Federal Policy to Advance Racial, Ethnic, and Tribal Health Equity (2023)

Chapter: 7 Social and Community Context

7

Social and Community Context

INTRODUCTION

Health outcomes reflect the social and community context in which people live. Accordingly, efforts to address health inequities must consider the social and community factors that impact health and well-being. Social relationships, which provide people with critical support and can act as a buffer against negative conditions, such as unsafe neighborhoods, discrimination, and financial instability, are needed for thriving. The Healthy People 2030 initiative emphasizes that “relationships and interactions with family, friends, coworkers, and community members” and “the social support [one needs] where they live, work, learn, and play” are important factors in determining health outcomes (HHS, 2020). Likewise, the National Academies Communities in Action report notes that “individuals, families, businesses, and organizations within a community; the interactions among them; and norms and culture . . . social networks, capital,1 cohesion,2 trust, participation, and willingness to act for the common good” all function as

___________________

1 Social capital refers to “features of social structures—such as levels of interpersonal trust and norms of reciprocity and mutual aid—which act as resources for individuals and facilitate collective action. Social capital thus forms a subset of the notion of social cohesion” (Coleman, 1990; Kawachi and Berkman, 2000, p. 175; Putnam, 1993).

2 Social cohesion refers to “(1) the absence of latent social conflict . . . and (2) the presence of strong social bonds,” measuring “the extent of connectedness and solidarity among groups in society.” A cohesive society is characterized by abundant social capital, and social cohesion and social capital are “collective, or ecological, dimensions of society, to be distinguished from the concepts of social networks and social support, which are characteristically measured at the level of the individual” (Kawachi and Berkman, 2000, p. 175).

important social determinants of health (SDOH) (NASEM, 2017a, p.152). The social and community context is itself shaped by the structural context, namely, structural inequities, including the societal-level norms, policies, laws, regulations, institutions, and practices that underlie, maintain, and reinforce structural racism (see also Health Affairs, 2022; Hicken et al., 2018; NASEM, 2017a). These structural inequities stem from historical processes, such as slavery and settler colonialism, that have ongoing effects. Social and community context—from families, neighborhoods, and the institutions where people learn, work, and play to norms and culture—is also shaped by the SDOH outlined in previous chapters (e.g., economic instability, housing quality, climate change) (see Figure 1-2).

Despite recognizing this interplay with other SDOH, this chapter focuses on the relational, cultural, and normative elements of context. The following considerations within the social and community context domain offer significant opportunities to address racial, ethnic, and tribal health inequities and are explored in the chapter: violence, public safety, and the criminal legal system; historical trauma and healing; civic infrastructure and engagement; and one’s sense of community and belonging, which is impacted by experience, such as criminal legal system contact and various aspects of identity, including race, ethnicity, immigration status, disability status, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Although this report is unable to comprehensively cover all racial, ethnic, and tribal equity issues under this umbrella (see Chapter 1 for more information on how policies were selected), it provides policy examples that highlight how federal intervention in the social and community context can address health inequities. Specifically, the chapter explores the following policies: waiting periods for gun purchases; policies that increase accountability in policing and data collection, such as the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act; mass incarceration policies, such as long and mandatory minimum sentences; policies that acknowledge and provide redress for historical actions, practices, laws, and policies that caused enduring harm; and policies that build civic engagement and a sense of community and belonging. These examples include both policies that perpetuate inequities (i.e., mass incarceration) and policies that are successful and can be expanded or better funded for further improvement (i.e., the Special Diabetes Program for Indians and efforts to increase costewardship of federal lands, such as Joint Secretarial Order 3403).

VIOLENCE, PUBLIC SAFETY, AND THE CRIMINAL LEGAL SYSTEM

Structural racism, other structural inequities, and the legacy of federal laws and policies have contributed to racially and ethnically minoritized populations experiencing disproportionate violence, public safety issues,

and contact with the criminal legal system. For example, redlining and residential segregation have been linked to violent crime and racial disparities in police violence (Siegel et al., 2019; Townsley et al., 2021). These structural factors have also contributed to a disproportionate impact of gun homicide, fatal police shootings, and incarceration on Black, Latino/a, and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) people (Davis et al., 2022; Edwards et al., 2019; Giffords, n.d.; Gramlich, 2020; NAACP, n.d.). Research has linked these inequities to health and well-being. Data demonstrate that incarcerated individuals have poorer mental and physical health, including higher rates of mental health disorders, chronic illness, and infectious disease, compared to the general population (HHS, n.d.-c). The impacts extend to incarcerated individuals’ children, families, friends, and communities; research documents mental health, economic, and other effects on communities and families and increased risk for poverty, homelessness, learning and developmental disabilities and delays, attention disorders, aggressive behavior, and involvement with the criminal legal system among children with an incarcerated parent (HHS, n.d.-c; Lee and Wildeman, 2021; NASEM, 2017a). Police brutality has been linked to mental and physical health outcomes through physical injury and death, psychological distress, racist public reactions, financial strain, and systematic disempowerment of communities (Alang et al., 2017).

This section discusses three interrelated dimensions of social and community context: violence, public safety, and the criminal legal system. It reviews examples of federal policies that have impacted or, if enacted, could impact racial and ethnic health inequities and summarizes the relevant evidence. The criminal legal system is also relevant to other SDOH, including economic stability and health care quality and access, which are discussed in Chapters 3 and 5, respectively.

For the purposes of this report, the committee used the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of violence: “the intentional use of physical and psychological force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation” (WHO, 2002, p. 5). This definition encompasses more than just criminal acts; it also considers the impact of “feelings of insecurity and differential perceptions of threat and harm . . . deprivation, psychological abuse, and neglect” (Aisenberg et al., 2010, p. 17). Public safety concerns are central to public policy decisions and laws. Like the definition of violence, the definition of public safety used in this report moves beyond the absence of crime and the notion that the criminal legal system apparatus is the only way to deliver safety to communities. It also considers the role of that system in promoting safety but also enacting violence (e.g., police use of lethal force against racially

and ethnically minoritized individuals). Drawing from work attempting to link population health and public safety, public safety is conceptualized as “a sense of physical, emotional, social, and material security that fosters stability and is accompanied by support from community and society when needed” (Gourevitch et al., 2022, p. 716). More expansive notions conceptualize it as “a core human need that comprises not only physical safety but also security in health, housing, education, and living-wage jobs” (Gourevitch et al., 2022, p. 716). These definitions overlap with areas covered in other chapters of this report (i.e., housing, education, and economic stability).3 With these definitions in mind, this section reviews some examples of federal policies related to violence, public safety, and the criminal legal system.

Gun Violence

The lack of federal regulation of firearm access is one example of a policy directly related to violence and public safety impacting racial and ethnic health inequities. A history of disinvestment, structural inequities, and the legacy of past policies have had lasting effects on minoritized communities and contributed to Black, Latino/a, and AIAN people being disproportionately impacted by gun homicide compared to their White counterparts. Together, Black and Latino/a communities make up less than one-third of the population but three-quarters of gun homicide deaths (Giffords, n.d.). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) firearm fatality data demonstrate that firearm-related deaths reached a peak in 2020 at over 45,000 people. An analysis of these data by the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions reveals that, compared to their White counterparts, AIAN and Hispanic/Latino people were 3.7 times and twice as likely to be a victim of firearm homicide, respectively (Davis et al., 2022). Black people faced the highest risks—they were over 12 times more likely—and the risk for young Black men was especially high; Black men aged 15–34 were more than 20 times more likely to die by gun homicide. Although they make up only 2 percent of the total population, they made up about 38 percent of gun homicide deaths in 2020 (Davis et al., 2022).

