Advances in the Diagnosis and Evaluation of Disabling Physical Health Conditions (2023)

Chapter: 8 Techniques for Digestive System Disorders

8

Techniques for Digestive System Disorders

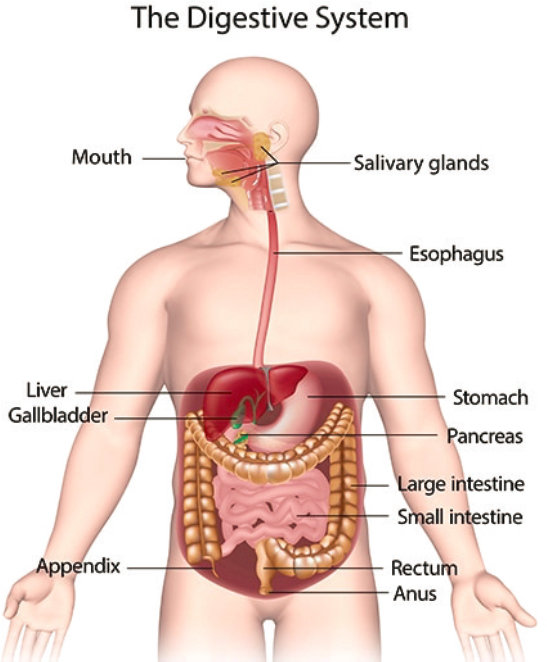

Gastroenterological conditions span a wide spectrum of disorders that affect the digestive system (see Figure 8-1), including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, liver, stomach, small and large intestines, gallbladder, appendix, and pancreas, and can range from mild to severe. Some digestive diseases and conditions are acute, lasting only a short time, while others are chronic, or long-lasting. Depending on the disorder’s severity, digestive system disorders may affect a person’s ability to work and function. Examples of these conditions include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which can include Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, as well as short bowel syndrome, malabsorptive syndrome/malabsorption, achalasia and other chronic gastrointestinal motility disorders, chronic anemia, liver disease, cirrhosis, chronic pancreatitis, uncontrolled diarrhea, and fecal incontinence.

Common techniques for diagnosing digestive disorders include clinical assessments, imaging techniques, scoring systems for measuring the severity of the disease process and quality-of-life measures, colonoscopy, upper GI endoscopy, capsule endoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic ultrasound, and, in some cases, laparoscopy or open surgery. Gastroenterologists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nutritionists, dietitians, primary care doctors, radiologists, and surgeons may all be involved in diagnosing a digestive disorder.

Multiple advances in electronics, nanotechnology, and imaging have significantly affected the practice of diagnostic and therapeutic gastroenterology. For example, the use of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in GI and abdominal imaging are becoming common practices and continue to evolve. In the use of non-surgical techniques

SOURCE: NIDDK (2023).

for examining the digestive tract, such as endoscopy, advances in wireless technologies have allowed a deeper and improved visualization of the GI tract and greater measurement of the physiologic parameters. The improved ability to identify digestive disease, including cancerous lesions, in the early stages can have a positive effect on prognosis and health outcomes.

This chapter provides information about select new and improved diagnostic and evaluative techniques in gastroenterology that have been introduced since 1990. It highlights major advances in testing that have generally resulted in better information about impairments that may affect patient functioning. Lastly, it identifies emerging digestive system techniques disabling conditions in the future.

OVERVIEW OF SELECTED TECHNIQUES

The committee reviewed advances in the diagnostic and evaluative techniques for digestive disorders, as shown in Box 8-1 (see inclusion criteria in Chapter 1). These techniques are categorized into those that assess anatomical or physiologic functions and those that assess functional performance or capacity at both the body function level and the activity

level. Some tests may measure one or the other. The chapter discusses the evidence and information about the selected techniques and responds to the requested items (a)–(j) of the statement of task for each technique. The focus is on disorders of the digestive system in Social Security Administration’s Listings of Impairments. These include “gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hepatic (liver) dysfunction, inflammatory bowel disease, short bowel syndrome, and malnutrition. They may also lead to complications, such as obstruction, or be accompanied by manifestations in other body systems.” The Cumulative List of Medical Diagnostic or Evaluative Techniques does not include any tests for gastroenterological conditions, presently. Following the descriptions of the selected techniques, the last section of the chapter outlines emerging techniques used in the assessment of individuals with serious digestive system disorders.

SELECTED DIAGNOSTIC TECHNIQUES FOR DIGESTIVE DISORDERS

The section describes advances in the diagnostic techniques used for assessing potentially disabling impairments of the digestive system. They are organized by imaging tests, endoscopic tests, and additional procedures. Refer to Chapter 3, Overview of Diagnostic and Evaluative Techniques, for background information about several of the techniques included here.

Imaging Tests

Multidetector Computed Tomography Scan

Computed tomography imaging is playing an increasing role in the evaluation of digestive system disorders (Liu, 2014). CT enterography (discussed in the next section) is a type of CT imaging optimized to produce detailed images of the small intestine and structures within the abdomen and pelvis. Newer techniques such as multidetector CT (MDCT) have become an important new tool for imaging suspected gastrointestinal and abdominal pathologies and have allowed for revolutionary improvements in temporal and spatial resolution when compared with the previous generation of CT scanners (Raman and Fishman, 2012). CT imaging is typically the initial imaging technique of choice for the evaluation of numerous pathologies, such as: gastrointestinal and intra-abdominal malignancies, bowel obstruction and bowel perforation, intra-abdominal sepsis, and small bowel disorders.

The requested information on MDCT for diagnostic capability is as follows:

- MDCT is often used as a follow-up diagnostic tool after an endoscopy. However, some studies have shown promise in the use of MDCT for the diagnosis of acute gastrointestinal bleeding (D. Kim et al., 2022). MDCT can also be used to diagnose and identify the location of a gastrointestinal tract perforation in patients (Pouli et al., 2020).

- Although CT imaging has the advantage of simultaneous detection of the extent of mural and extramural disease, advances in MDCT have allowed mucosal assessment by virtual endoscopy, and virtual colonoscopy can be used to detect colon cancer and colon polyps.

- In general, MDCT has had a direct impact on the quality of CT diagnosis in oncological imaging, in particular, the development of faster scanners with better spatial and temporal resolution (Raman and Fishman, 2012). This more complex approach and improved imaging has enabled more accurate assessment of the disease process (Raman and Fishman, 2012). The advances seen via MDCT have contributed to a real clinical impact on diagnosis and staging of gastrointestinal tumors, which is likely to become even more widespread as the technologies proliferate within radiology. The creation of detailed three-dimensional (3D) maps from this process has also allowed radiologists to see and understand the importance of lesions that may have been missed or disregarded in years past.

- MDCT was first introduced in 1998.

- CT scans are widely available, but disparities in access may reflect the access barriers to health care in general.

- The use of MDCT still has some disadvantages, including radiation exposure and a risk of contrast nephrotoxicity that may limit its use in some patients (Yen et al., 2012).

- The MDCT test assesses bleeding status and can identify patients with active bleeding or without. It also has been shown to be accurate in identifying the location of the bleeding in patients, such as the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum. Additional outcomes may include whether the source of bleeding is from an ulcer, cancerous growth, or variceal bleeding (D. Kim et al., 2022).

- See the section on imaging in Chapter 3 for information about standard requirements for administering CT scans.

- CT is widely used in the evaluation of gastrointestinal disorders. All radiologists are trained to interpret CT images.

- While virtual endoscopy can provide better mucosal details in some patients, it also comes with limitations such as greater time consumption and increased radiation dose needed (Nagpal et al., 2017). Additionally, for some situations the accuracy of MDCT is lower; for example, the accuracy is lower with colorectal perforations than with upper gastrointestinal tract perforations (H. Kim et al., 2014).

Magnetic Resonance Enterography and Computed Tomography Enterography

Magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) and computed tomography enterography (CTE) have become widely accepted methods for performing detailed evaluations of the small bowel in patients with Crohn’s disease (Guglielmo et al., 2020). Enterography refers to the oral administration of relatively large amounts of enteral contrast material to carry out the test, and in many places it has become the standard of care for evaluating patients with Crohn’s disease, small bowel malignancy, small bowel stricture, and other disorders of the small bowel.

