Building Health and Resilience Research Capacity in the U.S. Gulf Coast: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (2025)

Chapter: Building Health and Resilience ResearchCapacity in the U.S. Gulf Coast: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

|

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief |

Convened October 29, 2024

Building Health and Resilience Research Capacity in the U.S. Gulf Coast

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

As an integral part of their surrounding communities, Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs) and Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) are often well positioned to conduct community-engaged health and resilience research.1 Yet their ability and commitment to push forward meaningful change in communities is challenged by other aspects of their missions, which include prioritizing education and concurrently working to advance knowledge alongside other institutions in the larger research enterprise.

In 2024 and 2025, the Gulf Research Program (GRP) of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened two workshops to discuss opportunities for Minority Serving Institutions and Historically Black Colleges and Universities to increase participation, competitiveness, and leadership in community-engaged health and environmental research. These workshops focused on applied research in four areas: the combined impacts of extreme weather events and environmental stressors on human health; improving public health data systems; fostering community resilience; and encouraging strategic partnerships. The workshops also examined institutional barriers faced by MSIs and HBCUs2 in the Gulf region. Supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), this convening series complemented previous RWJF-GRP funding opportunities and programming centering on HBCU and MSI leadership in research.

This Proceedings of a Workshop in–Brief provides a high-level summary of the presentations and discussions at the first workshop, held on October 29, 2024, in Houston, Texas.3 The workshop focused on the status of available infrastructures to support MSI-led community-engaged research and explored opportunities for MSIs to lead research efforts related to climate, health, and resilience.

SETTING THE STAGE FOR ELEVATING MSIS

Daniel Burger, GRP Program Director of Health and Resilience, opened by emphasizing the importance of

__________________

1 See Akintobi, T., Sheikhattari, P., Shaffer, E., Evans, C. L., Braun, K. L., Sy, A. U., Mancera, B., Campa, A., Miller, S. T., Sarpong, D., Holliday, R., Jimenez-Chavez, J., Khan, S., Hinton, C., Sellars-Bates, K., Ajewole, V., Teufel-Shone, N. I., McMullin, J., Suther, S., ... Tchounwou, P. B. (2021). Community Engagement Practices at Research Centers in U.S. Minority Institutions: Priority Populations and Innovative Approaches to Advancing Health Disparities Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6675. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126675. Also: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Minority Serving Institutions: America’s Underutilized Resource for Strengthening the STEM Workforce. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25257

2 Throughout this document, MSIs and HBCUs are referred to as separate entities due to differences in designation and establishment. However, they often experience similar challenges in conducting research, as most MSI and HBCU institutions in the U.S. Gulf Coast region are not ranked as R1 institutions.

3 The agenda, speaker biographies, presentations, and video recording of the workshop are available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/building-health-and-climate-research-capacity-in-the-us-gulf-coast-elevating-minority-serving-institutions-as-key-partners-a-workshop-series

inclusive, community-based research, especially as extreme weather events, compounding disasters, and persistent health disparities threaten the Gulf region’s resilience, particularly in historically underserved communities. He pointed out that MSIs and HBCUs are well-positioned to undertake equitable, community-based research. Realizing this potential requires capacity building to enhance MSI and HBCU contributions while diversifying and aligning research with community priorities to foster a safer, healthier, and more resilient Gulf.

Francisca Flores, GRP Program Officer, noted funders’ traditional focus on public health data systems. People seeking health-related services typically enter this system through clinics or hospitals, where data is collected and used by health authorities to identify health trends. These trends inform decisions on how to allocate resources, with universities being one of the institutions that benefit from them. However, those outside this system remain invisible to it, perpetuating health disparities. Explaining that a key challenge has to do with integrating marginalized populations into health systems, Flores noted that MSIs and HBCUs with established community trust are uniquely positioned to bridge this gap. Another challenge is that only 10 to 20 percent of health outcomes are influenced by factors traditionally captured by clinical data, while the majority are shaped by environmental factors—conditions associated with where people live, work, and learn.

She explained that this first workshop has as its aim the exploration of MSI and HBCU capacity for community-based research whose purpose is to address environmental impacts, strengthen public health data systems, and enhance resilience. The insights gained will help the GRP support MSI and HBCU-associated community partnerships set up to improve health outcomes in underserved areas.

KEYNOTE: LESSONS FROM HBCU ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE CENTERS AND CONSORTIA

Highlighting the unique role of HBCUs,4 Robert Bullard, Founder and Director, Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice, Texas State University, commented that many of these institutions have developed specialized research centers and consortia that position them to be both leaders in climate justice as well as educators for the next generation of scientists, researchers, and practitioners. With regard to connecting community and public health concerns with university missions, he noted that HBCUs have long led the way, particularly through environmental justice (EJ) initiatives. The first EJ centers at U.S. universities were founded at HBCUs in the early 1990s; they built on foundational studies, research, and partnerships dating back to the 1970s. He highlighted the HBCU Climate Change Consortium5—including now over half of all HBCUs—that works to strengthen community capacity and direct resources to frontline communities to advance EJ objectives.

Analysis of eight decades of disaster responses found a pattern of unequal treatment, particularly for communities of color, with disparities in pre-disaster infrastructure and post-disaster recovery support.6 Bullard pointed out how despite some progress, HBCUs and MSIs received a very small fraction of federal funding allocated for academic research on climate solutions during recent fiscal years. Additionally, organizations led by people of color were awarded only a minimal portion of available multiyear operational budget grants. Chronic underfunding leaves these institutions under-resourced, Bullard said, despite their potentially vital roles in the most environmentally vulnerable region of the U.S. where climate change impacts disproportionately affect the communities least equipped to prepare for and recover from them. He emphasized that these regions, if adequately funded and supported, hold the potential to drive impactful environmental solutions. Executive Order 14057,7 along with the Inflation Reduction Act8 and the Justice40 Initiative,9 designated investments for underserved commu-

__________________

4 39 percent of the 107 HBCUs are located in Gulf Coast states.

