Fulfilling the Public Mission of the Land-Grant System: Building Platforms for Collaboration and Impact (2025)

Chapter: 4 Becoming an Engaged Institution: The Path Toward Institutional Readiness

4

Becoming an Engaged Institution: The Path Toward Institutional Readiness

The path from an institution with engagement programs to a truly engaged institution—in which engagement is embedded in and central to institutional culture and systems—is context dependent and will look different at each institution. Institutional cultures, norms, histories, and practices heavily influence any transformational process. In many cases, existing organizational structures disincentivize or create barriers to collaboration and engagement; these barriers will need to be removed to enable progress. Even at institutions with a strong history of and commitment to engagement, the terms used and the approaches employed may vary from discipline to discipline or unit to unit.

INNOVATING FOR COLLABORATION

The responsibility for fulfilling a university’s land-grant mission is often relegated to only a subset of units, creating silos and potentially constraining the scope and scale of these efforts. A recent activity by the National Academies of Sciences, Medicine, and Engineering (NASEM, 2025b) provided further perspectives on these issues. Workshop participants shared innovative solutions for encouraging engagement among practitioners and presented insights on how different sectors can contribute to advancing engaged research.

Assessing an institution’s readiness for collaboration and innovation will help to determine priorities and inform what commitments are appropriate at various stages of an institution’s engagement journey. Prospective external partners—especially those in industry—need an indication that partnering with an institution is likely to yield benefits that will help to advance their mission.

Innovation can take different forms; broadly, innovation refers to approaches that differ from what has been done in the past to generate better outcomes. Thus, approaches to projects and partnerships can be innovative regardless of whether they involve technical innovations, and the nature of this innovativeness can be shaped by the context of the institution and collaboration. It is also important to recognize that prospective partners may have a wide array of options to consider in identifying fruitful collaborations. The onus is on land-grant universities to define and demonstrate the unique value they can offer relative to other types of research organizations and institutions of higher education, in addition to demonstrating that they are prepared to be a good partner.

Conclusion 4-1: The institutional mindset and capacity to undertake meaningful long-term engagement that supports impactful collaboration depends on institutional transformation intentionally built across the university in relation to its multiple roles, tying the institutional mission to public values, and requiring transformation in culture and

practice. Such a transformation has occurred in some institutions, enabled by the commitment of university leaders who put into place the supports necessary to allow partnerships to flourish.

INSTITUTIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE AND SUPPORTS

Institutional infrastructure and supports are key to transforming the land-grant system and important to foster collaborative partnerships on university campuses. This can take many forms: merit and promotion policies that recognize public scholarship and community engagement in research and teaching, fellowship programs that provide training in collaborative practice, research grants to cultivate the formation of university community partnerships, community relationship management systems to analyze and improve the interactions between university and community partners, and accessible curricula on the topic for students interested in civic leadership and public service. These and other institutional supports provide important mechanisms that enable individuals to adopt new practices and shift mindsets toward a culture of collaboration and institutional effectiveness in carrying out the public mission of the land-grant system.

Universities need practical strategies for building the infrastructure and supports for collaborative partnerships with nonprofit organizations, government agencies, industry, and local community groups. Institutional policies, funding mechanisms, cross-unit coordination, research administration, recognition programs, and communities of practice are some of the key areas of focus at the institutional level. Equally important are strategies that support individual faculty, researchers, and staff; curricula and programs that encourage high-impact practices through community-engaged learning for students; and recognition of community partners for their expertise and key role as co-producers of knowledge in the research and teaching mission of land-grant universities.

Institutional Infrastructure

For collaborative partnerships to be successful and sustained, universities need to develop coordinating infrastructure to support these partnerships. There is no one-size-fits-all solution; rather, this infrastructure should be responsive to each institution’s size, capacity, and priorities.

