Sharing Health Data: The Why, the Will, and the Way Forward (2022)

Chapter: 13 Conclusion

13

CONCLUSION

The 11 exemplars described in this publication illuminate the possibilities for improving care, patient experience, and research when sharing health data among different stakeholders. Data exchange, when thoughtfully executed, can also support efforts to improve patient safety and even control health care costs through more efficient and effective use of information. Nine of the 11 cases highlighted in this publication were active and operational prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, and the ensuing pandemic only served to underscore the vital importance of maximizing all of the sources of health data at our collective disposal in support of better outcomes and continuous learning. The progenitor Special Publication underpinning this case study project, Health Data Sharing to Support Better Outcomes: Building a Foundation of Stakeholder Trust, elucidated many different cultural, financial, regulatory, and operational barriers to data sharing, but these examples offer many ways to attenuate the barriers and do so in a sustainable manner.

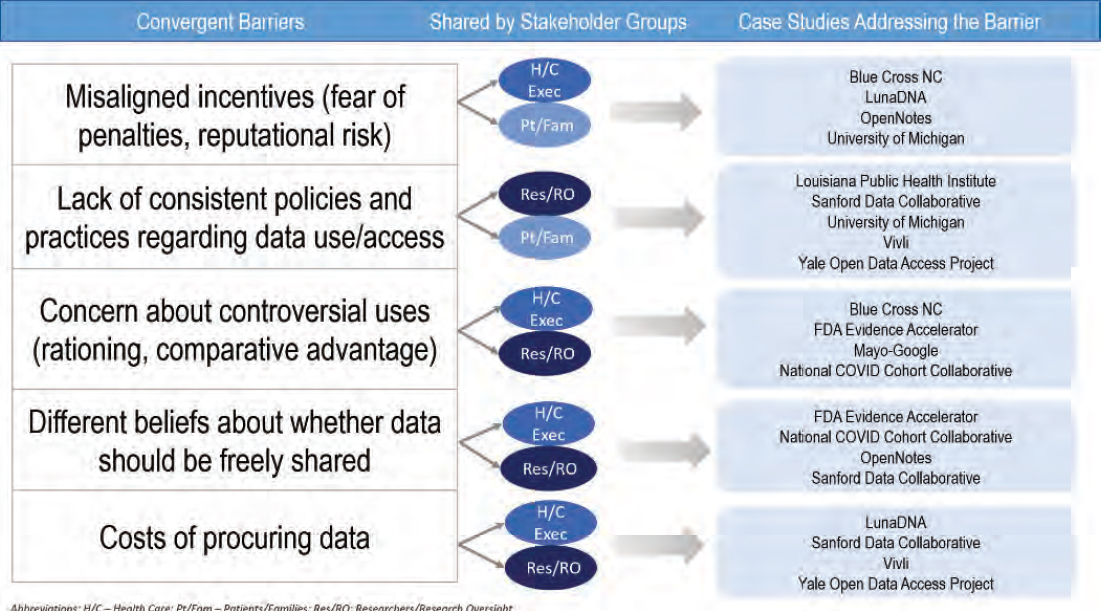

As shown in Figure 7, the case studies address multiple convergent barriers identified in Health Data Sharing to Support Better Outcomes: Building a Foundation of Stakeholder Trust. Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina (Blue Cross NC) and Luna respond to financial barriers often expressed by health system executives—namely, the absence of a compelling business model for sharing data, as well as concerns about reputational risk and a related concern that retaining singular control of data is a way of maintaining competitive advantage in one’s market. Yet, these two cases, along with the Sanford Data Collaborative (SDC) and Mayo-Google partnership, indicate that a visible approach to data sharing can serve to bolster reputation and differentiate systems. However, health care markets vary widely at the local level, and additional insights

are needed from other health systems and entities where the market competition is more diffuse. Each case also offers viable and transferable lessons about maintaining stringent data privacy and security.

Concerns expressed by researchers and research oversight leaders in Health Data Sharing to Support Better Outcomes: Building a Foundation of Stakeholder Trust spanned different categories (e.g., regulatory, operational, cultural), but all barriers centered on a fundamental issue of heterogeneity. Different beliefs, different approaches, different processes, different costs, and different regulations (or their interpretation) impede researchers from maximizing opportunities to use data as a means of improving the evidence base and conducting impactful research. Nearly all of the cases profiled in this Special Publication take on at least one of these elements of “difference” and provide blueprints for more consistent, standardized approaches that are well-vetted by contributors. The University of Michigan (U-M) case shows the added value of standardized approaches to accelerate research, even in a single institution. Other case studies with roots in academia, Vivli and the Yale University Open Data Access (YODA) Project, crafted consistent approaches to data sharing to ease operational and fi-

nancial barriers. Each has a transparent review and request process, and in Vivli’s case there is no upfront cost for the researcher to request and use data. In contrast, Luna employs a subscription model, charging institutions and granting user licenses to those who seek to analyze the de-identified, aggregated data.

