Family Caregiving for People with Cancer and Other Serious Illnesses: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: Proceedings of a Workshop

Proceedings of a Workshop

INTRODUCTION1

The difficult and challenging journeys that people with cancer and other serious illnesses face are often made more manageable by the critical care and support of family caregivers. While they derive great joy and satisfaction from caring for their loved ones, the physical, psychological, emotional, and financial toll that a family caregiver experiences can be significant.

To examine the opportunities to better support family caregivers for people with cancer and other serious illnesses, the Roundtable on Quality Care for People with Serious Illness, the National Cancer Policy Forum, and the Forum on Aging, Disability, and Independence hosted a public workshop, Family Caregiving for People with Cancer and Other Serious Illnesses, on May 16–17, 2022. This workshop built upon previous work, including the 2016 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) consensus report Families Caring for an Aging America

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop has been prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

(NASEM, 2016), which called for developing a national family caregiver strategy that recognizes the essential role of caregivers to the well-being of their loved ones. The report noted that family caregivers are not a heterogeneous group and include diverse people of all ages and backgrounds, some of whom do not have a family connection or legally defined relationship with the care recipient but are friends, partners or neighbors. Moreover, the report points out that the circumstances of individual caregivers and the caregiver context are extremely variable. Family caregivers may live with, nearby, or far away from the person receiving care. Regardless, the family caregiver’s involvement is determined primarily by a personal relationship rather than by financial remuneration. The care they provide may be episodic, daily, occasional, or of short or long duration. The caregiver may help with simple household tasks; self-care activities such as getting in and out of bed, bathing, dressing, eating, or toileting; or provide complex medical care tasks, such as managing medications and giving injections.2

This workshop unfolded over six sessions. Greg Link of the Administration for Community Living (ACL) opened the workshop with a Keynote Address that provided an overview of the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support and Engage (RAISE) Family Caregivers Act, and set the stage for subsequent sessions that explored the diverse needs of family caregivers; the resources, support, and training required by family caregivers; several exemplars of effective programs that meet these needs; and the importance of integrating caregivers into the health care team. Presentations also examined key research gaps and opportunities and discussed ways to include caregivers in research activities. The workshop’s final session explored the relevant policy landscape, and initiatives on the national and state levels to support family caregivers, such as the RAISE and the Caregiver Advocacy, Research, and Education (CARE) Acts as well as potential employment policies and insurance benefit designs to support family caregivers. To highlight the critical role of the family caregiver, insights and perspectives of the family caregiving experience—the caregiver voice—were incorporated throughout all of the workshop sessions.

This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the presentations and discussions and highlights suggestions from individual participants to improve

___________________

2 The NASEM report uses the terms “family caregiver” and “caregiver” interchangeably and does not use the terms “informal” or “unpaid” although such terms are often used in the economics and medical literature to differentiate family caregivers from “formal” caregivers—paid direct care workers (such as home care aides) or health and social service professionals.

support for family caregivers. These suggestions are discussed throughout the proceedings and are summarized in Box 1. Appendices A and B contain the workshop statement of task and workshop agenda, respectively. The speakers’ presentations (as PDF and audio files) have been archived online.

OPENING REMARKS

Randall Oyer, clinical professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine, medical director of the Ann B. Barshinger Cancer Institute, and medical director of oncology and of the Cancer Risk Evaluation Program at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health, opened the workshop by noting that in his 40 years as a physician, he personally has seen the critical impact that caregivers make. He added, however, that in his view, the medical profession has misunderstood and undervalued this vital role. Grace Campbell, assistant professor at the Duquesne University School of Nursing, and director of quality and system integration at the Family CARE Center in the gynecologic oncology program at the Hillman Cancer Center at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, built on Oyer’s remarks by noting the universality of the caregiving experience. Almost everyone, she observed, is or will be a caregiver at some point in their lives. Nevertheless, with more than 50 million family caregivers in the United States, the health care system has yet to provide widespread, systematic implementation of meaningful programs and resources (AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020). Campbell’s clinic, for example, offers a listening and supportive ear, assistance with navigating the complex health care system, and referrals to the few resources that are available, but these services barely scratch the surface of what many caregivers need. “Clearly, real change is needed,” said Campbell.

ACL’S ROAD MAP FOR CHANGE

To set the stage for the first session, a short video, entitled “Faces of Caregiving,”3 produced by the ACL was shown. Following the video, Greg Link, director of the Office of Supportive and Caregiver Services at ACL, began by remarking that Campbell’s call for health system recognition of caregivers requires a focused and comprehensive approach at both the federal and state levels to examine the needs and concerns of family caregivers

___________________

3 The short video can be seen at https://acl.gov/RAISE/report (accessed July 20, 2022).

and address them proactively in person- and family-centered ways. “For an experience as common as caregiving, one as old as humanity itself, we do not have a cohesive national approach for addressing an issue that will eventually impact nearly every one of us in some way, and not necessarily in a positive way,” said Link.4

Link shared that he has seen the need to address the challenges of caregiving both professionally, over the course of his 35 years in the aging field, and personally, when he cared for his aging parents. Even as someone who considers himself well versed on the issues, he was surprised at how little he knew about what to do, where to go, and whom to call when faced with the myriad challenges of caring for his parents. Certainly, programs and services were available, but they were fragmented and often hard to locate and access. Despite many positives to caring for a family member, Link observed that, if intense, long, and difficult enough, it will likely result in serious physical and emotional conditions and serious impacts on careers and family finances.

Link explained that the ACL is responsible for implementing the requirements of the RAISE Family Caregivers Act of 20175 and the Supporting Grandparents Raising Grandchildren Act.6 Between those two

___________________

4 For more information on the diversity of the caregiving experience, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PGvTOIwnoys (accessed June 9, 2022).

5 Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage (RAISE) Family Caregivers Act of 2017, Public Law 119, 115th Congress (January 22, 2018).

6 Supporting Grandparents Raising Grandchildren Act, Public Law 196, 115th Congress (July 7, 2018).

acts, Link noted that he and his team are trying to address the breadth of the family caregiving experience. The RAISE Act has three key components: a Family Caregiving Advisory Council, which ACL established in 2019; an initial report to Congress, which the advisory council delivered in September 2021 (RAISE Family Caregiving Advisory Council, 2021); and a national family caregiving strategy, which the advisory council and Supporting Grandparents Raising Grandchildren Advisory Council are developing and will be implementing together. Link explained that the advisory councils’ efforts were combined to take a cohesive approach to developing an inclusive and respectful national response to the needs of family caregivers.

ACL’s report to Congress7 includes 26 recommendations, each accompanied by a story from caregivers and links to videos to bring the recommendations to life, under five broad goals:

- Awareness and outreach

- Engagement of family caregivers as partners in health care and long-term services and supports

- Services and supports for family caregivers

- Financial and workplace security

- Research, data, and evidence-informed practices

Shortly after ACL began implementing the requirements of the RAISE Act, The John A. Hartford Foundation asked how it could help. The collaboration led to the RAISE Family Caregiver Resource and Dissemination Center,8 which the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP) developed with funding from the foundation.9 With assistance from Community Catalyst, the University of Massachusetts Boston, and the National Alliance for Caregiving, NASHP helped ACL collect what Link described as “an incredible amount of public input at every step along the way,” including input from caregiver focus groups and information gathered during stakeholder listening sessions with aging and disability organizations.

___________________

7 https://acl.gov/programs/support-caregivers/raise-family-caregiving-advisory-council#:~:text=On%20September%2022%2C%202021%2C%20the,for%20better%20supporting%20family%20caregivers (accessed July 20, 2022).

8 Additional information is available at https://www.nashp.org/the-raise-family-caregiver-resource-and-dissemination-center/ (accessed June 9, 2022).

9 See https://www.johnahartford.org/grants-strategy/the-raise-act-family-caregiver-resource-and-dissemination-center (accessed August 11, 2022).

