Examining Prosecution: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 2 Research Findings and Promising Practices: Reducing Racial and Ethnic Disparities and Providing Alternatives to Criminal Justice Involvement

2

Research Findings and Promising Practices: Reducing Racial and Ethnic Disparities and Providing Alternatives to Criminal Justice Involvement

Brian D. Johnson, University of Maryland and workshop planning committee member, and Preeti Chauhan moderated sessions on the role of prosecutors in reducing disparities and providing alternatives to the criminal justice system. Discussions address factors that shape prosecutors’ decisions, ways prosecutors’ decisions intentionally alleviate or unintentionally exacerbate existing inequalities in the criminal legal system, and practices for implementing alternative approaches to incarceration without sacrificing public safety. Until recently, said Johnson, little information was available to answer these questions—prosecutorial decision making was a “black box” that was seldom examined in research and little understood outside the prosecutor community.

However, a noticeable shift has occurred in the past 20 years, said Johnson, in part due to historical factors (e.g., increasing incarceration in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s) that resulted in growing scrutiny of sentencing and correctional policies. Declining crime rates beginning in the early 1990s raised questions about the laws and practices that lead to those high incarceration rates. Despite recent decarceration efforts, said Johnson, the United States continues to have historically high imprisonment rates, with the burden of incarceration disproportionately borne by African American, Hispanic, and American Indian individuals (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2023). Increasingly, academics, practitioners, policymakers, and the public have begun calling for new approaches to address racial inequalities and to reduce the footprint of criminal justice involvement in America, said Johnson. Historically, these efforts have tended to focus narrowly on judges and their sentencing choices, but the focus has shifted as people have recognized the power of prosecutors to shape criminal justice outcomes. Quoting Wesley Bell, a former prosecutor in St. Louis County,

Johnson said that prosecutors can fill prisons, destroy lives, and exacerbate racial disparities, but they also have the power to do the opposite.

Over the past two decades, research efforts have significantly advanced the understanding of factors that shape prosecutors’ decision making, said Johnson. He highlighted three findings from this work. First, research findings remain mixed regarding racial and ethnic disparities, and many studies reveal that Black and Latino defendants do not necessarily receive the most punitive outcomes, despite conventional wisdom. In fact, he said, some research demonstrated that, under certain circumstances, prosecutors are exercising their discretion in ways that directly address racial injustice (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2022; Mitchell & Petersen, 2024; Shaffer, 2023).

Second, Johnson noted a nascent evidence base suggesting that racial disparities often emerge in alternatives to incarceration and other discretionary decisions related to diversion (e.g., Engen et al., 2003; Johnson & DiPietro, 2012; Nicosia et al., 2017). These disparities could be due to a lack of structure in the mechanisms used to identify diversion candidates or could be tied to other structural criteria that unintentionally disadvantage certain types of defendants, he suggested. Such criteria might include requirements related to criminal history records or requirements for defendants to pay for alternatives to incarceration. However, said Johnson, prosecutors’ offices are increasingly identifying and offering redress for inequities in such decisions.

The third research finding of note regards the cumulative and interacting nature of decision making in the criminal legal system. Johnson noted a growing consensus that prosecutors and other court actors make consequential decisions daily and that those decisions are inherently related to one another (e.g., Johnson et al., 2016; Kurlycheck & Johnson, 2019; Kutateladze et al., 2014). For example, recent work suggests that offices with a higher proportion of cases screened out at initial charging tend to have fewer case dismissals later in the process (Prosecutorial Performance Indicators, 2022). This suggests that a broad lens is required to examine the manifold complementary decisions that collectively shape case outcomes, said Johnson, as well as to fully grasp how prosecutorial discretion can be exercised to help address overarching inequality in the criminal legal system.

The goal of the first workshop sessions, noted Johnson, was to examine the evidence regarding the use of data-driven and evidence-based approaches in several areas: to address existing inequalities, to implement and test innovative policy solutions aimed at increasing

diversion alternatives, and to improve long-term outcomes for defendants. He noted a need to improve data transparency and accountability in prosecution, provide victims and community members with a meaningful voice in the process, and continue building community confidence in and perceptions of procedural justice in prosecution, all while working to reduce the footprint of incarceration without sacrificing public safety.

These goals are emerging across social and political contexts throughout the country and in prosecutors’ offices of varying sizes, said Johnson, driven by a growing appreciation and concern for the disproportionate impact of unintended criminal justice-related harms on certain racial and socioeconomic groups. Despite ongoing research challenges, he estimated that, over the last 25 years, more progress has been made in the study of prosecution than in any other domain of the criminal legal system. A growing number of large-scale, detailed data-collection efforts exist across diverse offices and geographic locales, conducted by a broad group of scholars including economists, political scientists, criminologists, legal scholars, and nonprofit research organizations. Efforts to evaluate data-driven policy changes and improve transparency and accountability have been aided by growth in research-practitioner partnerships, including those between prosecutors’ offices and academic research partners. Such partnerships employ innovations like public-facing dashboards, community town hall meetings, and self-published reports on racial and ethnic justice, Johnson said.

Despite the expansion in quasiexperimental and causal research on the effects of prosecutorial decision making, as well as in the number of rigorous evaluations of the effects of specific prosecutorial policies in various jurisdictions, said Johnson, several research and policy challenges remain. The overall evidence base for best practices in prosecution and policy recommendations remains underdeveloped, he noted. These workshop sessions represent an important step in identifying what is known, what remains to be learned, and what policies and practices appear to be most promising for reducing racial and ethnic disparities and encouraging alternatives to incarceration, he said.

Johnson and Chauhan moderated sessions (see Appendix B) during which speakers discussed the impact of prosecutorial decision points. Presentations covered topics including the salutary effects that declining to prosecute can have on racial disparities, results from diversion programs, the effectivity of prosecutorial charging decisions in offsetting inequalities from

earlier stages of the criminal justice pipeline, and the potential association of racial disparities with various outcomes, such as declinations, transfer, and diversion decisions.

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE ON PROSECUTION

Evidence on Case Declination

The first decision point for prosecutors, said Amanda Agan, Cornell University, is the decision whether to charge or decline to prosecute a case. This is a crucial initial step in the adjudication process in terms of both public safety and recidivism, she noted. The choice to prosecute or not to prosecute can be met with backlash from community members, police, and politicians with different perspectives, said Agan. From one perspective, defendants who are caught and punished for minor crimes may be less likely to commit future crimes. On the other hand, criminal records can have myriad consequences that may increase future offenses, including impacts on housing, employment, and access to public services. Within this context, Agan and her colleagues collaborated with a prosecutor’s office to analyze data from Suffolk County, Massachusetts (Boston) case management files. Comparing outcomes for prosecuted and nonprosecuted defendants showed that those who were not prosecuted were less likely to have another criminal complaint over the next two years.

However, said Agan, this decreased likelihood could be due to either the choice to not prosecute or to differences between cases that are prosecuted and those that are not prosecuted. For instance, explained Agan, individuals who are not prosecuted are more likely to be citizens, less likely to have a conviction in the previous year, and the crimes are more likely to be victimless and not involve disorder or theft. The different “styles” of prosecuted and unprosecuted cases, said Agan, makes the relationship between nonprosecution and a lower likelihood of recidivism difficult to understand. The practices of the Suffolk County court system presented an opportunity for research into this relationship.

Suffolk County assigns nonviolent misdemeanor complaints to arraignment courtrooms without regard to the identity of the arraigning Assistant District Attorney (ADA) or defendant, explained Agan. During the research sample period of 2004–2018, 315 ADAs rotated in and out of hearing arraignments. These ADAs varied in their rates of declining cases at arraignment, she said, with declination rates ranging from 10 percent to 50 percent and an average of 20.5 percent.

The mix of case characteristics was similar between low-leniency and high-leniency ADAs (as if randomly assigned), she explained, but the decisions the ADAs made were different. For cases with particularly strong or weak evidence, the assigned ADA may not have mattered, said Agan; these defendants were likely to be prosecuted (or not) regardless of which ADA made the decision. However, for many defendants, the random assignment of the ADA impacted whether the case was prosecuted. This natural experiment allowed researchers to examine these defendants and estimate the impact of the decision to prosecute (Agan et al., 2023).

Researchers looked at the two-year period after a decision to prosecute or not prosecute, and found that, for cases in which the assignment of the ADA mattered for the arraignment outcome, the decision to not prosecute a nonviolent misdemeanor case was associated with the following:

- A 58-percent decrease in the probability of a new criminal complaint;

- A 69-percent decrease in the number of new criminal complaints;

- A 67-percent decrease in the number of new misdemeanor complaints; and

- A 75-percent decrease in the number of new felony complaints.

These results, said Agan, were concentrated among first-time defendants who did not have measurable previous criminal legal contact in Suffolk County. This finding suggests that, for defendants with previous criminal records, additional leniency does not significantly decrease recidivism. Thus, the collateral consequences of criminal legal contact may be partially driving the recidivism effect. Defendants who can avoid the mark of a criminal record have decreased recidivism, but once defendants are “marked,” further leniency does not continue to reduce recidivism, she stated.

