannabis enforcement was not experienced evenly.9

___________________