Modernizing Scholarship for the Public Good: An Action Framework for Public Research Universities, published by the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, is a timely resource aimed at supporting scholars and advancing public impact research, cooperative extension, and other forms of university community engagement (Aurbach et al., 2023). The Action Framework lays out eight areas for institutional strategic action:

- Develop committed institutional leaders

- Reform appointments, retention, tenure, and promotion practices

- Invest in institutional structures and networks

- Establish stronger reporting structures at the institutional level

- Build capacity for engagement and equity work among faculty

- Launch and maintain catalytic funding programs

- Develop awards and programs to recognize and celebrate work

- Formalize curricular training and professional development opportunities for students

The report provides examples of universities implementing these actions as well as a detailed database of strategic actions and tactics (Aurbach et al., 2023).1

Important to advancing institutional strategic action is the formation of a coordinating body to act as a “community engagement backbone.” This is one approach to strengthen an institution’s capability to convene, coordinate, and communicate the impact of collaborative partnerships. Some examples of the functions that can be performed by such a body include data gathering and assessment, facilitation of communities of practice, program administration to support professional development and grant funding, and services to identify university resources for community partners. As community engagement efforts mature and become embedded in institutional culture, the focus of such a body may shift from supporting the implementation of engagement projects and programs to facilitating coordination across and between campuses (Saltmarsh, 2016).

Turner and colleagues (2012) outlined six common activities of backbone organizations in the civic sector. Early in their life cycle, backbone entities primarily guide vision and strategy, and support aligned activities. As they gain experience and demonstrate collective impact, they often shift to “establishing shared measurement practices on behalf of their partners.” Mature backbone organizations will then expand their impact by “building public will, advancing policy, and mobilizing funding.” Infrastructure aimed at enabling research translation for entrepreneurs at the University of Georgia is one example of how a backbone organization can facilitate ecosystem transformation (see Box 4-1).

When applied to university settings, a community engagement backbone’s role is similar to that in the civic sector. According to John Saltmarsh (2016), Professor emeritus of higher education at the University of Massachusetts Boston, the function is to:

plan, manage, and support community engagement initiatives through ongoing facilitation, technology and communications support, data collection and reporting, and handling the myriad logistical and administrative details needed for the community engagement to function smoothly and to have the greatest impact. (p. xii)

For example, Cornell University’s Einhorn Center for Community Engagement2 was launched in 2021; it was built upon several decades of community engaged research and learning initiatives and infrastructure at Cornell, including a Public Service Center, Office of Engagement Initiatives, and a physical Engaged Cornell Hub where five public engagement units are based. Situated in the Office of the Provost and the Division of Student and Campus Life, the Einhorn Center develops and directs programs, workshops, and funding opportunities and supports a university-wide network for community engagement. It also collects data and performs assessments to measure the impact of projects and programs, and engages in fundraising and advocacy to sustain community engagement.

___________________

1 See https://airtable.com/appTKXGHSza4RHNJj/shraoZlcCgYrXCiki/tblxwg5K2tadXS5Hr (accessed July 11, 2025).

2 See https://einhorn.cornell.edu/ (access date July 11, 2025).

BOX 4-1

Building the Ecosystem: How the University of Georgia’s Innovation Infrastructure Drives Collaboration and Economic Impact

The University of Georgia (UGA) offers several examples illustrating the vital role of infrastructure—beyond funding—in advancing collaborations for mutual benefit within an innovation ecosystem.

One example is UGA’s Innovation Gateway,a which fosters startups and facilitates technology licensing to translate UGA research and innovation into the marketplace. With programming for UGA researchers, entrepreneurs, and investors, Innovation Gateway has been instrumental in the creation of over 200 companies, which have collectively introduced more than 1,200 new productsb to the marketplace and created over 1,300 jobs, for an estimated annual economic impact of $531 million from research-based startups. The program administers rounds of funding from the Georgia Research Alliance and helps entrepreneurs apply for Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer grants.

However, facilitating access to funding is only one part of a much broader suite of services and supports the Innovation Gateway provides. Entrepreneurs and their ventures benefit from expert assessments of their market potential, coaching on developing an effective pitch deck, access to an on-campus startup incubator facility, a 7-week Innovation Bootcamp, and meetings with strategic partners and potential investors. For intellectual property and licensing, services include evaluating patentability, technology marketing, managing compliance issues, and receiving and distributing license income, among others. This access to expertise, facilities, networks, and programming provides the infrastructure to support an effective and sustained ecosystem for moving the benefits of UGA research and innovation beyond the university system and into the community.