Limitations and Future Research Needed on Declination

Agan noted that these findings are based only on research from one county over one 14-year period. She and her colleagues are working with New York County, New York, to replicate and extend the research; further, similar research in other jurisdictions, including smaller towns and additional areas of the country, is warranted, she said. Additionally, this research focused only on cases of nonviolent misdemeanors, but further research could explore cases of violent

misdemeanors or felonies. Another limitation, said Agan, involved insufficient data on race and ethnicity, complicating the detection of outcome differences based on those characteristics. Finally, she said, the study only examined the impact of prosecutorial decisions on recidivism. Recidivism might be the easiest thing to measure, Agan emphasized, but it is not the only important outcome. Studying other outcomes, such as impacts on employment, housing, and well-being, would require linking data across agencies. While often difficult, this type of cross-agency collaboration is necessary to gain a full understanding of the consequences of prosecutorial decisions and practices, Agan said.

In response to a workshop participant’s question, Agan noted the difficulty of studying the impact of a declination policy on actual crime rates due to reporting and police referral issues. For example, police and the public may change their behavior in response to the lack of prosecution of certain crimes—for example, the public may not report such crimes, and the police may not bring those crimes to the prosecutor. On the other hand, she said, the opposite could occur—in attempt to demonstrate that nonviolent misdemeanors are a problem in the community, the public or the police could increasingly report or refer those crimes. Examine the impact of a declination policy on crime would necessitate a broader measure of crime that is not related to reporting, said Agan. For example, researchers could use data on retail shrinkage rates (i.e., loss of retail inventory), or 911 call information that is not brought to the prosecutor. Further research is warranted in this area, she said.

Evidence from Diversion Programs

Speakers provided an overview of diversion programs, including promising practices and research gaps. To set the stage for speaker presentations, Matthew Epperson, The University of Chicago and workshop planning committee member, briefly outlined the history and purpose of diversion programs.

Prosecutors face a variety of urgent issues that impact safety and justice in their jurisdictions, said Epperson. Considering the growing national interest in reducing incarceration and addressing racial disparities, prosecutors have a critical role to play. Many jurisdictions are grappling with an overwhelming number of lower-level or low-priority cases, and prosecutors are often tasked with balancing resources with case priority. Together, these circumstances have led many prosecutors to reenvision their roles in the criminal legal system and to rethink the

definition of successful prosecutorial outcomes, said Epperson. He noted the range of possible outcomes for a case, from dismissal to conviction, with diversion as one outcome within this range. Diversion programs were first developed in the 1930s for juveniles and began to be used in the adult system in the 1970s. The use of diversion programs has expanded over the last 10–15 years, he said.

Diversion programs can be thought of as a programmatic encapsulation of prosecutorial discretion, Epperson said. A prosecutor may exercise their discretion to divert certain classes of cases or certain types of defendants. When a defendant enters a diversion program, prosecution is put on hold, and successful completion of the program results in dismissal of charges. Program requirements range from minimal and short term to intensive and long term. Diversion can also be framed as a two-pronged approach, Epperson said. The first prong is removing the traditional prosecution process, along with the associated collateral consequences. The second prong is replacing prosecution with services that are more likely to meet the defendant’s needs. Diversion is a more varied and nuanced approach, he said, compared to the “blunt instrument of prosecution, conviction, and punishment.” Diversion also presents an opportunity for prosecutors’ offices to reduce the volume and cost of cases, allowing greater focus on higher-priority cases.

Evidence on diversion is promising but mixed, said Epperson. Many new programs only have evidence available for process outcomes like program completion. Prosecutor-led diversion programs tend to have high completion rates, often between 70–90 percent. Most research shows promising outcomes for those who complete the programs, although limitations exist in terms of appropriate comparison groups and study design rigor, he said (e.g., Cossyleon et al., 2017; Epperson et al., 2023; Rempel et al., 2018).

Research Findings: Diversion for Nonviolent Charges

Michael Rempel, Data Collaborative for Justice, explained that diversion programs began to expand in the 1990s, with a high growth mark for “problem-solving courts”—courts focused on one type of offense or type of person (e.g., drug courts or domestic violence courts)—in the early 2000s. Models of diversion programs include police-led, prosecutor-led, and court-led problem-solving courts (i.e., in which prosecutors serve as gatekeepers), explained Rempel. Over half (55%) of prosecutors have reported engaging in prosecutor-led diversion. A multisite evaluation of prosecutor-led diversion programs, funded by the National Institute of Justice

(NIJ), gathered data on 16 programs and evaluated the impact and cost of a subset of these programs (Rempel et al., 2018). Many participating prosecutors’ offices were in large jurisdictions where many individuals could potentially be diverted. The programs used a variety of models, Rempel said, including prefiling diversion, postfiling diversion, and mixed models. Unlike early diversion programs, which focused almost exclusively on people facing first-time misdemeanor charges, most of these programs allowed eligibility for people with prior convictions (14 programs) and/or felonies (9 programs). The programs largely did not use evidence-based practices or individualized treatments, said Rempel, relying instead on educational classes, community service, or therapy. One program in Milwaukee, however, utilized a structured risk assessment and tailored the intervention accordingly.2

Researchers examined the impact of six diversion programs on recidivism rates, said Rempel, and found reductions in rearrest in five programs, three of which were statistically significant. These results were unexpected—researchers anticipated a null effect because the programs were either too short to have an impact or used methods (e.g., education) that have not been proven effective. Why, Rempel asked, did these programs impact recidivism? He offered several potential answers based on focus groups with participants. First, participants felt a greater sense of procedural justice—that is, they felt they received compassion and fair treatment. Second, participants had a perceived sense of substantive justice; they appreciated the case dismissal and the avoidance of a criminal record. Third, participants did not suffer collateral harm from a conviction (e.g., stigma, socioeconomic harm, and psychological harm), which may have contributed to program impact. This suggests, said Rempel, that choosing not to prosecute could have the same impact on recidivism as a diversion program; that is, “doing nothing works.” State’s Attorney Kimberly Foxx, Cook County, Illinois, added that “doing nothing” may impact other parts of the system. For example, when Foxx chose to forego drug diversion programs and instead drop drug charges for those at low risk of reoffense, drug cases dropped significantly. She explained that law enforcement had no incentive to make the arrest in the first place since they knew prosecutors would not take the cases. While dropping the charges alarmed some people, she said, the alternative diversion programs were “performative” and not proven effective.

___________________

2 For more information, see Rempel et al., 2018, p. 18.

The NIJ-funded multistate study had some limitations, said Rempel—namely, the diversion programs largely did not use evidence-based practices, and nearly all excluded people facing violent charges. More research is warranted to determine which practices work, and whether these models are applicable to people charged with violence, he noted. Further, most diversion programs are measured against traditional prosecution rather than the “nothing counterfactual” (i.e., not prosecuting), which makes isolating the program’s impact difficult. Many included programs were small, said Rempel, resulting in a small sample size and limited impact on over-incarceration.

Research Findings: Effectiveness of Diversion in San Francisco

San Francisco has a robust set of postfiling, pretrial diversion programs, said Steven Raphael, University of California (UC), Berkley, and a long history of experimenting with reform. A research partnership between the San Francisco District Attorney’s (DA) Office and the California Policy Lab at UC Berkeley generated several studies over the past decade, including decision-point analysis of race disparities in criminal case processing, disparate impacts of California reforms on case dispositions by race, descriptive studies of existing diversion programs, causal analysis of adult diversion for felony cases, and a randomized controlled trial evaluation of a youth restorative justice program. Raphael highlighted two studies for discussion: one on the impact of felony diversion (Augustine et al., 2022), and another on the impact of a restorative justice program on recidivism (Shem-Tov et al., 2024).

For individuals served with felonies, San Francisco’s potential avenues for diversion include behavioral health court, drug court, veterans court, and young adult court. If an individual completes a diversion program, charges are generally dropped, Raphael said. People referred to diversion in San Francisco tend to have a long history of criminal involvement, he said, with high risk of recidivism. Some San Francisco judges use diversion programs heavily, while others are less likely to do so. As cases are randomly assigned to judges, studying the impact of diversion on outcomes is possible. Researchers examined approximately 17,000 felony cases that were eligible for diversion, with arrests between 2009–2017. One of the main differences identified, said Raphael, was that individuals in a diversion program spent far more time in the criminal justice system; diverted cases took about 250 days longer to be disposed than traditional cases did. Raphael explained that diversion programs involve “heavy intervention,” including the provision of services and frequent check-ins. San Francisco prosecutors told

researchers that they reserve diversion programs for individuals with serious criminal backgrounds; in general, first-time offenders with low-level felonies would not be offered diversion.

