Mitigating Arboviral Threat and Strengthening Public Health Preparedness: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 5 Lessons Learned from Previous Outbreaks

5

Lessons Learned from Previous Outbreaks

Highlights

- It is vital to maintain diagnostic capacity to be ready to deal with outbreaks as soon as they occur instead of having to take time to build up that capacity. (Staples)

- Maintaining an awareness and surveillance infrastructure is important for arbovirus detection, monitoring, and control efforts. Challenges in the United States include a decline in the number of state entomologists over the years. (Staples)

- It is crucial to continue to work on knowledge gaps in between outbreaks to be more prepared to deal with future ones. (Staples)

- New approaches to regulation are needed for dealing with outbreaks, as the current regulatory approach significantly increases response times. (Staples)

- Various drivers will push the emergence of viral and arbovirus infections in the coming years, including urbanization, deforestation, animal and human migrations, poverty, political instability, and climate change. (Hotez)

- Chronic noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes and hypertension will play a role in future arbovirus outbreaks. (Hotez)

- Fragmentation in health care systems will limit the effectiveness of response to future arbovirus outbreaks. (Hotez)

- It is important to pay attention to vaccines and other technologies that can be developed and used locally in low- and middle-income countries. (Hotez)

- Anti-vaccine and anti-science attitudes in the public will make it more difficult to deploy some of the advanced vaccines and technologies being developed to address arbovirus diseases. (Hotez)

NOTE: These points were made by the individual workshop speakers/participants identified above. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Each viral outbreak can offer an opportunity to learn how to respond better to future outbreaks. As forum vice chair and session moderator Kent E. Kester explained, the workshop’s fourth session was devoted to hearing about lessons that have been learned from previous outbreaks in order to help shape preparedness and response efforts for future arboviral outbreaks.

The session panel had two speakers. The first was Erin Staples, a medical epidemiologist in the Arboviral Diseases Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), who spoke about lessons learned from previous arboviral outbreaks. The second was Peter Hotez, the dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine and a professor of pediatrics and molecular virology at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Hotez spoke about lessons from dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic that can be applied to arboviruses. A question-and-answer period followed their presentations.

PREVIOUS ARBOVIRAL OUTBREAKS

Staples began by listing more than two dozen arboviral outbreaks and emergence events from the past 20 years. There were multiple outbreaks of chikungunya, West Nile virus, yellow fever, and Zika as well as so many dengue outbreaks that she did not even list them individually. Less common outbreaks and emergence events included eastern equine encephalitis, western equine encephalitis, Japanese encephalitis, Bourbon virus, Heartland virus, and severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Staples was involved in the response to more than a dozen of those, she said, and her talk focused on four specific lessons she learned from those experiences.

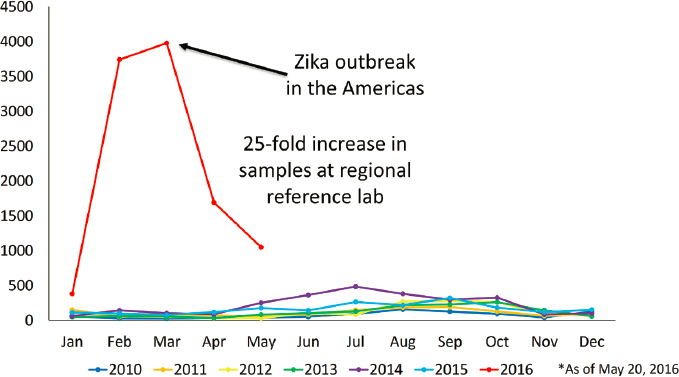

The first lesson was the importance of ensuring diagnostic capacity. There is always normal seasonal variation in the number of diagnostic samples the CDC receives at its Arboviral Diseases Laboratory, but when

