Cannabis Policy Impacts Public Health and Health Equity (2024)

Chapter: 5 How Cannabis Policy Influences Social and Health Equity

5

How Cannabis Policy Influences Social and Health Equity

Health equity, through which “everyone has the opportunity to attain their full health potential, and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or any other socially defined circumstance” (NASEM, 2017, p. 32), is central to a public health approach to cannabis policy. Factors that benefit or harm health are unequally distributed across populations. Race, ethnicity, poverty, age, life stage, gender identity, sexuality, and social factors can place people at disproportionately high risk for many acute and chronic diseases compared with the general population (NASEM, 2017).

While some distinctions are made between social equity, which often focuses on addressing racism and other forms of discrimination, and health equity, the two concepts are deeply intertwined. Addressing social equity by dismantling structural racism, for instance, directly impacts health equity by disrupting the mechanisms through which health inequities persist. Accordingly, combatting the influence of systemic or structural racism1 in the United States through public health practice has become an increasingly high priority among many public health leaders (Bassett and Graves, 2018). In 2018, New York State Health Commissioner Mary Bassett called for

___________________

1 “Structural racism” is the totality of ways in which a society fosters racial and ethnic inequity and subjugation through mutually reinforcing systems, including housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, and the criminal legal system. These structural factors organize the distribution of power and resources (i.e., the social determinants of health) differentially among racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, perpetuating racial and ethnic health inequities. The key difference between institutional and structural racism is that structural racism happens across institutions, while institutional racism happens within institutions. “Systemic racism” is another term used to describe this (NASEM, 2023a, p. xxv).

recognizing that racist ideas have shaped public health practice and stressed that health equity could not be achieved without addressing systemic racism (Bassett and Graves, 2018).

Some have posited that cannabis legalization could reduce social inequities by mitigating the adverse consequences of the criminalization of cannabis use, possession, and sales, which has targeted minoritized groups (Golub et al., 2007; Resing, 2019). However, legalization does not eliminate cannabis policing, and increased policing in minoritized neighborhoods can happen for reasons unrelated to cannabis (Hinton and Cook, 2021). Moreover, even in states with legal cannabis markets, there are laws to be enforced, such as the prohibition of sales to those less than 21 years of age, laws banning smoking in public or near certain buildings, and bans on cannabis-impaired driving, all of which could be unequally enforced (Kilmer, 2019).

There are many reasons to be concerned about how the legal cannabis industry contributes to health inequities. Disproportionate marketing toward minoritized groups and concentration of retail stores in the neighborhoods in which they live, for example, could lead to unequal distribution of the health impacts of cannabis use. This chapter evaluates the impacts of cannabis policy on health equity by considering the criminal justice consequences of cannabis prohibition, assessing social equity programs adopted in some states, and evaluating the effects of cannabis policies on social determinants of health.

IMPACTS ON HEALTH EQUITY RELATED TO CRIMINAL JUSTICE

Entanglements with the criminal justice system can contribute to health inequities when increased policing or racism contributes to disparities in arrests and incarceration. Following incarceration, individuals are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality compared with the general U.S. population (Wang and Shavit, 2023; Wildeman and Wang, 2017). The stigma of a criminal record impacts not only those who committed the offense, but also the health of family members (Wildeman and Wang, 2017). Incarceration is associated with higher rates of chronic health conditions among both adults and children in the family (Wildeman and Wang, 2017; Wildman et al., 2019). There are stark differences by race in this regard; nearly 25 percent of Black Americans have three or more immediate family members who have been incarcerated for any reason, compared with just over 5 percent of White Americans (Sundaresh et al., 2021).

Impacts of Cannabis Arrests

Cannabis arrests have varying impacts on people’s lives. From 2010 to 2019, there was an average of 692,115 cannabis arrests a year (Chapter 1), very few of which resulted in incarceration (Kachnowski et al., 2023).

In some cases, arrest may cause people to make changes that positively impact their lives. However, others are negatively affected, and some are incarcerated, which impacts their health and well-being. To learn more about those experiences, the committee invited speakers affiliated with the Last Prisoner Project2 (Jason Ortiz, Donte West, Stephanie Shepherd, and Kyle Page) to describe how the criminal justice system has impacted their lives. All four speakers shared stories of the devastating impact of cannabis-related criminal justice entanglements; none had faced charges of violent crime.

Jason Ortiz described his arrest for cannabis use as a teen, the fear when he was arrested at school, how he almost did not graduate high school, and how he benefited from a change in Connecticut’s Higher Education Act that removed the federal aid elimination penalty from his arrest.

Donte West described the emotional toll and the fight to overturn his conviction for possessing a pound of cannabis. West emphasized that his conviction impacted his life in ways that cannot be quantified and said, “When you get incarcerated, not only your freedom gets taken away, but also you don’t get to make memories with your loved ones.”

Kyle Page highlighted the dehumanization during sentencing and the struggle to rebuild a life after prison, especially with regard to employment and family relationships. Kyle shared his experience of being sentenced for cannabis possession. His lawyer explained they needed to “humanize” him for the judge. Page said:

That was extremely frightening to me to think that the person in charge of the rest of my life, in charge of my daughter’s father’s life, needed me to be humanized. Think of the gravity—you could do 20 years in prison or 6, depending on whether someone judged me to be a human. That’s a frightening thought.

Stephanie Shepherd emphasized the long-term consequences of arrest and incarceration, including limitations on housing, credit, and professional opportunities. She was age 30 when she began using cannabis, 41 when she was convicted of conspiracy to distribute cannabis, and 50 when she was released. Now, at age 54, she still struggles to get her life back together. Shepherd described the shameful feeling she had when she first tried to find employment after release. She said,

When I got out, and I had to go to a job interview with an ankle monitor on, I cried in that job interview because I had never had to explain to someone why I couldn’t stay late, where I just came from, why there’s a 10-year gap in my work experience, and this was just a coffee shop [job].

___________________

2 Video recordings of the committee’s public meetings can be found on the project page: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/public-health-consequences-of-changes-in-the-cannabis-landscape.

The session showed how incarceration disrupts lives, separates families, and creates lasting hardships. Reintegration into society is a challenge, especially given the difficulties of finding housing and employment with a criminal record for cannabis offenses.

Impacts of Changes in Cannabis Policy on Inequities in Arrests

With changes in laws, enforcement practices, and norms for cannabis has come a noteworthy reduction in arrests for cannabis possession. While historical data on the number of such arrests do not exist,3 the best national data source on these arrests suggests that they decreased from 613,986 in 2002 to 500,395 in 2019, an 18.5 percent reduction.4 Given how much cannabis use increased over this period (Chapter 3), this reduction means that the risk of arrest conditional on use has decreased even more. Based on data on the total number of cannabis use days from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health for 2002 and 2019 (Chapter 3), cannabis possession arrests per million days of cannabis use decreased by roughly 69 percent over this period.5

To assess some of the potential racial disparities in cannabis arrests, the committee received data from two research teams that published race-specific analyses using Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) cannabis possession arrests (Gunadi and Shi, 2022a; Sheehan et al., 2021). Both papers use subsets of states (Gunadi and Shi use 36 states,6 while Sheehan and

___________________

3 The national data reported before 2021 were found in the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI’s) annual Crime in the United States report. These data underestimate the total number of cannabis possession arrests because of a recording procedure known as the “hierarchy rule,” which means that if someone is arrested for multiple offenses at the same time, only the most serious one is reported to the FBI (e.g., if someone were arrested for robbery and cannabis possession, the law enforcement agency would record only the robbery arrest since it was more serious). In 2021, the FBI began requiring all states to comply with the National Incident-Based Reporting System, which allows multiple offenses to be linked to a particular arrest. However, not all localities are yet compliant, and compliance varies by jurisdiction (NASEM, 2023b).

