Electronic Surveillance of Railroad-Highway Crossings for Collision Avoidance: State of the Practice (2024)

Chapter: 4 Case Examples

CHAPTER 4

Case Examples

Selected survey respondents expressed willingness to participate in follow-up interviews. Eight case examples are presented in this chapter, which were developed based on information obtained from literature review, survey responses, interview summaries, and additional related information searches. The case examples are primarily from implementations at light rail transit (LRT) and commuter rail crossings. The first example is devoted to electronic surveillance of rail crossings for freight railroads for better detection and communication of traffic operation information impacted by train events and its value for traffic management and emergency services. There is anecdotal evidence of unsafe driver behaviors when rail crossings are blocked for an extended period. Some corridors are shared by freight rail, but they operate on different tracks even though they go through the same rail crossing. One case example is from the United Kingdom for rail crossings owned and operated by Network Rail. In several corridors operated by Network Rail, the track is shared by commuter rail, freight rail, and some even by light rail. The case examples demonstrate electronic surveillance at different scales and for a wide range of applications. There are distinct institutional differences between the settings in the United States and in the United Kingdom.

The information contained in these case examples is intended to illustrate, describe, and compare requirements for electronic surveillance technology applications. All case examples attempt to highlight the implementation and application of surveillance technology.

The format for the case examples is as follows.

Background/Context

The nature and extent of the service, corridor, and rail crossings that the rail transit or commuter rail agency is involved in. In addition, some description of the safety profile of the agency and rail crossings will be discussed.

System and Technologies

The description of the overall system and components of the electronic surveillance established within the agency and at rail crossings is presented. This will include technological, operational, and administrative aspects of the system.

Applications

The various applications of the system will be discussed, with particular emphasis on safety data collection and its use in analyses, metrics, and decision-making. Electronic surveillance applications have been used to collect safety data, identify violations, provide alerts, determine the health of devices, and monitor trespassing, dwellings, suicides, and street blockages.

Implementation and Assessment

Implementation considerations include

- Understanding,

- Standard operating procedures,

- Privacy,

- Storage,

- Communication,

- Image processing,

- Cost,

- Funding,

- Time and training needed,

- Obsolescence and updating, and

- Institutional support.

Assessment should consider

- Accuracy,

- Coverage,

- Reliability and safety of the system and its components,

- Performance measures, and

- Expandability and flexibility.

Lessons Learned for the Future

The lessons learned and best practices resulting from the installation and use of electronic surveillance at the rail crossing will be highlighted so agencies would be able to implement a similar system that is scalable and flexible to their context and needs.

Case 1: TRAINFO

Background/Context

TRAINFO’s system includes trackside sensors to detect and collect train data (freight and passenger trains), cloud-based software to analyze data and produce insights, and application programming interfaces (APIs) to integrate these insights into existing systems. The entire system is installed off rail property and does not require approvals or interfaces with railroad equipment or systems.

System and Technologies

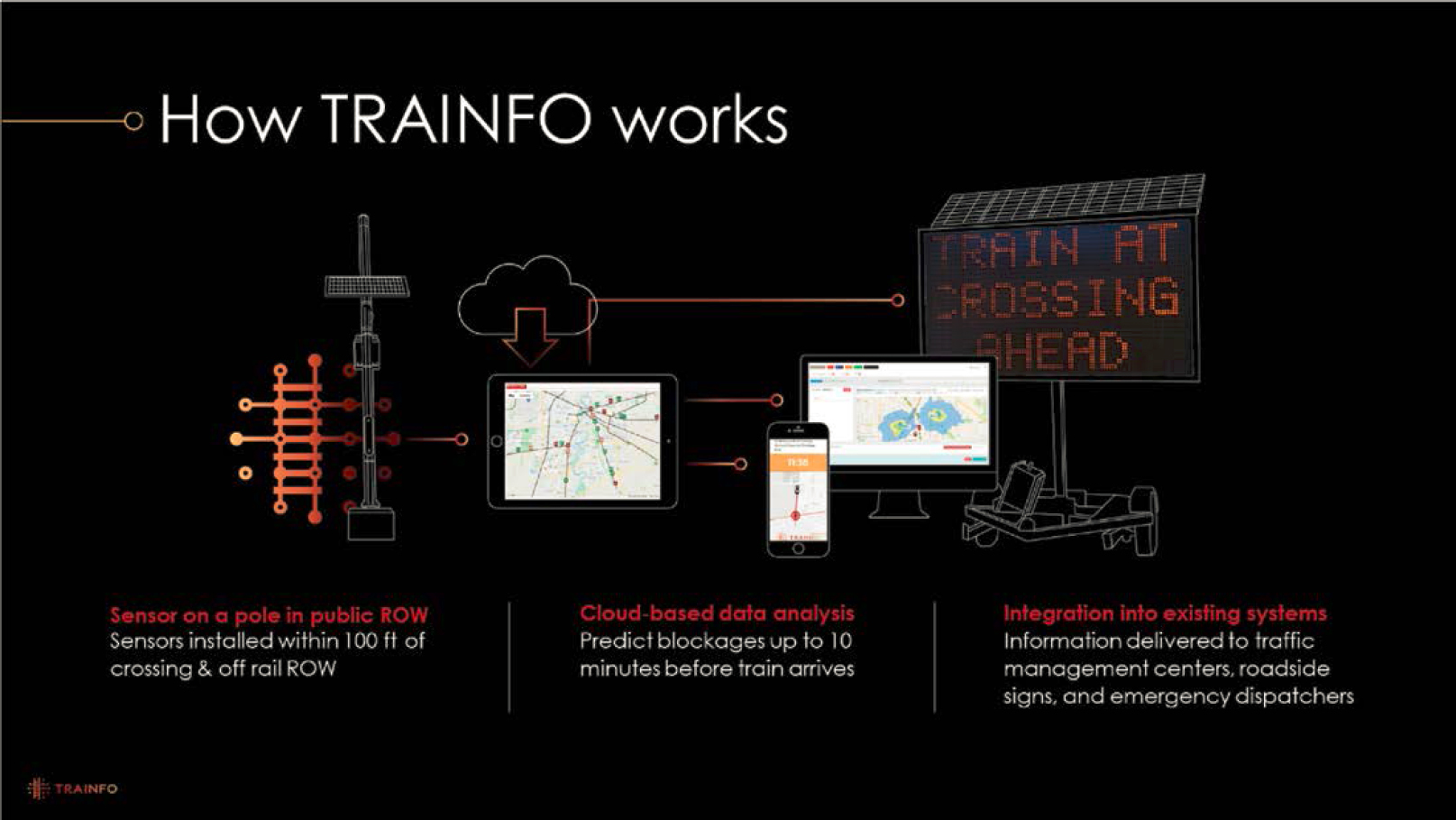

The TRAINFO system (see Figure 12) automatically communicates the event or potential event of a blocked railroad grade crossing to various users. The users include emergency dispatchers and drivers, news media, traffic management systems, and the general public. The users receive information regarding the location, time, and duration of the event or potential event. The system applies multiple technologies to detect the presence of activity on a rail line, transmit detection data to a database, perform data analyses, and communicate the status of grade crossings (blocked, potentially blocked, upcoming blockage, or clear) to assist users in making informed decisions.

TRAINFO’s trackside acoustic sensors detect trains and are installed on poles adjacent to the rail crossing. Sensors can be installed anywhere within 100 feet of the rail crossing and work at

crossings with all active warning devices, including four-quad (4-quadrant) gates. Video cameras can be added if visual features are needed. Sensors are equipped with cellular modems that wirelessly deliver data to the cloud for analysis. Sound signatures are developed to determine train movement characteristics and predict when crossings will be blocked and cleared. TRAINFO can differentiate between passenger trains and freight trains and can classify movements as continuous (i.e., through-movements) or non-continuous (i.e., stopped, shunting, and switching movements). TRAINFO’s software can also integrate traffic data sourced from vehicle probe/global positioning system (GPS) data providers or collected by Bluetooth sensors, to predict travel time delays for motorists up to 10 minutes before the train arrives (see Figure 13). APIs are used to integrate this information into roadside signs, traffic management centers, computer-aided dispatch software, and mobile apps.

Applications

TRAINFO’s system provides live applications and analytical tools for road and transit authorities, emergency service providers, researchers, and policymakers.

Live applications for road and transit authorities: TRAINFO’s real-time and predictive train data are integrated into traveler information systems such as roadside signs and mobile apps to notify road users about blocked crossings. Specifically, drivers receive messages up to 1 mile (or more) before a rail crossing informing them that the crossing is blocked, how much delay to expect, and alternative routes. This information can reduce congestion at rail crossings and enhance safety by discouraging drivers from trying to speed and drive to the crossing in an unsafe manner.

Implementation (City of Chicago): The Midway International Airport in Chicago is surrounded by rail crossings which can create vehicle delays for travelers going to and from the airport. I-55 is an east-west freeway north of the airport and Cicero Avenue, Central Avenue, and Archer Avenue (via Pulaski Road) are three main options that connect I-55 to the airport. Both Central Avenue and Archer Avenue have at-grade rail crossings; Cicero Avenue does not. The City installed TRAINFO’s train detection sensors at the Archer Avenue and Central Avenue crossings and installed Bluetooth sensors at various locations to measure travel time. TRAINFO’s real-time and predictive train information was integrated into two overhead dynamic message signs on I-55 to inform drivers about travel times to the Midway Airport via Cicero Avenue, Central Avenue, and Pulaski Road.

Live applications for emergency service providers: TRAINFO’s real-time and predictive train data are integrated into tactical maps and computer-aided dispatch software. Real-time maps also indicate which crossings are currently blocked by trains and when they will be clear. Emergency dispatchers and call-takers use this information to select vehicles and routes to help first responders avoid delays caused by blocked and occupied crossings.

Implementation (Charleston County): There are 127 at-grade railroad crossings within the Charleston County Consolidated 911 Service Area, which covers Charleston County and portions of Dorchester and Berkeley Counties. The County contains a large conglomerate of railways and hosts the eighth-busiest seaport in the United States, with 2.2 million cargo containers per year. Because of high train volumes, crossings are frequently blocked and occupied, leading to significant first responder delays.

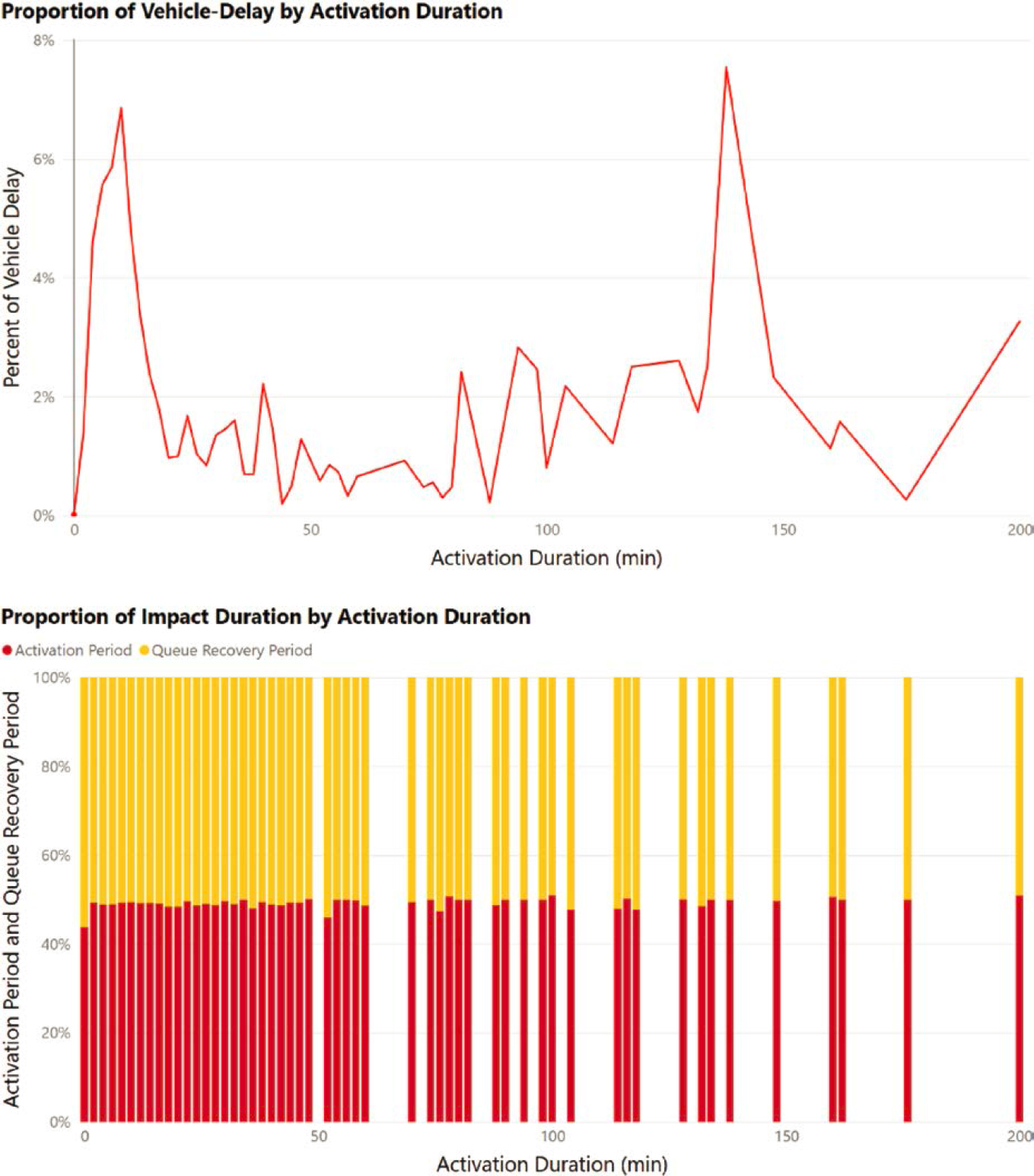

Analytical tools for road and transit authorities: TRAINFO’s historical train data are available through interactive dashboards with maps, graphs, and other visual representations. These dashboards provide trends and detailed statistics regarding blockage frequency and duration, including blockages by time of day, train speed, train length, and many other metrics (see Figure 14). Individual records of each blocked crossing event are available for download and custom analysis. This helps transportation engineers and planners identify and prioritize crossings for improvement, develop strategies for improvement, measure the performance of changes, and support funding applications.

Implementation (Florida Department of Transportation): Train activity along the Florida East Coast Railway, which has a mainline that runs through the Southbank district of Jacksonville, causes traffic congestion and collision risks and blocks access to the Baptist Hospital. Florida DOT implemented TRAINFO’s system to quantify the traffic impacts of this train activity, including installing train sensors at five crossings (San Marco Boulevard, Hendricks Avenue, Prudential Drive, Nira Street, and Atlantic Boulevard) and 12 Bluetooth sensors at various locations.