Other examples of enabling infrastructure are found across eight public service and outreach units of the University System of Georgia, cooperative extension programs serving every county in the state, and outreach and engagement programs within each of UGA’s 19 schools and colleges. In addition, UGA embeds public service into its appointment and promotion processes, including through the recognition of service within the main tenure-track faculty track as well as through a special stand-alone public service promotion track within the eight public service and outreach units and cooperative extension. Incentivizing and rewarding public service as part of an individual’s career progression and within the missions of university units can help to foster a culture of collaboration and help to sustain a healthy innovation ecosystem.

a See https://research.uga.edu/gateway/ (accessed August 14, 2025).

b See https://research.uga.edu/gateway/products-from-uga-research/ (accessed August 14, 2025).

Conclusion 4-2: Infrastructure such as a dedicated coordinating body that acts as a “community engagement backbone” can support collaborations by carrying out functional tasks that improve the ability of an institution to convene, coordinate, and communicate impacts. Over time, as the backbone matures, it can grow in influence and expertise, evolving to tackle more complex efforts such as “building public will, advancing policy, and mobilizing funding.” This illustrates the outcome of long-term institutional capacity building to facilitate deep connections to communities.

Institutional Support Strategies

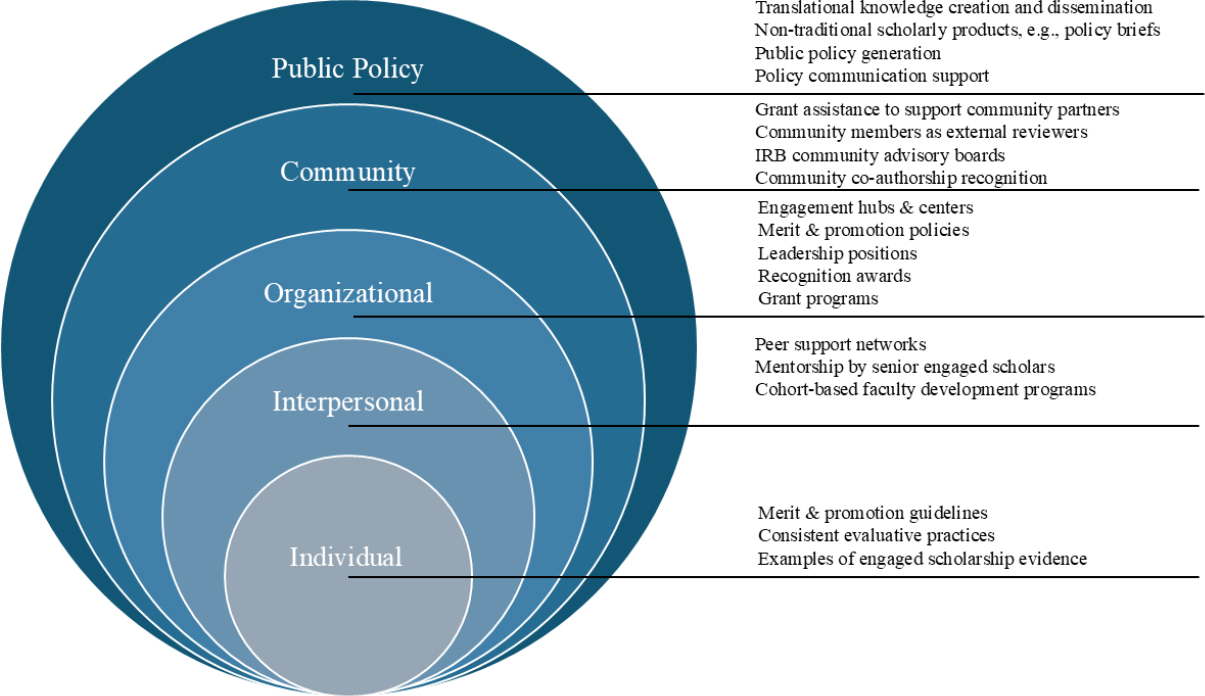

A variety of institutional supports can be instrumental in elevating collaborative partnerships. A multilevel approach can affect behavioral change with strategies targeting the

“individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy” (Rios and Saco, 2023, p. 36; see Figure 4-1).

