Meeting Critical Laboratory Needs for Animal Agriculture: Examination of Three Options (2012)

Chapter: Summary

In 2006, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) proposed creating the National Bio- and Agro-Defense Facility (NBAF) under the provisions of Homeland Security Presidential Directive 9, which allows DHS to expand its efforts to protect US agriculture and public health. The NBAF was envisioned to have the capacity and capability to conduct research and diagnostic activities for foreign animal diseases (FADs) and zoonotic diseases (diseases that are transmissible between animals and humans) at high-biocontainment levels1 that can accommodate livestock species. It was also intended to replace the aging Plum Island Animal Disease Center (PIADC), which for more than 50 years has been part of the federal network of laboratories in which research and diagnostics on FADs are conducted. PIADC is the only US facility authorized to conduct research on foot-and-mouth disease, a highly contagious disease that the United States has been free of since 1929 and that constitutes a major threat to the US livestock industry.

US animal agriculture is valued at $165 billion and is a principal source of food, a major source of livelihood for Americans, and a major contributor to US agricultural exports. Given its importance, there is a need to protect it from threats of FADs and zoonotic diseases and from potential threats caused by new and emerging pathogens. The proposed NBAF has been envisioned as a next-generation laboratory that would have a central role in the national infrastructure needed to handle threats from FADs, zoonotic diseases, and emerging diseases. However, construction of the proposed NBAF will incur a large expense. With the estimated cost of $1.14 billion to construct the NBAF at the proposed site and the country’s current fiscal challenges, DHS turned to the National Research Council for expert advice to assess the disease threats to US animal and public health, describe the laboratory capabilities and capacity needed to address those threats, and analyze three proposed options to meet laboratory needs. The three options as stipulated by DHS are (1) constructing the NBAF as designed, (2) constructing a scaled-back version of the NBAF to be described by the commit-

![]()

1High biocontainment is used in the report to refer to biosafety levels (BSL) 3 or 4. A description of biosafety levels is found in Box 3-1.

tee, and (3) maintaining current capabilities at PIADC while leveraging ABSL-4 laboratory capacity (for livestock) by using foreign laboratories.

In response to the request, the National Research Council convened an ad hoc committee to conduct a scientific assessment of the requirements for a foreign animal and zoonotic disease research and diagnostic laboratory facility in the United States. As part of its task, the committee assessed the threats to US livestock from current and emerging diseases, including zoonoses, considered an ideal system for addressing those disease threats, and identified the laboratory infrastructure in which the diseases could be diagnosed and studied. The scope of the committee’s analysis was limited to examining the three proposed options. The task explicitly excluded an assessment of specific site locations for the proposed laboratory facility; therefore, it was not within the committee’s charge to compare the relative risks of the three options nor to determine where foot-and-mouth disease research can be safely conducted. The committee’s conclusions and recommendation are summarized in Box S-1 at the end of this chapter.

IMPORTANCE AND VULNERABILITY OF US ANIMAL AGRICULTURE

The United States has been fortunate to have an abundance of natural resources to support its agricultural industry. But the continued success of the food-animal sector has also been due both to unparalleled advances in research that have resulted in remarkable gains in agricultural productivity, and to progress in eliminating many livestock and poultry diseases that still impact animal production and trade in other countries. Investments in an effective animal-health infrastructure have enabled US animal agriculture to focus on producing animals for food to meet growing domestic and international demands. However, the security of this multibillion-dollar enterprise and of the food system to which animal agriculture is intricately connected remains vulnerable to diseases threats, whether intentionally or naturally introduced.

Numerous recent National Research Council studies have assessed disease threats to animal and public health, and the committee did not attempt an exhaustive reconsideration of the broad array of disease agents that can affect animal agriculture. The list of disease threats has not changed nor have the drivers of disease emergence in our global society that can give rise to novel agents or to disease outbreaks caused by agents that are exotic to the United States. Animal diseases that have high priority with the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) also appear on the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) list of animal diseases; although many of these diseases are considered threats to livestock, many are also important zoonoses. In addition to naturally introduced disease threats, the nation also faces the threat of bio- or agroterrorism in which a disease agent is deliberately introduced to destabilize food sources or generate fear. Several homeland security presidential directives have focused on con-

fronting those potential hazards. Therefore, a comprehensive system to counter disease threats to animal agriculture is vital.