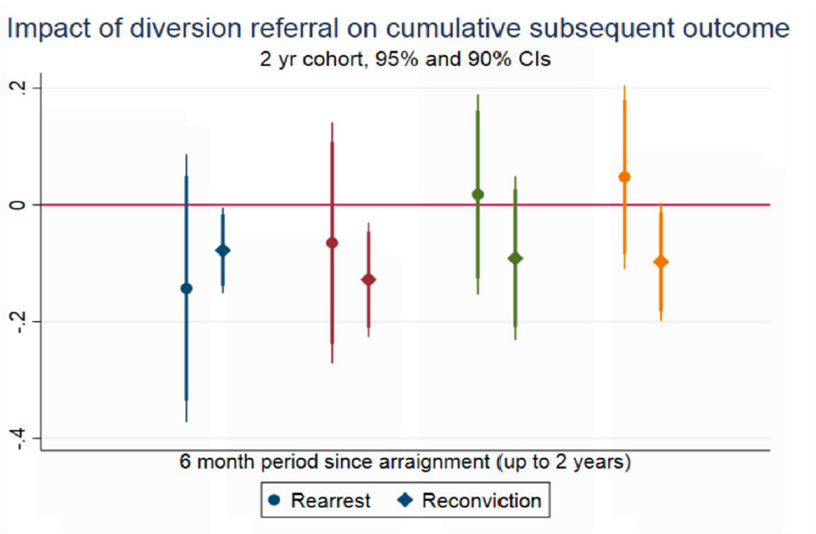

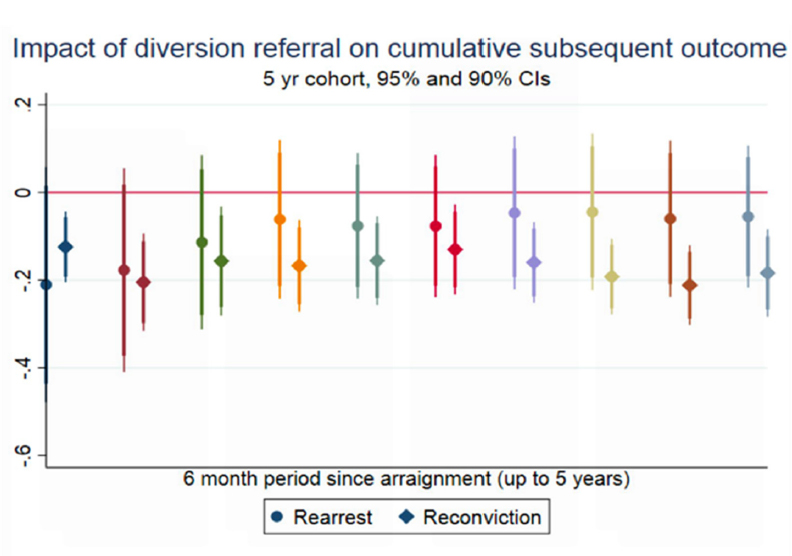

Researchers examined the impact of diversion on outcomes over two-year (Figure 2-1) and five-year (Figure 2-2) periods. Patterns were similar in both analyses, said Raphael, with individuals who completed diversion being somewhat less likely to be rearrested and even less likely to be reconvicted than those who received traditional adjudication. These results demonstrate that diversion appears to be more effective at reducing recidivism than traditional case adjudication.

NOTE: Pairs of bars along the x-axis represent increasing six-month intervals (i.e., 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months). In the figure title, “CIs” refer to confidence intervals.

SOURCE: Augustine et al., 2022; presented by Steven Raphael on September 23, 2024.

NOTE: Pairs of bars along the x-axis represent increasing six-month intervals (i.e., 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, etc.). In the figure title, “CIs” refer to confidence intervals.

SOURCE: Augustine et al., 2022; presented by Steven Raphael on September 23, 2024.

Next, Raphael discussed a second study examining the impact of a restorative justice program on recidivism. Make It Right (MIR) is a San Francisco youth restorative justice program that serves as an alternative to criminal prosecution. Youth arrested for a felony are eligible for the program if they are not affiliated with a gang, are not on probation or in detention at time of arrest, did not injure the victim or use a weapon, and have no prior offenses that count as a strike under California’s Three Strikes and You’re Out law.3 The program was studied using a randomized controlled trial from 2013–2019; with the victims’ consent, the trial randomized eligible youth to one of two groups: prosecution as usual or participation in MIR. Community Works West4 implemented the MIR program by facilitating a restorative justice conference between the victim and the implicated youth. The conference resulted in an agreement between victim and offender, with the goal of restoring the victim’s welfare. This could include repainting the victim’s graffitied garage or agreeing to attend school regularly, said Raphael. Another

___________________

3 For more information, see https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=PEN§ionNum=667

4 For more information, see https://communityworkswest.org/

group, Huckleberry Youth Center, managed the postconference case management and compliance monitoring. If the youth did not follow through on the agreement, said Raphael, he or she was sent back to the DA for prosecution. Law enforcement received no information about the program and was not involved, other than to dismiss charges if the youth successfully completed the program or to refile charges if not.

Of the 44 youth randomly assigned to traditional criminal prosecution, 43.2 percent were rearrested within 6 months and 56.8 percent were rearrested within 12 months. Of the 80 youth randomly assigned to MIR and found to be suitable for the program, 52 completed it and 26 did not. Rearrest numbers for those who did not complete MIR were similar to numbers for those who underwent traditional prosecution, with 34.6 percent rearrested within 6 months and 57.7 percent within 12 months. However, youth who completed MIR had significantly lower rearrest rates—only 11.5 percent were rearrested within 6 months and 19.2 percent within 12 months. Further, said Raphael, data showed that MIR was associated with a permanent reduction in rearrests, with arrest rates around 24 percentage points lower up to four years later.

Raphael cautioned that, while results are promising, the trial was small. He noted that the ADA in charge of youth filings was “very hesitant” about the program at the beginning and greatly restricted who could participate. However, by the end of the study, the ADA expressed their belief in the value of the MIR program.

Research Findings: Pathway to New Beginnings Program

Epperson described research conducted specifically on diversion programs for gun-related charges. In 2021, Epperson and his colleagues surveyed the country for gun diversion programs and found eight programs, nearly all of which were targeted at illegal gun possession (Sharif-Kazemi et al., 2021). The programs used a variety of approaches, including restorative justice, therapy, resource provision, and anger management and life skills training. Epperson and colleagues asked prosecutors about their motivations for using diversion programs. One reported motivation was a concern about racial disparities. Epperson noted that prosecutors are constantly navigating and balancing constituents’ public safety concerns with the high level of racial disparities in gun-related cases. Black men constitute an overwhelming proportion of individuals arrested with gun possession charges, said Epperson. Young Black men are “over-surveilled and over-policed,” and often have safety concerns that increase their likelihood of carrying a gun. Together, he said, these factors contribute to increased contact with the criminal justice system.

Another motivation for prosecutors, said Epperson, was the ineffectiveness of traditional prosecution and incarceration in gun possession cases for preventing gun violence. When prosecutors examined their data, said Epperson, they found that when people charged with low-level offenses were prosecuted to the fullest extent, many ended up returning to the system with escalated gun-related charges. Universal prosecution and incarceration may not be the appropriate response to every case, Epperson said; prosecutors are beginning to recognize this and pursue alternatives. Prosecutors using diversion also reported being motivated by the ability to differentiate between types of gun charges. Gun possession does not necessarily translate to gun violence, said Epperson, and diverting possession cases may enable prosecutors to focus on more serious cases.

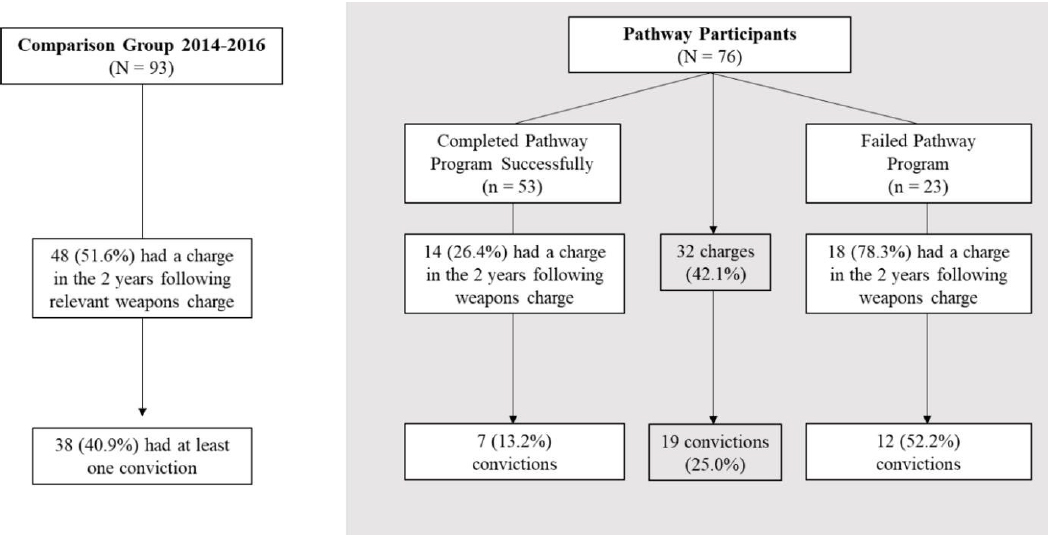

A Minneapolis prosecutor-led diversion program called Pathway to New Beginnings was established in 2017. Eligible individuals were those with a gross misdemeanor weapons offense, no prior felony convictions or gun/violence convictions, and were not currently on probation. Minneapolis City Attorney Susan Segal observed that many individuals arrested for gross misdemeanor weapons offenses were young adults with various levels of structural and individual disadvantage, noted Epperson. Since prosecuting and convicting these individuals improved neither their trajectory nor community safety, the diversion program was created as an alternative. The program consisted of two phases starting with a 12-week intensive phase of therapy, mentoring, and ongoing case management. The second phase, lasting two to six months, had less intensive programming and was followed by a year of probation with no programming. Individuals were terminated from the program if they failed to complete requirements or if they received a new charge related to guns or violence. Researchers examined recidivism rates for both successful and unsuccessful participants, along with a comparison group with similar characteristics (Figure 2-3) (Epperson et al., 2024). Of the 76 program participants, 53 (69.7%) successfully completed the program, and 23 (30%) were terminated due to loss of contact or engagement, a new charge, or other circumstances. Two years after the initial weapons charge, 51.6 percent of the comparison group had a charge involving a weapon or interpersonal violence, and 40.9 percent had a conviction. Of the participants who successfully completed the program, 26.4 percent had a charge, and 13.2 percent had a conviction. Epperson noted that the higher rates of charges and convictions for the failed program participants were unsurprising given that many failed participants were terminated due to a new charge.