an outbreak begins, the numbers can dramatically increase. The 2014 chikungunya outbreak in the Americas, for instance, led to a threefold increase in the number of samples the CDC received; the agency was able to handle that jump in testing with relative ease because it had prepared reagents ahead of time that it could send out to state health departments and increase testing capacity. A more severe challenge came with the 2016 Zika outbreak, Staples said, when “all of a sudden, instead of getting 150 samples a month to test with our limited staff, we had over 4,000 samples pouring into our laboratory” (Figure 5-1). That forced the agency to call in additional resources. “Our bacterial diseases lab became an arboviral lab,” she said. “The Atlanta labs became arboviral labs.” But again, because of the stocks of reagents and the ability to bring in extra testing capacity, the CDC was able to respond to the surge in demand.

These experiences showed, Staples said, the importance of maintaining a surge capacity for arboviral disease testing; that surge capacity depends on having adequate stores of reagents and control materials, establishing sample-sharing policies, and maintaining common testing platforms. One issue that needs to be addressed, Staples said, is the role of laboratory-developed tests in a public health response. If a new arbovirus appears for which there are no existing tests, laboratory-developed tests will be important in the response. However, she added that regulatory requirements would pose an additional obstacle in a public health response.

A second lesson, Staples said, is the importance of maintaining global awareness for arboviral diseases as well as the infrastructure necessary to

SOURCES: Presented by Erin Staples on December 12, 2023; CDC, 2023.

monitor them. As an example, she pointed to the experience with Zika. The measured numbers of Zika cases peaked in 2016, but the numbers of cases of microcephaly associated with the Zika virus peaked in late 2015 or early 2016, and the infections leading to those cases would have occurred in 2015. Thus, she said, “we probably had just as many if not more infections in 2015 due to Zika virus, but we just didn’t know about it. We weren’t aware, we weren’t looking for it.”

One current stumbling block to maintaining awareness for arboviral diseases in the United States, Staples suggested, is the lack of emphasis placed on such awareness by the states. In 1927, every state had a state entomologist because of efforts to eradicate malaria, but in 2022 there were only 16 state entomologists. Similarly, in 2022 there was very spotty surveillance and reporting of the West Nile virus in mosquitoes—and the areas without state entomologists were much less likely to be carrying out such surveillance. “Awareness and surveillance infrastructures are very important for detecting and monitoring and control efforts,” she said, and the United States does not have a comprehensive system of monitoring for nonhuman disease vectors.

In short, Staples concluded, maintaining surveillance infrastructure is important for detection, monitoring, and control efforts and could be accomplished by maintaining arboviral expertise at the state level. Optimally, arboviral surveillance could include human, vector, and animal components, as applicable. For instance, observing deaths in nonhuman primates can provide a warning signal of an impending outbreak of yellow fever in South America. Unfortunately, she continued, most areas of the world lack adequate vector surveillance. Furthermore, the integration of animal data with other surveillance data is a significant challenge.

The third lesson, Staples said, is that it is important to continue to address knowledge gaps. As an example, she showed a graph of the last 50 years of Zika virus publications. There were very few for most of that time, then the numbers grew quickly after the outbreak and peaked at about 2,000 publications during the year after the outbreak but then dropped sharply; in 2023 there were only half the number of publications as in 2016. Furthermore, the number of publications on Zika in 2023 were just a little more than 1 percent of the number of publications on coronavirus. In short, she said, “we haven’t done a great job . . . of addressing the gaps that remained at the end of the [Zika] outbreak.”

Continuing, Staples identified five specific knowledge gaps that remain after the Zika outbreak in the Americas. First is the potential for nonhuman circulation of the virus and its endemicity. Second is the identification of the optimal diagnostic testing for congenital Zika virus syndrome. Another knowledge gap exists around potential antibody-dependent enhancement of Zika virus infections with dengue virus infections. Fourth, if a vaccine is

developed, which epitopes are most important for vaccine neutralization, and what can be done to decrease the cross-reactivity that could occur? Finally, what can be learned about time intervals between outbreaks and when should the system be prepared for the next outbreak? “I don’t have an answer for that right now,” she said.

