From Molecular Insights to Patient Stratification for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders: Proceedings of a Workshop (2022)

Chapter: 6 Enabling Patient Stratification through Deep Phenotyping and Biomarker Discovery

Biomarkers aid in treatment development across the continuum of the drug discovery and development pipeline as measures of target engagement, disease risk, presence and/or status of disease, treatment effect, and safety, said Linda Brady, director of the Division of Neuroscience and Basic Behavioral Science at the National Institute of Mental Health. In clinical trials they are also used to identify subjects at risk of disease and stratify trial participants into subgroups that are most likely to benefit or least likely to experience harm from an intervention, she said. Although animal models can be useful in the search for biomarkers of target engagement or pharmacodynamic treatment response in preclinical studies, they are less useful in the development of prognostic markers of patient enrichment and stratification, added Danielle Graham, head of fluid biomarkers at Biogen.

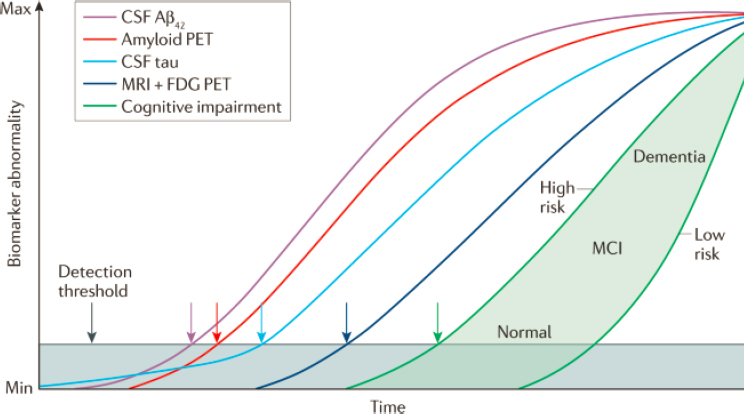

As an example of how biomarkers can be implemented in treatment development, Brady referenced the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association Research Framework for AD, published in 2018 and grounded on the rich dataset of imaging and biofluid biomarkers that have been collected over time (Jack et al., 2018). Also known as the “AT(N) Research Framework,” it defines disease stage according to levels of biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) neuropathology in three categories: “A”–misfolded and aggregated amyloid beta (Aβ), measured with amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) or cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) levels of Aβ; “T”–misfolded and aggregated tau protein, measured with Tau PET or CSF levels of phosphorylated tau (p-tau); and “N”–neurodegeneration or neuronal injury, measured with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or CSF levels of neurofilament light protein (NfL). The framework is based on the model of dynamic biomarkers of AD

developed by Jack and colleagues (Jack et al., 2010, 2013), which relates the clinical and biological features of AD with biomarker-based staging of disease progression, said Brady (see Figure 6-1).

Brady contrasted the progress in developing biomarkers for AD with the paucity of such tools for schizophrenia, one of the top 15 leading causes of disability worldwide, but one for which much less is known about the pathophysiology. Like AD, schizophrenia progresses on a continuum, from early symptoms of psychosis in the prodromal phase through disabling negative and cognitive symptoms during the chronic stages of the disease, said Brady.

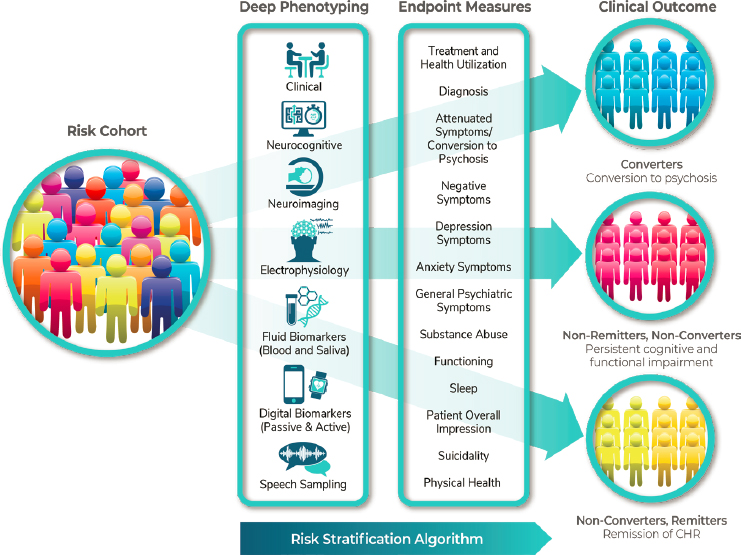

She noted that the Accelerating Medicines Partnership® (AMP®), a precompetitive public–private partnership launched by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health in 2014, initiated a project in schizophrenia in 2020 to provide tools that will enable the selection of enriched patient populations in clinical studies. Brady said AMP-Schizophrenia will conduct a deep phenotyping effort involving imaging, electrophysiology, digital markers, speech, genetics, and others; will assess that very rich data over time; and will also look at endpoint measures (see Figure 6-2). The goal

