Agency Implementation of Alternative Contracting Methods (2024)

Chapter: Appendix A: Case Studies on Tool Selection and Implementation

Appendix A: Case Studies on Tool Selection and Implementation

Implementing Post-Award Contract Administration for Highway Projects Delivered Using Design–Build and Construction Manager–General Contractor Delivery Methods

INTRODUCTION

Research shows that D-B and construction manager–general contractor (CM-GC) project delivery can outperform design-bid-build (DBB) in large transportation projects in terms of improved project speed and reduced project cost growth influenced by elements such as communication channels, constructability input, risk allocation, reduced design errors, and third-party coordination (1–5). Nevertheless, some projects delivered using D-B and CM-GC are underperforming due to: (a) not selecting an appropriate project delivery method (6), (b) not procuring an effective contractor team to complete the project (7, 8); or (c) not managing the team or administering the contract in an integrated manner post-award (6–8). The first two challenges are being addressed by many researchers (see literature review), while this paper addresses the third challenge.

Authorization to use D-B and CM-GC in public projects has been increasing since the late 1980s when the TRB Task Force A2T51-Innovative Contracting Practices was established. Now almost all states have legislation authorizing D-B and about 45% authorizing CM-GC for transportation projects (9–11). The shift to use D-B and CM-GC is associated with the ability to integrate the contactor during design (6, 12), making these methods integrated methods of project delivery where the key stakeholders assume integrated roles. Such changes in roles and responsibilities for the owner and the contractor accompanied with the structural changes to the contract and cultural changes to team interactions highlight the need to provide owners with tools, training, and successful practices to help them with implementation. This need reflects the third identified challenge initially addressed by Molenaar et al. (9, 10) who, with two authors of this paper, developed NCHRP Research Report 939, Volumes 1, 2, and 3, three guidebooks containing strategies and 36 tools to guide post-award contract administration for D-B and CM-GC highway projects. This paper extends the work on contract administration tools by providing recommendations to efficiently implement tools to their full potential, since many practitioners and researchers have acknowledged the importance of appropriately implementing tools (13).

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) provides funds for federal highway programs over a five-year period (14), authorizing $1.2 trillion for transportation and infrastructure (15). D-B and CM-GC may be used to deliver infrastructure projects quickly with good quality, hence the need to provide guidance on how to best manage and administer them in post-award. D-B and CM-GC delivery methods may alter some stakeholder roles and responsibilities, rules of team engagement, and contract terms. Inefficient contract administration may lead to project issues. Hence, owners need practical guidance around how to select and implement suitable tools to administer these contracts in the post-award phase. Contract administration guidance is addressed in this paper.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND OBJECTIVES

The three challenges discussed earlier are implementation-related limitations to innovative delivery methods influenced by the new structure they impose on a project with untraditional techniques and with new roles and responsibilities for the stakeholders (6). The first identified challenge is choosing the right project delivery method. Tools developed to address this challenge include the FHWA Contracting Alternatives Suitability Evaluator (CASE) tool, the Project Delivery Selection Matrix, TxDOT Alternative Delivery Selection decision-support tool, Georgia DOT web-based application, and Risk-Based Project Delivery Selection Model for Highway Design and Construction (16–20). Some of these guidebooks are shown in Figure 1 under the front-end planning phase.

The second challenge is procuring contractors with relevant D-B or CM-GC experience and with appropriate qualifications is essential to their performance and the project’s success. Selecting an ineffective contractor can have a negative impact during the design phase (6). Several studies have documented qualifications-driven selection approaches and/or identified qualifications-based selection criteria to procure D-B and CM-GC contractors in public construction projects (32). Some of the guidebooks associated with these efforts for transportation projects are shown in Figure 1 under procurement.

In addition to a solid approach to choose the project delivery method and implementing a solid approach to procure the most-qualified contractor, post-award contract administration tools are also needed for effective project delivery where stakeholder roles and responsibilities

and contract terms are different than DBB. Existing literature focuses on pre-award guidance for the implementation of D-B and CM-GC with limited focus on post-award contract administration except for some individual efforts on specific contractual processes by a few DOTs (27–29) as summarized in Figure 1.

To address this gap, Molenaar et al. (9, 10) summarized best practices from 18 U.S. transportation agencies and described 36 tools to guide post-award contract administration for D-B and CM-GC highway projects. To disseminate this information, NCHRP funded training for DOT practitioners on how to best implement the contract administration tools. The authors led this training. During the training, data were collected and analyzed to address the research gap and to provide user-friendly guidance for post-award contract administration. Building on the guidebooks in NCHRP Research Report 939, Volumes 1, 2, and 3, the objectives of this paper are:

- Documenting the state of practice of DOT implementation of post-award contract administration tools;

- Developing a tool selection framework; and

- Adapting tools to specific needs and forming recommendations for tool implementation.

Throughout this paper, the D-B and CM-GC post-award contract administration tools will be referred to as the tools.

RESEARCH METHOD

Understanding the State of Practice for Implementing Post-award Contract Administration Tools

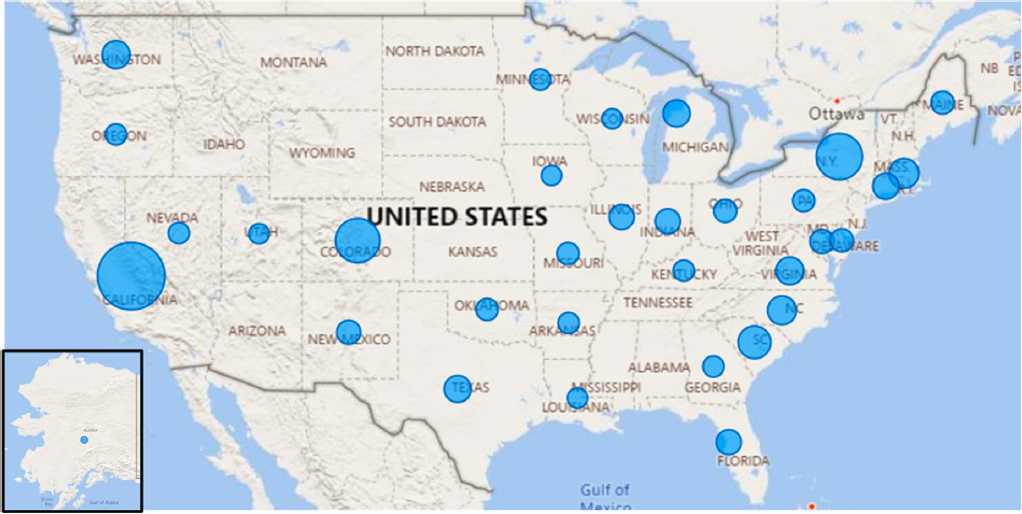

Eight remote workshops were hosted by the authors over a four-month period involving more than 300 participants including 235 highway agency personnel from 33 states and FHWA (Figure 2) with an average of 9 years of experience in innovative project delivery methods. These workshops provided training on the tools for all project phases (Sanboskani et al. (33)). Online, synchronous polls were used to gauge practitioners’ understanding; results from four key questions are discussed in the results and discussion section. These workshops also served as a prequalification step to select DOTs for more in-depth case studies on tool selection and tailored implementation of tools as described next.

