Engineering the Future for Sustainability: Measuring and Communicating Our Progress: Proceedings of a Forum (2024)

Chapter: 1 Engineering the Future for Sustainability

1

Engineering the Future for Sustainability

The human population took a million years to reach 300 million. Yet in just the past century, the number of people on the planet has grown from 2 billion to more than 8 billion. At present, it takes just 13 years to add a billion people to the planet. By 2100, the human population is expected to be 11 billion people, with an uncertainty of plus or minus 1 billion, depending mostly on what happens in Africa. “The Earth has never seen anything like this before,” said Arun Majumdar, the Jay Precourt Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Energy Science and Engineering at Stanford University and a senior fellow and former director of the Precourt Institute for Energy, during his plenary presentation at the 2023 annual meeting of the National Academy of Engineering. “This is not an exponential. This is a super-exponential. I call this the human tsunami.”

The rise in human population has been accompanied by an even greater rise in human consumption, whether measured in terms of global production of goods and services or global use of energy, 80 percent of which comes from fossil fuels. This super-exponential increase in consumption has radically improved the lives of billions of human beings in the last 100 years, Majumdar observed. However, it has already increased the temperature of Earth’s atmosphere by more than 1 degree Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures, with 2 degrees Celsius being the temperature increase commonly held to pose large and increasing risks to human life. At the current emission rate of 40 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide per year, enough carbon will be injected into the atmosphere over the next two decades to surpass 2 degrees of warming—and emissions are continuing to rise from the current level.

Similar observations can be made for water consumption. The use of the planet’s freshwater resources has increased dramatically over the past century, largely for agricultural production and particularly to support the

consumption of meat. Furthermore, the production of meat, and especially beef, increases the emission of methane into the atmosphere, which is an especially powerful greenhouse gas. “These are all interrelated,” said Majumdar. “What happens in energy affects water, what happens in water affects food, what happens in food affects biodiversity, which affects ecology, and that affects public health. And climate change adversely affects them all. They cannot be separated.”

In recent years, governments, companies, and international organizations have all pledged to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. All major nations have made a commitment to achieve net-zero emissions of carbon into the atmosphere by certain dates: 2045 for Germany, 2050 for the United States, 2060 for China, 2070 for India. More than 60 percent of the Fortune 500 companies have made a climate or sustainability commitment. The United Nations has established 17 Sustainable Development Goals designed to transform the world, including goals addressing clean water, clean energy, climate action, responsible consumption, and sustainable cities and communities.1

“The Earth has never seen anything like this before. I call this the human tsunami.”

– Arun Majumdar

The question, said Majumdar, is whether these commitments and goals will be met. “It’s like marriage. People have made a commitment, but the details have to be worked out. That’s what’s going on right now.”

