Unraveling the Neurobiology of Empathy and Compassion: Implications for Treatments for Brain Disorders and Human Well-Being: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (2025)

Chapter: Unraveling the Neurobiology of Empathy and Compassion: Implications for Treatments for Brain Disorders and Human Well-Being: Proceedings of a Workshop - in Brief

|

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief |

Convened May 19 and 21, 2025

Unraveling the Neurobiology of Empathy and Compassion: Implications for Treatments for Brain Disorders and Human Well-Being

Empathy, or the ability to understand and share the feelings of others, develops in early childhood and supports vital behaviors such as social bonding, parental care, and prioritizing relationships (Bernhardt and Singer, 2012; Decety, 2015; Levy et al., 2019b). Compassion, a related concept, involves both awareness of another’s suffering and a desire to alleviate it—for which empathy comes before compassion (Stevens and Benjamin, 2018). Despite the importance of empathy and compassion in maintaining well-being and guiding prosocial behavior, their evolution, neural bases, and role in neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders are still unclear (Decety, 2015; Gilbert, 2020).

Both empathy and compassion engage a broad network of brain regions (de Waal and Preston, 2017; Decety, 2015; Marsh, 2018; Stevens and Benjamin, 2018) and may be involved in such conditions as substance use disorders (Cox and Reichel, 2023), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Fantozzi et al., 2021), autism spectrum disorder (Fatima and Babu, 2023), disruptive behavior disorders (Fairchild et al., 2019), personality disorders, (De Brito et al., 2021), and eating disorders (Cox and Reichel, 2023). Walter Koroshetz, director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, described empathy and compassion as central to what motivates many neuroscientists to pursue their research, given that these traits are “important aspects of ourselves” which drive us to reduce suffering due to neurological, psychiatric, and substance use disorders.

On May 19 and 21, 2025, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened a 2-day virtual workshop to explore the underlying neurobiological mechanisms of empathy and compassion; to consider the influence of social interactions, psychological states, and the environment; and to explore how this knowledge may be harnessed to treat brain disorders and foster human well-being (see Box 1 for highlights from the workshop discussions).

PRE-CLINICAL MODELS RELEVANT TO EMPATHY AND COMPASSION

Defining Empathy and Compassion Across Species

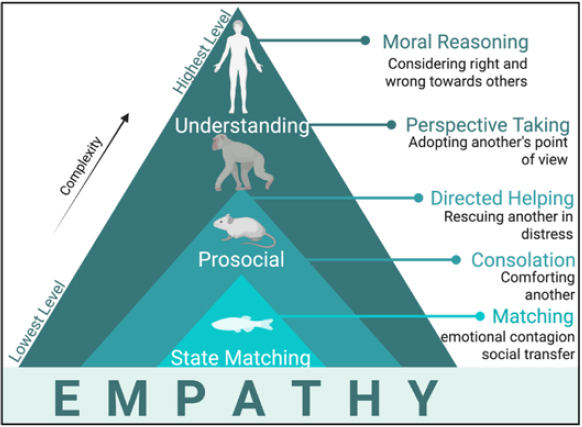

In the field of social neuroscience, Claus Lamm, professor of biological psychology at the University of Vienna, noted that empathy tends to be defined as feeling the emotional state of someone else while maintaining a clear distinction between one’s self and the other. Lamm emphasized that empathy is not an inherently “moral” emotion that one ought to feel, nor does it automatically motivate prosocial behavior (i.e., acts that provide support to another). Instead, empathy exists along a spectrum of behaviors ranging from automatic responses, such as mimicking motor behaviors, to highly regulated

BOX 1

Workshop Highlights

- Empathy differs from compassion and prosocial behavior, as the capacity to feel another’s emotions does not necessarily translate into prosocial behavior. (Lamm)

- Advanced neural imaging and recording approaches have revealed distinct neural networks involved in empathy. Specifically, the anterior insular cortex (AIC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) are active during direct and empathic experiences, while the ACC, AIC, nucleus accumbens, and amygdala coordinate activity to process vicarious pain, fear, and reward. (Chang, Hong, Lamm, Smith)

- Infants and young children show a natural tendency for prosocial behavior, and empathy can be developed through fear processing, caregiver interactions, and interbrain synchrony (the coordination of neural activity between people). (Feldman, Grossmann, Warneken)

- Empathy exists on a spectrum, with considerable variation in how individuals experience and express it. Age, cultural factors, lived experiences, risk conditions (such as early adversity, autism, or prematurity), and social context can all shape how empathy manifests and its progression to compassion. (Atanassova, Bhatt, Feldman, Gordon, Lockwood)

- Navigating conditions that affect empathy such as autism, sociopathy, and psychopathy requires compassion from others, in part because trust and fear influence empathic engagement. (Gagne, Marshall, Milton)

- Studying the neurobiology of empathy and compassion may reveal therapeutic targets for clinical conditions characterized by empathic difficulties. (Karlin, Marsh, Waller)

- Empathy and compassion are not fixed traits—they can be developed and enhanced through targeted interventions such as parenting approaches, classroom programs, compassion meditation, and specialized empathy training for health care providers. (Gazzola, Gordon, Mobley, Raaum, Wager, Waller)

- Digital technology presents both opportunities and challenges for empathic development, especially among young people on social media. (Gottlieb, Kurian)

responses, such as feeling concern for someone else or performing a costly act of altruism. Investigating empathy through a neuroscientific lens, he said, “helps us understand each other better, but also how we misunderstand each other.”

Mounting evidence suggests that one can identify fundamental principles of empathy that seem to be conserved across mammals (Decety, 2015). Steve Chang, associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at Yale University, said that when studying empathy across species, it becomes important to define empathy in terms of the neural computations that support it, using frameworks such as reinforcement learning that can evaluate prosocial actions and outcomes. He also emphasized the importance of taking differences in social and ecological structure into account when interpreting empathy-related findings across species. Weizhe Hong, professor of neurobiology, biological chemistry, and bioengineering at the University of California, Los Angeles, added that researchers need to clearly differentiate among the separate neural processes underlying empathy, compassion, and prosocial behavior. To help align work across species,

Monique Smith, T. Denny Sanford Institute for Empathy and Compassion professor and assistant professor at the University of California San Diego, suggested that researchers design studies that match behaviors, stimuli, and neural imaging techniques across rodents and humans (see Figure 1).