5 More information about the HBCU Climate Change Consortium is available at https://www.bullardcenter.org/hbcu-climate-change-consortium

6 Bullard, R. D., and Wright, B. (2012). The wrong complexion for protection: How the government response to disaster endangers African American communities. NYU Press.

7 Executive Order 14057: Catalyzing clean energy industries and jobs through federal sustainability was superseded by Section 2 of Executive Order 14148 signed by President Trump 20 January 2025. More information available at https://www.fedcenter.gov/programs/eo14057/

8 U.S. Congress. (2022). Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. Public Law No. 117-169, 136 Stat. 1818. Dispersement of funding through the Inflation Reduction Act has been paused by Section 7 of Executive Order 14154 signed by President Trump on January 20, 2025.

9 The Justice40 Initiative established by Executive Order 14008 was revoked by Section 2 of Executive Order 14148 signed by President Trump 20 January 2025.

nities in order to support these efforts. Bullard stressed that HBCUs, MSIs, and their partners were then able to compete for grants to fund solar initiatives, technical assistance, and other community projects, ensuring environmental benefits flowed directly to frontline communities.

In Bullard’s take away messages, he emphasized, first, the significant role played by EJ centers, the HBCU Climate Change Consortium, and community-based organizations in advancing climate justice through research, education, scholarships, and community engagement. Second, he stressed the need to support and strengthen the unique HBCU “Communiversity” research-to-action model,10 which is centered around populations most vulnerable to environmental challenges. Lastly, he proposed creating a special endowment fund to institutionalize the HBCU centers and consortia model for research-to-action initiatives addressing these challenges. He stated that such funding is crucial for the long-term success of these programs.

Rather than following the traditional model of grant-receiving institutions seeking community partnerships after securing funding, HBCUs and MSIs have the potential to establish transparent, genuine collaborations from the outset. Bullard explained it is already the case that these institutions not only value “community science”—which integrates Indigenous Knowledge and lived experience—but also value and promote empowering residents who may not have formal degrees but nonetheless bring invaluable insights to research. HBCUs and MSIs can empower and equip these communities with the knowledge they need to advocate for themselves—and, in so doing, can demonstrate the value of community-based research in not only driving meaningful policy change, but also securing a resilient, equitable future.

Bullard noted that for HBCUs and MSIs to maximize their impact, they can establish and leverage interdisciplinary “hubs” connecting fields such as engineering, health, and policy, thus addressing community needs regarding infrastructure, health, and job creation. Building on existing mentorship structures as well as prioritizing informal dialogues can enable HBCUs and MSIs to both expand their capacity and strengthen faculty expertise, thus fostering diverse and interdisciplinary collaboration to address environmental challenges.

PANEL 1: MSI PERSPECTIVES ON CLIMATE IMPACTS ON COMMUNITIES AND HEALTH IN THE GULF

The first panel highlighted the unique positioning of HBCUs and MSIs—both geographically in disaster-prone areas and through their deep-rooted community connections—which enables them to conduct impactful, community-engaged environmental health research. The session was moderated by Shamarial Roberson, President of Health and Human Services, Indelible Consulting.

LEVERAGING HBCUS AND MSIS AS RESILIENCE HUBS

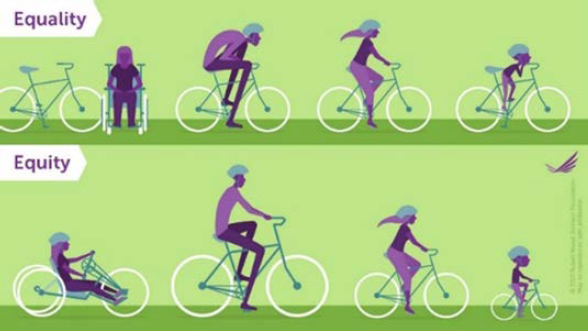

Curtis Brown, Visiting Professor, Virginia Commonwealth University, began by examining the difference between equity and equality. He explained equity involves recognizing and addressing the unequal starting points and circumstances individuals face, whereas equality assumes everyone starts from the same place and therefore should be treated the same (see Figure 1). He highlighted the need to address disparities among communities that are impacted by disaster outcomes.

Brown pointed out that many emergency management policies and recovery programs have been based on inequitable assumptions, leading to inequitable outcomes. Throughout history, there have been recurring failures—based on, in some cases, a lack of data, resources, and/or cultural competence—to address the vulnerabilities of

SOURCE: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2017. Reproduced with permission of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, N.J.

__________________

10 Created by Beverly Wright, this model integrates data collection with efforts to advance EJ. For additional details, see: Wright, D., Wright, B., Babineau, K., Glick, J. L., and Smith, G. (2024). The Communiversity Model: Exploring an Environmental Justice Framework for Community–Academic Partnerships and Its Impact on Capacity to Conduct Research and Policy Action. Environmental Justice. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2024.0033

marginalized communities. To showcase the importance of diversity and community engagement in emergency management, he highlighted a 1927 report that found effective recovery often involved local African Americans in decision-making.11 Brown went on to emphasize the need for equity when it comes to community-based solutions—especially in marginalized underserved communities that are more vulnerable to disasters—and leveraging community organizations in response and recovery efforts. Despite their historic exclusion from federal disaster response, HBCUs have been a critical source of resilience and support, he observed.