The advisory councils are using the information gathered through these activities and the 26 recommendations to develop the national strategy, which will identify actions that the federal government, along with states, local communities, providers of health and long-term services and supports, and others can take to recognize and support family caregivers (ACL, 2021). Link noted that the councils have solicited input from 15 federal agencies regarding actions that they would commit to. Link explained that the strategy will seek to eliminate redundancies across agencies and promote greater adoption of the following:

- Person- and family-centered care across settings;

- Assessment and service planning;

- Information, education and training supports, referral and care coordination;

- Respite options;

- Financial security and workplace issues; and

- Service delivery based on the performance, mission, and purpose of a program.

The national caregiving strategy, observed Link, will speak directly to the diverse needs of family caregivers and diversity and inclusion issues. It will be four separate but interlocked documents, starting with a narrative and framing of issues and the 26 recommendations, plus three from the grandparents council, reframed as outcomes that the two advisory councils believe the country needs to achieve. The second document details the more than 350 actions that the federal agencies committed to, within the scope of their current programs.

A third document will discuss actions that states, communities, clinicians, long-term care providers, employers, researchers, faith-based organizations, schools, and other entities can take, based largely on input gathered from the focus groups and listening sessions. It will also include an intensive review of existing reports and recommendations that other organizations have issued and tools, resources, links to other strategies, and examples of successful strategies. The goal is for this to be useful and serve as a road map for any sector that wants to better support and recognize family caregivers, noted Link.

The final document contains the key crosscutting considerations identified by the councils as critical to every action, including the following four broad themes:

- Need for person- and family-centered approaches: As the U.S. works to create a system of interrelated responses to the needs of family caregivers, it is important that the family caregivers themselves—not health care systems or providers—remain the focal point.

- Recognize and address trauma and its impact: Provide support to family caregivers in a trauma informed way.

- Focus on diversity, equity and inclusion: Advance equity by recognizing that family caregivers from unserved, underserved, and/or marginalized communities experience unique needs that often go unaddressed. They are more likely to experience significant disparities in the intensity of caregiving and greater negative physical, emotional, and financial impacts.

- Recognize the importance of direct care workers: The development of a robust, well-trained, and well-paid direct care workforce is critical to ensuring family caregivers and the people they support have access to reliable, trusted supports and assistance when and where they need it.10

Link pointed out that the strategy will not be mandatory, and the RAISE Act does not give ACL any enforcement authority. He expressed confidence, however, that the strategy will become a tool for educators, researchers, advocates, families, and program leaders to examine what they can do, take what they have and see what might be missing, and make it work better and more efficiently with less duplication. Link observed that caregiving can be anxiety producing, empowering, overwhelming, exhausting, hopeful, and lonely, but a national strategy can elevate the conversation, reframe the narrative, drive change and innovation, promote greater recognition and inclusion of family caregivers, be a tool for advocacy, guide program planning and policy development, and shape research. ACL, he added, believes in the power of the consumer voice, which has informed everything it has done to implement the RAISE Act and Grandparents Act.

Link quoted Abena Apau Buckley, a family caregiver featured in the ACL video: “I’m glad that I had the means to be able to do it the way that I did, and still there’s so much that we lost because of how little real support is at a societal level that I had… You’re [going to] get sick, your family members are [going to] get sick, your kids might get sick, that is a given, so

___________________

10 For more information see: https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/RAISE_SGRG/NatlStrategyToSupportFamilyCaregivers.pdf (accessed June 9, 2022).

given that that’s going to happen, why do we not have a solution for how to help people?” Link said he believes that the time is now to provide a path to answering Abena’s question.

Reactor Panel

Sheria Robinson-Lane, assistant professor in the Department of Systems, Populations, and Leadership at the University of Michigan School of Nursing, shared her perspective that it is imperative that the national strategy be inclusive in its approach to what a modern family looks like and the different types of caregivers who need information in ways that allow them to live an optimal life. She pointed out that this is not just about improving access to care and services for people who are dealing with disability, chronic illness, dementia, and other health conditions in a way that relieves some of the caregiver’s burden. It also means giving caregivers access to support for their mental health so they can meet their own daily needs and supporting the most vulnerable caregivers including older adults, people with disabilities, communities of color, as well as the LGBTQ+ community. Robinson-Lane called for an intersectional11 approach in thinking about how to make sure that the person who is most in need is both getting help and being heard. She asked, “How are we ensuring that their voices are still heard when we are in a position of power and leadership? That is truly the way to make sure that a national agenda is inclusive and that we do not leave anybody behind in our approach, so as to make sure that the needs of families and communities are met.”

Loretta Christensen, a member of the Navajo Nation and chief medical officer of the Indian Health Service (IHS), said she appreciated that ACL’s information-gathering process solicited input from tribal communities, which have challenges that other communities do not. In Indian Country, she noted, 9 of every 10 caregivers are family members. During the COVID-19 pandemic, with so much of the medical community focused on testing, vaccinating, and treating COVID patients, what limited services

___________________

11 Intersectionality is defined as “the complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism, and classism) combine, overlap, or intersect especially in the experiences of marginalized individuals or groups.” Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Intersectionality. In Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary. https://unabridged.merriam-webster.com/collegiate/intersectionality/ (accessed September 28, 2022).

existed became even more scarce. This increased family caregiving responsibilities, even for those who had family members that were seriously ill from COVID, further underscoring the importance of reliable and sustainable support for caregivers.

Christensen explained that Indian Country deals with many social determinants of health that make caregiving challenging. For example, one third of the Navajo Nation homes on tribal land do not have electricity or running water,12 making it imperative to adjust a care plan that typically includes a mechanical device. In addition, broadband does not reach 50 percent of the homes in rural areas in Indian Country,13 making it difficult for those families to access telehealth. She explained that an approach to training, educating, and providing resources is needed for what is essentially a new health care workforce composed of family members.

One imperative, said Christensen, is to provide enhanced access to effective mental health care for caregivers and develop culturally sensitive and appropriate materials. There are 574 recognized tribes, she noted, each with its own customs and understanding of cancer, dementia, and other chronic diseases. Christensen added that the IHS is including trauma-informed care in all of its staff trainings to empower staff to show respect to everyone they encounter. She emphasized that innovation and partnerships are crucial to addressing the challenges of family caregiving in Indian Country.

Discussion

Julie Bynum, professor of medicine in the Division of Geriatric Medicine at the University of Michigan, opened the discussion session with the observation that she was struck that Black and Native American communities, for example, have long been involved in family caregiving in the absence of national and large-program support. She wondered about a way to learn from communities and use that information in creating the national strategy rather than the national strategy telling the communities what to do. Link explained that in the initial RAISE report to Congress and forthcoming National Family Caregiving Strategy, the needs and perspectives of

___________________

12 See https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2016/01/f29/38_nuta_denetclaw_ahasteen.pdf (accessed July 29, 2022).

13 See https://www.npr.org/2018/12/06/673364305/native-Americans-on-tribal-land-are-the-least-connected-to-high-speed-internet (accessed July 29, 2022).

diverse communities, including tribal communities, are addressed and considered. He specified that racial, cultural, ethnic, and linguistic differences were treated as crosscutting themes that speak to all the recommendations and actions contained in the strategy.

Robinson-Lane commented that too often, the approach is to address problem solving with the majority in mind, which leaves out a minoritized population. In her view, the programs should be designed specifically targeted for minoritized populations that incorporates sensitivity to cultural differences. Another challenge is to include the voice of health care workers who are also caregivers. She noted that often, particularly in the COVID-19 era, health care workers are already feeling considerable stress, and adding the burden of caring for young children at home or an aging parent adds to their stress. To keep the workforce healthy, it is important to support its members, specifically the low-wage workers who are most likely to come from minoritized backgrounds.

Christensen remarked that including people from rural and extremely rural areas at the table and providing services to the people who live there is extremely challenging and not well appreciated by those in more urban areas. Christensen described the area in which she grew up, the Navajo Nation, which encompasses 27,000 square miles,14 where resources can be far from the people who need them. Tanker trucks deliver water to many homes because they do not have running water, and that large geographic area has only 14 grocery stores, creating significant challenges for getting food to families in need. Serving this community and other extremely rural areas is not impossible. However, it requires a different approach, one that accounts for the lack of home care and other services that are more common in less isolated areas and the increased cost of transportation to get to an appointment. Christensen emphasized that partnerships and funding are the key, with the latter being in short supply. On the positive side, she noted, the community cherishes the relationships between the reservation’s families and its elders. Increased education and training for families and optimizing public health nursing and the reservation’s “community health representatives” are needed to support family caregiving.

