Substance Misuse Programs in Commercial Aviation: Safety First (2023)

Chapter: 3 Evidence-Based Practices for Identifying and Treating Substance Use Disorders

3

Evidence-Based Practices for Identifying and Treating Substance Use Disorders

With a wealth of new research, a robust evidence base has emerged over the past few decades that can now be applied to better support people with substance use disorders. This chapter presents the state of current knowledge about the use of substances and progression to severe substance use disorders for the general population, highlighting the shift in thinking in which professionals have adopted a disease model of addiction and increasingly apply prevention frameworks to substance use disorders. The chapter also points to key elements of screening, assessment, and treatment of substance use disorders, including medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and ongoing health monitoring. Lastly, given the lack of high-quality studies of treatment outcomes specifically among professionals in safety-sensitive industries, the chapter summarizes evidence-supported practices for treatment with special attention to applying the indirect, but still valuable, research findings for professionals in safety-sensitive occupations, including pilots and flight attendants.

OVERVIEW OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Substance use is common in the United States across all demographic groups. Most people typically first experiment with substances that have addiction potential prior to the age of 18 (Schramm-Sapyta et al., 2009). The heaviest use of these substances often occurs between adolescence and young adulthood and generally decreases following young adulthood. Most individuals who experiment with substances do not develop a substance use disorder, and the majority of those who do develop a disorder experience

mild to moderate disorders. Those at highest risk of developing a substance use disorder have “earlier onset of use, history of traumatic events, family history of substance use, and/or mental health problems” (McLellan et al., 2022). Once the problem has progressed to a severe substance use disorder—the point at which substance use becomes a chronic, relapsing condition—it is often referred to as addiction.

Notably, alcohol is the most used and misused substance in the United States and across much of the world (Sudhinaraset et al., 2016; Substance Abuse Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2023). The data are clear that use at a younger age and a pattern of binge drinking are associated with increased risk of developing an alcohol use disorder (Hingson et al., 2006; Sudhinaraset et al., 2016; Substance Abuse Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2023). The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) has developed research-based guidelines (see Figure 3-1 and Table 3-1) to help identify high-risk drinking patterns in adults that may lead to substance-use disorders. Alcohol usage becomes high-risk when men consume more than four drinks on any day or more than 14 drinks per week, while for women the prescribed limits are no more than three drinks on any day or more than seven drinks per week (NIAAA, 2020).1

However, newer research completed by the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that no safe amount of alcohol consumption exists, and that while NIAAA guidelines provide insight for those with high-risk drinking patterns that may progress to a disorder, they do not accurately reflect the health risk of even relatively low levels of alcohol consumption for the general public (Manthey & Rehm, 2022; World Health Organization, 2023).

People with substance use problems underreport their use and generally lack insight into the severity of their disease (Bone et al., 2016; Delaney-Black et al., 2010). These traits are exacerbated when a person is entering treatment in response to a problem at work, at the requirement of their employer, or at the requirement of a professional monitoring organization (Vayr et al., 2019; Wooley et al., 2013). By the time a substance use problem presents within a work setting, the disease has typically progressed to a severe level. Professional identity can be paramount for safety-sensitive professionals, and they work hard to maintain their reputation for competence and control (DeHoff & Cusick, 2018), generally while masking even acceptable forms of struggle within our culture (e.g., raising children, work stressors, divorce). Commonly, professionals in these situations engage in positive impression management, attempting to control how they are perceived, highlighting their strengths, and downplaying any problems (Brown

___________________

1 After a prepublication version of the report was released, generalized key messages from a table were converted to text to mitigate any potential copyright concerns.

SOURCE: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, n.d.

TABLE 3-1 Heavy Alcohol Use for Men and Womena

| MEN | WOMEN | |

|---|---|---|

| Drink on a single day | 5 or more | 4 or more |

| AND | AND | |

| Drinks per week | 15 or more | 8 or more |

NOTE: aAfter a prepublication version of the report was released, this table was changed to reflect the source information more accurately.

SOURCE: Data from NIAAA (https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking)

et al., 2015; Picard et al., 2023). Individuals with severe substance use disorders seek opportunities to use substances; professionals with substance use disorders may obtain positions or shifts that allow them to hide their disease (e.g., working overnight shifts, flying with smaller airlines with less oversight, turning down social time to hide their drinking).

As noted in Chapter 1, literature discussing substance use disorders among pilots and flight attendants suggests that they may experience rates of illness like those in the general population, though there is little validated data to directly support this. (Porges, 2013). However, of the more than 41 million adults in need of substance use disorder treatment, just under two percent received any type of treatment within the past year (SAMHSA, 2022). Most individuals (~97%) with a substance use disorder believe they do not need treatment, a small percentage (~2%) believe they need treatment but did not seek treatment in the past year, and only a fraction (~1%) made an effort to receive treatment (SAMHSA, 2022a).

Engaging in treatment for substance use disorders is associated with significant reductions in substance use, along with improvement in overall health and quality of life (Lail & Fairbairn, 2018; McLellan et al., 2000). However, the effectiveness of these approaches is substantially hampered by poor adherence. Though effectiveness varies significantly by treatment type, it is generally estimated that less than half of those who initiate substance use disorder treatment will still be abstinent a year later (Gaudiano et al., 2011; Milward et al., 2014; Moos et al., 1999; Sliedrecht et al., 2019). Even in physician health programs, with physicians representing a safety-sensitive group, relapse rates over five years can be 22 percent (Dupont & Merlo, 2018).

The literature has revealed several variables associated with retention in treatment and therapeutic success. These include patient characteristics such as engagement in the treatment process (e.g., compliance with medication, adherence to appointments), sociodemographic variables (e.g., age), clinical history (e.g., substance use disorder severity and concomitant psychiatric diagnosis), psychosocial characteristics (e.g., motivation), and neuropsychological variables (e.g., inhibitory control).

Following the identification of the substance use disorder and referral to treatment, people in safety-sensitive populations, which includes those working in construction, transportation, and healthcare, are removed from their positions and are unable to return to work until they complete all return-to-work requirements. These requirements often include completion of treatment, substance use abstinence, and a fitness-for-duty assessment. Rates of alcohol and other substance misuse among pilots and flight attendants have been shown to be potentially comparable to the rates among other skilled professionals and safety-sensitive populations (Atherton, 2019; Horton et al., 2011). There is also evidence that the

occurrence of substance use among pilots involved in civil aviation accidents is similar to that found in the non-flying public (Botch & Johnson, 2009). Furthermore, findings from the National Transportation Safety Board (2020) suggest that misuse of licit and illicit substances among pilots is increasing.

Early detection and intervention have been shown to be important factors in the successful management of substance use disorders, reducing symptom severity and facilitating a more rapid return to full functioning. Thus, screening for substance use and mental health problems is recommended by various major health organizations (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2018; White, 2012). Though data on treatment retention and success are lacking, specifically among safety-sensitive professionals, there are data to suggest that workplace-supported recovery is associated with positive outcomes regarding both drug use and employment (DeFulio et al., 2009; Frone et al., 2022). Therefore, when correctly implemented, programs such as the Human Intervention Motivational Study and Flight Attendant Drug and Alcohol Program (FADAP) have the potential to successfully manage substance use disorders and ensure a return to work among their respective safety-sensitive populations.

Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorders

Prior to the adoption of scientific, medical models of addiction, people with substance use disorders were viewed as lacking moral character, and the condition of addiction was viewed as a choice. As a result, the response to people with substance use disorders was punitive. More current models of addiction view it as a brain disease. Health care professionals determine whether someone meets criteria for a substance use disorder using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the authoritative guide for diagnosing mental disorders (see Box 3-1 for the more recently adopted disease model of addiction).