4 The FBI reported that in 2002, there were 1,538,813 arrests for drug abuse violations, and 39.9 percent of these were for cannabis possession, meaning there were 613,986 cannabis possession arrests (Tables 28 and 29, FBI UCR, 2003). The comparable figure for 2019 was 500,395 cannabis possession arrests (1,558,862 * 32.1%). The 2019 data are the most up-to-date and reliable information because data for other years may have been impacted by missingness due to the COVID-19 pandemic (FBI CJISD, 2019).

5 In analyses presented in Chapter 3, the committee found that there were approximately 2.1 billion days of cannabis use in 2002. By 2019, that figure had increased to 5.5 billion days. Using the arrest data from the FBI, this means that arrests per million use days decreased from roughly 292 in 2002 to 91 in 2019, or 69%.

6 Some analyses in Gunadi and Shi (2022b) include Florida, and thus reflect data from 37 states.

SOURCES: Generated by the committee from Gunadi and Shi, 2022a; Sheehan et al., 2021.

colleagues use 43 states) and focus on arrests of both Black and White people.7 The levels and trends are similar across both datasets; the correlation coefficient for cannabis possession arrests of Black people for the two datasets was 0.998, while that for cannabis possession arrests of White people was 0.997 (Figure 5-1). Comparing total cannabis possession arrests for 2002–2004 and 2017–2019 (3-year periods used to mitigate single-year anomalies), data from both papers show large reductions in arrests for White people over both periods (Gunadi and Shi: –22.7 percent; Sheehan

___________________

7 As noted by Gunadi and Shi (2022b): “Finally, the UCR data has limited information on arrests by race. Other than arrest data for Blacks and Whites, data are only available for American Indians and Asians. Ethnicity information, such as Hispanic origins, is unavailable for most of the years” (p. 2).

et al.: –24.6 percent). For Black people, however, the data show nearly the opposite, with both data sources documenting substantial increases (Gunadi and Shi: 28.1 percent; Sheehan et al.: 26 percent). While these data have limitations and do not cover the entire country, they emphasize continued inequity in arrests for cannabis possession and deserve additional analysis (Gunadi and Shi, 2022a; Sheehan et al., 2021).

Collateral Consequences

The health and economic impacts of arrests and incarceration extend far beyond the initial punishment. Laws, regulations, and the policies of private organizations, including businesses and educational institutions, as well as social stigma, all contribute to the harms people experience after entanglement in the criminal justice system. Examples include job loss, housing insecurity, and limitations on educational and business opportunities. Collateral consequences for families and communities are discussed below (Maurer, 2017).

Impacts of Incarceration on Economic Security

Incarceration of youth is associated with limited educational opportunities, with subsequent adverse impacts on economic security and wage growth (Western, 2002). Criminal arrests during adolescence are associated with greater criminal activity in young adulthood and midlife, further limiting educational and employment opportunities (Green et al., 2019). Formerly incarcerated people are twice as likely as the general public to fail to complete high school or obtain a general equivalency diploma, and eight times less likely to complete college. And formerly incarcerated people of color are at the greatest educational disadvantage (Couloute, 2018).

Providing educational opportunities in carceral settings has the potential to improve public safety, reduce recidivism, and improve social integration following release (Royer et al., 2021). More than two-thirds of currently incarcerated individuals express a desire to enroll in academic courses or programs while incarcerated (Rampey et al., 2016). One study estimates that recidivism is reduced by 43 percent among those who participate in such educational programs, yet numerous barriers exist to providing them (Davis et al., 2014). For example, some prisons require drug testing for those wishing to participate in higher education programming provided by community-based academic institutions (Royer et al., 2021). Additionally, most incarcerated individuals are eligible for postsecondary education, but access is hampered because incarcerated people are banned from accessing funding for education, such as Pell grants (Oakford et al., 2019).

STATE- AND LOCAL-LEVEL CANNABIS EQUITY PROGRAMS

Many state and municipal governments have instituted policies and programs to address the harms of cannabis prohibition (Wakefield et al., 2023). State-level cannabis social equity efforts include record relief and resentencing, assistance for industry participation (technical and financial), and community reinvestment. Policies in states that were early to adopt cannabis legalization did not include social equity provisions, at least initially, whereas more recently, equity provisions have been included in tandem with cannabis legalization reforms (Love et al., 2022; Schlussel, 2021). In 2023, the policies of 22 of the 24 states with legal adult use had social equity provisions (Table 5-1). Record relief and resentencing are the most common social equity provisions, and all legal adult-use states with social equity provisions have some level of criminal justice reforms. Twenty states where cannabis is legal for adult use are considering industry participation assistance, and 18 states are considering community reinvestment provisions (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024).

Record Relief and Resentencing

Record relief expunges (clears) or seals the records of cannabis offenses, while resentencing involves changing the sentences for those currently incarcerated for a cannabis-related offense. All states with a social equity program have some record relief, but only eight include resentencing provisions in their policies (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024).

The way record relief programs operate varies (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024; Love et al., 2022; Schlussel, 2021; Wakefield et al., 2023). One of the most important variations is in whether the relief is automatic or government initiated, or whether it requires the person with a record to petition for the relief. In 2024, 16 states had government-initiated record relief, and 6 had solely petition-based programs, meaning that those with a criminal record must initiate the process to relieve their records (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024). Record relief programs also differ as to the types of offenses that can be relieved and whether the records are cleared or sealed (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024; Wakefield et al., 2023).

Petition-based record relief has many barriers to widespread use, limiting the number of people who benefit. Petition-based expungements require filing a formal petition with the court and may involve public hearings, fees, and other formalities. The court costs alone may deter eligible people from filing a petition. Public defenders or other free or reduced-cost legal services are often unavailable, and hiring a lawyer may not be financially feasible (Berman, 2018). Additionally, resource constraints may pose a challenge for court systems. High volumes of requests can create bottlenecks in

TABLE 5-1 Overview of Major Social Equity Policy Areas by State

| State | Record Relief and Resentencing | Community Reinvestment | Industry Participation Assistance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska (2014 by ballot) | No | No | No |

| Arizona (2020 by ballot) | Yes (enacted during and post legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| California (2016 by ballot) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted post legalization) |

| Colorado (2012 by ballot) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | Yes (enacted post legalization) |

| Connecticut (2021 legislation) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| Delaware (2023 legislation) | Yes (enacted pre-legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| Illinois (2019 legislation) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| Maine (2016 by ballot) | No | No | No |

| Maryland (2022 legislation) | Yes (enacted pre-legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| Massachusetts (2016 by ballot) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | Yes (enacted post legalization) |

| Michigan (2018 by ballot) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| Minnesota (2023 legislation) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| Missouri (2022 legislation) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| Montana (2020 by ballot) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | No | No |

| Nevada (2016 by ballot) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | No | Yes (enacted post legalization) |

| New Jersey (2020 by ballot) | Yes (enacted pre/post legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| New Mexico (2021 legislation) | Yes (enacted pre-legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| New York (2021 legislation) | Yes (enacted during and post legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| Ohio (2023 by ballot) | Yes (enacted pre-legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| Oregon (2014 by ballot) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | No | No |

| Rhode Island (2022 legislation) | Yes (enacted pre-legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| Vermont (2018 legislation) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | Yes (enacted post legalization) |

| Virginia (2021 legislation) | Yes (enacted pre-legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) | Yes (enacted during legalization) |

| Washington (2012 by ballot) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | Yes (enacted post legalization) | Yes (enacted post legalization) |

SOURCE: Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024.

processing applications due to administrative limitations and wait periods (Wakefield et al., 2023). Not surprisingly, then, data suggest that petition-based record relief has a serious uptake gap. One study evaluating record expungement, not specifically with respect to cannabis, estimated that among people legally eligible for expungement of criminal convictions, only 6.5 percent obtain it within 5 years of eligibility, but those who do obtain it experience higher wages and have a low subsequent crime rate (Prescott and Starr, 2019).

