Cannabis Policy Impacts Public Health and Health Equity (2024)

Chapter: 4 Applying the Core Public Health Functions to Cannabis Policy

4

Applying the Core Public Health Functions to Cannabis Policy

Changes in cannabis policy impact public health. The core public health functions—assessment, policy development, and assurance—serve as a framework for leveraging ten essential public health services that can be used to promote public health for everyone (IOM, 1988). The essential services, introduced in 1988, further developed in 1994, and updated in 2020, are designed to promote equitable policies and address community structural barriers that may have led to health inequities (Castrucci, 2021).

The ten essential public health services are theoretical concepts and practical actions that fit within the core public health functions (Figure 4-1). Public health policy makers, cannabis regulators, and public health authorities have crucial roles in implementing these functions. Assessment involves surveillance, population health monitoring, and research to investigate root causes. Policy development includes communication, community mobilization, partnership building, public health policy and advocacy, and public health law and regulation. Assurance involves maintaining a competent workforce, robust infrastructure, continuous improvement, and equitable access to essential services for a healthy population (Castrucci, 2021).

The committee’s public health approach to cannabis policy, as outlined in Chapter 1, is not just a theoretical framework but is firmly rooted in the core public health functions and essential public health services (as detailed in Box 4-1, repeated here from Chapter 1). In this context, the core public health functions apply to cannabis policy directly, demonstrating their practical relevance and importance.

SOURCE: CDC, 2020. Materials developed by CDC. Reference to specific commercial products, manufacturers, companies, or trademarks does not constitute its endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Government, Department of Health and Human Services, or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ASSESSMENT

The core function of public health assessment necessitates a robust and adaptable surveillance system to monitor the public health effects of cannabis legalization. Assessment is crucial for understanding the potential effects of cannabis on the population and informing evidence-based policies. It triggers the need for additional investigation and can serve as a basis for evaluating changes in programs and policies.

State of Practice: Surveillance or Assessment and Monitoring of Population Health

Public health surveillance or assessment and monitoring of population health is the systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data (German et al., 2001). Public health surveillance is used to plan, implement, and evaluate public health (Teutsch, 2010). Surveillance is sometimes confused with and misunderstood as solely related to data

BOX 4-1

Public Health Approach to Cannabis Policy

Assessment

- Conduct surveillance of or assess and monitor the health impacts of cannabis.

- Investigate the causes of any identified harms from cannabis use.

Policy Development

- Build and mobilize partnerships between cannabis regulators and public health authorities.

- Inform, educate, and empower communities to develop cannabis-related public health campaigns.

- Develop cannabis policies centered on protecting public health that are not influenced by the regulated industry.

- Equitably enforce cannabis policies designed to ensure compliance.

Assurance

- Protect the public from the potential harms of cannabis (e.g., accidental ingestion or poisoning, crashes from impaired driving, secondhand smoke, and environmental impacts).

- Protect those who use cannabis from potential harm and ensure access to treatment.

- Build and support a diverse and skilled cannabis public health workforce.

- Improve and innovate cannabis public health functions through ongoing evaluation, research, and continuous quality improvement.

- Build and maintain a strong organizational infrastructure for cannabis and public health.

SOURCE: Adapted from Ghosh et al., 2016.

collection and public health research, but it is more complex. Surveillance is an ongoing system that aims to inform the decisions or actions of a public health authority (Otto et al., 2014). Surveillance should start with a plan. Crafting a surveillance plan requires careful consideration of the system’s goals, essentially answering the question, “What do you want to know?” Those goals in public health surveillance include understanding the incidence or prevalence of a specific behavior, disease, or health outcome; establishing public health priorities; conducting program evaluation; and allocating resources (Teutsch, 2010).

The surveillance system includes the surveillance plan; data collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination; a link to action; and evaluation (Figure 4-2) (CDC, 2018). Data collection can leverage existing data, such as surveys and administrative data. Data analysis plans are an important part of a surveillance plan; essential analytic elements need to be calculated often to ensure that the system is working and work best when they are automated. Data dissemination involves presenting analysis results so that decision makers and those who use cannabis can understand their significance. The findings from surveillance can guide actions such as treatment, prevention, policy development, and outbreak control at the local, regional, and national levels. Regular evaluation is undertaken to ensure that the system continues to serve the purposes for which it was designed and adapts to new needs.

There are many types of public health surveillance systems. The details of how a surveillance system operates depend on the specific questions to be answered, the available data infrastructure, the available budget, and the precision needed in the ultimate results (CDC, 2018; German et al., 2001; Teutsch, 2010).

Status of Surveillance or Assessment and Monitoring of Population Health

Cannabis surveillance in the United States is conducted by individual state governments; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); and other state, federal, and territorial agencies.

Cannabis Surveillance by the State Governments

In 2015, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), a nonprofit U.S. organization that focuses on public health issues through epidemiology, formed a cannabis subcommittee. The subcommittee was designed to provide a platform for state public health agencies and collaborators to share knowledge and resources, thereby fostering a national approach to systematically monitoring, characterizing, and mitigating the public health consequences of cannabis use (CSTE, n.d.). The subcommittee authored a position statement that identified critical gaps in surveillance of the public health impacts of cannabis. These gaps included a lack of funding, standard methods for or coordination of data collection, uniform guidance for data analysis and reporting, and research on cannabis-related health outcomes (CSTE, 2016).

In 2018, CSTE conducted an environmental scan of public health surveillance in the first eight legalizing states: Colorado, Washington, Alaska, Oregon, California, Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada. The survey found that six of the eight states had a legislative requirement for surveillance, but two of those six provided no funding to support it. The CSTE scan also found some gaps in the components of a surveillance system (Binkin et al., 2018). Prelegalization planning for dedicated marijuana surveillance systems was limited. Most states relied on existing resources. Further research was needed to fill gaps in knowledge about the health effects of cannabis use and the data and metrics needed for surveillance. Only six states had published reports on cannabis. Several states reported that data were being actively used to shape and modify state or local policies and inform program planning.

In 2021, the CDC and the American Public Health Association convened a learning collaborative of cannabis experts and stakeholders to discuss public health surveillance of cannabis. The collaborative identified successful partnerships among states; open communication; publicly available data that can be used to generate reports; and dashboards that allow for data sharing and coordinated, comprehensive analyses (APHA, 2021).

The collaborative also identified several challenges in cannabis surveillance (APHA, 2021). Staffing limitations, including vacancies and unfamiliarity with data systems, hamper analysis capabilities. Confidentiality concerns and the need to navigate consumer protections create barriers to data collection. Access to necessary agency data is often restricted or delayed, and establishing data-sharing agreements has proven difficult. Incomplete data, including underreporting and missing entries, further complicates the analysis. Statutory limitations and budget constraints restrict data use and impede research efforts (APHA, 2021).

Furthermore, the collaborative found that limited policy evaluation hinders understanding of the effectiveness of policies and limits informed adjustments. Fragmented coordination across agencies and inconsistencies among states and major cities create additional obstacles (APHA, 2021).

To determine whether the gaps identified in surveillance systems in 2018 and 2021 remain, the committee reviewed surveillance plans on state public health websites for a selected group of states—California, Colorado, Connecticut—using the province of Manitoba in Canada as a comparison (Bilandzic and Bozat-Emre, 2020; CCSS, 2021; CDPHE, 2022; King et al., 2022). It noted the processes for each surveillance system component (Table 4-1). Apart from data analysis and interpretation, it appeared that the cannabis surveillance systems within the states did contain necessary components of a surveillance system.