The requested information for MRE and CTE related to diagnosis is as follows:

- In addition to evaluating patients with Crohn’s disease, both procedures can be used to monitor the progression of IBD and sometimes response to treatment. These tests have increasingly replaced the use of barium-based small bowel imaging to monitor patients. For example, at the Mayo Clinic in 2002, nearly all of the small bowel imaging used barium, but by 2010, 80 to 90 percent was done using CTE or MRE (Loftus, 2010).

- Many believe that MRE especially is superior to barium-based methods because of its improved diagnostic accuracy and assessment of disease activity (Radhamma et al., 2012). A 2010 European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease noted that MRE and CTE have the “highest diagnostic accuracy for the detection of intestinal involvement and penetrating lesions in Crohn’s disease” (Van Assche et al., 2010, p. 14). MRE has also been found to compare to colonoscopy for evaluation of Crohn’s disease in a noninvasive fashion (Grand et al., 2012).

- MRE is commonly used to evaluate the small bowel in patients with Crohn’s disease, but it is also a test that is used to see soft tissue problems. It can help diagnose and define strictures, small bowel obstructions, fistulas, and abscesses (Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2022a). CTE was first introduced in 1997 to perform a detailed examination of the small bowel and to assess the severity of Crohn’s disease (Ilangovan et al., 2012), whereas MRE was in use by 2012 in the UK (Radhamma et al., 2012).

- The committee is not aware of any disparities for this technique aside from generally known disparities in health care.

- Both MRE and CTE have largely replaced the fluoroscopic examinations or radiologic evaluations of the small bowel that were

- Both tests produce specialized imaging. CTE and MRE enable visualization of the thickness of the bowel wall and small intestine pathologies such as lesions, strictures, fistulas, and abscesses (VCU, 2022).

- MREs should be performed by MRI technologists or radiologists who can perform high-quality MRI scans of the abdomen (Baker et al., 2008). Often, a radiologist should directly supervise the examination, which can be difficult in busy practices.

- There are some barriers to more widespread use of both techniques. One limitation is cost, as MRE is more expensive than CTE (Loftus, 2010). There are fewer radiologists trained to interpret enterography images, specifically. Both techniques also require the patient to drink up to 2 liters of oral contrast before the exam, which may be difficult for some, and a few patients may require intravenous contrast, which could be problematic for certain patients as well. CTE specifically also comes with concerns about cumulative exposure to diagnostic radiation. While the absolute risk is still under debate, clinicians are more likely to use MRE for a younger patient because of this potential risk. One meta-analysis found that patients examined with CTE frequently are at a significantly increased risk of developing cancer because of this increased radiation exposure (Davari et al., 2019).

- The efficacy of these tests has been most studied in the detection and evaluation of Crohn’s disease. One study found the sensitivity of detection to be similar to that of ileocolonoscopy, and other research has found complications of Crohn’s to be detected with these methods with high accuracy (Baker et al., 2008). However, the efficacy of CTE in detecting the cause of conditions such as chronic small bowel blood loss has not been extensively studied.

previously conducted for similar indications. Fluoroscopy can deliver a significant radiation dose to the patient, whereas CTE delivers less and MRE none (Baker et al., 2008).

Positron Emission Tomography and Computed Tomography Scan

As described in Chapter 3, positron emission tomography (PET) and computer tomography (CT) scan are types of molecular imaging tests within nuclear medicine often used to detect cancers. The techniques were also discussed in Chapter 4, as they have utility in understanding cardiac and coronary pathophysiology. In this context, PET–CT scans are highly sensitive and trace a form of radioactive sugar as its absorbed by the body. Because cancer cells grow quickly, they take up larger amounts of sugar than normal cells. By 2000 this technique had become an essential modality

in the management of digestive system cancers, being used for diagnosis, staging, evaluation of treatment response, and assessment of prognosis (Beyer et al., 2000).

The requested information related to PET–CT and diagnostic and prognostic ability is as follows:

- The greatest value of PET-CT is that it can provide a scan of the entire body and allow for the detection of a localized malignancy and any metastases at distant sites (Vikram and Iyer, 2008). Hence, PET/CT is an important tool in the accurate staging of cancer and for determining the appropriate management and therapy options (Vikram and Iyer, 2008).

- PET–CT scans have demonstrated increased diagnostic and cancer staging accuracy when compared with either PET or CT alone (Fischer et al., 2016). For example, across different types of cancers the integration of PET with CT was 34 percent more accurate than diagnostic CT alone (Griffeth, 2005). Additionally, because of the high sensitivity of PET–CT scans, they can detect cancer sooner than other tests do.

- PET–CT can be used to diagnose various types of digestive system cancers. For specific, GI cancers, the International Atomic Energy Agency considers PET–CT appropriate for staging (IAEA, 2010).

- Since its introduction in 2000, PET–CT has become a widespread and effective imaging tool, and as of 2016 there were more than 5,000 systems in clinical operation globally (Fischer et al., 2016). Commercial PET–CT scanners were introduced in 2002 (Griffeth, 2005).

- Like many other nuclear medicine techniques, PET–CT units are typically located within urban centers and in hospitals with sufficient resources to procure and staff them. So those living in more rural areas have to travel long distances and are less likely to access this technique.

- Other more invasive tests, such as a colonoscopy and endoscopy are complementary to the PET-CT in the evaluation of GI malignancies, but they don’t allow for a full body exploration and are not ideal to conduct more frequently (Bhattaru et al., 2020). Additionally, compared to X-rays or MRIs, PET/CT scans allow visualization of abnormalities at the cellular level (Markman, 2021).

- Although the outcomes of these tests often show staging of certain cancers, there is not always a direct translation to what the health outcome of the patient will be. The interpretation of images is largely carried out through maximum standard uptake value (SUV) measurements. While this is not a hard cutoff, there are four

- The patient is asked to lie down on a table that slides into a large scanning machine. A small amount of radioactive sugar substance is injected through an IV, which allows the scanner to detect where the cancer might be and produce images. A technician who specializes in these scans will complete the test, and then the results will be read by a radiologist or nuclear medicine specialist.

- Although the clinical benefits of PET–CT have been well established, it has not been adopted as widely as many believe it could be. PET–CT coverage policies from insurance are variable and restrictive (Fischer et al., 2016). Additionally, there is not only the initial cost of procuring the machine, but also the added annual operational costs of human resources and maintenance, which can be a barrier to adoption. More personnel trained in the unit and biomedical engineers are also needed (Verduzco-Aguirre et al., 2019). Finally, another barrier to more widespread implementation is the need for positron emitting radiotracers, which need to be produced using a cyclotron (Verduzco-Aguirre et al., 2019). These tracers have a short half-life and emit high-energy radiation, which means they must be used quickly and also expose patients to certain levels of radiation.

- While the full body ability of PET–CT scans allows for wide detection of abnormalities, the resolution is low, and small tumors are difficult to visualize (Griffeth, 2005). To minimize radiation dosing, the CT portion of the combination scan is done at lower energy settings, but this results in lower-quality images than typical diagnostic CT scans. Additionally, patient motion, including respiratory motion, during the PET portion of the scan can lead to misregistration of organ activity and incorrect artifacts in the imaging (Jayaprakasam et al., 2021).

general categories to differentiate benign from malignant processes: SUV max < 2.5 = low uptake; SUV max 2.5–5 = intermediate uptake; SUV max > 5 = high uptake; and SUV max >10 = intense uptake (Ramzan and Tafti, 2022). There can also be false positives, which can occur from patient movement, or inflammatory uptake at sites of surgery, or false negatives because the tumor is the type that does not have a high uptake of the radioactive material (Ramzan and Tafti, 2022).

Magnetic Resonance Defecography

Defecography is an X-ray of the anorectal area that evaluates the completeness of stool elimination, identifies anorectal abnormalities, and evaluates rectal muscle contractions and relaxation. The test assesses the

complex and dynamic anatomical and functional changes of the rectum, the anal canal, and the pelvic floor during a bowel movement.

The requested information related to magnetic resonance defecography (MRD) and diagnostic ability is as follows:

- MRD is an alternative to conventional defecography that can dynamically visualize the pelvic floor. It can also be used to diagnose anal pain, constipation, fecal incontinence, pelvic floor dysfunction, and organ prolapse (Cleveland Clinic, 2022).

