The State of Anti-Black Racism in the United States: Reflections and Solutions from the Roundtable on Black Men and Black Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 2 Anti-Racism Plans in Academic Medicine

Camara Phyllis Jones, M.D., M.P.H., Ph.D. (University of California, San Francisco), moderated the first session. She provided a context for racism and antiracism. Presentations followed about antiracism efforts at three medical schools and two organizations that play a key role in medical school education. They were made by representatives of Charles R. Drew University (CDU) of Medicine and Science, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, as well as the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Medical Association.

RACISM, ANTI-RACISM, AND ACTION

Dr. Jones began by noting the trajectory of her and others’ work in medical education beginning with shifting from “race,” which she said she explicitly places within quotation marks, to racism by documenting, specifying, and acknowledging racism-associated differences and health outcomes (Jones, 2014). She identified and elaborated upon three related antiracism tasks: naming racism, asking how racism is operating in a given context, and organizing and strategizing to act (Jones, 2018).

Dr. Jones suggested looking at a given context to investigate how racism is operating by identifying mechanisms behind different aspects of decision-making (Jones, 2003 and Jones, 2004):

- Structures: the who, what, when, and where of decision-making

- Policies: the written how of decision-making1

- Practices and norms: the unwritten how2

- Values: the why

Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science

Bita Amani, Ph.D., M.H.S., introduced the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, which she said embodies the issues raised by Dr. Jones. CDU was founded after the Watts Uprising in Los Angeles in 1965 and the subsequent McCone Commission (Governor’s Commission, 1965).

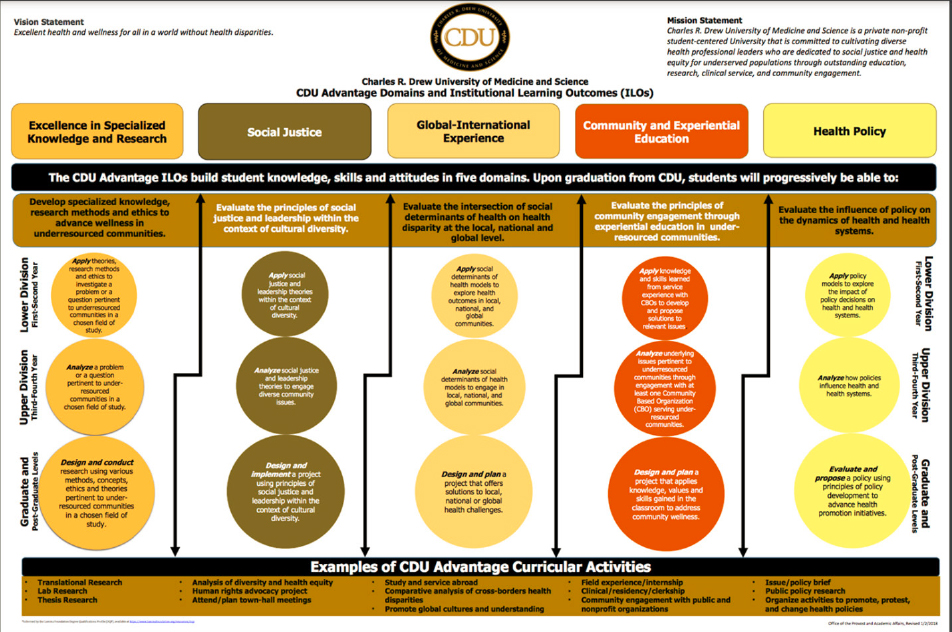

CDU has five “advantage domains and institutional outcomes”: excellence in specialized knowledge and research, social justice, global international experience, community and experiential education, and health policy (see Figure 2-1). Dr. Amani singled out social justice and community and experiential education as integral to CDU’s anti-Black racism work. “If we are going to be talking about disparities, race, and racism, we also need to be talking about what is needed to change anti-Black racism, which leads us to social justice,” she said. Social justice is embedded into the curriculum, as is applying theories of social justice to real-world change.

___________________

1 Policies refers to the written and formalized processes and procedures governing decision-making within a given organization.

2 Practices and norms refers to the informal and unwritten “rules” that govern processes and procedures for decision-making within a given organization. While practices and norms may not be codified, they can still serve to sediment inequitable practices that have implications for racial inequities.

SOURCE: Bita Amani, Workshop Presentation, December 6, 2021.