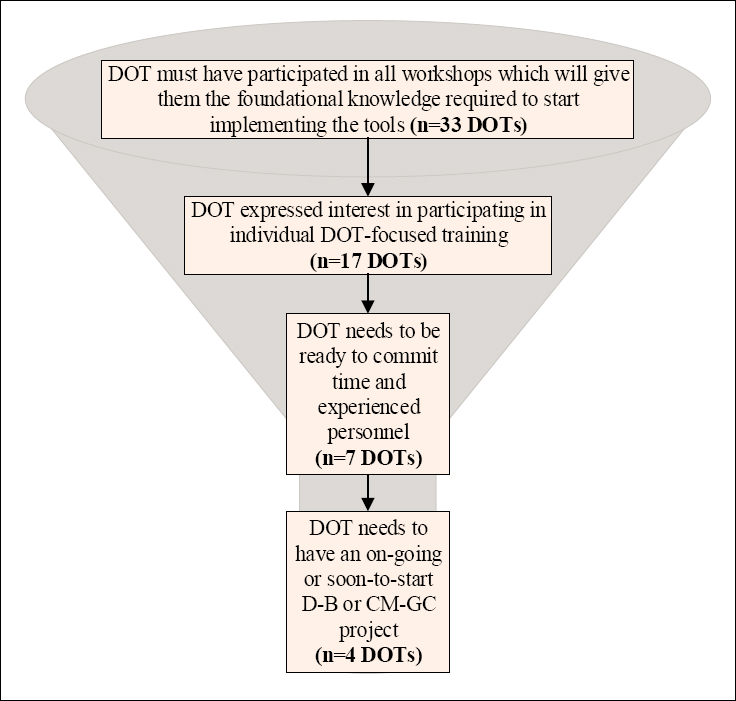

Case Studies for Tool Selection, Tailored Implementations, and Lessons Learned

A case study approach was employed to identify a series of recommendations on the tailored implementation of tools and to develop a framework for successful tool selection. The case study approach is effective for a specific scenario to generate rich findings and robust analysis of complex questions (34). The authors conducted four case studies to gather information on current implementation strategies by DOTs to deliver D-B and CM-GC projects and the associated post-award challenges. Criteria for identifying DOTs for case studies included data collected throughout the eight workshops and questions about the agency’s status regarding ongoing D-B or CM-GC projects. Figure 3 shows the criteria followed to select the DOT case studies. Projects are diverse, including a highway underpass and a large railroad bridge replacement, delivered using D-B and CM-GC methods, spanning different phases, and with DOT practitioners with different types and levels of innovative project delivery methods experiences.

Participation (remotely) involved a series of two interviews and one meeting, and a culminating workshop with all case study participants. Figure 4 documents the case study protocol that was followed according to Yin (34) and demonstrated on related topics by Harper et al. (35) and Molenaar et al. (36).

Several measures were taken to ensure validity. The questions used in the interviews were asked in a consistent manner by one person to ensure that the data collection procedures were accurately repeated for each case study. The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format where each session covered a certain topic and had a specific objective. Each case study was conducted over a five-month period. The long duration gave time for the DOTs to collect information, share it with the authors, and review assigned materials; and for the authors to analyze the shared information and develop recommendations. To meet the burden of proof, construct, internal, and external validity were controlled for (37) through:

- Collecting multiple types of evidence from multiple resources: interviews and contractual documents.

- Hosting the final workshop where the DOTs shared what they learned and how they are planning to move forward confirming that the objectives were met. Four other DOTs listened and commented on the outcomes of each DOT and no objections to the results were raised.

- Getting participant feedback on the tool selection framework and tailored recommendations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

State of Practice of Post-Award Contract Administration

The 36 D-B and CM-GC tools are successful practices used by DOTs and agencies (9, 10). Figure 5 shows the usage of the tools by the workshop participants before they received the training. Alignment tools are used most often (e.g., kickoff meeting, roles and responsibilities, and confidential one-on-one meeting) and tools dealing with risks and costs being the least used (CM-GC bid validation, risk pools, OPCC process, open book estimating). Co-location, partnering, and third-party coordination rank among the top 10 tools and are also mentioned in the literature (4, 38, 39).

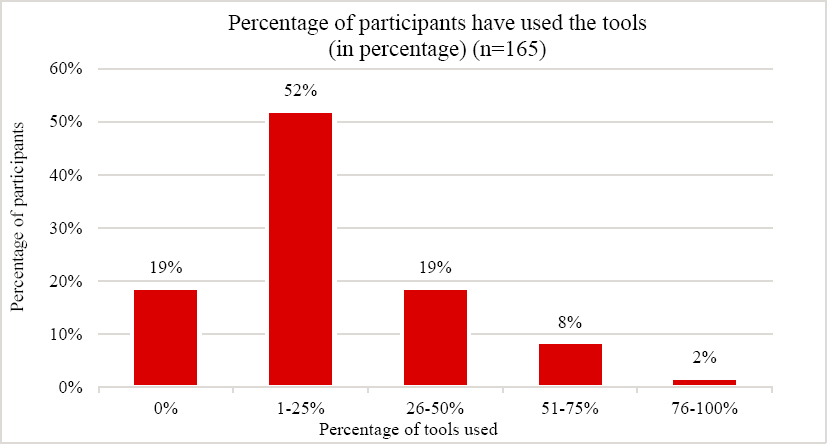

The initial knowledge of tools of each participant is represented by percentage reflecting the number of tools each participant is experienced with from the total number of tools available. The percentages of knowledge for each participant ranges from 0% meaning that the participant did not use any of the 36 tools, all the way to 89% or 32 out of the 36 tools. These percentages were put into bins of 25% ranges as shown in Figure 6. Most of the participants used less than 25% of the tools. In comparison, after the training, participants who attended all eight workshops have knowledge of all 36 tools.

