Mitigating Arboviral Threat and Strengthening Public Health Preparedness: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 6 Arbovirus Spillover and Spread

6

Arbovirus Spillover and Spread

Highlights

- The spillover and emergence of zoonotic pathogens can be analyzed in terms of four factors: spillover transmission from animals to humans, human-to-human transmissibility, the susceptibility of the human population, and the onward spread and connectivity. (Lloyd-Smith)

- Models using various types of data, including epidemiological data, environmental data, genomic data, clinical data, and experimental data, can be used to understand and predict the spread of emerging viruses. (Lloyd-Smith)

- CREATE-NEO (Coordinating Research on Emerging Arbovirus Threats Encompassing the Neotropics) is a network collecting data from surveillance sites and providing cutting-edge modeling approaches to dealing with emerging arboviruses. It also offers an example of how large amounts of data from disparate sources can be collected, organized, harmonized, analyzed, and made available to stakeholders. (Vasilakis)

- Risk assessment tools can be used to compare the risk of various arboviruses and identify which pose the greatest danger to public health and thus deserve the greatest scrutiny. (Pillai)

- Implementation science provides the tools for more effectively putting into practice the novel strategies for the prevention and control of arboviral diseases that have been developed by public health and medical researchers. (Paz-Soldán)

- Behavioral and social scientists must be involved in efforts to modify behavior at the individual, community, and system levels as part of arboviral disease prevention and control. (Paz-Soldán)

NOTE: These points were made by the individual workshop speakers/participants identified above. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Peter Daszak of the EcoHealth Alliance, who moderated the first session on the workshop’s second day, began by explaining that the sessions would examine innovative, forward-thinking approaches for future arbovirus mitigation. The first of the day’s three sessions would look at arbovirus spillover and spread. Daszak stated that understanding arboviral emergence requires analyzing the pathogen’s dynamics in its wildlife or livestock reservoir, understanding its movement through the human community, considering the environmental causes or drivers of those spillover events, and, finally, understanding the connections among human, animal, and environmental health, specifically with respect to arbovirus spillover and spread.

To bring those various perspectives to bear, four presenters would speak. First, Jamie Lloyd-Smith, professor in the Departments of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Computational Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, described using mathematical models to analyze zoonotic virus spillover and spread. Next, Nikos Vasilakis, vice chair for research in the Department of Pathology at the University of Texas Medical Branch, discussed CREATE-NEO (Coordinating Research on Emerging Arbovirus Threats Encompassing the Neotropics), a network collecting data and providing analytical tools to improve arbovirus prevention and control efforts. The third speaker, Segaran Pillai, director of the Office of Laboratory Safety at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), spoke about using risk assessment tools to identify those arboviruses that pose the greatest risks to human populations. Finally, Valerie Paz-Soldán, associate professor in the Department of Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease at Tulane University and director of Tulane’s Health Office for Latin America in Lima, Peru, described how implementation science and behavioral and systems sciences can be used to maximize the effectiveness of new interventions against arbovirus spillover and spread.

ZOONOTIC DISEASE SPILLOVER AND EMERGENCE

Lloyd-Smith began by defining the reproductive number R, which is the average number of secondary cases infected by a typical case. Thus, R being greater than 1 is the threshold for sustained transmission of a pathogen.

Lloyd-Smith said, there are four key factors in considering emergence risk. The first is spillover from animals to humans, which “throws sparks of infection into the human population,” he said. The second and third factors are human-to-human transmissibility and the susceptibility of the human population to the pathogen, which combine to determine the capacity for sustained spread. The transition to a larger epidemic or pandemic depends on the fourth factor: onward spread and connectivity in the human population plus the failure of any control measures.

The first factor, animal-to-human spillover transmission, is the defining characteristic of zoonoses, Lloyd-Smith said. Lloyd-Smith and colleagues proposed a general model for such spillover transmission that links the distribution and prevalence of infection in the reservoir hosts to the shedding of the pathogen into the environment, the possible pathogen survival or movement through the environment, and then the human behaviors that give rise to exposure to the pathogen as well as the host physical immune barriers that help determine the probability of an infection occurring.

Lloyd-Smith noted that these factors are dynamic, but when they align a spillover event can occur. The outcome of a spillover event can seem random, but studying the factors together can allow greater understanding of risk and possibly allow prediction of these events. Raina Plowright, one of Lloyd-Smith’s colleagues who developed that framework, used it to unpack the factors governing the spillover of Hendra virus from bats in Australia (Plowright et al., 2015). That line of work culminated in a 2023 paper published in Nature that described a model that could predict the likelihood of spillover clusters from environmental data (Eby et al., 2023). Over the course of a decade, the model made two clear predictions of years that would have spillover clusters, Lloyd-Smith said, and those were indeed the 2 years in which spillover clusters occurred.

