Meeting Critical Laboratory Needs for Animal Agriculture: Examination of Three Options (2012)

Chapter: 3 An Integrated National System for Addressing Foreign Animal Diseases and Zoonotic Diseases

3

An Integrated National System for Addressing Foreign Animal Diseases and Zoonotic Diseases

US federal agencies have a responsibility for and a vital role in the prevention, detection, and control of foreign animal diseases (FADs) and zoonotic diseases that have the potential for broad health and socioeconomic effects. Historically, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has addressed disease threats to the agricultural animal industries that may occur as a result of introduction of an FAD, and confronting the potential human health effects of zoonotic diseases has been the responsibility of the Department of Health and Human Services. Although the historical mandates of those agencies have not changed, the disease threats have. The threat of bioterrorism, heightened after the events of September 11, 2001; the later creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS); and advances in biotechnology that have increased the risk of purposeful or inadvertent modifications of microorganisms that could increase virulence, expand host range, or enhance transmissibility (Berns et al., 2012; Enserink and Cohen, 2012) have drawn the world’s attention to the threat of disease outbreaks. Our growing global interconnectivity; the growing global population; the demand for food, particularly animal-based protein; and increasing contact with wild ecosystems through land development make it likely that emerging and re-emerging pathogens will continue to occur and spread at an even greater rate. Scientists predict that two to four new pathogens will emerge each year and that RNA viruses, especially those at the human-animal interface, will present the greatest threat (Brownlie et al., 2006). The factors that could create “the perfect microbial storm”, as described by the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2003), are still in place and intensifying, and this suggests that the risk of disease incursion continues to increase and that the implications are even more profound. The impact of those factors has been felt on local to global levels, and has resulted in policy changes in disease reporting by such international agencies as the World Health Organization (WHO) through the codification of the

International Health Regulations in 2005 (WHO, 2007) and the revised list of notifiable diseases (see Table 2-1 in Chapter 2) and requirements for notification of emerging diseases by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE, 2010). Commensurate with those changes is an expectation that WHO and OIE member countries will have a reliable infrastructure for disease surveillance and response (Fidler, 2005; Baker and Fidler, 2006).

As noted in Chapter 2, a number of previous National Research Council (NRC) and IOM studies have addressed current threats to our nation’s health and welfare, including both FADs and zoonotic diseases (IOM, 2003). A recent IOM and NRC report, Sustaining Global Surveillance and Response to Emerging Zoonotic Diseases (2009), is of particular relevance and recommended several actions to strengthen the global capacity for addressing disease threats. The recommendations included improved use of information technology (Recommendation 1-2), a strengthened global laboratory network (Recommendation 1-3), and expanded human-resource capacity (Recommendation 1-4) to support disease surveillance and response (IOM and NRC, 2009). The recommendations for a global system apply equally to the framework for animal-disease surveillance and response within the United States, whether for zoonotic diseases or FADs. Protecting US animal agriculture requires a well-integrated system that spans authorities, geography, and many programs and activities. The idea that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link applies to the complex systems needed to protect animal agriculture from the incursion of serious diseases and to address a riskier world.

THE ROLE OF A NATIONAL LABORATORY FACILITY IN AN INTEGRATED SYSTEM

Critical Core Functions

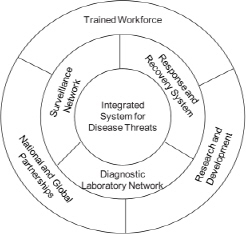

The committee considered its task in the context of an integrated system in the United States for addressing FAD and zoonotic disease threats and the role of a national biocontainment laboratory in such a system. The ideal system would capture and integrate the substantial human and physical assets distributed throughout the nation to optimally address the threat of FADs and zoonotic diseases. It would include surveillance and detection, diagnostics, and disease response and recovery and would have research and development and training of the workforce as critical core elements to support each of these functional arms (see Figure 3-1). These elements would provide the capabilities needed to support multiple disease-control strategies, the choice of which is dependent on many factors such the likelihood of introduction to the United States, disease spread rates, and cost and effectiveness of control. A robust laboratory infrastructure underlies all those components. A national role in the coordination of the system is essential, and a federal laboratory or network of laboratories would be the cornerstone of the system. The ideal system would reach beyond our borders to tap the expertise and resources of the global infectious-disease surveil-

lance, diagnostic, and research communities. Recognizing the threat posed by zoonotic diseases and the known and potential roles of animals in maintaining and transmitting infectious agents, the ideal system would capture both human- and animal-health expertise and laboratory infrastructure to achieve the common goals of disease recognition and response.

FIGURE 3-1 Components of an integrated national system for addressing foreign animal disease and zoonotic disease threats. Laboratory infrastructure underlies all components.

Surveillance

At the heart of early recognition of a newly introduced disease, whether its occurrence is intentional or natural, is the ability to gather and access data from the field. Technology for capturing the billions of bits of information flowing through electronic channels every day can help to detect unusual events in real time, but it is unlikely that a technology-based approach to data acquisition will ever be the sole or most accurate means by which we can recognize a disease occurrence in the United States. Human resources and a trained workforce are vital to early recognition and verification of an emerging disease event. It is essential to ensure that trained personnel, both professional and lay, are well versed in the manifestations of known diseases in animals and humans and attuned to the variations in disease expression that can indicate a newly emerging disease event. The various clinical signs and pathological changes caused by FAD and zoonotic disease agents can be demonstrated effectively with experimental inoculation of animals, and many FAD and zoonotic disease agents require animal biosafety level 3 (ABSL-3), biosafety level 3 agriculture (BSL-3Ag), or ABSL-4 containment for live-animal work; so training of the workforce in early detection is an essential function that should be provided by a cen-

tral laboratory that has appropriate biocontainment (see Box 3-1 for the description of biosafety levels). The committee agreed that the strategic use of video imaging, plastination (fixation, dehydration, impregnation, and hardening of tissues), and other technological means to capture and broadly disseminate training materials through electronic media, and engagement of the workforce in disease-control campaigns in regions that are endemic for animal diseases or that experience outbreaks of diseases foreign to the United States could reduce the need for hands-on training with experimentally infected animals and thereby reduce the need for training space in the proposed NBAF.

BOX 3-1

Laboratory Biosafety Levels and Types of Pathogens Handled at Each Level

as defined in The Biosafety in Microbiological and

Biomedical Laboratories, 5th Edition

Biosafety Level 1 (BSL-1): Biosafety Level 1 is suitable for work involving well-characterized agents not known to consistently cause disease in immunocompetent adult humans, and present minimal potential hazard to laboratory personnel and the environment.

Biosafety Level 2 (BSL-2): Biosafety Level 2 builds upon BSL-1. BSL-2 is suitable for work involving agents that pose moderate hazards to personnel and the environment. It differs from BSL-1 in that: 1) laboratory personnel have specific training in handling pathogenic agents and are supervised by scientists competent in handling infectious agents and associated procedures; 2) access to the laboratory is restricted when work is being conducted; and 3) all procedures in which infectious aerosols or splashes may be created are conducted in biosafety cabinets or other physical containment equipment.

Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3): Biosafety Level 3 is applicable to clinical, diagnostic, teaching, research, or production facilities where work is performed with indigenous or exotic agents that may cause serious or potentially lethal disease through the inhalation route of exposure.

Animal Biosafety Level 3 (ABSL-3): Animal Biosafety Level 3 involves practices suitable for work with laboratory animals infected with indigenous or exotic agents, agents that present a potential for aerosol transmission, and agents causing serious or potentially lethal disease.

Biosafety Level 3 Enhanced (BSL-3E): Situations may arise for which enhancements to BSL-3 practices and equipment are required; for example, when a BSL-3 laboratory performs diagnostic testing on specimens from patients with hemorrhagic fevers thought to be due to dengue or yellow fever viruses. When the origin of these specimens is Africa, the Middle East, or South America, such specimens might contain etiologic agents, such as arenaviruses, filoviruses, or other viruses that are usually manipulated in a BSL-4 laboratory. Examples of enhancements to BSL-3 laboratories might include: 1) enhanced respiratory protection of personnel against aerosols; 2) high-efficiency particulate air filtration of dedicated exhaust air from the laboratory; and 3) personal body shower.

