Biomarkers for Traumatic Brain Injury: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 4 Incorporating Biomarkers into Research and Clinical Practice

There are promising opportunities to incorporate validated biomarkers into traumatic brain injury (TBI) research and care, drawing on initiatives and partnerships among the private sector, academia, professional communities, and government agencies, said Stuart Hoffman, Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). This chapter opens with speaker presentations discussing how biomarkers can be used in preclinical studies to advance the development and testing of drug therapies for TBI and envisioning a future in which decision-making by care providers is informed in real time by having access to expanded biomarker information. Speakers and participants then shared suggestions for further advancing the use of biomarkers in TBI care, including their incorporation into an updated and refined TBI classification scheme.

USE OF PHARMACODYNAMIC RESPONSE BIOMARKERS IN PRECLINICAL TBI RESEARCH1

Using biomarkers as part of drug screening has the potential to save time and money in translating research to clinical therapies for TBI. Patrick Kochanek, University of Pittsburgh, discussed efforts conducted through the preclinical consortium Operation Brain Trauma Therapy (OBTT) to identify blood-based biomarkers able to function as pharmacodynamic response biomarkers for evaluating drug candidates in several small animal injury models.

He began by sharing an example of an early study by his group that measured biomarker levels and compared results at different time points and across several types of pediatric brain injuries seen in neurocritical care (in this case, head trauma after child abuse, accidental TBI, and hypoxic injury such as from drowning; Berger et al., 2006). The results raised the question of whether blood-based biomarkers could be used to examine the effect of therapies aimed at treating TBI. Kochanek described the establishment of OBTT, a rigorous preclinical, multicenter, drug testing consortium funded by the Department of Defense (DoD), that assessed the performance of 12 therapies in small animal TBI models. Consortium aims included identifying whether a given drug was effective in models representing multiple mechanisms of injury, whether different drug therapies would

___________________

1 This section is based on a presentation by Patrick Kochanek, University of Pittsburgh.

be needed for different TBI phenotypes (represented by different models of injury), and how well blood-based proteins would perform as biomarkers to assess drug performance.

OBTT measured serum biomarkers, including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), among others, and compared levels at 4 hours and 24 hours to evaluate whether a drug was working. Biomarker levels measured after administration of the two most promising drug candidates identified through this screening (levetiracetam and glibenclamide) were compared with conventional outcome measures (Mondello et al., 2011, 2016). The consortium found that GFAP, but not UCH-L1, is a potentially useful pharmacodynamic response biomarker in rat models of TBI. Serum GFAP level significantly increased at 4 hours and/or 24 hours after injury across all the tested TBI models, while the increase in UCH-L1 level in rats, unlike in humans, was too fast and transient to be of use in evaluating drug performance. Comparing levels of GFAP after different injury models (representing, for example, diffuse injury versus penetrating injury) revealed some illuminating differences. Kochanek posited that blood-based biomarkers will be useful in helping understand different laboratory and clinical TBI endophenotypes. Measured GFAP levels also performed consistently across test parameters and sites, showing that biomarkers are useful in comparing TBI models and monitoring model stability.

GFAP levels measured at 24 hours correlated with outcomes at 21 days after injury, based on histologic measures of lesion volume and hemispheric tissue loss. Serum GFAP at 24 hours was able to predict which of the tested drugs would show a benefit in improved motor outcomes over the initial 5 days and histology measured at 21 days, and which drugs in which injury models would fail to improve 21-day outcomes, demonstrating GFAP’s utility as a response biomarker. Generally, Kochanek commented, biomarker data in OBTT was better at predicting histology and motor function than cognitive or behavioral outcomes. While studies in the screening consortium were not powered optimally, these findings are very promising for future larger-scale testing, said Kochanek.