Brown discussed how there has been an increasing focus on what are called “resilience hubs,” defined as community-serving facilities that support residents and coordinate resources before, during, and after disruptions.12 Emphasizing how HBCUs have historically functioned as resilience hubs, providing sanctuary during and after disasters, he pointed out that they currently serve as shelters, host community convenings, and engage in outreach and research to support marginalized populations.

He went on to stress that the path forward requires systemic changes needed not only to leverage HBCUs and MSIs towards building resilience—as well as responding to disasters—but also ensuring they receive the necessary funding for hazard mitigation and equitable preparedness strategies. He highlighted the need to collaborate with federal agencies on equitable preparedness, mitigation, and response and recovery strategies, and to update outdated laws that prevent funding from reaching these institutions. Finally, he called for focusing on equitable funding to support HBCUs and MSIs in integrating community-based emergency management efforts and developing a diverse trained workforce that would include decision-makers drawn from the communities they serve to lead disaster preparedness, response, and recovery initiatives.

THE ROLE OF COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS

E. Benjamin Money, Jr., Senior Vice President, Population Health, National Association of Community Health Centers, discussed how providing care for under-insured and uninsured populations, and addressing social service needs outside of traditional medicine, distinguishes community health centers (CHCs) from other healthcare institutions. Additionally, unlike other healthcare institutions, CHC boards are governed by a majority of active patients who oversee operations and funding. Guided by federal statute,13 community health centers address environmental health issues affecting patients, including water and air quality as well as exposure to lead, chemicals and pesticides. CHCs remain integral to both healthcare and environmental health advocacy across the U.S., from early efforts in public health, such as those monitoring the drilling of wells, to preventing waterborne diseases and supporting environmental justice movements, like those in Soul City, North Carolina, and Cancer Alley, Louisiana. He noted that in 2023 CHCs served 32.5 million patients nationwide across 16,000 locations managed by approximately 1,500 CHCs—meaning that one in 10 Americans received care at a CHC.14 These centers reach one in three people living in poverty, one in five uninsured individuals, and 9.4 million children.15 In the Gulf Coast region, CHCs provide care for a significant share of uninsured people—31 percent in Mississippi and 35 percent in Texas16—addressing not only health needs but also environmental risks that disproportionately impact vulnerable populations due to historic racial and social injustices.

Money went on to emphasize that CHCs are deeply rooted in their communities, making them strong partners available for potential collaboration, though forming and sustaining these partnerships are contingent upon the availability of resources. Many CHCs participate across the Gulf states in health center-controlled networks (HCCNs), to enhance care coordination and advocacy, aggregate data and deploy population health analytics to identify disease disparities. Collaborating with CHCs offers unique advantages due to a number of factors: their origins in the Civil Rights Movement; their alignment with the EJ movement; their focus on populations

__________________

11 American National Red Cross. (1927). The final report of the Colored Advisory Commission: Mississippi Valley Flood Disaster, 1927. Washington, DC: American National Red Cross.

12 More information on resilience hubs is available at https://www.usdn.org/resilience-hubs.html

13 Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. § 254b. (2024).

14 National Association of Community Health Centers. (2024). Community health centers report record growth in patients to 32.5 million. https://www.nachc.org/community-health-centers-report-record-growth-in-patients-to-32-5-million/

15 National Association of Community Health Centers. (2024). America’s health centers: by the numbers. https://www.nachc.org/resource/americas-health-centers-by-the-numbers/

16 To see current statistics for each state, see https://www.nachc.org/community-health-centers/state-level-health-center-data-maps/

most impacted by environmental disasters; their statutory authority to address environmental health issues; their community-governed structure and participation in data-sharing networks for health analytics; and their growing involvement in environmental initiatives, particularly in the Gulf region. Some of the current CHC initiatives that Money highlighted include the Florida Association of Community Health Centers’ survey on climate resilience; Mississippi’s response to the Jackson water crisis; and partnerships in Louisiana and Texas with the Environmental Defense Fund and local universities to address the health impacts of environmental hazards.

COMMUNITY RESILIENCE THROUGH PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS

Galveston was the site of the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history—the Great Storm of September 8, 1900—which impacted the island and resulted in a devastating loss of 6,000 lives.17 Later, in April 1947, Texas City experienced the nation’s worst industrial accident when a freighter carrying ammonium nitrate exploded, triggering a second blast that compounded the devastation and claimed approximately 500 lives.18 Philip Keiser, Associate Dean for Public Health Practice, University of Texas Medical Branch and Galveston County Local Health Authority, explained that due to the Galveston County area being surrounded by petrochemical facilities—as well as its limited readiness to handle certain disasters—the region remains highly vulnerable to natural and industrial risks. Additionally, hurricanes, floods, extreme heat, and tornadoes, can all lead to public health threats such as prolonged power outages that can increase heat-related illnesses. With nearby manufacturing plants experiencing flares or fires, and with hazardous materials being regularly transported through the area by truck and train, there is also a risk of chemical spills or accidents. He went on to highlight infectious disease threats and noted, given the busy port and cruise traffic, concerns over terrorism and bioterrorism.

Reflecting on lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, Keiser emphasized that community engagement is vital to maintaining public health, particularly when it comes to gaining trust and countering resistance. Attempts to simply direct people often fail, especially in communities where outsiders may lack credibility. On the positive side, however, he gave an example of selective outreach to African American pastors through prayer breakfasts that fostered strong support, leading to successful vaccine events. He also highlighted the importance of connecting with local groups, such as Chambers of Commerce, to build familiarity and tailor health-related outreach to community interests and needs. Additionally, he stressed the need to establish partnerships with local government officials, hospitals, and Medical Reserve Corps, which were designed to provide essential support and trusted representation in times of crisis and noted that during emergencies when public health leaders are relied upon, this approach builds the foundation for the trust necessary to achieve effective communication.