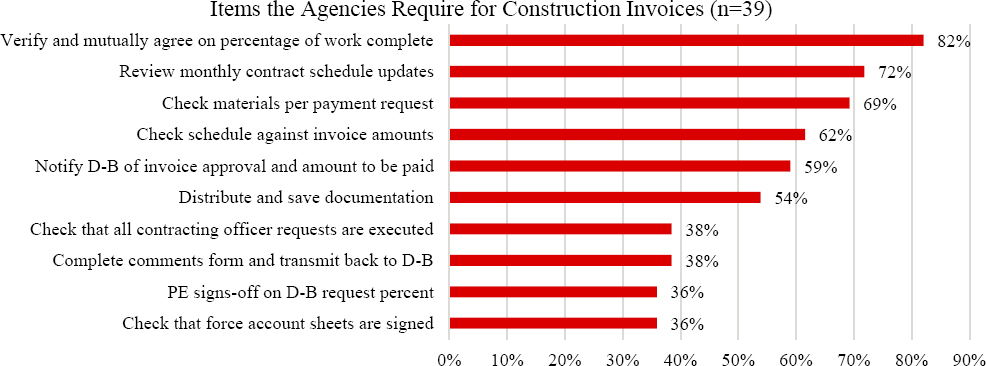

To explore how tools are being used by DOTs, one example tool that workshop participants were asked about is payment checklist. This tool is used in the close-out phase and helps guide invoice preparation and review. Figure 7 shows what the participants answered when asked about what items their agencies require for construction invoices as part of the payment checklist. This shows that DOTs have unique ways of implementing tools.

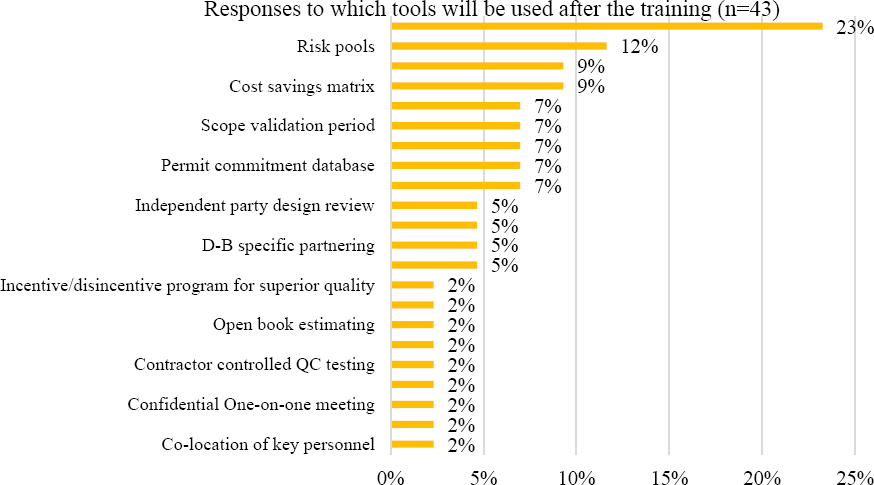

After completing the workshops, participants were asked “Based on what you learned in this training series, pick one or more tools you would like to propose or implement on your agency’s next D-B or CM-GC project.”. Results are summarized in Figure 8. Tools with the highest interest include risk pools, regulatory agency partnering, and cost savings matrix. Risk management is a critical challenge for DOTs. For example, Washington State DOT developed risk management processes and tools to guide risk identification, allocation, and control (40). Fourteen percent of participants replied they are interested in using all tools.

Case Studies on Tool Selection and Implementation

Tool Selection Framework

The tool selection framework (shown in Figure 9) was derived from the project characteristics identified in the guidebooks in NCHRP Research Report 939, Volumes 1, 2, and 3, and the selection processes used by the state DOTs participating in this study. This tool selection framework can be applied by any DOT following a funnel approach.

- First, the DOT considers the type of application: is the DOT trying to find a tool to implement right away on their ongoing project on a phase that they are just starting with? Or are they planning for a future project, and in that case, they can apply strategies spanning any phase where all tools can be available and can be tailored and integrated to solve an issue that the DOT is trying to address in their CM-GC or D-B implementation?

- Second, the DOT reviews the project information and refers to the guidebooks in NCHRP Research Report 939, Volumes 1, 2, and 3, to select an initial set of tools.

- Third, the DOT analyzes the unique aspects of the project, identifies current challenges, or reviews previous pain points in implementation.

The right side of Figure 9 illustrates an example of how the selection framework worked for a DOT with an ongoing CM-GC project. The first phase of this CM-GC project is a railroad bridge. As noted in Figure 9, all 32 tools applicable to CM-GC projects are available at Level 1 of the framework. The project is in the preconstruction phase and is identified as large and complex. After referring to the guidebooks in NCHRP Research Report 939, Volumes 1, 2, and 3, under the preconstruction phase and satisfying large and complex criteria, there are 21 available tools to choose from at Level 2. The DOT identified risk management (allocation and budget) as an important challenge, thus leading to the selection of risk pools at Level 3. Considerations when applying the framework include the experience and familiarity of the DOT personnel with innovative project delivery methods to make informed decisions, and the budget and resources available for the DOT to add a new tool to their implementation effort.

Examples of Tailoring Tools and Generalizable Implementation Recommendations

This sub-section discusses how the selected tools by the four DOTs using the tool selection framework (Figure 9) were applied to meet each DOT’s needs, provides the supporting recommendations that accompany the implementation of those tools to address the challenges and pain points, and shares lessons learned and recommendations applicable to other DOTs.

Case study from DOT 1:

The design–build project under consideration with DOT 1 is the expansion of a two-lane highway to four lanes in a rural area. Since DOT 1 had limited experience in interacting with FHWA on a large D-B project, and since this was an ongoing FHWA-funded project early in the alignment phase, DOT 1 applied Option A (FHWA is a new criterion/condition). This led to a list of potential tools including kickoff meeting, roles and responsibilities, glossary of terms, regulatory agency partnering, and FHWA involvement. Moreover, in past projects, DOT 1 had experienced some issues related to geotechnical considerations. Applying the framework’s Option C (looking at previous pain points) led to supplementing the tools with additional guidance from NCHRP Synthesis 429: Geotechnical Information Practices in Design–Build Projects (38). Suggestions include:

- Require the design-builder’s staff to include highly qualified experienced geotechnical personnel;

- Mandate the use of geotechnical design solutions in which the agency is confident;

- Assign the agency’s most-qualified geotechnical personnel to D-B project oversight; and

- Retain most, if not all, of the traditional quality management roles and responsibilities for the geotechnical features of the work.