NOTE: Aβ = amyloid beta; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; FDG = fluorodeoxyglucose; MCI = mild cognitive impairement; PET = positron emission tomography

SOURCES: Presented by Linda Brady, October 6, 2021; Jack et al., 2010.

NOTE: CHR = clinical high risk

SOURCE: Presented by Linda Brady, October 6, 2021.

will be to identify trajectories of biomarkers that will enable stratification of individuals into subgroups according to their predicted risk state.

NOVEL BIOMARKERS CAPTURE THE COMPLEXITY OF MECHANISMS

As delineated by Brady, AD can now be diagnosed biologically through the use of biomarkers that reflect the core pathologies in AD—amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neurodegeneration, said Charlotte Teunissen, professor of neurochemistry at Amsterdam University Medical Centers. Amyloid and tau depositions are measurable using PET as well as in CSF, and these proteins, as well as NfL, are also measurable within blood due to ultrasensitive technologies, said Teunissen, although she cautioned that results from blood and CSF cannot easily be extrapolated from one to

the other because they are different matrices. Nevertheless, she said, “We take our learnings from CSF biomarkers to blood biomarkers to accelerate development.” For example, batch-to-batch inconsistencies were seen in assays for CSF biomarkers and were thought to be due to preanalytic factors such as the plastics used in collection tubes, said Teunissen. So, when blood biomarkers were up and coming, developers knew to avoid similar preanalytic inconsistencies, she said.

Different biomarkers are likely needed for diagnosis, prognosis, stratification, and monitoring of treatment response, said Teunissen, adding that CSF or plasma analysis of p-tau can also help estimate the number of participants needed in a trial. However, to capture the full complexity of the mechanisms involved in AD, additional novel biomarkers are needed, she noted. For example, a proteomics study in individuals with AD across the clinical spectrum measured 708 proteins (Tijms et al., 2020). By applying a statistical methodology called non-negative matrix factorization, Teunissen and colleagues were able to identify three distinct subtypes of the disease characterized by different clusters of proteins: Subtype one, which was associated with an increase in proteins related to neuronal plasticity; subtype two, characterized by an increase in proteins associated with the innate immune system; and subtype three, characterized by increased expression of proteins related to blood–brain barrier damage and immunoglobulin G expression. Teunissen said these subtypes may be useful to predict response to different treatments. For example, the protein BACE1 is clearly increased in subtype 1, but not in subtypes 2 or 3, suggesting that BACE1 inhibitors may be effective only in subtype 1 patients, she said.

Translating technologies such as mass spectrometry to the clinic has proved challenging, said Teunissen. Immunoassays are the methods of choice in the clinic because of their ability to provide large-scale and high-throughput analysis, she said. One novel screening method in development, Olink, uses a technique called proximity extension essay (PEA) to assess more than 900 proteins. This method has provided insight into mechanisms and has also identified panels of proteins that can be used for classification of patients into subgroups. Assays for multiplexing ultrasensitive platforms are also in development, said Teunissen.

Plasma NfL in ALS

Neurofilament (NfL) light protein is what Teunissen called a “cross-disease” biomarker, because as a marker of neural injury, it may be elevated in multiple neurodegenerative disorders. ALS is one of those disorders for which there has been intense interest in developing NfL as a CSF and blood biomarker, not only for participant selection/enrollment, but also to make treatment decisions, monitor treatment response, and possibly ultimately

for use as a surrogate endpoint, said Graham. Indeed, said Graham, many studies have shown that NfL levels are elevated in the blood of ALS patients (Weydt et al., 2016), that baseline levels of NfL correlate with decline (De Schaepdryver et al., 2020), and that plasma levels of NfL predict disease onset, not only in symptomatic patients, but also in asymptomatic individuals who have a genetic mutation that can lead to ALS (Benatar et al., 2019).