TABLE 4-1 Surveillance System Components in Select States and Manitoba, CA

| Surveillance system component | California | Colorado | Connecticut | Manitoba |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveillance plan | Established with clear objectives | Established with clear objectives | Established with clear objectives | Established with clear objectives |

| Data collection | Surveys (CA Healthy Kids, BRFSS, NSDUH etc.), administrative data (hospital encounters), law enforcement data, mortality data | Poison control center data, surveys (BRFSS, YRBSS, PRAMS, NSDUH), regulatory data (seed-to-sale), health care administrative data, traffic data, mortality data | Surveys (BRFSS, YRBSS, PRAMS, NSDUH), regulatory data (seed-to-sale), health care administrative data, traffic data, mortality data | Surveys (existing), product recall data, poison control data, hospital discharge data, drug analysis data, crime data |

| Data analysis & interpretation | Not described | Not described | Not described | |

| Data dissemination | Reports published | Data analysis is presented on a rolling dashboard Presented to government bodies every 2 years | Not described | Published reports and infographics |

| Link to action | Informs policy changes and program development | Informs policy changes and program development | Informs policy changes and program development | Informs policy changes and program development |

NOTES: BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; NSDUH = National Survey of Drug Use and Health; PRAMS = Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System; YRBSS = Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System.

SOURCES: Bilandzic and Bozat-Emre, 2020; CCSS, 2021; CDPHE, 2022; King et al., 2022.

Cannabis Surveillance in the Federal Government

The CDC and FDA perform complementary roles in cannabis surveillance in the United States. At the CDC, the Division of Overdose Prevention in the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control has issued a 5-year plan (2020–2025) with the overall goal of monitoring and addressing the use of and exposure to cannabis and its associated health and social effects (CDC, 2020). In pursuit of this goal, the CDC has developed a cannabis surveillance strategy by articulating priority outcomes and populations to guide the state, tribal, local, and territorial governments in building capacity.

The strategic pillars of the CDC’s plan are to monitor trends; advance research; build state, tribal, local, and territorial capacity; support health systems and health care providers; partner with public safety, schools, and community coalitions; and improve public knowledge and awareness. Priority outcomes include initiation and use, substance use disorder, poisonings, occupational injury, motor vehicle crash injury, employment, cardiopulmonary conditions, environmental exposure, developmental outcomes, and prenatal and pregnancy complications. Specific populations prioritized for monitoring include adolescents and young adults, older adults, infants and young children, pregnant or postpartum persons, workers, minority groups, and people in poor health or with chronic conditions (CDC, 2020). Some examples of actions the CDC is taking to implement its cannabis strategy are listed in Figure 4-3. The plan does not include data analysis, interpretation, dissemination, and links to action.

The FDA (2024b) has a limited role in monitoring cannabis-derived products through passive pharmacovigilance systems. Although not always considered in the context of public health surveillance, pharmacovigilance systems—also known as adverse drug reaction monitoring, drug safety surveillance, side effect monitoring, unsolicited reporting, and postmarketing surveillance—exist to identify problems related to medicines, vaccines, and other medical products, as well as nonmedical products, such as dietary supplements.

Pharmacovigilance comprises the science and activities of detecting, assessing, understanding, and preventing adverse effects or any other medicine- or vaccine-related problem (Nour and Plourde, 2019). In the 1960s, in response to the thalidomide disaster, national pharmacovigilance systems were established to enable earlier identification of severe adverse drug events (Fornasier et al., 2018). The central feature of historical and current pharmacovigilance systems is databases of spontaneously reported adverse events suspected to have been caused by a medical product, such as a drug, biological product, or medical device (Fornasier et al., 2018). These anecdotal reports are submitted by health care professionals, consumers, and other sources directly to national regulatory agencies or medical product manufacturers, which submit the reports to regulators. Because of the large volume of reports received, manufacturers and regulators identify signals of

SOURCE: CDC, 2021. Materials developed by CDC. Reference to specific commercial products, manufacturers, companies, or trademarks does not constitute its endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Government, Department of Health and Human Services, or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

potential product–outcome relationships by calculating disproportionality metrics of product–outcome pairs that are observed more frequently among the anecdotal reports than would be expected by chance (Fornasier et al., 2018; Nour and Plourde, 2019).

While spontaneous reporting systems are still widely used for pharmacovigilance, their use has been supplemented by screening studies of health care data aimed at identifying potential novel associations between medical products and adverse outcomes in recent years. Signals of potential medical product–outcome associations identified through spontaneous reporting systems or screening analyses of health care data are often strengthened and confirmed (or weakened and refuted) through subsequent epidemiologic studies using health care data or systematic investigation (Bate et al., 2019).

The FDA has approved a few cannabinoid drugs—Cesamet™ (nabilone), Marinol® (dronabinol), and Epidiolex. These drugs are monitored for safety

in existing pharmacovigilance systems. While cannabis and cannabis-derived products are not currently FDA-approved medications, the agency leverages two electronic databases—the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition’s Adverse Event Reporting System (CAERS)—to monitor their safety profile (FDA, 2023, 2024a).

FAERS and CAERS are passive surveillance systems that rely on voluntary reporting of adverse events and product quality concerns. These reports can originate from diverse stakeholders, including health care professionals, consumers, and law enforcement officials. The FDA facilitates reporting through established channels such as the MedWatch Program, the Safety Reporting Portal, and the Consumer Complaints process. This broad accessibility allows for the collection of data from a wide range of populations, potentially uncovering safety signals that might otherwise be missed (FDA, 2023, 2024a).

The FDA could use FAERS and CAERS data regarding cannabis products to inform regulatory decisions and guide public health education. If concerning trends were identified within the data, the FDA could take appropriate regulatory actions, such as product recalls or safety warnings, to safeguard public health. The FDA could also develop targeted public health communications highlighting specific safety concerns associated with cannabis use. For example, the FDA has warned consumers about children’s accidental ingestion of cannabis edibles that were mistaken for commonly consumed foods such as breakfast cereal, candy, and cookies (FDA, 2022).

The anecdotal nature of FAERS and CAERS data introduces inherent limitations. Passive systems such as these substantially underreport events. Reported events may not be entirely representative of the entire cannabis-consuming population, and definitively establishing causality between a product and a reported event can be challenging. Another limitation is that passive reporting systems require that people know of their existence to capture adverse events. However, increasing public awareness of the reporting system can increase the reporting of cases, making it difficult to interpret whether an increase in cases indicates increasing problems (Thacker and Berkelman, 1988).

Research

Public health assessment includes research aimed at determining the root causes of any problems identified in the surveillance system or identifying new problems or issues that should be tracked in the system. Research and surveillance have many commodities and can use the same datasets. A critical difference between research and surveillance is that research is not

an ongoing system directed toward public health action. It may uncover previously unknown risk factors, shed light on structural factors influencing health, or evaluate the effectiveness of existing prevention strategies. Unlike surveillance, which prioritizes standardized and readily deploy-able methods, research can embrace a broader range of methodologies, including qualitative studies, in-depth analyses, and pilot interventions. While research findings might or might not be immediately actionable, this exploratory phase is vital in advancing public health knowledge. Validated research methods may improve surveillance systems, allowing for more comprehensive data collection and analysis in the future. CDC policies define “research” as a systematic investigation, including research development, testing, and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge (45 CFR § 46.102[d]). This definition underscores the emphasis on knowledge creation and discovery that distinguishes research from the more action-oriented nature of surveillance.