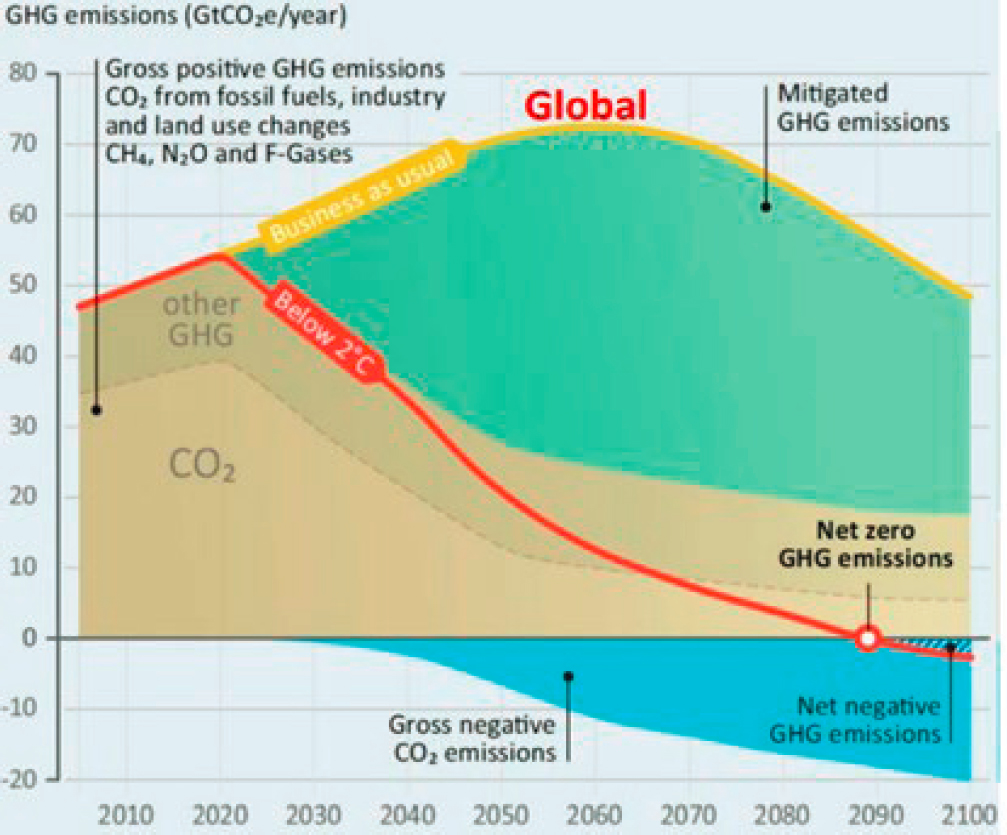

The National Academies and other organizations have spelled out what needs to be done to keep the global temperature from rising above 2 degrees (Figure 1). Emissions of both carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases need to drop quickly and substantially. Abatement technologies in use today, such as non-polluting energy sources and increases in energy efficiency, can achieve much of this reduction if applied much more broadly, and new technologies, such as clean hydrogen, could further reduce emissions. But reducing emissions, while necessary, is not sufficient, said Majumdar. Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases also need to be removed from the atmosphere to compensate for human activities that will be very difficult to decarbonize. This will be a difficult and expensive task. Majumdar pointed out that the weight of all 8 billion human beings alive today is about half a gigatonne, yet the quantities of atmospheric carbon dioxide that must be removed from the atmosphere are in the tens of gigatonnes per year. The

___________________

1 More information about the Sustainable Development Goals is available at https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals.

transition to net-zero carbon emissions will be “the largest transformation humanity has ever undertaken,” Majumdar observed.

THE OPPORTUNITIES FOR ENGINEERING

The needed transition to net zero also presents immediate and bountiful opportunities for engineers. “I wish I was an undergraduate student right now, because it is so exciting as an engineer to solve [these] problems,” Majumdar said.

Advances based on engineering are already abundant. Unconventional sources of natural gas have increased energy security while helping nations to move away from coal. Renewable electricity is available at the terawatthour scale and has become the world’s cheapest way to produce electricity. When the cost of batteries reaches $100 per kilowatt-hour, which Majumdar

predicted will be soon, battery technologies will be cost competitive with gasoline in cars without subsidies. LED lighting is now available for people who never had access to electricity or lighting before. Furthermore, the costs of energy-saving technologies are coming down dramatically. All of this “is amazing,” Majumdar observed.

But much more is needed. Multiday grid-scale storage is needed at one-tenth the current cost of lithium-ion batteries. Small modular nuclear power plants are needed at half of today’s costs. New refrigerants with zero greenhouse warming potential need to be developed. Net-zero buildings with net-zero costs, the decarbonization of industrial heat, the reimagining of steel, cement, and industrial processes, and the decarbonization of agriculture are all essential. To manage global carbon at the gigatonne scale, new ways need to be found to convert carbon dioxide into chemicals and fuels, the planet’s natural biological cycles need to be harnessed, and carbon needs to be captured from the atmosphere and sequestered underground.

Majumdar examined two of these imperatives in greater detail. The electrical grid has been called the greatest engineering achievement of the 20th century, “and it is,” he said. But the grid now has to change. It was not designed for solar or wind energy, and vulnerabilities to cybersecurity threats and increased wildfire threats need to be addressed.

