Sponsor Influences on the Quality and Independence of Health Research: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 5 Considering Models, Processes, and Principles to Protect Research Independence and Quality

5

Considering Models, Processes, and Principles to Protect Research Independence and Quality

The final session featured five presentations designed to provide the attendees with suggestions for how to protect research independence and quality. Sunita Sah, associate professor at Cornell University and fellow at the University of Cambridge, discussed some of the psychological processes involved when considering conflicts of interest (COI). Rita Redberg discussed the appropriate role of a sponsor in studies. Quinn Grundy, assistant professor in the Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing at the University of Toronto, addressed alternative sources of funding for biopharmaceutical research. Vincent Cogliano, deputy director for scientific programs at the California EPA Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, spoke about protecting the scientific integrity1 of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monographs. Finally, Craig Umscheid, director of the Evidence-Based Practice Center Division and senior science advisor at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), discussed ways of addressing conflicted research when synthesizing evidence. Following the presentations, Tracey Woodruff, professor at UCSF, and Joel Lexchin, professor emeritus at York University, provided their insights from the presentations and joined the speakers for a discussion moderated by

___________________

1 Scientific integrity refers to scientific research that is free from politically motivated suppression or distortion. See: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/01-22-Protecting_the_Integrity_of_Government_Science.pdf (accessed April 21, 2023).

C. K. Gunsalus, director of the National Center for Principled Leadership and Research Ethics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

A DEEP DIVE INTO PROFESSIONALISM: POTENTIAL POLICY APPROACHES TO COIS2

Sah noted that several policy solutions for addressing COIs, such as fines, sanctions, education, second opinions, and disclosure, are largely based on inaccurate intuitions regarding the underlying psychological processes (Sah, 2017). As a result, they tend to fail or have unintended consequences. Two possible solutions, she said, are disclosing COIs and cultivating professionalism.

Sah has studied disclosure extensively, particularly regarding the psychological effects on both recipients (people reading the disclosure statement) and disclosers (those who make a disclosure statement), to see where it hurts and where it could help. In fact, disclosure is the most commonly proposed and implemented solution for dealing with COIs across range of industries and sectors. It is popular for recipients, Sah explained, because it can alert them to potential bias and allow them to decide whether to discount the conclusions or recommendations. “Some

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation of Sunita Sah, Cornell University.

people love this because it appeals to our principles for transparency and free markets,” said Sah.

Her research has found, however, that a disclosure requirement itself does not work well because even when it is written in simple and clear language, people do not know what to do with it, ignore it, or discount it erratically (Rose et al., 2021; Sah, 2019b; Sah et al., 2016). “There is this large variance, which makes sense,” said Sah. For recipients to interpret a disclosure, they need to have a mental model of how the COI has biased the recommendations. Then they can discount the recommendations for exactly that amount of bias.

Studies have found that disclosure of funding sources with a COI may make some physicians less willing to prescribe the drugs in the paper, regardless of the scientific rigor of the study (Kesselheim et al., 2012). Decreased confidence could be an appropriate response to a COI disclosure, said Sah. She noted that even when the reader is confident about the high quality of the advice that a paper may provide, what she calls a “disclosure penalty” remains (Sah and Feiler, 2020).

Sah identified problematic unintended consequences of disclosure. She has found that when a person is under a high cognitive load, they process a disclosure automatically or peripherally, as opposed to deliberating and focusing on what the disclosure actually means; it becomes a cue to the clinician’s expertise and increases trust. She has also found even with decreased trust, which is arguably the correct response to COIs, readers will still comply with the recommendations in a paper because of an unwillingness to signal distrust to those who are disclosing.

Disclosure might be attractive to a discloser, as it can relieve the person of guilt for any unfavorable outcomes, Sah said. It can also limit professional liability. At the same time, she and her collaborators have found that disclosure can lead people to reject COIs so they can announce the absence of any COIs (Sah and Loewenstein, 2014). “People are motivated to appear unbiased, and disclosure works best not when it depends on consumers responding effectively but rather when it influences the behavior of the people whom the disclosure is about, encouraging them to improve and reject conflicts of interest,” said Sah. In other words, reputational concerns or an aversion to being viewed as corrupt could be driving this effect.

Across several studies, Sah has found that the effect of disclosure on providers depends on the salience of the professional norms and what those norms are. For example, in a financial context, a “self-interest first” norm, which many laypeople believe about the industry, bias increases with disclosure in that it can change and lower the quality of the advice. In the medical context, where the norm is patient first, bias decreases with disclosure (Sah, 2019a).

The key, said Sah, is how professional norms influence what people think is the right thing to do in a given situation. “Disclosure can improve the quality of advice, but only if the norm is to place clients first, patients first, readers first, the public first. It acts as a reminder to do the right thing,” said Sah. “Just reminding people that you have a conflict of interest works in the same way as the conflict-of-interest disclosure.” She added that a self-interest first norm can lead to increased bias in the advice, but disclosure can be a signal that reminds advisors to place advisees first and leads them to rein in bias (Sah, 2019a).

The biggest psychological process to overcome, said Sah, is the amazing ability people have to rationalize. “Once we have disclosed, we think we have dealt with our moral obligations with respect to COIs, and rationalization can crowd out more effective solutions than managing COIs,” she said. She does not recommend disclosure as a solution to managing COIs unless it leads people to reject conflicted funding themselves and improve the quality of their advice.

The concept of professionalism, said Sah, has evolved into one that describes how one conducts oneself, or, as one pair of scholars defined it, “a set of values and identities that can be mobilized by employers as a form of self-discipline” (Aldridge and Evetts, 2003). Other scholars state that a belief in self-regulation is a key aspect professionalism (Cheney et al., 2010; Hall, 1968), as is the ability to actively manage the conflict between the client and personal interest to favor the client (Nanda, 2003). If professionalism is a self-concept, the question is whether improving integrity and professionalism will lead to rejecting conflicted funding or make matters worse.

This is an important question, said Sah, because people often think they are immune to unwanted influence. Physicians, for example, say they are not influenced by industry incentives, although they might think that other physicians are likely to be. This often self-serving justification, she explained, leads to a lack of ability to predict influence, which is why physicians and other professionals take great offense at the idea that they could be influenced by financial incentive. “Although a strong sense of professionalism might help defend against intentional corruption, it does not mitigate against unintentional or implicit bias that arises from conflicts of interest,” said Sah.