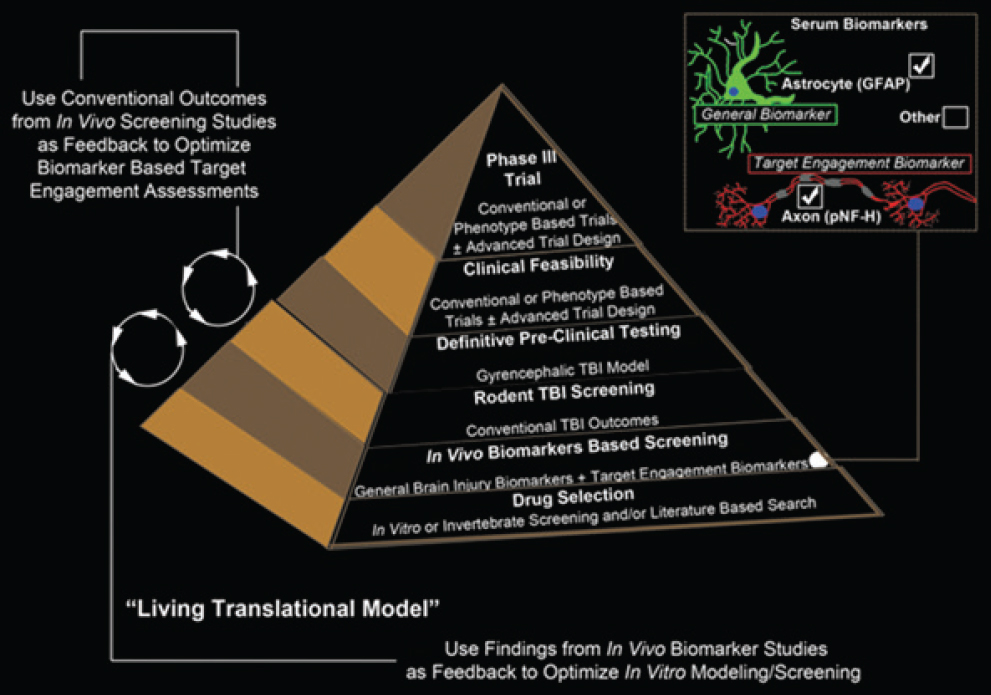

In conclusion, Kochanek shared the design of a “living translational model” for TBI drug screening and selection (Kochanek et al., 2020; see Figure 4-1). In this approach, initial identification of drug candidates (bottom of the pyramid) is followed by screening in small animal models, using serum pharmacodynamic response biomarkers to save money and time. Drugs that are successful in early testing would be further evaluated through more definitive preclinical testing and, ultimately, in clinical trials. Kochanek also advocated for the value of preclinical consortia to undertake rigorous biomarker evaluation and drug testing, in addition to discovery efforts within individual labs. There is a need for further assessment, he

NOTE: GFAP = glial fibrillary acidic protein; pNF-H = phosphorylated neurofilament heavy; TBI = traumatic brain injury.

SOURCES: Presented by Patrick Kochanek, September 29, 2022; Kochanek et al., 2020.

concluded, testing more biomarkers in this kind of environment to determine their temporal profiles across injury models and after various treatments and to optimize biomarker screening for both acute and chronic therapies.

IMPROVING DIAGNOSIS AND ENVISIONING THE FUTURE OF TBI CARE2

Turning to the role of biomarkers in the future of TBI care, David Okonkwo, University of Pittsburgh, recalled the progress that has been achieved in TBI management over the past decades, and said the field is poised to move forward. A landmark paper in 1977 defined the modern management of TBI, and emphasized early diagnosis, surgical evacuation of intercranial mass lesions, use of artificial ventilation, control of

___________________

2 This section is based on a presentation by David Okonkwo, University of Pittsburgh.

increased intracranial pressure, and aggressive medical therapy (Becker et al., 1977). Okonkwo highlighted six patterns of computed tomography (CT) scans used as a biomarker and how the introduction in the 1970s of CT scans into intensive care unit (ICU) protocols is a key element in current TBI assessment. This is essentially where TBI management remains today, he added, 50 years later. While the needle is moving, the field is ready to move it much faster. The first blood biomarker test for concussion detection was cleared by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2018, using GFAP and UCH-L1.3 Then in 2021, a rapid test developed by Abbott in collaboration with DoD was cleared by FDA, also measuring biomarker proteins GFAP and UCH-L1 in plasma.4 Work is currently under way to develop a whole blood test that can more easily be used at the point of care, and Okonkwo noted that such a device could be a game changer.