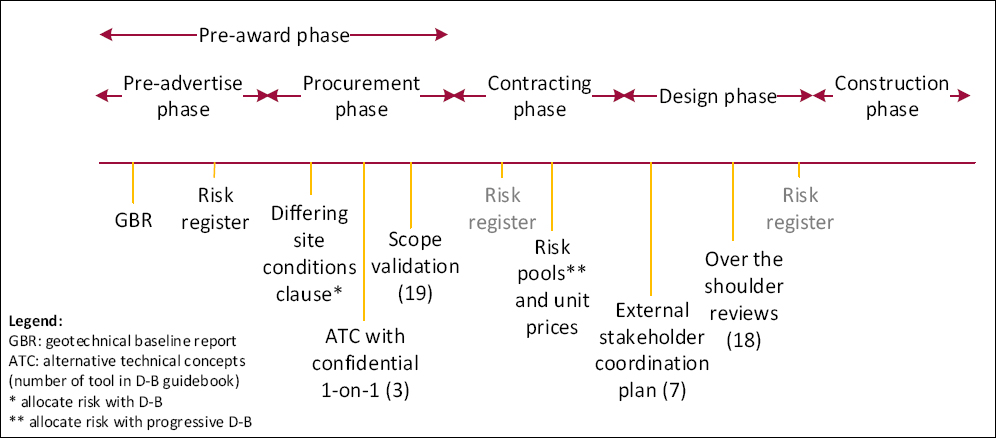

A project timeline that integrates relevant tools from the guidebooks in NCHRP Research Report 939, Volumes 1, 2, and 3, and guidance from NCHRP Synthesis 429 was co-developed by the authors and DOT 1 as shown in Figure 10. The geotechnical base report allows the DOT to survey area-specific information and share it with all proposers to reduce contingency and uncertainty in proposals. The development of a risk register can be started by the DOT even before the procurement process begins. Additionally, the D-B proposers can develop their own risk register. Once the DOT selects a D-B entity, the risk register can be merged and periodically updated. The differing site conditions clause helps reduce uncertainty for proposers by identifying what the DOT will do in case there are differing site conditions. Alternative technical concepts with confidential one-on-one meetings can be carried out in the procurement phase to give D-B proposers the opportunity to receive feedback on alternatives related to geotechnical issues. Scope validation can be used to confirm a mutual understanding of geotechnical considerations prior to signing the contract. This recommendation aligns with the findings of Castro-Nova et al. who also recommend aligning perceptions on geotechnical risks post-award through the scope validation period to provide an opportunity to share geotechnical risks (41). If progressive D-B is being implemented, then the risk register is used to translate the geotechnical risks values into risk pools. External stakeholder coordination plan and over the shoulder reviews can be ongoing throughout the design phase. External stakeholder coordination is essential since underground utilities work frequently involves geotechnical issues. Over the shoulder reviews can provide the D-B entity with the input and collaboration

from DOT staff with geotechnical expertise. Keep in mind that not all these tools have to be implemented, but now the DOT has developed a clear plan of various tools that can support resolving a critical issue for this project as well as future projects.

Recommendation: DOTs can develop timelines that show when tools are implemented and how multiple tools support shared objectives. While this timeline is for geotechnical considerations, similar timelines could also be developed for right of way acquisition, utility coordination, and environmental permitting.

Case study from DOT 2:

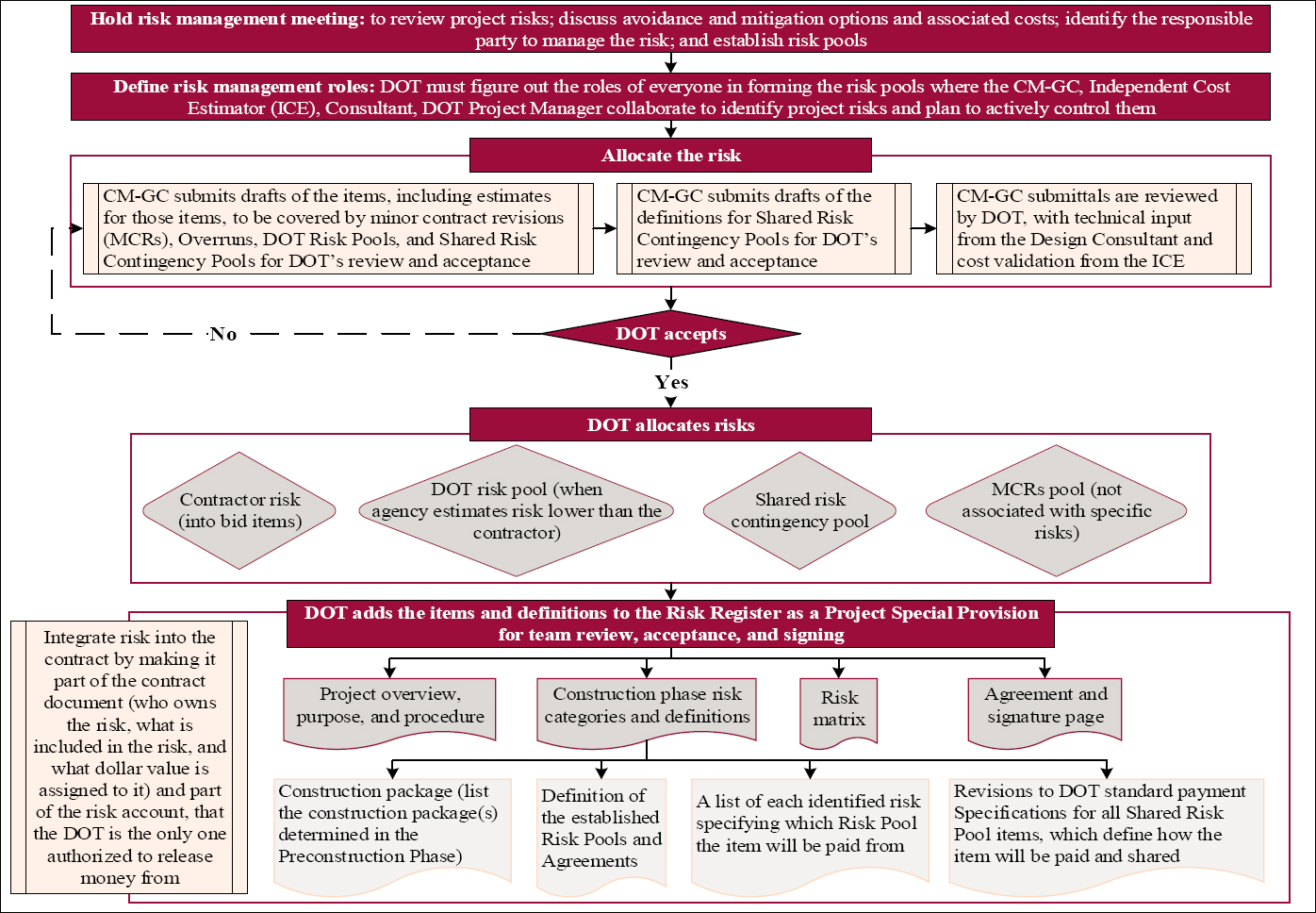

DOT 2 has a current CM-GC project for a highway underpass. In past CM-GC projects, the values placed on risks were not clearly conveyed in the contingency monies set aside in the contract. Applying the tool selection framework’s Option B (identifying current challenge), risk pools was the selected tool. Similarly, another agency (DOT 3) was working on a large railroad bridge replacement and was running into issues between the DOT and the CM-GC as to how contingency should be used. DOT 3 applied the framework’s Option C (previous pain points) and selected risk pools to proactively address this pain point in future projects. Both DOTs had some questions about implementing risk pools as described in NCHRP Research Report 939, Volume 2: Construction Manager–General Contractor Delivery, so some additional recommendations were developed to fit the needs of these DOTs. With input from both DOTs on their projects, in addition to reviewing other DOTs’ practices and CM-GC manuals (for instance, Colorado DOT includes a detailed section on risk registers), and using NCHRP Research Report 939, Volume 2, which includes a section on risk pools, a risk pools implementation flowchart (Figure 11) was co-developed by the authors, DOT 2, and DOT 3 (42). The flowchart in Figure 11 shows a method to efficiently allocate risks and define risk pool amounts. It is possible to make risk pools part of the CM-GC contract by establishing risk pool amounts, having a plan for when actual costs exceed risk pools, and integrating the risk pool and risk register into the contracts. Table 1 provides additional details for this approach, which some DOTs are using and other DOTs are still testing. In conjunction with the procedure in Figure 11 and approaches in Table 1, it is

advisable to refer to the list of common risks classified under 10 categories by Dicks and Molenaar for a comprehensive risk identification (40).

TABLE 1 Objectives and approaches to make risk pools contractual

| Objectives | Approach |

|---|---|

| A. Establish risk pool amounts with CM-GC prior to the CM-GC submitting a cost estimate |

|

| B. Plan for when the work on identified risks exceeds the amount set aside for that risk in the risk pool |

The contract should clearly specify how risk pool overruns are handled. There are several options, including:

|

| C. Plan for sharing the savings from unrealized risks. | Shared savings clauses may be appropriate in situations where there is a GMP with contract payment provisions that warrant an incentive for the contractor. Care should be taken when setting up a system to share savings from unrealized risks as this may motivate the contractor to inflate the estimated cost for handling the risk. |

| D. Integrate the risk register and risk pools in the construction contract | Attach to the risk register an agreement letter signed by leadership from the DOT and the contractor. Risks that are shared can be incorporated into the specifications. |

Recommendation: Risk pools should be applied to specific items instead of to the whole project, with the goal of minimizing contractor contingency. DOTs can use and adapt the risk pools flowchart. Investigating risks should begin early and be done in-depth by both the DOT and the contractor. Alignment can be enhanced by proactively making risk pool language contractual.

Case study from DOT 3:

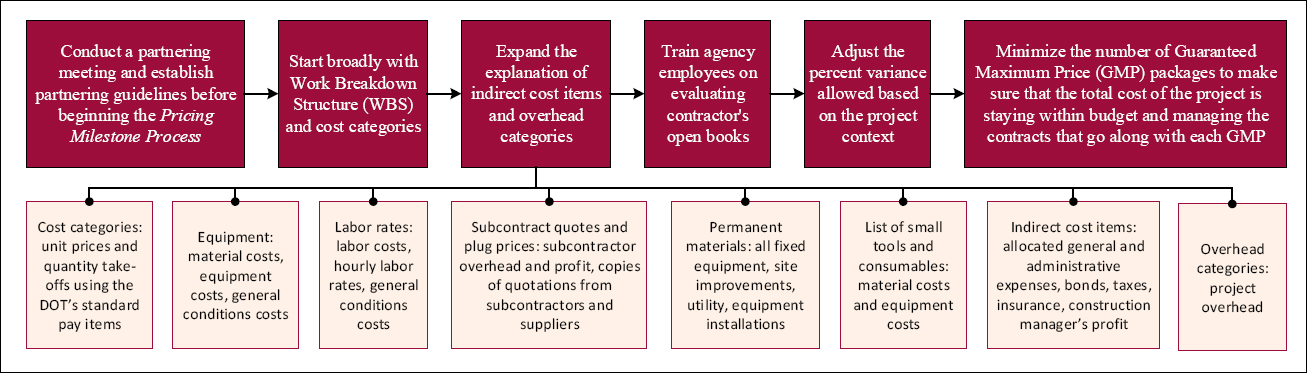

DOT 3 has a current CM-GC project for a railroad bridge where the DOT and the CM-GC are experiencing difficulties in agreeing on costs. Thus, applying Option B (identify current challenge) in the tool selection framework and focusing on the preconstruction phase of the NCHRP Research Report 939, Volume 2 guidebook, cost modeling approach is the selected tool. The tool first aims to align the independent cost estimator (ICE) and CM-GC on the assumptions used for cost calculations, which is the preferred starting place rather than focusing online item costs. For example, checking if both parties are working off the same work breakdown structure (WBS), same labor rates, same indirect cost items. DOT 3 found that productivity rates is an area that may lead to cost discrepancies. To address this issue, the DOT may consider conducting an open book review and obtaining feedback from ICE to help influence the discussions of cost. Another alternative is to request multiple subcontractors bid on selected items to ensure competitive pricing (if allowed in the contract). For example, a local subcontractor may provide a competitive price compared to a general contractor who has out of town per diem. The authors co-developed Figure 12 with DOT 3 to provide a detailed explanation of the indirect cost items and overhead categories to promote alignment on costs and avoid large cost discrepancies. Working toward cost model alignment can be more influential if discussions start before cost estimating begins.

Recommendations: DOTs can use or adapt the cost modeling approach flowchart shown in Figure 12, as appropriate. Developing narratives for assumptions gives context to what is necessary in the WBS and cost categories. This type of documentation supports alignment, especially for long duration projects where turnover in staff is likely. Reaching consensus between the DOT, ICE, and CM-GC cost estimates is facilitated by having a detailed cost modeling approach.