For racially and ethnically minoritized women, who are disproportionately impacted by domestic violence, including intimate partner violence (IPV) (Breiding et al., 2014; Wertheimer and Hill, 2022), a recent decision by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals (United States v. Rahimi) has serious ramifications: the federal prohibition on firearm possession by those subject to domestic violence protection orders was ruled unconstitutional under

___________________

3 The committee acknowledges that multiple definitions of public safety exist and continue to be debated, adapted, and reimagined.

the Second Amendment.4 According to data reported from 18 states to the National Violent Death Reporting System, from 2003 to 2014, most female homicides were IPV related (55.3 percent) and involved firearms (53.9 percent) (Petrosky et al., 2017). Data demonstrate that transgender men and women are also disproportionately impacted by IPV (Peitzmeier et al., 2020). The ruling in United States v. Rahimi cited the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, which deemed unconstitutional a New York State law that required individuals to provide “proper cause” to receive a concealed carry license.5 Additional lawsuits challenging gun regulations (and directly citing Bruen) have been mounted, suggesting that the decision is likely to complicate ongoing firearm regulation efforts (Finerty, 2022).

Gun violence is also a children’s health problem, disproportionately so for racially and ethnically minoritized children. In the United States, firearm-related injuries are now the leading cause of death for children 1–19. Before being surpassed by firearm-related injuries in 2020, motor vehicle crashes were the leading cause of death from 1999 to 2019 (Goldstick et al., 2022). Data suggest that this increase, which coincided with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, is driven by increases in firearm-related injuries among minoritized children. One analysis found that child shootings among non-Hispanic White children did not increase during the pandemic, whereas rates for non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Asian children did (Jay et al., 2023). The authors hypothesize that this may be explained by the pandemic’s exacerbation of inequities in health, employment, and education. Other research has found that rates of violence from March to July 2020 were higher in low-income, racially and ethnically minoritized neighborhoods (Schleimer et al., 2022).

Evidence also demonstrates significant increases in firearm suicides among young Black adults: between 2013 and 2019, it increased by 84.5 percent and 76.9 percent, respectively, for young Black men and women (Kaplan et al., 2022). Gun violence also has implications for the health and well-being of the broader community (Collins and Swoveland, n.d.; NASEM, 2017b). Research demonstrates that exposure to violence by direct victimization is a predictor of gun-related delinquency (McGee et al., 2017) and links witnessing a severe injury or murder to depression and antisocial behavior (Schilling et al., 2007). Gun violence is a clear health equity issue and provides an opportunity for federal legislation to improve outcomes for racially and ethnically minoritized populations.

Although Bruen is likely to complicate efforts to regulate firearms, enacting a federal waiting period for gun purchases is one potential avenue

___________________

4 United States v. Rahimi, 59 F.4th 163 (5th Cir. 2023).

5 New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, 597 U.S. __ (2022).

to address this issue. Waiting periods serve several purposes. First, they interrupt the impulsivity that characterizes many acts of gun violence. Additionally, they provide time for law enforcement to uncover purchases being made on behalf of a prohibited person and complete background checks, which can take longer than the 3-day window provided by federal law. In 2021, 5,203 firearms were sold from federally licensed dealers to prohibited persons due to delays from the National Instant Criminal Background Check System that surpassed 3 business days (RAND, 2023c). Although four states and DC have passed waiting period laws that apply to any firearm purchase (the length varies by state, and five additional states have passed waiting period laws for certain firearms), most states have not passed such legislation, and there is no waiting period at the federal level (RAND, 2023c).

Recent causal evidence suggests that waiting period laws at the state level that delay a purchase by a few days may reduce gun homicides and suicides (Luca et al., 2017). In a 2017 study, researchers compared firearm deaths in states with and without waiting period laws over the same time and found that the laws were associated with a 17 percent reduction in gun homicides, these laws prevent about 750 gun homicides per year, and expansion to all states would prevent 910 additional gun homicides per year. The study also found these laws reduced gun suicide by 7–11 percent (Luca et al., 2017). A study similarly found that handgun purchase delays reduced gun suicides by about 3 percent (Edwards et al., 2018). Data about effects of such laws on racial and ethnic inequities in gun violence and on the implications of a federal waiting period law are still needed. In addition to limited evidence on effectiveness, it has been argued that a waiting period creates unnecessary additional burdens on first-time gun owners who have no intent to harm themselves or others and may need a firearm for protection. However, Luca et al. (2017) note that their findings point to waiting period laws as a method to reduce gun violence without restricting gun ownership. Although research is needed, given the disproportionate impact of gun homicide on Black, Latino/a, and AIAN populations and recent increases in firearm suicide among young Black adults, a federal waiting period is one potential policy lever that may counteract the impact of gun violence in these communities. Other firearm regulation policies that have received attention in recent years and may be worth exploring as avenues to address racial and ethnic inequities in gun homicides include policies for safe storage, background checks (for private sales/gun shows), firearm safety training requirements, mental health restrictions, a national gun registry, and banning high-capacity or assault-style weapons (APA, 2013; IOM and NRC, 2013; Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Prevention and Policy, n.d.-a,b; Monmouth University, 2019; RAND, 2023a,b).

Policing and the Criminal Legal System

Generations of discrimination and disinvestment and systemic inequalities within the criminal legal system have had a lasting impact on racially and ethnically minoritized communities, contributing to disproportionate crime and violence (NASEM, 2017a). Many policies intended to combat these issues and improve public safety have also caused harm. For example, data on policing policies, such as stop-and-frisk, and extremely punitive criminal legal policies, such as long sentences and mandatory minimums, show that such policies disproportionately impact Black, Latino/a, and AIAN people yet do little or nothing to address crime and violence (Dunn and Shames, 2019; The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence et al., 2022; Keating and Stevens, 2020; MacDonald, n.d.; Siegler, 2021). Combating these issues in minoritized communities will require not only considering potential new policies from a racial equity lens but also reexamining existing policies from this same perspective. The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2021 (JIPA), which passed the House but not the Senate, is one example of proposed reforms to address racial inequities in policing.6 JIPA aims to address not only the disproportionate impact of policing on Black, Latino/a, and AIAN communities but also the need for improved collection of data on racial and ethnic inequities in policing. The bill would end qualified immunity and the use of chokeholds and no-knock warrants in drug cases by federal law enforcement (Collins, 2021).

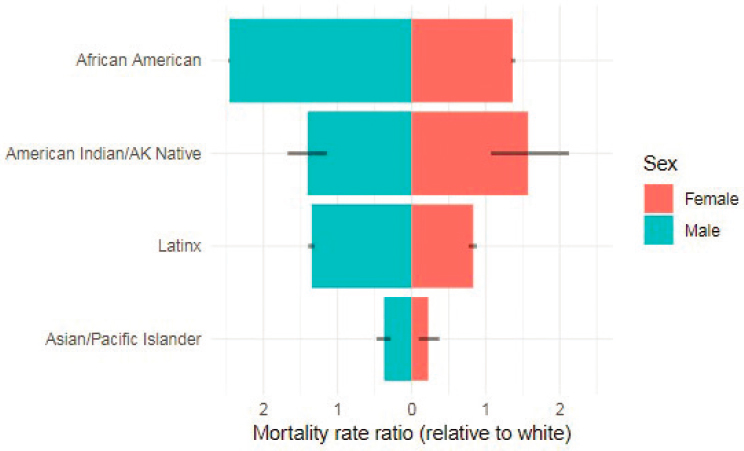

Administrative data are limited, and improved collection on inequities in law enforcement is needed, including on racial and ethnic inequities for chokeholds and no-knock warrants, cases dismissed due to qualified immunity by race and ethnicity of the plaintiff, and other outcomes. However, existing data reveal clear inequities in policing and police violence. Of 92,383 recorded stop-and-frisk stops in New York City between 2014 and 2017, 53 and 28 percent were of Black and Latino/a people, respectively, and only 11 percent were of White people (Dunn and Shames, 2019). Figure 7-1 illustrates inequities in lifetime risk of being killed by police use of force by sex and race and ethnicity at 2013 to 2018 risk levels (Edwards et al., 2019). The red bars indicate mortality rate ratios (relative to White people) for African American, Latinx, Asian and Pacific Islander, and AIAN women. The blue bars indicate mortality rate ratios (relative to White people) for men. African American, Latinx, and AIAN men are about 2.5, 1.3–1.4, and 1.2–1.7 times more likely, respectively, to be killed by police than White men. African American and AIAN women are about 1.4 and 1.1–2.1 times more likely, respectively, to be killed by police than White women. Latina women are 12–23 percent less likely to be killed

___________________

6 H.R. 1280, 117th Congress (2021).

NOTE: Dashes indicate 90 percent uncertainty intervals. Life tables were calculated using model simulations from 2013–2018 Fatal Encounters data and 2017 National Vital Statistics System data. Data for the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) population were combined with the Asian population—this provides an inaccurate representation of the NHPI population as a distinct racial Office of Management and Budget minimum category and masks inequities for NHPI people and within-group differences for Asian people.