California, Colorado, and Connecticut are all conducting or supporting research to investigate public health challenges related to cannabis use. California funds cannabis research, including that focused on public health impacts, environmental effects, economic factors, and social justice issues. Studies are examining everything from the effects of cannabis on brain development to the impact of marketing on youth use. The research is designed to inform policy and improve understanding of the complex issues surrounding cannabis legalization (DCC, 2024). In Colorado, the Cannabis Research and Policy Project, a collaboration between the Colorado School of Public Health and the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, is leading this research. It conducts systematic reviews of existing research, recommends evidence-based policy changes, and develops public education campaigns (Colorado School of Public Health, 2024). In Connecticut, cannabis research is focused primarily on therapeutic uses (King et al., 2022).

Cannabis Assessment: Findings

The committee found that among the states, cannabis surveillance does not include all the essential components of a public health surveillance system: a surveillance plan; data collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination; a link to action; and regular evaluation. While most states are implementing some or most components of such a system, most state surveillance systems are underfunded, limiting the frequency of analyses and data dissemination, which in turn limits the link to action. Only Colorado has a complete system with regular analyses, research, and plans for reporting to policy makers, an important activity that may lead to public health action.

POLICY DEVELOPMENT

Policy encompasses laws, regulations, policy procedures, administrative actions, incentives, and voluntary practices of governments and other institutions. Not all public policies are legally enforceable; some are guidance developed by administrative agencies with the expectation that they will be adhered to (Pollack Porter et al., 2018). Policy development is critical for primary prevention of potential harms from cannabis use. All major public health achievements involve policy development (CDC, 1999, 2011). The development of public health policy requires strong partnerships, policy implementation, compliance, and enforcement (Castrucci, 2021). Effective cannabis policy hinges on collaboration among regulators, public health experts, and empowered communities to prioritize public health through informed regulations and equitable enforcement (Pollack Porter et al., 2018).

State of Practice: Public Health Policy Development

The CDC’s (2022) policy development process consists of problem identification, policy analysis, strategy and policy development, and policy enactment. It centers on stakeholder engagement, education, and evaluation. Problem identification requires clarifying and framing a problem or issue with respect to the effect on public health. Public health practitioners and policy developers use data to define the issue and its characteristics (frequency, scope, budgetary impacts) and any gaps in the data. Policy analysis involves researching potential solutions; evaluating their health impact, cost-effectiveness, and feasibility; and ultimately selecting the most effective option. The process of strategy and policy development translates the selected solution into an actionable plan, outlining implementation steps and stakeholder engagement and potentially drafting the policy. “Policy enactment” refers to following internal or external procedures for getting policy enacted or passed. Policy implementation bridges the gap between policy and practice by translating policy into actionable steps, monitoring its adoption, and ensuring its ongoing effectiveness. Stakeholder engagement and evaluation are continuous threads throughout the policy process, ensuring informed decision making and measuring the policy’s effectiveness (CDC, 2022).

The CDC also advocates for a collaborative approach to public policy development, termed “Health in All Policies,” because policies in such areas as education, zoning, labor, and working conditions—often formulated by nonhealth professionals—impact public health. Health in All Policies approaches are also intended to improve health equity but need to reflect recognition of political opportunities, understanding

that institutionalization can be helpful but should not delay acting, and awareness that promoting equity through such policies requires dedicated resources (Hall and Jacobson, 2018).

Civic Engagement and Belonging

Systems of civic engagement and belonging are critical in public health policy development and can serve as an avenue for combating health inequities. Cultivating belonging demonstrates an understanding of the value of personal and community culture and knowledge systems and an awareness that valuing these differences is essential to achieving equity. Accordingly, policy developers must work with community members to strengthen communities’ established and self-determined assets, means of connection, and values. The Federal Plan for Equitable Long-Term Recovery and Resilience (ELTRR) articulates a whole-of-government approach established by more than 35 U.S. agencies, including the departments of Health and Human Services, Education, Transportation, and Justice. The goal is to improve health and well-being for everyone in the country, with a focus on achieving equity. The ELTRR identifies seven key factors necessary for health and well-being and places “belonging and civic muscle” as the foundation of the approach, defined by the ability to have healthy, fulfilling relationships and strong social supports, along with the ability to participate in civic life. Communities with strong civic muscle can design their pathways to resilience, gather assets so they can respond effectively and equitably in a crisis, persistently expand vital conditions while alleviating urgent needs, and use their power to ensure mutual accountability (ODPHP, 2022). The working group that created the plan formulated recommendations emphasizing the importance of involving community members in policy making (NASEM, 2023a).

Prevention of Industry Influence

Industry may disproportionately influence public health policies. It can influence specific policies in many ways, such as by participating in rulemaking or assembling scientific studies or reviews that support its desired policy decisions. Industry participation in rulemaking is often called regulatory or agency capture, denoting situations in which the regulated industry strongly influences the agency or people responsible for creating or implementing the regulations. Selectively supporting and assembling science to confuse decision makers and the public is effective because if the decision makers and the public believe the science is unclear, public support for action is undermined. Some of the many examples of industry influence on policy include the tobacco industry’s downplaying the harms of tobacco use and

the health impact of secondhand smoking, the fossil fuel industry’s denying and devaluing of its impacts on climate change, and chemical companies’ efforts to deflect concerns about the safety of chemicals (Michaels, 2020; Oreskes and Conway, 2011). Industry-developed information campaigns endanger public health by delaying regulations on harmful products and pollution of the air and water. They also erode trust in science by making it difficult to distinguish genuine uncertainty from manufactured doubt (NASEM, 2023b).

State, Tribal, Territorial, and Local Public Health Policy Development

State, tribal, territorial, and local public health officials have a substantial role in public health policy development. The 10th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which reserves unspecified powers to the states, creates a decentralized environment for public health policy development. As a result, a significant portion of public health policy decisions is made at the state, territorial, tribal, and local levels. The CDC and other agencies guide states on many issues, and several other collaboratives provide resources for policy development. Examples of these organizations are the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO), the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), the American Public Health Association (APHA), the National Conference of State Legislatures, and the National Governors Association.

Another resource available to guide public health policy decisions at any level is the Community Guide developed by the Community Preventive Services Task Force (2023), the product of an independent panel that issues evidence-based recommendations and findings on public health interventions designed to improve health and safety. The Community Guide includes recommendations for the primary prevention of potential harms on many topics, including excessive alcohol use, mental health, alcohol-impaired driving, tobacco use, and substance use (CPSTF, 2023).

Compliance and Enforcement

Compliance refers to the “extent to which an individual, organization, group or population acts in accordance with a specific public policy” (APIS, n.d., para. 4). It requires determining who is responsible for enforcement and the processes used to ensure that regulations are followed. The responsible agencies need the requisite skills and experience to enforce policies fairly and successfully. Another important consideration is how regulatory compliance will be determined, such as specifying how much industry self-regulation is allowed or whether compliance is assured through inspections or more passive reporting mechanisms (APIS, n.d.). While protecting against

regulatory capture when developing policies is vital, it is also essential to consider that a regulated industry may try to influence compliance and enforcement strategies. Enforcement does not mean just law enforcement or policing but encompasses the “sum total of actions taken by public entities to increase compliance with specific public policies” (APIS, n.d., para. 4). Enforcement relies on many tools beyond policing and criminal penalties, including inspections, compliance checks, fines, recall of products, and revocation of licenses. Ideally, policy enforcement creates a system that encourages compliance across the board, from licensed businesses to consumers, with penalties graduating in severity and consequences depending on the nature of the noncompliance (APIS, n.d.).

