Accelerating the Use of Pathogen Genomics and Metagenomics in Public Health: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 3 Applications in Early Warning and Preparedness

3

Applications in Early Warning and Preparedness

The second session of the workshop featured presentations and a panel discussion on applications of pathogen genomics to outbreak detection and intervention. Wondwossen Gebreyes, Hazel C. Youngberg Distinguished Professor and executive director of Global One Health Initiative at The Ohio State University, moderated the panel discussion. Yvan Hutin, director of surveillance, prevention, and control at the Antimicrobial Resistance Division of the World Health Organization (WHO), discussed applications of pathogen genomics to antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Rob Knight, professor and director of the Center for Microbiome Innovation at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), outlined wastewater tracking of pathogen dynamics and a SARS-CoV-2 pathogen genomics initiative. Lisa Purcell, entrepreneur-in-residence at Third Rock Ventures, described the use of genomic sequencing in the development and monitoring of therapeutics. Pardis Sabeti, professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and core institute member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, explored technologies that facilitate use of pathogen genomics in understanding outbreak dynamics and developing countermeasures. Tavis Anderson, research biologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Animal Disease Center, described the use of pathogen genomics in detecting an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1 in cattle and in identifying its source.

GENOMICS TO ADDRESS ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE

Hutin said genomics and whole genome sequencing (WGS) are opening new horizons in understanding and addressing AMR, although the

data generated by those approaches must be interpreted within a broader context to be useful for public health decision making. He explained that phenotypic assessment of antimicrobial drug resistance typically involves clinical assessment and laboratory-based susceptibility testing. Molecular techniques, such as detection of known resistance genes through WGS and other amplifications, must be interpreted in the context of databases that contain genetic variations and their correlation with phenotypes to enable decision making and R&D at various levels of public health, said Hutin.

Hutin highlighted some of the programs organized to address drug resistance in HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. Although the malaria program was the first to address drug resistance through a programmatic approach, the program’s use of WGS remains in an early stage. He posited that this may be related to the composition of artemisinin—an antimalarial drug containing both fast-acting and slower-acting components—which complicates efforts to connect genomics information with clinical outcomes. In HIV/AIDS, most drug resistance monitoring is led through clinical assessment of viral suppression in the patient, with genomics techniques used to confirm cases of suspected resistance. Use of WGS to detect resistance is most firmly established for tuberculosis, of the three conditions. Although the primary method for detecting resistance in tuberculosis is polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, next-generation sequencing (NGS) or WGS is used for broader assessment of resistance, Hutin stated.

Applications of WGS to the broader field of bacterial AMR are emerging, said Hutin, highlighting WHO’s report on the use of WGS for surveillance of AMR in the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (WHO, 2020). In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), new WGS infrastructure and equipment procured by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria as part of the COVID-19 pandemic response mechanisms have improved readiness to address the increasing quantity and complexity of pathogens. This enhanced WHO genomic surveillance has created new use cases at global, regional, and national levels. In the context of AMR, the use of WGS focuses primarily on surveillance of the emergence and prevalence of AMR, investigation of AMR spread (e.g., cluster investigations, distribution across a country), and research to monitor evolution, investigate molecular mechanisms, and develop new diagnostics, drugs, and vaccines.

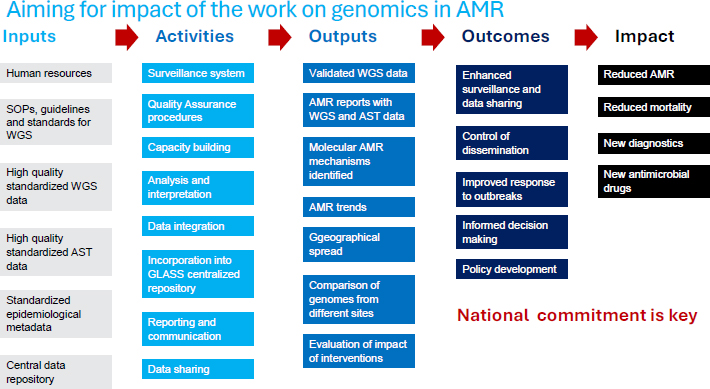

Within this broad multipathogen agenda, Hutin emphasized the need to focus on specific pathogens—using a structured, result-driven approach—to ensure that investment leads to impactful outcomes, thereby building national commitments to the use of genomics in addressing AMR (see Figure 3-1). He added that the WHO Global Genomic Surveillance Strategy developed for pandemic prevention and response also applies to AMR (WHO, 2022). He cautioned that AMR could constitute the next pandemic event.