SOURCE: Epperson et al., 2024; presentation by Matthew Epperson on September 23, 2024.

Diversion program graduates had significantly lower odds of arrest, conviction, and weapon/violence arrest within two years of the initial charge, said Epperson. These data suggest that a diversion program can be implemented without jeopardizing public safety, and that these programs may hold promise for reducing racial disparities. The program’s high graduation rate indicates its feasibility as an intervention, he said. Further research on gun diversion programs is currently underway, and programs are expanding eligibility to reach more potential participants. Areas for continued research, said Epperson, include measuring outcomes beyond recidivism, studying the impact of expungement, and examining the participant experience.

Promising Practice: GRO Community

God.Restoring.Order (GRO) Community is a community mental health center located on the far south side of Chicago, specializing in clinical services for boys and men—particularly boys and men of color, said Aaron Mallory, GRO Community.5 The organization launched a gun diversion program in 2022. Mallory outlined the program and the people it serves. Nationally, said Mallory, firearm offenders have a higher rate of recidivism (68%) than nonfirearm offenders

___________________

5 For more information see https://grocommunity.org/

(46.3%). Most people arrested for firearm offenses are African American men, who represent 74 percent of all unlawful use of weapon (UUW) charges in Illinois. Furthermore, 11 communities in Chicago—primarily on the south and west sides—make up one-third of the UUW cases in the state.

Mallory explained that his presentations at community forums on mental health led to a phone call from a State’s Attorney interested in creating a diversion program to address the large number of Black men in the criminal justice system. The two created a six-month gun diversion program that permitted defendants to have their charges dropped upon successful completion, said Mallory. The program begins with a referral from the State’s Attorney; individuals are then screened using the Ohio Risk Assessment and a mental health assessment. Program staff talk about expectations and requirements, and individuals are assigned a group counselor and an individual counselor. A graduation ceremony is held for individuals who complete the program. The intervention’s intensity varies depending on the individual’s risk level for recidivism. For example, individuals at low risk participate in group counseling twice a week and individual counseling every other week, while individuals at moderate-high risk have group counseling three times a week and weekly individual counseling. Group counseling began virtually because of the COVID-19 pandemic, said Mallory, and the virtual format worked well. The program also involves cognitive behavioral interventions, using a the Choose 24:7 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy curriculum. This curriculum, developed by GRO Community, helps people identify situations in which they feel they need a firearm, work on their thoughts within these settings, and develop ways to minimize or navigate those risky situations. The intervention uses role playing and group activities, said Mallory, and GRO Community is currently working to develop a virtual reality version of the program.

The first cohort of the gun diversion program had 73 participants, 71 of whom were African American, with a mean age of 27. Nearly all had high school diplomas (93%), many had some college (42%), and almost half (49%) were employed at the time of arrest. In Chicago, Mallory explained, there is a prevailing belief that people arrested for illegal gun possession are “bad people” who are involved in gangs or drugs. Through this program, he said, it became clear that most of these men were “individuals who are just trying to take care of their families.” The risk-need-responsivity assessment, which identifies factors that lead to recidivism, determined that a majority of participants were low risk for recidivism. As the program continued, said

Mallory, the State’s Attorney’s office began referring higher-risk individuals. Overall, 47 participants were low risk for recidivism, 20 at moderate risk, and 4 at high risk. Of the 73 participants, 63 completed the program and 10 did not complete it due to noncompliance or another charge.

As part of the diversion program, said Mallory, GRO Community conducted qualitative research to identify reasons why participants felt the need to carry a gun. Three main themes emerged: protection, legal cynicism, and permissibility of concealed carry in Illinois. One participant said that he had been shot before and did not want it to happen again; another participant said that he had previously been robbed at gunpoint and the police refused to respond. This feeling of legal cynicism was pervasive, said Mallory, with many participants expressing their belief that police would not protect them. Finally, some participants did not understand concealed carry laws and thought they could carry a gun as long as they could produce their Firearm Owner’s Identification (FOID) card. In fact, said Mallory, 63 percent of participants had a FOID card at the time of arrest.

In 2023, Illinois passed legislation to amend the Unified Code of Corrections,6 to make the First Time Weapons Offender Program permanent and change some of its eligibility criteria. The diversion program allows individuals over 21 facing charges for the first time to receive probation of 18–24 months instead of a prison sentence. This changed the gun diversion program, said Mallory, because the intrinsic motivation for individuals to participate has lessened. Defense attorneys may steer their clients away from the diversion program because it is more intensive than probation. Despite this challenge, GRO Community is expanding the gun diversion program into new jurisdictions, including other counties with different demographics. They are also increasing enrollment of individuals at moderate and high risk of recidivism. These expansions will allow GRO Community to collect more data on participants and understand which types of interventions work and how to best support participants. Research strategies may include a quasiexperimental design, a randomized controlled trial, qualitative analysis, and latent curve modeling.

___________________

6 For more information, see Illinois Senate Bill 0424: https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=0424&GAID=17&GA=103&DocTypeID=SB&LegID=144172&SessionID=112

EVIDENCE ON RACIAL AND ETHNIC DISPARITIES THROUGHOUT THE PROSECUTION PROCESS

Research Findings: Examining Disparities Using Case Processing Records from Florida

Racial and ethnic disparities may be created, increased, or decreased at each key decision point in the criminal justice process from arrest to final disposition, said Ojmarrh Mitchell, University of California, Irvine. Mitchell described research he and his colleagues conducted to examine potential disparities at some of these decision points (Mitchell et al., 2022). First, Mitchell described a Florida-based study using the state’s Sunshine Laws—regulations requiring certain government information be publicly available—to gain access to information on case processing and outcomes. Researchers identified a random sample of felonies filed in each county in 2017, coded the court records to document outcomes, and linked criminal history information to the defendants. Florida’s system for case processing, explained Mitchell, has three substantive stages: complaint, information, and adjudication. At the complaint stage, initial charges are filed, and bail is determined. At the information stage, the prosecutor decides whether to file charges as a felony, reduce to a misdemeanor, divert from prosecution, or dismiss the case. At adjudication, a plea agreement specifies the type and length of sanction, which are heavily influenced by negotiations with prosecutors, Mitchell said. Adjudication can be withheld for “uncoerced plea bargain,” meaning that a person is found guilty, but the sentence is not enacted. Cases generally result in one of seven outcomes, said Mitchell: case dismissal, transfer to a lower court, diversion from prosecution, withholding of adjudication, probation, jail, or prison. The features of this process give prosecutors great influence over case processing and sentencing outcomes, he said.