Bynum noted the importance of reverse translation, which involves applying innovations and lessons learned from communities to inform a more robust national strategy. She asked about signs of increased cohesion

___________________

14 See https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/21/us/navajo-cherokee-population.html (accessed August 4, 2022).

among community, hospital, family, and clinical services and all the different disciplines involved in delivering care. Link noted that at the federal level, the initial report to Congress included an inventory of the federal programs and initiatives that support family caregivers and that the relevant agencies’ responses overwhelmingly recognized the role they need to play and the interconnectedness of their programs. The key, he said, will be how the agencies come together once the national strategy is released to reduce duplication and identify areas where they can improve collaboration. It will also be important to see how the states, communities, health and long-term services providers, faith communities, school systems, and others will view the strategy and look for ways they can participate. “Once we know what is possible and what supports are needed in the way of technical assistance, we can then begin to take that next step to support that kind of development,” said Link. “I believe that the framework we are creating for a national approach will serve as a real conversation starter.”

Robinson-Lane noted that in her experience, communication is often lacking between federal and state agencies and communities regarding available services and how to access them. She asked, “How do we get information about cigarettes and alcohol into the communities effectively, but we cannot seem to get messaging about important health information?” She also called for health care organizations to be more thoughtful about reaching out into their communities and abandon the attitude of “build it and they will come,” which is not happening. There is also a need to identify the barriers that are preventing individuals from engaging with the health care system and develop approaches and resources to care for them. The key, in Robinson-Lane’s view, will be to be intentional about developing relationships with the community, which she believes will lead to more sustainable and inclusive programs.

Christensen stressed the importance of delivering services through a patient-centered medical home, which is an added challenge in Indian Country, particularly for people with cancer, because IHS facilities typically refer individuals to academic centers in bigger cities. Putting together a plan for accessing services at the local level is critical in those situations, as is providing the means for patients or family members to get answers immediately about available resources and how to access them.

Responding to a question about plans to disseminate the national strategy, Link explained that after ACL delivers that to Congress in the early fall, it will convene a joint meeting of the two advisory councils to release the strategy publicly, as it did for the initial reports. ACL will also look broadly

to partners in the aging and disability communities to help with dissemination efforts and with the advocacy community to examine what they can do to advocate for change at the local, state, and federal levels.

Link reiterated that the RAISE Act does not provide ACL with any enforcement authority, and Congress only appropriated $300,000 to implement it. In contrast, the National Alzheimer’s Project Act15 came with appropriations to fund research and programs. The RAISE Act, he said, is more about encouraging agencies and programs to collaborate effectively and eliminate duplication. The goal is also to provide a road map for change and a cohesive set of ideas and actions that states, communities, and other sectors can implement. “I truly believe that this will be the tool for mobilizing activity at multiple levels, as well as a tool for advocates to say this is what we need, and this is how we should be working more effectively,” noted Link.

Oyer commented on the complexity of the multi-caregiver approach, especially when caregivers in the same family have different needs and require different linkages to help. Robinson-Lane suggested that hospice and palliative care organizations may be a model for effectively engaging with families, as they are accustomed to mediating conflicts among family members who have different ideas about what the end of life should be. One approach to consider, she said, is to involve the family in decisions about goals of care and planning early in the process. Talking about goals of care in a family setting changes the dynamic, moving it from a strictly medically focused conversation to a more thoughtful one that helps create a plan that takes into account the needs of patients, caregivers, and family members.

Christensen agreed that it is best to approach caregiving as a family, set ground rules and goals, identify a spokesperson, and hold periodic conversations, since the caregiving approach is fluid as the needs of care change with advancing illness. She has found that involving palliative care specialists, clinicians, community health workers, or other local service providers in these regular, recurring conversations has been successful in creating a strong family plan and can be a crucial anchor throughout.

Link observed that it is important to handle family disagreements delicately and tap into the strengths that each individual can bring to the caregiving dynamic. One family member, for example, might be better

___________________

15 For more information see: https://www.nia.nih.gov/about/nia-and-national-plan-address-alzheimers-disease and https://aspe.hhs.gov/collaborations-committees-advisory-groups/napa (accessed October 12, 2022).

suited to handle financial matters, while another may better handle chores. A comprehensive, evidence-informed caregiver assessment involving the entire family, particularly when coupled with care navigation services or case management, can help eliminate potential discord and infighting. A multipronged approach is important because each member of the caregiving team approaches an identical situation with different ideas, fears, strengths, and biases, and it is critical to acknowledge that reality if care is to be truly family centered.

In closing, Bynum emphasized that ACL needs collaborators from the caregiving community to help implement its national strategy, which is only a starting point. She emphasized that reaching the finish line will require action from communities, health systems, health care payers, and others.

UNDERSTANDING THE NEEDS OF FAMILY CAREGIVERS

Jennifer Ballentine, executive director of the CSU Shiley Haynes Institute for Palliative Care, introduced the second session by noting that it would focus on the diverse needs of family caregivers through stories shared by speakers that identified a specific need and proposed a solution. Rebecca Kirch, executive vice president for healthcare quality and value at the National Patient Advocate Foundation (NPAF), explained that her caregiving experience started in the mid-2000s when her brother was diagnosed with lung cancer that had metastasized to the brain. This experience was difficult because the oncology team was eager to push “everything they had,” even though it was clear that he did not have much time to live and did not want to spend what little he had left undergoing debilitating chemotherapy and radiation. Kirch and her family were confronted with the challenge of honoring her brother’s desire to go to the beach one last time. “We got him there, but it was tricky, and we did not have the support we needed from the health system,” said Kirch, who noted that regimented clinical treatment schedules do not offer the flexibility that families or caregivers often need as they are caring for their loved ones.

Kirch explained that experience taught her to stand her ground, a lesson she applied when her mother was diagnosed several years later with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The family focused on palliative care to ensure that her mother’s life would be as enriching and engaged as possible. Currently, Kirch is the primary caregiver for her husband, who has a neurological condition of unknown origin. The combined stresses of caring for him and their two young children led to significant difficulty sleeping

and eating. Kirch shared that community, including the members of the Roundtable on Quality Care for People with Serious Illness, supported her when she had her first panic attack. “Community is the key that makes up for system gaps,” she said.

Cathy Bradley, professor and associate dean for research at the Colorado School of Public Health, University of Colorado at Denver, and deputy director of the University of Colorado Comprehensive Cancer Center, said that as a health economist, her research interest lies at the intersection between work and health and the tradeoffs that individuals and caregivers have to make when faced with serious illness. She related an experience of a participant in a study she was conducting. The individual was diagnosed with aggressive breast cancer within months of giving birth to her second child. She had been the family’s primary wage earner. Her husband had finally been promoted into a position that he had worked hard to attain. He wanted to maintain that job and its income and health insurance yet also care for his wife and their two young children. Bradley noted that this story underscores the need to develop a business case for employers to keep caregivers in their jobs. She pointed out that although that has become true for disabled individuals and is becoming more common for young parents after childbirth, workforce support for all types of caregivers is not a reality.

Wendy Lichtenthal, associate attending psychologist and director of the bereavement clinic in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, shared the story of a young couple with three children. While nursing their youngest, the woman found a lump in her breast; within a month, she was diagnosed with breast cancer with local metastases. The husband immediately became her physical and emotional support in the face of debilitating lymphedema and nerve pain, which made it impossible for her to even carry their infant.

When the COVID-19 pandemic closed the school where her husband taught, he had to teach remotely while also caring for his own children and his wife, who was undergoing chemotherapy. One evening, after a treatment, his wife said she was not feeling well. He could see that something was wrong but could not decide if he should take her to the emergency department, which would require finding a caretaker for the children and possibly expose her to the COVID-19 virus. He suggested that his wife lie down, and they would revisit the situation in the morning.

