Federal Policy to Advance Racial, Ethnic, and Tribal Health Equity (2023)

Chapter: 4 Education Access and Quality

4

Education Access and Quality

This chapter discusses key issues in education access and quality, beginning with an overview of how federal laws and policies shape U.S. education and especially reflecting on the linkages between equity and quality. Key policies include the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), the Higher Education Act (HEA), Section 504 of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. The history of racism and social and educational segregation have affected the quality of education afforded to children who have been racially and ethnically minoritized. Chapters 2 and 7 discuss the federal government boarding schools that mistreated and traumatized American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) and Native Hawaiian children who were forcibly removed from their families, and this chapter discusses racially segregated schools separated by stark gaps in all kinds of resources. Unfortunately, education inequities persist. A 2013 report from the Equity and Excellence Commission, a federal advisory committee of the U.S. Department of Education (DOE), succinctly summarized the state of U.S. education in a way that still resonates a decade later (DOE, 2013):

Our education system, legally desegregated more than a half century ago, is ever more segregated by wealth and income, and often again by race. Ten million students in America’s poorest communities—and millions more African American, Latino, Asian American, Pacific Islander, American Indian and Alaska Native students who are not poor—are having their lives unjustly and irredeemably blighted by a system that consigns

them to the lowest-performing teachers, the most run-down facilities, and academic expectations and opportunities considerably lower than what we expect of other students. These vestiges of segregation, discrimination and inequality are unfinished business for our nation.

In addition to reviewing key policies, this chapter discusses the evidence on federal approaches and the interface with states on issues of funding, teacher quality, social supports and social context, and other key aspects of the educational experience, with additional discussion of aspects relevant to higher education. Although the federal government plays a large role in constructing frameworks for equitable treatment of all students and equitable access to educational opportunities, the role of states is preeminent and may outweigh federal policies and guidance, including on matters of education equity, such as in funding. The federal role also has fluctuated over time, with periods of robust engagement followed by times of more limited guidance to or engagement with states and local school districts. Although a great deal of flexibility and responsiveness to unique local circumstances is needed, furthering education equity (and by extension, health equity) undoubtedly requires federal leadership.

INTRODUCTION

The National Academies report Monitoring Educational Equity found that

The history of constitutional amendments, U.S. Supreme Court decisions, and federal, state, and local legislation and policies indicates: (1) a recognition that population groups—such as racial and ethnic minorities, children living in low-income families, children who are not proficient in English, and children with disabilities—have experienced significant barriers to educational attainment; and (2) an expressed intent to remove barriers to education for all students. (NASEM, 2019b, p. 2)

That report’s authoring committee concluded that “educational equity requires that educational opportunity be calibrated to need, which may include additional and tailored resources and supports to create conditions of true educational opportunity” (NASEM, 2019b, p. 2).

Federal law, including case law, shapes several important aspects of education, with broad consideration of equity, but in practice, the limitations are evident. In 1954, the milestone Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka1 found state-sanctioned segregation of public schools unconstitutional because it violated the 14th amendment (equal protection

___________________

1 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

under the law). However, the practice of “separate but equal” endorsed by Plessy v. Ferguson2 in 1896 persisted in many settings and policies (The Century Foundation, 2018; The Equity Collaborative, n.d.).

Brown was followed by enactment of some state laws that aimed to prolong educational segregation (see, for example, the Massive Resistance effort organized by Southern lawmakers) (NAACP Legal Defense Fund, 2023). The 1964 Civil Rights Act provided an even more expansive framework for prohibiting discrimination and was followed 2 years later by the Equality of Educational Opportunity Study (the Coleman Report), which concluded that Black students benefited from attending integrated schools and introduced busing as a strategy for desegregation (The Equity Collaborative, n.d.).

In 1965, when the federal government stepped in with direct investments to the states via Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) to provide compensatory funding to states with a high proportion of poor children, it was due to a lack of states’ attention or willingness to address the unequal experiences poor and minority students faced in state public education systems. (The Century Foundation, 2018)

School segregation is not a relic of the past; it has continued to produce unequal learning opportunities (Orfield et al., 2014) and is still being addressed in case law and state ballot measures (e.g., in California during the 1990s) (The Equity Collaborative, n.d.).

Two major amendments of the ESEA focused on closing achievement gaps. The No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act (2001) considerably expanded the federal role in education; it included provisions that focused on state and local strategies to support “students from economically disadvantaged families, students from racial and ethnic minority groups, and students with disabilities” (20 U.S.C. 6623) (Congress.gov, 2001) and “support of local educational agencies that are implementing court-ordered desegregation plans and local educational agencies that are voluntarily seeking to foster meaningful interaction among students of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, beginning at the earliest stage of such students’ education” (20 U.S.C. 7231) (Congress.gov, 2001). NCLB also called for disaggregating student performance data by race, disability, English proficiency, and income level (NASEM, 2019b; The Century Foundation, 2018).

In 2015, ESSA reauthorized the 50-year-old ESEA and added provisions that required a new set of high academic standards, protections for high-need students, and the nurturing of local, evidence-based

___________________

2 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

interventions, while allowing flexibility for states (DOE, n.d.-b). Unfortunately, although ESSA provided an opportunity for states and school districts to include racial and socioeconomic diversity in their improvement plans, the emphasis on flexibility also allowed states to avoid more robust efforts to further equity. In the initial round of ESSA plans, only one state included a diversity component (The National Coalition on School Diversity, 2020).

The repercussions from an education policy aimed at AIAN people—assimilation in federal Indian Law—are still felt today. During this period, children were removed from their homes, families, and cultures to attend schools far from home (Newland, 2022). The first and most infamous was the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania; from 1879 until 1918, over 10,000 children from 140 tribes attended and were forced to assimilate (National Park Service, 2020). Children were often emotionally, physically, and sexually abused, and many died as a result (National Park Service, 2020; Newland, 2022). Many never saw their families again, and mass graves have recently been identified at these “school” sites (Newland, 2022). Studies show that survivors of these schools are more likely to have cancer, tuberculosis, high cholesterol, diabetes, anemia, arthritis, gallbladder disease, and negative mental health outcomes compared to adult nonattendees (Evans-Campbell et al., 2012; Running Bear et al., 2018, 2019) (see Chapter 7).

The Linkages Between Education and Health

Education is a powerful force for advancing health equity. The quantity and quality of education interacts in important ways with other social determinants of health as well. The skills developed in schools—whether measured by standardized tests or a broader range of social and emotional skills that can be nurtured and taught in schools, such as persistence, sociability, creativity, and motivation—influence educational attainment, economic outcomes, residential neighborhood characteristics, and even the quality of interpersonal relationships (NASEM, 2019d; Schrag, 2014). Each of these in turn impact health status. An extensive body of evidence links education and health outcomes, such as self-rated health, infant mortality, and life expectancy (Schrag, 2014).

Educational attainment impacts communities across generations as well—parental attainment is linked to child health and well-being (Evans et al., 2021). Although the literature linking education and health is robust, some debate exists about to what extent the relationship is causal (Baker et al., 2011; Fujiwara and Kawachi, 2009; Grossman, 2015). In addition, it is bidirectional: education impacts health and health influences educational outcomes (NASEM, 2017).

Education can affect health through many pathways. Those with higher levels of educational attainment, on average, have higher incomes and better employment characteristics, such as employment that is more stable, have healthier working conditions, and are more likely to be offered employment-based benefits, such as paid leave and health insurance (Egerter et al., 2008). Higher attainment also predicts greater financial wealth (Wolla and Sullivan, 2017).

Education can also improve health knowledge, influence adoption of healthy behaviors, and enable people to make better-informed choices about receiving and managing medical care (Egerter et al., 2009). Education is also associated with psychological and social factors, including sense of control and social support, that affect health. A strong education system that works for everyone is fundamental to achieving health and social equity.