Advancing a biomarker such as NfL for use in a clinical trial starts with defining how the biomarker will be used (i.e., the context of use), said Graham. For example, it may be used to make inclusion/exclusion decisions and/or cohort stratification. Once the COU has been determined, the analytical performance, which includes accuracy, precision, test/retest reliability, and robustness, should be evaluated to determine if the test is suitable implementation in the trial, she said.

As Biogen was exploring the possibility of running an ALS clinical trial, they worked with Michael Benatar and the Pre-fALS organization to generate data in the ALS patient population using multiple assays, said Graham. This enabled them to develop a trajectory model that projected the time course from the rise in NfL to phenoconversion and a threshold for entry into the trial. Graham said they looked at multiple assays/platforms before selecting the one they thought would be best, then worked with the selected vendor to advance the analytical performance of the test so they could be confident that an increase in NfL actually reflected a biological change rather than an assay artifact.

This process provided the data they needed to advance NfL as a biomarker for a trial called the Atlas study, which is testing whether the drug Tofersen, a superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) antisense oligonucleotide can delay the emergence of clinically manifest ALS and/or slow the decline in function in presymptomatic individuals with an SOD1 mutation that markedly increases their risk of developing ALS.

Graham added that Biogen is working in other disease areas and with multiple technologies, including ultrasensitive immunoassays and mass spectrometry, to advance the use of fluid biomarkers in blood and CSF. Using proteomics and metabolomics approaches such as the Olink technology, mentioned by Teunissen, along with a new technology developed by Seer, they hope to develop biomarker signatures to use for participant selection in trials for diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, she said. She added that once they have identified a protein signature, they will follow up with the development of robust targeted immunoassays or even targeted mass spectrometry.

Ultimately, the goal is to design panels that capture the entire pathology, said Teunissen, adding that the ideal number of markers on a panel should not be too large because of the increased cost and analysis time. New multiplexing technologies are needed, she said.

MULTIMODAL ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE-BASED ANALYSIS OF DISEASE PROGRESSION

Biomarkers are most reliable when there is a close mechanistic link between what is measured and the disease process, and when biomarkers are identified from large and representative patient populations, said Ernest Fraenkel, professor of biological engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Because animal models may not capture the full disease biology nor represent diverse patient populations, Fraenkel said he and many others have switched to using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). From iPSCs, one can derive motor neurons from people with ALS for a diverse set of molecular assays. Working with Answer ALS,1 Fraenkel and colleagues are assembling 1,200 different iPSC lines, including 1,000 from ALS patients and 200 from controls. From these iPSC lines, they are deriving whole genomes, motor neurons, and RNA, epigenomic, and proteomic data, said Fraenkel. Whether those multiple datasets will enable them to identify signals is an unanswered question, said Fraenkel, but he expressed optimism that because these are matched datasets, they may provide the power to do so. The proof will be if molecular data from iPSC-derived motor neurons are able to predict something true in patients, he said.

Fraenkel noted that to address the challenge of recruiting representative populations, they have partnered with patient advocacy organizations around the world, including Everything ALS,2 which has rapidly recruited patients for a digital biomarker study from 48 of 50 states. “It’s amazing to see some of the things that you can accomplish when you step out of the clinic and have patient advocates and patients try to find participants,” said Fraenkel. Most importantly, he said, is that affirmation from patient communities and patient advocates helps build trust with potential clinical trial participants. Having them participate in everything from recruitment to trial design is a game changer, said Fraenkel. “It’s really thinking out of the box of what a clinical trial is.”

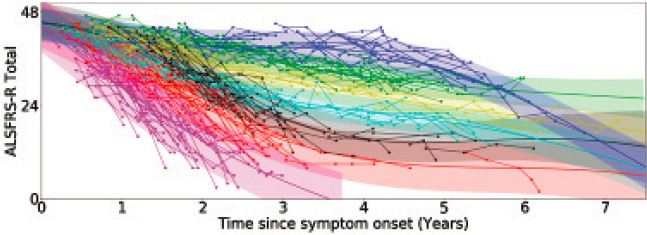

Fraenkel and colleagues have teamed up with a group at IBM to tackle the challenge of stratifying participants into subgroups based on disease trajectory. The most common way of assessing progression in clinical trials is through the use of the revised ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS), a questionnaire that asks patients to rate 12 aspects of their physical function. The problem with this and similar rating scales is that answers are highly subjective and may vary from one day to the next, said Fraenkel. His team takes a broader approach, trying to gather every piece of data they can,

___________________

1 To learn more about Answer ALS, see https://www.answerals.org (accessed November 27, 2021).

2 To learn more about Everything ALS, see https://www.everythingals.org (accessed November 27, 2021).

whether from iPSCs, genomics, or behavioral studies. “We don’t know in advance what we’re going to see,” he said. He added that artificial intelligence (AI) is especially adept at finding combinations of signals that help distinguish one subgroup from another, especially when there is little prior knowledge about what differentiates the groups.

