Mitigating Arboviral Threat and Strengthening Public Health Preparedness: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 7 Urban Development and Management

7

Urban Development and Management

Highlights

- Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are the major carrier of the most important arboviruses, such as dengue, Zika, yellow fever, and chikungunya, so it makes sense to focus prevention and control efforts on these mosquitoes, particularly in urban areas, where the risks of transmission are highes. (Lindsay)

- “Building-out” interventions, which focus on changing the built environment in ways that make it less hospitable to mosquito breeding and create barriers to human contact by mosquitoes, are an effective way of reducing the transmission of arboviruses in urban areas. (Lindsay)

- Urban areas will become an increasingly important area for vector-control efforts as they grow in the coming decades, particularly in those parts of the urban areas occupied by slums, which have poorer infrastructure and health care. (Alabaster)

- Vector-control efforts and public health programs need to be tailored to the urban area in question; a “one size fits all” approach does not work. (Alabaster)

- A two-pronged strategy where short-term pilot projects demonstrate the value of a particular approach and influence the design of larger, longer-term projects can be effective in convincing cities to incorporate new vector-control techniques. (Alabaster)

- Experience in Singapore shows that reshaping the built environment—in this case, moving a significant percentage of the population from low-lying slums to high-rise apartments—can have a major effect on the transmission of arboviruses. (Ooi)

- In Africa, a new mosquito species that carries malaria, Anopheles stephensi, is spreading in urban areas. Because it often shares its larval habitats with Aedes aegypti, there are opportunities here for integrated surveillance and control of both types of mosquitoes with benefits for both malaria and arboviral diseases. (Wilson)

NOTE: These points were made by the individual workshop speakers/participants identified above. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Linda S. Lloyd of San Diego State University served as moderator of the workshop’s sixth session, which discussed how best to control the spread of arboviral diseases in urban areas. The panel’s first speaker was Steve Lindsay, a public health entomologist and epidemiologist at Durham University, who discussed ways to modify urban infrastructures to limit populations of Aedes mosquitoes and their ability to transmit viruses. Next, Graham Alabaster, the director of UN–Habitat at the Geneva office of the United Nations (UN), spoke about how to design and implement vector-control projects designed for specific urban areas. Dr. Eng Eong Ooi, a professor in the emerging infectious diseases at the Duke-National University of Singapore Medical School, offered a case study of how Singapore limited the transmission of arboviruses, such as dengue, through a combination of vector control programs and replacing most of its slum neighborhoods with high-rise buildings developed by the government. Finally, Anne Wilson, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, described the appearance of a new malaria vector in Africa, Anopheles stephensi, and suggested that there is an opportunity to combine surveillance and control efforts for malaria with those for arboviral diseases.

VISION FOR BUILDING AEDES OUT

Lindsay spoke about “building out Aedes,” which is the approach of modifying urban environments to control the spread of arboviruses by limiting breeding opportunities for Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

In recent decades, Lindsay said, there have been huge increases in the number of dengue cases around the world, mainly in the tropics and subtropics, and there have also been growing numbers of Zika, yellow

fever, and chikungunya cases. All these diseases are transmitted by Aedes aegypti. This species is the world’s most efficient vector of viruses, and it is distributed throughout most of the world’s tropical and subtropical regions, including much of South America, Central America, and the Southeastern United States as well as subtropical Africa, India, and Southeast Asia. It was originally a forest mosquito, breeding in tree holes, but it was able to spread around the world because its eggs are highly resilient and it adapted to breeding in small containers of water. “It is an extraordinarily adaptable, invasive species,” he said. In modern cities, Aedes aegypti will lay its eggs wherever there is standing water. Most commonly this means in open containers where people are storing water because the local water supply is not reliable, in discarded tires with collected rainwater, and bits of waste in which water sits.

Lindsay’s approach to controlling arbovirus transmission is built on limiting the numbers of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. He focuses on urban areas because this is where most of the arbovirus transmission problem exists today and because, if it is not addressed, the problem of arbovirus transmission in urban areas will get much worse in the future. “Urban population will double by 2050,” he said, “and nearly seven out of ten people in this world will live in cities” (World Bank, 2023). Though this is a challenge, the urban population explosion also offers an opportunity, he continued, as 60 percent of the urban areas that will be there in 2050 have not yet been built. “[This is] important because it presents an opportunity to guide the design of towns and cities around the world because most of this increase is not going to be in the cities that are already built, but it’s going to be in what we now think of as secondary towns.”