The woman never woke up. The grieving husband was full of regret about his decision. Riddled with guilt, he eventually contacted his local hospital to see what kind of support was available. He attended its bereavement

group, but it was only much older bereaved spouses, none with dependent children, and he left feeling more alone than ever. He turned to the list of therapists the hospital had given him, but due to the pandemic and resulting mental health crisis, only one of the 11 he called had time for him, and that therapist did not specialize in bereavement therapy.

This story provides important context for the need for continuity of care for caregivers into bereavement, Lichtenthal observed. She explained that the bereavement experience is often directly related to the caregiving experience because guilt and regret are the norm rather than the exception. Thus, she said, bereavement-conscious training is needed for medical staff, and health systems need to invest in personnel dedicated to screening and triaging evidence-based care for bereaved caregivers. “There is talk about family-centered care, and what family-centered care is doing is fostering an attachment and a dependence on the health care system, so it is the responsibility of the health care system to continue that care for caregivers and not abandon them,” stressed Lichtenthal. “It is really a moral imperative.”

Dannell Shu, a member of the Pediatric Palliative Care National Task Force and Minnesota Department of Health’s Palliative Care Advisory Council, explained that she was the caregiver for her son, who was born with severe brain damage and not expected to live for more than a few hours or days. While he was in the neonatal intensive care unit, she and her husband received a palliative care consult, which led to sustained palliative care services that allowed them to transition their son to their home. Shu shared that their goal was to bring him home, regardless of how long or short his life would be. Shu explained that their palliative care team taught them how to care for their son and make medical decisions for him based on their values. She added that palliative care freed her, as the mother and primary caregiver, to navigate the hundreds of clinic visits with more than 15 specialists and arrange for caregivers to help her at home.

Shu and her husband set up an intensive care unit (ICU) at their home, and Shu’s husband had to take on additional jobs to make ends meet. They quickly learned that running an ICU requires more than one person; fortunately, Shu’s mother was able to move to Minnesota to help. Importantly, they were able to obtain medical assistance through Minnesota’s Medicaid program, which allowed them to hire paid caregivers. Recruiting, hiring, and training them, most of whom had no experience with a medically complex child, became a new job for Shu. She explained that they were able to apply for a Medicaid waiver that provides additional supports for medically complex individuals, which enabled them to receive consumer-directed

community support to meet their son’s medical needs. More than 90 percent of that paid for caregivers. The waiver budget enables a family caregiver to be paid 40 hours a week. Though the $17/hour did not cover all their needs, it did allow Shu’s husband to only work one job (rather than multiple jobs) and to give more focused time and attention to caring for their son.

Against the backdrop of these personal caregiving stories, Alexandra Drane, cofounder and chief executive officer of ARCHANGELS, presented the Caregiver Intensity Index,16 a tool designed to assess a caregiver’s intensity level by asking a wide range of questions that relate to

- the unpredictable nature of caregiving

- disagreements with family members about sharing the caregiving burden

- feeling underprepared for most situations they encounter as a caregiver

- feeling overwhelmed by caregiving demands

- feeling depressed

- feeling manipulated by the person one is caring for

- having someone to turn to for support

- the financial impacts of caregiving

Drane explained that the tool not only helps to validate the stressful experience of caregiving but also provides caregivers with a common language with family, friends, coworkers, and neighbors.

Discussion

Ballentine opened the discussion session by asking the panelists about the business case for employers to provide caregiving supports, such as leave. In response, Bradley pointed out that it costs a company about three times an employee’s annual salary to replace them. Fifty percent of caregivers work 35 hours a week or more, forcing them to balance caregiving and work. In her view, the business case starts with getting employers to see that caregivers are not a burden and then enabling a conversation around flexibility. While the Americans with Disabilities Act requires employers to accommodate people who are sick, with cancer mentioned specifically, caregivers are not afforded the same accommodations. Bradley observed that

___________________

16 For more information see: https://www.archangels.me/ (accessed September 28, 2022).

her research on cancer patients has revealed work flexibility to be the single most important accommodation, and she imagines that caregivers would benefit in the same way.

Drane cited data from surveys conducted in late 2020 to early 2021, which found that 43 percent of the more than 10,000 adult respondents identified as parents of children, caregivers of adults, or both (Czeisler et al., 2021b). Drane noted that the survey data also revealed that in the early stages of the COVID pandemic, caregivers of adults reported a higher levels of mental distress than other adults did (Czeisler et al., 2021b). The data indicate that 70 percent of these caregivers are struggling with at least one significant mental health condition, such as anxiety, depression, COVID-related stress, trauma- and stress-related disorders, or suicidal ideation (Czeisler et al., 2021a). Drane added that nearly a quarter of U.S. adults are now the “sandwich generation”: they are caring for both children and parents, and approximately 85 percent of them are struggling with a significant mental health impact (Czeisler et al., 2021b).

Drane noted that prior to the pandemic, 8 percent of the individuals who used the Caregiver Intensity Index (CII) tool were “in the red”—experiencing the most stress with the least support; that tripled to 24 percent during the pandemic, where it held steady for 20 months (Czeisler et al., 2021b; The National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020). Drane reported that 29 percent of individuals who used the CII were currently in the red, due to the pressures of inflation, global unrest, and other factors (Czeisler et al, 2021b). Drane emphasized that this translates to a greater than 90 percent risk of at least one significant mental health impact, underscoring that caregiving is about mental health, which is part of the business case for providing caregiver support (Czeisler et al., 2021b).

Another economic argument for supporting caregivers, added Lichtenthal, is “presenteeism” (people returning to work who are not functioning at full capacity). Bradley emphasized that it is important to remember that despite a compelling business case for supporting workers who are caregivers, there is also a moral imperative to do the right thing.

Caregivers also develop unique skillsets that can save the health care system money. Kirch pointed out that Minnesota’s caregiver support policy likely has a significant return in the form of savings to the state and health care system. Bradley called for Minnesota’s waiver policy to be systematized nationally. She noted that during the pandemic, the state allowed family caregivers to be paid for more than 40 hours a week, a recognition of the scope of the caregiver shortage.

When asked to discuss the resources that helped Shu and her husband, Shu said that connecting with parents and others in a similar situation is important. While organizations such as the national Courageous Parents Network17 did not exist when her son was born, it is now a critical support system. Shu pointed out that it was other parents, not anyone in the health system, who alerted her to the waiver program,18 and that the state’s consumer-directed community support system provides trained and paid community connectors to help families write the plan required to secure a waiver. Another valuable connection, said Shu, was with a public health nurse who pointed her to resources and people in the community.

Kirch emphasized that palliative care is a critical resource, as is families learning from families. Navigators can also be a good resource to connect caregivers to services. NPAF provides support over the phone, but philanthropic provision of these services will not address all of the nation’s needs. Rather, strategies need to be developed to integrate social and financial needs navigation into the health system.

Drane commented that many caregivers are not aware that they are in that role, and this is particularly true of people who are most at risk, including those in rural, Black, Latinx, Hispanic, younger, and essential worker populations. Rather, they view themselves as being a good family member, a friend, or someone who cares. Drane also shared that a physician whom she met after giving a presentation did not realize he was a caregiver and could benefit from bereavement support, even though he and his wife were caring for two children under five and also his father and mother-in-law, both of whom died from COVID. Drane noted that because people do not see themselves in the caregiver role, they may not take advantage of available employee-assistance programs.

Ballentine, commenting about the need to start addressing grief among family members at the time of diagnosis and not just toward the end of life, asked the panelists for their ideas on how to make care more bereavement conscious. Lichtenthal replied that at the threat of loss, the grief process begins. However, anticipatory grief is different from the losses that happen along the way that also cause grief. Grief and the related separation distress response, she said, are about not wanting to lose someone, and that triggers

___________________

17 For more information, see https://courageousparentsnetwork.org/ (accessed July 18, 2022).

18 See https://mn.gov/dhs/people-we-serve/people-with-disabilities/services/home-community/programs-and-services/cadi-waiver.jsp (accessed February 15, 2023).

a desire to protest that loss, which affects decision making. “Bereavement consciousness for the health care system is a mindfulness of what is coming up that is actually grief,” she explained.