Tobacco provides an excellent example of the complexity of regulation and enforcement. The U.S. Department of Agriculture oversees cultivation standards for tobacco (7 USC 511, 511s), while the FDA regulates manufacturing, product testing, and labeling to ensure safety and limit youth appeal (PL-102-321; PL-116-94). The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives tackles illegal tobacco suppliers (PL-111-154 [2009]). State and local governments are crucial for enforcing minimum age for purchase and use and marketing regulations at retail locations. The FDA takes the lead with warnings and penalties for violations (21 CFR 1140). Smoke-free environments are regulated primarily by state and local authorities, with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) providing educational resources and the federal government enforcing a ban on smoking in its buildings (Executive Order 13058).

Compliance with alcohol policy is similarly ensured through federal, state, and local authorities. The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau oversees the production, import, distribution, labeling, and advertising of alcohol. It issues permits and enforces regulations to ensure product safety and prevent illicit sales. The Federal Alcohol Administration Act (27 USC, Chapter 8, §§ 201–212) mandates permits for producers, importers, and wholesalers, while the FDA regulates ingredient labeling. Advertising is mainly self-regulated by the alcohol industry, with federal agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission encouraging responsible practices to limit youth exposure (Mart, 2012).

Policies on alcohol retail sales and consumption are set by states and some local jurisdictions, and compliance is ensured through local enforcement. For example, each state has a licensing system for retailers, and some jurisdictions require training for servers or bartenders. States also determine where alcohol can be consumed publicly and enforce laws against underage drinking. Some federal highway funding can be withheld from states, most notably to ensure adherence to a blood alcohol (BAC) limit for driving of 0.08 percent (23 USC 163); one state (Utah) has a lower BAC limit (Utah HB155) to further reduce alcohol-related crashes.

Status of Cannabis Policy Development

State, tribal, territorial, and local public health officials can follow best practices for developing public health policies when creating policies for legalized cannabis. These practices include following the CDC’s policy development steps; using a Health in All Policies approach; empowering communities; promoting civic engagement and belonging; limiting industry influence; and encouraging collaboration among federal, state, tribal, and local governments in the development and implementation of cannabis policies. Chapter 2 provides a detailed summary of cannabis policies across the states; here, the committee describes some findings on the overall application of these best practices for policy development.

State cannabis policies vary widely, and a thorough evaluation of whether the development of those policies followed the best practices for public health policy development is difficult. A review of cannabis policies across the United States highlights the patchwork of state regulations around cannabis, including taxation rates, revenue allocation, product restrictions (e.g., forms, additives, flavors, concentration), packaging and labeling requirements, consumption locations, advertising limitations, and social equity programs aimed at fostering minority participation in the industry (Schauer, 2021).

States with legalized adult-use cannabis did not generally follow a Health in All Policies approach in developing their policies. At least initially, the policy development began with prioritizing market outcomes (such as enabling sales and consumption), which can be misaligned with public health goals (such as reducing dependence and preventing underage consumption) (Hall et al., 2019; Kilmer, 2019; Schauer, 2021). Consumer awareness about cannabis products and health and safety considerations has also not been prioritized (Schauer, 2021). For example, early adopters of legal cannabis for adult use, such as Colorado and Washington, relied on established agencies such as alcohol and beverage control or departments of revenue to oversee adult-use cannabis, which gave less control to public health authorities. Indeed, public health agencies, typically responsible for medical cannabis, are generally excluded from overseeing adult use. Over time, states have created stand-alone cannabis control commissions, evidence of the growing recognition of their complexities specific to cannabis regulation. Local jurisdictions regulate licensing, zoning, and business operations, but their authority thus far has varied (Schauer, 2021). Some states have enabled local authorities to apply taxes and numerous specific policies (e.g., California), whereas others have largely preempted local authority beyond a full ban on sales or the application of time–place–manner restrictions (e.g., Washington).

Civic Engagement and Belonging in Cannabis Policy

The extent to which cannabis policy development has occurred within a civic engagement and belonging system is unclear. All states followed required and discretionary methods for engaging with stakeholders when promulgating rules regarding cannabis policy, and there are examples of proposed rules around cannabis policy that were not adopted because of public input, such as the proposal in California to allow police officers to become cannabis business owners (Bowling and Glantz, 2019a). The lack of social equity considerations in the initial policy development process demonstrates that those with less civic muscle may not have participated. Even in states where cannabis legalization was motivated by social justice concerns, social equity was usually not considered in the initial policy development (Firth et al., 2019; Schauer, 2021). States did not initially institute the cannabis social equity programs that many in the public desired (Gerber, 2022; Schauer, 2021).

Industry Influence on Cannabis Policy

Industry influence on cannabis policy development has been difficult to limit. The cannabis industry had a seat at the table in the development of initial regulations in several states, including Colorado and California. And like tobacco and alcohol companies before them, the cannabis industry uses political donations and lobbying to influence regulations (Carlini et al., 2022; Subritzky et al., 2016). Large corporations such as those in the tobacco and alcohol industries are also investing in cannabis businesses (primarily in countries where cannabis is federally legal), suggesting confidence in the cannabis industry’s future profitability, and are leveraging public support for medical cannabis to push for broader legalization (Adams et al., 2021). The cannabis industry may downplay the risks and overstate the benefits of cannabis to influence policy. This is evident from the close ties among cannabis businesses, patient groups, and researchers, making it difficult to separate genuine medical cannabis research from industry promotion (Adams et al., 2021; Subritzky et al., 2016; Wagoner et al., 2021).

There are many examples of industry influencing rulemaking on cannabis policy (Carlini et al., 2022; Subritzky et al., 2016). The cannabis industry has also influenced the development of flavoring limits and environmental regulations. Several attempts to remove flavoring from cannabis products in California have failed despite successful efforts to do so for nicotine vaping and e-cigarette products. And while the Colorado Department of Agriculture proposed prohibiting the use of pesticides that require federal registration in legal cannabis cultivation, it changed the regulations following industry pushback (Carlini et al., 2022; Subritzky et al., 2016).

At least five states have attempted to place limits on the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration in cannabis products following legalization,

and all five have failed (Pacula et al., 2022). In Washington state, the cannabis industry attempted to impede four different bills (HB 2546, 2020; HB 1463, 2021; HB 1641, 2023; and HB 1642, 2023) that would have placed THC concentration limits on cannabis products, adopted concentration-based taxation, and instituted age-based concentration sales (Carlini et al., 2024). Three rhetorical messages were effective at defeating additional regulation of cannabis products: (1) arguing that such regulations would threaten economic benefits and public health and go against the will of the people, (2) discrediting the science that supported the regulation of cannabis products with high THC concentration or the individuals that were advocating for these policies, and (3) distracting from the bill’s focus using tangential topics that would derail the discussion (Carlini et al., 2024). Similarly, in Vermont, the industry has pushed back on limits of 30 percent THC in flower and 60 percent THC in solid extracts (Hawks, 2023; Levine, 2024).

Conflicts of interest have been observed among cannabis regulators. In Colorado, a cannabis regulator left a government job and immediately started working for a cannabis cultivator (Harmony & Green) to advise them on following the rules despite a state law requiring a 6-month waiting period after such a switch. In Washington state, a government official who approves cannabis business licenses rented out a large piece of land (25 acres) to someone who wanted to start a cannabis business. In Massachusetts, an employee responsible for issuing medical cannabis licenses applied for one of those licenses while still employed by the agency. In Ohio, six companies that lost their bids for cannabis business licenses sued the state, claiming that the reviewers who scored the applications did so unfairly and hired biased consultants with conflicts of interest. In Arkansas, a court order stopped the state from issuing licenses to grow cannabis because of a lawsuit alleging issues similar to those found in Ohio (Bowling and Glantz, 2019b).