Focusing efforts on cities rather than countries can also be effective because cities are recognized as engines of change, he said. Epidemiologists and researchers can work with mayors to show that by taking steps to reduce Aedes aegypti populations, they can provide a healthy environment for workers and improve the economy, Lindsay said.

Lindsay’s group’s approach to controlling mosquitoes is two-pronged. The first prong is enhanced integrated control, which he described as a fusion of classical entomological and clinical approaches, including traditional surveillance tools combined with the appropriate responses when signs of the vector or the disease are spotted. The second prong is what Lindsay referred to as “building out,” or changing the environment to be less conducive to the spread of Aedes aegypti. “Essentially what we’re trying to do is prevent small bodies of water [from] accumulating and doing something to reduce biting rates and biting indoors as well,” he said. One way to do this, for instance, is to provide reliable pipe water. If people know that they can turn on the tap and water will come out, they will have no reason to store water. It will also be important to remove trash, improve

drainage, close water containers, remove gutters, build concrete structures that are impervious to mosquitoes, and make sure that homes have screening. Lindsay noted the importance of building clean cities where there is less surface water. Most importantly, he continued, the interventions need to be tailored to local conditions. Building out Aedes should be a city-led approach with dynamic city leaders who can pull people together and break down silos.

Lindsay outlined an approach that relies on three foundations: community involvement and support, a health department that works across sectors, and research and development. Community involvement is important not only because the approach requires getting buy-in from the community but also because the community can make suggestions about what local innovations might be appropriate when coming up with solutions to problems. Having health departments working across sectors is about breaking down barriers, Lindsay said, with the ultimate goal of having collaborations between health departments and those in the built environment. Continued research and development are also necessary, noting that greater investment to assess efficacy of interventions is essential. This approach involves distinct types of actions: effective surveillance, monitoring, and evaluation of interventions; mosquito control by means of reducing breeding sites, engineering the built environment, and using pesticides; and the use of vaccines, antivirals, and case management to control viral transmission in the human population. The combination of these actions would, he said, lead to effective, locally adapted control of Aedes-transmitted viral disease.

The approach fits well with the UN sustainable development goals created in 2015, Lindsay said. Goal 3, for example, is good health and well-being. Goal 6 is clean water and sanitation. Goal 11 is sustainable cities and communities. “We need to think about the control of dengue and other viral diseases as a sustainable cities or towns [issue],” he said. Goal 13 is climate action, which is particularly relevant because climate change could increase the range of Aedes aegypti and may also prolong the mosquitoes’ season, exacerbating future epidemics. A secondary effect of climate change may be increased droughts, which could lead to people being more likely to store water in open containers and providing more habitat for Aedes aegypti.

Lindsay acknowledged that the building-out approach would be expensive and outside the usual bounds of public health, but there are already examples of cities planning future growth with various forward-looking objectives in mind. He pointed, for instance, to the Making Cities Resilient 2030 initiative, which involves a collection of agencies who assist cities in making their communities more resilient and sustainable (UNDRR, n.d.). Given that such a network of cities focused on future sustainability issues already exists, it would make sense to reach out to the people in this net-

work and explain that there is another major environmental problem—that of Aedes-transmitted viral diseases—that their cities need to be defended from. “These networks exist, but they don’t understand the language and we’re not tapping at their doors, and we should be,” Lindsay said. “There is an opportunity here.” Lindsay highlighted the importance of a city leader-led approach that engages communities and develops innovative mitigation strategies that meet health, sustainability, and economic needs of the city.

PUBLIC HEALTH IN URBAN ENVIRONMENTS

Alabaster spoke in general about the factors affecting public health in urban environments and what can be done to improve public health. Across the globe, more and more people are living in cities. By 2030, projections indicate that about 5 billion people will live in cities, up from just more than 2 billion in 1990. In the coming years it will not be just the bigger cities that are growing, but medium-size cities will also grow extremely fast.