Neurobiological Correlates of Empathy for Pain

Evidence from neuroimaging studies suggests that the same brain regions—primarily the anterior insula cortex and the midcingulate cortex—activate when someone directly experiences pain and when the person empathizes with the pain of another (Lamm et al., 2011). However, these results are limited since functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which measures blood flow to the brain rather than neural activity itself, cannot reveal how active brain regions process pain. In a follow-up study, Lamm’s team found that a placebo painkiller—a pill that participants believed was an effective painkiller but contained no active ingredients—suppressed both the feeling of and empathy for pain (Rütgen et al., 2015a) and that this effect was blocked by an opioid antagonist (Rütgen et al., 2015b, 2021). Other neuroimaging studies have pinpointed the right supramarginal gyrus, which develops slowly until age 25 and declines in older adults, as essential for distinguishing between self and other (Riva et al., 2016).

NOTE: While the highest levels of understanding may be reserved for humans, nonhuman animals such as rodents and invertebrates exhibit simpler forms of empathy and prosocial behavior.

SOURCE: Presented by Monique Smith on May 19, 2025; created with BioRender.com.

There is evidence across rodents, nonhuman primates, and humans that understanding another’s emotional states, actions, or sensations relies on the same neural circuits involved when the individual itself feels emotions, takes actions, or takes in sensory information (Lamm et al., 2011; Paradiso et al., 2021). Valeria Gazzola, associate professor at the University of Amsterdam and co-lead of the Social Brain Lab at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, suggested that overlapping neural activations between direct and vicarious experiences may play a role in teaching individuals to avoid danger and to avoid causing harm to others (Keysers and Gazzola, 2021; Keysers et al., 2022). Her research group also observed that individuals with psychopathy showed reduced activation of empathy-related neural circuits when watching emotional scenes but could voluntarily boost that activation if instructed (Meffert et al., 2013).

Smith studied these shared neural mechanisms by observing interactions between pairs of mice, where one is given a localized pain stimulus and the other is not. Overlapping neural circuits were activated whether a mouse was experiencing pain directly or witnessing another mouse in pain. Unique circuits were required for distinct forms of vicarious anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the nucleus accumbens in response to vicarious pain, and the amygdala in response to vicarious fear. As in rodents, Chang observed coordinated activity between the ACC and the amygdala—specifically, distinct information flowing to and from the amygdala to the ACC—during prosocial decision making and experiencing vicarious reward in nonhuman primates (Dal Monte et al., 2020; Gangopadhyay et al., 2021; Putnam et al., 2023).

Connections Among Empathy, Prosocial Behavior, and the Environment

Lamm said that although empathy does not necessarily or solely drive altruism, empathy is positively correlated with prosocial behavior (Hartmann et al., 2022). In his research, Hong observed mice licking the wounds of injured mice experiencing pain (Zhang et al., 2024) and demonstrating rescue-like behavior toward unconscious mice (Sun et al., 2025). In another study, Hong’s team identified a specific population of neurons in the medial amygdala that appeared to drive comforting behavior toward other animals (Wu et al., 2021).

There are also some sex differences in empathy-related behavior in various species, although the causes of these differences are not clear. Smith said that female mice use social touch to comfort other mice less than males, while Chang reported that in his experience, female monkeys appear to have more sustained social attention than males. Gazzola proposed that humans and nonhuman animals may show socially influenced sex differences in propensity for empathy but not raw ability. Chang added that beyond sex, nonhuman primates with greater social dominance tend to be more generous with subordinates, so long as the environment has enough resources to share. Hong has not observed this social dominance–related effect in mice. While animal studies in rodents and nonhuman primates reveal patterns in empathy-related behavior and neural activity, researchers interested in better understanding how empathy develops in humans will study the emergence of prosocial behavior in human children.

HUMAN DEVELOPMENT OF EMPATHY AND COMPASSION

Early Childhood Development of Empathy-Related Prosocial Behaviors

One common assumption in developmental psychology is that young children transform from selfish egoists into prosocial altruists through social learning. Felix Warneken, professor of psychology at the University of Michigan and director of the Social Minds Lab, conducted a series of studies testing this assumption. In each study, an experimenter pretended to struggle with a task, such as picking up a dropped object or opening a door. By the time they are 18 months old, toddlers across diverse cultures consistently and proactively help the experimenter, even when the helpful act is effortful and unrewarded (Warneken, 2018). This behavior has also been observed in chimpanzees performing similar tasks, both with human experimenters and other chimpanzees (Warneken and Tomasello, 2006; Warneken et al., 2007). Interestingly, young children who are rewarded for helping learn to help less when no reward is offered, indicating that young children are intrinsically motivated to help (Warneken and Tomasello, 2008). Given these findings, Warneken proposed a model (Warneken, 2018) depicting young children as “naïve altruists that turn into more mature cooperators” who gain social experience that can solidify or expand these early tendencies “but in some circumstances also destroy them.”

Although humans and great apes both demonstrate prosocial behavior in early childhood, human infants seem to be more fearful than great apes, said Tobias Grossmann, professor of psychology at the University of Virginia (UVA) and director of the UVA Baby Lab. While heightened fearfulness is often viewed as maladaptive, Grossmann said it can help infants grow into more concerned, cooperative adults (Grossmann, 2023). In studies testing face processing in infants, a bias toward fearful faces emerges around 7 months as emotional face processing starts to emerge (Krol et al., 2015). Related studies found that 14-month-old toddlers who exhibited a greater fear bias as infants were more likely to help in tests of prosocial behavior (Grossmann et al., 2018). These effects are linked to dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation, suggesting that the region might inform how infants respond to distress, said Jessica Stern, assistant professor of psychological science at Pomona College and director of the Family, Attachment, and eMpathy Lab.

The Role of Interbrain Synchrony in Empathic Development

Infants develop empathic capacity by synchronizing their behavioral and neural rhythms with their parents, according to Ruth Feldman, Simms-Mann Professor and director of the Center of Developmental, Social, and Relationship Neuroscience at Reichman University. According to Feldman, the frontotemporal interbrain network—which connects right and left frontal areas with right and left temporal areas of the parent and child’s brains—expands over time, synchronizing neural rhythms across parents and children as well as across other closely attached pairs (Schwartz et al., 2024). Over the course of development, she said, children learn to coordinate increasingly complex social behaviors with others, as their brains synchronize across different oscillation frequencies as they get older (Djalovski et al., 2021; Schwartz et al., 2022; Shapira-Endevelt et al., 2021). “Empathy functions as a social glue by binding brains together,” she said. “Helping parents provide better synchrony to their infants in various high-risk contexts,” she suggested, “will provide children with better foundations for empathy.”

