Biological Effectors of Social Determinants of Health in Cancer: Identification and Mitigation: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: Proceedings of a Workshop

Proceedings of a Workshop

WORKSHOP OVERVIEW1

Social factors such as the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age; their education and income; and many other elements can influence their likelihood of developing cancer, the type of cancer, the cancer stage at diagnosis, the quality of care they receive, and their health outcomes. While the complex interactions among these factors, known as the social determinants of health (SDOH),2 can make it difficult to identify and quantify their biological consequences, researchers are beginning to pinpoint biological mechanisms through which social factors influence health and disease and elucidate how identifying and addressing social risk factors along the cancer care continuum could improve patient outcomes.

___________________

1 This workshop was organized by an independent planning committee whose role was limited to identification of topics and speakers. This Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the rapporteurs as a factual summary of the presentations and discussions that took place at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

2 According to the World Health Organization, SDOH are the nonmedical factors that influence health outcomes. They are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. These forces and systems include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies, and political systems. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed July 3, 2024).

To examine the complex interactions among biological variables and SDOH, and opportunities to mitigate the negative impacts of social factors on cancer-related health outcomes, the National Cancer Policy Forum of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine hosted a workshop on March 20–21, 2024, that brought together participants with backgrounds in clinical care, cancer research, health care policy, patient advocacy, and related areas. This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the issues discussed and highlights observations and suggestions made. Those from individual participants are discussed throughout the proceedings, and highlights are presented in Boxes 1 and 2. (Box 1 lists observations on the relationships between SDOH, cancer, and health care biological effectors of SDOH, and Box 2 outlines potential strategies for integrating SDOH into cancer research and care.) Appendixes A, B, and C provide the workshop Statement of Task, agenda, and poster session participants, respectively. Speaker presentations, poster presentations, and the workshop webcast have been archived online.3

Chanita Hughes-Halbert, associate director for cancer equity and professor of public and population health sciences at the University of Southern California, provided context for the discussions by defining cancer health disparities, which she said are differences in both cancer risk and outcomes that are linked to social, economic, or environmental variables associated with disadvantage, such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), gender, and location. She noted that as the understanding of cancer health disparities expands, researchers are increasingly examining the role of these SDOH while also striving to create social, physical, and economic environments that enable everyone to attain their full potential for health and well-being, including through the objectives articulated in Healthy People 2030.4

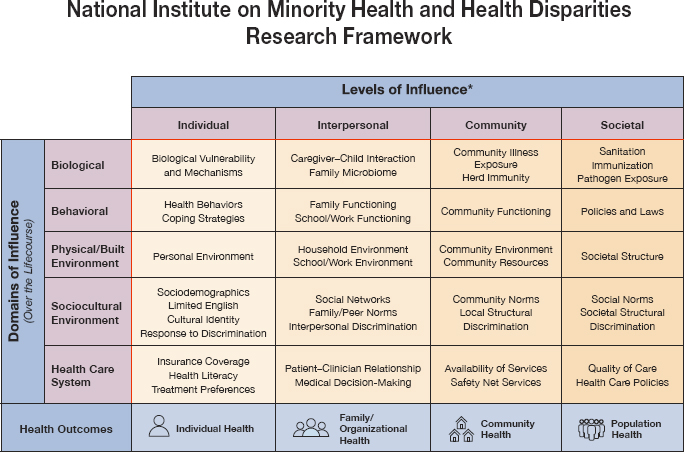

Hughes-Halbert posited that a holistic, multilevel perspective can enable transdisciplinary teams to address the complexities of the impact of SDOH on health disparities (see Figure 1) (NIMHD, 2018). She noted that researchers are increasingly able to link social factors to health disparities, such as the higher rate of hormone receptor-negative breast cancer among Black women compared to White women (Linnenbringer et al., 2017). She suggested that it will be useful for researchers to continue examining this complex web of issues to create paradigm-shifting, transformational, multi-perspective approaches that both identify and mitigate cancer health disparities, from basic research to strategic implementation (Dankwa-Mullan et al., 2010).

___________________

3 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/41369_03-2024_biological-effectors-of-social-determinants-of-health-in-cancer-identification-and-mitigation-a-workshop (accessed June 24, 2024).

4 See https://health.gov/healthypeople (accessed May 22, 2024).

NOTE: *Health disparity populations: racial and ethnic minority groups (defined by OMB Directive 15),a people with lower socioeconomic status, underserved rural communities, sexual and gender minority groups, people with disabilities. Other fundamental characteristics: sex and gender, disability, geographic region.

SOURCES: Hughes-Halbert presentation, March 20, 2024; NIMHD, 2018.

_____________

a See https://spd15revision.gov/content/spd15revision/en/2024-spd15.html (accessed July 17, 2024).

“There is room for all of us and all disciplines to be involved in this research to really increase our understanding and ability to drive policy and the delivery of health care by understanding the contributions of racial and ethnic segregation, the neighborhood environment, psychosocial stressors, psychological distress, the things that we would typically include as part of our understanding and work around SDOH,” Hughes-Halbert emphasized.

Stanton Gerson, dean of the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, said that residents of distressed communities suffer devastating health effects because “poverty is a carcinogen,” as Samuel Broder famously said in 1989 (ACS, 2011). While an individual’s living conditions can contribute to cancer development, it is important to note that this depends on specific biological factors. Gerson stressed that it is critical to uncover connections

between the drivers of SDOH and the biological causes and consequences of cancer.

A range of biological mediators and pathways are associated with cancer, including genetics, epigenetics,5 ancestry, allostatic load, stress response, norepinephrine,6 cortisol,7 obesity, ingested and inhaled toxins, reactive oxygen,8 and inherited or acquired mutations, Gerson explained, while SDOH include a wide range of factors, such as poverty, racism, heat, noise, violence, disruption of sleep and circadian rhythms, environmental exposures, food access, and smoking. Hughes-Halbert noted that researchers are increasingly demonstrating connections between environmental exposures and health outcomes, such as finding microplastics in the hearts of patients with cardiovascular disease or linking chemical exposure to multiple negative health outcomes (Marfella et al., 2024; Woodruff, 2024).

HEALTH DISPARITIES AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH IN CANCER

Several speakers offered context on health disparities in cancer risk, onset, screening, treatment, and response to treatment, along with an overview of the relationships among SDOH, cancer, and health care.

Health Disparities in Cancer

Approximately 600,000 people die from cancer in the United States every year, making it the second leading cause of death, after heart disease (CDC, 2022). Yet, the disease burden is not experienced equally across the population. Otis Brawley, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Oncology

___________________

5 Epigenetics is the study of how age and exposure to environmental factors, such as diet, exercise, drugs, and chemicals, may change how genes are switched on and off without changing the actual DNA sequence. These changes can affect a person’s risk of disease and may be passed from parents to their children. See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/epigenetics (accessed July 6, 2024).

6 Norepinephrine, or noradrenaline, is a neurotransmitter and hormone that is released in response to stress or low blood pressure. See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/norepinephrine (accessed July 11, 2024).

7 Cortisol is a hormone that “helps your body respond to stress, regulate blood sugar, and fight infections.” See https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?contenttypeid=167&contentid=cortisol_serum (accessed July 11, 2024).

8 Reactive oxygen is a free radical (an unstable molecule) that can accumulate in and cause damage to cells. See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/reactive-oxygen-species (accessed July 11, 2024).

