Vaccine Risk Monitoring and Evaluation at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2025)

Chapter: 3 Communications

3

Communications

PUBLIC HEALTH COMMUNICATIONS

Sound, evidence-based information is essential when it comes to fostering health care providers, patient, and public understanding and behavior about the benefits, risks, and value of public health recommendations. However, as the recent COVID pandemic made clear, multiple complexities and challenges exist in providing health and medical information, particularly if the goals include health care provider (HCP) endorsement of recommendations. Increased vaccine uptake to prevent disease is typically a goal of vaccination and related risk–benefit information and communication. It is also often assumed that achieving outcomes such as these with public health recommendations is primarily a matter of repeatedly and visibly providing “clear” (e.g., easily understood), “consistent” (e.g., uniform or unchanging), and “tailored” (e.g., customized) risk–benefit information and messages via “trusted” messengers using an array of traditional, social, and digital media channels and platforms (French et al., 2020).

While this assumption underlies fundamental concepts in health communication, its simplicity is deceptive. Much ultimately impacts public health entities’ and government agencies’ ability to act these concepts, and many factors influence the ability to deliver on these. Most public health programs and agencies, for instance, lack the financial and other resources needed to create and support communication programs that can continually and visibly reach multiple target subpopulations with customized information (Nowak et al., 2015). Furthermore, to the extent that information and recommendations do reach them, a host of factors, ranging from varying

levels of trust in those providing information and advice to differences in health, science, and reading literacy and ability to undertake recommended actions, significantly affect risk–benefit perceptions, health decision making, and behaviors.

In medicine and public health (as cases and outbreaks of COVID, Ebola, and Mpox viruses showed), it is particularly difficult to effectively communicate (e.g., provide clear, consistent, and easily understandable information) when the situation involves evolving scientific knowledge about new or emerging infectious disease; emergently authorized or newly licensed vaccines; false and misleading information; and evolving vaccination recommendations based on updated scientific knowledge. New and emerging infectious diseases bring uncertainties regarding transmission, severity and consequences of illness, and susceptibility (including which subpopulations and individuals are most vulnerable to infection, severe illness, and death) and differing projections regarding how fast and far infections and disease will spread. Those requiring recently authorized and licensed vaccines bring additional communication challenges related to the uncertainties regarding their efficacy and effectiveness (e.g., ability to protect against infection and/or severe disease and death), durability of protection, and safety, including immediate and short-term reactions to short- and long-term rare but serious adverse events (AEs). These challenges were compounded during the COVID pandemic by the use of Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs), a regulatory mechanism unfamiliar to much of the public, which made it more difficult to communicate evolving evidence and may have contributed to confusion or mistrust regarding the vaccines’ safety and approval status.

As an example, EUAs enable the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to permit the use of not yet licensed medical products, such as vaccines, when no adequate alternatives (e.g., a licensed vaccine) are available. FDA issued EUAs in December 2020 for the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna mRNA COVID vaccines based on clinical trial data that indicated the known and potential benefits outweighed the known and potential risks. Since EUAs had not been used to make new vaccines quickly and more widely available in a pandemic, this created additional communication challenges (Hammershaimb et al., 2022). As relatively few HCPs, people for whom the vaccines were recommended, and the broader public were familiar with the EUA process, much information regarding the safety, efficacy, and benefits needed to be continuously provided and updated to foster understanding of vaccination recommendations and address questions or concerns that had given rise to hesitancy. In addition, concerns about vaccines’ novelty (e.g., mRNA technology) and safety (e.g., immediate reactions, long-term side effects), trust in authorities (e.g., science, public health, elected officials, HCPs), misleading information, and beliefs about susceptibility and likelihood of severe illness heightened reluctance.

VACCINE AND VACCINATION-RELATED BENEFIT–RISK COMMUNICATION

The understanding of effects (both intended and unintended), and effectiveness of vaccine and vaccination-related benefit–risk communication are influenced by uncertainties involving the recommended vaccine(s) and the disease. First, how well recommendations, particularly ones involving newly developed and recommended vaccines, are perceived as individually beneficial is shaped by a host of considerations. These include perceptions regarding how well the vaccine can prevent or mitigate disease, particularly serious illness and death, and whether it may also reduce transmission (e.g., can it prevent infection and/or significantly impede human-to-human transmission); actual or expected efficacy in preventing infection and/or serious illness and protecting individuals and subpopulations most susceptible to severe illness; available evidence or data regarding immediate, short-term, and longer-term reactions (e.g., type and prevalence in the days after vaccination); and whether the vaccine is safer and more effective than alternatives (e.g., treatments, natural infection). Furthermore, perceptions of COVID vaccines and vaccination recommendations were also influenced by early and robust uptake by those at highest risk of harm, corroborated and uncorroborated reports of serious AEs (e.g., myocarditis in male young adults after mRNA vaccination), revisions and expansion of recommendations (e.g., to encompass more people, to include children) and vaccine refinements (e.g., to protect against new strains). As was seen during the pandemic, changing and broadening vaccination recommendations can engender concern, questions, doubts, and skepticism among individuals who have medical conditions that put them at elevated risk for severe illness and individuals in the broader population who may not perceive the virus to be a significant threat to their health and well-being and/or vaccination to be highly beneficial.

Published research before, during, and after the COVID public health emergency (PHE), including that involving routine recommended childhood and adult vaccines, has identified factors related to vaccine information and communication effects and effectiveness. First, one needs to identify the audience(s) (e.g., who needs to receive risk and benefit information) and articulate the objectives of the information and communication efforts with respect to that audience; that is, what is/are the desired outcomes? For vaccines, potential objectives include widespread or greater awareness and understanding of the benefits and risks, enhanced confidence and/or less hesitancy, or high or increased uptake among people for whom vaccination is recommended. Second, information alone is rarely sufficient for achieving communication and behavioral objectives. Simply providing more information, including that related to vaccine benefits or risks, rarely

changes perceptions or motivates uptake (Brewer et al., 2017; Dubé and MacDonald, 2017). Rather, the risk–benefit information needs to have an individual or subpopulation focus (e.g., take into account their knowledge, understanding, concerns, values, and beliefs), well describe the benefits, acknowledge and address barriers to vaccination (e.g., cost, access), and be aligned with people’s priorities and decision making (Brewer et al., 2017; Nowak et al., 2017). It has also been found that providing information about both benefits and risks increased trust and fostered vaccination intention, particularly when the HCP was perceived as empathetic and competent (Juanchich et al., 2024). Third, the source or provider of the risk–benefit information matters. Many published studies have documented that immunization providers (e.g., physicians, pediatricians, nurses) are the most trusted source of vaccine and vaccination information (Eller et al., 2019), with high trust associated with vaccination acceptance, including for COVID (Dudley et al., 2022; Warren et al., 2023). It has also been found, including during the pandemic, that media sources, particularly those used because they align with individuals’ worldview, affect trust in public health and medical recommendations, and in turn, vaccine-related beliefs and intentions/behavior (Dolman et al., 2023; Sarathchandra and Johnson-Leung, 2024).

