Roots and Trajectories of Violent Extremism and Terrorism: A Cooperative Program of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and the Russian Academy of Sciences (1995-2020) (2022)

Chapter: 3 Radiological Challenges: Security, Sources, Waste Sites, and Disposal

3

Radiological Challenges: Security, Sources, Waste Sites, and Disposal

In Moscow during 1993, a cesium-137 source was placed in an armchair killing one person; and in 1995, another cesium-137 source was discovered in a public park also in Moscow. In Chechnya during 2002, a Russian army team used robots to retrieve two stolen sources. Then in the Russian Far East in 2003, thieves stripped off the metal casings of radioactive thermal generators at three lighthouses.

– NAS report, 20071

The world has not yet given adequate attention to the dangers of misuse of radioactive sources, spent nuclear fuel, and radioactive waste to make radiological devices. The greatest consequences of detonation of such a device are public fear, potentially enormous cleanup costs, and consequent economic losses. There is essentially no barrier to terrorists obtaining radioactive material. Three new inter-academy projects will be undertaken to address this issue.

– Joint statement of the presidents of the NAS and the RAS, 20022

While protecting well-known storage, assembly, and operational locations for radioactive material is very important, terrorists are often on the move searching along the way for any type of material that could cause damage. Therefore, security specialists should be aware that terrorists may come upon radiological material in unusual places, which are not designated or known as facilities having such material.

– NAS report, 20193

BROAD AGENDA OF ACTIVITIES

This chapter addresses the extensive cooperation of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and a wide array of Russian partners in addressing many nuclear-related challenges, with most activities carried out in Russia. The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) was involved in almost all of these activities, serving as a partner or as a facilitator in arranging contacts and visits with approval of many Russian government agencies. Issues concerning arms control are not included in this report. Box 3-1 highlights many of the most important activities.

DETERIORATION OF STRICT SECURITY THROUGHOUT RUSSIA’S NUCLEAR COMPLEX

As Russia was slowly recovering from the economic catastrophe that engulfed the country during the late 1990s following the breakup of the Soviet Union into 15 independent states, the U.S. Departments of State, Defense, and Energy (DOE) encouraged the NAS to work with the RAS and appropriate Russian research centers in assessing the security of nuclear material in Russia. The U.S. departments provided significant financial support for field assessments, workshops, and studies. They were concerned that although intergovernmental programs were having some effect on upgrading the security at many Russian facilities, the gravity of the threat involving nuclear material was actually increasing.

The continuing decline in the Russian economy had severely affected the economic well-being of Russian government officials, nuclear specialists, and workers who had access to direct-use material. While such material must be closely guarded even in the best of economic times, economic deprivation had increased the likelihood of such material disappearing from Russian facilities as families throughout the country struggled to meet everyday needs.4

At the same time, expanded access to Russian facilities by American participants in intergovernmental programs provided new insights into the vast Russian nuclear complex. More extensive illegal diversion of material and more pervasive weaknesses of protection systems than had been anticipated

were uncovered. The Russian government also recognized the magnitude of the problem, as the deputy minister for atomic energy announced that there had been 28 incidents of illegal access to nuclear material at facilities throughout the nuclear complex between 1992 and 1995. Other officials acknowledged continuation of attempted thievery in subsequent years. Also, NAS specialists were told by managers of several important Russian facilities that penetration of their security systems had become a major concern.5

As an example of NAS involvement, in 1999 a team of American and Russian experts visited 13 Russian facilities where tons of nuclear material were available for a variety of purposes. The primary focus of the visit was to ascertain the status of the materials protection, control, and accountability (MPC&A) activities at the facilities. Particular attention was given to possible weaknesses in accountability, which was suspected of falling short in many respects. Soon thereafter, other NAS teams visiting Russia heard reports from managers of additional facilities that the number of attempted thefts of dangerous material continued to be of concern. In response to such reports, the Russian government required many facilities to tighten their control of nuclear material; and the number of attempted thefts during subsequent years dropped significantly.6

Also in 1999, the NAS advised the DOE that although the priorities in the MPC&A programs being supported were generally consistent with the most urgent needs in protecting nuclear material, the following issues required prompt attention:

- There was very slow progress in installing and putting into operation material accountancy systems at Russian sites—including even the basic step of ensuring complete and accurate inventories of nuclear material.