- The benefits of MRD compared with conventional X-ray defecography include the lack of radiation and the possibility of morphological analysis (Poncelet et al., 2017). It is also the only imaging modality that “can simultaneously evaluate global pelvic floor anatomy and dynamic motion” (Rao, 2010, p. 8). Given its good temporal resolution, high soft-tissue contrast, and lack of radiation exposure, MRD is the preferred imaging approach for pelvic floor dysfunction (Nikjooy et al., 2015). It has been identified as a good alternative to evacuation proctography.

- Common candidates for this test are patients with chronic intractable constipation, fecal incontinence, or rectal prolapse or those who are in need of post-surgical repair of anal or rectal anomalies or others with unexplained anal or rectal pain (Brennan et al., 2008).

- MRD was first introduced in 1993 (Ramage et al., 2018)

- The committee is not aware of any disparities for this technique aside from generally known disparities in health care.

- Conventional or fluoroscopic defecography had limitations such as radiation exposure, lower sensitivity, and an inability to visualize anterior and middle compartments. It was also unable to visualize other pelvic soft tissue or pathology (Kumra et al., 2019).

- Working with radio waves and a magnetic field, the MRD transmits a signal that can be interpreted as an image on a computer screen. Images are obtained at various stages of defecation and can show problems in the structure of internal organs.

- This type of MRD exam is performed by a certified radiologist who is specially trained to operate and interpret the test results and someone experienced in understanding anorectal motility. The patient will have barium paste injected into the anus until he or she feels the urge to defecate, and then the test is performed during this process (Cleveland Clinic, 2022).

- Impediments to more widespread uptake include a higher cost, lack of standardization, and poor availability at health centers. The test can also be difficult to complete due to patient compliance, as it

- Limitations of efficacy are also present, as MRD findings across several studies have not been found to correlate with patient-reported symptoms, making it a poor method for predicting the of severity of symptoms in pelvic floor dysfunction (Ramage et al., 2018).

involves various maneuvers for proper imaging as well as defecation in a supine position, which can be difficult for the patient (Kumra et al., 2019).

Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a medical imaging technique that which uses magnetic resonance to visualize the biliary tree and pancreatic ducts by non-invasive means to evaluate a wide range of pancreatobiliary diseases.

The requested information related to MRCP and diagnostic ability is outlined below:

- Clinically, MRCP is indicated for the identification of pancreatic and biliary malignancies, disorders of the biliary tract such as congenital anomalies of cystic and hepatic ducts, primary sclerosing cholangitis, disorders of the pancreas and pancreatic ducts such as pancreatic cysts, pancreas divisum, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, post-surgical complications, chronic pancreatitis, biliary injuries, and abnormal liver function.

- Several variations of the technique have been developed in recent years, and they all share the use of a heavily T2W pulse sequence, which displays static or moving fluid-filled structures as high-intensity areas (Gulati, et al. 2007). MCRP has been shown to be a reliable imaging technique when endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ECRP) is contraindicated or unsuccessful (Coakley and Schwartz, 1999).

- It is more sensitive than CT or ultrasonography in diagnosing common bile duct abnormalities (Lindenmeyer, 2022). It can also be used in the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases, and it has been found to have advantages in detecting stages of chronic pancreatitis (Goldfinger et al., 2020).

- First described in 1991, MRCP has evolved significantly over the past three decades, and it is now a non-invasive alternative to ECRP.

- The committee is not aware of any disparities for this technique aside from generally known disparities in health care.

- The main drawback to the previous technique used in these cases, ERCP, is that it is more invasive and brings with it increased

- There is significant variability between healthy individuals and those with hepatobiliary disease as measured with MRCP. The test measures regions of variation in duct diameter, total biliary tree volume, and areas of strictures and the presence of biliary stones (Goldfinger et al., 2020).

- MRCP is performed in a radiology suite equipped with an MRI scanner and staffed with licensed radiology technologists trained in MRI protocols. Tests should be interpreted by radiologists with expertise in imaging of the biliary tree and pancreatic ducts.

- Currently, MRCP is the best technique in clinical practice to assess changes in the main pancreatic duct and small ducts.

- MRCP has some limitations. For example, when conducting the test, providers may be faced with artifacts related to technique and reconstruction, normal variants that mimic pathology, intraductal factors, and extraductal factors—all of which may lead to difficulties in interpretation (Griffin et al., 2012). This reliance on qualitative and subjective assessment is a limiting factor of MRCP (Cazzagon et al., 2022).

morbidity and mortality risk due to the potential for perforation, bleeding, and infection upon exam (Kaltenthaler et al., 2006).

Transient Elastography

Transient elastography is a non-invasive method proposed for the assessment of hepatic fibrosis in chronic liver disease. It can be performed easily at the bedside or in outpatient clinics with immediate results. It has also been validated for the diagnosis of significant fibrosis, cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C, recurrence of hepatitis C after liver transplantation, and coinfections in certain patients (de Lédinghen and Vergniol, 2008).

The details related to diagnosis of liver conditions with transient elastography are as follows:

- Transient elastography is a special ultrasound technology that measures liver stiffness (hardness) and fatty changes.

- Transient elastography is a non-invasive test that provides benefit compared with liver biopsy, which was previously the gold standard to stage fibrosis in the liver. It is a test that can be performed at the point of care, does not require sedation, and does not inflict pain (Afdhal, 2012). Additionally, it is quick and takes only 5–7 minutes to perform, and the results are instantaneous.

- Transient elastography is a useful test in patients who require staging of their liver fibrosis. It can also be used to evaluate patients

- The first transient elastography device was cleared for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2013 but had been used in Europe for many years prior (ITN, 2013).

- Prior to FDA approval in 2013, transient elastography devices were widely adopted throughout Europe, Canada, South America, and Asia. They are now more available in the United States. While there are racial and ethnic disparities in the burden of liver disease, no disparities in access to this technology are documented.

- The biggest drawback of the previous gold standard, liver biopsy, is that it is a costly and invasive procedure, carries a risk of hemorrhage and organ perforation, and requires keeping the patient in the facility for several hours to monitor for potential complications. Additionally, a biopsy only samples a small piece of the liver, potentially giving a result that is not representative of the entire organ, which could lead to under- or overstaging of fibrosis (Afdhal, 2012). Due to this limitation, sampling errors have been found in up to 30 percent of liver biopsies.

- The range of outcomes for transient elastography testing is typically provided in liver stiffness measurements and controlled attenuation parameters (CAPs). CAP scores of 238–260 dB/m correlate to less than 33 percent of the liver affected by fatty change; 260–290 dB/m correlates to 34–66 percent affected; and 290–400 dB/m correlates to more than 67 percent of the liver affected (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 2022). Furthermore, liver stiffness scores can range from 2 to 19 kilopascals, with normal being between 2 and 7.

- Standard requirements for training are much less burdensome than needed for a liver biopsy, but typically a licensed health care specialist such as a gastroenterologist or hepatologist or a radiologist would perform the procedure.

- While this test is much easier to use, concerns still remain about the accuracy as compared with liver biopsies, possibly impeding more widespread use. A study in 2020 found the overall accuracy of transient elastography to be low when compared with liver biopsies (Ornelas et al., 2020). Other factors such as obesity, liver inflammation, and hepatic steatosis can also increase liver stiffness, contributing o errors in diagnosis.

- Pairing the transient elastography with other tests such as serum biomarker tests can result in increased confidence in the presence or absence of disease. For example, transient elastography and serum biomarker tests together can rule out cirrhosis.

with portal hypertension and assess disease recurrence following liver transplantation.

Virtual Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy is an endoscopic method of imaging the mucosa (inner lining) of the lower digestive tract (colon and terminal ileum) used to detect malignancies or polyps, diagnose inflammatory disorders, and identify the source of GI bleeding and anemia. In addition to being a diagnostic test, colonoscopy is also a therapeutic technique for removing polyps, making biopsies of abnormal tissue, and managing sources of GI bleeding. Virtual colonoscopy (or computed tomographic colonography) is a radiological diagnostic method that “combines conventional spiral computed axial tomography with virtual reality computer technology to assess the colonic mucosa for malignancies and polyps. The two-dimensional images generated by helical computed tomography are reconstructed into three-dimensional images by software that simulates the interior of the colon as it would be viewed through an endoscope.” (Moayyedi and Ford, 2002, p. 1401). Virtual colonoscopy is commonly used in colon cancer screening in patients where colonoscopy with sedation is contraindicated, when the patient has severe lung or heart disease, or when colonoscopy could not be completed for anatomical, technical, or patient safety reasons. However, virtual colonoscopy does not detect other mucosal pathologies such as inflammatory bowel disease or mucosal vascular pathologies.