To address the barriers to petition-based record relief, many states and jurisdictions have committed to automatically clearing eligible records for people who have completed their sentences and remained crime free and to expanding the criteria for eligibility for clearance. Since 2018, 12 states (California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, New Jersey, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Virginia) have passed laws that align with the laws and policies8 of the Clean Slate Initiative.9

Social Equity Business Assistance

A fundamental goal of many state cannabis social equity programs is to help those harmed by cannabis criminalization to benefit financially from the legal market. The criteria for receiving support can include having prior involvement with the criminal justice system; being economically disadvantaged; living in or having resided in an economically disadvantaged area; and other considerations, such as veteran status, race, or ethnicity. The business assistance can include preferential licensing, financial support, and assistance (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024). Most cannabis social equity programs include industry support. Alaska, Maine, Montana, and Oregon are the only legal adult-use states without some social equity business assistance.

In 12 states, laws require that a particular portion of cannabis business licenses be allocated to individuals from communities that have been targeted unfairly by past cannabis enforcement. State regulators may also establish additional applicant criteria (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024). For example, Connecticut and New York reserve 50 percent of licenses for social equity applicants. New Jersey allocates 25 percent of licenses to applicants from selected impact zones. Other states—including Arizona, Delaware, Nevada, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Washington—specify the

___________________

8 https://www.cleanslateinitiative.org/states (accessed March 28, 2024).

9 The Clean Slate Initiative is an organization that “passes and implements laws that automatically clear eligible records for people who have completed their sentence and remained crime-free and expands who is eligible for clearance” (para. 1) (https://www.cleanslateinitiative.org [accessed March 28, 2024]).

number of equity licenses awarded, often dividing the numbers into cultivation, manufacturing, retail, and testing licenses. Nevada also has a license for cannabis consumption lounges, half of which are awarded to equity applicants (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024).

Twenty states have programs that provide license or business assistance (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024). Although each state’s program is different, some examples of license assistance include priority application review, reduced application fees, financial assistance programs to help launch a cannabis business, and education and training programs (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024).

Priority application review ensures that specific applications are processed more quickly. For example, the New Jersey Cannabis Regulatory Commission ranks priority groups based on diversity status, owner’s economic and criminal background, and physical location.10 Applications from higher-ranking groups are reviewed first (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024).

Reduced application fees are used in 11 of the 24 adult-use states (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024). The programs typically reduce or waive fees related to the initial application. Vermont uses a fee reduction schedule that begins with a full waiver and gradually increases over time, allowing social equity owners to achieve financial sustainability (Vermont CCB, n.d.). Delaware offers special microbusiness licenses with lower fees and less frequent renewals, catering to smaller-scale operations for those without the capital to start a large business (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024).

Financial assistance programs that can help launch a cannabis business are part of social equity programs in several states, including California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York. These programs offer funding assistance through grants, microloans, and no- or low-interest loans. How the funds can be used to support the business varies by state, and the loan repayment structures differ based on the loan terms (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024).

Technical assistance programs provide support and resources to cannabis business owners. These programs offer training on regulatory compliance, business planning, marketing strategies, and cultivation techniques. Some programs also include access to funding and mentorship opportunities. Colorado’s Accelerator License program helps cannabis business owners from communities impacted by cannabis prohibition by partnering those with social equity licenses with an established cannabis business. The established business can then advise the social equity licensee on how to run a successful business.11

___________________

10 https://www.nj.gov/cannabis/businesses/priority-applications/ end of page (accessed March 22, 2024).

11 https://sbg.colorado.gov/accelerator-program (accessed March 22, 2024).

Business assistance programs have several problems. While business assistance may benefit minoritized groups that want to participate in the cannabis industry, the industry has been in a constant state of change, making it difficult for businesses to profit. In addition to the investment risks of running a new business, the risks could grow if federal legalization allows (1) cannabis to cross state lines legally and (2) large corporations to become involved in the trade (Kilmer et al., 2021). Moreover, some early analyses have shown that social equity business programs have been abused and largely benefited wealthy people with political connections and sizable commercial cannabis companies. Some companies have canvassed lower-income areas to identify someone to apply for a license backed by the larger company (Lawrence and Minton, 2023). Business license programs could also contribute to health inequities. Entrepreneurs often start businesses near where they live, so social equity licenses could contribute to an overconcentration of retail outlets in communities that have experienced disadvantage and have been unfairly targeted by cannabis enforcement.

Community Reinvestment

Community reinvestment programs use a portion of the tax revenue generated by the sale of legal cannabis to address social and economic needs in communities that have been negatively impacted by cannabis prohibition (Hrdinova and Ridgway, 2024; Yang et al., 2023). The programs’ goals vary, but the funding structures typically include directed grant programs. The funds are used for education, mental health services, substance use treatment, economic development, violence prevention, and legal aid (Yang et al., 2023). The tax dollars generated by cannabis sales can be substantial. California’s community reinvestment grants, for example, total $50 million per year.12 It is estimated that if states designated just 25 percent of annual cannabis excise tax revenues to support mental health services, the result could be increased availability of psychiatric crisis units, coordinated specialty care, and suicide prevention services (Berg et al., 2023; Purtle et al., 2022). A 2023 report from the Tax Foundation estimates that if cannabis legalization were nationwide, it could generate $8.5 billion annually (Hoffer, 2023). Community reinvestment programs have many challenges. Tax revenue is a function of sales; Colorado, for example, saw tax revenues begin to decline in 2021 (CDR, 2024). Maintaining a grant program is also costly, and the grantee’s ability to deliver the intended results limits the grant program’s benefits. In addition, cannabis taxes could replace traditional

___________________

12 https://business.ca.gov/california-community-reinvestment-grants-program (accessed March 22, 2024).

funding for social programs. There are also social equity considerations regarding cannabis taxation (Yang et al., 2023). Those who have lower incomes and use cannabis may spend a higher proportion of their income on cannabis and thus are more impacted if taxes increase the price of cannabis. So those who are intended to benefit from the program may be paying an increased proportion of the cost (Jernigan et al., 2021).

State Social Equity Programs: Findings

State and local cannabis equity programs are a recent development aimed at addressing the social and economic harms caused by cannabis prohibition, which has disproportionately impacted communities of color. Cannabis legalization has spurred a range of social equity efforts in the United States that encompass criminal justice reform, assistance with industry participation, and community reinvestment programs. While these initiatives hold promise for mitigating the harms of cannabis prohibition, challenges remain in implementation and effectiveness. Addressing these challenges will ensure that social equity is a central feature of the legal cannabis industry. Start-ups may need help staying afloat in competitive markets to contend with predatory rent prices and loan repayments (Gerber, 2022). As these programs continue to develop, monitoring their effectiveness and adjusting as needed will be essential (Title, 2021).