Biosafety Level 3 Agriculture (BSL-3Ag): In agriculture, special biocontainment features are required for certain types of research involving high consequence livestock pathogens in animal species or other research where the room provides the primary containment. To support such research, the US Department of Agriculture has developed a special facility designed, constructed and operated at a unique animal containment level called BSL-3Ag. Using the containment features of the standard ABSL-3 facility as a starting point, BSL-3Ag facilities are specifically designed to protect the environment by including almost all of the features ordinarily used for BSL-4 facilities as enhancements.

Biosafety Level 4 (BSL-4)1: Biosafety Level 4 is required for work with dangerous and exotic agents that pose a high individual risk of aerosol-transmitted laboratory infections and life-threatening disease that is frequently fatal, for which there are no vaccines or treatments, or a related agent with unknown risk of transmission. Agents with a close or identical antigenic relationship to agents requiring BSL-4 containment must be handled at this level until sufficient data are obtained either to confirm continued work at this level, or re-designate the level.

SOURCE: CDC (2009).

Training at a national facility can be supplemented, for example, with

• USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) online resources.2

• The online FAD information and Emerging and Exotic Diseases of Animals (EEDA) course provided by the Center for Food Security and Public Health at Iowa State University.3

• The Foreign Animal Disease Training Course at Colorado State University.4

• The Foreign Animal, Emerging Diseases course at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine.5

![]()

1 The designation “ABSL-4 large animal” is a terminology used by DHS to specify areas where biosafety level 4 research in large animals is conducted, but this term has not been codified by the BMBL.

2 URL: http://www.aphis.usda.gov/emergency_response/NAHEM_training/index_nahem.shtml (accessed June 1, 2012).

3 URL: http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/EEDA-Course/ (accessed June 1, 2012). The EEDA Web-based course was developed in 2000-2002 by Iowa State University, the University of Georgia, the University of California, Davis, and USDA. It has been used since 2002 in US veterinary schools to raise awareness of foreign, emerging, and exotic animal diseases and the appropriate responses if an unusual disease is suspected. The EEDA book is provided to all students at veterinary colleges and schools in the United States through funding from APHIS.

4 URL: http://www.cvmbs.colostate.edu/aphi/ (accessed June 5, 2012).

• Continuing-education courses, such as Response to Emergency Animal Diseases in Wildlife,6 and other online and digital media sources of FAD information (such as a CD on FADs provided by the National Center for Animal Health Emergency Management).7

• Core or elective courses in FADs that are required to be in the curricula of the 28 accredited colleges and schools of veterinary medicine in North America.

• Specialized courses in FAD recognition, such as the Smith-Kilborne FAD course offered at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine and Plum Island Animal Disease Center (PIADC).8

Box 3-2 summarizes current FAD courses offered at PIADC.

BOX 3-2

Training Courses Offered at the Plum Island Animal Disease Center

Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostics Course

The regular Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostics (FADD) course is intended to train veterinarians employed by federal agencies (mostly USDA-APHIS Veterinary Services), by states, and by the military (primarily the Army Veterinary Corps). The FADD training course is provided three times a year with a maximum participation of 30 veterinarians each time. Today, federal, state, and military veterinarians take the same course (the military Transboundary Animal Diseases (TAD) course was separate for several years). The course includes live experimental animal demonstrations of 11 important livestock diseases (such as foot-and-mouth disease, classical swine fever, exotic Newcastle disease, and highly pathogenic avian influenza) and lectures on 23 diseases of livestock and poultry species. It also covers lectures and demonstrations on the use of personal protective equipment; on-farm disease investigation; collection, packaging, and mailing of diagnostic samples; and administrative procedures related to disease investigation, reporting, and emergency response.

Veterinary Laboratory Diagnostician Course

A separate 1-week course is offered to faculty and residents of US veterinary colleges and schools each year. It follows the same format as the FADD course. Participants do not spend much time in USDA-APHIS administrative training, and they do not become FAD diagnosticians.

![]()

5 URL: http://www.veterinarypracticenews.com/vet-breaking-news/foreign-animal-emerging-disease-course.aspx (accessed June 6, 2012).

6 URL: http://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/prof_development/ (accessed June 4, 2012).

7 Jon Zack, USDA-APHIS, pers. comm., June 1, 2012.

8URL: http://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/prof_development/smith_kilborne.shtml (accessed May 31, 2012).

International Transboundary Animal Diseases Course

The International Transboundary Animal Disease (ITAD) course is organized and funded through USDA-APHIS International Services (in contrast with the above courses, which are organized and funded through USDA-APHIS Veterinary Services). The course has been given 11 times, once almost every year, with up to 30 international veterinarians each time. It has been delivered completely in Spanish six times. Participants are selected by veterinary and agricultural attachés from among government or academic veterinarians around the world. As in the case of the FADD and the Veterinary Laboratory Diagnostician courses, there is no fee to attend this course; the participants’ sponsoring institutions pay for associated travel, lodging, and meals. The ITAD course follows the same schedule and animal demonstrations as the regular FADD course, except that participants do not spend time on USDA-APHIS administrative policies and procedures; instead, they are exposed to discussion on international trade, epidemiology, and emergency response.

Smith-Kilborne Foreign Animal Disease Course

This course in the current format has been delivered for 10 years and includes one veterinary student (after completion of their second year) from each of the 28 US colleges and two international veterinary students (from Canada or Mexico). The Smith-Kilborne program is designed to acquaint veterinary students with various FADs that potentially threaten our domestic animal population. The course includes classroom presentations for 3 days at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine on diseases and their implications and 2 days of laboratory experience at the PIADC, where participants observe foot-and-mouth disease, African horse sickness, highly pathogenic avian influenza, and exotic Newcastle disease. The PIADC portion of the course coincides with the first week of a regular FADD course, and experimentally infected animals are shared by the two courses. Students practice necropsies on poultry only. After the course, students are expected to share their new knowledge by giving seminars at their colleges.

Apart from the need to maintain a trained and ready workforce and a potential research and development requirement to support this component, field-based surveillance itself does not require high-biocontainment (BSL-3 and BSL-4) space, although case or outbreak investigations of zoonoses may require use of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

Diagnostics

Historically, the National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL) at Ames, Iowa have provided support for diagnosis of endemic “program diseases”9 in the United States by qualified and approved nonfederal laboratories. Training programs for laboratory personnel, proficiency testing, and reference

![]()

9 Program diseases are those designated as “necessary to bring under control or eradicate from the United States” (APHIS, 2012).

reagents have been valuable contributions to state laboratories’ ability to perform diagnostic testing for control programs targeting such endemic diseases as brucellosis, pseudorabies, tuberculosis, and equine infectious anemia. The role of the NVSL Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (FADDL), which is co-located with USDA-ARS and DHS at the PIADC, has been more limited in that it has focused on FADs, for which nonfederal laboratories were not allowed to perform diagnostic testing. The development of the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) in 2002 and associated changes in policy (Memorandum 580.4)10 now allow state laboratories to conduct diagnostic testing for FADs. Box 3-3 provides an overview of the NAHLN from its inception to the present.

The NAHLN is an excellent example of an integrated system that was created to address the nation’s needs, in this case for diagnostic support for early detection, response to an outbreak, and recovery. With the implementation of the NAHLN, the NVSL laboratories at the National Centers for Animal Health (NCAH) in Ames, Iowa, and FADDL at Plum Island now play a vital and irreplaceable role in supporting testing for FADs in approved NAHLN laboratories. Initial test validation (including analytical assessment with samples collected from experimentally infected animals, diagnostic sensitivity, and specificity determination with samples obtained from outbreaks in endemic areas outside the United States, which can be handled only at PIADC and NCAH), reference-reagent production, and proficiency testing are all examples of the critical core functions best managed by a federal laboratory in support of diagnostic testing on a nationwide basis in qualified laboratories. Continued assessment of validated assays against newly arising variants obtained from outbreaks outside the United States also requires adequate biocontainment. For foot-and-mouth disease, this is performed in a federal facility approved for handling of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDv) .