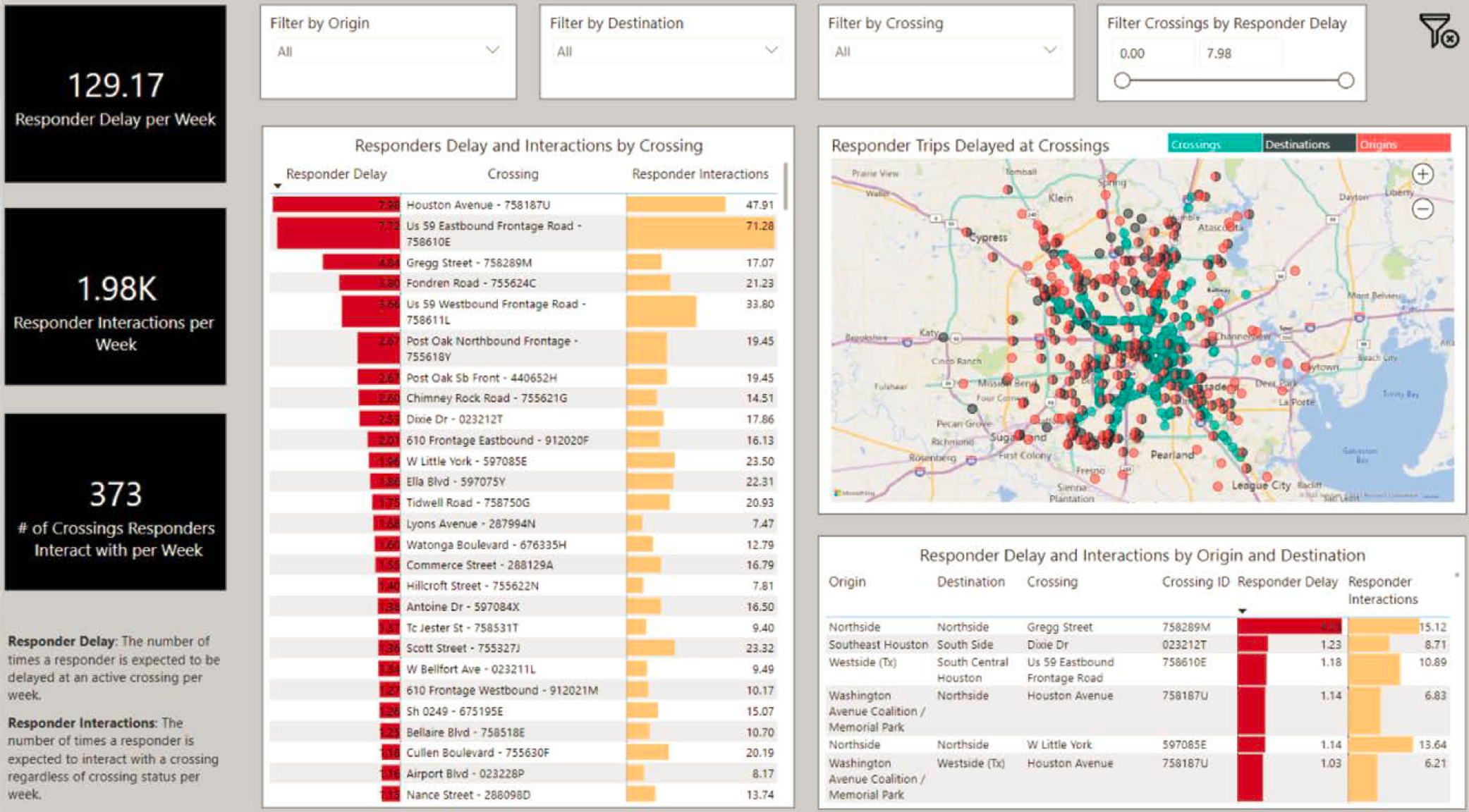

Analytical tools for emergency service providers: TRAINFO’s Emergency Service Risk Model integrates historical 911 call log data with historical train data to assess the risk of blocked crossings on emergency response times. Risk is a function of the probability of an emergency vehicle being delayed by a train and the severity of this delay. Call log data indicates the travel route used by emergency vehicles and TRAINFO’s train data is used to determine which vehicles were impacted by a blocked crossing. The model quantifies how many emergency vehicle trips traveled through railway crossings, how many of these trips encountered a train at the crossing, and how much delay the vehicle experienced.

Implementation (City of Houston): With more than 600 at-grade rail crossings and 8,400 rail crossing blockages per day, the city estimates that 5 million vehicle trips are delayed by trains daily, including significant impacts to emergency services. The City of Houston used TRAINFO’s Emergency Service Risk Model (see Figure 15) to help understand the risk of blocked and occupied rail crossings on first response time. TRAINFO sensors were installed at seven crossing locations and a year of 911 call log data was provided. Figure 15 shows the risk model results. This model quantifies Responder Interactions (defined as the number of times a responder travels over a rail crossing) and Responder Delays (defined as the number of times a responder encounters a train at a rail crossing).

Implementation and Assessment

TRAINFO’s system can be deployed in less than a month, including sensor installation, calibration, and integration into traveler information systems. Critical elements of deployment include poles for sensor installation and access to power. Sensors must be installed on poles within 100 feet of the crossing and can draw power directly from the pole (i.e., light standards, traffic signals, utility poles) or can be equipped with solar panels. All sensors have battery backup supplied to provide up to 3 days of operation.

TRAINFO provides ongoing support for their systems. This includes 24/7 remote monitoring and system health diagnostics regarding power and communications, delivering over-the-air firmware and software updates to sensors to address any issues, conducting detection audits to ensure sensor accuracy and calibration, maintaining the APIs necessary for integration into third-party systems such as signs and traffic management centers, and dedicated customer support representatives for troubleshooting and training. Sensors typically require less than 1 hour of field maintenance per year, which is provided by public agency staff or their contractors.

Users of TRAINFO’s system can deploy the system without railroad approval or interaction. The system is installed off rail property and does not require any interfacing with railroad equipment, cabinets, or communication systems. In addition, TRAINFO’s sensors can typically be installed on a pole in less than 1 hour, calibration is completed remotely by TRAINFO in less than 1 week, and TRAINFO’s APIs and devices compliant with the National Transportation Communications for Intelligent Transportation Systems Protocol enable seamless integration into existing systems. The time from sensor installation to a fully operating system can be less than a month.

Implementing TRAINFO can require multiple levels of government, including local, county, state, federal, metropolitan planning organizations, and councils of government. Furthermore, DOTs and 911 agencies may need to coordinate on various projects. Crossings are commonly located on local streets, but many local governments require county, state, or federal funding for implementation. Federal competitive and discretionary grants available for implementing TRAINFO include the Rail Crossing Elimination Program, Consolidated Rail Infrastructure and Safety Initiative (CRISI), Strengthening Mobility and Resiliency in the Transportation System (SMART), Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ), and Safe Streets for All (SS4A). FHWA’s Section 130 program also provides annual formula-based funding that covers 100% of the cost of eligible projects, including TRAINFO’s system.

Lessons Learned for the Future

Most public agencies and the industry at large encounter an unexpected degree of difficulty when attempting to develop a rail crossing information system. This is usually because of underestimating the challenges of train detection (particularly stopped and slow-moving trains), accurate and reliable rail crossing blockage prediction, third-party system integration, and ongoing maintenance and operation of the system. Intersection monitoring, which often involves multiple lanes, dynamic vehicle movements, multiple road user types, and complex road configurations, is becoming an increasingly mature field. Since rail crossings appear simpler (trains are large objects that operate along a fixed right-of-way), there is an assumption that intersection monitoring practices and technologies can easily transfer to rail crossings. Purpose-built sensors, sophisticated software and analytics, and a deep understanding of specific issues to consider at rail crossings are necessary to provide dependable commercial-grade solutions.

Future TRAINFO applications are currently being developed and involve information to support connected and automated vehicles, including integration into Apple CarPlay and Android Auto. Analytics and user interfaces are also being worked on continuously.

Case 2: Rutgers (System Based on Pilot Programs Supported by FTA Grant)

Background/Context

Rutgers researchers found that most research into railroad trespassing was derived from casualty information. However, the research overlooked near misses, which can provide valuable insights into trespassing behaviors, which in turn can help with the design of more effective control measures. To test their theory, the researchers accessed video footage captured at one crossing in urban New Jersey. They concluded that most video systems at crossings were either not continuously reviewed in real-time or reviewed manually, which is labor-intensive and expensive.

They used an AI and deep-learning tool to analyze 1,632 hours of archival video footage from the study site. During 68 days of monitoring, they discovered that 3,004 instances of trespassing (both vehicle and pedestrian) occurred – an average of 44 a day. They also found that nearly 70% of trespassers were men, roughly a third trespassed before the train passed, and most violations occurred on Saturdays around 5 p.m. during the study periods of April 2018, September 2018, and January 2019. They found value in such granular data. Such derived information could be used by local authorities to position police officers near crossings during periods of peak violations or inform railway owners and decision-makers of more effective crossing solutions – such as grade crossing elimination systems or advanced gates and signals.

The lessons learned from this research were applied in FRA and FTA research grants that followed. Under these grants, the researchers set up their system at 21 locations in 11 states, covering commuter, freight, regional, and light rail. During this research, the system detected over 100,000 trespassing events over 2 years at 21 locations, which included regional rail, light rail, commuter rail, and freight rail lines.