Evidence from a range of studies suggests that children growing up with more secure attachments and better neural synchrony tend to develop more prosocial behavior, Feldman said. Grossmann added that secure attachment and fear responding are also positively correlated, which in turn predicts heightened prosocial behavior.

Factors Shaping the Development and Loss of Empathy

Lamm proposed that individual differences in interoception, social biases, and other factors such as education may also shape one’s capacity for empathy. According to Zach Gottlieb, Stanford University student and founder of the Gen Z wellness platform Talk with Zach, young people face unique challenges to the development of empathy, including mass sociopolitical polarization, the lingering effects of pandemic disruptions, and the ubiquity of smartphones and digital technology. Feldman added that such factors as maternal depression and geopolitical chaos impair both empathic behavior and the neural networks involved in empathy (Apter-Levi et al., 2013; Levy et al., 2019a; Pratt et al., 2017). That said, Warneken pointed out that “we are very malleable” and that interventions—particularly in early childhood—can help individuals develop empathy later in development (Flook et al., 2015; Knafo-Noam et al., 2018; Lozada et al., 2014).

Cultural factors may also shape empathic development, as Gottlieb has observed on his platform, Talk with Zach. For instance, he said, families who openly discuss mental health tend to foster greater comfort with vulnerability in their children. Age also appears to influence empathy and prosocial behavior, according to Patricia Lockwood, professor of decision neuroscience and Sir Henry Dale Fellow and Jacobs Foundation Research Fellow at the University of Birmingham. Studies in humans have found that healthy older adults across a wide range of cultures are more willing than younger adults to donate money and work harder to help others (Cutler et al., 2021; Lockwood et al., 2017, 2021), an effect hypothesized to be mediated by age-related declines in dopamine (Bäckman et al., 2006). Feldman suggested that traumatic experiences can also influence empathic capacity and that early caregiving experiences can determine whether trauma enhances or reduces that capacity. Building on such observations, researchers are now identifying key priorities for advancing understanding of the development of empathy.

Potential Next Steps Toward Understanding the Developmental Origins of Empathy

Moving forward, Warneken suggested that researchers explore how empathy may be constrained or biased toward certain individuals, such as family members, especially in nonhuman animal models. Lockwood recommended applying theories from other fields, such as behavioral ecology, to measure prosocial behavior in humans. To better align results across species, Feldman proposed exploring methods for studying the neural basis of empathy that do not depend on human-specific cognitive processes. When studying human development specifically, Grossmann emphasized, it is important to view children as “active creators of their own development” rather than solely products of their parents’ behavior (Davidov et al., 2015).

DISORDERS OF EMPATHY AND COMPASSION AND POTENTIAL THERAPIES

Psychopathy and Related Disorders

Disorders affecting empathy are poorly understood, underdiagnosed, and undertreated, according to Abigail Marsh, professor in the Department of Psychology and the Interdisciplinary Program in Neuroscience at Georgetown University. The lack of recognition and resources for these issues creates serious consequences for individuals with the disorders as well as for their families and their communities. “To the degree that empathy and compassion are products of identifiable, measurable processes in the brain,” Marsh emphasized, “these processes can sometimes go awry, just like any other function of the body.” She added that “when people have a disorder that causes empathic difficulties, it can be hard for others to see that disorder as a disorder” and urged the field to advance its biological understanding of medical conditions such as psychopathy and increase compassion for affected individuals.

Autism and the Double Empathy Problem

Young people with autism often express a “sense of social disjuncture,” said Damian Milton, senior lecturer in intellectual and developmental disabilities at the University of Kent, who is himself autistic. However, cognitive science research also shows that neurotypical people struggle to understand the emotional responses of autistic people (Sheppard et al., 2016) and tend to form negative first impressions of them (Stagg et al., 2014). Milton described this as a “double empathy problem”

(Milton, 2012), where “the breakdown in interaction between autistic and non-autistic people is not solely located in the mind of the autistic person, but largely due to the differing perspectives of those attempting to interact with one another.”

This empathic disconnect is particularly evident in the lived experiences of families navigating autism. Kelli Marshall, Indigenous enrollment advisor for the First Peoples House of Learning at Trent University, shared her experience raising her son, who was diagnosed with autism at age 4. While he could read at a 12th-grade level by age 5, he struggled to feel empathy and compassion like other children his age did. To help him navigate social life, Marshall taught him to identify emotions in others through contextual cues such as music and facial expressions, a tool he continues to use as a teenager. He also learned some unspoken rules of social interaction by watching and mimicking his neurotypical twin sister, Marshall said.

However, Marshall noted that when her son interacts with people outside of his family, he does not receive much empathy, making it more challenging for him to empathize in return. “It’s hard to mimic or mask when what you’re seeing reflected back at you is nothing but hostile,” she explained. Marshall advocated for schools to run workshops teaching empathic skills to students and suggested that parents could also benefit from similar resources.

Moving Beyond Stigma to Understanding Low Affect Disorders

Similar empathy-related challenges exist for individuals with different lived experiences. Patric Gagne, writer, former therapist, and advocate for people suffering from sociopathic, psychopathic, and antisocial personality disorders, described growing up as a child with undiagnosed sociopathy in this way:

Certain emotions, like happiness, sadness, and anger, came naturally, if somewhat sporadically. But the social emotions, the learned emotions—things like guilt, shame, empathy, remorse, and even love—did not. For the most part, I felt nothing, and I didn’t like the way that nothing felt, so I acted out to fill the void. It was like a compulsion.

Research suggests that stress associated with this kind of dissociation may manifest as destructive behavior, which Gagne said could be the brain’s “way of trying to jolt itself into some semblance of normal.” Yet, despite the challenges that disorders affecting empathy create for diagnosed individuals and their communities, few resources exist to support them. Education and health care systems may not recognize their diagnosis or respond to it with care and are in dire need of therapeutic help, acceptance, and more accurate representation, Gagne said.

She suggested that reframing disorders of empathy as “low-affect disorders” rather than using stigmatized terms such as “psychopathy” could remove some of the shame that prevents some parents from seeking diagnoses for their children. Marsh added that it is also important not to make assumptions about the upbringing or past trauma of someone with a disorder of empathy because this adds to the shame parents feel when their child acts out. Giving children the space to safely acknowledge their lack of feeling, Gagne said, can expediate self-acceptance for people with psychopathic traits and make these traits easier for researchers to measure.