NOTE: AMR = antimicrobial resistance; AST = antimicrobial susceptibility testing; GLASS = Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System; WGS = whole genome sequencing.

SOURCE: Hutin presentation, July 22, 2024.

However, Hutin is optimistic that bridging genomics applications from existing programs with genomics for emergency preparedness can help maintain readiness for such an event through opportunities such as diversifying the innovation portfolio with a range of applications, strengthening health system resilience, enhancing sustainability by increasing efficiency, accessing existing funding streams, and providing metrics to measure progress.

WASTEWATER TRACKING OF PATHOGEN DYNAMICS

Knight discussed the use of wastewater surveillance to track pathogen and disease dynamics, highlighting that wastewater provides more accurate estimates of infection at the population level than clinical testing alone, particularly in underserved communities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a large-scale wastewater surveillance system was established on the UCSD campus. This was assisted by tools such as magnetic beads to capture and concentrate viral particles from wastewater samples, which substantially shortened the timeline for nucleic acid extraction and analysis. The team established a workflow that streamlines quantitative reverse-transcription PCR, nucleic acid extraction and WGS, and posting of results on a public dashboard to a single-day process (Sheikhzadeh et al., 2021). To make the information available to end users, the university posted daily results on a campus map and issued building-level notifications. These combined efforts resulted in early detection of 85 percent of COVID-19 cases on the UCSD

campus (Karthikeyan et al., 2021). This approach could be broadened to other respiratory pathogens, he suggested.

Wastewater contains a mixture of samples from many people, posing the challenge of untangling genome material from multiple strains, said Knight. Researchers at UCSD used known mixtures of SARS-CoV-2 variant genomes at different proportions to create a maximum likelihood tool that estimates sequencing depth and the relative abundance of different lineages in a given sample to enable segregation of each lineage (Karthikeyan et al., 2022). He noted that the tool yields excellent concordance between real fractions and estimated fraction in mixed samples, with a range of up to five variants. Knight underscored the value of genomic surveillance for pathogens in identifying new variants of concern. A partnership with San Diego County Public Health enabled cross-referencing of UCSD campus data, clinical cases, and county-level data from sampling at three wastewater treatment plants. The resulting analysis revealed that wastewater surveillance detected SARS-CoV-2 and specific variants up to two weeks earlier than observation of clinical cases.

Outlining opportunities to expand wastewater surveillance, Knight posited that these techniques could apply to dozens of respiratory and gastrointestinal pathogens. He shared that UCSD has so far conducted disease surveillance for hepatitis A and mpox by processing metagenomic and meta-transcriptomic samples, which allowed for total DNA or RNA characterization from wastewater. Pathogen identification remains challenging due to the nature of short-read data obtained through analyzing these wastewater samples, but the approach is sufficient to predict infection status for the community as a whole, he noted. Long-read sequencing dramatically improves specificity—albeit currently at the expense of sensitivity—and thus holds great potential for AMR and other situations requiring integration into the whole genome, said Knight. He added that target capture panels show substantial potential as input to metagenomics and amplicon sequencing genomics methods for enrichment.

GENOMIC SEQUENCING TO INFORM THERAPEUTIC USAGE

Purcell outlined the process of using genomic sequencing in developing therapeutics and vaccines to address emerging pathogens or variants and continued monitoring of the effectiveness and use of these medical countermeasures. She explained that monitoring of pathogens occurs continually throughout all stages of therapeutic discovery and development. Companies in this space establish genomic sequencing pipelines for specific therapeutics that typically involve the preclinical phases of target hypothesis, target-to-hit, hit-to-lead, lead optimization, and preclinical testing. An investigational new drug then proceeds through phases of development toward approval.

Once a therapeutic is approved, pathogen monitoring continues throughout the life of the drug. Purcell noted that during research and development for antiviral therapeutics, the antiviral assays for the target pathogen are established early in the preclinical stage. Researchers then determine the resistance profile and assessment methods for the virus. All phases of the clinical stage of development require genotypic and phenotypic characterization of baseline and postbaseline samples from trial participants, which enables assessment for treatment-emergent variants.