Case study from DOT 4:

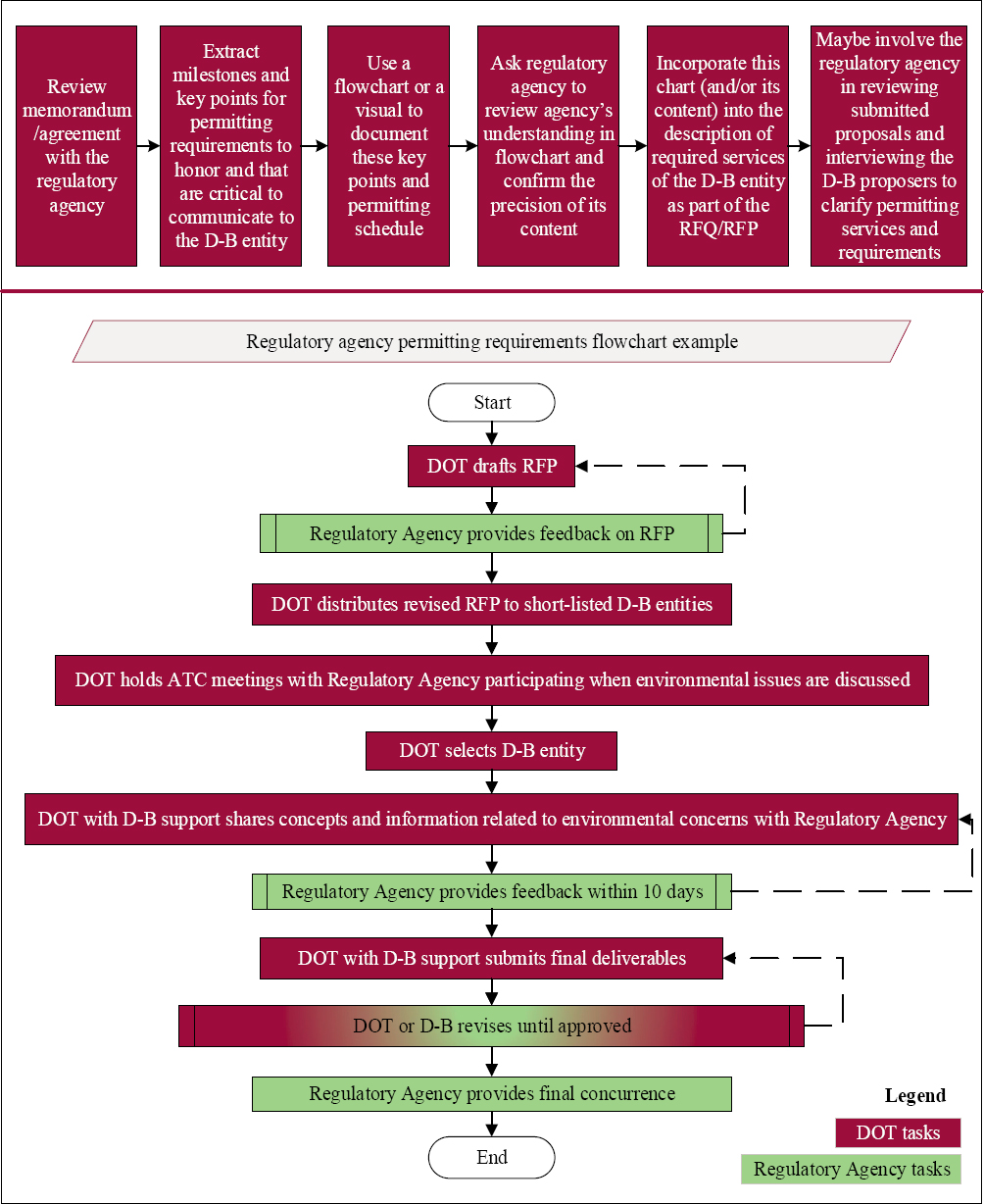

Based on a recent project, DOT 4 identified a critical pain point around regulatory agency partnering when implementing a D-B project. Specifically, the DOT is seeking to obtain environmental permits for a project footprint prior to procuring a D-B entity and prior to performing final design. This challenge is fairly common in D-B projects (43). Thus, applying Option C (identify a previous pain point) from the tool selection framework, and after studying the DOT’s partnering approach and documentation of this approach with the regulatory agency, the DOT selected the regulatory agency partnering tool along with related pre-award strategies to optimize implementation. One strategy is to include selection criteria suggested by the regulatory agency in the D-B request for qualifications (RFQ) or request for proposal (RFP). This approach has been used by the Idaho DOT, for instance. Permitting qualifications for a D-B RFQ/RFP can include (1) a narrative describing in detail the proposer’s permitting experience for similar facilities (ask them to share previous permitting plans); (2) the history of D-B entity with regulatory agencies (require references from regulatory agencies); and (3) a description of D-B entity’s permitting approach with regulatory agencies the DOT is working with for this project. Another option is to add specific criteria for permitting under qualifications and experience of key personnel, requiring resumes to substantiate qualifications and experience with similar/relevant permitting. Hence, the contractor is selected in part based on their expertise in working with agencies and obtaining permits.

Then in the post-award phases, the regulatory agency partnering tool is implemented to facilitate alignment of all key stakeholders (DOT, regulatory agency, and D-B entity) on the permitting requirements of the regulatory agency. Regulatory agency partnering consists of regular meetings and specified channels of communication to discuss ramifications of alternatives and possible solutions before submitting a detailed permit application. Thus, the authors with DOT 4 co-developed an approach shown in Figure 13, illustrating how regulatory agency partnering can be tailored to the DOT’s needs to highlight the agency requirements and align all stakeholders around these requirements and review time durations. Figure 13 illustrates how a DOT can adapt and expand upon tools to meet their project needs. DOT 4 can use this approach on current and future projects to help communicate a timeline from pre-award throughout the post-award phases with the goal of obtaining earlier concurrence and permits. While developing this approach, the DOT will meet with the regulatory agency to work through the D-B permitting process and make sure the final flowchart they will use with the D-B entity is consistent with the regulatory agency’s requirements and expectations. Additionally, the DOT will solicit input from the regulatory agency for the sections in the RFP that deal with permits. In the post-award phase, they will hold regular meetings with the agency and foster open and honest communication at the appropriate levels and up to the highest levels of the agencies, if necessary. Their goal is to have an agreement on how critical activities will take place to reduce uncertainty for the D-B during the procurement phase and be able to deliver the project successfully. If there is state legislation for progressive D-B (PDB), then PDB can be used to engage the D-B entity early in the environmental permitting process (43).

