The State of Anti-Black Racism in the United States: Reflections and Solutions from the Roundtable on Black Men and Black Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 4 Increasing Awareness of Anti-Black Racism in SEM Research and Education

George Q. Daley, M.D., Ph.D. (Harvard Medical School [HMS]), introduced this session by explaining its premise: Public engagement to advance antiracism efforts in SEM must start with outreach to scientists, engineers, and physicians as key stakeholders. He said:

For scientists and engineers, we must increase awareness of the pervasiveness of bias in research . . . and we have to enlist scientists and engineers in changing the culture of research. We have to develop ways to advance diversity in the scientific workforce, and we have to promote equity and inclusion, foster career advancement, and ultimately improve research productivity, which we know follows from capturing a broader range of expertise and perspectives in the scientific process.

Given the intimate role that physicians play in fostering health and well-being and the trust that most patients have in their doctors, he continued, physicians must be prepared to become agents of change and ambassadors of antiracism. This starts by evaluating and changing the medical school curriculum.

Andrea Reid, M.D., M.P.H. (Harvard Medical School), spoke about Harvard Medical School’s efforts to tackle racism. She was followed by presentations by Gilda Barabino, Ph.D. (Olin College of Engineering), about the influence of racial bias on research and by Cato Laurencin, M.D., Ph.D. (University of Connecticut), who proposed explicitly merging antiracism and learning with the more familiar construct of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Cora Marrett, Ph.D. (University of Wisconsin–Madison), served as discussant.

TACKLING RACISM IN MEDICAL EDUCATION

A Harvard Medical School graduate and former faculty member, Dr. Reid returned to HMS as an associate dean in July 2020. One of her first responsibilities has been to co-chair the Harvard Medical School Task Force to Address Racism, and she reported on the task force process and recommendations. Responding to the disparities revealed by COVID-19 and by the murder of George Floyd and other Black men and women and other men and women of color, HMS had to do its own reckoning, Dr. Reid said. The discussions revealed such issues as treating race as biology rather than a social construct; attributing health-care disparities to race and not racism; toleration of disparate treatment of students, patients, and physicians of color; lack of recognition of the toll of racism; lack of belonging; limited faculty representation; and limited faculty development about racism. The task force was commissioned by the HMS Education Policy and Curriculum Committee, which is the governing structure of the school.

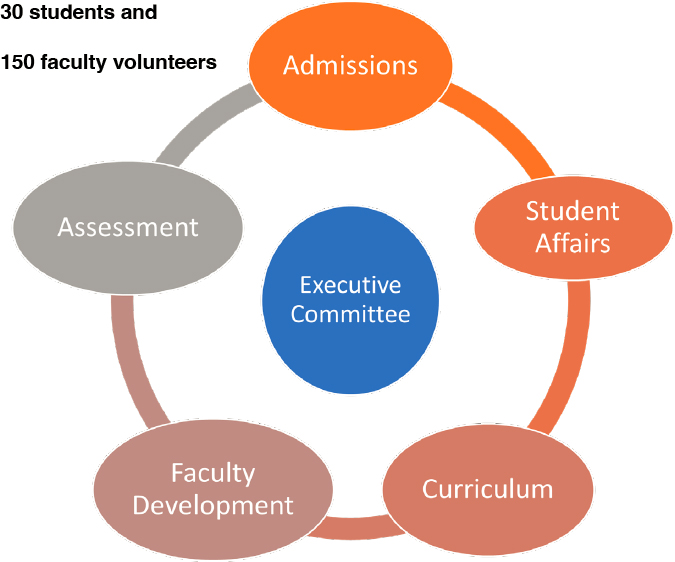

Dr. Reid listed the objectives of the task force: perform an in-depth internal scan, identify areas where racism is embedded in experience, identify areas to incorporate antiracism education, make concrete recommendations and priorities to combat racism, and develop a monitoring process and reporting structure to address racism and discrimination in real time. The task force executive committee decided to meet these objectives by looking at five related areas (see Figure 4-1).

Most important was to populate each area with people from across the medical school, not just faculty. In total, 150 faculty volunteers and 30 students participated in the committees. Each decided how it would organize its work but was told “no sacred spaces” existed. Dr. Reid noted that 10 overarching priorities spanned across all the committees (see Box 4-1).

