Why Chemistry Might Be Our Best Clue to Life on Other Planets

Program News

By Mike Janicke and Nancy Huddleston

Last update June 25, 2025

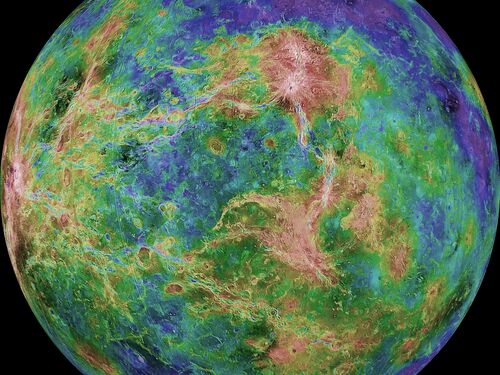

Image Courtesy: NASA/JPL/USGS

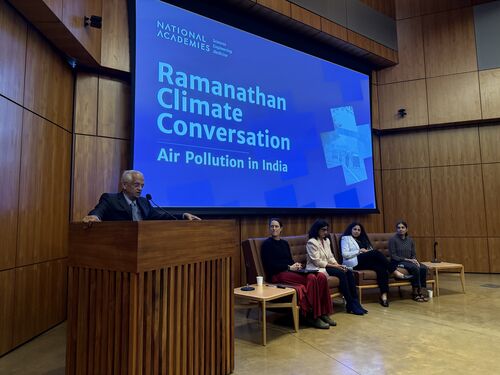

If you were able to catch the last webinar from our Chemical Sciences Roundtable, “Chemistry in 2050– Space” you know that it was out of this world, literally and figuratively. The webinar explored the many ways chemistry can be applied to understand the universe, including to help answer the elusive question of whether or not life exists on other planets. A panel of luminaries in their fields was moderated by Dr. Edward Ashton, an expert in advancing Magnetic Resonance Imaging for cancer treatment and the author of Mickey7, a science fiction novel about 3D printing workers in space that is the basis for the recently released feature film Mickey 17.

Participants discussed several common themes throughout the event: the importance of extreme environments in shaping chemistry, the limitations of our Earth-centric perspective when searching for life, the critical need for better laboratory data to interpret astronomical observations, and the potential for biology to adapt to and thrive in space conditions.

The event began with Dr. Jenny Bergner, an astrochemist at UC Berkeley, who studies the effects on chemical processes of extreme conditions of space—temperatures as low as 10 Kelvin and pressures 13 orders of magnitude below Earth's atmosphere. Combining laboratory simulations with telescope observations, particularly from the James Webb Space Telescope, Dr. Bergner studies how volatiles like water and carbon-bearing compounds are incorporated into forming planets.

Bergner emphasized the critical need for more lab-based astrochemistry to interpret astronomical data properly. "All of the rules of chemistry are the same, but the outcomes can be really different because the physical conditions are so different,” she said.

Building on this foundation, Dr. Jason Dworkin from NASA Goddard described his work analyzing meteorites and asteroid samples—what he calls "witnesses" to the early solar system. The OSIRIS-REx mission's samples from asteroid Bennu have revealed evidence of alkaline brines and observation of 14 of the 20 amino acids and all of the DNA and RNA nucleobases, suggesting connections to prebiotic chemistry. Dworkin explained how these pristine samples help scientists understand the chemical pathways that could lead to life, bridging astronomical observations with potential biological origins.

Dr. Sara Seager of MIT then shifted the focus to detecting life on exoplanets, pointing out that we are the first generation in human history trying to do that. Her work involves the use of transit spectroscopy to detect gases in exoplanet atmospheres that could be signs of life. Seager talked about her research in detecting phosphine in Venus's clouds. Phosphine can be a biosignature on Earth that is produced by microbial life in oxygen-deprived environments. She noted that her work has been controversial, however, with questions still open as to whether the observed signal might have been from sulfur dioxide instead of phosphine, or that the phosphine might have been produced by non-biological sources. Dr. Seager’s more recent research has focused on biochemistry in sulfuric acid environments, challenging our assumptions about where life might exist.

Finally, Dr. Jennifer Talley from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research discussed the practical applications of space bioscience. She explores how polyextremophiles and synthetic biology might enable future technologies in space, from biomanufacturing to life support systems. Talley emphasized the challenges of the "design-build-test-learn" cycle in space environments and the need to understand how biological homeostasis functions beyond Earth.

The panelists also identified research gaps, particularly in funding simple but essential experiments that provide fundamental constants and parameters, and the need for more nimble mission approaches.

The Chemical Sciences Roundtable (CSR) explores cutting-edge topics to inform and advance the fields of chemistry and chemical engineering by bringing together experts from government, industry, non-profits, and academia in workshops, webinars, and other activities. Themes for this year’s CSR webinars and workshops focus on what chemistry will look like in 2050 and the challenges along the way.

Panelists

Staff

Michael Janicke, CSR Director mjanicke@nas.edu. Darlene Gros, Senior Program Assistant. Kayanna Wymbs, Research AssistantMore like this

Discover

Events

Right Now & Next Up

Stay in the loop with can’t-miss sessions, live events, and activities happening over the next two days.

NAS Building Guided Tours Available!

Participate in a one-hour guided tour of the historic National Academy of Sciences building, highlighting its distinctive architecture, renowned artwork, and the intersection of art, science, and culture.