Recent epidemics of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and foot-and-mouth disease in the United Kingdom, foot-and-mouth disease in South Korea and Taiwan, and highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) in Asia provide salient examples of the magnitude and breadth of possible consequences associated with disease outbreaks. The global severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2003 demonstrates the effects of a disease that originated in animals and resulted in severe losses to individuals and many business sectors. Thus, whether they directly affect the health of animals only or whether they are transmitted from animals to humans, disease outbreaks have a major impact on agriculture, food security, and socioeconomic well-being.

THE ROLE OF A NATIONAL LABORATORY FACILITY IN AN INTEGRATED SYSTEM

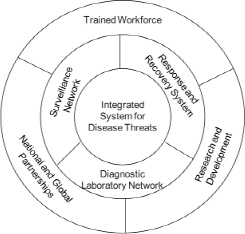

Protecting US animal agriculture requires an integrated system that spans authorities, geography, and many programs and activities. The adage that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link applies to the complex systems needed to protect animal agriculture from the incursion of serious diseases and to address a riskier world. The committee addressed its study task in the context of an ideal integrated system for addressing FAD and zoonotic disease threats to the United States and considered what the role of a national biocontainment laboratory would be within such a system. The ideal system would capture and integrate the substantial human and physical assets distributed throughout the nation to address the threat of FADs and zoonotic diseases. It would include components of surveillance, diagnostics, and disease response and recovery. Research and development and workforce training are also critical core elements that support each of the functional arms (Figure S-1).

A national role in the coordination of the system is essential, and a federal laboratory or network of laboratories would be the cornerstone of an integrated system. The ideal system also reaches beyond national borders to tap the expertise and resources of the global infectious disease surveillance, diagnostic, and research communities. Recognizing the threat posed by zoonotic diseases and the known and potential roles that animals play in maintaining and transmitting infectious agents, the ideal system captures both human- and animal-health expertise and laboratory infrastructure to achieve common goals for disease recognition and response.

A substantial number of high-biocontainment (BSL-3 and BSL-4) laboratories have been constructed in the United States by federal and state agencies, universities, and private companies in the past 10 years. They provide an opportunity for collaborations that maximize national efforts to detect and respond to any incursion of an FAD or zoonotic disease. Strategic collaborations with other biocontainment facilities would also potentially enhance the efficient use of a

central laboratory. One example is the 13 regional BSL-3 containment laboratories constructed with funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). They are generally large facilities that include laboratory space for both in vitro and in vivo research and product-development activities to address emerging infectious diseases and pathogens of bioterrorism concern. Their activity focuses on pathogens of human-health importance, some of which may also affect agriculturally important animals.

BSL-4 laboratories with the capacity to handle large animals (ABSL-4 large animal) exist outside the United States. Each of them has the capability to handle livestock species and, depending on the situation at the time a request is made, may be willing to collaborate with US scientists to investigate pathogens that require ABSL-4 large-animal containment. However, the primary responsibility of those laboratories is to address their own national government and domestic needs.

FIGURE S-1 Components of an integrated national system for addressing foreign animal disease and zoonotic disease threats. Laboratory infrastructure underlies all components.