For the second factor, human-to-human transmissibility, the goal is to estimate transmissibility for pathogens that are threatening to emerge but have not yet led to an epidemic or pandemic, so data that could be used to analyze the validity of models are scarce. A key challenge occurs with subcritical pathogens, which transmit only weakly among humans so they lead only to small, self-limiting transmission chains. This means, Lloyd-Smith explained, that observed human cases are a mix of primary cases caused by infection from animals and secondary cases caused by human-to-human transmission. “The problem is,” he said, “we don’t generally know which

are which.” In response, Lloyd-Smith’s team has developed model-based methods to estimate human-to-human R from real-world data (Blumberg and Lloyd-Smith, 2013a, b; Blumberg et al., 2014).

A parallel challenge that is important to assessing the risk of newly discovered viruses is using lab experiments, particularly from animal transmission studies, to infer something about human-to-human transmission. His team did a meta-analysis of ferret studies of flu transmission. (Buhnerkempe et al., 2015). They found that, statistically, if more than two-thirds of ferrets are infected via airborne spread, that strain is likely to be supercritical in humans—i.e., how well a flu strain spreads among laboratory ferrets via airborne transmission is an indicator of how strongly that strain is likely to spread through a human population.

The next frontier for this work, Lloyd-Smith said, is to get a clear understanding of the individual processes that go into a transmission event, including such things as virus shedding by the donor host, stability of the virus in the environment, dose–response dynamics, and immunity in the recipient, and use them to build a mechanistic model that can estimate transmission risk using virological data. “Then this can be tested against well-developed animal models for transmission and ultimately applied back in the human context,” he said. The potential of this approach is hinted at by a model-based analysis that he and a team at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) performed early in the COVID-19 pandemic; they combined experimental data on the surface and aerosol stability of SARS-CoV-1 versus SARS-CoV-2 and drew on the known epidemiology of SARS-CoV-1 to predict the potential for airborne transmission and superspreading of the new virus. This was in March 2020, long before either airborne transmission or superspreading was recognized as a driver of the pandemic (van Doremalen et al., 2020).

The third factor, susceptibility of a population, is also a key issue. Novel viruses or zoonotic viruses that have never circulated widely among humans can face substantial preexisting population immunity. For instance, when children get their first exposure to seasonal flu, they get immunologically imprinted to that hemagglutinin group, giving them lifelong protection against avian flu viruses that have hemagglutinin from the same branch of the hemagglutinin family tree (Gostic et al., 2016). Because of this pattern, he said, population susceptibility can be computed and even projected over time from available data on demography and on seasonal flu incidence. A similar situation occurred with mpox, but in this case it was driven by vaccination against smallpox rather than by childhood exposure to a related virus. With the global eradication of smallpox in 1980, countries stopped smallpox vaccination programs, so cohorts of children started growing up who were not vaccinated against that virus and thus did not have resistance to mpox. Data on human mpox incidence in the Democratic Republic of Congo show this pattern clearly, with cases concentrated in those age groups born after the cessation of smallpox vaccination (Taube et al., 2023).

Turning to the fourth factor, onward spread and connectivity, Lloyd-Smith emphasized that after the initial spillover, a virus needs to establish a transmission chain. In earlier work, Lloyd-Smith and colleagues showed that substantial individual variation in transmissibility is ubiquitous across infectious diseases and that it plays a role in how a disease spreads (Lloyd-Smith et al., 2005). When transmissibility is highly variable, superspreading events can occur in which one individual is likely to infect many more individuals than an average infected person would. When individual variation in transmissibility is high, the spreading pathogen can give rise to explosive major outbreaks, but an introduction of the pathogen is also more likely to die out. As an example, he pointed to the original SARS virus, which was predicted to die out 75 percent of the time following an introduction, even though its R0 of 3 is high enough to put it well into the dangerous domain (Lloyd-Smith et al., 2005).

The next hurdle to a viral introduction leading to an outbreak comes from the host population structure, he said. To cause a large epidemic, an outbreak must jump from its initial location to other regions. A key factor here, said Lloyd-Smith, is how often infected people move around relative to the infectious period. If movements are relatively rare, he said, “it doesn’t matter how transmissible the pathogen is, it’s going to burn out. It won’t be able to penetrate the full population.” Similarly, although traveler screening programs can affect the spread of a disease, the effectiveness of these programs will depend on the natural history of the infection, such as the incubation period, and on knowledge of risk factors, such as fever (Gostic et al., 2016). Unfortunately, Lloyd-Smith said, COVID-19 has a set of factors that mean that traveler screening programs will fail most of the time if it is the sole strategy in use.