BOX 1

Observations from Individual Workshop Participants on the Relationships Among SDOH, Cancer, and Health Care

- Disparities in cancer screening, treatment, and outcomes are linked with social factors such as belonging to historically marginalized groups, lower socioeconomic status, and racial and economic discrimination and disadvantage, the impacts of which can go beyond the individual to span generations and communities. (Bae-Jump, Brawley, Evans, McCullough)

- Where patients live and receive care influences the quality of their care. (Frencher, Gerson, Watson)

- Research has linked social determinants of health (SDOH) with clinical outcomes, but an understanding of the specific pathways through which the upstream social context creates downstream health outcomes remains limited, in part because a dearth of data from diverse populations has limited researchers’ ability to deeply understand these complex linkages. (Bae-Jump, Carlos)

- Biomarkers such as epigenetic changes and extracellular vesicles could provide insights into the connections between SDOH and cancer. (Carlos, Evans, Llanos, Obeng-Gyasi)

- Access to biomarker testing is uneven, contributing to care disparities. (Ferris, Vidal)

- Electronic health records can enable collecting and acting upon SDOH data but are generally not consistently and effectively utilized for this purpose. (Fayanju, Ferris, Hughes-Halbert)

- Sufficient and sustainable funding models are important for incorporating interventions to address SDOH into clinical care and reducing health disparities. (Evans, Winn)

- Even as researchers continue to elucidate the downstream biological effectors of SDOH on health outcomes and develop ways to target those mechanisms to intervene, it remains important to address the structural root causes of the inequities that lead to health disparities. (Gottlieb, Hiatt, Llanos, Mbah, McCullough, Tucker-Seeley)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ synopsis of observations made by one or more individual speakers as identified. These statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

BOX 2

Suggestions from Individual Workshop Participants on Integrating SDOH into Cancer Research and Care

Building Trust and Collaboration

- Repair bilateral trust in communities by enabling communities to lead initiatives to address health disparities and ensuring that community members benefit from the research and interventions. (Darien, McCormick, McCullough, Rogers, Winn)

- Improve collaboration and communication among researchers from different disciplines and among researchers, clinicians, and communities. (Fayanju, Frencher, McCullough, Tucker-Seeley, Winn)

- Support training and employment opportunities for community members to participate in navigation, patient advocacy, research, education, and policy. (Cogle, McDonald, Rogers, Vidal)

- When asking patients about social determinants of health (SDOH) in clinical settings, explain why the information is being collected and how it will be used; then, follow up to address needs identified during this process. (Fayanju, Hughes-Halbert, McCullough, Shulman, Smith, Tucker-Seeley)

- Discuss and address ethical concerns in biomarker testing to ensure trust and participation from vulnerable communities. (Cogle, McCullough)

Improving Data Collection and Analysis

- Improve metrics for holistically studying interconnected SDOH to accurately capture meaningful data. (Hughes-Halbert, McCullough, Shulman, Tucker-Seeley)

- Develop and implement effective methods, tools, and best practices to coordinate, collect, harmonize, link, and share SDOH data for research and care, and act upon SDOH in clinical care settings. (Bradley, Fayanju, Gomez, Gottlieb, Hughes-Halbert, McCullough, Rogers, Shulman, Tucker-Seeley)

and Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, defined health disparities research as the study of why some populations—defined by their gender, race, education level, area of geographic origin or residence, genetic ancestry, SES, or other factors—suffer unnecessarily worse health outcomes than others. The concepts of “health equity” and “health justice” relate to efforts focused on combating these health disparities, which affect disease incidence, outcome, mortality, and quality of life.

- Incentivize including diverse populations in clinical trials and studies. (Evans, Mbah, McCullough, Vidal, Yates)

Improving Care to Address Social Determinants of Health

- Focus on early-life exposures as a critical piece of cancer prevention. (Brawley, Fayanju, Llanos, Rebbeck, Seewaldt, Winn)

- Ensure equitable access to broadly validated biomarker tests. (Gerson, Vidal)

- Facilitate care coordination among primary care providers and specialists to address social needs and better support cancer prevention, screening, and treatment. (Bradley, Darien, Fayanju, Frencher)

- Implement interventions that reduce disparities in care access and quality now, even as research continues to elucidate the biological mechanisms linking SDOH with health outcomes. (Brawley, Shulman)

Incentivizing Strategies to Improve Health Equity

- Utilize existing reimbursement mechanisms for assessing and addressing SDOH and create new mechanisms. (Honig, Lofton, Tucker-Seeley)

- Reduce health disparities by implementing payment models that allow clinicians to spend more time with patients. (Brawley, Ferris, Hughes-Halbert, Llanos, Rogers, Seewaldt, Winn)

- Advocate for social policies that directly address socioeconomic needs, using biomarker data to highlight the severe impact of social conditions on health. (Cogle, McDonald)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ synopsis of suggestions made by one or more individual speakers as identified. These statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Health disparities researchers often aim to uncover the upstream factors that contribute to differences in disease development, detection, and treatment. Brawley emphasized the importance of early-life factors in cancer prevalence, stating that “cancer prevention and health promotion is a pediatric issue.” He noted, for example, that most people who smoke begin in their teens, and eating habits, which can lead to obesity, are learned in childhood.

Brawley emphasized that race—a common focus of health disparities research—is not a biological trait but rather a sociopolitical categorization, which is redefined every 10 years for the U.S. census. Anthropologists and the American Medical Association no longer accept biological definitions of race because they imply that certain traits are inherent or immutable and have been used to harm and dehumanize people in the past.9 However, Brawley pointed out that there are nevertheless areas of intersection between race and health. For example, he noted that a person’s area of geographic origin or genetic ancestry, categories that are different from but correlated with race, can influence health outcomes. In addition, certain racial groups are disproportionately represented among various SDOH, such as income level (Semega et al., 2019).

Methods to address health promotion and disease prevention are critical, Brawley explained, because this is where the spectrum of disease control begins, followed by screening, diagnosis, and treatment. He posited that the emphasis on diagnosis and treatment over prevention or risk reduction in the U.S. health care system has contributed to health disparities. For example, almost half of U.S. cancer mortality is attributable to known external risk factors, such as smoking or obesity, that are related to SDOH factors, such as race, education, and gender (Islami et al., 2018). In addition, extrinsic environmental factors can influence genetic markers and disease behavior, blurring the contributions of biology and health disparities to disease and making it difficult to determine why, for example in the United States, Black women are diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer at double the rates of White women (Dietze et al., 2015; Millikan et al., 2008; Palmer et al., 2014).

Brawley characterized providing high-quality care, including preventive services, to populations that rarely receive it as today’s most pressing disease control challenge. For example, people who belong to historically disadvantaged groups or have lower SES are more likely to receive inadequate care (Crown et al., 2023). Brawley noted that while Black women have a consistently higher death rate from breast cancer than White women, this disparity emerged only after the implementation of screening, because some populations had less access to screening and follow-up care (Lund et al., 2008; Mandelblatt et al., 2016; van Ravesteyn et al., 2011). SES is particularly associated with care access and quality in the United States. For instance, people with lower SES are less likely to receive radiation treatment or have access to newer, higher-quality medical equipment (Mattes et al., 2021; Washington et al., 2022). Treatment disparities also stem from cultural differences, comorbidities, lack of insurance or transportation, and racial or economic discrimination

___________________

9 See the American Medical Association policy H-65.953, https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/racism%20social%20construct?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-H-65.953.xml (accessed June 27, 2024).

(Lannin et al., 1998). Overall, Brawley stated that equitable treatment does not exist in the United States (NASEM, 2024). He stressed that solutions do exist, citing research estimating that making evidence-based prevention and treatment programs accessible to all could save more than 100,000 U.S. lives every year (Siegel et al., 2018).

Defining Social Determinants of Health

Reginald Tucker-Seeley, principal and owner of Health Equity Strategies and Solutions, pointed out that in the United States, adverse SDOH are disproportionately distributed across race, ethnicity, SES, and other groupings. These maldistributions are shaped by interrelated social, economic, and environmental factors; affect health equity; and can be altered through informed action (Braveman and Gottlieb, 2014; Krieger, 2001a; NASEM, 2017).

The health care ecosystem is improving its understanding and conceptualization of SDOH and their links to poor health outcomes, social risks,10 and social needs,11 Tucker-Seeley explained. Addressing SDOH can reduce health care costs and improve efficiency, he stated, because while they may be beyond the traditional realm of health care, they substantially influence health, health behaviors, and health care access and navigation. Frameworks, such as Healthy People 2030, that organize SDOH into separate domains can inform efforts to measure and address them. Healthy People 2030 organizes SDOH according to five domains: economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context (ODPHP, 2020).