The requested information on virtual colonoscopy for diagnosis is below:

- Virtual colonoscopy is commonly used in colon cancer screening in patients where colonoscopy with sedation is contraindicated or could not be completed, for example, because severe lung or heart disease prevents safe anesthesia use. It is also used in cases where an incomplete colonoscopy was performed because of a patient’s anatomy or a stricture of the colon. However, virtual colonoscopy is contraindicated in those with acute inflammatory conditions of the bowel.

- Virtual colonoscopy may be an alternative to traditional colonoscopy for some patients, and there is some evidence that the technology may be a pathway to better survival outcomes for some patients (Frankenfeld et al., 2020)

- Studies have suggested that virtual colonoscopies have greater accuracy for detecting colon polyps compared with barium enema examination and are close in accuracy to conventional colonoscopy (Halligan and Fenlon, 1999). However, the technique is less accurate than conventional colonoscopy in detecting small polyps, flat polyps, and polyps in patient with inflammatory bowel diseases.

- Virtual colonoscopy was first described in 1994, but as of 2005 it was not endorsed as a screening test for colorectal cancer and was not covered by third-party payers (Heiken et al., 2005).

- There is a recognized need to study structural issues such as differential access to or use of technologies or capabilities to better understand the pathway between race and colorectal cancer diagnosis and outcomes (Frankenfeld et al., 2020).

- The risks of colonic perforation with virtual colonoscopies are lower than with optical colonoscopies (Ganeshan et al., 2013); however, overall, perforation during a diagnostic colonoscopy is uncommon.

- Virtual colonoscopies detect the presence and size of polyps.

- In terms of administration of the test, the interpretation of results is dependent on the expertise of the radiologist, and the sensitivity and specificity of virtual colonoscopy when done by experts is much higher than when done by those who are less trained. Improvements in software, hardware, and radiologist experience in the technique are projected to improve the performance of the test overall.

- Although it is a technique that has been approved for screening and surveillance by the American Cancer Society and other organizations, it is not currently reimbursable for routine colorectal cancer screening in the United States (Ganeshan et al., 2013). This has likely held back its more widespread use by health systems nationwide.

- While its feasibility has been demonstrated, virtual colonoscopy requires more research with larger studies to better understand the scope of its application and utility. The disadvantages of CT colonography include exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation, which may increase the risk of malignancy. Finally, if a polyp is detected on a virtual colonoscopy, the patient will undergo a standard colonoscopy to remove the polyp (which entails repeat bowel prep, additional cost in time away from work, and costs associated with another procedure).

Endoscopic Tests

Diagnostic methods in gastroenterology are now increasingly characterized by direct visual inspection and tissue sampling (Mallery and Van Dam, 2000). Advances in endoscopic imaging are enabling clinicians to detect subtle, small mucosal variations that were previously undetected and indistinguishable from normal tissue (Graham and Banks, 2015). Endoscopy is an effective diagnostic technique for some GI disorders that previously

required more invasive techniques (Mallery and Van Dam, 2000). Additionally, many techniques also now have a digital component that augments the testing even further with supportive imaging.

Endoscopic Ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a noninvasive procedure that examines the walls of upper (esophagus, stomach, duodenum) and lower (rectum) gastrointestinal tract. It can also be used to look at nearby organs, such as the mediastinum, liver, gall bladder, and pancreas. In 2000 it was called the most clinically significant technological advancement in endoscopy in the past 10 years.

The requested information for use of EUS for diagnosis is as follows:

- EUS is used to evaluate abnormalities and malignancies detected at a prior endoscopy or found on imaging tests such as a CT scan. It is often used to characterize and stage lesions and to biopsy lesions of the upper GI tract or rectum and surrounding organs such as the pancreas and lymph nodes (Friedberg and Lachter, 2017). EUS can also be used in the work-up of pancreatitis, a pancreatic cyst or mass, and other causes of abdominal pain. It is also used to screen asymptomatic individuals at risk for pancreatic cancer.

- A benefit of EUS is that it can use higher-frequency sound, which provides greater image resolution (Mallery and Van Dam, 2000). This high level of resolution is unique to EUS. It is also able to readily perform diagnostic tissue sampling.

- Specific indications for EUS in diagnosis or monitoring are divided into categories of GI malignancy staging, pancreaticobiliary disease evaluation, and subepithelial or extraluminal abnormality evaluation (Reddy and Willert, 2009).

- EUS was developed in the 1980s but did not have a critical role in gastroenterology until the introduction of fine needle aspiration in 1991 (Friedberg and Lachter, 2017). Since then EUS has become increasingly used and has continued to advance, especially in the characterization of lesions.

- The committee is not aware of specific disparities for this technique. However, because of the high cost to maintain and repair EUS machines, they are mainly available in larger academic centers and less often in community hospitals. This can lead to access disparities similar to others seen in health care.

- The drawbacks of previous techniques include the limited ability of standard transcutaneous ultrasounds to produce adequate images because of interference by air filled structures. Similarly, ultrasound

- The outcomes depend on the type of EUS test used. For example, an upper endoscopy procedure is an EUS procedure that examines the upper part of the digestive tract, while a lower EUS procedure examines the lower part of the digestive tract.

- EUS, a procedure performed by specially trained endoscopists, uses a thin, flexible tube with a miniature ultrasound probe that goes in through the patient’s mouth or the rectum. To prepare for this, the patient should fast before the appointment and may need to follow a liquid diet combined with laxatives prior to the test to clear the intestine (ASGE, 2022).

- A study in 2009 found that clinicians reported the lack of trained endosonographers and high cost of the EUS scope and processor to be barriers to wider use (Kalaitzakis et al., 2009). Similarly, maintenance and repair of EUS equipment has been found to be highly expensive, making it another consideration when opening or managing a unit (Mekky and Abbas, 2014).

- One of the limitations of EUS and tissue sampling is that it can be difficult to confidently exclude a malignancy due to mimicking from chronic pancreatitis (Mallery and Van Dam, 2000).

has also been limited in utility because of interference from the air-filled lungs (Mallery and Van Dam, 2000). While another technique, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, is highly accurate for the diagnosis of common duct stones, EUS has been found to be equivalent in accuracy but more cost-effective and less invasive.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (also called EGD or upper GI endoscopy) is a procedure to examine the inside of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum with an endoscope. EGD is important in the diagnosis and treatment of esophageal, gastric, and small-bowel disorders. The endoscope is guided into the mouth and throat, then into the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. The endoscope allows the endoscopist to view the inside of this area of the body as well as to insert instruments through the scope for the removal of a sample of tissue for biopsy and for therapeutic intervention (e.g., the removal of a lesion or stenting to relieve obstruction).

The requested information for use of EGD for diagnosis is as follows:

- Typical indications for an EGD include patients with abdominal pain or upper GI bleeding, esophagogastric malignancies, and dysphagia from a variety of causes that can be relieved by the procedure (Mallery and Van Dam, 2000). It can also be used to identify

- The diagnostic and therapeutic potential of EGD is increasing with improvements in endoscopic instrumentation and image processing (Cappell and Friedel, 2002).

- Specific impairments that indicate a diagnostic EGD include persistent abdominal pain, bloating, dysphagia, odynophagia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, persistent vomiting with unknown cause, chronic diarrhea, caustic ingestion, weight loss, anemia, GI bleeding, and liver cirrhosis; it is also used for surveillance for malignancy in patients at high risk (Ahlawat et al., 2022).

- The test was developed well before 1990 and has been widely used since (Mellinger, 2003)

- In terms of disparities, one study reported preliminary data showing that compared with rural hospitals, urban hospitals’ EGD procedures were associated with higher rates of complications (e.g., respiratory failure, sepsis) (Merza et al., 2021)

- Previous endoscopes used fiber-optic bundles to transmit images, but they were small and quite limited in resolution, making it difficult to truly see the details of any abnormalities. Additionally, the endoscopes were larger in diameter, which made the procedure more uncomfortable for the patient and challenging to perform.

