Breastfeeding in the United States: Strategies to Support Families and Achieve National Goals (2025)

Chapter: 2 The Importance of Breastfeeding Across the Life Course

2

The Importance of Breastfeeding Across the Life Course

This chapter highlights the importance of breastfeeding, with a particular focus on its associated health benefits for both mothers and infants. In alignment with its statement of task, which did not call for a novel evidence review, the committee offers a summary of existing research, drawing primarily from meta-analyses and systematic reviews of key health outcomes. The chapter then examines the physiology of breastfeeding and human lactation, explaining the biological processes that enable lactation and the mechanisms through which health benefits may be conferred. Taking a life course perspective, the chapter next identifies critical inflection points, such as prenatal care, birth experiences, and early postpartum support, that can influence breastfeeding initiation and duration, and ultimately, health outcomes. An overview of current breastfeeding rates in the United States follows, identifying trends and differences across populations. Finally, the chapter reviews existing modeling efforts aimed at estimating the economic costs associated with current, suboptimal breastfeeding rates.

THE HEALTH BENEFITS OF BREASTFEEDING

Decades of research show that breastfeeding is associated with short- and long-term benefits for children and mothers. To date, the most comprehensive and widely cited systematic review on the relationship between breastfeeding and infant and maternal health outcomes is a report by Ip et al. (2007). Feltner et al. (2018) partially updated that report but focused only on the maternal health benefits of breastfeeding. Several recent reviews, including those from the Pregnancy and Birth to 24 Months Project

(Güngör et al., 2019a,b,c,d; Obbagy et al., 2019; Stoody et al., 2019) and others (Brown et al., 2019; Dewey et al., 2021; Horta et al., 2015, 2023; Lockyer et al., 2021; Meek et al., 2022; Pathirana et al., 2022; Rollins et al., 2016; Su et al., 2021; Victora et al., 2016) have examined specific infant and child outcomes.

Recently, a systematic review by Patnode et al. (2025) comprehensively updated the evidence from Ip et al. (2007) on the link between breastfeeding and infant and child outcomes. This review advances understanding of the potentially nuanced benefits of breastfeeding for infant- and child-specific health outcomes; the magnitude of those benefits; and how they vary with the intensity, duration, mode of feeding, and source of human milk. However, this review did not include preterm infants or infants requiring intensive care. In the sections that follow, the committee briefly describes the evidence on potential health impacts of breastfeeding for mothers and children, including sick or vulnerable infants and children.

Maternal Health Benefits

In mammalian physiology, discussed later in this chapter, lactation and the practice of breastfeeding1 follow pregnancy. Breastfeeding is also associated with significant health benefits for women over the course of their lives and is a normal part of reproductive physiology and recovery from pregnancy.

In the immediate postpartum period, women who breastfeed experience more rapid uterine involution, decreased postpartum bleeding, and increased child spacing (Louis-Jacques & Stuebe, 2020; Victora et al., 2016). These immediate postpartum benefits are important, as hemorrhage is a leading cause of maternal postpartum morbidity (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2017; Del Ciampo & Del Ciampo, 2018; Victora et al., 2016). Findings from Feltner et al. (2018) suggest that ever breastfeeding or breastfeeding for longer durations “may be associated with lower rates of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes” (p. ix). The authors went on to conclude there were inconsistent findings related to postpartum depression, weight change after birth, and cardiovascular disease (Feltner et al., 2018). Two systematic reviews and a large prospective cohort study published since 2018 have provided additional evidence on the association of breastfeeding duration with reduced maternal risk of cardiovascular disease outcomes (Tschiderer et al., 2022), including among women with diabetes complicating pregnancy

___________________

1 As noted in Chapter 1, breastfeeding refers to the dynamic physiological process and interactions that occur between a mother and infant, including feeding at the breast and/or feeding expressed or pumped human milk.

(Birukov et al., 2024; Field et al., 2025). Chehayeb et al. (2025) also reported that breastfeeding is associated with a lower risk of triple negative breast cancer.

Researchers have also examined whether there is a relationship between breastfeeding and psychosocial outcomes for the breastfeeding dyad, such as attachment, bonding, and maternal mental health. Peñacoba and Catala (2019) conducted a systematic review of the literature related to associations between breastfeeding and mother–infant dyad relationships. The review included 13 studies; most of which were conducted in Europe (46.15%) and were nonexperimental in design (92.3%). The authors found that the relationship indicators most frequently associated with breastfeeding are maternal sensitivity and secure attachment, though the association is complex, and the breastfeeding relationship or method of feeding appears to influence outcomes. Furthermore, a review by Tucker and O’Malley (2022) noted that breastfeeding can have a positive impact on maternal mental health, specifically as it relates to postpartum depression, self-efficacy, and dyad bonding. The authors went on to state that breastfeeding difficulties or early cessation can be a risk factor and could potentially exacerbate perinatal mood and anxiety disorders if proper social support and lactation care are not provided or accessible (Tucker & O’Malley, 2022).

These findings point to the importance of breastfeeding for mothers across the life course. Yet, additional research is needed to further understand the relationship between breastfeeding and maternal physical and mental health.

Health Benefits for Infants and Children

As noted in Chapter 1, human milk provides all the nutrients necessary to support optimal growth and development for nearly all infants for the first six months of life and provides continued essential nutrition and developmental benefits for the duration2 of breastfeeding. As briefly described in Chapter 1, infants who are breastfed “more” versus “less” may have a reduced risk of developing noncommunicable diseases such as asthma, otitis media, obesity in childhood, and childhood leukemia (Patnode et al., 2025). In addition, a protective association of breastfeeding has been found for infant mortality, including sudden infant death, rapid weight gain and growth, systolic blood pressure, severe respiratory and gastrointestinal infections in younger children, allergic rhinitis, malocclusion, inflammatory bowel disease, and type 1 diabetes (Patnode et al., 2025). Breastfeeding can

___________________

2 Professional and public health organizations recommend that, when possible, breastfeeding be continued with appropriate complementary food for two years or as long as mutually desired (ACOG, 2021, 2023; Meek et al., 2022; World Health Organization [WHO], 2023b).

also be lifesaving in humanitarian emergencies, including natural disasters and supply chain disruptions (e.g., Bartick et al., 2024; Cerceo et al., 2024; see Chapters 4 and 5).

Patnode et al. (2025) identified several key findings related to the health effects of breastfeeding for infants, as presented in Table 2-1.

While the Patnode et al. (2025) review did not find associations between breastfeeding and cognitive benefits for infants, other studies have found such relationships (e.g., Belfort et al., 2013; Fitzsimons & Vera-Hernández, 2022; Goldshtein et al., 2025; Horta et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2018). For example, using variation in timing of births at hospitals and likelihood of breastfeeding, Fitzsimons and Vera-Hernández (2022) estimated the effect of breastfeeding on children’s development in the first seven years of life, for a sample of births by low-educated mothers. They found large effects of breastfeeding on children’s cognitive development (Fitzsimons & Vera-Hernández, 2022). Furthermore, a retrospective cohort study from Israel that included more than half a million children reported that longer exclusive and any breastfeeding durations was associated with reduced odds of developmental delays, as well as language or social neurodevelopmental conditions (Goldshtein et al., 2025), which the authors suggest may mediate the relationship between breastfeeding and cognitive development. The study specifically found that children who were breastfed for at least six months versus children breastfed for less than six months had fewer delays in attaining language and social or motor developmental milestones. The corresponding adjusted odd ratios (AORs) were 0.73 (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.7–10.76) for exclusive breastfeeding and 0.86 (95% CI: 0.83–0.88) for nonexclusive breastfeeding). Importantly, among the 37,704 sibling pairs, children who were breastfed for at least six months were less likely—compared with their sibling with less than six months of breastfeeding or no breastfeeding—to demonstrate developmental delays or be diagnosed with neurodevelopmental conditions. The corresponding AORs were 0.91 (95% CI: 0.86–0.97) and 0.73 (95% CI: 0.66–0.82; Goldshtein et al., 2025). Therefore, the current evidence base suggests that some cognitive outcomes may be associated with breastfeeding, but additional research is needed to further elucidate this relationship, including the potential causal pathways and contextual factors that may moderate this relationship. Differences in study design, populations studied, and methods for accounting confounding factors may influence findings.

Health Benefits for Sick or Vulnerable Infants and Children

In the United States, approximately 300,000 infants are admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), each year (Pineda et al., 2023). NICU admissions for critically ill infants increased 13% between 2016 and

2023 (Martin & Osterman, 2025). Sick or vulnerable infants, especially those who are born early (before 37 weeks gestation), at low birth weight (less than 5.5 pounds) and very low birth weight (less than 3.3 pounds), have an increased risk of short- or long-term health problems (Boundy et al., 2022). For critically ill infants, human milk has been identified as a lifesaving intervention (Parker et al., 2021; Schanler, 2011; Spatz, 2004; Sullivan et al., 2010; Underwood, 2013; Updegrove, 2004).