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

For decades, research and scholarship have illustrated that social and structural factors—such as race, ethnicity, zip code, education level, employment, and income—impact health outcomes and thereby create significant health inequities (NASEM, 2023a). Systems of power, individual factors, and physiological pathways influence health equity. Systems of power are policies, processes, and practices that determine who gets resources and better opportunities for health. These systems can promote health equity or perpetuate inequities (access to basic needs, humane housing, meaningful work, and reliable transportation). Individual factors concern people’s responses to social, economic, and environmental conditions through their attitudes, skills, and behaviors and their interaction with biological predisposition. Physiological pathways refer to people’s biological, physical, cognitive, and psychological abilities (Peterson et al., 2021).

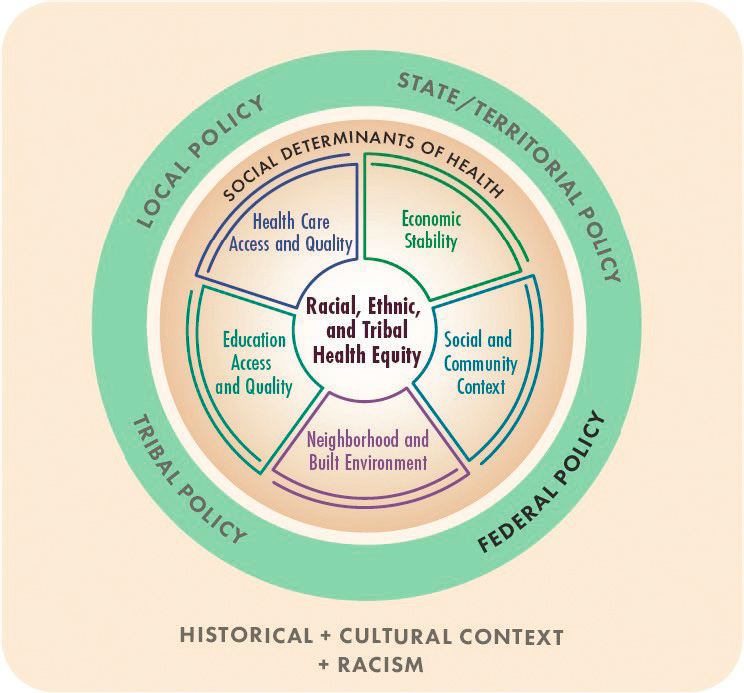

To understand how cannabis policy contributes to health equity, it is essential to consider the social and structural factors that impact the well-being of individuals and communities. These structural factors affect

local, state, and federal government; industry; and health care systems. The social determinants of health framework acknowledges the social and structural factors that must be addressed to improve health equity. Many different social-ecological models, describe how social and structural factors influence health. Healthy People 2030 and a recent National Academies report categorize the social determinants of health as economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context (HHS, n.d.; NASEM, 2023a). The committee considered how changes in cannabis policy can influence these social and structural determinants of health (Figure 5-2).

Source: NASEM, 2023a.

Economic Stability

The economic impact of cannabis legalization on communities is nuanced and still unfolding. Touted economic benefits of cannabis legalization include tax revenue, job creation, increased investment, reduced law enforcement costs, and increased tourism (Brown et al., 2023). There are also documented societal costs of cannabis legalization, which may impact economic stability (Chapter 6). While the economic impact of cannabis legalization is complex, valuable lessons can be learned from the current landscape, as well as from examples with other substances (e.g., retail availability and regulation of alcohol).

Taxation transfers income from people to the government. The state tax revenue from legalized adult-use cannabis exceeded initial estimates in 2021; states collected a combined $3 billion (Hoffer, 2023). However, it is important to note that cannabis tax revenues in Colorado (the longest-running legal market) began to decline in 2021 (CDR, 2024). Tax revenue can be used for various purposes, including education, infrastructure, social programs, and expansion of both prevention and treatment services for cannabis use. Given that estimates from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) for past-month cannabis use are slightly higher among those living in poverty compared with those in other income brackets (see Figure 3-9 in Chapter 3), cannabis taxes are regressive.

The legal cannabis industry does create legal jobs in cultivation, processing, retail, and testing (Levin, 2023). Job creation is complicated to assess because, ideally, the legal industry is slowly replacing the illegal industry, and there may be a transfer from illegal to legal jobs. Estimates suggest that hundreds of thousands of jobs have been created across the United States as a result of cannabis legalization (Cooper and Martinez Hickey, 2021). However, it is unclear if those are replacing those lost in the illegal industry.

There are tremendous inequities in the development of the cannabis industry, however, as it is skewed mainly toward White male entrepreneurs and employees. About 75–80 percent of retail outlets are owned by White people, and about 70 percent of those employees are White. Fewer than 6 percent of owners or employees are Black (Doonan et al., 2022; Harris and Martin, 2021; Swinburne and Hoke, 2019). There are many reasons for these employment inequities, such as the collateral consequences of arrests (Maurer, 2017) and lower access to the capital needed to start a business (Harris and Martin, 2021).

Legalization and the increased prevalence of use that follows affect employment in other sectors as well. Many industries use pre- or postemployment drug testing. The practice is controversial, particularly where

safety and security concerns are not paramount (Cohen et al., 2022; Hoffman, 1999; Price, 2014; Treglia et al., 2022). Following the passage of the Drug-Free Workplace Act of 1988 (41 USC 81), which requires federal grant recipients or contractors to establish and maintain a drug-free workplace policy, 40–45 percent of U.S. workers reported the use of drug testing in their workplaces (Carpenter, 2007; Oh et al., 2023). Black workers are tested more frequently than White workers, even controlling for occupation (Becker et al., 2014; Carpenter, 2007). Since employer drug testing can prevent people from acquiring or maintaining a job, these disparities likely impact health equity.

At the committee’s second public meeting, Ryjean Reid described how employer drug testing impacted him personally. He was employed as a first-line manager at an airline and lost his position after testing positive for cannabis last year. Based on his experience with cannabis testing, he said he thinks that “cannabis prohibition creates a second class of citizenship in the United States, and these inequities in enforcement are overall damaging in terms of public health.”

As cannabis policies have shifted, employers have changed drug testing practices. Many cannabis legalization laws have included explicit language protecting employee rights concerning cannabis use outside of regular work hours. According to data from the National Conference of State Legislatures, as of January 22, 2024, 8 of the 24 states with adult-use cannabis legislation (California, Connecticut, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Washington) had statutes protecting employees’ rights to use cannabis while off duty.13 These states have either statutory or constitutional language requiring employers not to discriminate at the time of hiring or against off-duty use of cannabis by employees. However, some of these laws exempt employers in particular occupations (e.g., construction in California). None of these laws prevent employers from testing after an accident or for cause.

The economic impacts of cannabis legalization are complex, with potential benefits and drawbacks for communities. To date, cannabis legalization may not be improving economic inequities. The cannabis industry, while generating tax revenue for a state’s government, may not be benefiting those harmed by cannabis policing, and employer drug testing practices may impact employment status among Black people because the practice is applied inequitably.

___________________

13 Data from the National Conference of State Legislatures, last updated January 22, 2024, https://www.ncsl.org/health/cannabis-and-employment-medical-and-recreational-policies-in-the-states (accessed August 14, 2024).

Educational Access and Quality

Cannabis policy has complex impacts on educational access and quality. In the United States, public school funding for kindergarten through 12th grade (K–12) comes primarily from state and local revenues, such as local property taxes, personal and corporate income taxes, and excise taxes. These revenues are then distributed to school districts based on formulas that consider a variety of factors, including local property tax revenue, area needs, and school attendance (ECS, 2024; Peter G. Peterson Foundation, 2023; Skinner and Riddle, 2019). This means that resources allocated to any neighborhood public school are tied to the value of local property in the area and how many students are present. Some states use revenue from cannabis taxation to support schools; as of September 6, 2022, Alaska, Colorado, Michigan, Nevada, New York, and Oregon used at least a portion of the tax revenue to support educational programs (Lozier, 2022).

