Advancing Child and Youth Health Care System Transformation: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (2025)

Chapter: Advancing Child and Youth Health Care System Transformation: Proceedings of a Workshop-in Brief

Convened October 15, 2024

Advancing Child and Youth Health Care System Transformation

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

INTRODUCTION

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s (National Academies’) Forum for Children’s Well-Being1 hosted an implementation summit titled “Advancing Child and Youth Health System Transformation.” This event convened a broad range of leaders to support the implementation of recommendations from the National Academies consensus study report Launching Lifelong Health by Improving Health Care for Children, Youth, and Families (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2024). The report responds to worsening child health2 outcomes in the United States—including increases in chronic conditions, mental health crises, and health inequities—and offers a roadmap to address these urgent challenges.

Report co-chairs Tina Cheng (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and the University of Cincinnati) and James Perrin (MassGeneral Hospital for Children and Harvard University) both noted the United States child health crisis threatens national prosperity and national security, making the U.S. workforce less prepared for the needs of business and industry and diminishing military preparedness. As an example, Cheng noted that three branches of the military did not meet their recruitment goals in 2023 due to health-based ineligibility of youth (Council for a Strong America, 2022, 2023a,b).

Cheng and Perrin presented an overview of the consensus report’s recommendations, grounded in four guiding principles: (a) adopting a life course perspective recognizing that child health forms the foundation for adult and intergenerational health, (b) focusing on positive outcomes for all children and youth, (c) uplifting family and community partnerships, and (d) attending to sustainability. Building on this framework, the report identifies five goals, each paired with a series of recommendations. These goals aim to (a) elevate national focus on child and youth health; (b) reform health care financing to prioritize prevention and health promotion; (c) strengthen community-level prevention efforts; (d) co-create systems with youth, families, and communities; and (e) implement strong measurement and accountability mechanisms. These goals collectively seek to reshape the U.S. health care system to better serve all children, youth, and families, addressing current shortcomings and leveraging evidence-based innovations to

__________________

1 The Forum brings together a range of experts from various fields to create a collaborative ecosystem that addresses challenges in child wellbeing, implementation science, and policymaking. Its unique structure allows for long-term relationship building across sectors, facilitating rapid responses to pressing issues and driving effective, sustainable change in child-related policies and programs.

2 The report defines health as the ability to reach one’s potential, meet needs, and interact effectively with one’s environment across biological, physical, and social domains. This definition goes beyond the absence of disease and emphasizes holistic wellbeing, potential, and functioning in context.

![]()

improve child health outcomes. To find a brief summary of the report’s goals and recommendations see the Report Highlights.3

Following the introductory remarks, invited speakers engaged in two moderated dialogues—one reflecting on the report’s vision and recommendations, and the other highlighting innovative models for advancing healthcare for children, youth, and families. Each dialogue was followed by sessions where attendees collaborated to identify opportunities for scaling efforts, driving policy change, and fostering cross-sector partnerships to advance the report’s goals.

LOOKING FORWARD: CONTEXTUALIZING REPORT VISION, OPPORTUNITIES, AND CHALLENGES

The first panel considered the opportunities and challenges presented in the Launching Lifelong Health report. Moderated by Forum co-chair Leslie Walker-Harding (University of Washington, Seattle Children’s Hospital), panelists included Elizabeth Ford (BFT Consulting), Asli McCullers (Doctoral Student, Community Health Awareness, Messages, and Prevention Lab), Kyu Rhee (National Association of Community Health Centers), Michael Warren (Maternal and Child Health Bureau), and Charlene Wong (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]). Speakers were tasked with reflecting on and responding to the report’s vision and recommendations, considering key next steps, and identifying essential actors, policies, and programmatic changes required to implement the vision of the report.

Mindset and Messaging

Ford spoke to the mindset shift needed to support investment in child well-being. She reminded the audience that child well-being impacts everyone because of its critical role in shaping our workforce, our economic security and our national security. Warren suggested that adopting a life course perspective reveals the profound impact of investing in children, noting that this approach highlights how early childhood investments are deeply intertwined with the health and wellbeing of future generations. With a life course view, he explained, it becomes clear that investing in children contributes significantly to long-term solutions for critical health issues, including maternal mortality and pre-term birth.