People for whom vaccination is recommended are interested in its risks and harms, referred to as “side effects,” “adverse reactions,” or “adverse events.” The inconsistent and varied use of “risk” and “harm,” in concert with inconsistent and varied ways to categorize vaccine reactions, presents many communication challenges. “Risk,” for instance, can be defined in terms of probability (e.g., the estimated or evidence-based likelihood of a negative outcome), in terms of a known or possible bad outcome (e.g., a very negative or severe outcome being characterized as the risk), or as a synonym for harm (i.e., the bad or severe outcome itself).

Vaccine and immunization safety-related information and communication bring further challenges that affect content and messaging. Many of these challenges stem from the nature of immunization safety data and how they are presented:

- Individual versus population health. Challenges in extrapolating data from population-level benefits/harms to individual risk and vice versa.

- Time required to obtain and analyze valid and reliable data (e.g., medical records), including obtaining adequate sample size for reliable assessment. Rare AEs (e.g., 1 in 100,000) and long-term outcomes (like cancer and autoimmune disorders) require large datasets and time to detect patterns, making confirmation or exclusion of vaccine association difficult.

- The distinction between association and causation. Differentiating what is correlated with versus directly caused by vaccination requires robust study design and analysis.

- Attribution of causality at the individual level (difficulty in objectively showing or knowing whether vaccination prevented infection or severe illness or death). Counterfactuals (non-events) are almost impossible to directly observe for individuals.

- Heterogeneity of risks and benefit/harms balances. Other factors could be associated with, cause, and/or contribute to a significant vaccine reaction or AE (e.g., immune status, age, gender, ethnicity). Identifying and assessing contributing/associated factors takes robust, granular data.

- Moving target. Dynamic likelihood of contracting and/or experiencing severe illness is influenced by vaccination uptake in a community. Risk is not static and changes as more people are vaccinated and the pandemic evolves. Benefits also change.

- Vaccine safety data are complex, and communication is challenging. Data often include risks, ratios, confidence intervals, and statistical estimates, which require translation for public understanding. Many struggle to interpret small probabilities, understand relative versus absolute risk, or contextualize rare events (Reyna et al., 2009; Zipkin et al., 2014).

- Technical versus common language (e.g., side effects, AEs, adverse reactions). Jargon can confuse the public; there’s often a gap between scientific and layperson understanding.

- Consensus on findings does not guarantee acceptance or action. Even when data are valid/reliable (e.g., 1 in 25,000 AEs), experts, health professionals, and the public may interpret/recommend different actions. Decision making is influenced by not just data but perceived and personal values of risk, particularly regarding long-versus short-term risks.

- Speculation and misinformation. Unproven fears (e.g., vaccines cause cancer) can be hard to dispel, especially if confirming or disproving such risks is difficult due to the nature of the data.

VACCINE SAFETY COMMUNICATIONS AT THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION (CDC)

Effective vaccine safety communication depends on having scientifically robust safety data. While benefit–risk communication is essential for informing public health decisions, the role of the Immunization Safety Office (ISO) within CDC is focused specifically on identifying and communicating risks. ISO is charged with collecting, analyzing, and publicly

reporting vaccine safety data and identified signals. It does not develop clinical recommendations or policy or integrate benefits and risks; those activities are undertaken by ACIP, the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), and other CDC units. By maintaining this separation, ISO preserves the scientific independence of its safety assessments and ensures that its risk evaluations remain analytically distinct from policy development. Vaccine safety communications at CDC are crosscutting; different centers and programs use the information collected from the ISO vaccine safety systems to inform the populations that they serve. Daniel Jernigan, director of the National Center for Emerging Zoonotic and Infectious Diseases,1 explained to the committee that CDC’s vaccine safety communication efforts “are deliberate approaches designed to effectively share accurate, evidence-based information about safety while addressing concerns and building trust in the vaccine safety enterprise” (Jernigan, 2025). This involves being transparent, actively engaging with communities to exchange accurate information, tailoring messages to specific audiences, collaborating with trusted messengers, aligning communication with research and best practices, adapting based on ongoing insights, and combating misinformation (Jernigan, 2025). ISO’s statutory remit is to quantify and communicate vaccine-safety risks, not to determine vaccination policy. Public-facing ISO materials therefore focus on reporting numeric risk estimates with appropriate confidence intervals and describing analytic methods, while directing readers to NCIRD and ACIP channels for interpretations that weigh those risks against benefits.2 Box 3-1 contains examples of CDC’s vaccine safety communication efforts, including collaboration between NCIRD and ISO.

CDC targets four key audiences regarding vaccine safety: U.S. federal government agencies, advisory committees, partners and HCPs, and the public. Figure 3-1 contains the various types of communications with each key audience. Federal agencies that monitor vaccine safety signals remain in constant communication, particularly during a PHE or the introduction of a new vaccine. These agencies also hold formal briefings with their advisory committees to coordinate responses. At ACIP meetings—outlined in Chapter 2—ISO staff, vaccine-specific working groups, and—during the PHE—the Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group (VaST) presented findings, which become part of the public record.

To inform HCPs, CDC conducts clinician outreach and communication activity (COCA) calls—subject-matter experts share updates on relevant clinical and public health topics (CDC, 2025a). CDC engages the public through its website, where it posts vaccine-safety-related content. The committee’s evaluation of these webpages appears later in this chapter.

___________________

1 As of August 28, 2025, Dr. Daniel Jernigan is no longer the director of CDC’s NCEZID.

2 Public Health Service Act, Section 2102, 42nd U.S Congress.

BOX 3-1

CDC Vaccine Safety Communication Efforts

- - Vaccine Information Statement

- - Advisory Committees (e.g., Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices)

- - Vaccine guidance for health care providers (HCPs)

- - Domestic HCP and partner training

- - Global HCP and partner training

- - Emergency response

- - Support to state and local health departments

- - Responses to public inquiries

- - Travelers’ vaccine guidance

- - Resources for specific populations (e.g., older adults)

- - Immigrant and refugee health guidance

SOURCE: Prepared by the committee and adapted from the presentation by Daniel Jernigan, 2025.