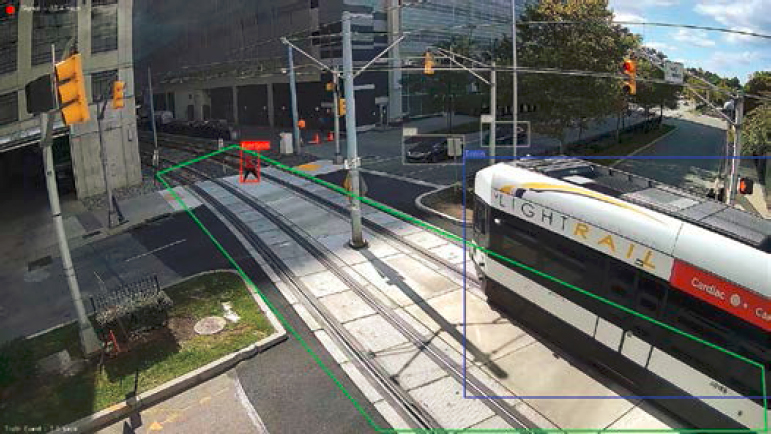

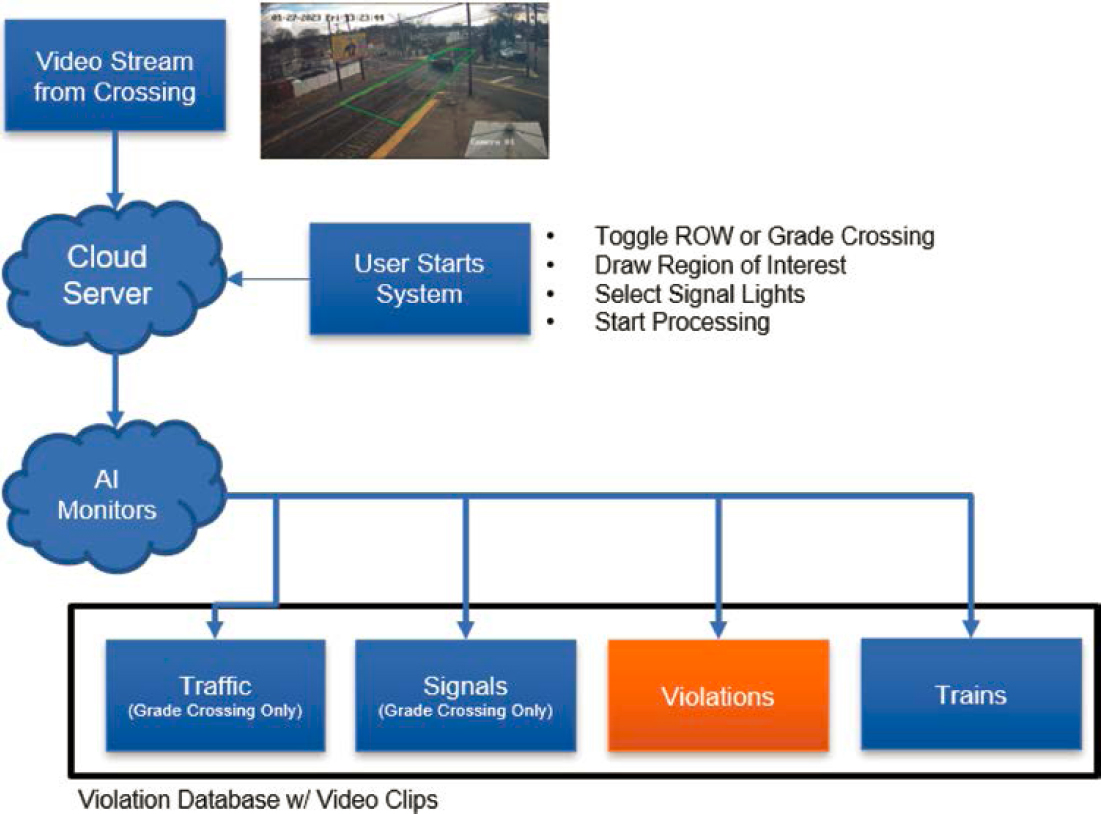

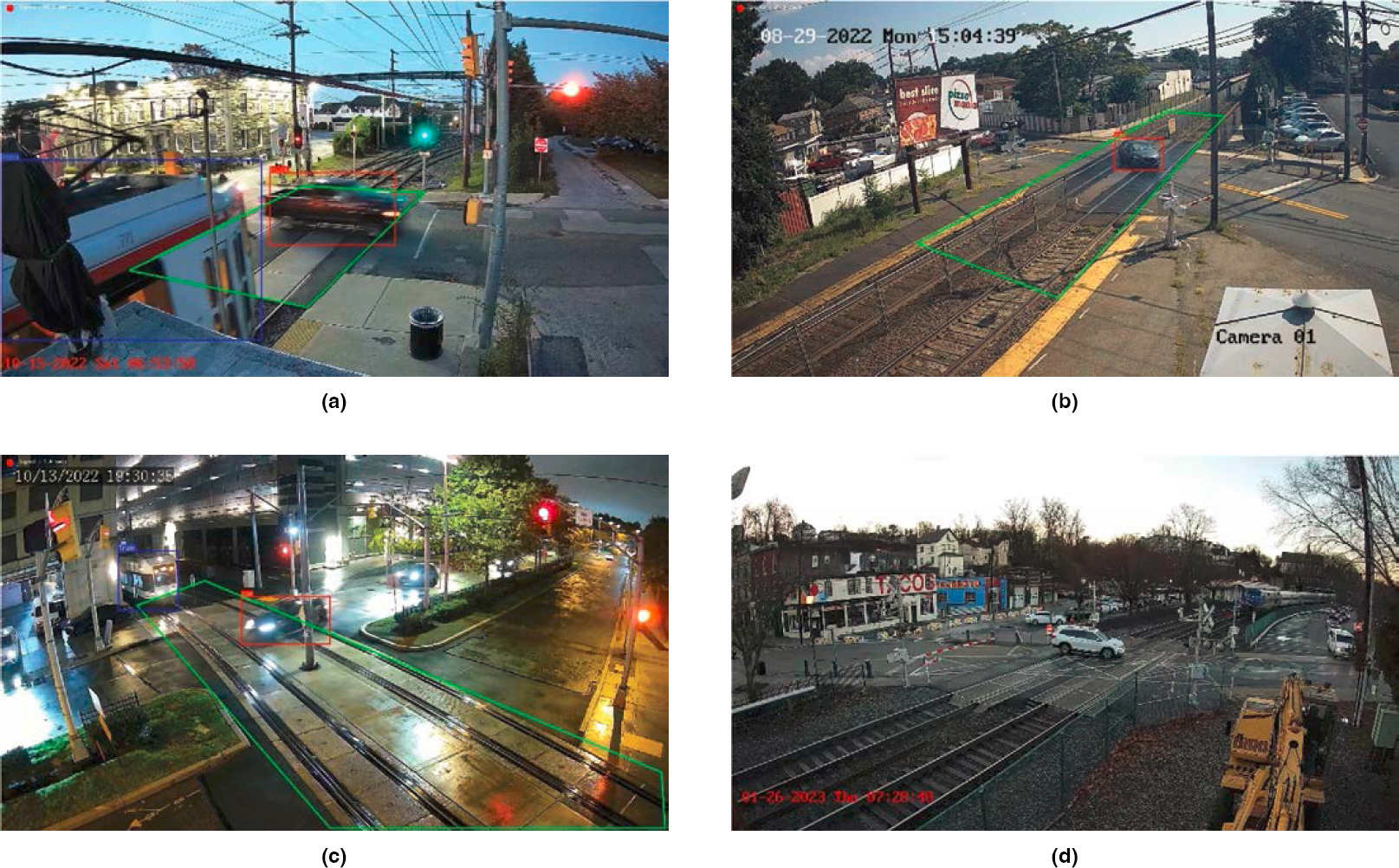

System and Technologies

Rutgers has submitted a patent application for the concept promoted through this research. They developed a turnkey full-stack solution rather than just processing the data. Rutgers licensed its software stack to its start-up company, called Redstone Technologies, LLC. The commercial tool developed based on this research effort is named the Intelligent Grade Crossing and Trespassing Tool (IGCT). Figure 16 shows an example of a pedestrian trespasser captured by the IGCT system during an FTA demonstration grant. IGCT used advanced video analytics technology, using AI to detect trespassing on railroad crossings and rights-of-way, and curb fatalities that have been increasing over the past decade. Figure 17 illustrates the system and components of the devised tool.

The Rutgers team has created an AI-aided framework that automatically detects railroad trespassing events, differentiates types of violators, and generates video clips of infractions. The system uses customized AI algorithms to process video data into a single dataset.

Applications

The pilot has been stress tested and validated in 21 field pilots and demonstration sites to detect railroad trespassing events, differentiate types of violators, and develop a profile of near misses. The system can count the traffic, estimate the trespassing rate for each class, and record who is least compliant out of all classes, which can guide solutions. Figure 18 shows vehicle violations identified at all the FTA grant project locations.

The system also helps develop spatial heat maps that show the exact trajectory of the trespassers and where the violations are occurring, which could provide a bird’s eye view for further mitigation insights. Figure 19 shows an example of a spatial heatmap identifying pedestrian trespasser hotspots.

Implementation and Assessment

The Team received cooperation from rail and transit agencies to implement the system, including the installation of their cameras and networking equipment. It streams to their cloud-based service. The user can specify a handful of pieces of data and then set the AI to monitoring. The AI gathers four buckets or classes of data: traffic, signals, violations, and trains. Several metadata are gathered for each class.

Lessons Learned for the Future

The Rutgers research team won a CRISI grant to deploy the system for 2 years at five crossings working in collaboration with Amtrak, the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development, and the Chesapeake and Delaware Railroad. The Rutgers Team plans to continue its research and education effort in grade crossing safety monitoring, trespassing detection, and data analytics, while Redstone Technologies seeks to further improve, customize, and deploy this practice-ready AI-aided technology solution on rail and transit systems in the United States.

Case 3: Metra (Commuter Rail)

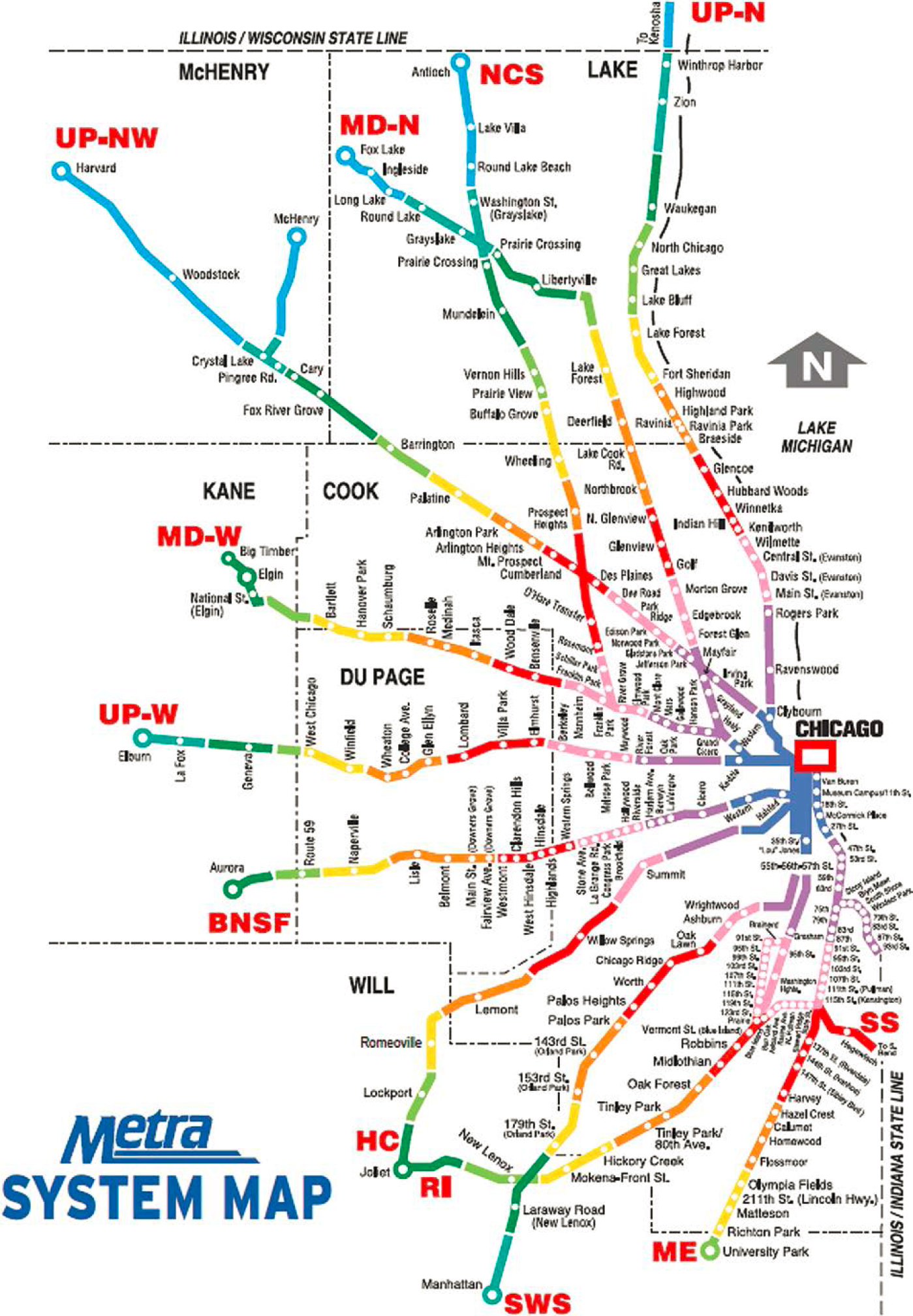

Background/Context

Metra is Chicago’s commuter rail transportation provider, serving the suburbs of the city (see Figure 20). There are a dozen lines going in all different directions away from the city. Three of the lines are owned by Metra: the Milwaukee District lines (North and West) and the Rock Island District. These are the only lines where Metra maintains the infrastructure, including the crossings; all the other lines are maintained by the host railroad.

The Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC) has the statutory responsibility to improve safety at public highway-rail crossings in the State of Illinois. As of April 2019, there were 7,595 highway-rail grade crossings in Illinois, of which 763 were on state roads, and 6,832 on local roads. There were 2,667 highway-rail grade-separated crossings (bridges) in the state. Another 3,589 grade crossings were on private property, which is not under the jurisdiction of the state, and there were also 136 private bridge structures. There were also 323 pedestrian grade crossings and 104 pedestrian grade-separated crossings (bridges) in Illinois. Nationally, Illinois is second only to Texas in the total number of highway-rail crossings.

The Commission orders safety improvements at public highway-rail crossings with the cost of such improvements paid by the state, the railroads, and local governments. On state roads, the Illinois Department of Transportation pays the majority of the costs through the State Road Fund. For local roads, the Illinois General Assembly created the Grade Crossing Protection Fund to bear most of the costs of improvements.

In 1996, the General Assembly required the Commerce Commission to evaluate the effectiveness of automated photo enforcement of traffic laws at three highway-railroad grade crossings in DuPage County. Irving Park Road in Wood Dale, River Road in Naperville, and Sunset Avenue in Winfield Township were initially selected. A fourth location, Fairview Avenue in Downers Grove, began operation in the summer of 2002; however, the Downers Grove site was not connected with ICC’s mandated pilot program. Each site employs a different type of photo enforcement technology; however, all four sites functioned similarly, by recording images of a motor vehicle not complying with activated warning devices at the subject crossings. The images recorded were used as the evidentiary basis for issuing a citation to the registered owner of the vehicle.

System and Technologies

Their main reasons for electronic surveillance revolve around increasing vehicular compliance and reducing violations. Another motivation was to do video analytics of rail crossing safety.

The key decision criteria used were to prevent or reduce trespassing, suicides, crashes, and injuries and to develop safety metrics, such as crash frequency and number of near misses. The key measures of effectiveness used were the rate of compliance or violation and the rate of violations per gate activation.

Applications

The system was used for photo enforcement only.

Implementation and Assessment

The complexity, cost, funding, and institutional considerations were key barriers and challenges. Funding came from local sources. The ICC pilot project at three initial locations was paid for with funds from Illinois’ Grade Crossing Protection Fund. They were usually funded by local highway authorities for enforcement applications, as the local police must send out citations to motorists. The agencies implementing photo enforcement consider key success factors to be relevant institutional support and video analytics that provide safety performance measures.

The photo enforcement system failed and was discontinued as the photo enforcement technology became obsolete and was not maintained. Cost was another reason for failure, because there was not enough money to install and maintain the photo enforcement system and technologies.

Lessons Learned for the Future

Keeping up with technology and maintaining the existing photo enforcement system was challenging and led to a reduction from four sites to one site in recent years. In addition, cost was an impediment.

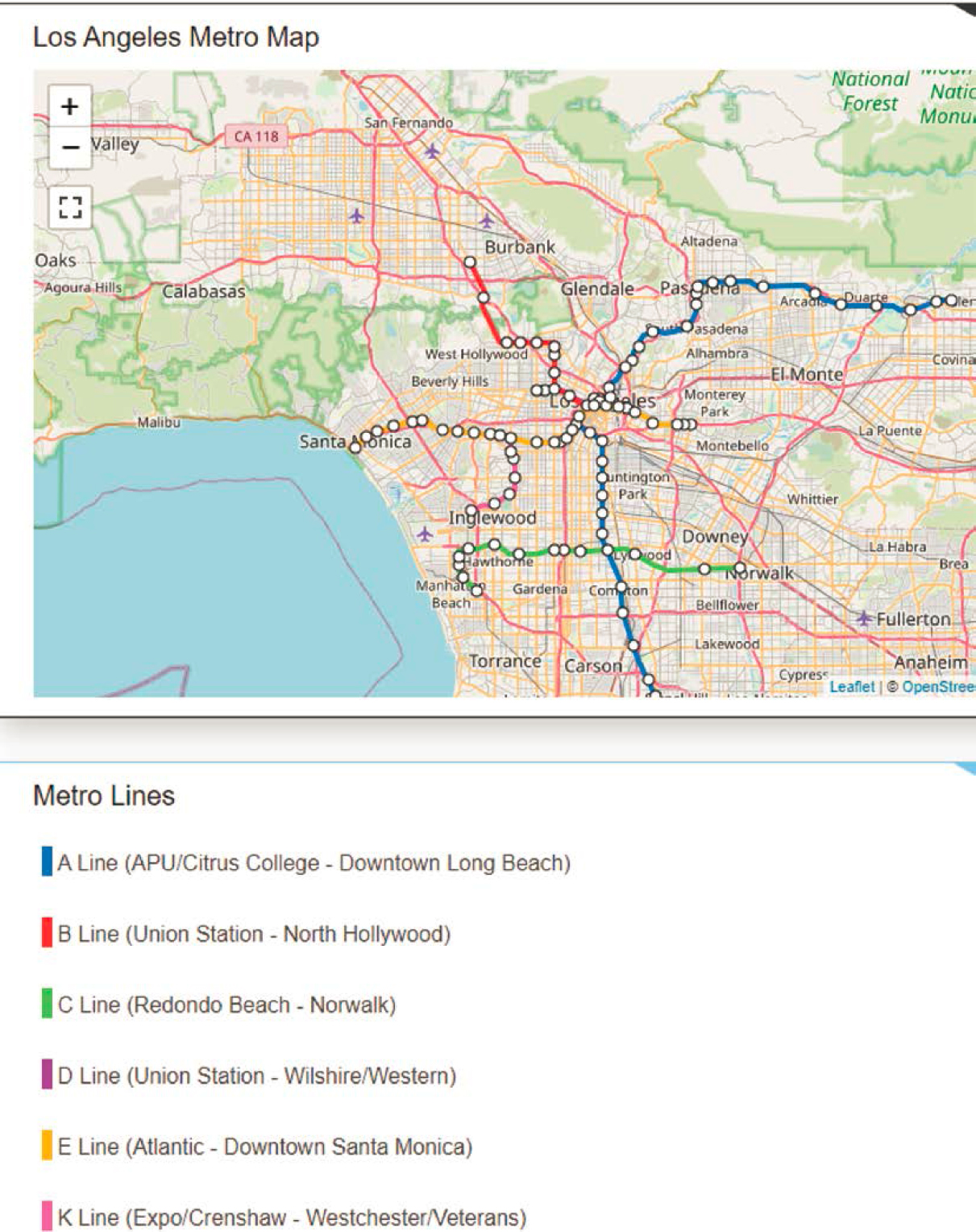

Case 4: Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Light Rail Transit)

The Los Angeles Metro Rail, owned and operated by the LACMTA, consists of six lines, including two subway (heavy rail rapid transit) lines (the B and D lines) and four light rail lines [the A, C (no grade crossings, all grade separated), E, and K lines] serving over 90 stations (see Figure 21).