Janae Asali Oliver, M.P.H. (Charles R. Drew University), shared several other examples of CDU’s community engagement and social justice work as a CDU graduate and community health manager. She offered these questions to ponder in addressing anti-Black racism:

- What systems, structures, policies, and practices am I challenging that perpetuate anti-Black racism?

- How am I ensuring an anti-Black racist agenda is core to the work that I do every day?

- What does it mean for me as an individual in an institution to be attached to solutions that reflect Black health promotion and intervention?

- Am I only really invested in talking about or researching Black problems?

- What does it mean to prioritize Black populations, communities, and geographies with the highest needs?

- What does real investment in an anti-Black racist agenda look like?

- What risks am I willing to take and be accountable for?

- What are the real and artificial barriers that get in the way?

ADDRESSING ANTI-BLACK RACISM: ACTION AND REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Consuelo H. Wilkins, M.D., M.S.C.I., and Selena McCoy Carpenter, M.Ed., shared how Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) is confronting racial inequities. A statement issued by VUMC CEO Jeffrey R. Balser, M.D., Ph.D., affirmed the institution’s commitment to dismantle racism and identified five initial steps that included antiracism training for all senior leaders, examination of policies and practices for immediate action, and identification of gaps in curriculum. In addition, a Racial Equity Task Force was created to provide longer-term recommendations.

Ms. Carpenter described the work of the task force, which was charged with identifying barriers to racial equity and recommending actions to Dr. Balser by the end of 2020. The three co-chairs were the director of nurse safety and well-being, a fourth-year medical student, and a professor of pediatrics and medicine. According to Ms. Carpenter, who helped staff the project, this co-leadership corresponds with the staff, students, and

faculty that make up VUMC. Stakeholders not normally consulted or brought into hospital decision-making were intentionally sought out. More than 100 people from 38 departments first met in September 2020. They formed seven work groups that met through the fall of 2020 to prepare and submit recommendations. A variety of data collection techniques were used, including individual interviews, group meetings, listening sessions, and surveys.

Dr. Wilkins noted that the seven work groups made 68 specific recommendations with 152 sub-recommendations that fell within 8 thematic areas:

- Establish infrastructure to combat structural racism

- Cultivate an inclusive environment, free of racism

- Equitably promote economic and career advancement

- Recruit, retain, and promote a racially and ethnically diverse workforce

- Educate and train a workforce that seeks racial equity

- Recruit and retain students and trainees from racial/ethnic groups historically excluded

- Cultivate racial equity in research and conduct research to address health inequities