SOURCE: Edwards et al., 2019.

by police than White women, and both Asian and Pacific Islander men and women are over 50 percent less likely to be killed by police than White men and women (Edwards et al., 2019). As noted above, police brutality has been linked to mental and physical health outcomes (Alang et al., 2017). Data suggest that officer-involved killings of individuals from racially and ethnically minoritized communities may negatively influence the educational performance of Black and Hispanic students who live nearby, and research is underway investigating how fatal police shootings might affect pregnancy-related and infant health in impacted communities (Ang, 2021; Noguchi, 2020). Improved data collection efforts are needed, but federal interventions that increase accountability in policing, such as JIPA, may help reduce inequities given that Black, Latino/a, and AIAN communities are disproportionately impacted.

Although the federal government has limited power over policing at the state and local level, JIPA attempts to address the issue at these levels by “[requiring] federal, state, tribal, and local law enforcement agencies to report data to DOJ on traffic violation stops, pedestrian stops, frisks

and body searches, and the use of deadly force by their law enforcement officers. Reporting agencies would be required to include in these data the race, ethnicity, age, and gender of the officers and members of the public involved” (James and Finklea, 2021, p. 2). The bill attaches conditions to the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant and Community Oriented Policing Services programs that are meant to incentivize compliance, but it is uncertain whether these programs provide enough funding to state and local governments to allow the loss of or reduced funding to actually do so (James and Finklea, 2021). Data compiled by the Urban Institute indicate that federal grants account for only a small fraction of spending on police and corrections (Urban Institute, 2023). Prior and related data collection mandates, such as the Death in Custody Reporting Act,7 have also been stymied by lack of enforcement (Bryant, 2022). JIPA could be improved by developing other incentives for state and local governments, such as grants to help them afford the staff and technology needed to comply with data reporting requirements (James and Finklea, 2021). With such improvements, full passage of this bill has the potential to address both the disproportionate impact of police misconduct on Black, Latino/a, and AIAN communities and the need to collect data on racial and ethnic inequities in law enforcement.

Federal policy changes related to incarceration also provide an opportunity to address the disparate impact of the criminal legal system on racially and ethnically minoritized communities. The United States has the highest rate of incarceration in the world; it accounts for almost 25 percent of the global prison population despite making up only 5 percent of the global population overall (NAACP, n.d.). Moreover, this mass incarceration, which research has tied to poorer mental and physical health, disproportionately impacts minoritized communities (HHS, n.d.-c). In 2010, the incarceration rates for Latinx, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (NHPI), AIAN, and Black people were about 1.85, 2.26, 2.87, and 5.12 times the incarceration rate for White non-Latinx people, respectively (Prison Policy Initiative, n.d.). Black and Hispanic people account for 33 and 23 percent of the prison population despite representing only 12 and 16 percent of the U.S. adult population, respectively. Conversely, White people represent 63 percent of the adult population but only 30 percent of the prison population (Gramlich, 2020). Upon release, incarcerated individuals face significant barriers to accessing SDOH, as they must navigate “stigma, limited employment and housing opportunities, and the lack of a cohesive social network” (NASEM, 2017a, p. 160).

___________________

7 Pub. L. 106–297, 114 Stat. 1045 (Oct. 13, 2000) and Pub. L. 113–242, 128 Stat. 2860 (Dec. 18, 2014).

Incarceration also adversely affects children, families, and communities, as discussed previously. Mass incarceration has been tied to the “breakdown of educational opportunities, family structures, economic mobility, housing options, and neighborhood cohesion, especially in low-income communities of color” (NASEM, 2017a, p. 160). Heavily impacted communities also have higher rates of mental health disorders, such as major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2015). Children with an incarcerated parent are at higher risk for negative outcomes, such as poverty, homelessness, abuse, learning and developmental disabilities and delays, attention disorders, aggressive behavior, and criminal legal system involvement (HHS, n.d.-c). Adult family members (e.g., romantic partners and mothers) are also impacted via a variety of pathways, including loss of income, increased child care burden, stigma, and loss of social support, which increase the risk of poor physical and mental health (Lee and Wildeman, 2021; Wildeman and Lee, 2021).

Re-examination of federal policies regarding mandatory minimum sentences and long sentences could address the disproportionate impact of mass incarceration on minoritized communities (NRC, 2014). Data suggest that mass incarceration has had minimal effect on reducing crime and may actually result in more crime, as incarcerated individuals miss career opportunities and become part of shrunken social networks that consist primarily of other individuals engaged in criminal behavior and/or whose access to resources and opportunities have also been stymied due to incarceration (Roodman, 2017; Stemen, 2017), limiting their access to SDOH. A Brennan Center state-level analysis estimates that increased incarceration was only responsible for 0–7 percent of the decline in property crime from 1990 to 2013 and had no net effect on the decline in violent crime during this time (Roeder et al., 2015). A 2017 review estimated the impact of additional incarceration on crime at 0, noting that the deterrent effect of incarceration is mild or 0, while its incapacitation effect appears to be cancelled out by its crime-increasing “aftereffects” (Roodman, 2017). No consistent evidence indicates that punishment severity has a deterrent effect, contrary to arguments made to justify longer sentences and mandatory minimums. Furthermore, that both crime and recidivism rates decrease with age indicates that long sentences are an ineffective strategy for preventing crime via incapacitation and that, over long sentences, benefits to public safety are increasingly outweighed by the costs of incarceration (NRC, 2014; Roeder et al., 2015; Roodman, 2017). For the majority of crimes, criminal activity peaks from the mid-teens to early or mid-twenties, declining by more than half by the late twenties, across race and class. The median age range of people in federal prison is past this peak, at 36–40 years old (Mauer, 2018; NRC, 2014). Although addressing sentence length alone will not eliminate inequities in the mass

incarceration of Black, Latino/a, NHPI, and AIAN people, it is a meaningful step, with important implications for health inequities.

As noted, the committee was unable to comprehensively examine all policies under the violence, public safety, and criminal legal system umbrella; other areas merit examination to assess impacts on health equity—for example, violence against women and juvenile incarceration (see Box 7-1).

Conclusion 7-1: Community safety is critical for health and wellbeing. Racial and ethnic inequities in gun homicides and recent increases in firearm suicide among young Black adults suggest the need for more evidence-based policies that can prevent harm.

Conclusion 7-2: There are clear racial and ethnic inequities in policing. Improved data collection is needed to increase accountability, better understand the extent of these inequities, and determine which policy changes may help reduce them.

Conclusion 7-3: The criminal legal system is an important driver of health across the life course, as well as the health of communities and families. Racially and ethnically minoritized communities have experienced and continue to experience disproportionate contact with the criminal legal system. Evidence suggests that policies regarding mandatory minimum sentences, long sentences, and mass incarceration merit re-examination.