Divya Ramamoorthy, a graduate student in Fraenkel’s lab, worked with IBM researchers to develop an AI model using actual data from the Answer ALS study to find a set of typical disease trajectories in patients. As shown in Figure 6-3, the model identified both relatively linear and highly nonlinear trajectories, said Fraenkel. “Understanding the difference between a linear trajectory and the actual trajectory can have enormous implications for clinical trials,” he said. In a drug trial, modeling non-linear baseline data with linear approaches can lead to either over- or under-estimation of what would be expected to happen in the absence of a drug, he said.

Now that they have a good way of identifying fast and slow progressors, they are investigating correlations between molecular and clinical measurements, said Fraenkel. He added that they also plan to investigate the probability that particular mutations are associated with different trajectories. He argued that ALS, like AD and Parkinson’s, is probably not a single disease, but a group of diseases that clinically look very similar.

Fraenkel and others are also applying AI approaches to digital data (information that is captured through computer-aided monitoring of behaviors, including speech and motion). For example, he said, a team from IBM has shown that while individual signals are only weakly predictive, combining clinical and behavioral signals from acoustic, fine motor, and cognitive tasks is highly predictive of ALSFRS-R score. Everything ALS has launched a study collecting data on a number of aspects of speech using

SOURCE: Presented by Ernest Fraenkel, October 6, 2021.

a web-based platform called Modality, where a patient interacts with an avatar that takes them through a series of exercises and captures video and voice data. Preliminary results from this study suggest that these measures can distinguish patients from controls even before the onset of bulbar symptoms, said Fraenkel. The Answer ALS and Everything ALS studies are also investigating the potential of using speech signals such as word choice during a picture description task as biomarkers of disease progression, he said. Fraenkel added that he thinks clinical rating scales will improve if they incorporate digital approaches.

TOWARD PRECISION MEDICINE IN MENTAL HEALTH FROM A LIFE-SPAN PERSPECTIVE

Aiming to tame some of the complexity and heterogeneity in neuropsychiatric conditions, Nikos Koutsouleris, chair in precision psychiatry at King’s College London and Ludwig-Maximilian-University, Munich, uses machine-learning approaches with different data domains and analytical methods to try to extract meaningful rules that can be applied in individual cases.

For example, in patients with schizophrenia, the disease course varies substantially, said Koutsouleris. Some patients have episodic courses with waxing and waning symptoms, while others have an insidious early-onset course from which they may never recover, he said. In 1980, Huber and colleagues showed, from following a group of 502 first episode psychosis patients for over 20 years, that about a quarter had a benign course, about a half had an intermediate course, and another quarter had progressive deterioration and more adverse outcomes (Huber et al., 1980). A neuropathological explanation for rapid deterioration was suggested a century ago and has been supported by more recent imaging studies in the brains of people with this extreme subtype of schizophrenia, said Koutsouleris.

Koutsouleris and colleagues have used a comparative neuroscience approach and machine learning to look at the similarity space across different data domains in schizophrenia and behavioral variant frontotemporal degeneration (bvFTD), a condition with some similar clinical and behavioral features. Using neuroanatomical data from bvFTD patients, they trained a classifier that separate bvFTD patients from healthy individuals with high accuracy, and then applied that classifier at the individual patient level to interrogate clinical data for overlaps. They found that in patients with schizophrenia, the bvFTD pattern was predicted by features such as lack of judgment, lack of spontaneity in conversation, high body mass index, and accelerated aging.

Interestingly, when they trained the machine using a schizophrenia classifier and applied it to patients with bvFTD, they found that bvFTD

patients who expressed the schizophrenia pattern had a high likelihood of carrying the C9orf72 mutation and were more likely to develop psychiatric phenotypes, especially psychosis, said Koutsouleris.