Purcell presented the example of a SARS-CoV-2 therapeutic development pipeline, highlighting the accelerated use of genomics and robust collaboration between industry, academic, and government entities that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinicians, caregivers, and patients collected clinical samples to determine viral load and identify the current circulating SARS-CoV-2 viral variants or monitor for changes after administration of a therapeutic or vaccine. Pseudovirus assays were used to evaluate susceptibility. Depending on the pathogen and product, these assays can be quite intensive; she noted that monitoring sotrovimab, a therapeutic monoclonal antibody for COVID-19, involved generating and testing susceptibility for more than 250 pseudoviruses. Subsequent sequencing and in vitro assays to evaluate authentic viral isolates were performed in a Biosafety Level 3 laboratory. Using genotypic data from samples collected globally and available in large public databases (e.g., National Institutes of Health databases, Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data repository), researchers across local pipelines can perform analyses to identify emerging viral variants or changes within a therapeutic’s target sequence or epitope. This pipeline process adapted for SARS-CoV-2 has also been used for influenza, malaria, and bacterial pathogens, she added.

PATHOGEN GENOMICS FOR OUTBREAK EPIDEMIOLOGY

Sabeti discussed the value of pathogen genomics technologies in detecting, understanding, and addressing outbreaks. Her laboratory focuses on issues at the interface of genomic surveillance of pathogens, computational genetic approaches, and genomic approaches to data mining. For example, they have studied the transmission patterns of Ebola virus and SARS-CoV-2 to identify novel mutations and associated infectivity rates (Gire et al., 2014; Lagerborg et al., 2022; Yurkovetskiy et al., 2020). Genomics was also used to track pathogen emergence and transmission during the 2016 mumps epidemic at Harvard University and the 2021 COVID-19 outbreak in Massachusetts where transmission occurred between vaccinated individuals (Lemieux et al., 2020; Wohl et al., 2020). Sabeti emphasized that better systems, such as point-of-need diagnostic assays, are needed to detect and characterize novel or emerging pathogens using genomic sequencing in

settings ranging from large hospitals to rural clinics to private homes. Given the potential for rapid pathogen spread, containing outbreaks also requires connecting information across the grid, from mobile phones to national and global dashboards, she added.

Partnering with the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases and the United States Pathogen Genomics Centers of Excellence (PGCoE), Sabeti and colleagues explored novel diagnostics that use CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) and AI technologies for pathogen detection. Sabeti explained that CRISPR-based diagnostics are a good fit for point-of-need application, as they can conduct molecular tests at room temperature and perform multiplex assays that simultaneously test many pathogens and samples (Ackerman et al., 2020; Welch et al., 2022). Machine learning and generative AI can inform these processes, improving diagnostics for a rapidly changing pathogen (Metsky et al., 2022). These approaches support other diagnostic modalities such as PCR and loop-mediated isothermal amplification, Sabeti said.

Sabeti remarked that in addition to generating data across the ecosystem of infectious disease surveillance, the data must be shared to facilitate state-level monitoring, understand community transmission, and investigate zoonotic crossover of diseases. For instance, her laboratory created a suite of technologies to provide data to the public health workforce that enables pattern identification, as well as providing dashboards for real-time pathogen tracking. They have developed software to conduct Bayesian phylogenetic analysis—the gold standard for understanding pathogen spread—in just 6.5 minutes using a web interface, compared to 6,800 minutes required for Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis by Sampling Trees, another leading tool. Sabeti’s lab has worked with partners at the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases to create the Sentinel program, a disease surveillance system that has trained more than 1,600 individuals in 53 African countries on NGS, bioinformatics, and instrumentation, noted Sabeti. To promote citizen education, her group has created a smartphone app and a textbook that guides secondary school students through all aspects of disease outbreaks. Ultimately, Sabeti and colleagues are focused on building technologies and creating systems-level approaches to study pathogens as they are detected, thereby generating foundational information for developing countermeasures swiftly after an outbreak emerges.