Cannabis policy can impact educational access and quality within a community through at least two channels. First, cannabis policies that influence the availability of, access to, and marketing of kid-friendly products might impact either the prevalence or frequency of cannabis use by youth. Youth use of cannabis can negatively impact cognitive function, such as attention and working memory, especially during critical developmental stages in adolescence (Volkow et al., 2016). These impacts can lead to poorer performance in school and reduced motivation to attend classes, impacting absenteeism or enrollment status. Second, policies that focus on enforcement against cannabis use and possession, particularly enforcement targeting vulnerable youth populations, can lead to differential attendance and enrollment in schools, thereby impacting school resources available for education for everyone in the neighborhood.

Observational data suggest a direct relationship between cannabis misuse and lower educational achievement among adolescents and young adults (Thompson et al., 2019). The biological plausibility of the link is well supported by evidence that cannabinoids directly affect the areas of the brain involved in working memory, attention, and learning (Bhattacharyya et al., 2015; Bloomfield et al., 2019; Bossong et al., 2012; Ramaekers et al., 2021), and is further supported by experimental evidence showing a deleterious dose–response relationship between delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and working memory and learning (Curran et al., 2002; Ranganathan and D’Souza, 2006). Additional preclinical and experimental evidence shows a strong biologically based dose–response relationship between delta-9 THC and motivation (Pacheco-Colón et al., 2018; Paule et al., 1992; Volkow et al., 2016), as well as cognition and decision-making behavior (Ferland et al., 2023). Well-designed longitudinal studies have found an association between early onset or frequency of cannabis use during adolescence and decreased academic performance (Horwood et al., 2010). This finding is

further supported by quasi-experimental evidence comparing academic achievement before and after cannabis prohibition, which supports the connection between cannabis use and poorer school performance (Marie and Zölitz, 2017). Moreover, the 2015–2019 NSDUH revealed that not only youth with cannabis use disorder but also those with subclinical nondisordered cannabis use had more difficulty concentrating and worse academic performance (Sultan et al., 2023). The above research does not conclusively support a causal connection between cannabis use and dropping out of school, as the findings may be subject to potential confounding caused by mental health disorders and other factors (Esch et al., 2014; Lorenzetti et al., 2020). Nonetheless, it supports a plausible connection between cannabis use and dropping out of school, which is why substantial research attention has been paid to the impact of changing cannabis policies on youth substance use.

Enforcement of existing cannabis laws can also impact school attendance and enrollment in at least two ways. First, schools’ zero-tolerance policies mandating suspension or expulsion for simple drug possession directly increase suspensions and expulsions from those schools while also contributing to school alienation, academic deterioration, and delinquency among the affected students (AAP and Committee on School Health, 2003; APA Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008; Wald and Losen, 2003). A recent survey of 1,080 public schools in 2021 found that 62 percent still retained zero-tolerance policies and that the policies of 85 percent of these schools extended to possession of illegal drugs, which would include cannabis for anyone under age 21 (Perera and Diliberti, 2023).

A second way enforcement might impact school attendance is through additional policing that occurs in low-income and ethnically diverse neighborhoods (Gaston, 2019; Lum, 2010), which can increase the chances that youth in those neighborhoods will be arrested for simple possession or use (Nguyen and Reuter, 2012). These arrests lead to an immediate absence from school due to criminal justice engagements and increase the likelihood of dropping out of school (Kirk, 2009; Kirk and Sampson, 2013), affecting the resources available to the broader school environment (since absenteeism reduces school funding).

Cannabis liberalization policies also have potential effects on school access and quality that warrant further study. To the extent that cannabis legalization policies do not address the criminality of youth possession and use or lead to changes in school zero-tolerance policies, they are likely to have only negative impacts on school access and education quality because they increase the potential for youth cannabis access and use. If, however, legalization policies are coupled with decriminalization statutes, which eliminate the criminal status of simple possession or use of small amounts of cannabis for both adults and people under 21, they may bring some benefit to disadvantaged neighborhoods and schools at risk of differential enforcement of criminalization policies (Tran et al., 2020; Wald and Losen, 2003).

Health Care Access

Cannabis policies intersect with access to health care through employment, health insurance benefit coverage, and willingness to seek treatment for health conditions. Cannabis prohibition has negatively impacted all three areas; thus, revision of these policies with legalization should improve health care access. Cannabis policies could even improve health care quality if, for example, the justice system mandated treatment for substance use, particularly as part of the juvenile justice system, should that treatment in fact be effective.

Employment impacts health care because the primary source of health insurance in the United States is through employers (Keisler-Starkey et al., 2023), where coverage is highly subsidized by preferential tax treatment and employer contributions (Gruber, 2011). Given that the prices for health care in the United States are much higher they are in other developed countries (Dieleman et al., 2017; Papanicolas et al., 2018), Americans rely on health insurance to finance their use of health care services. The collateral consequences of an arrest restrict access to employment and some access to health insurance, although coverage through Medicaid is often allowed after release.

Even individuals without a criminal record can experience limitations in their health insurance coverage due to the use of cannabis. This is the case because following a model law developed in 1947 by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, several U.S. states allow insurance companies to deny benefits for emergency care if the injury or condition prompting the emergency visit is due to intoxication or being under the influence of any drug that a provider did not prescribe (Azagba et al., 2024). Since medical cannabis policies in the United States are technically outside of the health care system because of federal cannabis prohibition, medical use recommended by a medical provider is not necessarily protected. As of 2023, nearly half of all U.S. states (N = 23) retained denials for intoxication (APIS, 2023).

Punitive legal responses to prenatal drug use have negative health implications. Punitive policies on prenatal drug use exist in nearly half of U.S. states. As of 2022, three states had criminalized prenatal drug use (Alabama, South Carolina, and Tennessee). The most common approach to enforcement of punitive practices involves using child protective services to remove children from mothers who used drugs during pregnancy. Twenty-three states have child removal laws, and six states (Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, North Dakota, and Texas) clearly consider prenatal drug use sufficient grounds for child abuse substantiation or termination of parental rights (Bruzelius et al., 2024). These policies can be triggered by evidence of drug use or even by a newborn having symptoms of withdrawal.

Overall, punitive prenatal drug policies create a harsh legal landscape for pregnant people struggling with substance misuse. Punitive prenatal drug use policies are counterproductive, contributing to underreporting of prenatal cannabis use, avoidance of prenatal care, and missed opportunities for education and intervention (Bruzelius et al., 2024; Pack et al., 2022). Chronic stress can worsen health conditions and make it more difficult to manage substance use. If pregnant people fear being reported to the authorities, they may be less likely to seek treatment for substance use. The lack of treatment can lead in turn to continued substance use, which does not decrease exposure to the developing fetus (Atkins and Durrance, 2020; Carroll et al., 2021; Chang et al., 2019; Faherty et al., 2019; Meinhofer et al., 2022). In addition, these punitive policies have the potential to exacerbate existing inequities. For example, studies have shown that relative to White pregnant individuals, Black pregnant individuals are more likely to be administered a urine test for substance use at delivery and more likely to be reported to child protective services for prenatal substance use despite rates of use similar to those of White people (Jarlenski et al., 2023; Rubin et al., 2022). Additionally, studies have shown that child protective services are more likely to be called for a Black than for a White baby (Harp and Bunting, 2020; Roberts and Nuru-Jeter, 2012). Institutional policy changes can mitigate such racial inequities seen with pregnant patients and provide clinicians with unbiased, standardized screening tools (Habersham et al., 2023; Peterson et al., 2023). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG, 2011) recommends that clinicians work with policy makers to repeal punitive policies on prenatal substance use.