Addressing these knowledge gaps is complicated by a lack of sustained funding and competing public health priorities, Staples said. “We just don’t have adequate resources.” In the future, it may be important to have existing protocols and networks readily available to address the knowledge gaps. Staples illustrated that “by the time we implemented the network for pregnant women to look at the impacts of Zika, the outbreak was almost over, and we weren’t able to generate enough data.” So, protocols should be established prior to outbreaks to allow them to be quickly implemented as part of the response efforts. She also noted that improving partnerships among industry, academia, and government will be an important step in overcoming these challenges and effectively addressing the gaps in knowledge about Zika and other arboviral diseases.

The fourth lesson that Staples offered was the importance of considering alternative agreements and regulatory needs. A response to an arboviral outbreak requires many different components, such as surveillance, laboratory testing, vector control, medical countermeasures, and community engagement, and each of these components requires its own infrastructure. But there are various hurdles that arise in these different areas that can slow a response, particularly hurdles related to regulatory approval pathways. Product approval is an area where slowdowns can occur, but there are many others, such as the need for approval from an institutional review board for testing on human subjects or resistance to the use of insecticides. “All of those things take time,” Staples said. “The existing mechanisms really are not great, and because we always hit those roadblocks, we need to think about how to overcome some of these issues that we face.” Increasing regulatory requirements are there for a good reason, she said, but they are affecting readiness and may need to be modified in the case of urgent public health responses.

In closing, Staples offered some suggestions for how to be prepared to respond to the next arboviral disease outbreak. First, she said, “We have to expect the unexpected. We didn’t expect Zika virus was going to cause microcephaly.” Second, it will be important to define likely hotspots for emergence and target them for surveillance. Third, regulatory pathways should be developed for preapproving common arboviral test platforms such as the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), so that they can be put to work quickly in an outbreak. “If we had approval of these test platforms, we could swap out our antigens, we could swap out our reagents, and we could be more versatile to potentially have early detection

but also early response,” she said. Fourth, it is important to foster more open regulatory discussions for countermeasures to allow obstacles to be addressed proactively.

Staples noted that another important step will be to advance considerations for alternative mosquito control techniques against multiple mosquito species. No single technique is going to work against all the types of mosquitoes, she said. Finally, she concluded, there needs to be increased coordination between public and private entities and their overlapping efforts. Different entities have developed dengue vaccines that are most effective against different strains, Staples said. It would make sense to combine the work to find a marker that would provide effective cross-protective immunity against all strains, she said. “We need to work together.”

COVID-19

Hotez began by saying that although he is not an arbovirologist, he has learned about arboviruses by working on the Gulf Coast for the past 12 years and going through Zika and dengue outbreaks. His remarks centered around five lessons learned from working with COVID-19 that could be applied to dealing with arboviruses.

The first lesson, Hotez said, is that there are a number of key twenty-first century drivers leading to the emergence of viral infections, including arbovirus infections. In his book Preventing the Next Pandemic: Vaccine Diplomacy in a Time of Anti-Science (2021), Hotez examined how poverty, war, political instability, urbanization, deforestation, human and animal migrations, and climate change are combining in unique and interesting ways to increase the risk of pandemics. For instance, as more of the world’s population is moving to urban areas, a new generation of megacities is appearing in higher-, middle-, and lower-income countries simultaneously. Unfortunately, many of these megacities are sweltering, with their average temperatures being steadily increased by global warning, which creates more hospitable environments for Aedes mosquitoes, especially Aedes aegypti. The widespread poverty that is found in many of these megacities also plays a role in the risk of arbovirus emergence and spread, as does political instability and increasing deforestation.