APPLICATIONS OF PATHOGEN GENOMICS IN H5N1 DAIRY CATTLE OUTBREAK

Anderson outlined the use of pathogen genomics to identify and track the H5N1 outbreak in dairy cattle. In February 2024, reports from Texas dairy operations described reduced feed intake and rumination in dairy

cattle, accompanied by an abrupt decrease in milk production (Mielke, 2024). In March, veterinarians in the area observed neurologic symptoms in farm cats that consumed raw cow milk and discovered dead birds on the dairy cattle locations. The USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service National Animal Health Surveillance System, a national network of more than 40 regional labs that test samples from veterinarians and producers, performed sequencing on a panel of various pathogens and confirmed the presence of H5N1 on March 25, 2024 (Burrough et al., 2024). Anderson stated that upon pathogen identification, scientists then needed to determine the source of the outbreak and gather data to inform appropriate control measures.

A suite of analytical techniques can be used with genomic surveillance of diseases to gather necessary information related to this outbreak, said Anderson. Bayesian methods provide data on interspecies transmission mechanisms and timelines; phylogenetic trees of individual genes inform understanding of movement of the pathogen; phylogenetic trees of whole genomes track transmission across host species; and ancestral state reconstruction quantifies frequency of transmission. These methods suggest that a single spillover event from wild birds into dairy cattle occurred in late 2023, and H5N1 then circulated undetected for approximately two months (Nguyen et al., 2024).1 He posited that during this time, the pathogen likely circulated among herds until a sufficient number of sick cattle with clinical symptoms garnered the attention of producers and veterinarians. Researchers used genomic sequencing to compare the virus isolated from dairy cattle with reference influenza virus genomes known to infect avian species to determine whether transmission was driven by a viral factor, host factor, or ecological factors of the dairy production system. They found that the viruses in dairy cattle had acquired two new gene segments from circulation in wild migratory birds. After a single reassortment event, the genotype was maintained as it spread across the United States, Anderson explained. Furthermore, statistical Bayesian methods indicated rapid dissemination of the specific viral strain in March and April 2024. Anderson explained that a substantial amount of animal movement throughout the United States facilitated viral transmission from cows with subclinical or preclinical infections (Nguyen et al., 2024).

In determining infection control strategies, researchers analyzed H5N1 transmission patterns between wild birds, poultry, cattle, domestic mammals, and wild mammals, noted Anderson. They found the virus transmit-

___________________

1 Data as of the workshop (July 22–23, 2024) indicated a single spillover event. As of March 2, 2025, three independent spillover events from wild birds into cattle have been confirmed though genomics analyses. See https://www.aphis.usda.gov/news/program-update/aphis-identifies-third-hpai-spillover-dairy-cattle (accessed March 2, 2025).

ted from dairy cows to other species in more than 10 host transmission events after the initial move from wild birds into cattle. Noting that infection in poultry increases the risk of transmission to humans, he highlighted the significant low-frequency variation within the different host species and the possibility of developing genetic signatures and other evolutionary adaptations that favor mammalian hosts. He explained that developing countermeasures involves determining whether significant variation is present in the pathogen genomes, identifying representative viral strains, and targeting therapeutics and vaccines to those strains. Researchers used PARNAS—a tool for identifying taxa that best represent variations on a phylogenetic tree—to distill these genetic variations in the evolutionary landscape and come up with a strain that embodies the maximum genomic heterogeneity (Markin et al., 2023). By identifying and characterizing this representative strain, researchers can develop therapeutics and vaccines that should be effective for all viral variants found among dairy cattle. Anderson emphasized that this ability relies on integration of knowledge from the field, genome sequencing, analytical tools, and ongoing communication between all involved partners.

DISCUSSION

Interoperability, Data Sharing, and Transparency

Gebreyes asked about interoperability considerations in achieving a system that integrates human, animal, environmental, and wastewater data. Hutin explained that fragmented financing of various vertical disease programs has generated fragmented data systems. For example, he visited a data infrastructure space in South Asia that contained separate computers, operating systems, data structures, and data catalogs for each disease. Despite the current era of big data and AI, simple issues such as data control continue to pose challenges for streamlining operations, he explained. Hutin described a strong laboratory management information system as central to progressive convergence toward interoperability. Moreover, critical data sharing between countries is reliant on rapport and relationship building, Hutin noted, adding that LMICs may be reluctant to share sequences identified if subsequent access to diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines is uncertain. Purcell described the response to the COVID-19 pandemic as a modern mobilization of government, industry, and private individuals against a virus. The NIH Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) partnership—which includes numerous pharmaceutical companies, the Biomedical Advanced Research Development Authority, and other government agencies—incorporated data from wastewater surveillance and facilitated information sharing. Noting

that parallel databases and disease surveillance systems duplicate efforts, Purcell pointed to the importance of groups continuing to share ideas and to keep up-to-date on emerging analytical tools in order to facilitate collaboration. Additionally, she called for more workforce training to keep pace with rapid developments in genomic sequencing, AI, and machine learning.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Applications

