Building Institutional Capacity for Engaged Research: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 4 Promising Approaches for Addressing Key Tensions in Community-Engaged Research

4

Promising Approaches for Addressing Key Tensions in Community-Engaged Research

In pursuing engaged research, institutions often encounter tensions related to differing values, traditions, and priorities. This chapter explores promising approaches developed by various universities and research organizations to address these challenges. Through case studies and discussions, panelists shared strategies for aligning institutional infrastructure with the needs of engaged research, fostering inclusive cultures, and overcoming barriers that impede progress. The chapter also highlights successful models implemented to navigate and resolve the inherent tensions between traditional academic structures and the demands of engaged scholarship.

ADDRESSING TENSIONS RELATED TO VALUES, TRADITIONS, AND PRIORITIES

Engaged research can often be at odds with the traditional structure of research institutions and with values held both inside and beyond those institutions, noted Mahmud Farooque, planning committee member, and associate director of the Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes at Arizona State University. Farooque highlighted the historical tension in American universities between the production of knowledge, or “science for science’s sake,” and the application of knowledge, noting the general belief that one comes at the expense of the other. Shifts in focus usually have been driven by some combination of technological opportunities, demand conditions, and policy choices, he said. For example, the U.S. National Science Foundation was established in 1950, which shifted universities away from use-inspired research to a more science-centric approach. Then, beginning

from the 1970s, economic and competitive pressures led to a renewed emphasis on the practical application of research, facilitated in the following decade by the Bayh-Dole Act,1 which allowed universities, businesses, and nonprofit entities to own and commercialize inventions developed through federally funded research. Universities responded by establishing technology transfer offices and leadership positions focused on market-use-inspired research. Currently, there is a further shift in the knowledge-production mode, from “science for society,” toward a community- and outcomes-focused mode, to “science with society”—a transition that is particularly difficult due to differences in values between the two approaches, Farooque acknowledged.

Farooque invited panelists to share their experiences building systems and cultures that support engaged research in their respective contexts and to discuss their approaches to addressing tensions around institutional values, traditions, and priorities.

Morehouse School of Medicine: An Institutional Commitment to Community Engagement

“Community-campus relationships and trust in research are essential drivers for research that matters, both in terms of evidence-based rigor and impact but also the diffusion of those innovations between community-campus partners and the broader institution, which needs to learn how to do it and have that positive impact,” said Tabia Henry Akintobi, professor and chair of community health and preventive medicine and associate dean for community engagement at the Morehouse School of Medicine. Morehouse—a historically Black medical college, invests in “relationships first,” said Akintobi, with a focus on primary care and community-engaged research involving disproportionately impacted community and patient groups.

A key feature of Morehouse’s engaged research infrastructure is a community governance board with bylaws and rules of engagement ensuring community members’ involvement in all pillars of the institution, including serving on the board of trustees and institutional review boards. Within this infrastructure, communities are “critical, equitable partners [. . .] in really identifying what the research should be and why it is important,” Akintobi said. Furthermore, community partners are strategically positioned to directly engage with funders, industry, and community leaders, she explained, to delineate issues and determine means to address them.

___________________

1 Bayh-Dole Act, 35 U.S.C. § 200 et seq. (1981). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2011-title35/html/USCODE-2011-title35-partII-chap18.htm

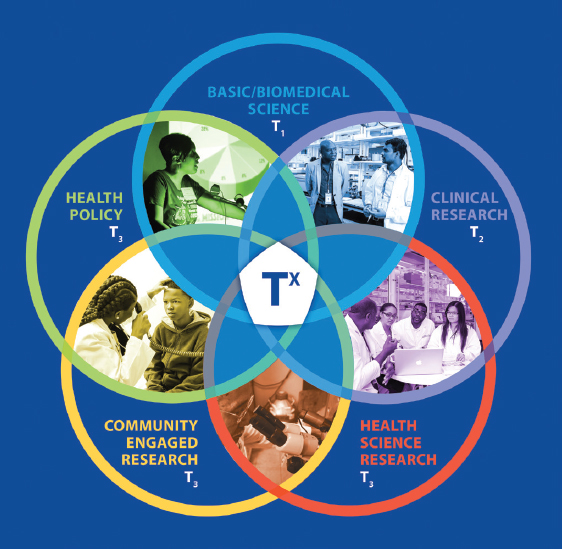

SOURCE: Tx™: An approach and philosophy to advance translation to transformation. https://www.msm.edu/Research/tx-health-equity/index.php

Morehouse’s commitment to community engagement is evidenced by a trademarked research framework developed in 2016 called Tx™,2 which emphasizes collaboration among health policy researchers, community partners, and clinical researchers across multiple areas of translational research: See Figure 4-1. According to Akintobi, the Tx™ model broadens the evidence base and leads to approaches that are adopted by or adapted to communities.