Issues with conflicts of interest may be more commonly associated with medical than with adult-use cannabis programs. Surveys found that only 20 percent (6 out of 30) of the states that legalized medical cannabis had conflict-of-interest provisions in their medical cannabis codes, and the remaining 80 percent relied on general provisions relating to all areas of regulation. In contrast, 88 percent (seven out of eight) of the first states to legalize adult cannabis use included conflict-of-interest provisions directly in their cannabis codes or regulations (Bowling and Glantz, 2019b).

Guidance for Cannabis Policy Development

Neither the CDC nor the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) has crafted guidance for cannabis policy development. In fact, under 21 USC 1703, ONDCP is prohibited from using federal funds

to study anything related to the medical or nonmedical legalization of cannabis and other Schedule I drugs.1 However, other organizations, such as ASTHO, NACCHO, and APHA, provide resources for policy development (Jernigan et al., 2021). The Community Guide includes no recommendations for cannabis policy development, but the recommendations related to tobacco and alcohol can be applied (Ghosh et al., 2016). Chapter 2 describes how these public health levers have been implemented in various ways across the states with legal cannabis for adult use.

Compliance with and Enforcement of Cannabis Policy

Cannabis regulatory compliance can be burdensome to implement. Currently, each state with a legal cannabis market must bear the administrative burdens associated with establishing and maintaining systems to ensure compliance with state policies on cannabis cultivation, product development, packaging restrictions, marketing restrictions, sales, and youth access.

An audit of 700 California outlets during summer 2019 found that while nearly all retail outlets were compliant with age identification checks before any purchase, the vast majority (85.1 percent) did so after entry into the building, where child-appealing marketing and materials promoting the health benefits of cannabis were visible to anyone allowed in the waiting room. The audit found that violations of rules regarding free samples (21.6 percent), on-site consumption (16.1 percent), and materials promoting health benefits (38.9 percent) were all common (Shi and Pacula, 2021).

Another audit of the retail sales of 30 randomly selected cannabis retailers in each of five U.S. cities (Denver, Colorado; Seattle, Washington; Portland, Oregon; Las Vegas, Nevada; and Los Angeles, California) in summer 2022 likewise found that age verification rates were high (>90 percent) (Berg et al., 2023). Most retailers also complied with regulations on signage, such as restricted access for those under the legal age (87.3 percent), no on-site consumption (73.3 percent), and no distribution to people below the legal age (53.3 percent). Retailers were likely to post warnings regarding use during pregnancy or breastfeeding

___________________

1 The law states: “no Federal funds appropriated to the Office of National Drug Control Policy shall be expended for any study or contract relating to the legalization (for medical use or any other use) of a substance listed in schedule 1 of section 812 of this title and take such actions as necessary to oppose any attempt to legalize the use of a substance (in any form) that –

- is listed in schedule I of section 812 of this title; and

- has not been approved for medical purposes by the Food and Drug Administration” (21 USC 1703 § (b)12).

(72.0 percent), followed by health risks (38.0 percent), impacts on youth (18.7 percent), and driving under the influence (14.0 percent). However, there were other signs of noncompliance with policies, as 28.7 percent of these stores posted health claims, 20.7 percent posted signage appealing to youth, and 18.0 percent sold products with youth-oriented packaging (Berg et al., 2023).

Retail audit studies provide evidence of the states’ challenges in encouraging compliance and enforcement. A study conducted in summer 2017 sought to understand the extent to which retail employees at either medical or adult-use cannabis outlets would recommend cannabis to pregnant women (Dickson et al., 2018). Female researchers from the study team made calls to 400 retailers throughout Colorado, claiming to be 8 weeks pregnant and experiencing severe nausea and inquiring whether the person working at the retailer could recommend any products for them. The study found that most retailers (67 percent) recommended cannabis products for “morning sickness,” with medical stores doing so more frequently than adult-use-only stores (83.1 percent versus 60.4 percent). A more recent study that in 2022 conducted a mystery shoppers audit of 140 licensed cannabis stores in five cities with well-established state markets (Denver, Colorado; Portland, Oregon; Las Vegas, Nevada; Los Angeles, California; and Seattle, Washington) also found that it was common for retail employees to recommend cannabis for therapeutic uses (90 percent), regardless of whether state laws existed to prohibit the practice (Romm et al., 2023). While retailers endorsed cannabis primarily for common conditions such as anxiety, insomnia, and pain, endorsements for pregnancy-related nausea and warnings against use during pregnancy and driving varied by city (Romm et al., 2023).

Monitoring of online marketing is highly challenging for states. One study conducted in 2022 collected and analyzed data regarding retailer characteristics, age verification, and marketing strategies (e.g., product availability, health-related content, promotions, website imagery) among 195 cannabis retail websites in five U.S. cities (Denver, Colorado; Seattle, Washington; Portland, Oregon; Las Vegas, Nevada; and Los Angeles, California). The analysis reveals concerning trends, such as the prevalence of unsubstantiated health claims despite regulations prohibiting them in some states (59 percent). Discounts, samples, or promotions were on 90.8 percent of websites, and 63.6 percent had subscription/membership programs. Subpopulations represented in website content included 27.2 percent teens/young adults, 26.2 percent veterans, 7.2 percent sexual/gender minorities, and 5.6 percent racial/ethnic minorities. Imagery also targeted young people (e.g., 29.7 percent party/cool/popularity; 18.5 percent celebrity/influencer endorsement) (Duan et al., 2023).

Cannabis Policy Development: Findings

Comparing cannabis policy development against best practices for policy development yields several findings. First, early policy efforts were more favorable to market outcomes such as increased sales, tax revenue, and removal of an illicit market than to public health outcomes such as reducing dependence and underage use. Nor was consumer awareness of health risks prioritized. Since those early efforts, regulatory structures have been evolving, and dedicated cannabis control commissions have been emerging. Although public health agencies are often excluded from overseeing adult-use cannabis, they are increasingly included in policy development. Public engagement has been mixed: stakeholder involvement has occurred, but a lack of social equity considerations in initial policy development suggests limited participation from marginalized groups. The legal cannabis industry exerts influence through lobbying and donations, potentially downplaying risks and overstating benefits. Furthermore, only a minority of medical cannabis states have specific conflict-of-interest provisions.

ASSURANCE

Public health assurance refers to how the public health system consistently safeguards the health and well-being of the entire population. It is a comprehensive approach to guaranteeing a robust public health system. It encompasses five public health services: ensuring that everyone can access necessary health care, fostering a diverse and qualified workforce, providing health education and primary prevention programs, conducting continuous evaluation and improvement, and establishing a solid public health infrastructure. Cannabis policy assurance exemplifies these principles in action.

State of Practice: Public Health Assurance

Best practices of public health assurance extend beyond traditional public health interventions such as vaccination campaigns. Given the complex nature of public health and the government’s responsibility to protect all citizens, assurance often necessitates collaboration with various partners outside the public health sector (Knight, 2014; Perry, 2024). These partners may include private companies, community organizations, and nonprofit groups (Braveman and Gottlieb, 2014; Perry, 2024).

Strengthening assurance requires well-equipped state and local health departments with the resources to deliver essential public health services that are accessible and culturally sensitive, which includes considering factors such factors as language, social background, and ethnicity (NASEM, 2017; Perry, 2024). In this context, assurance encompasses a broader range

of services and actions than just health care. Assurance processes address factors that create barriers to public health interventions or directly improve health outcomes for the population. Examples include ensuring fair housing policies; protecting voting rights; and promoting equitable access to education, particularly within the public health workforce itself (Churchwell et al., 2020; Jain et al., 2022; NASEM, 2017; Perry, 2024).

