Advancing Workforce Health at the Department of Homeland Security: Protecting Those Who Protect Us (2014)

Chapter: 9 Considerations for Implementation

9

Considerations for Implementation

In the last decade, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has made considerable progress toward addressing the complex management challenges that accompanied its formation, including the need to transform disparate component health protection infrastructures into a coordinated and interconnected system. Still, additional hurdles remain that must be overcome if DHS is to achieve the mature health system required by its workforce and those in its care and custody. Advancing workforce health at DHS will require up-front investments, political will, and stakeholder buy-in across all levels of the organization—knowing even where to begin can be its own challenge—but the potential benefits are considerable. This chapter outlines some final considerations for implementation of the committee’s recommendations, including projected benefits and priorities.

IMPACT OF AN INTEGRATED HEALTH PROTECTION INFRASTRUCTURE

The committee was asked to consider the impact of its recommendations on mission readiness, health care costs, and liability at DHS. Clearly, concern for the health and safety of the workforce and those in DHS’s care, not cost savings, should drive changes to the department’s health protection infrastructure. Nonetheless, the committee recognizes that in the current fiscally constrained operating environment, adoption of its recommendations may require a strong business case. Although the committee lacked the information (e.g., investment costs) and time needed to conduct a formal impact analysis for the implementation of its recommendations, projected

BOX 9-1

Projected Benefits to DHS of an Integrated

Health Protection Infrastructure

Mission Impacts

- Increased availability for missions

- Improved interoperability for better coordination during planned and contingency operations

Cost Savings

- Reduced costs associated with injuries, including workers’ compensation costs

- Reduced costs associated with emergency room visits for detainees

- Cost savings from economies of scale (e.g., bulk purchasing and contracted services)

Liability

- Increased protection against equal employment opportunity suits

- Fewer lawsuits due to detainees not receiving appropriate care and fewer citations from the DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties

- Reduced liability associated with provision of medical services by improperly credentialed providers

Other Benefits

- Improved morale

- Improved employee health

benefits (summarized in Box 9-1) are described below and may be of use to DHS in the development of more rigorous business cases.

Mission Impacts

Given the operational nature of DHS, mission success depends on the availability of employees to participate in routine, planned, and contingency operations. It follows that workforce health and safety are essential factors in mission readiness. Although impacts of employee health programs often are measured in terms of decreased costs and injury rates, mission availability is a powerful measure of the combined effectiveness of preventive, curative, and rehabilitative interventions. Implementation of an employment life-cycle approach to mission readiness (Recommendation 7) and a comprehensive operational medicine program (Recommendation 8), both of which emphasize prevention, medical treatment, and rehabilitation, would

enable DHS to increase the number of employees available to participate in operations. For example, the Federal Air Marshal Service (FAMS), which described to the committee an approach consistent with the employment life-cycle framework shown in Figure 7-1 (Chapter 7), reported a 20 percent reduction in the number of mission opportunities lost between 2009 and 2010 (FAMS, 2013).

In addition to employee injuries and illnesses, the medical needs of detainees1 impact mission availability. A business case for the Southwest Border Initiative proposed by the Office of Health Affairs (OHA)2 demonstrated that a considerable number of agent-hours (approximately 90,000 agent-hours/year for just the four busiest southwest border stations) are lost because of the need to escort detainees to the emergency room (Zapata, 2013). A comprehensive operational medicine program addressing the health and medical needs of detainees in addition to those of DHS employees could have significant mission impacts.

Improved interoperability is another mission-related impact that could be achieved through a more integrated health system, particularly as it relates to operational medicine functions (Recommendation 8). Components often have different mission spaces, but for the specific conditions under which they must coordinate and collaborate, interoperability can be critical (Hill, 2013). Examples include disaster scenarios and custody transfer of detainees between agencies. DHS has already made progress in this area with harmonized treatment protocols and interoperable patient record systems, but additional mechanisms promoting interoperability will likely emerge as Component Lead Medical Officers (Recommendation 4) develop a stronger understanding of common challenges through the Medical and Readiness Committee (Recommendation 5).

Cost Savings

During its examination of health protection programs at DHS and other public and private organizations, the committee learned of many ways (e.g., injury prevention, disability management, health risk reduction) in which employers are achieving cost savings through employee health protection and promotion initiatives. Although pioneering companies such as Johnson & Johnson have had integrated employee health programs in place for more than a decade (Isaac, 2013), more widespread adoption of integrated

__________________

1Refers only to medical needs of detainees prior to transfer to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detainment facilities.

2As described in more detail in Chapter 7, the proposed Southwest Border Initiative would place medical providers at four of the busiest Border Patrol stations along the southwest border to provide screening and medical treatment services to detainees, and if needed, DHS employees.

approaches has really just begun. Consequently, although data on cost savings and return on investment may be available for individual interventions (e.g., worksite wellness programs), the committee found few evaluations of the cost impacts of implementing integrated workforce health protection programs. Navistar, Inc., a commercial manufacturing company, has measured cost savings associated with the efforts of its integrated Health, Safety, Security and Productivity unit. While average national health care expenditures have been increasing, Navistar has experienced net decreases in health care costs over the past decade, with similar trends in workers’ compensation and disability costs (a 38 percent reduction from 2002 to 2008) (Bunn et al., 2010). At Johnson & Johnson, the implementation of its integrated Health & Wellness Program3 resulted in savings of approximately $224.66 per employee per year as a result of reduced medical claims costs (outpatient, inpatient, and mental health visits) over the 4-year program period, with the most pronounced cost savings being realized in program years 3 and 4 (Ozminkowski et al., 2002).

