Improving and Accelerating Therapeutic Development for Nervous System Disorders: Workshop Summary (2014)

Chapter: 4 Target Validation

Key Points

• Establishing pharmacologically relevant exposure levels and engagement are two key steps in target validation.

• There is a need for better biomarkers to objectively measure biological states and therapeutic effects.

• In addition to target validation, several participants highlighted the importance of rapid target invalidation.

• Understanding and examining the specific metrics of target validation and qualification may be useful for portfolio assessment.

• Going directly into first-in-human trials might be feasible for highly validated targets.

NOTE: The items in this list were addressed by individual speakers and participants and were identified and summarized for this report by the rapporteurs, not the workshop participants. This list is not meant to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Target validation ensures that engagement of the target has potential therapeutic benefit; like target identification, this is a critical step in drug development. If a target cannot be validated, then it will not proceed in the drug development process. Early validation of targets along with improved biomarkers were two opportunities discussed by Samuel Gandy, professor in the departments of neurology and psychiatry and associate director of Mount Sinai’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, and Reisa Sperling, director of the Center for Alzheimer’s Research and

Treatment and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School. In addition, Kalpana Merchant, chief scientific officer of Tailored Therapeutics–Neuroscience at Eli Lilly and Company, offered a portfolio assessment tool outlining specific metrics for target validation and qualification, which could help assess confidence in a drug throughout the development process.

EARLY VALIDATION OF TARGETS

Gandy discussed how early validation of targets can accelerate therapeutic development using examples from Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and traumatic encephalopathy1 (acute and chronic). One pathological feature shared by these conditions is abnormal extracellular deposits of β-amyloid42.2 In the case of AD, the accumulation of β-amyloid42 or its assembly form, oligomeric β-amyloid, begins as early as 15 years prior to symptoms (Rowe et al., 2010).

Gandy evaluated β-amyloid42 and oligomeric β-amyloid against a list of criteria for an ideal drug target to determine whether or not they were strong targets for therapeutic development (see Box 4-1). Gandy noted that β-amyloid42 fulfills most of the criteria, with three exceptions: (1) there is ambiguous evidence regarding proven function in pathophysiology of diseases; (2) it is uniformly distributed throughout the body, which can lead to peripheral side effects when modulated; and (3) a biomarker for monitoring therapeutic efficacy or target modulation is not entirely perfected. However, Gandy noted that even though there is much interest in oligomeric β-amyloid because some experts believe it may be the toxin associated with many degenerative diseases, it is not a well-established drug target, and there are currently limited biomarkers for this peptide (Reitz, 2012).

Gandy suggested that the current paradigm of drug development might require change, and that change might best occur via the development of novel approaches such as timing of the intervention; novel systems for screening drugs; novel approaches to known targets; and development of novel biological antagonists against aggregated proteins.

______________

1Diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure (e.g., trauma, tumor, infectious agents, etc.) (NINDS, 2010).

2β-amyloid42 is a fragment of the amyloid precursor protein with 42 amino acids. There are other β-amyloids that range from 37 to 49 amino acids.

BOX 4-1

Properties of an Ideal Drug Target

• Disease modifying and/or proven function in the pathophysiology

• Highly selective to reduce adverse events

• If needed, a three-dimensional structure for the target is available

• Target has favorable “biochemical and/or cellular assays for binding and function,” enabling high-throughput screening

• Can be validated experimentally for a specified indication; therapeutic use might be broadened to additional indications

• Genomics and phenotypic screening may add to the understanding of the disease model and predictive validity of potential side effects (e.g., knockout mouse, somatic mutations, etc.)

• A mechanistic biomarker exists to monitor efficacy

• The use of the target does not infringe on the intellectual property rights of others (no competitors on target, freedom to operate)

SOURCE: Adapted from Gashaw et al., 2011.

In particular, Gandy’s laboratory is interested in this last strategy for Alzheimer’s disease: the prevention of β-amyloid production at the synapse through development of antagonists. Gandy and colleagues studied the generation of β-amyloid in synaptosomes3 in a mouse with the human transgene for APP. When the investigators depolarized the synaptosomes, the depolarization activated secretases that selectively spliced APP into β-amyloid42, but not β-amyloid40 (Kim et al., 2010). That finding propelled them to search for transmitter signaling pathways that mimic depolarization. They found that an agonist for Group II metabotropic glutamate receptor also selectively produced β-amyloid42 in the synaptosomes. Having established the signaling pathway, they then sought to block β-amyloid42 production by pretreatment with a Group II metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist, which was successful in inhibiting generation of β-amyloid42 (Kim et al., 2010).