The current grid is built around large generation centers, transmission to substations, and then distribution to homes and businesses. Jurisdictional boundaries have fragmented this system, with federal regulation of grid operators because they cross state boundaries but mostly statewide distribution of electricity. The current grid, now more than a century old, is being asked to absorb more than 50 percent renewable energy in some places—“it was never designed for that.” So much solar energy is available during the day that other energy sources need to ramp down, but they then need to ramp back up in the evening when the sun goes down. On the demand side, networked thermostats, electric vehicle charging, and home electrical generation panels injecting electricity back into the grid all need to be accommodated. “You have volatility on both sides. The question is, how do you manage the future?”

A new smart grid will require feedback loops and synergies created by information technologies and protected against cybersecurity attacks. Long-duration storage, such as pumped hydropower and compressed air storage, is needed to compensate for fluctuations in generation. When Majumdar was director of ARPA-E, the agency funded several storage technologies that are now in the pilot stage. “Hopefully, by the end of this decade, they’ll be commissioned into the grid, but this is still under development.”

“The question is, how do you manage the future?”

– Arun Majumdar

Fuels beyond electricity are also important, since not everything can be electrified and a total reliance on electricity could be risky if electrical supplies are for some reason interrupted. Today, a global network of pipelines, tankers, railcars, and trucks transport fossil fuels. New networks of comparable magnitude will be needed for clean fuels. Hydrogen has attracted a great deal of attention because it can be used to create plastics, fuels, chemicals, fertilizers, and many other products. But hydrogen has to be produced without creating greenhouse gases and it has to be low cost. The Department of Energy’s Hydrogen Earthshot challenge is seeking to reduce the cost of clean hydrogen to $1 per kilogram, but even at that price the technology would have to be immensely scaled up.2 Today, the world consumes about 0.1 gigatonnes of hydrogen per year. Producing that amount using current means of electrolysis would require more than the annual production of

___________________

2 More information about the Hydrogen Earthshot is available at https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-shot.

electricity in the United States and about half of the world’s entire supply of greenhouse-gas-free energy.

Producing hydrogen at the scale needed will require low-cost electrolyzers and a new infrastructure to generate and distribute hydrogen. Hydrogen could also be produced in other ways, such as splitting methane to produce hydrogen and solid carbon, or it may be available from other sources, such as geologic hydrogen stored in the Earth’s crust.

REMOVING CARBON FROM THE ATMOSPHERE

Atmospheric greenhouse gas removal at the gigatonne scale might involve accelerated chemical weathering of rocks, sequestration underground, biomass energy with carbon capture and storage, afforestation or reforestation, growing plants and crops, ocean alkalinization, or pumping the atmosphere through fans and removing the carbon dioxide, though all involve costs. As an example, Majumdar noted that removing a gigatonne of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere using this final method would require 2,000 terawatt-hours of electricity, which is more than the 2020 production of carbon-free electricity in the United States. The efficiency of this process could be improved through research and development, but very low-cost sources of clean energy would be needed to remove carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere at scale.

Today, crop residues remove about 10 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere every year, though this carbon is largely released back into the atmosphere when these residues are burned or decayed. If a low-cost way could be found of converting crop residues into soil carbon that was not susceptible to microbial degradation, this char could be put back into the earth to sequester carbon. “This has to be dirt cheap because you’re producing dirt.”

Majumdar also discussed methane, which today comes mostly from livestock production but also is emitted by the natural gas and oil infrastructure, wetlands, melting permafrost, and other sources. Atmospheric methane, which has also undergone an exponential rise in the past century, is such a powerful greenhouse gas that it is responsible for almost half the global warming that has occurred to date, Majumdar observed. The Department of Energy is starting to look at how to remove methane from the atmosphere, and this “is a topic that ought to be funded by the federal government.”