The current version of the diagnostic manual, the DSM-5,2 revised the DSM-IV by eliminating the diagnostic categories of “substance abuse” and “substance dependence.” Not only is the term “substance abuse” stigmatizing, but the DSM-IV abuse criteria lacked reliability and validity (Hasin et al., 2013). The DSM-IV term “substance dependence” created confusion with certain prescribed medications that were beneficial but were nonetheless associated with physiological dependence symptoms, such as withdrawal symptoms upon abrupt discontinuation.

___________________

2 For report consistency and readability, the committee is using “DSM-5” instead of “DSM-5 (text revision),” but readers should update their best practices as new additions of DSM are released.

The criteria for substance use disorder cited in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2022) include 11 symptoms that broadly describe four pathological patterns of substance use (rephrased below):

- Impaired control over substance use, including:3

- Using the substance more, or longer, than intended

___________________

3 After a prepublication version of the report was released, information from a figure was integrated into the following text due to copyright considerations.

-

- More than a single instance of unsuccessfully attempting to reduce or stop using the substance

- Experiencing strong cravings to use a substance that disrupt the ability to think about other things

- Impairment in social functioning, including:

- Excessive time using or being sick from the substance or its after effects

- Interference in executing home, family, school, or professional responsibilities due to substance use

- Continued substance use despite negative impacts to personal relationships

- Reducing or withdrawing from activities of interest due to substance use

- Recurrent substance use which puts the person using the substance at risk for physical and psychological harm, including:

- Getting into dangerous situations due to substance use

- Continued substance use despite deleterious mental health outcomes

- Pharmacological criteria of tolerance and withdrawal, including:

- Having to use more of the substance to achieve desired effects

- Feeling negative physical and mental symptoms related to withdrawal

In formalizing a diagnosis, the number of symptoms determines the severity of the disease (e.g., 2 or 3 symptoms = mild; 4 or 5 symptoms = moderate; 6+ symptoms = severe). Notably, neither the quantity of substance used nor blood alcohol levels are features of the diagnostic criteria. For example, the amount of alcohol consumed on an average day or the blood alcohol content (BAC) at a given time (e.g., DUI) are not factors in determining whether a person has a substance use disorder.

The diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders apply to all substances with addictive potential. However, the diagnoses are differentiated by substance in regard to symptoms of intoxication and withdrawal. For example, withdrawal from alcohol and stimulants, such as cocaine, may result in sleep difficulties and agitation; however, withdrawal from alcohol can also result in vomiting, hallucinations, and seizures, whereas withdrawal from stimulants can result in a dysphoric mood, fatigue, and increased appetite. The terms “addiction” and “alcoholism” are regularly used by people with substance use disorders; however, DSM-5 does not use these terms because of their “uncertain definition and potentially negative connotation” (APA, 2022) The DSM-5 does recognize that some clinicians will use the term “addiction” to refer to severe substance use disorders.

While diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders as defined by the DSM-5 apply to all people, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) uses different definitions to determine when a pilot has a problem. For example, as reviewed in Chapter 2 of this report, the blood alcohol concentration limit for pilots reporting to duty is 0.04. This lower threshold than the 0.08 for the average American car driver is to protect the public from harm as research has shown impairment occurring at even lower levels of blood alcohol concentration (Mumenthaler et al., 2003; NHTSA, 2000). Further, while this is not written into policy, it is widely accepted by aviation medical examiners (AMEs) and encouraged at the Human Intervention Motivational Study (HIMS) conference to consider a blood alcohol content at time of DUI or reporting to duty of 0.15–0.199 as an indication of reaching the FAA definition of abuse and a blood alcohol content of 0.2 or higher as the FAA definition of dependence. This stricter threshold is to protect the public and impairment has been demonstrated to affect drivers having lower levels of blood alcohol concentration (NHTSA, 2000). Pilots and flight attendants employed by larger airlines are more likely to have treatment costs covered regardless of received diagnoses. However, pilots at smaller and mid-sized airlines could meet the FAA definition of substance abuse or dependence but not qualify for insurance coverage, as they would not have a diagnosis based on the clinical DSM-5 criteria for a substance use disorder.

Benefits of Prevention and Early Intervention

The costs of not addressing substance misuse and substance use disorders can go beyond the individual consequences, with substance misuse across this continuum resulting in costs to society at large of more than $400 billion annually (Murthy, 2017). Substance misuse increases company healthcare costs, missed work days, injuries on the job, and rates of employee turnover, while it decreases productivity. Too commonly, intervention efforts in the workplace focus on the most severe cases of substance use disorders, but the consequences of mild to moderate substance use disorders (i.e., two to five DSM-5 symptoms) account for more societal substance-related harms than severe substance use disorders (i.e., six or more DSM-5 symptoms; McClellan et al., 2022). Unfortunately, substance use and work are intimately intertwined, regardless of whether use occurs at work. The concept of pre-addiction, defined as mild to moderate substance use disorders, has been proposed as a crucial point for intervention that is analogous to the care model of diabetes in which prediabetes is a crucial point for intervention (McClellan et al., 2022). Investment in identifying at-risk employees and treatment could result in savings for both the company and society in general by stopping the progression of the disorder. In fact,

it is estimated that every dollar spent on substance use disorder treatment saves four dollars in healthcare costs (Murthy, 2016). Professionals with substance use disorders in safety-sensitive occupations pose a greater risk to others and cost to society because of the nature of their work; as a result, the workplace can be an ideal point for intervention.

DISEASE PREVENTION

Recognizing that addiction is a disease and not a moral failing, focus and investment can be made to strategically optimize outcomes and have the most impact. A disease prevention model highlights the different components to address the disease, including health promotion, prevention, treatment, and recovery (see Figure 3-2). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines prevention as being “delivered prior to the onset of a disorder. These interventions are intended to prevent or reduce the risk of developing a behavioral health problem.”

Integrating Approaches to Improve Care

Traditionally, services for preventing and treating substance use disorders have been delivered separately from other mental health and general healthcare services. However, it is increasingly recommended that assessment and treatment for substance misuse be integrated with other health care delivery (Murthy, 2016). This approach is a model of integrated behavioral healthcare that brings together primary care and behavioral health clinicians, such as clinical psychologists and clinical social workers,

SOURCE: Adapted from Haggerty & Mrazek, 1994.

to provide a team based, evidence-based approach to patient-centered care. One more integrated approach to addressing substance use is called, Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT). SBIRT is an evidence-based practice to identify, reduce, and prevent misuse of alcohol and tobacco in primary care settings; however, its strongest evidence is within the context of alcohol use (Barata et al., 2017; Mello et al., 2018). The approach is also gaining traction in the workplace, with EAPs offering a set number of free therapy sessions and wellness initiatives (McPherson et al., 2010; Taranowski & Mahieu, 2013).

The SBIRT model adapted to the workplace consists of three primary components: (1) screening employees for risky substance use behaviors using standardized screening tools; (2) a brief intervention by motivating employees to make a specific change; and (3) referral to treatment to brief therapy or additional treatment services.4

BEST PRACTICES IN SCREENING, ASSESSING, AND TREATING SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

While SBIRT is often used in primary care and emergency medicine settings, the spectrum of screening, assessment, treatment, and ongoing monitoring for substance use disorders can cross multiple environments (SAMHSA, 2022b). Evidence examining the use of SBIRT in the occupational setting is not strong, but it has still proven to be a valuable tool in general. This section highlights evidence-supported practices across that continuum, with special considerations that could be applied for safety-sensitive professionals where appropriate.