Ensuring occupational health and safety is also important in cannabis policy. Certain safety and security professions in the United States require employee drug testing, with the goal of deterring drug use among these critical roles, identifying potentially impaired workers, and minimizing health and safety risks associated with compromised performance. The U.S. Department of Transportation requires testing for employees in transportation sectors such as aviation and trucking. The Department of Defense enforces similar regulations for contractors accessing classified information. And the Nuclear Regulatory Commission mandates “fitness-for-duty” programs at certain nuclear facilities, which include drug testing to ensure that workers’ impairment from the use of cannabis does not compromise safety (SAMHSA, 2023).

Ensuring occupational health for those who work in the cannabis industry requires establishing occupational health and safety standards and procedures that ensure compliance with and enforcement of those standards. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration is responsible for setting occupational standards in the United States. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) focuses on research, recommendations, and education, offering free health hazard evaluations, investigating potential health risks in workplaces, promoting research, and safeguarding worker well-being. The Health Hazard Evaluation program helps employees, unions, and employers learn whether health hazards exist at their workplace and recommends ways to reduce hazards and prevent work-related illness (Lybrand and Coughanour, 2021).

Status of Cannabis Policy Assurance

Public health assurance completes the cycle of ten essential public health services. Assurance leverages existing organizational structures to safeguard public health in the context of cannabis legalization, seeking to advance four key priorities. First, assurance prioritizes harm reduction by minimizing the potential risks associated with cannabis production and use. At the same time, it ensures access to appropriate treatment for individuals who may require interventions. Second, assurance recognizes the vital role of a skilled and diverse public health workforce equipped specifically to address the complexities of cannabis legalization. Third, it fosters a culture of continuous improvement in cannabis public health functions through ongoing evaluation, research, and a commitment

to evidence-based practice. Finally, assurance emphasizes the need for a robust organizational infrastructure that effectively supports cannabis-specific and broader public health initiatives.

Protecting Those Who Use Cannabis from Potential Harm

States with legal adult use of cannabis are using several strategies to mitigate the risks of consuming cannabis products and limiting certain types of products that might be deemed unsafe, limiting serving sizes, banning certain harmful ingredients, and testing products to ensure that they do not contain harmful contaminants (Schauer, 2021).

A review of cannabis policies in 2021 found that all adult-use states allow a broad array of products (e.g., flower, vape, concentrates). Three states (California, Michigan, and Washington) limit edibles to shelf-stable forms to minimize food safety risks. Most states prohibit adulterated prepackaged products with added THC. Colorado implements a unique level of oversight by requiring specific audits for products designed to mimic existing noncannabis medications (e.g., inhalers, suppositories) (Schauer, 2021).

As of 2021, all adult-use cannabis states had implemented THC serving-size limits for edibles and other consumable products (Schauer, 2021). While these limits were developed in response to high-profile incidents of edible overconsumption (Barrus et al., 2016; Nicks, 2014; Schauer, 2021), they differ among states. Most states allow a 10-mg THC serving, generally capped at 100 mg per package. Washington requires individual wrapping for edible and infused product servings within a package. However, highly concentrated THC products exceeding these serving sizes remain widely available. Vermont planned to implement limits on THC concentration in flower (30 percent) and oils (60 percent) and to restrict oils and concentrates to vape pen cartridges (Schauer, 2021).

The 2021 review of cannabis policy found that states also have limits on ingredients that can be contained in cannabis products. Many states have banned or are testing for vitamin E acetate because of the 2019 outbreak of e-cigarette or vaping product–associated lung injury (EVALI) (Schauer, 2021). Colorado has banned medium-chain triglycerides oil and polyethylene glycol oil entirely. Similarly, Oregon has prohibited squalane, propylene glycol, and all triglycerides, substances that lack established safety data for aerosols. Nevada limits the added terpene content in vape oils to 10 percent, which aligns with the upper range of naturally occurring terpenes in the cannabis plant. Vermont takes the strictest approach, permitting only natural cannabis-derived flavors in its upcoming adult-use market. States that regulate cannabis and cannabis-derived products do not have uniform testing procedures or regulatory approaches to ensure product integrity, safety, and labeling (Schauer, 2021).

Product testing is another crucial strategy for mitigating the risks of consuming cannabis. Federal Schedule I classification restricts the involvement of state-based laboratories in cannabis testing. Establishing state reference laboratories, which could validate third-party results, remains challenging for most states (Schauer, 2021). As a result, testing standards vary widely across the states with respect to the timing of testing within the production process (pre- or postproduction); the sampling and process validation protocols; and the testing methods, thresholds, and protocols by contaminant type and product category (Schauer, 2021). The adult-use states mandate cannabis product testing by licensed in-state third-party laboratories accredited to international standards (ISO 17025) (Schauer, 2021). All states test for cannabinoid concentration and residual solvents. There have been cases of “lab shopping,” whereby product manufacturers search for laboratories that provide favorable THC concentration results (Jikomes, 2022; Roberts, 2023; Schauer, 2021).

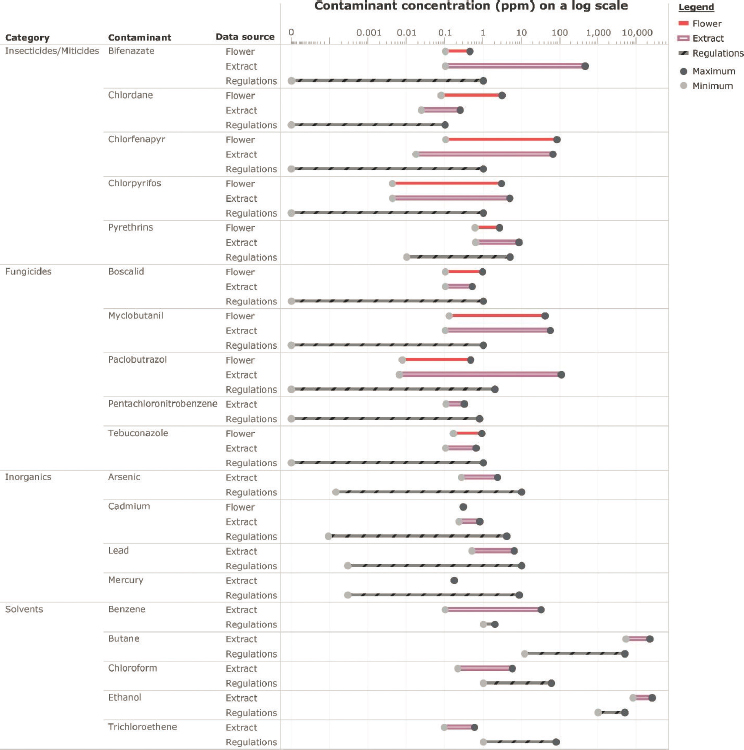

Testing for contaminants such as pesticides and inorganic metals (cannabis is a hyperaccumulator of metals [Bengyella et al., 2022]) is standard in most states (Gourdet et al., 2017; Pinkhasova et al., 2021). About two-thirds of states test for mycotoxins, moisture content, and microbials (Schauer, 2021). The number of contaminants tested for (Figure 4-4) and the action levels (pass or fail exposure limits) used to assess the contamination results vary widely. Most action levels are based on the EPA tolerance values for animal products (milk, eggs), which may be overly protective as cannabis may be consumed less frequently than milk or eggs (Jameson et al., 2022).

A study evaluating cannabis testing standards compared test results for nearly 10,000 samples previously analyzed by CannaSafe (a testing laboratory licensed in California) with the jurisdictions’ range of action levels. The study found that the range of contaminant concentrations varied widely, as did the action levels (Figure 4-5). The regulatory responses would vary accordingly.

