Communicating a Balanced Look at Local Airport Activity and Climate Change (2025)

Chapter: 3 What Airports Can Do to Address Emissions

CHAPTER 3

What Airports Can Do to Address Emissions

Chapter 2 established how big the emissions problem is and that airports directly control only 2% to 3% of the total (Scopes 1 and 2). Airports can, however, influence Scope 3 emissions. This chapter reviews what airports can do to address the emissions problem in anticipation of communicating about this work to stakeholders and the general public. As climate change becomes a bigger problem, the airport may decide to take a proactive role in both reducing emissions and telling the public about it.

What Can Airports Do to Address Emissions?

Emissions are divided according to ownership and control of the source.

Scope 1: Emissions owned and controlled by the airport operator, such as on-site electricity generation and airport vehicles.

Scope 2: Emissions from the off-site generation of electricity or heating/cooling purchased by the airport operator.

Scope 3: Emissions owned and controlled by airport tenants and other stakeholders including

- Aircraft activity in the terminal area,

- Airline and other tenant vehicles and ground service,

- Ground support equipment and electricity usage, and

- Ground access vehicles for staff and passengers including buses and trains.

Specific actions to address emissions might include the following opportunities.

Scope 1

- Energy-efficient infrastructure: Airports can invest in energy-efficient infrastructure—such as LED lighting, smart HVAC systems, and energy-efficient building materials that can significantly reduce energy consumption and emissions.

- Sustainable airport design: Airports can invest in sustainable airport design practices, such as green roofs, rainwater harvesting, and natural ventilation systems that help reduce energy consumption and emissions from the airport infrastructure.

- FAA Airports Climate Challenge programs: These programs can provide funding support for charging stations for ground support vehicles, conversion of on-road vehicles to zero emissions, recycling, heating and cooling backup systems, and planning for new energy supply infrastructure (28).

- Alternative fuels: Airports can invest in alternative fuels, such as biofuels, electric or hybrid vehicles, and electric bus and ground support equipment. This can significantly reduce emissions from airport operations.

Scope 2

- Renewable energy sources: Airports can purchase renewable energy, such as solar or wind power, from third parties to generate electricity to help reduce emissions and energy costs.

Scope 3

- Collaboration with airlines: Airports can work closely with airlines and other operators to improve fuel efficiency and reduce emissions. This can include initiatives such as offering SAF, cooperating on optimizing flight paths, encouraging the use of more efficient aircraft, reducing taxi times by reconfiguring and expanding taxi lanes, and installing high-speed runway exits.

- Ground transportation: Airports can create and promote public transit alternatives for passengers and employees to get to and from the airport.

Any Scope

- Carbon-offset programs: Airports can invest in carbon offsets to compensate for their unabated emissions by funding projects that reduce emissions, such as reforestation, energy efficiency projects, or renewable energy installations. Carbon offsetting is a controversial topic, with even some aviation industry leaders such as United Airlines’ chief executive officer (CEO) Scott Kirby speaking out about their use (29). As a result, any carbon offsets need to be high-quality and verified by a certification body such as Gold Standard.

Undertaking an Accreditation Process

One way to put a program into place is to follow the ACA or a similar process like the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) (30) or Envision (31). The ACA process focuses on overall airport operations. The Envision process concentrates on certifying the sustainability of new projects. SBTi is an initiative to assess and approve the net-zero targets of organizations based on the Paris Agreement. Airports may also choose to follow accreditation procedures but not incur the expense of accreditation. Some airports may find the cost of certification a challenge, but reviewing airport operations and new projects via the ACA or Envision process may lead to important savings in emissions and even costs.

ACA

There are six levels to the ACA process, which can start with applying the ACERT to Scopes 1 and 2 emissions.

- Level 1 Mapping: Determine Scopes 1 and 2 emissions using the ACERT.

- Level 2 Reduction: Provide evidence of effective carbon management procedures, including target setting, and show that a reduction in the carbon footprint has occurred by comparing the airport’s latest carbon footprint to the emissions of the previous years.

- Level 3 Optimization: Widen emissions covered to include Scope 3 emissions to be measured, including LTO cycle emissions, surface access to the airport for passengers and staff, and staff business travel emissions. Engage these stakeholders.

- Level 4 Neutrality: Offset the airport’s direct Scopes 1 and 2 carbon emissions as well as emissions from staff business travel, using high-quality offsets based on the ACI Offsetting Manual (32), “based on a comprehensive study on offsetting for airports that was assigned by ACI EUROPE.”