Finally, the role of NVSL in confirmatory diagnosis of the index case of an FAD cannot be overvalued. Because of the inevitable effects on lives and livelihoods, the index case of a new disease in the United States must be officially reported by a federal agency. The current role of state NAHLN laboratories in the diagnosis of an index case of a potential FAD is to obtain a test result that is actionable but presumptive; appropriate samples are also sent to NVSL, Ames or Plum Island for confirmation. Assays such as cell culture used for confirmatory diagnosis result in amplification of a virus that may be highly contagious and requires a modern, high-biocontainment laboratory environment like that proposed for the NBAF. The ability to culture live FAD pathogens like FMDv for characterization and reference is a critical core function of a national biocontainment laboratory.

![]()

10 URL: http://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/lab_info_services/downloads/VSMemo580_4.pdf (accessed May 31, 2012).

BOX 3-3

The National Animal Health Laboratory Network

The National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN), launched in 2002, is a cooperative effort of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and the American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians (AAVLD). The mission of the NAHLN is to provide accessible, timely, accurate, and consistent animal disease diagnostic services nationwide that meet the epidemiological and disease reporting needs of the country. The NAHLN also maintains the capacity and capability to provide laboratory services in the event of an FAD or emerging disease event in the country. The NAHLN focuses on diseases of livestock, but it also responds to disease events in nonlivestock species. The NAHLN has contributed to several surveillance activities and control strategies of national interest. The NAHLN laboratories are the first line of early detection of transboundary diseases and serious zoonotic diseases introduced into the United States.

The origins of the NAHLN are in the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 and Homeland Security Presidential Directive 9 (HSPD-9), both of which called on USDA to establish surveillance systems for animal diseases that would mitigate threats to the nation’s agricultural sector.

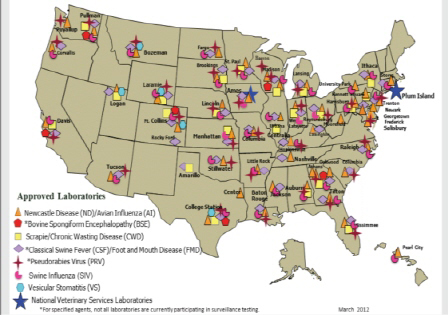

The USDA Safeguarding Review (NASDARF, 2001) identified the need for a network that would coordinate laboratory capacity at the federal level with the extensive infrastructure of the state and university animal disease diagnostic laboratories. Cooperative agreements were awarded by USDA in May 2002 to 12 state and university diagnostic laboratories for a 2-year period. The NAHLN has grown to 58 laboratories (53 state and five federal) in 40 states (see Figure 3-2), and the capability and capacity of the nation’s animal-disease surveillance program have grown with it.

At the federal level, USDA’s National Veterinary Services Laboratory (NVSL) laboratory units in Ames, Iowa, and Plum Island, New York (Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory [FADDL]), serve as the national reference and confirmatory laboratory for veterinary diagnostics, and it coordinates the training, proficiency testing, assistance, and prototypes for diagnostic tests that are used in the state NAHLN laboratories. One component of NVSL’s contribution to the NAHLN is a “train the trainer” program that has increased the number of personnel in NAHLN laboratories who can perform tests for the diagnosis of FADs. The program, offered at FADDL and NVSL, Ames is an example of the successful collaboration between the NVSL and NAHLN laboratories that has resulted in a national network of laboratory personnel who are trained to perform tests for FADs—a resource that did not exist before the NAHLN.

The state and university animal-disease diagnostic laboratories in the NAHLN perform routine diagnostic tests for endemic animal diseases, and they have received specific approval to perform tests for FADs as a part of the national surveillance strategy. A current example of the NAHLN’s value is the diagnosis of the fourth US case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), reported by USDA on April 24, 2012. A sample collected from a dairy cow was submitted to the California Animal Health and Food Safety (CAHFS) laboratory at the University of California at Davis,

an NAHLN laboratory that performs BSE testing through a contractual agreement with USDA. When the CAHFS laboratory determined that the sample was positive, suspect, or inconclusive for BSE, it was sent to the NVSL for confirmation. That procedure is routine and conforms with the established protocol outlined in a Veterinary Services memorandum (VS Memorandum 580.4). Thousands of BSE tests have been performed in NAHLN laboratories in support of USDA’s BSE surveillance strategy. Similar testing agreements for a wide array of animal diseases—including foot-and-mouth disease, classical swine fever, avian influenza, exotic Newcastle disease, chronic wasting disease and scrapie, swine influenza, pseudorabies, and vesicular stomatitis—have been established with NAHLN laboratories nationwide.

The NAHLN effectively demonstrates the value of collaboration between the federal government and state and university animal-disease diagnostic laboratories and may serve as a template for a new relationship among the Department of Homeland Security, USDA, and the NAHLN. Such a new collaboration could accomplish some of the tasks of the proposed National Bio- and Agro-Defense Facility (NBAF) by using infrastructure that already exists in the state and university veterinary diagnostic network, including facilities, professional expertise, and support.

FIGURE 3-2 National Animal Health Laboratory Network. SOURCE: USDA-APHIS (2012).

SOURCE: USDA-APHIS (2012).

Outbreak Response

If the United States identifies a known FAD or a newly emergent disease within its borders, a rapid, comprehensive response is necessary. The type of response will depend on the disease and on whether it is known or newly identified. The historical approach for control of an FAD outbreak has been to quarantine infected premises with diagnostic screening in surrounding zones followed by additional quarantine and diagnostic screening focused on new infected premises with slaughter of infected animals. That approach requires that new cases be rapidly identified with diagnostic assays that have a high level of diagnostic sensitivity and the capability of being performed in a high-throughput manner, particularly in the case of rapidly spreading diseases, such as foot-and-mouth disease. Technological advances in the last few decades have led to the development of direct pathogen identification assays that have very high sensitivity, that target and amplify nucleic acids, and that have the capability of high throughput. The NAHLN has successfully deployed well-validated real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays for detection of foot-and-mouth disease, avian influenza, pandemic H1N1 influenza, classical swine fever, African swine fever, and rinderpest. That would not have been possible without the support of a federal laboratory: initial validation of the assays was conducted at PIADC, where samples from experimentally inoculated animals were vital for early analytical sensitivity testing. Continuing support for reference reagents, proficiency testing, and ensuring that reagents are available in required quantities to respond to a disease outbreak is fundamental to being prepared and responsive during a real event. It is a function that can best be performed by a federally supported program that includes appropriate laboratory biocontainment.

The United States is increasingly incorporating vaccination into outbreak-response plans for FADs. This scientifically sound and justifiable approach is expected by a populace that increasingly respects the value and welfare of agricultural animals beyond their place in the food chain. Vaccines would probably be used strategically in “ring vaccination” to minimize the number of animals that would need to be killed to control an outbreak. Vaccine development has been going on at PIADC for many years, but as a result of the change in outbreak response and the acceptance of regionalization and compartmentalization by OIE, a higher priority has been attached to vaccine development where gaps exist, and the goal is to develop vaccines that allow differentiation of infected from vaccinated animals (“DIVA” vaccines) and diagnostics. Research on vaccine development for FAD agents requires the ability to grow and manipulate an agent, which in turn requires biocontainment at BSL-3, BSL-3Ag, BSL-3E levels, and—for agents such as Hendra and Nipah viruses, hemorrhagic fever viruses, and some arboviruses—BSL-4 level. Equivalent ABSL containment is required for live-animal work. It is important to note that all the viral agents that require BSL-4 containment are zoonotic; that is, none of the livestock-specific FADs require BSL-4 laboratory containment. Nevertheless, a disease outbreak of a zoonotic virus that requires BSL-4 containment would require appropriate

biocontainment of sufficient capacity to handle the large volume of samples that would be obtained from high-risk animals in the outbreak area, whether in a USDA facility, another government facility, or elsewhere in the United States.

Research and Development

Several examples have been provided above and elsewhere in this report of the need for research and development to support all components of the disease-threat triad. There will be a continuing need for a laboratory that has the capability and the authorization to work with FAD and zoonotic disease agents that require biocontainment at BSL-3Ag, BSL-3E, or BSL-4 levels. Vaccine development for FADs may progress as a disease-control strategy and thus it is also a research endeavor that will require support. The United States will need to consider how vaccines might be used for diseases other than foot-and-mouth disease (for example, African swine fever) and whether additional research is warranted. Not all disease threats will require a vaccine-based approach, but for the ones that do, vaccine research will undoubtedly require animal biocontainment facilities at least for proof-of-concept studies. Continued assessment of diagnostic assays for FADs and zoonotic diseases also requires appropriate facilities, and newly arising variants of these diseases could require animal experiments for addressing transmission levels and shedding, both of which can affect analytic sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic assays.

