Substance Misuse Programs in Commercial Aviation: Safety First (2023)

Chapter: 2 Brief Descriptions of the Human Intervention and Motivational Study and the Flight Attendant Drug and Alcohol Program

2

Brief Descriptions of the Human Intervention and Motivational Study and the Flight Attendant Drug and Alcohol Program

This chapter provides a brief description of two prominent drug and alcohol programs overseen by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). These programs, the Human Intervention and Motivational Study (HIMS) and the Flight Attendant Drug and Alcohol Program (FADAP), support pilots and flight attendants, respectively, who misuse substances and who have substance use disorders. This chapter describes both programs’ structures. An analysis of program engagement, outcomes, and effectiveness will be provided in Chapter 5. The discussion starts with the applicable regulatory principles governing the alcohol and substance use programs in aviation, followed by a general description of each program that includes the treatment service delivery process—identification, referral, treatment provider selection and placement, and continuing care/recovery support services; return-to-duty procedure; program monitoring; and workplace outcomes measurement.

REGULATORY CONTEXT: SUBSTANCE MISUSE PROGRAMS IN THE AVIATION SECTOR

The regulatory principles that govern substance use programs in the aviation industry come from the FAA and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 14 CFR § 120 outlines FAA policies designed to prevent accidents and injuries resulting from the misuse of drugs or alcohol by employees in aviation with safety-sensitive functions.1 These

___________________

1 https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/chapter-I/subchapter-G/part-120

regulations state which employees must be tested, which substances they must be tested for, and when these tests should occur. Administrative procedures for these tests are also described, as are the consequences for employees that fail a test.

While the general FAA rules and definitions apply to many aviation employees, pilots have separate rules and definitions for problematic substance use. Becoming a commercial carrier pilot (also called an Airline Transport Pilot) for a major U.S. airline usually requires possessing a first-class airman2 medical certificate; therefore, it is those highest standards that are the focus of the committee’s work.3 This medical certification includes a record of the pilot’s behavioral health history, including substance dependence or abuse (14 Code of Federal Regulations [CFR] § 67.107).4 If there is a history of substance dependence, there must be established clinical evidence of recovery, defined as complete abstinence from the substance for not less than the preceding two years (14 CFR § 67.107).5 It should be noted that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) does not define recovery from substance use disorders, nor is there a consensus on what clinically constitutes recovery and how to measure it.

The programs are also informed by regulations related to the specific credentials a professional must possess to be qualified to assess and determine the return-to-duty process for safety-sensitive transportation employees. For example, U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Rule 49 CFR § 40.281(o) outlines the credentials, basic knowledge, qualification training, and continuing education needed to become a Substance Abuse Professional (SAP) for the DOT.6,7 Additionally, given the confidential nature of pilots’ and flight attendants’ participation in these programs, 42 CFR § 2.32, within the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) at HHS imposes restrictions on the disclosure and use of patient records for substance use disorder patients, which are maintained as part of any federally assisted program and establishes a

___________________

2 “Airman” is an FAA term and refers to pilots of all genders.

3 For a summary of the different medical standards by pilot class, see https://www.faa.gov/ame_guide/standards

4 https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/chapter-I/subchapter-D/part-67/subpart-B/section-67.107

5 After a prepublication version of the report was provided to the FAA, this section was edited to clarify abstinence duration.

6 The credential of a SAP was created by the DOT to clarify who is qualified to assess their employees. It is a credential that providers have to obtain if they want to perform evaluations on transportation employees.

criminal penalty for violation of these restrictions.8 These regulations form a foundation that the HIMS and FADAP are able to build on.9

HIMS

Definitions and Sources of Information

According to the FAA (2023a), there are approximately 167,000 commercial airline pilots flying for major carriers (e.g., United, American, Delta, Southwest), small carriers (e.g. Frontier, JetBlue, Spirit), regional airlines (e.g., Republic, CommuteAir, Envoy) and cargo carriers (e.g., FedEx, UPS, Atlas Air, Kalitta). In addition to the licensing and certifications necessary to fly aircraft, pilots are required to hold medical certification. Specifically, pilots flying for the aforementioned airlines are required to hold first class medical certification as defined by 14 CFR § 67. Section 67.107 addresses mental health, with 14 CFR § 67.107(a)(4) specifying substance dependence as a disqualifying condition:

- Substance dependence, except where there is established clinical evidence, satisfactory to the Federal Air Surgeon, of recovery, including sustained total abstinence from the substance(s) for not less than the preceding 2 years. As summarized in this section -

- “Substance” includes: Alcohol; other sedatives and hypnotics; anxiolytics; opioids; central nervous system stimulants such as cocaine, amphetamines, and similarly acting sympathomimetics; hallucinogens; phencyclidine or similarly acting arylcyclohexylamines; cannabis; inhalants; and other psychoactive drugs and chemicals; and

- “Substance dependence” means a condition in which a person is dependent on a substance, other than tobacco or ordinary xanthine-containing (e.g., caffeine) beverages, as evidenced by one or more of the following -

- Increased tolerance;

- Manifestation of withdrawal symptoms;

- Impaired control of use; or

- Continued use despite damage to physical health or impairment of social, personal, or occupational functioning.