Recommendations: Proactively implementing post-award tools in pre-award planning and in the RFQ/RFP can facilitate post-award contract administration. The regulatory agency partnering approach in Figure 13 is one example of this. Specifically, permitting and partnering questions can be incorporated into the RFQ/RFP to ensure contractors have appropriate experience and expertise. DOTs can identify key regulatory agencies they partner with and

create flowcharts that detail relevant stakeholders and processes and the contractor’s role. This helps to reduce uncertainty and mitigate cost contingencies.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

DOTs need tools and techniques to effectively manage and administer D-B and CM-GC projects since roles and responsibilities, procedures, timelines, contract structure, and project delivery mindset are different from the traditional DBB. This paper contributes by extending the work of Molenaar et al. (9, 10) by providing practical guidance on implementing post-award contract administration tools to enhance alignment of stakeholders and project performance. This paper reports on the current state of practice and documents DOTs use and interest in innovative delivery tools. Through a structured case study approach, a tool selection framework was also developed to efficiently select appropriate tools. The case studies reveal how DOTs can adapt tools to the specific context of their unique projects and suggest generalizability to a variety of DOT contexts. Four key recommendations are summarized below.

- DOTs can develop timelines that show when tools are implemented and how multiple tools support shared objectives. While the timeline presented here is for geotechnical considerations, timelines could also be developed for right of way acquisition, utility coordination, and environmental permitting.

- Risk pools should be applied to specific items and not to the project as a whole, with the goal of minimizing contractor contingency. DOTs can use and adapt the risk pools flowchart. Investigating risks should begin early and be done in-depth with collaboration from the DOT and the contractor. Alignment can be enhanced by proactively making risk pools language contractual.

- DOTs can use or adapt the cost modeling approach flowchart developed here. Developing narratives for assumptions gives context to what is necessary in the WBS and cost categories. This type of documentation supports alignment, especially for long duration projects. Reaching consensus between DOT, ICE, and CM-GC cost estimates is facilitated by having a detailed cost modeling approach.

- Proactively implementing post-award tools in pre-award planning and in the RFQ/RFP can facilitate contract administration. The regulatory agency partnering approach discussed in this paper is one example. Specifically, permitting and partnering questions can be incorporated into the RFQ/RFP to ensure contractors have appropriate experience and expertise. DOTs can identify key regulatory agencies they partner with and create flow charts that detail relevant stakeholders and processes and the contractor’s roles within. This helps reduce uncertainty and mitigate cost contingencies.

In addition to the four key recommendations above, eight general lessons learned for tool implementation were derived from this study.

- Consider what will be needed for post-award contract administration and proactively integrate expectations clearly in the RFP, including third-party reviews, specifying channels of communication, and defining roles and responsibilities.

- Apply communication, integration, and collaboration with the executives and all key team members from the builder, designer, and owner to facilitate problem solving.

- Hire consultants, as needed, to supplement DOT staff in preparing the technical requirements in the contract.

- Make use of the professional community. Ask for help from other DOTs who have more and diverse experiences. Engage FHWA as needed. Collaborate with faculty researchers.

- Change incrementally. Keep some processes familiar when changing to innovative delivery as it helps with alignment, acceptance, and achieving the transition for the needed mindset.

- Train the project team on the available tools.

- Integrate contract administration tools and strategies into the DOT’s processes to get the process institutionalized by starting with smaller or less complex projects.

- Take small steps and add one tool at a time to a particular project and make templates that can be used in other projects.

Summary of Key Contributions

This study provided three types of contributions:

- Developing a tool selection framework that can be used by DOTs to select post-award contract administration tools helpful to their projects.

- Developing recommendations regarding the tailored implementation of the selected tools from the experience of DOTs, which can be replicated by other DOTs.

- Recognizing gaps in the delivery of D-B and CM-GC highway projects that can be further investigated.

A common issue identified by the DOTs is to clarify definitions of roles and responsibilities, common terminology, scope, etc. early on for stakeholders’ alignment as well as roles and responsibilities. Well-developed solicitation documents is a key step to establish alignment. This study offers guidance on adapting language in RFQ/RFP to address many of the challenges and pain points that DOTs are identifying. RFQ/RFPs can include specific qualifications criteria of the contractor, description of certain services, and inquiries about experiences of the contractor and evidence of past performance for certain tasks that emerge as part of the D-B and CM-GC delivery methods which require more and different engagements by stakeholders who hold integrated roles. Examples include references from regulatory agency partners, permitting approaches (e.g., environmental, ROW, etc.), and cost modeling approaches.

Other areas for further investigation include changes in pre-award processes informed by post-award contract administration, documentation of requirements, services, and qualifications of contractors, and risk allocation and integration in contract language.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates how DOTs can enhance contract administration of alternative delivery projects with strategic preparation of RFQ/RFPs, cost modeling approach and assumptions, risk assumptions, and permitting agencies schedules and requirements.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is based on the NCHRP 20-44(42) funded project. The authors would like to thank all guest speakers and DOT participants from the workshops and case studies.

REFERENCES

1. Sullivan, J., M. E. Asmar, J. Chalhoub, and H. Obeid. Two Decades of Performance Comparisons for Design-Build, Construction Manager at Risk, and Design-Bid-Build: Quantitative Analysis of the State of Knowledge on Project Cost, Schedule, and Quality. Journal of construction engineering and management, Vol. 143, No. 6, 2017, p. 04017009.

2. Sanboskani, H., N. Cho, M. E. Asmar, and S. Underwood. Evaluating the Ride Quality of Asphalt Concrete Pavements Delivered Using Design-Build. Presented at the Construction Research Congress 2018.

3. Papajohn, D., M. El Asmar, and K. R. Molenaar. Contract Administration Tools for Design-Build and Construction Manager/General Contractor Highway Projects. Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 35, No. 6, 2019, p. 04019028.

4. Gransberg, D., J. Shane, S. Anderson, C. Lopez del Puerto, and J. Schierholz. A Guidebook for Construction Manager-at-Risk Contracting for Highway Projects. NCHRP Project 10-85, 2013.

5. Abkarian, H., M. El Asmar, and S. Underwood. Impact of Alternative Project Delivery Systems on the International Roughness Index: Case Studies of Transportation Projects in the Western United States. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, Vol. 2630, 2017, pp. 76–84.

6. Franz, B., K. R. Molenaar, and B. A. Roberts. Revisiting Project Delivery System Performance from 1998 to 2018. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 146, No. 9, 2020, p. 04020100.