In closing, Lloyd-Smith offered summarizing points. First, if emergence risk is broken into a series of constituent steps, each of those can be studied in turn. Then, he continued, “if we can think about the mechanisms that give rise to success of a pathogen in any one of these steps, that both enables us to study it more fruitfully and to come up with means of combating it.” Upfront investments in modeling platforms and in data pipelines can help build capabilities for rapid response when new events occur and will also enable rational risk assessment that can guide longer term investment.

IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE: OPERATIONALIZING ONE HEALTH DATA

Vasilakis is a principal investigator of CREATE-NEO,1 which provides a network of surveillance sites in Central and South America along with cutting-edge modeling approaches with the goal of anticipating and

___________________

countering emerging arbovirus and SARS-CoV-2 threats. He spoke specifically about some of the tools used in CREATE-NEO to operationalize the growing masses of data as well as how those tools can be disseminated to various stakeholders and be used to ensure secure accessibility for all interested parties.

CREATE-NEO has several study sites across the Americas, and it applies a One Health approach in trying to understand the drivers behind viral emergence and outbreaks. It is a member of a global network of networks that generate “vast mountains of data that are coming from the different collection points,” Vasilakis said. This amount of data raises many questions in terms of how it can best be handled, how to ensure ownership, how to ensure access, and how to make sure that credit goes to the people who have generated the data. Some have suggested, for example, that data should be stored in the originating institutions rather than in a centralized repository (CCGTT et al., 2017). This would ensure ownership, but there would need to be some way that the data could be accessed and analyzed by members of the global research community using widely available but secure methods under conditions that would ensure respect for the sensitivities of the originators of specific data.

Over the past 10 or 15 years, Vasilakis said, the number of public databases has greatly proliferated, and with the appearance of so many databases have come several challenges for those who would use them to address problems. First, the databases vary greatly in the type and scale of data and in the structure and size of the database. They vary in the quality of the data being collected, how often they are collected, and the level (local, country, global) at which they are collected. The databases also vary in the types of data collected. Regulatory and compliance issues may limit access to the data, and access may also be limited by more practical issues, such as how the data are stored (manual versus digital) and what language the database uses. Stakeholders in low- and middle-income countries may not be able to afford the necessary tools to access remote networks, for instance. These challenges together may hinder outbreak responses, Vasilakis said, because they may limit access to knowledge that could be crucial in recognizing a particular pathogen or learning lessons from previous experiences with it.

Next, Vasilakis provided a brief overview of some of the technologies CREATE-NEO uses to deal with the vast amounts of available data and meet the above challenges. There is great promise, he said, in semantic technology, which “collects data from different sources and assigns them machine-readable meanings.” A critical component of semantic technology is knowledge graphs, which are used to connect disparate data with certain underlying elements across domains and skills. In creating a knowledge graph, primary data sources are identified first,

then nodes are identified, and relationships between nodes are harmonized. This allows the knowledge graph to provide different outputs to the various stakeholders who would like to access those data and base decisions on them.

Vasilakis described work done by Barbara Han and Hailey Robertson to develop methods to use knowledge graphs for ecological systems, a major component of the CREATE-NEO research. Their work is intended to synthesize fragmented human, epidemiological, environmental, and zoonotic risk data; identify knowledge gaps; and generate hypotheses about, for example, what spillover events occur and what their frequency is. Such work depends critically on open data sources, he continued, but with open access comes several other issues that must be addressed, such as the issue of ownership and how contributors of data can be recognized and rewarded.

Vasilakis then described work by Peter McCaffrey, a physician at the University of Texas Medical Branch, to develop a “data lakehouse” that is used for primary storage, access, and interrogation of data. Individual collaborators deposit data of various types—metadata, clinical data, geolocation files, and so on—directly into an Amazon Web Services S3 storage system. In essence, Vasilakis said, the system integrates and assesses the data that are input and provides meaningful outputs for the various stakeholders. The data can be of a wide variety of types—radiology images, clinical notes and interpretations from clinicians, lab results, and more. The various stakeholders of CREATE-NEO, including international policy makers, private researchers, clinicians, and people who help facilitate the operations, can access all those data, analyze the data, repurpose them for other analyses and, in general, obtain useful information out of them.

Looking to the future, Vasilakis said that there are many gaps remaining. Stakeholders must be able to claim ownership while facilitating data accessibility, he said. Removing barriers to data sharing will also be important. One of the ways that the CREATE-NEO network has approached that accessibility challenge is with collaboration agreements and memoranda of understanding that provide a foundation for sharing data. Communication with the stakeholders is also vital, he added, since they must understand and appreciate the responsibility and accountability that come with sharing the data, such as giving credit to and being respectful of the ownership of the individual contributors.