Savings data such as those reported by Johnson & Johnson cannot simply be projected onto DHS, but even more modest per capita cost savings certainly could have dramatic impacts for a workforce of more than 200,000 employees. However, a major challenge for DHS and other government agencies is the centralized management of federal employee health benefits through the U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Lack of access to health care utilization and cost data impedes not only the identification of needed interventions and their targeting to an organization’s major health risks, but also the use of reductions in health care costs (outside of those associated with workers’ compensation) as benchmarks or as financial incentives for individual agencies to invest in employee health. As a result, measurable cost savings to DHS are limited primarily to workers’ compensation costs, which can be very slow to respond to interventions, although continuation-of-pay costs4 are more responsive to improvements in injury prevention and disability management practices. To address this issue, occupational health program staff at the Smithsonian linked sick day utilization to productivity and institutional savings. By comparing projected and actual sick day utilization rates, the organization was able to demonstrate savings associated with its occupational health program in terms of

__________________

3Johnson & Johnson’s “shared services concept” for its Health and Wellness Program entailed integrating employee health promotion, disability management, employee assistance, and occupational medicine programs. Safety and industrial hygiene programs were managed separately (Ozminkowski et al., 2002).

4Continuation-of-pay costs represent the wage replacement costs paid by the employing agency for the first 45 days that a federal employee is out on workers’ compensation (see Chapter 3).

manpower (106 full-time employees) and cost ($9.54 million) over a 3-year period (Duval, 2013).

The intensive efforts undertaken at the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) to reduce occupational injuries and return injured employees to work in a timely manner5 provide an example of the magnitude of savings that can be achieved just in workers’ compensation costs through investment in workforce health protection initiatives. Between 2005 and 2012, TSA reduced workers’ compensation claims by 78 percent, achieving an 81 percent reduction in continuation-of-pay costs and a 19 percent reduction in chargeback costs. In 2012, TSA’s combined annual continuation-of-pay and chargeback costs were approximately $18 million less than in 2005 when efforts began (Mitchell, 2013). Although the committee was not provided with the total continuation-of-pay costs for DHS, its chargeback costs in 2010 exceeded $160 million6 (see Table 1-2 in Chapter 1 for a breakdown of these costs by component agency). An integrated approach to injury/illness prevention, workers’ compensation cost containment, and disability management7 that produced even a modest percentage decrease in chargeback costs at DHS could result in savings of millions of dollars. These data are consistent with reports in the literature showing reductions in workers’ compensation costs associated with integrated approaches to occupational injury prevention and case management (Bernacki and Tsai, 2003). At the Johns Hopkins Institution (including the hospital and university), an integrated workers’ compensation claims management system that promoted a collaborative approach involving safety professionals, adjusters, and medical and nursing professionals resulted in a 73 percent reduction in lost time claims over a 10-year period. Total workers’ compensation costs per $100 of payroll decreased by 54 percent over that same period (Bernacki and Tsai, 2003).

Another important opportunity for DHS to achieve cost savings that was described to the committee is a proposed initiative aimed at reducing costs associated with emergency room visits. As described above, DHS currently lacks the medical assets required to address the health needs of detainees along the southwest border. In addition to lost productivity associated with escorting detainees to the nearest hospital for health screening and even minor treatment needs, the emergency room costs themselves are significant—approximately $13 million in fiscal year 2011 (Zapata, 2013). To reduce these direct and indirect costs, the committee supports expansion

__________________

5These efforts are described in detail in Chapter 4.

6E-mail communication, G. Myers, DHS Workers’ Compensation Program Manager and Policy Advisor, to A. Downey, Institute of Medicine, regarding department statistics: chargeback totals and actuarial liability, February 20, 2013.

7As described in Chapter 4, both TSA and FAMS have developed this kind of integrated approach, although the two approaches differ in terms of in- versus outsourcing.

of the DHS operational medicine capability (Recommendation 8) as described for the Southwest Border Initiative.

The specific examples provided above demonstrate the potential for achieving future cost savings at DHS, but lasting cost containment can be realized only by continuously striving toward improvements in efficiency and effectiveness. To this end, it will be necessary to refocus efforts periodically on mission-critical work, ensure accountability, and partner with financial leadership to ensure that plans and policies are supported by business cases. Centralization of services (Recommendation 9) could facilitate savings through efficiencies related to economies of scale (e.g., bulk purchasing of common medical supplies) and consolidation of contracted services where appropriate.