Miller et al. (2018) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis that synthesized literature, started after the 1990s, which examined the effect of human milk on morbidity, specifically necrotizing enterocolitis, late-onset sepsis, retinopathy of prematurity, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and neurodevelopment in infants born at or before 28 weeks’ gestation; they also reviewed publications with reported infant mean birth weight of 1,500 grams or more. Experimental and observational studies were pooled separately in the meta-analyses. Risk of bias was assessed for each individual study, and the GRADE3 system was used to judge the certainty of the findings. Forty-nine studies (with 56 reports) were included, of which 44 could be included in meta-analyses. Miller et al. (2018) found that human milk was associated with a protective effect against necrotizing enterocolitis, with an approximate 4% reduction in absolute risk.

Parker et al. (2021) also reported that human milk was associated with a reduction in late-onset sepsis, severe retinopathy of prematurity, and severe necrotizing enterocolitis. Particularly for necrotizing enterocolitis, any volume of human milk was found to be better than exclusive preterm formula—the higher the dose, the greater the protection. Altobelli et al. (2020) found that the risk of developing necrotizing enterocolitis is significantly lower when combining mother’s own and pasteurized donor human milk. Improving the intake of mother’s own and/or donor human milk results in small improvements in morbidity in this population (Miller et al., 2018). Parker et al. (2021) described in detail the dose–response relationship when providing mother’s own milk for hospitalized very low birth weight infants; exposures of human milk were variable across the studies, but results point to a strong association between higher doses of mother’s own milk with improved health benefits.

See Chapter 9 for future research needs and priorities, including the need to test the efficacy and effectiveness of strategies for supporting the provision of donor human milk for sick and vulnerable infants, including those who are critically ill.

___________________

3 GRADE is short for Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; it is a systematic approach to rating the certainty of evidence in systematic reviews and other evidence syntheses (Cochrane Collaboration, 2025).

| SOE and Direction of Association | Outcome | Number of ESRs (k in newest ESR) (Credibility)a |

Number of Primary Studies by Design (ROB)b |

Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate SOE for reduced risk | Otitis media | 1 ESR (k = 24) (1 High) |

10 cohort (3 Some concerns, 6 High, 1 Very high) |

Reduced risk of otitis media associated with breastfeeding, particularly at younger ages (≤24 months). Pooled analyses showed an approximately 33% reduced risk of otitis media when comparing ever versus never breastfeeding and for longer versus shorter durations of any breastfeeding, and a 43% reduced risk when comparing longer versus shorter durations of exclusive breastfeeding. |

| Asthma | 3 ESRs (k = 42) (1 High, 1 Mod, 1 Low) |

11 cohort (5 Some concerns, 6 High) |

Reduced risk of asthma in childhood (2–12 years) associated with breastfeeding. The magnitude of the relative risk in pooled analyses ranged from approximately a 7 to 31% reduced risk of asthma with longer versus shorter durations of any breastfeeding and a 6 to 30% reduced risk when comparing longer versus shorter durations of exclusive breastfeeding. | |

| Obesity | 3 ESRs (k = 159) (2 Moderate, 1 Low) |

25 cohort (9 Some concerns, 12 High risk, 4 Very high risk) |

Lower risk of overweight and obesity in children two to 12 years old associated with breastfeeding. The magnitude of the association suggests a 15 to 34% reduced odds of having obesity with more versus less breastfeeding and a 4% reduction in the risk of early childhood obesity for every additional month of breastfeeding. |

| Cancer | 2 ESRs (k = 46) (1 High, 1 Moderate) |

2 cohort, 3 case-control (2 Some concerns, 2 High, 1 Very high) |

Reduced risk of childhood leukemia associated with breastfeeding, with pooled analyses suggesting a 10 to 23% reduced risk of childhood leukemia with ever versus never breastfeeding. No clear association for other cancer types. | |

| Low SOE for reduced risk | Respiratory infections | 2 ESRs (k = 16) (2 Low) |

35 cohort (2 Low, 14 Some concerns, 17 High, 2 Very high) |

Potential reduced risk of respiratory infections of greater severity associated with breastfeeding, particularly among infants and children ages 24 months or less. No evidence on COVID-19. |

| Diarrhea and GI infection | 1 ESR (k = 8) (1 Low) |

15 cohort (1 Low, 7 Some concerns, 5 High, 2 Very high) |

Potential reduced risk of moderate-to-severe GI infections and breastfeeding at younger ages, particularly in infants six months or less. No clear association between breastfeeding and GI infection in infants and children of older ages. | |

| Allergic rhinitis | 3 ESRs (k = 23) (2 High, 1 Low) |

4 cohort (2 Some concerns, 2 High) |

Potential reduced risk of allergic rhinitis associated with breastfeeding. | |

| Malocclusion | 2 ESRs (k = 14) (2 Moderate) |

No studies | Potential reduced risk of the development of malocclusion associated with any or exclusive breastfeeding, with inconsistent evidence on breastfeeding duration. | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 2 ESRs (k = 42) (1 Moderate, 1 Low) |

1 case-control, 2 cohorts, 1 pooled cohort (1 Low, 1 Some concerns, 1 High, 1 Very high) |

Potential reduced risk of inflammatory bowel disease associated with longer vs. shorter duration of breastfeeding. |

| SOE and Direction of Association | Outcome | Number of ESRs (k in newest ESR) (Credibility)a |

Number of Primary Studies by Design (ROB)b |

Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 diabetes | 2 ESRs (k = 22) (2 Low) |

1 case-control, 2 cohort (1 Some concerns, 1 High, 1 Very high) |

Potential reduced risk of type 1 diabetes in children 18 years and younger associated with breastfeeding. | |

| Rapid weight gain and growth | 3 ESRs (k = 20) (2 Moderate, 1 Low) |

14 cohort (6 Some concerns, 4 High, 4 Very high) |

Potential lower risk of accelerated growth and rapid weight gain in infancy and early childhood associated with breastfeeding. | |

| Cardiovascular outcomes | 2 ESRs (k = 35) (2 Low) |

14 cohort (4 Some concerns, 10 High) |

Potential reductions in SBP associated with breastfeeding, no clear association for DBP. No clear association between breastfeeding and blood lipid levels or arterial stiffness. Insufficient evidence for CVD endpoint outcomes. | |

| Infant mortality, including SUID | 2 ESRs (k = 18) (2 Moderate) |

2 case-control, 4 cohort (5 High, 1 Very high) |

Potential reduced risk of infant mortality associated with breastfeeding initiation, including risk of late-neonatal mortality and SUID. | |

| Moderate SOE for no association | Cognitive development | 1 ESR (k = 84) (1 Low) |

26 cohort (14 Some concerns, 10 High, 2 Very high) |

No association between breastfeeding and cognitive ability at any age. |

| Low SOE for no association | Atopic dermatitis | 3 ESRs (k = 27) (2 High, 1 Low) |

9 cohort (4 Some concerns, 4 High, 1 Very high) |

No clear association between breastfeeding and the risk of atopic dermatitis at any age. |

| Celiac disease | 2 ESRs (k = 30) (1 Moderate, 1 Low) |

1 cohort (1 High) |

No clear association between breastfeeding and risk of celiac disease. |

| Moderate SOE for increased risk | Dental caries | 1 ESR (k = 31) (1 High) |

2 cohort (1 Low risk, 1 Some concerns) |

Increased risk of dental caries associated with breastfeeding 12 months or longer. Pooled analyses showed an approximately 54% increased risk of caries when breastfeeding for 12 months or longer versus less than 12 months. |

| Insufficient SOE | Food allergy | 2 ESRs (k = 7) (1 High, 1 Low) |

10 cohort (4 Some concerns, 5 High, 1 Very high) |

Insufficient evidence to draw a conclusion on the association between breastfeeding and the risk of food allergies. |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2 ESRs (k = 2) (2 Low) |

4 cohort (2 Some concerns, 2 High) |

Insufficient evidence to draw a conclusion on the association between breastfeeding and risk of type 2 diabetes and intermediate diabetes outcomes at any age. |

a Credibility of ESRs was assessed using an adapted version of the AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) tool13,14 (Full Report Appendix D, Table D-1). Overall credibility was rated as: high (zero or one non-critical weakness), moderate (more than one non-critical weakness), low (one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses or more than one non-critical weakness), or critically low (more than one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses).

b Risk of bias was assessed using adapted versions of the ROBINS-E (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Exposures) tool17,18 or the Newcastle Ottawa Scale for Case Control Studies17 (Full Report Appendix D, Tables D-2 and D-3). Overall risk of bias was rated as low, some concerns, high, or very high risk of bias.