A HOLISTIC APPROACH

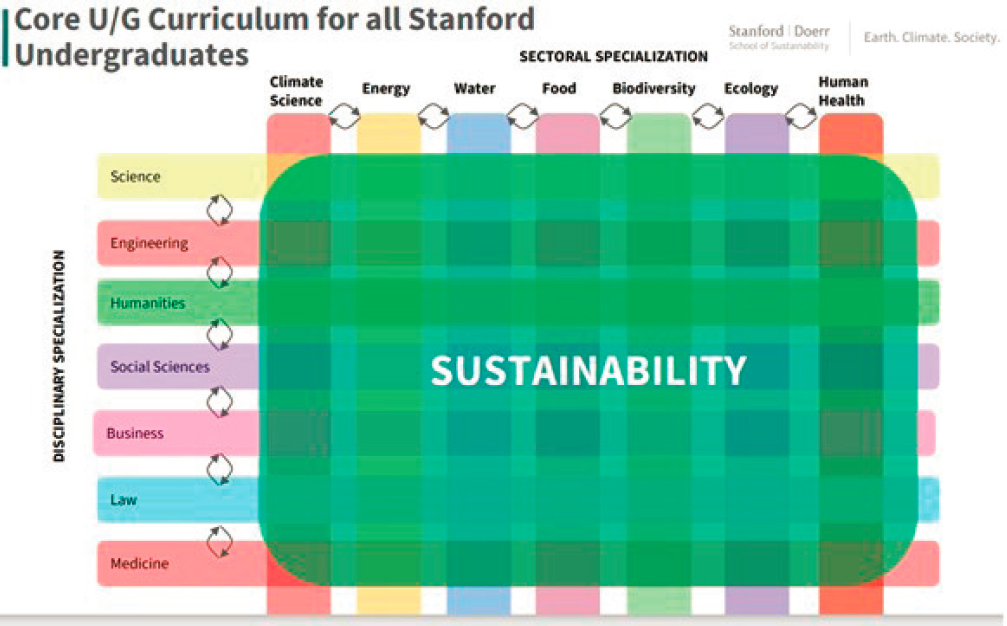

Because of the many interconnections among issues related to sustainability, the overall problem has to be approached holistically, Majumdar said. This is the goal of the newly created Doerr School of Sustainability, the first new school Stanford University has launched in 75 years.3 Its mission is to reimagine education, research, and service to the community in an all-campus way, because sustainability “cannot be separated into an engineering problem alone or a business problem or law; they’re all interrelated.”

The core undergraduate curriculum at Stanford has been reworked to reflect this cross-disciplinarity (Figure 2). Students work across disciplines and sectors on “the most interesting problems that people are grappling with,” Majumdar said. “Technology, business, law, markets, and all kinds [of specializations] converge together. That’s how we are looking at sustainability.”

___________________

3 More information about the Doerr School of Sustainability is available at https://sustainability.stanford.edu.

Sustainability is the defining challenge and opportunity of the 21st century, Majumdar concluded. It needs to be pursued, in the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., with the “fierce urgency of now.”

GAUGING SUSTAINABILITY AND RESILIENCE

Measuring indicators of sustainability is a major mission of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), said Sarah Kapnick, NOAA’s chief scientist, during the forum at the 2023 annual meeting of the National Academy of Engineering. NOAA has ships, aircraft, satellites, weather stations, autonomous oceanic and atmospheric vehicles, and buoys around the world. It takes data from these instruments, analyzes those data, and combines them with other datasets, using supercomputers and artificial intelligence, to make forecasts, predictions, and projections. “We’re constantly monitoring, around the world, all the different physical, chemical, and biological impacts of the environment and of climate variability and change,” Kapnick said.