Most of the LRT system right-of-way in Los Angeles is fenced. The exceptions are in downtown areas, where a steel picket fence is used. In certain areas of the downtown, the LRT operates

in the middle of a street, so that cannot be fenced. For the light rail trains in the areas that are fenced, the maximum speed is 55 mph, and in the downtown areas where there is no fencing, the maximum speed is 35 mph. The LRT system has double or dual tracks throughout the system, including at crossings.

LACMTA has a significant and widespread trespassing problem, which has not been properly dealt with by technologies and enforcement. There are over 300 miles of right-of-way, which is difficult for law enforcement to effectively cover at all times. LACMTA has a rule that says when a train operator sees a trespasser, they are supposed to stop the train and tell the trespasser to exit the right-of-way. Many times, especially in the Los Angeles area, the trespassers do not listen to the operator.

System and Technologies

LACMTA’s photo enforcement program along K Line began in 2022 with the aim of reducing the number of traffic collisions and saving lives along the new K Line tracks. In 2021 Los Angeles Metropolitan Transport Authority upgraded security surveillance with Infinova PTZ domes and fiber optics at the transit stations. They have cameras in all the state stations, on all their trains, and the train cameras are pointed outward from the front windshield. They also have a camera in the operator’s cab pointed to make sure that the operator is following LACMTA’s rules. They have several photo enforcement cameras at grade crossings to monitor vehicular violations and if necessary, issue citations or tickets.

At crossings, LACMTA has CCTV cameras connected to storage systems through cellular or fiber connectivity. LACMTA has over one hundred cameras on four light rail lines and a dedicated busway. At some locations, they have PTZ cameras when crossings are close by. Their camera system at hundreds of rail crossings on LRT lines and corridors is set up and maintained by a third-party vendor that examines instances of possible citations and issues citations after law enforcement signs off. Reasons for citations include wrong left turns, driving through lowering gates or around lowered gates, or breaking gates. Such data are provided in monthly reports that the vendor submits to LACMTA. The vendor does not provide information about citations that were paid or about repeat offenders. In California, there is a need to clearly record the back and front license plates as well as the face of the driver before it becomes a valid violation for issuing a citation. The aspect of clearly seeing the face of the driver has been challenging, reducing the effectiveness as an enforcement tool.

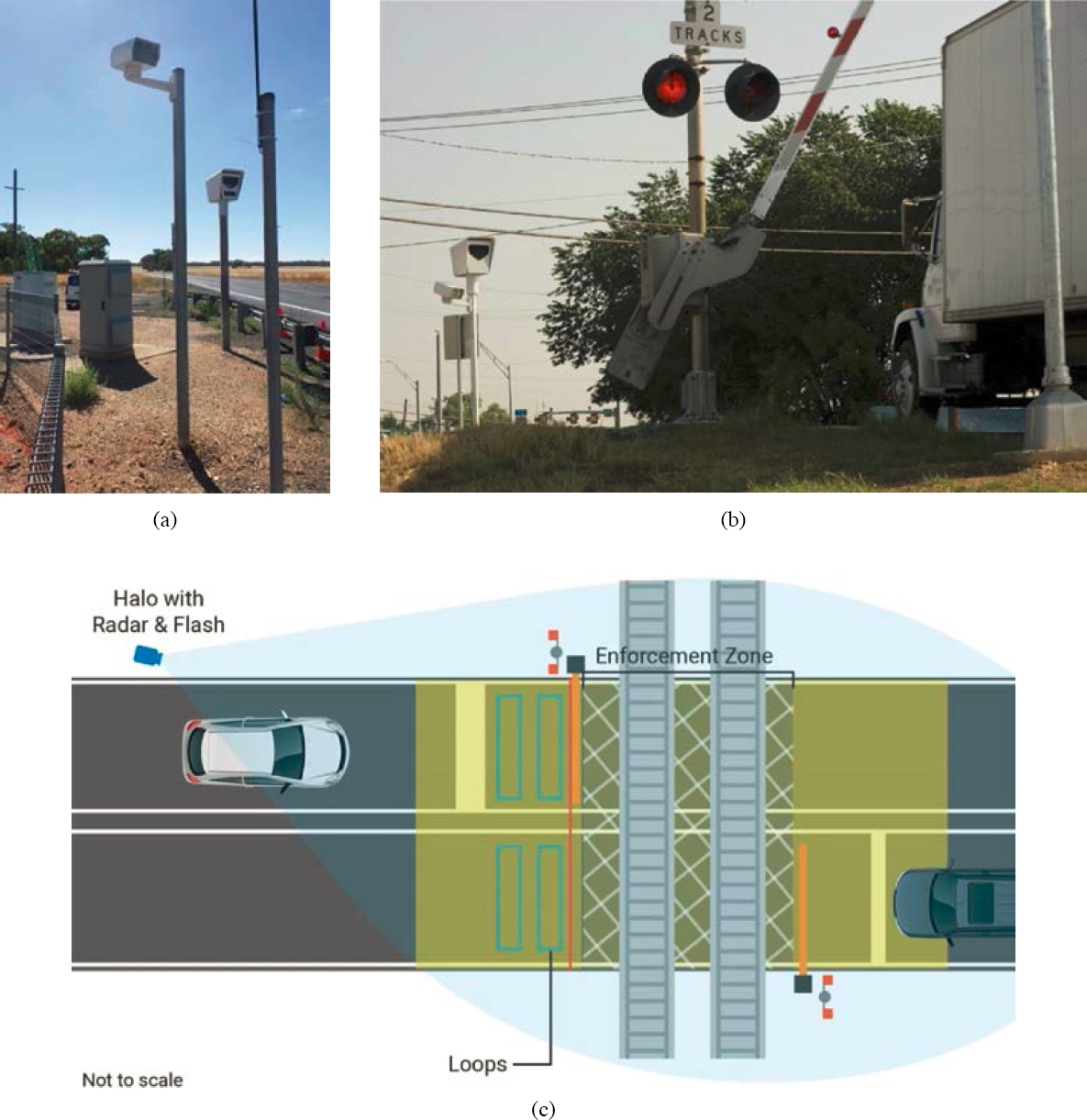

Figure 22 shows the system setup that is managed by LACMTA at over 100 of its rail crossings, indicating the camera, the Halo system with RADAR, the enforcement zone, and the rail crossing configuration with two tracks.

Applications

LACMTA used their photo enforcement to identify vehicular violations related to wrong left turns, different types of gate violations (including gate breaking), left turn violations, and evidence for the issuance of a citation by the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department.

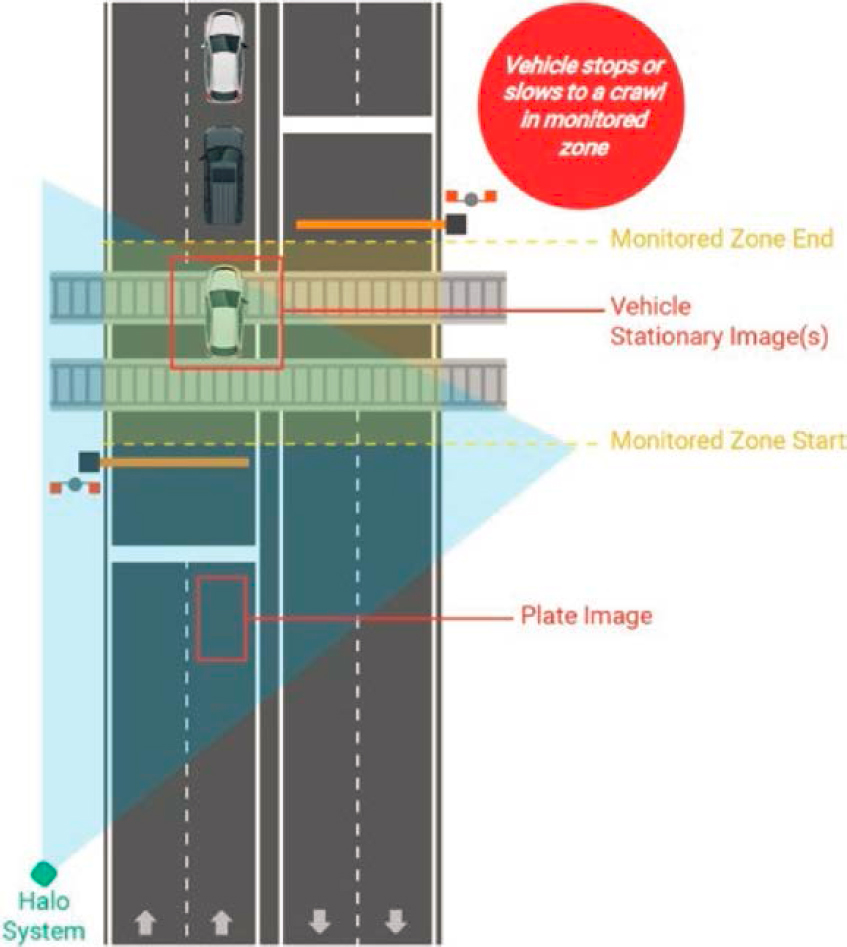

Two applications illustrate how the technological setup is used for enforcement. The first is the gridlock case (see Figure 23). Every vehicle that enters the intersection has a photograph taken to gain an unobstructed view of the license plate. The vehicle speed is monitored while the vehicle is in the rail crossing zone. The Halo system provides certifiable timing between images to provide evidence of an offense that has taken place. The camera system can be configured to monitor up to four lanes for this offense type.

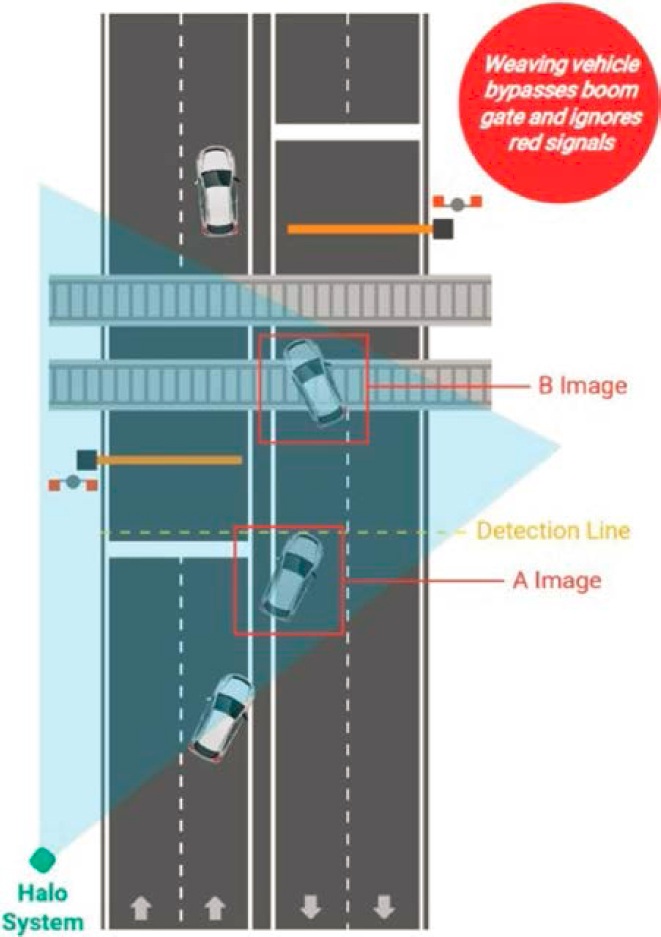

The second is the weaving case (see Figure 24). In this situation, vehicles are detected by the system as they break through the stop bar while the signal is red. Photographic and video evidence is captured of vehicles at the stop bar and the crossing. The offense is conceptually identical to a red-light offense and is enabled by additionally monitoring the oncoming traffic lanes. The camera system can be configured as shown in Figure 24.

Implementation and Assessment

LACMTA’s reasons for electronic surveillance are to

- Increase vehicular compliance/reduce violations,

- Avoid train collisions with vehicles and pedestrians,

- Alert vehicular traffic and reduce blockage on surface streets, and

- Collect safety data.

Their decision criteria are to understand and prevent unsafe driver behaviors and improve rail operations, ease of implementation, and effectiveness.

They share violation information with law enforcement in real time; their vendor does that.

LACMTA is discontinuing cameras where there are four-quad gates. Four-quad gates have the potential to reduce violations by 98% (Heathington et al. 2013). It is cheaper to install four-quad gates at new locations instead of retrofitting. LACMTA has design criteria related to the installation of four-quad gates, which is put out by California Public Utilities. Specific design details are influenced by the design conditions of the grade crossings. There are concerns about vehicles becoming trapped, but this concern has not materialized to date.

The agency now has the following number of crossings with quad gates: A Line – 32; E Line – 15; K Line – 10.

The measures of effectiveness are the rate of compliance or violation, the number of collisions avoided, the frequency of crashes, and the number of repeat violations. LACMTA has great support from their Board of Directors to provide local funding for their photo enforcement programs.

They consider reasons for the success of electronic surveillance to include

- Multiple and diverse applications,

- Availability of funding,

- Video Analytics providing safety performance measures,

- Maintenance and updating, and

- Possible availability of data and analysis helpful in decision-making.

LACMTA pays $236,000 per month (or $2.4 million per year) to the vendor that manages and maintains their photo enforcement program, including data processing for judging valid violations and issuing tickets after approval from the police department.

Lessons Learned for the Future

At grade crossings, it is not possible to prevent someone from entering the rail grade crossing and trespassing along the tracks. No technology exists to do that but it is possible to detect people when they enter the grade crossing and start walking down the track. Four-quad gates have worked much better and come close to being a preventative measure.

Photo enforcement camera programs have been a deterrent measure, but not a preventive measure. To understand its role as a deterrent, it is necessary to look at not just violations, but repeat violations.