Koutsouleris added that in a study from the PRONIA consortium,3 single data domains, whether from genetics, proteomics, neuroimaging, or clinical readouts, yielded about the same prediction performance. Where substantial gains were seen, he said, was when the different data domains were combined. “So there may not be a simple solution, unfortunately, with one biomarker that will explain the whole variance, unless we find meaningful subtypes that have more circumscribed disease pathology,” he said.

However, there are challenges in integrating genetic and non-genetic factors into a prediction model, said Koutsouleris. The sheer dimensionality of genetic data can overshadow datasets with fewer dimensions, such as clinical or neurocognitive readouts, he said. One solution is to organize genetic data into expression pathways, which are of a much lower dimensionality, and then use those for prediction alongside other data, said Koutsouleris. Fraenkel added that to reduce the high dimensionality of digital data, one strategy is to turn raw data into something meaningful, such as groups of genes that are known to function together. The challenge then, said Fraenkel, is to prove that such meaningful readouts provide better measures of disease progression than traditional measures.

A REGULATORY PERSPECTIVE ON BIOMARKERS

In clinical practice for psychiatric indications, biomarkers have been used for monitoring and improving drug safety and they have potential to play expanded roles in several areas relevant to drug approvals by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said Pamela Horn, clinical team leader in the Division of Psychiatry within the Office of New Drugs at FDA. For example, they can help refine study populations; improve diagnostic accuracy; and improve precision in measuring treatment effects by identifying and accounting for patient characteristics that interact with the effect of the drug or that influence the natural history of the condition being studied.

The different categories of biomarkers may all be useful, said Horn:

- Diagnostic biomarkers can confirm a diagnosis as part of entry criteria for the study.

- Prognostic biomarkers that suggest the likelihood of a particular outcome based on different patient characteristics may be used to

___________________

3 To learn more about the Personalized Prognostic Tools for Early Psychosis Management (PRONIA) Consortium, see https://www.pronia.eu (accessed December 1, 2021).

- enrich or stratify a clinical trial population, or may be used as a covariate in the analysis of study results.

- Predictive biomarkers may predict treatment effect and thus can be used to enrich study populations or in the analysis of study results.

- Pharmacodynamic or response biomarkers have the potential to be used as a surrogate for how a participant feels or functions.

- Monitoring biomarkers, such as urine drug screens in the treatment of substance use disorders, can be used to assess the status of the treatment response.

- Safety monitoring biomarkers can identify adverse events in study participants.

Sponsors may interact with FDA about using biomarkers in drug trials either as a component of the drug approval process or through the biomarker qualification program,4 both of which offer advantages and disadvantages, said Horn. A qualified biomarker and assay that could be applied in multiple conditions or for multiple treatments could move the field much more quickly than a biomarker that is only fit-for-purpose for a specific drug development program, she said. However, Graham noted that sponsors must weigh the value of pursuing qualification, balancing the benefit of expediting the approval process for a specific drug with the benefits to the field, adding that the sponsor first must determine whether they have enough data to support qualification.

In either case, the sponsor must clearly state the context of use, said Horn. If a biomarker is proposed as part of the clinical drug approval process, FDA will provide advice throughout the process regarding what data will be needed. If the qualification path is chosen, the first step is submission of a letter of intent, which FDA evaluates and decides whether the qualification project will be accepted into the program, said Horn. If accepted, sponsors prepare a qualification plan that describes the work that will be done to generate the data needed to approve the biomarker for the proposed context of use. After collecting the data, sponsors submit a full qualification package for FDA review. If FDA finds that the biomarker can be relied upon to have a specific interpretation and application in drug development for the proposed context of use, they will recommend qualification.

Horn provided two examples of biomarkers for autism spectrum disorder that have been accepted into the qualification program. The context of use for both of these biomarkers is to enrich the study populations by reducing the heterogeneity of diagnosis. Both measure response to seeing human faces, one by measuring the latency and peak amplitude of a brain

___________________

4 For more information, see https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-development-tool-ddtqualification-programs/biomarker-qualification-program (accessed January 3, 2022).

waveform measured by electroencephalogram and the other by measuring the time spent gazing at human faces with eye tracking. Horn noted that in accepting these proposals into the program, FDA recommended additional work to characterize how subgroups or strata based on these biomarkers clinically differ.

Horn concluded that there are many opportunities to integrate biomarkers in neurological and psychiatric drug trials, both in the drug approval process and through the biomarker qualification program. The use of biomarkers in study population selection, stratification randomization, or statistical analysis can be particularly helpful to advance the field by improving detection of a treatment effect, she added.