Global Harmonization of Methodological Approaches to Nutrient Intake Recommendations: Proceedings of a Workshop (2018)

Chapter: 2 Background for the Workshop

2

Background for the Workshop

OVERVIEW

The opening session was moderated by workshop planning committee chair Stephanie Atkinson and provided background information for the workshop. Janet King provided an overview of concepts put together by the 2005 international harmonization initiative. That initiative encompassed not only the actual meeting in Florence, Italy, in 2005, but also publication of 10 commissioned background review papers in Food and Nutrition Bulletin in 2007 (King and Garza, 2007). The Florence group developed a new term, nutrient intake value (NIV), but emphasized that NIV is analogous to other terms used around the world (e.g., Dietary Reference Intake [DRI], dietary reference value [DRV]). The Florence group then developed separate frameworks (i.e., factors and criteria to consider) for estimating two NIVs in particular: average nutrient requirement (ANR), also known as estimated average requirement (EAR), and upper nutrient level (UNL), more commonly known as tolerable upper intake level (UL). King described several other issues addressed by the group as well, such as criteria for indicators to use when developing NIVs.

Suzanne Murphy continued where King left off, that is, how an NIV, once established using a globally harmonized methodology, can be used or applied at a country or region level. She reviewed in detail the many critical health applications that depend on accurate nutrient intake recommendations, one of which, the setting of global nutrient standards, was, she said, “the reason we are here today.” She added that, while many of the other applications are country specific (e.g., designing food assistance programs), an

often overlooked advantage of harmonization is an increased understanding of these other applications.

This chapter summarizes in detail these two presentations, with an overview of points in Box 2-1.

HARMONIZING THE NUTRIENT INTAKE VALUES: PHASE 11

What Janet King referred to as “phase 1” of harmonizing the process for developing nutrient intake values began in 2005 at a meeting in Florence where 17 scientists convened to review harmonizing approaches for developing nutrient-based dietary intake standards. Phase 1 extended through 2007, when 10 commissioned background review papers were published in the Food and Nutrition Bulletin (King and Garza, 2007). King recognized the several individuals, in addition to herself, who were present at this Rome workshop and who were also part of the Florence meeting (i.e., Lindsay Allen, Stephanie Atkinson, Rosalind Gibson, Suzanne Murphy, and Patrick Stover). She then went on to review the concepts that were put together at the Florence meeting and described in detail in the commissioned papers.

Why Harmonize the Process for Developing NIVs?

The 2005 Florence group identified four strategic reasons for harmonization:

___________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Janet King, Ph.D., senior scientist, Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, California.

- improve objectivity and transparency of values developed by different groups;

- provide a common basis for various NIVs;

- allow low-income countries, with limited resources, to convene groups for modifying the standards for their specific food supplies or national policies; and

- provide a common basis across countries and regions for establishing global nutrition policies (i.e., fortification policies, regulatory issues).

King commented that, while these four reasons may seem obvious now, in fact it took the Florence attendees quite a while to pull them together.

Terms to Harmonize

The discussion around which terms to harmonize was very long as well, King recalled. First, they had to decide what they were going to call the values. They finally agreed on nutrient intake values, or NIVs, as the term to use when referring to nutrient intake recommendations. They emphasized, however, that NIV is analogous to values already in use in different regions around the world, such as DRI, DRV, and nutrient reference value (NRV).

The “next big debate,” King continued, was which aspects of the NIVs to develop. The Florence group decided to develop only two: (1) ANR, which King noted some people call the EAR, and (2) UNL, also known as the UL. The ANR is the midpoint of the range of requirements that exist in a population. Other nutrient values, like the lower reference nutrient intake (LRNI) and recommended dietary allowance (RDA), can be derived from the ANR.

The group agreed, however, that it may not always be possible to develop an ANR and a UNL for all nutrients. In cases where data are not sufficient to develop specific recommendations, it may be necessary to establish a safe or adequate intake (AI) instead.