Case 5: Metro-North Commuter Railroad (Commuter Rail)

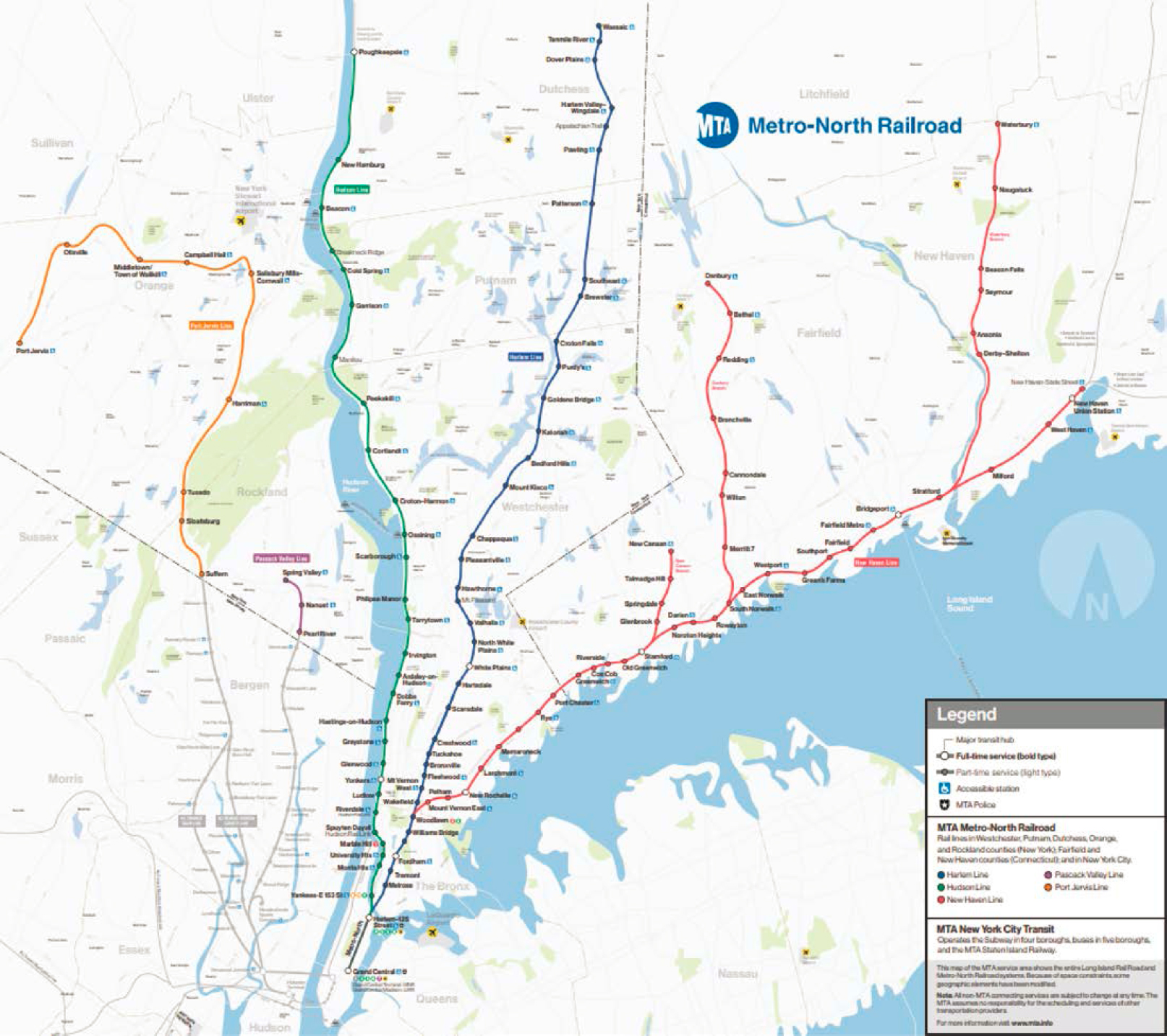

The Metro-North Commuter Railroad (MNCR) is a suburban commuter rail service that is run and managed by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), an authority of New York State. It is the second-busiest commuter railroad in the United States as measured in terms of overall monthly ridership. MNCR runs services between New York City to its northern suburbs in New York and Connecticut (see Figure 25).

System and Technologies

MNCR has used cameras for security purposes at many stations, along rail lines, and on rail cars. Every incident is captured on video from the train’s perspective but does not include videos from the crossings. Their system for electronic surveillance of rail crossings is a pilot program in

partnership with Rutgers University and is installed at a rail crossing on one of their commuter rail lines (see Figure 26).

The pilot program used advanced analytical video technology to detect trespassing on railroad crossings and curb fatalities. The rail crossing on the MNCR commuter line is one of the locations where this intelligent rail crossing solution was tried as a pilot with the cooperation of MNCR and was a benefit to both the researchers and safety and security professionals at MNCR.

Applications

The pilot has been used to monitor a rail crossing on MNCR’s commuter line to detect railroad trespassing events, differentiate types of violators, and develop a profile of near misses. MNCR shares information with law enforcement, but not in real-time.

Implementation and Assessment

MNCR considers electronic surveillance of rail crossings useful to

- Increase vehicular compliance and reduce violations,

- Avoid train collisions with vehicles and pedestrians,

- Prevent or deter trespassing,

- Alert train operators and the operations center about a potential collision,

- Collect safety data, and

- Develop video analytics of crossing safety.

The decision criteria of interest to MNCR regarding electronic surveillance of rail crossings are based on the ability of the surveillance to

- Understand and prevent unsafe driver behaviors;

- Understand and prevent unsafe pedestrian behaviors;

- Prevent or reduce trespassing, suicides, crashes, and injuries;

- Improve operational efficiency/delay reductions;

- Improve rail operations; and

- Develop safety metrics, such as crash frequency and number of near misses.

The key measures of effectiveness noted are the number of collisions avoided and the number of trespassers avoided.

Cost, funding, and technological issues are key barriers. They use a mix of federal, state, local, and internal sources for funding. There was minimal cost to set up as it was a pilot sponsored by a federal grant to test out an AI-based video analytic system.

The recurring annual cost to operate the setup per location was between $10,000 to $50,000, particularly when new infrastructure has to be set up on the right-of-way not owned by MNCR. However, MNCR can usually post a camera system on their property.

MNCR believes a successful system depends on

- A champion,

- Trained staff,

- Availability of funding,

- Relevant institutional support,

- Good maintenance and updating, and

- Effective use of video analytics in developing safety performance measures.

Lessons Learned for the Future

MNCR believes that the systems in general fail because of a lack of

- Institutional support,

- Trained staff,

- Technical resources, and

- Maintenance or updating.

MNCR is interested in electronic surveillance of rail crossings but cautious about going from a pilot program to full implementation because the institutional readiness that may be needed is not there and the priority it will receive among many competing priorities is not clear. The technology is promising but needs to be tested more.

MNCR has 700 miles of track that goes into more remote areas that have no coverage. The cellular technology there is slower, clunkier, and more demanding from a maintenance perspective to meet the needs of electronic surveillance. However, they do have plans for rolling out video at rail crossings along their corridors. There is also a big push from the MTA chair to see how to incorporate AI into the video system to enhance its ability to do more.

They have standardized their video platform, which has facilitated the sharing of information. Ultimately, NYPD, New Jersey Transit, LIRR, and Amtrak will use the same platform.

Case 6: TRAX (Light Rail Transit) and Frontrunner (Commuter Rail)

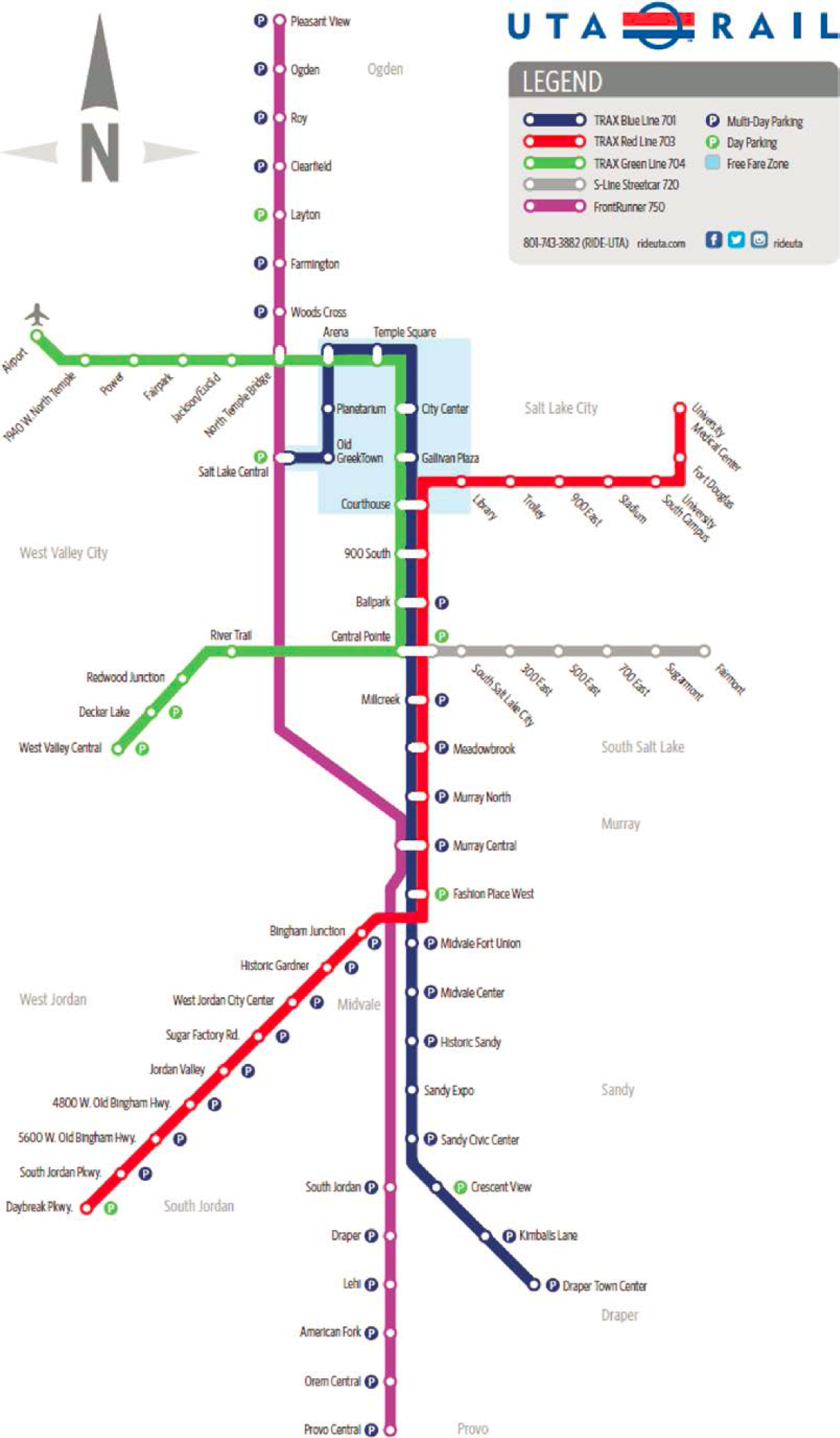

The Utah Transit Agency (UTA) is an agency that operates two types of rail service, commuter rail and light rail transit (LRT) (see Figure 27). FrontRunner is a commuter rail system that operates along the Wasatch Front in north-central Utah with service from the Ogden Intermodal Transit Center in central Weber County through Davis County, Salt Lake City, and Salt Lake County to Provo Central station in central Utah County. Frontrunner has three intermodal connections to TRAX, the local light rail train network. TRAX Serves Salt Lake County and has three lines: the Blue Line from Salt Lake Central to Draper, the Green Line from West Valley Central to Salt Lake International Airport, and the Red Line from University Medical Center to Daybreak Parkway. The LRT / light rail vehicle has two to three cars and operates at 25 mph or less. Commuter rail has a locomotive and four cars and operates at 50 to 70 mph. The PTC system started on a commuter system in 2021. Frontrunner, the commuter rail system, is 84 miles long, whereas TRAX, the LRT system, is 42 miles long and operates on a catenary system. There are more rail crossings on the LRT system than commuter rail, as it is more integrated with the road network and has many more stops than commuter rail.

UTA has on average about five fatalities a year at rail crossings. Trespassing incidents have increased in recent years and hence there is interest in electronic surveillance of the rail crossings on both LRT and commuter rail systems.

System and Technologies

The major installations of cameras at rail crossings began around the 2002 Olympics to address close calls, gate breaks, and trespassing. The number of cameras expanded from 200 to 6,000 over the entire network of LRT and commuter rail systems as well as on buses and at stations. Cameras are at 20% of rail crossings on LRT and commuter rail systems. UTA is currently working on a 5-to-10-year project to expand the use of cameras to every crossing where

most accidents happen or where trespassers gain access to the right-of-way. There is a goal to do five locations per year. The safety department develops a heatmap based on trespassing situations, gate breaking, and close calls for all rail crossings on LRT and commuter rail systems. UTA has always developed a heat map for rail crossing safety-related decision-making. The heatmap provides a basis for identifying six rail crossing locations for the installation of CCTV cameras to the UTA Board. There is a budget of $40,000 allocated for installing up to five cameras each year. When infrastructure costs, including fiber, are considered, two installations are possible.

UTA’s system has many fixed CCTV cameras, and the newer ones or replacement of older ones is with PTZ cameras. In 2021, they received a 5-year, $500,000 grant from a federal source to try video analytics at some crossings. These cameras were installed at six locations (two of which are on curves) and have thermal sensors to detect objects and motions and direct cameras to that location and object. A trigger is sent to servers where the image is checked for false positives. If it is indeed a valid image, then the video recording is saved for 10 years. All camera locations are connected to servers with fiber networks, but some are still on cellular-based connections. They use a video maintenance system (VMS) to integrate cameras, fiber/cellular communication networks, and servers.

UTA installed security cameras at all UTA rail platforms and central stations. They also have security cameras on all UTA buses and most UTA TRAX trains. For rail crossing monitoring, their system includes fiber infrastructure, switches, NEMA boxes, and PTZ or fixed cameras. There are many systems used such as TDX, cameras, and GPS tracking.

When the UTA decided to expand their rail lines in 2013, they knew that their surveillance systems would need a major upgrade to keep both passengers and property safe and secure. An open platform VMS solution and flexible storage proved to be the clear choice to efficiently support a growing public transit system as new business opportunities came to the region. Their video security system needed upgrading from one that was limited by the capacities of its servers, to accommodate a 500-camera expansion. The right choice was a VMS that was much more flexible and efficient. Milestone Systems has provided a VMS solution to enhance security for UTA. Milestone VMS supports many kinds of cameras and allows more devices on platforms while centralizing the control system. The security camera views are accessible by dispatch or control centers. The 1000+ camera system as of 2015 operated with nine HP servers (eight for recording and one for management). With this system in place, UTA could expand to 2,000 cameras or more.

Much calibration and setting up of hardware and processing of data has been done in-house by a trained video technologist. There are plans to refurbish and renovate existing space to set up a control center. In addition, there is funding to hire a person to monitor cameras at the proposed control center.

Applications

UTA uses electronic surveillance of rail crossings to

- Increase vehicular compliance and reduce violations,

- Avoid train collisions with vehicles and pedestrians,

- Identify and reduce trespassing,

- Alert vehicular traffic to reduce blockage on surface streets, and

- Alert train operator/operations center of a potential collision.

The decision criteria of interest to UTA regarding electronic surveillance of rail crossings are based on the ability of the surveillance to

- Understand and prevent unsafe driver behaviors;

- Understand and prevent unsafe pedestrian behaviors;

- Identify and reduce trespassing, suicides, crashes, and injuries;

- Improve operational efficiency and delay reductions;

- Improve rail operations; and

- Develop safety metrics, such as crash frequency and number of near misses.

UTA does not share the information with police in real time. However, they are installing a real-time center and have a dedicated staff. The center will house all kinds of servers, storing information on DVR or on cloud.