Understanding how empathy develops in children with these traits requires specialized approaches. Rebecca Waller, associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania studying socioemotional development, child psychopathology, and personality development, explained that her research group studies “child callous–unemotional (CU) traits,” including lack of empathy, since “psychopathy” as a construct does not exist in young children. These traits predict more severe antisocial behavior across the lifespan (Hawes et al., 2020). In direct tests of emotional recognition, Waller found that children with higher CU traits were worse at recognizing emotions, less physiologically engaged in response to evocative stimuli, and worse at identifying the needs of others (Lynch et al., 2024; Paz et al., 2024; Plate et al., 2023; Powell et al., 2024).

While treatments such as parent management training can reduce symptoms of disruptive behavior in children, a sizeable post-treatment gap still exists between children with and without CU traits (Perlstein et al., 2024). Waller’s ongoing work aims to harness computer vision tools to derive objective metrics of the affective challenges these children face, which may improve diagnostics and the field’s ability to translate neuroscientific

data across species. As researchers refine these sophisticated tools to study empathy-related disorders, they may uncover new possibilities for targeted interventions.

Potential Pharmacological Interventions for Empathy-Related Disorders

Historically, pharmacological research for autism spectrum disorder has focused on suppressing comorbid conditions, but Dan Karlin, chief medical officer at MindMed, suggested that empathogenic medications could help people with empathy-related disorders increase their ability to recognize emotion in themselves and others. MindMed is developing MM402, a right enantiomer of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) that targets serotonin receptors to increase feelings of connectedness, empathy, and compassion while minimizing unwanted stimulant-like side effects (Pitts et al., 2018). Designed as a daily empathy enhancer to be used in a way similar to how stimulant medications are used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Karlin said that MM402 puts “control and power back into the hands of the patient and allows them to choose how, when, and most likely how much of the drug, if approved, working with their health care provider, would be helpful to them.”

However, the potential benefits of such interventions may vary considerably among individuals. Milton, who is living with autism, said that at his age, he would not be interested in taking a drug like MM402, noting “I’m quite used to being me.” Milton added that among those with autism spectrum disorder, some people may find empathy-enhancing drugs helpful while others may not.

REAL-WORLD IMPACTS OF EMPATHY AND COMPASSION

The Impact of Social Media and Artificial Intelligence on Empathy and Compassion

Gottlieb said that in the digital age, many teenagers spend more time alone and less time connecting face-to-face, with over a third using social media “almost constantly” (Office of the Surgeon General, 2023; Vogels et al., 2022). He identified several concerning aspects of social media use: it drives constant social comparison and a false sense of closeness, it exposes users to polarizing content designed to reinforce their existing beliefs, and it contributes to fatigue by overloading users with a constant stream of information. However, he also highlighted its benefits, including making it possible for people to find global communities and maintain distant friendships and elevating historically marginalized voices. Paurvi Bhatt, former chief executive officer of the now-sunset Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers, similarly cautioned that while technology and social media can increase empathy for distant, diverse strangers, it can also disconnect people from their local communities. Both Gottlieb and Bhatt emphasized that intentional use of social media is crucial: Gottlieb advocated for setting boundaries to keep social media empathy-expanding rather than mindless, while Bhatt said that future digital tools must reinforce—not replace—real human connections.

Despite the challenges digital technology poses to empathy and compassion, Gottlieb emphasized that technology and artificial intelligence (AI) are democratizing mental health resources, making low-cost tools such as therapy chatbots available to anyone with a smart-phone. He added that social media can expand empathy by introducing global perspectives that otherwise might go unconsidered. Nomisha Kurian, assistant professor at the University of Warwick focusing on empathetic AI and child-safe design in large language models, observed that this exposure appears to be making young people more empathetic about people who are different from them.

Kurian highlighted the fundamental changes that AI is bringing to how people—especially young people—express and experience empathy and compassion. Because the large language models powering chatbots are typically trained on adult datasets and may lack broader context for a given conversation with a child, she said, an “empathy gap” can form when children interact with them. AI models can produce responses that are age-inappropriate or potentially distressing for young users, which Kurian said she considers the most significant risk of AI for children. However, she also recognized AI’s potential as an empathic teaching tool, saying that it could be useful for role-playing sensitive scenarios like bullying while protecting children from trauma.

Empathic Relationships Between Patients and Medical Care Providers

Sonja Raaum, associate professor in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Utah, said that despite being told to be compassionate throughout her 7 years of medical training, she was never taught what

compassion entailed in practice. However, Raaum said, compassion is a teachable skill that should be integrated into everyday patient interactions, such as validating concerns and documenting patient wishes rather than dismissing them. Compassionate patient interactions are associated with numerous tangible benefits, including reduced pain sensitivity (Sarinopoulos, 2013), shorter hospital stays (Beach, 2021), and higher quality-of-care ratings (Boss, 2024).

However, Raaum said that if a health care system prioritizes efficiency above all else, it can undermine empathy and compassion. Medical students, who presumably entered health care intending to help others, are desensitized as they encounter suffering during clinical training. By the end of training, half of medical students report burnout and cynicism (IsHak et al., 2013). The prevailing “competency-based medical education” framework compounds this problem by underemphasizing compassion, she said. Raaum advocated for teaching compassionate skills early in medical training and optimizing them in clinical settings.

Neuroimaging research is beginning to reveal how empathic relationships between providers and patients manifest in the brain. Care providers send subtle but profound verbal and nonverbal signals that shape their patient’s hope and resilience, Wager said. These empathic factors can have a stronger effect on psychotherapy efficacy than the treatment form itself (Wager and Atlas, 2015; Wampold, 2015). This effect is particularly evident in the treatment of nociplastic pain, where the problem stems from the brain rather than tissue damage (Ashar et al., 2022). As care providers guide patients through safe pain exposure, an “alliance and trust is really required for treatment, engagement, and acceptance,” Wager said. His fMRI research demonstrated this principle directly. People were shown images of computer-generated doctors before receiving thermal pain stimuli, and those whose “doctors” had faces perceived as being more trustworthy reported feeling less pain and also had reduced neural pain markers and dampened pain perception than those whose were shown images with less trustworthy faces (Anderson et al., 2022).