Responsibility for education policy rests largely with state and local governments, with the federal government primarily filling gaps in state and local funding, disseminating emerging knowledge, and helping to strengthen the effectiveness of education for all students (DOE, 2021a). Although its role in education is somewhat indirect, it has some powerful levers for influencing the educational inequities that characterize the U.S. educational systems. One of the most powerful is DOE’s Civil Rights mandates, which charge it with enforcing civil rights law across multiple dimensions of the educational system, including through data collection. Box 4-1 discusses key aspects of the department’s civil rights functions addressing discrimination on the basis of race and ethnicity and disability status.

Addressing racial and ethnic education inequities will have economic effects as well (and that also shapes health status). A McKinsey report noted that achievement gaps between demographic groups present “unrealized economic gains” and “underutilized human potential” (Auguste et al., 2009). For example, the gap between White students and Black and Hispanic students deprived the U.S. economy of $310 billion to $525 billion a year in productivity, equivalent to 2 to 4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) (Auguste et al., 2009).

This chapter examines levers for federal engagement in early childhood, K–12, and higher education. Many policies and issues could be reviewed, but four areas particularly warrant attention and improvement (see Chapter 1 for an overview of the committee’s process for selecting the policies reviewed in this report). The first is the quantity of schooling. Starting with access to high-quality early education, so that children from all backgrounds start kindergarten on track and ready to learn, and continuing through high school graduation and equitable opportunities for higher education, the number of years in school is an important determinant of a range of outcomes. The second is the quality of those years of schooling—that is, making sure that time spent in school is used productively so that

society’s investments in education pay off for individuals and communities. Third, schools often provide services that directly influence health, from medical services at health clinics to prepared meals. The best evidence needs to be used to ensure those services are delivered in a health-promoting, equitable manner. Fourth, schools are based in communities, with noteworthy efforts across the nation to create environments that link students and families with community services and social supports.

This chapter is, for the most part, unable to report data on the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) population specifically due to data aggregation with the Asian population or lack of data. This renders the population invisible in this discussion and masks differences between NHPI and Asian people (see Chapter 2 for more details). The chapter begins with a discussion of the link between education and health, including an overview of racial, ethnic, and tribal inequities, followed by examples of federal policies that impact health equity organized by early care and education, K–12 education, higher education, and direct health provision via the education system.

Education and Health Inequity

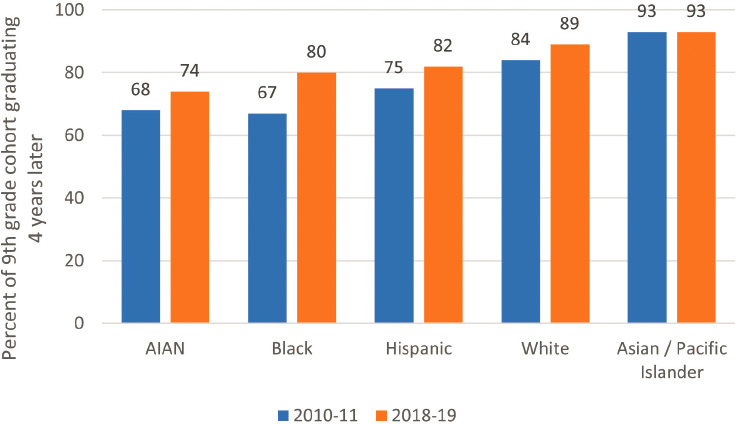

Much of the association between education, health, and economic outcomes is mediated through the total years of education completed; most racial and ethnic groups have seen steady progress. Figure 4-1 shows high school graduation rates, as measured by the DOE adjusted cohort graduation rate, which is the percentage of first-time ninth-graders in public high schools who graduate with a regular diploma within 4 years,

NOTES: AIAN = American Indian or Alaska Native. States have the option of reporting data for either a combined “Asian/Pacific Islander” group or the “Asian” and “Pacific Islander” groups separately. This table aggregates the “Asian/Pacific Islander” data and the separate “Asian” and “Pacific Islander” data to compute the “Asian/Pacific Islander” adjusted cohort graduation rate. This represents an inaccurate representation of the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander and Asian populations as distinct racial Office of Management and Budget minimum categories.

SOURCES: Data from NCES, 2021, n.d.

for graduation years 2011 and 2019. Graduation rates have increased overall, from 80 percent in 2011 to 86 percent in 2019, and the differences across racial and ethnic groups have narrowed. For example, Black students’ rates were 80 percent as high as White students’ in 2011 but 90 percent as high in 2019; that ratio for Hispanic students increased from 84 percent to 92 percent, and AIAN students’ rates increased from 81 percent to 83 percent. The differences by race and ethnicity, albeit at historic lows, are large and meaningful.

Educational attainment is an important determinant of outcomes such as earnings levels, the likelihood of living above the poverty line and being food secure, neighborhood quality, and marital status (Creamer et al., 2022; Parker and Stepler, 2017). Furthermore, in some domains, its importance is growing over time (see the following section for more information). Some worry that the increase in graduation rates reflect schools making it easier to graduate in response to accountability pressures (e.g. through lowered grading standards or increased use of “credit-recovery” programs). Recent research finds that relatively little of the increase is due to changed

graduation standards but instead reflects a substantial increase in human capital (Harris, 2020; Harris et al., 2023; NASEM, 2023b).

Educational attainment is also highly correlated with a range of health outcomes (Campbell et al., 2014; Cutler and Lleras-Muney, 2006). Adults with lower attainment are more likely to report worse health status, more chronic disease burden, a higher likelihood of obesity, and higher rates of smoking and substance abuse (Egerter et al., 2009; Ogden et al., 2017). Ultimately, life expectancy is strongly correlated with attainment; those with a college degree or more gained years of life expectancy over the last two decades, but those without a college degree experienced a decline (Case and Deaton, 2021).

The relationship between education and health spans across generations as well. Babies of mothers who did not graduate high school experience increased infant mortality and have lower birthweights than those born to mothers with a college degree or more (Gage et al., 2013; Sosnaud, 2019). Mothers’ education predicts children’s likelihood of being in fair or poor health (Monheit and Grafova, 2018). These health characteristics in turn influence children’s education (Figlio et al., 2014), setting up a cycle that repeats across multiple generations.

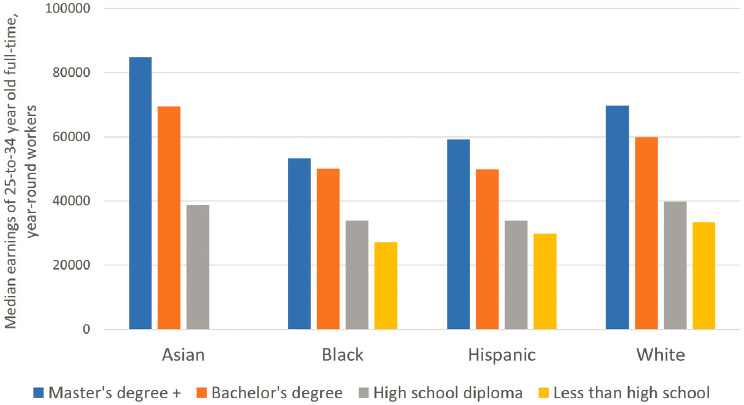

The relationship between education and earnings varies by race and ethnicity. Figure 4-2 shows median earnings among 25–34-year-old adults

NOTE: Data source includes other racial and ethnic groups not separately shown, including Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander and American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN); however, annual earnings by educational attainment for Pacific Islander young adults and AIAN young adults are not available because these data did not meet reporting standards.

SOURCE: NCES, 2022a.

who work full time and year round, with no statistical difference across race and ethnicity among those with less than a high school diploma. Differences between White and Asian people on one hand, and Black and Hispanic people on the other hand, become statistically significant and larger as educational attainment is higher. Within each race and ethnicity category, median earnings among those with more education are higher than for those with less education.

Education policy has no panaceas. Nonetheless, strong evidence shows that some policy changes and investments will improve outcomes and narrow differences in educational attainment and quality across racial and ethnic groups. Although the best mix of changes to policy and practice to improve outcomes will vary by state, district, school, or student group, research can guide policy makers on which choices are likely to have a strong return on investment.