Employing this novel strategy led to administration of two different Group II glutamate antagonists in the transgenic mouse. The drug BCI-838 was found to reduce oligomeric β-amyloid accumulation. Behaviorally, the drug improved learning and reduced anxiety behaviors. Results also show increased neurogenesis using three different markers of proliferation. Gandy raised the question of whether neurogenesis can act as an

______________

3Synaptosomes are isolated intact nerve terminals.

unconventional biological antagonist of β-amyloid toxicity. He and colleagues are now testing BCI-838 in Phase I studies. Thus far, they have shown that BCI-838 is well tolerated in healthy controls. The next step is to test the drug in a geriatric population diagnosed with prodromal or mild AD. Gandy and colleagues are also considering the drug for use in tauopathies and TBI. In summary, Gandy suggested that the drug discovery paradigm for AD and other diseases could potentially change through the use of novel approaches outlined.

A NEED FOR BETTER BIOMARKERS

Sperling discussed the utility of biomarkers for AD. Their greatest utility, in her view, is for selecting participants for clinical trials who have target pathology by measuring and predicting disease progression or prognosis and assisting with patient stratification (IOM, 2011). However, the greatest challenge is that there are deficiencies in the number of biomarkers currently available that track and predict therapeutic response. Two clinical trials of monoclonal antibodies against β-amyloid showed lower β-amyloid with positron emission tomography (PET) amyloid imaging as the biomarker. The issue was that the antibodies did not improve cognition in these Phase II studies (Ostrowitzki et al., 2012; Rinne et al., 2010). Better biomarkers are needed of synaptic dysfunction, which, according to the β-amyloid hypothesis, occurs much earlier than cognitive decline. Biomarkers of synaptic dysfunction—using new imaging modalities such as task-functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and resting state (task-free) functional connectivity, or fc-MRI—could be studied along with PET amyloid imaging to determine the benefits of anti-β-amyloid therapies. For example, fMRI and PET amyloid imaging were combined to study asymptomatic and minimally impaired older individuals to demonstrate that amyloid pathology was linked to neural dysfunction of the default network in cortical regions implicated in AD (Sperling et al., 2009). Imaging modalities may be better as useful measures of therapeutic response, because cognitive impairment occurs too late in the disease process of AD. However, imaging does not constitute a surrogate endpoint, but rather a correlate that is a measurement of biological activity (Fleming and Powers, 2012).

Sperling suggested potential solutions for targeting and developing biomarkers for β-amyloid that might also apply to other nervous system disorders:

• embed multiple biomarkers in Phase I/IIa trials in order to develop pharmacodynamic profiles quickly;

• develop synaptic and other biomarkers in humans that can give a functional readout in a short timeframe;

• test drugs aimed at upstream processes before irreversible downstream damage;

• find more potent drugs without dose-limiting toxicity; and

• use combination therapies and start them before symptoms appear.

In the case of psychiatric disorders and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria, John Krystal, Robert L. McNeil, Jr., professor of translational research and chair of the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine, commented there needs to be a willingness to explore subgroups of patients with mechanistic homogeneity. Connecting genetic networks and quantitative traits might build the case for proof-of-concept studies; the studies would be based on quantitative information rather than behavioral readouts and could be tested in specific patient groups. In summary, Chas Bountra, head of the Structural Genomics Consortium and professor of translational medicine at the University of Oxford, noted that unless biomarkers are discovered, the field faces continued high failure rates in Phase IIa clinical trials. At this stage of drug development, the majority of novel compounds fail (Paul et al., 2010). As a result, target validation, or invalidation, is delayed.

PORTFOLIO ASSESSMENT TOOL FOR TARGET VALIDATION AND QUALIFICATION

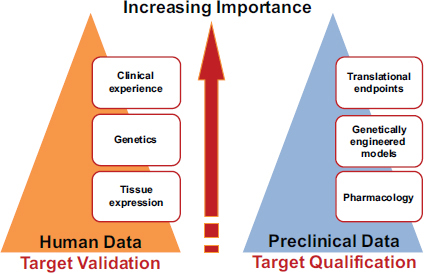

Merchant provided her perspective on factors considered when making investment decisions in neuroscience portfolios. Merchant began by noting that attrition in drug development is very high in Phase II studies, with an approximate rate of 66 percent. Major causes of failure in Phase II are related to inadequacies in efficacy, safety, the overall strategic plan, and bioavailability and pharmacokinetic properties (Paul et al., 2010). High attrition underscores the need for better target validation and biomarkers to avoid selection of the wrong target, the wrong patient population, or the wrong dose. Merchant suggested that target validation is best accomplished in humans, while animal models are important for

target qualification, which is a step in the process to determine the scientific validity and safety of a target (see Figure 4-1).