Framework for Estimating ANRs

The Florence group developed the following framework for establishing ANRs, King described:

- The ANR should be based on the mean intake of a population for a specific nutrient. If those values are not distributed normally, then the data should be normalized and the median value used instead.

- ANRs should be established for all essential nutrients and food components that have public health relevance. In other words,

-

King said, the group felt that ANRs should be established for fiber, for example, because even though it is not an essential nutrient, it is a food component that has public health relevance.

- The group suggested that acceptable macronutrient distribution ranges be established for carbohydrates, protein, and fat, and that these ranges should be for reducing chronic disease risk associated with the intake of these macronutrients. King emphasized, though, ANRs should be set for protein also because it is an essential nutrient.

- The group felt it was important to consider nutrient–nutrient interactions, such as protein–energy interactions (i.e., as energy intake increases, dietary requirements for protein can decline because the protein is no longer used for energy needs) and vitamin E–polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) relationships. These should be characterized quantitatively, if possible.

- Additionally, it is important to consider subpopulations with special needs, such as smokers and their vitamin C requirements, keeping in mind, however, that ANRs are for apparently healthy individuals.

Framework for Estimating Upper Nutrient Levels (UNLs)

The group developed a separate framework for estimating UNLs:

- A UNL is the highest level of a habitual nutrient intake that possesses no risk of adverse health effects in almost all individuals in the general population.

- UNLs can be determined by applying an uncertainty factor to the no-observed-adverse-effect-level (NOAEL) or lowest-observed-adverse-effect-level (LOAEL), but the magnitude of the uncertainty factors need to be considered on a case-by-case basis. In other words, King explained, it cannot be assumed that the uncertainty factor is the same for all nutrients. “We spent a long time on this particular issue,” she recalled.

- The group suggested that uncertainty factors be estimated from a list of potential effects of excessive intakes available in the literature.

- “But what we really need,” King continued, are biomarkers that anticipate adverse effects associated with higher levels of nutrient intakes.

- Dose–response data for determining UNLs are limited, especially among pregnant and lactating women, children, and the elderly.

After describing these components of the framework for estimating UNLs, King remarked that there are many research issues that still need to be addressed to fully develop these concepts.

Criteria for Selecting NIV Indicators

Selecting an indicator for an average nutrient recommendation is a challenge, King continued. The Florence group came up with several criteria for selecting NIV indicators:

- There should be a demonstrated dose–response function. In other words, King explained, there should be an observed change in the response of the indicator as intake changes.

- The indicator should be responsive to inadequate or excessive intakes of a single nutrient.

- It should be resistant to rapid daily changes in the response to inadequate, adequate, or excessive intakes. For example, when an individual takes a high dose of vitamin C, their urinary ascorbic acid levels change quite quickly. Thus, urinary ascorbic acid levels would not be an acceptable indicator; they change too quickly and do not reflect the tissue use of vitamin C.

- It needs to be easily measured or accessible with noninvasive methods. Blood samples, for example, would be fine, but tissue biopsies would not be considered noninvasive.

- It should not be responsive to environmental changes other than nutrient intake from all sources. For example, smog should not influence the indicator.

The group recommended that there be a single outcome measure for each nutrient and age group. In other words, King explained, with zinc, for example, use a single indicator, such as plasma zinc level, and do not try to also use a biomarker of inflammation as well. Using more than one outcome measure, she said, “would make the whole process very complicated and probably unwieldy.” Additionally, because an NIV will vary with population and outcome, it was recommended that the basis of an NIV be fully described, including how the indicator was selected.

Bioequivalence

According to King, in its discussion of bioavailability, the Florence group developed a concept they called bioequivalence. King remarked that she had not seen the concept used much since the 2007 publication and was unsure if that was because the concept was not readily understood or

because it was not needed. Nonetheless, she said, the group did spend some time discussing it and decided that bioequivalence of a nutrient can involve bioavailability or bioefficiency.