Urban areas are susceptible to issues relating to health and environment for a variety of reasons, he said. Many of them lack the necessary capacities in the health sector, and the process of urbanization is extremely inefficient. This leads to large unplanned areas, which are referred to by various names in different parts of the world—slums, bustees, favelas, and so on—and in many countries, these areas are where much of the workforce live.

The result, Alabaster continued, is that even in the more developed regions of the world, many cities have an underclass of people who lack access to basic services. It is most pronounced in sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia and Southern Asia, where approximately half of the urban population was living in slums in 2020. “Those are the people who don’t have access to services,” he said, such as health services, water, sanitation, and waste management.

Although worldwide the percentage of urban populations living in slums has decreased significantly over the past 20 years (from 64 percent to 50 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, for instance), slum populations are still increasing. Many people are driven by conflict or climate change to migrate to large cities, and they generally end up in the low-income areas. Alabaster said he and colleagues have studied the capacity of the slums in these cities, “and it’s reaching saturation.” Thus, they anticipate further reduced access to health services and increased incidences of disease in these areas.

The COVID-19 pandemic offered an indication of what could be expected in urban areas hit by an arbovirus outbreak, he said. The pandemic magnified existing inequities in health care in urban settings, with those who had poorer access to health care before the pandemic feeling the effects of those inequities to a much greater degree during the pandemic. A variety of factors governed the varying impacts of COVID-19,

Alabaster said. One such factor was overcrowding. “It’s not just about density,” he explained. “It’s about overcrowding of services and access to services.” Comorbidities also played a major role. In the Global North, the most important comorbidities during the pandemic were noncommunicable diseases, while in the south they were other communicable diseases, particularly vector-borne diseases. Differences in treatment-seeking behavior played a role in how COVID-19 affected people differently, as did demographics. Furthermore, cities were very different in their ability to respond; some of the cities that did well in the pandemic were the ones that had effective triaging systems and isolated the most vulnerable populations early on. City governments are responsible for implementing national policy, but they are also the ones who best know their community, Alabaster noted. Because of these differences among cities, a “one-size-fits-all” response to an epidemic or pandemic is not likely to be widely effective, Alabaster said. It is vital to understand the specifics of an individual community in order to deliver effective services, and that in turn requires accumulating a great deal of spatially disaggregated data—not just on the populations but also on their access to services. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the UN developed a dashboard for cities that focused on city statistics, rather than national statistics, which contained data provided by local health departments. This might be something that could be usefully applied to arboviral diseases, he suggested, because it could provide better spatial information on an outbreak.

Alabaster said that one can think about urban areas as providing opportunities rather than challenges. For example, 60 percent of the urban areas that will exist in 2050 have not yet been built, so making sure those areas are designed and built to promote better health and greater resistance to the spread of arboviral and other diseases could make a huge difference to the people who will be living in them. Furthermore, cities offer opportunities because they can be shaped by strong local civic leaders. Such leaders are the “missing middle”—they are well placed to work with the national government, and they are the ones with the best knowledge of their communities. And it is at the local level that many policies important to public health—such as policies for solid waste management—are determined. “Many of the things that we know we can do to control the disease vectors are the responsibility of municipal authorities,” Alabaster said.

One key to convincing city leaders of the importance of arboviral disease mitigation, he said, is to emphasize that the methods used to deal with these diseases will be effective with other cities as well. In the Kenyan city of Kisumu during the COVID-19 pandemic, enteric diseases almost disappeared because of the hygiene methods imposed for COVID. That was a “marvelous learning experience” for the city officials in Kisumu because it helped them see how valuable such methods were to improved health

outside of COVID. City leaders must see the health and economic benefits of making environmental modifications, such as piped water and waste disposal, he said.

