From Shellfish to Sunny Day Flooding — Why a GRP Fellow Is Dissecting Water Quality in North Carolina

Program News

By Stephanie Miceli

Last update August 16, 2021

When it comes to monitoring water quality, time matters.

Decision-makers have to make numerous choices about water daily, whether it’s shellfish farmers deciding where to grow clams and oysters, or county public health officials determining if they need to issue a swimming advisory after a heavy flood. Unfortunately, decision-makers are often acting on outdated data, says Natalie Nelson, a 2020-2022 Gulf Research Program Early-Career Research Fellow (ECRF) and assistant professor at North Carolina State University.

Nelson has made it her mission to generate more real-time data on water quality, to inform science-based decisions that benefit the general public.

Initially, Nelson became interested in bacteriological water quality while working with North Carolina’s Office of Shellfish Sanitation. Shellfish are part of North Carolina’s heritage, and the industry contributes $27 million to the state’s economy and 532 jobs. The industry is also a vital source of income for generations of fishing families, and provides healthy local food to restaurants and grocery stores.

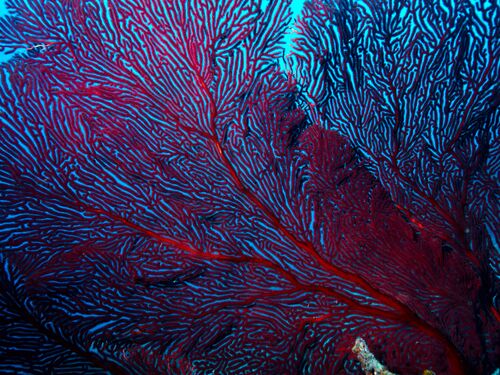

However, shellfish farming is rife with challenges. Oysters and clams must be grown in pristine coastal waters, said Nelson. And water testing and sample collection is a tedious process.

While bacteria and other pollutants carried by stormwater into the ocean don’t necessarily harm shellfish, they can make the people who consume these water-filtering creatures sick. Shellfish farmers must temporarily halt their harvest when bacteria levels are unsafe — and these closures can cost them a substantial percentage of their average annual income.

“After storms, regulators collect samples and figure out the risk of bacterial contamination and whether the area was safe for growing shellfish,” she said. “It’s a time-consuming process. They have to go back to the lab and test those samples, wait 24 to 48 hours, and by that time, the water-quality report could be outdated.”

Nelson wondered if there was a way to be more proactive and predictive about water quality.

“We wanted to find a way to make decisions about water quality in the moment. To what extent can we predict water quality? And, in the meantime, can we give growers advance notice that shellfish waters may close?”

That was the genesis of ShellCast, a forecast tool developed by Nelson and a team of researchers at NC State. ShellCast aims to help North Carolina growers decide the best time to harvest their shellfish. That information could help shorten the window of closure, so growers don’t miss out on income. It’s a timely innovation, as the state has a goal of growing shellfish farming into a $100-million-a-year industry by 2030.

Nelson says the ECRF’s unrestricted funding has enabled her to pursue other bold, untested ideas — like placing robot sensors in the water to improve oyster production along the North Carolina coastline. Her team is working to develop computer models that predict which shellfish growing areas are likely to become bacterial hotspots. The researchers hope to get this information — and ultimately, the sensor tools — in the hands of shellfish growers.

“This is an example of a high-risk, high-reward project — it might not work. But because of the flexibility of ECRF, I was able to purchase the equipment for this project with fellowship funds,” said Nelson. “In many ways, the fellowship funds have been multiplying. I’ve been able to buy new equipment and pursue new ideas, which has been a catalyst for other grants.”

Recently, for example, Nelson received a grant from the National Science Foundation to study the effects of tidal flooding, also known as “sunny day flooding.” While it’s a departure from shellfish, the project hits close to home — literally. Several years ago, when visiting her family in St. Petersburg, Florida, she saw tidewaters cause severe flooding in the roadways and people’s yards.

“When tidal floods occur — when they back up into streets and communities in the Gulf, like where my family lives — it occurred to me it could be dangerous from [a] water-quality perspective,” said Nelson. “For example, when streets and yards are flooded, they can pick up debris, pet waste, and a host of contaminants.”

As these tidal waters recede, they take those contaminants back into bays, rivers, and oceans with them. Nelson is researching how that affects water quality. She hopes to uncover information that will help local governments understand the impacts of sunny day floods, and also inform whether they need to issue water-quality advisories when they occur.

Now halfway through her ECRF fellowship, Nelson says the experience has given her the space to combine her love of research, scientific discovery, and teaching. From a young age, she knew she wanted to pursue a STEM career, and she’s eager to ignite that love of science in middle school and high school students. She plans to engage students outside the classroom, through Science Olympiad competitions and other events.

“Most programs focus on funding a specific project. The GRP Early-Career Fellowship is one of the few programs that will fund you as a person — and your career development. It’s pretty rare to have that opportunity,” she said.

More like this

Discover

Events

Right Now & Next Up

Stay in the loop with can’t-miss sessions, live events, and activities happening over the next two days.

NAS Building Guided Tours Available!

Participate in a one-hour guided tour of the historic National Academy of Sciences building, highlighting its distinctive architecture, renowned artwork, and the intersection of art, science, and culture.