- With several important exceptions, only limited progress had been made in efforts to consolidate direct-use material at a variety of sites into fewer buildings to reduce the number of locations that required the highest level of security.

- Neither DOE nor Russian institutions had developed strategies to ensure the long-term sustainability of the upgraded systems for MPC&A that had been established.

- Inadequate progress had been made in providing appropriate transport systems and vehicles to ensure that direct-use material was secure during shipments within and between sites.

Thus, the remaining tasks were considered “huge” within both the U.S. and Russian governments.7

In 2005, the NAS issued its third assessment of the DOE program, which was designed to assist Russian counterparts in the upgrading of MPC&A systems. The report strongly supported many of the pioneering efforts of DOE. At the same time, there were important findings that called for additional actions. In general, these findings, supplemented with statements by many Russian security officials, indicated that security enhancements installed through the DOE program probably played an important role in significantly reducing the number of attempted thefts of dangerous nuclear material from Russian facilities. But additional efforts were in order. Among the findings in the report calling for future security measures were the following:

- Russian experts remained concerned about terrorist attacks on nuclear facilities focused primarily on sabotage, which could be prevented through guards and perimeter defenses. However, insufficient priority had been given to using modern electronic and optical methods to assist in preventing “insider” theft of material when the economy was in a very depressed state.

- Weapons-usable material was not as well protected from outsider penetration as it should have been in view of the increasingly aggressive terrorist activities within Russia.

- In determining activities at specific Russian facilities, DOE representatives usually dominated the discussions with Russian counterparts about upgrade priorities and approaches. An administrative culture that regarded Russian counterparts as “contractors with checklists” had emerged within DOE.

- Even taking into account progress in many aspects of protecting materials of concern during a decade of cooperation, the overall program had moved slowly in bringing hundreds of tons of weapons-usable material under greater control.

- The practice of relying on large DOE contracts with Russian counterpart organizations that had originally been adopted was replaced with the adoption of small contracts due to complaints by the U.S. Congress about the ease of misuse of funds. The increase in the number of contracts that expanded administrative processes delayed implementation of important activities by many months.

- Accountability of the amounts, locations, and uses of nuclear material continued to require more attention.

A key concern of the report was the lack of appreciation of the importance of indigenization of the program, with the following overarching components:

- An unwavering political commitment by the Russian government from the political to the institutional levels for maintaining a high level of proven security measures in protecting nuclear material.

- Adequate Russian resources at the facility level to fulfill such a commitment.

- Approaches to installing security systems that were not only technically sound but fully embraced by Russian managers and specialists.8 Box 3-2 highlights lessons learned in effectively addressing indigenization.

Most of the foregoing changes based on lessons learned were, in time, incorporated into MPC&A programs that were supported by the DOE in many areas of Russia. However, these changes remain instructive when addressing large foreign-financed technical assistance programs in other countries that are attempting to quickly take charge of their own industrial development challenges.

TENS OF THOUSANDS OF POTENT IONIZING RADIATION SOURCES IN USE AND OUT OF USE IN RUSSIA

While DOE was making good progress in upgrading its programs to improve security of weapons-usable material at many Russian facilities, the NAS began to consider other aspects of radiological security in response to new requests from DOE. Of special concern was the handling of ionizing radiation sources (IRSs) for a variety of purposes in the medical, agricultural, food, geophysical, energy, and industrial fields.

For decades, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) had warned the world that packing conventional explosives together with radioactive material and detonating such a radiological dispersal device to kill and/or terrorize people—the dirty bomb scenario—were within the means of some terrorist groups. This warning was particularly strong when focusing on radioactive material in Russia. In addition to the large inventory

of inadequately protected uranium and plutonium that could be used in nuclear weapons, many hundreds of Russian institutions throughout the country had IRSs or other forms of nuclear material that could become components of dirty bombs.