Okonkwo looked to several other diseases for lessons on how biomarkers can transform the TBI field, noting the discovery of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) as a diagnostic marker for prostate cancer. Tests for PSA were quickly incorporated, and the mortality rate for prostate cancer has dropped by 50 percent since its adoption as a biomarker, he said. The changes from having effective biomarkers for TBI could be significant. While 192,000 people are diagnosed with prostate cancer each year in the United States, 2.8 million people are diagnosed with a TBI. As part of a pivot in this direction within the TBI field, he noted, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response is now partnering with the pharmaceutical company Abbott to undertake “aid in diagnosis” studies in adults and children that could broaden applications for Abbott’s current TBI assay and aid providers in diagnosing and understanding the severity of brain injuries. He also advocated for continuing to expand TBI biomarker uses in different clinical contexts and for additional indications.

In terms of what needs to be advanced right now, Okonkwo reviewed evidence that GFAP is an effective marker in TBI diagnosis, though he indicated the need for additional systematic vetting. Research is also elucidating the relationship between biomarker levels measured shortly after injury and long-term outcomes. Combining large datasets from consortia in Europe and North America and using cluster analyses, researchers are beginning to connect CT patterns and care practices for three types of TBI patients. The first is for addressing isolated epidural hematoma, which has

___________________

3 https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-marketing-first-blood-test-aid-evaluation-concussion-adults (accessed December 20, 2022).

4 https://abbott.mediaroom.com/2021-01-11-Abbott-Receives-FDA-510-k-Clearance-for-the-First-Rapid-Handheld-Blood-Test-for-Concussions (accessed December 20, 2022).

a well-established treatment (to surgically drain the blood and remove the hematoma). Because there are no clear strategies to improve outcomes in that population beyond the current standard of hematoma removal, those patients should not be put in clinical trials investigating alternative interventions. The second two patterns are for subdural hematoma/contusion and intraventricular hemorrhage, and clinical trials will need to focus on the differential implications of each.

Okonkwo argued that using imaging and blood-based biomarkers enables providers to be much more precise in their communication with and about TBI patients than the terms “mild, moderate, and severe.” Reflecting on the use of blood tests for troponin, described by Wu, such tests changed emergency cardiac response, guiding actions and facilitating the provision of interventions only for those who need them. Similarly in oncology, a patient who presents with metastatic breast cancer can undergo sophisticated molecular characterization of their tumors to better target therapies. For TBI in 2022, he said, the field is in a position in which a person who suffers head trauma can be evaluated with a blood test. For now, available blood biomarker tests require venipuncture, but ideally will reach the point of needing only a finger prick of blood. If the test is negative, the person can return to work and daily living. If biomarker levels are abnormal, providers will need to consider the next course of action and a CT scan may need to be ordered. While the field is in transition from innovators to early adopters of available TBI technologies, Okonkwo said, it is about to explode.

Looking to the future, Okonkwo envisioned a scenario in which a medevac helicopter carrying a TBI patient can use portable, wearable technologies that transmit electroencephalogram (EEG) data, along with measurement of blood biomarkers, collecting information to give providers in the hospital the most accurate picture of the patient’s state. Based on the patient’s results, he said, it may be possible for the helicopter to bypass the trauma bay and go straight to an operating room equipped with an interoperative CT scanner. While the University of Pittsburgh has tested such a system for research purposes, he believes it is coming soon to clinical practice.

Picking up on the use of pharmacodynamic response biomarkers for drug testing described by Kochanek, Okonkwo saw important future effects of biomarkers on clinical trials for new TBI therapies, using combinations of biomarkers, testing multiple drugs simultaneously, and gauging the effects of these treatments over the weeks afterward. Having the ability to understand and monitor treatment effects using biomarkers, he said, would radically change the game for TBI clinical drug trials, as well for TBI patient evaluation and diagnosis. He closed with a call for recruiting everyone to use the available biomarkers, so that over the next 5 years the indications and contexts of use for various biomarkers can be crowdsourced. Such efforts will collectively push the frontiers of the field forward.