Screening

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that primary care providers screen for anxiety, depression, alcohol use, and tobacco use in adults and offer brief behavioral interventions as indicated. Many people with substance use disorders do not seek treatment on their own due to a variety of reasons, including not believing that they need treatment, not being ready to engage in treatment, being unaware of treatment options, not knowing how to access treatment that is available, the political climate, perceived stigma of what it means to need treatment, and other social and structural barriers that are themselves linked to risks for substance use, like the cost of care, low employment status, low household income, and inadequate (or lack of housing; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2018).

___________________

4 For a practical example, see https://vitalalabama.com/professional-resources/sbirt-tool-kit/

People often access the healthcare system for other reasons, however, including annual physicals or other preventative care appointments, acute health problems like illness, injury, or overdose, as well as chronic health conditions such as HIV/AIDS, heart disease, diabetes, anxiety, or depression. If people access care of any kind, they most commonly reach out to a primary care provider, so screening related to substance use as part of these more general health assessments is a crucial point of prevention and intervention. If a person screens positive on measures delivered as part of these visits, follow-up assessment is indicated. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that individuals with problematic levels of alcohol use be offered patient-centered advice about recommended limits and information on how alcohol use relates to other health conditions.

Disorders characterized by symptoms of anxiety and depression and in response to trauma often lead people to use substances to obtain some relief. Thus, screening for mental health conditions that often co-occur with substance use disorders is also particularly important. Addressing these concerns can be preventative of problematic substance use and progression from use to a severe substance use disorder. The National Institute on Drug Abuse offers several evidence-based screening and assessment tools for varying types of substance use (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], n.d.).

For pilots, the FAA requires a medical examination with a specialized AME every six months to five years, depending on their age and the type of flying they do. Part of this evaluation includes a review of diagnoses related to psychosis, bipolar disorder, severe personality disorders, and substance misuse and dependence; however, the review process varies by AME. While most public and private health programs require providers to screen for alcohol and depression, HIMS’s reported 0.5 percent positive screening referral rate suggests possible inadequate attention to such screening (Snyder, 2021). Incorporation of substance use, mental health, and stress screeners could be integrated during these assessments to standardize the evaluation process and integrate a prevention strategy.

Safety-sensitive professionals are acutely aware of the consequences that a mental health or substance-related concern can have on their career. As a result, they may minimize these issues and often do not establish care with a primary care provider, avoiding regular screenings (DeHoff & Cusick, 2018). The lack of discussion around substance use can encourage silence and facilitate shame, stigma, and suffering in isolation. Screening specific to assessing when substance use started, whether the professional has a history of traumatic events or a family history of substance misuse, and any mental health problems can help identify safety-sensitive professionals at high risk of developing a substance use disorder. If employee screening does not adequately identify safety-sensitive professionals at risk

of developing a substance use disorder, the benefit of professional substance use programs is fundamentally weak.

Based on that screening, which includes assessment for co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders, a determination is made about what support the client may need. Brief intervention includes five steps: (1) asking permission to discuss the screening results; (2) reviewing the screening results or substance use patterns and providing feedback; (3) exploring how the presenting problem may be related to substance use and how the employee views the identified problem; (4) assessing and negotiating readiness to change and developing a plan with the employee to achieve goals; and (5) discussing next steps, which could include brief treatment. Finally, clients who require treatment beyond the brief intervention could then be referred to options within the structure of their respective program.5

Evidence examining the use of SBIRT in the occupational setting is not strong, but it has still proven to be a valuable tool in general.

Assessment of Substance Use Disorders

Assessment is a crucial step for determining the severity of a person’s substance misuse problem, identifying whether they have a substance use disorder and any co-occurring conditions, and making recommendations to address their unique needs for healing. This process allows all constituents to gain an understanding of the current situation and the most appropriate course of action. With proper releases of information (ROIs), the individual being assessed, their identified family, their employer and/or professional support program, and treatment providers can be included in this process, both for obtaining collateral information and for executing the recommendations.

It is best practice for treatment providers, whether at formal treatment centers or an individual provider, to do a thorough assessment of an individual seeking care. This process can vary significantly depending on the point of entry to care, whether from a provider in private practice, in a formal treatment facility intake, or in a more multidisciplinary assessment during residential treatment. The best assessments include collateral information (APA, 2020) to gather data beyond what is provided by the person seeking care and screen for common co-occurring disorders and factors that put someone at higher risk for developing a substance use disorder (e.g., onset of use, family history of substance use, trauma history, anxiety, depression, process addictions, physical complaints [APA, 2020]. People with substance use problems tend to underreport their use and generally can lack insight into the severity of their own disease (Halpern et al., 2019; Steinhoff et al., 2023). These issues can be amplified when entering

___________________

5 Ibid.

treatment at the requirement of an employer or a professional monitoring organization due to attempts at positive impression management (Brown et al., 2015; Picard et al., 2023).

Available Models for Assessment

Two theoretical frames guide the best substance use disorder assessments: The Biopsychosocial-Spiritual Approach and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) Criteria; both of which focus on a multidimensional approach and encourage clinically driven treatment and recommendations. The biopsychosocial model, first introduced by Engel (1977) and later expanded to include spirituality (McKee & Chappel, 1992), challenged the traditional biomedical approach to treating disease to include a more holistic approach. This model recognizes that “the biological, psychological, social, and spiritual are distinct dimensions of the person, and no one aspect can be disaggregated from the whole” (Sulmasy, 2002). Spirituality, as defined by Puchalski et al. (2009), “is the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose, and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.” The Alcoholics Anonymous Big Book further supports this dimension; it describes alcohol use disorders and resentments that often accompany them as being a spiritual disease, “for we have been not only mentally and physically ill, we have been spiritually sick” (Alcoholics Anonymous, 2002) Thus, for a person to transition into a life of sustained recovery, it is important to assess each domain of the human experience to determine the unique interactions for the individual, to understand their presenting concerns and needs.

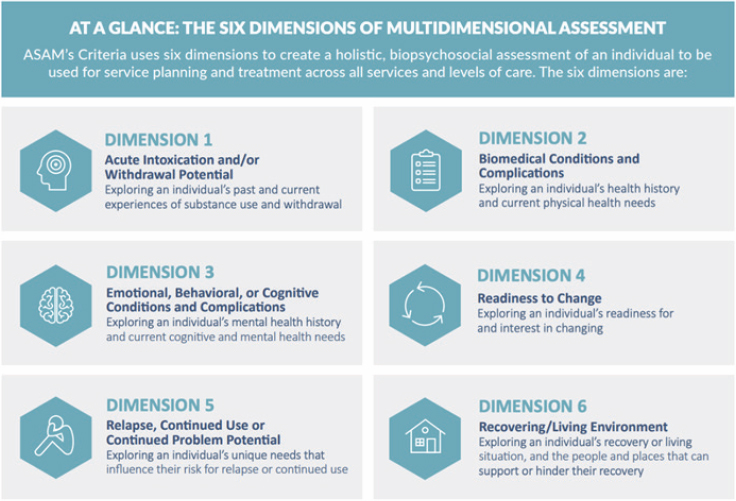

The ASAM model integrates the biopsychosocial-spiritual approach into six dimensions indicated for assessing the needs of people with substance use disorders (see Figure 3-3). Through an ASAM assessment, providers gather data about each of the six dimensions with the goal of determining the necessary level of care for each dimension, looking at both areas of strength and areas of concern. Providers with expertise in substance use disorders have specialized training, credentials, and insight into the presentation of these conditions and the needs of an individual for obtaining and sustaining recovery. Ultimately, a recommendation for level of care is made based on the data within each dimension and by considering the interaction across dimensions, along a continuum of care (see Figures 3-3 and 3-4).