Many of the world’s hotspots where sharp increases in disease can be observed—places like the Arabian Peninsula, parts of Africa, parts of central Latin America, and Texas and the Gulf Coast—are places where there is a combination of urbanization, climate change and deforestation, political instability, and other twenty-first century forces. A good illustration of these forces in practice, Hotez said, is what has been happening on the Arabian Peninsula since the 2010s. The ISIS occupation of parts of Syria and Iraq and the civil war in Yemen forced people to crowd into

cities, and then an explosion in sand fly populations led to hyper-endemic leishmaniasis. There were also dengue outbreaks. Unprecedented temperatures of 50°C or more forced people to abandon agricultural pursuits along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and flee into Aleppo and Damascus, which fueled exposure to vectors and vector-borne illnesses, and the situation was exacerbated by a halting of vaccination programs. “So, the Middle East was a good crucible of all of those forces together,” Hotez said, “and you had the largest cholera outbreak that the world had seen in some time in Yemen because of that.”

Something similar happened in central Latin America following the socioeconomic collapse of the Maduro regime in Venezuela. Vector-control programs and immunization programs were discontinued, and unemployed people sought employment in the illegal gold mining industry and ended up sleeping outdoors without mosquito nets. “So, you saw this massive rise in malaria cases as well as dengue and others,” Hotez said. And even along the American Gulf Coast there are predictions that warming temperatures will lead to rising numbers of Aedes mosquitoes and then to increasing numbers of cases of dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus infections (Hotez et al., 2014).

Unfortunately, he continued, there has been little attention paid to the looming risk of arboviruses in that area, so he and a colleague published an article in the New England Journal of Medicine calling attention to the vulnerability to these diseases along the Gulf Coast (Hotez and LaBeaud, 2023). “I think this discussion is important to elevate arboviruses to the same attention of the policy makers that they have for some of the catastrophic respiratory illnesses,” he said.

The risk along the Gulf Coast is due to a combination of factors—not just climate change but also human migration, aggressive urbanization, and poverty. The reason poverty is so important, Hotez explained, is that poorer people are more likely to live in dilapidated homes with no window screens and an absence of air conditioning, which means they keep their windows open when it is hot. This is combined with the fact that many people in low-income neighborhoods dump their tires, which hold water and serve as breeding grounds for mosquitoes. “We do have Aedes aegypti mosquitoes here in Houston,” he said, “and that’s important.”

As an aside, Hotez noted that he has been working with Senator Cory Booker (Dem.-NJ) on legislation called STOP: Study, Treat, Observe and Prevent Neglected Diseases,1 which is designed to raise awareness of the importance of doing better surveillance for arboviruses and neglected tropical diseases on the Gulf Coast and in the southern United States.

___________________

1 STOP Neglected Diseases of Poverty Act, S. 324, 118th Congress, 1st sess., Congressional Record 169, no. 27, daily ed. (February 9, 2023).

A second lesson to be learned from COVID-19, Hotez said, is the role played by chronic underlying noncommunicable diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. The rates of these diseases are climbing not only in the United States but also globally. Diabetes is hitting both the African continent and India very hard, for instance. The COVID-19 pandemic showed how important diabetes and hypertension were as risk factors for that disease, but the literature shows that they are also important risk factors for dengue (Mehta and Hotez, 2016).

Conversely, the viruses themselves have chronic and persistent effects. The existence of long COVID is well known, but influenza and other viruses produce long-term, chronic, and debilitating effects as well. This has been demonstrated for West Nile virus, he said, and it may be true for other arboviruses as well (Garcia et al., 2015).

A third factor shown to be important with COVID-19, and likely to be important for arboviral diseases, is the fragmentation of the country’s health systems, Hotez said, especially for arbovirus control. “Here in Harris County and Houston, Texas, we have two health departments, both the city and the county, and a very well-run mosquito control division,” he said. “They do surveillance, they’re doing PCR (polymerase chain reaction), they’re monitoring for viruses.” But the problem, he continued, is that other Texas counties, particularly some of the more rural or less wealthy counties, do not have such well-run monitoring and control programs. Addressing the variability between counties in terms of mosquito and virus surveillance and control is going to be very important, he said.