- Equitably deliver health care and eliminate racialized medicine

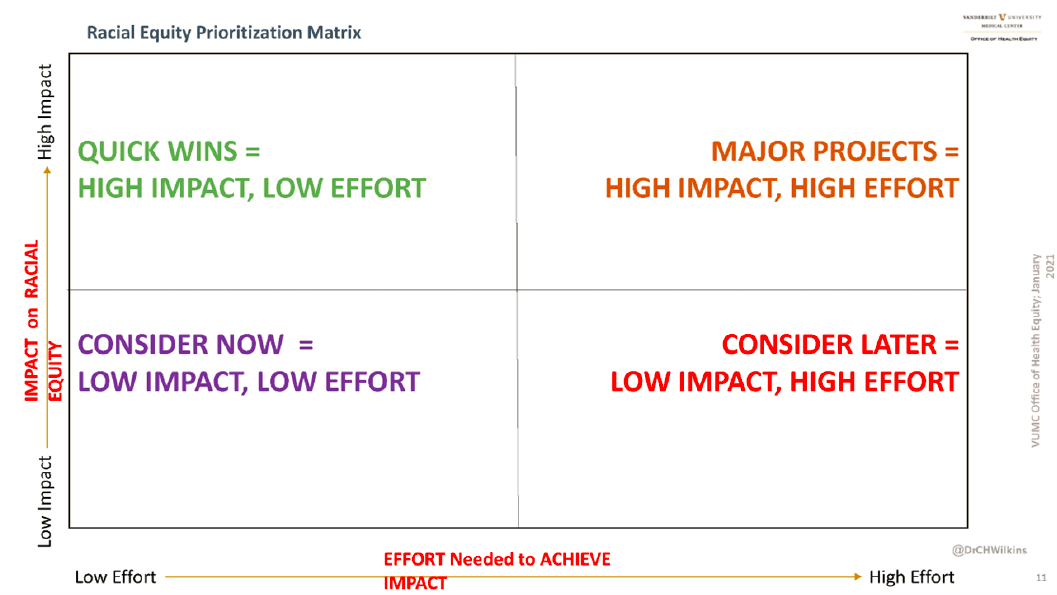

Dr. Wilkins noted that implementing the recommendations, as well as “big ideas” that came from senior leadership during their antiracism training, was the focus for 2021. Each identified priority has been expanded upon to (1) set goals, (2) determine the resources needed, (3) determine who is accountable and responsible, and (4) propose a time line. The implementation plan was due to Dr. Balser and the VUMC dean on December 31, 2021. Dr. Wilkins shared a matrix created to prioritize the recommendations to balance the effect on racial equity and effort needed to achieve the desired results (see Figure 2-2).

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

David Muller, M.D., said that even though Mount Sinai administration initially resisted student activism that began with “die-ins” in 2014, it came to embrace it. It has committed itself to deeply developing an understanding of the aspects of decision-making identified by Dr. Jones (see

SOURCE: Consuelo Wilkins, Workshop Presentation, December 6, 2021.

above) related to structures, policies, practices, norms, and values, or what he termed “the culture of America and of academic medicine.”

With the assistance of Leona Hess, Ph.D., Mount Sinai developed a mission to become a health system and health professions school with the most diverse workforce, providing health care and education that is free of racism and bias. He explained the Mount Sinai Racism and Bias Initiative, which was developed to transform the culture:

A framework of transformational change assumes that the future state is radically different from the current state and is initially unknown. It is led by a coalition of multiple stakeholders and uses systems thinking. . . . We stopped focusing solely on solving problems, completing tasks, and reacting to crises. We articulated both to ourselves and to our students the long arc of this work, and we developed the courage over the course of time to be vulnerable, to trust, and to course-correct.

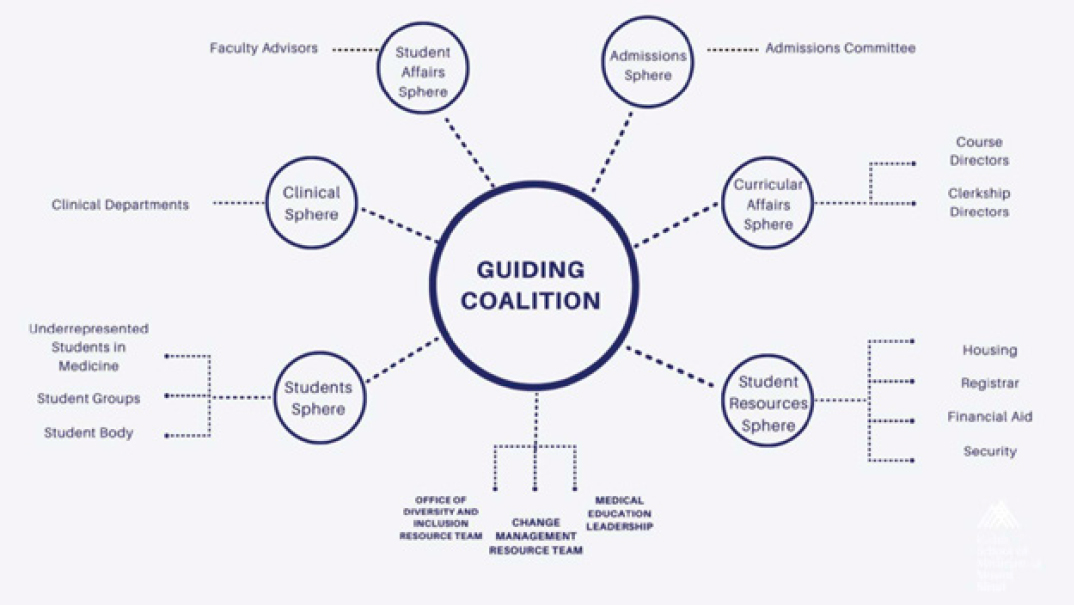

Related to transforming medical education, a guiding coalition was formed that represents all constituents, including those in the student, clinical, student affairs, admissions, curricular affairs, and student resources spheres (see Figure 2-3). The school withdrew from the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society, based on student-led activism that pointed out the inequity in which medical schools evaluate, grade, and offer honors to medical students. The Center for Anti-racism in Practice was formed, and beginning in 2021, closely mentored, stipend-funded fellowships are available for students devoting large amounts of time to anti-racism work.