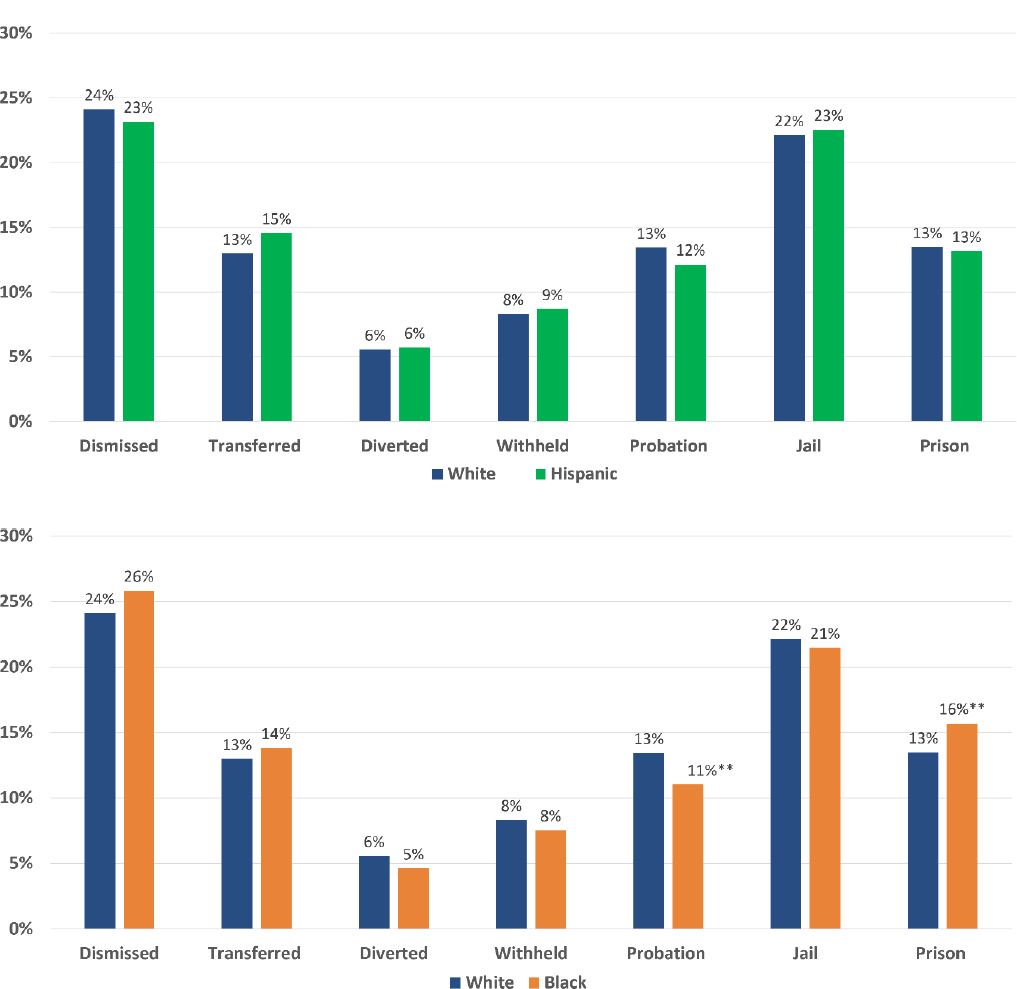

Mitchell and his colleagues analyzed the predicted probabilities of each case outcome, by race of the defendant, after controlling for defendant and case characteristics. In the Florida cases, regardless of defendants’ race and ethnicity, approximately 25 percent of cases resulted in dismissal and approximately 45 percent were either dismissed, transferred, or diverted. Comparison of Hispanic and White defendants, said Mitchell, revealed few meaningful differences. However, comparison of Black and White defendants showed few differences in the early stages, but racial disparities emerged during the sentencing phase (Figure 2-4).

Specifically, he said, Black defendants were more likely to be sentenced to prison and less likely to receive probation sentences.

SOURCE: Presentation by Ojmarrh Mitchell, September 23, 2024.

Findings describing no Hispanic disadvantage at any stage but a Black disadvantage during sentencing are similar to findings of a systematic review conducted by Mitchell and colleagues (Spohn et al., 2024a; 2024b). The review found that, in state courts, there is a small-to-modest racial/ethnic disadvantage in case filing and case dismissal, some racial/ethnic

disadvantage in charge reductions, and Black disadvantage in sentencing outcomes. Notably, said Mitchell, studies examining full case processing are rare.

Mitchell and colleagues examined the public statements and campaign promises of the elected chief prosecutors in each of Florida’s 20 judicial circuits (Mitchell et al., 2022). The researchers classified prosecutors as “progressive” if they met three of four criteria: (1) use of “smart”/data-driven decision making, (2) implementation of a conviction integrity unit, (3) a policy to categorically decline/divert certain low-level offenses, and (4) an express commitment to remove “poverty traps,” such as cash bail or nonfinancial driver’s license reinstatement. Based on these criteria, four chief prosecutors were deemed “progressive” and the remaining sixteen were classified as “conventional,” said Mitchell.

Comparison of progressive and conventional prosecutors found that cases adjudicated under progressive prosecutors were more likely to be dismissed, transferred, or diverted. The differences for each outcome were not statistically significant on their own, Mitchell explained, but taken together, the probability of not receiving a felony conviction was approximately 50 percent for progressive prosecutors and 40 percent for conventional prosecutors. This finding was only possible because the researchers examined the full set of case outcomes, Mitchell noted; this is an important approach to studying racial disparities and court outcomes, he stated.

Next, researchers examined whether racial and ethnic disparities at each stage differed under progressive and conventional prosecutors. They found few differences between White and Hispanic defendants, regardless of whether the prosecutor was progressive or conventional, said Mitchell. However, for Black defendants, outcomes varied significantly depending on prosecutor type. Under progressive prosecutors, there were more case dismissals for Black defendants than White, there was no disparity in prison sentences, and the disparity in probation sentences was halved. Cases adjudicated in jurisdictions headed by progressive prosecutors were more likely to be resolved in a manner that did not lead to felony conviction. These findings, said Mitchell, suggest that conventional chief prosecutors and their offices are responsible for the overall disparities that disadvantage Black defendants in case outcomes in Florida.

Research Findings: Impact of Prosecutorial Discretion on Racial Disparities

Racial disparities in incarceration have decreased over the last two decades, said Hannah Shaffer, Harvard Law School, but disparities still exist. Disparities in incarceration can be

measured by examining the ratio between the share of Black Americans who are incarcerated and the share of non-Black Americans who are incarcerated, Shaffer explained. In 2005, she said, Black Americans nationwide were almost six times more likely to be incarcerated; by 2020, this had decreased to just under four times more likely. The numbers and trends are similar in North Carolina, where Shaffer has conducted research (Shaffer, 2023).

Several possible reasons exist for the decline in disparities over time, said Shaffer. For example, police are changing their behavior and becoming less likely to arrest Black Americans relative to non-Black Americans. However, she said, while racial disparities in arrests have declined, incarceration disparities have declined more. Another possibility involves changes in the postarrest system, including changes to prosecutorial discretion. Isolating the role of discretion in the court system is difficult, said Shaffer, because case outcomes reflect more than just discretionary decisions. For instance, a prosecutor may be forced to reduce a defendant’s charge due to insufficient evidence.

To isolate the role of discretion, Shaffer and colleague looked at changes in prosecutors’ charge reductions around sharp changes in mandatory prison laws in North Carolina. Specifically, she said, her group used the North Carolina Sentencing Guidelines,7 in which defendants with longer criminal records qualify for a mandatory prison sentence while those with the same arrest charge but marginally shorter criminal records do not qualify. For example, Shaffer explained, a defendant who is arrested for selling cocaine and has 15 prior points—a sum of all prior convictions weighted by severity—qualifies for a mandatory prison sentence. A defendant arrested for the same offense but who has only 14 prior points does not qualify. Qualification depends on both the arrest charge and the sum of prior points, said Shaffer, so a prosecutor could reduce a charge such that a defendant would not qualify for a mandatory prison sentence. For defendants who do not qualify for a mandatory prison sentence, a reduction in charge would not impact qualification. By looking at defendants who are just below or just above the 15-point thresholds (i.e., to the left and right of the dotted line at “0 points from discontinuity”), said Shaffer, researchers can isolate prosecutorial discretion. She explained that while the incentive to reduce a charge exists only under one set of circumstances (i.e., to avoid a prison sentence), other reasons for reducing a charge—such as insufficient evidence—are present on both sides.

___________________

7 For more information, see Harrington & Shaffer, 2022, p. 36, Figure 2.

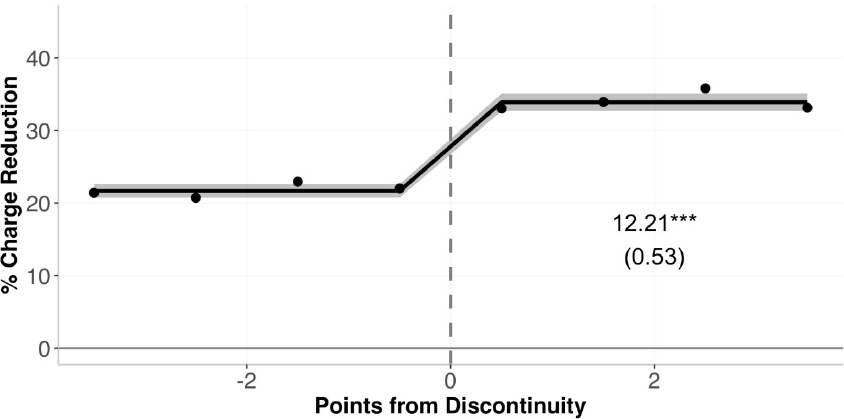

Analyzing data from North Carolina, Shaffer and colleagues found a clear, significant increase in charge reductions for individuals who would have otherwise qualified for mandatory prison sentences (Figure 2-5). In other words, for some defendants, prosecutors were exercising their discretion to reduce a defendant’s charge, to avoid mandatory prison.