Finally, Vasilakis said, there needs to be comprehensive and effective programs for the acquisition of data as well as for stakeholder engagement. It will be important to ensure that the benefits of using the data from this network, whether the discovery of a new vaccine or better tools for clinical care, are distributed equitably and benefit the original contributors of the data.

RANKING DISEASE THREATS

Pillai described in detail a method he developed to rank the seriousness of threats from different arboviruses and what the rankings reveal when viewed in different ways. He offered the caveat that “this is still a work in progress and will require some further refinement upon consultation with my colleagues, who are experts in this area.”

He began with some context. Globally, more than 25 percent of human infectious diseases are vector-borne diseases, and these diseases contribute to more than 2.5 million deaths each year. Mosquitoes and ticks are the main vectors, along with sandflies and midges. To date, more than 550 arboviruses have been described, of which about 50 cause disease in animals and more than 130 cause infections and diseases in humans and animals. It is important to periodically conduct risk assessments to inform activities designed to prevent, prepare for, and respond to arbovirus outbreaks.

To rank the disease threats posed by various arboviruses, Pillai used a standard multistep approach. It begins by clearly defining the key factors that will be used in the analysis and establishing the criteria for scoring. The next step is data collection, where all the available scientific data and information that can be used to score the criteria are gathered. With that information, a score is assigned to each virus on each criterion using the established scoring scheme. Next, weights are assigned based on importance of the criteria. Then the analysis is performed using a one-dimensional or two-dimensional approach with and without the assigned weights so that the different outcomes can be compared.

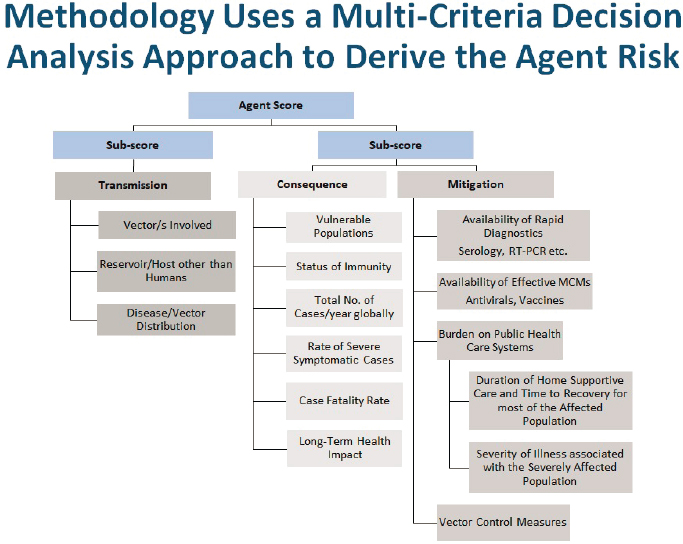

Additionally, Pillai performs a decision support framework analysis, which is “a very simple logic-tree approach, asking a series of critical questions that will either move the virus to the next stage or drop it out from any further analysis.” Pillai’s risk assessment included a total of 54 viruses that cause disease in humans: 14 Flaviviridae, 13 Togaviridae, 2 Reoviridae, 4 Rhabdoviridae, and 21 Bunyaviridae. Three key factors were considered in determining the risk score of each virus: transmission, consequence, and mitigation (Figure 6-1). The transmission factor considered the vectors involved, the reservoir of hosts other than humans, and the disease/vector distribution pattern. The consequence factor included vulnerable populations, status of immunity, total number of cases per year, severity of symptoms, the case fatality rate, and long-term health impacts. The mitigation factor examined the availability of rapid diagnostics, availability of medical countermeasures, burden on public health care and vector control measures

In scoring the viruses, Pillai explained, each criterion was scored on a scale of 0 to 10 for each virus. For example, in the case of fatality rate, a rate greater than 25 percent would get a score of 10, 20–24 would get a score of 8, and anything close to 0 percent would get a score of 0. Each

SOURCE: Presented by Segaran Pillai on December 13, 2023.

criterion was assigned a weight, and the overall score for a virus was determined by summing the individual weighted criterion scores for that virus.