A fourth lesson is the importance of remembering the needs of lower- and middle-income countries when developing vaccines and other technologies to deal with arboviruses. In the case of COVID-19, Hotez said, in 2021 much of the African continent and the Indian subcontinent lagged far behind the rest of the world in vaccination rates, “in part because there was so much emphasis on speed and innovation and cool technologies like messenger RNA (mRNA) and particle vaccines.” Perhaps vaccine distribution may have been more globally equitable if older technologies had been available to manufacture locally.

To address this issue, a group of vaccine producers in low- and middle-income countries organized the Developing Country Vaccine Manufacturers Network and have developed and provided vaccines for such diseases as hepatitis B (Hayman and Pagliusi, 2020). “The point is, yes, we want cutting edge technologies but also to figure out a way to be compatible with the vaccine producers in the low- and middle-income countries,” Hotez said. “You don’t have to be a big pharma company to still do big things, and looking at models that go beyond the big pharma companies could be extremely helpful.”

Finally, Hotez said, “I think we should not underestimate the impact of the anti-vaccine movement.” Some 200,000 Americans needlessly died because they refused the COVID-19 vaccine, he said, and the anti-vaccine movement is not stopping at COVID-19 but extending into childhood immunizations as well (Hotez, 2023). Furthermore, it is globalizing. It has moved into Canada and Europe and even Latin America. Although there are exciting new vaccines becoming available for arboviruses, such as a chikungunya vaccine and a couple of dengue vaccines, it is not clear how well they will be accepted. A particular concern is the yellow fever vaccine, which has rare but serious side effects. Additionally, the anti-science movement does not threaten only vaccines. Such interventions as the Wolbachia bacteria and genetically modified mosquitoes may also meet resistance. “I think there’s going to be a big barrier that we are not really addressing,” Hotez said.

Summarizing, Hotez said that he believes there is an arbovirus tsunami coming, and the public health field is not ready. “We are not ready because of this new paradigm of hot and sweltering megacities with climate change, urbanization, urban poverty. We are not ready because of the unprecedented levels of diabetes and hypertension which is going to increase the severity of arbovirus infections. We still have a fragmented health system.” Furthermore, he concluded, not enough attention is being paid to accelerating technologies locally in low- and middle-income countries or to the way that anti-science could slow the uptake of new vector control technologies, vaccines, medicines, and diagnostics.

DISCUSSION

Rebecca Gustafson from Louisiana State University began the discussion session with a question about raising awareness concerning the risks that poor populations face from arboviral diseases as well as the elevated risks that arise in the wake of various disasters, such as hurricanes. Hotez responded by noting that the poor are more susceptible to the effects of catastrophic weather events because they tend to live in weather- and climate-vulnerable areas where people with means do not want to live, such as the low-lying areas around New Orleans that were most affected by Hurricane Katrina. Second, people living in low-income neighborhoods are likely to be more susceptible to mosquito-borne illnesses because there are likely to be more places for mosquitoes to breed, such as in discarded tires for Aedes aegypti mosquitoes or drainage ditches for Culex mosquitoes. A third factor, Hotez said, is that many policy makers do not understand that disease transmission occurs in the United States. One of the reasons Hotez cited as why he started working with Senator Booker is to raise awareness of the risks created by the combination of warming temperatures, altered

rainfall patterns, urbanization, and extreme poverty. But, he continued, getting those messages out has been “extremely tough and challenging.”

Kester then asked both panelists what it would take to increase public and private investment in the prevention of arboviral disease. Staples said that one approach is to talk about it in cost–benefit terms—for instance, what 5 million cases of dengue a year cost society and what it would cost to take some simple preventive measures. “A can of spray foam to plug up holes in a tree [to control La Crosse virus vectors] is $10,” she said. “You could buy a lot of spray foam and prevent a lot of disease burden and costs in a very simple way.”