Rhee highlighted a historical focus on elder care over child health. He called for shifting resources from treatment to prevention and advocated for “going beyond the exam room” to both think about the social factors affecting health and to engage in prevention outside of healthcare settings. Warren drew attention to the need to fundamentally change the way healthcare professionals are trained, to better address the non-medical factors shaping health outcomes.

Financial Incentives and Return on Investment

Ford, Rhee, Warren, and Wong amplified the report’s conclusion that the current structuring of health financing does not reward prevention and health promotion. “Prevention isn’t new” Warren explained, it’s just not incentivized in our existing systems. Ford elaborated on the importance of demonstrating long-term return on investment (ROI) for child health initiatives to secure financial support, while also underscoring the challenge of balancing immediate treatment needs with prevention efforts. Rhee called on decisionmakers to challenge the current healthcare system’s focus on ROI and instead prioritize values-based investment in prevention and primary care. He argued that allocating just 5% of healthcare spending to comprehensive primary care through community health centers could significantly improve healthcare access and ensure fairer and more just opportunities for people to achieve their optimal health—a concept referred to in the field as “health equity” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024). Warren noted shifting to prevention may initially raise costs, as treatment remains necessary until prevention efforts reduce demand for high-cost services.

Considering the economic case for investing in child well-being, Ford explained that demonstrating a return on investment would involve quantifying the cost savings and societal benefits of preventive care, which can be difficult given the long-term nature of investments in children. Warren and Rhee noted the importance of aligning payment structures to measure how social conditions impact health outcomes. Wong identified a critical need for additional financing and resources to address workforce shortages and infrastructure gaps, explaining that

__________________

3 https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/27835/Healthcare_Report_Highlights.pdf

![]()

without adequate funding for core capabilities such as workforce development and data infrastructure, implementing the report’s proposed vision and improvements in areas like early care, education, and public health becomes extremely challenging.

Cross-Sector Collaboration and Integration

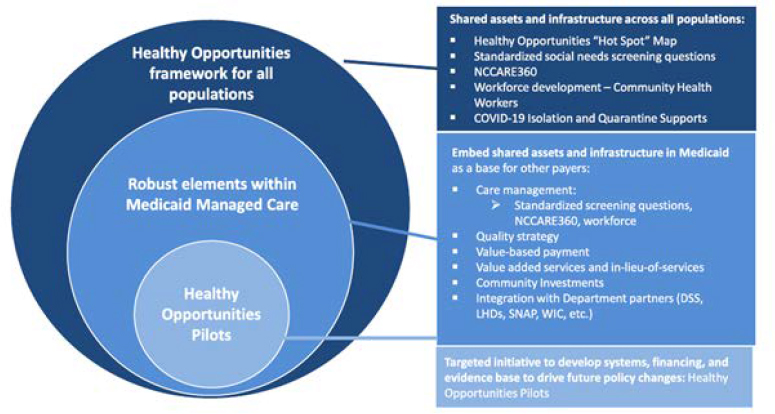

Wong reinforced the report’s emphasis on cross-sector collaboration, stating that “protecting health is a team sport.” She and Ford highlighted the need for alignment across healthcare, public health, education, and agriculture, including data sharing. Wong cited North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilot, where the state integrated WIC and SNAP with child health services to promote whole-child and whole-family health. This Pilot also linked enrollment data across Medicaid, SNAP, and WIC to enable targeted enrollment outreach. Wong emphasized the need for shared investments across sectors, noting that proven strategies exist but require scaling. Warren echoed the call for breaking down funding silos and pointed to federal-state collaborations like the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation’s early-childhood initiative and a Health Resources and Services Administration, CDC, and Department of Education partnership on newborn screening.

Rhee underscored community health centers’ role in prevention, serving one in eight U.S. children across 16,000 sites, including school-based clinics. He called for increased financial support for these critical early intervention spaces. Wong called for optimizing use of existing CDC data to improve reporting consistency and cut data collection costs. Meanwhile, Ford highlighted the necessity for financial flexibility when additional funding is unavailable, advocating for more strategic allocation and management of existing funds to maximize impact and efficiency.