14 CFR § 67.107(b) further defines substance abuse as a disqualification but with the proviso that the pilot can resume duties if free of abuse for the preceding two years:

___________________

8 https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-I/subchapter-A/part-2

9 The committee acknowledges that potential changes could be coming to the regulations: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/regulatory-initiatives/hipaa-part-2/index.html

-

No substance abuse within the preceding 2 years defined as:

- Use of a substance in a situation in which that use was physically hazardous, if there has been at any other time an instance of the use of a substance also in a situation in which that use was physically hazardous;

- A verified positive drug test result, an alcohol test result of 0.04 or greater alcohol concentration, or a refusal to submit to a drug or alcohol test required by the U.S. Department of Transportation or an agency of the U.S. Department of Transportation; or

- Misuse of a substance that the Federal Air Surgeon, based on case history and appropriate, qualified medical judgment relating to the substance involved, finds -

- Makes the person unable to safely perform the duties or exercise the privileges of the airman certificate applied for or held; or

- May reasonably be expected, for the maximum duration of the airman medical certificate applied for or held, to make the person unable to perform those duties or exercise those privileges.

The regulatory definitions of substance dependence and abuse differ from the current Text Revision of DSM-5 (DSM-5-TR; see American Psychiatric Association, 2022) while still capturing key elements of substance misuse. The DSM-5 criteria for a diagnosable substance use disorder require at least two of the following symptoms in a given year:

- using more of a substance than planned, or using a substance for a longer interval than desired;

- inability to cut down despite desire to do so;

- spending substantial amount of the day obtaining, using, or recovering from substance use;

- cravings or intense urges to use;

- repeated usage that causes or contributes to an inability to meet important social or professional obligations;

- persistent usage despite user’s knowledge that it is causing frequent problems at work, school, or home;

- giving up or cutting back on important social, professional, or leisure activities because of use;

- usage in physically hazardous situations, or usage causing physical or mental harm;

- persistent use despite the user’s awareness that the substance is causing or at least worsening a physical or mental problem;

- tolerance (needing to use increasing amounts of a substance to obtain its desired effects); and

- withdrawal (a characteristic group of physical effects or symptoms that emerge as the amount of substance in the body decreases).

The FAA’s regulatory definitions of substance abuse and dependence are notably more restrictive than the accepted clinical guidance. Moreover, the FAA considers substance abuse within the last two years or, substance dependence regardless of timeframe, as grounds for disqualification from medical certification (14 CFR § 67.107).10 Additionally, the regulatory environment requires strict enforcement by the FAA; as a result, identification of a substance use disorder places the pilot’s job and livelihood at risk. This unique environment for pilots stands in sharp contrast to other occupations, where identification and treatment of substance use disorders is of lower risk to employability. The environment leads to considerable reticence to disclose one’s own struggles or those of a fellow pilot. Nevertheless, pilots face challenges including easy access to alcohol, especially on layovers, difficult travel schedules, isolation, and high stress levels, particularly when away from support networks.

The following sections outline the history and organization of HIMS. Sources of information include the HIMS website,11 written responses to inquiries from the HIMS Program Manager, HIMS Overview slides presented at conferences, and content from the HIMS Basic Seminar (Snyder, 2022).

Special Issuance Authorization

With the introduction of HIMS in 1974, a mechanism was developed for identifying and treating substance use disorders, along with a system for monitoring and returning to duty. Although the conditions of substance dependence and abuse are still considered disqualifying, 14 CFR § 67.401 provides for Authorization for Special Issuance of a Medical Certificate at the discretion of the Federal Air Surgeon. This authorization can be issued to pilots who demonstrate that they can perform their duties without endangering public safety. The creation of HIMS allowed for pilots diagnosed with substance abuse and dependence to pursue treatment and to eventually make a return to the flightdeck, supplanting prior practice of pilots being dismissed.

Because the medical certification of pilots is key to maintaining the safety of aircraft, passengers, and employees, HIMS is primarily framed as a safety program designed to ensure that the adverse effects of a pilot’s substance misuse do not pose an undue risk (Snyder, 2022). For pilots, however, it represents a way to maintain medical certification and employment and return to flight duties. HIMS standards currently apply across all three classes of medical certification for pilots.

___________________

10 After a prepublication version of the report was provided to the FAA, this section was edited to accurately reflect the information found in the CFR.

Program Design and Structure

There is no central administration of HIMS beyond the FAA-funded core elements of educational programming (aimed primarily for airlines and medical professionals), maintaining a database of participants, and serving as an overall substance misuse information hub, although there are commonalities in HIMS structure across airlines designed to meet the requirements of the FAA’s special issuance process. Commonalities include the referral-to-treatment, monitoring, and return-to-duty processes. The specific structure of each program differs according to each airline’s arrangements with its pilots, often made through collective bargaining agreements (Snyder, 2022). As such, the various pilot unions and companies have considerable autonomy in how they carry out the expectations of the program.

The cornerstone structure of the typical HIMS team within an airline comprises the HIMS-trained aviation medical examiner (HIMS AME), the company, the pilot’s union, and mental health professionals. While the pilots’ unions contribute to the structure of HIMS at a given airline, the company often maintains the managerial functions and assumes financial responsibility for the treatment (through their provided insurance) and for monitoring components of the program. Some airlines use their Employee Assistance Program (EAP) in the initial referral/identification process as well as in the ongoing monitoring phase of the program. However, because of the variability among carriers and pilot unions, financial support for the pilot in treatment varies greatly. Regardless of the structure within and between airlines, the HIMS process is ultimately guided by the HIMS AME or medical sponsor and on the advisement of the mental health professionals including the HIMS-trained psychiatrist and neuropsychologist (P&P). See Figures 2-1 and 2-2 for the operating model and oversight structure of HIMS.