She has found that a high self-concept of professionalism often coexists with a shallow notion of the concept. This can lead paradoxically to detrimental outcomes, such as increased unethical behavior and increased vulnerability to COIs (Sah, 2022). Those with a strong sense but shallow understanding of professionalism might be more likely to accept COIs because of their high confidence in their ability to consciously control for any influence, as seen with overeating and smoking. “If we have a

strong belief in our own ability to regulate, we will not remove the high-calorie foods from our house, or a cigarette packet from our pocket, so we are more likely to lapse and eat more and smoke more than we want,” explained Sah.

In addition, once a physician perceives a COI, a high sense of professionalism may reassure them they can ward off influence, so they work less hard to correct for bias, ironically leading to both greater acceptance of COIs and more bias. “There could be this double harm that can arise from professionalism, in that it makes people more vulnerable to view conflicts of interest as acceptable and succumb to the bias from conflicts of interest,” said Sah. Because people remain unaware of the bias, they cannot predict it or recognize it in hindsight, she added.

She called for “deep professionalism”: recognizing the risks of undue influence and avoiding COIs in the first place (Sah, 2022). Individuals with deep professionalism embrace continued ethical training to help embed principles and display it with repeated ethical behaviors, said Sah. For example, if a hospital policy bans pharmaceutical representatives from interacting with physicians in their hospitals and ends free lunches, physicians who understand deep professionalism will also reject walking across the street for the free lunches that the company now offers in a hotel conference room. Even though the policy does not regulate behavior outside of the hospital, those with deep professionalism will understand and internalize the principles and values of self-regulation and nurture their values repeatedly with active practice (Sah, 2022).

One solution is to integrate both approaches: have clear policies and procedures to eliminate or mitigate COIs and cultivate deep professionalism. For example, institutions could allow receiving conflicted funding, if researchers are separated from decisions involving the source and do not know the funders’ identity. Such a policy needs to be implemented before specific situations arise to avoid distortions, said Sah.

She recounted how one hospital created a central fund where industry could contribute and physicians could apply within the institution. The problem was that after funding, the hospital revealed the source and the physician had to write a thank-you note, which degraded the independence of the research. Bero has been at two institutions that tried to implement a pooling mechanism; companies pulled their funding, presumably because their funding would not be recognized and they could no longer have influence. Sah suggested that companies could disclose how much they put toward independent research and treat that as a positive outcome by showing their commitment to transparency.

Sah said that along with open data, preregistration, registered reports, and a grade or rating on the degree of conflict, cultivating deep professionalism could lead to a self-calibrating effect that motivates people to do

better and produce higher-quality research. “Integrating these approaches, I believe, is the best approach to managing conflicts of interest,” she said.

Gunsalus noted that she has recently encountered a generational concern about the concept of professionalism, that it is limiting and imposing old-style views. Sah replied that she can understand that pushback if professionalism dictates work clothes and other aspects of formality, proposing that “we need to get away from professionalism as being a character trait but more as a set of repeated behaviors that demonstrate ethical behavior.”

ROLE OF THE SPONSOR OR FUNDER IN RESEARCH STUDIES3

Redberg spoke about concerns related to the objectivity and therefore the reliability of the published science that helps to guide professional practice, treatment guidelines, and how physicians care for their patients. The first item on her list of concerns is the text in a paper indicating evidence of the sponsor involvement study execution, such as choosing the clinical trial sites and investigators, or where the sponsor can adjudicate end points or help analyze the data. Often, she said, the end points in studies are not objective —such as death—but are soft and require adjudication. The subjectivity is further blurred, as the definitions of heart attack and stroke are expanding and no longer clear-cut diagnoses. “It makes a difference who is adjudicating the end point and how objective and blinded they are,” said Redberg. Another red flag for her is if the sponsor participated in writing a paper, reviewed it before publication, or had to sign off on the final product.

As an example, she cited the COAPT trial of a cardiac device (Stone et al., 2018). Multiple papers had shown that it did not benefit patients, but the company-sponsored trial reported positive results. Upon reading the paper to see what was different compared to all the others, she found that the protocol had been designed by the investigators in conjunction with the sponsor, who also participated in site selection, management, and data analysis. In addition, many of the authors had a significant financial relationship with the sponsor. Still, FDA approved the device, and it is in current practice, all based on this one trial where it seems that the sponsor had a great deal of influence.

Other concerns of Redberg pertain to the outcomes of a study. Industry sponsors prefer to use composite outcomes with soft end points, which makes trials faster and cheaper. Composite outcomes are driven by the weakest (and most commonly occurring) end point. For example, heart

___________________

3 This section is based on the presentation of Rita Redberg, University of California, San Francisco.

attacks and death are a less frequent but clinically significant outcomes in her field, cardiology, but less frequent than hospitalization or a more subjective symptom, such as unstable angina. She also looks for conclusions that are inconsistent with the results, such as when the conclusions paint negative results in a positive light. In those cases, she always looks for text about the sponsor’s role and relationship with the authors. “By emphasizing benefit over harm, there is a risk of misleading clinicians and encouraging use of a device that adds cost and risk without possible benefit,” said Redberg.

She recounted an incident involving a researcher at UCSF who conducted a study showing that generic levothyroxine was equivalent to the branded drug Synthroid. They submitted a paper describing the results to a respected journal, but it was pulled at the last minute because the agreement with the industry sponsor gave it final publication approval (it was eventually published). Redberg noted that the University of California has banned contracts that allow funder control of publication, but this is not a policy at all academic institutions.

High-quality sponsor-funded research, said Redberg, requires independent, highly qualified academic investigators. They do not need sponsors to help with putting together and running a trial, data analysis, or writing up the results. She wondered if journals should restrict the sponsor’s role in submissions just as papers published in leading medical journals have an absolute clinical trial registration requirement. She noted that JAMA had a 2005 policy that any paper with a sponsor involved in the data analysis also had to have an independent statistical analysis, and it is worth exploring if the policy was effective in improving objectivity.

One policy in effect is the requirement to include a data-sharing statement, though most such statements for industry-funded studies say that the investigators are not sharing their data. “I think having data publicly available so that independent researchers could analyze the same dataset would certainly help to improve the objectivity of the science,” said Redberg.

The end goal, she said, is that investigators should be independent of the sponsor in all aspects of study design, data analysis, and writing.

ALTERNATIVES TO INDUSTRY: SEEKING INDEPENDENCE IN BIOPHARMACEUTICAL RESEARCH4

Grundy noted that private industry, a specific type of institution, share a set of practices as to how they exert influence by sponsoring research. Both economic factors, such as shareholder returns, and politi-

___________________

4 This section is based on the presentation of Quinn Grundy, University of Toronto.

cal factors, such as the regulatory environment and structure, incentivize those practices. By studying these factors, it might be possible to imagine new conditions for the research ecosystem that address sponsor influence on quality and independence.