Some assessments may be done before an individual seeks treatment. For example, when safety-sensitive transportation professionals violate a U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) drug and alcohol program regulation, they are required to be evaluated by a Substance Abuse Professional (SAP). SAP credentials were developed by the DOT to assist the agency in

supporting those of its employees who were identified as having a problem with drugs or alcohol (DOT, n.d.). This credential is distinct from those mentioned above. Pilots are required to have a medical clearance to perform their job. When pilots are diagnosed with substance abuse or dependence per the FAA definitions, they lose their medical certificate to fly. To return to the cockpit, they must undergo a fitness-for-duty assessment, described below. ASAM proposes that professionals in safety-sensitive professions have four unique qualities that lead to “important and distinct” needs for assessment and treatment (see Box 3-2).

In light of these unique qualities, ASAM recommends that professionals in safety-sensitive occupations discontinue work throughout the assessment period. The association further recommends that these professionals cease practice until risks to the public have been managed, all work regulations, licensure, and legal issues have been addressed, cues and triggers specific to the work environment have been identified, and a plan is in place to manage them. Further, ASAM recommends that the work environment and supervisory personnel be considerate of what it takes to sustain recovery. To be appropriate for a return to work, abstinence needs to be attained and a strong foundation of recovery established. These unique considerations add context to the assessment of these professionals. Moreover, employer policies may result in their not having income or insurance throughout this process; this added stressor often complicates the assessment.

Fitness for Duty Assessment

Most people with substance use disorders continue to work, and data suggest that work may have therapeutic effects on recovery outcomes (Frone et al., 2022; SAMHSA, 2019b; Walton & Hall, 2016). People in some safety-sensitive occupations, including pilots, will be relieved from their professional responsibilities until they complete an assessment and initial treatment and until risks to the public have been managed. As such, another unique consideration of assessing safety-sensitive professionals is the determination of fitness for duty, that is, whether and when a professional should be considered safe to return to their safety-sensitive responsibilities. While it has not been clearly defined when it is best to perform a fitness-for-duty evaluation, these evaluations would be most useful after three months of confirmed abstinence (NIDA, 2014).

In the transportation industry, many employees in safety-sensitive positions undergo fitness-for-duty assessments; pilots have more rigorous standards than most as this is required to obtain their special issuance medical certificate. The FAA defines pilot fitness for duty as “being physiologically and mentally prepared and capable of performing assigned duties at the highest degree of safety” (FAA, 2012). These assessments include psychological testing completed by a board-certified neuropsychologist and are conducted by an AME. The incorporation of psychological testing, particularly cognitive testing, provides an objective measure of functioning and impairment. If cognitive abilities have not been significantly impacted by a pilot’s substance use, the pilot can be cleared to return to work after having attained sobriety, having addressed any co-occurring mental health concerns, and having demonstrated a program of recovery from illness. If cognitive impairment is present, the process for returning to work is more complicated. It may be determined that some pilots will never regain

cognitive capacities to return to the cockpit; however, for others, a longer period of sustained recovery and repeat cognitive testing will be necessary to make a determination.

Treatment of Substance Use Disorders Across a Continuum of Care

The appropriate level of care for treatment and length of stay for someone with a substance use disorder is based on that individual’s present clinical presentation, as understood through the biopsychosocial-spiritual model and ASAM dimensions described previously. The landscape of addiction treatment is a continuum of care ranging from Early Intervention Services (Level 0.5) to Medically Managed Intensive Inpatient Services (Level 5; see Table 3-2 below from ASAM). A person with a substance use disorder can transition between levels of care within this continuum as needed, based on the progression of their disease. Any level of care on this continuum can serve as an individual’s entry point into addiction treatment, and what levels of care are available will be determined by where the person lives and their insurance plan and financial resources.

As improvement in the disease continues, the individual ideally steps down through the various levels of care; if an individual relapses or needs more support to avoid a relapse, they can step up in levels of care. Obtaining sobriety is the first step in healing. It is possible to change default neural networks, but this takes sober time, repetition, and accountability. Engaging in long-term treatment that adapts to the individual needs of each patient facilitates this healing process.

Understanding Entry into Treatment

People who need treatment for substance use disorders rarely enter treatment on their own (NIDA, 2007); but fortunately, how an individual enters treatment (e.g., voluntarily versus being mandated) does not predict whether the treatment will be beneficial (Coviello et al., 2013). People may seek treatment due to physical health problems, legal involvement, or a requirement placed on them by work or family. Members of more marginalized communities, such as African American and Latino people (Pinedo, 2019), have been found to be less likely to seek and use treatment for substance use disorders (Acevedo et al., 2018). These race-related barriers are likely due to a variety of reasons, including lack of timely access to services (Acevedo et al., 2018). For the general population, care should occur within the least restrictive environment that can appropriately address the individual’s treatment needs while keeping them safe. The duration of treatment, or length of stay, should be determined by a person’s progress toward their clinical treatment goals, including whether they desire

TABLE 3-2 Levels of Addiction Treatment

| Level of Care | Title | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | Early Intervention | Assessment and education for at-risk individuals who do not meet diagnostic criteria for substance use disorder |

| 1 | Outpatient Services | Less than 9 hours of service/week for recovery or motivational enhancement therapies/strategies |

| 2.1 | Intensive Outpatient Services | 9 or more hours of service/week to treat multidimensional instability |

| 2.5 | Partial Hospitalization Services | 20 or more hours of service/week for multidimensional instability not requiring 24-hour care |

| 3.1 | Clinically Managed Low-Intensity Residential Services | 24-hour structure with available trained personnel; at least 5 hours of clinical service/week |

| 3.3 | Clinically Managed Population-Specific High-Intensity Residential Services | 24-hour care with trained counselors to stabilize multidimensional imminent danger. Less intensive milieu and group treatment for those with cognitive or other impairments unable to use full active milieu or therapeutic community |

| 3.5 | Clinically Managed High-Intensity Residential Services | 24-hour care with trained counselors to stabilize multidimensional imminent danger and prepare for outpatient treatment. Able to tolerate and use full active milieu or therapeutic community |

| 3.7 | Medically Monitored Intensive Inpatient Services | 24-hour nursing care with physician availability for significant problems in Dimensions 1, 2, or 3; 16 hours/day of counselor availability |

| 4 | Medically Managed Intensive Inpatient Services | 24-hour nursing care and daily physician care for severely unstable patients |

SOURCE: Data from https://www.asam.org/asam-criteria/about-the-asam-criteria

complete abstinence or a reduction in use, not by a pre-prescribed length of a treatment program (e.g., 28- or 30-day residential program; Mee-Lee et al., 2013).

Regardless of the entry point for substance use disorder treatment, people must first be physically stabilized. Decreased use, particularly of alcohol, benzodiazepines, and opiates, can lead to significant physical symptoms. In the case of alcohol and benzodiazepines, the process of withdrawal can be life-threatening and often requires the oversight of medical

providers and incorporation of MAT when people have been using long-term and/or have been using large amounts. The assessment, as described above, is important for determining what level of care is needed to safely and humanely facilitate withdrawal or plan for decreased use without exacerbating symptoms.