Research into the associations between adverse SDOH and cancer outcomes shows that people living in areas with fewer resources have lower screening rates, and those who live with financial insecurity and/or belong to historically marginalized groups experience substantial challenges in accessing health care (Islami et al., 2022). Adverse SDOH can manifest as food insecurity, lack of transportation, and social isolation. Individuals with these social needs fare worse across the cancer care continuum, from prevention to detection, diagnosis, survivorship, and end-of-life care (Tucker-Seeley, 2021), and research has shown that SDOH related to premature aging can have a particularly significant impact on mortality (Brady et al., 2023; Mode et al., 2016; NASEM, 2020).

___________________

10 Social risks are “specific adverse social conditions associated with poor health, such as social isolation or housing instability” (Alderwick and Gottlieb, 2019).

11 Social needs are “self-reported patient social care needs that are impacting the patient’s health, ability to participate in research, and how the patient is navigating cancer care” (Tucker-Seeley and Shastri, 2022).

Tucker-Seeley noted several recent efforts to address the links between SDOH and patients’ social needs, health, and health care-related outcomes, such as the consensus report Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health (NASEM, 2019). The report examined opportunities to integrate services to address social needs into health care delivery and highlighted potential actions to describe and assist with social needs, adjust clinical care to accommodate social needs, and align health care delivery with other community resources. Tucker-Seeley also pointed to another study that suggested methods to screen patients for social needs, navigate patients to appropriate services, and evaluate the impacts on patient outcomes (Taira et al., 2023).

Tucker-Seeley noted that programs to address social needs can be helpful if they include strategies to ensure that efforts are consistent and sustainable. However, he cautioned that they do not typically address systemic conditions that lie outside the realm of health care but are nevertheless relevant to disease risk (Castrucci and Auerbach, 2019). “Health care navigators and similar enhancements to health care can’t actually change the availability of resources in the community,” he stated. “They can’t raise the minimum wage, increase the availability of paid sick leave, or improve the quality of our education system. These are the systemic changes that are necessary to truly address the root causes of poor health.”

Financing efforts to address social needs presents another challenge. Tucker-Seeley suggested greater use of Z codes from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10)12 that are relevant for capturing SDOH. He noted that while Z codes can also enhance clinicians’ and health care systems’ quality improvement initiatives through improved data collection and analysis (CMS, 2023), they are underused, and payment pathways are unclear (Maksut et al., 2021).

Tucker-Seeley explained that more work is needed to implement standardized, well-resourced, sustainable interventions for the communities that need them most. To create fair and just opportunities for people to be as healthy as possible and access high-quality health care, he urged a focus on reimagining and implementing multi-sectoral collaborations that serve organizations, patients, and families and inviting input from patients, clinicians, payers, and social service and community-based organizations (Tucker-Seeley and Shastri, 2022). He challenged workshop participants to consider what tools an equitable cancer care delivery system needs so that patients and families come to expect—and receive—the best quality care.

___________________

12 See https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/Z00-Z99 (accessed June 28, 2024).

Connecting Social Determinants of Health with Cancer Risk and Outcomes

Lauren McCullough, associate professor of epidemiology at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, pointed out that the common throughline for all social inequities is the centuries of economic inequities that marginalized populations have suffered and that SDOH do not just happen but are caused by upstream social and institutional inequities.

The historical practice of mortgage and housing discrimination known as “redlining” provides one example. The downstream consequences include urban neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty whose residents experience disparities in generational wealth, income, and education; inequities in health care access; and poorer health outcomes (Swope et al., 2022). Redlining has also contributed to residents’ increased exposure to environmental toxins in the air, soil, or water—which can cause molecular changes that have been linked to cancer and are known to affect children as early as in utero (Luo et al., 2017).

McCullough also highlighted how a person’s living environment can contribute to molecular changes linked with racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in the incidence and prognosis of obesity-related cancers. She noted that among women, 8 of the top 10 cancer mortality disparities are related to obesity. Obesity is especially prevalent among Black women (OMH, 2022), and they experience disparities in cancer incidence and prognosis compared with non-Black, non-obese people (ACS, 2022). McCullough noted that 95 percent of excess cancer deaths among Black women compared to White women are attributed to three obesity-related cancers (ACS, 2022). Obesity has other consequences that worsen health outcomes and increase cancer incidence, including metabolic dysfunction, insulin and glucose increases, changes in inflammation or immune function, and oxidative stress (Devericks et al., 2022; Lynch et al., 2010). McCullough added that among patients diagnosed with breast cancer, obesity is associated with diagnosis at a later stage; more aggressive subtypes; higher mortality rates; and poor treatment outcomes due to suboptimal dosing, comorbidities, and lower rates of treatment adherence (Matthews and Thompson, 2016; Pierobon and Frankenfeld, 2013; Ross et al., 2019).

Noting that the relationships between SDOH and health are complex, McCullough pointed to studies that show the health disparities gap between Black women and White women living in better-resourced neighborhoods is actually greater than the gap between Black women and White women living in less-resourced neighborhoods, highlighting the influence of structural racism and discrimination, which affect historically marginalized groups and create social isolation and stress, leading to inflammation, hormonal and epi-

genetic changes, and accelerated aging (Collin et al., 2019; Lord et al., 2023). She stressed that the effects of structural racism and discrimination are also transgenerational. “It didn’t just start with you,” McCullough said. “It was your parents and your grandparents and their ancestors […] this can be passed from generation to generation.”

McCullough said that the interactions between direct and indirect effects on biology can make the consequences of SDOH difficult to quantify. However, researchers have been able to pinpoint certain SDOH effects on biology, such as associations with deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) methylome13 perturbations in women with breast cancer, development of late-stage disease, and development of cancer subtypes, with SDOH such as college graduation rates, job density,14 and contemporary mortgage discrimination (Do et al., 2020; Gohar et al., 2022; Miller-Kleinhenz et al., 2023, 2024). To inform successful interventions, she emphasized the importance of considering the scientific evidence and individual SDOH, such as health care access. While research into the relationship between SDOH and carcinogenic processes is growing, she added that more work is necessary to improve health equity, especially research that extends the focus beyond neighborhoods, epigenetics, and biological aging (Saini et al., 2019).

McCullough offered three suggestions for interventions to improve health equity. First, she said that it is important for the medical community to repair trust among marginalized communities and increase their engagement—and biological sample size in clinical studies—by acknowledging and validating systemic challenges that have prevented their inclusion in the past. Second, she suggested that researchers can work to improve SDOH metrics, noting that current metrics or indices are overlapping, do not clearly distinguish between SDOH elements, and may fail to capture positive elements, such as social connectedness or resilience. Finally, McCullough called for improved collaboration among researchers with expertise in basic science, population science, environmental science, and other disciplines to advance health equity.

EMERGING RESEARCH ON POTENTIAL BIOMARKERS RELEVANT TO SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Recent research has shed new light on the complex interaction of SDOH, cancer risks, and treatment outcomes. Several speakers described some of these

___________________

13 DNA methylation is an epigenetic process that regulates the transcription of DNA segments. The DNA methylome is a record of DNA methylation in an organism (Pelizzola and Ecker, 2011).

14 Job density is the number of jobs per square mile. See https://www.opportunityatlas.org/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

emerging findings and discussed how contextualizing cancer within a patient’s ancestry, cultural background, social and economic environment, and lived experiences can lead to better cancer prevention strategies, earlier detection, and personalized treatment decisions. They pointed to potential biomarkers that could be used to measure the biological impacts of SDOH, along with challenges and opportunities in incorporating these measures into care pathways through biomarker testing.

As the research community continues to identify and refine biological markers of SDOH, Lawrence Shulman, director of the Center for Global Cancer Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, urged participants to keep in mind the interconnected nature of factors such as poverty, geography, obesity, and smoking. “They’re not individual, unconnected factors,” he said, “Much of the research that we do is very focused on one factor or another, but we can’t lose sight of the fact that they are, in fact, all interrelated.”

Examining the Interplay of Place, Space, and Ancestry

Clayton Yates, the John R. Lewis Professor of Pathology, Oncology, and Urology at Johns Hopkins University, discussed the Transatlantic Prostate Cancer Consortium,15 which was established to address the globally disproportionate burden of prostate cancer among Black men. Yates explained that the network of cohort participants and collection sites in Western Africa has enabled participation in international prostate research collaborations, such as the International Registry for Men with Advanced Prostate Cancer (Mucci et al., 2022). This registry is collecting information and blood samples to help understand what care strategies offer the best outcomes for men with advanced prostate cancer.