In addition to publishing this model, Morehouse provided $1 million, in $75,000 increments, to strategically identified researchers to advance Tx™ scholarship. The return on investment, Akintobi noted, has been about $75 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health and industry to these researchers and community partners. Akintobi also highlighted

___________________

2 See https://www.msm.edu/Research/tx-health-equity/index.php; Akintobi, T. H., Hopkins, J., Holden, K. B., Hefner, D., & Taylor, H. A., Jr. (2019). Tx™: An approach and philosophy to advance translation to transformation. Ethnicity & Disease, 29(Suppl 2), 349–354. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.29.S2.349

the Champions for Health Equity Curriculum, which helps to train other universities to build successful partnerships.

Akintobi concluded by emphasizing that Morehouse’s strategic plan “has positioned community engagement as a pillar within our academic health center that’s equitable and resourced just like pillars of clinical care, research, and education,” providing engaged research with the resources needed to advance health justice.

University of California, Davis: A Systems View of Change to Foster a Culture of Engagement

Using the analogy of “a slow rising but powerful upswell,” Michael Rios, vice provost of public scholarship and professor of human ecology at the University of California (UC), Davis, shared the university’s journey toward becoming a leader in engaged research and public scholarship. Following an incident in 2011 in which students were pepper sprayed by campus police and the elimination of community outreach programs in 2014, the university subsequently experienced a resurgence in interest in community engagement, mobilized by a group of faculty whose scholarship was increasingly at odds with traditional definitions of research. Within a 3-year span, Rios noted, the university attained Carnegie Foundation Elective Classification for Community Engagement,3 became the host institution for Imagining America,4 and established the Office of Public Scholarship and Engagement.5 More recent progress includes investment in a university innovation district, initiation of an anchor institution strategy to address social determinants of health, local workforce development, and the creation of a Grand Challenges Office to organize research to holistically tackle complex, interconnected social or cultural issues.

Rios takes a systems view of change, he said, drawn from his diverse experiences in community engagement and urban planning and design and shaped by three main drivers of institutional capacity building:

- The where and when: Context-specific opportunities are available in the institutional environment.

- The what and why: A compelling vision exists that motivates individuals and groups to action.

- The who and how: Mobilized action is structured around collaborative, inclusive processes to ensure lasting effect.

___________________

3 See https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/elective-classifications/community-engagement/

The Office of Public Scholarship and Engagement, Rios described, acts as a scaffold to facilitate collaborations across different units, amplify the value and impact of this work, and advocate for institutional reforms. The Office of Public Scholarship and Engagement is guided by four institutional strategies implemented to cultivate and foster a culture of engagement that recognizes and rewards publicly engaged scholarship, builds collective impact of scholars, and increases UC Davis’s impact:

- reframing the narrative from community outreach to engagement, through a communications-based approach that emphasizes reciprocity and mutual benefit;

- creating spaces of faculty recognition and inclusion and emphasizing public scholarship as an integral part of the university’s research and teaching mission that is considered in merit and promotion processes;

- aligning efforts with the university’s priorities and strategic plan, and the priorities of high-level offices; and

- expanding the ecosystem of engagement across UC Davis and the UC system, including a recent multiyear process to document and assess the impact of community partnerships and public impact and the formation of the UC Community Engagement Network.6

Rios concluded by noting that progress has been made on each of the four strategies,7 including public scholarship engagements, programs, initiatives, and online resources.