In health care, Wager said, sex, gender, and racial concordance between providers and patients can also significantly increase trust. Raaum said that there may be underlying physiological differences between male and female brains—such as differences in exposure to certain hormones such as oxytocin—that interact with sociocultural factors to create empathic differences between male and female care providers. Mary Gordon, founder, president, and chief executive officer of Roots of Empathy, suggested that in medical training “we don’t pay enough attention to [trainees’] personhood or to the world’s expectation of how they should behave,” given their gender. Wager added that a major barrier to training compassionate male care providers is their resistance to empathy, because “they see it as oppositional to being resilient and functional.”

Both Wager and Raaum emphasized the need for effective workplace mental health supports for care providers. Raaum advocated for practical interventions, such as childcare resources, and mentioned ongoing research exploring whether psychedelics may be able to help providers experiencing severe burnout. Wager recommended that because over-activating the brain’s “empathic distress system”—which happens often in health care settings—can lead to burnout, practitioners draw from contemplative traditions that emphasize the need to sustainably help others by holding their stress at a distance. Wager pointed to neuroimaging data that show that monks learn to maintain their empathic capacity long-term by responding to negative images not with negative emotions, but with compassion (Ashar et al., 2016).

However, the relevance of these skills extends beyond medical care settings. Bhatt reminded workshop participants that empathy and compassion are not only essential in clinical practice but are also critical in the context of everyday caregiving—roles that nearly everyone will take on or require at some point in their lives—underscoring their universal importance. She emphasized that the entire health system, from clinicians to support staff, needs to be included in these conversations. Bhatt also highlighted cultural competency as an essential element of empathic care, noting that “every generation and different phase of immigration that comes here is going to be facing a different reality,” so building empathic bridges across cultures and generations will be crucial.

POTENTIAL STRATEGIES FOR CULTIVATING EMPATHY AND COMPASSION

Gordon created the Roots of Empathy program, which brings an infant and the infants parent or parents into various classrooms over the school year, allowing children to observe the attachment relationship that is foundational to a baby’s development of empathy. A trained instructor guides the children in observing the infant’s cognitive, physical and emotional development—learning about the baby’s feelings and providing opportunities to share about when they felt the same feelings as the baby. Through this experiential learning, children begin to understand the baby’s emotions, their own emotions, and those of their classmates—developing emotional literacy in the process.

Roots of Empathy is intended to break intergenerational cycles of violence and dysfunctional parenting by addressing what Gordon sees as the underlying cause—“a profound absence of empathy.” In the discussion, fear was brought up as an emotion. Gordon said that children learn to express their own feelings when they see the baby express emotions such as fear, which can be elicited by such things as a school bell or other sudden noise. The children see the baby’s fear calmed through the secure attachment relationship with the parent. In this nonjudgmental environment, children are free to share emotions and learn about caring responses, shaping how they positively relate to one another and build connections that support their resiliency and mental health. When these skills are developed at scale, Gordon said, they make a difference: “If you’ve got a whole classroom of children who can read one another’s emotional cues,” she said, “they pick you up before you fall down.” School-based interventions were also highlighted by Marshall as a way to cultivate empathy at an early age, but similar resources might benefit parents as well.

According to Wager, “fear is antithetical to the ability to experience somebody else’s distress and suffering” because it focuses the brain on responding to immediate threats, suppressing exploratory and empathic thought processes. Raaum and Gordon agreed that learning about embodiment and listening to bodily cues can help people of all ages appropriately address challenging emotions like fear.

Gordon said that “if we want children to grow up healthy, mentally well, and empathic, we need to start today—because they will change the world.” These educational interventions align with emerging neuroscience research on the foundations of empathic capacity. Dimana Atanassova, postdoctoral researcher at the Donders Institute for Brain Cognition and Behavior at Radboud University, suggested reframing empathy research around the principle that individuals “only empathize to the extent to which [they] feel emotions [themselves].” This view aligns with neurobiological evidence that direct and vicarious emotional experiences activate the same brain regions (Bernhardt and Singer, 2012). Other evidence in support of this idea includes studies showing that people with psychopathic traits are generally less sensitive to pain and consequently underestimate the pain of others (Atanassova et al., 2025; Brazil et al., 2022). However, when people with psychopathic traits are explicitly instructed to try to feel what another person is feeling, their empathy heightens. Atanassova said that their generally blunted emotional experience reflects a reduced capacity to empathize, not a lack of motivation to do so.

Other neuroimaging studies show that incarcerated individuals with a higher number of psychopathy traits have reduced activation in their prefrontal and paralimbic “meaning making system” which normally generates feelings of warmth and care (Ermer et al., 2012). However, “compassion can be learned with practice,” Wager said. His research group has found evidence that intentional compassion practice both increases activation in the meaning making system and boosts charitable giving behavior (Ashar et al., 2016, 2021).

Researchers are also exploring how to build empathic skills in adults, particularly those in high-stakes professions. William Mobley, Distinguished Professor of Neurosciences at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine, emphasized that while it is possible to show empathy and compassion in stressful situations, this requires skill that many people lack. Mobley proposed developing “skillful empathy” that builds on a neurobiological understanding of the differences between affective and cognitive empathy, so that individuals can attend to and resonate with others’ emotional states while still

reducing the risk of negative emotional contagion. He also observed that different neural networks activate when a person empathizes versus when that person engage in compassionate action, suggesting a need for training programs that help people transition between these states. Such programs, he argued, should focus on leaders at the “cutting edge” of prosocial action—caregivers, physicians, clergy, and politicians—because “we have an obligation to help our leaders understand the importance of empathy and compassion.”

POTENTIAL OPPORTUNITIES FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Speakers highlighted several opportunities for the future investigation of empathy and compassion. Andrew Breeden, chief of the Social and Affective Neuroscience Research Program at the National Institute of Mental Health, pointed out the need for rigorous approaches to measuring animal behavior and the importance of building integrative frameworks that span multiple levels of analysis. Gentry Patrick, Kavli and Dr. William and Marisa Rastetter Chancellor’s Endowed Chair in neurobiology at the University of California San Diego, added that technological advances will be essential for analyzing behavior in rodents and nonhuman primates and in comparing and translating those findings to human systems.