State and territorial public health agencies (SPHAs) were not always treated as core audiences for safety communications during the COVID response. Yet their role as on-the-ground public health implementers requires early, routine, and bidirectional engagement. Conversations with SPHAs should occur on a regular cadence—including just-in-time briefings before major announcements or policy changes—to enable them to act as effective extensions of CDC communication. The absence of consistent coordination early in the pandemic created avoidable confusion and hindered message alignment at the community level (Fraser, 2021).

COMMUNICATIONS DURING THE PHE

During summer 2020, CDC developed a COVID vaccine safety communications strategy in anticipation of vaccine availability (see Figure 3-2) alongside the vaccine development, testing, and authorization timeline; it included identifying key audiences, messages, tactics, trusted messengers, and dissemination channels. Safety monitoring and communication of findings began once vaccines received EUAs and ACIP recommended them (Jernigan, 2025).

Although CDC has various ways of communicating with its partners, not all of them are publicly available or easily accessible. Table 3-1 contains

NOTE: AAP = American Academy of Pediatrics; CBO = community-based organization; CDC ACIP = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; COCA = Clinician Outreach and Communication Activity; DoD = Department of Defense; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; FDA VRBPAC = Food and Drug Administration Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee; HCP = health care provider; HHS NVAC = Department of Health and Human Services National Vaccine Advisory Committee; HRSA ACCV = Health Resources and Services Administration Advisory Committee on Childhood Vaccines; VA = Department of Veterans Affairs; WHO GACVS = World Health Organization Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety.

SOURCE: Prepared by the committee and adapted from the presentation by Daniel Jernigan, 2025.

NOTE: *Signal: a statistical association found in vaccine safety monitoring; it does not mean there is a true association and requires investigation and evaluation. ACIP = Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; VRBPAC = Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee.

SOURCE: Prepared by the committee and adapted from the presentation by Daniel Jernigan, 2025.

TABLE 3-1 Publicly Available CDC Vaccine Safety Communications

| Meetings/Webinars | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | Purpose | Primary Audience | Regular Schedule | Total During PHE |

| ACIP Meetings | Convene medical and public health experts who develop recommendations on U.S. use of vaccines | Medical and public health experts, vaccine safety researchers | 3x/year | 27 |

| COCA Calls | Address emerging public health threats, provide updates on ongoing health issues, and share important clinical guidance | Clinicians | Varied, as needed | 23 webinars specific to COVID vaccine safety |

| CDC Publications | ||||

| MMWR | Be the primary vehicle for scientific publication of timely, reliable, authoritative, accurate, objective, and useful public health information and recommendations | Clinicians, public health practitioners, epidemiologists and other scientists, researchers, educators, and laboratorians | Weekly | 43 publications specific to COVID vaccine safety monitoring |

| Web-Based Communications | ||||

| Webpages | Provide transparent, evidence-based, information on vaccine safety and safety signals | Health care professionals, public health professionals, the public | Ad hoc | Regularly updated |

NOTES: ACIP = Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; COCA = Clinician Outreach and Communication Activity; MMWR = Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; PHE = public health emergency. CDC publications other than MMWRs are in Appendix E.

SOURCES: CDC, 2025a,b,c.

publicly available CDC vaccine safety communications, their purpose, primary audience, regular schedule, and total number produced during the PHE, if known. ACIP meetings, COCA calls, and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports (MMWRs) regarding vaccine risk, harms, and safety monitoring increased significantly. ISO peer-reviewed publications other than MMWRs are discussed in Chapter 2, and a catalog is in Appendix E. During his presentation to the committee, Jernigan highlighted his partner newsletters as an important channel (over 152,000 subscribers received them from December 2020 to May 2023) (Jernigan, 2025), but these are not publicly available, and the committee was not provided with samples to review. Additionally, CDC shared vaccine safety information on social media platforms and received approximately 101 million views across Instagram, X, Facebook, and LinkedIn during the same time frame. Webpages were updated as additional information about vaccine safety and harms was identified from safety signals, such as thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS), and social listening activities (Jernigan, 2025). CDC also used a variety of web sources, including social media platforms, online forums, blogs, and polls, to publish State of COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence Insights Reports.

ISO’s communication remit has been scientific, not consumer facing—publishing safety analyses in peer-reviewed journals, presenting data to ACIP, and issuing MMWR summaries. CDC itself notes that ISO “regularly shares vaccine safety monitoring findings through presentations at scientific meetings and publication in peer-reviewed journals,” while ACIP converts those data into vaccination policy guidance. After the U.S. COVID vaccines were authorized and recommended for use in December 2020, ISO staff responded to safety concerns raised by HCPs, public health officials, and the public (Miller et al., 2023). Inquiries were received primarily through CDC-INFO (a telephone and email system that responds to general questions for CDC) and CDC’s National Immunization Program (an email service that responds to general questions about immunization); inquiries that require vaccine safety expertise are triaged to the ISO vaccine safety inquiry response program, staffed by nurses, physicians, epidemiologists, and other health scientists with expertise in vaccine safety (Miller et al., 2023). Between December 1, 2020, and August 31, 2022, ISO received 1,655 inquiries about COVID vaccine safety, with the most common about deaths after vaccination (160, 10 percent), myocarditis and related topics (153, 9 percent); pregnancy and reproductive health outcomes (123, 7 percent); understanding or interpreting data from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) (111, 7 percent); and TTS and related questions about blood clotting (95, 6 percent) (Miller et al., 2023).

The COVID response was agencywide, established at the direction of the CDC director, and part of a larger multiagency incident command structure within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

TABLE 3-2 CDC COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Task Force Teams

| COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Team (VST) |

|---|

|

| COVID-19 Vaccine Communications Team |

|

NOTES: DHQP = Division of Healthcare Quality and Promotion; FTE = full-time employee; ISO = Immunization Safety Office; VST = Vaccine Safety Team. The Vaccine Task Force included new systems and activities, including V-safe, COVID-19 Vaccine Pregnancy Registry, follow-up of long-term effects of myocarditis, long-term care facility monitoring, and development of ACIP COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Working Group (VaST) (Su, 2024).