Although there are several BSL-4 laboratories in the United States, there is no ABSL-4 large-animal facility and the challenges of using the highest level of biocontainment space (ABSL-4) for large-animal research and diagnostic development are substantial. Additionally, the facilities at PIADC dedicated to FADs are dated and increasingly cost-inefficient. While biosafety level 3 agriculture (BSL-3Ag) containment space that is appropriate for research using group-housed agricultural animals has expanded through construction of several new facilities (such as the Biosecurity Research Institute and the National Animal Disease Center), it is insufficient to meet all of the needs for FAD research in

the United States. Thus, there is a critical national need for laboratory capacity with modern BSL-3Ag and ABSL-4 large-animal capabilities that can serve as the hub of a national strategy for detection of and response to any incursion of an FAD and that can accommodate the study of infectious diseases of public-health importance in which livestock serve as key reservoir hosts. However, with the rapidly evolving nature of disease threats that confront animal health and with the rapid development of technologies for detecting and responding to diseases, planning for the construction of such a facility requires a flexible and nimble strategy for programmatic and facility design. Such a facility cannot stand alone and needs to be integrated in a national system. US programs for FAD and zoonotic disease detection and response (programs proposed for the NBAF) should have interfaces with similar activities and programs of the National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the US Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases, USDA, NIH, and academic and state institutions to maximize efficiency and the use of intellectual resources through interdisciplinary research that crosses traditional agency boundaries. Such interagency working relationships would be essential for maximizing the success of the NBAF.

ANALYSIS OF THREE LABORATORY INFRASTRUCTURE OPTIONS

Laboratory infrastructure underlies all components of an ideal integrated system to address disease threats. Such a laboratory infrastructure would include the capacity to safely perform diagnostics, to conduct research on foot-and-mouth disease, to conduct research on non-foot-and-mouth disease FADs and zoonotic diseases in BSL-3Ag facilities, to undertake special pathogen activities in BSL-4 and ABSL-4 facilities, to support teaching and training, and to enable vaccine or other product development. In the context of these critical core laboratory components, the committee examined the advantages and liabilities of the three proposed options in its statement of task: constructing NBAF as currently designed, scaling back the size and scope of the proposed NBAF, or maintaining the current PIADC and leveraging the US capability and capacity through international laboratories with ABSL-4 large-animal containment space.

Option 1, the NBAF as currently designed, includes all components of the ideal laboratory infrastructure in a single location and has been designed to meet the current and anticipated future mission needs of DHS, the USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS), and the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). It creates ABSL-4 large-animal capacity and additional BSL-3Ag capacity in the United States and would provide the United States with needed in-country infrastructure to address FAD and zoonotic disease threats. By housing the laboratory components in one facility, it avoids a need to move specimens or materials (some of which may be select agents) from other facilities and avoids a need to rely on partner entities in the United States or internationally. However, there are also drawbacks. Substantial costs are associated

with the construction, operation, and management of the proposed NBAF in addition to costs associated with the proposed expansions in DHS, USDA-ARS, and USDA-APHIS programs. Because it houses the laboratory components and associated research, development, and training activities in a central facility, the proposed NBAF does not fully utilize other existing and complementary investments in high-biocontainment laboratory, diagnostic, training, and vaccine development capacity in the United States and has the potential for duplication of resources—duplication that could be addressed by exploring partnerships with other facilities.

Several components of the NBAF as currently designed could potentially be reduced in size and scope or eliminated if US and international partnerships were used to meet the needs of an ideal system. In analyzing Option 2, an NBAF of reduced size and scope as described by the committee, examples of the areas that the committee suggested could be considered for reduction or elimination from the proposed NBAF are the biodevelopment module (BDM) for pilot vaccine production and BSL-3Ag rooms designated for training along with the associated training necropsy room. The committee also suggested that reductions in the sizes of the BSL-3Ag animal rooms, the ABSL-4 small-animal rooms, and the associated BSL-3E and BSL-4 laboratory space could be considered. The pilot vaccine production work conducted in the BDM, which is outside the biocontainment envelope, and most teaching and training activities could be conducted in collaboration with other US federal, state, university, and private-sector laboratories. Option 2 would have lower construction costs than the proposed NBAF and might also have lower sustained operations costs, although the actual cost implications are not clear given the limited and insufficient information provided by DHS. The NBAF of reduced size and scope as described by the committee would still consolidate DHS, USDA-ARS, and USDA-APHIS missions in a single location and address critical core gaps in BSL-3Ag and ABSL-4 large-animal capabilities in the United States. It could also make more efficient use of recently expanded US high-biocontainment laboratory capacity while achieving the overall needs of countering FAD and zoonotic disease threats to the nation. Option 2 highlights a change in the approach to animal diseases by drawing on scientific and research expertise available in other federal laboratories and outside government, providing intellectual benefits and possible cost savings through increased efficiencies by avoiding duplication, and fostering greater collaboration between researchers as part of an integrated US system for countering FAD and zoonotic disease threats. Finally, by relying on a network of partners, this option may provide increased flexibility to re-evaluate laboratory infrastructure needs periodically in light of new and emerging disease priorities and technologies. In contrast, not all components of the ideal system would be housed in a single facility. Implementing this option successfully would require the creation of agreements with the necessary federal agency and nongovernment partner facilities, including funding commitments to partner facilities to conduct collaborative work and management capacity to oversee collaborations. Pursuing this option would thus have policy implications and