Youth and Community Co-Design

Highlighting the value of youth and community co-design, McCullers explained that her work at MedStar Health involved engaging families through a range of tools from focus groups and interviews to more in-depth engagement on family advisory boards. She emphasized the importance of ongoing engagement with youth and families throughout program design and implementation, and suggested focus groups, interviews, and family advisory boards as models that could facilitate this engagement. McCullers noted that “the efforts we work together on now [will be the programs that youth] inherit and benefit from long term”.

Ford noted that she had encountered examples of community engagement significantly improving program success, including in housing and food programs. Warren echoed this comment and noted the importance of not only engaging lived experiences but compensating partners appropriately, “just like we would other consultants.” He pointed to engagement efforts within the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, including the Healthy Start Program which has recently introduced Community Consortia.4 Rhee noted that community health centers provide a useful model for co-design, highlighting their long-standing practice of maintaining 51% patient governing boards.

TAKING ACTION: INNOVATIVE MODELS FOR ADVANCING HEALTHCARE FOR CHILDREN, YOUTH, AND FAMILIES

Kelly Kelleher (Nationwide Children’s Hospital and The Ohio State University) showcased successful real-world case study efforts each of which advance core elements of the Launching Lifelong Health report goals. Participants Daniel Hartman (Southcentral Foundation’s [SCF’s] Nuka System of Care), Rose Green (The Colorado Health Foundation [The Foundation]), and Maria Perez (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services [NC DHHS]) discussed key strategies for implementing, scaling, and sustaining programs and models of care. Case study strategies are summarized below in Box 1.

The Colorado Health Foundation (The Foundation)—Leveraging Community Engagement and Youth Partnerships

Green outlined the youth-focused work of The Foundation, a statewide philanthropic organization that works to advance the overall health and well-being of every Coloradan. The Foundation emphasizes equal opportunity for health for all and works closely with Coloradans with less power, privilege and income, and Coloradans of color. Green began her presentation by noting that The Foundation does not have a single cornerstone child/youth health program but instead, works to promote youth health through multiple community-specific local

__________________

4 Every Healthy Start program has a Community Consortium, a group of people invested in achieving the shared goal of creating an environment that supports maternal, infant, and family health and well-being (Health Resources and Services Administration, n.d.).

![]()

BOX 1

Summary of Case Study Strategies

The Foundation engages youth and communities in shaping cross-sector health initiatives to ensure fairer and more just opportunities for people to achieve their optimal health. Instead of a single statewide program, The Foundation tailors solutions to local needs, emphasizing youth leadership, community co-design, and integrated services.

Key Strategies:

- Protective Factors Approach: Builds trusted relationships, safe spaces, and youth agency.

- Participatory Design and Evaluation: Youth advisory mechanisms shape policies.

- Embedded Program Officers: Officers spend 40% of their time in communities.

- Health & Social Service Integration: Hospitals, schools, and community groups collaborate on care delivery.

Notable Impact: The Foundation integrates lived experience with evidence-based best practices, ensuring community-led solutions while strengthening social supports outside traditional medical settings.

The SCF Nuka System of Care operates a customer-owned tribal health system in Alaska, serving 65,000 Alaska Native and American Indian people. Its relationship-based, team-centered model prioritizes cultural values, trust, self-determination, and integrated care.

Key Strategies:

- Customer-Ownership Model: Governance by Alaska Native leadership ensures alignment with cultural values and community needs.

- Team-Based Primary Care: Include doctors, case managers, behaviorists, social workers.

- Relational Approach: Emphasizes extended provider-patient interaction to foster trust.

- Alternative Care Delivery Models: Same-day visits, virtual care, and group appointments increase access.

Notable Impact: SCF’s model reduces emergency and inpatient costs while improving health outcomes and patient experience. Continuous evaluation guides refinements.