Jessica Stern suggested that understanding the behavioral hallmarks, cognitive advances, and changes in brain activity that characterize typical empathic development could help scientists better identify early signs of atypical development and potential targets for therapeutic interventions. She also proposed that studying the factors shaping individual differences in empathy can inform policy decisions and best practices in parenting, education, and health care. Culture and community may play an important role in determining how empathy translates into compassion, Patrick said. Marsh expressed hope that developing insights into individual differences in empathic abilities will advance the treatment of empathy-related disorders, building on work by such researchers as Waller and Karlin. Dawn Lavell Harvard, director of the First Peoples House of Learning at Trent University, called for research into how empathy can be used to build trust and improve caregiving systems.

When asked about opportunities for the field to move forward, speakers identified similar priorities. Kurian emphasized the need for AI developers to intentionally design products with empathy and compassion in mind, especially when creating tools that “engage with social systems of exclusion or marginalization.” Mobley expressed optimism about the field’s readiness, noting that “we have the neuroscientific tools that we need” and can now “build on what we know to craft curricula and programs to target empathy and compassion.” The challenge ahead lies in effectively translating existing neurobiology research into educational programs, technological design, and systemic changes that can enhance society’s collective capacity for empathy and compassion.

REFERENCES

Anderson, S. R., M. Gianola, N. A. Medina, J. M. Perry, T. D. Wager, and E. A. Reynolds Losin. 2023. Doctor trustworthiness influences pain and its neural correlates in virtual medical interactions. Cerebral Cortex 33(7):3421–3436.

Apter-Levi, Y., M. Feldman, A. Vakart, R. P. Ebstein, and R. Feldman. 2013. Maternal depression from birth to six impacts child mental health, social engagement, and empathy: The moderating role of oxytocin. American Journal of Psychiatry 170:1161–1168.

Ashar, Y. K., J. R. Andrews-Hanna, T. Yarkoni, J. Sills, J. Halifax, S. Dimidjian, and T. D. Wager. 2016. Effects of compassion meditation on a psychological model of charitable donation. Emotion 16(5):691–705.

Ashar, Y. K., J. R. Andrews-Hanna, J. Halifax, S. Dimidjian, and T. D. Wager. 2021. Effects of compassion training on brain responses to suffering others. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 16(10):1036–1047.

Ashar, Y. K., A. Gordon, H. Schubiner, C. Uipi, K. Knight, Z. Anderson, J. Carlisle, L. Polisky, S. Geuter, T. F. Flood, P. A. Kragel, S. Dimidjian, M. A. Lumley, and T. D. Wager. 2022. Effect of pain reprocessing therapy vs. placebo and usual care for patients with chronic back pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 79(1):13–23.

Atanassova, D. V., I. A. Brazil, C. E. A. Tomassen, and J. M. Oosterman. 2025. Pain sensitivity mediates the relationship between empathy for pain and psychopathic traits. Scientific Reports 15(1):3729.

Bäckman, L., L. Nyberg, U. Lindenberger, S.-C. Li, and L. Farde. 2006. The correlative triad among aging, dopamine, and cognition: Current status and future prospects. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 30(6):791–807.

Beach, M. C., J. Park, D. Han, C. Evans, R. D. Moore, and S. Saha. 2021. Clinician response to patient emotion: Impact on subsequent communication and visit length. Annals of Family Medicine 19(6):515–520.

Bernhardt, B. C., and T. Singer. 2012. The neural basis of empathy. Annual Review of Neuroscience 35(1):1–23.

Boss, H., C. MacInnis, R. Simon, J. Jackson, M. Lahtinen, and S. Sinclair. 2024. What role does compassion have on quality care ratings? A regression analysis and validation of the SCQ in emergency department patients. BMC Emergency Medicine 24(1):124.

Brazil, I. A., D. V. Atanassova, and J. M. Oosterman. 2022. Own pain distress mediates the link between the lifestyle facet of psychopathy and estimates of pain distress in others. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 16:824697.

Cox, S. S., and C. M. Reichel. 2023. The intersection of empathy and addiction. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 222:173509.

Cutler, J., J. P. Nitschke, C. Lamm, and P. L. Lockwood. 2021. Older adults across the globe exhibit increased prosocial behavior but also greater in-group preferences. Nature Aging 1(10):880–888.

Dal Monte, O., C.-C. J. Chu, N. A. Fagan, and S. W. C. Chang. 2020. Specialized medial prefrontal–amygdala coordination in other-regarding decision preference. Nature Neuroscience 23(4):565–574.

Davidov, M., A. Knafo-Noam, L. A. Serbin, and E. Moss. 2015. The influential child: How children affect their environment and influence their own risk and resilience. Development and Psychopathology 27(4 Pt 1):947–951.

De Brito, S. A., A. E. Forth, A. R. Baskin-Sommers, I. A. Brazil, E. R. Kimonis, D. Pardini, P. J. Frick, R. J. R. Blair, and E. Viding. 2021. Psychopathy. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 7(1):49.

de Waal, F. B. M., and S. D. Preston. 2017. Mammalian empathy: Behavioural manifestations and neural basis. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 18(8):498–509.

Decety, J. 2015. The neural pathways, development and functions of empathy. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 3:1–6.

Djalovski, A., G. Dumas, S. Kinreich, and R. Feldman. 2021. Human attachments shape interbrain synchrony toward efficient performance of social goals. NeuroImage 226:117600.

Ermer, E., L. M. Cope, P. K. Nyalakanti, V. D. Calhoun, and K. A. Kiehl. 2012. Aberrant paralimbic gray matter in criminal psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 121(3):649.

Fairchild, G., D. J. Hawes, P. J. Frick, W. E. Copeland, C. L. Odgers, B. Franke, C. M. Freitag, and S. A. De Brito. 2019. Conduct disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 5(1):43.

Fantozzi, P., G. Sesso, P. Muratori, A. Milone, and G. Masi. 2021. Biological bases of empathy and social cognition in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A focus on treatment with psychostimulants. Brain Sciences 11(11):1399.

Fatima, M., and N. Babu. 2023. Cognitive and affective empathy in autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 11:756–775.

Flook, L., S. B. Goldberg, L. Pinger, and R. J. Davidson. 2015. Promoting prosocial behavior and self-regulatory skills in preschool children through a mindfulness-based Kindness Curriculum. Developmental Psychology 51(1):44–51.

Gangopadhyay, P., M. Chawla, O. Dal Monte, and S. W. C. Chang. 2020. Prefrontal–amygdala circuits in social decision-making. Nature Neuroscience 24(1):5–18.