might require DHS and USDA to make priority-setting decisions, given the potential reductions in designated agency laboratory space in the central facility.

A partnership of a central national laboratory of reduced scope and size and a distributed laboratory network can effectively protect the United States from FADs and zoonotic diseases, potentially realize cost savings, reduce redundancies while increasing efficiencies, and enhance the cohesiveness of a national system of biocontainment laboratories. However, because the cost implications of reducing the scope and capacity of a central facility cannot be known without further information and study, it will be important for DHS and USDA to make a good-faith effort to re-examine construction and operating costs of a laboratory of reduced size and complexity, and to also consider what those implications are for priority-setting decisions.

Option 3, maintaining PIADC and leveraging ABSL-4 large-animal capacity through other partners, would utilize an existing US facility that provides some of the needed laboratory infrastructure components and would avoid the costs of constructing a new replacement facility. PIADC is also the only US facility for research, diagnostics, and training related to foot-and-mouth disease. However, DHS highlighted the fact that the facilities at PIADC are aging and do not meet current standards for high-biocontainment laboratories. There are substantial costs associated with maintaining and operating PIADC over the long term, it lacks BSL-4 and ABSL-4 capabilities, and the committee was informed by DHS that such facilities could not be constructed at PIADC. If a full commitment were made to improving and maintaining PIADC, a period of transition to a new facility with a window of potential loss of function would not be needed. Option 3 would also realize the benefits of capital renovations and improvements that must be made no matter which option is selected over a longer period. As the committee explored the potential of relying on international partners for emergency work that might require ABSL-4 large-animal laboratory space, it found remarkably little capacity near the United States. Because this option would not provide the United States with ABSL-4 large-animal capabilities, agreements with foreign partners for access to ABSL-4 large-animal space and funding to support these collaborations would be required. Although that could enhance international collaboration in research on FADs and zoonotic diseases, it could limit the availability of ABSL-4 capabilities in a time of critical need, depending on the priorities of the foreign countries, and would separate ABSL-4 large-animal facilities from other FAD research.

ESSENTIAL CAPABILITIES NEEDED

Research to understand and protect the United States from the consequences of an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease remains a high priority, and PIADC is the only US facility currently authorized to conduct work with foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDv). Because foot-and-mouth disease research remains critical for the US animal-health system, the committee concludes that it will be essen-

tial to support PIADC until an alternative facility is authorized, constructed, commissioned, and approved for work with FMDv.

Although current livestock-specific FADs do not require BSL-4 laboratory containment, a disease outbreak caused in US livestock by a highly contagious zoonotic virus or a novel pathogen of undetermined transmissibility would require appropriate emergency biocontainment; it would also require research in live animals to characterize the infectious agent, transmission, and host range and susceptibility and to validate diagnostics. The committee notes that it is in the interest of the United States to pursue partnerships with countries that have ABSL-4 large-animal laboratories for the study of zoonotic agents of agricultural concern. However, given the uncertainty of priorities of a foreign laboratory and logistical difficulties in an emergency, it would not be desirable for the United States to rely on international laboratories to meet ABSL-4 large-animal needs in the long term. Therefore, as part of the national infrastructure for protecting animal and public health, the committee concludes that there is an imperative to build ABSL-4 large-animal space in the United States.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR FULFILLING NATIONAL NEEDS

