Reducing the Threat of Improvised Explosive Device Attacks by Restricting Access to Explosive Precursor Chemicals (2018)

Chapter: 4 International Regulations

4

International Regulations

Other countries have preceded the United States in developing policies to address concerns about access to precursor chemicals, and their experience can inform decisions about policy, including control strategies, in the United States. Table 4-1 compares regulations on precursor chemicals across the globe. Authorities generally agree on the types of chemicals that should be controlled, but differ in how they enact and implement policy. This chapter summarizes the policies of Australia, Canada, Singapore, the European Union (EU), and the United Kingdom.

To supplement publicly available documentation on policy and programs, two members of the committee and one staff member visited the European Commission (EC) in Brussels, Belgium, and the United Kingdom’s Home Office in London, England, to learn firsthand about how they regulate precursor chemicals; the committee developed a list of questions that it sent in advance of these meetings to guide the discussions (see Appendix E). Information gathered from these meetings is described in the EU section.

The countries were selected because of their collaborative relationships with the United States; however, each has taken different mandatory and voluntary approaches to restricting malicious actors’ access to precursor chemicals. The committee investigated the EU and United Kingdom’s programs because of the challenges faced implementing new regulations and voluntary measures across Europe using a common framework, but allowing different strategies in each of the EU member states (MS). The committee examined Canada’s program because of Canada’s proximity to the United States and its streamlined approach to counter-terrorism. Australia provides an example of a whole-of-government- and-industry approach that is implemented within a decentralized framework.

TABLE 4-1 Comparative Chart of Global Regulations on Precursor Chemicals

| Chapter 2 | CFATS | Australia | Canada | EU | Singapore | PGS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetone | X | X | |||||

| Aluminum powder | A | X | X | X | |||

| Ammonium nitrate | A | X | ≥45%s | >80% | >16%N | ≥80% | X |

| Ammonium perchlorate | C | X | ≥65%s 10%a | X | X | ||

| Antinomy trisulfide | C | ||||||

| Barium nitrate | X | ||||||

| Calcium ammonium nitrate | A | X | X | ||||

| Calcium nitrate | B | X | |||||

| Guanidine nitrate | X | ||||||

| Hexamine | C | X | |||||

| Hydrochloric acid | B | ||||||

| Hydrogen peroxide | A | ≥35% | ≤65% | >30% | >12% | ≥20% | X |

| Magnalium powder | C | X | |||||

| Magnesium powder | C | X | X | ||||

| Magnesium nitrate hexahydrate | X | ||||||

| Nitric acid | A | ≥68% | ≥30% | >68% | >3% | X | |

| Nitrobenzene | X | ||||||

| Nitromethane | A | X | ≥10% | X | >30% | X | |

| Pentaerythritol | C | ||||||

| Perchloric acid | X | X |

| Phenol | C | ||||||

| Phosphorus | X | X | |||||

| Potassium chlorate | A | X | ≥65%s 10%a | X | >40% | X | X |

| Potassium nitrate | B | X | ≥65%s 10%a | X | X | ≥5%a | X |

| Potassium nitrite | C | ≥5%a | |||||

| Potassium perchlorate | A | X | ≥65%s 10%a | X | >40% | X | X |

| Potassium permanganate | B | X | |||||

| Sodium azide | X | >95% | |||||

| Sodium chlorate | A | X | ≥65%s 10%a | X | >40% | X | X |

| Sodium nitrate | B | X | X | X | ≥5%a | X | |

| Sodium nitrite | B | ≥5%a | |||||

| Sodium perchlorate | ≥65%s 10%a | >40% | X | ||||

| Sulfur | B | ||||||

| Sulfuric acid | B | X | X | ||||

| Tetranitromethane | X | ||||||

| Urea | B | X | |||||

| Urea ammonium nitrate solution | A | ||||||

| Zinc powder | B |

NOTE: %s: percent composition in a solid mixture; %a: percent composition in an aqueous solution; the letters in the second column correspond to the prioritized groups from Chapter 2; CFATS: Chemical Facilities Anti-Terrorism Standards; PGS: Programme Global Shield; the EU column includes both Annex I and Annex II chemicals.192

Finally, Singapore provides an example of a country that is developing a very proactive counter-terrorism program given repeated threats from various groups.