Dr. Reid provided some examples of more specific recommendations. In admissions, identify strategies to increase underrepresented-in-medicine (UIM) faculty in admissions work and develop a recruitment budget. In faculty development, require high-quality faculty development programming and improve recruitment, retention, promotion, and leadership of UIM faculty. In curriculum, create a database of health equity and antiracism experts and address racism, bias, and equity in all courses and workshops. In student affairs, ensure a diverse faculty advising students. In assessment, review student assessments for racial bias and develop antiracism competencies and assessments for students and faculty.

SOURCE: Andrea Reid, Workshop Presentation, December 6, 2021.

Moving from recommendations to implementation is the hard work, Dr. Reid commented. The Program in Medical Education (PME) saw and began to act on the task force recommendations in April 2021. Staff (1.5 full-time equivalent) were hired for antiracism and recruitment activities. For the first time, everyone involved in admissions participated in antiracism and implicit bias training. Dr. Reid stressed the importance of breaking down silos and collaboration with the HMS Office for Diversity Inclusion and Community Partnership so that antiracism efforts are embedded and not considered an add-on. A subcommittee with members across the organization will carry out the work with dedicated faculty in each PME office, to include staff, faculty, content experts, students, and others.

Dr. Reid emphasized that the work is just getting started and questions remain. For example, who will do the work? How will we incorporate community voices? How do we avoid the minority tax? How do we assess effectiveness? How do we sustain commitment and action? The report provides a blueprint, but metrics are needed to gauge effectiveness. Echoing

other presenters, she observed that everyone is galvanized, but it is necessary to figure out how to sustain the passion. Dr. Reid concluded with a quote from author James Baldwin: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” She said that HMS, the PME, the task force, and the subcommittee have provided a way to “face who we are, then develop the systems to change.” (Buckley, 2021)

THE IMPLICATIONS OF RACIAL BIAS IN RESEARCH

Dr. Barabino previewed a talk she prepared for one of the groups of stakeholders whom Dr. Daley mentioned in his introductory remarks—-

members of the American Society of Hematology.1 She discussed what is meant by racial bias, the implications of racial biases in research and study design, and strategies to avoid racial biases and improve research and study design. She noted while she developed her remarks for the hematology community, they apply to biomedical research more broadly.

As defined in the Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development, “racial bias is a personal and sometimes unreasoned judgment made solely on an individual’s race,” Dr. Barabino began (Williams, 2011). She suggested better defining it by delving more deeply into how it manifests. She pointed out that racial bias is a product of racism and is baked into society, algorithms, policies and practices, the health-care system, and more. Racial bias typically takes the form of prejudice, stereotypes, or discrimination, and it can be consciously or unconsciously held.

Studies show that racial biases perpetuate health inequities, Dr. Barabino continued. For example, researchers found that racism in decision-making algorithms—algorithms that are created by developer teams that have a lack of diversity—have compromised health-care management for racially minoritized groups. Compared with equally sick white patients, Black patients are less likely to be referred for more complex medical needs (Obermeyer et al., 2019). In another study comparing pulse oximeter measurements, Black patients were nearly 3 times as likely to have hypoxia that went undetected by pulse oximetry (Sjoding et al., 2020). Dr. Barabino also pointed to an enduring practice of underestimating and undertreating pain in Black Americans, stemming from historic injustice and false beliefs about biological differences between Blacks and whites in dealing with pain (Hoffman et al., 2016). Dr. Barabino continued:

Racial biases influence which studies are undertaken, which populations are served and who is carrying them out, and how questions are asked and framed. The “what, how, and who” of studies can lead to inappropriate and improperly framed questions and limit the results. Chief among them is mistrust among racially minoritized and marginalized groups, leading to limited participation, compromised treatments, and poorer health outcomes.

Dr. Barabino pointed out that white patients make up the vast majority of clinical trial participants. As an example of the gap, Blacks are 13 percent

___________________

1 Dr. Barabino was invited to speak at the 63rd annual meeting of the society, December 11–14, 2021, during a Special Scientific Session on Race and Science.

of the population, have the highest death and shortest survival rates from cancer, but constitute only 3 percent of clinical trials for cancer drugs. Physicians and investigators serve as gatekeepers to research, and racial concordance between them and patients can enhance potential participation, yet the dearth of Black physicians, scientists, engineers, and faculty in these disciplines limits participation in research.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) provides an example of a condition shaped by the politics of race and health, Dr. Barabino said. SCD is understudied and underfunded, SCD pain is often discounted and undertreated, and physicians trained and willing to treat it are limited. Individuals carry the dual burden of the disease and of race/racism. Cystic fibrosis receives 3 times the amount of federal research funds as SCD. The SCD community of individuals, families, and advocates are attuned to the needs but not given sufficient voice, Dr. Barabino commented, and mistrust and strained provider-patient relationships limit trials and compromise care. However, she noted, new therapies are on the horizon, and change is needed.