- Level 5 Transformation: Formulate a long-term, absolute carbon emissions reduction target aligned with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 1.5°C or 2°C pathways

- and implement a carbon management plan and trajectory to achieve the airport’s carbon emissions reduction target, including participation by airport stakeholders.

- Level 6 Transition: Offset the airport’s residual Scopes 1 and 2 carbon emissions and emissions from staff business travel using internationally recognized offsets; e.g., the airport could pay for a wind energy facility that replaces a coal-fired power plant.

Each level of certification is reached only after an airport’s progress has been independently verified (33). This is an important feature of the accreditation program that can be communicated to the community.

A very important step in accreditation is in Level 2 where the airport sets goals with projected dates of completion and periodically reports on progress toward those goals. One common goal is to reduce carbon emissions per passenger enplaned at the airport. There are actions taken across multiple activities to reach the goal, linked to dates of completion of projects or other actions.

SBTi

SBTi is an initiative to assess and approve the net-zero targets of organizations based on the Paris Agreement. As part of this, participating organizations need to show how they will cut emissions in line with the Paris Agreement goal to limit warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, with both near-term (2030) and longer-term (2050) targets. That target roadmap is assessed and approved by SBTi.

At the time of writing, 4,614 companies had either set or committed to set science-based targets, and 2,310 had them approved, including almost two dozen airlines including American Airlines and Delta.

A number of airports have additionally committed to science-based targets, including the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. According to SBTi, the Port Authority has committed to reduce absolute Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions by 22% by 2025, with 2017 as the base year. The Port Authority also commits to reduce Scope 3 GHG emissions from tunnels, bridges, and bus terminals by 38% per transiting vehicle by 2032 from a 2017 base year. The Port Authority commits to reduce aviation facilities’ Scope 3 GHG emissions by 38% per passenger by 2032 from a 2017 base year.

A key difference between ACA and SBTi is that SBTi requires action on Scope 3 emissions, including emissions from airlines that use the airport. This is easier if the main tenant of an airport has already committed to SBTi. This includes American Airlines and Delta.

SBTi’s validation process uses a rigorous approach, as it mirrors the Paris Agreement. It also only allows for 5% to 10% of net-zero programs to be allocated to high-quality carbon offsets. It is backed by several major international organizations including the World Wildlife Fund, the United Nations Global Compact, the World Resources Institute, and the environmental impact nonprofit CDP.

Envision

The purpose of Envision is to foster improvement in the sustainable performance and resiliency of physical infrastructure by helping owners, planners, engineers, communities, contractors, and other infrastructure stakeholders to implement more cost-effective, resource-efficient, and adaptable long-term infrastructure investments. The key feature of Envision is independent verification of the sustainability features of a project. Those projects that satisfy requirements receive an Envision award. Table 3-1 is an outline of a pathway for a new infrastructure project.

Table 3-1. Envision verification process.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Create an Envision Online Scoresheet and Conduct Self-Assessment: In your Envision account, create an Envision Online Scoresheet by providing a few basic details about your project. You can then conduct a self-assessment of your project using the Envision framework. |

| 2 | Register Project: Register your infrastructure project through the Institute for Sustainable Infrastructure website by providing additional details about your project, requesting an invoice for the project registration fee, and submitting payment. |

| 3 | Start Verification: Once the self-assessment phase is complete, submit the project for an independent, third-party verification. |

| 4 | Design Review: Your assessment and submission are reviewed and validated. The review process is iterative in nature; project teams have an opportunity to respond to verifier comments and provide additional documentation. |

| 5 | Envision Award: Projects that earn sufficient points in the Envision framework receive an Envision award. |

| 6 | Post-Construction Review: Your assessment and submission are confirmed by the verifier after construction is complete. The purpose is to validate that commitments made during the design review were carried out during construction. A post-construction review is required to maintain the Envision award. |

| 7 | Project Complete: The project verification process concludes once the final score is returned to the project team. |

There are at least three other award programs to consider:

- CAPA’s Aviation Awards for Excellence: This includes sustainability awards for both large (>30 million passengers) and small- or medium-sized airports (34).

- U.S. Green Building Council’s (USGBC) Leadership Award: For example, Orlando International Airport won two awards last year (35).