AUSTRALIA

After numerous incidents—the 2002 Bali bombings, which killed dozens of Australians; the conviction of five Sydney men in 2009 for a terrorism-related conspiracy; and a 2010 incident in which a homemade explosive (HME) exploded prematurely during transport, accidentally killing two men in Adelaide—the Australian government, along with state and territory governments, businesses, and industry, developed a voluntary National Code of Practice for Chemicals of Security Concern, which was enacted in July 2013.193-195 The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) identified ninety-six chemicals of concern and developed a voluntary code of practice for fifteen high-priority precursor chemicals that can be used to make HMEs (see Table 4-1).

The goals of this code are to protect against theft and diversion, promote precursor chemical awareness between business and law enforcement, and educate personnel on suspicious transactions. While there is no direct federal government involvement since it is a voluntary code, the government does provide guidelines for implementation of the code in several areas, including the following:

- security risk management, which assesses the security risk of each business and assigns a security management point of contact who is responsible for investigating and reporting security incidents to the National Security Hotline;

- security measures chosen to reduce the risk of terrorists acquiring chemicals from each business by providing background checks on potential employees, educating staff on suspicious behavior, maintaining inventory control records, and reporting thefts or diversions; and

- supply chain security to verify the identity of all customers and promote transportation security of chemicals.

Security sensitive ammonium nitrate (SSAN) is subject to state and territory regulations and is not subject to the national code.196,197 In June 2006, the COAG introduced a licensing regime for the use, manufacture, storage, transport, import, and export of SSAN, which comprises pure ammonium nitrate (AN), AN mixtures containing greater than 45% AN, and AN emulsions; SSAN does not include solutions or Class 1 explosives (explosive substances and articles, and pyrotechnics). The SSAN regulations form part of each Australian state’s explosives regulations. Transporters moving more than 20 kg of SSAN or storing more than 3 kg need an annual background check. They undergo inspections to ensure that they have secure, lockable storage; maintain detailed records of usage; and have a security plan.

Unfortunately, it is not clear how successful this voluntary code alone has been on mitigating terrorist acquisition of precursor chemicals because of other counter-terrorism–related laws that were passed around the same time, including a telecommunications act198 that allows companies to keep a limited amount of metadata for 2 years; an act against foreign fighters199 that allows Australia to arrest, monitor, investigate, and prosecute as well as cancel passports for returning foreign fighters; and a counter-terrorism act200 that responds to operational priorities identified by law enforcement and intelligence and defense agencies. Australia has not had a major terrorist attack on its soil. The attack by Numan Haider on two police officers in September 2014 and the siege at Martin Place in December 2014 have been the only successful terrorist attacks in Australia, and neither involved precursor chemicals.201 Additionally, focused counter-terrorism efforts conducted by intelligence and law enforcement agencies have resulted in the apprehension of terrorists plotting events in Australia.202-206

CANADA

Natural Resources Canada’s Explosives Safety and Security Branch administers the Explosives Act and Explosives Regulations for the safe and secure handling of explosives.207 The Explosives Act

- requires anyone working with explosives to have a license, certificate, or permit issued by the Minister of Natural Resources;

- makes exceptions to this requirement for some explosives and storage activities and for the use of certain low-hazard explosives, low-hazard pyrotechnic devices, sporting ammunition, and consumer fireworks; and

- covers fireworks, pyrotechnics, propellant powders, ammunition, rocket motors, and restricted components.

Part 20 of the Explosives Regulations discusses the sale of and security plans for restricted components. The restricted components are the chemicals listed in Table 4-1 under the Canada heading. Parties must apply to sell a restricted component or to manufacture a product containing a restricted component. The application includes the applicant’s personal information, the restricted components to be sold, the address of each location where a restricted component will be stored or sold and the storage capacity, and the name and personal information of the contact person for each location where a restricted component will be stored or sold. If AN is to be sold, the applicant must also submit a security plan and notify purchasers and/or transporters of security requirements, in addition to producing annual inventory reports that are delivered to the Explosives Regulatory Division (ERD) Chief Inspector of Explosives. The purchaser of any restricted component must provide photo identification (ID) and state the intent of use.