Risk Mitigation Education Campaigns

The committee found limited but emerging risk mitigation education campaigns in use across states. Such programs exist in Colorado and Canada (Brooks-Russell et al., 2017; Fischer et al., 2017). Initial campaigns in 2014, which took more of a prohibitionist approach across all ages, did not produce the same impact, paving the way for future public education campaigns to branch out to focus on risk mitigation for those who use cannabis, focused especially on impaired driving and parents with young children, who face an accidental ingestion risk.

NOTE: EPA = Environmental Protection Agency.

SOURCE: Jameson et al., 2022.

After the initial launch of the health department’s “Good to Know” campaign, Colorado adults familiar with the campaign were 2.5 times more likely to know fundamental cannabis laws, with those who used cannabis being more knowledgeable than those who did not. Adult perceptions of the risks and health effects of cannabis use also increased significantly after the campaign. The number of those who knew the risks of driving after using cannabis increased by 23 percent, and those who realized that daily use could impair memory increased by 26 percent (Brooks-Russell et al., 2017).

The health department’s evaluation showed that the number of adults prepared to talk to their children about the risks of using cannabis had increased by 12 percent since the campaign began. Following an additional campaign developed for youth (“Protect What’s Next”), youth were more likely to agree that cannabis made it more difficult to think clearly and complete tasks.

NOTES: Action levels were not found in six jurisdictions with legalization. The concentration levels are based on 141 flower and 423 extract samples that had detected contamination in the compliance testing of 5,654 cured cannabis flowers and 3,760 cannabis extracts in California between June 2020 and May 2021. The chemical analysis was conducted using methodologies that comply with California state regulations. Only four inorganics were analyzed in the samples. No arsenic, lead, or mercury was detected in the flower samples, and solvents were not tested. PPM = parts per million.

SOURCE: Jameson et al., 2022.

Because cannabis had been shown to have adverse health effects during pregnancy and breastfeeding, part of the education campaign focused on women of reproductive age. Ninety percent of these women agreed that using cannabis during pregnancy posed some risks.

Future campaign and educational outreach efforts launched in Colorado and other states continue to expand engagement with those who use cannabis. Colorado’s recent campaign, “Responsibility Grows Here” (CDPHE, n.d.), has gone further by utilizing “Meg the Budtender” as the primary educator and spokesperson on responsible use.

Canada has developed Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines to provide science-based recommendations on how those who choose to use cannabis can reduce their risks. The guidelines, listed below, are based on a review of the literature on potential levers for lowering risk (Fischer et al., 2017):

- The most effective way to avoid the risks of cannabis use is to abstain from use.

- Delaying cannabis use, at least until after adolescence, will reduce the likelihood or severity of adverse health outcomes.

- Use products with low THC content and high CBD:THC ratios.

- Synthetic cannabis products, such as K2 and Spice, should be avoided.

- Avoid smoking burnt cannabis and choose safer inhalation methods, including vaporizers, e-cigarette devices, and edibles.

- If cannabis is smoked, avoid harmful practices such as inhaling deeply or breath-holding.

- Avoid frequent or intensive use, and limit consumption to occasional use, such as only one day a week on weekends or less.

- Do not drive or operate other machinery for at least 6 hours after using cannabis. Combining alcohol and cannabis increases impairment and should be avoided.

- People with a personal or family history of psychosis or substance use disorders, as well as pregnant women, should not use cannabis at all.

- Avoid combining any of the risk factors related to cannabis use. Multiple high-risk behaviors will amplify the likelihood or severity of adverse outcomes. (p. 4)

Although the guidelines were based on a literature review, their effectiveness has not yet been evaluated in an empirical study.

Primary Prevention Education to Discourage Cannabis Use

Primary prevention programs have been initiated in many communities, although the committee found no catalog of campaigns related to legal cannabis across states and jurisdictions. Several common approaches

to primary prevention are peer association, family involvement, community-based programs, and media campaigns. These interventions target individuals (through skills development), families (through communication), schools (through educational programs), and communities (through environmental changes and policy). By addressing cannabis use at its roots, primary prevention strategies aim to prevent initiation and promote healthy choices.

Although many different programs can be implemented across jurisdictions to discourage cannabis use, the effectiveness of such programs is mixed. A systematic review found low to moderate evidence for the effectiveness of primary prevention programs in deterring substance use among adolescents. Results indicated that adolescents who received a brief intervention generally reduced their alcohol and cannabis use more compared with adolescents who received no intervention at all. However, adolescents who received a brief intervention did not reduce their alcohol and cannabis use more than adolescents who received information-only interventions (Carney et al., 2016).

A systematic review found the most robust evidence for universal school-based interventions that target multiple risk behaviors, demonstrating that such programs may be effective in preventing engagement in tobacco use, alcohol use, illicit drug use (which included cannabis), and antisocial behavior and in improving physical activity among young people, but not in preventing other risk behaviors. The results of this review do not provide strong evidence of benefit for family- or individual-level interventions across the risk behaviors studied (MacArthur et al., 2018).

Another systematic review of primary prevention programs for substance use among children and youth found the most substantial evidence of effectiveness for the Life Skills Training Program (LST). LST targets elementary to high school settings and is delivered by teachers or trained moderators, addressing such topics as misunderstandings about drugs, decision making, problem solving, and stress and anxiety management. Across the 17 LST evaluations reviewed, 10 found a reduction in use of substances, including alcohol and drugs, among adolescents (Tremblay et al., 2020). However, poor reporting and concerns about variation in the quality of evidence highlight the need for greater investment in rigorous evaluations of universal primary prevention interventions directed at children and adolescents (MacArthur et al., 2018). Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development provides information on primary prevention programs for children and adolescents with a demonstrated effectiveness for substance use prevention (Mihalic and Elliott, 2015).

Community-level prevention programs, such as the Drug-Free Communities (DFC) Support Program, may be effective. Participants in this program had lower cannabis use relative to participants in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, which was used for comparison purposes (ONDCP,

2023). The DFC Support Program is a national initiative funded by the federal government and led by ONDCP in collaboration with the CDC; the program is aimed at preventing and reducing youth substance use by empowering local communities. DFC grants are awarded to coalitions comprising representatives from various sectors, such as schools, parents, law enforcement, and youth organizations. These coalitions develop and implement evidence-based strategies for addressing local substance use risk factors and promoting protective factors that encourage healthy choices among youth (CDC, 2023).

Mass media campaigns to prevent illicit use of drugs, including cannabis, are widespread. A systematic review of media campaigns to prevent illicit drug use identified 23 studies of designs involving 188,934 young people conducted in the United States, Canada, and Australia. The studies tested very different interventions and used several questionnaires to interview the young people about the effects of the interventions. Because of the variability in interventions studied and methods used, the authors could not reach substantive conclusions (Ferri et al., 2013).

Building a Strong Cannabis Workforce

Building a strong cannabis workforce will require collaborations among public health authorities within each state and across states and among cannabis regulators, clinical providers, and the cannabis industry. Colorado has established a network with a point of contact for cannabis in each county or city health department. The state health department also learns about emerging issues from the local public health officials. The health department, in conjunction with the Colorado Department of Revenue’s Marijuana Enforcement Division, holds science policy forums and educational conferences for local and state public health officials to learn about and discuss cannabis-related public health topics. The health department is creating educational materials for health care providers to inform them about cannabis-related topics (Ghosh et al., 2016).