- During the EGD procedure, diagnostic biopsies can be performed as well as therapies to achieve hemostasis and to dilate strictures.

- Trained endoscopists—either adult or pediatric, depending on the population—should perform endoscopic procedures. If sedation is needed, personnel trained in life support and airway management should also be available.

- EGD is widely used, and nothing is known to be preventing its further uptake in clinical practice.

- Some limitations do exist, as it might not be possible to perform a complete EGD, with exam of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, if the patient has retained food in the stomach or if there is a mass or a stricture or altered anatomy that prevents the passage of the scope.

problems such as tumors, Celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, or infections in the upper GI tract (Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2022b).

Additional Techniques

In addition to imaging tests and types of endoscopies, there are other techniques, such as high-resolution manometry, prognostic scoring systems, and genetic testing, that clinicians use to evaluate a patient’s gastrointestinal tract and diagnose disorders of the digestive system.

High-Resolution Manometry

Various manometry tests are used to measure the muscle movements and muscle tone of the gastrointestinal tract, most often to investigate disorders of the esophagus when patients complain of symptoms such as dysphagia, regurgitation, heartburn, or chest pain. Esophageal manometry can be done using conventional manometry or high-resolution manometry (HRM). HRM uses pressure sensors and is more accurate at assessing pressure changes than conventional manometry testing. Outcome studies have just begun to demonstrate how the increased knowledge generated by HRM has influenced patient care, including the introduction of novel therapies (Gilja et al., 2007).

The requested information on HRM as a diagnostic procedure is as follows:

- Specific manometry testing includes esophageal manometry (to assess reflux and swallowing disorders), small bowel or antroduodenal manometry (to assess small bowel motility), and anorectal manometry (sphincter muscles). A pressure sensor in a catheter is positioned into the gastrointestinal tract, or, in the case of anorectal manometry, the catheter is placed into the anorectum. The pressure sensors record measurements of nerves and muscle activity in the area of the body being evaluated.

- HRM has been seen as one the most notable recent advances in the field of esophageal function and is a replacement technology making conventional manometry obsolete. It can provide a detailed analysis of the physiology of peristalsis and sphincter function (Gilja et al., 2007), and the insights from the increased number of pressure sensors allow greater diagnostic classification and more options for therapeutics (Gilja et al., 2007). Compared with conventional manometry, there is some evidence that HRM may detect more patients with achalasia, a rare, chronic esophageal motility disorder (Samo et al., 2017)

- The advantages of HRM over conventional manometry include a single probe position encompassing the entire esophagus, negating the need to reposition the probe during study. It has also allowed for the characterization of achalasia subtypes with distinct prognosis and has established a hierarchy of motility disorders. Compared with its predecessor, conventional manometry, improvements in HRM include a more user-friendly application for the provider and more accurate data collection. One study found that HRM provided superior diagnostic accuracy compared with conventional manometry (Carlson et al., 2015).

- HRM saw widespread adoption in the early 2000s, with many expecting it would add a level of precision to diagnoses of esophageal diseases that was not previously possible (Kahrilas et al., 2017).

- The committee is not aware of any disparities in access to HRM aside from generally known disparities in health care. Ethnic minorities and people of low socioeconomic status who have impaired access to health care in general would hence also have less access to these methods.

- Drawbacks of conventional manometry include increased chances of incorrect catheter positioning and a need for repeated repositioning to assess the entire esophagus. It was also more difficult to perform because the procedure time was longer. The interpretation of results also relied on more subjective assessments from experts, which can now be done with computer algorithms, reducing the learning curve for experts and trainees (Hoeij and Bredenoord, 2016).

- The range of outcomes that HRM can diagnose includes disorders of esophagogastric junction outflow, such as achalasia subtypes I–III and esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction; major disorders of peristalsis, such as absent contractility, distal esophageal spasm, hypercontractile esophagus; and other minor disorders of peristalsis.

- During a HRM procedure, a catheter is placed transnasally and positioned to span the length of the esophagus. It requires a series of seven to ten water swallows in supine or seated position (Yadlapati, 2017). Interpretation will rely on adequate training and the competency of physicians (Kahrilas et al., 2017).

- Despite its other improvements over the conventional manometry, HRM still requires special expertise and training, is more expensive, and allows room for overinterpretation of results if analyzed by those who are inexperienced. This has potentially impeded more widespread use.

- Furthermore, studies have found that at least 20 percent of patients with swallowing disorders have normal findings on HRM with symptoms or outcomes (Xiao et al., 2014).

Scoring Systems for Mortality Risk and Associated Disability

Table 8-1 summarizes two new and improved instruments that are widely used by medical professionals for characterizing disease progression and determining prognosis the risk of death in the near future for patients with liver disease. The diagnostic evaluation of patients with liver cirrhosis is an important topic in the field of organ transplantation. Accurate prognosis of patients with cirrhosis can decrease the mortality of patients on

TABLE 8-1 Examples of Scoring Systems for Mortality Risk and Disability in Liver Disease

| Tool or Measure (Evidence) | Accepted Uses/Impairments Assessed | Advancement/Limitations of Previous Techniques | Estimated Date Available | Range of Outcomes | Limitations of Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) Calculator (Abdalla et al., 2019; Kaplan et al., 2016; Tsoris and Marlar, 2022) |

A calculator using five lab values to predict severity of cirrhosis. Assesses severity and long-term survival with cirrhosis. | Modified in 2016 to improve ability to predict transplant-free survival | First developed in 1964, modified several times, most recently 2016 | Score of 5–6 points shows good hepatic function; 7–9 points moderately impaired; 10–15 points advanced deficits in hepatic function. Scores can predict mortality after transplant. | The test relies on two subjective assessments. It can also not be used to predict response to treatment using antivirals in “difficult to treat” patients. |

| Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) Score (Gotthardt et al., 2009; Kamath et al., 2001) |

Prognostic model to assess the severity of cirrhosis, organ allocation for liver transplant, etc. | Has a broad range of continuous variables, so was created to account for shortcomings of CTP calculator. Correlates significantly with the degree of liver functional impairment |

2001; updated for organ allocation use in 2016 | Scores range from 6 to 40 based on current condition. Larger increase in score can be due to infection or worsening of disease. The higher the score, the more often blood tests are needed. | MELD score has been criticized for variations in serum creatinine measurements and shown to be inferior to CTP score. Has been found to be limited in value for long-term prediction of mortality or removal of liver transplant patients from waiting list. MELD score can underestimate the severity of liver disease in women. |

waiting lists and improve posttransplant survival. While posttransplant survival can be predicted on the basis of the data-driven Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), the factors associated with posttransplant functioning are less well established (NASEM, 2021). Nonetheless, an advanced (>12) MELD score (which is associated with poor or limited function), or a score of C on the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) calculator (which is associated with a 55 percent mortality at 1 year), are likely associated with severe disability (Samoylova et al., 2017).

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing in digestive system diseases will typically be done for the diagnosis of a genetic syndrome, such as cystic fibrosis, a condition that cause chronic dysphagia and recurrent or chronic pancreatitis; to assess the risk of developing certain digestive disorders (e.g., cancer); to assess for a hereditary genetic syndrome in patients with a personal or family history of GI or non-GI malignancies; or to assess chances of responding to certain therapies (like cancer therapies and other), which can have implications for patient functioning and overall survival. Genetic testing in general is indicated when establishing a genetic diagnosis can have important implications for medical management and monitoring. Testing for germline mutations, which predispose individuals to syndrome-associated neoplastic manifestations, may be indicated in patients at increased risk for a hereditary cancer syndrome (Syngal et al., 2015). Genetic testing for a broad scope of applications is becoming increasingly available, but the analysis and interpretation of results remains complex, requiring specialized expertise, and it can be challenging to communicate the results to patients.

The requested information for genetic testing’s use as a diagnostic technique is as follows:

- Current genetics tests are available for the following GI disorders: colon cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, pancreatic endocrine tumors, pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, metabolic liver disease, and hyperbilirubinemias (Goodman and Chung, 2016).

- Before the advent of genetic testing, there was limited ability to determine whether a person was likely to have certain conditions based on hereditary factors.

- Regarding gastroenterological disorders, there are certain diseases or conditions that can be confirmed through genetic testing. These include celiac disease, hereditary hemochromatosis, lactase insufficiency, hereditary pancreatitis, and monogenetic types of IBD (Concept Genetics, 2022).