North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots (NC HOP) use Medicaid funding to address social drivers of health, demonstrating a scalable model for integrating food, housing, transportation, and interpersonal violence prevention into healthcare.

Key Strategies:

- Medicaid 1115 Waiver: Uses Medicaid funding to test non-clinical health interventions.

- Standardized Screening & Referral: Social determinants screening and a closed-loop referral platform streamline care coordination.

- Statewide Network Coordination: 160+ community-based organizations collaborate under regional hubs.

- Capacity Building: $100M allocated for training and infrastructure development.

Notable Impact: Early evaluation shows reduced unmet social needs, lower healthcare utilization, and cost savings. North Carolina is now scaling the program statewide.

SOURCE: Rapporteur-generated based on the presentations of Rose Green, Dan Hartman, and Maria Perez.

![]()

programs. She explained, “solutions are specific to the communities we’re working in [...] and that makes it impossible to have one solution that fits all.” The Foundation’s aim in its “Thriving Youth People” focus area, she explained, is for young people in Colorado to be able to thrive both mentally and physically. Thriving, Green noted, “means that they are able to work toward the vision that they have for their lives, that they can dream into their future and feel like it is possible for them to get there.”

A key element of their youth-based work, Green explained, is the adoption of a robust protective factors framework. This involves focusing attention on building trusted relationships with adults, safe and welcoming environments, and the ability of young people to express agency—all with an understanding of the unique protective factors that exist in different cultures and communities. In response to the perspective of youth and community partners, The Foundation has made their youth work more holistic, combining previously divided mental and physical health portfolios, and combining work that was previously divided by age to instead serve youth across the age continuum from birth through early adulthood.

Youth and Community Engagement

Speaking to the Foundation’s attention to youth agency, Green described how The Foundation engages youth in shaping programs and policies that affect them. She explained that included establishing youth advisory mechanisms, developing youth-adult partnership models, and creating opportunities to engage youth for input in program design and evaluation. As an example, Green described work creating partnerships between hospitals, universities, and youth to give young people more decision-making power in their care. Doing this work successfully required a range of resources including thoughtful youth engagement strategies, training for adult partners, and compensation for youth participants.

Green also detailed the ways The Foundation operationalizes its commitment to community partnership. First, each program officer is assigned a regional focus area and is expected to spend around 40% of their time out in community, in addition to bringing communities into The Foundation. Program officers engage in active knowledge sharing and take a participatory approach to learning, engaging in focus groups, interviews, town halls, and conducting holistic local needs assessments. Their program evaluation also involves participatory and collaborative elements, centers lived experience, and considers systemic context. Green noted that as part of this work The Foundation developed an equitable evaluation framework, trained staff in participatory methods, and established partnerships with community-based researchers to implement their evaluation strategy effectively.

In addition, The Foundation connects best practices with community voice, understanding “that lived experience is just as important as best practices.” Green noted that she often encounters resistance to this view but argued that assuming you have to choose between community voice and best practice is a mistake. “Community understands what works,” she explained, and called for leaders to marry best practices with what they’re hearing in communities. The Foundation’s efforts, Green explained, are not just to fund differently but to ensure that “power operates differently because we’re bringing community in.”

Recognizing that many young people from minoritized communities may distrust the healthcare system, Green emphasized that community-based organizations that are trusted by youth are vital connectors to health resources. Part of The Foundation’s work, she explained, was in strengthening community-based organizations and better enabling them to connect populations with the health system. Another part of their work was in ensuring that the health system is adequately serving minoritized communities. At the same time, Green emphasized, it is important to recognize that most of what impacts health happens outside of medical institutions, and to strengthen resources and trust in those health-adjacent spaces. As an example, she described The Foundation’s work with the Children’s Hospital of Colorado’s Resource Connect—a full floor of human services and social determinants of health services that can be accessed as part of primary care visits. Green noted that they also listen to the needs of health systems, who are facing challenges posted by financial and workforce crises. She highlighted the importance of providing resources to medical institutions to support community engagement and called for greater measurement of community programs to enable prioritizing their financing.