Identification and Referral to the Program

Pilots can enter HIMS in a variety of ways. Initial identification of whether a pilot meets the regulatory definition of substance abuse or dependence can be initiated by FAA request following a report of a substance-related arrest, substance-related medical event, or other information that may suggest a substance-related issue (Snyder, 2022). Pilots can also enter the program through a variety of other pathways, including self-referral, referral by the airline/supervisor, or on the recommendation of their AME. Regardless of the referral mechanism, entering the program may depend on the identification of a substance use issue that meets the regulatory definitions of abuse or dependence. Pilots may also be referred to the program following a positive test result during random DOT testing, which accounts

SOURCE: Data from https://himsprogram.com/ and responses to the committee questionnaire to HIMS.

SOURCE: Data from https://himsprogram.com/ and responses to the committee questionnaire to HIMS.

for approximately eight percent of all pilots entering the program. Entry into the program can also be facilitated by a family member or coworker.

Regardless of the mechanism of referral, in many instances a formal assessment by a SAP is conducted. These initial evaluations are performed by professionals in disciplines knowledgeable in the assessment and treatment of substance use disorders such as psychiatry, psychology, and social work or by other licensed masters-level clinicians holding the DOT required qualifications to become a SAP. In addition to the ability to make a clinical diagnosis, the clinician must be trained in and be familiar with the FAA’s regulatory standards and definitions.

Program Introduction and Awareness

Program awareness can vary from airline to airline. All pilots are free to attend HIMS seminars, which are multiday events bringing together pilots, AMEs, and other program stakeholders to train and discuss their experiences. In addition, airline pilots are introduced to HIMS through a 20–60-minute training segment on HIMS during initial-hire and annual trainings. HIMS also distributes literature, including employee manuals, publications to unions, and brochures, as well as merchandise.

Treatment Modalities and Monitoring

Neither HIMS nor the FAA require admission to any specific treatment facility. Selection of treatment centers is at the discretion of the airline or union that manages a HIMS. Initial treatment types and settings vary. First class pilots most commonly enter treatment at the residential level and length of stay is based on a 28-day model; detox is completed if needed. Following this initial treatment episode, all classes of pilots most commonly transition into the aftercare level of treatment, continuing with group therapy once per week and periodic contact with a psychiatric provider and individual therapist (Snyder, 2022).

Aftercare and monitoring are considered essential components for maintaining sobriety. The HIMS aftercare component typically coincides with the initiation of the aftercare level of treatment. In addition to the formal treatment noted above, it commonly includes meetings with peer pilot monitors, company representatives, and EAP staff, as well as engagement in mutual help programs such as 12-step programs, most commonly Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). Birds of a Feather, available to pilots and flightdeck crew members across the world, is an AA-based mutual support group pilots are encouraged to participate in.12

___________________

12 For more information on Birds of a Feather, see www.BOAF.org

The monitoring phase begins following the initial treatment phase, coinciding with HIMS aftercare, and continues after the special-issuance authorization. Monitoring follows a step-down process with monitoring requirements gradually reduced over the course of several years (Snyder, 2022). However, in a small number of cases, monitoring may continue for the duration of a pilot’s career. Monitoring includes both regular and random drug and alcohol testing13 as well as ongoing contact with the company representatives/EAP, peer monitors, psychiatric providers, and the HIMS aeromedical examiner. It also includes attendance at mutual support groups. Open communication among the monitoring entities is encouraged and, in some companies, is formally convened.

Throughout treatment and monitoring, peer and company monitors, as well as treatment providers, are responsible for generating monthly reports, which are included in the pilot’s submission package for Special Issuance and follow-up monitoring. This monitoring model is intended to actively address the risk of relapse.

Evaluation for Fitness for Duty

The pilot’s HIMS team plays an essential role in determining the pilot’s quality of recovery and subsequent readiness for evaluation for fitness to return to flight duties. Continuing cognitive impairment related to substance misuse and poor recovery is a common reason for prohibiting a pilot from proceeding to the evaluation for fitness for duty. Premature referral for evaluation can cause a subsequent delay, a return to further treatment, and need to repeat all or part of the neurocognitive assessment. Once a determination has been made to proceed with evaluation, the pilot is referred to a P&P for assessment of psychiatric and neurocognitive status. Each evaluator is provided with complete records, including the pilot’s full FAA medical record and all treatment and monitoring records.

As HIMS has evolved, the neurocognitive testing process has evolved. The neuropsychological assessment utilizes a battery of standard and commonly used measures that have been validated for aeromedically significant cognitive functions such as deductive reasoning, working memory and attention, processing speed and efficiency, verbal and visual memory, and general intellectual functioning. Aspects of these cognitive abilities are also considered to be vulnerable to chronic substance misuse.