- Genetic testing became more widely available in the early 2000s, with numerous tests possible for GI conditions by the 2010s (Goodman and Chung, 2016).

- Given the high cost of most genetic tests and the variability of insurance coverage, limitations in access are seen in populations of lower socioeconomic status and in those in rural areas already lacking access to robust health care.

- Prior to genetic testing there were no similar tests that could identify a person’s genetic predisposition to a certain disease.

- The range of outcomes for genetic testing usually includes whether or not a person has an identified gene that plays a role in that particular disease process or has a mutation in a certain gene. Numerous genes may be implicated in a certain disease or condition, but how much they influence the likelihood of a person developing the disease remains unclear.

- The performance of the test itself is often straightforward and can be easily done through a blood test, either at home or with a trained phlebotomist. However, the regulations governing the analysis and processing of the tests continue to develop. With the growth of direct-to-consumer testing, there is concern that unregulated tests present a public health threat.1

- Currently, the cost of genetic testing is still high, preventing more widespread use. However, the number of commercial laboratories and companies offering these services has been increasing over the last decade, which will likely bring the costs down and make this type of testing more available for a larger number of people. Time is also a limitation, as it can still take several weeks for results to be shared from commercial entities.

- While there have been numerous genes identified that are associated with certain diseases, the presence of a gene or mutation does not always predict whether a person will develop that disease. So, the usefulness of the testing is limited to confirmation when paired with other tests and symptom identification. Additionally, as the use of these tests increases, researchers predict that incidental findings in asymptomatic patients will also increase. These will often be inconclusive, as they may flag a variant or mutation that is unrelated to the suspected disease, which can place undue emotional burden on the patient (Goodman and Chung, 2016).

___________________

1 Details on the regulatory guidance are beyond the scope of this report, but more details can be found here: https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/policy-issues/Regulation-of-Genetic-Tests.

SELECTED EVALUATIVE TECHNIQUES FOR DIGESTIVE DISORDERS

Often, clinical judgments in digestive disorders are based on patient-reported symptoms in addition to data from objective diagnostic tests. Symptoms can lead to functional consequences that can prevent people from working. As discussed in chapters 2 and 3, the evaluation of symptoms can involve both patient-reported outcomes and clinical scales to assess severity of disease and how well a person can function. Patient-reported outcomes measure any aspect of patient-reported health (e.g., physical, emotional, or social symptoms) and can help to direct care and improve clinical outcomes. Table 8-2 provides examples of measures created to assess symptoms and functioning in patients with specific digestive disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease and other digestive system conditions. Such patient-reported outcomes capture the patients’ illness experience in a structured format. Using patient-reported outcomes can effectively aid in the detection and management of conditions, improve satisfaction with care, and enhance the patient–provider relationship (Spiegel, 2013).

EMERGING DIAGNOSTIC AND EVALUATIVE TECHNIQUES

This section reviews the major emerging breakthroughs in the field of gastroenterology that will likely influence how digestive disorders are diagnosed and evaluated in the coming years. Key techniques include artificial intelligence (AI), novel biomarkers, predictive algorithms, and portable sensors.

Artificial Intelligence

Together, AI and machine learning (ML) have the potential to bring major improvements to the diagnosis and evaluation of digestive system conditions. For example, the use of AI in GI endoscopy can reduce inter-operator variability, enhance diagnostic accuracy, and reduce the time and cost of endoscopic procedures (El Hajjar and Rey, 2020). Computer-assisted diagnosis for optical biopsy is one of the main systems of AI application. Studies have shown that this system has great promise for improving the detection and diagnosis of esophageal adenocarcinoma, which, when diagnosed early, can benefit from curative treatment. Many systems are also in development to assess various colon diseases. The use of AI during colonoscopies can assist in the diagnosis of polyps via “optical biopsy.” Diagnostic AI assistance can also be used in IBD patients to predict persistent histological inflammation in ulcerative colitis patients with 91 percent accuracy (Maeda et al., 2019). While some of these systems, such as those

for cancer diagnosis, will require more research and testing before they will be ready for clinical use, computer-assisted diagnosis for colon polyps is currently being introduced in clinical practice (Hajjar and Rey, 2020).

As discussed previously, the accurate diagnosis of IBD relies on a combination of clinical data, image and colonoscopy assessments, and inflammatory markers. Prognosis (assessing if a patient with IBD will develop IBD-related complications during the course of the disease) and monitoring the response to different therapies for IBD still require the identification of reliable biomarkers to understand which patients are at higher risk of disease progression and which therapeutic mechanism of action is best suited for each patient. The personalization of therapy and management will improve the outcomes of patients with IBD (Stankovic et al., 2021). Finally, identifying patients at risk of developing IBD before they develop symptoms will allow the development of proactive preventive strategies. AI can help integrate the data of the many environmental and socioeconomic factors as well as the genetic susceptibility genes to help detect patients at risk of developing IBD and to help risk-stratify patients with a diagnosis of IBD. It can also play a role in prognosis for chronic liver disease. For example, in a study by Segovia-Miranda and colleagues, ML was used to analyze bile canalicular features along with biliary flow dynamic simulations to effectively identify pathobiological processes in early nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and characterize the transition from simple steatosis to NASH (Segovia-Miranda et al., 2019).

Since the mapping of the human genome, many new technologies have emerged that enable the measurement of biological molecules that are involved in the structure, function, and dynamics of a cell, tissue, or organism (IOM, 2012). These fields are often referred to as “omics” and can include proteomics, metabolomics, epigenomics, and many others. Several different types of tests related to “omics data” have been FDA-approved for clinical application, but the robust analysis of this type of big data will rely on AI and ML. Integrating all of the different types of data would likely improve the understanding of IBD pathology and management, and ML offers a way to handle the high dimensionality of these data with a goal of translating results into clinical practice. However, predictive models still need to be rigorously tested in various cohorts and settings to truly determine whether they can be beneficial.

Novel Biomarkers

In addition to numerous efforts using AI and ML, novel serum biomarkers for chronic liver disease are also being explored in various cohorts to spot the presence of early disease or identify patients with a high risk of disease progression. Researchers in the United Kingdom are specifically

TABLE 8-2 Examples of Patient-Reported Outcomes and Clinical Scales for Digestive Disorders

| Tool or Measure (Evidence) | Description | Impairments Assessed/Accepted Uses | Advancement/Limitations of Previous Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| GASTROINTESTINAL | |||

|

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Disability Index (IBD-DI) (Peyrin-Biroulet et al., 2012; Plebris and Lees, 2022) |

28-item questionnaire that measures disability in inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease) | General health; environmental factors; sleep, energy, body image, pain, and other symptoms. | First tool to specifically assess IBD disability at a given time, including to follow changes in disease burden over time for monitoring treatment efficacy. |

|

IBD Disk (Ghosh et al., 2017; Le Berre et al., 2020; Paulides et al., 2019) |

10-item questionnaire that is an adaptation of IBD-DI. Includes domains of joint pain, abdominal pain, regulation of defecation, interpersonal interactions, education and work, sleep, energy, emotions, body image, and sexual functions. | Abdominal pain; regulating defecation; interpersonal interactions; education and work; sleep; energy, emotions; body image; sexual functions; joint pain | Designed for use during the clinical visit to give immediate visual representation of patient-reported IBD-related disability. Easier and faster to complete than the IBD-DI. |

| Est. Date Available | Range of Outcomes | Disparities In Access | How It Is Adminstered/Standard Requirements Governing Use | Limitations of Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Based on 0–4 Likert scale. For the validated French version with 14 items, the mean score was 35. | Difficult to self-administer | Administered by a health care professional; mainly for use in the clinical trial setting. Studies have demonstrated its use as an outcome measure in clinical trials and prospective epidemiological studies. | Poor correlation with objective markers of endoscopic inflammation; can be cumbersome to calculate in clinical practice |

| 2017 | Overall score calculated as sum of 10 components, ranging from 0 to 100. Good correlation of IBD Disk score with daily life burden. | Unknown | Self-administered in clinical practice. Can be useful in remote monitoring. | The tool lacks assessment of clinical activity to confirm relationships with disease burden and QoL. |

| Tool or Measure (Evidence) | Description | Impairments Assessed/Accepted Uses | Advancement/Limitations of Previous Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| GASTROINTESTINAL | |||