![]()

Southcentral Foundation’s (SCF’s) Nuka System of Care—Customer-Owners Replacing Medical Culture with Relationships

The SCF Nuka System of Care, a tribal health organization in Alaska, serves 65,000 people regionally and provides statewide pediatric, OBGYN, and maternal fetal medicine care. Hartman highlighted its unique approach: a customer-ownership model, family-centered, team-based care, and integrated child and adolescent programs.

The Customer-Ownership Model

SCF’s customer-ownership model ensures that Alaska Native and American Indian people own and govern their healthcare system, emphasizing shared responsibility and multi-generational wellness. Hartman pointed to the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 19755 as pivotal in allowing SCF to transition from federally managed care to a system led by the community. SCF’s governing board, composed entirely of customer-owners, sets priorities, while transparent financial systems and structured community input ensure fair allocation of resources.

The transition to a customer-ownership model necessitated the establishment of a robust governing framework and the development of mechanisms for customer input in decision-making processes. The governing board, composed entirely of customer-owners, determines the direction and priorities of the health system. The health system works to leverage the strengths of the Alaskan Native community to advance shared goals. To ensure efficient and fair resource allocation, Hartman explained that SCF implemented transparent financial reporting systems, created avenues for community input on resource distribution, and developed metrics to measure fairness in distribution. He explained that the customer-ownership model is operationalized, in part, through a three-day relational training provided to every employee at onboarding by the system CEO. The training prepares staff to “hear and share story, an important customer owner-expressed value in our system,” said Hartman. In day-to-day practice, a relational system means that customer owners have ample time to meet with their providers in primary care settings, and that time is held for sharing stories and fostering trust, which in turn contribute toward feelings of shared responsibility and commitment to family wellness.

Shifting from Provider-Centric to Integrated, Team-Based, Customer-Centric Care

Recognizing that health extends beyond medical care, SCF shifted to an integrated, team-based model with clearly defined roles, shared care plans, and continuous training. A concentric-circle team structure places the customer-owner at the center, surrounded by a core team (primary care provider, nurse case manager, medical assistant, and case management support), an extended team (behavioral health, dieticians, social workers, midwives, pharmacists, and others co-located for real time collaboration), and referral network (specialists in cardiology, optometry, surgery, and traditional healing, often available same-day). SCF also moved beyond physician-centric models, introducing group visits, virtual care, and flexible scheduling to enhance engagement beyond traditional office visits. This required building robust virtual care systems and protocols for managing diverse care settings.

SCF embeds pediatricians and case managers in all-ages primary care (1:1 ratio), ensuring services for children and adolescents in every major center. This life-course approach supports continuity across developmental stages. Broadly, the team-based strategy allows for more efficient resource utilization and has improved quality of care, Hartman explained.

Supporting Child and Adolescent Health

The Nuka System’s approach offers unique means of supporting child and adolescent health, Hartman explained. First, because children and adolescents are uniquely dependent on their families to shape their well-being, and SCF emphasizes family wellness and the integration of pediatric care into all ages care and child and adolescent dependence on the family. Hartman also highlighted the SCF’s emphasis on respecting and hearing the individual as promotive of child and youth health. For children and adolescents, Hartman explained, self-confidence and dignity are key determinants of health, and there is a pressing need to be seen and respected, and to feel trust in providers—needs that are served well by the system’s customer-owner model and relational approach to care.

Evaluation Metrics and Outcomes

SCF monitors performance rigorously, conducting 300 customer satisfaction surveys daily to refine care. Hart-

__________________

5 https://www.bia.gov/regional-offices/great-plains/self-determination

![]()

man encouraged decision-makers to trust that upfront investments in team-based care yield long-term benefits, including:

- 44% decrease in emergency room visits

- 64% increase in inpatient discharges

- Above 75th percentile on key Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Setquality measures

Hartman challenged decisionmakers to have faith that the upfront costs of team-based care pay off in the medium and long term in cost savings, as well as in significant improvements in health outcomes and patient experience.