Brown University: A New Cabinet-Level Position to Advance Community Engagement Across the Institution

Mary Jo Callan, vice president for community engagement at Brown University, discussed her role in coordinating the university’s community engagement efforts since her position was established in 2022. She described the 260-year-old Rhode Island institution as unique due to its location in a small state with an interconnected community. This context of connection, said Callan, along with Brown’s mixed local reputation and complicated history of both benefit and harm, spurred the university to strengthen its commitment to advance mutuality and positive impact across all community engagement efforts. As part of these efforts, Callan’s cabinet-level

___________________

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Mary Jo Callan.

role was created to advance mutuality and positive impact beyond engaged research, to encompass every aspect of the institution, as depicted in Figure 4-2.

“We are working to identify, make legible, and change policies and processes across the institution, in every domain, that inhibit sustained reciprocal positive engagement, including tenure, promotion, and reward,” said Callan, noting additional strategies that include

- nurturing people and facilitating networks to reliably connect, coordinate, and support high-quality engagement;

- using a stakeholder-management system paired with dedicated matchmakers to facilitate understanding of community partner priorities and ideas and connect them with researchers who share those ideas;

- recruiting committed institutional leaders, as well as interested faculty and staff; and

- leveraging reclassification for the Carnegie Foundation Elective Classification for Community Engagement to deepen institutional commitments and drive systemic change.

“We’re using every lever at our disposal, understanding that this is central to our excellence, our success, and our relevance,” Callan said, referencing a recent institution-wide agenda that includes 80 strategies and actions.8

___________________

8 See https://president.brown.edu/sites/default/files/2024-05/community-engagement-agenda-2024.pdf

To conclude, Callan summed up Brown University’s theory of change, which is premised on investments in partnership capacity:

Through coordinated, collective action that draws on every aspect of the institution that centers our place—centers Rhode Island and quality of life—by connecting students, faculty, staff, and even alumni with community experts, health care providers, teachers, neighbors, [and] parents, and engaging every part of our institution, we can more fully and more clearly contribute to quality of life in Rhode Island. Engaged research is a huge part of this agenda. But again, we believe that situating and communicating it in its broader context will improve both our research and our institutional excellence.

Discussion

The discussions that followed the workshop presentations covered several topics related to the tensions panelists highlighted, including sustaining community engagement, participants’ visions of a future engaged landscape, and the influence of intergenerational change in shifting engagement practices.

Sustaining Community Engagement

In identifying positive drivers for sustaining community engagement efforts, Akintobi emphasized the importance of positioning community and patient engagement to be “health topic agnostic”—beyond any particular research focus. To promote sustainability and health equity, engaged institutions need to serve as both resources and partners, addressing community issues while amplifying community leadership and power, she said. Three stakeholder groups are necessary for this effort: community and patient leaders engaged as senior partners, policy and agency leaders who can influence policy makers regarding funding decisions, and academic partners who ensure rigorous, evidence-based solutions. This comprehensive model removes the singular research focus and promotes health equity in ways that benefit multiple stakeholders, regardless of changes in institutional leadership, said Akintobi.

Rios echoed Akintobi’s points, stressing that embedding engagement deeply in an institution’s identity, not just in its research, can help ensure that engagement efforts persist beyond individual initiatives or leadership cycles. Such work requires “ownership and a constituency that is going to take that torch and diffuse it over time and space,” he said, and grassroots support from faculty, students, staff, and community partners is critical for building an inclusive institutional culture. Callan added that both practice and visible success are crucial for establishing and maintaining a culture of engagement. Increasing the number of individuals participating in these joyful, rewarding efforts can help to shape and sustain a culture of engagement, she said.

Vision for a Future Landscape

To guide progress toward a landscape shift, a workshop participant asked panelists to project their future visions of university community engagement over the next decade. Callan’s vision identified the important role of funding. While funders are exhibiting an increasing interest in financing engaged work, efforts are often disconnected at the institution level, which community partners can find exhausting and incoherent. To solve this problem, she emphasized funding coordinated community engagement mechanisms and infrastructure within and across institutions.

Akintobi envisioned a landscape focused on broader social and political determinants of health or “the barriers and facilitators to healthy living” as key areas for future engaged research and funding efforts. Such efforts could include workforce and economic development, he noted. Rios said his vision of the future includes erasing boundaries between universities and communities, with an emphasis on co-created knowledge and faculty evaluation systems that intrinsically recognize engaged research.