After years of frustration among nuclear specialists within both the United States and Russia about the lack of adequate attention being given to dangerous IRSs, in 2006 DOE requested the NAS to assess the threat posed locally and internationally by IRSs in Russia. The most common uses of IRSs included the applications set forth in Box 3-3.

During the early 2000s, NAS specialists learned many details about the problems Russia had inherited from the former Soviet Union in controlling a very large number of potent IRSs throughout the country. They probably numbered in the tens of thousands. The Mayak Production Association was the leading Russian manufacturer of IRSs—for domestic uses and for export. Many of the uncontrolled IRSs had been produced at Mayak and were then sold or given to hundreds of organizations.

There were many concerns over the control of IRSs. A particularly important focus was the hundreds of radioisotope thermoelectric generators located in the northern and central reaches of the country, with formidable logistics required to locate and retrieve those that were no longer needed. As to less potent sources, tens of thousands of IRSs were discovered in hundreds of institutions, enterprises, hospitals, and other facilities—including many abandoned buildings—located within reach of skilled criminals. In addition,

there were reports of IRSs being discovered in open fields in central Russia in the spring as the snow melted.

Reliable estimates or even approximate estimates of the number of IRSs being used, in storage, or in an abandoned state in Russia had never existed. The total may have been more than 1 million IRSs when Russia became an independent country. Thousands were believed to have been of sufficient strength to be of considerable concern to the IAEA, which has long classified IRSs according to their potency.

Russian and American participants in an NAS-RAS project during 2006 visited a variety of Russian facilities to improve their understanding of the state of security surrounding the possession of IRSs. Their reports on visits to five facilities included the following observations:

- Four cesium-137 sources of about 5,000 curies each were maintained in an unprotected room of a poorly guarded facility adjacent to a forest.

- Another facility had 6,000 sources of various kinds. In one building, a flimsy door opened into a room with two irradiators that used cobalt-60 and cesium-137 sources. In an adjacent building, gamma-type irradiators could be wheeled out in a hand cart.

- A dormant facility retained 36 sources of cobalt-60 with a total activity of 20,000 curies. The storage room was on the ground floor opening directly onto the courtyard. The fire and security alarms were outdated with externally exposed cables.

- A facility containing 27 sources of cobalt-60 and 15 sources of cesium-137 was located within 300 meters of a metro station, a school, and apartments. There were no restrictions on entering the portion of the building containing the sources. The containment room was subjected to surface and subsoil water, which had weakened the strength of the walls and floor of the building.

- Forty-two sources of various types, which had not been used for years, were located in a crumbling factory building. The guard force was not professionally trained. The facility had no fence and did not connect to the municipal alarm system. On the site were several commercial firms, which had no legal relationship to the storage facility, which was on the verge of bankruptcy.11

Based on the foregoing observations together with numerous comparable testimonials by Russian experts, the NAS recommended several immediate steps to help strengthen the security surrounding the possession of IRSs:

- The DOE’s limited program of quick security fixes should be expedited. Of particular importance was the end-of-life-cycle management of IRSs that were no longer wanted, including many that had been simply abandoned.

- The DOE should develop a comprehensive plan for working with Russian counterparts to reduce the overall risk and consequences of radiological terrorism.

- Cooperation should be developed within the context of the overall Russian program for ensuring adequate life-cycle management of IRSs throughout the country and should take into account activities of other external partners.12

Adding to the urgency of reducing the likelihood of successful terrorist activities, which included dissemination of IRSs, were the observations of a team of collaborating Russian experts. They were concerned about (a) near-term radiation effects of inadequately protected IRSs on the population within hours or days, and (b) delayed effects due to prolonged irradiation resulting from environmental contamination. These experts also warned about social, economic, political, psychological, and demographic consequences to society, including the following:

- Unnoticed long-term health effects on the general population, contamination of habitable structures, and loss of property values.