Since the implementation of this regulation, the ERD has seen an increase in products approved for sale in Canada and in importation permits, and has increased its compliance monitoring activities. The ERD developed a rating system for assessing the number and types of deficiencies found during inspections. It noted a decrease in reported deficiencies as a result of its compliance monitoring and assessments.208 It is unclear whether the Explosives Act has had any impact on terrorism in Canada. Since 2009, Canada has charged twenty-one individuals with terrorism-related offenses that have been associated with bomb-making activities.209

SINGAPORE

Singapore has been targeted by terrorist groups and remains at a relatively high security alert. It has partnered with other nations in counter-terrorism.210-212 It has also conducted major counter-terrorism–related exercises to assess and refine its readiness for terrorist attacks.213 While there have not been terrorist attacks in Singapore, the country has developed proactive measures at its borders to enhance and improve government agencies’ internal cooperation regarding precursor chemicals.

In 2007, fifteen hazardous substances listed in the Environmental Pollution Control Act and Regulations were delisted and instead listed in the Arms and Explosives Act.214,215 The majority of the hazardous substances appear on the prioritized list of precursor chemicals in this report (Table 4-1). The Arms and Explosives Act clearly details the concentrations at which a material comes under its regulation. Singapore implements a licensing program to import, export, possess, manufacture, deal in, or store any of these fifteen substances. Possession is prohibited without a license. Application for a license can be made online or via phone. The license is precursor specific, and a licensee must undergo a background check and establish experience with and knowledge of how to handle the precursor chemical. All transactions must be recorded.

EUROPEAN UNION

The EU passed Regulation 98/2013 on the use and sale of explosives precursors in September 2014.28 The policy action introduced a common regulatory framework across Europe regarding the “making available, introduction, possession and use, of certain substances or mixtures that could be used in the manufacture of home-made explosives.” The regulation restricts access to and use of seven restricted explosives precursors (listed in Annex I of the regulations) by members of the general public. EU MS may grant access to these substances to the public through a system of licenses and registration, but a ban is the default. In addition, the regulation introduces rules for retailers who place such substances on the market. Retailers must ensure the appropriate labeling of restricted precur-

sor chemicals and must report any suspicious transactions involving either the restricted or other nonrestricted substances that are considered items of concern (the latter listed in Annex II).

Under the regulation, each of the EU MS designates a competent authority and implements the ban, licensing, or registration processes. The authority is required to set up its own national contact point(s) for the reporting of suspicious transactions. The EC is tasked with providing the list of measures and guidelines to facilitate implementation.

The Standing Committee on Precursors

The Standing Committee on Precursors (SCP) is an expert group composed of representatives of EU MS and industry associations. It was established under the 2008 EU Action Plan on Enhancing the Security of Explosives and is chaired by the EC.216,217 As depicted by the EC, the SCP provides a platform for EU MS and representatives of the operators in the supply chain to exchange information and share lessons learned on implementation.191 It also helps facilitate the implementation of Regulation 98/2013 with the goal of limiting the general public’s access to precursor chemicals and encouraging suspicious transactions and appropriate reporting of significant disappearances and thefts throughout the supply chain, while seeking minimal market disruption.

To create awareness in support of these goals, the SCP has issued guidance materials to inform the authorities and retailers of the EU MS of their roles and responsibilities under the regulation (see Appendix F).