While many might recognize on an intellectual level that discontinuing curative treatment, for example, might be reasonable and reduce suffering in the long term, such awareness is overpowered by the separation distress response. It is important, said Lichtenthal, for providers to recognize the role grief and fear of loss play in decision making. Providers also need to be conscious of what a family is going to carry forward into bereavement; they are always going to wonder if they could have done more. Kirch, taking that idea one step further, said it is also important for clinicians to recognize anticipatory grief in themselves and the role it might play in their decision-making process regarding the desire to continue treating a patient when the family and patient are ready to move to palliative care and hospice.

Ballentine suggested that the clinician’s office is the place to lay the groundwork for patient- and family-centered care, which involves keeping caregivers informed about the care they will need to provide and emphasizing the need to care for themselves. Stressing the importance of viewing the patient and family as the unit of care, Lichtenthal commented that an investment in resources is needed to support caregivers from the time of diagnosis, including training clinical staff how to discuss such matters in a way that empowers people and engages in regret prevention. Shu added that it would help caregivers if they attended every appointment, if only to make sure they are hearing the same information as the patient in terms of care needs, which would also enable them to discuss the care plan directly with the provider.

Drane said her organization conducted a study that found that 80 percent of a large panel of health care providers believe that caregivers should be present during patient visits and be engaged in care plan discussions (Shah and Drane, 2021). However, when asked if they actually engage caregivers, only 20 percent of the health care providers said they do (Shah and Drane, 2021). Drane explained that she and her colleagues strategize about ways to ensure caregivers are at the table when care plans are developed and discussed.

One approach to elevating the role would be to include it on each caregiver’s resume, suggested Drane. This formal recognition of unpaid caregiving as work would underscore that the individual is building a new skillset that is of value to potential employers. Drane recommended that caregivers visit the ARCHANGELS website to be reminded of the job skills

they have developed. “You know how to problem solve. You are a product manager. You get things done under tight time constraints that everyone else has said is impossible,” said Drane. Bradley added that standing behind and supporting caregivers can generate a tremendous amount of loyalty to the company.

Insurance companies should also recognize the value of caregivers because they are the best in-network providers possible, said Kirch. “The cost-sharing we do is completely unquantified, but it is a big boon for the insurance plan business,” Kirch emphasized. She asked why the insurance industry could not develop a benefit, such as credit toward a deductible or the out-of-pocket limits. Kirch called for businesses to demand that insurance companies involve caregivers in benefit design to address some of these challenges. Ballentine suggested offering family caregiving insurance, similar to long-term care insurance.

Ballentine then asked the panelists for their ideas on how to support the needs and concerns of long-distance caregivers. Shu suggested identifying specific ways that extended family members can be involved even from afar. Kirch said she faces this problem with her father, who lives hours away, and she cannot leave home for long because she has to manage in-home dialysis for her husband 6 days a week. Her best friend, who lives in the same town as her father, checked on him. Then her friend connected her with community resources that conducted a geriatric assessment in his home, where he wanted to stay. Kirch was able to find what she called an “underground of caregivers,” which was critical given the lack of any established system. This gap exists across the nation and needs to be addressed, she emphasized.

Bradley said she finds it ironic that large- and medium-sized employers are competing with each other on worker well-being programs but have no plan for when someone actually gets sick or becomes a caregiver. Small employers, she added, are not subject to the requirements of the Families with Medical Leave Act or the Americans with Disabilities Act, so no protections are in place for those employees. “There needs to be a cultural change as to how we treat people who are providing care for others, because it is such a vital part of our economy,” said Bradley. Drane added that retention and recruitment challenges are reasons why more human resources departments are starting to pay attention to the notion of supporting caregivers.

An audience member questioned whether expecting U.S. businesses and federal and state governments to support caregivers is the best approach. Bradley replied that no one action is going to solve this problem,

and making the business or social needs case is only part of the solution. Bradley reiterated that supporting caregivers should be valued from a cultural perspective. Lichtenthal added that the universality of caregiving is something to capitalize on when talking to people in power who will likely experience this on a personal level eventually. Ballentine noted the great deal of rhetoric around the importance of keeping families intact and families being the foundation of society, so an argument can be made that this is about supporting families and allowing them to stay together. A workshop participant suggested that a useful way to think about caregiving would be to recognize that it is an essential component of delivering health and medical care services and supports.

Drane noted that one issue not raised in the discussion is the presumption that people are able to, equipped for, and are ready and wanting to take on caregiving responsibilities. Drane used the example of “Hospital at Home,” suggesting that hospitals use a new “checklist” in determining whether a potential caregiver is a good fit for taking on the responsibilities. This would include someone taking that person into a separate room and explaining in detail what caregiving at home would entail. It is important that the person is enabled and empowered to make an informed choice about whether it is a role that they are willing and able to accept.

In closing, Ballentine commented that stories can persuade, and the stories shared during the session are so powerful and relatable that they can underpin future policy discussions and decisions.

PROVIDING EFFECTIVE SUPPORT FOR FAMILY CAREGIVERS

A Dementia-Friendly Program for African American Faith Communities and Families Living with Dementia

Fayron Epps, assistant professor at Emory University’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, opened the third session, which focused on exemplars of caregiver support programs. Epps described Alter, a faith-based community program. Epps and her colleagues launched Alter in 2019 to encourage culture change, shift perceptions about dementia, and strengthen support services within and in partnership with African American churches (Epps et al., 2019, 2020a, 2021, 2022; Gore et al., 2022).19 Epps pointed out that Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias are the fourth leading

___________________

19 Additional information is available at https://alterdementia.com (accessed June 9, 2022).

cause of death among older African Americans.20 The idea for Alter arose after she and her colleagues identified a huge need to expand awareness about dementia and address the social isolation that it entails coupled with the importance of religion to the well-being of older African Americans living with dementia (Epps and Williams, 2020).

In meeting with the pastors, Epps found that many of them did not realize the extent of the problems dementia was causing in their congregations and communities. Alter staff also found that they needed to work with faith leaders to send the message that family members and their caregivers are welcome, supported, and accepted by the congregation, whatever their burdens might be. The ultimate goal for Alter, said Epps, is to preserve access to church—and the social support it provides—for families living with dementia.