Attracting and Preparing Students

A question from one participant focused on whether institutions’ efforts toward engaged research have attracted students. Akintobi observed that many of today’s students are driven by a passion for justice and equity, and while they are motivated to engage in research, barriers around the rewards and benefits of academic work need to be reduced to retain them. Rios highlighted a doctoral student cohort program at UC Davis that fosters a sense of belonging among students across disciplines, preparing them for careers that benefit the public.9 Many students involved in engaged research do not aim to become professors, he said, but instead seek to use their skills directly for the public good. Callan similarly noted that both undergraduate and graduate students at Brown are eager to engage and that engaged research often expands students’ perspectives and enthusiasm, especially when driven by community partners.

Preparing the next generation of students for engaged research requires providing them with relevant expertise. A participant asked about translating research into policy and the role of institutions, including smaller institutions like community colleges, in equipping students with policy advocacy skills. Akintobi agreed with the need for such training, noting that it is often provided by community-based organizations. Callan concurred, noting that community partners are often the “credible messengers” needed for effective policy translation. Rios shared a practical approach from UC Davis, in which faculty fellows are required to write blogs to enhance their communication skills.10

___________________

9 See https://publicengagement.ucdavis.edu/public-scholars-future

Farooque concluded the discussion by suggesting that the science of engagement could be advanced by capturing the experiences of people like those on the workshop panel, turning such experiences into scholarship to guide future efforts in community engagement.

ADDRESSING TENSIONS RELATED TO INFRASTRUCTURE

Another type of tension facing engaged research efforts involves challenges related to operational processes, procedures, or organizational structures. Elsa Falkenburger, planning committee member and a senior fellow at the Urban Institute and director of its Community Engagement Resource Center, moderated a panel discussion that highlighted actionable insights for modifying institutional infrastructure to achieve the bidirectional benefits of engaged research.

Engage for Equity PLUS Model

Prajakta Adsul, assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of New Mexico (UNM) and an affiliate member of the university’s Center on Participatory Research, said that the frustration she experienced while performing community-engaged work in cancer prevention motivated her efforts in working with Engage for Equity.11 The Engage for Equity model, which includes approximately 400 federally funded research partnerships nationwide, is based on previously identified community-based participatory research practices critical for generating meaningful outcomes, including a sense of “collective empowerment,” shared governance, and shared principles common to models of community-based participatory research.12

In the course of that work, Adsul’s team noted that many partnerships faced similar institutional barriers, such as institutional review board processes and other policies and practices that were not supportive. Engage for Equity PLUS,13 a one-on-one coaching model for academic health institutions, aims to address these challenges, Adsul said. To scale up learning from the partnership level to the institutional level, a team of academics and community partners first assesses the institutional context using a

___________________

11 See https://engageforequity.org/

12 Duran, B., Oetzel, J., Magarati, M., Parker, M., Zhou, C., Roubideaux, Y., Muhammad, M., Pearson, C., Belone, L., Kastelic, S. H., & Wallerstein, N. (2019). Toward health equity: A national study of promising practices in community-based participatory research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 13(4), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2019.0067/

13 Sanchez-Youngman, S., Adsul, P., Gonzales, A., Dickson, E., Myers, K., Alaniz, C., & Wallerstein, N. (2023). Transforming the field: The role of academic health centers in promoting and sustaining equity based community engaged research. Frontiers in Public Health, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1111779

mixed-methods approach, which involves engaging community members, researchers, staff, and institutional leadership. Data are then showcased back to the institution through workshops designed for iterative evaluation and collective reflection, and strategic priorities are set.