Biopharmaceutical companies and medical device manufacturers, as previous speakers noted, are involved in clinical trials in a variety of ways, from providing free study drugs to conducting trials and writing and publishing trial results.

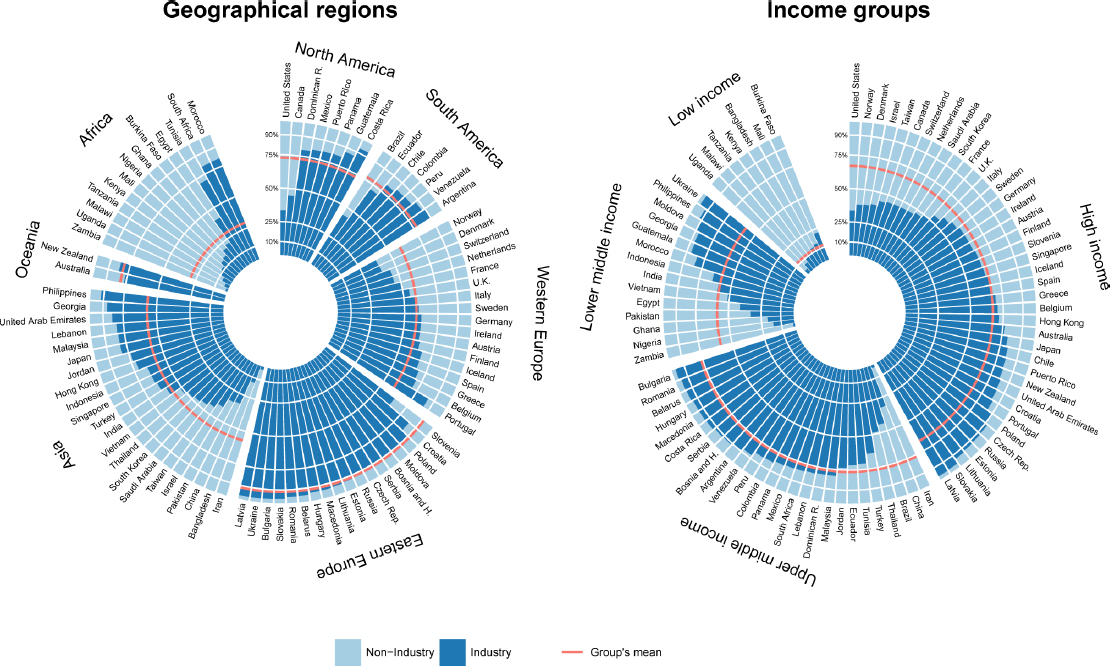

To illustrate the extent to which industry sponsors clinical trials, Grundy cited work that characterized trials initiated between 2006 and 2013 and registered in the WHO Clinical Trials Registry Platform and sorted them by country and World Bank income category (see Figure 5-1) (Atal et al., 2015). Thirty percent had an industry sponsor that was the primary funding source, which Grundy said may underestimate industry involvement. However, looking at the distribution globally and by income category shows that industry sponsors over two-thirds of trials in high- and upper-middle-income countries but only 12 percent in low-income countries. The majority of international trials (80 percent) were industry sponsored.

The talks during the workshop painted a compelling and evocative picture of the web of relationships through which industry can influence research in addition to sponsoring it, said Grundy. She argued that COI is a distinct, though clearly related, concept. It is thus important to understand sponsorship in a social context, which includes the relationships between trialists, researchers, and industry as a backdrop. Given that, Grundy agreed with speakers who articulated and advocated for transparency around these relationships and management strategies that go beyond disclosures, which are visible but not always fit for purpose. “If it is difficult to understand their relevance, we have the likelihood of [disclosure] backfiring,” said Grundy. In addition to structured reporting to enable meta-analyses, additional information is needed for disclosures to be relevant, be transparent, and enable accountability.