NOTE: CVD = cardiovascular disease; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; ESR = existing systemic review; GI = gastrointestinal; ROB = risk of bias; SBP = systolic blood pressure; SOE = strength of evidence; SUID = sudden unexpected infant death; vs = versus.

SOURCE: Patnode et al., 2025.

HOW BREASTFEEDING WORKS

Breastfeeding is a part of the evolutionary adaptations that play a role in ensuring human survival and ongoing health (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023; Quinn et al., 2023). Human infants are born in a highly immature state and experience a long period of postnatal maturation that corresponds with longer brain development compared to other primate species (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023). They are particularly vulnerable and cannot survive on their own (Rosenberg, 2021; Rosenberg & Trevathan, 2016). In addition, unlike other primates, human infants are unable to cling to their mothers and must be carried. They are highly dependent on physiological coregulation. Close proximity and frequent breastfeeding help to meet human infants’ nutritional and hydration needs as well as regulate their temperature, breathing, and heart rate (Tomori et al., 2022). The positive health outcomes associated with breastfeeding noted above have long-standing effects that outlast the time frame of breastfeeding and change the life course of the human infant (Meek et al., 2020). In addition to the positive associations with health, breastfeeding may provide psychosocial benefits to the breastfeeding dyad, including opportunities for emotional bonding and the potential to regulate stress and mood (e.g., Alimi et al., 2022; Feltner et al., 2018).

Human milk production is the result of a neuroendocrinological regulated supply–demand process driven by the suckling frequency, duration, and strength of the infant (Geddes et al., 2021). When the infant suckles from the breast, nipple stimulation triggers neural impulses that signal the mother’s hypothalamus to release prolactin-releasing hormone, which then stimulates prolactin release from the anterior pituitary gland and other hormones that are needed for milk synthesis in the mammary gland. The maternal hypothalamus serves a critical regulatory role for prolactin release because it also synthesizes dopamine, which, when released to the anterior pituitary gland, will inhibit prolactin release. In contrast when dopamine levels are lowered, as with certain medications or tumors, increased prolactin secretion results and may lead to overproduction or galactorrhea.

Nipple stimulation also signals the maternal posterior pituitary gland to release oxytocin, which is made in the maternal hypothalamus and stored in the posterior pituitary gland to be released into the maternal bloodstream. Once oxytocin reaches the mammary gland, the gland “squeezes” the myoepithelial cells surrounding the alveoli grape-like structures that contain the epithelial lactocytes where breastmilk is synthesized (Geddes et al., 2021). The squeezing of the myoepithelial cells is what allows the breastmilk to be ejected from the lactocytes into the milk ducts that converge in the nipple to feed the baby (Geddes et al., 2021). When the breasts are not drained, the maternal organism accumulates a substance, sometimes known as the feedback inhibitor of lactation, that slows down milk production in the mammary gland; this is called the autocrine control of milk production.

Thus, any interference with breastfeeding on cue, whether through caregiver-imposed nursing schedules or introduction of foods/fluids other than breastmilk, can interfere with milk establishment and maintenance (Geddes et al., 2021; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2019, 2023). It is therefore crucial for mothers to breastfeed effectively by having their infants remove the milk from their breasts, or to express milk via another means such as a breast pump, to maintain milk production (Geddes et al., 2021).

Moreover, interactions between the breastfeeding dyad, in the context of their environment, provide the feedback mechanism that shapes the varying composition of milk over the course of the day and over the development of the child (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023). These interactions also play a crucial role in psychosocial development and maternal well-being. For example, oxytocin, a neuropeptide, may be inhibited by stress responses, such as release of corticosteroids or conditions of chronic stress, while at the same time, oxytocin has been found to modulate stress responses and may be in part the mechanism for decreased anxiety, improvement of maternal mental health, and increased ability to socially bond during breastfeeding (Hantsoo et al., 2023; Olff et al., 2013). Thus, while human milk is itself a complex system, it needs to be examined in the context of the broader breastfeeding relationship (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023; Quinn et al., 2023).

BREASTFEEDING ACROSS THE LIFE COURSE

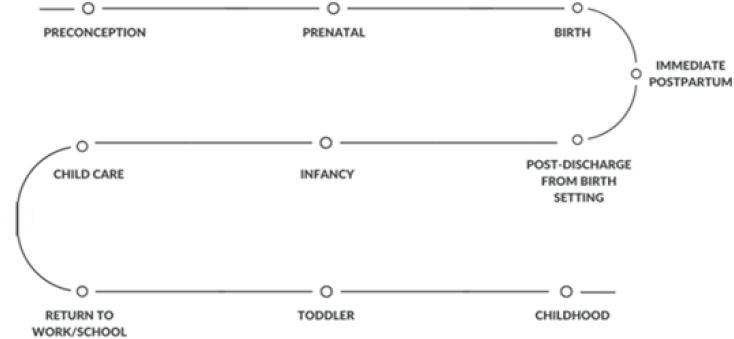

Part of the committee’s task was to explore contributing factors that impact breastfeeding rates and access to breastfeeding services and supplies. To address this, the committee developed its report using a life course framework in recognition that various exposures across different stages of life can influence future chronic disease risk and other health outcomes (Lynch & Smith, 2005). This framework identifies multiple determinants (i.e., exposures) that may influence individual and community health, including biological and genetic, behavioral, economic, and social factors (Halfon & Hochstein, 2002; see also Chapter 3 for the influence of social ecological factors on breastfeeding differences). In the case of lactation and breastfeeding, an infant and mother’s health trajectories are influenced by exposure to both risk and protective factors, as well as the infant and the mothers early life experiences, which can then influence breastfeeding and associated health outcomes at the population level. With this understanding in mind, the committee recognizes that the breastfeeding dyad progresses through a lactation journey, from preconception to birth to postpartum, return to school and work, and infancy, amid these intersecting influences. The committee identified critical inflection points across the life course that are specific to human lactation, breastfeeding, and the provision of human milk (Figure 2-1). Each of these inflection points presents both challenges

and opportunities. Interventions at these points can create an enabling environment for breastfeeding that provides the best opportunities for women and families to achieve their personal breastfeeding goals. Such interventions can also improve national breastfeeding rates.

This journey map begins with the mother at preconception, then follows her and her infant prenatally, at birth, immediately postpartum, and post-discharge from a birth setting. It continues for both the mother and infant, and identifies critical time points that impact both, including securing childcare and returning to work or school; it includes ongoing child development milestones from toddler to childhood. Protective and risk factors are described by inflection or time point, and additional considerations are presented for the sick or vulnerable breastfeeding dyad.

Preconception

Research demonstrates the importance of fetal health and parents’ preconception health on a child’s health (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2019, p. 25466, 2024, p. 27835; Schrott et al., 2022). Recognizing the genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors that affect health risks for the next generation (Cheng et al., 2016; Hanson & Gluckman, 2014), a growing body of literature documents the intergenerational transmission of health and disease and trans-generational effects of social and environmental exposures and epigenetics on health (Benincasa et al., 2024; Breton et al., 2021; Kioumourtzoglou et al., 2018; Scorza et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2024). As such, the life course perspective prompts consideration of the health of the breastfeeding dyad today, the adults the current infants will become, and the new families they will create.

Opportunities to discuss breastfeeding begin before pregnancy. Education about the importance of breastfeeding for infants and mothers, its value for communities and society, and the developmental stages of breast development can be started in schools or at adolescent health care visits during pubertal changes (Jack et al., 2024). However, education curriculum and studies on their implementation are limited.

Well-women visits during childbearing years, which contain a breast evaluation, present an opportunity to discuss future reproductive plans and the importance of lactation and breastfeeding for a woman’s health and the health of the baby, as well as opportunities for breastfeeding support, supplies, and counseling covered by the Affordable Care Act, if this is needed in the future (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2025).

Prenatal

For the mother, the process of human lactation includes distinct phases and begins during pregnancy (i.e. “lactogenesis stage I”; Geddes et al., 2021). In the first lactation phase, during pregnancy, the mammary glands are stimulated in preparation for breastfeeding the infant at birth. During this time, the placenta produces hormones responsible for the continued growth and differentiation of the tissue of the mammary gland, and the ductal system within the breast expands and branches in response to estrogen (Alex et al., 2020; Lawrence & Lawrence, 2021; Sriraman, 2017). During the prenatal period, progesterone is highly elevated and suppresses, to a large extent, the capacity of the mammary glands to secrete milk.