After Dr. Hess and colleagues (2020) published a paper in Academic Medicine about the work, the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation approached them about scaling it to other medical schools. A program called Anti-Racist Transformation in Medical Education, or ART in Med Ed, was created to build capacity, foster a community of practice, and discover how to make antiracism in education replicable and scalable.3 As an indication of the demand to join the community of practice, Jennifer Dias, M.D. candidate, Icahn School of Medicine, noted applications to participate were received from 48 medical schools with a range of characteristics. With scalability and replicability in mind, 11 medical schools with diverse geographic distribu-

___________________

3 For more information, see https://icahn.mssm.edu/education/medical/anti-racist-transformation.

SOURCE: David Muller, Workshop Presentation, December 6, 2021.

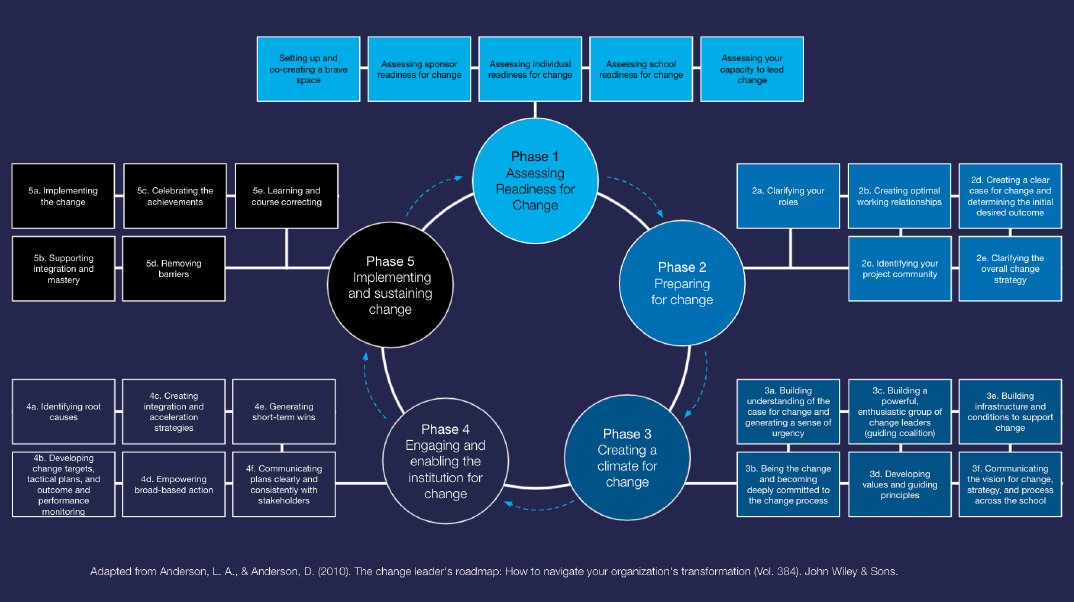

tion and demographics were selected.4 The change strategy embodies five key phases (see Figure 2-4).

The first phase focuses on an assessment of readiness for change. The second phase prepares people for change through a number of exercises, followed by creating a climate for change, engaging and enabling the institution for change, and implementing and sustaining change. Each phase is intended to last 2 to 3 months.

Graduate Medical Education

Bonnie Simpson Mason, M.D., F.A.A.O.S. (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education [ACGME]), and Derek J. Robinson, M.D., M.B.A., F.A.C.E.P., C.H.C.Q.M. (Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois [BCBSIL]), spoke about anti-racism actions in graduate medical education (GME). As context, Dr. Mason reminded participants that the total number of medical school graduates increased from about 23,000 in 2004–2005 to about 30,350 in 2018–2019. Within that total, the percentage of Blacks in GME remained static at about 4.9 percent.

Further research by ACGME showed a significant leak in the pipeline of Black residents: Black residents were dismissed at a rate of about 14 percent in 2004–2005, peaking to a high of 20.9 percent in 2015–2016, and about 11.9 percent in 2018–2019. The dismissal across specialties also shows a disproportionate percentage of Blacks. As an example, 5.1 percent of all surgery residents were Black in 2015–2016, but they represented 25.8 percent of the surgical residents who were dismissed. Similarly, Black anesthesiology residents were 10 times more likely be dismissed than white anesthesiology residents in 2015–2016, 12 times more likely in internal medicine, and 31 times more likely in orthopedic surgery.