- Costs of both immediate cleanup and long-term radiation-reduction measures to protect the population.

- Population movement away from contaminated areas.

- Withdrawal from the economy of activities in contaminated areas.

- Negative attitudes toward nuclear power development.

- Long-term aquifer contamination.13

Russian colleagues also explored the feasibility and possible consequences of the following five scenarios involving the possible acquisition of radioactive material and then the launching of attacks by terrorists:

- Planting a radioactive source containing cobalt-60 in a subway car.

- Detonation in the subway system of a strontium-90–based dirty bomb.

- Dispersion of cesium-137–impregnated material over an urban area.

- Detonation of a dirty bomb based on americium-241 in or near a large city.

- Liquid dispersion of a radiation source over a segment of an asphalt road leading to a major highway that would extend the contamination picked up on the tires of vehicles to other streets.14

Another report concluded that IRSs are at times found in scrap metal, many sources are discovered in vehicles and transport containers, and theft is a common event.15

SECURITY AT MANY RADIOLOGICAL WASTE SITES IN RUSSIA

Beginning with the challenge in assessing the extent and impact of the debris from the catastrophe at Chernobyl, for many years collaboration in assessing the collection, handling, and disposition of radioactive waste became an important activity of the NAS and the RAS. Three months after the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, the NAS was one of several sponsors of an international conference in a hastily erected temporary shelter a few kilometers from the scene of the explosion. The focus of the conference was on the extent and impact of environmental contamination. The NAS played an important role in inviting carefully chosen American experts to attend the conference and also in identifying appropriate participants for follow-up studies that continued for decades.16

The many movies and books highlighting deterioration of wooded areas and elimination of animals and insects that had inhabited the forests soon encouraged greater international attention to ecological impacts. The early NAS emphasis on ecological impacts helped facilitate NAS-RAS cooperation involving a variety of colleagues from Moscow and Obninsk.17

In more recent years, the NAS and the RAS sponsored a series of workshops on radiological challenges, commissioning preparation of reports on the disposal of radioactive wastes resulting from the growth of the nuclear industry in Russia. During the early 2000s, the focus was on the conditions and some of the practices at 15 of 27 well-known Russian waste sites. The NAS, together with the RAS, invited many Russian scientific leaders to prepare technical essays on activities at the sites.18 Several Russian scientists who participated were familiar with U.S. approaches, having visited the proposed disposal site in Yucca Mountain, Nevada.19

There were subsequent inter-academy activities directed to the challenges of safe and efficient disposal of radioactive waste. Several meetings and workshops sponsored by the NAS and the RAS addressed the possibility of a Russian initiative to establish an international waste repository for spent nuclear fuel in Russia, which is discussed below. More recently, an important focus during inter-academy discussions has been on new technologies for expanding deep disposal, upgrading radioactive waste containers, and introducing innovative approaches for temporary storage of waste. Throughout this time, an important partner for the NAS has been the Russian enterprise RADON, which leads Russia’s national effort to provide safe storage and processing of nonmilitary nuclear waste.

To set the stage for many activities, in 2003 the NAS and the RAS launched a series of workshops on the handling of radioactive waste. The first workshop was titled “End Points for High-Level Radioactive Waste in Russia and the United States.” One area of particular interest to American experts was the Russian program to chemically process most of its solid radioactive waste before burial. A related area of special interest was Russian experience in deep-well injection of large amounts of low-level and intermediate-level waste generated by several radiochemical facilities. A third development of global interest was the dumping of liquid radioactive waste into Lake Karachay and the ensuing Techa Reservoir Cascade adjacent to the Mayak industrial facility.20

In view of the continuing international interest in the environmental problems in and near Mayak, a few comments on the situation in that area are offered. Eight industrial reservoirs for liquid radioactive wastes were established to support defense program operations, and these reservoirs had many long-term impacts. Also in 1957, a leak at a liquid radioactive holding tank in the area resulted in the creation of the well-known East Urals Radioactive Trace, with two reservoirs used to store medium-level wastes. Next a man-made reservoir was built to store low-level liquid waste. Then unexpectedly, the wind dispersed radioactive substances from an exposed shoreline.