TRAUMA AND HEALING

In addition to issues related to violence, public safety, and the criminal legal system, historical traumas continue to affect the health and well-being of racially and ethnically minoritized populations and tribal communities. A deep literature illustrates how past trauma influences health—for example, on toxic stress (from adversity and intergenerational poverty) and allostatic load (McEwen and McEwen, 2017; NASEM, 2019a,b); posttraumatic stress disorder and racial trauma (Williams et al., 2021); the impact of discrimination on allostatic load in adults (Geronimus et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2021); how the evidence about intergenerational trauma could inform social policy (Njaka and Peacock, 2021); and race-related stress and trauma and emotional dysregulation in minoritized youth (Roach et al., 2023). This section explores how federal policy interventions that address the ongoing impact of historical traumas could advance health equity.

The repercussions of past actions, practices, policies, and laws continue to heavily affect health outcomes for minoritized racial, ethnic, and tribal communities today. Historical processes, such as colonialism, imperialism, genocide, slavery, and broken treaties, have inflicted lasting harm and undermined access to social, economic, and political resources and opportunities for Black, AIAN, NHPI, Latino/a, Asian, and Compact of Free Association (COFA) communities in both the past and present. These harms, resultant trauma, and lack of access to resources and opportunities have impeded the ability of these communities to reach their full potential for health, happiness, and overall well-being. For Black communities, significant trauma stems from a history of slavery, segregation, discrimination (NASEM, 2017a; Rothstein, 2017), racial terror and violence (e.g., lynching) (Equal Justice Initiative, 2020), systematic disinvestment in and destruction of Black communities (Lee et al., 2022; NASEM, 2017a; Rothstein, 2017), denial of voting and civil rights (National Archives, 2022a), forced sterilization

(Stern, 2020), and past and present policies such as voting literacy tests (National Archives, 2022a), redlining (Lee et al., 2022; NASEM, 2017a; Rothstein, 2017), aggressive policing (NASEM, 2017a), and criminal legal system policies, such as the convict leasing system (Equal Justice Initiative, 2013) and mandatory minimum sentences (NRC, 2014).

For AIAN communities, a history of forced assimilation, removal, extermination, forced sterilization, broken treaties, and intrusion on sovereignty has led to cultural loss, wealth depletion, and poor physical and mental health outcomes (Newland, 2022; Stern, 2020). The U.S. nuclear testing program on the Marshall Islands from 1946 to 1958 is another example. Today, the Marshallese people grapple with displacement, increased rates of cancer, and residual radiation in their land and water (Palafox, 2010; Rapaport and Nikolić Hughes, 2022). The U.S. government’s role in the overthrow of Hawaii’s monarchy in 1893, and eventual annexation of Hawaii as a territory and later state, is yet another example (Sai, 2018). These actions have had a lasting impact on mental and physical health and well-being and economic and cultural preservation for Native Hawaiians (Blaisdell, 2019). For Latino/a people, significant trauma stems from racial terror and violence (e.g., lynching) (Carrigan and Webb, 2003), forced sterilization (Novak et al., 2018), immigration detention, and immigration policies such as family separation (Hampton et al., 2021) and delousing at the U.S.–Mexico border (Stern, 1999) (see Box 7-2). The legacy of

colonialism in Puerto Rico and its status as a territory, which constrains its self-governance, congressional representation, and the federal support it can receive (Cheatham and Roy, 2022); Japanese American internment during World War II (National Archives, 2022b); and immigration policies, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act are additional examples (Department of State, n.d.; National Archives, 2023) (see Box 7-3).

How the United States might begin to rectify these harms and therefore advance health equity is a topic of ongoing discussion. Proposed solutions typically include a combination of official acknowledgement of harms,

financial redress, and structural redress (for example, policies that advance asset building to address intergenerational poverty). The Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which formally acknowledged the injustice of internment of Japanese American citizens and residents during World War II and provided monetary reparations to survivors and their heirs (National Archives, 2022b), and Public Law 103–150, wherein the federal government apologized for its role in overthrowing the Hawaiian monarchy, provide precedent for such federal action (Kana‘iaupuni and Malone, 2006). Redress provided by the federal government to Vietnam War veterans exposed to Agent Orange and survivors of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and their families provide additional precedent (CDC, 2022b; VA, 2022). Although acknowledgement of past injustice is a meaningful step, further action is needed to address the long-lasting harm of past actions and ultimately advance health equity.

Experts on racial and ethnic equity issues assert that inequities cannot be eliminated without changes that address historical wrongs and their ongoing impact on the structural and social determinants of health, and evidence increasingly supports this view, as this section discusses (Christopher, 2022; Galea, 2022; Welburn et al., 2022). Given the scope of this area of study, the committee was unable to comprehensively lay out the repercussions of past actions, practices, policies, and laws for all racially and ethnically minoritized populations. However, the following section details how some policies have led to lasting trauma and harm for minoritized communities and potential avenues for redress that scholars have proposed.

Trauma and Healing for Black Communities

Chapters 3–7 describe significant racial inequities in income, wealth, homeownership, educational quality and attainment, health care quality and access, health outcomes, neighborhood quality, policing, incarceration, and more. These inequities are part of the legacy of slavery, failed Reconstruction, segregation, redlining, the destruction of Black communities, and structural racism, which persists today (Du Bois, 1998; Equal Justice Initiative, 2020; Foner, 2014; Lee et al., 2022; NASEM, 2017a; Rothstein, 2017). Following the Civil War, the opportunity that the Reconstruction era provided to address structural racism and inequities, offer redress to formerly enslaved individuals, and chart a path toward racial equity went unfulfilled (Equal Justice Initiative, 2020). Although the 13th,8 14th,9 and 15th10 amendments abolished slavery, granted citizenship to formerly enslaved people, and granted Black men voting rights, respectively, the realization of fully equal citizenship, status, and opportunity for Black people was stymied by political opposition (Equal Justice Initiative, 2020). Other factors crucial for Black advancement and equality, such as economic growth, were obstructed by practices such as sharecropping and debt peonage (Du Bois, 1998; Equal Justice Initiative, 2020). Following the Compromise of 1877, Reconstruction efforts were abandoned by the federal government (Equal Justice Initiative, 2020). Black Codes, discriminatory laws passed at the state level, and Jim Crow laws restricted freedoms and reversed gains, such as Black voting rights (Equal Justice Initiative, 2020; National Geographic, 2022).

The persistence of racial inequity can be traced to the failure of Reconstruction (Du Bois, 1998; Equal Justice Initiative, 2020; Foner, 2014). For example, Darity and Mullen argue that these failures, starting with the reversal of Special Field Order No.15, which promised to provide formerly enslaved Black people with 40 acres of farmland and a mule after the end of the Civil War, helped create the Black-White wealth gap that persists today (Darity and Mullen, 2020). Beyond economic inequities, structural racism, slavery, the failure of Reconstruction, and policies that harmed Black communities have also paved the way for persistent inequities in health outcomes and other structural and social determinants of health (NASEM, 2017a). The influence of redlining is evident in not only present levels of wealth and rates of homeownership for Black families and individuals but also the built environment in Black communities, including lack of access to public transit and exposure to air pollution (Lane et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022; Townsley et al., 2021). Ongoing discrimination in the

___________________

8 U.S. Constitution, amend. 13, sec. 1.

health care system, which echoes past harms, such as the sterilization of Black women (Stern, 2020), the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (CDC, 2022b), and J. Marion Sims’ medical experimentation and abuse of Lucy, Anarcha, Betsey, and other enslaved Black women (Wailoo, 2018; Wall, 2006), has resulted in lingering mistrust of medicine, including early pandemic COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (Martin et al., 2022; Ober, 2022). The legacies of the Fugitive Slave Act, Black Codes, and Jim Crow laws are evident in today’s inequitable policing and criminal legal policies that have disproportionately removed Black individuals from their families and communities, which has economic and physical and mental health implications for them and their children, partners, and other family and has been tied to community disempowerment (Dyer et al., 2019; Mason, 2021; Maxwell and Solomon, 2018; National Geographic, 2022; Paul, 2016). In these varied ways, harmful policies and their legacy of structural racism have inflicted lasting trauma and discrimination on Black communities, impacting access to resources and opportunities critical for health and well-being.