|

GI-PROMIS (Almario et al., 2016; Kochar et al., 2018; Spiegel et al., 2014) |

The National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a standardized set of patient-reported outcomes that cover physical, mental, and social health (Spiegel et al., 2014). GI symptom domains added as a 60-item questionnaire include gastroesophageal reflux (13 items), disrupted swallowing (7 items), diarrhea (5 items), bowel incontinence/soilage (4 items), nausea and vomiting (4 items), constipation (9 items), belly pain (6 items), and gas/bloat/flatulence (12 items). | Applicable across a range of GI diseases and conditions | The domains selected were strongly associated with disease activity and quality of life indices for IBD patients, providing a method of measuring quality of life and severity of disease more objectively |

|

SHORT HEALTH SCALE (SHS) (McDermott et al., 2013; Park et al., 2017) |

A four-part visual analogue scale questionnaire using open-ended questions that are designed to assess the impact of inflammatory bowel disease on health-related quality of life. The four dimensions include bowel symptoms, activities of daily life, worry, and general well-being. | IBD, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis | Previous measures did not take into account patient well-being and focused on biological burden of IBD. Previous scales also asked extensive questions about specific symptoms and activities. This one is shorter and easier to complete, also open-ended so patients can customize better to their context. |

| Est. Date Available | Range of Outcomes | Disparities In Access | How It Is Adminstered/Standard Requirements Governing Use | Limitations of Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Mean score is 50, with SD of 10. Higher scores denote more symptoms, except social satisfaction, where a lower score indicates better satisfaction. | Uptake is not always equal across populations. In one study, African Americans were 56% less likely to complete the questionnaire prior to their visit. As these telehealth portals increase in use, the reasons driving these disparities need to be better understood. | Can be employed in clinical settings (in person or virtual) and research/clinical trials | A randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact in clinical practice found no differences in patient satisfaction or assessment of shared decision making. |

| 2006 | Has been validated across several populations/countries. Found a reliable measure of health related QoL. | Questions broadly applicable to diverse patients with varying demographics. | Quick and easy to administer, taking less than 1 minute. | Unknown |

| Tool or Measure (Evidence) | Description | Impairments Assessed/Accepted Uses | Advancement/Limitations of Previous Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESOPHAGEAL DISEASE | |||

|

Eckardt Symptom Score (ESS) (Botoman, 2019; Taft et al., 2018) |

Four-item self-report assessment tool for achalasia to drive clinical management decisions. Is most widely used tool as of 2018 | Assesses severity of symptoms of achalasia. | Simpler to use than other achalasia symptom scoring models |

|

Northwestern Esophageal Quality of Life Scale NEQOL (Bedell et al., 2016) |

14-item single scale measure of health related quality of life. Acts as a “hybrid” measure that can be broadly used but maintains sensitivity. | Applicable across several chronic esophageal conditions, e.g., GERD, EoE, achalasia, dysphagia. | Previous measures make it difficult to isolate true impact of disease on QoL; most also were not transportable across clinical and research settings. |

|

Adult Eosinophilic Oesophagitis Quality of Life (EoO-QOL-A) (Lucendoet al., 2018: Taft et al., 2011) |

37-item measure (later refined to 30) structured by 5 dimensions: eating/diet impact, social impact, emotional impact, disease anxiety, and choking anxiety. | Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) | Other generic health-related quality of life measures could not express multiple concerns about the condition people with EoE have. |

NOTE: EoE = eosinophilic esophagitis; GERD = gastroenterological reflux disease; GI = gastrointestinal; IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; QoL = quality of life; SD = standard deviation.

| Est. Date Available | Range of Outcomes | Disparities In Access | How It Is Adminstered/Standard Requirements Governing Use | Limitations of Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | Assigns 0–3 points for four symptoms of disease (dysphagia, regurgitation, chest pain, and weight loss). Scores of 0–1: clinical stage 0; 2–3: Stage I; 4–6: Stage II; and more than 6: Stage III. Final scores range from 0 to 12. | Achalasia is a rare disease, may require formal diagnosis to have access to this type of assessment. | Used in clinical and research settings to grade symptom severity; self reporting scale | The ESS has fair reliability and validity, but certain items in the tool may be decreasing it’s reliability, so further assessment warranted; the “weight loss” item has the weakest correlation with other measures. |

| 2016 | Each item rated on 5-point Likert scale (very true–not true at all). Each item is coded 0–4, with total score summing all items. | Unknown | Can be used as rapid assessment tool of health-related QoL in clinical settings. For research, other disease-specific measures are preferred over NEQOL until further evaluated across samples. | Additional validation needed. Samples in initial study were primarily Caucasian and highly educated, needs validation in more diverse patient populations. |

| 2011 | Scores for every item range from 0 (very good QoL) to 4 (very poor QoL). The final score is a weighted average of all dimensions. Recurrent food impaction affected most dimensions, and female gender exclusively affected diet dimension. | Many patients suffering from EoE have diagnosis delays of several years, so that could keep them from accessing this type of measure. | Can self administer; useful for clinical practice and research. | Multi-center studies with more diverse patient samples are needed. Test has only been validated for those with a formal diagnosis. |

examining serum biomarkers of fibrogenesis, genetic markers of fibrosis, and imaging and platform “omics” technologies (Bennett et al., 2022).

Predictive Algorithms

Advances have been made in developing diagnostic techniques and algorithms that can identify and risk-stratify individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its more progressive form, NASH. While diagnostic tests are available to accurately diagnose advanced liver disease, early diagnosis remains an ongoing challenge, and until recently no widely available non-invasive diagnostic test was able to distinguish between NAFLD and NASH. But there have been an extensive number of publications released recently and new therapeutic targets identified, with the common themes of a deeper understanding of disease pathogenesis, new and improved diagnostic and staging tools, and moving closer to FDA-approved therapies (Abdelmalek, 2021). Additionally, high-definition medicine has become an accepted approach to profiling and restoring a person’s health using analytical and therapeutic technologies, including geometric modeling.

For example, for the noninvasive identification of patients with significant NASH and liver fibrosis, a score using transient elastography was developed recently to identify those patients at increased risk of disease progression. A model using liver stiffness measurement by vibration-controlled transient elastography, controlled attenuation parameter, and aspartate aminotransferase had the best predictive properties for NAFLD and associated injury (Newsome et al., 2020). The score resulted in better discrimination than existing tests, but more research is needed to transition the use of the test to primary care. Approaches like these can enable other quantitative tools that could diagnose early disease or assess disease progression (Abdelmalek, 2021). This could also help to identify new biomarkers for diagnosis and prediction of which patients will progress to negative outcomes of disease.

Portable Sensors

Another novel method is the use of a portable magnetic resonance sensor with histological validation to stage steatosis and fibrosis in preclinical models. In one study such a portable sensor accurately predicted steatosis and fibrosis grade in ex vivo mouse livers and accurately quantified the fat fraction in human livers (Bashyam et al., 2021). While traditional MRI has clearly demonstrated its utility and accuracy for many conditions, its cost and requirements for facilities makes it a difficult tool to scale more widely or use as an ongoing longitudinal screening option. This type of

portable sensor offers similar abilities with the advantage of being used at point of care to monitor disease progression and potentially enable earlier diagnosis. See Chapter 3 for more information about the use of digital technologies in clinical medicine.

REFERENCES

Abdalla, T. M., S. M. A. Monem, and H. M. Dawod. 2019. Value of Child-Turcotte-Pugh score in prediction of treatment response in “difficult to treat” chronic HCV cirrhotic patients. Open Journal of Gastroenterology 9(11):211–222.

Abdelmalek, M. F. 2021. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Another leap forward. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 18(2):85–86.

Afdhal, N. H. 2012. Fibroscan (transient elastography) for the measurement of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology & Hepatology 8(9):605–607.

Ahlawat, R., G. J. Hoilat, and A. B. Ross. 2022. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy. In StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532268/ (accessed August 14, 2022).

Almario, C. V., W. D. Chey, D. Khanna, S. Mosadeghi, S. Ahmed, E. Afghani, C. Whitman, G. Fuller, M. Reid, R. Bolus, B. Dennis, R. Encarnacion, B. Martinez, J. Soares, R. Modi, N. Agarwal, A. Lee, S. Kubomoto, G. Sharma, S. Bolus, and B. M. R. Spiegel. 2016. Impact of National Institutes of Health gastrointestinal PROMIS measures in clinical practice: Results of a multicenter controlled trial. American Journal of Gastroenterology 111(11):1546–1556.