Another consideration is the legally mandated treatment for people who use substances, although not everyone who is arrested for cannabis offenses needs substance use treatment. Mandated treatment is a common feature of juvenile criminal justice diversion programs in the United States, particularly for nonviolent drug offenses. Criminal justice referrals to treatment involving cannabis use disorder have been declining for juveniles, just as for adults, over the past 20 years, even before states legalized cannabis for adult use, presumably as a result of changes in enforcement related to other cannabis policies on medical use and decriminalization (Harris and Kulesza, 2023). Historically, people of color have had less access to treatment through the criminal justice system despite their higher arrest rates, leading to disparities in access to treatment even within the criminal justice system (MacDonald et al., 2014; McElrath et al., 2016; Nicosia et al., 2013). However, a recent study examining the impact of legalization on criminal justice referrals to treatment for cannabis use disorder suggests that access to treatment for juveniles remains high and that previous Black–White disparities may be declining in legalization states. Admission rates for juvenile criminal justice referrals involving cannabis use disorder increased

for Black juveniles 2 and 6 years after a policy change in legalizing states compared with control states (Harris and Kulesza, 2023).

The National Institutes of Health previously funded a large-scale, multisite study—the Juvenile Justice-Translational Research on Interventions for Adolescents in the Legal System (JJ-TRIALS)—which aimed to improve access to services for substance use disorder for justice-involved youth. Although not explicitly focused on cannabis, the JJ-TRIALS framework offers valuable insights for addressing cannabis use among this population (Becan et al., 2020). Previous studies exploring opportunities for engagement with adolescents in the juvenile justice system highlight the potential for diversionary pathways that steer youth away from the criminal justice system and toward treatment and supportive services (Belenko et al., 2017). The Behavioral Health Services Cascade emphasizes the potential transitions youth can navigate across service systems, such as moving from the criminal justice system to the substance use disorder treatment system. It offers a promising framework for addressing cannabis use among justice-involved youth (Belenko et al., 2017).

The impacts of cannabis policy on the quality of health care received, particularly substance use treatment, have received little attention in the literature beyond the issue of how to identify those in need of treatment for cannabis use disorder. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF et al., 2020) concluded that among adults, screening by asking questions about unhealthy drug use has a moderate net benefit when services for accurate diagnosis of unhealthy drug use or drug use disorders, effective treatment, and appropriate care can be offered or referred; in adolescents, the benefits and harms of screening for unhealthy drug use are uncertain.

The USPSTF has not completed a review specific to interventions for cannabis use disorder. While there is an expansive literature identifying psychotherapeutic treatments for cannabis use disorder, including motivational interviewing, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and contingency management, the literature has consistently found these therapies to be only moderately efficacious in reducing use (frequency and amount) and limited in their ability to achieve abstinence (Babor, 2004; Dutra et al., 2008; Sherman and McRae-Clark, 2016). Furthermore, cannabis use disorder may have inequitable treatment outcomes, as inequities in outcomes related to substance use disorder treatment have persisted for decades for many substances (Dogan et al., 2021). However, only a few randomized controlled trials have specifically examined such outcomes among people of color (Jordan et al., 2022), demonstrating a need to evaluate the treatment this population receives. This issue is particularly concerning given the documented associations between racial discrimination and cannabis use, which may also impact treatment initiation as well as treatment-related outcomes.

Legalization has brought opportunities to address issues regarding access to health care for those who use cannabis. Still, the health care system has not fully embraced or changed to accommodate the new health challenges associated with a legal environment. To the extent that the prohibition against cannabis use and the related health and social policies targeting people who use cannabis within the health care system continue to be enforced, the changing cannabis environment may not lead to better health access, particularly for communities of color.

Neighborhood and the Built Environment

The current patchwork of state legalization creates a complex environment for understanding how cannabis policy impacts neighborhoods. Two concepts commonly used to evaluate the impacts of neighborhoods on health and a neighborhood’s health are neighborhood disorder and disadvantage. “Neighborhood disorder” refers to observed or perceived physical and social features of neighborhoods that may signal the breakdown of order and social control and can undermine the quality of life (Sampson and Raudenbush, 1999). In contrast, “neighborhood disadvantage” is described by the socioeconomic conditions within a neighborhood, coupled with the limitations of its connections to external resources and the residents’ social networks (Levy et al., 2020). Studying the impact of cannabis policy on neighborhoods requires a racial lens. Socioeconomic disparities in communities of color were, in large part, created by policies that encouraged segregation (Turner and Greene, 2021). Thus, when interpreting research on neighborhoods and cannabis policy, racism and the resulting economic disadvantage also need to be considered. In many states, for example, local jurisdictions can opt out of retail cannabis sales, which contributes to disparities because the communities with more power and economic stability may be more likely to opt out (Matthay et al., 2023).

Features of the neighborhood context including disadvantage, disorder, and crime are positively correlated with cannabis use and cannabis use disorder (Cao et al., 2020; Furr-Holden et al., 2011; Rhew et al., 2022). Density of cannabis retail outlets may contribute to neighborhood-level crime and disorder, or it may be that outlets are more likely to be located in neighborhoods with more disadvantages, as the communities within them have less power or ability to oppose them (Matthay, 2021; Moiseeva, 2023). The research investigating these relationships has been inconclusive.

There is some evidence that neighborhoods with higher concentrations of poverty, crime, and minoritized populations may contribute to increased rates of cannabis use (Cao et al., 2022; Floyd, 2020). A recent study conducted in Washington state looked at annual cross-sectional surveys on cannabis

use among young adults (aged 18–25) from 2015 to 2019. The study found that, after controlling for individual factors and census tract–level metrics on availability of cannabis in retail outlets, neighborhood disadvantage was statistically significantly associated with increased weekly and near-daily use of cannabis (Rhew et al., 2022). Another study, in California, examined trends in rates of hospital emergency department visits and discharges involving cannabis use disorder at the community level from 2010 to 2019 and found greater increases in both outcomes in communities of color (Cao et al., 2022).

Evidence on cannabis policies contributing to neighborhood crime is mixed, which may be due to differences in the measurement of neighborhoods and in the types of crimes examined. A study in Denver, Colorado, found that the opening of a cannabis retail outlet was associated with higher rates of all types of crime, except for murder and car theft, in surrounding neighborhoods (Hughes et al., 2020). Another study, in Seattle, Bellevue, and Tacoma (all in Washington state), found modest but statistically significant increases in property crime in census block groups containing new cannabis retail outlets (Thacker et al., 2021). However, other studies have found a decrease in violent crime, including rapes and property crime, in Washington and Oregon with the opening of retail outlets (Dragone et al., 2019). Even when cannabis retail outlets are associated with crime (whether positively or negatively), it is unclear to what extent these associations are due to the current rules placed on cannabis outlets because of federal prohibition. Specifically, cannabis retail stores are mainly cash businesses, which are often the target of crime. This is why retail stores often have tight security systems with cameras, which may lead to lower crime in their vicinity (Chang and Jacobson, 2017).

Because of zoning laws or by choice, cannabis retailers may be concentrated in neighborhoods with historical disadvantages, which raises questions about whether the presence of an outlet creates a disadvantage, or these outlets are more likely to exist in disadvantaged neighborhoods. For example, one study examining neighborhood characteristics associated with density of cannabis retailers in Oklahoma documented a disproportionate concentration of retailers in census tracts with a larger proportion of individuals lacking health insurance and living below the federal poverty level (Cohn et al., 2023). Importantly, this same study found that a large proportion of census tracts classified as rural had at least one retailer, which may have implications for geographic differences in access to cannabis. A similar study in Washington state indicated that cannabis retailers are disproportionately located in communities with more significant disadvantages, as defined by American Community Survey composite scores (Williams et al., 2023). A study of both licensed and unlicensed cannabis retailers in California in 2018 found that not only were legally licensed retailers more likely to be found in neighborhoods

with higher poverty and in communities of color, but so, too, were unlicensed stores (Unger et al., 2020).