For Black communities that have been destroyed by past actions, practices, policies, and laws and their legacy of structural racism, healing has been a challenging process. The aftermath of the 1921 Race Massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, is one example. This racial violence, which followed the arrest of a young Black man accused of attempting to rape a young White woman, is estimated to have killed 100–300 people in Tulsa’s Greenwood District, an affluent Black community then known as “Black Wall Street” (Monroe, 2021; Ross et al., 2001). Before the massacre, the district was a “symbol of Black prosperity” and entrepreneurship against the backdrop of Jim Crow America (Monroe, 2021). According to records analyzed by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, 1,256 homes were burned and an additional 215 looted. Businesses, churches, schools, a hospital, and a library—“virtually every other structure” in the neighborhood—were also destroyed (Ross et al., 2001, p. 12). The Tulsa Real Estate Exchange Commission reported that $1.5 million worth of property damage resulted from the massacre, one-third of this in the business district (Ross et al., 2001). Denial of insurance claims and lack of restitution from local, state, and federal government left Greenwood residents to rebuild on their own. These rebuilding efforts were successful, but during the 1960s–1980s, eminent domain, rezoning, highway construction, and redlining devastated the community once again (Perry et al., 2021).

Today, Tulsa’s Black community still struggles to heal from the violence and harmful policies it endured. A Brookings Institution analysis reveals that Tulsa’s predominately Black neighborhoods are no longer hubs for finance, insurance, and real estate jobs, and only 1.25 percent of Tulsa’s 20,000 businesses are Black owned (Perry et al., 2021). Displaced by the “urban renewal” policies of the 1960s to 1980s, many Black residents now

live in North Tulsa, where over one-third of people live in poverty, and where there are “fewer businesses (including grocers) and more abandoned or dilapidated buildings, as well as fewer banks and more payday lenders” (Perry et al., 2021). The 1921 race massacre and urban renewal policies also decreased Black homeownership in Tulsa and today, homes in Tulsa’s Black neighborhoods are valued at 40 percent less than similar homes in non-Black neighborhoods (Perry et al., 2021). Building off a 2018 study that estimated the total losses from the race massacre would be worth $200 million today (Messer et al., 2018), Brookings Institution found that a restitution package to recoup these losses could fully fund the education of 2,173–4,545 Black residents, purchase 4,187 median-priced homes in Black neighborhoods, or help start 6,421 Black-owned businesses (Perry et al., 2021). This type of event is not unique to Tulsa; the urban renewal policies of the 1960s–1980s affected Black communities all across U.S. cities (Fullilove, 2001), and incidents similar to the massacre in Tulsa also devastated Black communities in Wilmington, North Carolina, Rosewood, Florida, and other cities (González-Tennant, 2023; Wilmington Race Riot Commission, 2006).

Although past actions, practices, policies, and laws have inflicted lasting trauma on Black communities and undermined access to social, economic, and political resources and opportunity, this history is also characterized by Black perseverance and resistance to injustice, from slavery, to Reconstruction, to the Civil Rights Movement, to the present (American Social History Project, n.d.-a). Uprisings by enslaved people and historical documents, such as accounts from formerly enslaved individuals and advertisements offering rewards for the return of those who escaped enslavement, chronicle such resistance (American Social History Project, n.d.-b). During Reconstruction, Black activists founded Equal Rights Leagues, fought for equal citizenship, opportunity, and suffrage, and against Black Codes (NMAAHC, n.d.; Villanova University, n.d.). The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s–1960s, and the racial justice protests that followed the killing of George Floyd in 2020, offer additional examples of how Black organizing and resistance has played a role in the movement toward healing and racial equity for Black communities (Library of Congress, n.d.; McLaughlin, 2020).

Evidence demonstrates that redress for harms inflicted on Black communities would improve health and other aspects of well-being. As discussed in Chapter 3, significant racial inequities in economic stability, particularly wealth, stem from past policies. Given the systemic nature of inequities in income and wealth, and their persistence over the last 30 years, they will not resolve without intervention. A recent analysis from RAND explores several strategies and amounts (e.g., equal allocations to all Black households, equal allocations to all households, targeted allocations to all households, and targeted allocations to Black households) for

wealth allocation policies to address inequities and their projected impact on the racial wealth gap. The analysis considers wealth allocations funded through the sale of sovereign bonds rather than wealth reallocation to some households funded by taxing others. Using data from the Survey of Consumer Finances, the analysis finds that $500 billion, $1.5 trillion, or $3 trillion equally allocated to all Black households could reduce median wealth disparity by 17, 50, or 100 percent, respectively (Welburn et al., 2022). It also finds that policies targeting $760 billion or $1.6 trillion to Black households at the lower end of the wealth distribution could halve or eliminate the median wealth disparity, respectively (Welburn et al., 2022).

A 2021 study showed that a restitutive wealth redistribution program for Black individuals would have decreased COVID-19 risk for recipients, and the resultant decrease in transmission would benefit the broader population (Richardson et al., 2021). The authors hypothesized that several mechanisms might be responsible for this effect: a narrowed racial wealth gap, differences in built environment that increase the ability to social distance, a more equitable racial distribution of frontline workers, and decreased race-based allostatic load (Richardson et al., 2021). Additionally, a recent study by Himmelstein et al. (2022) aimed to determine what share of the Black–White gap in longevity could be explained by differences in wealth and how much reparations payments that aimed to close this wealth gap might reduce differences in that longevity gap. In models adjusting for income or educational attainment alone, racial gaps in longevity persisted. However, adjusting for differences in wealth eliminated differences in survival by race, and simulations indicated that payments that aimed to decrease the mean racial wealth gap were associated with longevity gap reductions of 65.0–102.5 percent (Himmelstein et al., 2022). As discussed in prior chapters, decades of research have established how social and structural factors, such as wealth, impact health outcomes and have created racial and ethnic inequities (Chapter 1 and 2). Critically, wealth enables access to other SDOH and enables individuals to engage in health-promoting behaviors (Chapter 3). Welburn et al. (2022), Richardson et al. (2021), and Himmelstein et al. (2022) provide evidence that targeting wealth could be an effective strategy to address inequities and redress for past actions, practices, policies, and laws that continue to harm Black communities. Such policies may also apply to other racially and ethnically minoritized populations, who also experience inequities in wealth due to structural racism.

Similar policies to redress harm caused to Black communities are being explored and implemented at the state and local levels. In Evanston, Illinois, for example, the Reparations Restorative Housing Program was designed to address the city’s history of discriminatory housing policies and practices. With an initial budget of $400,000, it has provided payments of up to $25,000 for 16 Black residents to put toward homeownership,

home improvement, or mortgage assistance. It is the first initiative of the reparations fund that Evanston established in 2019 and was implemented after the city’s Equity and Empowerment Commission concluded that in Evanston, the strongest case (that is, the most politically feasible and justifiable) for reparations was around housing (City of Evanston, n.d.; Richardson, 2021; Robinson and Thompson, 2021).

In California, Assembly Bill 3121 established the Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans, with a Special Consideration for African Americans Who Are Descendants of Persons Enslaved in the United States.11 The task force is meant to recommend appropriate redress based on its findings. Through its deliberations thus far, the task force has identified housing, the dispossession and destruction of Black-owned property and businesses, education, mass incarceration and policing, and health, among others, as areas of harm. It continues to deliberate on this and other aspects of the proposals for reparations it will develop and policy changes it may recommend (Austin and Har, 2022; California Task Force, 2022).