They defined bioavailability as it is typically defined, King explained: the proportion of the ingested nutrient absorbed and used through normal metabolic pathways. Because bioavailability is influenced by dietary and host-related factors, the group spent a lot of time, she recalled, thinking about the bioavailability of zinc, calcium, iron, retinol, and folate in particular. The bioavailabilities of all of these nutrients are influenced by the amount of nutrient in the diet, as well as whether an individual is growing, if a woman is pregnant, and other host-related factors.

King explained that they defined bioefficiency as the efficiency with which ingested nutrients, such as the carotenoids and various tocopherols, are absorbed and converted to active forms.

Multiple physiological and food factors can influence bioequivalence, the Florence group recognized. These include enhancers or inhibitors of absorption; differences in efficiency of the metabolic conversions that occur for the carotenoids and the tocopherols; and food processing, treatment, and preparation. King added that the group also spent some time thinking about how infection in an individual, and how nutrient–nutrient interactions, can influence bioequivalence.

Life-Stage Factors

They also addressed various life-stage factors, King continued, again with many long discussions beginning with how to set life-stage groups. For example, should it be done by age? King mentioned that many people are now setting life-stage groups by age (e.g., 0–12 months of age, 1–3 years, 3–6 years, and so on). But should it be done by function instead, for example, whether a child is growing at a certain rate or not? Or, should it be done by potential purposes, that is, by the age at which a child is receiving complementary foods, such as from 6 to 36 months?

Regardless of how life-stage groups are set, the same life-stage groups should be used for all nutrients, the Florence group emphasized. For example, there cannot be one set of life-stage groups for vitamin A and another for folate. “This would make it virtually impossible to apply the values,” King said. “So we have to decide on how they are going to be and then use it for all of the nutrients.”

They chose to treat pregnancy and lactation as two distinct groups. In other words, King said, do not break down pregnancy into trimesters and make different recommendations for the first, second, and third trimesters. “This would be very difficult to implement,” King said, “and, frankly, the physiology of pregnancy alters the utilization of nutrients, so we are not

convinced that we really need to make different recommendations for the trimester.”

Finally, after spending some time talking about how to derive standard weights and heights for a population, they decided to use the WHO growth standards for infants and children. Additionally, they decided to use the average weight of men and women at 18 years of age throughout the adult years, or, in other words, King said, not to allow “an increase in body weight with age.” She remarked that this decision seemed appropriate 10 years ago. But today, given how common it is for adults to gain weight after 18 years of age, she said, “I’m not sure we might see it the same way.”

Other Considerations

King described two additional sets of issues that were deliberated at the Florence meeting. The first pertained to extrapolation methods and how to extrapolate from one life-stage group to another when data are lacking. “There is no correct way to do this,” she said. “It has to be done on an individual nutrient basis. But what is really important is transparency.” Regardless of the method used, it needs to be fully explained. Often it is done by body size or the weight or metabolic weight of an individual. Or, it can be done by energy intake. Or, factorial estimates for growth or milk production during lactation can be used.

Additionally, King and colleagues spent some time thinking about genetic variation in NIVs and agreed that it is very important to consider the prevalence of genetic variation, as well as the penetrance of that variation within a population. The group concluded that it is unlikely that gene–gene interactions will affect NIVs because of the low prevalence associated with highly penetrant genes. Additionally, the group considered whether or not there might be gene variants that are linked to nutrient sensitivity (e.g., salt sensitivity), although they did not come up with any conclusions. King commented on how much this area of research has expanded in the past 10 years and that Patrick Stover would be providing an update in his presentation (Stover’s presentation is summarized in Chapter 6).