Retail availability of cannabis has been associated with greater cannabis use and cannabis-related health outcomes, although more research in this area is needed. Greater retail availability of cannabis has been associated with lower odds of perceiving cannabis smoking as harmful. A study in California found that having an adult-use cannabis retailer within 2 miles of a person’s home and signs promoting the health benefits of cannabis were associated with both increased use and lower perceived risk among adults (Han and Shi, 2023). Another study, in rural Oklahoma, found that the presence of cannabis retailers increased exposure to cannabis-related advertising among adolescents (Livingston et al., 2023). Retail availability of cannabis has also been associated with greater odds of prenatal cannabis use among pregnant individuals in California (Young-Wolff et al., 2021).

A recent systematic review of the density of cannabis retailers (Cantor et al., 2024) found consistent positive associations between greater access to cannabis retailers across several outcomes. Greater use of health care services and increased poison control calls directly due to cannabis were observed in 10 of 12 included studies (83 percent). Increased cannabis use and cannabis-related hospitalizations during pregnancy were observed in 4 of 4 included studies (100 percent). Frequent cannabis use in adults and young adults was observed in 7 of 11 included studies (64 percent). There are no consistent associations between greater cannabis retail density and increased frequent cannabis use in adolescents (25 percent of included studies), use of health care services potentially related to cannabis (33 percent of included studies), or increased adverse neonatal birth outcomes (26.8 percent of included studies) (Cantor et al., 2024).

Social and Community Context

Cannabis policy may play a role in weaving the fabric of a community. This social fabric is built on strong social networks, a sense of collective efficacy (the ability to work together), and a focus on neighborhood safety (Barnett and Casper, 2001; Halliday et al., 2020). However, unequal enforcement of cannabis prohibition may have eroded trust, particularly within minoritized communities. Cannabis legalization may change that, but the committee’s analysis of arrest data shows that disparities in arrest rates persist.

Beyond policy changes, social factors within communities also significantly influence substance use patterns. Concepts such as collective efficacy and social cohesion, which measure the strength of relationships and community bonds, are crucial for understanding this dynamic. Communities with low collective efficacy, often facing economic hardship, may struggle to enforce social norms (Kawachi and Berkman, 2000; Sampson, 2017).

Low collective efficacy could lead to less intervention in risky adolescent behavior, potentially increasing youth substance use. Studies support this link, showing a correlation between lower parental oversight and higher youth cannabis use (Handley et al., 2015). However, the relationship between social factors and substance use is complex. Strong communities with high adult involvement can also lead to lower youth substance use (Kawachi and Berkman, 2000). There is, however, a potential downside: strong social ties may normalize substance use if adults themselves partake (Fagan et al., 2015; Mayberry et al., 2009). Additionally, parents in neighborhoods with high collective efficacy may feel less pressure to supervise their children directly, assuming that the community shares that responsibility. This assumption can have unintended consequences.

The impact of changes in cannabis policy on these social processes remains unclear. While research on other substances, such as alcohol, offers some insights, the specific effects of cannabis policy within the context of a community’s social fabric require further exploration.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Cannabis policy has considerable impacts on health equity. Cannabis arrests and incarceration have contributed to substantial social and economic inequities due to the arrest, fines, loss of income, and collateral consequences. Those arrested face restrictions in voting, employment, housing, public assistance, immigration, family integration, and education.

Conclusion 5-1: Cannabis prohibition and traditional law enforcement tools (arrest and prosecution) have disproportionately impacted communities of color, leading to adverse collateral consequences that negatively affect people’s lives in such areas as education, employment, and health care access. While policy reforms have decreased arrest rates, evidence suggests that racial inequities may persist, highlighting the need for further action to address these inequities.

The data needed to evaluate whether changes in cannabis policy have reduced inequities associated with criminal justice entanglement are lacking. To evaluate the impact of cannabis policy changes on social and health equity, it is crucial to understand who is being arrested, for what, and with what consequences. National crime data do not adequately capture demographic characteristics (e.g., race, ethnicity, income). Prior reports of the National Academies have documented problems with crime statistics and the data infrastructure supporting those systems (Box 5-1). The recommendations from those reports highlight the need for better and more accurate data, which would allow for improved monitoring of how changes in cannabis policies are affecting inequities in criminal justice.

BOX 5-1

Selected Conclusions and Recommendations from Prior National Academies Reports on Crime Statistics

Toward a 21st Century National Data Infrastructure: Enhancing Survey Programs by Using Multiple Data Sources, 2023

Conclusion 7-1: The National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) provides details about each crime incident that were not available in the previous Summary Reporting System of the Uniform Crime Reports. NIBRS represents an important step in producing detailed and accurate crime statistics. However, the transition to NIBRS is still underway, and variations in measurement and data reporting across jurisdictions need further study (NASEM, 2023b, p. 151).

Modernizing Crime Statistics: Report 2—New Systems for Measuring Crime, 2018

Conclusion 2-1: The aim of modern crime statistics is the effective measurement and estimation of crime. Accurate counting of offenses and incidents is important, but the nation’s crime statistics will remain inadequate unless they expand to include more than just simple tallies with no associated measure of uncertainty or capacity for disaggregation. Through the collection of associated attribute data, the suggested crime statistics should—at minimum—enable the analysis of data in proper geographic, demographic, sociological, and economic context, and provide the raw material for important measures related to an offense (such as the harm it causes) in addition to its count (NASEM, 2018, p. 32).

Conclusion 3-1: A stronger federal coordination role is needed in the production of the nation’s crime statistics: providing resources for information systems development, working with software providers to implement standards, and shifting some burden of data standardization from respondents to the state and federal levels. The goal of this stronger role is to make crime data collection a product of routine operations (NASEM, 2018, p. 53).

Recommendation 3.1: The U.S. Office of Management and Budget should explore the range of coordination and governance processes for the complete U.S. crime statistics enterprise—including the “new” crime categories—and then establish such a structure. The structure must ensure that all of the component functions of generating crime statistics are conducted in concordance with the sensibilities, principles, and practices of a statistical agency. It should provide for user and stakeholder involvement in the process of refining and updating the underlying classification of crime. The new governance process also needs to take responsibility for the dissemination of data products, including the production of a new form of Crime in the United States that includes the “new” crime categories (NASEM, 2018, p. 61).

The Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program tracks reported crimes and interactions with law enforcement, such as arrests. Law enforcement jurisdictions across the United States voluntarily submit data to the UCR through a summary reporting system, which is then forwarded to the FBI. In 2021, the UCR began requiring jurisdictions to switch to the National Incident-Based Reporting System, which improved standardization in the data submitted to the UCR, although problems remain. The UCR’s voluntary nature leads to inconsistent data collection and reporting. For example, some locations require every law enforcement agency to submit data, while in others, fewer than 3 percent of agencies submit data voluntarily (NASEM, 2023b). Ensuring the quality and accuracy of the data is also challenging, as year-to-year changes could be due to improved data collection or changes in reporting. As of October 2022, evaluating the quality of the national estimates was impossible, as only some of the estimation procedures had been made public (NASEM, 2023b).