Labeling, which is required, is another tool that can raise awareness but might not enhance security. For example, labeling might inadvertently alert bomb makers that a product can be used to make bombs. If the purpose of labeling is to provide retailers with information on targeted products so that they can meet their legal requirements, then retailers need to be able to get the information on products from manufacturers and/or suppliers; thus, notification in shipping materials might be as useful as labels, without jeopardizing security. The questions of the intended target of labeling (i.e., the customer or the retailer) and the purpose of labeling have not been answered.218

Compliance Effectiveness

EU Member States

Regulation 98/2013 defaults to a ban unless the EU MS tailor the regulation to meet their specific circumstances (i.e., licensing and/or registration). According to the EC’s January 2017 report,191 most EU MS were in compliance; the report included the following highlights:

- all EU MS identified one or more points of contact for suspicious transaction reporting and thefts;

- twenty-three EU MS were in full compliance, and had set rules and penalties, disseminated the implementation guidelines, and notified the EC of exceptions that would require licensing or registration; and

- five EU MS were in partial compliance, having not developed rules or penalties.

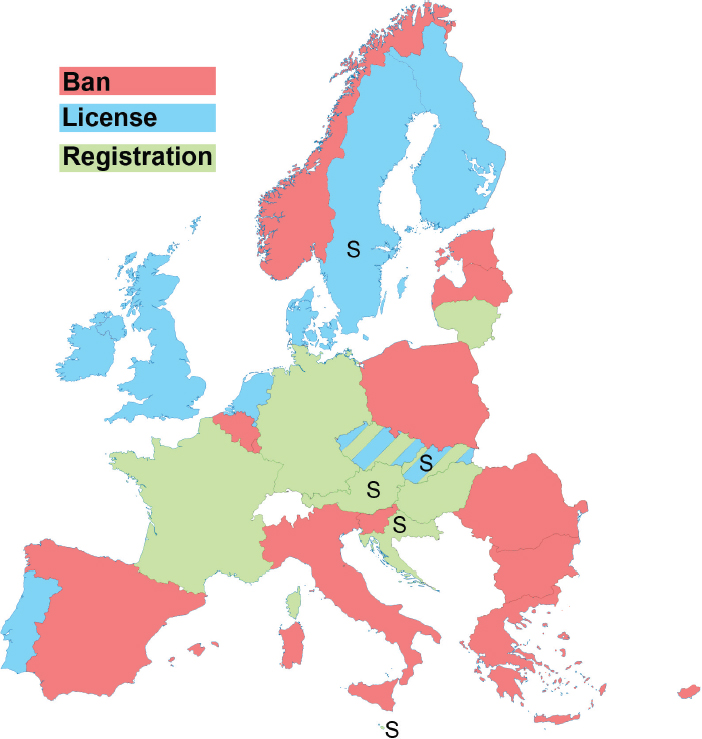

To promote compliance, the EC established regular bilateral discussions focused on implementation and potential regulation compliance issues with some EU MS.219 An updated list of measures is available via the EC, which details each member’s choice with regard to regulatory strategy (Figure 4-1).220

While some EU MS have opted for the default, a ban on public access, others have chosen combinations of licenses and registration. There is significant variation in the processes for requesting licenses, including the criteria on which the requests are evaluated for approval or refusal, and the length and type of validity. Some EU MS accept that the request for a license should be granted unless there is a specific reason to refuse, while others refuse licenses unless there is a specific reason to grant them. Rates of licensing thus differ greatly from state to state, and there are no known instances of mutually recognized licenses.

The EC also reports that some EU MS have adopted additional measures that, for example, require retailers to register with the authorities and to periodically declare all transactions, including imports; extend the scope of the regulation to cover professional users; determine conditions for storage; foresee the exchange of relevant cross-border information with other EU MS; or establish a role for customs authorities.191 Additionally, most EU MS have reportedly conducted awareness-raising campaigns that target the retailers marketing the precursor chemicals. Campaigns aim to increase awareness about the obligation to both restrict access and report suspicious transactions. Some EU MS have actively engaged online suppliers and marketplaces.