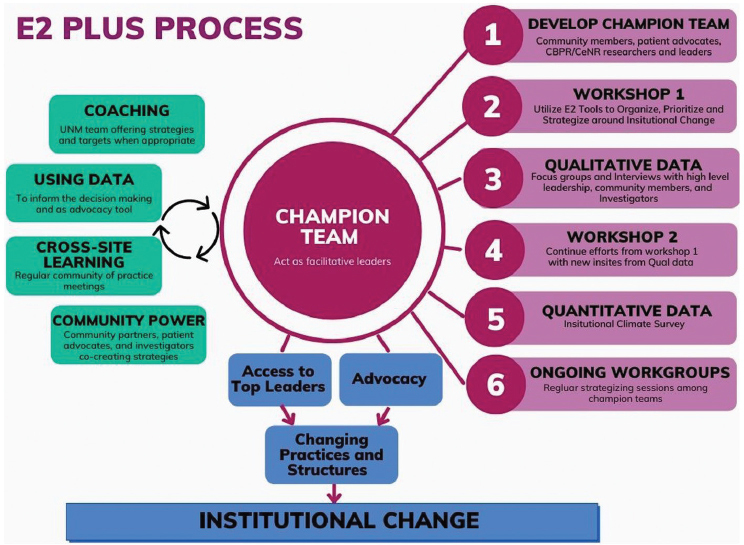

The Engage for Equity PLUS model was tested with three academic health institutions: Stanford University, the Morehouse School of Medicine, and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. Preliminary results revealed several positive outcomes, Adsul said, including the recognition of both community and institutional leaders as members of a “champion team.” As Figure 4-3 depicts, this team played a central role in the process of institutional change.

The model facilitated the creation of patient engagement offices that provided researchers with structured ways to collaborate with patients, and it addressed institutional review board processes, focusing on overcoming fiscal and administrative barriers to adequately compensating community partners. Adsul noted that ongoing work with the Mayo Clinic has led to further refinements, such as the development of a community-engaged research

SOURCE: Sanchez-Youngman, S., Adsul, P., Gonzales, A., Dickson, E., Myers, K., Alaniz, C., & Wallerstein, N. (2023). Transforming the field: The role of academic health centers in promoting and sustaining equity based community engaged research. Frontiers in Public Health, 11. www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1111779/full, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

playbook and training for both researchers and community members. Teams also provided patients and engaged researchers with a common access point and matchmaking services, she noted. The model is currently being expanded to include eight additional clinical translational science centers, aiming to embed successful practices more broadly within diverse research institutions.

University of Pittsburgh: A Place-Based Approach to Engagement

While universities may address global issues, they are fundamentally place-based, meaning they are affected by and affect the regions in which they are located, stated Lina Dostilio, vice chancellor of engagement and community affairs and associate professor in the School of Education at the University of Pittsburgh. The evolution of the University of Pittsburgh, she explained, is inextricably linked to the socioeconomic and environmental legacies of western Pennsylvania. Dostilio pointed out that local disparities in this region create research opportunities for the university’s engaged researchers—but traditional research methods often fail to translate data on people’s experiences into timely, applicable solutions for local communities.

Observing the lack of a place-responsive institutional commitment or strategy, which often frustrated the efforts of engaged researchers, Dostilio’s work has focused on developing support infrastructure responsive to the institution’s place-based legacies and obligations, thereby enhancing both the university’s societal impact and support for individual investigators and projects.

Tensions uncovered in the university’s work to establish a place-based approach, said Dostilio, included

- community feelings of overresearch and exploitation;

- research projects that seem abstract and far from offering immediately impactful solutions;

- projects disconnected from institution-level commitments and strategies;

- a primary focus on principal investigators, along with a lack of effort to develop local research staff into engagement professionals; and

- rigid institutional policies and practices, such as payment terms.

Dostilio noted that the university has since established infrastructure approaches to address the challenges, including

- long-term neighborhood commitments, such as the Neighborhood Commitments Initiative;14

___________________

14 See https://www.community.pitt.edu/neighborhood-commitments

- large-scale research studies, such as the Pittsburgh Study;15

- training and certifications for engagement professionals to develop needed competencies; and

- improved payment and contracting practices.

She invited further discussion about the ongoing tension around creating the job types, internal funding sources, convening functions, and other supports needed to enable faculty to be immediately responsive to community questions that are time-bound, urgent, and local.

Three Concepts for Infrastructure Change: Challenging Norms, Organizing, and Operationalizing

Noting that infrastructure change is a complex process, Adam Parris, director of climate resilience and senior consultant and environmental expert at ICF, said, “I think transformative change in the field of research will come in the form of [both] new institutions and change within institutions, and [from] large shifts and incremental improvements,” rather than in one or the other. Gleaned from his diverse career spanning government, academia, and the private sector, Parris’s philosophy of change is structured around three key concepts—namely, challenging existing norms, organizing, and operationalizing:

- Challenging norms: Parris questioned the implicit assumption that research inherently helps people, advocating instead for a model of reciprocal knowledge exchange. A report on the topic of climate change,16 based on his work with environmental justice leaders in New York City, outlines critical principles of knowledge exchange and provides five pathways to overhaul New York’s environment for engaged research. The work repeatedly raised the question of what researchers are providing to communities in return for what they are asking from those communities, Parris said, which helped to embed the norm of reciprocity into his group’s engaged research infrastructure. “Too often we ask for a lot in return for a little,” he said.