SOURCE: Prepared by the committee and adapted from the presentation by Daniel Jernigan, 2025.

and overall federal government. CDC staff were deployed or temporarily assigned to assist with response efforts. Various task forces were formed as part of the scientific response section, including epidemiology and surveillance, modeling, and the Vaccine Task Force, which contained the COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Team (VST) and COVID-19 Vaccine Communications Team (established during summer 2020, Figure 3-2). ISO staff, in addition to CDC staff from NCIRD—and other parts of the agency based on their skills and knowledge—were deployed to the COVID-19 VST.

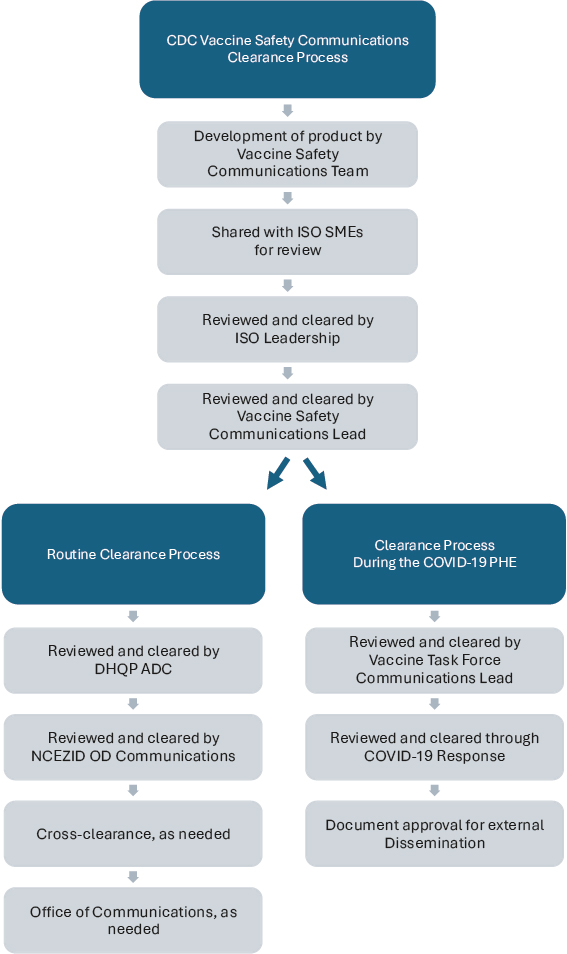

The vaccine safety communication products clearance process is similar during emergency and routine times, with a few key differences (Jernigan, 2025) (see Figure 3-3). During nonemergency periods (also referred to as “routine”), the level of clearance and need for cross-clearance within CDC depends on the product; ISO vaccine safety communications—focused on risk and harms—are often combined with vaccine use and recommendation communications from centers within CDC, such as NCIRD, in the context of risks versus benefits. During the PHE, the CDC joint information center was the central point of information coordination and emergency risk communication; its functions included centralizing and developing a strategy for response communications, staffing, engaging with clinician and nonclinician partners, response clearance, and research and evaluation (Jernigan, 2025). Jernigan explained that ISO’s mandate is to identify and communicate

NOTE: ADC = Associate Director of Communications; DHQP = Division of Healthcare Quality and Promotion; ISO = Immunization Safety Office; NCEZID = National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases; OD = Office of the Director; SME = subject-matter expert.

SOURCE: Prepared by the committee and adapted from the presentation by Daniel Jernigan, 2025.

potential risks from vaccines—such as signals detected through its safety systems—without engaging in vaccine promotion. ISO aims to present this information clearly, in ways that help individuals understand what a signal means and how it fits into broader public health considerations. However, during the pandemic, risk communication products were frequently combined with benefit-emphasizing messages. While this framing may aid decision making, it also risks blurring ISO’s independent scientific role. Future communications about risk signals should explicitly distinguish between ISO’s role in risk identification and the policy or promotional messaging issued by CDC or HHS. ISO should retain authority to publish its findings—even when benefits are not concurrently presented—using standardized templates and dedicated platforms that clearly demarcate scientific risk assessment from policy recommendation. As Jernigan noted, “there is a risk of harm from getting a vaccine, but in general, these licensed or approved vaccines have demonstrated that risk from that vaccine is outweighed by the benefits of the vaccine by preventing disease” (Jernigan, 2025).

ASSESSMENT OF CDC VACCINE RISK COMMUNICATIONS

The Statement of Task specified that the committee would evaluate CDC external communications about its safety monitoring systems, the findings of COVID vaccine safety monitoring, and vaccination and clinical guidance recommendations to HCPs and public health officials (“technical” audiences) and the public. After careful consideration, the committee proceeded to do an in-depth review of webpages, exclusively; they are publicly available and the main method of communication to all three priority audiences.

The committee evaluated CDC webpages that fell into at least one of three categories:

- Safety system related (Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment [CISA], VAERS, Vaccine Safety Datalink [VSD], V-safe),

- Safety signal related (e.g., myocarditis), and

- General vaccine safety (e.g., risk of AEs).

As a result of its Moving Forward initiative, CDC launched Clean Slate, to “overhaul the CDC.gov website and streamline content by more than 60 percent so that people will be better able to find the information they’re looking for to protect their health” (CDC, 2024a). Many webpages that were active during the PHE were archived; new webpages were created, though many of them contained content from the archived ones. The committee reviewed all webpages (archived or active) that were safety system

related, about general vaccine safety, and regarding AEs and safety signals after receiving a COVID vaccine.

In 2015, the U.S. Web Design System was established from executive initiatives as a collaboration between the U.S. Digital Service and 18F3 (Miller, 2025), a digital services agency within the General Services Administration (GSA, 2015). The goal is to provide a set of common visual and technical elements for federal websites, aiming to offer high-quality, consistent digital experiences. Due to this ongoing improvement initiative, the committee did not evaluate CDC webpages for any standards or elements under its purview.4

Additionally, the committee hosted a public listening session to gather stakeholder input on CDC’s vaccine safety research and communications. During this 2-hour virtual session, preregistered attendees were given up to 3 minutes each to share their perspectives and recommendations (see Box 1-4 for a summary of salient points). It invited public comment on ways to improve CDC’s research—both during PHEs and in routine vaccination contexts—and make information about vaccine safety and risks more accessible and understandable. Topics included criteria for evaluating potential harms, the timing and communication of emerging safety signals, and strategies to strengthen public confidence in vaccines.