He explained that when disaster strikes, the successful event response and recovery stages hinge upon successful prior planning and established relationships, which help to align responders and avoid conflicts. For coordination, an incident command structure is critical, with an incident commander in place to centralize decisions while information is relayed by a designated public information officer. He emphasized the need for swift evacuation strategies, utilizing floodplain maps and direct warnings. Often, evacuees lack essential supplies, so responders must quickly arrange for food, shelter, and medical care. However, recognizing that government support can be delayed, he stressed that communities should prepare for at least 72 hours of independent self-sufficiency. Lastly, he encouraged the involvement of individuals as well as organizations at all levels.

Q&A DISCUSSION: REAL-WORLD SOLUTIONS IN RESEARCH

Following the panelists’ presentations, moderator Shamarial Roberson, President of Health and Human Services, Indelible Consulting, questioned how local knowledge and experience can contribute to the success of research at MSIs and HBCUs. Curtis Brown, highlighting creative, flexible-funding-resourced approaches implemented during the pandemic, emphasized how HBCUs and MSIs have enhanced preparedness and response, fostered partnerships with communities to

__________________

17 United States Weather Bureau Office. Special Report on Galveston Hurricane of September 8, 1900. https://vlab.noaa.gov/web/nws-heritage/-/galveston-storm-of-1900

18 For more Information visit: https://www.usace.army.mil/About/History/Historical-Vignettes/Relief-and-Recovery/114-Texas-City-Fire/

improve mitigation and recovery, and advocated for systemic changes to sustain such innovations.

Addressing a question on how public health institutions could better collaborate with communities, E. Benjamin Money, Jr. discussed not only opportunities for public health institutions to collaborate with CHCs and the community, but also the advantages associated with leveraging local knowledge to improve disaster responses. Money highlighted the Community Lighthouse Project,19 which pre-positions resources and services in disaster-prone areas to enhance effectiveness and accessibility during crises by the communities they are intended to serve.

Roberson posed a question about how HBCUs and MSIs could bridge gaps in data access and collaboration with public health authorities. In response Philip Keiser stressed the important role of community engagement and data transparency in fostering these collaborations. He also discussed the need for trust-building, relationship development, and sharing research findings with these communities to foster buy-in and collaboration to enhance community engagement in research. In addition, Keiser noted the challenges of balancing academic rigor with community needs and advocating for stronger relationships to support long-term engagement.

Brown, responding to a question from Roberson on systemic barriers, called for adjustments in policies and procedures to eliminate inequities and obstacles to responsiveness. Regarding community needs, Money suggested introducing reforms to improve responsiveness and effectiveness.

PANEL 2: MSI AND HBCU INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH EXPERTISE, CAPACITIES, AND INFRASTRUCTURE

The second panel focused on institutional research expertise, capacities, and infrastructure at MSIs and HBCUs. This panel explored the diverse research capabilities and infrastructures at these institutions, addressing funding options, workforce and research program development, and the implications of Research 1 (R1)/Non-R1 designations.20 Discussions highlighted the unique challenges faced by public and private institutions, particularly those shaped by funding limitations and political pressures. This session was moderated by Paul Tchounwou, Dean, School of Computer, Mathematical and Natural Sciences, Morgan State University.

STRENGTHENING DISASTER RESPONSE INITIATIVES AT FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY AND OTHER MSIS

Ashley Davis, Director of Emergency Management & Assistant Vice President at Florida A&M University, noted the simultaneous recovery work being done in response to multiple recent disasters—e.g., the May 10, 2024, tornadoes and 2024 hurricane season—that have strengthened Florida A&M University’s (FAMU’s) disaster preparedness and reinforced the need for constant readiness. He reflected on the ongoing learning process associated with these efforts, noting that alongside the work being done to maximize resources and strengthen resilience, a major focus has been on building capacity for both immediate response and the concurrent recovery and infrastructure rebuilding. He emphasized not only FAMU’s role as a resiliency hub providing facilities to assist those in need in the community, but also the work being done at the same time through Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Public Assistance and mitigation grant programs to enhance resiliency.

He highlighted the operational impacts of disasters on FAMU’s normal operations, often requiring shifts to remote learning, temporary campus closures, the rescheduling of events, and the deployment of resources for emergency sheltering. In terms of continuity plans, he described how critical functions such as housing, food services, and public safety are prioritized while there is, at the same time, the activation of an emergency community system (e.g., FAMU ALERT21) to ensure timely communication.

Davis pointed out several institutional strengths, including FAMU’s success in disaster preparedness and response, as well as research-based contributions to the Gulf Coast’s resilience efforts. He also noted the strong support from FAMU’s leadership, which has allowed the emergency management department to expand its team

__________________

19 More information about the Community Lighthouse Project is available at https://www.togethernola.org/

20 For more information about different Carnegie classifications for research designations, see https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/carnegie-classification/research-designations/

21 More information about the FAMU ALERT communication system is available at https://www.famu.edu/administration/division-of-finance-and-administration/emergency-management/famu-alert/index.php

and, by so doing, enhance community impact. Additionally, he stressed the potential for MSIs, when provided with adequate resources and support, to lead community-based operations. For example, despite the frequency of recent disasters, FAMU continues to support the community and enhance regional resilience by coordinating with state agencies, which have the potential to provide insights on how the broader research community can strengthen disaster research and response capacities.

ENHANCING CAPACITY AND RESEARCH CULTURE AT SMALLER INSTITUTIONS

Abigail Newsome, Associate Vice President for Academic Affairs, Mississippi Valley State University, shared insights on the role of research at smaller institutions, emphasizing that while not all institutions conduct R1-level research, those engaged in research efforts bring added value to their faculty, students, and institution. Regardless of the size or type of institution, she stressed how research can be integral to academic activities, especially in STEM fields, and requires ongoing infrastructure, capacity, and expertise.