An important tool for convincing city leaders and urban planners of the importance of these steps is the use of pilot demonstrations. Providing short-term “quick wins” in things like vector control can make it more likely that cities will adopt some of the effective approaches in their more long-term plans for urban expansion. In November 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) and UN–Habitat launched the Healthy Cities, Healthy People initiative, which is designed to get mayors and other local authorities to understand and invest in a health-promoting infrastructure. One goal of the Healthy Cities, Healthy People initiative is to generate these small-scale pilot projects and encourage cities to take that approach in their longer-term infrastructure projects. It may be challenging to find funding to carry out short-term trials and demonstrations in some neighborhoods of the city, but once the value of the new approach has been established, Alabaster said, “it becomes a relatively easy step to upscale and to expand into other areas of the city.” In conclusion, Alabaster summarized what is needed to move urban areas in a direction that is more resistant to arboviral diseases. The first step is to understand the urban landscape in detail, particularly concerning the inequities in cities. Second, there should be a two-pronged approach in which short-term demonstrations and their results guide and inform longer-term plans. Third, it will be crucial to unlock community potential for surveillance, innovation, education, and advocacy as well as to nudge the national governments. “This is what happened with COVID,” Alabaster said. “They saw good examples of what was happening locally, and they used it to adapt and adjust their national policy.”

In selling this approach to local officials, advocates should emphasize not only the value of reducing the threat of vector-borne diseases but the benefits relative to other diseases as well. “If you rethink urban space and you design it better for vector-borne diseases,” he said, “there is a good chance you can also deal with the enteric diseases which are there and maybe some non-communicable diseases. . . . So, it’s a win-win if we design carefully.” Finally, he said, funding is always a challenge, but if short-term demonstrations can be funded, they can be used to catalyze long-term changes.

CASE STUDY FROM SINGAPORE

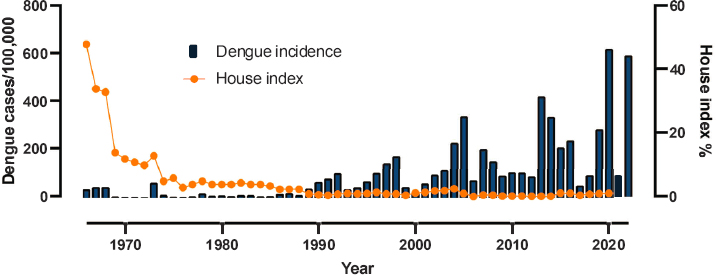

To illustrate some of the factors that influence arbovirus spread in an urban area, Ooi described the history of dengue incidence in Singapore. He began by showing a graph tracking the incidence of dengue versus the house index, or the percentage of houses infested with Aedes larvae or pupae, which is a measure of the abundance of Aedes mosquitoes (Figure 7-1).

SOURCES: Presented by Eng Eong Ooi, December 13, 2023; generated with data from the Ministry of Health, Singapore.

Dengue first became a notifiable disease in Singapore in 1966, and, in response, a vector-control program was developed and implemented by K. L. Chan, the head of the Vector Control and Research branch of the Ministry of Health, which was eventually transferred to the Environment Ministry (Chan, 1985). The program began in the late 1960s with a series of studies and pilot control programs that eventually led to its formal launch in 1970. Chan described the first part of the program, which lasted until 1972, as “a loosely knitted integrated system.” After a postmortem analysis of an outbreak that occurred in 1973, the vector control program was refined, and a new control strategy was developed. Still, the Aedes aegypti population dropped steadily beginning in 1966—before the finished vector control program was put into place—until the present. This drop in mosquitoes was likely due to the 1971 Concept Plan, developed with help from the UN Development Programme, after Singapore became an independent country in 1965. A major aspect of the plan was to free up space wherever possible, and a major opportunity for freeing up space could be found in slum housing.

In 1959, about 550,000 out of the 1.6 million people living in Singapore lived in slum housing, Ooi said. In 1960 Singapore formed the Housing Development Board to free up land by rehousing people from slum houses into high-rise apartments and to encourage home ownership. “This was partly as a way of building the nation so that the population had an ownership of the country,” he said. The result was a steady decline in the number of people in slum housing to the point that by 2000, slum housing was exceptionally rare. At the same time, the number of people living in Housing Development Board flats in high-rise buildings rose dramatically, and the number of people living in high-rise condominiums that were not developed by the Housing Development Board also increased. By 1990,

most of Singapore’s population lived in high-rise buildings, with about 5 percent living in houses with their own land, and very few still in slums.