Conclusion 4-1: There remain large differences in educational achievement and attainment between White and Asian students, on one hand, and Black, Latino/a, and American Indian and Alaska Native students, on the other. The empirical evidence that education is associated with health is strong. The causal evidence that more education can improve health is compelling given the many pathways through which education can affect health.

The Intersection of Race, Ethnicity, and Disability Status in Education

Health and health care access in education settings have ramifications for children with disabilities, especially at the intersection with race and ethnicity. Inequitable diagnosis of autism may reflect disparities in access to health care, underscoring the importance of offering early developmental screenings in education settings, and “research shows that among Medicaid-eligible children with autism diagnoses, White children are diagnosed over a year earlier than Black children” (Gordon, 2017).

Individuals with disability have been denied equitable educational opportunities (see Box 4-1). The intersection of disability and race and ethnicity in education also has sparked intense debates about measures and methodology to ascertain whether racially and ethnically minoritized children, particularly Black children, have been over- or underrepresented in special education. IDEA requires states to regularly collect and review district-level data to assess variation across racial and ethnic groups by disability category and educational setting without adjusting for variables that correlate with need for services (Gordon, 2017). The 2002 NRC report Minority Students in Special and Gifted Education “cautioned against using unadjusted aggregate group-level identification rates to guide

public policy” because of the difficulty of interpreting differences and ascertaining their proportionality (NRC, 2002). Identifying students for special education varies widely across school districts and states, but “forcing states to establish uniform standards is dangerously inconsistent with the IDEA mandate of a free and appropriate public education for all. When identifying another student pushes a district over a risk ratio threshold, the district faces a clear incentive to under identify—that is, to withhold services from—children who already face a broad array of systemic disadvantages” (Gordon, 2017).

Data reported by DOE under the IDEA indicate that “Black or African American students with disabilities are more likely to be identified with intellectual disability or emotional disturbance than all students with disabilities and more likely to receive a disciplinary removal than all students with disabilities” and “White students with disabilities are more likely to be served inside a regular class 80% or more of the day than all students with disabilities” (DOE, 2021b). Moreover, “Black students have been overrepresented in special education since the U.S. Office of Civil Rights first started to sample school districts in 1968. Disparities in identification are greatest for more subjective disabilities, such as specific learning disabilities (SLD), intellectual disabilities (ID), and emotional disturbances (ED)” (National Center for Learning Disabilities, 2020).

The National Academies report Closing the Opportunity Gap for Young Children (NASEM, 2023b) provides additional detailed discussion about the intersection of race, ethnicity, and disability and examines the policies and practices that can create opportunity gaps for children from racially and ethnically minoritized groups. It recommends that DOE fully integrate IDEA programming with general early childhood and K–12 education. The recommendation includes specific strategies to address uneven access; quality and dosage of interventions; inclusion; nonbiased and accurate disability identification that specifically considers over- and underidentification of specific groups, such as children of color; and prohibiting punitive and harsh forms of discipline, with special attention to students of color “who are disproportionately subject to those practices” (NASEM, 2023b, p. 8).

EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION

Inequality in education starts early, with sizable differences across race and ethnicity groups in average math and reading scores when children enter kindergarten (Fryer and Levitt, 2004; Reardon and Portilla, 2016). These gaps tend to stay constant or increase as students age (NASEM, 2023b; Reardon and Portilla, 2016). Evidence shows that preschool attendance can help improve kindergarten readiness, increase school achievement, and provide a range of other benefits.

Many lower-income children attend preschool through the Head Start program,3 which has been shown to have substantial long-term impacts, including raising high school graduation rates and college attendance (Bauer and Schanzenbach, 2016; Deming, 2009; Garces et al., 2002). More recently, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that Head Start improves language skills and literacy, especially in children who would not attend preschool without Head Start (Kline and Walters, 2016; Puma et al., 2010). Impacts of early childhood education (ECE) programs vary across settings and program characteristics (Cascio, 2021). Evaluations of some ECE programs demonstrate little or no positive impact on child health outcomes or even negative impacts (Durkin et al., 2022). For example, a recent randomized controlled trial suggests the initial test score gains from Head Start dissipate over time. Other studies, though, have indicated that even when effects on test scores fade, interventions, especially in early childhood, can affect outcomes over the long term, perhaps due to how Head Start influences social, behavioral, and emotional skills (Chetty et al., 2011; Heckman, 2006). As discussed in the National Academies report Vibrant and Healthy Kids (NASEM, 2019d), the mixed findings in the literature may result from lack of program quality, poor fidelity to program models, or limited program duration.

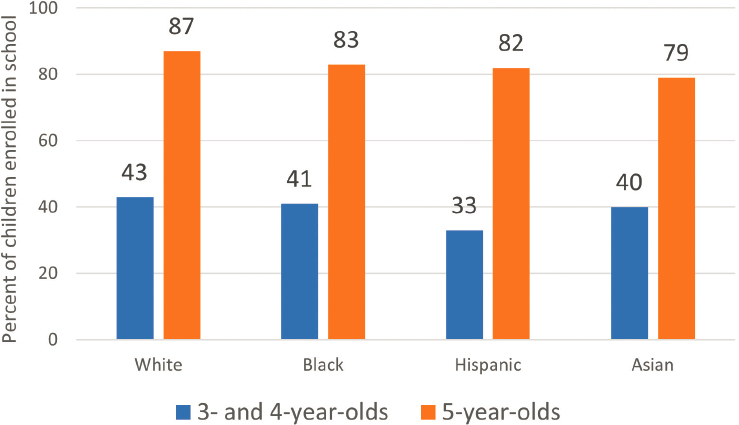

Despite promising evidence of impacts, especially in high-quality preschool programs, many children do not attend school in early childhood (Cabrera et al., 2022). Figure 4-3 shows school enrollment rates by age, race, and ethnicity. A majority of 3- and 4-year-olds do not attend school across all groups; for both age groups, enrollment was lower in 2020 than in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic. Between 2019 and 2020, overall school enrollment dropped from 91 to 84 percent for 5-year-olds and 54 to 40 percent for 3- and 4-year-olds.

Government policies can improve access to high-quality ECE programs with investments in expanding coverage directly, through programs such as Head Start, or by supporting state and local area investments in expanding affordable early childhood care and education. At the same time, it is important to ensure the high quality of ECE through supports including low child–teacher ratios, teacher training and coaching, and evidence-based curricula (Weiland et al., 2022). Closing the Opportunity Gap for Young Children has recommended that the federal government partner with the states to “fully implement a voluntary universal high-quality public early care and education system using a targeted universal approach (i.e., setting universal goals that are pursued using processes and strategies targeted to the needs of different groups). Such programs should

___________________

3 Head Start is a Department of Health and Human Services program that provides comprehensive early childhood education, health, nutrition, and parent involvement services to low-income children and families.

NOTE: Reporting standards were not met for the American Indian or Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander populations—either too few cases were available for a reliable estimate or the coefficient of variation is 50 percent or greater. Data exclude children living in institutions. Race categories exclude persons of Hispanic ethnicity.

SOURCE: Data from NCES, 2022b.

be responsive to community needs, reflect the true cost of quality, and have strong monitoring and accountability systems that specifically address gaps in opportunity” (NASEM, 2023b, p. 6).

One example of how to address racial and ethnic inequities in ECE through federal policy levers include expanding Early Head Start-Child Care Partnerships (HHS, 2020). These were first established in 2014 to increase access to high-quality care for infants and toddlers. The model supports Early Head Start grantees to partner with licensed family and center-based child care providers who agree to meet Early Head Start standards (ACF, n.d.). It increases resources to infant and toddler providers to use the Early Head Start model and so enables a greater number of children and families access to its services, including low ratios and group sizes, credentialed and supported teachers, research-based curriculum and assessment, and comprehensive services (HHS, 2020). Early Head Start is an evidence-based program and among the models approved for the states to support through the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (Hoffman and Ewen, 2011). Furthermore, unlike Head Start, the program permits states to serve as grantees, allowing for states to braid any Early Head Start funding with their block grant funding to take a statewide

approach to serving infants and toddlers with high-quality, evidence-based programming (Matthews and Schmit, 2014; Wallen and Hubbard, 2013). These partnerships could be replicated and expanded by increasing appropriations for the program.