Dr. Barabino suggested strategies to remove bias in research. These strategies include user-oriented collaborative design that centers the voices of racially marginalized populations and involves them in design; community-based participatory research; appropriate use of race within a study design; racially concordant investigators and physicians; earned trust; education for patients, providers, and researchers; and a mindset of health equity for all. She noted that many of these strategies are not considered when designing clinical studies,2 yet they can improve health outcomes.

Building trust is essential, she stressed. Students can enter training with biases and professors can perpetuate them. She pointed to recent research on the value of clinician peer networks and collective learning to reduce race and gender bias (Centola et al., 2021).

Dr. Barabino concluded with a quote from 19th century leader Frederick Douglass that “power concedes with a demand.” Racial biases stem from a racist power structure, she said, and it is time to demand elimination of racial biases in research and study design.

___________________

2 See, for example, M. Alegria, S. Sud, B. E. Steinberg, N. Gai, and A. Siddiqui; 2021; Reporting of participant race, sex, and socioeconomic status in randomized clinical trials in general medical journals, 2015 vs 2019; JAMA Network Open 4(5):e2111516; DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11516.

ANTI-RACISM IN ACADEMIA

Dr. Laurencin shared a portion of a video recorded of the talk he gave when awarded the Herbert W. Nickens Award from the American Association of Medical Colleges.3 He shared his vision for changing the landscape in which antiracism is part of inclusion and diversity efforts. He said:

My belief is that we have to move to inclusion, diversity, equity, antiracism, and learning, or an IDEAL path. Antiracism is a form of action against racism. . . . By learning, I mean understanding ways in which Black people are affected by the specific kinds of racial discrimination called anti-Blackness; understanding the history of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color; and moving from “ally” to “ride or die partner” in the antiracism movement.

Dr. Laurencin urged using learning in a constructive way to move forward. One example at the University of Connecticut is the U.S. Anti-Black Racism course for faculty and students. He explained that the free 1-credit course covers a foundational history and concepts related to systemic and anti-Black racism, and provides resources at UConn to continue development of an understanding and to combat anti-Black racism. He urged moving from DEI to IDEAL as a pathway to move the nation forward.

Dr. Laurencin noted that the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (AIChE) has adopted this IDEAL path, as stated on the association’s website.4 Dr. Laurencin also explained this IDEAL path in an editorial in Science (Laurencin, 2019). “I call it an IDEAL path because the pathway will be different for different organizations,” he explained. AIChE will use the concept in a learning process for members. At the time of the workshop, the Faculty Senate at UConn was planning a vote to require the U.S. Anti-Black Racism course for all incoming freshmen. He noted the course is available at no cost on FutureLearn.5

___________________

3 Dr. Laurencin received the 2020 Herbert W. Nickens Award. For more information on the award and a full recording of his acceptance remarks, see https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/aamc-awards/nickens/2020-laurencin.

4 See https://www.aiche.org/chenected/2021/02/ideal-path-equity-diversity-and-inclusion.

5 To access the course, go to https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/us-anti-black-racism.

DISCUSSION

Dr. Marrett shared her reflections about the presentations and commented on the relevance to the work of the Roundtable. She noted Dr. Laurencin’s emphasis on antiracism for the collective good, beyond the lives of underrepresented groups. Reflecting on the title of the session, she said “stakeholders” comprise everyone, including people currently in or seeking to enter science, engineering, and medicine. She praised the distinguished careers of the presenters. “They could have gone in very different directions,” she commented. “They could have spent more time on their own research, not concerned with matters of inequity. They have combined their own research with concern about social justice.” She posed the question that “if antiracism works to benefit the entire society, why aren’t there more to take this on?”

Dr. Marrett then asked the presenters how they deal with backlash or opposition to antiracism work. Dr. Reid underscored the importance to anchor the work within the leadership. People who are skeptical should be heard out, but the HMS deans continue to say the work is important and to set standards. “We must be able to tell the nay-sayers that is what the organization says is important and this may not be the right institution for you,” she commented.