In parallel, the committee contracted with an independent third party to conduct confidential key informant interviews. These interviews engaged a diverse group of stakeholders to obtain in-depth insights on CDC’s current approaches and identify areas for improvement in vaccine safety monitoring and communication (see Appendix C).

Approach

The committee adapted its approach to webpage evaluation from specific guidelines for communicators described by Covello (2021): for creating clear technical information, delivering clear technical information, and enhancing the clarity of technical information. The following principles of effective communication were considered:

___________________

3 On March 1, 2025, 18F was eliminated as part of a federal reorganization (Miller, 2025).

4 As of September 26, 2024, federal website standards are available at standards.digital.gov. Federal agencies are required to comply with these standards per the 21st Century Integrated Digital Experience Act (IDEA) (2018), which made federal government website modernization a legal requirement. The standards are developed through a rigorous and iterative process involving federal agencies, the public, and other relevant groups. Each standard includes acceptance criteria that specify what elements must be present to be compliant. The status of each standard reflects its stage in the development process: research, draft, pending, or required (GSA, n.d.a,b).

- Avoids or appropriately uses technical or bureaucratic jargon, acronyms, and abbreviations;

- Uses culturally relevant, meaningful and linguistically appropriate language (words in the language they understand);

- Defines new or key terms so the target audience can understand them;

- Uses brief and clear sentences, particularly when defining new terms;

- Summarizes key information and is prominently placed;

- Provides focused message points;

- Provides complex information in tiers or layers of information that increase gradually in complexity; and

- Clearly communicates the science upon which the information is based.

The committee also assessed whether a webpage contained appropriate and meaningful visuals/graphics that enhance the text.

As mentioned, ISO’s risk communication is often interwoven into broader vaccine safety messaging—including risk of harms in the context of benefits—and this was a common observation for the committee as it reviewed webpages that did not exclusively include information about risk and harms. As a result, the evaluation assesses risk communications regardless of authorship. However, webpages regarding ISO’s vaccine safety systems—CISA, VAERS, VSD, and V-safe—are strictly within its purview and assumed authorship.

After its assessment, the committee found that its observations fell primarily into the guiding principles (discussed in Chapter 1) of relevance (communication activities meaningfully addressing the needs of health professionals, policy makers, and the public), credibility (the production and dissemination of scientifically sound information about vaccine risks), and independence (communications are free from undue internal or external influence).

Assumption of a Baseline Level of Technical Knowledge

The committee’s assessment revealed that many vaccine safety webpages present information in a way that assumes readers have a certain level of technical background, though that assumption should not be applied universally. Technical audiences are not experts in communicating risk (Jones et al., 2025) and would benefit from using plain language with more accessible explanations of technical concepts regardless of audience. For example, a webpage that describes CDC’s vaccine safety monitoring program (CDC, 2024b) does not clearly explain what vaccine safety monitoring is,

and a page that describes how it works (CDC, 2024c) assumes knowledge of vaccine safety science.

Inconsistency and Discrepancy in Definitions

Key terms, such as “risk,” “adverse events,” “adverse events of special interest,” “side effects,” “complex safety questions,” “safety signal,” and “safety concern” are not defined at all, used inconsistently across content, or used in ways that could be misinterpreted without context. For example, “vaccine adverse event” is used differently across contexts, contributing to public confusion. In VAERS, it refers to any health problem occurring after vaccination, whether or not it is causally related. However, the name “Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System” can imply to the public that all reported events are caused by vaccines. Public-facing materials should more clearly explain that VAERS accepts all reports to ensure early detection of rare issues—not because all events are vaccine related. Similarly, risk language used across CDC materials varied in specificity. Some risks (e.g., TTS ≈ 4 per million doses) were numerically defined, while others (e.g., myocarditis) were described qualitatively. Standardizing terminology and ensuring consistent risk quantification would improve clarity (CDC, 2025d). Moreover, safety monitoring during the pandemic was described as using established systems, but one of the extensively used systems (V-safe) was created during the PHE (CDC, 2024d).

Lack of Accessible Information

The committee found a lack of accessible information regarding the science and research methods behind the processes, systems, and conclusions related to potential vaccine-related harms. Some webpages provided appropriate safety information to technical audiences but could have included more substantive information that clearly explained the underlying science. Some cases had limited context or explanation for certain statements, such as “most intensive safety monitoring in U.S. history” (CDC, 2025e). This claim requires supporting evidence, particularly considering the public’s resistance to blanket statements. The VSD webpage assumes the audience has familiarity with public health and analytic methods without necessarily explaining them (CDC, 2024e). Additionally, several webpages link to technical articles regarding vaccine safety on PubMed; this may lead some members of the public to disengage and may have restricted access if articles were behind a paywall.

Organization and Structure

The organization and structure of vaccine safety webpages presented difficulties in navigation functionality. A structural observation in the committee’s assessment highlighted challenges in the design: Webpages did not clearly indicate whether the content was intended for a technical or lay audience.5 This lack of clarity made navigation especially difficult, particularly when pages were linked to others that may have targeted different audiences. Numerous webpages also contain similar content, which can hinder users’ ability to navigate effectively and recall key information.

Broader Context of Information About Potential Vaccine-Related Harmful Outcomes

As discussed in Chapter 1, ISO’s function is to provide information to health professionals, policy makers, and the public regarding vaccine safety (see Box 1-3), focused on vaccine risks. As mentioned, the committee observed that vaccine safety information is often presented alongside the benefits to help contextualize potential risks and harms. As a result, some of the committee’s observations are outside the purview of ISO but would aid CDC in providing effective communication about potential vaccine-related health outcomes to necessary audiences. Public health communication often relies on simplified messaging to promote clarity and action. However, this approach can obscure the nuance inherent in vaccine safety data, particularly during novel disease outbreaks where scientific understanding evolves rapidly. In such cases, changes in guidance should be seen as not institutional failure but rather a reflection of transparency, new evidence, and real-time learning. Communicating this iterative nature of science—while preserving public trust—is a persistent challenge for vaccine safety offices and communicators alike (Fischhoff et al., 2014, 2019; Han et al., 2021). To address this, ongoing communication research is necessary to understand how best to communicate vaccine safety information within this dynamic environment. Ultimately, attending to the areas outlined next can aid in building public trust while navigating the nuanced landscape of vaccine safety data.