Finally by 2009, program objectives had been established as follows:

- Reduce and ultimately halt all discharges of liquid radioactive waste.

- Eliminate the most radiologically hazardous reservoirs.

- Ensure safe operations of the Techa Cascade of reservoirs.

- Reduce the volume and radioactivity levels of high-level waste stored in holding tanks.21

Turning to many other waste challenges throughout the country, the following objectives were given high priority:

- Consolidating excessive nuclear materials in a few reliably protected facilities.

- Developing and refining technologies for safe and efficient defueling, dismantling, and disposing of decommissioned nuclear-powered submarines.

- Transporting by secure means spent nuclear fuel between facilities.

- Developing standards for highly durable waste forms.

- Immobilizing different types of high-level wastes.

- Developing unified objectives for selection of geological media and sites for high-level wastes for long-term storage and disposal.

- Promoting research on methods for processing solid nuclear fuels that produce much less radioactive waste than the existing PUREX process.22

In 2007, the NAS and the RAS—together with Rosatom, the International Science and Technology Center, and the Geocenter Moscow group—sponsored a workshop on the status of radioactive waste sites that led to preparation of a landmark collection of extended abstracts prepared by more than 60 Russian experts from 20 institutions. They described in detail the status of 15 important radioactive waste sites in Russia that needed greater attention to contain the wastes. Of continuing interest to the international participants were the environmental conditions at or near the Mayak complex described in many abstracts.23

In parallel with the focus on upgrading activities at Russian waste sites were two NAS-RAS assessments of the feasibility of establishing an international waste site in Russia for receiving and storing international spent nuclear fuel elements from many countries. The first NAS-promoted assessment of this proposal in 2003 addressed the following issues:

- Legal issues, including liability during shipment and reception in Russia of fuel in accordance with international liability conventions.

- Russian legislation for internationally controlled operations.

- Current nuclear power industry trends that would be influenced by a storage facility in Russia.

- Interim storage experience in Asia and Europe.

- A U.S.-Russian agreement on safeguards, physical protection, and U.S. consent rights for some activities, including right of return if requested and separation of plutonium and uranium.24

A follow-on assessment in 2005, while expanding on some of the topics discussed in 2003, focused on the following issues:

- Handling of spent nuclear fuel—the international experience.

- Site selection for spent fuel storage and, when appropriate, disposal of high-level waste.

- Establishment of an international storage facility in Russia.

- Utilization of high-level waste.25

While the concept of an international spent nuclear fuel storage facility in Russia was realized, the inter-academy reports probably have saved the Russian, U.S., and other governments considerable time and financial expenses in avoiding blind alleys when issues concerning reprocessing, storage, and waste disposal have been raised. Looking to the future, spent nuclear fuel probably will continue to be transported across borders, including the Russian border, for reprocessing, storage, and/or disposal. The presentations included in the reports of the U.S. and Russian academies addressed many important issues that will likely remain of international interest.

STRENGTHENING RADIOLOGICAL SECURITY NOW AND IN THE FUTURE26

In 2019, after a pause of a decade in NAS-RAS collaborative efforts to address radiological security, an NAS-RAS workshop on the topic of violent extremism and radiological security was held in Helsinki. This was the first of three workshops on the topic supported primarily by DOE, with additional support provided by the Richard Lounsbery Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Upon learning that DOE could not support activities in Russia, at the same time NAS selected Helsinki as the first venue, since for many years the NAS had maintained strong professional relationships with several relevant Finnish institutions.