A newly identified agent will require the utmost caution in biocontainment if it belongs to a viral family of known high virulence and transmissibility (such as Hendra virus when it first appeared as an agent of a new disease of horses and humans in Australia) or, if unknown, appears to have high virulence and transmissibility or that does not have known prophylaxis or treatment. Addressing a newly emergent pathogen will undoubtedly require appropriate biocontainment research facilities, and caution might require a high level of biocontainment, up to BSL-4, for diagnostic development work. When a newly arising FAD or zoonotic disease infectious agent is identified, classical research on pathogenesis, virulence, shedding, transmission, and host range and susceptibility is warranted. Research will probably focus on initial diagnostics and agent characterization during an outbreak to allow time for planning additional experiments aimed at understanding the new agent. After disease control, there will be a need for experiments at a defined, and possibly quite high, biocontainment level, including live-animal experiments even if they are limited to production of reference material for diagnostic assays. A centralized federal facility capable of handling emergent agents will sometimes be required until more is known about modes of transmission among animals and from animals to humans. That need will probably depend on initial characterization of the particular agent involved. Caution is warranted, but so is sound assessment of risk-based scientific evidence.

The recent identification of Schmallenberg virus is a good example of an emergent viral agent that may have predictable transmission patterns characteristic of animal diseases in the virus family Bunyaviridae (Kahn and Line, 2011). The virus has not been identified in the United States, so current policy would prohibit working on it outside a federal facility. If it had occurred in the United States, it might be decided on the basis of scientific evidence that the virus can be investigated safely at a biocontainment level found in many diagnostic, research, and development laboratories in the United States. But if a newly arising flavivirus or hemorrhagic fever virus were identified in the United States, utmost caution would be warranted. The recent incidental finding of Ebola Reston virus in a pig sample from the Philippines that was shipped to PIADC for assistance in diagnosing a disease outbreak demonstrates that a high level of biocontainment for newly emergent pathogens is necessary for safe handling and additional studies.

A key question is the extent to which research with FAD and zoonotic disease agents must be limited to a central national laboratory. It is a policy issue that should be addressed on an agent-specific basis and that will affect capacity needs of a centralized federal facility as part of an integrated system for addressing disease threats. It is clear that research on those diseases can occur both in federal facilities and in other laboratories. In the case of diagnostic assays, collaborative approaches have been successful and have used research protocols that require varied levels of biocontainment for different steps of the validation process. The recent development of an assay to detect FMDv in milk (see Box 3-4) is a salient example of the success of collaboration in using the intellectual capital and infrastructure of university, state, and federal laboratories to address a critical gap related to an FAD agent that requires BSL-3E containment. The opportunity for similar collaboration with higher biocontainment depends on the availability of suitable facilities.

Use of the Broad Research Infrastructure and Intellectual Capital of the World

Coincidentally with changes in the national strategy to detect and respond to the potential incursion of FADs (such as creation of NAHLN and DHS), the United States has realized a marked expansion in biocontainment-laboratory capacity and capability. A substantial number of BSL-3 or higher biocontainment laboratories have been constructed by federal and state agencies, universities, and private companies since 2001. They provide an opportunity for collaborations that maximize national efforts to detect and respond to any incursion of an FAD or zoonotic disease. Furthermore, strategic collaborations with other biocontainment facilities would potentially enhance the efficient use of the proposed NBAF.

BOX 3-4

Detecting Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus in Milk: A Case Study of Collaboration

As a result of the second Department of Homeland Security-sponsored Ag Screening Tools Workshop held in April 2011 in Washington, DC (CNA, 2011), stakeholders identified a high-priority need for an assay that would facilitate continuity of business in the dairy and milk processing and distribution industries during a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak. Safe movement of dairy products from production units in or next to the site of infected premises would allow continuity of business and dramatically reduce the overall economic effect of a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak involving the dairy industry. But the safety of milk cannot be ensured without a diagnostic assay that can establish, with high sensitivity, that the milk is free of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDv) and that can be performed in high-throughput mode. Such an assay does not exist. It would require that high-throughput extraction procedures be optimized for a milk and cream matrix, that an internal control be used to indicate inhibition of the assay from factors in milk, and that analytical sensitivity, intra-assay variability, and repeatability be assessed.

Recognizing that priority, the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) undertook a diagnostic-test validation project (technically a methods-comparison project) to evaluate and optimize the methods that could be used for high-throughput extraction of RNA from milk and cream and to assess how well the previously validated real-time PCR assay of FMDv approved by NAHLN for use with oral specimens would work with RNA extracted from milk. The proposed project justification and design were reviewed and approved by the NAHLN Methods Technical Working Group. Initial steps in the validation of high-throughput extraction procedures for the assay used a surrogate construct and could be conducted at BSL-2. That allowed early development work to be performed at a state-based NAHLN laboratory (the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory). Later steps required the use of live FMDv in milk, and multiple strains of virus were needed for complete assessment. That part of the project required use of a BSL-3Ag facility and was conducted at the Plum Island Animal Disease Center; it highlighted the need for this critical core function to be available at a national laboratory.

The project has moved smoothly through the process of validation with seamless collaboration among federal, university, and state partners. It is nearing completion, and if the results of validation indicate that the assay has the required accuracy, it will be an extremely valuable addition to the diagnostic armamentarium for FMDv. The development of the assay from identification and priority-setting through conception and experimental design to generation of the required data took only about a year. In 2012, interlaboratory assessment and negative cohort studies will determine the robustness and diagnostic specificity of the assay and a negative cohort study to examine diagnostic specificity will be conducted in the field. Both those studies can be conducted in the United States. Final validation will require assessment of diagnostic sensitivity in an endemic area. Review of the data and recommendation to the US Department of Agriculture as to whether the assay is fit for the purpose, what additional studies are needed, and what associated protocols and algorithms for use must be developed before deployment will occur through the Methods Technical Working Group dossier-review process.

The development of the assay is an excellent example of research on new diagnostic assays through collaboration among university, state, and federal laboratories. Nothing was compromised through the collaboration, and the timeline was not prolonged. In fact, it could be argued that the timeline was shortened because of the availability of space and personnel time at the Wisconsin laboratory that might not have been available at the federal laboratory. Assay development required approval of a person from the Wisconsin laboratory to work at PIADC and required 2-3 weeks for technology transfer to PIADC. No additional select-agent personnel approval was required. The entire process can serve as a model for development of assays for which only minimal federal facility biocontainment space is needed. However, it could not be undertaken without appropriate biocontainment for some steps of the methods comparison. In the present example, the biocontainment space had to be at an FMDv-approved facility, and this remains a critical core function in an integrated national system.

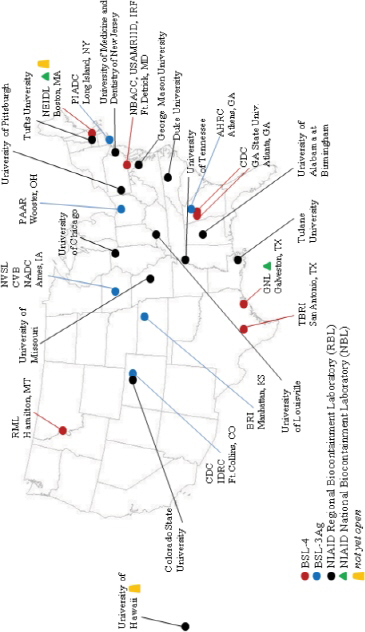

Access to modern and functional BSL-3Ag and ABSL-4 large-animal containment facilities is critical to the national strategy to detect and respond to FADs and zoonotic diseases. Figure 3-3 shows the location of some BSL-3, BSL-3Ag, and BSL-4 laboratories in the United States; Table 3-1 lists those and other laboratories that have high-biocontainment space, and where it is known, large-animal capacity space in high biocontainment. The United States has no facility with ABSL-4 large-animal space, and BSL-3Ag (livestock) capability is available at only a few facilities (listed in Table 3-1). All the BSL-4 laboratories that are operational in the United States are also listed in Table 3-1. A number of international laboratories (see Table 3-2) are engaged in research on FADs and zoonotic diseases, and some of them also have ABSL-4 large-animal capability.