Yates and colleagues are working to identify molecular markers correlated with disparities in cancer outcomes. He said their research has identified a tumor-suppressive signature that was more common among men of African ancestry, who also have a lower survival rate compared to those with European ancestry (Minas et al., 2022). To gain more insight into the links between ancestry and cancer outcomes, Yates said, transcriptomic data analyses were conducted to identify which genes were expressed in samples from patients of European American, African American, or native African (Nigerian) ancestry (White et al., 2022). Yates noted that this study had the most comprehensive characterization of the prostate cancer exome16 among Nigerian men and found that they had a different transcriptional profile. This discovery guided

___________________

15 See https://thecaptc.org (accessed September 6, 2024).

16 The exome is the protein-coding portion of the genome. See https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Exome (accessed July 11, 2024).

more in-depth analyses comparing prostate cancer signatures among African American, Nigerian, and European men. At a cell-population level, they noted differences in immune cell populations between African American and European American men with prostate cancer. Additionally, Yates said they found that the tumors from African American men were enriched for interferon-expressing cells, making them more difficult to treat (Elhussin et al., 2023). Yates said additional analyses were conducted to identify potential gene targets responsible for the observed inflammatory signature, which provided a link between the expression of different genes and the resulting tumor-level differences in immune response in patients of different ancestries. Yates said that these research approaches identified potential biomarkers that might not have been obvious without a large African cohort and could inform future clinical therapies, including personalized treatment approaches for native African and African American men with prostate cancer.

Noting that White populations living in rural areas are three times more likely than any group living in urban areas to have poor outcomes from lung cancer, Robert A. Winn, director and Lipman Chair in Oncology at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center, pointed out that disparities between rural and urban populations illustrate another aspect of how place and space influence health.

Genomic Pathways Connecting Exposures with Health Outcomes

Articulating an overarching goal for “the right patient to receive the right test and the right treatment at the right time for the right price,” Ruth Carlos, professor of radiology at the University of Michigan, said that accomplishing this vision may require viewing SDOH in a more nuanced way that incorporates a holistic “society to cells to outcomes” approach.

Exogenous and endogenous stressors induce physiological reactions that affect cell function and disease development, she explained. The physiology of scarcity—whether of time, food, or other resources—also induces biological and psychological effects and can have a negative impact on downstream disparities and health, she explained.

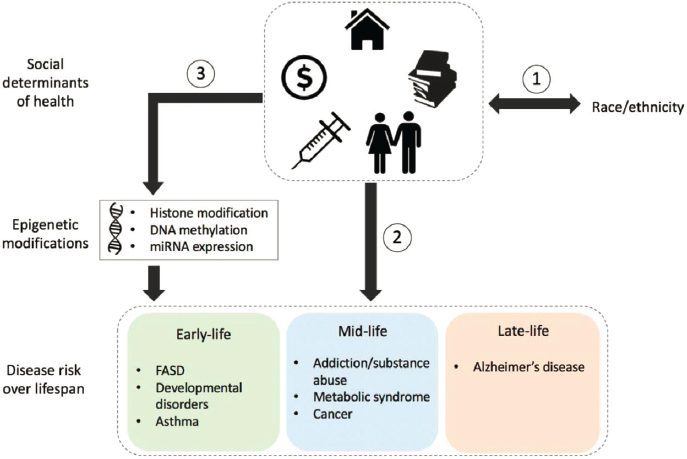

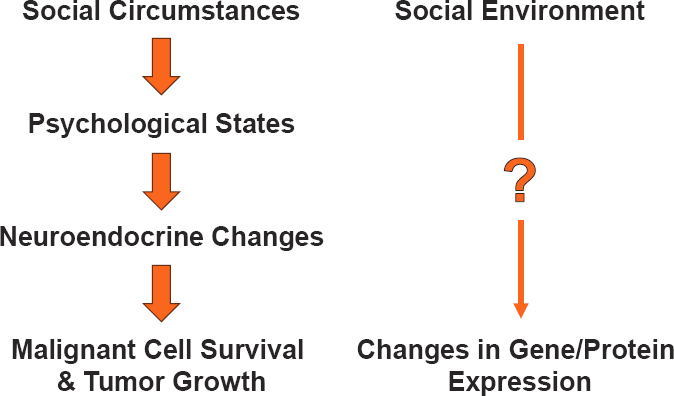

Research has linked SDOH with clinical outcomes, Carlos stated, but the pathways through which the upstream social context creates downstream health outcomes are still largely unknown (Carlos et al., 2022). Potential mechanisms include genomic and epigenomic changes, peri-tumor17 environmental effects, and inflammation from stress responses. Evidence supporting these mechanisms includes a study that modeled how inequity in

___________________

17 The peri-tumor is the “microenvironment at the interface between healthy and malignant tissue” (Zhang et al., 2023).

NOTE: DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid; FASD = fetal alcohol spectrum disorders; miRNA = microRNA.

SOURCES: Carlos presentation, March 20, 2024; Mancilla et al., 2020. CC BY 4.0.

the social environment promotes epigenetic changes that can last from early childhood into successive generations, pointing to the potential for the heritability of social trauma (see Figure 2) (Mancilla et al., 2020); a study that linked paternal SDOH and epigenetic changes with obesity rates of offspring (Milliken-Smith and Potter, 2021); and a study that found an association of noise and air pollution with epigenetic changes linked to cancer development and regulation (Eze et al., 2020).

Although it may be impossible to undo an environmental exposure, Carlos noted that some SDOH and the conserved transcriptional responses to adversity (CTRA)18 they induce are reversible. For example, the negative effects of social isolation, which is correlated with worse health outcomes, could be ameliorated through social, pharmacological, or behavioral interventions (Antoni and Dhabhar, 2019; Cacioppo et al., 2015; Knight et al., 2019). In addition, some CTRA are associated with improved well-being, presenting

___________________

18 Conserved transcriptional responses to adversity is a sustained change in immune cell gene expression profiles in response to environmental conditions (Cole, 2019).

an opportunity to look beyond social risks and focus on social resilience, which Carlos said has been an understudied part of the social context (Boyle et al., 2019; Fredrickson et al., 2015). She pointed out that it is also possible that CTRA-related gene expression could improve people’s ability to manage social stress through enhanced wariness or hypervigilance, she said (Cole, 2014).

Carlos noted the potential ethical dilemmas inherent in interventions that target the genetic effectors of SDOH to solve problems that have been collectively imposed on a specific group of people. However, she emphasized that social genetics, when appropriately aligned with policy and regulations that do not further burden populations, can offer a pathway to advance health equity.

Characterizing Cancer Subtypes and Social Determinants of Health with Population-Based Research

Victoria Bae-Jump, professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, discussed how population-based research approaches can help uncover the relationships between SDOH and patterns in cancer subtypes. Her research focuses on endometrial cancer, the fourth most common cancer among U.S. women (Siegel et al., 2024). Both the frequency and mortality rate of endometrial cancer are rising (Siegel et al., 2024; Ward et al., 2019), trends that researchers have linked with increasing rates of obesity, diabetes, and insulin resistance—known risk factors for this cancer type—as well as with an unexplained rise in more aggressive subtypes (Chia et al., 2007; Siegel et al., 2024).

Roy Jensen, director of The University of Kansas Cancer Center, agreed with Bae-Jump on the strong evidence for an association between endometrial cancer and obesity but noted that most of the biological research on cancer and obesity focuses on the tumor microenvironment and its adjacent adipose cells, which raises questions about the mechanism for this association because no adipose cells are near the endometrium. Bae-Jump stated that although the specific mechanisms are still being investigated, researchers hypothesize that obesity may create circulating signals that alter systemic factors in the uterus and lead to endometrial cancer.