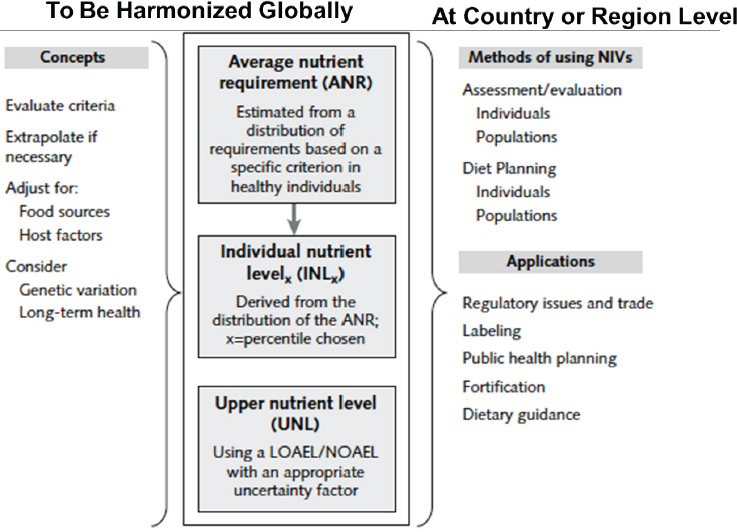

NIV Framework

The NIV framework developed by King and colleagues at the 2005 Florence meeting is illustrated in Figure 2-1. The committee focused most of its attention on the two left columns, King noted.

As illustrated in the middle column of Figure 2-1, the group decided to make recommendations for only two types of values: ANR and UNL. However, it recognized that one can also derive an individual nutrient level (INL) from the ANR, often by extrapolating from the ANR up to a higher

NOTE: LOAEL = lowest-observed-adverse-effect-level; NOAEL = no-observed-adverse-effect-level.

SOURCES: Presented by Janet King, HMD Workshop, Rome, Italy, September 21, 2017 (King and Garza, 2007; reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications, Inc.).

level (e.g., 95 percent of the population, 97.5 percent, or even 85 percent if a committee so chooses).

The concepts that serve as the basis of these recommendations include (i.e., left column in Figure 2-1): having a clear understanding of the criteria for the recommendations, how to extrapolate if necessary, how to make adjustments for differences in food sources and host health, and whether there is a need to consider genetic variation or long-term health.

The right column in Figure 2-1 lists other aspects that the committee felt need to be considered at the country or region level, specifically how to use NIVs for assessing or evaluating the adequacy of nutrient intakes in individuals or populations and how to plan diets for individuals and populations. King noted that Suzanne Murphy would be discussing these and the other applications of NIVs in more detail (the summary of Murphy’s presentation follows).

APPLICATIONS AND USES OF NUTRIENT INTAKE RECOMMENDATIONS2

Suzanne Murphy provided an overview of the uses of nutrient intake recommendations to assess and plan intakes for both individuals and populations; she also reviewed the many critical health applications that depend on accurate nutrient intake recommendations.

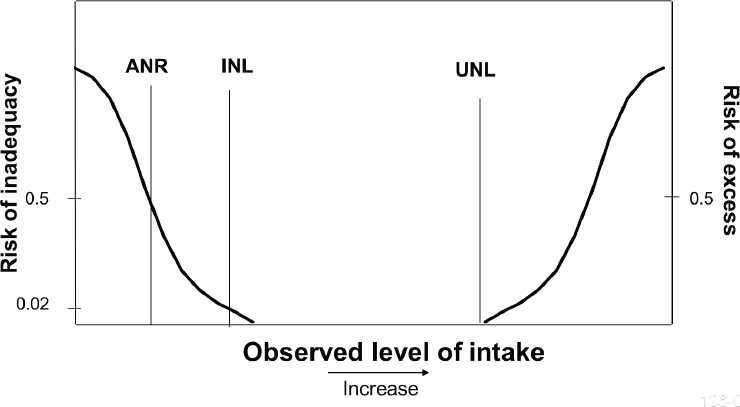

She began by emphasizing the importance of using the paradigm illustrated in Figure 2-2. For individuals, intake should be between the recommended INL and the UNL that is not likely to pose a risk of adverse effects. For groups, most people should have intakes between the ANR and UNL (see Figure 2-3).

This paradigm and its methods for evaluating individual and group intakes can be applied to four categories of health applications, Murphy explained: (1) assessment applications for individuals, including evaluating a person’s diet; (2) planning applications for individuals, such as offering dietary advice; (3) assessment applications for groups, including evaluating dietary surveys; and (4) planning applications for groups, including designing food fortification programs.