___________________

5 Before May 15, 2025, webpage content did not consistently indicate whether it was intended for a technical or lay audience. After this date, the committee started to observe the addition of clarifying labels, such as “For Everyone” or “For Healthcare Professionals,” to indicate general audience orientation.

Tailored Information

Vaccine safety communication efforts are intentionally designed to effectively share evidence-based information, address concerns, and build trust (Jernigan, 2025). Collaborating with trusted messengers and key opinion leaders was a core strategy for effective public engagement during the pandemic. Jernigan (2025) explained that these messengers can be religious and/or community leaders and partners, individuals proficient in various languages who can ensure messages are received accurately and appropriately, and HCPs. The committee found very few webpages geared toward providing these trusted lay messengers with information that would equip them with the knowledge, skills, and tools necessary to communicate effectively about vaccine risks. This is especially true for historically underserved and underrepresented groups. While CDC emphasized the role of national messengers and partner organizations, state and local health departments were often better positioned to engage community leaders and respond in real time. State and local agencies actively pushed vaccine-related information through trusted local figures, including clergy, teachers, and neighborhood organizations. These efforts, rooted in community relationships, sometimes outpaced or compensated for delayed or generic federal communications. Future strategies should more clearly define and support the complementary roles of CDC and state agencies in messaging. Additionally, ensuring that webpages are tailored to not only a broader array of trusted messengers but also lay audiences would improve the effectiveness of evidence-based communication and enhance credibility.

Tailoring may take one of two forms: (a) risk information for a specific demographic and (b) messages that are culturally responsive to communities’ specific concerns. Efforts to tailor information were hindered by incomplete demographic data. For example, race and ethnicity data were missing from more than half of the vaccine records reported to some states, limiting the ability to target communication strategies to disproportionately affected communities or evaluate equity in outreach (CDC, 2021a). Addressing these data gaps is essential for ensuring that vaccine safety communication is inclusive, equitable, and evidence based.

It was unclear to the committee exactly what efforts were taken to be culturally responsive. Moving forward, integrating community-engaged findings and feedback as part of the communications process will help ensure the relevance of vaccine safety information.

Communication with the Public

CDC emphasized the importance of understanding what the community is hearing or saying. Especially during the PHE, it used social listening,

defined by Stewart and Arnold (2017) as “an active process of attending to, observing, interpreting, and responding to a variety of stimuli through mediated, electronic, and social channels” and published State of Vaccine Confidence Insights Reports to share what it observed with partners and the public. Information on CDC’s Myths & Facts About COVID-19 Vaccines webpage may have also come from social listening, although it is not explicitly stated (CDC, 2024f). However, social listening is not necessarily bidirectional communication. The committee is particularly unclear about the processes to ensure the insights gained are incorporated into communication materials (and if ISO used any inquiries described by Miller et al. (2023) to create such materials, discussed earlier in the chapter).

Throughout the pandemic, social media platforms, visual dashboards, and scientific journals were used to disseminate vaccine safety findings. However, most communications remained one directional, lacking mechanisms for real-time, bidirectional engagement with the public. To meet evolving communication expectations, CDC and ISO should explore new formats—such as interactive explainers, Q&A forums, and multimedia summaries—to convey complex vaccine safety data. These tools should be accessible on mobile platforms and optimized for different audience types. Traditional methods, like the MMWR, remain indispensable for professional audiences, but they are poorly suited for public understanding without translation. Innovative formats should be used not to replace but to complement core scientific communications.

The process for public comment on ACIP recommendations is governed by federal requirements (Federal Advisory Committee Act and Office of Management and Budget directives) to ensure transparency and public participation in decision making (GSA, 2025). ACIP meetings must be announced in the Federal Register at least 15 calendar days in advance and include meeting dates and times, topics to be discussed, and instructions for the public to register for oral comment or submit written comments. The committee performed a high-level review of written public comments submitted through the Federal Register before the standing February 2021 (CDC, 2021b), June 2021 (CDC, 2021c,d), and October 2021 (CDC, 2021e) ACIP meetings.6 Given the volume of comments related to vaccine risks and harms, the committee believes this may be a valuable avenue for ISO to explore—in not only gathering feedback from diverse audiences but also incorporating it into communication materials.

A critical but often underarticulated communication vulnerability lies in blurring ISO’s mission—focused on vaccine risk surveillance—with broader immunization promotion efforts. When communications about

___________________

6 These were the three scheduled meetings in 2021. The first COVID vaccine was authorized for emergency use on December 11, 2020.

ISO’s findings are closely coupled with or filtered through policy advocacy or vaccine promotion, it may unintentionally undermine the perceived independence of ISO’s safety monitoring role, particularly among individuals already predisposed to skepticism (Larson et al., 2014; Quinn et al., 2019). This dynamic can erode public trust in vaccine safety assessments, even when the underlying science is rigorous and the intent transparent. To safeguard trust and reinforce ISO’s credibility, it ought to be equipped with independent communication channels specifically dedicated to sharing its safety surveillance processes, evaluation criteria, and findings—separate from CDC’s promotional or policy-facing content. Clearly delineated, plain-language communications about what ISO does and how it does it would not only improve transparency but also help insulate its work from misperceptions of bias or agenda alignment.

CONCLUSION

The COVID PHE compelled CDC’s ISO to release vaccine risk information at a speed and scale never before required. ISO and its communication partners produced a vast body of technical content—on safety signals, monitoring systems, and analytic methods—that clinicians and health officials found indispensable for day-to-day decision making. Yet the committee observed that this content was usually embedded in broader CDC messaging and cleared through processes that emphasized vaccine uptake goals, blurring ISO’s independent scientific voice and, at times, limiting public visibility into how safety findings were generated and released. The committee used the five guiding principles to frame its analysis and recommendations, and its conclusion on ISO’s communication activities is organized according to those same principles.

Relevance: ISO’s webpages often assume professional familiarity with epidemiologic concepts, provide few cues about their intended audience, and nest critical definitions several clicks deep. Navigation is further hampered by multiple pages that repeat similar content or mix lay and technical language. To make future outputs meaningfully useful, ISO ought to segment products by audience, layer detail, and ensure that trusted messengers—especially those serving underserved communities—can quickly locate plain-language explanations that match what they hear through social listening and public comment channels.