Dr. Mason stated that the differential odds of being dismissed between white residents and Black residents continues. She clarified the need to consider the physician “pathway” rather than “pipeline” problem. Not enough underrepresented minorities reach GME training, and once they

___________________

4 The community of practice now consists of the University of Missouri School of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan College of Medicine, University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, University of Minnesota Medical School, University of Arizona College of Medicine–Phoenix, Ohio State University College of Medicine, and East Carolina University Brody School of Medicine.

SOURCE: Jennifer Dias, Workshop Presentation, December 6, 2021, adapted from Anderson and Anderson (2010).

do, GME providers believe they are “more of a recipient of the product than a driver of the fountainhead of the pipeline.” In response, the ACGME’s Common Program Requirements, which all 11,800 programs are required to adhere to, contains language related to recruitment and retention of diverse populations.5

Dr. Robinson related that BCBSIL hosted its first physician diversity roundtable in 2019. Representatives from academic medical centers, teaching hospitals, nonprofits, ACGME, and the AMA met to talk about the data regarding the underrepresentation of Blacks, Latinos, and American Indians in the health-care workforce in Illinois, and how BCBSIL’s role as a payor could catalyze improvement and outcomes. In early 2020, the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois Institute for Physician Diversity was launched to become an enduring vehicle in ensuring the workforce becomes more reflective of the communities served by health-care providers across the state. In 2021, BCBSIL launched the Health Equity Hospital Quality Incentive Pilot Program,6 which provides $100 million in incentives to improve equity in clinical care delivery and diversity in the physician workforce.

This work set the stage for the partnership with the ACGME, he continued. As the only insurance company in the nation engaged in equity matters to date, “we wanted to provide our partners with tools and resources to help them with the know-how to do this very challenging work,” Dr. Robinson explained. Rather than look at the entire ACGME program at a teaching hospital, they take a more granular look and analysis of the diversity within each specialty GME program. One of the most important things has been engagement of C-suite leaders in organizations and in contracting, so that “in a contracting relationship, we are talking about equity in clinical care and a workforce that reflects the communities that are served,” he said.

American Medical Association

Aletha Maybank, M.D., M.P.H. (American Medical Association), and Rohan Khazanchi, M.D. candidate and M.P.H. (University of Nebraska Medical Center; AMA Council on Medical Education), concluded the series of presentations in this session to speak about the AMA’s effort to

___________________

5 For background on the Common Program Requirements, see https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Common-Program-Requirements.

6 For background on the Health Equity Hospital Quality Incentive Pilot Program, see bcbsil.com/newsroom/category/collaborative-care/illinois-health-equity-pilot-health-disparities.

embed racial justice and advance health equity. Dr. Maybank began with an acknowledgment of land and labor: land stolen from Indigenous peoples for thousands of years and labor extracted from people of African descent for more than 400 years.

No set of commitments to antiracism can begin without an honest assessment of an institution’s own history, Dr. Maybank stated, and she reported on past racist policies, culture, and practices of the AMA from its early years following the Civil War through the 20th century. AMA issued a formal apology for this history in 2008 through a statement by AMA Immediate Past President Ronald M. Davis, M.D. (Davis, 2008). In 2018, the AMA’s Health Equity Task Force presented a report to the association’s House of Delegates with a Plan for Continued Progress toward Health Equity.7 It consisted of a definition of health equity, an initial framework that outlined AMA’s role in addressing health-care inequities, and recommendations for what became, in 2019, the Center for Health Equity led by Dr. Maybank as AMA’s first chief health equity officer.8

Mr. Khazanchi reported on a trainee coalition, of which he is a part, which developed a set of antiracism policies adopted by the House of Delegates in November 2020. The policies seek to name and intervene to fight racism as a public health threat; combat racial essentialism in medicine by recognizing race as a social, not a biological, construct; and support the elimination of race as a proxy for ancestry, genetics, and biology in medical education, research, and clinical practice. He underscored that this work had been carried out by a movement of trainees over many years. While he expressed pride that the statements have been adopted and are now widely used throughout AMA and other organizations, he also stated:

I want to be clear that passing these policies does not mean that our trainee coalition has fulfilled our vision. We view this as an opportunity for the AMA to move beyond formal declarations. . . . Our goal is not achieved when the policies are updated. Our goal will be achieved when actionable and measurable targets for intervention are met.