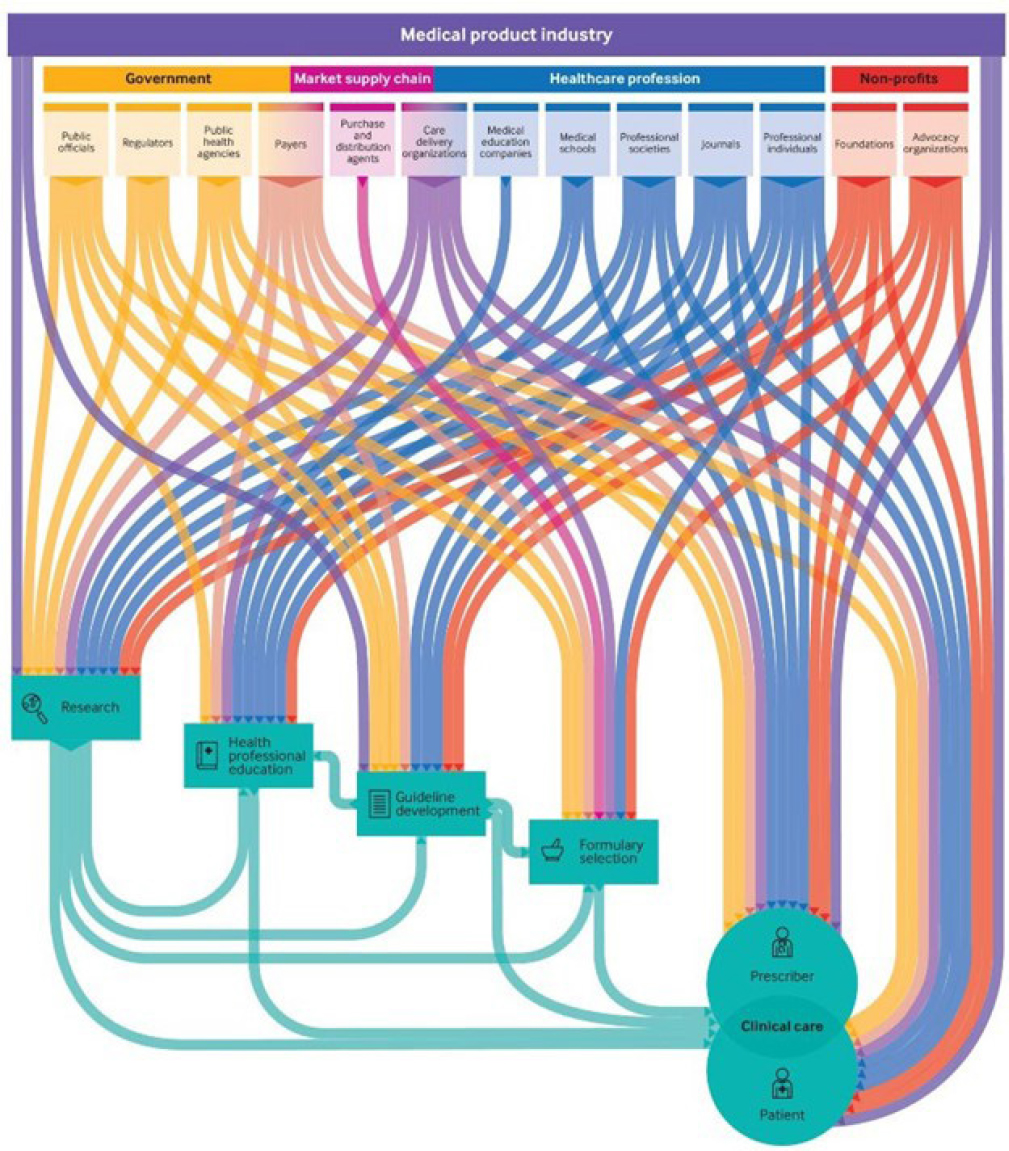

It is important, said Grundy, not to lose sight of the downstream effects of industry sponsorship, on not only research but health professional education, guideline development, formulary selection, clinical practice, and ultimately the patient. Grundy cited a recent scoping review that mapped the range of medical product industry ties within the health system (see Figure 5-2) and found that most of these activities are unregulated, are opaque, and have real downstream and often harmful effects on patients and other stakeholders in the health care system (Chimonas et al., 2021). “I think it is important to highlight the role of industry sponsorship in research as the root cause of many of these dependencies,” said Grundy.

SOURCE: Presented by Quinn Grundy on December 16, 2022 (Atal et al., 2015).

SOURCE: Presented by Quinn Grundy on December 16, 2022 (Chimonas et al., 2021).

“Clinicians frequently perceive industry or their representatives as the experts. They rely on industry-sponsored, -conducted, and -curated research and information for clinical practice,” Grundy said. Her perspective as a nurse is that this applies to not just drugs or surgical devices, but a range of medical products and devices used in day-to-day care. “Industry is often the only source of information about those products,”

said Grundy, which means that industry representatives, instead of other clinicians, are taking on the role of educators in terms of integrating information about clinical products into practice. To Grundy, this underscores the need to develop research practices and policies that conceptualize, prioritize, and ensure independence, such as the separation and blinding approach that Sah proposed. Grundy also commented that Sah’s notion of deep professionalism is a social practice that requires spaces for training, research, and dissemination.

Grundy was involved in the revision of the 2020 Cochrane Collaboration COI policy and believes this represents an example of a policy lever from a trusted organization to create a norm of separation between those sponsoring research and those appraising, synthesizing, and disseminating evidence in forms that are most useful to clinicians and the public. To her knowledge, the Cochrane Collaboration database of systematic reviews is the only source of biomedical publications that prohibits industry funding of the review and British Medical Journal is the only other example that will not accept papers reporting on tobacco industry-funded research.5

Switching gears, Grundy discussed a study she and her colleagues conducted that offers insights into how to reimagine research conduct such that the public sector takes a leading role. During the early days of the pandemic, convalescent plasma from people exposed to COVID-19 emerged as a promising stopgap measure while the world waited for vaccines and other treatment options to become available. Two main approaches existed to study whether it was effective. On the public side, blood services, hospitals, and academic researchers were collecting plasma for direct transfusion, but the for-profit plasma industry was interested in developing a hyperimmune immunoglobulin isolated from plasma.

The goal of her study was to understand the social processes of clinical trial governance for this type of natural experiment with diverse players involved. Grundy considers the result a possible approach for public sector drug development and innovation in biopharmaceutical research. Her team found that almost all the trials were nearly exclusively publicly funded by government and nongovernmental actors. Industry led the hyperimmune globulin work, though it partnered with the NIH, which funded and conducted the trial with drugs provided by industry.

Grundy explained that because no manufacturer was involved in the publicly funded trials, they had no complex negotiations around acquisition, pricing, and supply. As a result, many countries placed a high priority on studies with convalescent plasma due to equity considerations. Grundy said that this illustrates that agenda setting and the involvement

___________________

5 https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2018/11/12/lisa-bero-more-journals-should-have-conflict-of-interest-policies-as-strict-as-cochrane/ (accessed February 23, 2023).

of industry sponsors is inherently about the resource distribution, who benefits, and who is at risk.

The convalescent plasma trials in different national contexts illustrated different values guiding study design and eventual outcomes, said Grundy. Sometimes, the discussion was around prioritizing clear generation of evidence. The United Kingdom, for example, conducted large, integrated health system adaptive trials; the United States, which prioritized access and establishing safety, launched a large observational trial through an Emergency Access Program. Grundy explained that she sees both sets of values as legitimate and oriented toward the public’s interest, but each has implications for stewardship of resources and generating meaningful research results. “At the end, the takeaway is the need to think about clear, transparent, and accountable processes for making these values explicit and ensuring representation of the communities who are actually involved,” said Grundy, who added that accountability needs to be guided explicitly by public interest.

Another feature of these publicly funded trials that was qualitatively different was their reliance on public infrastructure, such as NIH and trial networks established for other diseases. Grundy noted that the authors of a large trial in India stated that “reputed elite institutions, first-world collaborations, third-party organizations, or big funding are a big help if available, but they are not indispensable.”

Grundy argued that framing the problem as needing to replace the large investment that industry has in clinical trials is insurmountable because of a lack of political will, “but I think it is also interesting to think about what research is actually needed, what is the priority, what resources are in place, and how can we leverage those most effectively.” In addition to generating research results, the convalescent plasma trials also generated infrastructure and capacity within the countries that ran them. “This is consistent with where we see generally with public sector investment in research, in basic research training, and capacity building,” said Grundy, who also noted the substantial openness in these high-profile studies, which again contrasts with the status quo. Networks and investigators shared trial protocols openly, and most had public-facing websites that enabled Grundy and colleagues to access study documents. Most of the studies said their data were available upon reasonable request, which was not quite the degree of openness required for an open science approach or reproducibility, but they also released their findings via preprint, press release, and Twitter to make them widely available.

Convalescent plasma became a high-profile treatment, a story involving entertainment stars, cruise ships, and black markets, said Grundy. Political decisions in India and the United States made plasma available outside of formal trials, resulting in a surge in demand and creating competition

for trial participants. Each analyzed study, however, published its results in high-impact, open-access journals despite plasma not being effective in many but not all studies. Treatment guidelines incorporated this evidence rapidly, and the change in practice happened despite political pressures.