Credibility: The underlying science is sound, but inconsistent terminology (“adverse event,” “safety signal,” “risk”) and nonstandardized risk metrics impede interpretation and increase the danger of misunderstanding, incorrect interpretation, and misuse of data. Publishing study protocols, explicitly defining key terms, and adopting a single risk-reporting template

across all AEs would let external reviewers verify methods and enhance public trust.

Data stewardship: ISO relies on individuals and health care systems that contribute sensitive data to VAERS, VSD, V-safe, and CISA. The committee saw little public-facing material that explains how privacy is safeguarded or how outside researchers can request controlled access to deidentified data—an omission that may undercut the social license to operate these systems. Making stewardship practices and data-sharing pathways more transparent would honor participants and widen the scientific lens on vaccine safety.

Continuous improvement and innovation: ISO rapidly adopted social media “listening,” new visual templates, and the U.S. Web Design System during the pandemic, demonstrating an ability to modernize. Embedding usability metrics, readability goals, and routine user testing and input into the forthcoming strategic plan will institutionalize that agility, ensuring that communications evolve alongside novel vaccine platforms, new data streams, an evolving information environment, and emerging best practices in risk messaging.

Independence: The most consistent theme in public comments and key informant interviews was the erosion of trust that occurs when safety findings appear filtered through benefit-promotion lenses. ISO content is still cross-cleared with offices whose mission is to increase vaccine uptake, and webpages frequently couple risk estimates with exhortations to vaccinate. To protect scientific integrity, CDC ought to firewall ISO communications from policy and promotional channels, give ISO scientists final authority to post risk analyses—even when benefits are not simultaneously discussed—and brand those postings on a distinct ISO platform. Doing so will clarify roles, shorten time to publication, and reassure skeptical audiences that safety evidence is reported fully and without spin. To advance transparency and structural clarity, ISO’s communications should be operationally insulated from benefit–risk determinations and promotional content. During the pandemic, publication delays sometimes arose due to clearance processes that required cross-office approvals. Streamlining ISO’s ability to independently publish risk findings—backed by transparent data and standardized protocols—would bolster public trust and speed the translation of emerging signals into policy deliberation.

Despite the strength and coordination of the underlying vaccine safety infrastructure, the committee finds that communication about how the system functioned—and safety findings were evaluated and disseminated—was insufficiently transparent. Even among internal stakeholders (Edwards et al., 2025), it was not always clear how risk assessments were communicated to the public or which channels were used to share evolving findings. For the general public, the structure and rigor of the vaccine safety monitoring, evaluation, and communication were rarely explained coherently and accessibly. This lack of transparency weakened confidence in the system

and hindered appreciation of the extensive behind-the-scenes efforts to monitor and ensure vaccine safety. Greater clarity about the surveillance systems, evaluation processes, and decision-making criteria—particularly during emergencies—should be a standing priority.

Finally, the committee acknowledges the need for coherent and coordinated communication in a landscape that includes multiple surveillance systems, external collaborators, and a rapid pace of discovery. During the COVID response, ISO and its partners operated under intense scrutiny and pressure to deliver timely findings. In this context, the need to align messages across agencies and programs sometimes conflicted with the expectations of scientific independence held by non-government investigators. The federal clearance process, while intended to promote message consistency, occasionally led to concerns about the suppression or delay of legitimate scientific findings. Balancing the imperative for communication discipline with the values of transparency and investigator autonomy will be critical for public trust. Establishing clear, publicly available criteria for when and how findings are communicated—especially for research conducted in collaboration with academic or non-federal institutions—can help strike this balance.

ISO’s ability to detect and explain vaccine risks is crucial for national and global immunization programs. Strengthening relevance through audience-specific content, enhancing credibility with standardized methods, demonstrating respect for data contributors, institutionalizing continuous improvement, and, critically, asserting operational independence will make ISO the definitive, trusted voice on vaccine risk science—both in routine times and during the next public health crisis.

REFERENCES

Brewer, N. T., G. B. Chapman, A. J. Rothman, J. Leask, and A. Kempe. 2017. Increasing vaccination: Putting psychological science into action. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 18(3):149–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100618760521.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2021a. Demographic characteristics of persons vaccinated during the first month of the COVID-19 vaccination program—United States, December 14, 2020–January 14, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7005e1.htm (accessed August 6, 2025).

CDC. 2021b. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01/27/2021-01737/advisory-committee-on-immunization-practices-acip (accessed August 26, 2025).

CDC. 2021c. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) June 23–24 2021. https://www.regulations.gov/document/CDC-2021-0034-0001 (accessed June 16, 2025).

CDC. 2021d. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP); Amended Notice of Meeting. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/07/02/2021-14203/advisory-committee-on-immunization-practices-acip-amended-notice-of-meeting (accessed June 16, 2025).

CDC. 2021e. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP); Amended Notice of Meeting. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/11/08/2021-24320/advisory-committee-on-immunization-practices-acip-amended-notice-of-meeting (accessed September 10, 2025).

CDC. 2024a. CDC moving forward. https://www.cdc.gov/about/cdc-moving-forward.html (accessed April 16, 2025).

CDC. 2024b. About CDC’s Vaccine Safety Monitoring Program. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety-systems/about/cdc-monitoring-program.html (accessed April 24, 2025).

CDC. 2024c. How vaccine safety monitoring works. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety-systems/about/monitoring.html (accessed April 24, 2025).

CDC. 2024d. About V-safe. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety-systems/v-safe/index.html (accessed September 10, 2025).

CDC. 2024e. Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety-systems/vsd/ (accessed August, 7, 2025).

CDC. 2024f. Myths & facts about COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/vaccines/myths-facts.html (accessed April 24, 2025).

CDC. 2025a. COCA calls. https://www.cdc.gov/coca/hcp/trainings/index.html (accessed April 16, 2025).

CDC. 2025b. About the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) series. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/about.html (accessed August 6, 2025).

CDC. 2025c. ACIP meeting information. https://www.cdc.gov/acip/meetings/index.html (accessed August 8, 2025).

CDC. 2025d. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine safety. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety/vaccines/covid-19.html (accessed September 10, 2025).

CDC. 2025e. COVID-19 vaccine safety reporting systems. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety-systems/monitoring/covid-19.html (accessed September 10, 2025).

Covello, V. T. 2021. Communicating in risk, crisis, and high stress situations: Evidence-based strategies and practice. Piscataway, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Dolman, A. J., T. Fraser, C. Panagopoulos, D. P. Aldrich, and D. Kim. 2023. Opposing views: Associations of political polarization, political party affiliation, and social trust with COVID-19 vaccination intent and receipt. Journal of Public Health 45(1):36–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab401.