___________________

7 For more information on the Plan for Continued Progress toward Health Equity, see ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/public/hod/a18-bot33.pdf.

8 For more information the NYC Department of Health Centers for Health Equity, see https://www.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/neighborhood-health/neighborhood-health-action-centers.page.

Dr. Maybank continued the discussion thread and explained that, in May 2021, AMA released its Organizational Strategic Plan to Embed Racial Justice and Advance Health Equity (AMA, 2021). She concurred with the points made by other presenters about the importance of internal work to change culture and practice. She added an essential but often unconsidered need is to create psychological space within institutions for those fighting racism, which can be exhausting and traumatic. Building alliances and sharing power with groups who have been historically marginalized and minoritized is also critical, rather than a top-down approach, she added.

Looking at the past, Mr. Khazanchi discussed the AMA Council on Medical Education’s role in the development of the Flexner Report and the harm that the report caused, including irreversibly changing the composition of the medical workforce (see Flexner, 1910). The council’s 2021 report focused on pathways to increase medical workforce diversity and did not ignore this history, he said. A section of the report explicitly recognizes the harm caused by the Flexner Report to schools, doctors, and patients; sets targets to support the creation and sustainability of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Minority Serving Institutions, and Texas Christian University–affiliated medical schools; and calls for an external study of 21st century medical education.

In concluding the session, Dr. Jones commented, “We have to look and name our history, and we need to stand up and speak up with courage and directness if we want to push for change.” The Flexner Report did damage for 100 years that will take 100 years to change, she added. Drawing on the analogy of a team working together during a relay race, “We are passing the baton to the next generation, but there needs to be barrels of batons.”

REFERENCES

AMA (American Medical Association). 2021. The AMA’s Strategic Plan to Embed Racial Justice and Advance Health Equity. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership/ama-s-strategic-plan-embed-racial-justice-and-advance-health-equity.

Anderson, L. S., and D. Anderson. 2010. The Change Leader’s Roadmap: How to Navigate Your Organization’s Transformation. San Francisco: John Wiley.

Davis, R. 2008. Achieving racial harmony for the benefit of patients and communities: Contrition, reconciliation, and collaboration. JAMA 300(3): 323–325.

Flexner, A. 1910. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Bulletin Number Four (1910). New York: Carnegie Foundation. http://archive.carnegiefoundation.org/publications/pdfs/elibrary/Carnegie_Flexner_Report.pdf.

Governor’s Commission on the Los Angeles Riots. 1965. Violence in the City—An End or a Beginning? A Report by the Governor’s Commission on the Los Angeles Riots, 1965. Chaired by John A. McCone. Los Angeles: University of Southern California. https://digitallibrary.usc.edu/CS.aspx?VP3=DamView&VBID=2A3BXZMFMETM&SM-LS=1&RW=1925&RH=1244.

Hess, L., A-G. Palermo, and D. Muller. 2020. Addressing and undoing racism and bias in the medical school learning and work environment. Academic Medicine 85(125): S44–S50.

Jones, C. P. 2003. Confronting institutionalized racism. Phylon 50(1–2): 7–22.

Jones, C. P. 2014. Systems of power, axes of inequity: Parallels, interactions, braiding the strands. Medical Care 52(10, Supp. 3): S71–75. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000216.

Jones, C. P. 2018. Toward the science and practice of anti-racism: Launching a national campaign against racism. Ethnicity and Disease 28(Supp. 1): 231–234.

Jones, C. P., B. I. Truman, L. D. Elam-Evans, C. A. Jones, C. Y. Jones, R. Jiles, S. F. Rumisha, and G. S. Perry. 2008. Using “socially assigned race” to probe White advantages in health status. Ethnicity and Disease 18(4): 496–504.

Wilkins, C. H., M. Williams, K. Kaur, and M. R. DeBaun. 2021. Academic medicine’s journey toward racial equity must be grounded in history: Recommendations for becoming an antiracist academic medical center. Academic Medicine 96(11) 1507–1512.

This page intentionally left blank.