Knight stated that newer AI methods—such as transformer and attention models that can track relationships in data and assign levels of importance to inputs—improve performance of phenotype prediction from metagenomic data compared to random forest and other earlier machine learning methods. He emphasized the potential to apply AI to forecasting and to classify wastewater samples according to characteristics of the community. Sabeti agreed that AI will likely fundamentally transform research approaches. For instance, she uses AI-based approaches to detect natural selection in the human genome. Over time, machine learning models become better at detecting which mutations are important in evolutionary adaptation and how these approaches can be applied to pathogens, she explained. Her laboratory is developing improved diagnostics and metagenomic detection tools and leveraging AI-enabled abilities to mine genomic data to improve design of medical countermeasures. Anderson remarked that AI helps to simplify the process of extracting meaning from data but cautioned about the use of biased data to train AI models. He also highlighted the potential to use AI in developing general frameworks that could be used to make causal inferences—for example, toward better understanding the circumstances under which a small fraction of the viruses moving between species actually results in spillover transmission to humans.

Increasing Outbreak Detection Speed

An attendee stated that before the H5N1 virus infected dairy cattle, it had been spreading globally among wild birds, causing substantial losses in seabird populations as well as spilling over into wild mammals. The participant asked how to improve the speed and specificity in outbreak response, assuming that there was a missed opportunity to detect the H5N1 outbreak in dairy cattle sooner. Anderson responded that before detection of that H5N1 outbreak, more than 100 spillovers of avian influenza virus with the specific H5 genotype occurred in North America in more than 20 different mammal species. He also believed that the spillover into dairy cattle was a rare event. He suggested that detection speed could be improved through a process whereby regional laboratories apply backend machine learning algorithms to triage diagnostic data that they receive to flag datapoints that

do not fit established and anticipated presentations (e.g., pathogen type, host species, clinical symptoms). This was the case for identification of the current H5N1 outbreak: obtaining the genome sequencing data took time in the H5N1 dairy cattle case, but once sequencing data were available, the genotype was immediately flagged. Thus, faster movement of samples from the field to the diagnostic laboratories, faster sequencing, and more rapid implementation of intervention efforts would improve outbreak detection and response, said Anderson.

A participant stated that sequences of recently collected wild bird samples often cluster within the cattle outbreak clade, despite ongoing H5 influenza viral strains circulating without transmission to cows. Noting difficulty in assessing whether this is due to a sampling bias or a biological phenomenon, they asked about current barriers that prevent transparent data sharing from federal and state disease surveillance programs. Anderson replied that USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services conducts targeted genomic surveillance for infectious diseases at epidemiologically linked locations and animals, accounting for some of the clustering of sequences from cattle and wild bird samples. As of the workshop, a USDA platform was conducting enhanced disease surveillance in wild birds migrating through North America throughout the 2024 migratory season. He emphasized the value of data that meets FAIR data standards—i.e., data that are findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable. Appropriate annotation of data streams, including those from wastewater, enables reuse of the data in machine learning platforms or genomic epidemiology by other investigators. Underscoring the need for pathogen investigators and public health professionals to use common data ontologies (the systematic ways that data are structured and the terminologies and language used to refer to data), Anderson stated that spillover events and disease outbreaks require different data streams, and the ability to synthesize these streams into a cohesive animal health network advances the mission of pandemic prevention.

Role of Routine Surveillance in Outbreak Detection

An attendee commented on the importance of context in infectious disease genomics: that is, understanding typical background data at baseline conditions will enable the detection of an unusual disease outbreak. Sabeti described infectious disease outbreaks as one of the greatest existential threats to humanity in terms of morbidity, mortality, and economic loss—yet current investment in prevention efforts is incommensurate with the magnitude of that threat. Thus, Sabeti called for a paradigm shift that places greater emphasis on prevention, rather than focusing primarily on reacting to outbreaks. For instance, she suggested investing in routine

diagnostic testing for infectious pathogens, including those that currently lack treatments, such as enteroviruses. To build health system resilience and preparedness, Hutin underscored the value of programmatic communicable disease surveillance that is as pathogen-agnostic as possible and features defragmented epidemiological and lab collaboration.