In conclusion, the story of these studies provides a different model for biomedical research. “I think this helps us reframe the purpose of health research and ultimately sponsorship,” said Grundy. “We do not need to think about these as positive or negative trials; we needed to answer a question in a timely way, and important way, and we were able to develop a definitive answer.” To Grundy, this is an example of public sector innovation that is mission oriented and prioritizes equity, affordability, and access. “I would argue that stewardship of resources and equity should be notions we further build into an idea of research integrity,” she said. “We need to think of research, particularly health research, in the context of health systems and public health capacity and the role of public funding in relying on but also building and generating these public good.”

PROTECTING THE SCIENTIFIC INTEGRITY OF THE IARC MONOGRAPHS6

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) is the specialized cancer agency of the World Health Organization and the objective of IARC is to promote international collaboration in cancer research.7 The monographs program, explained Vincent Cogliano, are a 50-year-old series of scientific reviews identifying environmental factors that influence the risk of human cancer. The monographs are developed by the experts who conducted the original research, and they are used by national and international health agencies to support actions that prevent exposure to these compounds. In 2003, around when Cogliano joined IARC, The Lancet had published an editorial that said, “It only needs the perception, let alone the reality, of financial conflicts and commercial pressures to destroy the credibility of important organizations such as IARC and its parent, WHO” (Lancet, 2003).

As Cogliano recalled, he and his colleagues took this comment seriously. At the time, several approaches existed for addressing COIs, one of which was to ignore the issue, which fewer organizations are doing today. Some organizations required only disclosure, and some required disclosure but checked to make sure that not too many experts had conflicts. Some tried to balance experts with COIs with those without, and

___________________

6 This section is based on the presentation of Vincent Cogliano, California EPA Office of Environmental Hazard Assessment.

7 https://www.iarc.who.int/cards_page/about-iarc/ (accessed April 21, 2023).

others tried to balance experts with COIs with an expert with an opposing interest. IARC, he said, tried to avoid COIs completely.

Cogliano identified a tension between competing ideals. “Do you want IARC evaluations of carcinogenicity developed by the most qualified experts, or you want them developed by experts whose impartiality is beyond question?” he said. “The public needs to be confident that experts with a conflicting interest have put the public interest ahead of that conflicting interest.” If that is not easy to do, IARC tries to minimize the role of the conflicting interest.

Cogliano noted that this has become a more visible issue because interested parties have sponsored many of the epidemiologic and experimental studies or reanalyses of earlier studies. On the one hand, this creates a challenge because selecting experts with a real or apparent COI could erode confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the results. On the other hand, omitting prominent experts can create the perception of reduced scientific quality, a concern he heard when he spoke about IARC’s approach at scientific meetings.

IARC’s solution to achieving both ideals has been to create a new category of participant: the invited specialist. Cogliano explained they have critical knowledge and experience but are recused because of a COI from certain review committee activities, such as drafting any text that summarizes or interprets cancer data or developing conclusions. IARC has invited these specialists to meetings in limited numbers to contribute unique knowledge and experience and occasionally develop a chapter on production and use or compile other exposure information.

In short, said Cogliano, invited specialists are a resource that the committee can ask about details of a study that may not appear in a published paper. In this way, IARC meetings include the best-qualified experts, but the monographs and conclusions are developed by experts without COIs. The invited specialist role also protects the integrity of scientists affiliated with interested parties, since they are present as a resource, not to influence the outcome, and therefore have no responsibility for an evaluation that might not end how their company wants.

The process for selecting experts to participate on review committees starts with a literature search and public nominations to identify potential experts. All of them submit a declaration of interests; if they have no COIs, they may be invited to join. If a COI exists, IARC looks for a comparable expert; if necessary, the expert with a COI may be an invited specialist, explained Cogliano. All declarations are updated and reviewed again at the committee meeting.

IARC uses several criteria for what constitutes a COI: whether the expert was employed by an interested party over the previous 4 years; has consulted or given expert testimony on matters before a court or

government agency; and has a financial interest, such as owning stock, or relevant intellectual property, such as patent rights. IARC also looks at support for an expert’s own research and support for others in their research unit or organization. As an example of the latter, Cogliano said that the chair of a department who does not work on a particular project but whose department has a grant from a sponsor would have a COI.

In addition to the declaration of interest, IARC will often call a potential expert and ask questions that could reveal a pattern of activities that might suggest an ongoing relationship, such as participating in a few workshops with the same group of people that includes those with COIs. IARC also examines the acknowledgment sections of recent papers to identify possible supporters and searches the Internet for links to the expert. For example, one potential expert for a monograph on estrogen and progestogen contraceptives and hormone therapy who did not declare a COI was featured in a set of what were essentially marketing meetings advertising the use and safety of a particular contraceptive device. Finally, said Cogliano, IARC staff reviews what constitutes a COI at the committee meeting to ensure that committee members truly understand.

IARC has seen various attempts to game the process, said Cogliano. Occasionally, reanalyses appear in journals a week before a committee meeting in which the results are less positive than they were in the original papers. Interested parties also sponsored an ad hoc conference a few weeks before a monograph meeting to which four or five of the selected experts were invited to attend and spend several days with the special interest. “Somebody once showed me a letter about honoraria that they were being paid that said if you would rather this not show up so you do not have to declare it, we can adjust your travel reimbursement to cover this,” Cogliano recounted. Interested parties have also sent staff to Lyon, France, to monitor a meeting and tried to communicate with a specialist there.

IARC also has a process for independent reporting of COIs by a third party that he believes holds great promise for ensuring that organizations adopt a strong policy and do not backslide. At a monograph meeting, IARC asks experts to update their declarations and to complete The Lancet Oncology’s COI form; the editor independently reviews the COI statements and reports any COIs alongside a published summary of the meeting (Cogliano et al., 2005).

Before a meeting, IARC posts a list of committee members on its website along with the following message: “IARC requests that you do not contact or lobby meeting participants, send them written materials, or offer favors that could appear to be linked to their participation... IARC will ask participants to report all such contacts and will publicly reveal any attempt to influence the meeting” (Cogliano et al., 2005). IARC also reminds committee members in its invitation to participate letters and

during the meeting to safeguard the integrity of everyone’s work by resisting and reporting all attempts at interference. Finally, it includes a statement in a preamble to the monographs: “It is not acceptable for observers or third parties to contact other participants before a meeting or to lobby them at any time.” The hope is these actions serve as a deterrent to lobbying participants either before or during a meeting, said Cogliano.