The prenatal period is a critical time for women to be provided health promotion strategies, including primary and secondary prevention through screening and management of risk factors (see Chapter 6) and related health conditions to promote and sustain a healthy pregnancy, birth, and breastfeeding journey (Howell, 2018). Known maternal or fetal conditions that may impact breastfeeding can also be identified during the prenatal period and appropriate can be counseling provided (Spatz et al., 2024; Stuebe, 2020). Some factors that may put a mother at risk for not meeting her personal breastfeeding goals include anatomic variations of the breast (Cruz & Korchin, 2007, 2010; Neifert et al., 1985; Stuebe et al., 2014), substance use disorders (Harris et al., 2023), mental health conditions (Buck et al., 2018; Dugat et al., 2019; Eagen-Torkko et al., 2017; Kitsantas et al., 2019; Martin-de-Las Heras et al., 2019; Miller-Graff et al., 2018; Wallenborn et al., 2018), diabetes (Mitanchez et al., 2015), and both high and low maternal body mass index (Chapman & Pérez-Escamilla, 1999; Chen et al., 2020; Garcia et al., 2016; Nommsen-Rivers et al., 2022).

Chronic disease prevalence among childbearing women is rising in the United States. From 2005 to 2014, the proportion of women who gave birth with at least one chronic condition increased from 6.7% to 9.2%, with Admon et al. (2017) reporting the highest rates among women living in rural or low-income zip codes and women insured by Medicaid. Some women with chronic health conditions, such as hypertension, endocrine and metabolic diseases, and obesity, for example, may face specific risk factors that make breastfeeding more challenging without additional or specialized clinical lactation support (Arenas et al., 2025; Stuebe, 2022). The management of these conditions may need to be tailored to accommodate the physical and metabolic demands of lactation. These conditions can influence lactation, and in turn, may also be affected by the act of breastfeeding itself (Stuebe, 2022).

Existing evidence-based and supportive policies, as well as best practices in the field, can mitigate these risk factors and support mothers as they prepare to breastfeed their infants (Jack et al., 2024). For example, systematic reviews demonstrate that women who receive breastfeeding prenatal education in health care offices have higher rates of initiation and duration, and are more likely to exclusively breastfeed; this is shown to be particularly effective when education is paired with postpartum support (Kehinde et al., 2023; Olufunlayo et al., 2019; Patnode et al., 2016; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023; Rollins et al., 2016; Tomori et al., 2022).

Jack et al. (2024) concluded that prenatal education is most effective and has the greatest impact on breastfeeding outcomes when guidance is focused on the benefits of breastfeeding on infant and maternal health, as well as practices and problem-solving to support early initiation of breastfeeding. In addition, domestic and international evidence demonstrates that educational programs are most effective when they promote breastfeeding self-efficacy in a structured format (Admasu et al., 2022; Araban et al., 2018; Behera & Kumar, 2015; Cangöl & Şahin, 2017; Fauzia et al., 2020; Galipeau et al., 2018; Mizrak et al., 2017; Modi et al., 2019; Öztürk et al., 2022; Sabancı Baransel et al., 2023; You et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021).

In addition, evidence demonstrates that midwives, lactation consultants, other lactation support providers, and doulas can positively affect breastfeeding initiation and duration, particularly in low-income, racially minoritized communities (see Chapters 3 and 6; Bonuck et al., 2014; Hartman et al., 2012; Kehinde et al., 2023; Louis-Jacques et al., 2020; Reno, 2018). Research also shows that support from peer counselors and community health workers during the prenatal period is effective in improving breastfeeding outcomes in community-based settings (Khatib et al., 2023; Louis-Jacques et al., 2020; Reno, 2018; Sobczak et al., 2023; see also Chapter 3).

Birth

Following birth and delivery of the placenta, the sharp decline in progesterone triggers secretory activation of the mammary glands (Geddes et al., 2021; Pérez-Escamilla & Chapman, 2001). This stage of lactation, still considered to be part of lactogenesis stage I, involves the secretion of strongly immune-active colostrum, or first milk, in small amounts (Geddes et al., 2021; Pérez-Escamilla & Chapman, 2001). The conditions and supports available during childbirth can set the stage for early breastfeeding. Andrew et al. (2022) reported that breastfeeding outcomes are better for women who have uncomplicated, full term, vaginal births of vigorous, healthy babies.

Protective and Risk Factors

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (ABM) has identified several characteristics of the birth experience and process that can be either protective or risk factors for breastfeeding (Holmes et al., 2013). For example, during labor and delivery, the continuous presence of a close companion, such as a spouse, partner, or other family member, is beneficial for the mother (Holmes et al., 2013). In addition, Kozhimannil et al. (2013) reported that the presence of a doula is associated with increased initiation and duration of breastfeeding and may mitigate risk factors associated with early cessation of breastfeeding, including surgical and pain-reducing interventions (see also Hodnett et al., 2013; Mottl-Santiago et al., 2008; Nommsen-Rivers et al., 2009). Risk factors for not initiating breastfeeding include birth complications and associated interventions, such as intrapartum analgesia, exogenous oxytocin, and ergometrine (Holmes et al., 2013; see also Beilin et al., 2005; Gizzo et al., 2012; Jordan et al., 2009; Montgomery et al., 2012).

Regarding birth attendants and settings, Vedam et al. (2018) found breastfeeding rates to be higher in states with laws and regulations that support midwifery integration in care. A National Academies committee examining maternal and newborn care in the United States found consistent correlations between birth setting and breastfeeding rates, with low-risk home and birth center deliveries associated with higher rates of breastfeeding initiation and exclusive breastfeeding 6–8 weeks after birth (National Academies, 2020). Less than 1% of women give birth at home and 0.52% in free-standing birth centers (MacDorman & Declercq, 2019). While the report acknowledges that variation in breastfeeding outcomes by birth setting is at least partially attributable to selection bias, as individuals choosing home or birth center births are often highly committed to breastfeeding, the report also suggests that the “wellness-oriented, individualized,

relationship-centered approach of midwifery care across home, birth center, and hospital settings” is a contributing factor for differential outcomes (National Academies, 2020, p. 207). Interestingly, Gregory et al. (2021), analyzed data from the National Vital Statistics System and reported an increase in home births during the COVID-19 pandemic. They report that in 2020, the rate of home births increased by 19% (Gregory et al., 2021) and interest in home birth searches spiked significantly after declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic occurred (Cheng et al., 2022).

Complicated Deliveries

In the United States, 31.8% of women underwent induction of labor in 2020 (Simpson, 2022), and 32.3% birthed by C-section in 2023 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2025).

A population-based study in Australia of infants born at or before 37 weeks found that interventions in labor, such as C-section, epidural anesthesia, and infusion of oxytocin, were associated with higher rates of formula supplementation in the hospital and lower rates of breastfeeding at three and six months postpartum (Andrew et al., 2022). Of note, this study did not include information on maternal health conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension, that can both require induction of labor and affect breastfeeding outcomes.

More difficult labors are associated with early breastfeeding difficulties. In a study among low-risk mothers in northern California (Dewey et al., 2003), longer labor and longer intervals without sleep were associated with later onset of lactogenesis II, the transition from colostrum to milk production. In adjusted models, stage II of labor longer than one hour was associated with delayed onset of milk production and suboptimal infant breastfeeding behavior. As noted above, support from companions and doulas may help mitigate against some of these risk factors (Kozhimannil et al., 2013).

Cesarean birth is associated with lower rates of early initiation of breastfeeding; exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge; and exclusive breastfeeding at one, three, and six months postpartum (Ulfa et al., 2023). Promising practices for improving maternal experience and breastfeeding outcomes following cesarean birth include additional support (Beake et al., 2017) and skin-to-skin care in the operating room following C-section (Frederick et al., 2020).

As previously mentioned, postpartum hemorrhage is a leading cause of maternal morbidity, and higher blood loss at delivery is associated with lower rates of fully breastfeeding in the first postpartum week and at both two and four months postpartum (ACOG, 2017; Del Ciampo & Del Ciampo, 2018; Thompson et al., 2010; Victora et al., 2016). U.S. birth

certificate data from 2016 to 2023 shows an association between maternal transfusion and lower rates of breastfeeding at discharge (69.9% vs. 74.8%). An analysis of the ARRIVE trial conducted by Roberts et al. (2025) found that postpartum hemorrhage with transfusion was associated with lower odds of exclusive or any breastfeeding at 4–8 weeks postpartum. For example, a cohort study of women with postpartum hemorrhage, defined as more than 1500 mL of blood loss, found that higher blood loss and longer delays in initiation predicted lower full breastfeeding rates at one week postpartum (Thompson et al., 2010). Additional lactation support in the intrapartum period and beyond have been recommended to address breastfeeding challenges among those experiencing postpartum hemorrhage (Roig et al., 2024; Thompson et al., 2010).