Hotez agreed and added that both the United States and the G20 countries have committed to funding programs for pandemic preparedness. The problem, though, is that people are thinking mainly about respiratory viruses like SARS-CoV-2 or sometimes the filoviruses, such as Ebola, which cause severe hemorrhagic fever. “The key is getting a seat at the table for the arboviruses, getting people to understand that these are every bit as important and every bit a threat as anything else,” he said, “and recognize there are some unique aspects for arboviruses that would not be covered in general use funds for respiratory viruses.”

Kester then asked Hotez to comment on the current push to develop mRNA vaccines in the wake of their success against COVID-19, particularly since there is no guarantee that they will be as successful against other types of diseases. “I think everyone is running to the mRNA basket, and I think that’s a mistake,” Hotez replied. While mRNA is certainly a promising technology, he said, it is not necessarily the best technology for vaccines against all the different pathogens. More importantly, it is wise to have multiple options for when a new epidemic occurs because it is never clear in advance which will prove to be the most effective for the disease and context of the outbreak. “We should be getting as many technologies in play as possible” to prepare for future arbovirus outbreaks, he said.

Another problem to consider, Hotez said, is how to make sure that low- and middle-income countries can quickly access the vaccines they need in an outbreak. One approach is simply building up the vaccine-manufacturing infrastructure and capacity in those countries. Another issue that needs to be addressed is regulation. “We had this problem where everything had to go through the WHO [World Health Organization] prequalification mechanism, and they wound up sitting on a lot of technologies coming out of the developing country vaccine producers and putting a velvet rope around the big pharma companies.” As a result, low- and middle-income countries ended up relying on vaccine makers in the United States, Europe, and Japan and had to wait in line.

In response to another question, Hotez suggested that the current focus on climate change could be used to help get more attention paid to arbovi-

rus prevention. “Let’s make the case that the reason why arboviruses have to have a seat at the pandemic preparedness table is because these are the viruses of climate change.”

Responding to a comment about the lack of interest in developing a Zika vaccine once the Zika outbreak was contained, Hotez suggested that it might make sense to move toward developing a pan-arbovirus vaccine that would be effective against many different viruses. For instance, he continued, when the drug representatives for Merck speak about their tetravalent dengue vaccine, which can handle all four versions of dengue, he wonders, “why aren’t we making this a pentavalent vaccine and adding a component for Zika, or a hexavalent vaccine and adding in chikungunya, or even heptavalent with West Nile?” Currently people are not thinking in those terms, he said, but there should be an effort to “lift all boats simultaneously” by targeting not only dengue for vaccination but also other arboviruses.

Following a question about equity, both Staples and Hotez agreed that it will be important to work for greater equity in the prevention and control of arboviruses, but they also agreed that it is a challenging issue. “I think we need to advocate . . . in general for arboviruses,” Staples said, “because no matter where you go in the world, other than maybe Antarctica, you will have an arbovirus that is going to be impacting someone. . . . Talk globally, and advocate for all of our viruses together because that way we are going to make sure we engage the right people.”

Hotez agreed, saying that the equity lens can be powerful, but it is not easy to work with. He spoke of a time after he had a great success working with the U.S. Congress on packages of mass treatment for neglected tropical diseases such as intestinal worms, schistosomiasis, and river blindness, and then he returned to the same people to talk about neglected tropical diseases in the United States, including arboviruses. Hotez said that their response was “Yeah, Peter, but before you were talking about a simple package of pills. Now you’re telling us we have to go into infected communities, we’ve got to do surveillance, there are issues around quality housing, doing cleanup of low-income neighborhoods, preventive measures. This is messy, Peter.” So, he concluded, moving forward on measures to prevent arboviruses can be a tough sell.