Liability

Beyond liability in terms of health-related costs, the committee identified several other liability risks associated with failure to ensure that core competencies are met for safety, health, and medical programs. Equal employment opportunity suits may be brought against the department when individuals believe they have been inappropriately denied employment based on a medical condition.8 Ensuring consistency in health-related employment standards for job series that are shared across DHS (Recommendation 7) could improve the legal defensibility of such standards, resulting in dismissal of complaints and associated cost avoidance. Further, DHS is legally responsible for providing medical treatment to individuals in its custody (Mulry et al., 2008). An operational medicine capability (Recommendation 8) that ensures that in-custody individuals receive timely and appropriate medical care could help avoid lawsuits brought by detainees and their families, as well as citations from the DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties. Finally, under 6 USC 320, “each Federal Agency with responsibilities under the National Response Plan shall ensure that incident management personnel, emergency response providers, and other personnel (including temporary personnel) and resources likely needed to respond to a natural disaster, act of terrorism, or other manmade disaster are credentialed and typed.” Additionally, many courts have held health care organizations liable for negligent credentialing of medical providers in their employ (Darling v. Charleston Hospital, 1965; Columbia/JFK Medical Center v. Sanguonchitte, 2006; Frigo v. Silver Cross Hospital and Medical Center, 2007; Larson v. Wasemiller, 2007; Archuleta v. St. Mark’s Hospital,

__________________

8Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

2010; Moreno v. Quintana, 2010).9 In addition to reducing the potential for liability arising from the actions of inappropriately credentialed providers, centralized credentialing (Recommendations 2 and 8) would, as part of the medical oversight functions of OHA, help ensure that medical providers employed or contracted by DHS component agencies are held to common standards for education, certification, and currency.

Other Benefits

Since its inception, DHS has been working to address concerns regarding low morale, job satisfaction, and employee engagement through a range of management strategies (GAO, 2012). Employee morale is measured through the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey, which also showed that DHS is 14 percentage points behind the government-wide average in the proportion of respondents indicating that they feel protected from health and safety hazards on the job (OPM, 2012). Given that the root causes of employee morale issues at DHS likely are complex and cannot be attributed to any one problem, implementation of a departmental strategy that communicates a clear and visible emphasis on the importance of employee health and safety is one means by which DHS could demonstrate concern for its workforce. Although supporting data are limited and often anecdotal, links between the effectiveness of occupational health programs and employee morale have been reported (Behm, 2009; OSHA, 2002).

In addition to the aforementioned benefits, an important but often forgotten impact of strengthening the DHS health protection infrastructure as recommended by the committee is the potential for improvements in employee health. People spend a large proportion of their lives in the workplace; consequently, employee health initiatives can have major impacts on employees’ own well-being. Aside from the benefits to the department as a whole, all DHS employees deserve a working environment that is supportive of their health and safety.

PRIORITIES FOR IMPLEMENTING AN INTEGRATED HEALTH PROTECTION INFRASTRUCTURE

The committee was asked to prioritize recommendations for long- and short-term measures DHS can adopt to optimize its mission readiness by ensuring the health, safety, and resilience of its workforce. The committee

__________________

9The case law the committee reviewed relates to negligent credentialing by hospitals. However, the committee believes that because DHS employs medical staff who provide services to both employees and people in custody, failure to ensure proper credentialing could increase the potential for liability claims in this area as well.

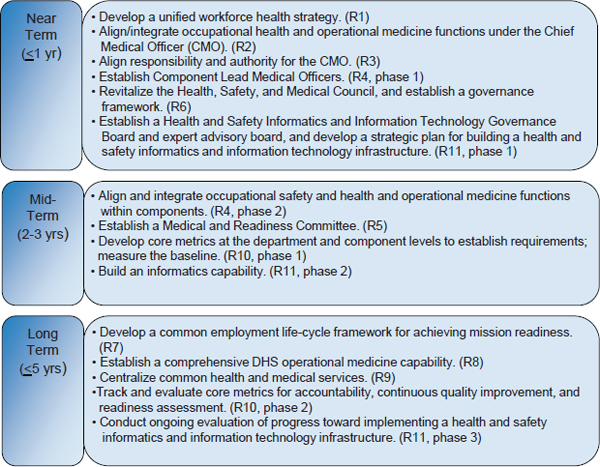

believes that each of the recommendations offered in this report is critical to the development of an integrated health protection infrastructure and that planning for implementation of all the recommendations should be incorporated into the next DHS planning, programming, budget, and execution cycle (see Figure 5-1 in Chapter 5). At the same time, the committee also recognizes that some steps must be initiated, and in some cases completed, before others. The committee was not asked to provide a timeline or implementation plan and does not have the insight to do so; implementation of its recommendations may be protracted because of necessary lead time, resource limitations, and the complexity of managing enterprise-wide change. Nonetheless, Figure 9-1 shows the committee’s recommendations in the

FIGURE 9-1 Suggested timeline for implementation of the committee’s recommendations.