She went on to point out that while research infrastructure is often viewed primarily in terms of facilities, it also involves equipment, digital infrastructure, and knowledge-based resources, each requiring substantial investment. Equipment is crucial but often under-supported in terms of maintenance and calibration. Also, digital infrastructure is frequently overlooked, but essential for handling large datasets from research; she underscored how it requires adequate storage, analysis speed, and adequate housing to prevent equipment damage. Other infrastructure needs include not only research facilities with the necessary utilities suitable for housing complex equipment, but also knowledge-based resources like faculty expertise and archival materials that are foundational for research and classroom learning.

Newsome emphasized the ability of smaller academic institutions to foster a shift in institutional culture toward valuing research alongside teaching as they strive to become more research engaged. This transition benefits students through hands-on learning opportunities that enrich their educational experience. She went on to stress the importance of supporting, despite limited resources, faculty development and retention. Effective grant management, collaboration with experts in other fields, and network-building are key for smaller institutions. By prioritizing specialized support and partnerships, researchers at these institutions can boost their research impact and, at the same time, achieve higher levels of research engagement.

EXPANDING STEM AND SUPPORT FOR RESEARCH EFFORTS

Briana Hauff Salas, Associate Professor of Environmental Science, Our Lady of the Lake University, noted that her institution is a small Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) with a total population of 2,100 students, about half of whom are graduate students working primarily online in the field of social work. The student body is predominantly underserved, with 70 percent identifying as Hispanic, 57 percent Pell-eligible, and 39 percent first-generation students. Despite its small size, the institution, located in San Antonio, Texas, holds the distinction of being the country’s first designated HSI. Research in STEM programs takes place largely through directed studies with undergraduates; also, due to limited research infrastructure, STEM research often occurs off-campus.

She said her university is in a transition phase, shifting from a teaching-focused institution to one with increasing research expectations. Though classroom instruction has historically been the focus for faculty, and this continues to be the case, recent hiring decisions have started to prioritize applicants with strong research backgrounds. The university now has 26 research grants, eight of which are in math and sciences. Salas went on to highlight not only the institution’s McNair Program, which aims to give undergraduates research opportunities, but also a recent CURE—Classroom Undergraduate Research Experience—workshop, which brings research into the classroom. Noting the close faculty-student relationships fostered because of the absence of graduate students, she commented on how the directed study courses are in high demand.

Despite facing challenges such as staff retention, lack of English as a Second Language (ESL) support, and student availability to commit to research experience, Salas highlighted promising developments for both expanding research and supporting STEM programs. Teaching

loads are high—with three lecture courses and two or three labs per semester being required—yet the university is actively working to incentivize research by revising faculty evaluation procedures (particularly by instituting different requirements for tenure and non-tenure-track faculty) in order better to support research engagement. Additionally, plans are underway for a new STEM building that would improve facilities and expand research capabilities. Though budget constraints create some uncertainty about program expansions, the recent restructuring of faculty roles to support research, as well as future plans that include the launching of new graduate programs, inspires optimism.

JACKSON STATE UNIVERSITY’S PATH TO R1 STATUS AND EXPANDING RESEARCH IMPACT

Jackson State University (JSU), an HBCU, is actively working to elevate its research status from a R2 research designation to R1.22 ConSandra McNeil, Interim Vice President of Research and Economic Development, Jackson State University, pointed out that JSU has an annual average of $50 million in external grants, with research capabilities including cybersecurity; material science and engineering; health disparities; artificial intelligence; and data science. Though the majority of grant funding goes to STEM programs, the College of Health Sciences also receives support. Hosting key research centers—including the Research Centers in Minority Institutions (RCMI) Center for Health Disparities Research, and the Jackson Heart Study Graduate Training and Education Center—JSU was one of the first HBCUs to receive funding for a Coastal Resilience Center that, since 2002, has had a nation-wide impact.

McNeil noted that there is momentum at JSU for establishing a Jackson Research Lab, which would involve collaboration with all four Mississippi research consortium schools. This lab would strengthen the institution’s infrastructure; would attract more researchers and students; would increase research expenditures; and could help to advance JSU toward R1 status. The lab could also boost funding in areas such as AI, cybersecurity, and data science; promote tech innovation; enhance partnerships with other Mississippi institutions and local businesses; and expand economic development and workforce opportunities that would, in turn, encourage students to remain in the state after graduation.

Key initiatives on the road to R1 status that McNeil highlighted include Research Engagement Week, which has grown significantly due to participation from external partners, faculty, and students. Additionally, along with webinars, she mentioned a faculty seed grant program, a grant-writing coaching program, a travel program, and research leadership programs. Other efforts include a research need-related faculty survey, which has shaped support for faculty development. She emphasized ongoing efforts centered around securing competitive salaries to attract and retain more research faculty, staff, and post docs; enhancing access to cutting edge instrumentation and improved labs; and increasing capacity building through federal grants.

Q&A DISCUSSION: LEVERAGING UNIQUE STRENGTHS TO ADVANCE RESEARCH CAPACITY IN MSIS AND HBCUS

Paul Tchounwou, Dean, School of Computer, Mathematical and Natural Sciences, Morgan State University, opened the post-panel discussion by asking panelists about the unique challenges HBCUs and MSIs face in developing research programs and infrastructure. Ashley Davis highlighted how vital it is for HBCUs and MSIs to pursue research opportunities that have the potential to influence federal and state emergency management policies, particularly when it comes to inclusive disaster recovery. Davis also pointed out that regular testing is crucial to ensure that current infrastructure works as designed in emergency situations. Briana Hauff Salas emphasized that many grants at her university focus on capacity-building to upgrade infrastructure, while ConSandra McNeil called for more state and federal support, including the streamlining of grant processes to strengthen competitiveness to build research capacity—a point noted by Abigail Newsome as well.