In 2010, North Carolina established the Office of Justice for Sterilization Victims to address the injustices carried out by the North Carolina Eugenics Board program (NCDOA, n.d.). North Carolina was not the only state to forcibly sterilize people deemed “unfit” for reproduction. In 1935, 27 states had laws that allowed for forced sterilization of people who were deemed mentally unfit, were on welfare, or had genetic defects. Black, Latino/a, and AIAN women were overrepresented among victims of state programs and federally funded “family planning” efforts (Novak et al., 2018; Stern, 2020; Washington, 2006). The North Carolina Eugenics Board program sterilized almost 7,600 people between 1929 and 1974. Many of them were low income or had a disability, and 40 percent were racially or ethnically minoritized (Mennel, 2014; NCDOA, 2014). Although North Carolina’s Office of Justice for Sterilization Victims provided compensation in 2014, the process was not without flaws. Residents whose forced sterilizations were approved by judges and social workers but not signed off on by the Eugenics Board found themselves ineligible for compensation based on this technicality (Mennel, 2014).

Efforts such as those by North Carolina, California, and Evanston are also underway in Asheville, North Carolina (The City of Asheville, 2023); Providence, Rhode Island (Providence Municipal Reparations Comission, 2022); Boston, Massachusetts (City of Boston, 2023); Cambridge, Massachusetts (Kingdollar, 2021); and other cities. Although it may be difficult to gain broad support for similar efforts at the federal level, this is one avenue through which the federal government could begin to address

___________________

11 A.B. 3121 (CA 2020).

the trauma it has caused Black individuals and communities. H.R.40, which would establish the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans, was introduced in the House of Representatives in 2021 but has yet to advance through Congress.12 It could serve a similar role as Evanston’s equity commission and California’s task force in exploring possibilities for redress, to lift impacted communities out of poverty and harmful living conditions, provide access to quality education, and address other social needs to mitigate or eliminate health inequities.

Challenges to the use of affirmative action in college admissions mounted in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard College13 and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina14 (see Chapter 4) suggest that it may be difficult to gain broad support for race-based reparations-like policies compared to those that are targeted more specifically. North Carolina’s Office of Justice for Sterilization Victims, for example, targets individuals who were directly affected, and California’s task force, though not excluding others, has a special consideration for Black descendants of people who were enslaved in the United States. Reparations-like policies may gain broader support if they are structured to target particular communities based on ancestry or poverty, rather than being race-based. However, structural racism affects all Black people in the United States today, regardless of ancestry.

Trauma and Healing for American Indian and Alaska Native Communities

AIAN tribes have a unique legal relationship with the United States, which includes hundreds of treaties that mandate support for economic well-being, public safety, education, and health care (U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 2018) (see Chapter 2 for more information). Despite numerous challenges, courts have consistently upheld these rights. For example, in Rosebud Sioux Tribe v. United States, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the right of Tribal Nations to physician-directed health care.15 However, despite this legal acknowledgment, the Indian Health Service (IHS) remains chronically underfunded (see Chapter 5) (Tribal Budget Formulation Workgroup, 2022). Additionally, an insufficient federal response to the crisis of missing and murdered AIAN women and girls and inadequate collection of and access to related data perpetuate this crisis (Urban Indian

___________________

12 H.R. 40, 117th Congress (2021).

13 600 U.S. ____ (2023).

14 600 U.S. ____ (2023).

15 Rosebud Sioux Tribe v. United States, 9 F.4th 1018 (8th Circ. 2021).

Health Institute, 2018a), economic deprivation of urban and rural tribal communities has built a system of pervasive poverty (Davis et al., 2016), and a lack of quality educational opportunities has resulted in low high school graduation and college enrollment rates (Keith et al., 2016). A lack of data related to inequities and resiliencies for AIAN people, discussed more extensively in Chapter 2, also directly impacts the allocation of resources legally owed through treaty and trust responsibility.

In addition to this failure to honor treaty obligations, past and present federal actions, practices, policies, and laws, such as forced assimilation, territorial dispossession, extermination, and intrusion on sovereignty, have also resulted in ongoing trauma and negatively affected health and well-being for AIAN people. The legacy of Indian boarding schools is one example. From 1819 to 1869, schools established and supported by federal policies removed AIAN and Native Hawaiian children from their families and incarcerated them in “educational” institutions as a method of forced cultural assimilation. Sexual, physical, and emotional abuse were common, as were school cemeteries for an estimated hundreds of children who died while in attendance (Newland, 2022). In addition to this cultural loss, abuse, and death, these experiences have contributed to ongoing trauma and effects on the health and well-being of AIAN and Native Hawaiian communities. A study by Running Bear found that various aspects of the Indian boarding school experience, including limited family contact, punishment for use of American Indian language, and prohibition on practicing American Indian culture and traditions, were independently linked to poorer physical health in adulthood (Running Bear et al., 2018). Running Bear et al. (2019) found that now-adult attendees of Indian boarding schools were more likely to have cancer, tuberculosis, high cholesterol, diabetes, anemia, arthritis, and gallbladder disease compared to adult nonattendees. Indian boarding schools have also been linked with increased risk for mental health outcomes, such as substance use disorders, suicidal ideation, and attempted suicide in now-adult attendees and anxiety, PTSD, and suicidal ideation in people raised by attendees (Evans-Campbell et al., 2012). In June 2021, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland issued a memorandum to the Department of the Interior that launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. In consultation with impacted communities, the initiative collected data and reviewed records to document the scope of the system and its effects. This initiative provides a positive example of federal action to address past harms and improve equity that can be built upon. In May 2022, the department released the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report, outlining its activities and recommending, among other actions, continued investigation, the advancement of Native language revitalization, and research into the health effects of the boarding school system on AIAN and Native Hawaiian individuals and communities (Newland, 2022).

The removal of AIAN and Native Hawaiian children from their communities occurred in parallel with territorial dispossession (Newland, 2022). The forced removal and relocation of AIAN from their traditional lands was embedded into federal policy as a means to handle the “Indian problem” and ensure land was available for encroaching European settlers (Kiel, 2017; Moss, 2019). Although precise estimates as to the scope of territorial dispossession and forced migration have been largely lacking, a recent analysis demonstrates a “near total” reduction in aggregate land, with 42.1 percent of tribes with historical lands having no federally or state-recognized land base (Farrell et al., 2021). For tribes that do, their lands average 2.6 percent of the estimated size of their historical lands. Estimates of migration distances averaged 148 miles, with a maximum of 1,724 miles (Farrell et al., 2021). Although data on the mental and physical health impacts of territorial dispossession and forced migration have been limited, studies suggest that AIAN people think regularly about broken treaties and historical loss of land, language, culture, traditional spiritual ways, and family ties from relocation or boarding schools and experience associated sadness, anger, anxiety, and shame (Urban Indian Health Institute, 2018b; Whitbeck et al., 2004).

Decades of tribal advocacy have focused on restoring land that was taken. In 2020, protest by AIAN activists at the Lakota sacred site known as Mount Rushmore birthed NDN Collective’s LANDBACK campaign, continuing the legacy of tribal advocacy and demanding restoration of land and land management (NDN Collective, 2020a,b). Landback efforts have seen success (Thompson, 2020); however, much remains to be done to fully undo historical harm and restore land to its original owners.16 Ample opportunities exist for federal agencies and Congress to restore ancestral homelands to AIAN tribes and address the harmful impacts of territorial dispossession and forced migration. Although laws that reduced the size of reservations took this land for the purpose of private ownership and settlement by non-AIAN people, 140 years later, one-third of the land that had been part of reservations is managed by six federal agencies. One-quarter of land within 10 miles of present-day reservations is managed by one of six federal agencies. These lands are strong candidates for federal landback efforts (Taylor and Jorgensen, 2022). Another option for addressing the impacts of territorial dispossession is establishing “first right of refusal” for Tribal Nations on sales of federal lands in their ancestral territories. This potential solution was proposed in H.R. 8108, the Advancing Tribal Parity

___________________

16 In federal Indian policy, it is understood that the original owners of land are the original peoples inhabiting and stewarding the lands under the auspices of inherent sovereignty for 10 to 20,000 years pre-European contact.

on Public Land Act, which was introduced in the House in 2022.17 The California Public Utilities Commission implemented a similar policy of first right of refusal that applies to the disposition of land by investor-owned utilities (California Public Utilities Commission, n.d.).