NOTE: This figure depicts prosecutors’ charging responses to the mandatory-prison discontinuities in North Carolina’s sentencing grids in 1995-2009 and 2010-2019 (the prior-point thresholds for mandatory prison changed in 2010). The x-axis plots the defendant’s distance in prior points from a discontinuity given his arrest charge. The y-axis plots the percent of defendants whose arrest charge is reduced. The line and 95% error bands reflect the means in the four points to the right and left of the discontinuities. The annotated coefficient reflects the difference between these averages around the discontinuity. Standard errors are clustered by prosecutor. ***Significant at the 1% level; **5%; *10%.

SOURCE: Harrington & Shaffer, 2022; presentation by Hannah Shaffer on September 23, 2024.

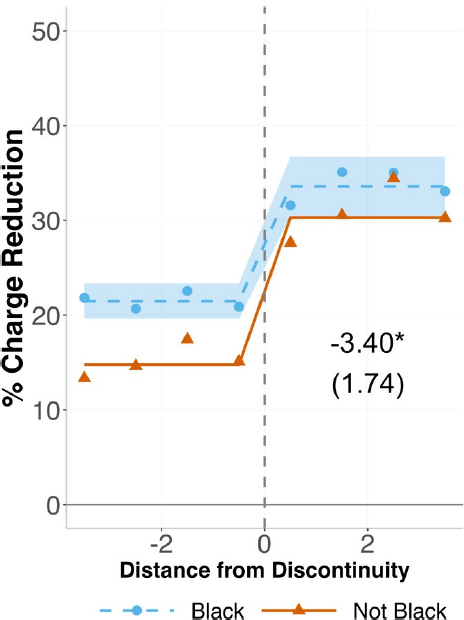

Shaffer and colleagues examined changes in charge reductions over time by race—that is, if prosecutors made different charge reduction decisions based on race, how did these differences change over time? From 1995–2010, Black defendants were significantly more likely to receive charge reductions in circumstances when it did not matter (i.e., when the decision made no difference in whether they qualified for a mandatory prison sentence). This difference could reflect the fact that cases against Black defendants at the arresting stage are weaker on average than for White defendants, said Shaffer. However, Black defendants were less likely to see a

charge reduction when it would prevent them from qualifying for a mandatory prison sentence (Figure 2-6). So, between 1995–2010 in North Carolina, prosecutors exercised their discretion in a way that compounded existing racial disparities in the criminal justice system, said Shaffer.

NOTE: The x-axis plots defendants’ distance from a discontinuity at arrest. The y-axis plots the percent of defendants whose arrest charge is reduced before sentencing. To the right of the dashed line, a charge reduction is necessary to avoid prison. The error bands reflect 95% confidence intervals comparing Black to non-Black defendants, with standard errors clustered by prosecutor. The annotated coefficients report the disparate charging response within four prior points of a discontinuity. *Significant at the 10% level.

SOURCE: Harrington & Shaffer, 2022; presentation by Hannah Shaffer on September 23, 2024.

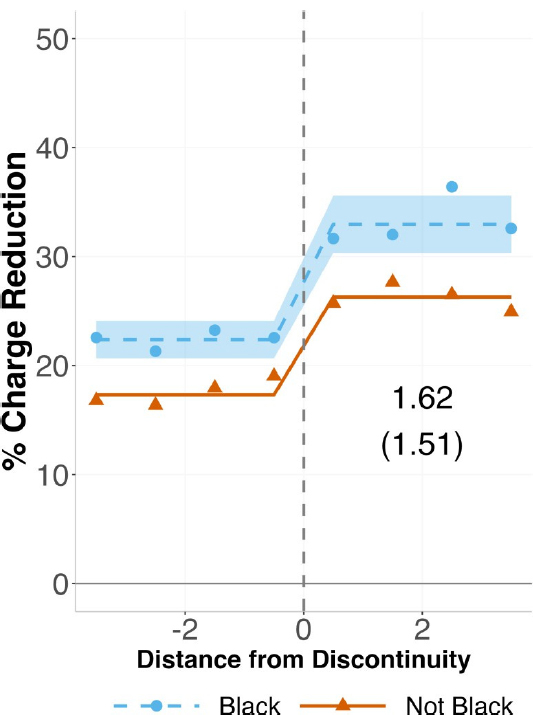

From 2006–2013, charge reductions were very similar by race on both sides of the dotted line representing discontinuity (Figure 2-7). Prosecutors were more likely to reduce charges when a reduction would help the defendant avoid mandatory prison than when a reduction would not make a difference, but the rate of reduction in both situations was similar for Black and non-

Black defendants. Here, said Shaffer, prosecutors exercised discretion in a way that passed on the disparities that already existed in the system, such as higher arrest rates for Black Americans.

NOTE: The x-axis plots defendants’ distance from a discontinuity at arrest. The y-axis plots the percent of defendants whose arrest charge is reduced before sentencing. To the right of the dashed line, a charge reduction is necessary to avoid prison. The error bands reflect 95% confidence intervals comparing Black to non-Black defendants, with standard errors clustered by prosecutor. The annotated coefficients report the disparate charging response within four prior points of a discontinuity.

SOURCE: Harrington & Shaffer, 2022; presentation by Hannah Shaffer on September 23, 2024.

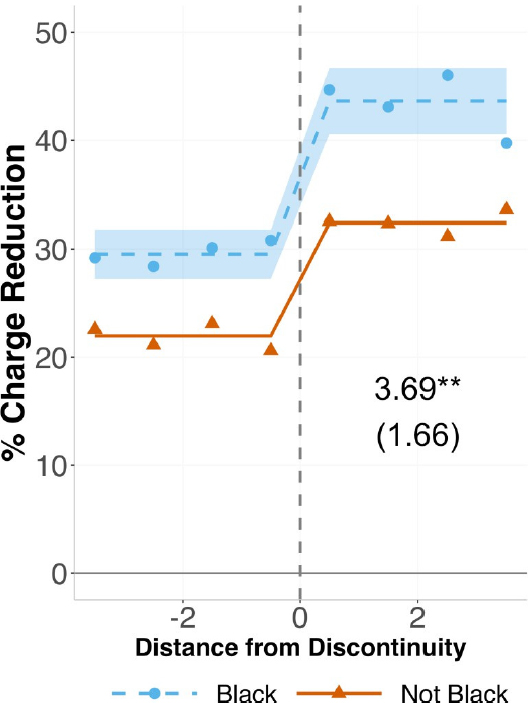

From 2014–2019 a different picture emerged, said Shaffer. During this time, Black defendants were more likely than non-Black defendants to receive a charge reduction when it helped them avoid a mandatory prison sentence (Figure 2-8). Here, she explained, prosecutors

exercised their discretion to offset or reduce the disparities established at the arrest stage. This trend may contribute to the decline in incarceration disparities, said Shaffer.

NOTE: The x-axis plots defendants’ distance from a discontinuity at arrest. The y-axis plots the percent of defendants whose arrest charge is reduced before sentencing. To the right of the dashed line, a charge reduction is necessary to avoid prison. The error bands reflect 95% confidence intervals comparing Black to non-Black defendants, with standard errors clustered by prosecutor. The annotated coefficients report the disparate charging response within four prior points of a discontinuity. **Significant at the 5% level.

SOURCE: Harrington & Shaffer, 2022; presentation by Hannah Shaffer on September 23, 2024.

Another potential explanation for the dramatic decline in incarceration disparities, said Shaffer, may be the way prosecutors interpret and respond to the criminal records of Black and White defendants. A very strong association exists between the length of a person’s prior

criminal record and their likelihood of being sentenced to prison; this is due in part to enhancements for prior convictions, but also to prosecutorial discretion. However, this association was weaker for Black defendants than White defendants, Shaffer said. For defendants with short criminal records, Black and White defendants had similar rates of being sentenced to prison. However, for those with long criminal records, White defendants were significantly more likely to be sentenced to prison than Black defendants. This suggests, said Shaffer, that the sentencing penalty for prior convictions is larger for White defendants.

Shaffer and colleague surveyed prosecutors in North Carolina to understand the empirical patterns they found. The survey presented data on racial disparities in incarceration in North Carolina and asked prosecutors what was driving these disparities. Specifically, the survey asked prosecutors the following: “Among all defendants who are arrested for any felony offense, an average Black defendant receives an active sentence more frequently than an average White defendant. In your view, how important are the following potential explanations in generating this difference?” Prosecutors used a scale from 0–100 to respond to the following options:

- Black defendants tend to have more severe past criminal conduct

- Black defendants tend to have more prior points

- Black defendants tend to have more severe current criminal conduct

- The current conduct of a Black defendant is often perceived to be more serious than the same conduct committed by a White defendant

- Black defendants tend to have lower-quality representation

Shaffer linked prosecutors’ responses to these questions to the court cases they handled (Shaffer, 2023). She found that prosecutors who believed disparities were due to differential criminal conduct by Black and White people treated Black and White defendants with similar criminal records similarly; that is, defendants were sentenced to prison at rates commensurate with their prior conviction points, regardless of race. Prosecutors who believed disparities in incarceration were due to bias in the system penalized White defendants more harshly than Black defendants. These differences, said Shaffer, drove the overall racial disparities in penalization of defendants with similar criminal records.