North Carolina’s Health Opportunities Pilots (NC HOPs)—Utilizing Medicaid to Address Social Determinants of Health

Maria Perez (Associate Director of Healthy Opportunities at NC DHHS) presented on NC HOP, a Medicaid-funded initiative addressing social drivers of health to improve outcomes and reduce costs. The program prioritizes children, a significant portion of Medicaid enrollees, and aims to establish a sustainable financial model adaptable for both public and private payers.

Development, Implementation, and Infrastructure

North Carolina’s approach to closing health gaps began with identifying root causes of health disparities and selecting target areas for intervention. Drawing on frameworks from AHIP (2021) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the state adopted a whole-person health model to address non-clinical factors influencing health. As a key first step, NC HOP established a standardized social determinants of health screening tool, ensuring a common baseline for assessing needs across age groups and provider types. This tool powers a closed-loop referral platform, enabling providers to identify needs, refer patients, and track outcomes efficiently. Implementation also involved a network of over 160 community-based organizations coordinated by three network leads acting as care hubs. NC HOP also leveraged existing technology, enhancing NCCARE360, integrating eligibility, enrollment, service authorization, and invoicing into a single system. This ensures seamless reimbursement for community providers via a point-and-click invoice converted into a Medicaid claim.

NC HOP leverages a $650 million 1115 Medicaid transformation waiver to fund non-clinical interventions in food, housing, transportation, and interpersonal violence. The waiver funds 28 evidence-based, federally approved services (per NC DHHS’ Pilot fee schedule). Additionally, $100 million supports community organizations (e.g., shelters, food banks, legal aid) with technical assistance and Medicaid navigation. This investment includes technical assistance and training to help organizations navigate the Medicaid system’s complexities. As an example, Perez noted that these 160 organizations include shelters, food banks, and legal services organizations. Thirdly, the waiver funds establish infrastructure to bridge health and human service providers. Lastly, they support the evaluation of service impact and value for different populations. This structure is summarized in Figure 1 below. To assess its effectiveness, Perez said a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services- (CMS-) approved SMART design (randomized trial) will provide rapid-cycle feedback, culminating in a summative evaluation.

Evaluation and Expansion

Early evaluation of NC HOP has shown promising results. Perez reported that the Interim Evaluation Report demonstrated that receiving services through NC HOP has reduced social need, utilization, and total cost of care for the studied population. Based on these positive outcomes, North Carolina is seeking to expand the program. Perez outlined the state’s 1115 waiver renewal request, which aims to expand services statewide, scale and modify certain existing NC HOP services, and broaden eligibility criteria. This expansion would allow for the procurement of additional network leads and provide capacity-building funds for new regions.

As NC HOP transitions from pilot to long-term implementation, Perez emphasized the need to explore risk-based models and sustainable funding. She also highlighted several lessons learned from the implementation of the pilots. These include the importance of building trust with community-based organizations, the need for flexibility in program design, and the value of ongoing stakeholder engagement. Perez said that these insights are informing the state’s approach to scaling the program and could provide valuable guidance for other states considering similar initiatives.

![]()

a For additional details on this program, see https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/healthy-opportunitiesSOURCE: Maria Perez’s presentation.

TABLETOP DISCUSSIONS

The workshop included two tabletop discussions that included representatives of a range of roles including medical professionals, researchers, funders, federal, state, and local decision-makers, nonprofit leaders, and youth leaders. Participants were invited to reflect on how they and others could advance the report’s vision through their roles, collaborations, and policy or programmatic change; to share promising models and key learnings; and to consider what further dialogue, partnerships, and supports—especially for meaningful youth engagement—could help move the work forward. Below, Box 2 highlights some promising initiatives identified by meeting participants as advancing report goals.

BOX 2

Some Potential Models, Emerging Polices, and Promising Programs

Prevention & Health Promotion

- TRAILS (Transforming Research into Action to Improve the Lives of Students)a trains and equips school professionals to use evidence-based practices at the prevention, intervention, and crisis management levels.

- Nemours Children’s Reading BrightStart!b provides research-based resources and services to strengthen early literacy, recognizing reading ability as a key determinant of lifelong health.

- Well Visit Plannerc allows families to complete pre-visit planning, generating a personalized guide for both the family and care team, aligned with Bright Futures Guidelines.