- Organizing: Parris emphasized the need to structure partnerships around shared, actionable outcomes, going beyond co-produced knowledge. Engaged research is part of a large web of actors, who play a role in these outcomes. Establishing the needed infrastructure

___________________

15 See https://www.pediatrics.pitt.edu/centers-institutes/pittsburgh-study

16 NYC Mayor’s Office of Climate & Environmental Justice. (2022). State of climate knowledge 2022: Workshop summary report. City of New York. https://climate.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/2022_CKE_Report_10.25.22.pdf

TABLE 4-1 Core Competencies for Engaged Researchers

| Area of Competency | Action Needed |

|---|---|

| Politics | Become more aware of public values and politics of science, including [their] role in decision making. |

| Social Capital | Build social ties and have fun. |

| Collaboration | Cultivate authentic relationships through transparency and self-awareness. |

| Communication/Exchange | Learn to communicate effectively and directly with and to diverse audiences. |

| Context | Develop ability to align different types of science and interaction with problem solving and decision making. |

| Evaluation | Design projects, programs, or activities with continual learning in mind. |

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Adam Parris.

- requires understanding the interconnected nature of government, community, and academic roles, he explained, which ultimately drive policy and funding decisions. Organizing engaged research projects to promote shared accountability to research outcomes among this web of actors can enhance power sharing, he said.

- Operationalizing: Parris underscored the need to empower researchers at all levels of their careers with “simple but routine” tools and core competencies for engaged research, including social and emotional skills, an awareness of the politics of science, the importance of social capital, and collaboration and communication skills. Table 4-1 provides a list of these core competencies.

Addressing Pain Points

Following the presentations, panelists discussed their approaches and models for streamlining infrastructure-related “pain points” that currently undermine engaged research.

- Addressing communities’ feelings of being overresearched: Dostilio elaborated on the Neighborhood Commitments Initiative at the University of Pittsburgh, which was established to address communities’ feelings of being overresearched. This initiative, supported by substantial facilities and institutional funding, involves long-term commitments between the university and key Pittsburgh neighborhoods to foster coherent, sustained community engagement. The initiative has provided “an exceptional space for people to feel

- connected to an anchoring strategy [. . .] and I think the coherency that’s been created has been remarkable,” she said.

- Establishing innovative funding sources: Parris noted that tensions around funding could be addressed by establishing new sources of revenue for universities that are aligned with the needs of local communities. Beyond tuition and indirect costs on funded research, Parris suggested innovative mechanisms, including allocating a small percentage of public utility revenues, with joint oversight, to support place-based engaged research, and using crowdfunding techniques.

- Providing supportive data: Providing supportive data to mid-level leaders who are attempting to advance engaged research could help them to demonstrate the value of this work to their leadership, Adsul said. She noted that such data can be generated using a mixed-methods approach that includes community voices, and she pointed to her team’s creation of understandable data summaries, which can be leveraged with top officials to garner resources and support for community-engaged work.

Competencies and Capacity for Researchers

Susan Renoe, planning committee chair and associate vice chancellor at the University of Missouri, asked panelists about the integration of competencies into onboarding and capacity building, both in institutions and with community partners. Dostilio stated that competencies are considered in onboarding and professional development at the University of Pittsburgh, both for engagement staff and other university personnel with community engagement responsibilities. The university also offers an “engagement fundamentals competency certificate” for new team members, an approach that is not used with community-based partners because, often, “they are teaching us,” she said. She also noted that the Community Involvement in Research Training and Implementation Certification17 at the University of Illinois Chicago and the Community Partner Research Ethics Training18 at the University of Pittsburgh are examples of accessible training for community-based practitioners, which allow community practitioners to be viewed as co-principal investigators in institutional review board systems.

Dostilio also highlighted the nationally validated competency model for engagement professionals that she uses at the University of Pittsburgh, which helps to build the necessary skills for supporting long-term partnerships and engaged research.