NOTES: Recommendations (R1-R11) are grouped according to priority for completion, recognizing that many of the mid- and long-term recommendations will need to be initiated in the near term but completed in the mid-/long term. Time frame estimates associated with the near-, mid-, and long-term categories should be interpreted as time from entry into the DHS planning, programming, budget, and execution cycle.

context of the near, mid-, and far terms. The implementation of some recommendations—for example, establishing a health and safety informatics and information technology infrastructure—may span multiple years and will need to be undertaken in phases, whereas others can be completed within more discrete time periods.

Integration of the DHS health protection system will require, fundamentally, a significant culture change and a willingness to function and act like a single agency with a common mission focus. The committee believes that the first priority is therefore to gain the commitment of core leadership at the component and headquarters (i.e., Chief Medical Officer, Chief Human Capital Officer, Chief Financial Officer) levels to a standard change management and governance process, clarifying the importance of workforce health to mission success and each party’s accountability for employee health and safety. Absent such unity of vision, the committee’s other recommendations are unlikely to be embraced.

The committee noted the specific mention of workplace wellness programs as a priority in the DHS Strategic Plan. Although the committee includes promotion of individual readiness as part of its life-cycle approach to workforce health and readiness (Recommendation 7), it is concerned about an undue emphasis on wellness while the DHS workforce faces significant challenges related to health protection (i.e., injury and illness prevention). Moreover, the committee does not believe that meaningful, data-driven health promotion efforts are currently possible across much of DHS, given the lack of data and analysis tools to support a clear understanding of the major health risks facing the department’s employees. Accordingly, the committee suggests that the implementation of health promotion programs be considered a long-term goal at DHS.

The DHS mission to protect the homeland is of critical importance, but the ability to achieve that mission is undermined by a workforce health protection infrastructure that is marginalized, fragmented, and uneven. The fragmented DHS health protection system is just one instance of an overarching management problem that the organization has worked diligently to overcome since its inception. DHS is not the first federal agency to struggle with these considerable challenges; the Department of Defense (DoD) has worked for almost 70 years to overcome the culture and communication barriers to joint operations. Despite considerable progress, this is an ongoing process at DoD, and the same will be true for DHS for some time into the future. Through its recommendations (summarized in Box 9-2), the committee has attempted to provide a foundation and a path forward for an integrated health protection infrastructure encompassing the

programs, tools, and resources needed to enable the DHS workforce to fulfill the homeland security mission. In essence, the goal is to do on a smaller scale what the Homeland Security Act sought to accomplish more than 10 years ago—to weave the key functions and activities entailed in protecting the homeland into a unified, cohesive enterprise. To this end, the mission-ready DHS of the future will require an empowered and resourced Chief Medical Officer who, through partnership with the component agencies,

BOX 9-2

Summary of Key Findings, Conclusions,

and Recommendations for Integrating

Workforce Health Protection at DHS

Chapter 5: Leadership Commitment to Workforce Health

Recommendation 1: Demonstrate leadership commitment to employee health, safety, and resilience through a unified workforce health protection strategy.

Key Findings:

- Vocal and active commitment from leaders at all levels has been integral to creating successful workforce health protection programs and developing a culture of health in the organizations examined by the committee. Such programs have been found to lead to increases in employee morale, efficiency, and effectiveness.

- DHS has the highest rate of occupational injury and illness of all cabinet-level federal agencies, and more than one-third of DHS employees responding to the 2012 Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey say they do not feel protected from health and safety hazards on the job.

- The DHS Strategic Plan lacks a strategic objective to reduce injuries and illnesses.

- The DHS Workforce Strategy, issued to improve and integrate employee recruitment, development, and retention efforts, does not address the promotion and protection of employee health, safety, or resilience as a critical means of sustaining an engaged workforce.

- Despite strategic aspirations to improve employee health, safety, and resilience, the committee found no evidence of a defined strategic plan for achieving those outcomes or of processes put in place to hold department leadership accountable for doing so.

- The committee saw little evidence that the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) is held accountable for achieving the strategic objectives intended to support the Secretary’s goal of improving employee health, wellness, and resilience.

institutes policies and global standards that permeate the entire organization to ensure the health, safety, and resilience of its workforce. Finally, if DHS is to meet the needs of its diverse workforce in the face of continuously evolving challenges, it will require a health protection infrastructure that remains agile. Adoption of a learning health system approach will allow DHS to transform information into knowledge, which in turn can be used to drive health system change based on evidence-based best practices.

Conclusions:

- DHS lacks a unified vision and comprehensive strategy for ensuring the delivery of key health, safety, and medical support services department-wide in a consistent and coordinated manner.

- A formal strategy, guided by a vision statement directly linked to the organizational mission, could provide direction while also demonstrating the commitment of top leadership to employee health, safety, and resilience.

- To ensure accountability at all levels, program-level goals and performance measures should cascade down from those at the strategic level and should be tailored to the individual’s level of responsibility.

Chapter 6: Organizational Alignment and Coordination

Recommendation 2: Align and integrate all occupational health and operational medicine functions under the Chief Medical Officer.

Key Findings:

- DHS continues to face challenges related to horizontal and vertical integration of key management functions. Workforce health protection has not been included in larger management system integration efforts at DHS.