Realizing cost savings in the construction and operation of laboratory facilities is a critically important objective; however, it is no less important for DHS, USDA, and other relevant agencies to maintain their focus on the overarching goal of developing a highly capable system for addressing FAD and zoonotic disease threats. A central laboratory would be a key part of an integrated national system, but it would only be one component of the system; therefore, the committee concludes that innovative, forward-thinking solutions are required not only about the central laboratory but about the entire system. The solutions for the entire system may need to involve consideration of a wider range of options for the central laboratory. That analysis extends beyond the scope of the current study.

In exploring national capabilities, the committee found a substantial number of public and private biocontainment laboratories across the country; these are capabilities that did not exist nearly a decade ago when Homeland Security Presidential Directive 9 was issued, nor did they exist when previous NRC reports on options for a national biocontainment laboratory were issued. Institutions that house a variety of BSL-3, BSL-3Ag, and BSL-4 laboratories in the United States can serve as partners in a national system and those existing capabilities can be leveraged in the national interest. The major barriers to leveraging capabilities at those facilities are the need to establish formal relationships, agreed-upon operational protocols, contractual funding arrangements, and well-reasoned policies about the kind of work that can be conducted in different facilities. Yet in the committee’s view, it is precisely those kinds of relationships that could move the nation closer to the ideal, integrated national system to address animal disease threats—one in which a distributed laboratory network is

tied closely to a central supporting facility. Regardless of the options considered for a central facility, the committee recommends that DHS and USDA develop and implement an integrated national strategy that utilizes a distributed system for addressing FAD and zoonotic disease threats. The National Animal Health Laboratory Network is an excellent model of such a distributed laboratory network and would serve a critical role in a more comprehensive and integrated national strategy.

Balanced Support for Infrastructure and Research and Development

The committee concludes that it is critical for policy-makers and agency planners to recognize that an effective system for addressing FAD and zoonotic disease threats to the United States consists of more than facilities; it also requires robust research programs. Those cannot be traded off against one another; rather, balanced support is needed to enable the continuation of research priorities and capital costs associated with maintaining or constructing modern laboratory facilities.

Ongoing Planning and Prioritizing for the National System

The committee concludes that conceptualizing, implementing, and maintaining a US national system to address threats posed by FADs and zoonotic diseases requires not only an understanding of today’s priorities and technologies but continued monitoring and assessment to understand how the high-priority threats and the tools available to address them change over time. Such vision and planning are critical and must be ongoing. There is a related need for continuing communication and coordination among the many parties and stakeholders that form an efficient, effective, and integrated national system.

Alternative Funding Mechanisms

The committee concludes that exploring alternative funding mechanisms to supplement current federal allocations for capital and operational costs and for program support would be useful. Alternative funding strategies used by other countries could be considered as possible models. For instance, Australia draws on industry contributions to help support its national animal disease capabilities. It may also be useful to explore the possibility of using public-private partnerships to support and maintain aspects of facilities and research programs.

Consideration of All Factors of Concern

The importance of having a strong national system to recognize and counter the threats posed by FADs and zoonotic diseases may not always be apparent when disease outbreaks are quickly identified, mitigated, and contained, but the consequences of such disease outbreaks can be enormous if and when a system fails. This study provides a high-level view of whether each of the three options stipulated by DHS could be feasible in meeting the nation’s needs. As discussed in Chapter 4, the committee also recognizes that the three DHS-proposed options may not be the only options worth considering. Concerns considered in this study—costs, necessary capabilities, and infrastructure needs—do not reflect all of the factors decision-makers must consider. The factors that were considered in the original assessment that led to decisions about the NBAF may or may not have changed. For example, safety concerns still linger on the issue of bringing foot-and-mouth disease research onto the US mainland and the risk of accidental release of FMDv and its consequent impacts. Decisions about infrastructure needs should not be made in the absence of risk concerns as well as the many other factors worthy of consideration. The committee concludes that to most appropriately fill critical laboratory needs in the United States, all factors of concern (including site location, risk assessment, political considerations, adaptability for the future) will need to be considered in a more comprehensive assessment.