Following completion of these assessments, the pilot is either referred for further treatment or cognitive rehabilitation activities or recommended for consideration for special issuance certification. If recommended for further consideration, the pilot is medically evaluated by the HIMS aeromedical

___________________

13 Including remote monitoring systems such as Soberlink.

examiner, and the final submission package is assembled. That package includes all documentation including treatment records, monitoring reports, and P&P reports. The medical sponsor is responsible for assembling the records and generating a comprehensive summary for submission to the FAA for final determination of eligibility for special issuance authorization.

Special Issuance

Authorization for a special issuance is contingent on the pilot following certain requirements. In the near term, continued monitoring is required, including random drug and alcohol testing, continued individual and/or group therapy, meetings with peer monitors, follow-up with the HIMS aeromedical examiner/sponsor and HIMS psychiatrist, and continued engagement in a peer support/12-step program. A HIMS step-down process was approved in 2020 that gradually reduces monitoring requirements over a minimum of seven years.

HIMS Summary

HIMS is a safety-oriented program designed to facilitate the identification, treatment, monitoring, and return-to-duty of pilots with substance abuse and dependence as defined by 14 CFR § 67. While the broad goals and FAA special issuance authorization standards are consistent, the program’s implementation can vary between carriers. Additionally, the treatment of substance use disorder can constitute significant expense of time and money. While mutual help groups such as AA are free and have no attendance requirements, more time spent in meetings is related to higher rates of abstinence (Kaskutas, 2009). Residential inpatient treatment cost an average of $42,500. (French et al., 2008). Oftentimes only pilots at major carriers with strong unions who support HIMS will be provided with necessary financial support. Smaller carriers with more limited budgets may leave pilots with much less financial support for treatment and more limited leave from work. A lack of financial support can be a significant barrier to entering treatment, especially among pilots at smaller and regional carriers.14 Reliance on temporary disability coverage, sick leave, or a total lack of support may impact the pilot’s decision to engage in treatment and even treatment effectiveness.

Another barrier to entering HIMS (and, subsequently, treatment) is the unique medical certification requirements that pilots must meet to exercise

___________________

14 Information from a committee-hosted public workshop, available https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/11-01-2022/workshop-on-dealing-with-substance-use-disordersand-strengthening-well-being-in-commercial-aviation

pilot privileges. Identification of a disqualifying condition places the pilot’s medical certificate and, in turn, the pilot’s career and livelihood at risk. As a result, pilots may be disincentivized to reveal that they are affected by substance use, even if HIMS may otherwise help them pursue treatment.

Another component worthy of further study is the small number of residential treatment facilities treating pilots who will eventually apply for special issuance medical certification. The HIMS Program Manager noted that there are approximately a dozen treatment facilities across the United States approved to treat HIMS participants, though there are more than 11,000 substance use disorder treatment facilities in the United States (Cantor et al., 2022).

HIMS further notes that many facilities are unwilling to engage with airline HIMS teams during and after treatment to generate the documentation necessary for FAA review as part of the final determination process. This makes it difficult to expand the “roster” of treatment facilities to which HIMS can refer their pilots. It is unclear how much of a barrier the small number of treatment facilities poses or how a treatment program gets approved by airlines.

Finally, the HIMS Advisory Board approved the development of a confidential database with the stated goal of identifying areas for improvement in HIMS.15 The database and data collection are funded by the FAA as a part of the HIMS contract with the Air Line Pilots Association, International.16 While all data are de-identified, the database is for internal use only and reviewed annually by three individuals at the FAA and HIMS.17 Searchable fields in the HIMS database include age cohort, size of airline, method of entering program, primary substance, dual diagnosis, number of relapses, and family history.18

FADAP

Flight attendants are responsible for ensuring cabin safety. They conduct safety checks before the flight and ensure effective communication of safety procedures with customers, as well as operate safety devices, as needed, in times of emergency. In addition to commonly known risk factors for developing substance use disorders, flight attendants also face challenges unique to their work environment that increase susceptibility to relapse and that can be triggering during recovery. Like pilots, flight attendants also face challenges including easy access to alcohol, difficult travel schedules,

___________________

15 HIMS staff response to the committee-issued questionnaire, August 2022.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

isolation, and high stress levels, particularly when dealing with difficult customers and being away from personal supports. It is critical, therefore, that impairment among flight attendants be addressed in a timely and appropriate manner so that safety-sensitive duties are not compromised.

FADAP’s stated mission advances a culture of safety among flight attendants by addressing impairment through awareness of substance misuse and by supporting their personal and professional goals by allowing self or peer referrals to seek treatment (FADAP, n.d.). Hence, the program may be viewed as having two distinct components: (1) an educational component and (2) a treatment-referral and recovery-support component.

According to FADAP staff,

early surveys conducted of flight attendants in 2012 and 2013 showed that approximately 10 to 12 percent of flight attendants are engaged in misuse/abuse behaviors around alcohol, drugs, and medications. Within all DOT safety-sensitive groups for aviation, flight attendants ranked either first or second for DOT drug test violations across various testing reasons (pre-employment, random, for cause/suspicion, post-accident, follow-up testing) compared to all other aviation safety-sensitive work groups.19

The following subsections synthesize and present information about FADAP operations made available to this study committee along with information from the FADAP website.