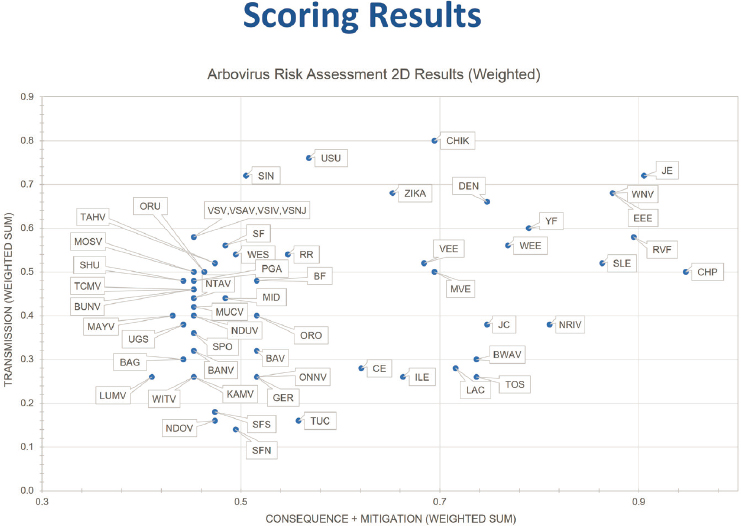

Displaying the scores in a two-dimensional plot as opposed to a one-dimensional plot allows additional insight on risk ranking and clarifies distinctions among viruses that rank in the middle, Pillai said. This plot elucidates where the virus scored in terms of transmission versus its score in terms of consequences plus mitigation. Weighing the criteria provided better separation of the agents in both the one-dimensional and the two-dimensional plots. In the two-dimensional plots, the upper right quadrant contains viruses with both a high transmission score and a high impact score, the lower right quadrant has viruses with a low transmission score but high consequences, and so on (Figure 6-2). Again, one can determine thresholds of interest, although in the two-dimensional case, the thresholds will be in the shape of an L and everything above and to the right of the L are beyond the threshold.

Next, Pillai shared the results of evaluating the same set of arboviruses with the decision support framework instead of the risk scores. The various factors considered in that framework were agent qualification, transmission, disease, vulnerable populations, pathogenicity and severity

NOTES: Arboviruses in top right box indicate viruses with both a high consequence score and a high impact score. CHPV = Chandipura virus; EEEV = Eastern equine encephalitis virus; JEV = Japanese encephalitis virus; RVFV = Rift Valley fever virus; SLEV = St. Louis encephalitis virus; WEEV = Western equine encephalitis; WNV = West Nile virus; YFV = yellow fever virus.

SOURCE: Presented by Segaran Pillai on December 13, 2023.

of illness, hospitalization rates, the availability of rapid diagnostics and medical countermeasures, the morbidity and mortality rates associated with the pathogen or the disease, and, finally, the public health impact. In comparing the results from the scoring analysis and the decision support framework analysis, Pillai said, he found that the two-dimensional weighted scores and the decision support framework identified nearly the same tier 1 and tier 2 risk groups. Among the four different ways of analyzing the risk assessment scores—weighted versus unweighted and one-dimensional versus two-dimensional—differences appeared in, for example, exactly which viruses made it into tier 1, but in general the results were mostly consistent. “Overall,” he said, “what we are observing is Japanese encephalitis virus, Eastern equine encephalitis virus, Chandipura virus, West Nile virus, Rift Valley Fever Virus, Saint Louis encephalitis virus, yellow fever virus, and

Western equine encephalitis virus seem to consistently fall in the tier 1 risk group of arboviruses.”

In conclusion, Pillai said that the analysis should be seen mainly as a tool rather than as a single result. “If any of the data change, those data can then be applied to the scoring scheme and applied back into the risk assessment tool and replot the entire graph,” he said. “So, it’s not a static assessment, but it’s a very fluid, very dynamic process of doing risk assessment.” It allows one to respond very quickly to changes in circumstances with a new analysis and new understanding in terms of which viruses pose the greatest risk to public health.

BEHAVIOR MANAGEMENT TO PREVENT SPILLOVER AND SPREAD

Modifying human behavior can play an important role in preventing and controlling outbreaks of arboviral disease, Paz-Soldán said. Behavior change matters, she explained, because it enables the implementation of novel and evidence-based strategies in diverse epidemiological, geographic, and cultural contexts. It is important to consider behavior change at the individual level and at the community systems level when implementing arbovirus prevention and control efforts, Paz-Soldán continued. In studying what works to create such behavioral change, she said, randomized controlled trials are not necessarily the optimal choice because an innovation may not be put into practice the same way it was done in a trial. So, she concluded, research should focus on how programs are implemented in real settings with real challenges and real bottlenecks and on how to deal with these challenges as they emerge.