Importantly, withdrawal management is not sufficient treatment for substance use disorders; removing the substances from the body is often a necessary first step, yet it is not sufficient for obtaining and sustaining sobriety. Repeated withdrawal episodes can exacerbate the severity of withdrawal for people with alcohol use disorders; this is known as kindling (Becker, 1998). People who experience seizures as part of the detoxification process are more likely to have had repeated episodes of detox and have poorer prognosis and higher mortality rates (Becker, 1998).

Given that addiction is frequently persistent, research supports long durations of care consistent with other chronic health conditions (McClellan et al., 2000; NIDA, 2007) for best outcomes. Regardless of entry point on the continuum of care, the early phases need to provide psychoeducation and encouragement for treatment engagement. It is during these earliest days of sobriety that symptoms of co-occurring disorders may resurface with greater severity and emotions may become more intensely experienced; it may be the first time in years a person has fully experienced their guilt and shame, symptoms of anxiety, depression, and trauma without the escape of a substance. Some will experience symptoms of acute withdrawal, but for some these symptoms can persist for months as post-acute withdrawal syndrome (Bahji, 2022). These early days of treatment are particularly challenging as people often lack healthy means of coping.

Early Recovery and Maintenance Phases

Early recovery, approximately the first six weeks to three months of any level of care, should be highly structured (SAMHSA & the Office of the Surgeon General, 2006). This is necessary to shift behavioral default networks, that is, to shift from using substances to cope to using new, healthier, substance-free behaviors for recovery. Patients are supported in identifying their own triggers to use and implementing coping strategies to sustain abstinence. They are encouraged to connect with sober mutual-support communities, and also may benefit from external accountability, such as random drug and alcohol testing. Few studies have examined whether drug testing improves treatment outcomes, but some evidence suggests workplace drug testing is associated with reductions in substance use and reductions in occupational injuries (Sheridan & Winkler, 1989). Further, ASAM expert consensus is that drug testing can be useful during and after treatment to improve treatment outcomes (Jarvis et al., 2017).

The maintenance phase of treatment continues to build on early recovery. The goal of abstinence remains the same, and implementation of relapse-prevention skills and ongoing care for co-occurring conditions (i.e., in the physical, emotional, behavioral, cognitive, social, and spiritual domains) continues. People with substance use disorders and a goal of complete abstinence broaden their social support networks, build a “life worth living,” and continue to address co-occurring conditions. Their bodies continue to recalibrate to a life without substances and they become more easily able to implement healthy coping skills and grow better at recognizing and tolerating the experience of urges and cravings without relapse. If a relapse occurs, it provides insight into areas the individual has not yet adequately addressed for sustaining long-term recovery and might indicate the need for a higher level of treatment.

The final stage of treatment as outlined by SAMHSA is the stage of community support (SAMHSA, 2006). While the goal of abstinence remains, the individual leans more on their community of support and distances themselves from formal treatment settings. A relapse may indicate the need to return to a more formalized level of clinical support within the continuum of care.

Transitions to a lower level of care create important opportunities for communication and collaboration between treatment providers, the patient, and their support network. While transitions may be times to celebrate the progress made, they can also be times when the risk of relapse is high if the level of support shifts too quickly. A detailed discharge plan that addresses each domain of the ASAM criteria can help facilitate a smooth transition between levels of care. It is also important to be mindful that too many aspects of a person’s life are not shifting at the same time. For example, patients who transition to a lower level of care at the same time that medication changes are happening or who are leaving a sober living environment often struggle to maintain sobriety. At all levels of care, the treatment, discharge planning, therapy goals, and safety planning must be individualized to the patient and their unique needs based on multidimensional assessments. Incorporation of identified family and comprehensive discharge planning further improves outcomes.

It is difficult to make generalizations about the effectiveness of addiction treatment based on the literature, due to many challenges and variables: unique populations studied (e.g., people with alcohol use disorders vs. people with opioid use disorders); unique treatment conditions (e.g., high fidelity to treatment interventions by study clinicians vs. treatment as usual in nonresearch populations); different treatment outcomes (e.g., reduction in use vs. abstinence from use, self-report vs. objective measures); and different follow-up periods (e.g., months into treatment vs. months or years after treatment; Fleury et al., 2016). One estimate is that 40 to 60 percent

of patients treated for substance use disorders are abstinent at one year after treatment (McLellan et al., 2000). However, there is considerable variability in estimates. Research has shown that both person factors and treatment factors affect treatment outcomes. For example, people with less severe substance use disorder, less psychiatric comorbidity, higher readiness to change, more social support, positive social context (employment, higher socioeconomic status, greater education), and more purpose in life tend to show better treatment outcomes (Sliedrecht et al., 2019).

There are few high-quality studies of treatment outcomes among professionals in safety-sensitive industries. A number of peer-reviewed articles have been published on chart reviews of physicians receiving substance use treatment through Physician Health Programs (PHPs). These articles document that approximately 80 percent of the physicians followed over five years of intensive monitoring showed no positive alcohol or drug test results (Dupont et al., 2009; McLellan et al., 2008). One claim is that these high success rates are attributable to the PHP care management model, as opposed to “person” factors such as physicians’ high intelligence and financial resources (Dupont & Merlo, 2018). However, little is known about the specific reasons underlying the reported high success rates of this model (Merlo et al., 2022). Importantly, all PHPs may not be equal. Claims have been made about the questionable quality of some PHPs which vary across states (Lenzer, 2016). Some of the concerns include lack of documented criteria for selecting treatment centers and lack of objectivity in evaluation of physicians’ need for substance use treatment, culminating in calls for regular audits (Lenzer, 2016).

MAT

MAT has been demonstrated to improve the outcome of treatment and, in the case of opioid use disorder, it is considered essential and lifesaving (Wakeman, 2017).

At all levels of care, the consensus position of substance use treatment professionals is that treatment plans should include the option for MAT for people seeking abstinence from alcohol, opioids, or tobacco.6 Treatment providers and centers not offering this form of support are restricting

___________________

6 Although there is substantial evidence for medications to treat co-occurring psychiatric illness in people with substance use disorders and evidence that the treatment of co-occurring disorders improves addiction treatment outcomes, this report will not examine this important aspect of medication as the FAA has a separate program for mental illness-related medication (for more information, see https://www.faa.gov/ame_guide/app_process/exam_tech/item47/amd/antidepressants). The main focus in this section will be on MAT for alcohol use disorders and for opioid use disorders. A detailed overview of available medications for tobacco cessation is available at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2020-cessation-sgr-full-report.pdf

life-saving care and denying FDA-approved medication. Rates of relapse and overdose are significantly decreased by the integration of these medications in conjunction with the continuum of therapeutic addiction care. MAT improves long-term recovery outcomes and can prevent overdose. However, as discussed in later sections, there are special considerations for the use of some of these medications by safety-sensitive professionals.

Medications for the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorders

Three FDA-approved medications for the treatment of alcohol use disorders are currently available: disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate. Disulfiram, which results in toxicity if alcohol is consumed, should only be prescribed for patients who wish to achieve complete abstinence and understand the risk of using alcohol while taking disulfiram. There is evidence from multiple studies that it works best when its administration can be monitored (Skinner et al., 2014).

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist that has been shown to be effective in the treatment of both opioid and alcohol use disorders. Naltrexone administration has been associated with greater likelihood of alcohol abstinence, fewer drinking days in those who are not abstinent, and a reduction in alcohol craving (O’Malley, 1996). Naltrexone is available as an oral medication, which may be taken daily and as a depot injection administered monthly.