___________________

17 See https://www.cctst.org/cirtification

18 See https://ctsi.pitt.edu/education-training/community-partners-research-ethics-training/

Capacity Building for Communities

The panel discussion also addressed building capacity for or with local organizations to support their engagement with research. Parris shared his experience with the Cycles of Resilience project in New York City,19 which included participatory budgeting processes. In this project, his role as a researcher from the City University of New York was not to lead the project but rather to work with the community to map the locations of particular challenges it faced (e.g., flooding) and formulate project ideas that it could then continue. This process enabled communities to be better equipped to advocate with the City of New York and to engage in participatory budgeting processes of the city.

One participant noted that it can be challenging to establish the boundaries between a research institution and a community organization—for example, when a community organization might want a researcher to act on its behalf. Parris noted that in his work in New York, his team established a boundary of clarifying policy choices and bolstering those choices with evidence, while the community determined the choices it advocated.

Communication and Knowledge Exchange

A workshop participant asked the panel whether particular modes of communication can best support bidirectional engagement between communities and researchers. Panelists responded with several key points:

- Understanding the specific communication preferences in each partnership is critical, noted Adsul.

- Creating a unified institutional point of contact for community members (e.g., community engagement offices), aligned with the institution’s engagement-related mission, can ease communication at the institutional level, said Adsul. Parris mentioned that, while rare, some government agencies have community engagement offices in their planning departments.

- Boundary setting is a critical aspect of effective communication, noted Parris, advising that all stakeholders should strive to “be direct and authentic; set expectations up front and just be honest about what you can and can’t accomplish.”

- Networks for knowledge exchange between scientists, institutions, and communities can be valuable resources, noted both Dostilio and Adsul, and they offered three examples: the Advancing

___________________

19 See https://srijb.org/cycles/#:~:text=The%20Cycles%20model%20is%20a,to%20turn%20ideas%20into%20action

- Research Impact in Society,20 the Community-Campus Partnerships for Health,21 and the Community Engagement Alliance at the National Institutes of Health.22

COMMON THEMES AND GAPS

Panelists and attendees shared their observations and questions around prevailing themes that arose during discussions about key tensions and the gaps that remain in addressing these tensions to expand institutional capacity for engaged research.

Understanding Existing Structures

KerryAnn O’Meara, vice president for academic affairs, provost, and dean at Teachers College, Columbia University, shared thoughts on the need to understand the historical purposes of institutional structures before attempting to change them. She used the analogy of walking into a messy closet, where initial impressions of disorganization might conceal underlying systems that serve specific purposes. For example, when structures are changed, autonomous projects that have flourished without institutional oversight might require integration into broader university initiatives without stifling their innovative potential, O’Meara said. She emphasized the delicate balance between maintaining beneficial autonomous initiatives and addressing power issues or other structures that hinder progress. By recognizing the “origin stories” and current functions of existing structures, institutions can make informed decisions in such situations, added Elyse Aurbach, planning committee member and director for public engagement and research impacts at the University of Michigan.

Financial Barriers, Funding, and Risk

A request for a show of hands about participants’ experience of money-related tensions in engaged research indicated that most participants had experienced such barriers. Aurbach emphasized that money is an expression of power, necessitating a careful, mindful approach to the logistics around both large and small financial commitments. As noted by a workshop participant, the complexities of funding flows have negative implications for both community partners and researchers. Examples include community partners who were expected to work for extended periods without

___________________

receiving promised financial support or researchers who wanted to divert funds directly to community partners but might receive less credit for their work by doing so.

On the researcher side, one participant raised the common practice of using indirect costs to support basic science labs, noting that similar financial support is often not extended to engaged researchers. A participant suggested that some financial challenges could be addressed by submitting incentive payments and other community engagement costs as direct costs, rather than as indirect costs, in grant proposals, and urged funders to recognize these costs as essential components of research projects. A participant pointed out that grant reviewers may not understand the need for community compensation or other costs of engaged research, necessitating defined, uniform criteria as well as training for review panels, peer reviewers, and publishers.

Emily Ozer, planning committee member and clinical and community psychologist and professor of public health and faculty liaison to the executive vice chancellor and provost for public scholarship and engagement at UC, Berkeley, raised the issue of institutional risk tolerance, which is often closely tied to funding decisions, and its impact on community partnerships. Overly conservative views on risk could hinder the development of effective and timely community-engaged research, Ozer pointed out. She advocated for a broader understanding of institutional policies and legal frameworks to support flexible and responsive financial arrangements, suggesting that influential funders could play a pivotal role in pushing institutions to adopt supportive policies for partnered work.