In addition to restoration of land, ensuring access for AIAN communities to federal lands and waters for traditional hunting, fishing, and gathering activities and costewardship is another avenue to address ongoing historical trauma and emotional distress related to loss of land and traditional ways (Gordon, 2022; Whitbeck et al., 2004). Alaska Natives, for example, depend on hunting, fishing, and gathering for subsistence (Gordon, 2022). Territorial dispossession and the ecological impacts of climate change on Alaskan flora and fauna are threatening their traditional ways of life and life-sustaining foods (Green et al., 2021). Mandating access to federal lands and waters for Alaska Natives to maintain subsistence lifestyles could thus help address not only historical trauma but also the impact of climate change on health (Green et al., 2021). Expanding CLEAR3018 to federal, state, and tribal lands to increase their accessibility for hunting and gathering rights is one strategy that could help achieve this.

An association between 27 tribes and Yellowstone National Park provides one example of how costewardship can address the trauma of loss of land and traditional ways. Formed with just a few tribes in 1996, this association creates the opportunity for tribes to participate in resource management and decision making, conduct ceremonies and other events in the park, collect plants and minerals for traditional uses, and hunt bison outside of the park in coordination with park officials (NPS, 2022). Holding agencies accountable to Joint Secretarial Order 3403 between the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture could help to increase such opportunities. Joint Secretarial Order 3403 directs the departments’ bureaus and offices to do the following:

- Ensure that all decisions by the departments related to federal stewardship of federal lands, waters, and wildlife under their jurisdiction include consideration of how to safeguard the interests of any Indian tribes such decisions may affect;

- Make agreements with Indian tribes to collaborate in the costewardship of federal lands and waters under the departments’ jurisdiction, including for wildlife and its habitat;

___________________

17 H.R. 8108, 117th Congress (2022).

18 CLEAR30 (the Clean Lakes, Estuaries, And Rivers initiative) is an opportunity for landowners and agricultural producers implementing water quality practices through the Conservation Reserve Program to receive incentives by enrolling in 30-year contracts, strengthening and extending the implementation of these existing water quality practices (USDA, 2021).

- Identify and support tribal opportunities to consolidate tribal homelands and empower tribal stewardship of those resources;

- Complete a preliminary legal review of current land, water, and wildlife treaty responsibilities and authorities that can support costewardship and tribal stewardship within 180 days and finalize the legal review within one year of the date of this order; and

- Issue a report within one year of this order, and each year thereafter, on actions taken to fulfill the purpose of this order (Haaland and Vilsack, 2021, p. 2).

Thirteen costewardship agreements have followed the order’s signing, per the first annual report released in November 2022, and the Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have also released guidance to improve costewardship (DOI, 2022).

Incorporating Indigenous knowledge into policies, programs, and decision making is another avenue to address the health inequity that past and present federal actions, practices, policies, and laws have wrought and uphold trust responsibility at the federal, state, and local levels. Scholars have defined Indigenous knowledge as “diverse knowledge preferences and practices of Indigenous peoples, whether modern or traditional, but even modern Indigenous knowledges typically trace some continuity with the Indigenous past” (Gone, forthcoming, p. 20). However, efforts to recognize and incorporate Indigenous knowledge need to consider the unique cultural differences of each Tribal Nation and urban AIAN community and not take a one-size-fits-all approach. Despite overwhelming odds, tribal communities have survived and, in many instances, thrived when given the opportunity and resources to apply Indigenous knowledge systems to address inequities. For example, diabetes has long been an issue within AIAN communities; however, despite a disproportionately high diabetes prevalence, that rate has not increased since 2011. This is attributed to the Special Diabetes Program for Indians, a national program funding urban and rural tribal communities whose programing incorporated local and regional cultural traditions and teachings into Western evidenced-based diabetes prevention programing (ASPE, 2019). A study found that after the implementation of this program among AIAN adults, age-adjusted diabetes-related end-stage renal disease rates per 100,000 population decreased 54 percent, and overall cost savings for this program was up to $520 million (ASPE, 2019; Bullock et al., 2017). However, despite overwhelming data supporting its impact, tribal leaders are consistently forced to fight and advocate to Congress for minimal funding appropriations to keep the program operational, illustrating the lack of investment in AIAN knowledge systems and failure by the federal government to uphold treaty rights. In late 2022, the Biden Administration released the first-of-its-kind Indigenous Knowledge Guidance for federal agencies.

This document provides guidance on the incorporation of Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge in federal scientific and policy processes, highlighting an opportunity to advance equity for AIAN communities, with an accompanying memorandum on implementation (The White House OSTP and Council on Environmental Quality, 2022a,b). Drawing upon decades of feedback from tribes, tribal leaders, tribal and urban Indian organizations, and community members, this guidance offers a plan to ensure the appropriate application of Indigenous knowledge across federal agencies (The White House, 2022b). Although these efforts are commendable and necessary to repair the harm inflicted on AIAN communities, to address long-standing inequities, they must be embedded in policy and not depend on who is in office.

Health inequities and historical trauma in AIAN communities are directly tied to the political status of Tribal Nations and past and present federal actions, practices, policies, and laws, such as forced assimilation, territorial dispossession, extermination, intrusion on sovereignty, and the failure to uphold treaty and trust responsibilities. Given its scope, this report is unable to expansively review all strategies to address these wrongs. In addition to the policies covered above, other avenues to address historical trauma and improve health equity for AIAN communities include permanently providing advanced appropriations to IHS (National Indian Health Board, n.d.) (see Chapters 5 and 8), improving data collection for AIAN communities (Erickson et al., 2021; Friedman et al., 2023) (see Chapters 2 and 8), properly implementing Savanna’s Act19 and Not Invisible Act,20 and other strategies to address the maze of injustice related to missing and murdered AIAN women, girls, and people (GAO, 2021). By addressing historical trauma through strategies such as restoring land, expanding costewardship opportunities, and grappling with the legacy of the Federal Indian boarding school system, and by upholding treaty and trust responsibilities to provide for tribes’ well-being, the federal government can begin to address the legacy of harm to AIAN communities, improving access to health care and life-sustaining food, supporting restoration of traditional ways of life, improving mental health outcomes related to past losses, and addressing other community needs to mitigate or eliminate health inequities.

Trauma and Healing for Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Communities

Federal actions, practices, policies, and laws in Hawaii that have led to lasting harm include the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy and annexation of the Hawaiian Islands, driven by business and

___________________

19 25 U.S.C. § 5701 et seq.

20 Pub. L. 116–166, 134 Stat. 766 (Oct. 10, 2020).

agricultural interests, and U.S. military deployment of personnel and weapons (Blaisdell, 2019; Sai, 2018). In 1921, Congress passed the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act,21 which created the term “native Hawaiian” to refer to “any descendant of not less than one-half part of the blood of the races inhabiting the Hawaiian Islands previous to 1778” (referring to the arrival of Captain Cook) and defined “the United States as trustee and ‘native Hawaiians’ as wards” (Blaisdell, 2019, p. 256). Since that time, the U.S. military has established an extensive network of bases as part of its Pacific strategic defense framework.