They do after-action reports with the police department and safety department to help support decisions regarding mitigation measures like fencing and treatments for commuter rail on curves where speeds are 70 mph. In addition, UTA watches for crashes and for pedestrians walking down the alignment.

Implementation and Assessment

The key barriers and challenges are complexity, cost, funding, and technology.

Building needed infrastructure to support a new switch and camera system can pose challenges. UTA’s plan for the next major upgrade to expand to a 2,000-plus camera system and their maintenance and updating is technologically complex and challenging.

Maintenance costs are between $4k to 10k and include replacements for normal wear and tear of cameras and servers. These do not have added analytical capabilities. There is typically one camera at rail crossings. PTZ cameras are used when there are two rail crossings near one another. PTZ cameras cost $600 to $800. To make the crossing fiber-ready, the cost depends on the closest connection available and that could be $10,000–20,000. With switches, NEMA box, and others, it costs $15,000–25,000. Their retention policy is to store for 7 days unless it is an incident, in which case it is preserved for 10 years.

The cost to set up electronic surveillance is $50,001 to $100,000 per rail crossing. The cost includes building out infrastructure to the site or splicing into an already run infrastructure. There is always a spending challenge when adding new cameras to crossing locations because of a lack of infrastructure. The recurring annual cost to operate the setup at one location or per location is $10,000 or less.

UTA has good support from leadership and often receives funding through capital budgets and projects to add cameras and other infrastructure for electronic surveillance at rail crossings. They have also received federal grants to enhance their systems, such as acquiring Milestone System features. In addition, they have earmarked a budget to develop a dedicated traffic control center.

The key measures of effectiveness used were the

- Rate of compliance/violation,

- Number of collisions avoided,

- Number of trespassers avoided,

- Number of instances and duration of blockage on surface streets, and

- Crash frequencies.

Their reasons for success include

- Trained staff,

- Multiple and diverse applications,

- Availability of funding, and

- Data and analysis being helpful in decision-making.

According to UTA, the reasons for failure are lack of technical resources and using electronic surveillance for a single instance/purpose. However, they have had great support from leadership, with dedicated funding to expand video surveillance network, and now have a center for monitoring and processing video data.

It is an effective system, adding more views to asset operations to keep the system moving smoothly. The team members are well trained internally on how to use data from electronic surveillance systems for investigating violations, crashes, and so forth.

Lessons Learned for the Future

Institutional support can make a big difference in the introduction of new technologies and in sustaining them. A trained staff is also critical in troubleshooting and maintaining and updating the system.

Milestone Systems combines the components of a centralized system and diversity in its deployment. The open platform provides a software integration model and ensures that UTA is not tied to any one technology, accommodating future growth. The use of Milestone technology had a positive financial impact on UTA. Gate arms at rail crossings frequently get damaged or broken off by motor vehicles. Before the Milestone installation, these costly incidents would often go unresolved. The new camera deployments helped police to follow up on incidents and even recoup damages.

The system has also been used to prevent serious incidents. For example, when a driver failed to report his truck stalled on a train track, the incident was observed in the VMS by a UTA technician who notified rail authorities. In that instance, Milestone helped avert a serious and potentially life-threatening accident. According to a UTA Video Security Administrator, Milestone saved UTA tens of thousands of dollars by allowing the agency to better monitor and investigate transit incidents and accidents.

UTA received $60 million through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to update the light rail system by replacing aging rail rolling stock, which would improve reliability, safety, and accessibility.

Case 7: TriMet (Light Rail Transit)

Portland, Oregon, is the 29th-largest U.S. metropolitan area, but the 16th in transit ridership and the 9th in ridership per capita. Founded 50 years ago after its predecessor, Rose City Transit, went bankrupt, its successor, TriMet, has been influential in shaping the growth and character of the Portland region as it provides bus, light rail, and commuter rail service throughout the region.

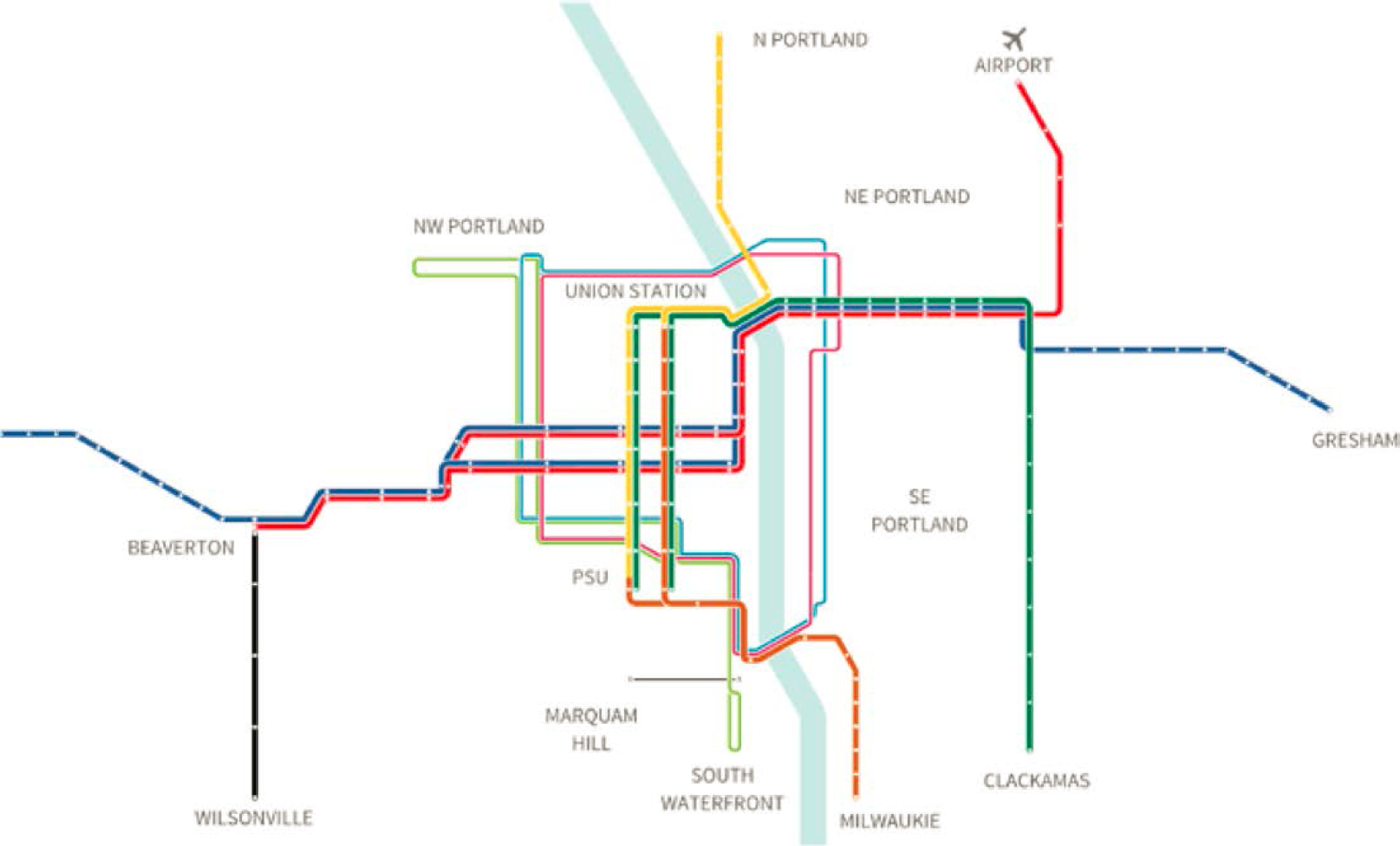

Owned and operated by TriMet, the Metropolitan Area Express is a light rail system serving the Portland metropolitan area. It consists of five lines that together connect the six sections of Portland (see Figure 28).

Freight trains are getting longer, and Southeast Portland drivers often have no escape options when a crossing is blocked. Portland recently received a $500K federal grant to study freight train crossing delays.