General Program Description

FADAP is a substance misuse prevention and assistance referral program available and accessible to all flight attendants regardless of their employment status (furloughed, active, on leave) and airline affiliation. The program provides referral to treatment and peer mentorship to flight attendants seeking or undergoing treatment and those in recovery from substance use disorders. Mentoring peers are fellow flight attendants, many having gone through treatment themselves, and they are trained by FADAP’s central office. FADAP also engages in primary prevention of substance misuse by making available educational materials, videos, and self-assessment screening tools, as well as by conducting educational seminars to key airline stakeholders on early identification and intervention for substance use disorders. The program is recognized as an approved educational provider by the Labor Assistance Professional Association, Employee Assistance Professional Association, National Association of Alcohol and Drug Counselors, and the Maryland Board of Social Work Examiners.

___________________

19 FADAP staff response to the committee-issued questionnaire, August 2022.

Established in September 2010,20 “FADAP was endorsed by flight attendant peers and managers from 25 carriers during a March 2009 ‘Return to the Cabin’ Summit” (FADAP, n.d.).

Program funding for FADAP is provided by the FAA. FAA contracts with the Association of Flight Attendants (AFA-CWA), a union representing about 50,000 flight attendants at 19 airlines, for administrative oversight of the program.21 The central FADAP staff comprises a manager, coordinator, and administrator, who are primarily responsible for program oversight, including the development and implementation of educational activities to increase substance misuse awareness among flight attendants and their families.22 The staff performs the following tasks:

- develops an outreach plan for educating and recruiting flight attendant volunteers as peers or workplace-based recovery mentors;

- develops educational materials and conducts educational seminars, peer training, annual conferences, and other, similar activities;

- maintains a FADAP database and website, used as the key informational resource for program awareness among flight attendants and their families;

- identifies and maintains a list of approved treatment providers based on input from various sectors, FADAP staff site visits and evaluations of staffing credentials, and facility accreditations (FADAP staff provides a minimum half-day training for facility staff on FADAP, flight attendant culture, occupational demands, stressors, and required communication and paperwork); and

- submits progress reports and meets with the advisory board, at least once a year.

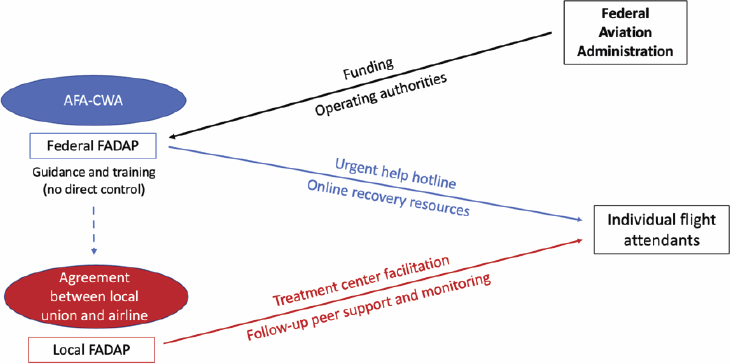

The FADAP Advisory Board monitors the program’s implementation, recommends changes in program operations as needed, and reviews program outcomes. It is composed of flight attendants, flight attendant managers, the FAA, and experts in the field of substance use disorders. The board approves the FADAP outreach plan, educational materials, and program activities.23 See Figure 2-3 for the FADAP governance operating model.

The other key FADAP component is to facilitate access to substance use treatment through peer support. Each FADAP is sponsored by an airline

___________________

20 The AFA-CWA did have an expanded EAP for flight attendants before FADAP (Feuer, 1987), but it is unclear what elements (if any) from the old system were maintained after the 2010 launch.

21 FADAP staff response to the committee-issued questionnaire, August 2022.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

SOURCE: Data from https://www.fadap.org/more-about-fadap and responses to the committee questionnaire to FADAP.

and its associated flight attendant union. While peer training is conducted by FADAP staff, the sponsoring airline or union has direct oversight of their own FADAP peer program. While there is no formal written agreement between the EAP and FADAP, they collaborate and, whenever possible, they comanage flight attendants referred for short-term substance use treatment.

Airlines are not mandated by the FAA to establish a FADAP peer program, nor are they obligated to support the cost of FADAP operations.24 However, airline management may choose to extend support however they deem appropriate, such as coordinating travel for peers to attend FADAP training, paying for expenses associated with attending the program’s seminars and conferences, allowing peers time off to attend its educational seminars, or offering FADAP training to flight attendant leaders and supervisors.

FADAP administrators believe its peer support system is a model for motivating flight attendants, particularly those who have no reported rule violation, to seek treatment without fear of disclosing their condition to their employer or the FAA.25 Confidentiality is observed both for the flight attendant seeking treatment as well as for the referring agent (e.g., flight attendant colleague, manager or supervisor, pilot). This allows voluntary removal from performing safety-sensitive duties while impaired

___________________

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

(in which case the flight crew may call FADAP to “save a peer”) or while undergoing treatment, and hence preserves the opportunity for flight attendants to keep their job and return safely to duty.