A chief barrier expressed by patients and families was recognition—both of the value of data that they provide, and recognition that sharing clinical data with patients would accrue widespread bidirectional benefits. These aspects are at the core of participatory medicine, shared decision making, and patient empowerment. For patients who have tried to access their own health data, the OpenNotes case study provides a welcome solution—one that will only become more ubiquitous with the 2016 passage and 2021 implementation of new legislation prohibiting information blocking (Federal Register, 2020). With respect to financial disincentives, another barrier raised by the patients and families group, Luna is one of multiple such entities that seeks to apply a new business model of compensating patients for their data.

In consideration of this barrier raised by the patient stakeholders, all interviewees were asked whether and how patients were engaged in the development or implementation of the case activities; rarely did the respondents describe active and sustained patient involvement. The U-M team sought patient input, both via research studies and participation in community engagement “studios,” and the YODA project team engages patients as advisory board members. The SDC seeks to draw connections between research and health care outcomes as an element of its value proposition to patients receiving care at Sanford Health System. Each of these is a beneficial tether between patients and the use of their data, however, more concentrated and sustained engagement of diverse patients, families, and communities as data-sharing efforts mature is an important area needing attention.

The two use cases that emerged as a consequence of COVID-19, the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) and the COVID-19 Evidence Accelerator (EA), show how epochal events can spur rapid cultural, operational, and philosophical change. The common cause of unlocking the biology of the novel coronavirus and treatment of COVID-19 hastened collaboration and willingness to

share data and insights on a scale not previously seen. Similarly, Louisiana Public Health Initiative (LPHI) was spurred to rethink data availability, access, and sharing as a consequence of Hurricane Katrina. Those who might ordinarily “compete” on data or guard it for individual or a single organization’s needs embraced the value of sharing it for good. Taken together, these case studies illustrate the silver lining of opportunities born from crises. One key opportunity is to leverage messaging about the positive impact of data sharing and increase public awareness of its value. A second opportunity is to retain the efficiencies that manifested from the urgency of data exchange, including streamlined approaches to research review, protocol development, and contracting and other administrative elements.

THEMES ACROSS CASE STUDIES

Conversations with case study representatives yielded several themes. Some of these were intangible and philosophical in nature, and others were more tangible and operational. One common thread among the cases was the sense of a strong moral imperative—a deeply felt sensibility that democratizing and sharing health data required their action. Leaders of these entities took it upon themselves to develop new and different approaches based on an intrinsic belief that democratizing data is an essential element of improving health and health care.

A second pervasive theme, which was more concrete in nature, was the central importance of investing time at the outset to address legal, regulatory, and technical barriers. Multiple interviewees held that early conversations with their organization’s legal teams were a critical facilitator of their success. Particularly for those venturing into new terrain, the opportunity to openly discuss issues with legal and regulatory officials helped identify and anticipate issues and engage in shared problem solving. This built trust for the data-sharing work as a whole and helped solidify enterprise-wide engagement.

Similarly, bringing together different personnel with health information technology or health information management responsibilities in the organization helped address questions related to

workflow, access controls, and related data security issues. These foundational conversations were common in all of the permutations explored in this compendium—that is, whether it was sharing data across different health insurers, preparing for use of OpenNotes, developing a health information exchange, or developing a repository between academia and industry—the importance of garnering upfront cooperation and input cannot be overstated.

An additional commonality in many cases was gaining organizational buy-in from influencers. Having an influential champion or sponsor for ideas that come from within an organization is a well-established tenet in business and organizational management literature. While they may not be at the highest level of the organization, these are individuals who can help overcome resistance to new ideas and changes. The experiences of OpenNotes, University of Michigan, and SDC, as well as that of Blue Cross NC and the N3C, all illustrate the importance of a champion, whether it is a specialty care leader, a chief medical informatics officer, or even a funder.