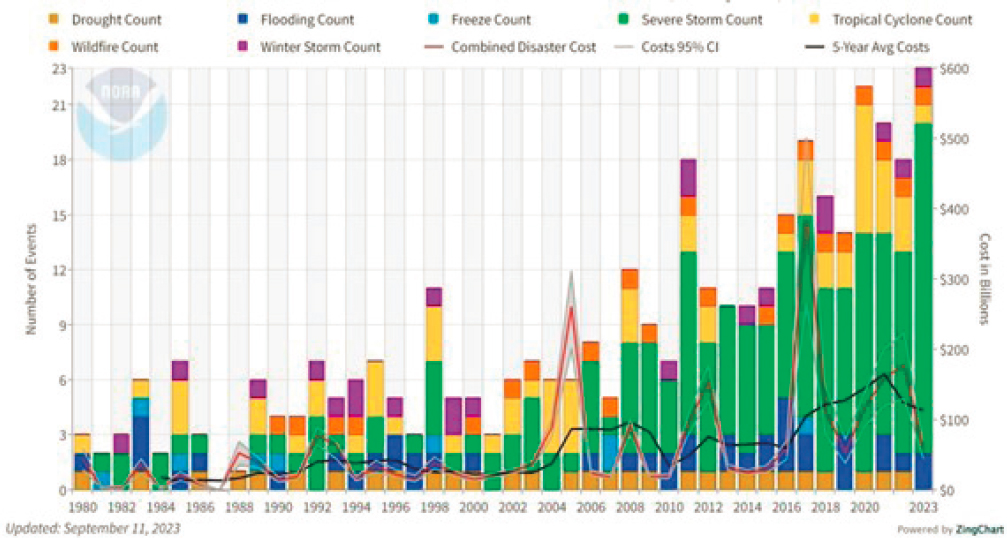

NOAA’s monthly state-of-the-climate report regularly generates global headlines—showing, for example, that July 2023 was not only the hottest July on record but broke the previous record by 0.3 degrees Celsius.4 “Usually, we only break those records by a thousandth of a degree,” Kapnick pointed out. This sudden increase in temperature “was a massive amount that shocked even the climate and data scientists who were doing this research.” Part of the reason for the heat was a developing El Niño, but this was occurring on top of a marine heat wave covering almost half the world’s oceans that was already leading to severe coral bleaching. NOAA also tracks other severe events, including hurricanes, extreme precipitation and flooding, and sea ice in the Arctic and Antarctic. Since 1980 it has been monitoring disasters that cost more than a billion dollars in the United States, and in the first eight months of 2023 the United States had already experienced 23 such disasters, more than in any previous year. NOAA issues long-range forecasts, which were calling for a dramatic increase in global temperatures in the winter of 2023–24. Indeed, at the time of the forum, there was a good chance that global temperatures, at the height of the ongoing El Niño,

“We need to build a climate-ready nation to be able to have resilience.”

– Sarah Kapnick

___________________

4 The report is available at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report.

would exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels in coming months. NOAA also has projected that sea level will rise about another foot around most of the United States by 2050, and by 1.5 feet in some places undergoing subsidence.

“We need to build a climate-ready nation to be able to have resilience in the face of these events,” Kapnick said. The week before the forum, the Biden-Harris administration hosted the first-ever White House Climate Resilience Summit, at which the nation’s first National Climate Resilience Framework was released.5 The Climate Mapping for Resilience and Adaptation portal, which is hosted by NOAA, provides real-time maps showing climate-related hazards and federal policies relevant to climate adaptation, along with federal funding opportunities that can help pay for climate resilience projects.6 NOAA also works with a wide variety of other government agencies and nongovernmental organizations to translate its projections into damages and costs and build resilience.

___________________

5 The framework is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/National-Climate-Resilience-Framework-FINAL.pdf.

6 The portal is available at https://resilience.climate.gov.

MEASURES OF RESILIENCE

Measuring progress toward climate mitigation or decarbonization, in terms of greenhouse gases avoided, reduced, or removed, is easier than measuring indicators of climate resilience, Kapnick observed. Measuring progress toward climate resilience requires many different metrics. Resilience hinges on such factors as flood-resilient buildings, electric grids resilient to extreme weather, fewer outage days, and the implementation of adaptation plans. “There’s a number of things that need to be done to build out our ability to measure that going forward.”

A variety of government agencies have focused on how to measure the economic effects of climate change, often in partnership with NOAA (Figure 3). The Congressional Budget Office has produced the report Budgetary Effects of Climate Change and of Potential Legislative Responses to It.7 The Council of Economic Advisors and Office of Management and Budget have issued Methodologies and Considerations for Integrating the Physical and Transition Risks of Climate Change into Macroeconomic Forecasting for the President’s Budget.8 The March 2023 Economic Report of the President contained a chapter entitled “Opportunities for Better Managing Weather Risk in the Changing Climate.”9 NOAA has worked with the Office of Science and Technology Policy and the Office of Management and Budget on the document National Strategy to Develop Statistics for Environmental-Economic Decisions: A U.S. System of Natural Capital Accounting and Associated Environmental-Economic Decisions.10 NOAA and the National Science Foundation have also created a research center in response to the needs of the insurance industry to bring climate information into catastrophe modeling.