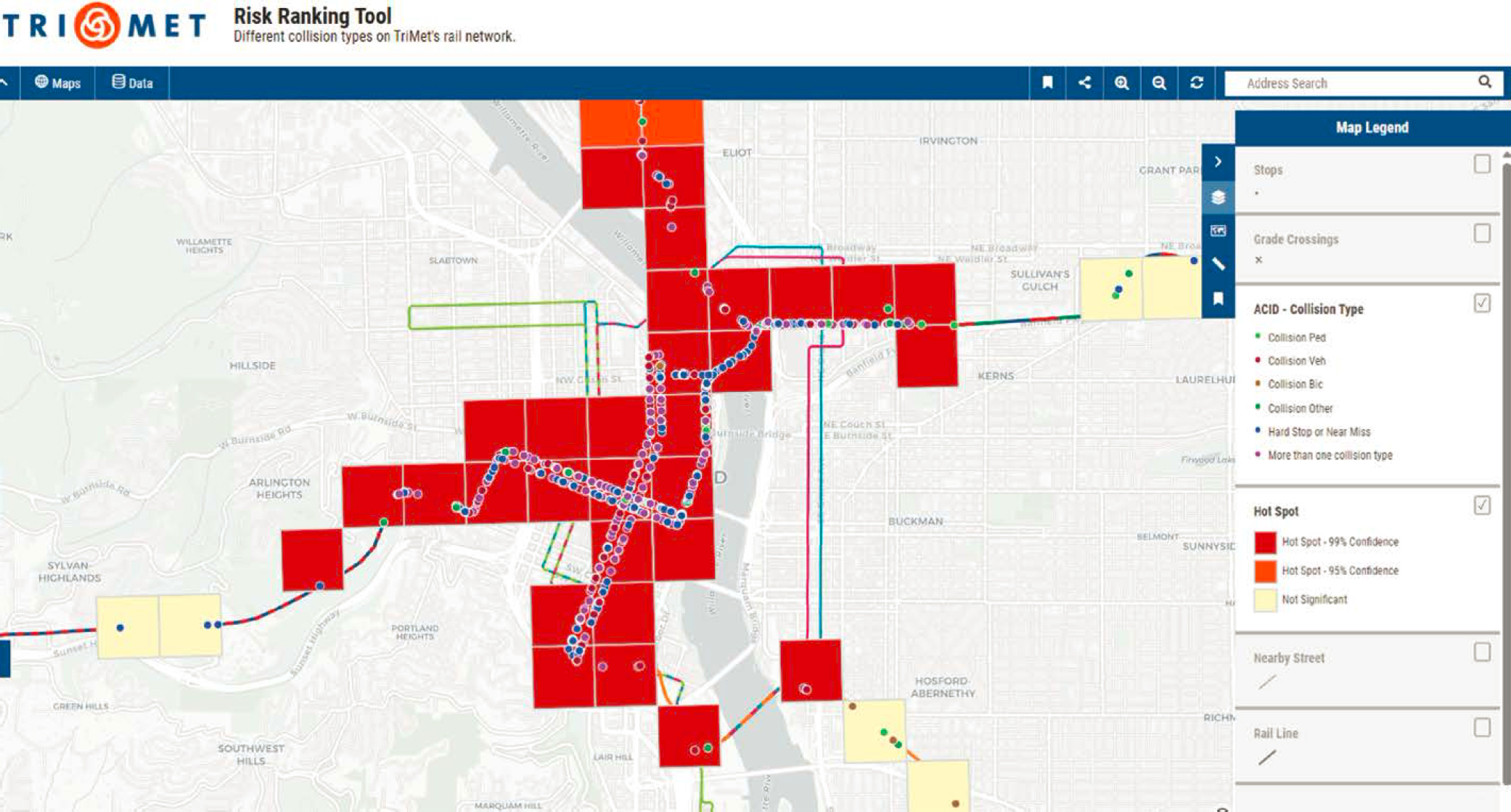

System and Technologies

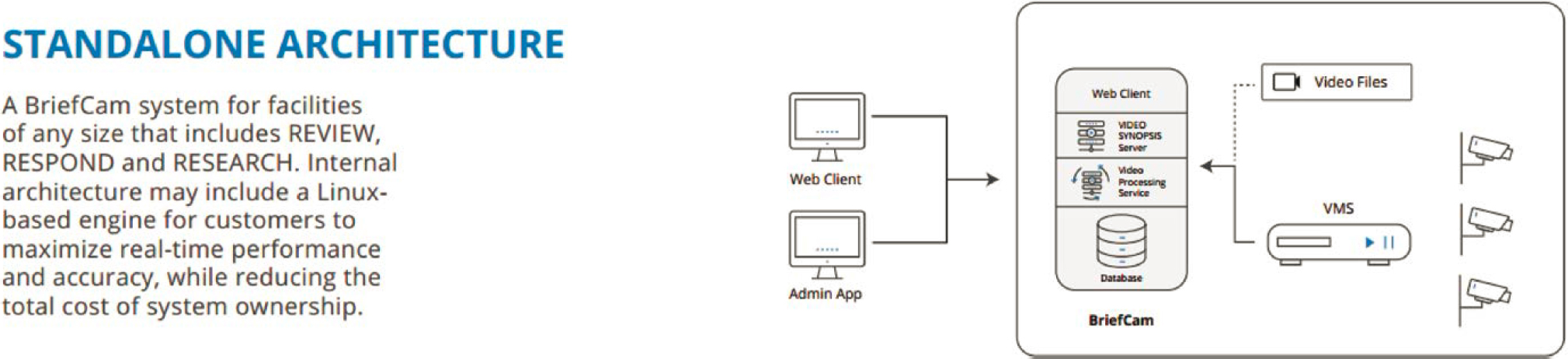

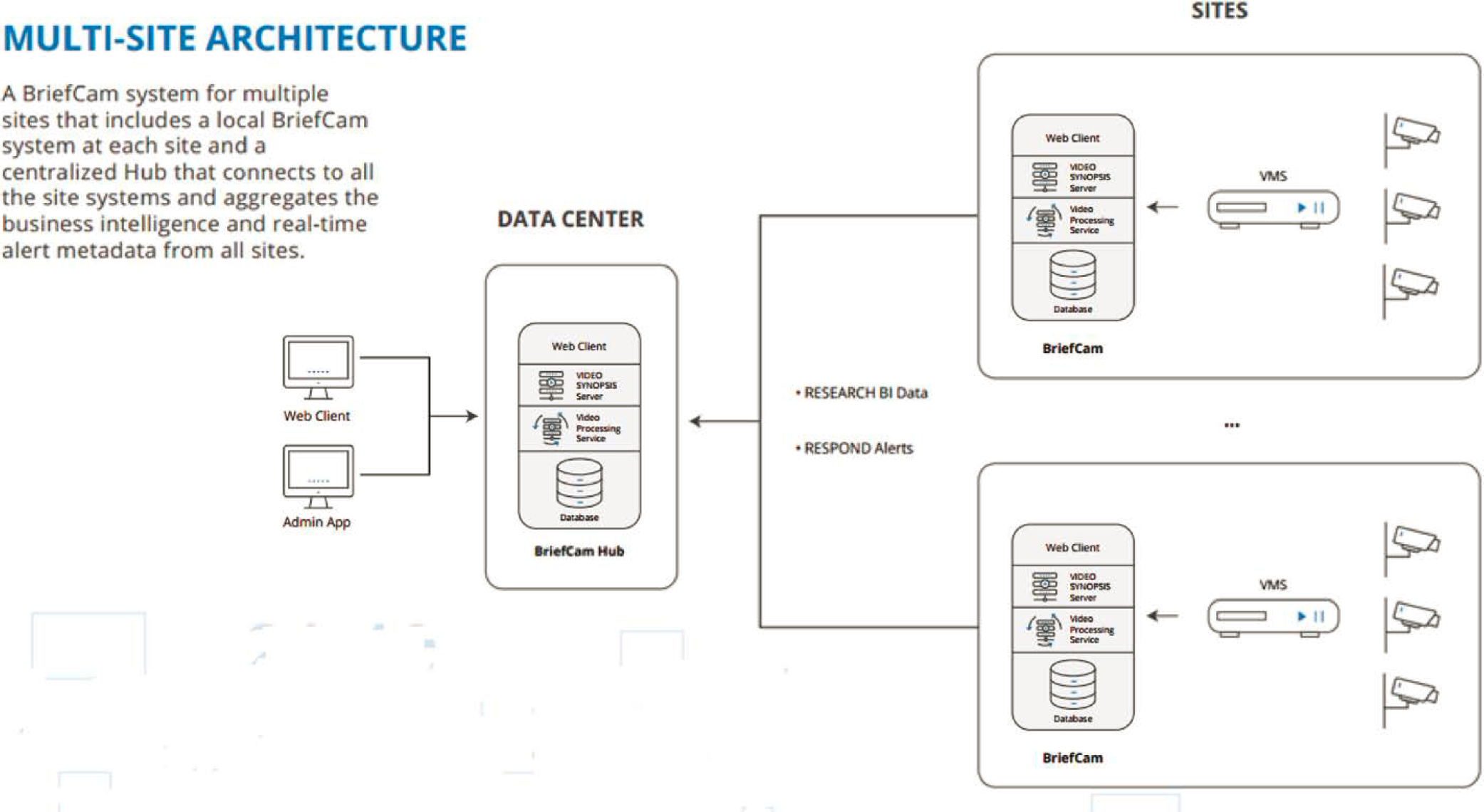

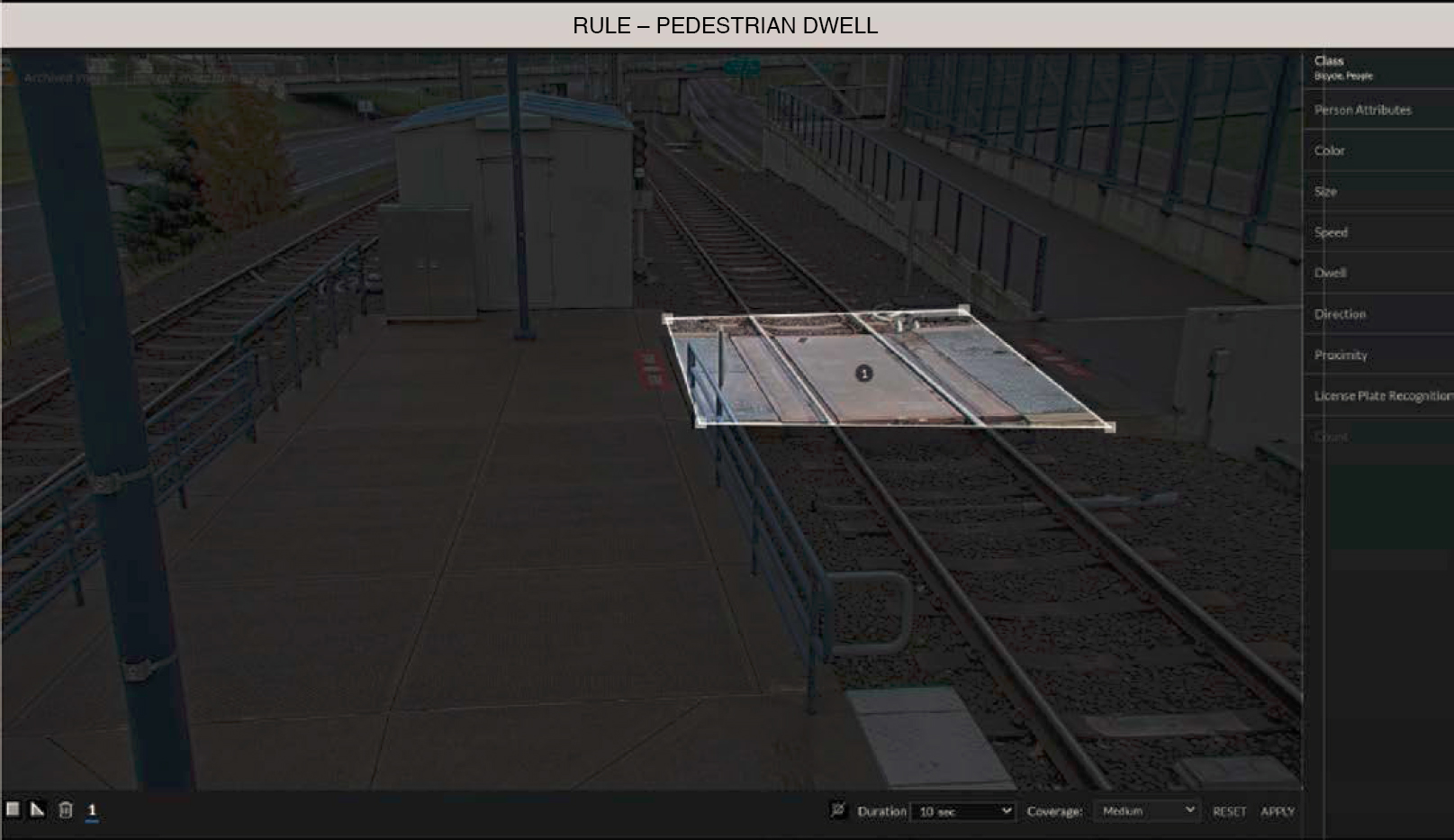

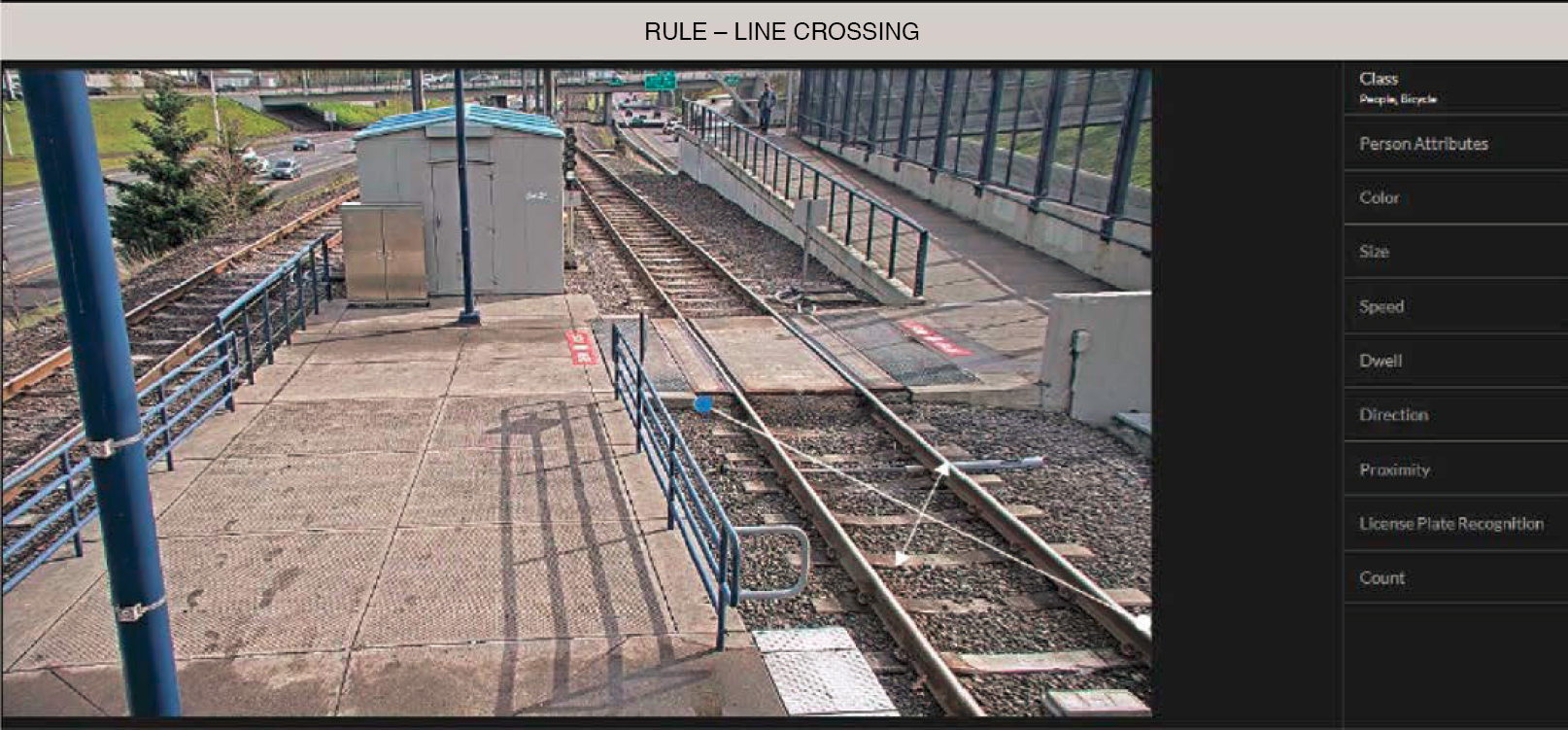

TriMet has been using cameras at crossings and other locations on stations and buses for a long time. Heatmaps (see Figure 29) assess rail crossings as candidates for better safety treatments. The primary reason for electronic surveillance was to develop a Risk Ranking Tool that could be used to evaluate crossing risk by type of crossing and types of controls that are in place. The system and tool also allow for the addition or deletion of items to see how such a change affects the risk of the crossing. TriMet received a $2 million FTA grant to enhance its risk assessment tool by integrating cameras with the BriefCam system (see Figures 30 and 31), which allowed for video analytics and insights into how to improve safety treatments and safety at critical locations.

BriefCam provides video analytics software for video surveillance content that allows for accelerating investigations, increasing situational awareness, and enhancing operational intelligence. As TriMet’s camera system is integrated with the BriefCam software, it is possible to set up rules within the software that observe trespassing and vehicle problems and automatically count the issues. Then TriMet can change the location treatments and observe the results in comparison to the previous version. Overall, software, cameras, and monitoring have cost $2 million to develop and enhance the risk tool.

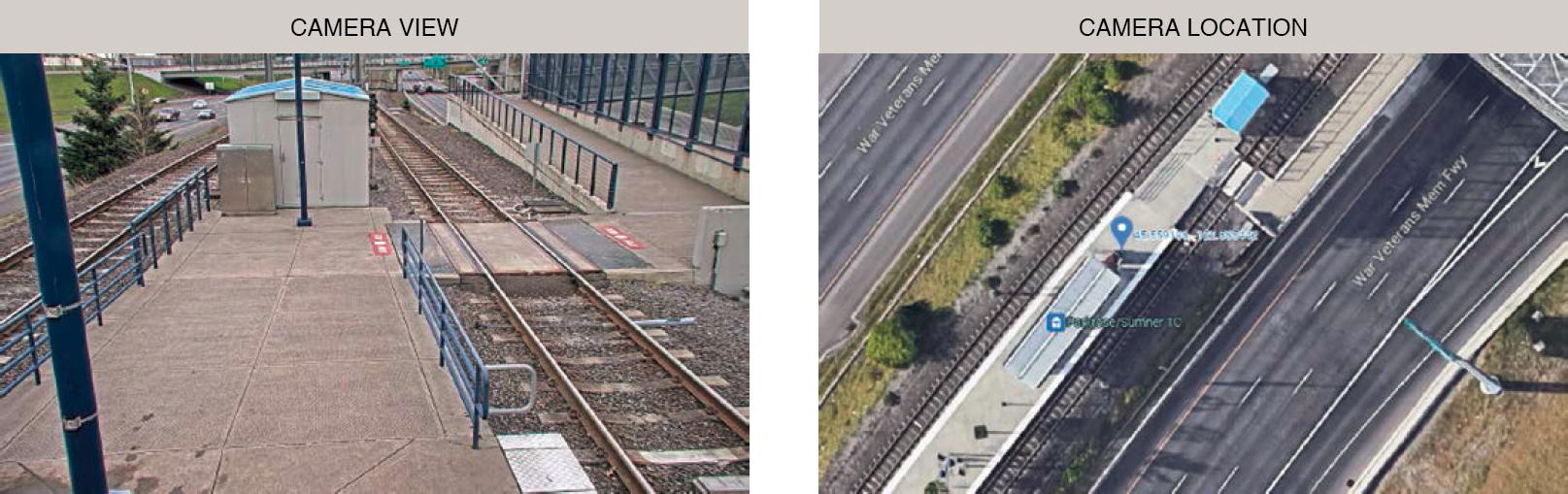

An example of camera view and camera location is shown in Figure 32. The TriMet implementation uses rules related to pedestrian dwelling, vehicle dwelling, and line crossings to study the before-and-after effectiveness of the implemented safety treatments at critical locations (see Figures 33 and 34).

Applications

TriMet’s reasons for electronic surveillance were to

- Increase vehicular compliance/reduce violations,

- Avoid train collisions with vehicles and pedestrians,

- Identify/reduce trespassing,

- Collect safety data, and

- Develop video analytics of crossing safety.

The decision criteria of interest to them were to

- Understand and prevent unsafe driver behaviors,

- Understand and prevent unsafe pedestrian behaviors,

- Prevent trespassing and suicides,

- Save crashes and injuries,

- Reduce operational delays on surface streets,

- Improve rail operation, and

- Develop safety metrics such as crash frequency or near misses.

The key measures of effectiveness used were the rate of compliance/violation, the number of collisions avoided, the number of trespassers avoided, and crash frequencies. TriMet shares the violation information with law enforcement but not in real time.

Implementation and Assessment

The key barriers and challenges were the complexity of system, finding funding, and working with the jurisdictions that are adjacent to their crossing.

The key success factors were multiple and diverse applications, the availability of funding, relevant institutional support, video analytics providing safety performance measures, and data and analysis being helpful in decision-making.

Funding was obtained from federal and internal sources. TriMet had invested in putting cameras on many crossings before they received a grant from FTA to improve their risk model to enhance safety at rail crossings. The setup cost was $10,000 or less per location. Their annual recurring cost per location was also $10,000 or less.

Lessons Learned for the Future

The key reasons for potential failure are a lack of institutional support and lack of technical resources. Video analytics have opened up doors for new and better understanding of situations at rail transit crossings.