There are several potential ways to interpret these data and to hypothesize why certain prosecutors penalize White defendants more than Black defendants. One potential explanation, Shaffer said, is that prosecutors who perceive bias in the system see prior convictions of Black defendants as less meaningful signals of underlying criminality and instead as reflective of overpolicing or other biases. Prosecutors who see disparities in incarceration as reflecting differing criminal conduct between races, on the other hand, pass through the existing disparities established earlier in the criminal justice process. This work implies that individual prosecutors have enormous power over disparate outcomes, said Shaffer, and that some prosecutors have been exercising their discretion to offset existing disparities.

Promising Practices from Colorado: Reducing Disparities Across Prosecution Decision Points

As noted by other speakers, racial and ethnic disparities exist at various points in the prosecution process. Alexis King, District Attorney for Colorado’s First Judicial District, described an effort to address these disparities. Colorado’s First Judicial District contains approximately 600,000 people, with a sizeable Latino population (15%) and small Black population (1%). In 2021, King’s office set goals to identify disparities, to create a culture of data-driven decision making, and to increase engagement and public accountability. Disparities needed to be addressed in three specific areas, King explained.

First, data showed that, for driving charges that could result in up to $1,000 in fines and up to a year in county jail, White defendants were most likely to have charges dismissed and Hispanic defendants were least likely to have charges dismissed. Second, Hispanic individuals were most likely to plead guilty to low-level drug offenses. Third, Hispanic individuals were most likely to be incarcerated for property crimes, both high-level misdemeanors and low-level felonies. These disparities, said King, reflected both current systematic issues as well as “historical hangovers” in DA polices. While these disparities clearly needed addressing, said King, the types of cases involved did not typically receive much attention from prosecutors.

To make change, said King, efforts to secure support from the prosecutor’s office staff were necessary. The first step was to acknowledge and understand the impact of historical policies and practices. For example, prior limitations around deferred judgement and sentences were still influencing current office leadership, she said. Second, support was provided through all-staff training on disparities. A local researcher came to the office to help staff interpret and

understand disparities, disproportionality, and systemic drivers. Using a small-group approach with case examples helped with staff engagement, King noted. The third step was to motivate staff by asking middle management to solve problems and invest in change. Although this project began with a small group of high-level leaders said King, it was critical to galvanize the involvement of a larger group. Staff at all levels wanted to improve by altering their practices, King said; asking middle management to support these efforts channeled and capitalized on staff aspirations. The fourth step was to develop policies and practices to respond to identified disparities.

King and the prosecutor’s office staff identified several high-priority actions to address disparities. First, for driving and low-level drug possession offenses, they created a system for categorical diversion referrals. Prosecutors worried that this system could devalue their evaluation and discretion, said King, but the data made it clear that a more structured system could decrease disparity in outcomes. Second, the office established working groups to create plea guidance specific to motor vehicle theft and for the use of deferred judgement and sentences. This was the office’s first meaningful conversation about property crime, King noted, and it offered an opportunity to break established habits and patterns. The third action involved asking management to focus on property cases and to staff them the same way they would staff more serious crimes, such as aggravated robbery. Fourth, said King, a new data analyst position was created to provide chief deputies with immediate feedback on the impact of new practices on reducing disparities. Finally, the case management system is being reworked to insert equity prompts within case dispositions; the initial step in this process involves adding such prompts to the bond-setting decision-making process. While this system is still in development, King explained, the equity tool will capture systemic drivers when a bond decision is entered. This requirement provides structure to the bond decision, reducing reliance on the DA’s discretion. Taken together, said King, these actions will help prosecutors make better-informed decisions, obtain feedback about how cases are being evaluated, and understand which systematic drivers are (or are not) being considered in case resolution.

Discussion on Evidence, Promising Practices, and Racial and Ethnic Disparities

Following panelists’ presentations, planning committee members and workshop participants engaged in discussion moderated by Chauhan.

Scalability and Impact on Disparities

While the diversion programs discussed thus far in the workshop seem to have promising results, Chauhan noted, they all involved a small number of individuals. She asked panelists if diversion programs could be successfully scaled up to impact disparities in the criminal justice system, and whether other opportunities might be more promising. In San Francisco, Raphael responded, diversion is used in a small but not insubstantial number of cases—he estimated 10–20 percent. However, because the offenders are overwhelmingly Black and Hispanic, diversion could impact overall disparities. California has seen a significant narrowing of race disparities in incarceration, Raphael said, noting that this narrowing is due to changes in sentencing policy. Changing the “rules that everybody is operating under,” rather than relying on discretionary approaches, is likely the best path to reducing disparities, he said.

Rempel agreed that some large jurisdictions can divert a substantial number of cases but expressed his view that other types of policy change may be warranted to significantly impact disparities. For example, mandatory minimum sentences in New York disproportionately impact Black individuals. If these laws were changed, reducing racial disparities would be “mathematically inevitable.” While these initial programs are small, Epperson said, they can produce evidence that can be used to impact many more people. For example, Epperson and his colleagues researched a misdemeanor deferred prosecution program that was “extremely light touch,”8 consisting of only two sessions, and most participants did not recidivate. The effectiveness of a diversion program that does “almost nothing” suggests that prosecutors could decline to prosecute these types of cases and see similar results, he said.

Dependence on Prosecutors

Foxx observed that prosecutor-led diversion programs, by definition, rely on the discretion of individual prosecutors. She asked panelists to comment on how diversion programs can continue to succeed following changes in administration. Mallory responded that the solution lies in data and education. For example, Mallory and his colleagues found that most individuals facing gun charges are not involved in drugs or gangs and are instead looking to protect themselves and their families. By sharing these data and educating the community, the community can advocate for change and encourage prosecutors to use alternative approaches.

___________________

8 For a description of the program, see Epperson et al., 2023.

Evidence-Based Practice

Agan asked panelists for their thoughts on striking a balance between implementing evidence-based policies, innovating and trying new programs and responses, and generating evidence on a program’s effectiveness. Available literature predominately contains studies of people charged with nonviolent offenses and studies comparing traditional prosecution to diversion, Rempel responded. However, he said, some new programs are not yet backed by sufficient evidence, including programs that dismiss cases altogether and diversion for cases involving violence, such as the gun diversion model discussed during the session. Although these new models are promising, it would be a “misimpression to communicate that we already have a lot of evidence on current models,” Raphael said. He added that the ability to generate evidence is often conditional on access to both data and to DA’s offices that are willing to partner with researchers and experiment with their methods, even if the research “shows things that they do not like.” However, he noted that opportunities exist for researchers to be creative and to find natural experiments through which they can study causal questions. Mallory agreed that generating data requires collaborating with prosecutors who are willing to take risks. Although existing evidence is limited, sharing preliminary research with prosecutors can provide ideas about alternatives to prosecution and can help them make informed decisions about programs to implement, Mallory said.

PROSECUTORIAL PERSPECTIVES: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPLEMENTATION

Following the sessions highlighting research findings and promising practices, Marlene Biener, Association of Prosecuting Attorneys and workshop planning committee member, led panelists in a roundtable discussion to highlight perspectives from prosecutors and nonprofit leaders working closely with prosecutors on program implementation.

Prosecutor Perspective: Florida’s 17th Circuit

Florida’s 17th circuit, in Broward County, has over 2 million residents and the 16th largest prosecutor’s office in the United States, said Harold Pryor, State Attorney for Florida’s 17th Judicial Circuit. The county is highly diverse, with approximately one-third White residents, one-third Black residents, and one-third Hispanic residents. The prosecutor’s office

prosecutes crimes ranging from minor misdemeanors to first-degree premeditated murder, said Pryor; recent efforts aim to reduce incarceration and disparities without compromising community safety. In Broward County, most people who are accused of crimes are people of color or people with lower socioeconomic status. Their reasons for committing crimes could include lack of economic opportunities, lack of educational opportunities, mental health or drug addiction issues, or a combination of factors. When Pryor took office in 2021, he felt compelled to create programs offering opportunities in each of these areas. Diversion programs and specialized courts already existed for mental health and drug addiction, he said, but no programs aimed at addressing the lack of economic and educational opportunities. To address these issues despite a limited budget and limited opportunities beyond incarceration, Pryor reached out to community partners and organizations that had the resources and tools to offer the economic and educational opportunities people were missing.

The first program created, said Pryor, was in partnership with an organization that aimed to train and employ people coming out of the criminal justice system. Despite receiving $2 million from the Department of Labor, the organization struggled to identify individuals eligible to receive the services. Pryor and the organization’s chief executive officer created a program called Economic Empowerment Today, in which people accused of committing nonviolent felony offenses can receive a certification and job-finding assistance.9 Upon program completion, an individual’s offense is downgraded to a nonfelony or dismissed entirely. This program, said Pryor, allows people to leave the criminal justice system not as convicted felons, but as people with gainful employment and a sense of pride.

A similar program, the Court to College Program, was created for individuals hoping to pursue educational opportunities.10 Through this program, individuals who commit nonviolent offenses can earn a GED, obtain an associate’s degree, and/or become certified or licensed for a skilled job. Program completion leads to downgrading or dismissal of the case. Again, said Pryor, participants can leave the criminal justice system with advanced education and improved employment opportunities. These programs are also available to victims of crimes, who in general, may be at risk of future criminal justice system involvement, said Pryor.