More broadly, a whole-of-government project is underway to measure issues and impacts around climate. One part of this project—the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS)—is a partnership among NOAA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Housing and Urban Development, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Veterans Affairs, the National Park Service, and the Department of Health and Human Services. The

___________________

7 The report is available at https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-04/57019-Climate-Change.pdf.

8 The report is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2023/03/14/methodologies-and-considerations-for-integrating-the-physical-and-transition-risks-of-climate-change-into-macroeconomic-forecasting-for-the-presidents-budget.

9 The report is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/ERP-2023.pdf.

10 The report is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Natural-Capital-Accounting-Strategy-final.pdf.

website home (www.heat.gov) of the project provides information about current heat events and expected future heat. “Building those resilience plans requires all those different agencies to figure out how it affects their operations and how they can work with communities to build adaptation plans and then implement them,” said Kapnick.

Finally, NOAA has engaged in partnerships with a wide variety of nongovernmental organizations. For example, it has worked with the American Society of Civil Engineers, Microsoft, and the Electric Power Research Institute to insert considerations of climate into building codes, combine artificial intelligence with NOAA data to monitor fisheries, and apply information on how to build grids resilient to weather and climate.

APPLYING METRICS TO METHANE

David Allen, the Norbert Dietrich Welch Chair in Chemical Engineering, director of the Center for Energy and Environmental Resources, and co-director of the Energy Emissions Modeling and Data Lab at the University of Texas at Austin, used a specific product—natural gas—to look at how sustainability metrics can be applied to the evaluation of products. Global marketplaces, particularly those in the European Union, are demanding natural gas produced with low greenhouse gas emissions. Globally, about 2 percent of methane, which is the principal component of natural gas and a

potent greenhouse gas, is emitted between production at the wellhead and use at the burner tip, Allen reported. Eliminating this 0.1 gigatonne per year of methane emissions, which is the equivalent of 8 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide emissions, would be the equivalent of removing billions of cars from the world’s roads.

Detecting the emission of methane is complicated, in part because emissions are highly variable by region and source. However, rapid advances in remote sensing and data analytics have made global-scale, high-resolution measurements and reporting possible. A large variety of measurement systems are available, including aircraft equipped with sensors, drones, people at individual sites making measurements, permanent fixed sensors, and satellites. As a result of all these capabilities, “there is an explosion now of data,” said Allen.

Once data are collected, they have to be harmonized and transparently put into supply-chain and life-cycle frameworks, after which they need to be reported to global markets with independent verification. This is “a challenging system, but we have all the pieces that can be engineered together.”

TOWARD A GLOBAL METHANE REPORTING SYSTEM

Reports from the National Academies have made key contributions in understanding and responding to this issue. The 2018 report Anthropogenic

Methane Emissions in the United States: Improving Measurement, Monitoring, Reporting, and Development of Inventories described emissions,11 while the 2022 report Greenhouse Gas Emissions Information for Decision Making: A Framework Going Forward asked what is needed in measurement and reporting systems in general.12 The latter report identified six pillars that provide a common framework to evaluate information on current and future greenhouse gas emissions:

- Usability and timeliness—Information is comparable and responsive to decision-maker needs and available on time scales relevant to decision-making.

- Information transparency—Information is both publicly available and traceable by anyone.

- Evaluation and validation—Review, assessment, and comparison to independent datasets.

- Completeness—Comprehensive spatial and temporal coverage of greenhouse gas emissions information for the relevant geographic boundary.

- Inclusivity—Who is involved in GHG emissions information creation and who is covered by the information?

- Communication—Methodologies and assumptions are described in understandable forms, well documented, and openly accessible.

Currently, the US Department of Energy is working with an international consortium of natural gas importing and exporting countries to establish guidelines for a global reporting framework. “There are immense technical challenges to this, but the goal is big,” said Allen. “We can engineer these systems for measuring, reporting, and then independently verifying the sustainability features of our products.”