- Airports Growing Green Awards: These awards are presented annually around the Airports Going Green Conference, which is cohosted by the American Association of Airport Executives (AAAE) and the Chicago Department of Aviation (36).

Incorporating Environmental Standards into Your Communications Program

Awards, standards, and accreditations are an excellent way to get third-party validation of airport sustainability initiatives. To make the most of this, airports should consider incorporating what they did to win the award into their communications and content programs.

Obviously, that is because awards and accreditations on their own serve little purpose unless you talk about them and what you did to get them.

Every step of getting an accreditation means taking certain actions in the airport. Tell your audiences what those actions were. Have an active content funnel (see the Amsterdam and Dallas Fort Worth examples in the case study in Appendix B) and use storytelling where you can (see the United example in Chapter 5).

Finally, to avoid the accreditations being perceived as a greenwashing exercise, everything must be backed up by concrete action, and the claims made need to be realistic.

Airports already have incentives to cut their costs of operations. Many airports might have undertaken some of these actions in any case. The ACA, SBTi, or Envision processes provide ready-made ways to plan, execute, and communicate to stakeholders and the public about climate change progress. However, if funds are not available for certification, airports can use the ACERT to set goals and self-monitor progress, which can be communicated to the community. Self-reporting can be more cost-effective, and, to enhance credibility, airports may consider sharing data publicly to allow others to monitor their progress. Pursuing other awards may also have value in telling the airport’s sustainability story.

The following four sections present other actions to address climate change. These emerging practices deserve airports’ attention.

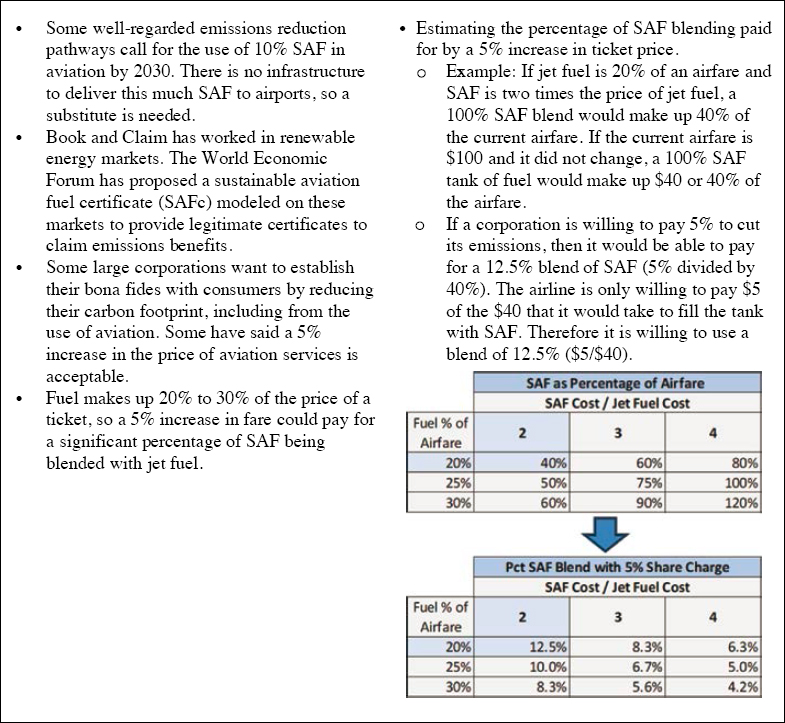

Consider Encouraging the Use of Book and Claim SAF

Chapter 2 emphasized the central role of SAF in remediating the majority of aviation emissions and the cost challenge involved in switching to SAF. However, SAF is produced in only a few locations worldwide, and it is costly to transport because there is no established pipeline network to deliver it; in addition, transporting SAF produces well-to-tank emissions.

The Book and Claim concept is designed to stimulate the market for SAF by making it possible to “book” the use of SAF fuel and “claim” the resulting emissions reduction without delivering SAF to each airport. It was originally developed as a targeted program for companies that use business aviation for travel and want to reduce their carbon footprint. A typical transaction would work as follows:

- Company A wants to cut emissions from its business travel.

- It calculates the amount of jet fuel used for its travel.

- It then buys a certificate that indicates the reduction in emissions represented by an equivalent amount of SAF.

- The SAF enters the fuel supply chain at a different airport that is closer to the production facility, but the emission credit is allocated to the buyer of the certificate.