To explain the importance of nutrient standards to policy makers, government agencies, and others, collaborators in the United States and Canada spent about 2 years, Murphy said, developing a two-sided handout listing 10 critical health applications that depend on nutrient standards. While developed for the United States and Canada, the list is universally applicable, in Murphy’s opinion. She described each application:

- Food-based dietary guidelines: Most countries have these, Murphy noted. Examples include the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Patterns, and Canada’s Food Guide. WHO, FAO, and others have communicated the importance of considering nutrient priorities when developing food-based guidelines (FAO/WHO, 1998). Yet, Murphy said, “you’d be surprised how many people in the United States don’t recognize that link.”

- Nutrition monitoring: Examples include the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Without nutrient standards, Murphy said, it would be impossible to assess nutrient adequacy in the country based on food intake surveys. Both household- and individual-level surveys can be used to examine the prevalence

___________________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Suzanne Murphy, Ph.D., R.D., professor emerita and researcher, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii.

NOTE: ANR = average nutrient level; INL = individual nutrient level; UNL = upper nutrient level.

SOURCE: Presented by Suzanne Murphy, HMD Meeting, Rome, Italy, September 22, 2017 (reprinted with permission).

NOTE: ANR = average nutrient requirement; UNL = upper nutrient level.

SOURCE: Presented by Suzanne Murphy, HMD Meeting, Rome, Italy, September 22, 2017 (reprinted with permission).

-

of inadequacies. She showed a NHANES (2001–2002) bar chart illustrating the prevalence of inadequacy of nutrients in the United States, Although vitamin E tops the list, its inadequacy prevalence (93 percent) is controversial, Murphy said, and can probably be disregarded. However, the others, in her opinion, are more reasonable and allow policy makers to decide where to focus their efforts: second to vitamin E is magnesium, at 56 percent inadequacy, followed by vitamin A at 44 percent; vitamin C at 31 percent; vitamin B6 at 14 percent; zinc at 12 percent; folate at 8 percent; copper, phosphorous, and thiamin all at 5 percent; iron at 4 percent; protein at 3 percent, and carbohydrate, selenium, niacin, and riboflavin all at less than 3 percent.

- Food assistance programs: Many programs depend on nutrient standards to design their food aid, Murphy said, including school meal programs, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), as well as Administration on Aging programs.

- Health professionals: Health professionals use nutrient standards for dietary counseling and education and to design diets for groups of people (e.g., in hospitals, prisons, long-term care).

- Nutrition research: Knowledge of nutrient requirements contributes to the study of how diet helps to prevent disease. Additionally, Murphy said, knowing where data on nutrient requirements are missing provides a frame of reference for research. She noted that harmonization would have an effect on the latter application in particular (i.e., by helping to identify missing data on requirements).

- Nutrition labeling: This too, Murphy said, is a very global application (see item 10).

- Military: Murphy mentioned a past committee on military nutrition that not only used nutrient standards but also developed their own in some cases. Nutrient standards remain important for the military for numerous applications, she said.

- Food and supplement industries: These industries can use nutrient standards to develop healthy foods and safe supplements, Murphy said.

- Food policies: This includes policies at many levels of government, Murphy noted, and also at schools.

- Global nutrient standards: Providing a framework for nutrient standards is “why we are here today,” Murphy said. A global approach to setting nutrient standards has many potential applications such as assisting the Codex Alimentarius Commission in setting its standards and recommendations, establishing interna

tional fortification policies, and promoting trade by standardizing nutrition labeling.

In conclusion, Murphy stated that it is possible to harmonize methods used to assess and plan intakes for individuals and populations. Although many of the applications she listed depend on country-specific guidelines, she said, “We can still learn a great deal by sharing our experiences.”

Finally, Murphy listed several advantages of harmonization. These include less redundancy (i.e., more efficient use of professional time), the pooling of limited funds so there is no large burden on any specific country or region, a more timely update process so out-of-date values will not lead to inappropriate policies, and increased understanding of uses and more appropriate applications of recommendations. She noted that this last advantage is an often overlooked one.