Target Validation

There are three major components of target validation using human data: tissue expression, genetics, and clinical experience. For each of these components, several metrics might guide decisions to invest in a particular therapy (see Figure 4-1). Merchant identified specific metrics that might apply in ascending order of priority (see Table 4-1).

Merchant noted that each step toward target validation provides an increasing level of importance on how to interpret data and build confidence in what projects to bring forward. All the components—tissue expression, genetics, and clinical experience—can inform disease pathways. It is an iterative learning problem. How can what is learned from tissue expression integrate with genetics and integrate with the clinic?

FIGURE 4-1 Major components of target validation and qualification.

SOURCE: Merchant presentation and Lilly Research Laboratories, April 9, 2013.

TABLE 4-1 Metrics of Target Validation

| Components of Target Validation |

Metrics Increasing Confidence |

|||

| Pharmacology | Target protein is expressed or active in the desired organ/subregion/cell types | Target mRNA expression is altered by the disease | Target protein expression is altered in disease/tissue | |

| Genetically Engineered Models | Genetic association with disease occurs in small, underpowered, or non-replicated studies without knowing the function of the variant | Polygenic association with modest effect size and known function of the variant, or association with common, low-risk variant in a gene that also has rare variant associated with large effect size, or in the best case | Monogenic association with large effect size and known function of gene variant | |

| Translational Endpoints | Clinically relevant efficacy observed in a small trial, but knowledge of engagement of specific target/pathway is lacking | Clinically relevant efficacy is observed with at least one ligand with a different mode of target modulation or with two ligands on biomarkers previously shown to predict efficacy | At least one ligand with an analogous mode of action on the target/target pathway has “approvable” efficacy in the indication of interest and robust evidence of target engagement | |

NOTE: mRNA = messenger ribonucleic acid.

SOURCE: Merchant presentation, April 9, 2013.

Target Qualification

Target qualification consists of evaluating a target to ensure that it has a clear role in the disease process (Cambridge Healthtech Institute, 2013). Three major components of target qualification in preclinical data, according to Merchant, are pharmacology, genetically engineered models, and translational endpoints (see Figure 4-1). For each component, Merchant specified metrics that could be used to guide decisions and in what order of priority (see Table 4-2).

Merchant concluded by saying that the outlined metrics and components could be used as a portfolio management tool for target assessment. Merchant also emphasized the need for researchers to conduct molecular phenotyping of disorders in order to create molecularly defined disease states and not simply syndromes. During the discussion, a participant asked how researchers can know, definitively, when a target is invalidated. Merchant suggested examining target engagement in clinical trials within the targeted population.

Several participants noted that it is possible to move directly into clinical trials for highly validated targets. However, Krystal said researchers cannot go directly into the patient population without knowing whether the biology of the animal models applies to healthy humans. The drug development process is exploratory; it is an iterative process of testing specific mechanistic hypotheses across cellular and animal studies, healthy human subjects, and clinical trials. A participant asked if going into first-in-human trials would be an appropriate risk–benefit decision for serious conditions with short life expectancies such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Merchant agreed that it would be appropriate and said that is the case for oncology drugs in which researchers and companies go to first-in-human trials in patients with clear biomarkers. Target validation is a multilayered step in drug development that is critical to the success of a drug. Validated targets and biomarkers, along with assessment tools, are needed to ensure that the drug is actively engaging the target to produce an expected therapeutic effect.

TABLE 4-2 Metrics of Target Qualification

| Components of Target Validation |

Metrics Increasing Confidence |

|||

| Pharmacology | A pharmacological tool (e.g., a small molecule, antibody, or peptide) modulates disease associated with pathway in vitro or in heterologous cell lines at appropriate concentrations | Ligands with the intended mode of action modulate disease-associated pathway ex vivo or in native tissue, or in the best case | Ligands with intended mode of action modulate disease-associated pathway in vivo and target engagement–activity relationships are established | |

| Genetically Engineered Models | Genetic modulation in a non-mammalian model organism produces disease- or treatment-relevant phenotype | Genetic modulation in a rodent/nonhuman primate produces disease-relevant endophenotype | Human pathogenic mutation of the target in a rodent/primate mimics disease pathway and/or genetic modulation of the target mitigates the same | |

| Translational Endpoints | Target or pathology is known and demonstration of target pharmacology identical to human native tissue assays | PK/PD relationship and margin of safety are established using a translational biomarker of target engagement/modulation | PK/PD relationship and margin of safety are established using a translational biomarker historically associated with clinical efficacy | |

NOTE: PK/PD = pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic.

SOURCE: Merchant presentation, April 9, 2013.

This page intentionally left blank.