Acamprosate’s effectiveness was established in Europe, where it was typically prescribed after a period of alcohol abstinence. Although it is generally well tolerated, it requires oral administration every eight hours, making treatment adherence more difficult. In a meta-analysis comparing trials of acamprosate with trials of naltrexone, acamprosate was found to be slightly more efficacious in promoting abstinence and naltrexone slightly more efficacious in reducing heavy drinking and craving (Bouza et al., 2004).

Medications for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorders

Three FDA-approved medications for the treatment of opioid use disorders are currently available: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Methadone is an opioid receptor agonist medication and is a Schedule II drug under the Controlled Substances Act. Although methadone is often described as “controversial” and has been criticized and stigmatized as a treatment that “trades one addiction for another,” there is good evidence that methadone improves a wide variety of outcomes related to opioid use disorder and that continued improvements are seen as duration of treatment with methadone lengthens (Castells et al., 2009; Connock et al.,

2007; Lim et al., 2023). Methadone is considered an “essential” medication by the WHO, and its use within the United States has occurred almost exclusively in a system of federal and state licensed and regulated Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs). These regulations prescribe many aspects of treatment such as the need for daily attendance by patients and medication doses allowed in treatment. It is illegal for methadone to be prescribed for the treatment of an opioid use disorder outside of an OTP. It is legal for methadone to be prescribed without such oversight for pain relief, although deaths due to methadone overdose have been more frequent in people receiving methadone for pain than in those who receive it for opioid use disorder (Jones et al., 2016). Professional medical organizations have advocated for greater flexibility in the regulation of methadone treatment for opioid use disorder, because it is safe and effective when prescribed by knowledgeable professionals and because the current treatment system is difficult for patients to access and navigate.

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist at the mu opioid receptor. As with methadone, it is considered an essential medication by the WHO. Whereas methadone is a Schedule II drug under the Controlled Substances Act, buprenorphine is a Schedule III drug, which means it is seen as a drug with less misuse potential. This Schedule III status was important in permitting its prescription in individual office-based practices rather than OTPs, although OTPs are permitted to dispense buprenorphine. The 2000 Drug Addiction Treatment Act allowed physicians to use buprenorphine to treat patients at their office rather than only in an OTP. A mandatory educational requirement, “the X-waiver” was established as part of the act. However, due to the safety and effectiveness of buprenorphine and the need for more available buprenorphine in attempts to reduce deaths from opioid overdose, the need for this waiver was eliminated in 2023. Buprenorphine and methadone seem to have equivalent efficacy in the treatment of opioid use disorder (Lim et al., 2022; Mattick et al., 2014; West et al., 2000), though methadone is associated with better treatment retention.7 Buprenorphine is now available as an extended-release, monthly subcutaneous injection that can enhance treatment adherence.

Naltrexone is a mu opioid receptor antagonist. Initial trials of oral naltrexone for the treatment of opioid use disorder were disappointing because of poor treatment adherence in treated populations (Minozzi et al., 2011). The availability of a depot form of naltrexone that can be given as a monthly injection, although originally developed for the treatment of alcohol use disorder, was recognized as an important potential treatment

___________________

7 The citations are consistent with prior data, but there is a growing clinical sense that individuals using fentanyl are treated more effectively with methadone than buprenorphine, in the professional experience of some committee members.

modality for opioid use disorder. The efficacy of extended-release injectable naltrexone (XR-naltrexone) compared to placebo was determined by Russian studies; the FDA based its approval for OUD on these studies as well as on the safety profile established for XR-naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol use disorder. More recent studies raise concerns about the efficacy of XR-naltrexone compared with methadone or buprenorphine in important outcome measures for opioid use disorder (e.g., overdose prevention; Wakeman et al., 2020).

ONGOING HEALTH STATUS MONITORING AND TESTING

While in treatment, toxicology testing is typically left to the discretion of the treating clinician, unless it is embedded in regulations associated with the treatment, such as in OTPs where methadone is dispensed, or when treatment is mandated by a criminal justice agreement. When left to clinical judgment, toxicology testing may be done infrequently if patients are assessed as doing well. People not in treatment generally do not participate in toxicology testing unless involved in a monitoring program, most typically through their work or the criminal justice system.

Jarvis and colleagues (2017) made a number of recommendations in an ASAM consensus statement titled Appropriate Use of Drug Testing in Clinical Addiction Medicine, including that testing should be more frequent during the beginning of treatment and decreased depending on progress. Additionally, testing should be done at least monthly “when a patient is stable in treatment,” and that “individual consideration may be given for less frequent testing if a patient is in stable recovery” (Jarvis et al., 2017).

For safety-sensitive professionals, with abstinence viewed as a critical outcome, biologic measures are especially prominent in monitoring health status to prevent impairment at work. Although substance use may not in itself suffice to define relapse into an active disease state, agreements that allow safety-sensitive professionals to return to work are typically clear that substance use could and usually will result in removal from work. This is not to say that clinical judgment of treatment engagement and response from clinicians providing treatment to safety-sensitive professionals are unimportant, or that perceptions from the worksite are unimportant in assessing a professional’s health. Rather, clinical and worksite monitors may not be sufficiently sensitive to relapse, particularly if it begins in a limited way. In contrast, random testing provides an objective measure of substance use when indicated and sufficiently frequent, using a variety of testing matrices (Jarvis et al., 2017).

A variety of testing matrices have been developed to detect substance use, each with benefits and limitations. Urine is the most common matrix

used. Breath alcohol content can also provide concentrations of alcohol use and provide critical information if levels correlate with impairment. In a monitoring program that expects alcohol abstinence, breath alcohol with its relatively narrow window of detection may need to be supplemented with urine or blood alcohol metabolite testing. A variety of at-home breathalyzer and urine drug testing options are now available to support long-term sobriety (e.g., BACtrack, RecoveryTrek, PROOF Testing, Soberlink). These tests provide observation through cellular devices, commonly in the form of photo or video at the time of sample, making regular testing more convenient and available over weekends and holidays.

Outcomes for physicians in structured monitoring programs—in which a positive test will reliably result in being removed from work—are reported to be the best in addiction treatment. It is possible that toxicology monitoring with clear contingencies for positive tests is an important driver of these reported outcomes, but there is almost no research on whether toxicology testing, as opposed to other aspects of treatment, improves treatment outcomes (Jarvis et al., 2017). Consensus opinion, however, recommends the use of toxicology testing in assessment and monitoring to support recovery (Jarvis et al., 2017).

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS ACROSS THE SPECTRUM OF TREATMENT OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS FOR PROFESSIONALS IN SAFETY-SENSITIVE OCCUPATIONS

Well-regarded guidelines for best practices, such as ASAM’s, that are built on “a foundation of evidence… and expert consensus” (American Society of Addiction Medicine, n.d.),8 assert that due to the concerns for public safety when a professional in a safety-sensitive occupation has a substance use disorder, “treatment should be aggressive and definitive” (Mee-Lee et al., 2013). ASAM therefore recommends that professionals in safety-sensitive occupations participate in treatment that “has the best chance of establishing stable recovery.” This approach to identifying the appropriate level of care is notably different from what is recommended for the general population. It is not clear from research which treatment elements of what is proposed as “aggressive and definitive” produce benefits. Individualized treatment combined with accountability through rigorous monitoring and MHGs produces positive effects, yet any one of these elements alone may not be sufficient. However, across treatment programs there are best practices and recommended elements that have emerged that are particularly relevant to the success of treating professionals in

___________________

8 For more information on the ASAM Criteria evidence base, see https://www.asam.org/asam-criteria/about-the-asam-criteria/evidence-base

safety-sensitive occupations such as pilots and flight attendants. The key elements the committee selected for consideration include individualized care and required length of stay, role of stigma, use of MAT, release of information and confidentiality, and having access to a cohort of peers. Each is discussed next, in turn.