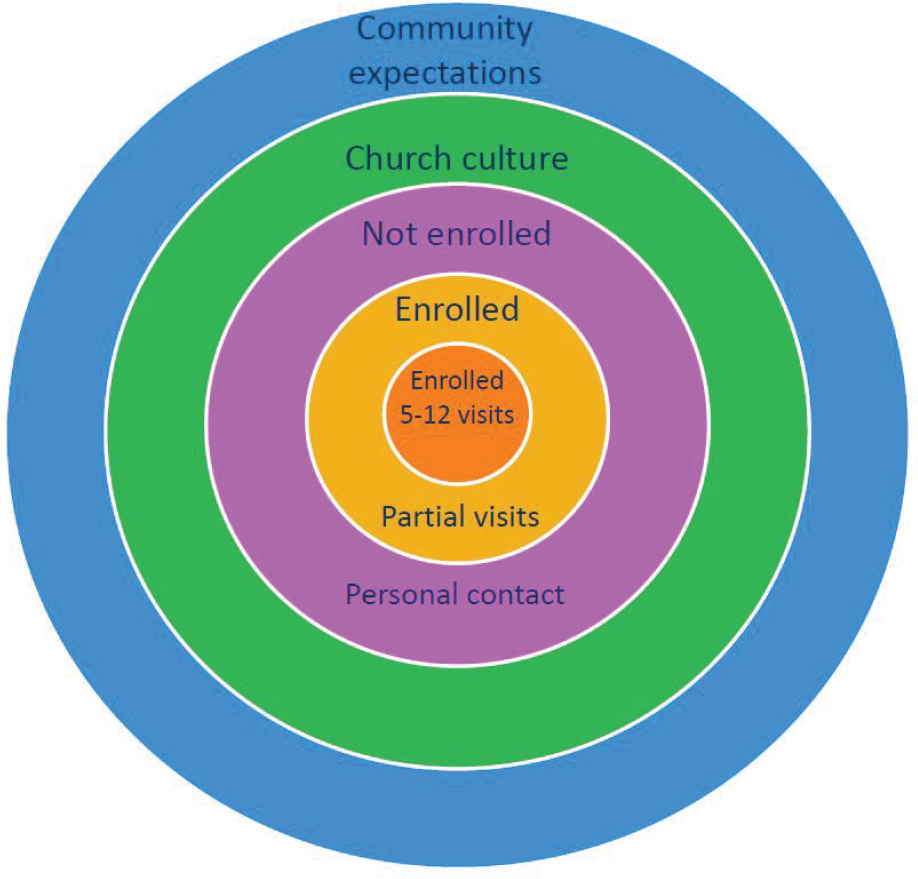

Alter provides training sessions, materials, and videos for church leaders and in-person and virtual support for members with dementia and their families when they need additional help or have questions that the leaders cannot answer. Epps and her colleagues also hold education sessions for an entire congregation to help them become more aware of the needs of those with dementia and the people who care for them while providing tools and techniques for addressing the cultural taboos associated with dementia. Epps said that she always asks the churchgoers if they want to be part of a trailblazing dementia-friendly community; they may not see the need immediately, but she and her colleagues gently persist in introducing the program and talking about how important it is for the broader community.

Epps explained that Alter’s partnerships with churches come with a 2-year commitment and a memorandum of understanding that drives home what the churches are committing to do. Once a church joins the Alter community, it receives a welcome kit with brochures and materials for church members and a financial contribution to ensure that it can implement the program. Epps and her colleagues then ask the churches to carry out eight core activities (Box 2) and eight additional activities around education, support, and worship that the churches can customize. An education activity, for example, might be holding Memory Sunday, a yearlong collaboration between faith communities and health and community organizations focused on raising awareness about memory loss, aging, and Alzheimer’s disease in the African American community that culminates

___________________

20 See https://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/health-disparities-race-and-alzheimers (accessed August 16, 2022).

in an event on the second Sunday in June.21 A support activity might be organizing a Memory Café, forming a dementia support group or respite program, or establishing a resource library. Creating visual aids and adjusting the length of the service are examples of worship activities (Epps et al., 2020b). Epps noted that after 2 years, Alter revisits whether a church wants to remain part of the initiative; if so, it becomes a legacy partner.

Epps noted that Alter has formed partnerships with 21 churches in Georgia, two in Illinois, and one in Florida over a 2-year period. Alter’s website has a function that allows families to locate an Alter church close to their home.

The next step, Epps explained, is to find partners with other faith communities. Epps noted that Alter is part of the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Program,22 and she is

___________________

21 Additional information is available at https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/alzheimers-dementia-outreach-recruitment-engagement-resources/memory-sunday-toolkit (accessed September 28, 2022).

22 For more information on the Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program, see https://www.hrsa.gov/grants/find-funding/hrsa-19-008 (accessed August 4, 2022).

looking to work with more churches around the country. So far, she has partnered with ones in Minnesota and Virginia and is in discussions with one in Arkansas. “We are trying to expand and create an infrastructure to be able to support Black churches as we address family caregivers that are supporting those living with dementia,” said Epps.

Malcoma Brown-Ekeogu, a member of Alter’s advisory committee, is a caregiver for her husband who has the behavioral variant of frontal temporal degeneration. This condition causes him to yell out inappropriate things or touch people inappropriately. Before joining Alter, Brown-Ekeogu and her husband had stopped attending church because of those behaviors, and she felt lost in terms of how to continue to maintain connections with the community. Once Brown-Ekeogu became involved with Alter and started taking part in different focus groups, she began sharing her experiences—peeling the Band-Aid off the sores in her life and sharing them, as she put it—so that she might make things better for other care partners23 experiencing the same problem. Doing that, she said, helped her grow and become a better care partner herself.

Brown-Ekeogu noted that someone from Alter attended the first session with her to see how things went. The sermons are only 10–15 minutes long, which is just long enough to keep her husband engaged. Initially, she said, he did not participate, but the second time, he clapped his hands to one of the songs and said “Amen” at the end of prayers. Brown-Ekeogu said that on days when she feels blue, she rewatches the program videos on YouTube to refresh herself. She said that her view on the benefits of the Alter program is that with unity comes strength.

A Clinical Service Dedicated to Supporting Cancer Caregivers

Allison Applebaum, associate attending psychologist and director of the Caregivers Clinic at Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Cancer Center, opened her remarks noting that when she arrived in 2010 as a postdoctoral fellow, she recognized a vast unmet need for psychosocial support for cancer caregivers. MSK offered, for example, a once-a-month drop-in group, which was the norm for comprehensive cancer centers nationwide. However, a large body of research indicated that caregivers desired support focused on their own unique psychosocial needs—support they were not receiving—in addition to the supportive services offered regarding care for their loved ones.

___________________

23 The speaker used the term care partner rather than caregiver throughout her remarks.

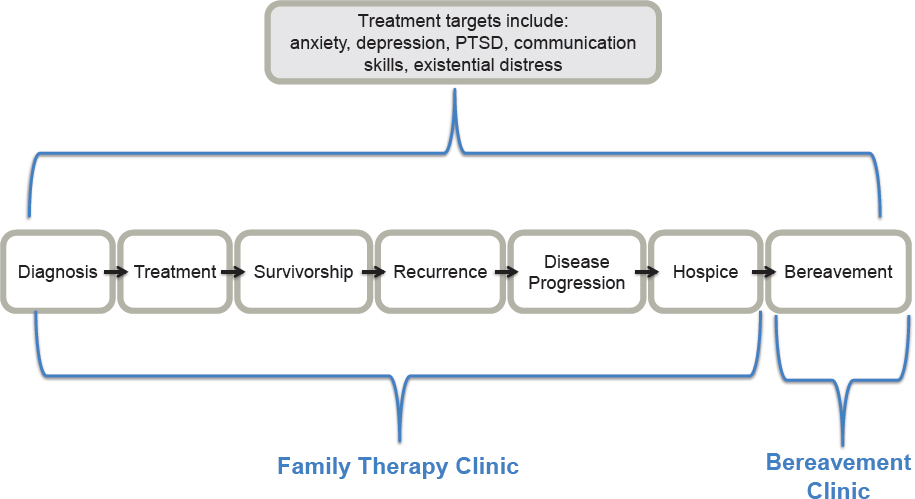

In response to these needs, Applebaum established the Caregivers Clinic, alongside the cancer center’s Family Therapy Clinic and Bereavement Clinic, as part of the MSK Family Care Program (Figure 1). The Caregivers Clinic strives to assure that no caregiver or family experiencing significant distress as a result of their role goes unidentified and deprived of necessary psychosocial services. It provides care that encompasses the entire journey from diagnosis through bereavement. Applebaum noted that many caregivers come in because they have significant symptoms of anxiety, depression, and, increasingly, post-traumatic distress disorder (PTSD). Many also find it difficult to speak with their loved ones and the health care team about advance care planning, what to expect, and how to plan, so in addition to education and support through various psychotherapeutic approaches, the clinic offers communication skills training. Inevitably, many caregivers also have concerns related to existential distress, which Applebaum pointed out, we all experience when we connect to our—and our loved ones’—mortality.

The Caregivers Clinic began in November 2011 and, by November 2021, had 222 referrals from the MSK Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and another 515 referrals from other MSK departments, according to Applebaum. Those referrals led to 408 psycho-diagnostic visits that turned into over 4,000 follow-up psychotherapy sessions and 144 caregivers requesting or requiring medication management. The clinic has con-

SOURCE: Adapted from Applebaum presentation, May 16, 2022.

ducted three ad hoc group sessions for 98 couples and families focusing on a specific concern, such as how to talk about the future with a family member.