That transformation played a major role in the decline of the Aedes aegypti population in Singapore, Ooi argued. A paper published in 1971 reported on the distribution of the mosquitoes in different types of buildings in Singapore (Chan et al., 1971). It found that more than 27 percent of slum houses had mosquito larvae and that there were an average number of 5.52 larvae per housing unit. By contrast, only 5 percent of the flats in high-rise apartments had the mosquito larvae, with an average number of only 0.81 larvae per unit. A different analysis found that the Aedes population density in Singapore dropped sharply and then more steadily as the number of new housing units grew from 40,000 to more than 400,000 between 1966 and 1975 (Chan et al., 1985). Ooi connected the drop in mosquito population beginning in the mid-1960s to the construction on new high-rise housing, the movement of people from slum housing to the high rises, and, ultimately, the destruction of most of the slum housing.

Still, even as the amount of slum housing dropped to near zero, the population density of Aedes aegypti settled in at a low but non-zero level. Another factor may be playing a role in the burden of dengue in Singapore, he suggested. As the economy has steadily improved, the birth rate has steadily dropped to the point that the total fertility rate is less than two. This has led to a steady aging of the population, with the mean age of the population increasing. And that in turn, Ooi said, seems to have led to an increase in the average age and age distribution of those people in Singapore who have contracted dengue. Adult cases make up nearly 90 percent of total dengue cases in Singapore each year (Low and Ooi, 2013). This has led to a fundamental change in the type of dengue cases commonly seen in Singapore. In general, Ooi said, the rate of plasma leakage from small blood vessels is much greater in children than in adults (Gamble et al., 2000). When children are exposed to the dengue virus, they are much more likely than adults to develop dengue hemorrhagic fever, which is being characterized by plasma leakage. And, indeed, data from Singapore show that as the percentage of dengue cases that take place in those 15 years and younger has gone down, the rate of dengue hemorrhagic fever as a percentage of all cases of dengue fever has also gone down (Ooi et al., 2003). Overall, the burden of dengue has declined in Singapore, but the question still remains, however, why overall cases of dengue have increased in recent years.

The takeaway message, Ooi said, is that the rehousing of much of the Singaporean population benefited dengue prevention. Although it was motivated by economic reasons and did not involve dengue control, the change to the infrastructure seems to have significantly reduced dengue. This was combined with the changes put in motion by the growing economy, which lowered the birthrate, increased the average age of the population, and led

to a lower burden of dengue hemorrhagic fever. In short, reshaping the environment has the potential to make a major difference in controlling dengue and potentially other Aedes-transmitted diseases.

URBAN MOSQUITO CONTROL IN AFRICA AND THE NEW MOSQUITO ON THE BLOCK

In the session’s last presentation, Wilson spoke about the appearance of a new mosquito species in Africa, Anopheles stephensi, which carries malaria and may force those working to control malaria on the African continent to modify their strategies.

Reviewing the basics of malaria, she said it is a severe, febrile illness caused by Plasmodium parasites and transmitted by female Anopheles mosquitoes. It exerts a major public health burden, with, according to the latest World Malaria Report, a worldwide total of 249 million cases in 2022, which resulted in 608,000 deaths. In Africa, malaria is typically a rural disease, and its primary carrier is the Anopheles gambiae species, which likes to lay eggs in standing water such as found in puddles, ditches, and rice paddies. It typically bites humans indoors at night when they are sleeping, and it rests indoors as well. The primary control methods have been insecticide-treated bed nets and the indoor residual spraying of insecticides. These mosquito control tools, coupled with certain other effective treatments, dramatically decreased the incidence of malaria in Africa between 2000 and 2015, Wilson said, with bed nets alone being responsible for 68 percent of the decline. “This was a real success period in malaria control. However, in the past few years, we’ve started to see stagnation in progress and an increase in malaria cases globally, and we don’t fully understand why this is.”

Wilson then provided some relevant background on dengue in Africa. Dengue and other arboviral diseases have been largely neglected in Africa, she said, and for a long time, dengue has been misdiagnosed as malaria since both are febrile illnesses, and the diagnostic tools needed to distinguish between the two are often lacking. Many countries also have limited surveillance for Aedes mosquitoes. However, she continued, the hidden burden of dengue in Africa is becoming more widely recognized with many of the recorded outbreaks since 2011 having taken place on the eastern part of the continent.