K–12 EDUCATION

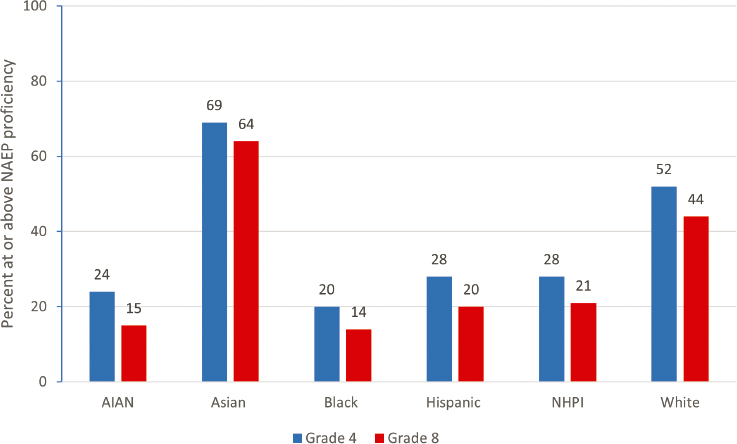

Educational achievement as measured by test scores is linked to a host of outcomes, ranging from educational attainment and earnings to risky behaviors, such as smoking, teen pregnancy, and criminal activity (Heckman et al., 2006). Racial and ethnic groups have substantial differences in achievement that likely contribute to differences in attainment and health outcomes. A nationally representative metric of math and reading skills comes from the Nation’s Report Card (National Assessment of Education Progress) tests, which are given to a sample of students in grades 4 and 8 approximately every other year. One way to examine test score data is the share of students who score above the threshold for “proficiency.” Overall, 41 percent of students scored proficient or above in fourth grade math in 2019, and 34 percent of eighth grade students did (NAEP, 2019).

Achievement inequities—which are important in part because they translate into disparate later-life outcomes—are stark across racial and ethnic groups, as shown in Figure 4-4. Although differences in proficiency rates have been narrowing across groups over time, they remain large, and some groups also show declines in proficiency between grades 4 and 8. Over 60 percent of Asian students are proficient in math in both fourth and eighth grade, and 52 and 44 percent of White 4th and 8th graders, respectively, are proficient. Math proficiency among Hispanic students is 28 percent in grade 4 and 20 percent in grade 8; estimates for Native Hawaiian and “other Pacific Islander” students are nearly identical (NAEP, 2022). In fourth grade, approximately one in four AIAN students is proficient in math, and the rate among Black students is one in five. In eighth grade, 15 percent of AIAN students and 14 percent of Black students score proficient in math (NAEP, 2022).

School Spending

Increases in per-pupil school spending have been shown to improve a range of student outcomes in the short run, including test scores, graduation rates, and earnings. These results have been shown in the “modern school finance” literature (see for example, Jackson et al., 2016; Jackson and Mackevicius, 2021; Lafortune et al., 2018; Rothstein and Schanzenbach, 2022), which is able to separate correlation from causality and demonstrate strong returns to increased spending (Deming, 2022).

NOTE: AIAN = American Indian or Alaska Native; NAEP = National Assessment of Educational Progress; NHPI = Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.

SOURCE: Adapted from NAEP, 2022.

Consistent with this, decreases in spending, such as those due to economic recessions that result in states cutting education budgets, lead to worse test performance and college attendance, especially for Black students and those in low-income neighborhoods (Jackson et al., 2021).

Although the modern school finance literature has not tested the impact of school spending on health outcomes directly, it has shown that school spending improves educational attainment. Because of the established relationship between increased educational attainment and better health, it is reasonable to infer that higher school spending will lead to improved health (Buckles et al., 2016; Lleras-Muney, 2005).

Most school spending comes from states and localities, with less than 10 percent from federal sources (Urban Institute, n.d.). Local governments generally raise funds via property taxes, setting up a system in which areas with low property values, which disproportionately serve low-income children and racial and ethnic minorities, can raise and spend less money on their schools. Data also show that a majority of U.S. public-school students attend high-poverty schools, which experience high teacher attrition, larger class sizes, and lower-quality facilities (Schanzenbach et al., 2016). In 2021, 38 percent of Hispanic students attended high-poverty schools, as did 37 percent of Black, 30 percent of AIAN, and 23 percent of Pacific Islander students (NCES, 2023a).

In recent decades, state school finance reforms have increased the share of school spending from the state relative to local governments, increasing funding overall and reducing the relationship with local property values. But because state funding was often targeted based on district-level characteristics, such as property wealth, and not student-level characteristics, such as race or family income, on average, these reforms failed to close spending gaps between students of different income levels, races, or ethnicities (Lafortune et al., 2018). There are differences in national averages in education spending across race and ethnicity (Rubinton and Isaacson, 2022). Total spending is roughly twice the amount spent on instruction alone, and it includes capital expenditures for property and buildings, as well as salaries and benefits, supplies, and purchased services (NCES, 2023b).

Many differences in funding across racial and ethnic groups are driven by cross-state differences in spending. Some costs, such as salaries, are lower in low-spending states as well, but even adjusting for differences in costs of living, variation in education spending is substantial across states (Schanzenbach et al., 2016). Black students disproportionately live in states (often in the South) that spend less per pupil. As a result, even when the within-state spending is the same for all racial and ethnic groups, overall, Black students will have less spending than White students because of the different composition of states represented (NCES, 2022c, Schanzenbach et al., 2016).

Federal policy can offset differences in cross-state spending and close spending gaps, which will be expected to improve educational outcomes and health. This is an indirect route, and policy levers may give a larger return in terms of reducing health inequities. However, increasing educational spending would also be expected to improve a range of economic and social outcomes that are not directly health related.

One approach to improvement in low-spending states could be to increase funding for Title I, a federal block grant program that earmarks extra funding to school districts serving low-income children. As Black and Hispanic students and students from other racial and ethnic groups that are minoritized are more likely than White students to be low income, providing more resources through this program could also reduce racial and ethnic differences in spending. Title I is underfunded relative to what the federal formula implies, and its allocation is complicated by rules such as small state minimum provisions (that is, setting a minimum funding threshold for less populous—and less racially and ethnically diverse—states, such as Wyoming and Vermont, offsets some of its ability to reduce differences in spending) (NCES, 2016). As a result, Title I sends less money per low-income student to states with a higher share of such students (Gordon, 2016), including states with high concentrations of the racial and ethnic

groups considered in this report. Increasing Title I funding to states with higher shares of low-income students would reduce funding disparities. Another approach could be to provide federal funds outside of the Title I program; it has many inefficiencies, and it may be more effective to use a different mechanism.

Closing the Opportunity Gap for Young Children provides additional detailed discussion of the effects of funding on educational outcomes and highlights specific areas where federal funding is inadequate, such as for individuals with disabilities (NASEM, 2023b). Most notably, it indicates that federal funding is not adequate to close gaps in state and local funding, and the federal government “has never fully funded its share of IDEA, leaving an outsized burden on state and local governments and families” (NASEM, 2023b, p. 142). Although IDEA’s enactment in 1974 “authorized federal funding for up to 40% of average per-pupil spending nationwide” to pay for some of the costs of providing special education services to students with disabilities, funding never reached that target (Kolbe et al., 2022). Congress approved a 20 percent increase in IDEA appropriations in the fiscal year (FY) 2023 budget, but there is concern that even so, the formula for allocating funding systematically advantages some states, such that “states with larger shares of children experiencing poverty, children receiving special education, and non-White and Black children would on average receive smaller IDEA grants per child” (Kolbe et al., 2022).