Individualized Care and Required Length of Stay

While duration of treatment, sometimes referred to as length of stay (LOS), should be individualized based on ongoing assessments using the ASAM dimensions, a recommended level of care and LOS are often assumed for pilots because of the high risk to the public in the event of a relapse. HIMS most commonly expect pilots who meet the FAA definition of substance abuse and dependence to engage in residential treatment, regardless of severity of substance use disorder, and to have a minimum LOS at this level of care of roughly 30 days. This requirement of residential treatment is consistent with what is typically required of physicians with substance use disorders involved in physician health programs; their LOS in residential care most commonly ranges from 30 to 90 days (McLellan et al., 2008). For many professionals who do not seek treatment until required because of problems at work, their substance use disorder may have progressed to being severe and may necessitate residential treatment. However, in cases of professionals with mild substance use disorders, residential treatment may not be indicated (Boyd & Knight, 2012; DuPont et al., 2009). For example, a physician with an isolated arrest for DUI may not meet criteria for having a substance use disorder nor require treatment at the residential level.

However, research does not clearly indicate that residential treatment is superior to less costly and less confining outpatient levels of care (Beaulieu et al., 2021; McCarty et al., 2014). Depending on the structure, a residential program might not offer more intensive treatment than an outpatient program nor meet the unique needs of the individual requiring treatment. Residential treatment is often cited as contributing to good outcomes for professionals in safety-sensitive occupations, yet it is unclear from research whether this is as important as ongoing treatment, regular toxicology monitoring, engagement in a professional monitoring program, or the combination of these elements (Beauliu et al., 2021; McCarty et al., 2014). Moreover, many professionals in safety-sensitive occupations do not complete these lengthy residential stays yet are able to obtain recovery, both people known to their professional monitoring organization and those seeking care outside of that organization (Beauliu et al., 2021, McCarty et al., 2014). In the clinical experience of some committee members, the requirement of completing residential treatment often checks a box for many professionals; however, poor-quality programs do not provide adequate

intervention, do not individualize the care, and often let the professional dictate their care in ways that are problematic. Individual PHP, HIMS, and FADAP identify which treatment providers are acceptable for their participants; however, these lists are always evolving and are typically not public, and the criteria used for identifying acceptable treatment programs are unknown.

Another challenge of residential treatment is that it is expensive. Very few insurance plans will cover a 30- to 90-day residential LOS that pilots and physicians are held to. Many professionals go into significant debt to successfully complete treatment, maintain compliance with their professional monitoring organization, and return to work; this financial burden then becomes a clinical issue for many.9 For example, a survey of 133 physicians who had completed a PHP monitoring agreement for their substance use disorder at least five years in the past (by January 2009) found that out-of-pocket personal costs ranged from $250 to $321,000 (M = $31,528, SD = $39,570; Merlo et al., 2022). A further challenge potentially facing pilots is gaining admission and clearance from insurance to get into required residential treatment when a pilot meets the FAA definition of abuse or dependence but does not meet the DSM-5 definition of a substance use disorder. People who cannot pay may be discharged before successfully completing the clinically recommended treatment, which can result in a discharge against clinical advice, complicating the pilot or physician’s return to work.

In the clinical experience of some committee members, few safety-sensitive professionals are required to comply with clinical recommendations of 30 to 90 days in residential treatment, most commonly physicians and pilots. Other safety-sensitive professionals, including flight attendants, nurses, train engineers, law enforcement, and attorneys, typically engage in residential treatment as dictated by insurance coverage.

Stigma and Fear of Job Loss

The public often holds stigmatized views toward individuals with mental illness, and the intensity of these stigmatized views is greater for substance use disorders than for other psychiatric disorders (Yang et al., 2017). The experience of stigma itself is associated with an increased risk for substance use (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016) and considered a social determinant of health. Experiences of stigma can be distinctive, depending on the context. For example,

___________________

9 Information from a committee-hosted public workshop, available https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/11-01-2022/workshop-on-dealing-with-substance-use-disordersand-strengthening-well-being-in-commercial-aviation

individuals with opioid use disorders can experience greater stigma than people who use alcohol because, unlike alcohol, some opioids are used illicitly (Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2017). The experience of stigma can arise from structural, public or social, and internalized sources. These different categories of stigma intersect with other factors such as race, gender, socioeconomic status, age, professional identity, and sexual orientation, potentially contributing to challenges in seeking or obtaining treatment (Cheetham et al., 2022; see Box 3-3).

The stigma of having a substance use disorder remains pervasive in our culture, and it is further heightened for professionals in safety-sensitive occupation (Roche et al., 2019). This stigma is exacerbated by professions that come with prestige and work environments that expect their employees to perform at optimal levels despite significant strains. Thus, when a professional is required to seek a substance use assessment, they are motivated to keep their career and may attempt to delay or avoid treatment as a result. The image of being a professional conflicts with what people have internalized as being an addict, preventing them from recognizing they need help and seeking the support. In the committee’s professional experience, this stigma facilitates the progression of the disease. Additionally compounding this, racial and ethnic minority groups more often experience mental health stigma (Eylem et al., 2020); this perhaps suggests that pilots working among white-majority colleagues who identify as a person of color or as a member of a marginalized community might need additional supports as part of the prevention and treatment of their substance use disorder.

Stigma is integrated and reinforced through workplace policies, insurance coverage, and support made available to employees if they report a problem, their work suffers as a result of a problem, or they are identified as being under the influence at work. As an example, the FAA requires the disclosure of all care sought on the Application for Medical Certification (FAA Form 8500-8); this form is completed by commercial pilots every 6 to 12 months. HIMS and the FAA are public in their support for and encouragement of pilots seeking help and report that it is a myth that substance use treatment is not allowed. The dilemma is that pilots could interpret some questions on that application form as being in direct conflict with HIMS’ and the FAA’s statement. For example, one question requires pilots to report all visits to health professionals within the last three years, including the date, name, address, type of health professional, and the reason for the visit. Pilots lie on this form if they do not report having sought help or seek help through out-of-pocket resources. While the FAA is duly obliged to monitor pilot health, it could unintentionally cause a public-safety risk if some pilots are avoiding needed care to be in compliance with this rule and maintain the medical certificate needed for their job. One study of pilots in Norway sheds light on underreporting; nearly 12 percent of pilots in this

study (N = 1,616) admitted to underreporting information to their AME about one or more conditions, some even acknowledging that their underreporting may have affected flight safety “some” or to a “high extent.” The number of pilots underreporting was higher for commercial pilots (nearly 16%) in comparison to other medical classes (Strand et al., 2022) and

5.5 percent of participants underreported related to their drug and alcohol use. Furthermore, 49 percent of responders reported knowing a colleague who had underreported information, and 31 percent believed this affected flight safety “to a high extent” (Strand et al., 2022). Notably, the authors state that “the magnitude of underreporting that is evident in these results just represent a minimum share of the actual magnitude” (Strand et al., 2022, p. 382).