In response to questions about limited infrastructure affecting research collaboration, McNeil went on to discuss not only Jackson State’s success in securing large-

__________________

22 2025 Carnegie Classifications designate R1 and R2 institutions by their annual Research & Development (R&D) expenditures and available doctoral research degree programs. R1 institutions spend at least $50 million in total R&D spending and have at least 70 doctoral research degrees; R2 institutions spend at least $5 million in total R&D and have at least 20 doctoral research degrees available. More information is available at: https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/carnegie-classification/classification-methodology/basic-classification/

scale grants despite resource limitations, but also JSU’s innovative approach to forming interdisciplinary teams combining expertise from STEM, social sciences, and health sciences. Davis also addressed infrastructure readiness, sharing FAMU’s strategies for emergency power systems and the lessons learned from recent tornadoes.

PANEL 3: EXPLORING OPPORTUNITIES FOR BUILDING RESEARCH CAPACITY IN THE GULF

The final panel explored opportunities to build research capacity in climate, health, and resilience within the Gulf region. Panelists addressed existing research gaps, highlighted the strengths and contributions of MSIs, and outlined actionable strategies for securing resources and advancing application. This panel was moderated by Erin Lynch, President of Quality Education for Minorities Network.

ANALYZING FEDERAL FUNDING: OPPORTUNITIES FOR INCREASING MSI PARTICIPATION

To better understand the Gulf region’s funding landscape, workshop planning committee member Erin Lynch, President of Quality Education for Minorities (QEM) Network, began the panel by sharing the results of an analysis conducted at the request of the workshop planning committee to review data from federal obligation databases, specifically USAspending.gov and the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) RePORTER. Lynch explained that the analysis revealed that while Texas received substantial federal funding, Mississippi and Alabama each received less than $150 million. She highlighted various types of federal funding, including cooperative agreements, direct loans, direct payments, and block grants. A deeper dive into four federal funding categories—public health, climate change, community resilience, and environmental stressors—revealed that many block grants are allocated in these particular areas. Within these categories, the majority of project grants were directed toward Geosciences—which is closely linked to climate resilience research—followed by Biological Sciences. Projects related to agriculture, social impact, and health sciences also received significant funding. Lynch also pointed to direct payments aimed at supporting climate resilience and infrastructure efforts, including programs like the Emergency Broadband Benefit Program and Emergency Connectivity. Over the past year, NIH federal obligations represented approximately $683 million across these four categories—though only a small portion went to MSIs. Highlighting a clear opportunity for a more equitable distribution of funds, Lynch drew attention to the fact that just a few non-MSI institutions captured nearly 30 percent of the total funding across 133 organizations, with one institution receiving nearly two-thirds of this sum.

HOW MSIS LEAD RESEARCH THROUGH COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS

Emphasizing the need for community-driven climate, health, and resilience research, Rebecca Efroymson, Distinguished Scientist, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, urged the adoption of mechanisms for rapid research funding, especially to address extreme events or environmental health crises. Noting gaps in areas like compounding events and cumulative impacts on health, she highlighted the importance of resilient infrastructure; understudied areas such as compound events (e.g., back-to-back hurricanes) and cumulative impacts (e.g., power outages affecting health); and fostering evacuation readiness in inland communities. Her discussion underscored the value of trust-based partnerships with affected communities; of long-term funding for MSI engagement; and of integrating lived experiences into climate models. Examples of health research areas she mentioned included air pollution, urban heat islands, heat waves, power outages, and contaminated water risks post-storm. Shifting to resilience, she highlighted not only the importance of community-driven research with regard to short-term responses prior to the arrival of FEMA, the National Guard, the Red Cross, and others, but also the need for resilience metrics.

She went on to discuss MSIs’ long history of EJ work as well as both the importance of long-term, community-trusted partnerships in areas impacted by extreme events as well as close to planned energy and decarbonization facilities. Emphasizing the value of engaged students and faculty with lived experiences in historically marginalized and overburdened communities, she noted the strong culture of collaboration within these institutions. She also pointed out MSIs serve as valuable assets for research in the Gulf, providing expertise in physical, environmental and social science.

Efroymson outlined various opportunities for MSIs, starting with the availability of internships that can enhance institutional capacity in targeted areas and the importance of measuring variables, such as urban heat islands and sea level rise. Additionally, she stressed the importance of not only participation in knowledge co-production, but also helping agencies shape research solicitations by responding to Requests for Information (RFIs). Furthermore, she stressed the need for community benefits plans for energy projects that address health and resilience.

Highlighting an initiative that could inspire similar programs elsewhere, Efroymson closed by discussing the Climate Leaders Academy model that creates graduate student “transdisciplinarians”—drawn mostly from underserved communities—in climate modeling, data science, and policy. Additionally, she commented on how the Department of Energy’s Urban Integrated Field Laboratories are leveraging through MSIs the lived experiences of stakeholders in order to research urban stressors like floods, heat islands, and air pollution.

RESOLVING ENVIRONMENTAL INEQUITIES AND BRIDGING GAPS IN RESEARCH

Kenya Goodson, Research Consultant, Minority Health & Health Equity Research Center, Dillard University, began by outlining the distinctions between and among various types of MSIs, such as HBCUs—which are among the nation’s oldest—along with Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs); Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institutions (AANAPISIs); Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs); Alaska Native-Serving and Native Hawaiian-Serving Institutions (ANNHs); Native American-Serving Nontribal Institutions (NASNTIs); and Predominantly Black Institutions (PBIs). Emphasizing that these institutions are often located in low-income areas, many having been affected by environmental issues. She noted that each institution has unique needs shaped by its geographic location and cultural context.