Other Policies to Improve School Quality

Other ways to improve educational outcomes could be promoted by federal policies. One important factor is high-quality school personnel. Research shows that standardized test scores also improve when teachers can successfully improve a range of other student outcomes, such as teen pregnancy, college attendance, and their eventual earnings (Chetty et al., 2014a,b). Even after accounting for impacts on test scores, teachers who are good at improving behaviors on outcomes such as absence and suspension rates and grades also raise the likelihood of graduating from high school and going on to college (Jackson, 2018). Additional evidence shows that Black students benefit in both the short and long run from Black teachers (Dee, 2004; Gershenson et al., 2022). Improving the proportion of diverse teachers requires diversifying the pipeline, and research indicates that begins with supporting Black and Hispanic youth to succeed in and complete high school and college (Urban Institute, 2017). Quality school leadership is an important factor as well. Research shows that principals, especially those skilled at management, improve student achievement and teacher instructional practices and well-being (Branch et al., 2013; Grissom and Loeb, 2011; Liebowitz and Porter, 2019).

Evidence exists on policies and practices to adopt to improve students’ access to high-quality classroom teaching and school leadership. For example, professional evaluation of mid-career teachers can improve teacher skill, effort, or both, in enduring ways that improve long-run performance (Taylor and Tyler, 2012). Highly skilled teachers also influence their peers’ performance—research shows that a teacher’s ability to increase students’ test scores improves when working in the same schools with high-performing teachers (Jackson and Bruegmann, 2009). Recognizing the importance of teachers, research and experimentation is needed to improve tools to recruit, train, and retain excellent classroom teachers and administrators.

Other promising methods include providing individualized, small-group tutoring to students who are behind grade level in math, which has been shown to improve math achievement and reduce the number of classes failed (Ander et al., 2016; Guryan et al., 2023). Extra instruction during school vacations, from a classroom teacher and in small groups of roughly 10 students, also yields strong achievement gains in the subject (Schueler, 2020; Schueler et al., 2017). Computer-assisted learning programs designed to meet students at their skill level and teach targeted skill development have also been shown to be successful, particularly for mathematics (Escueta et al., 2020).

Federal school accountability policies, such as provisions of NCLB and the ESSA, may improve achievement and narrow racial and ethnic gaps (Dee and Jacob, 2011; NASEM, 2017). For example, ESSA requires that “states establish student performance goals, hold schools accountable for student achievement, and include a broader measure of student performance in their accountability systems beyond test scores” (ASCD, 2016).

School choice may also improve education through several avenues, including allowing parents to find schools that may better meet their children’s needs than their neighborhood public school (Whitehurst, 2017). One approach to increasing choice is to expand charter schools, which are available in most states and enroll nearly 7 percent of public-school students (Snyder et al., 2019). Although average student performance is no different in charter schools compared to public schools, differences in impacts are wide across schools and students, with generally stronger evidence of positive effects among urban and low-income students (for recent reviews see Cohodes and Parham, 2021; Kho et al., 2020). A study of the relationship between racial segregation and school choice (including charter schools) found a positive correlation between them and urged that decision makers implementing school choice policies incentivize schools to implement concrete actions to improve diversity (Whitehurst, 2017).

Conclusion 4-2: There is strong evidence some federal policy changes and investments can improve educational outcomes and narrow differences in educational attainment and quality across racial and ethnic groups. However, the best mix of changes to policy and practice to improve student outcomes will vary across states, districts, schools, or groups of students. Thus, evidence-based policy, accountability, and community engagement play a critical role in improving federal policy for education as it relates to equity.

Conclusion 4-3: Increases in per-pupil school spending have been shown to improve a range of student outcomes in the short and long run, including test scores, educational attainment, and earnings—all of which in turn are correlated with better health outcomes. Decreases in school spending lead to worse student outcomes, especially for children living in low-income neighborhoods and Black students. Federal policy could play a role to offset differences in cross-state spending and close spending gaps across racial and ethnic groups.

The Role of Communities

Communities are both the places and the organizations and social networks that help to shape the conditions for health and well-being, including education. Chapter 7 of this report discusses important dimensions of the community role in health equity and federal approaches that value the voice and priorities of and help to build the power of communities, and Recommendation 4 (Chapter 8) calls on the federal government to prioritize community input and expertise when changing or developing federal policies to advance health equity—including by assessing the placement, composition, and role of community advisory boards. This recommendation has clear applications to the community role in shaping public education, and the discussion that follows explores the existing context for community–school collaboration.

Schools can partner with communities and community organizations in ways that are mutually beneficial and can further both educational and social outcomes (see, for example, Gross et al., 2015). Community schools are public schools that provide services and support that fit a specific school’s/neighborhood’s need—educators, local community members, families, and students work together to strengthen conditions for student learning and healthy development. The concept of a community school and its variants across the country can be traced back to John Dewey’s description of schools as “social centers” that could be responsive to students’ needs in a comprehensive way (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2021;

Kimner et al., 2022). In recent years, the work of community schools has been shown to not only improve student outcomes but also further educational equity (Maier et al., 2017; Quinn and Blank, n.d.).

The movement to strengthen ties between education and community building reflects a belief in benefits that accrue to not only individual students and families (i.e., wraparound supports to keep students in school and help them succeed) but also the community by providing an important hub for civic life.

Education also has an important role in civic and social engagement (Campbell, 2006)—throughout their education, individuals develop their identities, along with their associates, which influences their future via social connectedness and critical thinking (NASEM, 2019c). Education in the aspect of social and self-identity is beneficial for student health, as it plays a role in the student discovering their own confidence, self-motivation, independence, and decision making, which are all needed to shape their life and create career goals (NASEM, 2019c).

Different models or approaches for community schools exist, all of which recognize that schools are a core component of civic infrastructure in communities—they train the next generation of citizens, and many serve as community centers and voting locations—and that school success is dependent on access to a range of community and social supports, especially in communities affected by past and continuing social and economic inequities. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the evidence on the important school and community bond and especially its effectiveness in closing education equity gaps (Task Force on Next Generation Community Schools, 2021). The Communities in Schools model implemented nationwide and the Coalition for Community Schools have yielded improvement on certain measures, ranging from attendance rates to passing standardized state tests (Maier et al., 2017; MDRC, 2017). A related framework, the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Model developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with the Association for Supervision and Curriculum, is student centered and comprises 10 components that the community can use to support the school (CDC, 2022). These range from physical activity to social and emotional climate and include community involvement.

In 2020, the Brookings Institution, Child Trends, and community school leaders launched a task force on Next Generation Community Schools (Harper et al., 2020), which outlined seven ways community schools can close inequities and transform education and provided an overview of the impact of community schools on educational outcomes (Task Force on Next Generation Community Schools, 2021). A follow-up to the Task Force on Next Generation Schools, the Community Schools Forward Project launched in 2021–22; in early 2023, it co-convened a second community

schools task force focused on implementation guidance to education systems and their partners (Kimner et al., 2022). The Biden Administration announced in 2023 that it provided $63 million in grants to 42 grantees under its Full-Service Community Schools program (OESE, 2023).

HIGHER EDUCATION

Background

Brown v. Board of Education shaped school integration and provided a foundation for education equity in K–12 education; along with several statutes (e.g., Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, and Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990), it has also served as a foundation for affirmative action in higher education (Cornell Law School, n.d.). Affirmative action refers to procedures intended to “eliminate unlawful discrimination among applicants, remedy the results of such prior discrimination, and prevent such discrimination in the future” (Cornell Law School, n.d.). The 2003 Supreme Court decision Grutter v. Bollinger4 upheld the status quo, asserting that consideration of race was just one dimension of a holistic approach to weighing all aspects of an applicant’s background (Reichmann, 2022). Affirmative action in higher education has bearing on both the ability of racially and ethnically minoritized students to be accepted to competitive schools and programs (and thus on their future trajectories) and the diversity of those institutions and the effect that has on talent and innovation across various fields of study (NASEM, 2023a).

A 2023 National Academies report concluded that so called race-neutral or color-blind admissions criteria, which are advocated by the plaintiffs in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard College5 and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina6—two cases that were heard by the Supreme Court in 2023—overlook inequities that “may produce racially disparate outcomes. These differential outcomes reflect—and can reinforce—the broader race-related history of access and barriers, wealth accumulation, and discrimination in the United States. A neutral policy or standard cannot erase this history and ignoring the impacts of race can perpetuate cumulative and inequitable outcomes” (NASEM, 2023a, p. 220).