Discussion

Actionable and rigorously evaluated information provided by preclinical consortia is needed as the field is looking for drugs to enter adaptive clinical trials, said Geoffrey Manley, University of California, San Francisco, who expressed a hope that additional preclinical research infrastructure might arise given that OBTT has ended. Kochanek added that an area ripe for further preclinical and clinical development is the use of blood biomarker measurements to confirm drug target engagement and as part of metabolomics analyses. Hoffman shared the news that preclinical work such as that undertaken by OBTT is now being carried on though the Pre-Clinical Interagency Research Resource-TBI (PRECISE-TBI) initiative,5 funded by VA in collaboration with DoD and the National Institutes of Health.

Picking up on the issue of clinical trial design, Okonkwo noted that there have been dozens of failed phase 3 clinical trials for drugs to treat TBI, often attributable to insufficient clarity coming out of the preclinical space. Many phase 2 trials have been insufficient to identify which drugs to push forward and how, he added, and the field needs to get trial design right. A participant added that in approaching clinical trials for TBI drugs, especially in earlier stages of phase 1 and phase 2, researchers should be open to updating trials in response to the latest information and to more quickly ditching things that are not working. It is not necessary to finish the entire study before deciding it is not working, he added.

The discussion turned to cultural changes that will be needed in clinical and research communities to embrace TBI biomarker advances. Okonkwo replied that TBI has long been referred to as a silent epidemic but is getting closer to the point where the “silent” modifier can be dropped. TBI is becoming a signature injury of modern warfare and national dialogue around sports concussions has resulted in TBI becoming a larger part of public conversations over the last 15 years. Although awareness of the scope of the problem has grown, he said, there is still an underappreciation for what the injury does to people and education continues to be vital. To see transformative effects will require being able to provide clinicians and patients with greater clarity about what can be done for a person who experiences TBI to support their optimal recovery.

___________________

5 https://www.precise-tbi.org (accessed March 10, 2023).

OPPORTUNITIES TO ADVANCE THE USE OF BIOMARKERS IN TBI CLASSIFICATION6

Frederick Korley, University of Michigan, introduced the panel and highlighted opportunities and challenges for implementing TBI biomarkers into routine clinical use, particularly how biomarkers could form part of an improved system for classifying TBI. In their remarks and discussion, he encouraged panelists to consider the range of biomarker types and to focus on markers having sufficient levels of evidence that they are likely to be ready for use within the next 5 years or so. Context matters, he said, and he also encouraged the panelists to couch their comments within identified contexts of use and to be clear about whether the biomarker is being used as a diagnostic, predictive, prognostic, or monitoring biomarker. Panelists each made brief opening remarks, followed by discussion.

Martin Schreiber, Oregon Health and Science University, focused on the use of biomarkers in TBI screening. Level 1 trauma centers have been operating at very high occupancy in the last few years, and the ability to use biomarkers as a screening tool would be hugely beneficial to their workflow, he noted. The use of TBI screening tests would also be valuable in rural areas, which often lack access to specialized trauma care. Knowing quickly which patients need to be transported to more specialized facilities is critical. Shifting to the other environment in which he works, forward military bases, Schreiber explained that TBI screening biomarkers will also be valuable tools for understanding who needs to be transported to higher levels of care or taken off duty, because such bases do not always have CT scanners.

Beth McQuiston, Abbott Laboratories, commended DoD for the decade of research on assessing brain injury using blood biomarkers such as GFAP or UCH-L1 and noted that DoD research on these markers underpins Abbott’s biomarker detection device, which is now an FDA-cleared, commercially available platform for certain uses. She emphasized the importance of understanding the details of which platform, version, assay methodology, and molecular form of a protein are being referenced when discussing the results of blood biomarker tests, because these factors affect the reference levels and results.