One reaction in response to these procedures came from The Lancet Oncology in 2005, 2 years after it first voiced its concerns about any perception of a COI. After reviewing the steps IARC had taken, the journal’s editor wrote that they were “an important step toward restoring trust in the way that results of studies done by publicly funded agencies are both prepared and reported. The issues encountered by IARC are certainly not unique, and we hope that this joint initiative will serve as a model for other health agencies” (Collingridge, 2005). EPA has even adapted the IARC process for contractor-managed peer reviews.8

Cogliano said that good research studies are not sufficient. “We also need good review committees who are composed of knowledgeable experts who are free from conflicting interests and who can work free from interference,” he said. “Not only must we reach an appropriate conclusion, but we must also do so in a transparent manner that promotes public confidence.”

MINIMIZING BIAS IN AHRQ EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE CENTER PROGRAM SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS9

Umscheid explained that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is one of 11 agencies in the Department of HHS and that it its mission is to produce evidence to make health care safer, higher quality, more accessible, equitable, and affordable and to work with partners to ensure that the evidence is understood and used. AHRQ established the Evidence-Based Practice Center (EPC) Program in 1997. The program has provided systematic reviews of published scientific evidence on a range of health topics for a variety of requesters and invests heavily in methods development for evidence reviews. Reviews and methods work are contracted to nine academic research organizations (Table 5-1). The EPCs, said Umscheid, play a big part in ensuring rigor and minimizing bias in AHRQ’s reviews, as do the AHRQ EPC Division’s staff members, who have expertise and experience in the clinical topics reviewed by EPCs

___________________

8 Details of EPA’s process are available at https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-01/documents/epa-process-for-contractor_0.pdf (accessed February 2, 2023).

9 This section is based on the presentation of Craig Umschied, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

TABLE 5-1 Current AHRQ-Funded Evidence-Based Practice Centers

|

SOURCE: Umscheid Slide 5, Effective Health Care Program, 2021.

and in systematic review methods. He noted that the impact of the EPC program depends on the trust users have in its products and the partners who work with the EPCs, which include guideline developers both within and outside of the federal government, such as professional societies.

The EPC Program has worked with over 100 unique partners and completed over 800 evidence reviews in its 25-year history. These reviews have informed approximately 200 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, 200 clinical practice guidelines issued by federal and professional society partners, 35 Medicare National Coverage Determinations, and 40 NIH research prioritization meetings, said Umscheid.

An AHRQ EPC systematic review is a summary of overall evidence to address a set of key questions identified, explained Umscheid. It is protocol driven and starts with a comprehensive search of existing peer-reviewed studies. EPCs appraises each study critically and summarizes findings for each key question addressed across all important outcomes, including benefits and harms. EPC methods are based on the National Academy of Medicine’s Standards for Systematic Reviews,10 which AHRQ helped fund.

Umscheid categorized the systematic review process into five main steps: preparing the topic, searching for and selecting studies for inclusion, extracting data from the studies, analyzing and synthesizing the studies, and reporting the findings. EPC does significant work preparing and refining the topics, which supports transparency, improves rigor, and minimizes bias. Most reports EPC prepares are triggered through a request from a federal agency to inform a federal policy or decision or nomination

___________________

10 Available at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/13059/finding-what-works-in-health-care-standards-for-systematic-reviews (accessed February 2, 2023).

by the public. He noted that EPC receives so many of the latter that it has a selection process that is as transparent as possible to minimize bias.

The topics must be appropriate for review in that they are related to U.S. health care interventions that address significant disease burden or vulnerable populations and have high interest or cost, said Umscheid. An additional requirement is no recent systematic review on the topic but existing studies that EPC can synthesize. An end user partner must be identified who will help shape the review and disseminate and implement it to produce change.

EPC puts a great deal of effort into scoping the key questions, with a focus on increasing rigor and transparency and minimizing bias. This involves fleshing out the target population, specific interventions, and comparators and the outcomes to include. EPC relies on experts to inform the scope of the review; the experts must disclose financial and other relevant COIs. “Because of their unique content expertise, those with potential conflicts may still be retained to help us scope the protocol,” said Umscheid. “We aim to balance, manage, and mitigate potential conflicts of interest across the expert panel that is going to inform the protocol for review.”

As an example, Umscheid discussed a recent report developed in partnership with the American Epilepsy Society and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) that evaluated interventions for managing infantile epilepsies. This topic met all the selection criteria, and EPC worked with pediatric neurologists and neurosurgeons, epilepsy nurse practitioners, dietitians, Ph.D.s involved in epilepsy research, and the executive director of a family advocacy foundation to scope the review. The review focused on children aged 1 month to 3 years old; assessed pharmacologic, dietary, surgical, and other interventions; and looked at both intermediate and patient-centered health outcomes and adverse effects of the interventions.

After creating the review protocol, EPC conducts a comprehensive search of the peer-reviewed literature. For the infantile epilepsy review, this search identified 11,000 records, 41 of which were included. Two individuals then screen the studies independently against agreed-upon eligibility criteria, said Umscheid, and two others extract agreed-upon data from those studies.

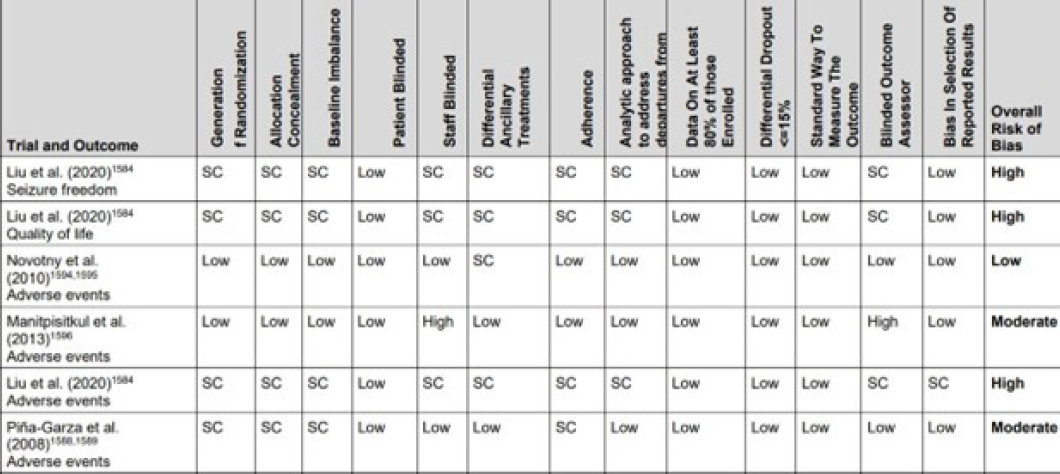

EPC uses standardized risk-of-bias assessment tools for each of the selected studies. Umscheid explained that EPC used the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool for randomized controlled trials and the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions tool. These tools assess the similarity between test and control groups at baseline, adherence of groups to assigned interventions, completeness of outcome assessments in each study group, and blinding of those prescribing and receiving interventions and those evaluating outcomes. These risk-of-bias assessments (see Figure 5-3) can help identify and mitigate bias resulting from COIs by

NOTE: SC = some concerns.