To address the disease threat to humans, including zoonoses, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has assisted in the construction of a network of 13 regional BSL-3 containment laboratories (see Figure 3-3 and Table 3-1). They are generally large facilities that include laboratory space for in vitro and in vivo research and product-development activities addressing emerging infectious diseases and pathogens of bioterrorism concern. Although their focus is on pathogens of human health importance, some may also affect agriculturally important animals.

An indeterminate number of BSL-3 laboratories exist among the laboratories of the NAHLN and in many academic centers, private research organizations, and commercial firms, but they are generally small and have little or no capacity to handle animals. All the human-oriented biocontainment laboratories have biocontainment space dedicated to in vitro research and development, and most have some capability to handle traditional laboratory animals up to small numbers of nonhuman primates.

FIGURE 3-3 Selected federal, state, and national biocontainment laboratory (NBL) and regional biocontainment laboratory (RBL) BSL-3, BSL-3Ag, and BSL-4 facilities. Courtesy of Alisha Prather, Galveston National Laboratory, University of Texas Medical Branch.

|

Capacitya or Capability |

|||

| Facility Name, Location, and URL | BSL-3Ag | BSL-4 or ABSL-4 | |

| US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Other Federal Laboratories | |||

| National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL). Ames, Iowa http://www.aphis.usda.govaninial_healthlab_info_services | 8,581 ft2 (includes 3,109 ft2 for: for NVSL and CVB aecropsy suite); total area | None | |

| Centers for Veterinary Biologies (CVB). Ames, Iowa http://www.aphis.usda.govaninial_healthvet_biologics | See information above | None | |

| National Animal Disease Center (NADC). Ames, Iowa http://www.ars.usda.govMain/docs.htm?docid=3582 | 17,024 ft2 (includes 2,432 ft2 for necropsy suite) | None | |

| Plum Island Animal Disease Center (PIADC). Long Island. New York http://www.ars.usda.govmainsite_main.htm?modecode= 19-40-00-00 | 72,400 ft2 (combined BSL-3Ag and BSL-3E) | None | |

| National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center (NBACC), Ft. Detrick, Maryland; building owned by DHS, but laboratory is managed by a contractor http://www.bnbi.org/ | None | BSL-4 (consisting of 24 individual laboratory spaces); total 5,254 ft2. Four animal rooms (265 ft2 each); total 1,060 ft2. Four ante rooms (140 ft2 each) total 560 ft2. Two necropsy suites (225 ft2 each); total 550 ft2. Capacity: about 2,880 mice, 560 guinea pigs, 42 rabbits per room. | |

| US Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Disease (USAMRIID). Ft. Detrick. Maryland http://www.usamriid.army.mil/ | None | ABSL-4 for handling traditional laboratory animals, such as small rodents and nonhuman primates. | |

| USAMRIID (new building under construction) | None | BSL-4 (17,429 ft2) | |

| Integrated Research Facility (IRF), National Interagency Biodefense Campus of USAMRIID, Ft. Detrick, Maryland http://www.Orf.od.nih.gov/Construction./CurrentProjectsIRFFtDetrick.htm | None | One biocontainment block that can be configured at BSL-3 or BSL-4 or combination (11,000 ft2); eight animal holding rooms with adjacent procedure rooms; intent is to house up to 25 nonhuman primates per room; laboratory not | |

| configured for large animals, such as domestic livestock. Not yet fully operational; expected to be declared "substantially complete" by August 2012. | ||

| National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Rocky Mountain Laboratory (RML); Hamilton. Montana http://www.niaid.nih.govaboutorganizationdirrailpagesoverview.aspx | None | BSL-4 can accommodate mice, hamsters, guinea pigs, ferrets, nonhuman primates. |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Atlanta. Georgia http://www.cdc.gov/ | Four BSL-3E/Ag; each BSL-3E/Ag composed of animal holding room (230 ft2), necropsy room (156 ft2), and BSL-3 main laboratory (710 ft2). Cannot work with swine but in an emergency could handle 10-15 lambs in each animal holding room. | Four BSL-4; each BSL-4 laboratory composed of animal holding room (230 ft2), necropsy room (156 ft2), and BSL-4 main laboratory (1,037 ft2). |

| Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory (SEPRL), USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS), Athens. Georgia http://www.ars.usda.gov/rnairtsite_maiu.htm?modecode=6 6-12-07-00 | BSL-3E space: 9,000 ft2, including 10 bench laboratory rooms, seven animal rooms: over 90% of studies are in chickens, turkeys; ducks; remainder in minor poultry species (quail, geese, pheasants), wild birds, a few laboratory mammals; no space for large animals; most studies done in isolation cabinets designed for poultry, other birds. | None |

| NIAID National Biocontainment Laboratories | ||

| Galveston National Laboratory (GNL), University of Texas Medical Branch; Galveston, Texas http://www.utmb.edu/gnl | BSL-3E for laboratory animals only. | BSL-4: 14.000 ft2 of CDC- and USDA-registered and -approved animal research facilities. |

| National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory (NEIDL); Boston, Massachusetts http://www.bu.edu/neidl/research/ | None | BSL-4 can accommodate 80 nonhuinan primates. 5.000 rodents; not currently operational. |

|

Capacitya or Capability |

|||

| Facility Name, Location, and URL | BSL-3Ag | BSL-4 or ABSL-4 | |

| Private Laboratory | |||

| Texas Biomedical Research Institute (formerly Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research), San Antonio. Texas http://txbiomed.org | One operational ABSL-3 laboratory (2,300 ft2) can accommodate 60 macaques. 24 marmosets. 200 guinea pigs. 120 rabbits. 3,600 mice. | One operational full-suit ABSL-4 laboratory (1.200 ft2) can accommodate: 12 macaques, 12 marmosets. 36 guinea pigs, 24 rabbits. 360 mice. | |

| State and University Laboratories | |||

| Animal Health Research Center (AHRC), University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, Athens, Georgia http://www.vet.uga.edaAHRClAHRC%20facihty%20description.pdf | Eight BSL-3Ag rooms (total 2,840 ft2), six ABSL-3 animal rooms (total 1.500 ft2); total all animal rooms 4.340 ft2; all laboratories operational and approved for select-agent work. | None | |

| Biosecurity Research Institute (BRJ). Kansas State University. Manhattan. Kansas http://www.brik-state.edu/ | Five BSL-3Ag rooms (10,500 ft2). Large-animal holding capacity horses, 6-16 (individual housing [I]), 6-22 (group housing [G]); cattle, 18-36 (I), 16-32 (G); sheep, goats, 32 (I), 128-224 (G); pigs, 10-20 (I), 40-100 (G); ferrets, poultry can also be accommodated. | None | |

| Plant Animal Agro security Research (PAAR). Ohio State University, Wooster, Ohio http://oardc.osu.edu.paart02_pagevie/Home.htm | Four research rooms (each 423 ft2); associated support spaces include necropsy space (850 ft2); research spaces built to BSL-3Ag standards; two laboratory spaces (each 242 ft2) include shower out facility, autoclave access; laboratories built to BSL-3E standards; BSL-3Ag spaces designed to be flexible to incorporate work with agricultural species housed on floor, in cages, isolators or to handle plants as needed. | None | |

SOURCES: USDA, 2012; Personal communications: J.P. Fitch, NBACC, 05/07/2012; N. Woollen, USAMRIID, 05/3/2012 and 05/22/2012; P. Jahrling, NIH/NIAID, 05/30/2012; K. Zoon, RML, 05/4/2012; P. Rollin, CDC, 05/8/2012; D. Swayne, USDA-ARS, 05/23/2012; A. Griffiths, Texas Biomedical Research Institute, 05/30/2012; S. Allen, UGA, 05/22/2012; H. Dickerson, UGA, 05/31/2012; and J. Hanson, OARDC-PAAR, 05/7/2012.

aRoom sizes are net square feet unless indicated otherwise.