Allison Kumar, Arina Consulting, commented on the FDA clearance process for biomarkers. There are currently no FDA cleared biomarkers, she explained. Rather, the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health

___________________

6 This section is based on a panel discussion among Frederick Korley, University of Michigan; Martin Schreiber, Oregon Health and Science University; Beth McQuiston, Abbott Laboratories; Allison Kumar, Arina Consulting; Carol Taylor-Burds, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Travis Polk, Combat Casualty Care Research Program, DoD; and Narayan Iyer, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, HHS.

clears assays and devices that measure biomarker levels for clinical use. As McQuiston noted, such tests may use different underlying technologies and methodologies. FDA could implement a standardized way of collecting information for validating a particular biomarker to help in diagnosing a specific TBI patient population. This validation is where some of the key hurdles in translational research are encountered, she noted, because it is costly and difficult to conduct clinical studies that yield significant results on the highly heterogeneous TBI population. She added that it is not only TBI patients who need to be recruited to clinical studies, but also similar patients who are negative for a TBI, so that standards for biomarker sensitivity and specificity can be optimized.

Carol Taylor-Burds, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the National Institutes of Health, said that she was struck by the progress that has been made in TBI biomarkers but also by the number of possibilities still out there for better understanding the underlying pathophysiology of TBI, incorporating biomarkers into the system of classifying TBI, and identifying additional therapeutic targets. She saw opportunities for imaging and novel networks to inform the next areas of therapeutics development.

Captain Travis Polk, Combat Casualty Care Research Program, DoD, commented on the need for a biomarker taxonomy to indicate which markers are most appropriate to collect for which contexts of uses. The best biomarker on the planet in a research environment, he said, could be useless in a particular clinical environment. While there is an immediate need for biomarkers to triage who has a mild TBI and who does not, better understanding of the anticipated trajectory of recovery for more severe TBIs and what interventions are beneficial is also needed. Polk also raised the issue of polytrauma, in which a patient has a TBI as well as additional bodily injuries. Whether current blood biomarkers are accurate in patients who are bleeding heavily or who receive a blood transfusion needs to be better understood. Finally, Polk referenced work being done by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) through the Cornerstone Project to study the physiological and biochemical changes that occur immediately after a TBI to identify potential targets for countermeasures to prevent injury.7

Narayan Iyer, from BARDA at HHS reviewed its mission of developing medical countermeasures to threats against the civilian population. Any mass casualty event typically includes TBIs, he said, and BARDA is investing in tools and products that can be of use in both worst-case scenarios and day-to-day applications. BARDA recently announced funding to advance the use of TBI biomarkers as an aid-in-diagnosis and thus facilitate

___________________

7 https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2022-06-02 (accessed December 20, 2022).

their integration into real-world delivery of care for the civilian population. Ideally, progress in this area will help transform how biomarkers can be used beyond diagnosis and classification, including in therapeutic care and prognostication.

Discussion

Korley emphasized the need to draw on the information provided by the spectrum of biomarker classes, their contexts of use, and the diversity of populations experiencing TBI. One of the first challenges is how to incorporate biomarkers into a novel and more precise TBI classification system. Manley commented that the common classification terms mild, moderate, and severe have been hurting patients and there is an absolute need for more precise language. Studies have shown that 50 percent of people labeled as having “mild” TBI were not back to work by 2 weeks, and 17 percent were unemployed 1 year later (Gaudette et al., 2022). On the other hand, patients with severe TBI are often able to recover improved function. These blunt classification terms are hurting patients on both ends of the severity spectrum, he argued, and while a classification change will not happen overnight, incorporation of additional information from available biomarkers can change the way patients receive care.

Schreiber highlighted the gap between patients who have a positive CT scan and those who have a negative CT scan and are discharged without a TBI diagnosis but continue to suffer symptoms weeks or months later. Something to help patients who fall into this category is needed, and biomarkers have the potential to enable more sensitive screening for brain injuries not easily detectable by CT. Polk added that biomarkers may also be useful in better understanding and characterizing preinjury risk. Certain populations, including athletes and military servicemembers, are also at risk for repetitive concussive events. In thinking about TBI classification, he said, quantitative indicators or biomarkers that can measure change from baseline would be useful in these populations. Public–private partnerships among industry, academia, clinicians, and federal agencies such as FDA, BARDA, and DoD will be important in developing and implementing these biomarker tools and approaches, added McQuiston.