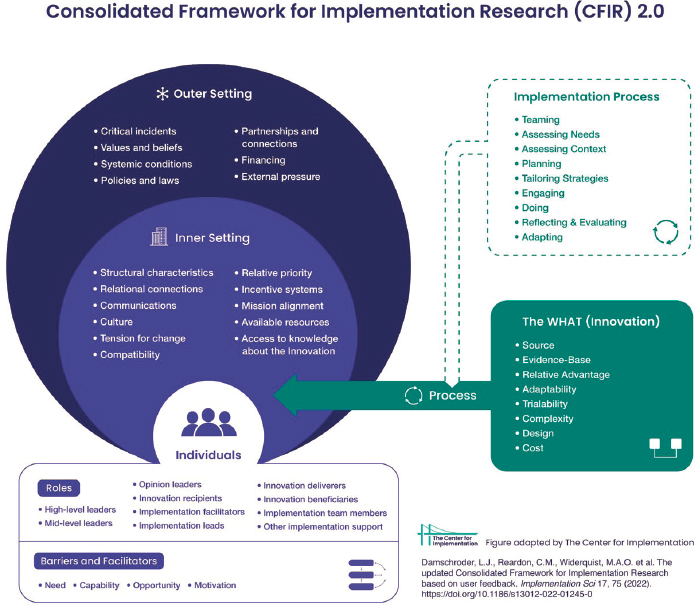

Paz-Soldán highlighted that it is important to consider how to implement approaches such as new vaccines and new vector-control strategies that are showing effectiveness. This is where implementation science fits in, she said. “Implementation science . . . is the science that translates evidence into policy and into practice. And it takes into consideration the fact that context matters, that the different levels in stakeholders matter, and that the processes by which we apply these innovations matter.”

To illustrate the important factors in implementation research and how they fit together, Paz-Soldán referred to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (Damschroder et al., 2022) (Figure 6-3). The framework begins with “the what,” or the innovation that needs to be implemented. Much of the funding in this area focuses on developing effective strategies for arboviral disease prevention and control, she said, but it is also important to think about how these strategies are put into practice. Finally, one must consider the individuals involved in the implementation

SOURCES: Presented by Valerie A. Paz-Soldán on December 13, 2023. From the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) 2.0, 2022. Adapted from The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback, by Damschroder, L.J., Reardon, C.M., Widerquist, M.A.O. et al., 2022, Implementation Sci 17, 75. Copyright by The Center for Implementation. https://thecenterforimplementation.com/toolbox/cfir; CC BY 4.0.

and the environments in which they operate, from the individuals who deliver the innovation, those who receive it, and to various leaders and facilitators and beneficiaries.

Implementation scientists need to observe and consider all of the different aspects of implementation in the figure, Paz-Soldán said. In the case of “the what,” for instance, one must consider the evidence base behind the innovation as well as its complexity, design, cost, and relative advantage over other strategies. These factors help determine which innovations to prioritize and which should get funded in a specific country or setting.

The environments involved with the innovation begins with those individuals living in an area affected by the arbovirus and targeted by an intervention. The individual’s beliefs about the intervention or how they perceive

it to work or not work is important to consider. Next there are people in what Paz-Soldán called the “inner setting,” which includes those involved in primary health care and those local or regional health authorities who need to decide how to operationalize the intervention. Finally, there is the “outer setting,” which includes such things as the policies and regulations coming from the national level, international guidance, partnerships, and funding.

As an example of the sort of outer setting that must be considered, Paz-Soldán spoke about the situation in her country of Peru, which has had seven presidents and 16 ministers of health in the past 8 years. “The ministers of health have had an average, I think, of 143 days in office,” she said, “so, they are not thinking long term.” They are thinking about what they can be doing in 2 or 3 months that can make a difference. Furthermore, if something goes wrong, the minister at the time will likely be the scapegoat. Thus, it is a major challenge to convince the health minister to use their limited time in office to put into place the evidence-based strategies that have been identified by scientists as working in much less challenging settings.

The inner setting offers equally vexing challenges. Even if the minister of health instructs local directors to adopt a certain policy, the local officials are faced with all sorts of difficulties, such as unclear strategy, time, funding, and uncertainty of responsibilities, Paz-Soldán said. Conflicts of interest must also be considered. “You want to call it corruption, you want to call it conflict of interest,” she said, “but a lot of times the insecticide that we decide upon is because your friend who’s working in this lab is selling that one. That’s the reality of the situation.”

Finally, at the individual level, implementation scientists must think about what is realistic to expect in terms of changing individual behavior. Is it reasonable to expect people to regularly wear masks for months at a time or to apply insecticide every day when it is costly and irritates the skin and eyes? People can come to view diseases as inevitable. And sometimes when the government takes steps, such as instituting a vector-control program, individuals may decide that it is not their responsibility and the government will take care of it.

To address these challenges, implementation science has strategies for adapting an innovation to a particular context, but this requires pre-implementation preparation, such as developing protocols, creating a timeline, and determining who will have responsibilities for various tasks. Such preparation needs to take place at both the national level and the regional level, Paz-Soldán added. Furthermore, the workers need to consider what data streams and information will be available and how to identify where bottlenecks are occurring, and they should continuously monitor and evaluate the situation. A key aspect of all of this is the question of whose respon-

sibility it is to plan, adapt, and implement these new strategies and who should be contacted when the program hits a snag.