Goodson moved on to identify climate- and health-related research gaps where MSIs could make substantial contributions in areas associated with health and socio-economic factors; impacts on marginalized communities; rising sea levels; and human migration.

Emphasizing the importance of addressing both mitigation and adaptation responses, she pointed out that while some regions have benefited from mitigation efforts, additional research is necessary to evaluate the long-term outcomes of these initiatives. She also identified areas of opportunity for more climate and health research, including the impact of climate issues on mental health; under-nutrition; migration; maternal and child health; and the inequities faced by vulnerable populations.

Noting how MSIs are often located in communities directly impacted by climate- and health-related inequities, Goodson emphasized that they serve as frontline institutions in areas affected by systemic issues like redlining and environmental contamination. She highlighted the distinct needs of urban and rural communities, noting that many students from underrepresented backgrounds pursue service-based careers, such as nursing or health fields, to support their communities. Overcoming climate and health challenges, she argued, will require interdisciplinary approaches to addressing and filling gaps in the research.

While data on environmental programs at MSIs is limited, Goodson emphasized that many institutions are already integrating environmental issues into their STEM curricula. To better prepare future generations for upcoming challenges, she stressed the need to incorporate more environmental topics across all STEM disciplines. Since MSIs have fewer environmental science programs than predominantly white institutions, increasing exposure to environmental and health research is key to closing this gap. She pointed to initiatives such as the HBCU Climate Change Consortium and the Florida International University (FIU) STEM Transformation Institute that are working to incorporate climate change research into education. Highlighting work being done to address systemic health inequities in Louisiana, Goodson commented on Dillard University’s Collaborative Data Analysis (CoDA) project that engages not only community members but also students as leaders in research.

ADVANCING NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH COLLABORATION AND SUPPORT

Jean Shin, Deputy Director, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of the Director, introduced the NIH’s new

initiative, Engagement and Access for Research-Active Institutions (EARA),23 whose aim is addressing barriers that research-active institutions (RAIs) face when it comes to enhancing their research capacity and infrastructure. The initiative focuses on strengthening RAI awareness and access to the NIH resources and opportunities; fostering communication and collaboration between the NIH and RAIs; and broadening participation across the NIH—with a specific focus on RAIs such as HBCUs, TCUs, and MSIs that historically serve underrepresented populations in biomedical and behavioral research.

While the current focus is on RAIs with moderate success in receiving NIH funding, he explained that future phases will target institutions with little or no NIH funding, especially those that have not yet applied for grants. He also highlighted the initiative’s collaborations with various NIH offices, “diversity catalysts,” and liaisons. EARA’s strategy includes general outreach by providing updates and resources through both a website and newsletter.

He discussed an ongoing pilot project involving about 50 RAIs that volunteered to undertake enhancing their understanding and use of NIH funding opportunities. This project operates on the basis of a “matchmaking” process designed to connect NIH Institutes, Centers, and Offices (ICOs) that match or fit well with the focus of a particular RAI’s research concept. He emphasized that the project aims to build confidence and familiarity with NIH resources, particularly given how many institutions lack proactive engagement with program officers—possibly because, in at least some cases, they do not know how effectively to engage with them.

The first phase of the pilot project involved six HBCUs and utilized a focus group approach to match faculty from the participating institutions with the relevant ICOs. Highlighting the project’s success, he noted that 71 out of 74 faculty received “warm handoffs” to program officers with whom they had not previously engaged. The initiative garnered positive feedback from faculty, with many likening the matchmaking process to a “concierge service” for grants.

Q&A DISCUSSION: LEVERAGING MSI STRENGTHS TO ADDRESS COMMUNITY RESILIENCE, EQUITY IN GRANT FUNDING, AND FACULTY DEVELOPMENT

Erin Lynch, moderator, highlighted the complex effects of consecutive disasters on communities, particularly the educational setbacks faced by youth (notably those in rural counties) due to repeated trauma. Emphasizing that MSI and HBCUs are well-positioned to contribute to research—especially those with strong social science and education programs—Lynch stressed the importance of a transdisciplinary approach that incorporates fields such as sociology, social work, education, psychology, and environmental science. She then broadened the conversation, focusing on not only the assets and strengths of MSI and HBCUs, but also how they can ensure their research tackles these complex issues while at the same time leveraging existing strengths, particularly in community partnerships.

A concern was raised by a participant about whether universities with larger funding allocations were receiving disproportionate attention in the grant funding process—and whether the associated decision-making ensured equitable scoring, particularly for HBCUs and MSIs. Jean Shin and Lynch stressed the importance, to ensure fairness, of reviewers representing diverse backgrounds and training. Lynch noted that participating in review panels not only allows institutions to challenge misconceptions about their capabilities but also helps reviewers improve their grant-writing skills through firsthand experience.

The issue of reviewer compensation was also addressed, with participants explaining that payment varies by agency. To clarify this point, Paul Tchounwou observed that reviewers, despite sometimes spending up to 48 hours reviewing proposals, are typically compensated only for the two meeting days. Lynch asked if the experience was valuable, and Tchounwou responded by saying it can provide valuable insights into agency expectations and proposal structures, which can be beneficial for faculty development.

An audience member addressed the burden of unpaid work done by faculty at MSIs and HBCUs and the need for more strategic collaboration to reduce silos and workload. Lynch supported these ideas, mentioning a “service buyout” option designed to help alleviate commit-

__________________

23 Under Executive Order 14173, signed by President Trump on 20 January 2025, NIH’s EARA Initiative is no longer active.

tee responsibilities and create more time for research. Another participant pointed out that serving on panels can foster professional networking, leading to long-term partnerships and funding opportunities.