To respond to and manage those not on board, Dr. Laurencin said his mantra has been to assume good intent unless shown otherwise. He said the learning process is important to achieve dramatic changes in residency programs that have little diversity. Dr. Barabino called for learning by doing. She noted the tendency to wait for action until everything is learned or everyone is onboard. “Do not get stuck,” she urged. “If we wait, we will never get anything done.” Dr. Daley pointed out that racism exists and cannot be debated or denied. “While I can understand individuals have strategies for approaching it, it is very important that leadership sets the standard and expectations,” he stressed. “A strong leadership stance is needed that there must be change. How the change happens can be the subject of vigorous debate.”

Dr. Marrett reflected on the role of learning and knowledge. Skepticism can be taken as resistance, but it could result from limited knowledge, she opined. Dr. Laurencin referred to Dr. Jones’s points about the effects of racism on society as a whole (see Chapter 2) with three observations. First, with fewer scientists from other countries remaining in the United States, the entire population of Americans to work in SEM is needed. Second,

the tradition of Blacks in science shows ingenuity that can produce results, such as discoveries by Lewis Latimer (electric power inventions) and Elijah McCoy (steam power inventions). Third, it has been found that the U.S. counties with the most lynchings had the highest overall mortality rates, showing that racism has an effect not just on Blacks but on whites.

In response to a question about how to incentivize and bring predominately white faculty onboard with antiracism work, Dr. Barabino said it must be part of the institutional mission, embedded, and communicated over and over. It must be part of plans, what will be credited, with resources allocated and space to have conversations, she continued. Dr. Reid agreed with the need to infuse antiracism throughout the organization. “This is the standard, this is part of our ethos. It is not just a policy,” she said. “You knelt [in protest]—but what changes did you do when you stood up?” She said change requires identifying problem areas, removing sacred spaces, and conducting courageous conversations in the context of training. Dr. Laurencin added the need “for the L word—an antiracism lens,” such as in selecting people for awards or for residency programs. He noted the positive effect when a director of a residency program had all those involved in selecting residents view a video about racism and bias. “The system is beginning to absorb this,” he posited. “I am a prisoner of hope that people will embrace it.”

The cost of not focusing on antiracism is lost opportunity, said Dr. Daley. He referred to research about the loss of productivity when people do not have the opportunity to reach their potential, as shown through the research of the Opportunity Insights organization led by Raj Chetty, Ph.D. (and included in the Roundtable’s September 2020 workshop on educational pathways; see also http://opportunityinsights.org).6 Dr. Barabino also commented on the profound basic human loss. Dr. Reid added that from the student side, individuals who have trained at an institution have choices and will not stay where feel they do not belong. Since faculty is built from training programs, this has a downstream effect. Dr. Daley reported some changes. When he first went to division chiefs and department chairs meetings to present data about diversity and racism, there was 1 person of color among 66 department chairs, and there are now 6 individuals. He

___________________

6 To read the proceedings of the 2020 workshop on Educational Pathways, visit https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26391/educational-pathways-for-black-students-in-science-engineering-and-medicine.

also observed that graduates comment about what they learned from more diverse classmates.

REFERENCES

Buckley, M. R. F. 2021. Taking aim at racism: PME anti-racism task force prepares findings, recommendations. Harvard Medical School, News and Research (web page), April 2, 2021. https://hms.harvard.edu/news/taking-aim-racism.

Centola, D., D. Guilbeault, U. Sarkar, E. Khoong, and J. Zhang. 2021. The reduction of race and gender bias in clinical treatment recommendations using clinician peer networks in an experimental setting. Nature Communications 12(article 6585). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26905-5.

Hoffman, K. M., S. Trawalter, J. R. Axt, and M. N. Oliver. 2016. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Edited by S. T. Fiske. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113(165): 4296–4301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113.

Laurencin, C. T. 2019. The context of diversity (editorial). Science 366(6468): 929. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aba2319.

Obermeyer, Z., B. Powers, C. Vogeli, and S. Mullainathan. 2019. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 366(6464): 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342.

Sjoding, M., R. P. Dickson, T. J. Iwashyna, S. E. Gay, and T. S. Valley. 2020. Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. The New England Journal of Medicine 383(25): 2477–2478. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2029240.

Williams, S. A. 2011. Bias, Race. In: Goldstein, S., Naglieri, J. A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_329.

This page intentionally left blank.