TABLE 3-2 Selected International BSL-3Ag and BSL-4Ag/ABSL-4 Laboratories and Their Capacity and Capabilitya

| Name of Facility | Location/URL | Capacityb |

| Canada | ||

| National Centre for Foreign Animal Disease (NCFAD), Canadian Food Inspection Service | Winnipeg, Canada http://www.nnil-lnni.gc.ca/ovefview-apercu-eng.htm http://www.inspection.gc.ca/english/sci/bio/anima/diag/diage.shtml | BSL-4Ag can take two adult cattle (in the 500-lb range and probably slightly bigger); there are plans to convert one BSL-3Ag cubicle into a BSL-3 4Ag swing space, which would increase BSL-4Ag capacity to six cattle (in two rooms of two and four cattle each) |

| Australia | ||

| Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL), Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation | East Geelong, Victoria, Australia http://www.csiro.au/en/Organisation-StructureNational/FacilitiesAustralian-Aninial-Health-Laboratory.aspx | BSL-3Ag (9.418 ft2) Two BSL-4 rooms (1,722.2 ft2; 505.9 ft2) |

| Europe | ||

| Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut (FLI) | Insel Riems, Germany http://www.fli.bund.de/en/startseite/friedrich-loeffler-institut.html | BSL-3Ag facility has eight animal rooms for cattle that can hold a total of 40 cattle with total area of 3,896.5ft2; two animal rooms for pigs or small ruminants each can hold 20 pigs or 16 small ruminants with total area of 699.6 ft2. BSL-4 facility has two animal rooms for cattle that can hold eight cattle (or other livestock species); with total area of 1.420.8 ft2. |

| Institute for Animal Health (IAH) | Pirbright, UK http://www.iah.ac.uk/ |

High-containment animal facilities comply with what United States calls BSL-3Ag+Animal holding rooms for ruminants, pigs, cattle. Total SAPO 4 area approximately 9,536.8 ft2. Future facilities at Pirbright high-containment laboratory for small animals, including future work on highly pathogenic avian influenza. |

| Name of Facility | Location/URL | Capacityb |

| Total capability at 100% occupancy is up to 70 cattle and up to 112 sheep, pigs, or goats at ABSL-3 (would not run facility at 100%—more likely at 60%—because of need to have space for emergency situations). All animal isolation facilities are fully operational. | ||

| Institute of Virology and Immunoprophylaxis (TVI) | Switzerland http://www.bvet.admin.ch/ivi/?lang=en | BSL-3Ag facility has four pig stables and four cattle stables; maximum number cattle per stable, four; maximum number pigs depends on size of animals. Stable surface: about 430.6 ft2 including shower cubicles. |

| Asia | ||

| High Security Animal Disease Laboratory (HSADL) | India http://www.hsadl.nic.in |

Laboratory has good infrastructural facilities for BSL-4 (animal pathogens); 21 scientists four engineers working with biosafety understanding. |

SOURCES: Personal communications: S. Alexandersen, NCFAD, 05/14/2012; P. Daniels, CSIRO, 05/27/2012; T. Mettenleitter, FLI, 05/11/2012; M. Johnson, IAH; 05/15/2012; C. Griot, IVI, 05/15/2012; D.D. Kulkarni, HSADL, 5/16/2012.

aOther similar facilities exist globally, for example in The Netherlands, South Africa, etc.

bRoom sizes are net square feet unless indicated otherwise.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which is part of NIH, supports 11 university-based laboratories designated as Regional Centers of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases (RCEs). The RCEs conduct research on NIH priority pathogens, some of which are agents of FADs and zoonotic diseases that appear on the OIE lists of animal diseases and top animal disease threats in the United States (see Tables 2-1 and 2-3 in Chapter 2).

Most BSL-4 facilities have a common design that couples dedicated in vitro laboratories with adjacent animal rooms, almost always augmented by dedicated rooms for necropsy or animal manipulation. Animal rooms are usually about 200-350 ft2 each and are designed to hold rodents, rabbits, or other small animals in racks; each animal room typically can hold two or more racks. The rooms may also hold nonhuman primates, which are often housed in racks of four individual cages (two up, two down), and a single animal room typically can hold 16 or more nonhuman primates. Widely available modern isolation units isolate individual cages and limit air mixing between cages of many smaller laboratory animals, so it is possible to undertake concurrent experiments with different pathogens by using separate animal cages in the same room “Biobubbles” or “biorooms” can serve the same purpose for nonhuman primates but are less commonly used. Animal rooms used to house nonhuman primates are usually equipped with floor or trench drains with strainers to separate solid waste. They discharge to a central set of reservoirs where waste is sterilized before being discharged into the local sewage system. Floor drains may or may not be in place for animal rooms designed to hold rodents or other small animals.

All solid waste and animal carcasses are sterilized (autoclaved) before leaving the biocontainment laboratory and then usually incinerated. Few of these facilities have large “digesters” capable of processing experimentally infected larger animals. Movement of laboratory animals into biocontainment laboratories often involves the use of elevators and passage through open hallways and loading docks. Waste, animal cages, and bedding are sterilized in double-door autoclaves as the material leaves the laboratory. Equipment and other implements can also be decontaminated in an air lock in which a gas (formaldehyde) or vapor (hydrogen peroxide) is used to fumigate the items. Materials that have been autoclaved or fumigated are then usually cleaned and prepared for reuse at a central facility, often in the laboratory complex.

The handling of agriculturally important animals in existing BSL-4 facilities is challenging but not impossible, although no such facility in the United States is designated as ABSL-4 for large animals. Some facilities are exploring the use of miniature goats or pigs for experimental infection with agriculturally important BSL-4 pathogens, such as Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Nipah, and Hendra viruses. There are many challenges in conducting such experiments,

including movement of animals from the supplier into the biocontainment laboratory, animal husbandry and waste management during experimentation, manipulation of large animals in the BSL-4 environment, necropsy procedures, and decontamination of animal carcasses after experimental infection. Those challenges are more fully discussed below.

Choice of Animals

Miniature goats, pigs, young lambs, and perhaps miniature horses could be used for experimental infections in existing BSL-4 facilities in the United States. Larger animals, such as horses and cattle, would present major hurdles and are probably not practical apart from true emergency conditions. The number of individual animals able to be tested at a given time will be small, and this could make it difficult to demonstrate statistically significant results. Special equipment for safe handling of any large animals would have to be procured and installed.

Delivery of Animals

Many existing BSL-4 laboratories are not on the ground level of the buildings that house them. Therefore, animals would need to be moved from a transport vehicle to a biocontainment facility by using existing delivery docks, hallways, and elevators that were not designed for movement of large animals. That problem could be overcome by using crates or other containers for some species and restricting access while animals are being moved.

Animal Husbandry

Animal husbandry is likely to be one of the most challenging aspects of the use of domestic animals in existing biocontainment facilities. Special flooring will be needed to allow efficient waste removal and to provide adequate footing for and protection of hoofed animals. Individual corrals can be purchased and installed, or animals can be group-housed in a designated portion of an animal room. Special arrangements will be required for feed and water.

Monitoring Animals

Individual animals can be monitored for vital signs, such as body temperature, with implanted sensors and telemetry. However, direct handling of individual animals for inoculation or to obtain periodic blood samples or other specimens would require the installation of appropriate constraint devices and their use by trained personnel to facilitate the safe handling of the animals during such manipulations.

Necropsy and Carcass Disposal

Most necropsy facilities that are now in place are designed to handle laboratory animals that are the size of nonhuman primates or smaller. Special adaptations might be required to process larger animals, and preparation of carcasses to ensure sterilization on completion of studies will be difficult. Disposal of larger animals after sterilization would require specialized large incinerators that may not be locally available.

Institutional Oversight

All animal experimentation must be reviewed and approved by an institutional animal care and use committee, and the handling of dangerous pathogens must be cleared by an institutional biosafety committee. Those committees ensure that work to be done meets all existing national standards and that it can be accomplished safely and securely. In most instances, the institutions will not have had experience in handling large livestock species, particularly those being experimentally infected with infectious agents. Convincing the committees that domestic animals can be manipulated safely and securely under humane conditions in facilities adapted to accommodate large animals will require careful planning, effective leadership, and a strong partnership between the scientific investigators and the laboratory animal resources team.