SOURCE: Rios and Saco, 2025.

Examples of institutional strategies to support individuals can include providing merit and promotion guidelines for engaged scholarship or illustrations of engaged scholarship evidence.

At the interpersonal level, supportive relationships within departments, disciplines, and peer networks would help ensure that engaged scholars’ professional colleagues are aware of the value of their work; evaluate them effectively; and cultivate supportive spaces for professional development, interpersonal collaboration, and a sense of inclusion and belonging.

Although more common, organizational-level supports are also vital. As organizations, universities can center engaged scholarship and engagement initiatives as the core of their missions and identities. Rios and Saco (2023) found that “explicit merit and promotion policies signal to faculty that their work is supported by their institution, while also providing guidance to department chairs, faculty personnel committees, and others that review faculty dossiers” (p. 35).

Communities are the focus of much engaged scholarship work; however, institutions tend to provide little recognition or direct financial support at this level. Community partners as external reviewers, institutional review board community advisory boards, and community co-authorship recognition are several key strategies that recognize the value of community perspectives and the important role these partners play as co-producers of knowledge. Community partner compensation is also an area of unmet need; financial assistance can

have a direct impact, enhancing institutional reputation, building trust, and strengthening relationships between engaged scholars and their community partners.

Institutional support strategies that “mirror engaged scholar motivations to produce research responding to societal challenges and/or having public policy impacts” can go a long way for enlarging the community of engaged scholars, especially in the science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) fields (Rios and Saco, 2023, p. 35). Developing and rewarding faculty capacity to communicate effectively to policymakers, write policy briefs, and educate the public on policies that affect communities and sectors, would better align with engaged scholarship’s translational and dissemination practices for broader impact.

Examples of institutional support strategies are abundant and wide-ranging, but they can be grouped loosely into four areas: leading, incentivizing, enabling, and resourcing.

Having institutional leaders who are committed to public engagement is a crucial underpinning for all other support strategies. Leaders establish priorities, influence culture, and advocate for resources. Buy-in is needed across multiple levels of leadership, including top administrators and midlevel faculty and staff. Committed leadership is especially important for institutions whose past experience with public engagement is more limited, because these leaders will need to overcome existing barriers and drive change.

Incentives can take many forms. Embedding engagement into job roles and tenure and promotion reviews can help overcome systemic barriers that have historically led many academics to deprioritize engagement. At Purdue University, for example, changes in promotion and tenure policies led to increases in the number of faculty involved in engaged work and improved tenure success rates (Abel and Williams, 2019). Another incentive strategy is elevating effective engagement with awards and other forms of recognition, which has the dual effect of raising the visibility of engaged research and teaching, while promoting career advancement for those who do it well. For people as well as for projects and programs, reporting and assessment strategies can create incentives to improve effectiveness.

Many strategies fall into the category of enabling or capacity building. Examples include professional development; curricular development; practitioner networks; and various forms of physical, social, and digital infrastructure. The Public Engagement Project at the University of Massachusetts Amherst is a faculty-led initiative that fosters mentoring networks, community building, and learning opportunities to help faculty members across all career stages build public engagement skills (Aurbach et al., 2023).

Providing resources underpins many strategies and can take the form of funding and personnel. It is crucial to recognize that engagement requires time and resources and cannot be done sustainably if it is treated as “extra” or volunteer work. Resources are necessary to support projects and programs, institutional infrastructure, and the people who develop and implement them. Catalytic funding programs can also promote scholarly activity around specific priorities.

Conclusion 4-3: Institutional supports (monetary, recognition, promotion, and other measures) can be directed at multiple levels (individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, public policy). They are a signal that an institution values and rewards collaboration. Recognition and reward of community partners can build trust and enhance institutional reputation. Examples of supports are abundant and wide-ranging but can loosely be grouped into four main areas: leading, incentivizing, enabling, and resourcing.