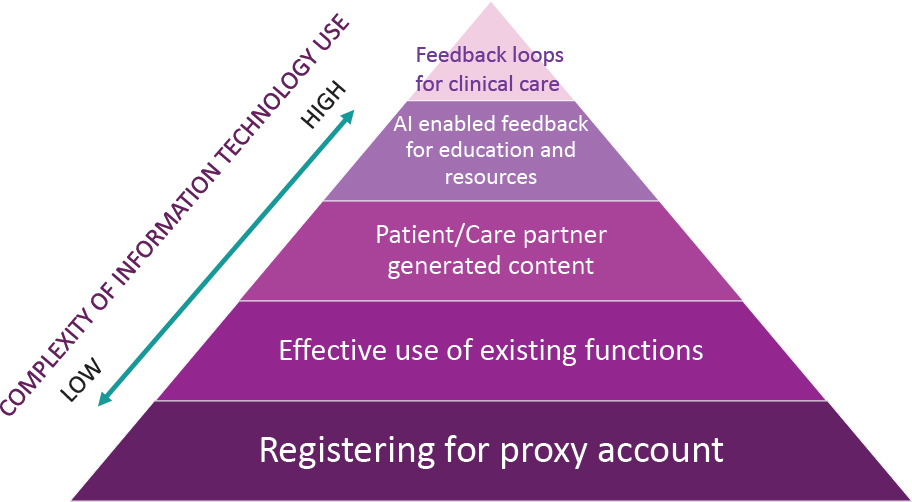

Applebaum and her colleagues advocated that caregivers should register as patients at MSK so that they would have their own medical record. For Applebaum, documenting caregiver data in a medical record should be part of the standard of care (Applebaum et al., 2021). At the diagnostic visit, caregivers receive an ICD-10 diagnostic code that is entered into the medical record and used to bill for services. The clinic bills all of its services to insurance carriers except when caregivers come in for follow-up care with the program’s fellows, which is free. Since March 2020, the clinic has held its sessions via telepsychiatry, and they are paced to meet caregiver needs. “The reality is some caregivers come to us with intense distress and in need of ongoing care, and others come to us purely to learn how to communicate with their loves ones,” said Applebaum. This is something they can achieve with a small number of sessions, she added. Sessions rely heavily on empirically supported interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy.

Applebaum pointed out that the clinic is dealing with extraordinary demand amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic. Challenges have arisen because of long wait times for care and infrequent sessions. The clinic supplements care from its attending physicians by involving externs, interns, and fellows. It also refers caregivers on the wait list to clinical trials designed to test psychotherapy interventions tailored specifically to caregivers’ needs. The clinic also developed a Caregiver-to-Caregiver mentoring program that pairs caregiving experts—individuals who are no longer in the role or bereaved at least 1 year—with current caregivers to provide ad hoc support that is both free and offered with greater flexibility in scheduling.

The cost of care is an important concern, particularly when someone has insurance that does not include mental health coverage. Applebaum and her colleagues refer those caregivers to program fellows, who provide free care. Another challenge arises when patients come from places outside of New York and New Jersey, where she and her colleagues are licensed to practice. “I, as a licensed psychologist in New Jersey and New York, cannot provide care to a patient of mine if they go home to Ohio or Pennsylvania,” she said. During the pandemic, they received temporary licenses to treat patients from out of the area, but that flexibility is ending. Now, she said, she and her colleagues refer those patients to social workers and community-based organizations.

Applebaum identified the switch to telemedicine as a silver lining to the COVID-19 pandemic. It addressed many historic barriers to psycho-

social service use among caregivers; the number of no-shows dropped precipitously. However, it has created a new challenge in meeting the soaring demand.

Applebaum says the clinic can improve distress screening to identify caregivers who truly need its supportive services in contrast to those who are distressed due to other reasons, such as financial concerns, and would benefit more from speaking with patient financial services. The clinic is also piloting the CancerSupportSource-Caregivers tool (Zaleta et al., 2021), an automated, online screening tool that Applebaum believes will be effective in helping triage caregivers to the appropriate level of care. She would also like to see the hospital do a better job of identifying caregivers when patients first come for care, creating a medical record immediately, and conducting early and repeated distress screening assessments, especially at transition points in patients’ care. Applebaum concluded her remarks by noting that expanding peer support through the Caregiver-to-Caregiver mentoring program is also on her wish list.

Peter Gee, a nursing student at New York University School of Nursing and caregiver for his husband, who was diagnosed with glioblastoma in November 2018 and passed away in June 2020, credits MSK with providing the best, most comprehensive, and holistic support for him and his husband. Gee explained that when his husband was first diagnosed, he wanted to put every effort into what he thought was “the right thing to do” for someone with terminal cancer. He began weekly therapy sessions and convinced his husband to try it, too. After several sessions, Gee’s husband declared that it was not helpful and stopped. Gee also stopped going, because it was taking up too much of his time, which included working and supporting his husband in his treatment plan. “I remember thinking back at the time how exhausting it was to have to explain the logistics of brain cancer to my very well-intentioned therapist,” said Gee. “The sessions also felt so open ended, which at the time was not what I needed.”

Gee shared that during their cancer journey, he learned that the patient and caregiver can respond differently to the diagnosis. His husband, for example, remained optimistic that he would be among the 5 percent of glioblastoma patients who survive to year 5. Gee, on the other hand, experienced anticipatory grief every moment of his day. Six months in, his husband’s oncologist informed them that the original tumor had become two. Nonetheless, his husband remained optimistic while Gee, in his words, “started losing it.” Fortunately, the neuro-oncologist and nurse noticed his visual cues and pulled Gee into a separate room where he could

break down in private and not affect his husband’s optimistic outlook. It was then that he learned about the caregivers clinic, which connected him quickly to a psychotherapy trial for caregivers that tested a process called meaning-centered psychotherapy (MCP). MCP focuses on helping patients and caregivers connect to sense, meaning, and purpose despite the unique and complementary challenges they face (Breitbart et al., 2018).

Gee found the eight MCP sessions transformative, and he asked if his husband could join in. Gee recalled how important it was for both of them to explore their identities before, during, and after cancer. MCP also gave them a shared language they used to communicate better with each other. “Debriefing with one another about each session was not only healing but was a starting point for our own conversations as a couple,” said Gee. For example, the sessions made Gee think about what he would do after his husband died; in one session, he thought about shifting careers from human resources into nursing. Gee shared this idea with his husband, who asked why he did not start nursing school immediately. Nearly 2 years after his husband’s death, Gee is halfway through an accelerated undergraduate nursing program.

Gee shared that a key lesson he learned is that seamless integration between primary and behavioral health providers, nurses, and social workers is the exception, not the norm, even though it leads to better patient outcomes. “If the medical team had ignored me and did not connect me to the caregivers clinic and the MCP trial, I would be experiencing grief and widowhood very differently,” he said. Gee now volunteers to be a mentor in the caregiver-to-caregiver program, which has reminded him that there is no right or wrong way to be a caregiver. Caregivers continue to experience extraordinary distress and need caregiver-specific supports.

Another observation that Gee shared was that the home hospice system is broken. “We did 8 weeks of home hospice, and because it was during the first wave of COVID-19, we lost all of our community support,” said Gee. “It really is unacceptable that we leave it up to families and loved ones to do this on their own.” In Gee’s view, ways of providing financial support to family caregivers need to be developed along with ways to expand access to home health aides. Gee also proposed that a death doula should be part of the standard of care.

Gee’s final observation was even though he and his husband had supportive employers and excellent health care insurance, knew how to advocate, and were legally married, the logistics of living and dying with brain cancer were “beyond overwhelming.” Gee said that a quote from

Vaclav Havel, former president of the Czech Republic, helped sustain them during their cancer journey. “He said that hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism. Hope is not the conviction that something will turn out, but the certainty that something makes sense regardless of how it turns out. I had mistakenly misunderstood the hope that Jeff expressed at the beginning of our cancer journey,” said Gee. He and his husband felt as if they were passengers along for a ride on a turbulent roller coaster, but the programs they participated in put them back in control and allowed them to focus on the decisions they could control. “We were able to get clarity on where we stood individually and as a couple, and this allowed us to have better connections with our primary care team, our family, and our friends,” said Gee.