7. Shrestha, P. P., B. Davis, and G. M. Gad. Investigation of Legal Issues in Construction-Manager-at-Risk Projects: Case Study of Airport Projects. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2020, p. 04520022.

8. Riveros, C., A. L. Ruiz, H. A. Mesa, and J. A. Guevara. Critical Factors Influencing Early Contract Termination in Public Design–Build Projects in Developing and Emerging Economies. Buildings, Vol. 12, No. 5, 2022, p. 614.

9. Molenaar, K. R., D. Alleman, A. Therrien, K. Sheeran, M. El Asmar, and D. Papajohn. NCHRP Research Report 939: Guidebooks for Post-Award Contract Administration for Highway Projects Delivered Using Alternative Contracting Methods, Volume 2: Construction Manager–General Contractor Delivery. 2020.

10. Molenaar, K. R., D. Alleman, A. Therrien, K. Sheeran, M. El Asmar, and D. Papajohn. NCHRP Research Report 939: Guidebooks for Post-Award Contract Administration for Highway Projects Delivered Using Alternative Contracting Methods, Volume 1: Design–Build Delivery. Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, 2020. https://doi.org/10.17226/25686 2020.

11. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Highway Deicing: Comparing Salt and Calcium Magnesium Acetate: Comparing Salt and Calcium Magnesium Acetate -- Special Report 235. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 1991. https://doi.org/10.17226/11405.

12. El Asmar, M., A. S. Hanna, and W.-Y. Loh. Quantifying Performance for the Integrated Project Delivery System as Compared to Established Delivery Systems. Journal of construction engineering and management, Vol. 139, No. 11, 2013, p. 04013012.

13. Salem, O., J. Solomon, A. Genaidy, and I. Minkarah. Lean Construction: From Theory to Implementation. Journal of management in engineering, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2006, pp. 168–175.

14. Bipartisan Infrastructure Law - Funding | Federal Highway Administration. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/bipartisan-infrastructure-law/funding.cfm. Accessed Jul. 4, 2023.

15. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) Implementation Resources. https://www.gfoa.org/theinfrastructure-investment-and-jobs-act-iija-was. Accessed Jul. 4, 2023.

16. Khwaja, N., W. J. O’Brien, M. Martinez, B. Sankaran, J. T. O’Connor, and W. “Bill” Hale. Innovations in Project Delivery Method Selection Approach in the Texas Department of Transportation. Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 34, No. 6, 2018, p. 05018010.

17. Tran, D. Q., and K. R. Molenaar. Risk-Based Project Delivery Selection Model for Highway Design and Construction. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 141, No. 12, 2015, p. 04015041.

18. FHWA - Center for Innovative Finance Support - CASE: Analytical Tools. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/p3/toolkit/analytical_tools/case/. Accessed Jul. 4, 2023.

19. Georgia Department of Transportation. Design-Build Manual. 2014.

20. Colorado Department of Transportation. Project Delivery Selection Matrix. 2014.

21. New York State Department of Transportation. Design-Build Procedures Manual. 2005.

22. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. AASHTO Guide for Design-Build Procurement. 2008.

23. Molenaar; Gransberg; Scott; Downs; Ellis, K. D. S. D. R. Recommended AASHTO Design-Build Procurement Guide. 2005.

24. Minchin; Ptschelinzew; Migliaccio; Gatti; Atkins; Warn; Hostetler; Sylvester, E. L. G. U. K. T. G. A. Guide for Design Management on Design-Build and Construction Manager/General Contractor Projects. 2014.

25. Molenaar; Harper; Yugar-Arias, K. C. I. Guidebook for Selecting Alternative Contracting Methods for Roadway Projects: Project Delivery Methods, Procurement Procedures, and Payment Provisions. 2014.

26. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A Guidebook for the Evaluation of Project Delivery Methods. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009. https://doi.org/10.17226/14238.

27. Minnesota Department of Transportation. Design-Build Contract Management Administration Manual. 2015.

28. Oregon Department of Transportation. CM/GC Manual. Delivery and Operations Division/Construction Section, 2020.

29. Oregon Department of Transportaion. Design-Build Contract Administration Manual. Alternative Delivery Program, 2023.

30. Colorado Department of Transportation. 2016 CDOT Design-Build Manual, 2016.

31. Georgia Department of Transportation. Construction Manager / General Contractor Manual, 2023.

32. Sanboskani; El Asmar, H., Mounir. Qualifications-Based Selection Criteria for DB and CMAR Firms. In press.

33. Sanboskani; Papajohn; Cosentino; El Asmar, H. D. D. M. Implementation of Post-Award Contract Administration Tools in D-B and CM-GC Highway Projects: State of Practice in the Design Phase. Presented at the Construction Research Congress, IOWA, forthcoming.

34. Yin, R. K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Sage, 2009.

35. Harper, C. M., D. Tran, and E. Jaselskis. Exploring Instrumentation and Sensor Technologies for Highway Design and Construction Projects. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, Vol. 2674, No. 9, 2020, pp. 593–604.

36. Molenaar, K. R., S. M. Bogus, and J. M. Priestley. Design/Build for Water/Wastewater Facilities: State of the Industry Survey and Three Case Studies. Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2004, pp. 16–24.

37. Taylor, J. E., C. S. Dossick, and M. Garvin. Meeting the Burden of Proof with Case-Study Research. Journal of construction engineering and management, Vol. 137, No. 4, 2011, pp. 303–311.

38. Gransberg, D., and M. C. Loulakis. Geotechnical Information Practices in Design-Build Projects. 2012.

39. Dornan, D. L., N. Macek, K. R. Molenaar, J. Shane, and A. Bastias. Design-Build Effectiveness Study: As Required by TEA-21 Section 1307 (f). 2006.

40. Dicks, E. P., and K. R. Molenaar. Analysis of Washington State Department of Transportation Risks. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, Vol. 2677, No. 2, 2023, pp. 1690–1700.

41. Castro-Nova, I., G. Gad, A. Touran, B. Cetin, and D. Gransberg. Evaluating the Influence of Differing Geotechnical Risk Perceptions on Design-Build Highway Projects. ASCE-ASME Journal of Risk and Uncertainty in Engineering Systems, Part A: Civil Engineering, Vol. 4, No. 4, 2018, p. 04018038.

42. Colorado Department of Transportation. Construction Manager/General Contractor. 2015.

43. Gransberg, D. D., and K. R. Molenaar. Critical Comparison of Progressive Design-Build and Construction Manager/General Contractor Project Delivery Methods. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, Vol. 2673, No. 1, 2019, pp. 261–268.