BOX S-1

Conclusions and Recommendation for Meeting Critical Laboratory Needs

It is imperative to establish research, diagnostic, and surveillance laboratory capabilities commensurate with the size and value of the US animal agriculture industry to prevent or mitigate a disease outbreak that could have devastating effects on human and animal lives and livelihoods. The ideal system to counter threats from foreign animal diseases (FADs) and zoonotic diseases includes research, development, and training; a centralized core facility; a distributed network of national and international partnerships; and disease surveillance, diagnostic, and response capabilities. A central laboratory would be a key part of an integrated national system, but it would only be one component of the system. In addressing its Statement of Task, the committee provides the following conclusions and recommendation for fulfilling critical laboratory needs in the United States.

CONCLUSIONS

Conclusion 1: The National Bio- and Agro-Defense Facility (NBAF) as currently designed includes all components of the ideal laboratory infrastructure in a single location and has been designed to meet the current and anticipated future

mission needs of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Research Service (ARS), and the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS); but the proposed facility also has drawbacks (i.e., substantial costs associated with construction, operation, and management; not leveraging existing capacity and potential duplication of resources).

Conclusion 2: A partnership of a central national laboratory of reduced scope and size and a distributed laboratory network can effectively protect the United States from FADs and zoonotic diseases, potentially realize cost savings, reduce redundancies while increasing efficiencies, and enhance the cohesiveness of a national system of biocontainment laboratories. However, given the limited and insufficient information provided by DHS, the cost implications of reducing the scope and capacity of a central facility cannot be known without further information and study.

Conclusion 3: Maintaining the Plum Island Animal Disease Center (PIADC) and drawing on the ABSL-4 large-animal capacity of other partners would utilize an existing US facility that provides some of the needed laboratory infrastructure components and would avoid the costs of constructing a new replacement facility. However, the facilities at PIADC are aging and do not meet current standards for high-biocontainment laboratories. There are substantial costs associated with maintaining and operating PIADC over the long term, it lacks BSL-4 and ABSL-4 large-animal capabilities, and the committee was informed by DHS that such facilities could not be constructed at PIADC. Given the uncertainty over priorities of a foreign laboratory and logistical difficulties in an emergency, it would not be desirable for the United States to rely on international laboratories to meet ABSL-4 large-animal needs in the long term.

Conclusion 4: Because foot-and-mouth disease research remains critical for the US animal-health system, it will be essential to support PIADC until an alternative facility is authorized, constructed, commissioned, and approved for work with FMDv.

Conclusion 5: As part of the national infrastructure for protecting animal and public health, there is an imperative to build ABSL-4 large-animal space in the United States.

Conclusion 6: Innovative, forward-thinking solutions are required not only about the central laboratory but about the entire system.

Conclusion 7: It is critical for policy-makers and agency planners to recognize that an effective system for addressing FAD and zoonotic disease threats to the United States consists of more than facilities; it also requires robust research programs.

Conclusion 8: Conceptualizing, implementing, and maintaining a US national system to address threats posed by FADs and zoonotic diseases requires not only an understanding of today’s priorities and technologies but continued monitoring and assessment to understand how the high-priority threats and the tools available to address them change over time. Such vision and planning are critical and must be ongoing.

Conclusion 9: Exploring alternative funding mechanisms to supplement current federal allocations for capital and operational costs and for program support would be useful.

Conclusion 10: To most appropriately fill critical laboratory needs in the United States, all factors of concern (including site location, risk assessment, political considerations, adaptability for the future) will need to be considered in a more comprehensive assessment.

RECOMMENDATION

Regardless of the options considered for a central facility, the committee recommends that DHS and USDA develop and implement an integrated national strategy that utilizes a distributed system for addressing FAD and zoonotic disease threats.