Care must be taken not to count the benefit twice, but what has happened is that a buyer of fuel in a remote location has stimulated the market for SAF at locations where it is more easily available.

As a complement to encouraging Book and Claim for operators, including airlines, the airport can also encourage accurate and transparent tracking of the benefits of substituting SAF for jet fuel. Not all SAF has the same emission reduction benefits, and not all SAF feedstock is sustainable. Tracking all of this information is complicated. One organization that is keeping up with developments is SABA, the Sustainable Aviation Buyers Alliance (37), shown in Figure 3-1.

More detailed and technical information can be found on the ICAO website for CORSIA, the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (38). The primary objective of CORSIA is to publish standards for offsets that operators can use to meet carbon-reduction objectives that will become mandatory for signatory countries beginning in 2027, as discussed in Figure 3-2.

Some Book and Claim Programs That Aircraft Operators May Join

- SkyNRG (an SAF supplier) works with the World Economic Forum, RMI, and PwC Netherlands seeking to “create a strong, sustained demand signal for certified emissions reductions from the use of SAF. For this to occur, however, it is vital that there be clear and standardized accounting and reporting” (https://skynrg.com/how-to-reduce-business-travel-emissions-amore-sustainable-return-to-business-travel/).

Picture credit: Pexels Royalty-Free Photo

- Avjet notes that “with Avfuel’s book and claim program, a customer can purchase SAF (the claim) no matter where they’re located—paying the premium cost for SAF over jet fuel and, in return, receiving the credit for its use and applying it to their ESG [environmental, social, and governance] scores. This SAF is taken off the book at an airport where the physical SAF molecules are held and being uplifted by customers who are simply paying for jet fuel and do not get to claim credit toward using SAF in their ESG scores” (https://www.corporatejetinvestor.com/news/avfuel-launches-book-and-claim-program-to-expand-saf-benefit-globally/).

- bp provides the following example: An SAF blend is available at Airport A, but an operator or company has no business at Airport A. Air bp delivers the SAF blend to Airport A but registers sustainability credits with the Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials. The customer buys the credit and claims the emissions reduction (https://www.bp.com/en/global/air-bp/news-andviews/views/making-saf-more-accessible-for-all.html).

- Avelia is a block chain registry and SAF delivery partnership of Accenture and Shell with energy web advisers (https://aveliasolutions.com/).

Carefully Consider Encouraging the Use of Offsets

What Is an Offset?

Carbon offsetting is a mechanism for compensating for the emissions of GHGs, by supporting projects or activities that reduce or eliminate the equivalent emissions elsewhere. Examples include

- Reforestation—plant new trees or restore degraded forests, which absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and store it as carbon in the trees and soil; and

- New renewable energy projects—wind, solar, hydropower, or geothermal energy production that replaces fossil-fuel-powered energy plants.

Why Are Offsets Popular?

- Offsetting is a straightforward concept. Consumers understand the idea of paying X dollars to plant Y trees to offset their transcontinental flight.

- The projects supported appear worthwhile.

- Offsets are available now and at scale.

What Are U.S. Airports Doing?

- Some U.S. airports either use carbon offsetting for their own operations or offer them to passengers via third parties.

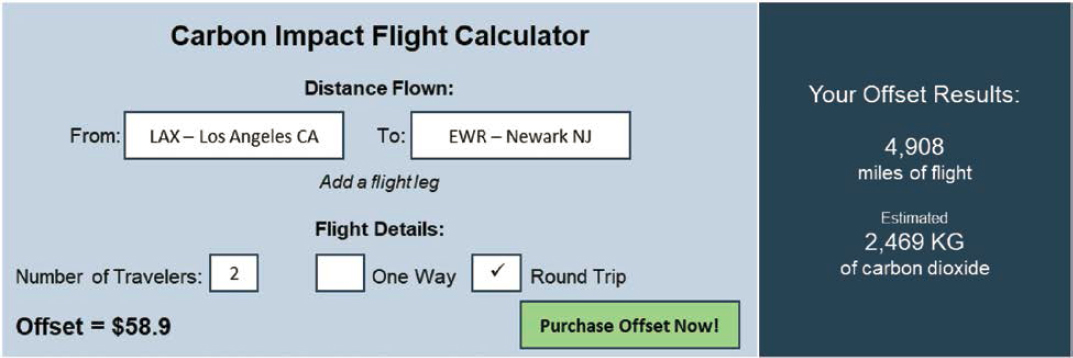

- For example, The Good Traveler (39) initiative was founded by San Diego International Airport (SAN) in 2015 and is now used by 20 airports in the United States, including Dallas Fort Worth International Airport (DFW), Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK), Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR), LaGuardia Airport (LGA), and Teterboro Airport (TEB). See Figure 3-3 for an example of how offsets are calculated per flight.