Gilbert, P. 2020. Compassion: From its evolution to a psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology (11):586161.

Grossmann, T. 2023. Extending and refining the fearful ape hypothesis. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 46:e81.

Grossmann, T., M. Missana, and K. M. Krol. 2018. The neurodevelopmental precursors of altruistic behavior in infancy. PLOS Biology 16(9):e2005281.

Hartmann, H., P. A. G. Forbes, M. Rütgen, and C. Lamm. 2022. Placebo analgesia reduces costly prosocial helping to lower another person’s pain. Psychological Science 33(11):1867–1881.

Hawes, S. W., R. Waller, W. K. Thompson, L. W. Hyde, A. L. Byrd, S. A. Burt, K. L. Klump, and R. Gonzalez. 2020. Assessing callous–unemotional traits: Development of a brief, reliable measure in a large and diverse sample of preadolescent youth. Psychological Medicine 50(3):456–464.

IsHak, W., R. Nikravesh, S. Lederer, R. Perry, D. Ogunyemi, and C. Bernstein. 2013. Burnout in medical students: A systematic review. Clinical Teacher 10(4):242–245.

Keysers, C., and V. Gazzola. 2021. Emotional contagion: Improving survival by preparing for socially sensed threats. Current Biology 31(11):R728–R730.

Keysers, C., E. Knapska, M. A. Moita, and V. Gazzola. 2022. Emotional contagion and prosocial behavior in rodents. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 26(8):688–706.

Knafo-Noam, A., D. Vertsberger, and S. Israel. 2018. Genetic and environmental contributions to children’s prosocial behavior: Brief review and new evidence from a reanalysis of experimental twin data. Current Opinion in Psychology 20:60–65.

Krol, K. M., M. Monakhov, P. S. Lai, R. P. Ebstein, and T. Grossmann. 2015. Genetic variation in CD38 and breastfeeding experience interact to impact infants’ attention to social eye cues. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112(39):E5434–E5442.

Lamm, C., J. Decety, and T. Singer. 2011. Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. NeuroImage 54(3):2492–2502.

Levy, J., A. Goldstein, and R. Feldman. 2019a. The neural development of empathy is sensitive to caregiving and early trauma. Nature Communications 10(1):1905.

Levy, J., K. Yirmiya, A. Goldstein, and R. Feldman. 2019b. The neural basis of empathy, empathic behavior, and trauma. Frontiers in Psychiatry 10:562.

Lockwood, P. L., M. Hamonet, S. H. Zhang, A. Ratnavel, F. U. Salmony, M. Husain, and M. A. J. Apps. 2017. Prosocial apathy for helping others when effort is required. Nature Human Behaviour 1(7):0131.

Lockwood, P. L., A. Abdurahman, A. S. Gabay, D. Drew, M. Tamm, M. Husain, and M. A. J. Apps. 2021. Aging increases prosocial motivation for effort. Psychological Science 32(5):668–681.

Lozada, M., P. D’Adamo, and N. Carro. 2014. Plasticity of altruistic behavior in children. Journal of Moral Education 43(1):75–88.

Lynch, S. F., S. Perlstein, C. Ordway, C. Jones, H. Lembcke, R. Waller, and N. J. Wagner. 2024. Parasympathetic nervous system functioning moderates the associations between callous–unemotional traits and emotion understanding difficulties in late childhood. Children 11(2):184.

Marsh, A. A. 2018. The neuroscience of empathy. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 19:110–115.

Meffert, H., V. Gazzola, J. A. den Boer, A. A. Bartel, and C. Keysers. 2013. Reduced spontaneous but relatively normal deliberate vicarious representations in psychopathy. Brain: A Journal of Neurology 136(Pt 8):2550–2562.

Milton, D. 2012. On the ontological status of autism: The double empathy problem. Disability and Society 27(6):883–887.

Office of the Surgeon General. 2023. Social media and youth mental health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory. Department of Health and Human Services.

Paradiso, E., V. Gazzola, and C. Keysers. 2021. Neural mechanisms necessary for empathy-related

phenomena across species. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 68:107–115.

Paz, Y., E. R. Perkins, O. Colins, S. Perlstein, N. J. Wagner, S. W. Hawes, A. Byrd, E. Viding, and R. Waller. 2024. Evaluating the sensitivity to threat and affiliative reward (STAR) model in relation to the development of conduct problems and callous–unemotional traits across early adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 65(10):1327–1339.

Perlstein, S., S. W. Hawes, A. L. Byrd, R. Barzilay, R. E. Gur, A. R. Laird, and R. Waller. 2024. Unique versus shared neural correlates of externalizing psychopathology in late childhood. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science 133(6):477–488.

Pitts, E. G., D. W. Curry, K. N. Hampshire, M. B. Young, and L. L. Howell. 2018. (±)-MDMA and its enantiomers: Potential therapeutic advantages of R (−)-MDMA. Psychopharmacology 235:377–392.

Plate, R. C., C. Jones, S. Zhao, M. W. Flum, J. Steinberg, G. Daley, N. Corbett, C. Neumann, and R. Waller. 2023. “But not the music”: Psychopathic traits and difficulties recognising and resonating with the emotion in music. Cognition and Emotion 37(4):748–762.

Powell, T., R. C. Plate, C. D. Miron, N. J. Wagner, and R. Waller. 2024. Callous–unemotional traits and emotion recognition difficulties: Do stimulus characteristics play a role? Child Psychiatry & Human Development 55(6):1453–1462.

Pratt, M., A. Goldstein, J. Levy, and R. Feldman. 2017. Maternal depression across the first years of life impacts the neural basis of empathy in preadolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 56:20–29.

Putnam, P. T., C.-C. J. Chu, N. A. Fagan, O. Dal Monte, and S. W. C. Chang. 2023. Dissociation of vicarious and experienced rewards by coupling frequency within the same neural pathway. Neuron 111(16):2513–2522.

Riva, F., C. Triscoli, C. Lamm, A. Carnaghi, and G. Silani. 2016. Emotional egocentricity bias across the life-span. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 8:74.

Rütgen, M., E.-M. Seidel, I. Riečansky, and C. Lamm. 2015a. Reduction of empathy for pain by placebo analgesia suggests functional equivalence of empathy and first-hand emotion experience. Journal of Neuroscience 35(23):8938–8947.