Several states and Canada require or encourage responsible vendor training of cannabis retail sales staff. The Massachusetts program, for example, teaches compliance with regulations; licensing requirements; product labeling; acceptable payment methods; tracking systems; methods for verifying customer age, identifying valid ID, and determining whether a sale is legal based on the customer’s age; and techniques for handling a suspected underage purchase. The training also covers the physiological and cognitive effects of cannabis, including its effects as a stimulant, depressant, and hallucinogen, as well as ways to discuss the legal and safety aspects of cannabis use, such as how cannabis impairs driving and the legal limitations on consumption locations (CCCM, n.d.).

A few studies have reviewed the effectiveness of responsible vendor training (Buller et al., 2019, 2020, 2021). One study used a randomized pre–posttest controlled design to evaluate the impact of online training in responsible cannabis vendor practices on compliance with ID checking regulations. The training was provided to a random sample of state-licensed adult-use cannabis stores (N = 175) in Colorado and Washington in 2016–2017. The study found that the training increased refusal to serve buyers who appeared young and failed to provide a state-approved ID. However, it did not improve refusal rates overall, although stores with lower refusal rates at baseline and those that used the training may have benefited (Buller et al., 2021). A similar study found that training alone did not deter sales to customers who appeared to be alcohol impaired (Buller et al., 2020).

Cannabis legalization is changing clinical practice. Clinicians need to understand the new laws, health risks, and safety factors associated with cannabis use. Clinical providers may need to modify clinical procedures (e.g., patient–provider communication, increase in substance use screenings) and undergo additional training so they know how to talk to patients about cannabis use. A survey of 114 clinical providers in Colorado found that clinicians were knowledgeable about cannabis laws. However, surveys of students in the health professions (medicine, nursing, pharmacy, social work) indicate that these students lack knowledge of and receive no education on the topic. Surveys of clinicians show they are uncomfortable counseling patients about the specific health risks of cannabis use and lack confidence in their knowledge. Clinicians expressed caution with regard to legalization and perceived potential risks, especially for youth and those who are pregnant or breastfeeding (Brooks et al., 2017).

NIOSH has conducted several Health Hazard Evaluations of the hazards faced by cannabis workers. Cannabis cultivation workers face hazards similar to those in other agricultural workforces, including exposure to respiratory irritants and ergonomic injuries. Indoor cultivation poses some unique hazards—greenhouses and tents can harbor high levels of fungal spores, bacteria, pesticides, and endotoxins, posing potential allergic and respiratory concerns (Beckman et al., 2023; Couch et al., 2019; Sack et al., 2023). Additionally, the cannabis plant exhibits allergenic properties (Beckman, 2024; Decuyper et al., 2020).

In July 2021, the Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety at the University of California, Davis, hosted a virtual meeting titled “Cannabis Industry: Setting Priorities for Occupational Health.” This meeting aimed to identify the most pressing research, policy, and training needs to safeguard cannabis workers from occupational illness and injury. The meeting identified the need for occupational safety standards

and best practices for trimming machines, pesticide management, allergen control, wildfire preparedness, and psychosocial support (Schenker and Beckman, 2023).

Improving and Innovating with Ongoing Cannabis Evaluation

Evaluation is essential to ensuring effective cannabis policy. It can determine whether the right questions are being asked of the cannabis surveillance system, whether the cannabis policies are appropriate, and whether the prevention education and workforce campaigns are working. Policies have changed when problems have been identified, as in the example previously described of vitamin E acetate being banned from cannabis inhalation products following the 2019 EVALI outbreak. Several states partner with universities to support continuous evaluation and research aimed at monitoring essential outcomes (Ghosh et al., 2016).

Cannabis Assurance: Findings

The committee found that states have adopted many measures for public health assurance related to cannabis policy. The efforts at consumer protection regarding product safety testing are commendable, but there are inconsistencies across the state programs and issues with laboratory quality. Guidelines related to lowering the risk of use have been implemented in some localities, as have primary prevention media campaigns, which appear to improve consumer knowledge of the risks of cannabis. The Drug-Free Communities Support Program, the Life Skills Training Program, and other programs identified by Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development can all be leveraged to inform primary prevention for substance use. Encouraging a robust public health workforce for cannabis is critical, as are communication and information sharing within and between states with legalized cannabis. Training of retail sales staff is also needed, as they are routinely asked for advice on cannabis use, and audits have found that best practices for public health protection are not followed consistently. Clinician training is important as well because providers are not confident in discussing cannabis use with patients.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This analysis of the application of the core public health functions to cannabis policy underscores the need for a more comprehensive public health approach to cannabis in the United States. Prioritizing public health alongside economic considerations, ensuring balanced stakeholder involvement, implementing consistent consumer protection measures, and fostering a well-trained workforce are critical steps in promoting responsible

cannabis use. The policy landscape is complex, marked by an initial focus on economic outcomes in early legalization efforts. Public health considerations, such as reducing dependence and underage use, were often lower priorities. Similarly, consumer awareness of cannabis-related health risks received minimal attention.

Conclusion 4-1: Cannabis policy discussions need to consider impacts on public health. Inadequate inclusion of public health in cannabis policy decisions has limited the application of the core public health functions in states that have legalized cannabis for adult or medical use. Further development of the core public health functions as related to cannabis is therefore needed.

Currently, cannabis surveillance data are collected and analyzed by various entities with limited coordination. While most states are completing some components of a surveillance system, many systems are incomplete. State surveillance systems are underfunded, limiting the frequency of analyses and data dissemination, which in turn limits their link to action. Only Colorado has a complete system with regular analyses, research, and plans for reporting to policy makers, an important activity that may lead to public health action. Despite their limitations, diverse data sources, such as surveys, health records, and mortality statistics, are available, related mainly to the products used. Consistent use and application of the essential components of a public health surveillance system—data collection, analysis, and dissemination—would create a more comprehensive picture of cannabis use and its health impacts, ultimately informing practical public health actions. The CDC has a cannabis surveillance plan that is missing such elements as approaches to data dissemination, a link to action, and regular evaluation. Collaboration with federal partners, such as the departments of Agriculture and Commerce, is also needed to gain an understanding of cannabis production. The FDA has passive reporting systems to monitor product safety (FAERS and CAERS). However, it is difficult to interpret the data from these systems because increased reporting may be a function of increased knowledge that the system exists.

Recommendation 4-1: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in conjunction with its federal, state, tribal, and territorial partners, should create an adaptable public health surveillance system for cannabis. This surveillance system should include, at a minimum, cannabis cultivation and product sales, use patterns, and health impacts. It should also include all the essential components of a public health surveillance system: a surveillance plan, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, data dissemination, a link to action, and regular evaluation.

The regulatory structure for cannabis is evolving, with dedicated cannabis control commissions emerging. While public health agencies are increasingly involved in policy development, their role in overseeing adult-use cannabis remains uneven. Public engagement efforts, while present, lack inclusivity, potentially overlooking the perspectives of marginalized communities.

The legal cannabis industry exerts influence through lobbying and donations, raising concerns about potential bias in policy development. Furthermore, the limited adoption of conflict-of-interest provisions in medical cannabis states is a cause for concern. Industry influence on policy development is not new to the cannabis industry. The regulated industry can provide valuable input in the initial scoping and problem formulation phases of the policy development process. However, best practices would be for policy-making organizations to have conflict-of-interest policies that bar those with financial ties to the regulated industry from being involved in writing the policies. Policy decisions are typically posted for 30 days before they become final rules, which allows for input from the regulated industry and other relevant interested parties.

Conclusion 4-2: Cannabis policies have been developed without adequate protection against undue industry influence. Industry lobbying and conflicts of interest have interfered with the policy development. As the industry has expanded, it has stymied regulations intended to protect public health by downplaying the risks and overstating the benefits of cannabis.