- Some airlines offer offsets to passengers [e.g., American Airlines via Cool Effect (40)].

CORSIA also lists vetted and approved offsets. The following programs are CORSIA eligible.

- American Carbon Registry.

- Architecture for REDD + Transactions.

- China GHG Voluntary Emission Reduction Program.

- Clean Development Mechanism.

- Climate Action Reserve.

- Global Carbon Council.

- Gold Standard.

- Verified Carbon Standard.

However, there is potential for abuse in the market for offsets. The main question that has been raised is whether offsets really result in a reduction in emissions. There are five key characteristics of worthwhile offsets (41):

- Additionality: GHG reductions are additional if they would not have occurred in the absence of a market for offset credits. If a project would have been pursued without offsets, it is not additional.

- Avoid Overestimation: Offset claims are estimated using established (e.g., UN) methodology.

- Permanence: Reversal of the project is impossible or very unlikely.

- Exclusivity: Demonstration that the offset is only claimed once—for example, having the seller of the offset also be the owner of the project.

- Avoid Social and Environmental Harm: Compliance with local laws and certification that there are no add-on adverse impacts.

What Are Some of the Concerns with Offsets?

Critics say offsets do not abate emissions:

- Scott Kirby, CEO of United Airlines: “Carbon offsets have been a bone of contention for me because they’re almost all fraudulent” (42).

- Stanford Social Innovation Review: “Although offset programs claim to offer carbon-sequestration benefits that contribute to a carbon-neutral economy, the governments and corporations that reap the financial and reputational benefits of these programs often show no inclination to halt their extractive practices . . . [that] generate larger adverse impacts on the environment and Indigenous communities than offset programs can tackle” (43).

In short, there is a concern about the quality of offsets: Do they really result in a reduction in emissions? In addition, airports should take care before claiming the benefits of offsets. If the airport controls a project (e.g., solar panels), it is much more likely that the offsets are legitimate but only if the project would otherwise not be pursued.

Airports can consider the following issues when utilizing carbon offsetting programs and communicating their use.

- Transparency: Consider communicating where the money goes, who benefits, and who verifies the project. Also, note that not all verification bodies operate to the same standards. For example, unlike other organizations, the carbon-offset audit scheme Gold Standard does not sell controversial deforestation protection credits (44).

- Price: In its investigation, Bloomberg called cheaper carbon-offset credits “junk.” If the price per carbon ton is too low, it may be less likely that the scheme in question will be effective.

- Realistic claims: The United Nations Environment program says that “carbon offsets are not our get-out-of-jail free card” (45). Carbon offsets are not a silver bullet that allows for “green flying.” Rather, they are a solution that works now at scale, while the hard work of industry decarbonization goes on in the background.

- The big picture: Related to the previous point, carbon offsetting can be one element of a larger sustainability and net-zero program. Consumers can be told about the medium and longer-term initiatives taking place.

- Local opportunities: Finally, is there an opportunity to support carbon offsetting and/or biodiversity projects in your local area? This, of course, sends a strong message about the airport being a good corporate citizen, in addition to the offsets.

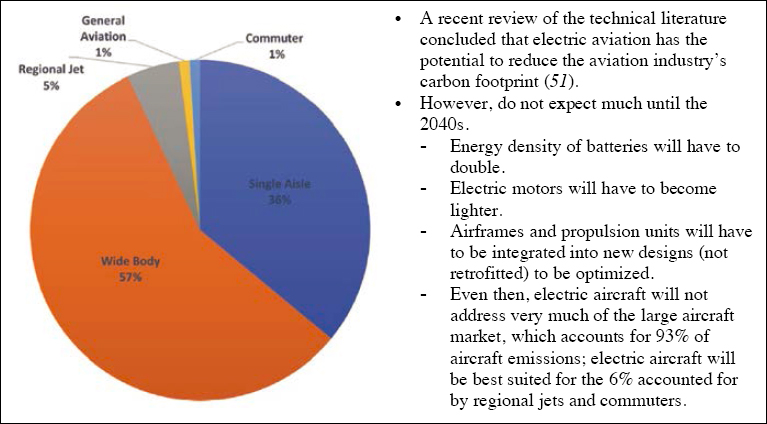

Carefully Consider the Potential Benefits of Electric Flight

Some airports may be tempted to promote the future of electric flight and the climate benefits it will create for the airport, the community, and the environment, but caution may be warranted.