The positive message to take away from this, Paz-Soldán said, is that implementation science does offer an effective approach to dealing with these various challenges. However, it is handicapped by a lack of funding. Foundations, for instance, have focused mostly on developing evidence-based interventions. “You can spend millions of dollars on that one innovation,” she said, “but it’s rare to even give $20,000 to a social scientist trying to pilot how this innovation can be made sustainable practice in a community.” The NIH now has a funding mechanism through which to fund implementation science, she said, and that gives her hope that there will be more focus on the process by which innovations are put into practice.

In conclusion, she said, behavioral and social scientists need to be part of encouraging the individual-, community-, and system-level behavioral change needed to enable arboviral disease prevention and control. It will be crucial to take a more transdisciplinary approach to integrate social and behavioral scientists into the overall arbovirus mitigation efforts. Funding should focus on behavior change as well as on the development of evidence-based vector control, vaccines, and treatments. And education in this area should emphasize developing researchers trained in a transdisciplinary approach who look at all the different parts of the system and focus on keeping all the cogs in that machine working together smoothly.

To close, she offered an African proverb: If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go accompanied. “We must work together towards those challenges.”

DISCUSSION

In the discussion session following the presentations, Lloyd-Smith was asked how his models deal with the fact that each spillover event involving an emerging disease seems to be unique and complex and whether findings from his models can be applied broadly across emerging diseases.

Lloyd-Smith responded that that complexity was one of the motivations for his team’s effort to determine the minimal set of factors needed to line up for a spillover event to occur. His goal is to work with the rich descriptions of various spillover events and extract the details that answer the specific questions asked by the model. “The hope is that we can at least find the commonalities among all these different rich anecdotes and particular events,” he said. He noted that some spillover events—such as the West African Ebola outbreak or the origins of COVID-19—are of very high consequence, while many other spillover events occur regularly by the same mechanisms but without serious consequences. “One of the important

questions, I think, is the degree to which we can learn about the processes which may give rise to those rare high-impact events by studying the more common ones,” he said. “Can we learn about the science of spillover from things that are spilling over all the time?” The goal, he concluded, is to apply this systematic approach to synthesize evidence and then identify the common themes and turn that into actionable interventions.

Next, Marcos Espinal asked Paz-Soldán about the issue of building trust and engagement with communities, particularly those in low- and middle-income countries. Trust is not built overnight, Paz-Soldán replied. “I think it has really helped that I am Peruvian. I live in Peru. I was born and raised there, and I spent the last 20 years living near the communities.” However, she continued, it is also vital to identify local champions, nurture those relationships, and then rely on those champions to influence their communities and help move things forward. It is also important to give back to communities when possible. Finally, she added that the trust low- and middle-income countries had in the Global North was damaged during the COVID-19 pandemic because of the lack of equity in vaccine distribution.

Next, a workshop participant asked Vasilakis about the best way to ensure long-term funding for databases. Vasilakis acknowledged that funders often lose interest in funding databases once they have been established, but he said that the CREATE-NEO network “offers a pathway for maintaining those databases in either centralized or individualized databases that may be able to be assessed, given the widespread interactions and/or collaborations across various entities.” CREATE has established relationships among many different networks, he said, and it should be possible to maintain those relationships over long periods of time with the contributions of individual stakeholders. As for the databases themselves, maintaining them and having access to them is crucial, he said, and the various stakeholders recognize that. Ultimately, “it takes advocacy on our part to make the appropriate [funders] fully appreciate the long-term utility and maintenance of those databases.”

Another workshop participant asked Paz-Soldán about continuity in health authorities in low- and middle-income countries, getting funding for the “last mile” of implementing arbovirus control programs, and how to argue for behavioral change, given that the available evidence indicates that behavioral factors generally account for no more than 20 percent of the explanation for the success of programs.

Concerning the first question about fast turnover and information that is lost, Paz-Soldán acknowledged that being something she struggles with. One approach she has considered is creating partnerships between academia and mid-level technicians at the health institutions who are less likely

to turn over quickly to make it more likely that any lessons learned become part of the institutional memory. Ultimately, she said, researchers should be studying that issue of sustainability and coming up with strategies for building it up. On the issue of the last mile, she said that the implementation science grants that have been gaining traction have created an environment in which there is a greater appreciation of the importance of the last steps in putting an innovation in place. This, in turn, may make it easier to get funding for the last mile and make sure that the new innovation becomes a sustainable practice in the community.

Finally, she acknowledged that there have been many theories of behavior change and many of them have not worked. “Human behavior is very complex,” she said. “There are so many different levels that maybe 20 percent is actually not that bad.” The key is that when one is thinking about arboviral disease prevention and control, the entire system needs to be considered. There will always be value in considering the specifics of human behavior and culture in each place, but it should only be a part of a larger, more comprehensive approach that addresses the systems.