In summary, more difficult labor, C-section, and heavy bleeding after birth predict more breastfeeding difficulties and earlier weaning. Judicious use of interventions in labor, as well as opportunities for early skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding initiation, and more support for breastfeeding dyads with difficult births, can help more women achieve their infant feeding goals. Chapter 6 describes best practices for clinicians and health care systems to support the breastfeeding dyad in the ambulatory or hospital setting.

Immediate Postpartum

Lactogenesis stage II, or the secretory stage, begins around 48–72 hours after birth, with the onset of lactation or coming to volume. In this stage, more copious amounts of milk secretion begin, although there is wide variability among women (Geddes et al., 2021; Pérez-Escamilla & Chapman, 2001).

Risk and Protective Factors

Postpartum care provides an opportunity to identify and potentially mitigate additional birth- and neonatal-related risk factors for inadequate milk production, delay in the secretory stage, and early breastfeeding cessation. These risk factors include

- low birth weight,

- lower gestational age,

- stressful or prolonged labor and birth,

- unscheduled C-section,

- postpartum hemorrhage,

- delayed first breastfeeding episode,

- breastfeeding or pumping fewer than eight times in 24 hours,

- formula supplementation within the first 48 hours, and

- separation of the dyad at birth.

(See Brown & Jordan, 2013; Chapman & Pérez-Escamilla, 1999, 2012; Dewey et al., 2003; Furman et al., 2002; Grajeda & Pérez-Escamilla, 2002; Hobbs et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2020; McCoy & Heggie, 2020; Meier et al., 2017; Parker et al., 2021; Salariya et al., 1978; Scheeren et al., 2022; Thompson et al., 2010).

A significant number of women experience a delayed onset of lactation (>72 hours after birth), which is a risk factor for shorter exclusive and any breastfeeding durations (Feldman-Winter et al., 2020; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2019). This is especially the case for mothers of preterm or critically ill infants requiring specialized care in neonatal intensive care units (Hoban et al., 2018; Juntereal, 2024; Mago-Shah et al., 2023; Parker et al., 2021). However, many factors associated with delayed lactation can be prevented or mitigated.

Rooming In

During the hospital stay, mother–infant rooming-in on a 24-hour basis is associated with optimal breastfeeding initiation (Holmes et al., 2013). Health care providers may need to assist mothers with positioning and attaching their babies at the breast, and those who delivered by C-section may need additional help to attain comfortable positioning. Holmes et al. (2013) recommend that at least once every 8–12 hours after delivery a trained lactation support provider assess and document breastfeeding effectiveness until the breastfeeding dyad is discharged. This clinical protocol notes that “peripartum care of the dyad should address and document infant positioning, latch, milk transfer, baby’s weight, clinical jaundice, and any problems raised by the mother, such as nipple pain or the perception of an inadequate breastmilk supply” (Holmes et al., 2013, p. 270; see also Feldman-Winter et al., 2020).

Today, rooming in is the predominate norm in hospital settings (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2024; see Chapter 6). However, the CDC (2024) reports that early separation remains a practice in 10% of hospitals, and 16% of hospitals have not implemented rooming in. Flacking et al. (2012) noted that infants who are preterm or require additional care may face more significant separation while they are cared for by a pediatric team; the mother may be recovering in the postpartum unit or discharged while the infant is still hospitalized. For neonatal intensive care, family-centered, single-family room design is an opportunity to ensure that mothers and infants are kept together, facilitating more connected models of care, better breastfeeding outcomes, and better outcomes for parents (e.g., European Standards of Care for Newborn Health, 2019; van Veenendaal et al., 2019, 2020). While promising, and although efforts to maintain proximity in the neonatal intensive care unit have increased, the committee notes that the United States has not yet adopted models of family-centered, single-family room design on a large scale.

Skin-to-Skin Care

The ABM advises that healthy newborns should be given directly to the mother for skin-to-skin contact until after the first feeding. The infant may be dried and assigned Apgar scores, and the initial physical assessment may be performed as the infant is placed with the mother. [. . .] Delaying procedures such as weighing, measuring, administering eye prophylaxis as well as vitamin K, up to six hours after birth, and the initial bath enhances early parent–infant interaction. Infants are to be put close to the breast, as soon after birth as is feasible for both mother and infant, to allow for a latch and feeding, ideally within an hour of birth. (Holmes et al., 2013, p. 470)

There is substantial evidence that early skin-to-skin contact facilitates early breastfeeding initiation and is associated with increased duration of any and exclusive breastfeeding (see Bramson et al. 2010; DiGirolamo et al., 2008; Hung & Berg, 2011; Mahmood et al., 2011; Mikiel-Kostyra et al., 2002; Moore et al., 2016; Murray et al., 2007; Thukral et al., 2012).

Uninterrupted skin-to-skin care immediately following birth improves breastfeeding outcomes. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by Moore et al. (2016) found that placing infants with the mother skin to skin for the first 60–90 minutes following birth increased breastfeeding duration by 64 days. In addition, skin-to-skin care and early initiation of breastfeeding are a core tenet of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund, 2018). The AAP has delineated key aspects of safe implementation of skin-to-skin care in the delivery setting, including continual observational monitoring by trained staff so that sudden changes to maternal or newborn status can be addressed immediately (Feldman-Winter et al., 2016). In addition, CDC monitors hospital implementation of skin-to-skin care as part of the Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC) Survey (see Chapter 4 for additional surveillance measures).

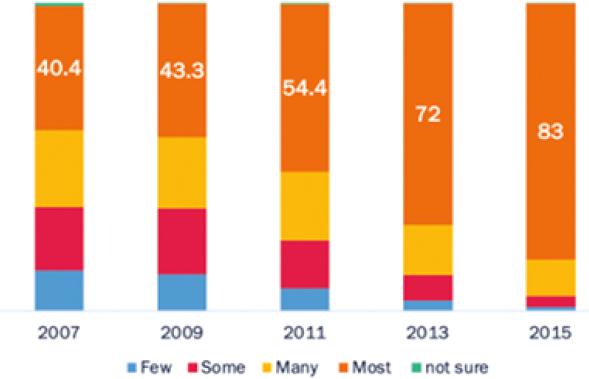

In 2007, 40.4% of hospitals reported that most patients experienced mother–infant skin-to-skin contact for at least 30 minutes within one hour of an uncomplicated vaginal birth (see Figure 2-2). The prevalence of this practice increased to 83% in 2015 (Boundy et al., 2022). After 2017, mPINC revised the survey to assess skin-to-skin contact for at least one hour after vaginal birth; on the most recent survey, 70% of hospitals reported that this was their standard of care (Boundy et al., 2022).

Severe Maternal Morbidity

Mothers experiencing severe maternal morbidity require interdisciplinary care to address acute, life-threatening conditions (Bingham et al., 2011). Severe maternal morbidity and mortality is a composite measure of 20 unexpected outcomes of labor and delivery, quantified using maternal

SOURCE: Adapted from Boundy et al., 2018.

diagnosis codes from the birth hospitalization. Rates of severe maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States have continued to rise. According to Reid (2024), rates increased 40% overall from 2016 to 2021 and by 20% when excluding delivery stays with COVID-19.

Often, a mother with severe maternal morbidity is transferred from maternity care to an intensive care unit (ICU), where she is separated from her infant and may be intubated or sedated. This separation can present challenges for breastfeeding (Bartick et al., 2021). ICU staff may not be familiar with lactation physiology and may require assistance to express milk to prevent engorgement and/or mastitis. By regularly expressing milk until the mother is awake and alert, the critical care team can protect her right to decide whether to breastfeed her infant. Facilitating breastfeeding can be an important part of easing the psychological trauma of a maternal ICU admission (Hinton et al., 2015; Intensive Care Society, 2018).

Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine guidelines on supporting breastfeeding for hospitalized mothers include allowing the infant to room in with the mother, providing equipment for milk expression, and ensuring that the care team has access to evidence-based information on medications in lactation (Bartick et al., 2021).

Infant Loss

When a mother is pregnant, her body is typically biologically prepared to lactate. Secretory differentiation begins in the second trimester with

lactogenesis stage I. Thus, even if a mother experiences a second trimester pregnancy loss, an intrauterine fetal death, or the death of a child immediately post birth, the physiologic process of lactation will occur normally (Carroll et al., 2020). With the delivery of the placenta and the associated hormonal impact, the body will likely begin converting to lactogenesis stage II. This process of secretory activation will occur even without an infant suckling at the breast.

Hospitals or birth settings may not adequately prepare mothers for this experience and how to navigate these physical symptoms and suppress lactation (see Britz & Henry, 2013; Carroll et al., 2020; Redshaw et al., 2014). Carroll et al. (2020) described examples of advice and techniques for milk suppression, including nonpharmacological means to relieve symptoms, as well as pharmacological pain relief options. In addition, they present a framework based on supporting evidence for online health information, including acknowledging lactation after infant loss, describing breast changes associated with the production of human milk, advice on alleviating symptoms, suppression options, and sustained milk expression options (Caroll et al., 2020).