- Current workforce health protection and promotion activities at the DHS headquarters level are divided between two mission support offices: the Office of Health Affairs (OHA) and the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer, the latter being located within the Management Directorate.

- The CMO lacks visibility and strategic input with respect to the workforce health protection functions currently administered at the headquarters level through the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer; the result is a lack of role clarity for the CMO.

- The DHS Safety, Health, and Medical Council, co-chaired by the CMO and Designated Agency Safety and Health Official (DASHO) (currently the Chief Human Capital Officer) was established in 2008 to facilitate the coordinated formulation of department-wide health, safety, and medical program policy and the development of integrated tools and standardized processes to support program functions. However, the Council has been inactive for more than a year.

- Interactions between OHA and the occupational safety and health personnel occur on an ad hoc basis, resulting in missed opportunities and redundancies.

- In several organizations external to DHS, medical programs are organizationally segregated from occupational safety and health programs. This approach can be effective when the two operations are strategically aligned and appropriate mechanisms are in place and functioning to ensure effective coordination, including oversight of both units by a single governing entity. Such alignment has not occurred at DHS.

- Although a memorandum of understanding was put in place in September 2009 to delineate the responsibilities of OHA and the DASHO’s office, the matrix designating lead and shared responsibilities for each program was found to be inaccurate (with regard to actual current responsibilities) and out-of-date. A revision process was initiated, but was interrupted by management turnover within OHA.

Conclusions:

- The fragmentation of workforce health protection functions and the lack of sufficient delegation of authority to the CMO have resulted in ambiguity and uncertainty regarding roles and responsibilities.

- The absence of formal mechanisms for coordination and communication has resulted in stovepiped workforce health protection functions, contributing to inefficiency, a lack of accountability and transparency, and missed opportunities to achieve synergy through integration.

- DHS needs to align its resources with its strategic objectives, develop performance metrics, and hold its health and line leadership accountable for occupational health and operational medicine outcomes.

Recommendation 3: Ensure that the Chief Medical Officer has authority commensurate with the position’s responsibilities.

Key Findings:

- Authority has been delegated to the CMO to exercise oversight over all DHS medical and public health activities; however, this delegation has not been reviewed or revised since its enactment in 2008.

- Despite being delegated the authority to exercise oversight over all medical and public health activities for DHS, in practice the CMO lacks this authority.

- OHA provides the components with guidance and tools but lacks the authority to ensure implementation.

Conclusions:

- Ambiguity in the CMO’s authority to exercise oversight has contributed to a lack of role clarity and impedes the CMO’s ability to align critical health protection functions across DHS for integrated execution.

- The establishment of a single health, safety, and medical entity would support two of the Secretary’s departmental objectives: (1) unifying and integrating management functions to better serve DHS missions, goals, and employees; and (2) improving employee safety, wellness, and resilience.

- Establishing such an entity also would enable more efficient management of resources; enhanced communication with leadership, components, and all DHS employees; more consistent performance measurement; improved accountability and transparency; and ultimately, increased organizational effectiveness and synergy.

Recommendation 4: Establish Component Lead Medical Officers to align and integrate occupational health and operational medicine functions.

Key Findings:

- The current workforce health protection infrastructure at DHS is highly fragmented and markedly uneven across the component agencies.

- DHS and its component agencies have struggled to retrofit a large set of distinct legacy and nascent organizational structures into a single cohesive operational and management framework that meets the diverse requirements of the DHS mission. The same is true of the organizational structures supporting health protection; component agency infrastructures for carrying out health, safety, and medical functions vary widely.

- Placement of occupational health programs supporting essential functions is fragmented in some agencies and centralized in others, and the organizational location of health-related programs differs across the components.

- In DHS components with aligned or partially aligned organizational structures in which health, safety, and/or medical programs and functions are collocated, the committee found evidence of increased information sharing through regular meetings and coordination processes, encouraging communication and synergy in support of mission requirements.

- Vertical integration of medical programs has been challenging because of the lack of formal mechanisms for this purpose. The Medical Liaison Officer (MLO) program has begun to address this issue by creating more formalized channels of communication and mechanisms for vertical information sharing. However, challenges in this area remain, as only four of the operating components currently have Senior Medical Advisors, and fragmentation still exists within the components, often separating Senior Medical Advisors from some of the essential functions identified by the committee.

- In some instances, medical functions have been outsourced with no oversight from internal medical authorities.

Conclusions:

- Oversight from the headquarters level is more challenging when there is no single responsible leader or even consistency in what are considered medical, occupational safety and health, and human resources functions.

- The current fragmented organizational structure and the distribution of health, safety, and medical authorities within DHS component agencies will impede the ability of the CMO to orchestrate a comprehensive and integrated workforce health protection strategy to ensure the health, safety, and resilience of the entire DHS workforce.

- The effectiveness of the CMO would be enhanced by having a single point of accountability within the operating components who could ensure the integration of component occupational health and operational medicine functions.

Recommendation 5: Establish a Medical and Readiness Committee to promote information sharing and integration.