Returning to malaria, Wilson said that in the past few years a new, invasive species of malaria-carrying mosquito, Anopheles stephensi, has been detected in Africa.1 Anopheles stephensi is different in many ways

___________________

1 During an earlier session discussion, Duane Gubler noted that the used tire trade was in fact responsible for introducing Aedes albopictus into the United States and Europe in the mid-1980s. He speculated that the used tire trade likely played a role in the introduction of Aedes albopictus into Africa as well.

from the endemic malaria mosquitoes in Africa. For instance, it is urban adapted, and it thrives in standing water in tires, water barrels, and man-made containers of the sort that Aedes aegypti inhabits. Anopheles stephensi can transmit both Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax parasites, and it is also able to persist through dry periods with its eggs surviving for months without water. As a result, the usual seasonality seen with rural malaria in Africa is not holding for this new mosquito.

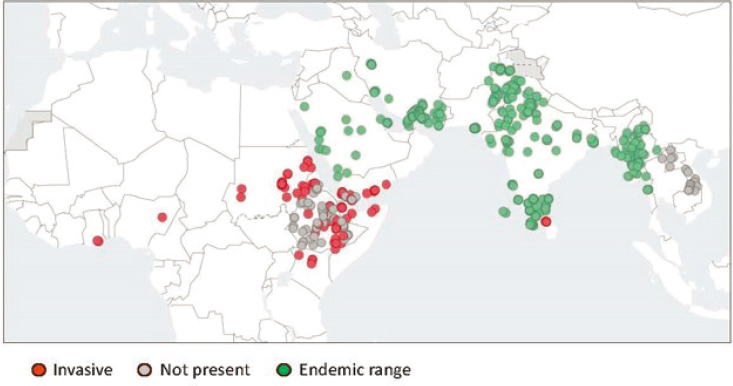

According to data from WHO, Anopheles stephensi is spreading across Africa (Figure 7-2). It was first identified in the Horn of Africa in Djibouti in 2012 and since then has been spreading throughout the Horn to Ethiopia, Sudan, Puntland, and Somaliland. More recently it was detected in Nigeria, Ghana, and Kenya as well, which suggested that its distribution is more widespread than originally thought. And, unfortunately, the arrival of this new species of Anopheles in Africa has been associated with increases in the numbers of malaria cases.

The experiences in two countries illustrate the potential dangers of this spread. Djibouti had reached pre-elimination status for malaria—the stage between control and complete elimination—in 2011, but since Anopheles stephensi was detected there in 2012, there has been a 36-fold increase in malaria cases. No causal connection between the arrival of Anopheles stephensi and the dramatic jump in malaria has been established, Wilson said, but it is “very worrying.”

In Ethiopia, Anopheles stephensi is distributed widely throughout the country, and in 2022 there was a dry season outbreak of malaria that has been linked, at least partially, to Anopheles stephensi (Emiru et al., 2023). Using mathematical models, researchers at the Imperial College London have estimated that in Ethiopia Anopheles stephensi could cause a 50 percent increase in malaria cases, which would require an additional $72 million a year for control (Hamlet et al., 2022). Modeling studies done by Marianne Sinka from the University of Oxford suggest that an additional 126 million people in urban areas across Africa could be at risk of Anopheles stephensi–transmitted malaria (Sinka et al., 2020). Given the limited resources available in Africa for the control of malaria and other vector-borne diseases, she said, this situation “really presents a major threat towards effective malaria control” and elimination.

Recognizing this threat, in September 2022 WHO launched an initiative to stop the spread of Anopheles stephensi. Its five key components are to increase collaboration, strengthen surveillance, improve information exchange, develop guidance, and prioritize research (WHO, 2022). However, Wilson said, the initiative faces a number of challenges. Anopheles stephensi is difficult both to surveil and to control. The adult mosquitoes can be elusive, and there are few good traps for catching them. Anopheles stephensi is resistant to many of the insecticides normally used for adult

SOURCES: Presented by Anne Wilson, December 13, 2023. Taken from WHO Malaria Threats Map, https://apps.who.int/malaria/maps/threats/ (accessed February 24, 2024).

control. Furthermore, there is no indication that the mosquitoes engage in indoor biting or resting, so the standard malaria control tools, such as indoor residual insecticide spraying, may not work well with them. And while larval control is attractive for Anopheles stephensi, this approach is not widely practiced in Africa and would need capacity strengthening. Finally, there are questions about the best allocation of resources. For instance, should resources be diverted from rural malaria control programs to put more focus on cities when it is not yet clear exactly what effect Anopheles stephensi is likely to have on malaria incidence?