One participant asked the panelists to comment on the role that health care systems play in the effort to protect against arboviruses. Hotez described a study by Murray et al. (2013) looking at patients presenting to Houston area hospitals in 2003–2005, which found that there had been a cluster of dengue cases coming into Houston-area emergency rooms—and probably locally transmitted dengue between 2003 and 2005—but that almost none of those cases, including one that resulted in death, were diagnosed at the time. Part of the reason, he said, is that health care professionals in the United States do not think about such illnesses as dengue. The

lesson, he said, is “we have to do a better job of raising awareness [about arboviral diseases] among the doctors, the nurses, and health care professionals, particularly as we head into summer and fall months. . . . People just don’t think about these conditions.”

Staples said that such education will need to be tailored according to where in the world doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals are practicing. “When I’ve been in Africa, it’s malaria, malaria, malaria, and then maybe something else.” She noted that there needs to be some system that suggests what the “something else” might be, either as part of the doctor’s differential diagnosis or perhaps something in the laboratory that suggests what else should be tested. “But I agree the primary health care system is how we are likely going to pick up the potential beginning of a new pandemic,” she said.

Elaborating on that, Hotez spoke of a metagenomics analysis of the viromes of individual mosquitoes caught in various places to create a surveillance ecology of arbovirus infections (Pan et al., 2024). Such an approach could make it possible, he suggested, to know what viruses mosquitoes are carrying in any given location throughout the world. “This would be useful not only for human health but also for animal health . . . and I don’t think it’s even going to be that expensive.” “I would love to see an entire mapping exercise where we know where all the arboviruses are emerging, and I think this metagenomics approach is a very powerful way of doing it.”

REFERENCES

Hayman, B., and S. Pagliusi. 2020. Emerging vaccine manufacturers are innovating for the next decade. Vaccine X 5:100066.

Hotez, P. J. 2021. Preventing the Next Pandemic: Vaccine Diplomacy in a Time of Anti-Science. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hotez, P. 2023. Deadly Rise of Anti-Science: A Scientist’s Warning. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hotez, P. J., and A. D. LaBeaud. 2023. Yellow Jack’s potential return to the American South. New England Journal of Medicine 389(16):1445–1447.

Hotez, P. J., K. O. Murray, and P. Buekens. 2014. The Gulf Coast: A new American underbelly of tropical diseases and poverty. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 8(5):e2760.

Mehta, P., and P. J. Hotez. 2016. NTD and NCD co-morbidities: The example of dengue fever. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 10(8):e0004619.

Murray, K. O., L. F. Rodriguez, E. Herrington, V. Kharat, N. Vasilakis, C. Walker, C. Turner, S. Khuwaja, R. Arafat, S. C. Weaver, D. Martinez, C. Kilborn, R. Bueno, and M. Reyna. 2013. Identification of dengue fever cases in Houston, Texas, with evidence of autochthonous transmission between 2003 and 2005. Vector Borne Zoonotic Diseases 13(12):835-845. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2013.1413.

Pan, Y.-F., H. Zhao, Q.-Y. Gou, P.-B. Shi, J.-H. Tian, Y. Feng, K. Li, W.-H. Yang, D. Wu, G. Tang, B. Zhang, Z. Ren, S. Peng, G.-Y. Luo, S.-J. Le, G.-Y. Xin, J. Wang, X. Hou, M.-W. Peng, J.-B. Kong, X.-X. Chen, C.-H. Yang, S.-Q. Mei, Y.-Q. Liao, J.-X. Cheng, J. Wang, Chaolemen, Y.-H. Wu, J.-B. Wang, T. An, X. Huang, J.-S. Eden, J. Li, D. Guo, G. Liang, X. Jin, E.C. Holmes, B. Li, D. Wang, J. Li, W.-C. Wu, and M. Shi. 2024. Metagenomic analysis of individual mosquito viromes reveals the geographical patterns and drivers of viral diversity. Nature Ecology & Evolution 8(5):947-959. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02365-0.

This page intentionally left blank.