Key Findings:

- Prior to establishment of the MLO program, the CMO had limited visibility on health and medical programs and challenges within component agencies. This limited visibility impeded the CMO’s ability to address cross-cutting and department-wide health and medical issues through policy and program initiatives and to ensure that the Secretary’s agenda is assimilated at the component level.

- The role for Senior Medical Advisors in building and sustaining an integrated health protection system has yet to be clearly defined and formalized.

- Directives and proposed standards from OHA have sometimes been disconnected from the needs and realities within the component agencies, potentially contributing to uneven compliance with OHA policy.

Conclusions:

- A mechanism is needed to enable the CMO to collect information on operational requirements from the component level, to engage components in the development of medical and public health policy, and to provide senior-level direction for an integrated DHS workforce health protection strategy.

- Networking among component medical officers is critical and would best be realized through regular and formal direct interaction with the CMO.

Recommendation 6: Create a governance framework to engage Department of Homeland Security management officials and component leadership in employee health, safety, and resilience to support mission readiness.

Key Findings:

- The Government Accountability Office designated DHS’s formation as high risk, in part because of the foreseen management challenges associ-

-

ated with merging 22 component agencies and the serious consequences of failing to achieve integration. In working to address these concerns, DHS has established a tiered governance structure to facilitate integration and oversight of interrelated programmatic activities that support mission outcomes across the department. The committee is unclear as to whether or how workforce health protection programs would be managed within the existing DHS governance structure.

- Multiple headquarters offices and component agencies have shared responsibilities for the complex programs supporting the health, safety, and mission readiness of the DHS workforce.

- The DHS Health, Safety, and Medical Council was established as a governance body to facilitate the necessary ongoing coordination, collaboration, and participation of these various headquarters- and component-level stakeholders in the development of health, safety, and medical policy. However, the Council has been inactive for more than a year.

- When the CMO position was created at DHS, the vision was to appoint a medical leader who could unify the department’s fragmented health and medical system. The Delegation to the Assistant Secretary for Health Affairs and Chief Medical Officer granted the CMO the oversight authority needed to achieve that vision. In the absence of accountability processes, however, the CMO has to date been largely unsuccessful in garnering sufficient support from component leadership to achieve a unified health system.

Conclusions:

- Portfolio-level governance of workforce health protection programs would help ensure alignment and efficiency.

- Many workforce health protection functions span the intersection between health and human resources and therefore also require the involvement of the Chief Human Capital Officer. Input from other members of the DHS management team may be required as well to ensure adequate resourcing of occupational health and operational medicine programs and effective management of these programs within the larger DHS financial, acquisitions, and information management architecture.

- Reinvigoration of the inactive Health, Safety, and Medical Council is critical to achieve DHS-wide consensus on strategies for addressing overarching and cross-cutting health, safety, and medical issues and to engage component leadership in the development of policies that support the readiness of their workforces. To function effectively, the Council will need to be part of a larger formalized governance structure.

Chapter 7: Functional Alignment

Recommendation 7: Develop a common employment life-cycle-based framework for achieving mission readiness.

Key Findings:

- Mechanisms for assessing, promoting, and sustaining medical readiness vary widely across DHS.

- Few standards and overarching policies related to medical readiness have been promulgated by the CMO, creating risk of liability associated with equal employment opportunity suits (if medical standards are not adequately defensible in a court of law) and inadequate processes for preventing or limiting disability.

Conclusions:

- A comprehensive strategy for supporting readiness needs to address the full employment life cycle, focusing not only on the health and capability of employees but also on the safety of both job processes and the work environment and the interactions among these three elements.

- A common life-cycle framework for approaching workforce health and resilience would provide a mechanism for ensuring that a set of disparate components can achieve the appropriate mission readiness outcomes.

Recommendation 8: Establish a comprehensive operational medicine capability to ensure consistent, high-quality medical support during operations.

Key Findings:

- Working collaboratively with nine DHS component agencies through the Emergency Medical Services Training and Education Advisory Committee, OHA has developed a centralized emergency medical services (EMS) system plan, established standards of care through baseline basic life support and advanced life support protocols, and acquired software for DHS-wide patient care reporting and tracking of EMS provider credentials.

- The requirement for DHS law enforcement officers to escort detainees to a distant emergency department for even minor injuries and illnesses is costly in terms of both treatment for detainees and the impact on operations of the temporary unavailability of those officers. In 2011, emergency department visits for detainees in the custody of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) in southwest border region alone cost DHS $13 million.

Conclusions:

- OHA has achieved commendable progress toward the integration of EMS across DHS.

- A comprehensive program for operational medical support needs to go beyond EMS to include the capability to address the preventive and ambulatory medical care needs of those conducting DHS operations.

- DHS has a responsibility to ensure that members of its workforce operating in remote, austere areas and those who, for security reasons, cannot readily access local medical resources have access to comprehensive medical services. Beyond moral and legal responsibilities, the lack of access to basic preventive and responsive medical services to mitigate

-

serious medical events (e.g., infectious disease outbreaks and injuries) in field situations can result in preventable illness or injury, lost productivity, and logistical challenges that lead to mission failure.