___________________

4 Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003).

5 Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard College, 600 U.S. ___ (2023).

6 Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina, 600 U.S. ___ (2023).

The Linkages Between Health and Higher Education

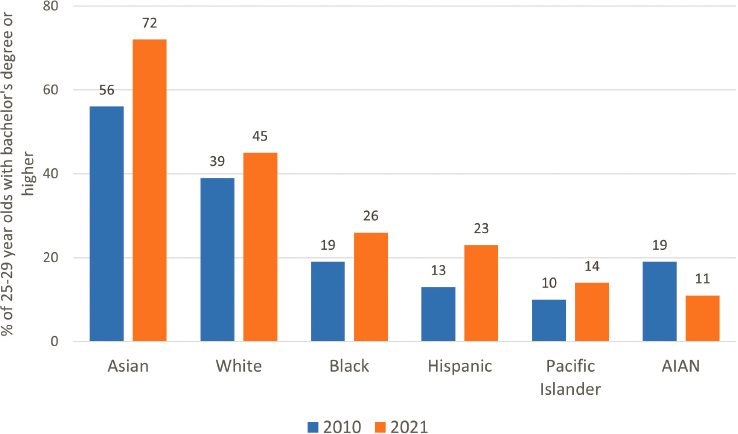

As noted, research shows that quantity of education is important to health outcomes, with college graduates expected to live at least five years longer than individuals who have not completed high school (Egerter et al., 2009). College enrollment and completion rates generally have also risen in recent years, with increasing convergence across racial and ethnic groups. Between 2010 and 2021, the share of young adults ages 25–29 with a bachelor’s degree or higher rose from 32 percent to 39 percent; rates rose among White people by 15 percent, Asian people by 29 percent, Black people by 37 percent, Pacific Islander people by 40 percent, and Hispanic people by 77 percent (see Figure 4-5) (NCES, 2020). Estimated rates among AIAN people fell from 19 to 11 percent, in contrast with their increase in high school graduation rates over nearly the same period.

Improving Outcomes in Higher Education

Even though the cost of tuition and fees for a college education has increased in inflation-adjusted terms, the benefits in increased earnings still outweigh the up-front investment cost on average (Barrow and Malamud, 2015). Like other investments, college comes with some risk of not paying off, such as if students pay tuition but do not complete their degree

NOTE: AIAN = American Indian or Alaska Native.

SOURCE: Data from Digest of Education Statistics, Table 104.20 in NCES, 2020.

(Athreya and Eberly, 2021). Policies that reduce financial barriers to higher education can improve the enrollment and graduation rates, especially among low-income students. Notably, the federal–state balance of funding for higher education has shifted since the 2008 recession, with state funding declining and federal funding increasing, especially through Pell Grants and Veterans’ Education Benefits (Pew Research Center, 2019).

Information about financial assistance and help navigating the complex system may improve student outcomes. For example, a recent large-scale experiment tested the impact of providing simplified information about high-achieving, low-income students’ eligibility for free tuition at an elite public university. Providing clear information but not actually changing the amount of aid offered substantially increased both application and enrollment (Dynarski et al., 2021). Another randomized experiment provided student aid application assistance to low-income individuals while they were receiving help with tax preparation. Students whose families received this assistance were 28 percent more likely to complete 2 years of college during the subsequent 3 years (Bettinger et al., 2012).

Support to address potential barriers to student success has also been shown to improve graduation rates. The City University of New York’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs program offered a range of supports to students: financial supports, including a tuition waiver that covered any gap between financial aid and college costs, and free access to textbooks and public transportation. Students were required to attend college full time and had access to blocked courses and consolidated schedules along with support services, such as academic planning, accessing campus services, balancing school with other responsibilities, and staying on track to graduate. The program substantially increased graduation rates (Weiss et al., 2019). It was replicated in Ohio, with similar effects (Miller and Weiss, 2022). A similar intensive case-management program in Texas also substantially increased degree completion among low-income women attending community colleges (Evans et al., 2020).

Pell Grants

The Federal Pell Grant7 Program marked its 50th anniversary in 2022, and it has played a crucial role in helping approximately 80 million students from low-income families, many from Black and Hispanic communities (Biden, 2022) attend college. In the 2022–2023 academic year, the Congressional Budget Office projects that 5.9 million people will receive

___________________

7 The Pell Grant is awarded to eligible undergraduate students who have not earned a bachelor’s or professional degree. In some cases, individuals may receive a grant if enrolled in a postbaccalaureate teacher certificate program.

Pell Grants, with a maximum award of $6,895 and an average of $4,640; total federal spending is $27.4 billion in 2022–2023 (Koestner, 2022). With more than $28 billion aid in the 2017–2018 award year, Pell Grants are the second-largest source of need-based aid for postsecondary education, after federal student loans (College Board, 2022). Eligibility for additional need-based grant aid increases students’ attendance, bachelor’s degree completion, and earnings (Castleman and Long, 2016; Denning et al., 2019). But the Pell Grant has not kept up with inflation and covers a shrinking portion of tuition (Protopsaltis and Parrott, 2017). Some researchers argue that increasing it will increase college affordability in an efficient, targeted manner (Levine, 2021). Estimates suggest that doubling the Pell Grant would substantially reduce education debt for recipients receiving the maximum award, by approximately 85, 83, and 80 percent for AIAN, Latino/a, and Black students, respectively (GEPI, 2021).

Pell Grants for incarcerated people

Postsecondary education in prison has been shown to contribute to successful re-entry. Participants are more likely to be employed after release and have decreased recidivism (Bozick et al., 2018; Davis et al., 2013). In 1994, Congress disqualified incarcerated people from Pell Grant eligibility (before that time, eligibility had few legislative restrictions) (Oakford et al., 2019).

In 2015, DOE announced the Second Chance Pell experiment under the Experimental Sites Initiative, which allows incarcerated students who would be eligible for Pell Grants if they were not incarcerated to access them (DOE, n.d.-c). It allows a limited number of college programs to accept Pell Grants for incarcerated students. These programs enrolled 28,000 students between 2016 and 2021, 32 percent of whom obtained either a certificate or an associate’s or bachelor’s degree (Chesnut et al., 2022). However, several barriers that kept incarcerated people from being able to take advantage of the program were documented, including meeting Pell Grant eligibility standards and applying for the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) (GAO, 2019).

In December 2020, Congress restored the law to give incarcerated people the opportunity to obtain a college education by making changes to the Higher Education Act of 1965 and FAFSA (FSA, 2022). This change allows any public or private nonprofit college to start a prison education program, following a set of guidelines and an approval process, and will provide Pell Grants to those in prison starting in July 2023. No eligibility restrictions related to conviction type or sentence length were included, and Congress eliminated FAFSA questions about selective service registration and drug convictions—common barriers to Pell Grant access. According to one estimate, as many as 463,000 Pell Grant–eligible incarcerated people stand to benefit (Oakford et al., 2019). To ensure high-quality programs, Congress

designed the approval process to control for program quality with up-front vetting and ongoing evaluation (Custer, 2022). Lifting the Pell Grant restriction for incarcerated people will further the goal of health equity.

Conclusion 4-4: In 1994, the federal government disqualified incarcerated people from Pell Grant eligibility, and in 2020, lawmakers reinstated Pell Grant access for incarcerated people enrolled in qualifying prison education programs. This is a promising example of how removing erected barriers to access for specific populations, such as incarcerated people, can address unequal access to federal programs that are linked to social determinants of health and health inequities.

Financial aid can help incarcerated students gain access to postsecondary education; however, both colleges and students need to understand the complexities of administering Pell Grants in the corrections environment.