The news is full of articles about unpiloted electric vehicles (one- or two-person flying machines powered by batteries). These vehicles may come to market in the next few years but will not make an appreciable impact on aviation carbon emissions. They simply will not account for very many trips, and most of the trips will be short-haul (50 to 100 miles) and thus be substitutes for automobiles.

A more relevant development is the use of batteries to power smaller commercial aircraft (up to 70 seats) for flights up to 500 miles. Battery technology is a very fast-moving field, so predicting when these aircraft might enter the market is difficult. However, electric aviation’s development and technical viability are highly dependent on technological advancement in three significant areas: battery technology; electric motor technology; and efficient, integrated airframe/propulsion design technology. These three technological areas are in their early stages of research, which introduces uncertainty in achieving feasible electric air travel. The following are some of the challenges facing these areas.

- For batteries, energy density must increase by a factor of two or more, with a reduction in weight.

- Electric motors must be created that are lighter and generate less heat.

- For airframe and propulsion design, retrofits are not a long-term solution even though there have been some successful retrofits of existing aircraft with electric motors. The Slovenian company Pipistrel successfully retrofitted a glider with an electric motor, becoming the first electric aircraft to get certified (46). The Vancouver-based airline Harbour Air and electric motor manufacturer MagniX retrofitted and flew a 62-year-old plane for 15 minutes in 2019.

- In September 2023, Burlington, Vermont-based BETA completed a 55-minute, international, all-electric flight from Plattsburgh, NY to Montreal, Canada.

- Conceptual designs of aircraft are mission specific. Therefore, retrofitting an existing airframe with electric motors limits the operational capability of the aircraft. New designs will take time and many years to certify—if experience with conventional aircraft certifications is a guide.

As illustrated in Figure 3-4, a 2016 study by the Committee on Propulsion and Energy Systems and others shows that these aircraft will address, at most, 5% to 6% of global aviation emissions in markets currently served by commuter aircraft and regional jets. In reality, it will take time for these aircraft to enter commercial fleets and account for a noticeable share of flying in those two categories. When they do, they will need access to sustainable electricity for charging in order to fully realize the benefits of electric flights. Companies such as BETA (47) and Joby (48) are currently addressing this issue by creating charging stations for airports.

However, given that they address issues related to environmental and noise pollution as well as the high operating costs of existing small regional aircraft, electric planes may deliver benefits in revitalizing smaller commuter airports that have lost access to commercial air services. This was highlighted in a NASA report on Regional Air Mobility, which concluded that “the local airport you may not even have known existed will soon be a catalyst for change in how you travel” (49).

Consider Pursuing and Publicizing Awards

Airports can pursue legitimate remediation projects that genuinely reduce their Scopes 1 and 2 emissions. While these projects are being planned, it may be useful to consider how they can be eligible for industry awards. Publicizing awards is a useful way to communicate to stakeholders and the general public that the airport is serious about reducing its carbon footprint.

Examples of Industry Awards

- Airports Going Green® (AGG) (https://agg.flychicago.com/Pages/default.aspx) includes an annual conference and awards program that is led by the Chicago Department of Aviation and cohosted by the American Association of Airport Executives (AAAE). Awards are given for the following:

- Outstanding Sustainability Infrastructure Development,

- Outstanding Sustainability Program, and

- Outstanding Tenant, Concession, or Vendor Program.

- The Airports Council International-North America (ACI-NA) (https://aci-na.secure-platform.com/a/page/awards/environmental) runs annual environmental and marketing and communications achievement award programs that include awards for smaller airports. Selection criteria for the awards are available on the website.

- Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) (https://www.usgbc.org/leed) is a program run by the U.S. Green Building Council founded in 1993 to construct better buildings with people and nature in mind. Airports across the world have pursued and achieved various levels of LEED—Silver, Gold, and Platinum—for their renovated or new-build terminals and other facilities.

- ENERGY STAR® (https://www.energystar.gov/), a joint program of the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Energy, aims to help consumers, businesses, and industry save money and protect the environment through adopting energy-efficient products and practices.