International Resources

BSL-4 laboratories outside the United States that have the capacity to handle large animals are shown in Table 3-2. Each facility has the ability to handle large domestic animals and some of these laboratories have experience working with agents that are not currently in the United States but are of research interest and could be newly introduced into the country (for example, Hendra and Nipah viruses at the Australian Animal Health Laboratory in Geelong). Depending on the situation when a request is made, they may be willing to collaborate with US scientists to investigate pathogens that require BSL-4 containment. Their primary responsibility is, of course, to their own national governments and domestic needs.

National and international resources and biocontainment infrastructure for addressing the threat of FADs and zoonotic diseases have expanded substantially since 2001. A discussion of some of the requirements and challenges associated with the design and construction of international high-containment laboratories may be found in the report entitled Biosecurity Challenges of the Global Expansion of High-Containment Biological Laboratories (NAS and NRC, 2012). Can components of the ideal system for countering disease threats use these existing resources effectively? The answer is a cautious yes. However, the chal-

lenges in using the highest level of biocontainment space (ABSL-4), particularly for large-animal research and diagnostic development, are not insignificant.

Adaptability and Flexibility for the Future

Technology

Diagnostics, detection, vaccine development, and therapeutics are primary research necessities to maintain US agricultural strength. The scientific and technological needs of the diagnostic and response capability of the United States were outlined in the 2003 National Research Council report Countering Agricultural Bioterrorism:

“There are needs and opportunities for aggressive research in both science and technology to improve our ability to prevent, detect, respond to and recover from biological attacks on agricultural plants and animals. The scientific knowledge and the technological developments for protecting plants and animals against naturally occurring or accidentally introduced pests and pathogens constitute a starting point for these efforts—but only a starting point—and there is much more to be done” (p. 67, NRC, 2003).

Knowledge of naturally occurring agents is itself limited, and the landscape is complicated if one considers intentional introduction of existing or novel “synthetic” threat agents. Identification and characterization of existing pathogens continue to accumulate at rates that are increasing dramatically as a result of new technologies, such as next-generation sequencing. In general, diagnostic tests are moving away from antibody-based, single-pathogen laboratory assays toward nucleic acid-based, multiple-pathogen point-of-care tests. None have yet been considered fit for the purpose of diagnosing FADs of livestock (whose prevalence is virtually zero). However, a survey of recent developments in biotechnology suggests that new, effective methods for diagnosing and tracking human diseases are available or on the near horizon, application to companion-animal diseases has already occurred, and further development for diseases of livestock will follow.

Nanotechnology and microfluidics have contributed to the burgeoning of detection technologies. For example, several advances in nucleic acid-based detection devices will allow diagnosis of known infections—even of infection with BSL-3 organisms—in the field or in the local laboratory. Many of the new devices, such as lateral-flow (hand-held or dipstick) assays for using both nucleic acid and immunoassays, lead to complete independence from laboratory instrumentation. Novel variations on the original PCR assay include (among many) loop-mediated isothermal amplification, molecular beacons, multiplexed

assays, twisted intercalating nucleic acid stabilizing molecules, and dA-tail capturing. Simultaneous interrogation of multiple sequences representing multiple bacterial and viral pathogens is provided by such systems as “lab-on-a-chip” designs and DNA-RNA microarrays; originally requiring laboratory access, these multiplex approaches have recently been adapted to lateral-flow platforms for field use.

Nucleic acid-based and antibody-based platforms are most widespread, but direct chemical analysis of organisms with matrix-assisted laser desorptionionization time of flight mass spectrometry is also possible. Identification is based on protein profiles of bacterial pathogens, viral glycoproteins, or even multiplexed PCR products. Microorganism-based biosensing methods—such as optical, surface plasmon resonance, amperometric, potentiometric, whole-cell, electrochemical, impedimetric, and piezoelectric methods—are being adapted from food-based assays to clinical use.

Despite substantial advances in detection specificity and sensitivity, there is the remaining problem of sample concentration, as discussed above. Early stages of infectious diseases may have few organisms in accessible tissues. For example, early in Bacillus anthracis infection, few bacteria are in the bloodstream despite rapid replication because the bacteria are transported into the lymph nodes by dendritic cells (a subset of immune cells involved in early responses to infection) and are not accessible in traditional tissue sampling. By the time a suitable number of bacteria are present for diagnosis, the infection is rampant and usually fatal. Among the solutions to the problem are detection systems that have highly effective concentration methods that have been developed for such diseases as tuberculosis and malaria. Those systems (such as GeneXpert and DetermineTM TB-LAM) rely on automation of complex, time-consuming procedures and encase an entire process in sealed cartridges with excellent safety records and reduce the time needed to confirm a diagnosis with high specificity and sensitivity.

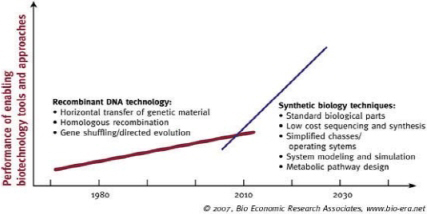

Finally, exponential increases in technology innovation are fueled by intense competition among companies and countries that have marked effects on research and development. Figure 3-4 shows the rates of performance improvement in two sets of technologies: recombinant DNA and synthetic biology (including rapid and low-cost DNA sequencing) (Aldrich et al., 2007). For example, revolutionary advances in DNA sequencing methods (next-generation, deep, and massively parallel sequencing) herald a time when tissue samples from infected animals can be subjected to genome sequencing even without the need for isolation of the organism. As of May 13, 2012, the complete DNA sequences of 11,681 prokaryotes and 3,097 viruses had been posted,11 and cost and time for sequencing are decreasing at an unprecedented rate; third-generation (single-molecule) sequencing will undoubtedly further revolutionize the field.

![]()

11 URL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/browse/ (accessed May 12, 2012).

FIGURE 3-4 Rates of performance improvement of recombinant-DNA technology and synthetic biology.

SOURCE: Aldrich et al. (2007). Reprinted with permission from Bio Economic Research Associates, LLC (bio-era™). All rights reserved.

High biocontainment will be required in the near term for development, testing and validation of some of those approaches. Eventually, their application to plant and animal health will reduce, but not eliminate, the requirement for specialized laboratory space.

50-Year Lifespan of the Facility

With forethought and proper planning, the design of a facility with a lifespan of 50 years would take into account changes that might take place during the life of the building. They include changes in policy, research priorities, technological developments, societal norms, and global interactions. For example, as noted above, technological advances will shorten the time to diagnosis and expand the array of infections detectable with point-of-care or pen-side assays and reduce laboratory-based testing. Single catastrophic events, such as a massive outbreak or a terrorist event, can change the landscape of a research field and its associated policies.

The decade after the 9/11 and 2001 anthrax attacks in the United States saw unprecedented changes in the regulatory and oversight environment for biomedical research in the United States. The confluence of those two events had substantial effects on laboratory security and safety procedures that limited access to dangerous pathogens and altered research priorities. Similar increased awareness of security and safety issues has occurred on a global level. The new regulatory environment—on both the national and the international levels—is subject to constant adjustment and adaptation, and therefore would require that greater emphasis be placed on the harmonization of regulations: future national

animal agricultural infrastructure and policies would need to be planned with the potential for these changes in mind.