A participant asked about potential routine use cases for metagenomic sequencing of wastewater. Knight replied that disease surveillance funding waxes and wanes with perceived level of pathogen threat, making routine detection and monitoring difficult to sustain. His most pressing research interest is determining which known pathogens are detectable in wastewater. For example, many researchers were surprised to learn that although SARS-CoV-2 is a respiratory virus, it is easily detected in wastewater, a finding that aligns with the later discovery that SARS-CoV-2 also infects the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, other pathogens not currently associated with the gastrointestinal tract may also be shed through the stool and into wastewater. Knight expressed interest in studying the overall microbial community in wastewater to facilitate detection of anomalies. Abundance of common members in the wastewater microbial community may be perturbed in response to rare pathogens and could thereby indicate the presence of pathogens before they are detected directly with metagenomic reads, he hypothesized. Knight noted that information on chronic diseases can also be gleaned from individual stool samples through the effects of chronic conditions on the gut microbiota and posited that wastewater analysis could be scaled up to monitor for both chronic and infectious disease at a population level.

Diverse Workforce Development

An attendee asked about workforce skillsets needed to expand data collection and perform robust disease surveillance. Sabeti stated that the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the value of expertise from diverse professional backgrounds in outbreak response, such as immunology, bioinformatics, epidemiology, mathematical modeling, communications, social determinants of health, and public policy. She remarked that she often recruits a wide range of expertise for her laboratory, including physicists, computer scientists, mathematicians, biologists, public health professionals, and clinicians. Additionally, she has been working to make genomics tools more intuitive to facilitate training a broad workforce and improve general accessibility to this field. Anderson remarked that ecologists bring a valuable systems-thinking perspective to the systems-level problem of pathogen surveillance. Purcell noted that although drug R&D teams share the same ultimate objective, they typically operate separately and do not share a common language. Therefore, engaging individuals who can discuss

both research and development opportunities is important for translational medicine. Purcell added that effective communication to the public is an area for improvement among many scientists. Moreover, educational efforts to improve the scientific literacy of secondary school students could strengthen the public’s ability to understand scientific conclusions, she said.

Wastewater Surveillance Considerations

A participant asked about technological barriers in wastewater monitoring that need to be overcome. Noting the challenges in working with low concentrations of pathogens, Knight highlighted the need for improved methods for concentrating a broader variety of bacteria, fungi, and viruses from dilute samples. He also noted that UCSD wastewater surveillance relies on commercially available magnetic nanobeads specifically developed to capture and concentrate SARS-CoV-2, but this tool is not available for all pathogens. He added that because systems that provide next-day sequencing results are expensive, a lower price point for faster turnaround sequencing would help expand wastewater monitoring efforts. Furthermore, as many widely used nucleic acid extraction techniques do not work for fungal cells or spores, there is a need for rapid, cost-effective techniques for sample processing that is broadly applicable across different pathogen taxa, Knight added.

Another participant asked whether there are markers that can attribute pathogens detected in wastewater to host species. Knight remarked that total sequencing of the microbial community should reveal taxa specific to the host. Humans, dogs, cattle, and birds all have different microbiomes and, in principle, shotgun sequencing should be capable of discerning these markers, he added. At that point, these markers could be assessed at lower expense using quantitative reverse-transcription PCR, Knight posited.

Summary

Gebreyes highlighted the power of genomics in applications from surveillance to therapeutics. Early detection of novel genomic variants by methods such as wastewater surveillance expands outbreak prevention capacity, he stated. Current events, including outbreaks of H5N1, underscore the continuous potential for pathogens to emerge and reemerge. Understanding the context of host, pathogen, and environment is an important consideration for targeted surveillance, said Gebreyes. He emphasized the need for systems thinking and system strengthening via workforce development, strengthening genomics lab infrastructure, expanding genomic surveillance, and fortifying public health and One Health systems that support and explore the interconnection of human, animal, and environmental health.