- The medical and operational needs related to those in DHS care or custody need to be addressed by a comprehensive DHS operational medicine program.

- The diversity of operational and mission requirements among DHS’s component agencies prohibits a one-size-fits-all approach to the establishment of a departmental operational medicine capability. Components and subcomponents need flexibility to develop operational medicine programs that meet the requirements of their unique operating conditions.

Recommendation 9: Centralize common services to ensure quality and to achieve efficiencies and interoperability.

Key Findings:

- OHA has a key role in supporting components’ collective efforts to carry out the DHS mission and in so doing, in contributing to the “one DHS” concept.

- DHS has been criticized for making acquisition decisions on a program-by-program and component-by-component basis. For example, occupational health and medical services are procured at the component and sometimes the local site level, resulting in hundreds of independent contracts and interagency agreements, with little in the way of technical oversight to ensure service quality.

- DHS relies heavily on outsourced providers for occupational health and medical services (e.g., fitness-for-duty evaluations, health promotion services, ergonomics assessments, medical surveillance services).

Conclusions:

- Because of the wide variation among their missions, each of the major operating components has specific needs that are best served by support programs tailored to its operational functions. However, some common services should be centralized to promote efficiency and interoperability while ensuring the necessary level of service quality.

- Centralizing common critical services enables alignment of component mission needs with department-level goals. A more formalized approach for obtaining buy-in from components should be used to accelerate the process of establishing centralized health, safety, and medical services.

- A mechanism is needed to ensure that contracts and agreements are consistent with the overarching health policies and standards of the department.

Chapter 8: Information Management and Integration

Recommendation 10: Collect core metrics for accountability, continuous quality improvement, and readiness assessment.

Key Findings:

- Stovepiped programs and a lack of communication and coordination mechanisms across DHS have resulted in failures of knowledge management.

- DHS lacks a strategy, framework, and common set of metrics for use in conducting a comprehensive evaluation of workforce readiness and resilience, and for evaluating and improving the effectiveness of programs that support a ready and resilient workforce.

- Components routinely gather safety and employee health data, albeit in an uneven and inconsistent manner; however, little of this information is transmitted to OHA. The only source of data currently received by OHA of which the committee is aware is the centralized electronic patient care record.

- Injury and illness data (Total Case Rate and Lost Time Case Rate), while reported at least annually to the DHS occupational safety and health program staff in the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer as required by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), are not shared routinely with OHA.

- Attempts to collect medical quality assurance data (e.g., reports of sentinel events, frequency of clinical competency assessments), as authorized by Directive 248-01 on medical quality management (MQM), have been unsuccessful. Components have begun collecting some of the required data, but are not using dashboards provided by the MQM staff to share these data with OHA.

- Minimal data appear to be collected on employee health risks, even at the component level, with the notable exception of the Coast Guard, which mandates a health risk appraisal for all active-duty members.

Conclusions:

- Obtaining reliable and consistent information is essential to the implementation and sustainment of an integrated workforce health protection program. This can be achieved through a focus on information management—a systematic approach involving both technological and informatics capabilities that supports information exchange.

- Within a large, decentralized organization such as DHS, a centralized system for information management with standardized metrics and measures will support both horizontal (across levels) and vertical (between levels) integration.

- A systems approach is needed to collect and integrate data from across the department. This type of approach, which entails data collection and analysis at four nested levels (individual, group, component, and department), supports both horizontal and vertical integration.

- In the absence of a comprehensive, standardized system with which to measure the performance of DHS’s occupational safety and health, occupational medicine, operational medicine, health promotion, and workers’ compensation programs, it is not possible to determine whether each

component agency is managing its safety risk in an acceptable manner and whether occupational health programs are meeting objectives for improving workforce health and readiness. Thus, there is no means of ensuring accountability, and those with responsibilities for workforce health, safety, and readiness are unable to make evidence-based decisions on investments in programs and infrastructure or to assess and improve the quality of programs and services.

Recommendation 11: Establish a health and safety informatics and information technology infrastructure.

Key Findings:

- Over the past two decades, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has transformed the quality and safety of patient care at its numerous clinics and hospitals through the implementation of its electronic health record (EHR) system, VISTA. VA’s investment in health information technology (HIT) saved more than $3 billion in health care costs between 1997 and 2007.

- OHA has initiated an acquisition process for a DHS-wide electronic Health Information System (eHIS). The committee had difficulty obtaining information on DHS’s strategic approach to health information management using the proposed system. Funding for the system has yet to be approved. OHA is currently assessing feasibility and capabilities and has contracted for an evaluation of existing systems to determine the cost-effectiveness of agency-wide implementation.

- A working group comprising representatives from OHA, the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer, and other DHS components identified the following five mission and capability needs for the eHIS: (1) ensure that staff are medically suitable for their assigned or volunteered duties (e.g., job and environment); (2) provide for the execution of an efficient DHS-wide fitness-for-duty and limited-duty program; (3) enable efficient dispensing, tracking, and follow-up for medical countermeasures; (4) lower occupational health costs across the department; and (5) unify and standardize occupational health and workforce health protection activities across the department.