Similarly, societal values and public attitudes related to the welfare of agricultural animals continue to evolve (Blokhuis et al., 2008). Organizations such as OIE are actively promoting the importance of integrating animal health, animal welfare, and food safety. Although the United States currently does not legislate food animal welfare,12 the European Commission recently adopted a new 4-year strategy (2012-2015) to improve the welfare of animals in the European Union.13

Research and development in animal protection will require BSL-3Ag and ABSL-4 for decades to come. Researchers will need to understand disease pathogenesis to develop efficient detection and diagnostic methods or new vaccines. For example, some animals immunized with inactivated foot-and-mouth disease vaccines are still capable of maintaining persistent infection (Kitching, 2002). The variability of foot-and-mouth disease serotypes restricts the use of existing vaccine stocks in an outbreak until a full epidemiological characterization has been carried out and studies to determine whether the vaccine will provide sufficient immunity against the viral outbreak strain have been conducted (Rodriguez and Gay, 2011). Furthermore, if vaccines are used to control an outbreak, the ability to detect infection in vaccinated animals and to differentiate between infected and immunized animals is required if animal products are to be moved within the country and globally. As more is understood about disease progression and virulence determinants in infection, attenuated or recombinant viral vaccines will be produced by using reverse-engineering and other synthetic technologies, with serotype specificity and DIVA properties. Development of such a vaccine is well advanced in the United States and abroad. Those and other novel vaccine-production platforms are essential for rapid response to foot-and-mouth disease outbreaks and will need to be tested in large animals in strict containment. The committee notes that one such foot-and-mouth disease vaccine was licensed recently (June 2012). This vaccine was a product of PIADC and USDA-ARS research in cooperation with DHS and the private sector.14

Vaccine development for agents that are emerging as high-priority disease threats may also require high biocontainment. Bunyaviruses, such as Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus and Rift Valley fever virus, are the causative agents of devastating diseases and have an expanding host and geographic range. Investigation of those agents in livestock species is necessary. Recent advances in research methods such as infectious-virus rescue, novel electron microscopic techniques, and high-resolution structural analysis have been ap-

![]()

12 See URL: http://awic.nal.usda.gov/farm-animals/animal-welfare-audits-and-certification-programs (accessed May 31, 2012).

13 See URL: http://ec.europa.eu/food/animal/welfare/actionplan/actionplan_en.htm. (accessed May 31, 2012).

14 See URL: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/genvec-announces-conditional-approval-of-fmd-vaccine-for-cattle-157766595.html (accessed June 29, 2012).

plied to both emerging bunyaviruses and model species (Walter and Barr, 2011). The study of those agents has high priority in view of the lack of vaccines and therapeutics for their treatment and control and requires high biocontainment.

Finally, the committee also recognizes that there are international research efforts to develop vaccination studies that involve no challenge infections of animals with live virus. These studies are critical for the large number of countries recognized by the OIE as “foot-and-mouth disease-free with vaccination” whose foot-and-mouth disease research facilities are unable to use live FMDv for any studies or challenges. Efficacy studies for FMDv would be based solely on the evaluation of immune response elicited by vaccination, as is already happening in the case of foot-and-mouth disease vaccines manufactured in South America under guidelines of the Pan-American Foot-and-Mouth Disease Center (PANAFTOSA). It is expected that efforts to develop alternative efficacy studies of new vaccines without experimental challenge infections of live animals will continue to evolve given regulatory and societal pressures to limit the number of animals used in infectious disease research, with an obvious impact on the capacity needed for animal studies in high biocontainment.

Despite the marked expansion of high-biocontainment space in the United States since 2001, there remains no national ABSL-4 large-animal facility. Similarly, although BSL-3Ag containment space has expanded through construction of several new facilities (for example, the Biosecurity Research Institute and the National Animal Disease Center), the facilities at PIADC dedicated to FADs are dated and increasingly cost-inefficient. Thus, there is a critical national need for a dedicated facility that has modern BSL-3Ag and ABSL-4 large-animal capabilities. It would serve as the hub of the national strategy for the detection of and response to any incursion of an FAD. It would also be used for the study of infectious diseases of public-health importance in which livestock serve as key reservoir or amplifying hosts.

US programs for detection of and response to FADs (those proposed to be located at the NBAF) would need to interface with similar activities and programs of the National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the US Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases, USDA, NIH, and academic and state institutions to maximize efficiency and intellectual resources through interdisciplinary research that crosses traditional agency boundaries. Such interagency working relationships may have challenges, but would be essential for maximizing the use of the NBAF as well as other existing BSL-3Ag, BSL-4 and ABSL-4 laboratories in the United States and the skilled workforce they employ. The rapidly evolving nature of disease threats confronting the animal industries of the United States and the technologies available to detect and respond to them demand a flexible and nimble strategy for programmatic and facility design. With

that background, in Chapter 4 the committee considers in more detail the three options presented in its statement of task: constructing the NBAF as currently designed, scaling back the size and scope of the proposed NBAF, and maintaining the current PIADC and leveraging US capability and capacity through international laboratories that have ABSL-4 large-animal space.

Aldrich, S.C., J. Newcomb, and R. Carlson. 2007. Figure 1-2. An inflection point for biological technology. In Genome Synthesis and Design Futures: Implications for the US Economy. Bio-era.net [online]. Available: http://www.bio-era.net/reports/genome.html (accessed June 5, 2012).

Baker, M.G., and D.P. Fidler. 2006. Global public health surveillance under new international health regulations. Emerging Infectious Disease 12(7):1058-1065.

Berns, K.I., A. Casadevall, M.L. Cohen, S. Ehrlich, L.W. Enquist, J.P. Fitch, D.R. Franz, C.M. Fraser-Liggett, C.M. Grant, M.J. Imperiale, J. Kanabrocki, P.S. Keim, S.M. Lemon, S.B. Levy, J.R. Lumpkin, J.F. Miller, R. Murch, M.E. Nance, M.T. Osterholm, D.A. Relman, J.A. Roth, and A. Vidaver. 2012. Adaptations of avian flu virus are a cause for concern. Science 335(6069):660-661.

Blokhuis, H.J., L.J. Keeling, A. Gavinelli, and J. Serratosa. 2008. Animal welfare’s impact on the food chain. Trends in Food Science and Technology 19 (suppl. 1):S79-S87.

Brownlie, J., C. Peckham, J. Waage, M. Woolhouse, C. Lyall, L. Meagher, J. Tait, M. Baylis, and A. Nicoll. 2006. Foresight. Infectious Diseases: Preparing for the Future. Future Threats. London: Office of Science and Innovation [online]. Available: http://www.bis.gov.uk/assets/foresight/docs/infectious-diseases/t1.pdf (accessed June 4, 2012).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2009. Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL), 5th Ed. (CDC) 21-1112. [online]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/biosafety/publications/bmbl5/BMBL.pdf (accessed June 5, 2012).

CNA. 2011. Enhancing Ag Resiliency: The Agricultural Industry Perspective of Utilizing Agricultural Screening Tools. Report from the Agricultural Screening Tools Workshop, April 2011, Washington D.C. College Station, TX: National Center for Foreign Animal and Zoonotic Disease Defense, Texas A&M University [online]. Available; http://fazd.tamu.edu/files/2011/06/ASTII-Report-FINAL.pdf (accessed June 5, 2012).

Enserink, M., and J. Cohen. 2012. One H5N1 paper finally goes to press; Second greenlighted. Science 336(6081):529-530.

Fidler, D.P. 2005. From international sanitary conventions to global health security: The new international health regulations. Chinese Journal of International Law 4(2):325-392.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003. Microbial Threats to Health: Emergence, Detection, and Response. M.S. Smolinski, M. A. Hamburg, and J. Lederberg, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM and NRC (National Research Council). 2009. Sustaining Global Surveillance and Response to Emerging Zoonotic Diseases. G.T. Keusch, M. Pappaioanou, M.C. Gonzalez, K.A. Scott, and P. Tsai, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kahn, C.M., and S. Line, eds. 2011. Akabane virus infection. The Merck Veterinary Manual. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck [online]. Available: http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/50804.htm (accessed June 29, 2012).

Kitching, R.P. 2002. Identification of foot and mouth disease virus carrier and subclinically infected animals and differentiation from vaccinated animals. Scientific and Technical Review 21(3):531-538.

NAS (National Academy of Sciences) and NRC. 2012. Biosecurity Challenges of the Global Expansion of High-Containment Biological Laboratories: Summary of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASDARF (The National Association of State Departments of Agriculture Research Foundation). 2001. The Animal Health Safeguarding Review: Results and Recommendations, October 2001 [online]. Available: http://www.aphis.usda.gov/vs/pdf_files/safeguarding.pdf (accessed June 8, 2012).

NRC (National Research Council). 2003. Countering Agricultural Bioterrorism. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

OIE (World Organization for Animal Health). 2010. Chapter 1.2 Criteria for Listing Diseases Article 1.2.1. Terrestrial Animal Health Code 2010 [online]. Available: http://web.oie.int/eng/normes/mcode/en_chapitre_1.1.2.pdf (accessed June 1, 2012).