Not all families may wish to suppress lactation following a pregnancy loss or death of a child. For example, some mothers may wish to initiate milk expression after a second trimester loss, an intrauterine fetal demise, or immediate death of a child, as part of the grieving process (Paraszczuk et al., 2022). Cole et al. (2018) found that parents are not generally given information about milk donation and navigating the grief journey and the lactation journey following a loss. Families may need to determine how to get a breast pump, as insurance may not provide one if there is not a living child. Because of the challenges that bereaved parents may go through to continue their lactation journeys, additional research in this population would be helpful to better support families’ differing experiences.

Inducing Lactation

Some parents may desire to induce lactation even in the absence of a pregnancy. Inducing lactation, though possible for some nonbirth parents, requires significant time, effort, and financial investment, in addition to the desire and commitment to make it possible. Parents must plan far in advance and seek out support from qualified medical professionals. Those who are inducing lactation need medication and technology to support their lactation journey. A scoping review found limited evidence regarding how best to induce lactation (Cazorla-Ortiz et al., 2020). The ABM provides recommendations for nonbirth parents who wish to induce lactation, as well as an overview of the use of galactagogues in initiating or augmenting maternal milk production (Brodribb & ABM, 2018; Ferri et al., 2020).

Additional Considerations for the Sick or Vulnerable Infant

About 7.5% of infants are hospitalized in the first year of life (Weiss et al., 2022), most commonly for acute respiratory conditions. Although hospitalization can disrupt breastfeeding, interventions to promote ongoing lactation and ensure evidence-based staff support can reduce unwanted weaning (Ben Gueriba et al., 2021). Moreover, pediatric critical care units can develop breastfeeding and breastmilk storage policies to support the breastfeeding dyad (Bartick et al., 2021).

Breastfeeding medically complex children presents multiple challenges. In a narrative synthesis, Hookway et al. (2021) reported that when an infant is hospitalized, mothers must navigate the logistics of expressing, storing, and delivering milk, as well as the psychological stress of separation and anxiety. The infant’s acute condition can affect their ability to feed, as can an underlying chronic condition. Lack of specialized breastfeeding support, inadequate knowledge of health team members, and uneven access to specialized equipment were additional barriers identified by the authors (Hookway et al., 2021). There are multiple levels of neonatal care, and the availability of breastfeeding support and donor human milk4 varies by level (Anstey et al., 2024).

Donor Human Milk

In the United States, donor human milk is primarily regulated through nonprofit milk banks that follow strict safety guidelines. Human Milk Banking Association of North America (HMBANA) is a not-for-profit milk bank that provides standards for donor human milk banking. For example, potential donors may undergo health screenings, and donated milk is pasteurized and tested for contaminants. Most donor human milk is provided to preterm and critically ill infants who are in the hospital NICU. Currently, demand for donor human milk exceeds the available supply in the United States (see Bai & Kuscin, 2021; Hamilton & Middlestadt, 2024). In 2024, HMBANA-affiliated milk banks dispensed 11 million ounces of pasteurized donor human milk, a 10% increase from 2023 (Human Milk Banking

___________________

4 Donor human milk is pasteurized human milk provided by lactating parents who donate their surplus milk to milk banks. It is primarily used for medically fragile infants, especially preterm babies in NICUs, when a mother’s own milk is unavailable or insufficient. As described earlier in the chapter, donor human milk confers protection from necrotizing enterocolitis, a life-threatening condition, to preterm infants. At the time of this report, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2018) advises against informal milk sharing; however, the practice continues in the United States (Bressler et al., 2020; Martino & Spatz, 2014; McNally & Spatz, 2020; Spatz, 2016). Health care providers can help parents make informed decisions, informed by position statements and guidance from the ABM and the American Academy of Nursing and Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (Sriraman et al., 2018).

Association of North America, 2025). State Medicaid programs and other insurers may pay for donor human milk when medically necessary.

It is important to note that donor milk is not a replacement for a mother’s own milk but can serve as a bridge to allow milk supply to be established, if the parent is able to lactate. Encouraging direct breastfeeding before discharge from the NICU may help prolong breastfeeding duration. As discharge approaches, health care providers must decide on the most suitable post-discharge feeding plan to ensure continued nutrition and support for the infant (Noble et al., 2018).

Post-Discharge from Birth Setting

The management of lactation during the first few weeks postpartum is essential for establishing a milk supply (Institute of Medicine, 1991). Through a biologically complex process, women increase their human milk production to about 750 millileters daily on average by three months after birth (Geddes et al., 2021). Most women with multiple births have the capacity to produce enough milk for all their offspring (Flidel-Rimo & Shinwell, 2006), highlighting the enormous plasticity of the human lactation process.

The ABM recommends that breastfed infants see a health care provider within 24–72 hours following discharge from the hospital or at 3–5 days old to assess the infant’s well-being and whether breastfeeding has been established successfully (Holmes et al., 2013; see also Committee on Fetus and Newborn, 2010; Hoyt-Austin et al., 2022; Labarere et al., 2005; Section on Breastfeeding, 2012).

However, reflecting the current fragmentation of care and the need for coordination, most mothers in the United States receive postpartum care from an obstetrician, family physician, midwife, or nurse practitioner, while their infant is cared for by a pediatrician who works in a different office, which may use a different electronic health record system. This can create challenges for the breastfeeding dyad. Lactation is a complex, two-person biosocial system, ultimately involving maternal milk production and infant milk extraction and ingestion usually through close bodily interaction (see Chapter 6).

Lactation problems post-discharge from the birth hospital are common and often reflect the challenges and structural barriers to lactation encountered within the health care system (see Chapter 6). This may result in problem-oriented visits to a doctor or a lactation support professional who may inappropriately recommend supplementation or weaning—outcomes that can often be prevented with effective care. Effective management by a mother’s physician, advanced practice professional, or lactation support provider is necessary to protect breastfeeding, especially exclusive breastfeeding. Currently, no universal structure supports payment of lactation care for problem-oriented visits if they are not provided by a physician

or advanced practice professional. Some, but not all, insurance companies reimburse a certain number of visits to lactation consultants; only certain states offer Medicaid payment for lactation consultants (see Chapter 7).

During the first two weeks after birth, breastfeeding 8–12 times during a 24-hour period is associated with establishment of adequate milk production (Geddes et al., 2021; Hill et al., 2005). However, infants usually feed more frequently than this; close contact with frequent opportunities to breastfeed also helps establish successful breastfeeding (Zimmerman et al., 2023). Additionally, peer support has been found to promote breastfeeding success (Holmes et al., 2013; Renfrew et al., 2012; Sudfeld et al., 2012; see Chapter 3).

ACOG examined factors that can interfere with women achieving their breastfeeding goals (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2021). One factor that can lead to early and undesired weaning includes nipple injury or persistent pain during breastfeeding. There are many possible contributors to pain during breastfeeding, and obstetrician-gynecologists or other obstetric care professionals that women see for post-birth care can play an important role in diagnosing and treating the causes of pain to foster continued breastfeeding (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2021). As pain during breastfeeding can be associated with postpartum depression, screening for postpartum depression is an important component of assessment for these patients (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2021; see also ACOG, 2016; Amir, 1996; Watkins et al., 2011).

Self-reported insufficient milk supply is another risk factor for early weaning (Segura-Pérez et al., 2022). For mothers concerned about having adequate milk supply, providers and clinicians need to evaluate whether underlying physiologic or psychosocial issues are contributing to the perception of inadequate supply. Mothers can be reassured that indicators of adequate milk supply include feeding frequency of 8–12 times per day on average, steady weight gain after the infant is 4–5 days old, and an average of 6–8 wet diapers per day (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2021). Infants typically gain back normal post-birth weight loss by 10–14 days after birth; care providers need to alleviate mothers’ concerns that the infant being below their birth weight is an indicator of inadequate milk supply if the infant is not yet two weeks old. Clinicians can use standardized tools, such as the Newborn Weight Tool, to assess growth trajectories and take into consideration birth factors such as fluids administered to the mother before and during birth, and cesarean delivery, that may yield greater weight-loss patterns in infants (Flaherman et al., 2015). Also, feedings more frequent than 8–12 times per day are not necessarily an indicator of insufficient milk supply, as human milk is easily digested (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2021). When low milk supply occurs, supporting mothers in more frequent direct breastfeeding or milk expression (e.g., pumping) can often help to increase supply (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2021).

Infancy

A critical element of successful breastfeeding relates to the mother’s ability to interpret infant behavior and to respond to their child’s needs, which creates feedback loops of coordination between the dyad (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023). For instance, responding to babies’ need to be close and to be fed frequently simultaneously provides reassurance, soothing, and security, and is a major determinant of early breastfeeding success, which also plays a role in exclusive breastfeeding and breastfeeding duration (see Box 2-1).