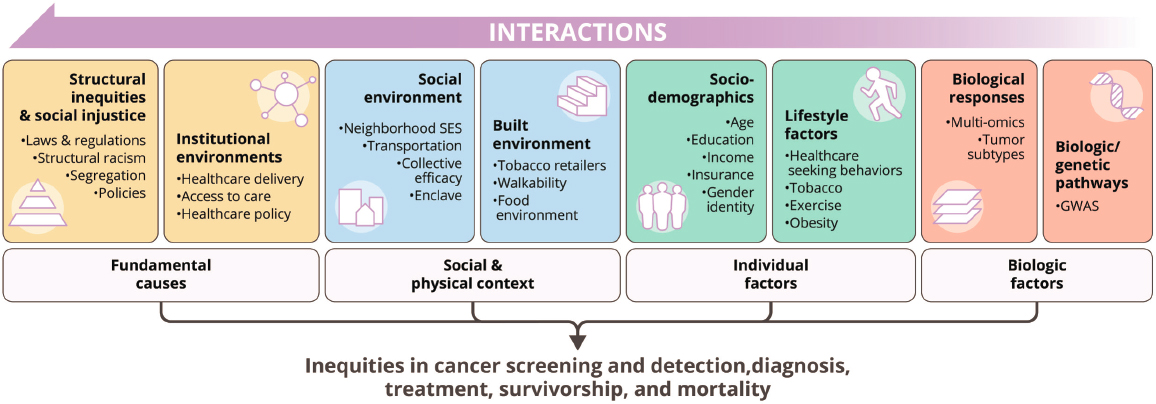

Bae-Jump described significant racial disparities for endometrial cancer; Black and Hispanic women have higher mortality rates, increasing incidence rates, and lower 5-year survival rates than White women (Cote et al., 2015; Siegel et al., 2022). While the exact drivers of these racial disparities are unclear, Bae-Jump posited that they are likely influenced by multiple factors (see Figure 3), from historical structural and institutional inequities to SDOH, and known and unknown social and biological factors that culminate in inequities in cancer screening, detection, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, and mortality (Warnecke et al., 2008).

NOTE: GWAS = genome-wide association studies.

SOURCES: Bae-Jump presentation, March 20, 2024; The “Cell to Society” model created by the UNC Lineberger Cancer Center, adapted from Warnecke et al., 2008.

Historically, researchers focused on two broad subtypes of endometrial cancer. Type 1 was more common and treatable, and Type 2 was less common overall but more common in Black women, more aggressive, and associated with lower survival rates (Fowler and Mutch, 2008). With further genomic characterization of tumors through The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) program, researchers identified four distinct molecular subtypes, each with different treatment pathways and survival rates but all with poorer health outcomes for Black women (who were not well represented in TCGA, Bae-Jump noted) (Dubil et al., 2018; Kandoth et al., 2013).

Determining which molecular subtype of endometrial cancer a patient has is critical to assigning the appropriate therapy. Recent research has shown that Black patients develop more aggressive subtypes and have worse progression and outcomes with all subtypes (Weigelt et al., 2023). The reason for these differences remains unclear. A significant challenge in endometrial cancer disparities research, Bae-Jump noted, is the lack of prospective population-based epidemiological studies that link endometrial cancer subtype with race, obesity, related comorbidities, SDOH, care access, and treatment offerings. Other challenges include a dearth of endometrial cancer samples from Black women to conduct large-scale molecular profiling studies and a limited understanding of how obesity and its related comorbidities affect endometrial cancer progression and treatment in Black women, she said.

Bae-Jump highlighted ways that the Carolina Endometrial Cancer Study (CECS) could help to answer some of these questions. CECS is a population-based prospective study of nearly 2,000 patients with endometrial cancer with the goal of uncovering how epidemiological factors, SDOH and upstream drivers, and tumor biology contribute to racial health disparities. “As we know, these factors have been looked at in their individual silos but really haven’t been brought together in one study,” Bae-Jump said, noting that the results could inform social, behavioral, and biological interventions.

Extracellular Vesicles and Epigenetic Aging

Michele Evans, deputy scientific director of the National Institute on Aging, discussed insights from investigations of the biologic pathways through which SDOH create health disparities. These investigations are based on data from Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Lifespan (HANDLS), an interdisciplinary, community-based, longitudinal epidemiologic study of race, SES, and age-associated health disparities among nearly 4,000 Black and White adults across Baltimore (Evans et al., 2010).19

___________________

19 See https://handls.nih.gov (accessed June 20, 2024).

Describing SDOH as agents that change molecular and biological pathways, Evans explained that they create biomarkers such as inflammatory proteins, extracellular vesicles (EVs),20 DNA methylation, and circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA,21 which are associated with accelerated aging and health disparities. She described the measurement of these biomarkers as “liquid biopsies” that could potentially be used to aid early detection and inform treatment selection and prognosis. She noted that researchers are studying how SDOH influence these biomarkers (Mirza et al., 2023).

Studying EVs could also elucidate some of the molecular changes that may lead to cancer development. EVs mediate intracellular communication and contain various forms of ribonucleic acid, DNA, protein, and lipids (Noren Hooten and Evans, 2020). Mitochondrial DNA could be an important biomarker of health disparities, Evans noted, as it is released by cells under stresses associated with SDOH, cancer, and other chronic inflammatory diseases (Lazo et al., 2021). Her team’s research into EVs, inflammatory proteins, and poverty revealed that people in worse health, specifically men living below the poverty line, had higher levels of mitochondrial DNA and inflammatory proteins in their EVs (Byappanahalli et al., 2023). Surprisingly, the researchers did not find expected associations with race, which Evans said suggests that ancestry and genomic variation may be more important factors in health and biomarker differences than race (Byappanahalli et al., 2024; Morning, 2017; Wallace, 2012, 2013).

Another important factor in health and biomarker differences is epigenetic age acceleration, which is similar to weathering22 and can be studied via DNA methylation (Brown, 2015). A study of 19 biomarkers of organ system integrity in the HANDLS cohort found that White people living below the poverty level and Black people at all income levels showed accelerated epigenetic aging (Shen et al., 2023). This result, Evans said, “hammers home the effects of race-related stressors that lead to poor health and negative health outcomes.”

___________________

20 Extracellular vesicles are small, membranous fluid-filled sacs that help move substances into and out of cells and are involved in many pathological physiological processes (van Niel et al., 2018).

21 Circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA are small segments of mitochondrial DNA that are released by stressed or damaged cells (Lazo et al., 2021). Mitochondrial DNA is the genetic material of the mitochondria, which produce energy for the cell. See https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Mitochondrial-DNA (accessed June 30, 2024).

22 The weathering hypothesis states that “the health of African American women may begin to deteriorate in early adulthood as a physical consequence of cumulative socioeconomic disadvantage” (Geronimus, 1992).

Stress and Allostatic Load

Several speakers highlighted opportunities to measure and understand the relationship between social stressors and cancer by focusing on allostatic load, which reflects the cumulative effects of chronic stress on the body.

Samilia Obeng-Gyasi, associate professor of surgery at The Ohio State University, investigates the mechanistic pathways that link socio-environmental factors, such as low SES or high rates of social isolation, with breast cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2019; Bower et al., 2018; Ramsey et al., 2016). She discussed how the conceptual frameworks of ecosocial theory and weathering describe how these factors are internalized.

Ecosocial theory proposes that the world one lives in can become physically internalized. Its components include embodiment (how one’s body internalizes socio-environmental factors), embodiment pathways (internal biological or environmental mechanisms), and the interplay between structural and intermediary health determinants (such as governmental policy, the social construct of race or gender, living and working conditions, and the health care system) and disease exposure, susceptibility, and resistance (Krieger, 2001b, 2012).

Building on Evans’ discussion, Obeng-Gyasi defined weathering as the idea that adverse health outcomes and early health deterioration, for Black women in particular, stem from chronic exposure to racism, sexism, and classism (Geronimus, 1992). For example, African immigrant women have substantially better birth outcomes than U.S.-born women who are racialized as Black, despite being of similar genetic background (Agbemenu et al., 2019). Obeng-Gyasi explained that weathering becomes embodied through stress pathways, which are biological responses to stressful socio-environmental factors, such as social isolation or financial insecurity, and have multiple overlapping physiological and molecular impacts (Antoni and Dhabhar, 2019; Cole, 2013; Thames et al., 2019).