PERSISTING CHALLENGES, “MAGIC WAND" INSIGHTS, AND ADVICE FOR OTHERS

Interviewees were asked about barriers they overcame as well as those that endure, framed as “if you had a magic wand and could change one aspect that would facilitate data sharing, what would you do?” This yielded a range of beneficial insights regarding the work ahead. The entreaty to revisit regulations that undergird health data was raised multiple times, as was the observation that the business model and incentives for sharing data need reexamination. Both of these notions are consistent with insights outlined in Health Data Sharing to Support Better Outcomes: Building a Foundation of Stakeholder Trust and provide additional substantiation for thoughtful reexamination and modernization of the entire policy landscape for health data—including policies that impact research, clinical care, payment models, interoperability, and information exchange. For example, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was passed in 1996, long before health data were digitized, and before contemporary data sharing became a routine practice and important need for research and care. The

more recent passage of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) and California Consumer Protection Act (CCPA) empower individuals to control how their health data will be used, albeit these regulations have introduced new complexities, particularly with regard to use and sharing of data between nations. With respect to the business model and incentives for health data sharing, many of these efforts rely on at least some external grant funding (including OpenNotes, YODA, U-M, LPHI, and N3C), which can often be sustained up to a point, but is less optimal than stable, predictable funding from an organization’s core budget.

While advice to others did not necessarily yield a generalizable concrete blueprint, many interviewees urged perseverance coupled with a “just do it” mindset, averring that the work is eminently worth pursuing, despite the multifaceted challenges. Others emphasized the importance of aligning the work of data sharing with the goals of all stakeholders—whether in a single organization, or across different organizations. For example, the Mayo-Google partnership is congruent with Mayo Clinic’s strategic initiative to improve health care through data-derived knowledge. Similarly, in engaging regional health system partners, Blue Cross NC sought to identify specific issues of importance to each partner to augment the value proposition for collaboration.

AREAS FOR FUTURE EXPLORATION

As noted above, a barrier expressed by researchers and research oversight leaders is the lack of shared principles about data ownership and sharing, and heterogeneity of beliefs about whether data should be shared. This perspective permeates how researchers interact with one another, but also influences attitudes about sharing data and knowledge with patients who volunteer to give their data and their time for research. Return of study results to participants is an important but inconsistent aspect of the research enterprise, and personal relevance of research is often a motivation for patients to volunteer for studies in the first place. As such, an objective of this work was to identify an organization that shares results with study volunteers as often as possible, and at an individualized versus summarized level. However, this proved elusive. Some or-

ganizations share study findings on an ad hoc basis, but this area warrants additional scrutiny since it can bolster patients’ sense of trust in research and demonstrates respect for the contributions of research volunteers. Dedicated funding for this step in the research process, and an expectation by major funders that researchers will share data with participants can remediate this gap. It is encouraging that the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us Research Program has specifically adopted the policy and practice of sharing data with all of their study participants, and the Program’s experience can illuminate a pathway for others (NIH, 2021).

The case studies in this publication are U.S. based, but the global implications of data sharing and exemplars from other countries represent key next steps in this work. Different attitudes toward the public utility of data and national data repositories used by other countries indicate that future work could compare and contrast examples of building trust and addressing barriers with a global lens. A recent report authored by several European academies of science identified another data-sharing challenge that was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic—the lack of unified regulations in the European Union and other countries (ALLEA, 2021). The report’s authors observe that GDPR has impeded data sharing and international collaboration with countries that have less stringent privacy provisions than those in the GDPR. The report recommends recommitting to broader international discussion and coordination about regulations that can be better aligned and facilitate reciprocity in data sharing.

Finally, the experiences of Vivli, YODA, N3C, and the Evidence Accelerator, as well as other entities not profiled in this report (e.g., Project Data Sphere, Sentinel Initiative, TriNetX) demonstrate that there are multiple different workable models and approaches to sharing data, based on the nature of the collaboration and relationships between stakeholders. The opportunity to undertake a more robust comparison of the comparative advantages and disadvantages of federated, centralized, and intermediated approaches is another potential next step.

CONNECTIONS BETWEEN CASE STUDIES AND THE PROGENITOR SPECIAL PUBLICATION

This Special Publication is relatively circumscribed in its breadth and scope, in that the case studies were identified through discussions among workgroup stakeholders who collaborated to produce the previous publication, Health Data Sharing to Support Better Outcomes: Building a Foundation of Stakeholder Trust, and the project was only intended to yield 10-12 cases. There are many other entities engaged in innovative approaches to heath data sharing, including MIMIC (a freely accessible critical care database), the Light Collective (a patient advocacy and education group created to support responsible use of health data), newer ventures such as Truveta (a company formed in 2020 as a collaboration among health systems who agree to share their data to improve patient care), and initiatives specific to a certain type of data, like the Medical Imaging Data Resource Center (Light Collective, 2021; MIMIC, 2021; Truveta, 2021; MIDRC, 2021)1. As such, the selected case studies are meant to show what is possible and offer a springboard for others interested in advancing both the philosophical importance of health data sharing, and pragmatic approaches to doing so.