This is also reflected in the rate of reported depression in pilots, which is estimated to be 50 percent higher than the rate among the general population (12.6%) and in the fact that 4.1 percent of commercial pilots report suicidal thoughts (Wu et al., 2016). “The mental well-being of a pilot is paramount to his/her flight safety” (Lewis et al., 2014), yet some pilots could perceive current policies as prohibitive to obtaining mental health care.

While aircraft-assisted pilot suicides are very rare (0.29% of all in-flight fatalities; 8 of 2,758 fatal aviation accidents), all eight airmen involved in clearly documented incidents of this type of suicide between 2003 and 2012 had been medically certified to fly and none had reported mental illness, use of an antidepressant medication, or prior suicide attempts (Lewis et al., 2014). Half of them had disqualifying substances including alcohol, benzodiazepines, and antidepressant medications in their system at the time of the suicide; the two taking antidepressants had not disclosed this to their AME, and no pilot had alerted their AME about depression or suicidal ideation (Lewis et al., 2014).

A study conducted by the National Transportation Safety Board in 2020 indicated that substance use continues to increase among fatally injured pilots (N = 1,042), with the overwhelming majority of incidents occurring in noncommercial, recreational aviation; 28 percent of these pilots between 2013 and 2017 tested positive for at least one substance with the potential to produce impairment, including 48 percent of such pilots in 2017 (National Transportation Safety Board, 2020). The most commonly identified drug was diphenhydramine (Benadryl), an over-the-counter sedating antihistamine. A subset of pilots were identified as using medications that could indicate an underlying impairing condition. For these pilots, the three most common identified drugs were hydrocodone, a sedating opioid used to treat severe pain; citalopram, an antidepressant; and diazepam, a sedating benzodiazepine used to treat severe anxiety and muscle spasms (National Transportation Safety Board, 2020).10 While the FAA is clear in its stance on the use of impairing substances, a percentage of pilots are using them, obtaining prescriptions, and not reporting these to their AMEs and risking public safety (Strand et al., 2022).

___________________

10 After a prepublication version of the report was provided to the FAA, this section was edited to clarify the identified substances with the potential to produce impairment.

The mental well-being of a pilot is paramount to his or her flight safety, yet current policies are perceived as a barrier to seeking mental health care. Decreasing stigma associated with substance use disorder within professional organizations can be an important first step to prevention of disease, including early access to help for professionals in safety-sensitive occupations.

Pilots and Medication for Addiction Treatment

The benefits of any medical treatment must be weighed against the risks posed by treatment, and for professionals in safety-sensitive occupations the risks may be greater given the potential for untoward neurocognitive and motor effects. Current scientific consensus would not support a blanket ban on MATs, as impairment occurs along a range (Kay & Belanger, 2023); instead, each MAT-pilot combination should be context-specific and carefully considered by the AME, consistent with the FAA’s policies towards other potentially impairing diagnoses. The Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy is a drug safety program that the FDA can require for medications with serious safety concerns; the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy helps ensure that the benefits of a medication outweigh its risks. The question should be whether the FAA and other oversight organizations for pilots, flight attendants, and other professionals in safety-sensitive occupations are able to sufficiently evaluate and mitigate the risk associated with MAT.

The majority of flight attendants and pilots with substance use disorders have an alcohol use disorder (HIMS & FADAP, 2022). Some FDA-approved medications for the treatment of alcohol use disorders have few, if any, problematic neurocognitive effects, and motor effects are typically transitory and disappear during treatment (Kay & Belanger, 2023). While these studies do not include pilots (likely for the inherent dangers of conducting a double-blind study on safety-sensitive professionals), a pilot with a substance use disorder could be stabilized using MATs that are deemed likely to be minimally impairing based on the current available science and then tested by the neuropsychologist. If impairment is present, they could be taken off the medication and re-evaluated.

Fewer pilots in HIMS have opioid-related difficulties and opioid use disorders; however, the relapse rate to opioids in the HIMS program is higher than that for alcohol use disorders. These numbers, if they match national trends, may be on the rise, and the number of flight attendants with opioid-related difficulties and opioid use disorders may be higher than that of pilots. Rates of opioid use disorder have been trending upward for decades, and kratom is becoming more widely used; it activates the opioid receptors, and it is legal, believed by many to not be addictive, and rarely tested for in standardized drug screens (Olsen et al., 2019).

Some FDA-approved medications for the treatment of opioid use disorders have potential neurocognitive effects (Kay & Belanger, 2023). However, pilots in HIMS are required to complete rigorous neurocognitive assessment and an assessment of relevant motor skills prior to being cleared to return to flying. Thus, pilots stabilized on MAT could be tested and any concerning cognitive impacts would be identified, as in the process described for alcohol use disorder. Both examples would rely heavily on an effective cognitive screen, and it is unclear how much research, if any, has been done by HIMS-trained neuropsychologists to specially look for MAT-related impairment. Given that pilots are often out of work for up to a year in these scenarios, cognitive testing with two to three months of sobriety and stabilization on these medications could still allow time for retesting without the medication if cognitive concerns are present at the time of initial testing.

The FAA’s limitations on MAT are overly restrictive by a benefit-to-risk analysis based on the best available evidence as previously described.11 Professionals in safety-sensitive occupations would benefit from being offered and encouraged to use these medications, particularly naltrexone and buprenorphine, to aid their recovery and prevent relapse and overdose, both during withdrawal management and as ongoing treatment. Providing the most powerful intervention for treating opioid use disorders would significantly decrease the rate of relapse and minimize the risk of overdose for pilots, flight attendants, and other professionals in safety-sensitive occupations.

ROIs and Confidentiality

ROIs facilitate communication among treatment providers, programs, collateral contacts, identified supports, and professional monitoring organizations. Without ROIs, patients can maintain complete confidentiality over their treatment involvement, sometimes to their detriment due to minimization as noted above and lack of collateral information. Many professional monitoring organizations, including HIMS (but not FADAP), require an open ROI, which must allow for any and all information and records to be provided by the treatment provider. Not having such an ROI on file can result in the participant being out of compliance with their monitoring agreement, which in turn can lead to the professional being out of work longer and being reported to their licensing board. While there is a valid public safety reason to differentiate, HIMS requires that the full treatment record be included in records reviewed by the AME during their

___________________

11 After a prepublication version of the report was provided to the FAA, this section was edited to accurately reflect FAA policies.

consideration of a pilot’s return to the cockpit, whereas flight attendants have complete confidentiality through FADAP.

The resulting dilemma (with no easy resolution) is that for many patients in safety-sensitive occupations involved with oversight organizations, this ROI is seen as a barrier to full disclosure in treatment. When the monitoring program is not seen as supportive, people are more likely to withhold information out of fear of the consequences for their career (Strand et al., 2002). These patients often withhold trauma histories and minimize mental health symptoms out of fear that their oversight organization will have these details and prevent them from returning to work. This underreporting prevents the patient from receiving the care they truly need, and for many it can lead to requiring repeat episodes of treatment. This issue intersects with the importance of individualizing treatment and the concern for public safety. Treatment plans for people experiencing symptoms related to trauma must take this into consideration; it changes treatment goals and recommendations made. Not addressing symptoms of anxiety and depression can disrupt the functionality of the coping skills taught.

It is well documented that co-occurring disorders complicate the course of recovery; however, recovery is possible if these issues are addressed concurrently with the substance use disorder. While communication with professional monitoring organizations is important, limited ROIs could facilitate this while providing increased confidentiality to the patient. Working with treatment providers or centers that have a thorough understanding of the unique needs of professionals in safety-sensitive occupations and the needs of their monitoring organizations can ensure that both the patients’ and the oversight organizations’ needs are met.