Case 8: Network Rail (Commuter Rail and Heavy Rail)

Network Rail (NR) is the owner and infrastructure manager of the UK rail network, the fifth busiest rail network in the world. It has 20,000 miles of track, over 2,500 stations, and approximately 6,500 rail crossings. In the late 1990s, NR had more than 9,000 rail crossings, but they worked to eliminate thousands of rail crossings. The decisions regarding elimination were aided by data from the rail surveillance system, which monitors rail crossings and provides appropriate alerts to operators and operation centers.

There are only a small number of short networks where Light rail vehicles share heavy rail network tracks. The commuter rail has between two and 10 car sets. Freight trains have many cars but there is significant variability in the length of freight trains. The United Kingdom is not a large landmass, so there are several intersecting railways. The majority of the corridors are not dedicated and support a mix of freight and passenger services. Safety solutions for the grade crossings must account for variable traffic and variable density of traffic. Light rail is generally constrained to metropolitan areas. In 2014, there were two projects in Manchester and Sheffield where light rail services piggyback on the heavy rail lines for short segments to avoid heavy infrastructure interventions within urban environments.

Level Crossing Risk Management

Level crossings provide a means for vehicles, pedestrians, and animals to cross over railway lines. There are around 6,000 level crossings in active use on NR-managed infrastructure; of these, approximately 1,500 are on public vehicular roads and the remainder are where public footpaths, bridleways, and private roads/tracks cross the railway.

The Road-Rail Interface Safety Group, which is facilitated by the Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) and chaired by Network Rail, steers the work of the rail industry in increasing awareness of the hazards and risk at level crossings, bridge strikes, and other incursions by motor vehicles onto the railway. The responsible party for the assessment and ownership of risk is Network Rail, as the infrastructure manager. More specifically, it is the asset management organization. It examines public policy and makes recommendations to simplify and consolidate regulatory matters covering safety at level crossings, including road traffic and highway matters, planning guidelines for development, and the effective prosecution of offenders in the interest of public safety.

Over 90% of incidents in the previous 5 years at level crossings have been a result of user error or misuse; the remainder being because of other causes such as equipment failure, reduced visibility, or railway operator error. Typical examples of user error include incorrect knowledge of operations, misjudging the time it takes the train to reach the crossing, or making incorrect assumptions regarding who has priority of use, the direction of travel, or the presence of a second train approaching, usually from the opposite direction.

Typical examples of user misuse include users driving around half-barriers, users crossing when the crossing lights are red, users not requesting the signaler’s authority to cross (where required), and leaving gates open after use.

RSSB, in partnership with Network Rail, has developed the All-Level Crossing Risk Model (ALCRM), which is responsible for managing level crossings on UK rail infrastructure.

The ALCRM is a web-based risk tool used by Network Rail, to support it in managing the risk to crossing users, passengers, and rail staff by assessing the risks at each crossing and targeting those crossings with the highest risk for remedial measures.

Key Outputs

The ALCRM is being used by Network Rail to assess the risk at their crossings and is a key part of its level crossing strategy. The “Enhanced Specification” has been used to facilitate a technical audit by the Office of Rail Regulation and is regularly updated to reflect minor changes made to the model. The ALCRM brings three distinct advantages to the rail industry:

- It supports the ongoing collection and collation of site data to ensure that level crossings are actively and correctly managed.

- It allows the industry, for the first time, to compare the risk at completely different types of crossings in a consistent way so that resources are used to best advantage.

- It underpins the formulation and review of the industry’s level crossing strategy.

The UK Level Crossing Safety Strategy 2019–2029 aims to maximize risk reduction, reduce fatalities, reduce injuries and near misses, reduce the risk of human error, change user behavior, and improve reliability. It has four pillars: Technology and Innovation, Risk Management, Competence Management, and Education and Outreach. There is some balance between safety and performance in the strategy, but it is highly based on system safety risk. NR bases it on a holistic approach to system safety and lifecycle risk within the asset owner and capital project organizations.

System and Technologies

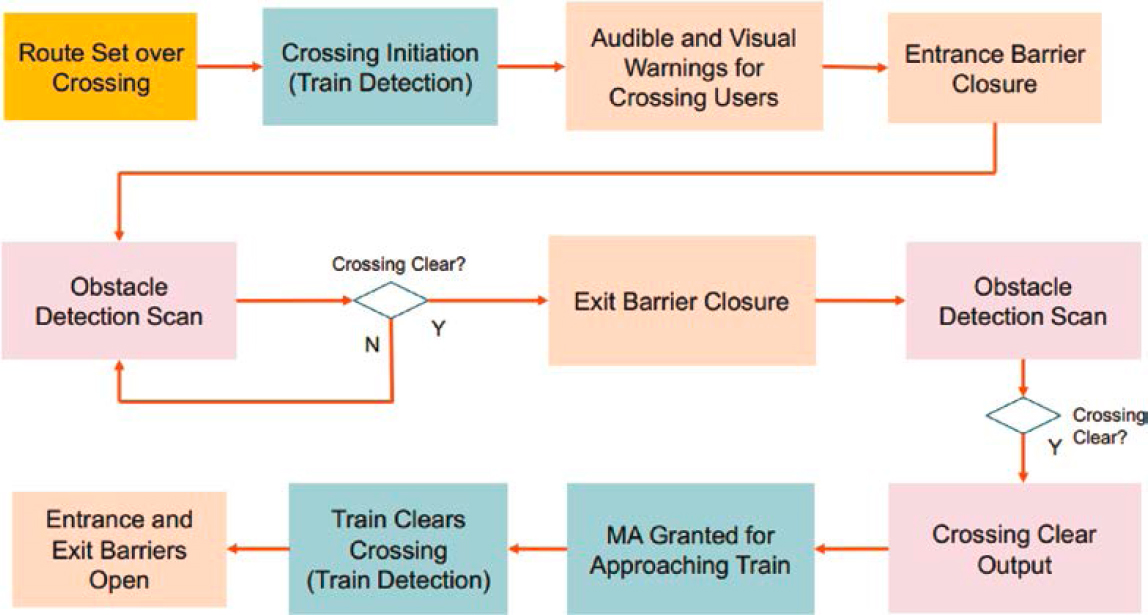

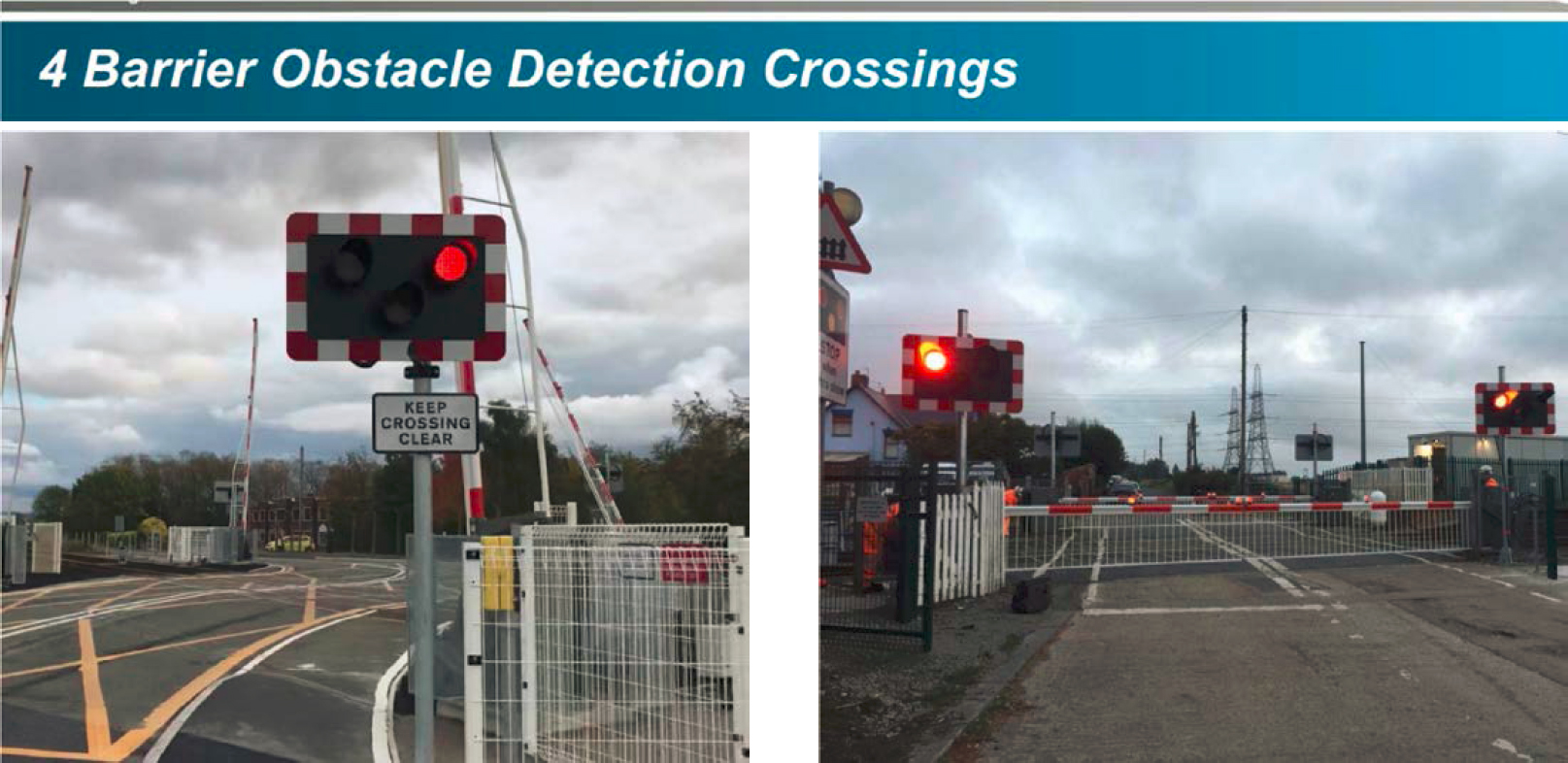

NR has two systems: Manually Controlled Barrier Obstacle Detection (MCB-OD) using RADAR/LIDAR and Manually Controlled Barrier CCTV (MCB-CCTV) using CCTV feed. MCB-CCTV started in the 1990s and MCB-OD was introduced in the last decade. There are 130 rail crossings on MCB-OD, and a slightly greater number of rail crossings are on the MCB-CCTV system. MCB-OD is the system where the safety of the crossing footprint is underpinned by RADAR and LIDAR systems. MCB-CCTV system is less automated and more managed by the dispatcher in the Control Center. All interventions at level crossings are driven by system safety risk. There is a nationalized tool to assess system safety at each site, based on individual and collective risks (see Figures 35 and 36). Figure 35 is a simplified model of the method of operation.

This is the Level Crossing Risk Assessment and its input into the ALCRM tool. Every one of the 6,000-plus crossings in the United Kingdom has a risk rating, and whenever there is an infrastructure project in the area, depending on the risk level, NR mandates interventions at these crossings. The project then assesses what the appropriate interventions are, and they will generally choose the CCTV solution or the RADAR and LIDAR solution if the risk is above a certain level based on the system’s safety risk.

Both the CCTV and the LIDAR/RADAR are solutions to consider and evaluate and choose between when the risk is above a certain level. The CCTV crossings are partially automated, so there is still an intervention required by the dispatcher at the Control Center, whereas in normal operating modes for the LIDAR and RADAR solution, it is fully automated.

From the perspective of the central interlocking processor, it does not matter whether it is encountering a freight train, a passenger train, or an LRT. The interlocking logic is independent of the particular application train using the network. The dispatcher system is the one that knows the train running number to understand what type of train it is. The interlocking system knows when there are multiple trains on approach. It holds barriers down until the final train has cleared the detection and the crossing is clear of train movements. The interlocking system is based on a highest mainline speed of 125 mph for commuter rail and 60 mph for freight rail. The signal spacing enforced by the interlocking logic is based on the worst-case deceleration.

Applications

Among the reasons for using electronic surveillance use are to

- Avoid train collisions with vehicles and pedestrians.

- Alert the train operator/operations center of a potential collision.

- Develop video analytics of crossing safety.

In establishing and operating this system, NR uses the following decision criteria:

- Understand and prevent unsafe driver behaviors.

- Understand and prevent unsafe pedestrian behaviors.

- Prevent/reduce trespassing, suicides, crashes, and injuries.

- Improve rail operations.

- Develop safety metrics on crash frequency, near misses, and effectiveness.

Implementation and Assessment

The typical project cost to convert from a passive crossing to an obstacle detection (OD) based crossing is £1–2 million, assuming a relatively simple application without significant site-specific complexities. The recurring costs are $10,000 or less per location. The system installation cost is high because of significant capital costs for hardware/software solutions, testing and commissioning costs because of specialist skills involved, and the cost to train and maintain the competence of maintenance/operations personnel on equipment.

Barriers and challenges are complexity, cost, funding, and technological concerns. Specific challenges include determining appropriate safety criticality thresholds for new and novel equipment and the resistance to change in operations by the organization.

The system is effective. It has been used several hundred times and is a generally smooth process from testing to operational service. There were some initial issues relating to system installation.

Lessons Learned for the Future

A potential use of the NR system could be the integration of grade crossing systems into the wider train control system by utilizing the “protecting signals” concept, deploying OD technology, including grade crossing equipment status in the conditions for movement authority, reporting supplementary status, and directing information reporting to the dispatcher.

NR has a Rail Accident Investigation Branch that has a repository of reports on all accidents, and it has learned lessons as it goes through a thorough review.

Fundamentally, the modularity comes from the fact that incremental improvements could be made using elements of the standard OD solution. For example, installing gates to fully block the crossing to road traffic (quad gates if required) has the most significant impact, and installing microswitches on these gates to provide input into the signaling/train control system so there is some feedback would improve on the safety. Subsequently introducing the RADAR or LIDAR (or both) will add the OD functionality, the benefits of which come when the output from this wayside system are incorporated into the movement authority or speed profile of each approaching train. This reduces the likelihood and impact of a train colliding with a pedestrian, car, and so forth.

Additional functionality could be added in terms of the following:

- Barrier displacement sensors–detect when a barrier arm has been displaced which impacts the safety of the crossings.

- Barrier protection management–inductive loops in the road providing collision avoidance functionality to stop barriers colliding with cars and trucks.

Interlocking the OD system with the broader interlocking processor safety logic of the signal system yields real safety benefits.

Summary of Case Examples

The case examples provide detailed insights on a variety of electronic surveillance of rail crossings in terms of technologies and applications. Metra and LACMTA provided insights and lessons related to photo enforcement at rail crossings. UTA provided experience with wider integration of electronic surveillance within the institutional framework and project development through great support from the leadership. The Rutgers team and TriMet pilot programs, sponsored by FTA and FRA, provide insights on the use of video analytics for the identification of trespassing problems and the enhancement of the safety risk model to better evaluate the effectiveness of different design treatments. Electronic surveillance has a role in understanding blockage and delays to traffic at rail crossings because of train events as shown by the implementation of the TRAINFO system. NR is an international example, which has a different institutional context and an integrated electronic surveillance system for monitoring rail crossings.