___________________

9 For more information, see https://browardsao.com/diversion-programs/

10 For more information, see https://browardsao.com/diversion-programs/

Another new program, said Pryor, is directed at cases in which children have been accused of domestic violence. The program serves everyone impacted by the incident, including the child, parents, and others in the home. Community members help develop an “Integrated Family Safety Plan” that offers services and support to the entire family; this could include support for mental health, drug addiction, or lack of economic or educational opportunities. Recidivism rates among youth who completed this program decreased substantially, said Pryor, and families received the support they need.

“This is how we are trying to reimagine the criminal justice system,” said Pryor, by holistically examining the multiple, intertwined issues that lead to crime and finding solutions to those issues. While the criminal justice system itself is not equipped to solve every problem, he said, partnering with other stakeholders can make it possible to address people’s needs and reverse the cycle of crime.

Prosecutor Perspective: Ramsey County

John Choi, County Attorney for Ramsey, Minnesota, explained his unintentional entry into the prosecution field. In his previous job as City Attorney, he prosecuted lower-level misdemeanor and gross misdemeanor adult crimes. New to the position, Choi said that he gravitated toward the prosecution function of the job in attempt to better understand the position. His lack of prior experience in prosecution was beneficial, he said, as it allowed him to more easily see issues in the system, such as a lack of data-driven practices and the pursuit of outcomes that were not in the public’s interest. In this role, Choi used data and created diversion programs; he was elected as County Attorney in 2010. Historically, the criminal justice system has suffered from a lack of critical thought about its intended function, and a lack of research on the impacts of its practices, said Choi.

The biggest challenge in prosecution is thinking beyond the current adversarial system, said Choi. Less than two percent of cases go to a jury trial while the rest, he said, are addressed through a plea-bargaining process that is “like an assembly line”—it processes people toward a form of conviction, which often leads to further involvement with the criminal legal system. In 2019, in attempt to think outside of the adversarial system, Choi and his colleagues implemented

a program called (Re)Imagining Justice for Youth.11 This program aims to find community-based solutions, particularly within those communities most impacted by crime and the criminal legal system. A leadership team was created to “unpack” the adversarial system and to consider ways to make prosecution more collaborative. For example, in the traditional system, the prosecutor often makes charging decisions based solely on information from police, rather than gathering additional information that could help them better understand the human context and individual needs in specific cases, he said. In place of the traditional model in which the prosecutor is the sole decision maker, the program’s leadership team developed a collaborative model, with a multidisciplinary review team to make case decisions. This collaborative review team includes the prosecutor, the public defender, and the community. To decide whether to offer the community-based accountability alternative, the collaborative review team first engages with the youth’s family to learn more about their situation and the reasons for their involvement with the criminal justice system. The team decides among four potential options. First, a case can be returned to the family, along with support and resources to help them resolve it. Second, a case can be referred to a community-based accountability program, in which community providers use a restorative justice model. Third, a petition can be filed asking for a judge’s involvement but asking that the judge allow the community to help resolve the case. Finally, the case can be filed in the traditional youth justice court system.

When this program was launched, said Choi, it experienced pushback from prosecutors, because asking prosecutors to share decision-making power represented a fundamental change in thinking. However, said Choi, this informed decision-making model has erased racial disparities in success rates for alternative programs, such as the new community-based accountability approach, compared to prior diversion programs the office utilized.

PERSPECTIVES ON IMPLEMENTATION FROM RESEARCHER-PRACTITIONER PARTNERSHIPS

Carrie Pettus shared her work at Wellbeing & Equity Innovations, a national nonprofit translational research firm that seeks to impact the criminal justice field by bridging practice and research. Pettus focused her remarks on efforts to research the effectiveness of trauma-

___________________

11 For more information, see https://www.ramseycounty.us/your-government/leadership/county-attorneys-office/reimagining-justice-youth

responsive diversion programming. One project, based in Indianapolis, is a randomized controlled trial of a trauma-responsive diversion program that specifically serves individuals who were victims of nonfatal shooting incidents and who, within a year, became defendants. The goal of this project is to prevent future victimization and future offending by treating and intervening in trauma, which has been empirically shown to be related to future threats to both the individual and the public.12 This program, said Pettus, “challenges our notion of who are victims and defendants in our communities.” The second project, based in New Jersey, has a similar focus on violence prevention and retaliation prevention, using a trauma-responsive diversion approach.13 This program is currently undergoing feasibility and acceptability testing. Key implementation components for both programs included engagement with community members, community partners, stakeholders within the prosecutor’s office, and neighborhood associations and advocacy groups, said Pettus. Building significant stakeholder support stabilizes these types of programs, she stated.

Mona Sahaf introduced herself as the director of the Reshaping Prosecution Initiative at the Vera Institute of Justice, a large criminal justice nonprofit. Prior to her current role, Sahaf served as a prosecutor at the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia and the Department of Justice (DOJ) in the Human Rights & Special Prosecution Section. As part of her job at DOJ, she traveled the country and observed how prosecutors charge, how defense attorneys operate, and how judges’ sentencing varies depending on region. This perspective informs her work at Vera, Sahaf noted. Sahaf’s team consists of former trial attorneys, public defenders, and prosecutors, as well as qualitative and quantitative researchers, community organizers, and teachers. The initiative focuses primarily on building diversion programs. In their current model, a DA’s office and a community-based organization apply jointly to work with the Vera Institute of Justice; an existing relationship between the two, as well as community support, are required. Approved applicants receive technical assistance and guidance for building programs with a race equity lens. The Vera Institute of Justice aims to work with community-based organizations that are “Black, Brown, or system-impacted-led, or deeply embedded in these communities,” she said, noting that the program includes sustainability efforts. Building an

___________________

12 For more information see https://wellbeingandequity.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/INDY-TID-One-pager.pdf

13 For information see https://wellbeingandequity.org/wpcontent/uploads/2024/09/APPO_About_WEI_vf_121123.pdf

effective program takes more than a year, said Sahaf, and Vera Institute cannot “parachute into jurisdictions” and then leave. In exchange for Vera Institute’s assistance with program implementation, the partners agree to share data to evaluate the program’s impact.

Based on her experience at Vera, Sahaf shared three reflections about the current state of prosecution. First, interest in implementing changes, particularly related to diversion, is incredibly high in diverse communities all over the country. Second, the prosecution field has an ongoing need to measure program outcomes. Data collection continues to be a big challenge, and many actors are hesitant to share data. Data are essential to this work, she said, because well-communicated evidence is necessary to inform the public’s understanding of how to achieve public safety. Finally, racial disparities exist in the criminal justice system due to multiple intersectional issues with long historical legacies. While prosecutors and others can take steps to reduce these disparities, additional frameworks and resources are needed to fully address root causes, she said.

IMPLEMENTATION CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Biener noted that workshop speakers highlighted several challenges to implementing prosecutorial programs that see to reduce racial disparities or provide alternatives to incarceration, such as limited resources, budgetary constraints, and the need for greater buy-in. Speakers also identified solutions to these challenges, such as partnering with external stakeholders who can provide the necessary resources.

One major contributor to success, said Pettus, involves the prosecutor’s office trusting community partners and family systems with responsibilities, rather than trying to manage programs by themselves. The two biggest challenges for prosecutors are finding partners who deliver evidence-based services and working to cultivate a culture of trust with those partners and the community, Pettus said. Another important success factor involves acknowledging that contact with the criminal legal system impacts not only the accused person but also their family. Focusing on the family system is critical, Pryor noted. When his own family members were victimized, they did not get the level of care that others would have received because they were Black and poor, said Pryor—which explains why marginalized communities often lack trust in the criminal justice system. Pryor said, “Every day, my job is to…work towards rebuilding or gaining trust with our community.”

Pettus and Pryor also discussed the role of trust between prosecutors and researchers. It is the responsibility of researchers, said Pettus, to earn that trust by acknowledging the daily realities of prosecutorial practice, and by communicating and contextualizing their learnings in ways that are useful for prosecutors. Partnering with research organizations requires trust from prosecutors, Pryor said, particularly in terms of trusting that data will be treated with integrity. When Pryor’s office partnered with the Prosecutorial Performance Indicator (PPI) project,14 some staff worried that shared information would be used to punish them if they took certain actions. Pryor said that sharing information with PPI is a way for the office to hold itself collectively accountable. Sharing allows the office to look at their data honestly and to make changes in response to that data, to ensure a more fair, just, and equitable criminal justice system. Further, said Pryor, the data dashboards created for the public allow communities to view information in real time and to hold the office accountable; being open and transparent contributes to earning the community’s trust.

Reducing Racial and Ethnic Disparities

Diversion programs and other alternatives to incarceration are often designed with the intention of reducing racial and ethnic disparities, said Biener. However, while these alternatives may reduce overall incarceration numbers, racial and ethnic disparities are sometimes maintained or even exacerbated. Biener asked panelists to comment on implementing programs that are effective for public safety and also effective at reducing racial disparities.