Dubé, E., and N. E. MacDonald. 2017. Vaccination resilience: Building and sustaining confidence in and demand for vaccination. Vaccine 35(32):3907–3909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.015.

Dudley, M. Z., B. Schwartz, J. Brewer, L. Kan, R. Bernier, J. E. Gerber, H. B. Ni, T. M. Proveaux, R. N. Rimal, and D. A. Salmon. 2022. COVID-19 vaccination status, attitudes, and values among U.S. adults in September 2021. Journal of Clinical Medicine 11(13):3734. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11133734.

Edwards, J., N. Osuoha, J. Maizel, R. Neenan, N. Page, P. Resichmann, and B. Slotman. 2025. Key informant interviews findings report. Rockville, MD: Westat.

Eller, N. M., N. B. Henrikson, and D. J. Opel. 2019. Vaccine information sources and parental trust in their child’s health care provider. Health Education & Behavior 46(3):445–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198118819716.

Fischhoff, B. 2019. Evaluating science communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(16):7670–7675. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1805863115.

Fischhoff, B., and A. L. Davis. 2014. Communicating scientific uncertainty. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(supplement_4):13664–13667. https://doi.org/110.1073/pnas.1317504111.

Fraser, M. 2023. ASTHO response to Senate help request for information on CDC reform October 20, 2023.

French, J., S. Deshpande, W. Evans, and R. Obregon. 2020. Key guidelines in developing a pre-emptive COVID-19 vaccination uptake promotion strategy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(16):5893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165893.

GSA (General Services. Administration). n.d.a. Federal website standards: About. https://standards.digital.gov/about/ (accessed April 12, 2025).

GSA. n.d.b. Federal website standards: Standards. https://standards.digital.gov/standards/ (accessed April 12, 2025).

GSA. 2015. Introducing the U.S. Web Design Standards. https://18f.gsa.gov/2015/09/28/webdesign-standards/ (archived on February 27, 2025, using the Wayback Machine: https://web.archive.org/web/20250227225756/).

GSA. 2025. Federal advisory committee act (FACA) management overview. https://www.gsa.gov/policy-regulations/policy/federal-advisory-committee-management (accessed April 24, 2025).

Hammershaimb, E. A., J. D. Campbell, and S. T. O’Leary. 2022. Coronavirus disease-2019 vaccine hesitancy. Pediatric Clinics of North America 70(2):243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2022.12.001.

Han, P. K., E. Scharnetzki, A. M. Scherer, A. Thorpe, C. Lary, L. B. Waterston, A. Fagerlin, and N. F. Dieckmann. 2021. Communicating scientific uncertainty about the COVID-19 pandemic: Online experimental study of an uncertainty-normalizing strategy. Journal of Medical Internet Research 23(4):e2783210.2196/27832.

Jernigan, D. 2025. CDC COVID-19 vaccine safety risk communications. Presentation to the Committee to Review the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Research and Communications, Washington, DC, January 10, 2025.

Jones, M., S. Ratzan, and R. Tuckson. 2025. Challenges and opportunities for research and communication about vaccine safety. Washington, DC, February 25.

Juanchich, M., C. M. Oakley, H. Sayer, D. L. Holford, W. Bruine de Bruin, C. Booker, T. Chadborn, G. Vallee-Tourangeau, R. M. Wood, and M. Sirota. 2024. Vaccination invitations sent by warm and competent medical professionals disclosing risks and benefits increase trust and booking intention and reduce inequalities between ethnic groups. Health Psychology.

Larson, H. J., C. Jarrett, E. Eckersberger, D. M. Smith, and P. Paterson. 2014. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine 32(19):2150–2159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081.

Miller, E. R., P. L. Moro, T. T. Shimabukuro, G. Carlock, S. N. Davis, E. M. Freeborn, A. L. Roberts, J. Gee, A. W. Taylor, R. Gallego, T. Suragh, and J. R. Su. 2023. COVID-19 vaccine safety inquiries to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Immunization Safety Office. Vaccine 41(27):3960–3963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.05.054.

Miller, J. 2025. After rocky history, GSA shuts down 18F office. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/reorganization/2025/03/after-rocky-history-gsa-shuts-down-18f-office/ (accessed April 22, 2025).

Nowak, G. J., B. G. Gellin, N. E. MacDonald, and R. Butler. 2015. Addressing vaccine hesitancy: The potential value of commercial and social marketing principles and practices. Vaccine 33(34):4204–4211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.039.

Nowak, G. J., A. K. Shen, and J. L. Schwartz. 2017. Using campaigns to improve perceptions of the value of adult vaccination in the United States: Health communication considerations and insights. Vaccine 35(42):5543–5550.

Quinn, S. C., A. M. Jamison, J. An, G. R. Hancock, and V. S. Freimuth. 2019. Measuring vaccine hesitancy, confidence, trust and flu vaccine uptake: Results of a national survey of White and African American adults. Vaccine 37(9):1168–1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.033.

Reyna, V. F., W. L. Nelson, P. K. Han, and N. F. Dieckmann. 2009. How numeracy influences risk comprehension and medical decision making. Psychological Bulletin 135(6):943.

Sarathchandra, D., and J. Johnson-Leung. 2024. How political ideology and media shaped vaccination intention in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. COVID 4(5):658–671. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4050045.

Stewart, M. C., and C. L. Arnold. 2017. Defining social listening: Recognizing an emerging dimension of listening. International Journal of Listening 32(2):85–100 https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.2017.1330656.

Su, J. R. 2024. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 vaccine safety monitoring from December 2020—May 2023. Presentation to the Committee to Review the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Research and Communications, Washington, DC, June 24, 2024.

Warren, A. M., M. M. Bennett, B. da Graca, A. C. Waddimba, R. L. Gottlieb, M. E. Douglas, and M. B. Powers. 2023. Intentions to receive COVID-19 vaccines in the United States: Sociodemographic factors and personal experiences with COVID-19. Health Psychology 42(8):531.

Zipkin, D. A., C. A. Umscheid, N. L. Keating, E. Allen, K. Aung, R. Beyth, S. Kaatz, D. M. Mann, J. B. Sussman, and D. Korenstein. 2014. Evidence-based risk communication: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine 161(4):270–280. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-0295.