Western colonialism in Hawaii introduced diseases and violence; displaced people and dispossessed them of their land; ended self-government; degraded the quality of land, water, and air (Kana‘iaupuni and Malone, 2006; Levy, 1975; MacKenzie et al., 2007; Martin et al., 1996); and created cultural conflict, physiological stress, and trauma (Kaholokula et al., 2012; Liu and Alameda, 2011; Pokhrel and Herzog, 2014). Although, in 1993, Public Law 103–150 acknowledged that “the indigenous Hawaiian people never directly relinquished their claims to their inherent sovereignty,” no action has been taken to reinstate this sovereignty (Kana‘iaupuni and Malone, 2006; The Learning Network, 2012; Sai, 2018; University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, n.d.).22 As discussed in Chapter 2, lack of sufficient data collection has also impacted NHPI communities. Until 1997, Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders were aggregated in the Asian or Pacific Islander category, which masked a high level of heterogeneity in outcomes and made it difficult to characterize the needs of NHPI communities, let alone analyze data for Native Hawaiians specifically (OMB, 1997). More accurate and complete data allowed a clearer picture of the health inequities experienced by Native Hawaiians, ranging from chronic conditions to mental illness (Liu and Alameda, 2011). However, data for the NHPI population are still often not separately reported or sometimes combined with the Asian population, rendering these populations invisible or masking inequities (AAPI Data and National Council of Asian Pacific Americans, 2022; OMB, 1997; Panapasa et al., 2011).

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the COFA that governs U.S. relations to the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). In March 2023, the United States and RMI “signed a memorandum of understanding on a new Compact of Free Association agreement that will govern relations between the two nations for the next 20 years,” once the final compact is approved by Congress (Kimball, 2023). The health inequities of the Marshallese people have been shaped by layers of U.S. federal

___________________

21 July 9, 1921, ch. 42, 42 Stat. 108.

22 Pub. L. 103–150, 107 Stat. 1510 (Nov. 23, 1993).

policies that have displaced them, appropriated their lands, and exposed them to health-harming environmental hazards (including nuclear tests). The health effects of nuclear testing radiation and in-utero effects have led to higher levels of certain cancers (Pineda et al., 2023). Moreover, “increased levels of background radiation may continue to pose future problems to the ecosystem and people living in adjacent areas” and “[y] ears of trauma associated with radiation testing has led to generations of perceived radiation-related birth defects, cancers, and other chronic disease, which may explain in part why Pacific Islanders are particularly at risk of refusing potentially curative radiation therapy in the U.S.” (Pineda et al., 2023).

For Marshallese who have moved to the United States seeking safety from radiation and the effects of climate change, relocation has created new challenges. For example, they face issues ranging from racism to administrative hurdles to obtaining essential benefits, such as health care and unemployment. Climate change will likely exacerbate the movement of Marshallese and other Pacific Islands people to the United States, and it will be important to examine and address structural and systemic factors likely to continue to play a role in worsening health inequities (Jetñil-Kijiner and Heine, 2020).

Conclusion 7-4: Generations of Black, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, Latino/a, and Asian communities have been negatively affected by past actions, practices, policies, and laws that inflicted lasting harm and undermined access to social, economic, and political resources and opportunities, contributing to current racial and ethnic health inequities. There is a need to continue to study and address the impacts of historical and contemporaneous laws and policies that sustain racial inequity.

CIVIC ENGAGEMENT AND BELONGING

Systems of civic engagement and belonging are critical to the wellbeing of individuals, families, and entire communities. The path to racial, ethnic, and tribal health equity requires enlarging the contours of civic life. Specifically, it is important to expand the circle of who feels they belong—leaving no one behind—and strengthen the civic muscle necessary to establish systems that are built for everyone to thrive together in a multiracial, multicultural society. Cultivating belonging is distinct from assimilation; such efforts value each individual’s and community’s unique culture and knowledge system and recognize that valuing these differences is an essential part of achieving equity.

Systems of civic engagement and belonging involve critical components of civic infrastructure (including the presence and strength of civil society institutions, such as faith-based groups, community-serving news media, and well-resourced educational institutions, cultural organizations, governing institutions, and electoral infrastructure). These systems also involve processes of belonging and engagement (such as civic association, freedom from stigma and discrimination, access to information and opportunities to participate in voting, volunteering, and public work, and access to—and making contributions to—arts, culture, and spiritual life).

In 2022, the federal government, through various agencies, published a whole-of-government plan to enhance well-being and equity: the Federal Plan for Equitable Long-Term Recovery and Resilience (ELTRR). It placed “belonging and civic muscle” as the core of seven vital conditions for health and well-being (see Figure 7-2), building on a broad coalition effort during the pandemic called the “Thriving Together Springboard” (Milstein et al., 2023; Thriving Together, n.d.). That component crystallizes a rich history of eclectic efforts to strengthen connections and build shared power with a focus on civic agency, civic capacity, deliberative democracy, public participation, public work, constructive nonviolence, and collaborative problem solving (Thriving Together, n.d.). It also builds on a large body of work that connects civic engagement, feelings of efficacy and belonging, and various aspects of health and well-being (HHS, n.d.-b; NASEM, 2023; University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2023).

It is a universal human need to feel loved and valued by others and to feel a sense of belonging to one’s community, organization, nation, and culture (Milstein et al., 2020). Belonging instills a feeling of connection to others and to the world. A lack of belonging is tied a multitude of negative outcomes, including loneliness, isolation, anxiety, depression, substance use disorder, and suicide, and greater risk of chronic illness, infectious disease, environmental hazards, and violence (Murthy, 2020; NASEM, 2020). True belonging does not entail only passive membership in a group, but action, “typically marked by the ability to do productive work and be accountable for both contributions and consequences” (Milstein et al., 2020, p. 49). Belonging bestows both the privilege of receiving resources from society and also the responsibility to add value to society (this value can take many forms, including economic, civic, and spiritual value). The literature on human development indicates that humans develop a strong “need to contribute” by adolescence in part because of the benefit that contribution confers to the contributor (Fuligni, 2019). This balance of autonomy and interdependence is critical for human agency and human dignity (Arendt, 1958; Milstein et al., 2020).

Similarly, civic capacity and civic muscle relate to health equity and community well-being through individual, social, and institutional capacities,

SOURCE: Federal Plan for Equitable Long-Term Recovery and Resilience ELTRR Interagency Workgroup, 2022.

activities, and processes. Civic capacity is “a stock that may expand or erode, depending on how people relate to each other, both directly and through institutions. Civic muscle explains how diverse people can work together around common values” (Milstein et al., 2020, p. 49). It is a way of weaving vested interests, “multiplying energy, and doing work that no one person or organization could do alone” (Milstein et al., 2020, p. 49). Norris (2019) describes the importance of belonging and civic muscle by explaining that “people are healthier when they are connected to others”—social networks confer resilience, support mental and emotional well-being, and encourage positive health behaviors (Norris, 2019, p. 80). Additionally, cohesive communities work together to create and ensure conditions that support health and well-being (Norris, 2019).

Civic Engagement and Belonging Are Important for Health Equity

Civic Engagement has Powerful Effects on Population Health and Well-being, Including Health Equity

An extensive analysis conducted by RAND concluded that increases in civic engagement are associated with increases in physical and mental health and well-being (Nelson et al., 2019). Likewise, communities facing fewer barriers to civic engagement are more likely to have their needs met than those with limited access or greater barriers (Ballard, 2019; Center for Social Innovation and University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2021). Civic engagement among youth in particular is important for democracy and youth development; this has key implications for equity, given that racially and ethnically minoritized youth and those from immigrant and lower socioeconomic backgrounds have less access to these opportunities (Ballard, 2019).

Furthermore, a sweeping examination on the psychology of citizenship and civic engagement concluded that civic engagement in community organizations makes them “more representative, inclusive, accountable, and effective” and leads to the provision of “more appropriate, accessible, and better utilized” services (Pancer, 2015). It also found that greater neighborhood-level civic engagement is associated with a stronger sense of community, better leadership, lower crime rates, and happier, healthier citizens. States and countries with high civic participation have better physical and mental health and lower rates of disease, suicide, and crime. Research also indicates that they are more economically successful, have better-educated children, and are better governed (Pancer, 2015).

Better-connected Networks and Inclusionary Processes Tend to Produce Better Outcomes