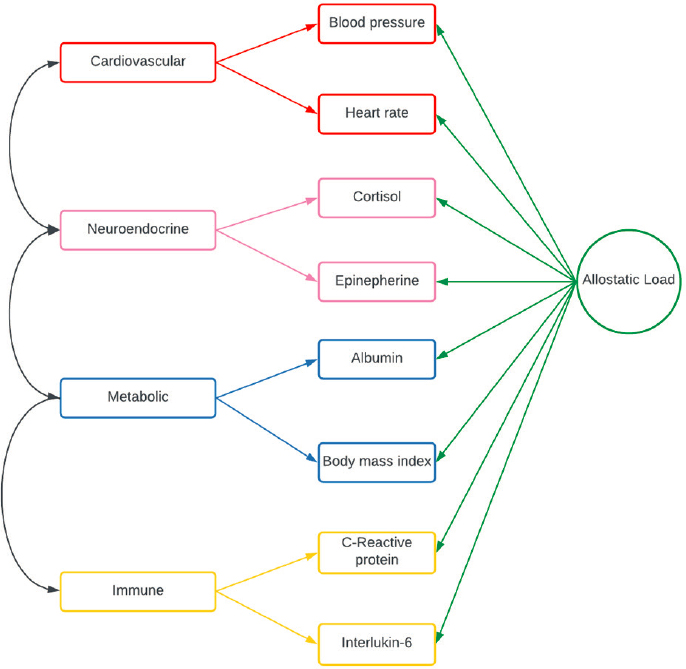

Allostatic load reflects the physiological and immune dysregulation that occurs with exposure to repeated stress events, failure to adapt to repeated stressors, failure to end a stress response, and inadequate release of stress hormones (IOM, 2001). Obeng-Gyasi described how allostatic load can be measured through biomarkers of primary mediators, such as cortisol or epinephrine, or their secondary and tertiary outcomes, such as high blood pressure or diabetes (see Figure 4) (Duong et al., 2017; Seeman et al., 1997).

High allostatic load can lead to permanent biological changes, is associated with poor health outcomes (Mathew et al., 2021; Rodriquez et al., 2019; Wiley et al., 2016), and appears to affect every part of the cancer continuum, from initiation to progression, treatment tolerability, metastasis, and mortality, Obeng-Gyasi said. Studies have shown that women with breast cancer and high allostatic loads—whether related to residential segregation, limited eco-

SOURCES: Obeng-Gyasi presentation, March 20, 2024; Wiley et al., 2016.

nomic opportunities or services, or lower SES—had more comorbidities, a higher incidence of triple-negative breast cancer, and worse all-cause mortality rate; they were also more likely to be Black, enrolled in Medicaid, and unmarried (Chen et al., 2024a, 2024b; Obeng-Gyasi et al., 2023).

Adana Llanos, associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University, described how research is increasingly connecting higher levels of allostatic load with increased risk of more aggressive tumors and a lower quality of life (Guan et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024; Xing et al., 2020a, 2020b). Her research team has demonstrated that living in areas of neighborhood divestment or redlining is associated with being underinsured and an increased risk of late-stage diagnosis, higher-grade tumors, greater incidence of triple-negative breast cancer, and lower breast cancer survival rates (Chen et al., 2024a; Plascak et

al., 2022). As a possible explanation, Llanos said that the weathering many Black women experience from chronic psychological stress results in high allostatic loads, measurable even in childhood and adolescence (Geronimus, 1992; Rainisch and Upchurch, 2013). Llanos noted that this could contribute to the higher breast cancer incidence among Black women compared with White women (Geronimus et al., 2006; Parente et al., 2013). Because both Black women and Black men are likely to have higher allostatic loads, Llanos urged a focus on developing early-life interventions that could help to reduce chronic stress before the cumulative impacts begin to build.

Researchers are investigating the feasibility of developing a standardized, validated method for calculating allostatic load scores to better understand cancer epidemiology and inequities, Llanos said. Studying the combined impact of allostatic load and neighborhood context on breast cancer could also shed light on biological mechanisms caused by persistent inequities, she explained, suggesting that incorporating SDOH could provide insights at multiple levels, from biology and disease etiology23 to improve public health (Kehm et al., 2022; McDade and Harris, 2022; Warnecke et al., 2008). “Given these multidimensional, multilevel factors, we need multilevel, multidimensional approaches,” Llanos stated.

Richard Schilsky, professor emeritus at the University of Chicago, cautioned that allostatic load is multidimensional and reflects many different processes and that its use as a biomarker for clinical practice should be contingent on appropriate validation and context. Obeng-Gyasi suggested that it could be incorporated into the clinical setting, noting that recent research into the feasibility of biological interventions to improve health outcomes by reducing a patient’s allostatic load has presented promising early results (OSUCCC, 2022). However, she cautioned that it is important to be aware that some treatment modalities, such as surgery or chemotherapy, can increase allostatic load. Shulman added that for those who already experience multiple stresses, a cancer diagnosis often leads to further stress.

Gerson stated that Black people are more likely to live with multiple overlapping social stressors and that separating ethnicity, race, or ancestry from these socioeconomic disease drivers is often challenging for researchers. He added that it is also a challenge to explain these drivers to the public. Highlighting how the embodiment of historical trauma—the biological effects of stress and weathering—becomes measurable through allostatic load, Scarlett Lin Gomez, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco, underscored the importance of studies examining different social epigenetic pathways (Carlos et al., 2022).

___________________

23 Etiology is the “cause or causes of a disease.” See https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002356.htm (accessed June 30, 2024).

Suzanne Conzen, chief of the division of hematology and oncology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, discussed emerging laboratory research on the relationship between social stressors and breast cancer outcomes. Conzen noted that in vitro research demonstrated that glucocorticoid receptor tumor signaling activation can promote cancer cell survival and other pro-oncogenic functions (Moran et al., 2000). Additionally, a meta-analysis found that high glucocorticoid receptor expression in tumor samples from patients with early-stage breast cancer was correlated with worse outcomes for women with estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer (Pan et al., 2011). Conzen and colleagues conducted research to see if the physiological effects of social stressors in rodents play a role in cancer biology (Antoni et al., 2006; McClintock et al., 2005; Volden and Conzen, 2013) (see Figure 5).

The first model Conzen discussed involved assessing social stressors in genetically identical female mice with susceptibility to triple-negative breast cancer. Mice were maintained in either group housing or social isolation from weaning through 15 weeks of age (i.e., through puberty and young adulthood) and examined them for behavioral differences and endocrine responses when restrained (emulating a burrow collapse, a common stressful situation in the wild). Socially isolated mice had higher glucocorticoid levels in response to gentle restraint, consistent with a maladaptive stress response (Williams et al.,

SOURCES: Conzen presentation, March 20, 2024; adapted from Gehlert et al., 2010. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com.

2009). Chronic isolation was also associated with increased triple-negative breast cancer tumor burden in this transgenic mouse model (Williams et al., 2009).

The second model Conzen discussed was designed to assess the development of spontaneous tumors in female rats experiencing social isolation versus grouped housing, again initiated from weaning through puberty and young adulthood. Social isolation was associated with earlier-onset and more aggressive breast cancer compared to rats who were in group housing from birth (Hermes et al., 2009). The researchers also found that social isolation through puberty and early adulthood correlated with impaired mammary gland development, corresponding to higher corticosterone (a glucocorticoid) reactivity (Johnson et al., 2018).

Conzen concluded that this research demonstrates that chronic social isolation versus social support can be modeled in animals to study the impact on cancer in a laboratory setting. The physiologic stress response to social isolation includes increased stress hormone production, accompanied by behavioral vigilance. Following chronic stress exposure (i.e., social isolation during puberty and young adulthood) in genetically predisposed mice and rats, breast tumors in these laboratory animal models appear earlier and are more aggressive. Additionally, Conzen said that the effects of chronic stress in late puberty/early adulthood need to be studied further to assess the impact of mammary gland development on breast cancer risk. She noted that ongoing research will assess if the biological effects of social isolation (as a model of early life stressors) can be mitigated by reintroducing group housing during puberty and young adulthood in female rats.