SOURCE: Presented by Craig Umscheid on December 16, 2022 (Effective Health Care Program, 2022).

determining whether studies are selecting specific designs and hypotheses to favor the treatment over the control, such as by picking inferior comparison drugs and doses or selectively reporting outcomes, including certain outcomes from multiple available end points or using composite end points without presenting data on individual end points.

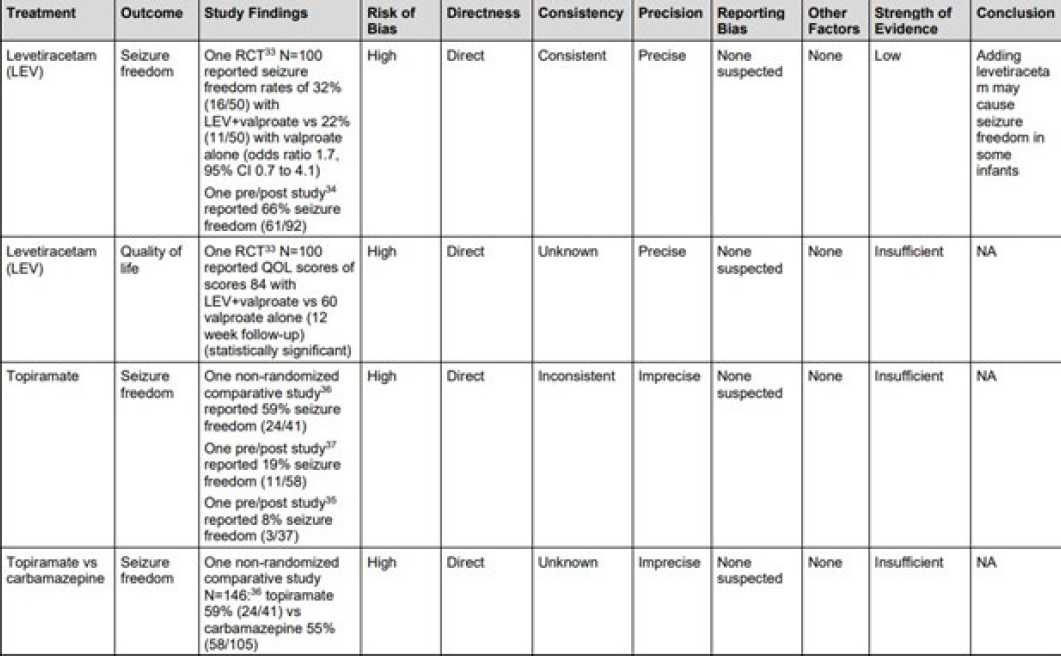

The risk assessments allow the reviewers to explore different results between higher and lower risk-of-bias studies. If the outcomes are essentially the same, that provides more certainty regarding the findings, said Umscheid. Risk of bias can also enable grading of the overall strength of the evidence for the interventions. Doing so for interventions across all studies by outcomes considers factors such as study design informing the outcome, the consistency of studies examining the outcome, the precision of the results, and the magnitude of the effect. Figure 5-4 shows the strength-of-evidence table for the outcome of “freedom from seizure.”

Umscheid said that once the draft report is complete, EPC releases it and posts it on its public website11 to provide the opportunity for public comment; it also undergoes peer review. When the final report is released, EPC reports a disposition of the comments received during the public comment process. “Stakeholder engagement and transparency throughout this process helps us increase the rigor and minimize potential bias of our reports,” said Umscheid. Many reports are also accompanied by interactive visual dashboards on the EPC website.

PANEL DISCUSSION: PROTECTING THE INDEPENDENCE OF RESEARCH

Comments on the Presentations

Woodruff listed themes from the presentations about structural solutions to the problem of sponsors influencing research, starting with the need for public funding. To ensure research is not being influenced by a financial interest, both the research enterprise and the people conducting the research need to be publically funded, Woodruff said. She noted that the pace of public funding, such as grants from NIH, have not kept up with the cost of research, creating pressure on academics to seek other sources of funding.

Woodruff said that as NIH underwrites work that looks at the rigor of research, it should also fund areas to understand how its funding influences financial COIs. She noted the importance of access to the truth, which requires public access to industry documents. Many of the presentations illustrating how corporate interests influenced the scientific process were only possible because of access to internal industry documents archived

___________________

11 https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ (accessed February 2, 2023).

SOURCE: Presented by Craig Umscheid on December 16, 2022 (Effective Health Care Program, 2022).

at public institutions, such as UCSF. Woodruff called for supporting these archives and working to make litigation-disclosed documents public. The latter, she said, can help create accountability for how interests have influenced and evaluated science. She also suggested expanding the public registries for competing financial interests to other areas beyond pharmaceuticals and U.S. clinicians.

Woodruff noted that just because meta-research finds that a COI leads to a bias in the results does not mean excluding the findings from further analysis, but it does mean accounting for potential bias in evaluating the evidence. She also called the discussions about declarations of COI eye opening, particularly the research showing that declarations are insufficient. She appreciated the recommendations to investigate this issue and norming values about why it is important.

Her final comment was about representation and who is at the table when having these conversations. In the environmental health field, for example, the communities experiencing harm should be represented in these meetings, as should the environmental justice community.

Lexchin discussed areas that he believes should be the focus of reform. The first involves leadership; he noted a failure of medical leadership around the issues the workshop has discussed. For example, an investigation of financial COIs for 328 leaders of 10 leading U.S. professional disease-focused organizations found that two-thirds had financial COIs and received $135 million from industry sources, with a median of about $32,000 per person (Moynihan et al., 2020). “When you have conflicts at the top, those organizations may not be willing to confront problems associated with those conflicts and bias in the outcome of research,” said Lexchin. Similarly, a study Lexchin participated in found that societies involved in sponsoring clinical practice guidelines in Canada were not disclosing their industry funding in the guidelines, though they did so on their websites (Elder et al., 2020).