BOX 2-1

Physiological Infant Care

Young infants require frequent contact and feedings day and night. This box provides a protocol for managing normal physiology for the breastfeeding dyad.

Normal Infant Feeding Patterns

Newborn infants breastfeed approximately 8–12 times per 24 hours; this does not always occur at regular intervals. Responsive feeding is advised, as feeding according to infant cues can ensure that they receive their needed daily nutrition. Infants can self-regulate their nutritional intake by nonnutritive and nutritive suckling. Continuous proximity and skin-to-skin contact with mothers or parents help with infant temperature, breathing, and heart rate regulation.

Normal Infant Sleep Patterns

Newborn infants are born without a functional circadian clock; melatonin passed through human milk can help establish an infant’s circadian rhythm, as can exposure to daytime activities and differentiating them from nighttime (e.g., avoiding artificially darkening rooms for daytime sleep). Expectations of prolonged infant sleep periods are unrealistic, and sleep training infants younger than six months of age can cause significant infant stress and parental distress, and it can impact breastfeeding because of the physical separation of a mother and her infant during the night. The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine’s protocol is focused on infant sleep patterns as they relate to breastfeeding, which may differ from existing American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations on sleep training.

Supporting Physiological Infant Care

At times, cultural expectations of typical infant behavior and normal physiology are misaligned. Strategies for reducing such misalignment may include addressing expectations that infants sleep through the night, or that solitary sleep without breastfeeding for infants is typical or desirable. In reality, infant sleep is fragmented and breastfeeding infants tend to sleep as well as or better than their formula-fed counterparts. Strategies that support this care and help mothers maximize their recovery, rest, and sleep, include support from fathers, partners, and family members; paid family and medical leave; and accessible and affordable child care.

SOURCE: Zimmerman et al., 2023.

Infants must be permitted to feed on cue, as limiting the time that an infant is at the breast can be detrimental to establishing adequate milk supply. Infants usually release the breast spontaneously or fall asleep when they are satiated (Holmes et al., 2013). Proper postnatal care can be protective for breastfeeding. As noted in Box 1-3, parental expectations of prolonged infant sleep periods may be unrealistic and can be a risk factor for breastfeeding success, particularly if such beliefs lead parents to engage in sleep training for infants younger than six months of age (Zimmerman et al., 2023).

As noted in the box above, community support plays a critical role in shaping breastfeeding success by influencing the environments in which families live, work, and seek care. While clinical and workplace supports are essential, community-based efforts help ensure that breastfeeding is normalized, socially supported, and practically feasible across diverse settings (e.g., Rhodes et al., 2024; see Chapter 4 for additional discussion).

Childcare

For many families, attempting to secure childcare before returning to work or school can produce increased feelings of stress and anxiety, as well as increased reporting of depressive symptoms (Armstrong et al., 2022; Ceballos et al., 2017; Heck, 2021; Laughlin, 2013). Previous research by Armstrong et al. (2022) and Beck (2001) has shown that access to childcare may help mitigate negative effects of sleep deprivation and childcare stress, and support maternal mental health. In a series developed for the Center for American Progress, Malik et al. (2018) reported that approximately 50% of Americans live in childcare deserts. The authors defined childcare desert as an area or community with an inadequate number of licensed childcare providers and facilities (Malik et al., 2018). Given the dearth of accessible and affordable childcare options, newly postpartum mothers and families may spend a large amount of time and resources trying to identify a childcare provider who best fits their infants and families’ needs.

Reliable and affordable childcare is critical for supporting breastfeeding outcomes, particularly as families navigate the postpartum period. Childcare plays a dual role: it supports children’s early development and enables parents to remain engaged in the workforce (Schneider & Gibbs, 2023). However, the high cost of care and financial instability of providers pose significant challenges (U.S. Department of Labor, 2024). Childcare settings can either support or hinder breastfeeding, depending on their practices. Breastfeeding-friendly environments that store and handle breastmilk safely, feed infants responsively, delay solid food until six months, communicate supportively, and provide lactation spaces for parents help

protect breastfeeding continuity. Conversely, when these elements are absent, families are at greater risk of not achieving their breastfeeding goals. Chapter 8 further examines the intersection of childcare and the return to work or school, a critical transition period for lactating parents.

Return to Work or School

Given the need for consistent contact between mothers and children to support and sustain breastfeeding journeys, the transition for women back to the workforce or school presents a significant challenge. In the United States, the absence of a national paid family leave policy means that many mothers return to work within weeks of giving birth (see Chapter 8).

Maternal employment has been identified as a structural determinant of infant feeding decisions across the globe (Baker et al., 2023; Perez-Escamilla et al., 2023). Low-wage workers experience more pronounced differences related to workplace accommodations and policies (California WIC Association, 2025).

The process of returning to work or school after pregnancy varies widely depending on individual circumstances, employer policies, and institutional support systems. For many, this transition requires flexibility and support to ensure a smooth adjustment to new routines.

Working mothers encounter distinct challenges in breastfeeding, resulting in lower rates of initiation and shorter durations than those for nonworking mothers (Chatterji & Frick, 2005; Duthei et al., 2021). These challenges persist despite evidence highlighting the health advantages of breastfeeding for both mother and child (see Chapter 1), as well as the diverse strategies available for supporting breastfeeding women in the workplace (e.g., Litwan et al., 2021).

Return to work or school can be a difficult experience for women, as they must learn to blend breastfeeding and/or pumping into the work or school environment (e.g., Gabriel et al., 2020; Little & Masterson, 2021). Many workplaces lack adequate facilities for expressing milk or policies that accommodate breastfeeding needs (Kozhimannil et al., 2016; Lowenfels et al., 2024). Health insurance and paid leave can significantly impact how a new parent manages their physical and mental health and financial well-being during pregnancy and postpartum. Additionally, understanding whether paid leave is available—and for how long—can make a significant difference in planning for the postpartum period and balancing work or educational obligations with caregiving responsibilities.

Given these challenges associated with reentering the workforce (or school), this period for working mothers has been described as an “emotional whirlwind” (Spiteri & Xuereb, 2012, p. 206) and dubbed

the fifth trimester (Brody, 2018), during which “the working mother is born” (Chawla et al., 2024, p. 2); she must navigate how her professional and caregiving (i.e., childcare, family) roles work together (i.e., enrich) or conflict (Gabriel et al., 2020). Working mothers may also be grappling with mental health challenges associated with motherhood, such as postpartum depression (Chawla et al., 2024; Gabriel et al., 2023), which can be compounded by difficulties transitioning back to school or work. Indeed, during this time, mothers who are employed may feel as though they are violating both “ideal worker norms” and “ideal mother norms,” not being fully available to either their work role or their motherhood role (Ladge et al., 2015; Little & Masterson et al., 2023).

Toddler

The Meek et al. (2022) and WHO (2023a) recommend continuing breastfeeding after introducing solid foods as long as mutually desired for up to two years or beyond (Meek et al., 2022). Protective factors for continuing breastfeeding into toddlerhood include flexibility to accommodate the toddler’s variable desire for breastfeeding, such as seeking more frequent feeding during times of stress or transition (e.g., La Leche League, 2020). Risk factors for earlier-than-desired weaning may include poor or inadequate support during birth and in the postnatal period, the demands of returning to work, as well as the influence of commercial milk formula and toddler milk marketing (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023). It may also result from disrupted lactation, which may be attributed to untreated risk factors (e.g., see Stuebe et al., 2014) or other structural influences.

Weaning can also be a personal decision, and it differs by mother and family (CDC, 2024). Children and parents may be ready to wean from breastfeeding at different times; some children gradually lose interest as they eat more solids, while others stop suddenly; parents’ readiness can vary as well. Weaning may be a gradual process, conducted with or before the introduction of complementary foods. Consultation with a health care provider is essential to ensure that a child’s nutritional needs are adequately met.

Childhood

Physical development related to lactation begins during childhood. One of the earliest signs is breast development, known as thelarche, which typically starts around ages 9–10 years but can begin as early as eight years (Geddes et al., 2021). This process includes increased pigmentation of the areola and the formation of a small mound of tissue under the nipple

called the breast bud. Breast development usually unfolds over a span of 3–3.5 years and begins approximately 1–2 years before the onset of menstruation (Geddes et al., 2021). During puberty, the mammary ducts begin to grow into the mammary fat pads. Once menstruation begins and ovulation occurs, the hormone progesterone stimulates some development of the lobuloalveolar structures (i.e., the milk-producing components of the breast). These alveolar clusters enlarge during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and regress at the start of menses (Geddes et al., 2021). This cyclical development lays the groundwork for the breast’s ability to produce milk in response to pregnancy and childbirth later in life.