Equity Implications of Biomarker Testing

Defining biomarkers as measurement variables associated with disease outcomes, Gregory Vidal, medical oncologist at West Cancer Center, discussed how biomarker testing (or a lack of it) can influence cancer care and outcomes, with implications for health equity and health disparities. Certain biomarkers can be targeted with drugs, and many tumor types and mutations are being studied to facilitate the development of new targeted therapies (Hanjie Mo, 2021; Vogelstein et al., 2013). The cost of next-generation sequencing (NGS) of a patient’s DNA to find biomarkers has gone down dramatically,24 Vidal noted, and in many situations, NGS and hereditary germline testing are covered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). This has made it more accessible and affordable for some patients to be tested and more

___________________

24 See https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/DNA-Sequencing-Costs-Data (accessed May 22, 2024).

likely for them to participate in clinical trials that require certain biomarkers (Sheinson et al., 2021a).

Biomarkers can only reduce health disparities if they are implemented equitably, noted Vidal. If certain groups receive less biomarker testing, then it follows that they may be less likely to participate in clinical trials or receive optimal treatment. Not all insurance companies cover biomarker testing, and not all health care organizations can afford to offer it. Despite an overall increase in biomarker testing, one study found that Black patients were being tested at lower rates than White patients for many cancers, which also affected their representation in clinical trials for new therapies (Bruno et al., 2022). Studies have also revealed testing disparities for those who lived in the South, enrolled in Medicaid, or older (Sheinson et al., 2021b).

Investigating these testing inequities further, Vidal and colleagues found that at the practice level, White patients with lung cancer received more timely testing than Black or Latinx patients (Vidal et al., 2023). Many clinicians who see mainly Black or Latinx patients were also less likely to offer testing (Vidal et al., 2024). The same racial disparities are seen in germline testing (Kurian et al., 2023). In response to these findings, Vidal’s clinic mandated that all patients undergoing first-line treatment for metastatic cancer receive NGS. They found that testing and clinical trial participation rates increased because this new policy reduced confusion over who met screening criteria and eliminated the impacts of any clinician bias. The clinic also established a tumor board to recommend clinical trials and treatment decisions to clinicians (VanderWalde et al., 2020). Vidal said that both steps reduced racial disparities, and the clinic now has a much higher percentage of patients who are Black, older, or female enrolled in clinical trials.

Based on these results, Vidal suggested that other institutions create systemic NGS and germline testing plans to take the decision out of the hands of clinicians and reduce the impact of bias (Subbiah and Kurzrock, 2016, 2023) and that continuing medical education focused on NGS could help clinicians become more educated about its usefulness. Gerson added that policies mandating full coverage for biomarker testing could also help to address inequities.

Karriem Watson, chief engagement officer at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) All of Us Research Program,25 highlighted the importance of access to care in influencing many aspects of a person’s cancer trajectory. Where patients live, where they receive their health care, and where clinical trials are undertaken all affect the care they receive. Watson noted that patients who receive care in community clinics are frequently excluded from clinical trials and suggested diversifying where they are conducted. For example, they

___________________

25 See https://allofus.nih.gov (accessed July 11, 2024).

could be expanded to include federally qualified health centers, which care for many underrepresented groups—who have the greatest burden of health disparities. Watson added that, to support equity, it is important for clinical research staff to reflect patient diversity, especially for those with the greatest burden of health disparities.

Andrea Ferris, president and chief executive officer of the LUNGevity Foundation, described how some of these issues are playing out in lung cancer. Lung cancer has been at the forefront of precision medicine, as researchers have pinpointed various disease drivers and developed targeted therapies and care pathways. However, despite the availability of tests to detect the known drivers, Ferris said that precision medicine care pathways are not being implemented effectively or equitably. Many patients are simply not receiving the tests that could inform targeted treatment decisions. This may be due to a number of factors, including reimbursement policy, overwhelmed clinicians, and lack of effective strategies for incorporating these tests into clinical workflows. Ferris expressed doubt that new knowledge generated through research will have a real impact on patients without better implementation strategies.

Building on these points in the context of research aimed at identifying biomarkers relevant to SDOH, Christopher Cogle, professor of medicine at the University of Florida and chief medical officer for Florida Medicaid, cautioned that laboratory tests are useful only if they inform interventions. Given the amount of evidence already available, he asked, “Why do we need a gene expression [test] to tell us that we need to focus on social needs?” Cogle noted that biomarker testing should not be used to validate socioeconomic issues, rather they should be used as tools to inform policy to address socioeconomic needs. He cautioned that it is essential to ensure investments in biomarker testing do not divert attention and resources from necessary social reforms. Cogle posited that while currently SDOH biomarkers are not meaningfully informing care, they may do so in the future. Cogle agreed with other speakers who noted that frequent surveys could be burdensome for patients, but he expressed skepticism that replacing in-person conversations about social needs with blood tests or cheek swabs—which may be seen as easier for many clinicians—would actually benefit patients. He suggested that an area with more promise may be public health surveillance. For example, he suggested that strategies such as testing sewage or air pollution levels could be leveraged to guide precision social health initiatives that are informed by biomedical evidence and targeted to areas with the greatest need.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR HEALTH CARE SYSTEMS TO ADDRESS SOCIAL RISK FACTORS

Many SDOH and health-related social needs extend beyond the areas that have traditionally been within the purview of health care systems. Several participants discussed the relevance of SDOH to care delivery, gaps in current practice that can lead to inadequate attention to social risk factors, and opportunities and considerations to better integrate SDOH into the cancer care continuum.

Recognizing the Influence of Upstream Factors on Health

Throughout the workshop, many participants highlighted the importance of upstream factors affecting a person’s health and the care they receive. Even as researchers elucidate the downstream biological mechanisms that connect SDOH with health outcomes—and potentially find ways to target those mechanisms to intervene—a number of speakers cautioned that it remains important to address the root causes of the inequities that lead to health disparities. Laura Gottlieb, professor of family community medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, pointed out that even if scientists invented a pill that blocks the biological effects of racism, including the allostatic loads that worsen cancer outcomes, it would not address the social needs patients and communities face. “This is an ethical dilemma that I think really challenges the entire research endeavor in this space or around biomedical research. […] All of us have to be grappling with it constantly, and as we do the downstream work, we also have to be doing the upstream work,” Gottlieb said.

Tucker-Seeley pointedly asked, “How much of the causal pathway do we need to explicate before we all believe that systemic racism is the driver that has sorted specific groups into these adverse circumstances, which have detrimental effects on their health?” He added that if racism is a key driver, it may be necessary to explore multilevel, multifactorial interventions—in health care and policy—that address historical harms, dismantle systemic racism, and improve SDOH.

Shulman reiterated that many of the factors that appear to be linked with health disparities (e.g., divested neighborhoods, challenges with health care access, epigenetic changes, and stress responses) are interrelated and stem from economic disparities. Llanos, Robert Hiatt, associate director of population sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, and Olive Mbah, senior health equity scientist at Flatiron Health, added that much of the research examines individual interventions—behavioral, dietary, therapeutic, and so on—that improve outcomes or prevent cancer development but suggested that focusing more on structural drivers at the population level could

yield greater impacts. Llanos suggested that changes to health care reimbursement structures could help to reduce care inequities, and Hiatt pointed to the importance of focusing on alleviating the impacts of persistent poverty. Although many SDOH connected with poverty, such as education, power, privilege, and social connections, cannot be changed quickly, Hiatt posited that income may be uniquely modifiable, noting that his group is studying the impact of policies such as earned income tax credits and basic guaranteed income on cancer rates and outcomes.

Stanley Frencher, medical director of surgical outcomes and quality at Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Hospital, added that there may be ancillary benefits from addressing patients’ social needs, even with little data to suggest it can impact cancer incidence or outcomes. “Even if we haven’t proven today that those things impact their cancer biology or even their cancer outcomes, I would argue they’re just the right thing to do,” he emphasized.

The Role of Trust and Communication

Several participants underscored the role of trust and communication in addressing SDOH and health disparities in research and health care. Beverly Rogers, chief executive officer of From Momma’s House, spoke about her experience as a breast cancer survivor and patient advocate. She described how her interactions with the health care system, as both a patient and a caregiver, have often left her feeling confused and frustrated. Citing patient–clinician communication as a key challenge, Rogers recalled often feeling that her clinicians were not communicating in a way that she was likely to understand. For example, it is well known that stress has a negative impact on health, but that information alone is not actionable. “Everybody tells you; your doctor tells you, your cardiologist tells you, your endocrinologist tells you, stress causes diabetes, stress causes heart problems, stress causes arthritis. I got all of those. So, what are you going to do for me?” Rogers asked. Noting that health care systems are challenging to navigate for many people, but especially older adults, she stressed the need to improve communication and coordination among the full spectrum of clinicians that patients see.