Understanding the reference ranges for TBI biomarkers and enabling calibration across different biomarker measurement platforms is important, said Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, University of Pennsylvania. When measuring cholesterol level as a biomarker, for example, normal and elevated ranges are the same regardless of platform used, and at some point, cross-calibration for TBI assays will be needed. It is not feasible for clinicians to keep track of all the different reference ranges for different manufacturers. Kumar added that the same issue exists in measuring troponin for cardiac

care, because every platform provides a different range. But which assay is used by a hospital is often determined by the hospital’s laboratory systems, and that will be difficult to standardize. This is an area in which clinicians, health systems, and industry need to collaborate, noted McQuiston. When laboratory results are pulled up on a patient’s electronic health record, reference ranges for different manufacturers and platforms could be built into the back end of the system, so that the clinical user sees whether the result is flagged as being normal or out of range. Developers can also work with FDA to give providers a readout in whichever format is most valuable to them, she said. Lastly, there may be different reference ranges for different clinical indications and intended uses, McQuiston added. For example, a goal of maximizing sensitivity versus specificity will result in setting cutoff levels differently. Kumar added that cutoff levels will also become apparent for different ages. Pediatrics has been an understudied population in this area, and ranges correlating to different severities of pediatric injuries may be different than ranges for adults.

Bruce Evans, fire chief at Upper Pine River Fire Protection District and member of the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians, highlighted the economics of getting biomarkers deployed in the field, especially in prehospital settings. He asked whether assays will be affected by issues such as extreme heat or cold, depending on where an ambulance might be stationed, and their potential for false positive or false negative readings. McQuiston replied that the testing Abbott conducted with DoD on its assay included performance criteria such as temperature. Kumar added that these concerns speak to the importance of choosing the correct biomarkers from which to build a product. A biomarker that measures inflammation needs to be able to distinguish between a patient with a brain injury and one with inflammation from another cause. Another participant added that overtriage can occur in military settings, with more people evacuated to receive CT scans than necessary, and that incorporation of blood-based biomarker tests as part of diagnosis is reducing unnecessary evacuations for mild TBI. Evans added that from a health economics standpoint, extrapolating these findings into the civilian market could have a significant return on investment.

Iyer added that BARDA measures the anticipated economic impact of its investments, considering the value of the care delivered and how cost changes affect care. Evans added that special consideration is needed for the prehospital space, because ambulances are reimbursed differently than the rest of the medical field. For something such as smoke inhalation injuries, ambulances receive about $250 for Medicaid transport, he explained, but companies set a device price of $1,300. At that cost, tests will not make it into the field because they are unaffordable. Similar discussions will be needed for TBI blood biomarker assays, he said. The profit will

be made from a high volume of use, given the millions of people assessed for TBI each year, but the price point for the tests cannot be set above what is reimbursable. Diaz-Arrastia said that prehospital research has been a gap. He suggested that a prehospital study, where EMS could collect blood within 15-30 minutes of a potential TBI to assess the performance of biomarkers in this real-world setting, would be useful.

Corinne Peek-Asa, University of California, San Diego, noted the discussions during the workshop on acute prehospital triage, and asked about the best ways to use biomarkers at later stages of the continuum of care, after someone has received a TBI diagnosis. Kumar replied that the next phase of biomarker research should extend “aid in diagnosis” results to understand the interpretation of available data for use in prognostication. Schreiber added that blood biomarker screening tests can now start to fulfill certain aspects of the spectrum of care for a patient. Further along the continuum, it would be helpful to have biomarkers that correlate with outcomes, enabling more informed decisions with the patient and family about how aggressive to be in treatment and about the person’s anticipated trajectory toward recovery.