“We can engineer these systems for measuring, reporting, and then independently verifying the sustainability features of our products.”

– David Allen

___________________

11 The report is available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/anthropogenic-methane-emissions-in-the-united-states-improving-measurement-monitoring-reporting-and-development-of-inventories.

12 The report is available at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26641/greenhouse-gas-emissions-information-for-decision-making-a-framework-going.

FROM FRAMEWORKS TO STANDARDS

Many of the concepts and databases mentioned by Kapnick and Allen are inputs to what KPMG does for companies, said Erkan Erdem, partner and national leader of economic services practice at KPMG LLP. As a result of new laws and regulations, companies are preparing to report on the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) measures they have taken. Many companies have published sustainability reports in the past, but these were not based on a standardized set of rules. Today, governance is moving from frameworks that give direction to more prescriptive standards, including mandatory reporting.

Moving to standards requires more rigor and emphasis on data quality and validation, Erdem pointed out. It increases expectations for consistent and comparable measurement of not just climate-related impacts but the broader social impacts of investments and business decisions. Consumers and investors can then use standardized data on these impacts to make informed decisions.

On the environmental side, ESG measures include data about emissions, impacts on air and water pollution, waste management, and other indicators. On the social side, measures center more on diversity, equity, inclusion, pay equity, and a variety of human relations policies. Governance is less prioritized, with companies typically reporting on measures like board structure.

In the past, the diverse range of reporting standards has made comparisons across companies and markets challenging. Given the global attempt to address climate change and inequality, it is increasingly important that people have a common terminology when talking about sustainability. Fortunately, alignment is in progress, Erdem said.

CLIMATE SCENARIO MODELING

As one example, climate scenario modeling is a relatively new area that would benefit from standardized methodologies and definitions. Scenario analysis combines large amounts of data to create line items that would appear in financial statements concerning company financials, risk factors, future strategies, government policies, insurance assumptions, and so on. This requires similar and comparable data sources on risks, climate, timelines, and other factors.

“You may not be able to insure your factory or facility in California for wildfires in the future, and the same for hurricanes in Florida.”

– Erkan Erdem

The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) has provided an increasingly popular framework.13 In the United States, organizations have so far published voluntary TCFD reports or have disclosed similar information through the Carbon Disclosure Project, a nonprofit organization.14

The framework asks companies to make financial estimates for impacts related to their physical risks and transition risks. Relative to transition risks, physical risks are easier to understand and quantify using such measures as property replacement costs and business disruption expenses. Physical risks include data from NOAA’s US Climate Resilience Toolkit, for example, or from third-party providers on flooding risk, drought risk, wildfires, and so on.15

Measuring transition risks is more challenging. The easiest one to calculate is carbon pricing-related risk, given the expectation that a future carbon tax or carbon price will have a significant financial impact on companies. Various data sources provide an understanding of what carbon prices might be through the year 2050. Companies can then estimate the financial impact of those prices.

___________________

13 More information about the task force is available at https://www.fsb-tcfd.org.

14 More information about the Carbon Disclosure Project is available at https://www.cdp.net/en.

15 More information about the toolkit is available at https://toolkit.climate.gov.

A challenge companies face is knowing what they will need to do. For example, they rely on the insurance market, and regulators will probably include insurance provisions in their final rule, Erdem said. But “being able to insure your assets is becoming more and more challenging in this uncertain environment. You may not be able to insure your factory or facility in California for wildfires in the future, and the same for hurricanes in Florida.”

UNDERSTANDING THE RISKS

The number of companies that disclose their climate-related risks has been increasing, Erdem concluded, but it is still work in progress for most companies. Most disclosures are qualitative without modeling, and many lack methodological details. There is still much room for improvement for investors and financial services companies to have a better understanding of the risks associated with climate change.

Europe is ahead of the United States in requiring companies to report on their ESG metrics, though the Securities and Exchange Commission in the United States had a proposed rule on climate-related risks and opportunities that was expected to be finalized in 2024. At that point, all publicly traded companies will have to report on the financial impact of climate change, “which is a big change for companies out there,” Erdem said.