- OHA has already acquired an electronic patient care record (ePCR) system, allowing DHS to consolidate all patient records. All DHS components with EMS personnel have been given access to the system, and it already has been adopted by a number of operational medicine units. By spring 2014, all DHS components are expected to have adopted the system. However, it is unclear what role the ePCR investment plays in a comprehensive HIT/informatics strategy or how patient record information (for DHS employees) will be integrated with the eHIS should that system be implemented in the future.

- The Coast Guard, working with the VA and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, is building an integrated health information system (IHiS) based on the commercial Epic EHR sys-

-

tem for traditional clinical care environments. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) also recently awarded a contract for such a system to support comprehensive medical services management for detainees.

- Information technology systems for occupational safety and health vary considerably across DHS, and there is no DHS-wide system that allows safety and workers’ compensation data to be aggregated at the headquarters level. Tracking of this information varies among components, from the use of spreadsheets to sophisticated safety information systems (such as that used by the Transportation Security Administration [TSA]).

- Although DHS is moving toward an enterprise approach to HIT, the committee found no evidence that the department is fully aware of the informatics capability required to maximize the potential of an integrated health information management system. Two OHA staff members are trained in nursing informatics, and a third is familiar with the use of clinical informatics systems for medical quality assurance processes. However, this informatics capability does not appear to be represented at the component level, with the exception of the Coast Guard, which has a Chief Medical Information Officer.

- Headquarters MQM staff have been working with components to establish systems and processes that will enable structured/standardized data collection, reporting, and analysis for purposes of continuous quality improvement. Yet components, which rely primarily on outsourced medical service providers, appear not to have the personnel or expertise necessary to adopt such practices and, as noted above, have yet to use the dashboards provided by MQM staff for these purposes.

Conclusions:

- In support of operational medicine services, a system is required to document treatment provided to anyone receiving care from DHS providers.

- A longitudinal health record to support occupational health, including readiness assessment, is required to document health issues that are relevant to employment, addressing primarily capabilities specific to job duties and deployments.

- The lack of health informatics expertise across DHS may help explain the lack of success of the MQM program.

- Across DHS, health information and communication technology is viewed primarily as a strictly tactical resource. This perspective is too narrow to meet the current and future mission requirements of the various DHS components.

- Components are engaged with clinical care, preventive medicine, and occupational medicine to varying degrees, but the development of health information management applications, data repositories, and communications capabilities is spotty at best. Integration through health information management will not be achieved until this capability exists throughout the department.

Behm, M. 2009. Employee morale: Examining the link to occupational safety and health. Professional Safety 54(10).

Bernacki, E., and S. Tsai. 2003. Ten years’ experience using an integrated workers’ compensation management system to control workers’ compensation costs. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 45(5):508-516.

Bunn, W. B., H. Allen, G. M. Stave, and A. B. Naim. 2010. How to align evidence-based benefit design with the employer bottom-line: A case study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 52(10):956-963.

Duval, J. 2013. Smithsonian Institution occupational health services. Presentation at IOM Committee on DHS Occupational Health and Operational Medicine Infrastructure: Meeting 2, June 10-11, Washington, DC.

FAMS (Federal Air Marshal Service). 2013. Cost efficiencies nurse case management: OWCP collaboration. Washington, DC: FAMS.

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2012. Department of Homeland Security: Taking further action to better determine causes of morale problems would assist in targeting action plans. GAO-12-940. Washington, DC: GAO.

Hill, A. 2013. Keynote address. Presentation at IOM Committee on DHS Occupational Health and Operational Medicine Infrastructure: Meeting 2, June 10-11, Washington, DC.

Isaac, F. 2013. Work, health, and productivity: The Johnson & Johnson story. Presentation to IOM Committee on DHS Occupational Health and Operational Medicine Infrastructure: Meeting 2, June 10-11, Washington, DC.

Mitchell, M. 2013. Workers’ compensation programs at DHS: TSA. Presentation at IOM Committee on DHS Occupational Health and Operational Medicine Infrastructure: Meeting 2, June 10-11, Washington, DC.

Mulry, R. F., A. M. Silverstein, and W. Fabbri. 2008. Medical care of in-custody individuals. In Tactical emergency medicine, edited by R. B. Schwartz, J. G. McManus, and R. E. Swienton. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Pp. 123-129.

OPM (U.S. Office of Personnel Management). 2012. 2012 Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey results: Department of Homeland Security agency management report. Washington, DC: OPM.

OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration). 2002. Add value. To your business. To your workplace. To your life. Job Safety & Health Quarterly 14(1).

Ozminkowski, R. J., D. Ling, R. Z. Goetzel, J. A. Bruno, K. R. Rutter, F. Isaac, and S. Wang. 2002. Long-term impact of Johnson & Johnson’s health & wellness program on health care utilization and expenditures. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 44(1):21-29.

Zapata, I. 2013. FY2015-FY2019 Southwest Border Health Initiative business case. Presentation at IOM Committee on DHS Occupational Health and Operational Medicine Infrastructure: Meeting 2, June 10-11, Washington, DC.