- Engagement in Action Frameworkd provides a roadmap for states to integrate early childhood health systems with a focus on family engagement and whole-child health promotion.

- Prescription for Playe distributes DUPLO kits and educational materials to parents at well-child visits, reinforcing early childhood development through play-based learning.

- Cycle of Engagement Model promotes data-driven partnerships among families, healthcare providers, health plans, and communities to foster children’s well-being.

![]()

- Family-Centered Medical Home Model is an evidence-based approach that ensures comprehensive, coordinated, and accessible care for children and families, supported by a team-based care structure.

Youth & Family Partnership

- Youth Leadership Councilf (New York City Administration for Children’s Services) provides a platform for young people in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems to engage in policy development.

- Maryland Youth Advisory Council enables Maryland youth to participate in legislative processes and recommend policy changes.

- YouthLineg is a free, 24-hour peer-to-peer mental health crisis and support service, staffed by trained teens and young adults.

- Youth Mental Health Corpsh deploys young mental health navigators in schools and communities, providing career pathways in behavioral health while expanding mental health services.

- Fathers for Familiesi (Corner Health Center) strengthens father-child relationships through individual and group support services that promote engaged parenting.

- Nurture Connections Fatherhood Interest Group is part of a national movement to foster nurturing early relationships, with a focus on fathers.

- Vital Village Networkj is a coalition of community organizations and residents working to address social determinants of health and improve child and family well-being.

- Family Voices partners with families of children and youth with special health care needs to improve health care systems and ensure family-centered care.

- Nurse-Family Partnership Strengths and Risks Frameworkk helps home-visiting nurses assess client strengths and risks to provide tailored support to families.

- Specialized Alternative to Sentencing Supportl offers young caregivers (ages 12–25) charged with nonviolent offenses individualized, holistic health services, with the opportunity to have their charges dismissed upon successful completion.

- Family-to-Family Health Information Centers are federally funded organizations that provide free support, information, and resources to families of children with special health care needs or disabilities to help them navigate health care and related services.

Healthcare Policy & Systemic Change

- Subspecialty Teleconsultation Models—including electronic consultations and live telemedicine—improve access to team-based pediatric subspecialty care, reducing barriers to expert medical support.

- Pediatric Practice of the Future (Boston Medical Center) integrates physical and behavioral healthcare for families while empowering them to shape their own care priorities.

![]()

- CMS Transforming Maternal Health Model enhances maternal healthcare by expanding access to midwifery and doula services and reducing adverse outcomes.

- States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Developmentm is a CMS initiative that incentivizes states to control healthcare costs while promoting equitable access to care.

- Accelerating Child Health Transformation Initiativen (Center for Health Care Strategies) builds family-provider partnerships and integrates social determinants of health into child healthcare.

- Framework for Aligning State Agencies to Support Better Health and Well-Being in Early Childhoodo provides a strategic roadmap for aligning Medicaid and early childhood systems to improve services for young children and families.

Children’s Hospitals’ Initiatives

- Children’s National Hospitalp operates programs addressing social determinants of health, improving child health outcomes, and promoting health equity.

- Cincinnati Children’s Hospitalq runs multiple initiatives, including the Michael Fisher Health Equity Center, the Health Equity Network, and the Population Health Research & Innovation Program, all aimed at improving access to pediatric healthcare.

- Nationwide Children’s Hospital leads efforts in prevention and school-based health, developing regional school health models and expanding value-based care initiatives to improve child health at a systemic level.