The second NAS-RAS workshop focusing on radiological security was held in Moscow after DOE decided that such a nongovernmental endeavor in Russia would be important in “keeping the door open for cooperation” while gaining more incisive on-the-ground insights into developments in

that country. DOE was awaiting an improvement in the political environment when the department’s experts would be able to resume long-standing relationships with Russian government officials that were being only partially maintained through events organized by the IAEA in Vienna. The second workshop also included participation by several European specialists since they had brought important perspectives to the table in Helsinki. As this report was being completed, the NAS was awaiting confirmation from all interested parties that the date of the third workshop in the series—also to be held in Moscow—would soon be confirmed.

There was a significant change in the focus of the new series of three workshops compared with the orientation of the many NAS-RAS events that focused on radiological issues during earlier years. The emphasis during the previous 15 years of collaborative efforts was primarily on developments in Russia—technological capabilities, research and development priorities, and experiences in addressing radiological challenges that had long historical roots during Soviet times. After the pause in cooperation, the workshops discussed in this section address recent developments within both Russia and the United States as well as global trends. The American participants were no longer part-time mentors for Russian colleagues, as the Russians became well aware of many developments abroad concerning the topics on the agendas.

Among the many technical issues on the agendas of the workshops have been the following:

- Reducing insider threats, including security culture among employees; required security facilities and procedures; coping with threats, clandestine storage, and unauthorized transportation of sources; malevolent uses of sources in vulnerable spaces (e.g., shopping malls, sports venues, and transportations terminals).

- Alternative technologies to replace the use of cesium-137 as the radiation source for medical, agricultural, food, industrial, geological, and other purposes; policies, resources, and availability of equipment to support replacement; institutional difficulties in making transitions; and model companies, laboratories, and facilities.

- Permanent disposal of high-level radioactive waste: boreholes and other approaches.

- Improved containers for transportation and storage of low-level radioactive waste.

- Immediate responses to recognized radiological sources at the national and institutional levels, and procedures for accounting for radiological sources of special concern.

- Radiation forensics, including detecting the presence and characteristics of irradiated material.

Among the important information reported during the workshops were presentations on the following activities:

- Russian specialists, in cooperation with international partners, had removed almost 1,000 radioisotope thermoelectric generators from the northern regions of Russia and 4 from Antarctica.

- American institutions had replaced hundreds of cesium-137 sources in hospitals, agricultural centers, and industrial facilities with x-ray (linac) equipment and with other types of approaches.

- The IAEA’s database indicated that in 2018, there were 253 incidents in 49 countries of unauthorized use or other inappropriate activities involving nuclear and other radioactive materials.

- As to forensics, there are alternative ways to measure the composition of particles without destroying the samples, ranging from imaging systems to sophisticated mass spectrometry. Alpha track radiography can also be an important tool for sampling of particles in soil and in other material.

- The Lepse floating storage facility near Murmansk had been developed and deployed for operations. Very quickly, the first parcel of nuclear material was sent to Mayak for reprocessing in 2019. International cooperation became important in closing the fuel cycle for use of nuclear energy in the Arctic.

- A plan was developed to create a deep repository for radioactive waste in a granite base in Zheleznogorsk. The plan requires 50 years for implementation while taking into account environmental concerns in the Baikal region.

NOTES

1. NRC (National Research Council). 2007. U.S.-Russian Collaboration in Combating Radiological Terrorism. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, pp. 46–47.

2. Schweitzer, G. E. 2004. Scientists, Engineers, and Track-Two Diplomacy. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, p. 122.

3. NRC. 2019. The Convergence of Violent Extremism and Radiological Security: Proceedings of a Workshop–in Brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

4. NRC. 1999. Protecting Nuclear Weapons Materials in Russia. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, p. 1.

5. Ibid., p. 3.

6. NRC. 2006. Strengthening Long-Term Nuclear Security: Protecting Weapon-Usable Material in Russia. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, p. 2.

7. Op. cit., NRC, 1999, p. 3.

8. Ibid., p. 8.

9. Op. cit., NRC, 2006, p. 57.

10. Op. cit., NRC, 2007, p. 26.

11. Ibid., p. 54.

12. Ibid., pp. 84–85.

13. NRC. 2009. Cleaning up Sites Contaminated with Radioactive Material: International Workshop Proceedings. F. Parker, K. Robbins, and G. Schweitzer, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, p. 162.