Lloyd-Smith was then asked how the data analyses used to predict the risk of viral outbreaks could be used to encourage people to take preventive measures against something they cannot see, particularly since if the predictions are accurate and the preventive measures are effective, outbreaks would not occur. One approach, he said, would be to carefully document pathogens that are constantly spilling over and produce a reliable estimate of their risk, “so that when you do put in interventions and hopefully reduce that risk, you’re able to make a reliable quantitative assessment of the impact of those interventions.” Something similar could be done with viruses that have less spillover but pose the risk of a major epidemic when they do get into the human population, Lloyd-Smith said. Daszak added that if economists could provide a dollar value for the human illnesses and deaths prevented by the control efforts, that might make for an even more compelling argument.

REFERENCES

Blumberg, S., and J. O. Lloyd-Smith. 2013a. Inference of R0 and transmission heterogeneity from the size distribution of stuttering chains. PLOS Computational Biology 9(5):e1002993.

Blumberg, S., and J. O. Lloyd-Smith. 2013b. Comparing methods for estimating R0 from the size distribution of subcritical transmission chains. Epidemics 5(3):131–145.

Blumberg, S., W. T. Enanoria, J. O. Lloyd-Smith, T. M. Lietman, and T. C. Porco. 2014. Identifying postelimination trends for the introduction and transmissibility of measles in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology 179(11):1375–1382.

Buhnerkempe, M. G., K. Gostic, M. Park, P. Ahsan, J. A. Belser, and J. O. Lloyd-Smith. 2015. Mapping influenza transmission in the ferret model to transmission in humans. eLife 4:e07969.

CCGTT (Clinical Cancer Genome Task Team of the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health), M. Lawler, D. Haussler, L. L. Siu, M. A. Haendel, J. A. McMurry, B. M. Knoppers, S. J. Chanock, F. Calvo, B. T. The, G. Walia, I. Banks, P. P. Yu, L. M. Staudt, and C. L. Sawyers. 2017. Sharing clinical and genomic data on cancer—The need for global solutions. New England Journal of Medicine 376(21):2006–2009.

CFIR (The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research 2.0). 2022. Adapted from “The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback,” by L. J. Damschroder, C. M. Reardon, M. A. O. Widerquist, et al., 2022. Implementation Science 17:75. Copyright by The Center for Implementation. https://thecenterforimplementation.com/toolbox/cfir (accessed June 5, 2024).

Damschroder, L. J., C. M. Reardon, M. A. O. Widerquist, and J. Lowery. 2022. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implementation Science 17(1):75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0.

Eby, P., A. J. Peel, A. Hoegh, W. Madden, J. R. Giles, P. J. Hudson, and R. K. Plowright. 2023. Pathogen spillover driven by rapid changes in bat ecology. Nature 613(7943):340–344.

Gostic, K. M., M. Ambrose, M. Worobey, and J. O. Lloyd-Smith. 2016. Potent protection against H5N1 and H7N9 influenza via childhood hemagglutinin imprinting. Science 354(6313):722–726.

Lloyd-Smith, J. O., S. J. Schreiber, P. E. Kopp, and W. M. Getz. 2005. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature 438(7066):355–359.

Plowright, R. K., P. Eby, P. J. Hudson, I. L. Smith, D. Westcott, W. L. Bryden, D. Middleton, P. A. Reid, R. A. McFarlane, G. Martin, G. M. Tabor, L. F. Skerratt, D. L. Anderson, G. Crameri, D. Quammen, D. Jordan, P. Freeman, L. F. Wang, J. H. Epstein, G. A. Marsh, N. Y. Kung, and H. McCallum. 2015. Ecological dynamics of emerging bat virus spillover. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282(1798):20142124.

Plowright, R. K., C. R. Parrish, H. McCallum, P. J. Hudson, A. I. Ko, A. L. Graham, and J. O. Lloyd-Smith. 2017. Pathways to zoonotic spillover. Nature Reviews Microbiology 15(8):502–510.

Taube, J. C., E. C. Rest, J. O. Lloyd-Smith, and S. Bansal. 2023. The global landscape of smallpox vaccination history and implications for current and future orthopoxvirus susceptibility: A modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 23(4):454–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00664-8.

van Doremalen, N., T. Bushmaker, D. H. Morris, M. G. Holbrook, A. Gamble, B. N. Williamson, A. Tamin, J. L. Harcourt, N. J. Thornburg, S. I. Gerber, J. O. Lloyd-Smith, E. de Wit, and V. J. Munster. 2020. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. New England Journal of Medicine 382(16):1564–1567.

This page intentionally left blank.