The United Kingdom

The United Kingdom’s Control of Explosives Precursors Regulations 2014, which applies to England, Scotland, and Wales (Northern Ireland is covered separately221), came into force on September 2, 2014, as a means to implement Regulation 98/2013, and provides a case study on the approach of a particular EU MS to implementation. The United Kingdom’s Home Office summarized the regulations as follows:

- the public may obtain a 3-year license to obtain and use the seven regulated precursor chemicals above their concentration thresholds, provided the applicants pass a background and medical check;

- licenses may be issued subject to conditions, for example, storage, use, quantities, concentration, and reporting loss or thefts;

- the supplier must verify the license and associated photographic identification of the purchaser and record the transaction details on the back of the license, and suppliers of Annex I substances must also ensure that such substances are labeled as restricted; and

- any violation of the regulation is punishable with up to 2 years imprisonment or a fine or both, with the possibility of lesser penalties for lesser offenses, such as minor clerical omissions.

As part of the regulatory process, the United Kingdom’s Home Office, in cooperation with the Ministry of Justice and Her Majesty’s Treasury, developed

an impact assessment, much like a regulatory assessment in the United States (see Appendix G). The assessment considered the benefits, costs, and risks associated with doing nothing, or implementing a ban, licensing, or a registry in relation to three policy objectives:

- prevent terrorists from using precursor chemicals to make explosives;

- provide a mechanism for alerting authorities of illicit activities; and

- minimize the burdens on industry and legitimate users.

With that assessment, the United Kingdom chose to implement a licensing scheme, but not an accompanying registration program. Meetings with stakeholders suggested that an auxiliary registration program would create unnecessary confusion.222

Regulation Effectiveness

The EC reports223 that Regulation 98/2013 has contributed to reducing the threat posed by precursor chemicals in Europe based on findings from meetings and consultations of the SCP and a study carried out by an independent expert consortium:

- The amount of precursor chemicals available on the market has decreased. This is partly because many retailers are applying the restrictions or have opted to stop selling the chemicals and partly because, voluntarily, some manufacturers have stopped making them. The supply chain has not reported any significant disturbances or economic losses as a result of this. Also, in some EU MS that maintain licensing, authorities have reported that the number of license applications is currently significantly lower than it was during the first year of application of the regulation. This suggests that members of the general public have successfully adopted alternative (nonsensitive) substances for continuing with their legitimate nonprofessional activities.

- The capacity of law enforcement and designated authorities to investigate suspicious incidents involving precursor chemicals has increased. EU MS have reported an increase in the number of reported suspicious transactions, disappearances, and thefts due to greater awareness among retailers who handle precursor chemicals. In addition, some EU MS have, on an ad hoc basis, exchanged information on reports and refused licenses. Finally, the authorities in EU MS that maintain licensing regimes have a better understanding of which members of the general public are in possession of restricted substances and the purpose they intend to use them for.

The EC has noted that it is not yet possible to assess the impact of the regulation on terrorist activities in more detail; however, EC officials indicated during the meeting in Belgium that some EU MS have thwarted potential terrorist activities, suggesting that the application of the regulation has contributed to the EC efforts to prevent terrorist attacks involving HMEs.223 The EC also reported several challenges and costs, some of which are outlined below.

Challenges and Initial Responses

Preliminary evidence suggests that Regulation 98/2013 is contributing to security.191 For example, in the United Kingdom, successes in reporting dangerous activities are available via a government-sponsored podcast,224 and certain individuals who reportedly provided materials to terrorists have been identified.225 However, there are challenges and costs incurred in several areas of implementation:

- authorities have had difficulty reaching all suppliers to inform them of their duties;

- authorities have had difficulty enforcing the restrictions and controls on internet sales, imports, and intra-EU movements, especially of small quantities;

- retailers have had difficulty identifying products that fall under the scope of the regulation;

- labeling, which is required, conveys risks of inadvertent disclosure;

- businesses that operate across intra-EU borders face the challenge of compliance with multiple regulatory schemes;

- economic operators have encountered difficulty determining whether the purchaser is a professional user or a member of the general public, because they do not have a process for establishing and verifying qualifications (one unnamed country is allegedly developing standardized industrial classification codes of those professions likely to need access); and

- evolving security threats present a continuous challenge that requires regulatory adaptability.

For a complete presentation of these challenges and some responses, see Box 4-1.