14. Ibid., p. 170.

15. Ibid., p. 29.

16. Op. cit., 2007, p. 21.

17. Schweitzer, G. E. 1989. Techno-Diplomacy: U.S.-Soviet Confrontations in Science and Technology. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 70, 266.

18. Op. cit., 2007, entire report.

19. Schweitzer, G. E. Conversation with Russian visitors to the United States, 2006.

20. NRC. 2003. End Points for Spent Nuclear Fuel and High-level Radioactive Waste in Russia and the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, p. 4.

21. Glagolenko, Yu. V., Ye. G. Drozhko, and S. I. Rovny. 2009. “Experience in Rehabilitating Contaminated Land and Bodies of Water Around the Mayak Production Association,” in Cleaning Up Sites Contaminated with Radioactive Materials: International Workshop Proceedings. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, p. 81.

22. Op. cit., 2003, p. 11.

23. Op. cit., 2007, pp. 26, 50.

24. NRC. 2005. An International Spent Nuclear Fuel Storage Facility: Exploring a Russian Site as a Prototype: Proceedings of an International Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, pp. ix-xi.

25. NRC. 2008. Setting the Stage for International Spent Nuclear Fuel Storage Facilities: International Workshop Proceedings. K. Robbins and G. Schweitzer, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, pp. ix–x.

26. NRC. 2019. The Convergence of Violent Extremism and Radiological Security: Proceedings of a Workshop–in Brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

27. NRC. 2020. Scientific Aspects of Violent Extremism, Terrorism, and Radiological Security: Proceedings of a Workshop–in Brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

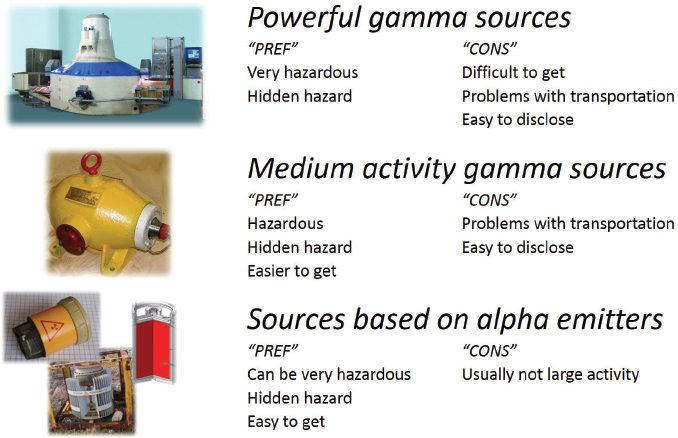

Source: Presentation by Mikhail Diordiy on spent radiation sources storage in containers to prevent terrorism and extremism, December 12, 2018.

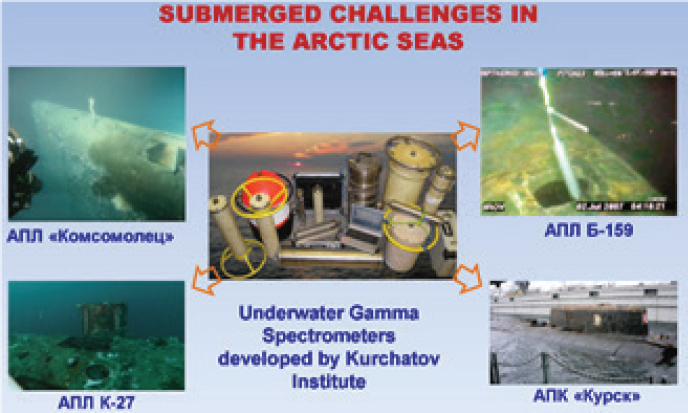

Source: Presentation by Oleg Kiknadze, with information from Kurchatov Institute, December 2019.