Student Loans and Repayment

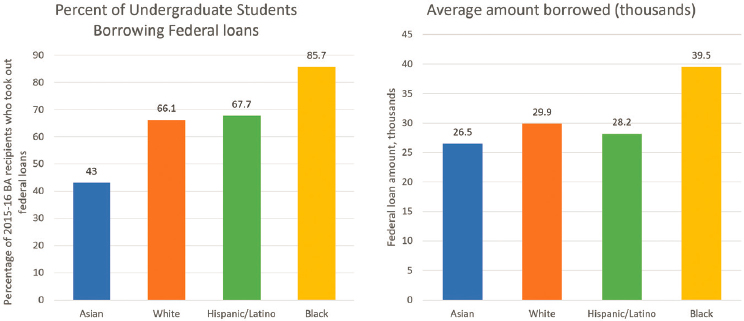

Student loans have received considerable attention, and high repayment burdens cause financial struggles for some borrowers. Figure 4-6 shows characteristics of federal student loans for the cohort of students receiving a bachelor’s degree in 2015 to 2016. As shown in the panel on the left, 86 percent of Black recipients borrowed federal loans, compared with

NOTE: “Black” refers to not Hispanic or Latino and also includes African American; “Other or Two or more races, not Hispanic or Latino” (not reported in the graph) includes American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (NHPI), and respondents who identify as more than one race. This masks inequities for AIAN and NHPI people.

SOURCE: Data from Thomsen et al., 2020.

70 percent of Hispanic or Latino, 68 percent of White, and 44 percent of Asian recipients. On average, Black students borrowed a higher amount than other groups, at nearly $40,000, compared with $26,000–30,000 for other racial and ethnic groups, as shown in the right panel.

Certain federal policies can reduce the burden of student debt, especially for those in low-earning jobs. For example, programs such as income-driven repayment plans tie repayment amounts to incomes. Similarly, programs forgive outstanding balances under certain conditions. However, the program that forgives student loans after 10 years of employment in the nonprofit sector (and after making 120 qualifying monthly payments) has administrative burdens (Link et.al, 2022). This is an active area of policy discussion, and reasonable people can disagree about the best manner to structure these policies (Chingos, 2023; DOE, 2023b; Knott, 2023; Looney, 2022; Oakford et al., 2019). It is clear that targeted student debt relief will disproportionately impact Black and Latino borrowers and potentially also borrowers from other groups discussed in this report.

Minority Serving Institutions

Minority serving institutions (MSIs) were established in response racism and the exclusion of racially and ethnically minoritized people from institutions of higher education. The first MSIs were the 108 Historically Black colleges and universities founded before the 1964 Civil Rights Act (DOI, n.d.). The first tribal college and university (TCU) was Diné College, founded in 1968 on tribal land and under the control of Navajo Nation (Diné College, n.d.). Federally run schools and colleges also exist for AIAN people. These fall under the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) (Bureau of Indian Education, n.d.). The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 19758 gave authority to federally recognized tribes to contract with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to operate Bureau-funded schools. BIE operates 58 of the 183 tribal schools that it funds. BIE also directly operates two postsecondary institutions: the Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kansas, and the Southwest Indian Polytechnic Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico (Bureau of Indian Education, n.d.). MSIs also include Hispanic serving institutions (HSIs) and Asian American, Native American, and Pacific Islander serving institutions. MSIs in the states and territories are heterogeneous in their histories, formation, resources, geographies, and challenges but do participate in MSI programs.

Institutions of higher learning that have an explicit mission to educate Black, Hispanic, tribal or sovereign nations, or other minoritized students provide many of the elements needed to support educational success, including cultural competence and relevance, a profound recognition of the

___________________

8 Pub. L. 93–638, 25 U.S.C. 450 (1975).

legacies, contemporary currents, and catastrophic harms of racism, exclusion, and othering (NASEM, 2019a). But due to those legacies and their ramifications, these institutions are generally underresourced compared to those that do not have that mission and serve predominantly White students (CMSI, n.d.; Flores and Park, 2013).

The high level of diversity at most MSIs creates considerable heterogeneity within specific institutions; for example, a historically Black college or university may also be an HSI (NASEM, 2019a). These designations make these institutions eligible for certain federal programs and research grants. The categorical funding opportunities were meant to level the playing field and target resources to these institutions; however, this has not been fully realized (NASEM, 2019a).

Research on the state of and gaps in MSI funding reveals several structural and systemic inequities. MSIs receive less support in grants and contracts from federal and state governments, have much smaller endowments, and must rely more on tuition—but are more likely to serve students with higher financial need (see, for example, Toldson, 2016; Williams and Davis, 2019). At the state level, outcomes-based funding can affect education inequities, because these institutions “serve larger percentages of students who are traditionally underserved in [the] K–12 system, they require more resources and supports to best serve these students” (Li et al., 2017).

A 2019 National Academies study of the role of MSIs in strengthening STEM education reviewed data on the educational outcomes to evaluate student success and found that some measures are flawed because they fail to appropriately incorporate context (NASEM, 2019a). For example, measures of graduation rates do not consider complex student pathways (e.g., moving to another MSI, part-time study) or a richer set of characteristics, such as disability status, or first-generation college attendance. Gasman and colleagues (2017) found that benefits of education, such as leadership and critical thinking skills, are not included in data collection on MSI educational outcomes and noted that TCUs prioritize some hard-to-quantify outcomes, such as “community engagement, language revitalization, leadership, and cultural appreciation” (p. 3).

Economic outcomes of MSI-educated students are promising, according to research from Espinosa and colleagues (2018), who found that “MSIs propel their students from the bottom to the top of the income distribution at higher rates than do non-MSIs” and that the data make a strong case for “increased investment in institutions that are meeting students where they are, and making good on the value of higher education for individuals, families, and communities” (p. iii and iv).

Despite the recognition that measuring the outcomes and demonstrating the value of the MSI education requires better and more expansive types of data, state funding approaches continue to be premised on narrow and inadequate metrics. The federal government can be important in strengthening

the flow of research and other funding to MSIs, and a long list of federal agencies provide opportunities targeting MSIs (see, for example, Lewis-Burke Associates LLC, 2021).

Conclusion 4-5: Minority serving institutions have demonstrated value on investment in economic outcomes for their students, and their effects on the racially and ethnically minoritized communities they serve merit research and measurement.

SCHOOL OPPORTUNITIES TO DIRECTLY PROMOTE HEALTH, INSURANCE COVERAGE, AND ACCESS TO CARE

Schools have unique opportunities to advance health. For example, they can assist in outreach and enrollment of eligible children in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). In turn, through school-based services and school-based health centers (SBHCs), they can provide Medicaid-covered services, including through Individualized Education Programs under IDEA,9 and behavioral health services to eligible children. They can also help children enrolled in Medicaid access needed services (CMCS Informational Bulletin, 2022), including children who are not served by IDEA. In 2014, CMS allowed schools to use Medicaid for school-based free health care services, but uptake of this policy has been slow for a variety of reasons, including schools’ administrative burdens and costs (CMS, 2014; Healthy Students, n.d.; Wilkinson et al., 2020).

Ensuring that eligible students are enrolled in Medicaid can have positive budgetary implications for schools, because Medicaid may cover services and evaluation required for an individualized education plan (MACPAC, 2018). In addition, Medicaid and CHIP can directly improve children’s health, enabling them to do better in school, miss fewer days due to illness or injury, finish high school, graduate from college, and earn more as adults (Cohodes et al., 2016; Levine and Schanzenbach, 2009). Oregon has innovated in connecting health care reform with educational outcomes through its Healthy Kids Learn Better Partnership, which brought together schools and the state’s coordinated care organizations to collaborate on public health interventions at the local and state levels. A health system leader from Oregon described Medicaid as “the scaffolding that helps families receive the services they need to get out of poverty,” helping to “improve kindergarten readiness and help the next generation to avoid

___________________

9 This law makes a free appropriate public education available to eligible children with disabilities throughout the nation and ensures special education and related services. It governs how states and public agencies provide early intervention, special education, and related services to more than 7.5 million (as of school year 2020–21) eligible infants, toddlers, children, and youth (DOE, n.d.-a).

poverty and become high users of Medicaid services” (NASEM, 2020). In a recent communication, CMS reminds states that the federal government can match state and local expenditures for administrative activities, including outreach and enrollment (CMCS Informational Bulletin, 2022). It specifically mentions “that local education agencies can use school registration processes and other regular contacts they have with families to help children (and their family members) enroll in Medicaid or CHIP. Obtaining Medicaid reimbursement for outreach and enrollment allows schools to expand health care services and programs” (Orris and Wagner, 2022). School partnerships may be particularly helpful as the COVID-era prohibition against terminating Medicaid coverage is sunset, and many children are expected to experience “churn”—loss of coverage and quick reenrollment. Such coverage disruptions often reflect administrative burdens, which disproportionately impact racially and ethnically minoritized people, and can be both economically costly and harmful, such as resulting in interrupted treatment or medication access (Wikle et al., 2022).