On the community side, partnerships need to be sustained and financially supported, particularly between grant cycles, to ensure that community partners continue to be compensated, one participant said, pointing out that gaps in funding are particularly problematic for small, community-based organizations that juggle multiple roles and responsibilities. Another participant proposed simplifying the funding process and increasing its equitability by allowing community partners to receive funds directly from funders rather than through institutions.

Using Data and Shared Language

Documenting faculty support through surveys can provide a data-driven approach to advocating for engaged research, said Rich Carter, professor of chemistry at Oregon State University and faculty lead of Promotion & Tenure—Innovation & Entrepreneurship. In his experience, surveys have provided concrete data that can be used to influence mid-level administrators and build a case for institutional support for engaged work. Involving faculty from various departments and ranks in defining key survey terms and concepts helped his team create an inclusive, representative

understanding of engaged scholarship, Carter said. This approach both built familiarity with important terminology and gathered essential data to support advocacy efforts.

Building on Carter’s points, a participant emphasized the need for clarity and common terminology across differing types of engagement work. She noted the importance of distinguishing between various forms of engagement, such as community engagement and policy engagement. There is a common lack of understanding and recognition of methods and best practices, even within the engagement field, which can lead to misconceptions and undervaluation of certain approaches, she said. Developing a shared language about the components of good practice in each type of engagement, she suggested, could both assist efforts to recognize and support diverse forms of impactful work and improve evaluation and recognition of engagement activities in tenure and promotion processes.

Reflective Practices and Global Perspectives

Institutions often suffer from a gap in honest self-reflection, said Marisol Morales, executive director of the Carnegie Elective Classifications and assistant vice president at the American Council on Education, often due to a preoccupation with rankings and reputation. Reflecting on their histories of harm and considering ways to address these issues could break down institutional barriers to community participation, she said. Morales expressed optimism, stating, “We built this. We can change it. And so, I’m hoping that through these conversations we can get to that place of dismantling the things that haven’t worked and building things that will.” She noted that some international universities, including those in Australia, Canada, and South Africa, have made significant strides in reflectively redressing harms and could thus serve as models for U.S. institutions.

A workshop participant expanded on Morales’s points about universities being reflective. He discussed ongoing efforts in South African higher education to “decolonize” knowledge and recognize diverse ways of knowing—an approach that challenges traditional notions of valid, legitimate knowledge and calls for an inclusive understanding that values contributions from all partners. The participant’s comments, Aurbach pointed out, underscore the need for U.S. institutions to broaden their perspectives and incorporate diverse epistemologies into their research practices. She referenced the Center for Braiding Indigenous Knowledges and Science project,23 funded by the National Science Foundation, which explores ethically combining Western philosophies around academic research and knowledge with Indigenous ways of knowing, to address urgent, interconnected challenges.

___________________

23 See https://www.umass.edu/gateway/research/indigenous-knowledges

Leveraging Cooperative Extension Systems

Cooperative extension systems have a long history of working closely with communities and could provide valuable insights and models for other institutions, noted a workshop participant. Since many of the workshop conversations mirror issues faced by extension systems, understanding how these systems operate could help universities develop more effective strategies for community engagement, one participant stated: “A whole body of practitioners within academia that maybe have been struggling with some of these issues since the land-grant university system was put together might have really useful contributions.” Aurbach mentioned her recent experience learning about cooperative extensions and pointed out that some university systems, like the University of Missouri, do not separate extension into specific parts of the university and thus can engage broadly to understand community priorities.

Focus on Generating Solutions: Ideas from Workshop Participants

Workshop participants also offered their own insights about the tensions they were experiencing in their own contexts, and shared innovations and promising approaches for addressing those tensions organized into the categories depicted in Box 3-1. Participants were also invited to share other ideas that may not have been captured in their categories or in the presentations. After this idea-generating activity, planning committee members identified themes among the ideas that participants shared. These categories and participant ideas are available on the project website.24

___________________

24 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42782_06-2024_building-institutional-capacity-for-engaged-research-a-workshop#sectionEventMaterials

This page intentionally left blank.