ASGE (American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy). 2022. Understanding EUS (endoscopic ultrasonography). https://www.asge.org/home/for-patients/patient-information/understanding-eus (accessed November 20, 2022).

Baker, M. E., D. M. Einstein, and J. C. Veniero. 2008. Computed tomography enterography and magnetic resonance enterography: The future of small bowel imaging. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery 21(3):193–212.

Bashyam, A., C. J. Frangieh, S. Raigani, J. Sogo, R. T. Bronson, K. Uygun, H. Yeh, D. A. Ausiello, and M. J. Cima. 2021. A portable single-sided magnetic-resonance sensor for the grading of liver steatosis and fibrosis. Nature Biomedical Engineering 5(3):240–251.

Bedell, A., T. H. Taft, L. Keefer, and J. Pandolfino. 2016. Development of the Northwestern Esophageal Quality of Life scale: A hybrid measure for use across esophageal conditions. American Journal of Gastroenterology 111(4):493–499.

Bennett, L., H. Purssell, O. Street, K. Piper Hanley, J. R. Morling, N. A. Hanley, V. Athwal, and I. N. Guha. 2022. Health technology adoption in liver disease: Innovative use of data science solutions for early disease detection. Frontiers in Digital Health 4:737729.

Beyer, T., D. W. Townsend, T. Brun, P. E. Kinahan, M. Charron, R. Roddy, J. Jerin, J. Young, L. Byars, and R. Nutt. 2000. A combined PET/CT scanner for clinical oncology. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 41(8):1369–1379.

Bhattaru, A., A. Borja, V. Zhang, K. V. Rojulpote, T. Werner, A. Alavi, and M.-E. Revheim. 2020. FDG–PET/CT as the superior imaging modality for inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 61(Suppl 1):1159–1159.

Botoman, V. A. 2019. Functional assessment of achalasia. Journal of Xiangya Medicine 4:16.

Brennan, D., G. Williams, and J. Kruskal. 2008. Practical performance of defecography for the evaluation of constipation and incontinence. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI 29(6):420–426.

Cappell, M. S., and D. Friedel. 2002. The role of esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the diagnosis and management of upper gastrointestinal disorders. Medical Clinics of North America 86(6):1165–1216.

Carlson, D. A., K. Ravi, P. J. Kahrilas, C. P. Gyawali, A. J. Bredenoord, D. O. Castell, S. J. Spechler, M. Halland, N. Kanuri, D. A. Katzka, C. L. Leggett, S. Roman, J. B. Saenz, G. S. Sayuk, A. C. Wong, R. Yadlapati, J. D. Ciolino, M. R. Fox, and J. E. Pandolfino. 2015. Diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders: Esophageal pressure topography vs. conventional line tracing. American Journal of Gastroenterology 110(7):967–977.

Cazzagon, N., S. El Mouhadi, Q. Vanderbecq, C. Ferreira, S. Finnegan, S. Lemoinne, C. Corpechot, O. Chazouillères, and L. Arrivé. 2022. Quantitative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography metrics are associated with disease severity and outcomes in people with primary sclerosing cholangitis. JHEP Reports 4(11):100577.

Cleveland Clinic. 2022. Defecography. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22333-defecography (accessed February 10, 2023).

Coakley, F. V., and L. H. Schwartz. 1999. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 9(2):157–162.

Concept Genetics. 2022. Genetic testing: Gastroenterologic disorders (non-cancerous). https://www1.radmd.com/media/1004390/genetic-testing_-gastroenterologic-disorders-noncancerous-v220222.pdf (accessed November 20, 2022).

Davari, M., A. Keshtkar, E. S. Sajadian, A. Delavari, and R. Iman. 2019. Safety and effectiveness of MRE in comparison with CTE in diagnosis of adult Crohn’s disease. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran 33(1):1–10.

de Lédinghen, V., and J. Vergniol. 2008. Transient elastography (FibroScan). Gastroenterologie Clinique et Biologique 32(6 Suppl 1):58–67.

El Hajjar, A., and J. F. Rey. 2020. Artificial intelligence in gastrointestinal endoscopy: General overview. Chinese Medical Journal 133(3):326–334.

Fischer, B. M., B. A. Siegel, W. A. Weber, K. von Bremen, T. Beyer, and A. Kalemis. 2016. PET/CT is a cost-effective tool against cancer: Synergy supersedes singularity. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 43(10):1749–1752.

Frankenfeld, C. L., N. Menon, and T. F. Leslie. 2020. Racial disparities in colorectal cancer time-to-treatment and survival time in relation to diagnosing hospital cancer-related diagnostic and treatment capabilities. Cancer Epidemiology 65:101684.

Friedberg, S. R., and J. Lachter. 2017. Endoscopic ultrasound: Current roles and future directions. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 9(10):499–505.

Ganeshan, D., K. M. Elsayes, and D. Vining. 2013. Virtual colonoscopy: Utility, impact and overview. World Journal of Radiology 5(3):61–67.

Ghosh, S., E. Louis, L. Beaugerie, P. Bossuyt, G. Bouguen, A. Bourreille, M. Ferrante, D. Franchimont, K. Frost, X. Hebuterne, J. K. Marshall, C. O’Shea, G. Rosenfeld, C. Williams, and L. Peyrin-Biroulet. 2017. Development of the IBD Disk: A visual self-administered tool for assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 23(3):333–340.

Gilja, O. H., J. G. Hatlebakk, S. Odegaard, A. Berstad, I. Viola, C. Giertsen, T. Hausken, and H. Gregersen. 2007. Advanced imaging and visualization in gastrointestinal disorders. World Journal of Gastroenterology 13(9):1408–1421.

Goldfinger, M. H., G. R. Ridgway, C. Ferreira, C. R. Langford, L. Cheng, A. Kazimianec, A. Borghetto, T. G. Wright, G. Woodward, N. Hassanali, R. C. Nicholls, H. Simpson, T. Waddell, S. Vikal, M. Mavar, S. Rymell, I. Wigley, J. Jacobs, M. Kelly, R. Banerjee, and J. M. Brady. 2020. Quantitative MRCP imaging: Accuracy, repeatability, reproducibility, and cohort-derived normative ranges. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 52(3):807–820.

Goodman, R. P., and D. C. Chung. 2016. Clinical genetic testing in gastroenterology. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology 7(4):e167.

Gotthardt, D., K. H. Weiss, M. Baumgärtner, A. Zahn, W. Stremmel, J. Schmidt, T. Bruckner, and P. Sauer. 2009. Limitations of the MELD score in predicting mortality or need for removal from waiting list in patients awaiting liver transplantation. BMC Gastroenterology 9:72.

Graham, D. G., and M. R. Banks. 2015. Advances in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. F1000Research 4:F1000 Faculty Rev-1457.

Grand, D. J., V. Kampalath, A. Harris, A. Patel, M. B. Resnick, J. MacHan, M. Beland, W. T. Chen, and S. A. Shah. 2012. MR enterography correlates highly with colonoscopy and histology for both distal ileal and colonic Crohn’s disease in 310 patients. European Journal of Radiology 81(5):e763–e769.

Griffeth, L. K. 2005. Use of PET/CT scanning in cancer patients: Technical and practical considerations. Proceedings (Baylor University Medical Center) 18(4):321–330.

Griffin, N., G. Charles-Edwards, and L. A. Grant. 2012. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography: The ABC of MRCP. Insights into Imaging 3(1):11–21.

Guglielmo, F. F., S. A. Anupindi, J. G. Fletcher, M. M. Al-Hawary, J. R. Dillman, D. J. Grand, D. H. Bruining, M. Chatterji, K. Darge, J. L. Fidler, N. S. Gandhi, M. S. Gee, J. R. Grajo, C. Huang, T. A. Jaffe, S. H. Park, J. Rimola, J. A. Soto, B. Taouli, S. A. Taylor, and M. E. Baker. 2020. Small bowel Crohn disease at CT and MR enterography: Imaging atlas and glossary of terms. Radiographics 40(2):354–375.