Health Data Sharing to Support Better Outcomes: Building a Foundation of Stakeholder Trust enumerated several priority actions that could be achieved in one-to-three years, including this case study compilation. The compilation itself can provide insights for another of the action steps, the creation of a public education campaign or similar national conversation expressing the value and benefits of health data sharing, that helps individuals make better informed decisions about how they share health information, and helps organizations identify and uphold the highest ethical and technical standards for data use. The progenitor publication also included action steps related to payment and financing—both a reconsideration of how current payment models could thoughtfully integrate data sharing as a lever for supporting better care at

__________________

1 The Light Collective. 2021. Home. Available at: https://lightcollective.org/ (accessed May 9, 2021). Medical Imaging Data Resource Center (MIDRC). 2021. Home. Available at: https://www.midrc.org/ (accessed October 3, 2021). Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC). 2021. Home. Available at: https://mimic.mit.edu/iv/ (accessed April 29, 2021). Truveta. 2021. Home. Available at: https://truveta.com (accessed May 9, 2021).

lower cost and a deeper examination of viable business models that account for complexity of health data, estimations of its value, and the advantages of moving toward greater data sharing. In particular, the business model must account for the costs of not sharing, and the potential loss of competitive advantage if data are shared. Cases profiled in this publication provide a useful starting point for addressing many of these key aspects of the business case. Finally, the need for supportive government policies was called out in the previous publication and is echoed in many of the case studies. Newer regulations related to the 21st Century Cures Act and information blocking legislation are helpful, yet given the proliferation of health data sources, perhaps the most important new regulations will be modernization of the HIPAA Privacy Rule and expansion of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act to include all medical information (Federal Register, 2020). The process of updating HIPAA Privacy Rule is underway; however, the timetable for the regulatory revisions is unclear, as is the resulting translation of any new regulations into on-the-ground process change. HIPAA became part of both the lexicon and culture of privacy in health care and modernizing it in support of a broader embrace of data sharing will take time and effort on the part of all stakeholders, including government, health system leaders, compliance personnel, clinicians, and of course, patients and families.

THE PATH FORWARD

Given significant public and private investments in health research, health care solutions, and data aggregation and management utilities across the health ecosystem, and the unparalleled computational techniques that enable rapid analysis of exabytes of data, a trust fabric that supports the use and sharing of data is imperative. The concept of who owns health data remains contentious, especially given the liquidity and shifting value of data points when they are used alone or in combination with multiple sources such as financial or geolocation data. The traditional notion of what constitutes health data is particularly germane in consideration of health equity, as numerous social factors also help characterize the experience of health. Thus, ownership is an elu-

sive concept, but many stakeholders have a vested interest in the responsible stewardship and reinforcement of trust through their words and actions. Trade associations exist to support health information management. Many individual advocates and patient advocacy organizations offer positions on health data sharing, and some health and health care associations have issued statements about data use and data privacy. However, there is not a singular, visible advocacy organization that has health data sharing as its sole purpose—which may impede progress on regulatory and educational fronts. Health Data Sharing to Support Better Outcomes: Building a Foundation of Stakeholder Trust suggested that a consortium of organizations could advance dialogue and catalyze action. Though the case study interviewees were not asked about this explicitly, the collaborative tenor and enthusiasm of the participating organizations suggests that a unified consortium could accelerate progress and leverage the lessons of the exemplars featured here.

During the development of the previous publication, workgroup members were asked to consider not only the benefits of data sharing, but the consequences of not sharing data. The lost opportunities to maximize what can be learned at the individual and population level should serve to motivate action. Moreover, more robust health data sharing could help redress fundamental issues of data equity and algorithmic fairness by ensuring that larger and more diverse populations are represented in large data repositories and ensure that solutions harvested from health data truly confer societal benefit. As data become more proliferative and diverse, it is worth recalling that “Big Data” has often been characterized by a set of “V’s” with volume, variety, and velocity being commonly mentioned, along with veracity and value. Perhaps a more beneficial concept of Big Data with regard to sharing would include four A’s: health data that are accessible, affordable, analyzable, and actionable by all stakeholders—such a framework could galvanize public trust, forge better outcomes, and yield meaningful progress toward an equitable learning health system.