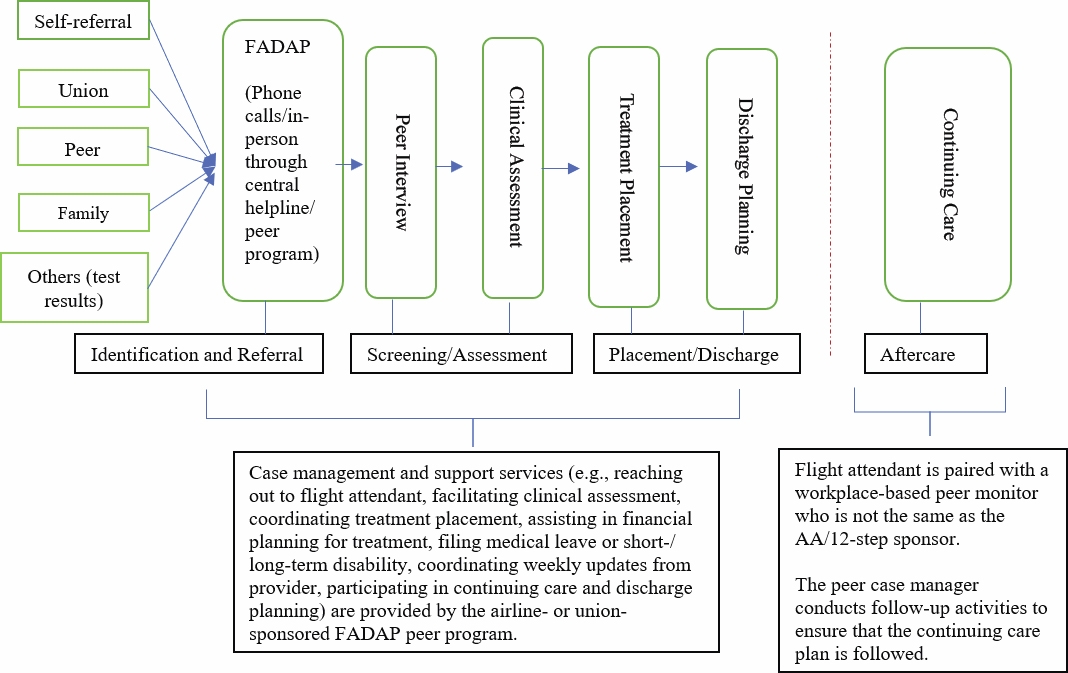

Figure 2-4 depicts the relationships among the various agencies and organizations involved in administering the FADAP.

Treatment Service Delivery Process

FADAP services are available and accessible to all flight attendants. They may either call the FADAP central helpline or contact, in person or by phone, the FADAP peer program at their airline. Twenty-four airlines have an established FADAP peer program. They vary in size, maturity, and visibility in the flight attendants’ work environment. Some are fully assimilated into labor and management communications, training programs, and partnership activities.

Peers are flight attendant volunteers who made a commitment to participate in the FADAP case management process. They are appointed by the peer program sponsor (i.e., the union or airline management). Peers undergo a one-day training given by FADAP staff on topics including:

- nature and models of addiction;

- successful interventions, which motivate the flight attendant to seek treatment;

SOURCE: Data from https://www.fadap.org/more-about-fadap and responses to the committee questionnaire to FADAP.

- types of substance use treatments, best treatment practices for flight attendants, the treatment continuum;

- safely moving the flight attendant into treatment;

- FADAP peer case manager checklist;

- re-occurrence (relapse) prevention;

- FADAP resources;

- what one needs to know to function as a peer; and

- peer self-care.

Incoming peers are “shadowed” by a more senior peer for several months and provided access to periodic virtual continuing education training, virtual FADAP treatment site-visits, and 2.5 days of education during the FADAP conference. A certification track for peers is also offered to advance their education and training.26

Identification and Referral

While there are no mandatory requirements for flight attendants to report substance use problems or substance-related convictions to the FAA or airline, there are several pathways for referring or identifying flight attendants to participate in FADAP (see Figure 2-5). Flight attendants may self-identify, or referrals may be received from colleagues, family members, flight attendant unions, EAPs, supervisors/managers, or others such as flight attendants involved in accident investigations, a failed drug test administered by the DOT, or disciplinary action due to substance misuse.

Screening and Assessment

When a flight attendant is referred to FADAP, the program conducts outreach through a peer, who later serves as the point of contact for the initiation of an intervention.27 The peer conducts the initial screening to determine whether the flight attendant is misusing a substance and to determine the extent, seriousness, and urgency of any work-related issue. The peer motivates the flight attendant to seek treatment, and when a flight attendant agrees to go, the flight attendant selects a treatment program from a list of FADAP-approved treatment providers for admission to care.

The treatment intake process generally includes evaluation for primary mental health diagnoses and personality disorders. According to the FADAP 2021 Annual Report,

___________________

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

SOURCE: Data from https://www.fadap.org/more-about-fadap and responses to the committee questionnaire to FADAP.

over the past two years, 37 percent of Flight Attendants were diagnosed with anxiety and related disorders, 45 percent with depressive disorders, 4 percent with bipolar and related disorders, and 8 percent with other mental health disorders or other disorders. Diagnosis is defined using the DSM-5 criteria.28

In response to a committee questionnaire received from FADAP staff, beginning in 2021 the Advisory Board approved the expansion of FADAP’s focus to include mental health messaging. As of June 2022, all FADAP peers had completed training in a course focused on mental health first aid in the workplace. While tobacco use is known to be widely prevalent among persons with mental health disorders and increases the risk of relapse to other substance use, it has not been formally included in the FADAP assessment process. However, FADAP staff reported that they had referred flight attendants for smoking cessation.