Given that Anopheles stephensi has commonalities with Aedes aegypti, Wilson said, there are opportunities for co-surveillance and co-control of the two types of mosquitoes, thereby strengthening efforts against both malaria and arboviral diseases. For instance, Anopheles stephensi and Aedes aegypti often share the same larval habitats, so there is an opportunity for integrated surveillance of both vectors as well as for integrated control by finding and removing standing water or covering water containers or using larvicides to kill the larvae.

Opportunities for synergy also exist with such things as harnessing the efforts of town councils and city leaders and engaging diverse sectors to support control and surveillance efforts for both types of mosquitoes. For example, Wilson said, several of the settings in Ethiopia where she is carrying out research on Anopheles stephensi suffered massive droughts, so there is no piped water. The water is brought in by private truck companies

which fill household or community-owned systems of 10,000 to 20,000 liters, and these are the major habitats for the mosquitoes in these towns. “Engaging these water companies and local water sellers could be pivotal in controlling mosquitoes,” she said. Finally, entire communities could be engaged in identifying and removing larval habitats. In this case, it would be important to tailor messages to the local context and explain how the presence of Aedes aegypti and Anopheles stephensi raise the risks of malaria as well as dengue and other arboviruses.

DISCUSSION

A participant began the discussion period by asking Alabaster what will be required to modify or remove slums in urban areas to limit the transmission of arboviruses.

A major problem, Alabaster replied, is that slums exist for various practical reasons, and unless there is strong political will to move forward to remove slums, they will remain. For instance, slums economically suit the slum dwellers, because many of them are single individuals who have come to a city to earn money and send that money home, and they want somewhere cheap to live. Furthermore, he continued, “many of the landlords of slum dwellers are mid-level government professionals who make a tidy living from collecting rents in slums.” To get around these obstacles, it helps to have a “champion inside the ministry who is prepared to look at the long-term aspects of improving the life of those people,” he said. It is also crucial to carry out a demonstration project that shows the value of the suggested changes to the community. “Once the communities are engaged, whether the mayor changes or the minister of health changes, it doesn’t matter because the community will make demands from the local authority.”

Lindsay, in response to a question from Lloyd, provided some additional information on the Making Cities Resilient 2030 initiative. Many organizations were involved, Lindsay said, and one of the chief drivers from the United States was the Rockefeller 100 Resilient Cities Network. When mayors from different cities get together, they are pushed by competition to do more in their own cities, and they also learn what practices have and have not worked in other areas. He noted that the initiative is not prescriptive and accounts for feasibility at the local level. Wilson added that it is important to encourage city leaders to consider vector-borne diseases as potential threats just like earthquakes, sea level rise, or long-term unemployment.

In response to an online question, Ooi said that when Singapore made the transition from slum housing to flats in high-rise apartments, it also provided piped water and improved sanitation and refuse collection. Fur-

thermore, the fact that Singapore is a multiethnic country was considered in the transition as well, and today all of the housing estates have a mandatory ethnicity mix. “Every housing estate has to have a fair distribution of the races according to the national composition,” he said, with the goal of building integrated communities.

Wilson offered a few more thoughts on combined surveillance and control efforts for both Anopheles stephensi and Aedes aegypti. There is relatively little surveillance of Aedes in Africa, she said, and researchers may pay attention to either Aedes or Anopheles but not both. There is a need for more coordination between these two groups to develop vector-borne disease programs instead of malaria-only programs. She noted a research group in Sudan that has an integrated vector management department that does surveillance for diseases transmitted by snails, sandflies, and mosquitoes of all sorts. Good practices do exist in some countries, she said. but they need to be expanded and strengthened.