School-Based Health Centers

SBHCs play a unique, direct role in health promotion. An estimated 20.3 million children suffer from insufficient access to health care, with 3.3 million uninsured, 10.3 million without primary care, and 6.7 million with unmet specialty care needs (Children’s Health Fund, 2016). Increasingly, students can directly receive medical care at school through SBHCs, which have doubled over the past 20 years, with nearly 2,600 in the 2016–2017 school year (Love et al., 2019). SBHCs use a variety of models, including a single clinician providing primary care, a team of staff providing primary care and mental health care, and a larger staff of clinical and other staff (e.g., social worker, health educator, dental providers) (Kjolhede et al., 2021). Their range of services vary, including treatment from a school nurse, immunizations, behavioral health care, and asthma treatment (MACPAC, 2018). Almost half of the centers employ an expanded care team, often including providers of dental and eye care, helping resolve common problems that interfere with student learning (Conley and Schanzenbach, 2020).

SBHCs are funded by a range of public and private sources, from local and state funding to federal block grants (e.g., Maternal and Child Health Block Grant) and project grants and school districts billing the federal Medicaid program (APHA, 2017; PATH, 2020). Both CDC’s Community Guide and the Community Preventive Services Task Force recommended SBHCs as an effective approach to furthering health equity because of their impact on health, educational, and other student outcomes (Kjolhede et al., 2021).

A recent study found that SBHCs reduce teen pregnancy rates (Lovenheim et al., 2016). Other studies have found that SBHCs reduced students’ depressive episodes and suicide risks and improved academic measures, such as GPAs, attendance rates, and suspensions (Conley and Schanzenbach, 2020; Knopf et al., 2016; Paschall and Bersamin, 2018). Only 6.3 million students have access to an SBHC—about 13 percent of total students (Love et al., 2019). Expanding the number of centers will help more kids get the care they need, promoting both academic and health equity in the process.

School Meals Programs

The National School Lunch Program (NSLP), established in 1946, is a federally assisted program administered by the Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food and Nutrition Service (USDA, n.d.). NSLP is usually administered through state agencies that operate through agreements with school authorities. Participating schools receive cash reimbursement for each lunch or snack served and USDA commodity food donations for lunches.

Although the program was originally created out of concern that malnourishment affected national security and welfare, school meals (including lunch, breakfast, and snacks) now help combat child hunger and can encourage healthy eating (Ralston et al., 2008). NSLP provides nutritionally balanced meals at low or no cost to students attending public schools, nonprofit private schools, and residential child care institutions. Under the traditional rules, students with a household income at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty guidelines receive free meals, and those with household incomes above 130 percent and at or below 185 percent receive meals at reduced price (USDA, 2019b). Many schools and districts offer free meals to all students through the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), which reimburses schools using a formula based on the share of students who are categorically eligible for free meals due to participation in other programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (USDA, 2019a). In 2019–20, nearly 15 million children attended schools that have CEP (FRAC, 2020). Overall, in 2022 approximately 30 million children participate in the NSLP and 15 million in the School Breakfast Program (SBP) (USDA, 2023).

Similar to schools’ incentives to help families enroll in Medicaid, they have incentives to help eligible families learn about SNAP, because students who are in a household receiving SNAP are directly certified for free school meals. Medicaid coverage also conveys direct certification for free school meals in most states (Bauer et al., 2023).

Alleviating hunger and providing improved nutrition to schoolchildren likely has a range of positive spillover effects. Behavioral, emotional, and mental health and academic problems are more prevalent among children and adolescents struggling with hunger (FRAC, n.d.), who have lower

math scores (Jyoti et al., 2005). Cotti et al. (2018) find that students’ test score performance is worse when the test is given a longer time after their families’ monthly SNAP payments are made, when food consumption tends to be lower. Hoynes et al. (2016) found that children with more years of access to SNAP benefits in the 1960s and 1970s were substantially more likely to graduate high school.

Low-income students in both SBP and NSLP tend to consume a significantly better diet compared to low-income nonparticipants. Studies also show that rates of food insecurity among children are higher in the summer when these programs are not available (FRAC, n.d.).

Evidence suggests that free access to NSLP among schools and districts with high poverty rates improves academic achievement and related outcomes. Schwartz and Rothbart (2020) found that providing free meals to all students in New York City middle schools substantially increased participation in school lunch and improved math and reading performance for both low- and higher-income students. Similarly, Ruffini (2022) found sizable increases in meal participation and some evidence of improved performance in mathematics, and Gordon and Ruffini (2021) found reduced rates of suspension in elementary schools when schools offer CEP.

There are several routes to increasing students’ access to universal free meals. Raising CEP reimbursement rates would likely increase participation among schools with high shares of low-income children. Some support offering free meals to all students, regardless of the level of poverty in the school or district. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government made lunch free to all 50 million public-school students nationwide (Hayes and FitzSimons, 2022). Since then, California, Colorado, and Maine passed bills ensuring all students had free school meals; 21 other states are considering similar policies (Hunter College, 2023).

Summer Feeding Programs

Before 2020, federal policy addressed the summer food gap by offering prepared meals through the Seamless Summer Option and the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP). However, many children lacked access to SFSP sites. For example, Bauer and Parsons (2020) find that in 2018, only 43 percent of children lived in a census tract with a meal site; only about one child for every seven who participated in school lunch programs in the 2017–2019 school year participated in the summer lunch program (FRAC, 2019).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress authorized pandemic electronic benefits transfer (EBT) payments, similar to SNAP benefits, to families of children who lost their access to free or reduced-price school meals. Providing vouchers for grocery purchases instead of prepared meals increased

participation rates and substantially reduced food hardship among low-income populations (Bauer et al., 2020, 2021). This program had its roots in a series of randomized controlled trials for summer EBT payments that had been conducted in conjunction with USDA and shown to substantially reduce food insecurity and very low food security among children (Collins et al., 2014). In December 2022, Congress permanently authorized summer EBT at a level of $40 per child per month (Neuberger, 2022; USDA, 2022). Evidence suggests this will reduce food hardship and improve children’s summer outcomes. Success of this important new program will require states to invest in capacity, expertise, relationships, and data systems to increase the reach of the program and reduce excessive administrative costs and burdens to families.

Conclusion 4-6: Schools have unique opportunities to advance health, ranging from assisting in outreach and enrollment of eligible children in public health insurance programs and income support programs, to offering direct care through school-based health centers, to reducing food insecurity and improving dietary quality through school meals programs. Evidence shows that when schools adopt or improve these opportunities, both health and educational outcomes can be improved.

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

This report examines the broad effect of federal policies on health equity, and rather than proposing recommendations for changes to specific federal programs reviewed in each chapter, the committee mainly offers crosscutting recommendations (see Chapter 8). However, many National Academies reports list evidence-based and promising recommendations for federal action specific to education access and quality to advance health equity and the factors that affect it (including and beyond the federal policies reviewed in this chapter). Most of those recommendations have not been implemented, and are still relevant today (see Box 4-2 for examples).

The key themes of accountability, community voice, data equity, coordination, and eligibility figure in important ways in federal education policy effects on health equity. For example, and as noted, federal education policy can call on states and local school districts to assess and report on measures of educational achievement by racial and ethnic group, English language proficiency, and disability status. The 2001 reauthorization of the ESEA, NCLB, required that states provide disaggregated data to show education performance by race and ethnicity along with other important dimensions. Community voice arises in the context of school-community