Family Caregiving in Indigenous Communities

Loretta Christensen, the IHS chief medical officer and enrolled member of the Navajo tribe, explained that the mission of IHS is to raise the physical, mental, social, and spiritual health of American Indians and Alaska Natives to the highest level, and its vision is one of healthy communities and quality health care systems through strong partnerships and culturally responsive practices (see Box 3 for an overview of the IHS).

IHS relies on programs such as the Public Health Nursing Program24 for home visits, assessments, and patient evaluations. Some of the nurses speak the Navajo language, for example, and will do home visits; if they do not, they travel with a driver who is fluent in the language of the particular tribe to allow for adequate and accurate communication. Community Health Representative Programs,25 which the tribes typically run, send people into rural areas to conduct assessments, educate and care for families, and arrange for support services for families. For example, the program arranged for deliveries of food and disinfectants during the pandemic.

Given the shortage of food stores, caregivers have to decide whether they are going to spend their time caring for their family or making the long journey to and from the nearest grocery store. They also face the challenge of getting around the reservation, given the high cost of gas and large number of unpaved roads. Christensen noted that when the weather makes the roads impassable, IHS employees will park their car near a

___________________

24 See https://www.usphs.gov/professions/nurse (accessed August 29, 2022).

25 See https://www.ihs.gov/chr/ (accessed August 4, 2022).

major road and walk miles to their client. Because money is often limited, families only buy small amounts of care supplies, which requires even more long-distance trips.

Another key challenge is the lack of access to cancer care (Guadagnolo et al., 2017). Typically, patients must travel to urban or suburban areas, and often family members cannot afford to accompany them. This not only deprives the patient of the support they need but prevents family members from hearing instructions from and asking questions of the health care team. This latter problem is compounded because these distant facilities often do not have a level of cultural sensitivity and appropriateness to discuss cancer and care in a way that a tribal member can understand. Christensen added that members of different tribes can have a different understanding about cancer in general, making it important to customize information delivery. “Sometimes, it is not just one size fits all in Indian Country,” said Christensen.

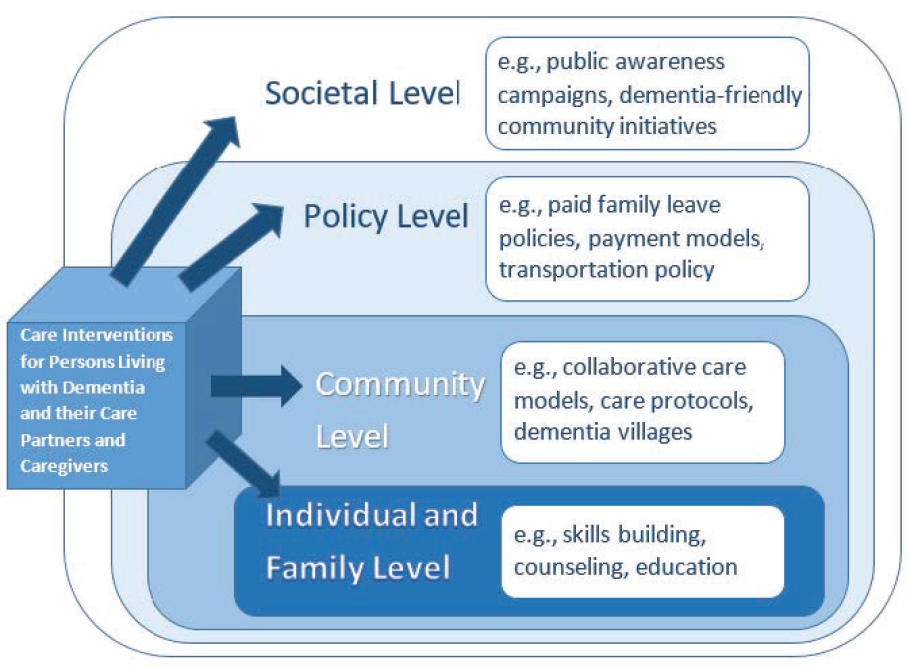

IHS works with partners from some tribal organizations to define the needs in Indian Country. Given that the majority of caregivers are family members, it is important to get feedback from the caregivers as to what they need, what frightens them, and how IHS can support them. One goal is to provide education and resources and to include the caregivers in each step of the care planning process by having as many family members at clinic or home visits as possible. Another goal is to enhance the scope of work for public health nursing, community health representatives, lifestyle coaches, and navigators to address workforce issues in the coming years, given the shortage of nurses. The idea is to get as much work done in the communities so that every patient does not need to travel to a facility. This effort includes bringing cancer resources near tribal communities, getting doctors to spend time in Indian Country, or enhancing telehealth capabilities.

At the heart of the IHS family caregiving strategy is ensuring that the diverse needs of Indigenous communities are included. IHS wants to develop reliable, sustainable support systems for family caregivers and increase its work with partners to provide information and educate tribal communities about family caregiving. Christensen’s team is also holding discussions regarding data collection and analysis, to get a better understanding of the challenges, and looking at caregiving and multidisciplinary teams, to see how they can fit into the patient-centered medical home. Christensen noted that IHS is rolling out a new system of primary care that will include more support for this work, and it will combine behavioral health, substance misuse screening, and social work into one visit.

Elton Becenti, Jr., a member of the Navajo Nation and field engineer for IHS who lives in Crownpoint, NM, a larger town on the Navajo reservation, described his family’s experience with cancer and caregiving. Becenti explained that while Crownpoint has a full-service IHS facility, patients have to travel 60 miles to the New Mexico Cancer Center in Albuquerque.

Becenti’s journey with caregiving began in 1999 when he was 16 and his mother, who was going through a divorce, was diagnosed with colon cancer. IHS did not provide support services at the small Crownpoint facility. He took on as many responsibilities as he could, including cooking, cleaning, and taking care of his younger brother. Becenti identified the lack of empathy from his mother’s main oncologist as a key challenge, noting it was difficult to process all the medical information.

Eight years after his mother died, Becenti’s father was also diagnosed with colon cancer. By then, the cancer center had opened in Gallup. It was an hour away but half the distance that his mother had to travel for treatment. IHS caregiver support services were limited, and once again, he lacked resources for how to cope with and relieve the stress of being the primary caregiver. The cancer center offered some counseling; the staff, including the oncologist, were helpful, caring, and understanding, unlike his earlier experience. In addition, the primary care physician at the Crownpoint facility was kind and compassionate, which made a world of difference. Nonetheless, he had days when he felt he was battling cancer more than his father was and had many months of little to no sleep. Becenti’s father also ultimately passed away.

Based on these two experiences, Becenti recommended improving care in rural areas by having respite care, a team to relieve the caregiver for a day so they can take a break, and someone who could deliver meals a few times a week. He also suggested that virtual technologies, such as Zoom, and telehealth services could provide the caregiver with a virtual team that could check in on them and the patient and provide more support. He added that teams could help educate both patients and caregivers about their treatment regimens, the side effects they experience, and medicines that could relieve those side effects. Lacking such support, Becenti shared that he had to educate himself by finding information online, such as on the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and Colon Cancer Care Alliance websites.

ACCA’s Advanced Illness Care Program

Janice Bell, associate dean for research and professor at the University of California at Davis Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing, explained that

the Alameda County Care Alliance (ACCA)26 is unique in that, unlike other programs for people with serious illness, which often start within academia or within a health system and then reach out to the community, ACCA started within the African American faith community and built partnerships on that base. She pointed out that because about 87 percent of African Americans are actively involved in organized religion,27 the church has excellent potential to educate and empower and has been doing so for hundreds of years. It also has the advantage of being a trusted source in the community (Harmon et al., 2014).

From its beginning in five churches in 2013, ACCA brought together members of the health, public health, philanthropic, and academic communities with the goal of advancing equity for people with serious illness and their family caregivers. Kaiser Permanente, through its community benefits program, was the original funder and continues to support the program, while Bell’s institution provides technical assistance, and intervention development, training, and evaluation support. The Public Health Institute provides project management and acts as the fiscal sponsor. ACCA launched its pilot program in 2014 and has grown to include 42 churches. Bell noted that the California Health Care Foundation is currently funding a feasibility pilot project to understand the needs for establishing an ACCA hub in the Los Angeles area.