In addition to the lack of data on sentencing, data on crime are lacking through the other stages of the criminal justice system. There is relatively little state-by-state data and no national data providing a detailed accounting of how many persons are convicted of cannabis-related offenses or showing just who is sentenced to imprisonment and community supervision or for how long. Moreover, individuals on probation and parole often are subject to drug testing regardless of conviction offenses, and a positive test for cannabis can lead to probation sanctions, technical violations, and revocations, which may result in a period of incarceration. Data are also scarce on how past cannabis arrests or convictions may impact future criminal justice involvement. However, the U.S. Sentencing Commission recently determined that nearly 10 percent of offenders sentenced in federal courts in a year were subject to an aggravated sentencing range based on prior cannabis possession convictions (Kachnowski et al., 2023). The improved data could be used to evaluate the impact of cannabis policies on criminal justice inequities and could be used to inform improved cannabis policy enforcement.

Recommendation 5-1: Jurisdictions responsible for the enforcement of cannabis laws should endeavor to regularly gather and report detailed data concerning the use of criminal enforcement tools to enforce cannabis policies. These tools include:

- arrests,

- sentences,

- incarceration (pre- and postadjudication), and

- diversion programs (e.g., drug courts, law enforcement–assisted diversion, treatment programs).

These data should be available to the public and should include details about the specific cannabis violation (e.g., impaired driving, illicit trafficking, distribution to minors, possession, possession with intent to distribute, probation or parole violation) and the demographics of those in contact with law enforcement (e.g., race, sex, age, criminal history).

Many states that have legalized cannabis have developed state social equity programs that focus on three key areas: criminal justice reform, support for industry participation, and reinvestment in disproportionately affected communities. While these initiatives have the potential to heal the wounds of prohibition, challenges persist in implementing them and ensuring their success. As these programs evolve, continuous monitoring and adjustments are essential to maximize their effectiveness (Title, 2021). It is also essential that the impacted communities be consulted on the policy decisions that impact them. Community engagement, belonging, and civic engagement are vital for individual and community health, especially with respect to racial and ethnic equity, highlighting the need to create space for everyone and build the ability to work together. Robust institutions, participation opportunities, and freedom from discrimination are key. Feeling connected and contributing actively are essential for belonging. These elements create a foundation for a healthy and thriving society (NASEM, 2023a).

Recommendation 5-2: State cannabis regulators should systematically evaluate and, if necessary, revise their cannabis social equity policies to ensure that they meet their stated goals and minimize any unintended consequences. Policy makers should meaningfully engage affected community members when developing or revising these policies.

Record clearing is a critical social equity provision for people with criminal records. Clearing records can improve both employment and social outcomes (Wakefield et al., 2023). Government-initiated or automatic record relief is much more effective than petition-based relief. Additionally, record expungement has not harmed the community (Berman, 2018).

Conclusion 5-2: In states that have implemented record relief provisions for cannabis offenses, automatic or government-initiated relief is more effective than petition-based relief.

Recommendation 5-3: Where states have legalized or decriminalized adult use and sales of cannabis, criminal justice reforms should be implemented, and records automatically expunged or sealed for low-level cannabis-related offenses.

Despite recent attempts to protect employee rights within the context of the changing legal cannabis policy landscape, only about one-third of states with legalized adult-use cannabis have included any consideration of employee protections at the point of hire or for off-duty activities in their state cannabis statutes. Cannabis-related statutes that outline employee protections regarding cannabis use while off duty and include language clearly citing specific industry exceptions (e.g., health care, construction) and defining intoxication and impairment could lend clarity to employee drug testing. Under the Drug-Free Workplace Act (41 USC 81, 1988), employees must undergo drug testing in specific circumstances, if, for example, they work in the safety and security professions, although the testing is not always applied equitably (Hoffman, 1999; Oh et al., 2023). Until better THC detection tools are developed that can determine current intoxication or impairment, inequities could be reinforced by employer drug testing. Notably, a positive THC test result does not necessarily indicate current or even recent (within the past 24-48 hours) intoxication or impairment (Vandrey et al., 2017).

Conclusion 5-3: Employer drug testing has been applied inequitably and could impair access to employment, particularly in communities of color. Many employers are required to test employees for drug use under the Drug-Free Workplace Act, but many are not. Two-thirds of states where cannabis is legal for adult use have laws protecting employees’ right to use cannabis while off duty.

The committee’s analysis of the impact of cannabis policy on social determinants of health revealed important findings related to neighborhoods and health care. While some concerns exist regarding a potential link between cannabis retail outlets and increased neighborhood disorder or crime, particularly in disadvantaged communities, disentangling these effects from preexisting neighborhood characteristics remains challenging. This complexity is further highlighted by the observation that cannabis retailers are more likely to be concentrated in areas with higher poverty rates and/or higher proportions of people of color. Studies in Oklahoma, Washington, and California show that cannabis retailers are more concentrated in disadvantaged neighborhoods, raising concerns about equitable access and potential negative impacts on these communities (Cohn et al., 2023; Unger et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2023). This spatial clustering also raises concerns about potential health inequities, as research suggests that increased retail access to cannabis is associated with adverse health outcomes (Cantor et al., 2024). These findings highlight the need for further investigation into the social and health consequences of retail access to cannabis, particularly within disadvantaged communities.

Conclusion 5-4: Retail access to cannabis is often concentrated in neighborhoods with historical disadvantages. Increased retail access to cannabis is associated with increases in (1) demand for health care services, (2) poison control calls directly due to cannabis, (3) cannabis use and cannabis-related hospitalization during pregnancy, and (4) cannabis use in adults and young adults.

Assessing health care access also proved challenging for the committee. Cannabis legalization could have a positive impact on health care access by reducing the stigma associated with use. However, draconian policies that associate cannabis use during pregnancy with child abuse still exist even though medical societies such as ACOG do not support them. State-level policies that treat prenatal substance use as child abuse have health implications. The fear of punishment or losing custody of their child can cause significant stress for pregnant people struggling with substance use, leading to continued use and related harms to the developing baby (Atkins and Durrance, 2020; Carroll et al., 2021; Chang et al., 2019; Faherty et al., 2019; Meinhofer et al., 2022).

Conclusion 5-5: Drug testing in pregnancy is applied inequitably, particularly to people of color, and may deter those who use cannabis from seeking prenatal care. People who are pregnant and are using cannabis will benefit from clinical and social support; education about fetal risk; and referral to nonjudgmental, evidence-based interventions or specialty treatment, as needed, rather than being arrested or reported to child protective services.

REFERENCES

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics) and Committee on School Health. 2003. Out-of-school suspension and expulsion. Pediatrics 112(5):1206–1209.

ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). 2011. Substance abuse reporting and pregnancy: The role of the obstetrician–gynecologist. ACOG committee opinion 473.

APA (American Psychological Association) Zero Tolerance Task Force. 2008. Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools? An evidentiary review and recommendations. The American Psychologist 63(9):852–862.

APIS (Alcohol Policy Information System). 2023. Health care services and financing: Health insurance: Losses due to intoxication (“UPPL”). https://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/apis-policy-topics/health-insurance-losses-due-to-intoxication-uppl/16/maps-and-charts (accessed May 2, 2024).

Atkins, D. N., and C. P. Durrance. 2020. State policies that treat prenatal substance use as child abuse or neglect fail to achieve their intended goals. Health Affairs 39(5):756–763.

Azagba, S., Ebling, T., Shan, Y., Hall, M., Wolfson, M. 2024. Treatment referrals post-prohibition of alcohol exclusion laws: Evidence from Colorado and Illinois. Journal of General Internal Medicine 1–8.

Babor, T. F. 2004. Brief treatments for cannabis dependence: Findings from a randomized multisite trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 72(3):455.