Lloyd then directed a question about Singapore to both Ooi and Lee Ching Ng, who had spoken on the previous day. If rebuilding Singapore made such a difference in removing breeding grounds for the mosquitoes, was vector control necessary after that? Ng answered that transferring people from slums to high-rise buildings did not automatically remove the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. There were still many places where water could collect, even inside the new high-rise homes. Singapore continued to educate its citizens on how to minimize the number of places that mosquitoes could breed, such as plates under a potted plant. Vector control in Singapore was focused more on removing places where standing water was available to mosquitoes rather than on such things as fogging or chemical control. Ooi added that Singapore refined its vector-control program over time to the point that it eventually became very effective.

Alabaster reiterated that the huge amount of urban space that will be built out between 2024 and 2050 offers a tremendous opportunity for creating areas where people live that are designed to resist the spread of vector-borne disease. “The incremental costs of ensuring that new urban development is future-proofed from vector-borne disease” would be minimal, he said, involving only slight changes in the design of the urban space. This new understanding of how urban design can be used to discourage the transmission of arboviruses and other vector-borne diseases is appearing at the same time as some powerful new tools, such as vaccines and environmental management, are becoming available for the prevention and control of these diseases. “So, I think the fact that the two are coming together means we have an opportunity that we shouldn’t miss,” he concluded.

REFERENCES

Chan, K. L. 1985. Singapore’s Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever Control Programme: A Case Study on the Successful Control of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus Using Mainly Environmental Measures as Part of Integrated Vector Control. Tokyo: SEAMIC.

Chan, Y. C., K. L. Chan, and B. C. Ho. 1971. Aedes aegypti (L.) and Aedes albopictus (Skuse) in Singapore City: 1. Distribution and density. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 44:617–627.

Emiru, T., D. Getachew, M. Murphy, L. Sedda, L. A. Ejigu, M. G. Bulto, I. Byrne, M. Demisse, M. Abdo, W. Chali, A. Elliott, E. N. Vickers, A. Aranda-Díaz, L. Alemayehu, S. W. Behaksera, G. Jebessa, H. Dinka, T. Tsegaye, H. Teka, S. Chibsa, P. Mumba, S. Girma, J. Hwang, M. Yoshimizu, A. Sutcliffe, H. S. Taffese, G. A. Bayissa, S. Zohdy, J. E. Tongren, C. Drakeley, B. Greenhouse, T. Bousema, and F. G .Tadesse. 2023. Evidence for a role of Anopheles stephensi in the spread of drug- and diagnosis-resistant malaria in Africa. Nature Medicine 29(12):3203–3211.

Gamble, J., D. Bethell, N. P. Day, P. P. Loc, N. H. Phu, I. B. Gartside, J. F. Farrar, and N. J. White. 2000. Age-related changes in microvascular permeability: A significant factor in the susceptibility of children to shock? Clinical Science (London) 98(2):211–216.

Hamlet, A., D. Dengela, J. E. Tongren, F. G. Tadesse, T. Bousema, M. Sinka, A. Seyoum, S. R. Irish, J. S. Armistead, and T. Churcher. 2022. The potential impact of Anopheles stephensi establishment on the transmission of Plasmodium falciparum in Ethiopia and prospective control measures. BMC Medicine 20(1):135.

Low, J. G., and E. E. Ooi. 2013. Dengue—Old disease, new challenges in an ageing population. Annals of the Singapore Academy of Medicine 42(8):373–375.

Ooi, E. E., K. T. Goh, and D. N. C. Wang. 2003. Effect of increasing age on the trend of dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever in Singapore. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 7:231–232.

Sinka, M. E., S. Pironon, N. C. Massey, J. Longbottom, J. Hemingway, C. L. Moyes, and K. J. Willis. 2020. A new malaria vector in Africa: Predicting the expansion range of Anopheles stephensi and identifying the urban populations at risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(40):24900–24908.

UNDRR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction). n.d. MCR 2030: Making Cities Resilient. https://mcr2030.undrr.org/ (accessed February 18, 2024).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2022. World Malaria Report 2022. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2022. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2022 (accessed October 31, 2024).

World Bank. Urban Development. April 3, 2023. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview (accessed March 25, 2024).

This page intentionally left blank.