Treatment Placement and Cost

Many flight attendants have logistical complications to work out through treatment including, filing for leave of absence, determining the sources of funding to cover the cost of treatment (e.g., health insurance, disability programs, Medicaid, and family financial resources), and determining where to get treatment All logistical requirements advancing the flight attendant from the referral phase to actual placement at a treatment facility are primarily managed by the FADAP peer program.

A typical treatment episode includes a detox phase (as needed), psychiatric evaluation, medical evaluation, a 28–30-day residential treatment episode (which may include individual and group therapy, family treatment, substance abuse education, and trauma-specific interventions), with step-downs to a partial hospitalization program and/or intensive outpatient program, followed by an outpatient program as needed.29 FADAP supports the use of therapeutic medications that are nonaddictive.30 The use of medication-assisted treatment is also supported by FADAP for detoxification but not as maintenance medications. FADAP supports an abstinence model for flight attendants returning to safety-sensitive duties.

According to FADAP staff, based on a random survey they conducted among peer programs at various airlines, the ratio of residential treatment placements to nonresidential and peer support is 1:3.31 That means, for

___________________

28 FADAP’s 2021 Annual Report was provided by FADAP to the committee for review but is not available for the public.

29 FADAP staff response to the committee-issued questionnaire, August 2022.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid.

every one flight attendant placed in a FADAP-approved residential treatment program, three flight attendants received some other form of peer assistance, engaged in mutual help groups (MHGs) and/or clinical intervention initiated at any of these levels of care: partial hospital outpatient program, intensive outpatient program (IOP), or standard outpatient care.

FADAP does not pay for any treatment services. The level of care provided to a flight attendant is typically limited to what is authorized by the flight attendant’s health insurance, or to the extent of what the flight attendant’s personal financial resources can cover. For those without insurance, FADAP will refer the flight attendant into sliding-fee-scale programs or assist in applying for Medicaid. Two notable exceptions, however, were cited by the FADAP staff. One airline covers 100 percent of the treatment cost, including deductibles and out-of-pocket costs, for flight attendants placed in a 30-day residential treatment in a FADAP-approved treatment facility. At another airline, an automatic authorization for 28–30 residential days is provided to flight attendants placed by FADAP peers into health insurance-covered and FADAP-approved residential treatment programs.

Per FADAP staff estimates, the allowable rate per day ranges from $600 to $900 in a residential facility, $450 to $650 in a partial hospital outpatient program, and $250 to $350 in an IOP. The staff cited in their response to the committee’s FADAP questionnaire that between 2019 and 2021, 445 flight attendants were placed in residential treatment programs. The length of stay in these treatment programs and/or some combination with a Physician Health Program was as follows: 230 flight attendants had an average stay of 28 to 39 days; 158 spent 40 to 60 days; 46 spent 60-plus days; and 11 were discharged before treatment completion.

Progress in the flight attendant’s treatment is reported, with a release of information in place, by the treatment provider on a weekly basis to the assigned FADAP peer case manager and to the FADAP staff. The information is kept confidential from external agencies such as the FAA and from the employer (airline), unless a release of information is signed by the flight attendant.

The FADAP peer case manager performs other support activities while the flight attendant is in treatment. This includes contacting and scheduling family member participation in a family treatment program, coordinating and participating in the flight attendant’s continuing care and discharge planning, and selecting mentors from a list provided by the FADAP staff to be paired with flight attendants as they transition out of primary treatment.

A mentor is a flight attendant who self-identifies as a person in recovery from a substance use disorder has at least two years of “solid recovery,” as defined by local FADAP leadership, has returned to duty, and volunteers to offer support to flight attendants coming out of treatment. A mentor’s primary role is to lend a listening ear and help the flight attendant successfully

navigate recovery in the first year. Unlike peers, mentors are not given formal training to be a part of the recovery process. A mentor is not the same as the sponsor for a 12-step support program.

Continuing Care Services and Recovery Support

After discharge from treatment, the assigned volunteer peer case manager conducts a series of follow-up activities on a periodic basis—within 24 hours of discharge, weekly for the first 12 weeks after discharge, every two weeks for months 3 to 6, and monthly from months 6 to 12.32 The purpose of these follow-up contacts is to ensure that the continuing care plan provided at discharge is being followed to maintain the flight attendant’s wellness in the first year of recovery.

The recovery support services include, among others:

- 12-step support, such as through Wings of Sobriety;

- flight attendant family education classes and educational materials;

- resource materials on flying and medication (available on the FADAP website);

- wearing FADAP recovery pins; and

- mentorship program for flight attendant in recovery.

Employee Return-to-Duty Procedure

Determining the fitness for duty of nonmedically certified transportation safety-sensitive employees usually follows a process spelled out in collective bargaining agreements between the company and the union. Since flight attendants are not required to be medically certified, there are no FAA required tests or evaluations. A provider’s release note is all that is required.

If the flight attendant was referred to FADAP due to a positive DOT test result, the DOT return-to-duty process is followed, depending on the airline regulation. The process includes a substance-use evaluation by a qualified SAP, completion of that professional’s recommended education or treatment, clearance by the SAP to return to flight attendant duties, and a negative result on a return-to-duty drug/alcohol test. FADAP helps the flight attendant complete this process, regardless of whether the airline regulation allows for conditional reinstatement (vs. termination).