Rütgen, M., E.-M. Seidel, G. Silani, I. Riečanský, A. Hummer, C. Windischberger, P. Petrovic, and C. Lamm. 2015b. Placebo analgesia and its opioidergic regulation suggest that empathy for pain is grounded in self pain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112(41):E5638–E5646.

Rütgen, M., E.-M. Wirth, I. Riečanský, A. Hummer, C. Windischberger, P. Petrovic, G. Silani, and C. Lamm. 2021. Beyond sharing unpleasant affect—Evidence for pain-specific opioidergic modulation of empathy for pain. Cerebral Cortex 31(6):2773–2786.

Sarinopoulos, I., A. M. Hesson, C. Gordon, S. A. Lee, L. Wang, F. Dwamena, and R. C. Smith. 2013. Patient-centered interviewing is associated with decreased responses to painful stimuli: An initial fMRI study. Patient Education and Counseling 90(2):220–225.

Schwartz, L., J. Levy, Y. Shapira-Endevelt, A. Djalovski, O. Hayut, G. Dumas, and R. Feldman. 2022. Technologically-assisted communication attenuates inter-brain synchrony. NeuroImage 264:119677.

Schwartz, L., O. Hayut, J. Levy, I. Gordon, and R. Feldman. 2024. Sensitive infant care tunes a frontotemporal interbrain network in adolescence. Scientific Reports 14(1):22602.

Shapira-Endevelt, Y., A. Djalovsky, G. Dumas, and R. Feldman. 2021. Maternal chemosignals enhance infant-adult brain-to-brain synchrony. Science Advances 7(50):eabg6867.

Sheppard, E., D. Pillai, G. T. L. Wong, D. Ropar, and P. Mitchell. 2016. How easy is it to read the minds of people with autism spectrum disorder? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 46(4):1247–1254.

Stagg, S. D., R. Slavny, C. Hand, A. Cardoso, and P. Smith. 2014. Does facial expressivity count? How

typically developing children respond initially to children with autism. Autism 18(6):704–711.

Stevens, L., and J. Benjamin. 2018. The brain that longs to care for others: The current neuroscience of compassion. In L. Stevens and C. C. Woodruff (eds.), The Neuroscience of Empathy, Compassion, and Self-Compassion. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. Pp. 53–89.

Sun, F., Y. E. Wu, and W. Hong. 2025. A neural basis for prosocial behavior toward unresponsive individuals. Science 387(6736):eadq2679.

Vogels, E., R. Gelles-Watnick, and N. Massarat. 2022. Teens, Social Media, and Technology 2022. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/ (accessed on July 31, 2025).

Wager, T. D., and L. Y. Atlas. 2015. The neuroscience of placebo effects: Connecting context, learning, and health. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 16(7):403–418.

Wampold, B. E. 2015. How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry 14(3):270–277.

Warneken, F. 2018. How children solve the two challenges of cooperation. Annual Review of Psychology 69(1):205–229.

Warneken, F., and M. Tomasello. 2006. Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science 311(5765):1301–1303.

Warneken, F., and M. Tomasello. 2008. Extrinsic rewards undermine altruistic tendencies in 20-month-olds. Developmental Psychology 44(6):1785–1788.

Warneken, F., B. Hare, A. P. Melis, D. Hanus, and M. Tomasello. 2007. Spontaneous altruism by chimpanzees and young children. PLOS Biology 5(7):e184.

Wu, Y. E., J. Dang, L. Kingsbury, M. Zhang, F. Sun, R. K. Hu, and W. Hong. 2021. Neural control of affiliative touch in prosocial interaction. Nature 599(7884):262–267.

Zhang, M., Y. E. Wu, M. Jiang, and W. Hong. 2024. Cortical regulation of helping behaviour towards others in pain. Nature 626(7997):136–144.

DISCLAIMER This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Celia Ford, Sheena M. Posey Norris, and Eva Childers as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. The statements made are those of the rapporteurs or individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants, the planning committee, or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

REVIEWERS To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Jeanette Betancourt, Sesame Workshop; William C. Mobley, University of California San Diego; and Jessica Stern, Pomona College. Leslie Sim, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

PLANNING COMMITTEE Walter Koroshetz (Co-chair), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Gentry Patrick, University of California San Diego (Co-chair); Andrew Breeden, National Institute of Mental Health; Richard Davidson, University of Wisconsin–Madison and Center for Healthy Minds; Dawn Lavell-Harvard, Trent University; Robert Malenka, Stanford University; Abigail Marsh, Georgetown University; William C. Mobley, University of California San Diego; and Jessica Stern, Pomona College. The National Academies’ planning committees are solely responsible for organizing the workshop, identifying topics, and choosing speakers. Responsibility for the final content rests entirely with the rapporteurs and the National Academies.

SPONSORS This activity was supported by contracts between the National Academy of Sciences and Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc., Alzheimer’s Association; American Academy of Neurology; American Brain Coalition; American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; American Neurological Association; Boehringer Ingelheim; BrightFocus Foundation; California Institute for Regenerative Medicine; Cohen Veterans Bioscience; Dana Foundation; Department of Health and Human Services’ Department of Veterans Affairs (36C24E20C0009); Food and Drug Administration (R13FD005362); National Institutes of Health (75N98024F00001 [under Master Base HHSN263201800029I]) through the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Eye Institute, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute on Aging, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and NIH BRAIN Initiative; Eisai Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Foundation for the National Institutes of Health; Gatsby Charitable Foundation; Harmony Biosciences, Huo Family Foundation; Janssen Research & Development, LLC; Lundbeck Research USA; National Multiple Sclerosis Society; National Science Foundation (DBI-1839674); One Mind; Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group; Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative; and The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization or agency that provided support for the project.

STAFF (Health and Medicine Division) Sheena M. Posey Norris, Director, Forum on Neuroscience and Nervous System Disorders; Eva Childers, Program Officer (until July 2025), Kimberly Ogun, Senior Program Assistant (until July 2025), Christie Bell, Senior Finance Business Partner; Clare Stroud, Senior Director, Board on Health Sciences Policy (Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education) Daniel Weiss, Director, Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences.

SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2025. Unraveling the Neurobiology of Empathy and Compassion: Implications for Treatments for Brain Disorders and Human Well-Being: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/29238.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/44350_05-2025_unraveling-the-neurobiology-of-empathy-and-compassion-implications-for-treatments-for-brain-disorders-and-human-well-being-a-workshop.

|

Health and Medicine Division Copyright 2025 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. |

|