Medical journals also need reform when it comes to identifying COIs, said Lexchin. He noted that the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services maintains the Open Payments database, which allows anyone to search payments made by drug and medical device companies to physicians, physician assistants, advanced practice nurses, and teaching hospitals.12 He wondered if medical journals use the database to identify COIs among the authors of the studies they are considering publishing. “There is good literature that shows there is under-reporting of COIs by authors, so we need to encourage medical journals to look and use that database to look for where those undisclosed conflicts are,” he said.

___________________

12 https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/ (accessed February 2, 2023).

In addition, said Lexchin, most major medical journals do not disclose the details of their funding sources, such as how much money they get from advertising, the sales of reprints, and other sources that may include industry, and he called for them to disassociate themselves from industry funding. He calculated the advertising revenues that the Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine received and determined that it could eliminate all pharmaceutical company advertising if it charged $50 more per person for membership in the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (Lexchin, 2009). The journal dismissed this idea, saying it had no trouble with drug company promotion.

One approach for dealing with this, which Sah mentioned, is to go beyond disclosing COIs and eliminate them by introducing policies at the level of medical schools and hospitals to ensure a separation between students and trainees and industry. Lexchin said that a few studies have looked at the long-term consequences of restricting contact and found that clinicians trained at institutions with such a policy were less likely to interact with industry, prescribe new and relatively untested drugs, and believe the information they received from industry (McCormick et al., 2001, 2002). Given this, he encourages medical schools and hospitals to introduce strict policies that separate their trainees and students from industry. However, he noted that when McMaster University’s general internal medicine residency program did so in the early 1990s, with agreement from the residents, the brand-name industry association threatened to withdraw research funding.

Lexchin raised the issue of industry support for clinical trials of drugs and how that might affect pharmaceutical product approvals. He acknowledged that public funding of drug trials would address this problem, but that would require a major increase in public funding. A parallel approach would be to change how companies think about their research; he proposed introducing a medical need clause into regulatory requirements, which Norway did at one time (Hobæk, 2019). That clause would reject products that were no more efficacious, safe, or convenient than currently available products. In his view, if the major regulatory authorities started to do that, industry might change how it does research.

He also called for strengthening the standards of regulatory agencies, increasing public funding for them, and eliminating industry user fees. That might make a difference in how regulatory agencies approach the research they review (Gaffney et al., 2018). “If they are being more strict with the research, then companies will modify the way they do their research,” said Lexchin. In addition, clinicians should stop relying on publications and turn to the clinical study reports, which provide much more information (Wieseler et al., 2012, 2013).

DISCUSSION

Responding to Lexchin’s comments on industry user fees, Redberg explained that FDA negotiates its fee agreements with industry behind closed doors. “There is no public there, and there is no negotiation of the rest of the FDA agenda with the public with the recognition that it is a taxpayer-supported agency,” said Redberg. “I think that is just a huge problem, and it makes it seem as if the FDA works with industry, not as a protector of public health.”

Sah said she agreed wholeheartedly with the suggestions that Woodruff and Lexchin made, and that public funding is a key aspect. She commented on industry threats to withdraw funding if new policies restrict access to research or clinicians and said this will be difficult to tackle without a big shift in how research is conducted, which needs a coordinated approach. Woodruff agreed that more public funding is needed and added that an industry fee should be paid to an independent agency, such as FDA, though not through the current process, as described by Redberg. Rather, the fees could go through a public process. Lexchin noted that Italy funds drug research via a 5 percent tax on the amount that companies spend on promotion (Italian Medicines Agency, 2010). Given estimates that pharmaceutical companies spent nearly $30 billion in 2016 on promotion (Schwartz and Woloshin, 2019), 5 percent would be $1.5 billion.

Grundy supported that idea and noted models for shoring up public institutions, along with a need for more public representation in the operations of public institutions that work in the public interest. Today, it occurs largely through patient representatives who are often sponsored by industry or other commercial interests. “I think we need to rethink about the ways that not just patients, but publics are involved in setting research agendas and asking the questions that are important in the priorities and in the research itself,” said Grundy.

Sah commented on the decrease in public trust in science and experts in science, which was apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the connection to COIs and representation, particularly increasing representation in clinical trials. “I think both the public trust and the representation aspect are key things to consider moving forward,” said Sah.

Bero raised the idea of less is more in terms of research and if that would help with evidence synthesis. “If we have research focused on the important public health–relevant questions, is it really better for us than just having a lot of funding for research that we do not really need?” Bero asked.

Redberg thought that was a fabulous idea. She also commented that she hears from industry that if it does not drive the research agenda, it will stymie innovation and developing new drugs. “‘Innovation’ is used

incredibly loosely, and anything new is called ‘innovation,’” she said. What industry is really talking about is pushing things to market that are not well studied but supported by experts who received millions in funding to say it is good. In her view, it is not a given that we need more drugs to treat the same condition.

Umscheid pointed out that much of the work EPC does involves building relationships with funding organizations to communicate identified evidence gaps back to those institute leaders to help them prioritize their research agenda. He added that all of EPC’s systematic reviews include appendixes with information on studies’ funding sources. However, EPC does not automatically rate industry-sponsored studies as having a high risk of bias because unrelated causes of such risk may exist. Instead, EPC uses the validated tools he described to look at differences between groups and how interventions, comparators, and outcomes are defined.

Bero mentioned Dunn’s work on automated tools to identify risk of bias and how funding source and COI would be characteristics fed into those tools to assess risk for an individual study. She added that it is important to distinguish between the risk in individual studies and the types of bias seen across a body of studies, such as publication or funding bias.

Gunsalus asked Sah to address an audience question about whether the pooled funding model leads to COIs at the institutional level and makes universities, rather than the individual investigators, beholden to their corporate sponsors. Sah identified institutional COIs where they are chasing gifts and other types of fundings from corporate sponsors. It is important to question how that money will be used, about any blinding and separation, and if pooled funding will affect how whoever accepts the money conducts their day-to-day activities. Other questions include whether the sponsor influences any aspects of how the university is run, its relationship with the sponsor, and how much feedback the sponsor gives it. “Those are the questions that we need to ask with regards to sort of institutional level COIs, because there is the risk there will be an attempt to please certain sponsors so you can get more income in the future,” said Sah.

Grundy mentioned the need to think about the social context around the commercialization of academic research. She noted the qualitative social science studies reporting that investigators get the sense they are being actively encouraged to partner with industry by one policy but then feel slapped on the wrist for having a COI. “This is something well within academic and university policies that could be addressed,” she said. Asked for final comments, many of the panelists noted the complexity of this issue and the need for grassroots efforts to address some of the challenges discussed.

This page intentionally left blank.