___________________

32 Ibid.

Program Monitoring and Outcomes Measurement

The overall program performance is monitored by the FAA contractor, AFA-CWA.33 AFA-CWA does not monitor individual cases or engage in flight attendant testing on a routine basis. The airline or union that sponsors the FADAP peer program has oversight responsibility only for the support and follow-up activities that they provide to facilitate treatment placement and recovery.

The FADAP tracking database was developed to quantify the effectiveness of the FADAP across airlines, and to identify possible risk factors, treatment failures, and areas for potential improvement. The database captures data only concerning flight attendants placed in a FADAP-approved residential treatment program. Flight attendants referred to intensive outpatient programs, individual therapy, or MHGs who may have received peer assistance are not reported in the database. The tracked data are analyzed and reported to the FADAP Advisory Board and are presented to the airlines, unions, and flight attendant leaders while maintaining the confidentiality and privacy of the FADAP participants. Access to the database for other research purposes is handled on a case-by-case basis.

In addition to the administrative and clinical data maintained in the database, a follow-up survey is conducted that includes satisfaction questions on the FADAP peer program and the treatment facility (recently added). Surveys are mailed or emailed to flight attendants one year after the initial treatment episode. In 2020, a new survey was introduced with a shorter timeframe (after three to four weeks post treatment). This new survey includes survey items to capture intermediary outcome measures.34

The FADAP monitors both process and outcome measures. Some examples follow:

- Process measures:

- primary treatment diagnosis for drug, alcohol, and mental health (using DSM-5-TR);

- level of satisfaction with FADAP peer program, using Likert scale questionnaire;

- level of satisfaction with treatment provider, using Likert scale questionnaire;

- treatment engagement, using Likert scale questionnaire (rated by both the treatment provider and the flight attendant); and

- number of treatment episodes for the flight attendant.

___________________

33 Ibid.

34 “Workplace Outcomes Related to Participation” in the FADAP 2021 Annual Report.

-

Workplace outcomes:

- work engagement;

- presenteeism;

- lost work time;

- workplace behavior such as flight attendant’s reported improvement in attendance, drinking past cut-off time, showing up for a flight hung-over, not showing up for a trip due to substance use, and self-perspective on overall work performance; and

- return on investment measured by the flight attendant’s reported (a) adherence to safety procedures and compliance with FAA and company policies; (b) rapport with management, coworkers, and customers; and (c) professionalism, presenteeism, and reliability.

FADAP Summary

While in-depth analysis is covered in Chapter Five, some general observations can be made about FADAP’s model for treatment referral and recovery support as it offers a framework in which unpaid peers play an essential role in the flight attendant’s decision to seek treatment, be engaged in treatment, and have a successful journey to recovery for a safe return to duty. However, a more proactive effort in secondary and tertiary prevention through early identification and intervention, rather than waiting until the flight attendant is “ready,” may encourage more flight attendants to seek support and treatment earlier. Additionally, FADAP can improve its process by adopting a more individualized approach to treatment and recovery; level of care and length of stay should be individualized to the flight attendant’s unique circumstances based on thorough assessment using the American Society of Addiction Medicine dimensions. Most importantly, consideration to address the likely program challenges discussed below may strengthen the program.

Limited Funding Sources for Treatment

Flight attendants can still incur significant costs regardless of level of care. Additionally, the decision of a flight attendant to enter treatment goes beyond the actual expenses incurred in treatment. Their absence from work while in treatment leads to loss in income for many flight attendants. Furthermore, the type and length of treatment depend heavily on what services are covered by the flight attendant’s health insurance, which in turn differs from airline to airline. Expenses associated with treatment may impact a flight attendant’s decision to pursue or delay treatment.

Heavy Reliance on Peer Volunteers

Heavy reliance on volunteers to support the FADAP peer model could result in a less efficient program if there is a decline in the number of volunteers, both for trained peers and mentors. This could disrupt the program’s ability to maintain effective operations. It may be essential for FADAP to have a program continuity plan by incentivizing enrollment of peers and mentors rather than relying on volunteers. FADAP may also consider establishing the efficacy of its peer-support model in collaboration with ongoing support from professionals in the field and by examining the evidence base to further explore how benefits could be maximized from a peer intervention or support model.

Data Collection and Data Analysis

Using data from flight attendants’ FADAP intake and follow-up forms, the FADAP central office maintains a database. This database is used to track program-level outcomes for flight attendants who engage in residential treatment. De-identified data from this database were provided to the study committee, which found numerous issues with the data. The population covered in the FADAP database is limited only to flight attendants who received treatment from FADAP-approved residential treatment programs, and there is a high degree of missingness. Therefore, the database does not capture all of FADAP peer interactions with flight attendants. Flight attendants who received services through nonresidential treatment and peer support (e.g., intensive outpatient, outpatient, individual therapy, MHGs) are currently not reported. Also, only 19 of the 24 peer programs at individual airlines report data to the FADAP database. On this basis, it is difficult to ascertain the prevalence of flight attendants engaging in substance misuse, those needing substance use treatment, and the corresponding treated population.

In addition, FADAP conducted follow-up surveys 12 months after initial treatment. This timeframe potentially presents recall bias, and it shows a high degree of loss to follow-up. Because there are few paired pre-post surveys in the dataset, arguments on program effectiveness and outcomes based on these data may be unreliable. A more meaningful data collection protocol and robust analysis of the data are needed to develop stronger arguments for program improvement and decision support.

This page intentionally left blank.