GROUP ACTIVITY: MAPPING INSTITUTIONAL ASSETS AND CAPACITIES FOR CLIMATE AND HEALTH RESEARCH

André Porter, Senior Program Officer with the National Academies’ Board on Higher Education Workforce, facilitated a group activity aimed at discussing potential future actions. The first part of the activity focused on identifying the various assets or dimensions of capacity related to climate change and health research. Tasked with mapping these assets—specifically those linked to different institution types, such as MSIs, HBCUs, and TCUs—participants discussed how partner organizations could facilitate further engagement. The second part of the activity involved asset mapping, where participants assessed how these assets could contribute to different research programs or research topics related to climate change and health.

The goal was to align assets with research questions tailored to the Gulf region’s needs, which were organized into four key areas: assessing climate change impacts on public health in marginalized communities; enhancing community adaptability to environmental stressors; improving public health and other data systems for climate-related surveillance; and examining links between energy production, disaster, and public health.

Table 1 maps, in relation to climate and health research, institutional assets and capacities that were shared by individual participants at the end of the workshop. It highlights key discussion points for each asset, providing insight into the strengths and challenges faced by these institutions with regard to not only addressing climate and health impacts but also enhancing community resilience.

Participants also considered how capacity building efforts for MSIs, HBCUs, and TCUs can leverage several key assets. Infrastructure strengths include the ability to tailor community engagement to diverse environments, such as rural or urban settings, while addressing the unique needs of institutions based on size and geography. Enhanced capacity in grants management was recognized as essential by many participants, covering areas such as sponsored research, post-award financial oversight, and contract administration to support growing research portfolios. One participant noted that many institutions are mission-driven, with a notable emphasis on human-centered approaches that prioritize community needs and student outcomes. Several participants also pointed out that federal designations provide HBCUs and TCUs with distinct advantages over MSIs with enrollment-based criteria, influencing both enrollment strategies and capacity-building opportunities.

TABLE 1

Mapping Assets and Capacities for Climate and Health Research Across MSIs, HBCUs, and Other Institutions: Discussion Points

| ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON PUBLIC HEALTH IN MARGINALIZED COMMUNITIES | |

| Data Capacity |

|

| Community Trust and Partnerships |

|

| Academic Excellence |

|

| Community Engagement |

|

| ENHANCING COMMUNITY ADAPTABILITY TO ENVIRONMENTAL STRESSORS | |

| Holistic Research Frameworks |

|

| Flexibility in Research |

|

| Strong Community Connections |

|

| Building Local Expertise |

|

| Robust Networks and Partnerships |

|

| Commitment to Research and Writing |

|

| Pro Bono Contributions |

|

| IMPROVING PUBLIC HEALTH AND OTHER DATA SYSTEMS FOR CLIMATE-RELATED SURVEILLANCE | |

| Cultural and Historical Resources |

|

| Training and Workforce Development |

|

| Community Involvement |

|

| Data Collection Infrastructure |

|

| Community Engagement Strengths |

|

| EXAMINING LINKS BETWEEN ENERGY PRODUCTION, DISASTERS, AND PUBLIC HEALTH | |

| Interdisciplinary Collaboration |

|

| Community-Centered Focus |

|

| Influence on Policy |

|

| Empowering Communities |

|

| Water Resource Expertise |

|

NOTES: HBCUs = Historically Black Colleges and Universities; HSI = Hispanic-Serving Institutions; MSI = Minority-Serving Institution; TCU = Tribal Colleges and Universities.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Workshop planning committee co-chairs Shamarial Roberson and Berneece Herbert concluded the day by sharing their reflections. Roberson commented on the breadth of knowledge and rich information shared throughout each presentation. HBCUs and MSIs offer more to their communities than only being institutions of higher education; they also serve their surrounding communities during disasters as resilience hubs. Within these institutions, opportunities exist to address infrastructure needs with additional support for grants management and faculty training that contribute to an increased capacity to conduct research. She echoed the importance of partnering with organizations such as FQHCs to help close the data gaps in health and resilience research. Herbert added that while there continue to be ongoing and meaningful connections between MSIs and communities, there is more opportunity for partnership and collaboration to look forward to, especially at the next workshop in this series.

DISCLAIMER This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief has been prepared by Heather Kreidler as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The committee’s role was limited to planning the event. The statements made are those of the individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all participants, the project sponsors, the planning committee, the Gulf Research Program, or the National Academies.

REVIEWERS To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Robert Kopp, Rutgers University, and Hussam Mahmoud, Colorado State University. The review comments and draft manuscript remain confidential to protect the integrity of the process. Marilyn Baker, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

PLANNING COMMITTEE Berneece Herbert (Co-Chair), Jackson State University; Shamarial Roberson (Co-Chair), DSR Public Health Foundation Inc.; Mona N. Fouad, University of Alabama Birmingham; Lance M. Hallberg, University of Texas Medical Branch; Aurelia Jones-Taylor, Aaron E. Henry Community Health Services Center, Inc.; Erin Lynch, Quality Education for Minorities (QEM) Network; Briana H. Salas, Our Lady of the Lake University; Paul Tchounwou, Morgan State University

STAFF Alexandra Allison, Research Associate; Daniel Burger, Board Director; Jaye Espy, Program Officer; Francisca Flores, Program Officer; Denna Medrano, Senior Program Assistant; André Porter, Senior Program Officer; Laila Reimanis, Associate Program Officer.

SPONSORS This project was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2025. Building Health and Resilience Research Capacity in the U.S. Gulf Coast: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/29113.

|

Gulf Research Program Copyright 2025 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. |

|