GLOBAL SHIELD

In an effort to mitigate the improvised explosive device (IED) threat, the World Customs Organization, in conjunction with Interpol, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, and the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, initiated a 6-month pilot program, Programme Global Shield (PGS), in November 2010.226

The program was aimed at enhancing awareness and information sharing on the global movements of fourteen chemicals (see Table 4-1).227,228

Program operations included training and establishing national contact points with the responsibility of providing monthly shipping reports on these fourteen precursors. A centralized multilingual web-based communication channel was set up to report suspicious movements and to act as a repository for project communications.229

The World Customs Organization endorsed the program as a long-term endeavor, with the overall objectives of promoting international cooperation to prevent precursor chemical diversion, interdicting illegal shipments, and promoting awareness among industry and other groups.

Between 2011 and 2014, PGS resulted in the seizure of 40–100 tons of precursor chemicals per year.230 This increased dramatically in 2015 to about 544 tons of solid precursor chemicals, largely due to sustained seizures along the

Afghanistan-Pakistan border by local agencies. The bulk of the amount (about 487 tons) consisted of AN and urea. In addition to precursor chemicals, PGS resulted in the seizure of detonators and completed HMEs and IEDs.

CONCLUSION

This chapter shows a range of approaches to restricting access to precursor chemicals and highlights the resulting challenges, some of which might pertain to a U.S. strategy and therefore merit further consideration. While a variety of approaches are used, the effectiveness of the programs is difficult to assess and compare, let alone quantify. Different avenues of terrorist attack will not be equally likely across countries given the different laws and regulations (e.g., the control of firearms in the United States versus the United Kingdom) and threat environments in each country. Thus, for the purposes of controlling precursor chemicals, it is necessary to gather data on the international controls only as they relate to the goal of limiting access to the precursor chemicals, and not their ability to deal with terrorism as a whole.

Market Level

Policy in other countries tends to focus on retail-level points of sale, whereas policy in the United States tends to focus on manufacturing, storage, and distribution. The EU defaults to a ban but allows flexibility for EU MS to implement licensing or registration for sales to the general public. Canada and Singapore have implemented similar licensing or registration measures for controlling access to precursor chemicals. By contrast, as described in Chapter 3, policy in the United States rarely addresses retail facilities or transactions, except in the case of agriculture.

Preliminary evidence of the retail-level controls implemented in the EU indicates a decrease in the amount of precursor chemicals that are available on the market, and an increase in the reporting of suspicious transactions, but with some costs to commerce and legitimate users.

Responsible Entities

Another difference between most of the countries described above and the United States is that precursor chemicals in the United States are not regulated by one responsible entity. This is similar to Australia, where there is a national guidance, but authority is devolved throughout its federal system.

In the United States, many federal and other agencies are involved to varying degrees along the supply chains, including the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Department of Transportation (DOT), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

Each maintains its own regulations and programs, intended to meet respective objectives for security, safety, the environment, and health. Because of this configuration, the committee found inconsistencies and possible gaps in coverage.

Harmonization

The United States might face similar challenges as the EU in its efforts to harmonize policy across EU MS. As the foregoing presentation of challenges and responses suggests, differences in implementation across MS might make it difficult to enforce restrictions on internet sales, imports, and intra-EU trade, and might require costly adaptations. With open internal borders, the EU is only as secure as its most vulnerable point of purchase. If malicious actors cannot obtain a precursor chemical in one member state, they can try another. In the United States, differences between federal law, state law, and local ordinance, and related concerns about the role of government, could present analogous challenges, depending on how policy unfolds going forward. The authoring committee of the 1998 Academies report observed that “a criminal in the United States can easily purchase precursor chemicals in a state with few requirements and then use them anywhere in the United States.”14 Furthermore, malicious actors now have the option to purchase precursor chemicals online, another widely available means of interstate trade.

EU regulations, PGS efforts, and HME collaborations between and among countries illustrate global cooperation in developing methods to minimize the broad access that terrorists have to precursor chemicals. These efforts as well as country-specific efforts will continue to increase compliance and awareness with current law enforcement security programs. While many countries conduct separate counter-terrorism response drills, cross-border drills can be conducted to understand the flow of information and resources and the changes in custody of precursor chemicals.

This page intentionally left blank.