- Seattle Children’s Hospital advances child health through initiatives such as the Health Coalition for Children and Youth, Uncompensated Care programs, and the PedAL Initiative, which addresses pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome.

a https://trailstowellness.org/

b https://www.nemours.org/reading-brightstart-about.html

c https://www.wellvisitplanner.org/

d https://earlychildhoodimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/EnAct-Framework-Overview-8.31.23.pdf

e https://www.weitzmaninstitute.org/prescription-for-play/

f https://www.nyc.gov/site/acs/youth/youthleadershipcouncil.page

g https://www.theyouthline.org/about/

h https://www.youthmentalhealthcorps.org/

i https://cornerhealth.org/services/fathersforfamily/

j https://www.vitalvillage.org/about

k https://www.hscmd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/6.-NFP-and-Social-Determinants-2019.pdf

l https://www.washtenaw.org/3855/SASS-Caregiver-Diversion

m https://apply07.grants.gov/apply/opportunities/instructions/PKG00283811-instructions.pdf

n https://www.chcs.org/project/accelerating-child-health-transformation/

o https://www.chcs.org/media/AECM-Alignment-Framework-Brief_041624.pdf

p https://www.childrensnational.org/in-the-community/child-health-advocacy-institute and https://mentalhealth.networkofcare.org/washington-dc/services/agency?pid=ChildrensNationalMedicalCenterMobileHealthVan_2_1347_1

q https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/about/fisher-center and https://scienceblog.cincinnatichildrens.org/introducing-the-4ps-of-population-health-and-health-equity-research/

![]()

NEXT STEPS

Many summit attendees and speakers emphasized the benefit of cross-sector collaboration, prevention, innovative financing, data integration, and community engagement as essential to building a sustainable child and youth healthcare system that promotes fair and equal opportunity to achieve optimal health outcomes for all children. Several speakers also discussed possible next steps, including piloting and scaling effective youth health care models, and called for predictable, sustainable public funding to support these efforts; and additional engagement in future convenings by involving direct care providers, educators, parents, youth, and recipients of public services.

References

AHIP. (2021, April 15). The impact of social determinants of health on health equity and their root causes. https://www.ahip.org/resources/the-impact-of-social-determinants-of-health-on-health-equity-and-their-root-causes

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). What is health equity? https://www.cdc.gov/health-equity/what-is/index.html#:~:text=Health%20equity%20is%20the%20state,their%20highest%20level%20of%20health.

Council for a Strong America. (2022, October 14). Mission: Readiness members meet with Rep. Wenstrup to discuss new ineligibility data. https://www.strongnation.org/articles/2014-mission-readiness-members-meet-with-rep-wenstrup-to-discussnew-ineligibility-data

———. (2023a, January 24). 77 percent of American youth can’t qualify for military service [Factsheet]. https://www.strongnation.org/articles/2006-77-percent-of-american-youth-can-t-qualifyfor-military-service

———. (2023b, December 11). Mission readiness, we need . . . all that they can be. https://www.strongnation.org/articles/2288-we-need-all-that-they-can-be

Health Resources and Services Administration. (n.d.). Healthy Start. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs-impact/healthy-start

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2024). Launching lifelong health by improving health care for children, youth, and families. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27835

![]()

DISCLAIMER This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Abigail Allen as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. The statements made are those of the rapporteur or individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants; the committee; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

REVIEWERS To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Elizabeth Koschmann, Asli McCullers, and Allysa Ware. Kirsten Sampson Snyder, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

COMMITTEE David W. Willis, Georgetown University Thrive Center for Children, Families and Communities; Leslie R. Walker-Harding, The University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Hospital; Tina L. Cheng, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; April Joy Damian, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Kyle R. McDonald, Alliance for a Healthier Generation; Allysa Ware, Family Voices.

SPONSORS This activity was supported by contracts between the National Academy of Sciences and the American Board of Pediatrics (18452-81001), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (75D30121D11240), the Health Resources and Services Administration and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (75R60221D00002/75R60222F34004), the Health Resources and Services Administration (75R60221D00002/75R60223F340007), the Robert Wood Foundation (79272), and The David and Lucile Packard Foundation (2022-73646). Additional support came from the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, American Academy of Pediatrics, Academic Pediatric Association, American Psychological Association, Children’s Hospital Association, Family Voices, Global Alliance for Behavioral Health and Social Justice, Silicon Valley Community Foundation, Society for Child and Family Policy and Practice, and the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/advancing-child-and-youth-health-care-system-transformation-a-workshop

SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2025. Advancing Child and Youth Health Care System Transformation: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/29082.

|

Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education Copyright 2025 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. |

|