Attitudes toward breastfeeding begin to form early in life, often during childhood. The 2003 WHO/United Nations Children’s Fund Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding highlighted the importance of engaging school aged children and adolescents to positively improve perceptions and raise awareness about breastfeeding (World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund, 2003). Children’s perceptions of infant feeding are shaped by what they observe in their homes, communities, and especially in media, where bottle feeding is often more visible than breastfeeding (see Chapter 4). These early exposures help establish what children view as “normal” or socially acceptable. As such, integrating breastfeeding into school-based education on human development, such as health or life sciences, can help promote more informed and positive attitudes toward breastfeeding (Angell et al., 2011). Educational efforts that include realistic portrayals of breastfeeding can also challenge stigma and reinforce the role of breastfeeding as a natural and beneficial practice. Broader sociocultural factors, including family norms, cultural beliefs, and public attitudes, further shape how individuals view and experience breastfeeding. For an in-depth discussion of these influences, see Brown (2018) and Tomori et al. (2018).

Adulthood

In adulthood, community-level and interpersonal influences affect an individual’s views about breastfeeding. As discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3, cultural influences, community attitudes, family norms, and traditions can influence the extent to which individuals hold a positive attitude toward breastfeeding (see also Brown, 2018; Quinn et al., 2023; Tomori et al., 2018). As described above, breastfeeding is associated with a reduced risk of mothers developing certain chronic diseases as well as improvements in postpartum recovery.

Conclusion 2-1: Human lactation is a multifaceted physiological process that is influenced by a range of factors operating across the life

course. The capacity to breastfeed, and the outcomes associated with breastfeeding, are determined by a combination of biocultural mechanisms and external factors, including clinical practices; health system structures; and social, structural, and environmental conditions experienced throughout an individual’s and family’s life. Preconception health, prenatal care, birth experience, postpartum recovery, and the return to work or school each represent critical windows in which the foundations for optimal breastfeeding can be laid.

There are numerous challenges to breastfeeding across the life course, but each inflection point identified above also presents opportunities to create an enabling environment for breastfeeding. The scientific literature reveals opportunities for timely and effective intervention or support. For example, prenatal breastfeeding education, continuity of lactation support providers, family-centered care at birth, paid leave, and supportive return-to-work or school policies have all been shown to increase breastfeeding initiation and duration (see Chapters 3, 6, 7, and 8). Special considerations are warranted for vulnerable breastfeeding dyads, including those affected by infant and maternal morbidity and mortality, as well as those pursuing induced lactation.

CURRENT STATUS OF BREASTFEEDING IN THE UNITED STATES

As noted in Chapter 1, the United States has been unable to meet the modest breastfeeding targets set by Healthy People 2030. This section presents data on breastfeeding initiation in the United States and trends in breastfeeding duration and exclusivity between 2014 and 2021. It then explores differences in breastfeeding by population group and discusses protective and risk factors across the life course. Chapter 3 focuses on structural determinants that influence these community-level differences, as well as historical shifts in the cultural perception of breastfeeding.

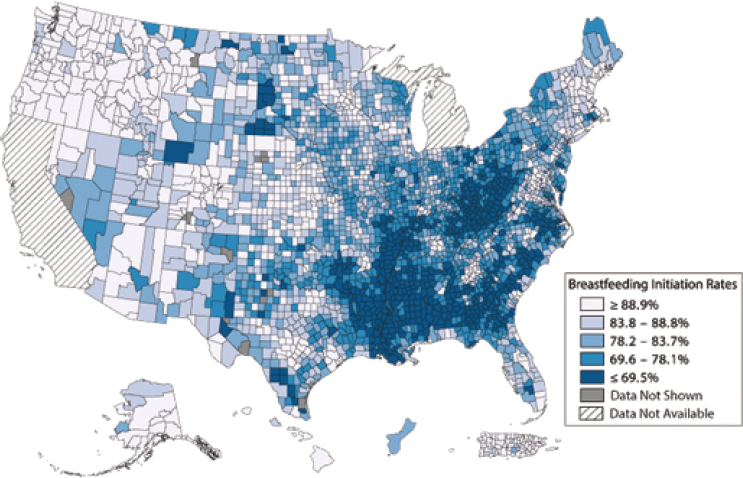

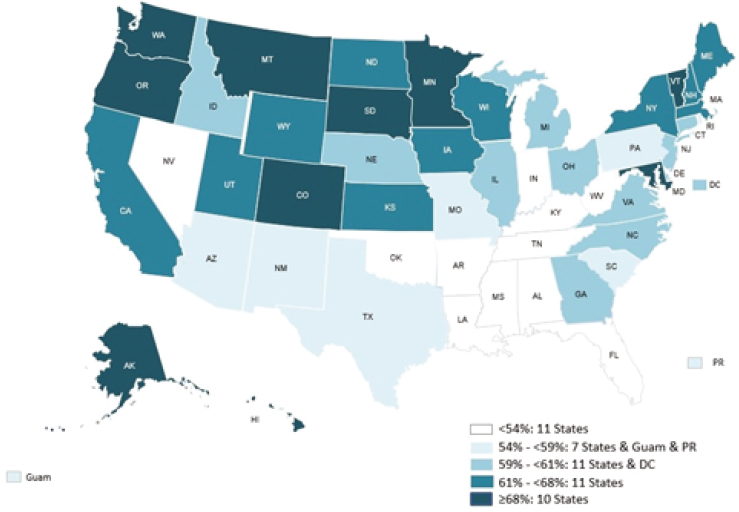

Breastfeeding Initiation

Breastfeeding initiation, or the percentage of live infants “receiving any breast milk or colostrum between delivery and discharge from the birth facility or birth certificate completion for home births,” varies by county and state, and ranges from 22% to 90% (CDC, 2024a, para. 3). The national average of breastfeeding initiation, using birth certificate data from the National Vital Statistic System (NVSS), is estimated to be 83.2% (CDC, 2022; see Figure 2-3).

NOTE: Birth certificate breastfeeding initiation data were not available for California, Michigan, American Samoa, or the U.S. Virgin Islands. In addition, to prevent identification of individuals, data are not shown for counties or county equivalents if the total number of infants or the number of infants initiating breastfeeding is fewer than 10; the exact breastfeeding rate is not displayed if it is greater than or equal to 90.0% and the total number of infants is fewer than 50.

SOURCE: CDC, 2025a.

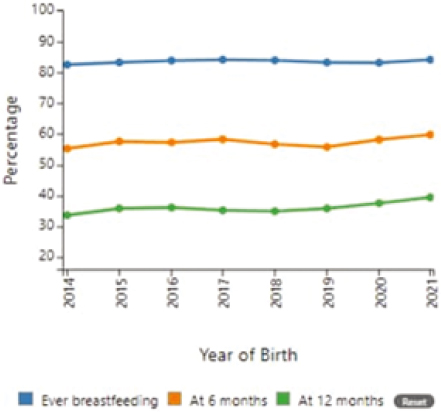

Breastfeeding Exclusivity and Duration

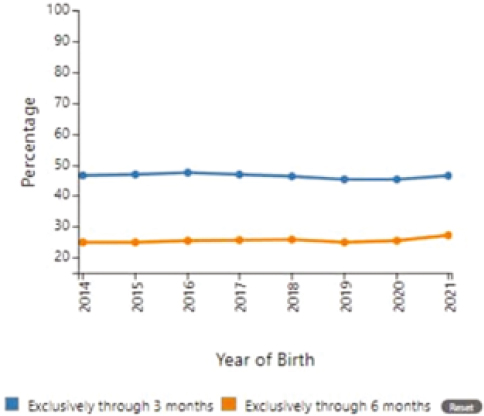

In addition to the NVSS data on initiation, the National Immunization Survey-Child gathers information on breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity, and duration (CDC, 2024b). According to CDC, 84.1% of infants born in 2021 were ever breastfed or initiated breastfeeding. However, by six months, only 59.8% of infants were still breastfeeding or receiving human milk, and at 12 months, this number dropped to 39.5% (CDC, 2025b; Figure 2-4). Sixty percent of mothers who begin breastfeeding report that they stop sooner than they planned (Diaz et al., 2023; Odom et al., 2013). These figures demonstrate that while most mothers initiate breastfeeding, many face barriers that prevent them from meeting national breastfeeding recommendations or their own breastfeeding intentions.

Exclusive breastfeeding falls sharply each month postpartum; in 2021, 46.5% of mothers reported exclusive breastfeeding at three months, and

SOURCE: CDC, 2025b.

27.2% at six months (see Figure 2-5; CDC, 2024). Over the last seven years, these rates have remained relatively stagnant.