The importance of plain language and making information relevant to people’s lives also extends to researchers. Rogers suggested that researchers could go beyond describing best practices or hosting public listening sessions to engage with communities more meaningfully. She said building trust is essential and suggested that community members will be more willing to answer questions, about their neighborhood environment, for example, if they see a clear value in doing so and the results will apply to their lives and health concerns. Rogers emphasized that researchers and clinicians have a responsibility to use their training to improve people’s lives.

Tucker-Seeley pointed out that some of the health care delivery challenges that Rogers alluded to are solvable. Clinicians are not incentivized to view patients as humans struggling to navigate the complex, unfamiliar health care landscape, which contributes to health and health care disparities. “Ms. Rogers highlighted that she’s not just the arm that you’re using to take blood from. She’s not just this body part that’s being treated for this condition. She’s a whole person,” he stated.

To build better relationships and receive better care, Rogers pointed out that patients would benefit from more time with clinicians. Hughes-Halbert agreed that a lack of time creates missed opportunities to understand nuances in patients’ lives. Brawley noted that administrative realities prevent clinicians from spending more than 20 minutes with each patient and suggested that it could be valuable for people from all facets of the health care system, from clinicians to administrators to payers to CMS, to recognize and understand how their workflow may be contributing to health disparities.

In both health care and research, Winn said that organizations know it is important to build trust in communities, but he suggested that many have failed to examine their own lack of trustworthiness. Gaining trust takes time, and it is important to consistently show up and speak the right language, he said. Gwen Darien, executive vice president at the National Patient Advocate Foundation and a cancer survivor, agreed that access and trust are crucially important in the clinician–patient relationship. “We have to trust patients, patients’ voices, patients’ experiences, and what they think that they need, and not make any assumptions,” she said.

Noting that she regularly hears stories of bias, neglect, mistrust, and inequitable care from Black patients with cancer, Darien suggested that standardizing screening and testing processes, in addition to engaging meaningfully with patients to understand their perspectives, could help to increase access and equity. “This bias and this inequity are just persistent and intractable,” she said. “Making this [screening] the standard of practice for everybody—it would go such a long way towards addressing a number of inequities.”

Integrating Social Determinants of Health into the Care Continuum

Several participants spoke about opportunities for health care systems to systematically assess and attend to patients’ social needs, a goal that Gomez said can also benefit from community-based research and partnerships. Gottlieb described the 5A Framework, which outlines opportunities for health care systems to acknowledge patients’ SDOH and intervene when relevant (NASEM, 2019).

Conceptually, Gottlieb said it is important to recognize that SDOH are part of a broader spectrum of factors that shape individual and com-

munity health, neither good nor bad in and of themselves, and distinct from population health (Alderwick and Gottlieb, 2019). In addition to individual components, SDOH encompass upstream structural drivers, such as institutional policies, and their downstream effects on social risks, assets, and needs (Castrucci and Auerbach, 2019).

The 5A Framework organizes the different activities that fall under social care into five distinct categories. Each serves as an umbrella for many related components that affect health care access and delivery. Gottlieb detailed the three that focus on patients and health care delivery: awareness and identification of social risk factors, assistance to intervene on social risk factors, and adjustments to accommodate care for social risks. The other two categories, alignment of existing resources and advocacy to develop new resources, are more community focused.

Awareness relates to activities or strategies that health care systems employ to collect social information about their patients. These can be patient questionnaires, insurer-based health risk assessments, or analysis of consumer data. Clinicians also employ screening tools, but Gottlieb noted that available tools lack consistency and suggested that it may be helpful to undertake more validity testing and consensus building to determine the most promising tools (SIREN, 2019). Gottlieb noted that technology could help facilitate social risk screening; for example, many electronic health records (EHRs) include social risk dashboards. However, she said that these approaches are underused for SDOH applications and lack the data standardization needed to facilitate meaningful interventions.

Assistance refers to activities health care systems undertake to improve patients’ social context and thus their health and well-being, such as connecting patients with food resources or rent support. To guide and understand the impacts of such efforts, Gottlieb said that it is important to ask whether awareness of social factors contributes to assistance and then whether assistance, in whatever form it may take, leads to actual health improvements. For example, cancer care assistance has emphasized patient navigation but with little research on whether the interventions improve racial health equity outcomes (Korn et al., 2023). In addition, service referrals may not be effective if the services are not actually accessible. “Even if we provide assistance, not everyone gets their need met, in part because […] the effectiveness of referrals depends on the availability of services and decreasing the administrative burden of enrollment and sustaining enrollment,” Gottlieb said, noting the available resources to help researchers better understand these challenges.26,27

___________________

26 See https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2020/scoping-review-and-evidence-map-social-needs-interventions-improve-health-outcomes (accessed May 22, 2024).

27 See https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/tools/evidence-library (accessed May 22, 2024).

Adjustment strategies attempt to use social risk data to inform clinical care decisions. Gottlieb said that these strategies include offering less expensive medicine; reducing the complexity of treatment regimens; providing interpreting services; or offering mobile, evening, or weekend care (Korn et al., 2023). Clinicians often make these adjustments, but implementation has not been systematic or large scale, Gottlieb said, noting that one challenge is that clinicians often do not have access to a patient’s social risk data. Carlos added that downstream effects of SDOH, such as allostatic load, could be used as biomarkers that prompt health care systems to intervene with early-stage supportive potential actions to improve outcomes, such as treatment adherence support.

The final two framework categories, alignment and advocacy, can strengthen the social resources landscape at the community level. To advance these efforts, Gottlieb said that it would be helpful if health care systems collaborated with community advocates to improve social conditions by offering employment, investing resources, and supporting local services and activities.

DATA ISSUES AND GAPS RELEVANT TO SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Appropriately and accurately measuring SDOH is important if scientists and clinicians are to incorporate greater awareness and utility of these factors into cancer research and care. Reflecting on the workshop presentations and discussions, Shulman posited that a shared goal is to identify effective methods for collecting information about SDOH that are relevant to patient experiences and outcomes. Creating a standardized, unified approach across multiple, diverse care sites is a key challenge, Shulman said, and Gomez added that this challenge also extends into the research realm, where harmonizing SDOH measurement tools and factors is important for comparing results across studies. Cathy Bradley, dean of the Colorado School of Public Health, suggested that policies can help to support research into best practices to effectively collect, harmonize, link, and share data from all population groups.

Examples of Social Determinants of Health Screening Tools for Research and Clinical Support

Several speakers described examples of how health systems and research groups have sought to collect and use SDOH information to reduce disparities across the cancer care continuum.

Oluwadamilola Fayanju, chief of the division of breast surgery at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, said that addressing

the unmet social needs of patients with cancer is the best way to reduce cancer treatment disparities, but there are a number of challenges to collecting the data necessary to understand these social needs. Using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s Distress Thermometer and Problem List,28 Fayanju surveyed 1,000 women with breast cancer and found that those whose distress increased over time were more likely to be unmarried or covered through Medicaid; in addition, Black respondents reported lower baseline distress scores, prompting fewer referrals for social services, but experienced less improvement in their distress over time (Fayanju et al., 2019), a disconnect that Fayanju suggested indicates a potential flaw in applying the distress assessment methods across racial or ethnic groups. Fayanju and her team also found that Black patients experienced longer times to their first postdiagnosis evaluation, more practical stressors, and delayed time to treatment, all of which are associated with worse survival rates (Fayanju et al., 2021; Richards et al., 1999).

Noting that oncologists are gatekeepers during key points of a patient’s cancer care journey, Fayanju underscored the importance of timing in terms of identifying and responding to social needs. “If we’re only collecting information about SDOH [or] unmet social needs at the time of first consult, we are already too late,” she said. “By the time someone arrives for her [treatment] visit, a die has been cast. And therefore, we have an opportunity, if not an obligation, to start collecting that data sooner.”